- Privacy Policy

Home » Ethical Considerations – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Ethical Considerations – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Ethical considerations are essential in research and professional practice, ensuring that work is conducted with integrity, respect, and responsibility. Addressing ethical concerns involves identifying and mitigating potential risks to participants, society, and the integrity of research. This guide explores the types of ethical considerations, real-world examples, and provides a structured writing guide for addressing ethics in academic or professional settings.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations are principles that guide the conduct of research or practice to ensure fairness, transparency, and respect for all parties involved. In research, they protect participants’ rights, maintain data integrity, and prevent harm. Ethical considerations often include informed consent, confidentiality, conflict of interest, and the minimization of risks.

Key Purposes of Ethical Considerations :

- Protect Participant Rights : Safeguard privacy, consent, and well-being.

- Maintain Research Integrity : Ensure accuracy, transparency, and honesty.

- Promote Social Responsibility : Avoid harm to individuals and communities.

Types of Ethical Considerations

1. informed consent.

Informed consent ensures that participants are fully aware of the research purpose, methods, potential risks, and benefits. Participants must voluntarily agree to participate without coercion or undue influence.

- Example : In a medical study, participants are given a document explaining the study’s purpose, procedures, and risks, and must sign it to confirm they understand and agree to participate.

2. Confidentiality and Privacy

Confidentiality involves protecting participants’ data and privacy, ensuring that their personal information is not disclosed without permission. Researchers are responsible for safeguarding data and maintaining anonymity.

- Example : A survey on mental health should not reveal any identifying information about participants, and data should be stored securely to protect privacy.

3. Minimization of Harm

Minimizing harm requires researchers to reduce any risks to participants. Harm can be physical, psychological, social, or emotional, and researchers must design studies that avoid unnecessary distress.

- Example : In an experiment involving stressful tasks, researchers should monitor participants’ stress levels and allow them to withdraw if discomfort arises.

4. Conflict of Interest

Conflict of interest occurs when researchers or practitioners have personal or financial interests that could affect their objectivity. Disclosing any potential conflicts is critical to maintaining transparency and credibility.

- Example : A pharmaceutical researcher with stock in a drug company must disclose this relationship to avoid bias when reporting drug effectiveness.

5. Honesty and Integrity

Honesty and integrity in research involve accurately reporting findings, avoiding fabrication or falsification of data, and acknowledging any limitations of the study. Plagiarism is also a violation of research integrity.

- Example : A researcher should report all data, even if results do not support their hypothesis, to ensure truthful representation of findings.

6. Respect for Vulnerable Populations

Researchers must take special care when working with vulnerable populations, such as children, elderly individuals, or people with disabilities, ensuring extra protections and sensitive handling of data.

- Example : When conducting interviews with children, researchers must have parental consent and ensure questions are age-appropriate.

Ethical Consideration Examples by Field

- Healthcare : Researchers conducting clinical trials must obtain informed consent, minimize patient risk, and disclose conflicts of interest.

- Social Science : In a study on family dynamics, participants’ personal information should remain confidential, and sensitive topics should be approached carefully to avoid distress.

- Business Research : A study on employee satisfaction should ensure anonymity for participants to prevent any workplace repercussions.

- Environmental Research : Research on natural resources should consider the rights of indigenous communities, ensuring fair treatment and respect for their land.

Writing Guide for Ethical Considerations

When writing about ethical considerations in a research paper or proposal, it’s important to address each ethical aspect clearly and transparently. Follow these steps to effectively communicate ethical considerations:

Step 1: Describe Participant Consent Procedures

- Explain Informed Consent : Detail how you will obtain and document informed consent from participants.

- Provide Documentation Details : Mention any forms or consent documents that participants will complete.

Example : “Participants will be provided with a detailed consent form outlining the purpose, procedures, and potential risks associated with the study. They will have the opportunity to ask questions before providing written consent.”

Step 2: Outline Data Confidentiality Measures

- Describe Data Protection : Explain how you will store and protect participants’ data.

- Anonymity Procedures : Detail how personal identifiers will be removed or masked.

Example : “Data will be stored on encrypted servers accessible only to the research team. Identifying information will be replaced with codes to ensure anonymity in data analysis and reporting.”

Step 3: Address Potential Risks and Harm Reduction

- Identify Risks : Describe any risks participants might face and the steps you will take to mitigate them.

- Provide Support Options : Mention any resources, such as counseling or withdrawal options, available to participants.

Example : “Participants may experience mild discomfort during the interview. They will be informed that they can pause or stop the interview at any time without penalty.”

Step 4: Disclose Conflicts of Interest

- Explain Any Conflicts : If applicable, disclose any potential conflicts of interest that could affect the study’s outcomes.

- Provide Justification : Explain why you can still maintain objectivity despite the conflict.

Example : “The researcher has no financial interest in the outcome of this study, ensuring that all results are reported objectively and without bias.”

Step 5: Outline Measures for Working with Vulnerable Populations

- Highlight Special Protections : Detail any additional ethical safeguards for vulnerable groups.

- Explain Sensitivity Measures : Mention how you will tailor interactions to respect the needs of these populations.

Example : “Given that some participants are minors, parental consent will be obtained for each child, and questions will be designed to be age-appropriate.”

Step 6: Ensure Honesty and Transparency

- Discuss Reporting Standards : Explain your commitment to accurately report data, methods, and findings.

- Address Limitations : Mention any limitations in methodology or sample that could affect the study’s results.

Example : “The study will report all findings, including unexpected results, to ensure complete transparency and integrity.”

Tips for Addressing Ethical Considerations

- Use Clear Language : Avoid jargon and explain ethical procedures in simple terms to ensure understanding.

- Be Specific : Detail the exact steps you will take to address ethical issues, providing specific examples if possible.

- Acknowledge Limitations : Discuss any ethical limitations or constraints and how you plan to address them.

- Cite Ethical Guidelines : Refer to ethical standards set by organizations like the American Psychological Association (APA) or your institution’s guidelines.

Common Ethical Challenges and How to Address Them

- Participant Withdrawal : Always allow participants to withdraw at any time and explain how this will be managed in your research.

- Data Security : Ensure data protection by using secure servers, password-protected files, and, if needed, anonymizing data.

- Bias Prevention : Avoid leading questions or biased analysis methods that could influence results. Stay objective in interpretation.

- Reporting Sensitive Findings : Be mindful of sensitive results that could impact participants or the public. Use appropriate language and provide context.

Ethical considerations are foundational to conducting responsible, credible research. Addressing ethics not only safeguards participants but also upholds the integrity of the research process. By considering issues like informed consent, confidentiality, and minimizing harm, researchers can ensure that their work respects and protects all involved parties. This guide outlines the essential ethical components and provides a writing framework for addressing these considerations, ensuring that ethical practices are clearly communicated in any research endeavor.

- Resnik, D. B. (2020). The Ethics of Research with Human Subjects: Protecting People, Advancing Science, Promoting Trust . Springer.

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct . APA.

- Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2019). Principles of Biomedical Ethics . Oxford University Press.

- Flick, U. (2018). An Introduction to Qualitative Research . Sage Publications.

- Israel, M., & Hay, I. (2006). Research Ethics for Social Scientists: Between Ethical Conduct and Regulatory Compliance . Sage Publications.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and...

Dissertation vs Thesis – Key Differences

Literature Review – Types Writing Guide and...

APA Research Paper Format – Example, Sample and...

What is Research Topic – Ideas and Examples

Research Contribution – Thesis Guide

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Nih clinical research trials and you, guiding principles for ethical research.

Pursuing Potential Research Participants Protections

“When people are invited to participate in research, there is a strong belief that it should be their choice based on their understanding of what the study is about, and what the risks and benefits of the study are,” said Dr. Christine Grady, chief of the NIH Clinical Center Department of Bioethics, to Clinical Center Radio in a podcast.

Clinical research advances the understanding of science and promotes human health. However, it is important to remember the individuals who volunteer to participate in research. There are precautions researchers can take – in the planning, implementation and follow-up of studies – to protect these participants in research. Ethical guidelines are established for clinical research to protect patient volunteers and to preserve the integrity of the science.

NIH Clinical Center researchers published seven main principles to guide the conduct of ethical research:

Social and clinical value

Scientific validity, fair subject selection, favorable risk-benefit ratio, independent review, informed consent.

- Respect for potential and enrolled subjects

Every research study is designed to answer a specific question. The answer should be important enough to justify asking people to accept some risk or inconvenience for others. In other words, answers to the research question should contribute to scientific understanding of health or improve our ways of preventing, treating, or caring for people with a given disease to justify exposing participants to the risk and burden of research.

A study should be designed in a way that will get an understandable answer to the important research question. This includes considering whether the question asked is answerable, whether the research methods are valid and feasible, and whether the study is designed with accepted principles, clear methods, and reliable practices. Invalid research is unethical because it is a waste of resources and exposes people to risk for no purpose

The primary basis for recruiting participants should be the scientific goals of the study — not vulnerability, privilege, or other unrelated factors. Participants who accept the risks of research should be in a position to enjoy its benefits. Specific groups of participants (for example, women or children) should not be excluded from the research opportunities without a good scientific reason or a particular susceptibility to risk.

Uncertainty about the degree of risks and benefits associated with a clinical research study is inherent. Research risks may be trivial or serious, transient or long-term. Risks can be physical, psychological, economic, or social. Everything should be done to minimize the risks and inconvenience to research participants to maximize the potential benefits, and to determine that the potential benefits are proportionate to, or outweigh, the risks.

To minimize potential conflicts of interest and make sure a study is ethically acceptable before it starts, an independent review panel should review the proposal and ask important questions, including: Are those conducting the trial sufficiently free of bias? Is the study doing all it can to protect research participants? Has the trial been ethically designed and is the risk–benefit ratio favorable? The panel also monitors a study while it is ongoing.

Potential participants should make their own decision about whether they want to participate or continue participating in research. This is done through a process of informed consent in which individuals (1) are accurately informed of the purpose, methods, risks, benefits, and alternatives to the research, (2) understand this information and how it relates to their own clinical situation or interests, and (3) make a voluntary decision about whether to participate.

Respect for potential and enrolled participants

Individuals should be treated with respect from the time they are approached for possible participation — even if they refuse enrollment in a study — throughout their participation and after their participation ends. This includes:

- respecting their privacy and keeping their private information confidential

- respecting their right to change their mind, to decide that the research does not match their interests, and to withdraw without a penalty

- informing them of new information that might emerge in the course of research, which might change their assessment of the risks and benefits of participating

- monitoring their welfare and, if they experience adverse reactions, unexpected effects, or changes in clinical status, ensuring appropriate treatment and, when necessary, removal from the study

- informing them about what was learned from the research

More information on these seven guiding principles and on bioethics in general

This page last reviewed on March 16, 2016

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

Ethical considerations in research: Best practices and examples

Doing responsible research means keeping ethics considerations front and center. Ethical practices not only safeguard research participant welfare but also ensures the integrity of your findings. By rigorously applying ethical principles throughout the research process, you not only enhance the methodological robustness of your study but also amplify its potential for meaningful societal impact.

But what does good ethics in research look like?

From best practices to conducting ethical and impactful research, we explore the meaning and importance of research ethics in modern-day research.

Examples of ethical considerations in research

As a researcher, you're responsible for ethical research alongside your organization. Fulfilling ethical guidelines is critical. Organizations must see to it that employees follow best practices to protect participants' rights and well-being.

Keep the below considerations in mind when it comes to ethical considerations in research.

Voluntary participation

Nobody should feel like they're being forced to participate or pressured into doing anything they don't want to. That means giving people a choice and the ability to opt out at any time, even if they've already agreed to take part in the study.

Researchers must clearly communicate this right to participants. It's necessary for creating an environment where people feel comfortable declining or withdrawing without fear of negative consequences.

Informed consent

Informed consent isn't just an ethical consideration. It's a legal requirement as well. Participants must fully understand what they're agreeing to, including potential risks and benefits.

The best way to go about this is by using a consent form. Make sure you include:

Brief description of the study and research methods

Provide a clear, concise overview of your research goals and how you'll conduct the study. Use simple language so participants understand the nature of their involvement and what they'll be asked to do.

Potential benefits and risks of participating

Outline any possible advantages or drawbacks of taking part in the study. Be honest about potential risks, no matter how small. You’ll allow participants to make an informed decision about their involvement.

Length of the study

Specify how long the study will take. If it involves multiple sessions, provide details on timing and frequency. It means participants will be able to plan their commitment and decide if they can fully engage.

Contact information for the researcher and/or sponsor

Include your name, institution, and contact details. If there's a study sponsor, provide their information too so participants can reach out with questions or concerns before, during, or after the study.

Participant's right to withdraw

Clearly state that participants can leave the study at any time without consequences. Emphasize that withdrawal won't affect their relationship with the researcher or institution to reinforce the voluntary nature of participation.

Cultural sensitivity

Consider cultural differences when conducting research across diverse populations. It will increase the chance that your study is respectful, inclusive, and produces valid results. Understanding cultural context, adapting research methods, and using appropriate language are central steps in this process.

Include team members from various cultural backgrounds on your research team. They can provide valuable insights and help interpret results within the appropriate cultural context. Be mindful of cultural practices that might affect participation, such as scheduling around religious observances or respecting dietary restrictions.

Prioritizing cultural sensitivity will help you conduct more ethical research and likely obtain more accurate, meaningful results from diverse populations. As a result, you can build trust with participants and enhance the overall quality and applicability of your research findings.

Anonymity means that participants aren't identifiable in any way and includes:

- Email address

- Photographs

- Video footage

You need a way to anonymize research data so that it can't be traced back to individual participants. This may involve creating a new digital ID for participants that can’t be linked back to their original identity using numerical codes.

Confidentiality

Information gathered during a study must be kept confidential. Confidentiality helps to protect the privacy of research participants and also ensures that their information isn't disclosed to unauthorized individuals.

Here are some ways to ensure confidentiality.

Use a secure server to store data

Store all research data on encrypted servers with strong access controls. Regularly update security measures to protect against potential breaches. Doing so safeguards participant information from unauthorized access or cyber threats.

Remove identifying information from databases

Create separate databases for participant identifiers and research data. Use coded identifiers to link the two, as it prevents direct association between sensitive data and individual participants.

Use a third-party company for data management

Consider partnering with specialized data management firms. They often have advanced security protocols and expertise in handling sensitive information, which can add an extra layer of protection for your research data.

Limit record retention periods

Establish clear timelines for data retention. Delete or destroy participant records once they're no longer needed for research purposes to reduce the risk of accidental disclosure or unauthorized access over time.

Avoid public discussion of findings

Be cautious when discussing research in public settings. Refrain from sharing specific details that could potentially identify participants. Focus on aggregate results and general insights to maintain confidentiality.

Conflict of interest

Researchers must disclose any potential conflicts of interest that could influence their study or its outcomes. Such transparency is important for maintaining the integrity and credibility of scientific research. Conflicts of interest can arise from financial relationships, personal connections, or professional affiliations.

Key considerations for managing conflicts of interest include:

- Full disclosure : Openly declare any potential conflicts in research proposals, publications, and presentations.

- Mitigation strategies : Develop plans to minimize the impact of conflicts on research conduct and outcomes.

- Independent review : Seek evaluation from unbiased third parties to ensure objectivity in research design and analysis.

Addressing conflicts of interest proactively means you can maintain public trust and uphold the ethical standards of their field.

Potential for harm

The potential for harm is a major factor in deciding whether a research study should proceed. It can manifest in various forms, such as:

Psychological harm

Research may unintentionally cause stress, anxiety, or emotional distress. Carefully consider the psychological impact of your study design, questions, or tasks. Provide support resources if needed.

Social harm

Some studies might affect participants' relationships or social standing, so think about potential stigma or social consequences. Guarantee confidentiality to minimize risks to participants' social well-being.

Physical harm

While rare in many fields, some studies involve physical risks. Assess all potential physical dangers thoroughly. Implement safety measures and have emergency protocols in place.

Research findings or participation could sometimes lead to legal issues for subjects. Be aware of legal implications. Protect participants from potential legal consequences through careful study design and data handling.

Conduct an ethical review to identify possible harms. Be prepared to explain how you’ll minimize these harms and what support is available in case they do happen.

Ethical use of technology

As research increasingly moves online and incorporates emerging technologies, new ethical challenges arise. Researchers must carefully consider the implications of using digital tools for data collection and analysis. This includes addressing concerns about privacy, data security, and the potential for unintended consequences.

Key considerations for the ethical use of technology in research include:

- Data protection: Implement robust security measures to safeguard participant information collected through digital platforms

- Informed consent: Clearly explain how technology will be used in the study and any potential risks associated with digital data collection

- Algorithmic bias: Be aware of and mitigate potential biases in AI-driven data analysis tools to ensure fair and accurate results

With these issues addressed, you can benefit from technology while upholding ethical standards and protecting participants' rights.

Fair payment

One of the most important aspects of setting up a research study is deciding on fair compensation for your participants. Underpayment is a common ethical issue that shouldn't be overlooked. Properly rewarding participants' time is necessary for boosting engagement and obtaining high-quality data. While Prolific requires a minimum payment of £6.00 / $8.00 per hour, there are other factors you need to consider when deciding on a fair payment.

Institutional guidelines and minimum wage

Check your institution's reimbursement guidelines to see if they already have a minimum or maximum hourly rate. You can also use the national minimum wage as a reference point.

Level of effort and task complexity

Think about the amount of work you're asking participants to do. The level of effort required for a task, such as producing a video recording versus a short survey, should correspond with the reward offered.

Target population considerations

You also need to consider the population you're targeting. You may need to offer more as an incentive to attract research subjects with specific characteristics or high-paying jobs,

We recommend a minimum payment of £9.00 / $12.00 per hour, but we understand that payment rates can vary depending on a range of factors. Whatever payment you choose should reflect the amount of effort participants are required to put in and be fair to everyone involved.

Ethical research made easy with Prolific

At Prolific, we believe in making ethical research easy and accessible. The findings from the Fairwork Cloudwork report speak for themselves. Prolific was given the top score out of all competitors for minimum standards of fair work.

With over 25,000 researchers in our community, we're leading the way in revolutionizing the research industry. If you're interested in learning more about how we can support your research journey, sign up free to get started now .

You might also like

Building a better world with better data.

Follow us on

All Rights Reserved Prolific 2024

A guide to ethical considerations in research

Last updated

12 March 2023

Reviewed by

Miroslav Damyanov

Whether you are conducting a survey, running focus groups , doing field research, or holding interviews, the chances are participants will be a part of the process.

Taking ethical considerations into account and following all obligations are essential when people are involved in your research. Upholding academic integrity is another crucial ethical concern in all research types.

So, how can you protect your participants and ensure that your research is ethical? Let’s take a closer look at the ethical considerations in research and the best practices to follow.

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- The importance of ethical research

Research ethics are integral to all forms of research. They help protect participants’ rights, ensure that the research is valid and accurate, and help minimize any risk of harm during the process.

When people are involved in your research, it’s particularly important to consider whether your planned research method follows ethical practices.

You might ask questions such as:

Will our participants be protected?

Is there a risk of any harm?

Are we doing all we can to protect the personal data and information we collect?

Does our study include any bias?

How can we ensure that the results will be accurate and valid?

Will our research impact public safety?

Is there a more ethical way to complete the research?

Conducting research unethically and not protecting participants’ rights can have serious consequences. It can discredit the entire study. Human rights, dignity, and research integrity should all be front of mind when you are conducting research.

- How to conduct ethical research

Before kicking off any project, the entire team must be familiar with ethical best practices. These include the considerations below.

Voluntary participation

In an ethical study, all participants have chosen to be part of the research. They must have voluntarily opted in without any pressure or coercion to do so. They must be aware that they are part of a research study. Their information must not be used against their will.

To ensure voluntary participation, make it clear at the outset that the person is opting into the process.

While participants may agree to be part of a study for a certain duration, they are allowed to change their minds. Participants must be free to leave or withdraw from the study at any time. They don’t need to give a reason.

Informed consent

Before kicking off any research, it’s also important to gain consent from all participants. This ensures participants are clear that they are part of a research study and understand all of the information related to it.

Gaining informed consent usually involves a written consent form—physical or digital—that participants can sign.

Best practice informed consent generally includes the following:

An explanation of what the study is

The duration of the study

The expectations of participants

Any potential risks

An explanation that participants are free to withdraw at any time

Contact information for the research supervisor

When obtaining informed consent, you should ensure that all parties truly understand what they are signing and their obligations as a participant. There should never be any coercion to sign.

Anonymity is key to ensuring that participants cannot be identified through their data. Personal information includes things like participants’ names, addresses, emails, phone numbers, characteristics, and photos.

However, making information truly anonymous can be challenging, especially if personal information is a necessary part of the research.

To maintain a degree of anonymity, avoid gathering any information you don’t need. This will minimize the risk of participants being identified.

Another useful tool is data pseudonymization, which makes it harder to directly link information to a real person. Data pseudonymization means giving participants fake names or mock information to protect their identity. You could, for example, replace participants’ names with codes.

Confidentiality

Keeping data confidential is a critical aspect of all forms of research. You should communicate to all participants that their information will be protected and then take active steps to ensure that happens.

Data protection has become a serious topic in recent years and should be taken seriously. The more information you gather, the more important it is to heavily protect that data.

There are many ways to protect data, including the following:

Restricted access: Information should only be accessible to the researchers involved in the project to limit the risk of breaches.

Password protection : Information should not be accessible without access via a password that complies with secure password guidelines.

Encrypted data: In this day and age, password protection isn’t usually sufficient. Encrypting the data can help ensure its security.

Data retention: All organizations should uphold a data retention policy whereby data gathered should only be held for a certain period of time. This minimizes the risk of breaches further down the line.

In research where participants are grouped together (such as in focus groups), ask participants not to pass on what has been discussed. This helps maintain the group’s privacy.

Data falsification

Regardless of what your study is about or whether it involves humans, it’s always unethical to falsify data or information. That means editing or changing any data that has been gathered or gathering data in ways that skew the results.

Bias in research is highly problematic and can significantly impact research integrity. Data falsification or misrepresentation can have serious consequences.

Take the case of Korean researcher Hwang Woo-suk, for example. Woo-suk, once considered a scientific leader in stem-cell research, was found guilty of fabricating experiments in the field and making ethical violations. Once discovered, he was fired from his role and sentenced to two years in prison.

All conflicts of interest should be declared at the outset to avoid any bias or risk of fabrication in the research process. Data must be collected and recorded accurately, and analysis must be completed impartially.

If conflicts do arise during the study, researchers may need to step back to maintain the study’s integrity. Outsourcing research to neutral third parties is necessary in some cases.

Potential for harm

Another consideration is the potential for harm. When completing research, it’s important to ensure that your participants will be safe throughout the study’s duration.

Harm during research could occur in many forms.

Physical harm may occur if your participants are asked to perform a physical activity, or if they are involved in a medical study.

Psychological harm can occur if questions or activities involve triggering or sensitive topics, or if participants are asked to complete potentially embarrassing tasks.

Harm can be caused through a data breach or privacy concern.

A study can cause harm if the participants don’t feel comfortable with the study expectations or their supervisors.

Maintaining the physical and mental well-being of all participants throughout studies is an essential aspect of ethical research.

- Gaining ethical approval

Gaining ethical approval may be necessary before conducting some types of research.

The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advise that approval is likely required for studies involving people.

To gain approval, it’s necessary to submit a proposal to an Institutional Review Board (IRB). The board will check the proposal and ensure that the research aligns with ethical practices. It will allow the project to proceed if it meets requirements.

Not gaining appropriate approval could invalidate your study, so it’s essential to pay attention to all local guidelines and laws.

- The dangers of unethical practices

Not maintaining ethical standards in research isn’t just questionable—it can be dangerous too. Many historical cases show just how widespread the ramifications can be.

The case of Korean researcher Hwang Woo-suk shows just how critical it is to obtain information ethically and accurately represent findings.

A case in 1998, which involved fraudulent data reporting, further proves this point.

The study, now debunked, was completed by Andrew Wakefield. It suggested there may be a link between the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism in children. It was later found that the data was manipulated to show a causal link when there wasn’t one. Wakefield’s medical license was removed as a result, but the fraudulent study was still widely cited and continues to cause vaccine hesitancy among many parents.

Large organizational bodies have also been a part of unethical research. The alcohol industry, for example, was found to be highly influential in a major public health study in an attempt to prove that moderate alcohol consumption had health benefits. Five major alcohol companies pledged approximately $66 million to fund the study.

However, the World Health Organization (WHO) is clear that research shows there is no safe level of alcohol consumption. After pressure from many organizations, the study was eventually pulled due to biasing by the alcohol industry. Despite this, the idea that moderate alcohol consumption is better than abstaining may still appear in public discourse.

In more extreme cases, unethical research has led to medical studies being completed on people without their knowledge and against their will. The atrocities committed in Nazi Germany during World War II are an example.

Unethical practices in research are not just problematic or in conflict with academic integrity; they can seriously harm public health and safety.

- The ethical way to research

Considering ethical concerns and adopting best practices throughout studies is essential when conducting research.

When people are involved in studies, it’s important to consider their rights. They must not be coerced into participating, and they should be protected throughout the process.

Accurate reporting, unbiased results, and a genuine interest in answering questions rather than confirming assumptions are all essential aspects of ethical research.

Ethical research ultimately means producing true and valuable results for the benefit of everyone impacted by your study.

What are ethical considerations in research?

Ethical research involves a series of guidelines and considerations to ensure that the information gathered is valid and reliable. These guidelines ensure that:

People are not harmed during research

Participants have data protection and anonymity

Academic integrity is upheld

Not maintaining ethics in research can have serious consequences for those involved in the studies, the broader public, and policymakers.

What are the most common ethical considerations?

To maintain integrity and validity in research, all biases must be removed, data should be reported accurately, and studies must be clearly represented.

Some of the most common ethical guidelines when it comes to humans in research include avoiding harm, data protection, anonymity, informed consent, and confidentiality.

What are the ethical issues in secondary research?

Using secondary data is generally considered an ethical practice. That’s because the use of secondary data minimizes the impact on participants, reduces the need for additional funding, and maximizes the value of the data collection.

However, secondary research still has risks. For example, the risk of data breaches increases as more parties gain access to the information.

To minimize the risk, researchers should consider anonymity or data pseudonymization before the data is passed on. Furthermore, using the data should not cause any harm or distress to participants.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 9 November 2024

Last updated: 24 October 2024

Last updated: 11 January 2024

Last updated: 17 January 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 12 October 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 31 January 2024

Last updated: 23 January 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, a whole new way to understand your customer is here, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Legal and ethical issues in research

Camille yip, nian-lin reena han, ban leong sng.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Address for correspondence: Dr. Ban Leong Sng, 100 Bukit Timah Road, Singapore 229899. E-mail: [email protected]

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Legal and ethical issues form an important component of modern research, related to the subject and researcher. This article seeks to briefly review the various international guidelines and regulations that exist on issues related to informed consent, confidentiality, providing incentives and various forms of research misconduct. Relevant original publications (The Declaration of Helsinki, Belmont Report, Council for International Organisations of Medical Sciences/World Health Organisation International Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects, World Association of Medical Editors Recommendations on Publication Ethics Policies, International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, CoSE White Paper, International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use-Good Clinical Practice) form the literature that are relevant to the ethical and legal aspects of conducting research that researchers should abide by when conducting translational and clinical research. Researchers should note the major international guidelines and regional differences in legislation. Hence, specific ethical advice should be sought at local Ethics Review Committees.

Key words: Confidentiality, ethics, informed consent, legal issues, plagiarism, professional misconduct

INTRODUCTION

The ethical and legal issues relating to the conduct of clinical research involving human participants had raised the concerns of policy makers, lawyers, scientists and clinicians for many years. The Declaration of Helsinki established ethical principles applied to clinical research involving human participants. The purpose of a clinical research is to systematically collect and analyse data from which conclusions are drawn, that may be generalisable, so as to improve the clinical practice and benefit patients in future. Therefore, it is important to be familiar with Good Clinical Practice (GCP), an international quality standard that is provided by the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH),[ 1 ] or the local version, GCP of the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (India's equivalent of US Food and Drug Administration)[ 2 ] and local regulatory policy to ensure that the research is conducted both ethically and legally. In this article, we will briefly review the legal and ethical issues pertaining to recruitment of human subjects, basic principles of informed consent and precautions to be taken during data and clinical research publications. Some of the core principles of GCP in research include defining responsibilities of sponsors, investigators, consent process monitoring and auditing procedures and protection of human subjects.[ 3 ]

ISSUES RELATED TO THE RESEARCH PARTICIPANTS

The main role of human participants in research is to serve as sources of data. Researchers have a duty to ‘protect the life, health, dignity, integrity, right to self-determination, privacy and confidentiality of personal information of research subjects’.[ 4 ] The Belmont Report also provides an analytical framework for evaluating research using three ethical principles:[ 5 ]

Respect for persons – the requirement to acknowledge autonomy and protect those with diminished autonomy

Beneficence – first do no harm, maximise possible benefits and minimise possible harms

Justice – on individual and societal level.

Mistreatment of research subjects is considered research misconduct (no ethical review approval, failure to follow approved protocol, absent or inadequate informed consent, exposure of subjects to physical or psychological harm, exposure of subjects to harm due to unacceptable research practices or failure to maintain confidentiality).[ 6 ] There is also scientific misconduct involving fraud and deception.

Consent, possibility of causing harm

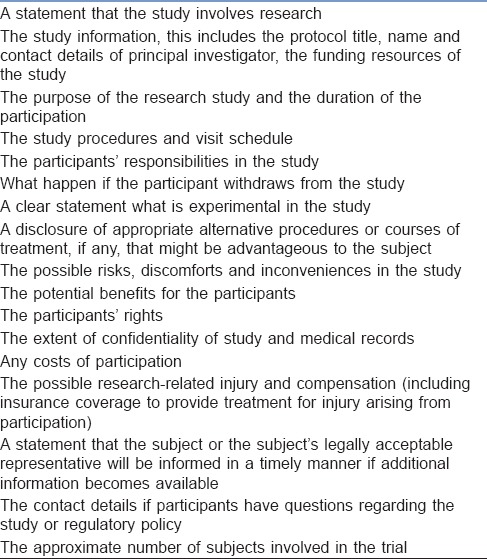

Based on ICH definition, ‘informed consent is a process by which a subject voluntarily confirms his or her willingness to participate in a particular trial, after having been informed of all aspects of the trial that are relevant to the subject's decision to participate’. As for a standard (therapeutic) intervention that carries certain risks, informed consent – that is voluntary, given freely and adequately informed – must be sought from participants. However, due to the research-centred, rather than patient-centred primary purpose, additional relevant information must be provided in clinical trials or research studies in informed consent form. The essential components of informed consent are listed in Table 1 [Adapted from ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline, Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R1)].[ 1 ] This information should be delivered in the language and method that individual potential subjects can understand,[ 4 ] commonly in the form of a printed Participant Information Sheet. Informed consent is documented by means of written, signed and dated informed consent form.[ 1 ] The potential subjects must be informed of the right to refuse to participate or withdraw consent to participate at any time without reprisal and without affecting the patient–physician relationship. There are also general principles regarding risk assessment, scientific requirements, research protocols and registration, function of ethics committees, use of placebo, post-trial provisions and research publication.[ 4 ]

Essential components of an informed consent

Special populations

Informed consent may be sought from a legally authorised representative if a potential research subject is incapable of giving informed consent[ 4 ] (children, intellectual impairment). The involvement of such populations must fulfil the requirement that they stand to benefit from the research outcome.[ 4 ] The ‘legally authorised representative’ may be a spouse, close relative, parent, power of attorney or legally appointed guardian. The hierarchy of priority of the representative may be different between different countries and different regions within the same country; hence, local guidelines should be consulted.

Special case: Emergency research

Emergency research studies occur where potential subjects are incapacitated and unable to give informed consent (acute head trauma, cardiac arrest). The Council for International Organisations of Medical Sciences/World Health Organisation guidelines and Declaration of Helsinki make exceptions to the requirement for informed consent in these situations.[ 4 , 7 ] There are minor variations in laws governing the extent to which the exceptions apply.[ 8 ]

Reasonable efforts should have been made to find a legal authority to consent. If there is not enough time, an ‘exception to informed consent’ may allow the subject to be enrolled with prior approval of an ethical committee.[ 7 ] Researchers must obtain deferred informed consent as soon as possible from the subject (when regains capacity), or their legally authorised representative, for continued participation.[ 4 , 7 ]

Collecting patient information and sensitive personal information, confidentiality maintenance

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act has requirements for informed consent disclosure and standards for electronic exchange, privacy and information security. In the UK, generic legislation is found in the Data Protection Act.[ 9 ]

The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) recommendations suggest that authors must ensure that non-essential identifying information (names, initials, hospital record numbers) are omitted during data collection and storage wherever possible. Where identifying information is essential for scientific purposes (clinical photographs), written informed consent must be obtained and the patient must be shown the manuscript before publication. Subjects should also be informed if any potential identifiable material might be available through media access.

Providing incentives

Cash or other benefits ‘in-kind’ (financial, medical, educational, community benefits) should be made known to subjects when obtaining informed consent without emphasising too much on it.[ 7 ] Benefits may serve as appreciation or compensation for time and effort but should not result in the inducement to participation.[ 10 ] The amount and nature of remuneration should be compared to norms, cultural traditions and are subjected to the Ethical Committee Review.[ 7 ]

ISSUES RELATED TO THE RESEARCHER

Legal issues pertaining to regulatory bodies.

Various regulatory bodies have been constituted to uphold the safety of subjects involved in research. It is imperative to obtain approval from the appropriate regulatory authorities before proceeding to any research. The constitution and the types of these bodies vary nation-wise. The researchers are expected to be aware of these authorities and the list of various bodies pertinent to India are listed in the article “Research methodology II” of this issue.

Avoiding bias, inappropriate research methodology, incorrect reporting and inappropriate use of information

Good, well-designed studies advance medical science development. Poorly conducted studies violate the principle of justice, as there are time and resources wastage for research sponsors, researchers and subjects, and undermine the societal trust on scientific enquiry.[ 11 ] The Guidelines for GCP is an international ethical and scientific quality standard for designing, conducting, recording and reporting trials.[ 1 ]

Fraud in research and publication

De novo data invention (fabrication) and manipulation of data (falsification)[ 6 ] constitute serious scientific misconduct. The true prevalence of scientific fraud is difficult to measure (2%–14%).[ 12 ]

Plagiarism and its checking

Plagiarism is the use of others' published and unpublished ideas or intellectual property without attribution or permission and presenting them as new and original rather than derived from an existing source.[ 13 ] Tools such as similarity check[ 14 ] are available to aid researchers detect similarities between manuscripts, and such checks should be done before submission.[ 15 ]

Overlapping publications

Duplicate publications violate international copyright laws and waste valuable resources.[ 16 , 17 ] Such publications can distort evidence-based medicine by double-counting of data when inadvertently included in meta-analyses.[ 16 ] This practice could artificially enlarge one's scientific work, distorting apparent productivity and may give an undue advantage when competing for research funding or career advancement.[ 17 ] Examples of these practices include:

Duplicate publication, redundant publication

Publication of a paper that overlaps substantially with one already published, without reference to the previous publication.[ 11 ]

Salami publication

Slicing of data from a single research process into different pieces creating individual manuscripts from each piece to artificially increase the publication volume.[ 16 ]

Such misconduct may lead to retraction of articles. Transparent disclosure is important when submitting papers to journals to declare if the manuscript or related material has been published or submitted elsewhere, so that the editor can decide how to handle the submission or to seek further clarification. Further information on acceptable secondary publication can be found in the ICMJE ‘Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publishing of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals’.

Usually, sponsors and authors are required to sign over certain publication rights to the journal through copyright transfer or a licensing agreement; thereafter, authors should obtain written permission from the journal/publisher if they wish to reuse the published material elsewhere.[ 6 ]

Authorship and its various associations

The ICMJE recommendation lists four criteria of authorship:

Substantial contributions to the conception of design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content

Final approval of the version to be published

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Authors and researchers have an ethical obligation to ensure the accuracy, publication and dissemination of the result of research,[ 4 ] as well as disclosing to publishers relevant corrections, retractions and errata, to protect scientific integrity of published evidence. Every research study involving human subjects must be registered in a publicly accessible database (e.g., ANZCTR [Australia and NZ], ClinicalTrials.gov [US and non-US], CTRI [India]) and the results made publicly available.[ 4 ] Sponsors of clinical trials must allow all study investigators and manuscript authors access to the full study data set and the right to use all study data for publication.[ 5 ] Source documents (containing trial data) and clinical study report (results and interpretation of trial) form part of the essential documentation that must be retained for a length of time prescribed by the applicable local legislation.[ 1 ] The ICMJE is currently proposing a requirement of authors to share with others de-identified individual patient data underlying the results presented in articles published in member journals.[ 18 ]

Those who have contributed to the work but do not meet all four criteria should be acknowledged; some of these activities include provision of administrative support, writing assistance and proofreading. They should have their written permission sought for their names to be published and disclose any potential conflicts of interest.[ 6 ] The Council of Scientific Editors has identified several inappropriate types of authorship, such as guest authorship, honorary or gift authorship and ghost authorship.[ 6 ] Various interventions should be put in place to prevent such fraudulent practices in research.[ 19 ] The list of essential documents for the conduct of a clinical trial is included in other articles of the same issue.

The recent increase in research activities has led to concerns regarding ethical and legal issues. Various guidelines have been formulated by organisations and authorities, which serve as a guide to promote integrity, compliance and ethical standards in the conduct of research. Fraud in research undermines the quality of establishing evidence-based medicine, and interventions should be put in place to prevent such practices. A general overview of ethical and legal principles will enable research to be conducted in accordance with the best practices.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- 1. International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. [monograph on the Internet] Geneva: 1996. [Last updated on 1996 Jun 10; Last cited on 2016 May 25]. ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline, Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R1), Current Step 4 Version. Available from: http://www.ich.org/products/guidelines/efficacy/efficacy-single/article/goodclinical-practice.html . [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Cdsco.nic.in [homepage in the Internet]. India 2014. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India online resources. Central Drugs Standard Control Organization. [Last cited on 2016 Aug 11]. Available from: http://www.cdsco.nic.in/html/GCP1.html ; http://www.cdsco.nic.in/forms/list.aspx?lid=1843&Id=31 .

- 3. Devine S, Dagher RN, Weiss KD, Santana VM. Good clinical practice and the conduct of clinical studies in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2008;55:187–209. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2007.10.008. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. hhs.gov [homepage on the Internet] Rockville: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Online Resource; [updated on 1979 Apr 18; cited on 2016 Aug 10]. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/index.html . [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Scott-Lichter D. CSE's White Paper on Promoting Integrity in Scientific Journal Publications, 2012 Update. 3rd Revised Edition. Wheat Ridge, CO; 2012. [Last accessed on 2016 Aug 08]. the Editorial Policy Committee, Council of Science Editors. Available from: http://www.councilscienceeditors.org/wp.content/uploads/entire_whitepaper.pdf . [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects. [monograph on the Internet] Geneva: 2002. [cited on 2016 Aug 10]. Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) in Collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) Available from: http://www.cioms.ch/publications/layout_guide2002.pdf . [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. van Belle G, Mentzelopoulos SD, Aufderheide T, May S, Nichol G. International variation in policies and practices related to informed consent in acute cardiovascular research: Results from a 44 country survey. Resuscitation. 2015;91:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.11.029. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Data Protection Act United Kingdom [monograph on the Internet] Norwich, UK: 1998. [updated on 1998 Jul 16; cited on 2016 Aug 14]. Her Majesty's Stationery Office and Queen's Printer of Acts of Parliament. Available from: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1998/29/introduction . [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Njue M, Molyneux S, Kombe F, Mwalukore S, Kamuya D, Marsh V. Benefits in cash or in kind? A community consultation on types of benefits in health research on the Kenyan Coast. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127842. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Mutch WA. Academic fraud: Perspectives from a lifelong anesthesia researcher. Can J Anaesth. 2011;58:782. doi: 10.1007/s12630-011-9523-5. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. George SL. Research misconduct and data fraud in clinical trials: Prevalence and causal factors. Int J Clin Oncol. 2016;21:15–21. doi: 10.1007/s10147-015-0887-3. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Recommendations on Publication Ethics Policies for Medical Journals: World Association of Medical Editors. [monograph on the Internet] Winnetka, IL, USA: 2016. [Last cited on 2016 May 17]. WAME Publication Ethics Committee. Available from: http://www.wame.org/about/recommendations-on-publication-ethicspolicie#Plagiarism . [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Crossref.org [homepage on Internet] Oxford Centre for Innovation, UK: 2016. [updated on 2016 Apr 26; cited on 2016 Aug 06]. Available from: http://www.crossref.org/crosscheck/index.html . [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Shafer SL. Plagiarism is ubiquitous. Anesth Analg. 2016;122:1776–80. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001344. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Abraham P. Duplicate and salami publications. J Postgrad Med. 2000;46:67–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Supak Smolcic V. Salami publication: Definitions and examples. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2013;23:237–41. doi: 10.11613/BM.2013.030. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Taichman DB, Backus J, Baethge C, Bauchner H, de Leeuw PW, Drazen JM, et al. Sharing clinical trial data: A proposal from the international committee of medical journal editors. JAMA. 2016;315:467–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18164. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Marusic A, Wager E, Utrobicic A, Rothstein HR, Sambunjak D. Interventions to prevent misconduct and promote integrity in research and publication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:MR000038. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000038.pub2. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (428.0 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. These principles include voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, potential for harm, and results communication.

There are several reasons why it is important to adhere to ethical norms in research. First, norms promote the aims of research, such as knowledge, truth, and avoidance of error. For example, prohibitions against fabricating, falsifying, or misrepresenting research data promote the truth and minimize error.

Ethical considerations should be written whenever research involves human subjects or has the potential to impact human beings, animals, or the environment in some way. Ethical considerations are also important when research involves sensitive topics, such as mental health, sexuality, or religion.

Ethical guidelines are established for clinical research to protect patient volunteers and to preserve the integrity of the science. NIH Clinical Center researchers published seven main principles to guide the conduct of ethical research: Social and clinical value. Scientific validity.

In this paper, we discuss core ethical and methodological considerations in the design and implementation of qualitative research in the COVID-19 era, and in pivoting to virtual methods—online interviews and focus groups; internet-based archival research and netnography, including social media; participatory video methods, including photo ...

Explore key ethical considerations in research, from informed consent to fair compensation. Learn how to conduct responsible studies that protect participants.

Ensuring that your research is conducted ethically is essential to protecting the welfare of your participants and the validity of your data. Learn more about ethical considerations in research.

Ethics in Research: A Comparative Study of Benefits and Limitations. August 2023. 7 (8):10-14. Authors: Abdul Awal. University of Lodz. References (16) Abstract. Ethics, as an integral...

Ethical considerations in research: a framework for practice. We conduct research to validate and improve our professional practice and to obtain generalizable knowledge. Through research we strive to better under-stand the natural history of diseases, human behavior, and outcomes of interventions.

Legal and ethical issues in research. Camille Yip. 1 Department of Women's Anaesthesia, KK Women's and Children's Hospital, Bukit Timah, Singapore. Find articles by Camille Yip. 1, Nian-Lin Reena Han. Nian-Lin Reena Han. 2 Division of Clinical Support Services, KK Women's and Children's Hospital, Bukit Timah, Singapore.