Save the Date

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 14, Issue 5

- How to manage alcohol-related liver disease: A case-based review

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1530-5328 James B Maurice 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5140-517X Samuel Tribich 2 ,

- Ava Zamani 3 ,

- Jennifer Ryan 4

- 1 Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Southmead Hospital , North Bristol NHS Trust , Bristol , UK

- 2 Department of Hepatology, Royal London Hospital , Barts Health NHS Trust , London , UK

- 3 Hammersmith Hospital , Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust , London , UK

- 4 Department of Hepatology and Liver Transplantation, Royal Free Hospital , Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust , London , UK

- Correspondence to Dr James B Maurice, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Southmead Hospital, North Bristol NHS Trust, Bristol BS10 5NB, UK; james.maurice{at}nbt.nhs.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/flgastro-2022-102270

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

- alcoholic liver disease

- chronic liver disease

What is already known on this topic

Alcohol-related liver disease (ArLD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality.

What this study adds

We present a typical case to illustrate current evidence-based investigation and management of a patient with ArLD.

This case-based review aims to concisely support the day-to-day decision making of clinicians looking after patients with ArLD, from risk stratification and fibrosis assessment in the community through to managing decompensated disease, escalation care to critical care and assessment for liver transplantation.

How this study might affect research, practice or policy

We summarise the evolving evidence for the benefit of liver transplantation in alcoholic hepatitis, and ongoing controversies shaping future research in this area.

ArLD is fundamentally a public health problem, and further efforts are required to implement effective policies to reduce consumption and prevent disease.

Introduction

Alcohol is the leading risk factor for premature death in young adults, of which alcohol-related liver disease (ArLD) is a major contributor. 1 The management of ArLD often requires complex decision-making, raising challenges for the clinician and wider multidisciplinary team. This case-based review follows the typical journey of a patient through the progressive stages of the disease process, from early diagnosis and risk stratification in the outpatient clinic through to alcoholic hepatitis and referral for liver transplantation. At each stage, we discuss a practical approach to clinical management and summarise the underlying evidence base.

Case part 1

A 47-year-old man is referred to the general hepatology clinic from his General Practitioner with abnormal liver function tests, ordered in the community following several episodes of non-specific abdominal pain which subsequently resolved. He is now asymptomatic. The referral states that he drinks one bottle of wine each weekday night and more at the weekends. He is on no regular medication, has no other significant medical history and works in construction. On clinical examination, there are a few …

Twitter @jamesbmaurice

Contributors JBM conceptualised the original article and the case. JBM, ST and AZ drafted the initial version of the manuscript. JBM and ST contributed further editing of various sections. JR provided senior critical review and edited the manuscript. All authors agreed upon the final version.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Linked Articles

- Highlights from this issue UpFront R Mark Beattie Frontline Gastroenterology 2023; 14 357-358 Published Online First: 07 Aug 2023. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2023-102519

Read the full text or download the PDF:

ANDREW SMITH, MD, KATRINA BAUMGARTNER, MD, AND CHRISTOPHER BOSITIS, MD

Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(12):759-770

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Cirrhosis is the 12th leading cause of death in the United States. Newer research has established that liver fibrosis is a dynamic process and that early cirrhosis may be reversible. Only one in three people with cirrhosis knows they have it. Most patients with cirrhosis remain asymptomatic until the onset of decompensation. When clinical signs, symptoms, or abnormal liver function tests are discovered, further evaluation should be pursued promptly. The most common causes of cirrhosis are viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Initial workup includes viral hepatitis serologies, ferritin, transferrin saturation, and abdominal ultrasonography as well as complete blood count, liver function tests, and prothrombin time/international normalized ratio, if not already ordered. Additional testing is based on demographics and risk factors. Common serum and ultrasound-based screening tests to assess fibrosis include the aspartate transaminase to platelet ratio index score, Fibrosis 4 score, FibroTest/FibroSure, nonalcoholic fatty liver fibrosis score, standard ultrasonography, and transient elastography. Generally, noninvasive tests are most useful in identifying patients with no to minimal fibrosis or advanced fibrosis. Chronic liver disease management includes directed counseling, laboratory testing, and ultrasound monitoring. Treatment goals are preventing cirrhosis, decompensation, and death. Varices are monitored with endoscopy and often require prophylaxis with nonselective beta blockers. Ascites treatment includes diuresis, salt restriction, and antibiotic prophylaxis for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, when indicated. Hepatic encephalopathy is managed with lifestyle and nutritional modifications and, as needed, with lactulose and rifaximin. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening includes ultrasound screening every six months for patients with cirrhosis.

Cirrhosis is a diffuse process of liver damage considered irreversible in its advanced stages. In 2016, more than 40,000 Americans died because of complications related to cirrhosis, making it the 12th leading cause of death in the United States. 1 Recent projections suggest that this number is likely to grow. 2 An estimated 630,000 Americans have cirrhosis, yet less than one in three knows it. 3 Important racial and socioeconomic disparities exist, with prevalence highest among non-Hispanic blacks, Mexican Americans, and those living below the poverty level. 3 Cirrhosis and advanced liver disease cost the United States between $12 billion and $23 billion dollars in health care expenses annually. 4 , 5

WHAT'S NEW ON THIS TOPIC

Estimates suggest that nonalcoholic steatohepatitis will become the leading cause of cirrhosis in U.S. patients awaiting liver transplantation sometime between 2025 and 2035.

Liver biopsy remains the reference standard; however, transient elastography has become more widely available and is rapidly replacing biopsy as the preferred method for liver fibrosis staging.

Newer guidelines suggest targeted screening for esophageal varices in patients with clinically significant portal hypertension rather than screening all patients with cirrhosis.

| , | Expert opinion and consensus guidelines in the absence of clinical trials | |

| Expert opinion and consensus guidelines with low-quality trials | ||

| Randomized controlled trials demonstrate acceptable survival benefits based on clinical criteria and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease results with some variability | ||

| Data from multiple randomized controlled trials demonstrate more benefit than harm regarding patient comfort and reduced hospitalization times | ||

| , , , | Randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses comparing nonselective beta blockers, endoscopic band ligation, and placebo or no therapy, which generally show a reduction in variceal hemorrhage | |

| Low-quality randomized controlled trials that demonstrate less recurrence of hepatic encephalopathy using lactulose and/or rifaximin | ||

| , , , | Multiple randomized controlled trials demonstrate a reduction in bacterial infections as well as mortality | |

| should be screened for gastroesophageal varices with endoscopy. Repeat endoscopy should be performed every one to two years if small varices are found and every two to three years if no varices are found. | Expert opinion, consensus guidelines, and unpublished studies in progress |

The most common causes of cirrhosis in the United States are viral hepatitis (primarily hepatitis C virus [HCV] and hepatitis B virus [HBV]), alcoholic liver disease, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. HCV remains the leading cause of cirrhosis in patients awaiting liver transplant. With an increasing prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in the United States, estimates suggest that non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, a severe progression of NAFLD characterized by inflammatory steatohepatitis, will become the leading cause of cirrhosis in patients awaiting liver transplant sometime between 2025 and 2035. 6 , 7 Table 1 lists common etiologies of cirrhosis. 8

| Viral hepatitis (hepatitis B, hepatitis C) |

| Alcoholic liver disease |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis |

| Storage diseases |

| Hemochromatosis |

| Wilson disease |

| Alpha -antitrypsin deficiency |

| Immune mediated |

| Autoimmune hepatitis (types 1, 2, and 3) |

| Primary biliary cholangitis |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis |

| Immunoglobulin G4 cholangiopathy |

| Cardiovascular |

| Veno-occlusive disease (Budd-Chiari syndrome) |

| Congestive heart failure |

| Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu disease) |

| Chronic biliary disease |

| Recurrent bacterial cholangitis |

| Bile duct stenosis |

| Other |

| Medications (e.g., methotrexate, amiodarone) |

| Erythropoietic protoporphyria |

| Sarcoidosis |

| Schistosomiasis |

Pathophysiology and Natural History of Cirrhosis

Chronic liver injury causes inflammation and hepatic fibrosis. Regardless of the cause, this can lead to the formation of fibrous septae and nodules, collapse of liver structures, and distortion of hepatic parenchyma and vascular architecture. Progressive fibrosis and cirrhosis subsequently result in decreased metabolic and synthetic hepatic function, causing a rise in bilirubin and decreased production of clotting factors and thrombopoietin, as well as splenic platelet sequestration, increased portal pressure, and the development of ascites and esophageal varices.

Cirrhosis can result from chronic liver damage of any cause. In patients with the three most common causes of liver disease, 10% to 20% will develop cirrhosis within 10 to 20 years. 9 Factors associated with an increased risk of progression to cirrhosis include increased age, medical comorbidities (particularly patients coinfected with HIV and HCV), and male sex (except in alcoholic liver disease, where females progress more rapidly). 10 The point at which this process becomes irreversible, however, is not clear. Newer research has established that liver fibrosis is a dynamic process and that even early cirrhosis is reversible. 11 Studies have demonstrated biopsy-proven fibrosis improvement rates as high as 88% after antiviral treatment in patients with HBV and HCV and as high as 85% after bariatric surgery in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. 12 , 13

After cirrhosis is established, a patient may remain clinically stable, or compensated, for years. Patients with compensated cirrhosis caused by HBV, HCV, and alcoholic liver disease develop clinical signs of decompensation, which include ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, jaundice, or bleeding, at a rate of 4% to 10% per year. 14 Variability of disease progression is influenced by the underlying cause and the presence or absence of treatment and ongoing liver injury. The median survival for those with compensated cirrhosis is 12 years, compared with two years once decompensation occurs. 15

Clinical Presentation

Most patients with compensated cirrhosis remain asymptomatic. When symptoms occur, they include fatigue, weakness, loss of appetite, right upper quadrant discomfort, and unexplained weight loss. With the onset of decompensation, patients may report symptoms of impaired liver function such as jaundice, portal hypertension (including ascites and peripheral edema), and hepatic encephalopathy (such as confusion and disordered sleep).

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Physical examination findings that may be present in patients with advanced liver disease (cirrhosis) are summarized in Table 2 . 16 , 17 The Stanford Medicine 25 website is a good resource for photos and instructional videos that demonstrate findings associated with cirrhosis ( http://stanfordmedicine25.stanford.edu/the25/liverdisease.html ). 16 , 17

| General | Muscle wasting |

| Central nervous system | Asterixis (tremor of the hand with wrist extension) |

| Drowsiness, confusion | |

| Head | Fetor hepaticus: sweet odor of the breath attributable to increased concentrations of dimethyl sulfide |

| Jaundice: may see yellowing of mucous membranes beneath the tongue | |

| Parotid enlargement | |

| Scleral icterus | |

| Spider nevi | |

| Chest | Gynecomastia |

| Spider nevi | |

| Thinning axillary hair | |

| Abdomen | Ascites |

| Caput medusae (engorged superficial epigastric veins radiating from the umbilicus) | |

| Contracted or enlarged liver | |

| Hemorrhoids | |

| Splenomegaly | |

| Hands and nails | Clubbing |

| Dupuytren contracture (progressive fibrosis of palmar fascia, resulting in limited extension of the fingers) | |

| Palmar erythema | |

| Terry nails (whiteness of proximal half of nail plate) | |

| Genitourinary (male) | Testicular atrophy |

| Lower extremities | Distal erythema |

| Edema | |

| Petechiae |

INITIAL LABORATORY FINDINGS

In early compensated disease, laboratory findings may be normal. Incidentally elevated liver enzymes or evidence of hepatic disease on imaging may prompt the initial suspicion of chronic liver injury. Findings suggestive of cirrhosis include low albumin (less than 3.5 g per dL [35 g per L]), thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 160 × 10 3 per μL [160 × 10 9 per L]), aspartate transaminase (AST):alanine transaminase (ALT) ratio greater than 1, elevated bilirubin, and a prolonged prothrombin time (PT)/elevated international normalized ratio (INR). 18

Evaluation of Chronic Liver Disease

When chronic liver disease is suspected, a history should be conducted, reviewing any potentially hepatotoxic medications, alcohol consumption, and family history of liver disease. Basic laboratory tests, including complete blood count, ALT, AST, albumin, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, total bilirubin, and PT/INR, should be ordered.

For those with clinical signs or symptoms of liver disease or abnormal liver function test results, regardless of duration, further evaluation to determine the potential etiology should be pursued promptly. 19 , 20 Viral hepatitis serologies, ferritin, transferrin saturation, and abdominal ultrasonography should be performed; complete blood count, liver function tests, and PT/INR should be completed, if not already ordered. If risk factors for NAFLD exist, testing of fasting lipid levels and A1C should be done. For patients with risk factors or demographics with concern for autoimmune hepatitis, antinuclear antibodies and smooth muscle antibodies should be tested. Table 3 lists additional suggested tests based on risk factors and clinical findings. 19 , 21 , 22

| Alcoholic liver disease | Positive screening tests for alcohol use disorder | Aspartate transaminase ≥ 2 times alanine transaminase level in 70% of patients, especially if 3 times |

| History of excessive alcohol intake | Elevated glucose tolerance test and/or mean corpuscular volume [corrected] | |

| Ultrasonography may show fatty change | ||

| Alpha -antitrypsin deficiency | Autosomal recessive trait | Alpha -antitrypsin phenotype |

| European ancestry | ||

| All other evaluations unrevealing | ||

| Autoimmune hepatitis | Young and middle-aged women (in type 1, the most common) | Antinuclear antibody and/or antismooth muscle antibody positive in titers ≥ 1:80 |

| Total serum immunoglobulin G (polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia > 1.5 times the upper limit of normal supports diagnosis) | ||

| Hemochromatosis | Autosomal recessive trait | Ferritin ≥ 250 to 300 ng per mL in men, ≥ 200 ng per mL in women |

| Northern European ancestry | Transferrin saturation (serum iron × 100/total iron-binding capacity) ≥ 45% | |

| If ferritin or transferrin saturation is abnormal, order human hemochromatosis protein gene mutation analysis | ||

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis | Obesity, diabetes mellitus | Lipids, A1C (not needed for diagnosis) |

| Improvement with weight loss | Ultrasonography may show fatty change | |

| May need biopsy to diagnose nonalcoholic steatohepatitis | ||

| Primary biliary cholangitis (primary biliary cirrhosis) | Associated with other autoimmune disorders (80% with Sjögren syndrome; 5% to 10% with autoimmune hepatitis) Middle-aged women | Cholestasis (elevated alkaline phosphatase and glucose tolerance test) Antimitochondrial antibody positive |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | Middle-aged men | Cholestasis (elevated alkaline phosphatase and glucose tolerance test) |

| Associated with inflammatory bowel disease (70%) | Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies positive in 70% of patients Frequently positive antinuclear antibodies, antismooth muscle antibodies, other antibodies Magnetic resonance cholangiography | |

| Viral hepatitis B (chronic) | Born in endemic country | Hepatitis B surface antigen |

| Hepatitis B core antibody | ||

| If either is positive, order hepatitis B virus DNA | ||

| Viral hepatitis C (chronic) | Born 1945 to 1965 | Anti–hepatitis C virus antibody |

| Specific risk factors for hepatitis C virus | If positive, order hepatitis C virus RNA | |

| Wilson disease | Autosomal recessive trait | Low serum ceruloplasmin |

| Age younger than 40 years with chronic liver disease or fatty liver and negative workup for the above | If abnormal, serum copper, urinary copper excretion, liver biopsy, hepatic tissue copper measurement, and genetic marker testing can be considered | |

| Kayser-Fleischer rings |

Staging Fibrosis and Diagnosing Cirrhosis

Liver fibrosis is scored on a scale from F0 to F4 ( Table 4 ) . 23 Differentiating between significant (F2 or greater) and advanced (F3 or greater) fibrosis and cirrhosis (F4) is difficult even with complete clinical, laboratory, and imaging data because findings are often nonspecific or insensitive. 24 Liver biopsy remains the reference standard for assessing liver fibrosis; however, use of noninvasive methods has become increasingly common in clinical practice. 18

| No fibrosis | F0 |

| Minimal scarring | F1 |

| Positive scarring with extension beyond area containing blood vessels | F2 |

| Bridging fibrosis with connection to other areas of fibrosis | F3 |

| Cirrhosis or advanced liver scarring | F4 |

Noninvasive testing includes serum-based and imaging modalities ( Table 5 25 – 37 ) . Generally, noninvasive tests are most useful in identifying patients with no to minimal fibrosis (F0) or advanced fibrosis (F3 to F4) and are less accurate at distinguishing early or intermediate stages of liver disease (F1 to F2). 24 , 38 They are most beneficial when combined with all available data, accounting for the pretest probability of fibrosis. 24 , 38

| AST to platelet ratio index score | AST, platelets | < 0.5: good NPV (80% in HCV) for significant fibrosis |

| > 2.0: high specificity for cirrhosis in HCV (46% sensitivity, 91% specificity) ; the World Health Organization recommended cutoff for HBV-related cirrhosis in low-resource settings (28% sensitivity, 87% specificity) , | ||

| Fibrosis 4 score | Age, platelets, AST, ALT | < 1.45: good NPV (95% in HCV) for advanced fibrosis |

| > 3.25 (range: 2.67 to 3.60): good PPV for advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis in HCV, HBV, and NAFLD , , | ||

| In HCV with ≥ 3.25, PPV for advanced fibrosis = 82% | ||

| In NAFLD with ≥ 2.67, PPV for advanced fibrosis = 80% | ||

| FibroTest/FibroSure | Alpha -macroglobulin, gamma-glutamyl transferase, haptoglobin, apolipoprotein A-I, bilirubin | < 0.30: good NPV (90%) for advanced fibrosis in NAFLD |

| > 0.48: high specificity for significant fibrosis in HCV (specificity = 85%) and HBV (specificity = 80%) | ||

| > 0.70: high specificity for advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis | ||

| In NAFLD with > 0.70, PPV for advanced fibrosis = 73% | ||

| In HBV with > 0.74, specificity for cirrhosis = 91% | ||

| NAFLD fibrosis score | Age, body mass index, AST, ALT, glucose, platelets, albumin | < −1.455: good NPV (88%) for advanced fibrosis in NAFLD |

| > 0.676: good PPV (82%) for advanced fibrosis in NAFLD | ||

| Transient elastography | Liver stiffness measured in kPa | HCV (> 12.5 kPa): high sensitivity (87%) and specificity (91%) for cirrhosis; very accurate for F2 to F4 when combined with FibroTest |

| HBV (> 9.0 to 12.0 kPa): good sensitivity (83%) and specificity (87%) but may be falsely elevated during flare-up | ||

| NAFLD (> 10.3 kPa): good NPV (98.5%) but lower PPV (56%) | ||

| Ultrasonography | Standard ultrasonography | Hepatic nodularity specific for severe fibrosis or cirrhosis in all forms of liver disease (sensitivity = 54%, specificity = 95%) |

| Evidence of portal hypertension (splenomegaly, portosystemic collaterals) |

Most serum tests show indirect markers of liver damage, except hyaluronic acid (found in the liver's extracellular matrix), which is included in biomarker panels such as FibroMeter or Hepascore. 24 The AST to platelet ratio index (APRI; https://www.mdcalc.com/ast-platelet-ratio-index-apri ), Fibrosis 4 score ( http://gihep.com/calculators/hepatology/fibrosis-4-score/ ), and NAFLD fibrosis score ( http://nafldscore.com/ ) are accessible, serum-based, nonproprietary calculations. 18 , 39 FibroTest (FibroSure in the United States), FibroMeter, and Hepascore are patented calculations using several serum biomarkers, with FibroTest being the most validated. 24

Biomarkers are most validated in chronic HCV, 40 with the exception of the NAFLD fibrosis score for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. 33 For other etiologies of liver disease, including alcoholic liver disease, few studies of noninvasive methods exist.

STANDARD ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Given its relatively low cost, accessibility, and lack of radiation, ultrasonography is useful for diagnosing cirrhosis, cirrhosis complications (e.g., splenomegaly, portal hypertension, ascites, hepatocellular carcinoma), and comorbid liver diseases (e.g., extrahepatic cholestasis). 24 Ultrasonography is good at detecting steatosis (94% sensitivity, 84% specificity), but it may frequently miss fibrosis or cirrhosis (for which it is 40% to 57% sensitive). 41 , 42 Characteristics of cirrhosis include hepatic nodularity, coarseness, and echogenicity, 24 with hepatic nodularity being the most specific. 36 Additionally, features consistent with portal hypertension, such as splenomegaly and portosystemic collaterals, are suggestive of cirrhosis. 37 Patients with cirrhosis and some with chronic HBV should undergo right upper quadrant ultrasonography every six months to screen for hepatocellular carcinoma. 43

TRANSIENT ELASTOGRAPHY

Transient elastography, which has become more widely available, is rapidly replacing biopsy as the preferred method for fibrosis staging. Transient elastography, an ultrasound technique performed with a specialized machine (Fibro-Scan), determines liver stiffness in kilopascals (kPa) by measuring the velocity of low-frequency elastic shear waves propagating through the liver. It is a five-minute procedure performed in an outpatient setting and provides point-of-care results. In a meta-analysis of more than 10,000 patients spanning multiple etiologies of liver disease, transient elastography was sensitive (81%) and specific (88%) for detecting liver fibrosis and cirrhosis 40 (see Table 5 25 – 37 for cutoff values). Transient elastography performs better than the biomarker-based tools in detecting cirrhosis and is accurate at excluding cirrhosis (negative predictive value greater than 90%). 38 Similar to serum tests, however, transient elastography is less accurate at distinguishing between intermediate stages of liver disease, and cutoff values vary depending on the etiology of liver disease and population studied. 24 , 38

LIMITATIONS

Abnormal serum results may be seen from non–liver-related causes, including bone marrow disease, hemolysis, and medications. Transient elastography is less reliable in patients with obesity (though an extra-large probe has been developed), ascites, excessive alcohol intake, and extrahepatic cholestasis. If performed during an episode of acute hepatic inflammation, these tests can also lead to falsely elevated results. 38

LIVER BIOPSY

Liver biopsy remains the reference standard in diagnosing cirrhosis; however, a 20% error rate still occurs in fibrosis staging. 44 Pathologic changes may be heterogeneous; therefore, sampling error is common, and interpretation should be made by an experienced pathologist using validated scoring systems. 38 Liver biopsy is recommended when concern for fibrosis remains after indeterminate or conflicting clinical, laboratory, and imaging results; in those for whom transient elastography is not suitable; or to clarify etiology of disease after inconclusive noninvasive evaluation. 9 Liver biopsy may be indicated to diagnose necroinflammation (in HBV) and steatohepatitis (nonalcoholic steatohepatitis) because they are not easily distinguished by noninvasive methods.

Staging Cirrhosis

After the diagnosis of cirrhosis is established, Child-Pugh ( https://www.mdcalc.com/child-pugh-score-cirrhosis-mortality ) and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease ( https://www.mdcalc.com/meld-score-model-end-stage-liver-disease-12-older ) scores should be used to identify the stage of cirrhosis and mortality risk, respectively. 9 , 45 A Child-Pugh grade B classification (seven to nine points) is consistent with early hepatic decompensation, 46 whereas a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score of 12 or more is predictive of increased risk for cirrhosis complications. 9

Cirrhosis Management

The primary goals of liver disease management are to prevent cirrhosis complications, liver decompensation, and death. These goals are accomplished with rigorous prevention counseling, monitoring, and management by primary care physicians, in consultation with subspecialists as needed.

PREVENTION COUNSELING

For all patients with liver disease, counseling points should be discussed, including avoidance of alcohol; maintenance of a healthy weight; nutrition; medication and supplement review; prevention of infections (including receiving vaccinations); screening and treatment of causative factors; and avoidance of unnecessary surgical procedures. Table 6 provides more details on counseling for patients with chronic liver disease. 7 , 9 , 18 , 21 , 45 , 47 – 52

| Alcohol use | Brief physician counseling, behavioral counseling, and group support |

| Complete alcohol abstinence in cirrhosis | |

| Medication-assisted treatment for alcohol use disorder | |

| Avoid naltrexone and acamprosate in patients with Child-Pugh grade C cirrhosis , | |

| Baclofen (Lioresal), 5 mg three times daily for three days, then 10 mg three times daily can be used, even with ascites , | |

| Avoidance of unnecessary surgical procedures | Cirrhosis, especially if decompensated or with Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score ≥ 14, increases perioperative mortality risk ; an online calculator has been developed to help guide decision-making ( ) |

| Coffee consumption | Three to four cups of coffee per day may reduce the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and fibrosis progression in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatitis C virus infection |

| Infection prevention: bacterial exposures | Avoid exposure to brackish/salt water and consumption of raw seafood ( can be fatal in patients with cirrhosis, iron overload, or immunocompromise) |

| Avoid unpasteurized dairy (risk of serious infections in patients with cirrhosis) | |

| Infection prevention: vaccinations | All patients with liver disease should receive yearly influenza vaccinations and hepatitis A and B vaccinations if not known to be immune |

| In patients with cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis B virus infection, 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (Pneumovax 23) is recommended | |

| Medication and supplement review | For patients with cirrhosis |

| Analgesics: acetaminophen preferred, limit to 2 g per day 7; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs contraindicated , ; low-dose tramadol may be used for severe symptoms of pain | |

| Antihypertensives: discontinue if patient has hypotension or ascites (linked to hepatorenal syndrome and mortality) | |

| Aspirin: low-dose aspirin may be continued if cardiovascular disease severity exceeds the severity of cirrhosis | |

| Metformin: should be continued for patients with diabetes mellitus | |

| Proton pump inhibitors: avoid unnecessary use (linked to increased risk of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis) | |

| Sedating medications: avoid benzodiazepines and opiates, especially in hepatic encephalopathy; hydroxyzine or trazodone may be considered for severe insomnia | |

| Statins: may be safely used | |

| Supplements: avoid daily dosage of vitamin A > 5,000 IU (may increase fibrosis production); avoid multivitamins with iron | |

| Obesity and diabetes management | Maximize obesity and diabetes management because they increase the risk of cirrhosis , |

| Weight loss of 10% improves histopathologic features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, including fibrosis | |

| Screening for and treatment of underlying causative factors of liver disease | Treatment of alcohol use disorder, chronic hepatitis B or C virus infection, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease can prevent progression and complications of liver disease and can improve fibrosis levels, even in patients with cirrhosis |

MONITORING OF PATIENTS WITH CIRRHOSIS

For patients with cirrhosis, a basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, complete blood count, and PT/INR should be completed every six months to recalculate Child-Pugh and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease scores. Patients with a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score of 15 or higher should be referred for liver transplantation evaluation 37 , 45 ; patients with ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, or variceal hemorrhage should also be referred. 37 , 53

Screening and Management for Specific Complications

Patients with cirrhosis are at risk of multiple complications, including hepatic decompensation, hepatocellular carcinoma, and other more common conditions (e.g., malnutrition, leg cramps, umbilical hernias). Table 7 includes specific recommendations for the screening and management of select complications of cirrhosis. 7 , 9 , 43 , 45 , 46 , 49 , 53 – 55

| Abdominal hernia | Clinical | Defer surgery until medically optimized and ascites controlled | High perioperative risk and hernia recurrence in presence of ascites |

| Increased risk with ascites | Consult with multidisciplinary team | ||

| Surgeon with experience in the care of patients with cirrhosis is best | |||

| Ascites | Clinical Paracentesis if new-onset moderate to severe ascites or if concern for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | Moderate (grade 2) and severe (grade 3) ascites: Diuresis with mineralocorticoids for treatment and prophylaxis Salt restriction < 2 g per day 7; no added salt; avoid preprepared meals , Fluid restriction usually not helpful Large (grade 3) ascites: Paracentesis: large-volume paracentesis with albumin infusion | Spironolactone, 100 mg per day Titrate every three days to maximum of 400 mg daily Goal of no more than 1.1 to 2.2 lb (0.5 to 1 kg) daily of weight loss Add furosemide (Lasix; or torsemide [Demadex]) if not responsive to spironolactone alone or if limiting adverse effects occur (e.g., hyperkalemia , ) Decrease to lowest effective dosage |

| Esophageal varices | EGD at diagnosis of cirrhosis May defer EGD if compensated, transient elastography with liver stiffness < 20 kPa, and platelets > 150,000 per mm (< 5% probability of high-risk varices) Repeat EGD if decompensation develops; if no varices (every two to three years ); if small varices (every one to two years ); or if medium or large varices or high-risk timing of repeat EGD varies | Medium, large, or high-risk varices (red wale markings): Endoscopic band ligation or nonselective beta blocker for prophylaxis , , , Prophylaxis with nonselective beta blocker should be indefinite | Propranolol, 20 to 40 mg twice daily; maximum: 160 to 320 mg per day Nadolol (Corgard), 20 to 40 mg daily; maximum: 80 to 160 mg per day Carvedilol (Coreg), 6.25 mg daily; maximum: 12.5 mg per day Titrate every two to three days; goal 25% heart rate reduction, keep heart rate > 55 beats per minute , , Discontinue if hemodynamic instability: sepsis, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, acute gastrointestinal bleeding, refractory ascites, systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg, sodium concentration < 120 to 130 mEq per L (120 to 130 mmol per L), or acute kidney injury , |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | Clinical | Reverse precipitants | Lactulose syrup, 25 mL every one to two hours until two soft bowel movements per day Titrate to two to three soft bowel movements per day Rifaximin, 550 mg orally twice per day , |

| Exclude other causes | Nutritional support | ||

| Ammonia levels should not be used for diagnosis or monitoring , | Medications First episode: lactulose for treatment and prophylaxis Second episode: add rifaximin (Xifaxan) for prophylaxis | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Right upper quadrant ultrasonography every six months for all patients with cirrhosis and in certain patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection without cirrhosis , | Treat obesity, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, diabetes mellitus, and hepatitis B virus infection | Refer to hepatologist for suspicious findings |

| Leg cramps | Clinical | Manage electrolytes | Baclofen, 10 mg per day, titrate weekly up to 30 mg per day |

| Especially if taking diuretics | Baclofen (Lioresal) as needed and tolerated | ||

| Malnutrition | Clinical | Multivitamin | Avoid protein restriction, even during hepatic encephalopathy Because of the increased risk of osteoporosis in chronic cholestasis and cirrhosis, performing a bone mineral density scan at the time of liver disease diagnosis or liver transplantation evaluation should be considered |

| Especially if new hepatic encephalopathy | Small frequent meals and late-night snack | ||

| Protein intake of 1 to 1.5 g per kg per day, with supplementation as needed , | |||

| Consider bone mineral density scan | |||

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | Clinical Paracentesis if suspicion of disease (new or worsening ascites, gastrointestinal bleeding, hemodynamic instability, fever or signs of systemic inflammation, gastrointestinal symptoms, worsening liver or kidney function, new or worsening hepatic encephalopathy) Diagnosis Ascitic fluid neutrophil count > 250 per mm | Treatment (empiric, IV antibiotics): Community-acquired bacterial peritonitis: third-generation cephalosporin or piperacillin/tazobactam (Zosyn) Prophylaxis per criteria: Ceftriaxone IV if acute gastrointestinal bleeding and Child-Pugh grade B/C Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or ciprofloxacin oral if acute gastrointestinal bleeding and Child-Pugh grade A [corrected] History of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, ascitic protein < 1.5 g per dL and advanced liver disease (Child-Pugh score ≥ 9 or bilirubin ≥ 3 mg per dL) or kidney disease (creatinine ≥ 1.2 mg per dL, sodium ≤ 130 mmol per L) , , , | Treatment dosing: Cefotaxime, 2 g IV every eight to 12 hours Ceftriaxone, 2 g IV every 24 hours Piperacillin/tazobactam, 3.375 g IV every six hours Prophylactic dosing: Ceftriaxone, 1 g IV per day for seven days Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, one 800-mg/160-mg tablet per day Ciprofloxacin, 500 mg per day Norfloxacin, 400 mg per day (not available in United States) Routine use of antibiotic prophylaxis in ascites without spontaneous bacterial peritonitis or acute gastrointestinal bleeding is not recommended |

COMMON COMPLICATIONS IN DECOMPENSATED CIRRHOSIS

Ascites, which develops in 5% to 10% of patients with cirrhosis per year, leads to decreased quality of life, frequent hospitalizations, and directly increases risk of further complications such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, umbilical hernias, and respiratory compromise. It also portends a poor prognosis, with a 30% five-year survival. 53 Hepatic encephalopathy, which occurs in 5% to 25% of patients within five years of a cirrhosis diagnosis, is likewise associated with increased medical cost and mortality, with a reported 15% inpatient mortality rate. 54

SCREENING FOR VARICES

Portal hypertension predisposes patients with cirrhosis to develop esophageal varices. Patients with varices have a one in three chance of developing a variceal bleed in the two years after diagnosis, with a 20% to 40% mortality rate per episode. 45 Endoscopy is the preferred screening method for esophageal varices. Many experts and guidelines recommend screening all patients with cirrhosis 9 ; however, newer recommendations suggest targeted screening of patients with clinically significant portal hypertension. 46 A liver stiffness greater than 20 kPa, alone or combined with a low platelet count (less than 150,000 per mm 3 ) and increased spleen size, and/or the presence of portosystemic collaterals on imaging may be sufficient to diagnose clinically significant portal hypertension and warrant endoscopic screening for varices. Repeat endoscopy should be performed every one to two years if small varices are found and every two to three years if no varices are found. 46

Consultation

Varices, hepatic encephalopathy, and ascites herald hepatic decompensation; these conditions warrant referral for subspecialist evaluation. The management of acute or refractory complications of cirrhosis (e.g., spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, acute gastrointestinal bleeding, hepatorenal syndrome, unresponsive portal hypertension, hepatic encephalopathy, ascites) is best addressed in the inpatient or referral setting.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Starr and Raines , 56 Heidelbaugh and Bruderly , 57 and Riley and Bhatti . 58

Data Sources: A literature search was completed in Medline via Ovid, EBSCOhost, DynaMed, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews using the keywords cirrhosis, end stage liver disease, management of liver disease, and liver fibrosis staging. Additionally, the EE+Evidence Summary literature search sent by the AFP medical editors was reviewed. Search dates: November 26, 2018; December 27, 2018; and August 7, 2019.

Kochanek KD, Murphy S, Xu J, et al. Mortality in the United States, 2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017(293):1-8.

Best AF, Haozous EA, Berrington de Gonzalez A, et al. Premature mortality projections in the USA through 2030: a modelling study [published correction appears in Lancet Public Health . 2018;3(8):e364]. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(8):e374-e384.

Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, et al. The epidemiology of cirrhosis in the United States: a population-based study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(8):690-696.

Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, et al. Burden and cost of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic diseases in the United States: update 2018 [published correction appears in Gastroenterology . 2019;156(6):1936]. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(1):254-272.e11.

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The burden of digestive diseases in the United States. January 2008. Accessed January 4, 2019. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/about-niddk/strategic-plans-reports/burden-of-digestive-diseases-in-united-states

Wong RJ, Aguilar M, Cheung R, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(3):547-555.

Ge PS, Runyon BA. Treatment of patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):767-777.

Wiegand J, Berg T. The etiology, diagnosis and prevention of liver cirrhosis: part 1 of a series on liver cirrhosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110(6):85-91.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cirrhosis in over 16s: assessment and management. NICE guideline [NG50]. July 2016. Accessed May 28, 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng50

Poynard T, Mathurin P, Lai CL, et al.; PANFIBROSIS Group. A comparison of fibrosis progression in chronic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2003;38(3):257-265.

Bonis PA, Friedman SL, Kaplan MM. Is liver fibrosis reversible?. N Engl JMed. 2001;344(6):452-454.

Jung YK, Yim HJ. Reversal of liver cirrhosis: current evidence and expectations. Korean J Intern Med. 2017;32(2):213-228.

Lassailly G, Caiazzo R, Buob D, et al. Bariatric surgery reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in morbidly obese patients. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):379-388.

Asrani SK, Kamath PS. Natural history of cirrhosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15(2):308.

D'Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol. 2006;44(1):217-231.

Stanford Medicine. Liver disease, head to foot. Accessed January 4, 2019. http://stanfordmedicine25.stanford.edu/the25/liverdisease.html

Reuben A. The liver has a body—a Cook's tour. Hepatology. 2005;41(2):408-415.

Udell JA, Wang CS, Tinmouth J, et al. Does this patient with liver disease have cirrhosis?. JAMA. 2012;307(8):832-842.

Oh RC, Hustead TR, Ali SM, et al. Mildly elevated liver transaminase levels: causes and evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(11):709-715. Accessed August 28, 2019. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2017/1201/p709.html

Newsome PN, Cramb R, Davison SM, et al. Guidelines on the management of abnormal liver blood tests. Gut. 2018;67(1):6-19.

O'Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ Practice Guideline Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):307-328.

Bacon BR, Adams PC, Kowdley KV, et al.; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of hemochromatosis: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2011;54(1):328-343.

Wilkins T, Akhtar M, Gititu E, et al. Diagnosis and management of hepatitis C. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(12):835-842. Accessed August 28, 2019. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2015/0615/p835.html

Lurie Y, Webb M, Cytter-Kuint R, et al. Non-invasive diagnosis of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(41):11567-11583.

Lin ZH, Xin YN, Dong QJ, et al. Performance of the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for the staging of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: an updated meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2011;53(3):726-736.

Parikh P, Ryan JD, Tsochatzis EA. Fibrosis assessment in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(3):40.

World Health Organization. Guidelines for the prevention, care and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis B infection. March 2015. Accessed January 4, 2019. https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/hepatitis/hepatitis-b-guidelines/en/

Vallet-Pichard A, Mallet V, Nalpas B, et al. FIB-4: an inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV infection. Comparison with liver biopsy and Fibrotest. Hepatology. 2007;46(1):32-36.

Shah AG, Lydecker A, Murray K, et al.; Nash Clinical Research Network. Comparison of noninvasive markers of fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(10):1104-1112.

Ratziu V, Massard J, Charlotte F, et al.; LIDO Study Group; CYTOL Study Group. Diagnostic value of biochemical markers (FibroTest-FibroSURE) for the prediction of liver fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:6.

Imbert-Bismut F, Ratziu V, Pieroni L, et al.; MULTIVIRC Group. Biochemical markers of liver fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C virus infection: a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;357(9262):1069-1075.

Salkic NN, Jovanovic P, Hauser G, et al. FibroTest/Fibrosure for significant liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis B: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(6):796-809.

Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G, et al. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology. 2007;45(4):846-854.

Castéra L, Vergniol J, Foucher J, et al. Prospective comparison of transient elastography, Fibrotest, APRI, and liver biopsy for the assessment of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(2):343-350.

Hashemi SA, Alavian SM, Gholami-Fesharaki M. Assessment of transient elastography (FibroScan) for diagnosis of fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Caspian J Intern Med. 2016;7(4):242-252.

Colli A, Fraquelli M, Andreoletti M, et al. Severe liver fibrosis or cirrhosis: accuracy of US for detection—analysis of 300 cases. Radiology. 2003;227(1):89-94.

Martin P, DiMartini A, Feng S, et al. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Hepatology. 2014;59(3):1144-1165.

European Association for Study of Liver; Asociacion Latinoamericana para el Estudio del Higado. EASL-ALEH Clinical Practice Guidelines: non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis. J Hepatol. 2015;63(1):237-264.

Noureddin M, Loomba R. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: indications for liver biopsy and noninvasive biomarkers. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2012;1(4):104-107.

Geng XX, Huang RG, Lin JM, et al. Transient elastography in clinical detection of liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(4):294-303.

Bonekamp S, Kamel I, Solga S, et al. Can imaging modalities diagnose and stage hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis accurately?. J Hepatol. 2009;50(1):17-35.

Saverymuttu SH, Joseph AE, Maxwell JD. Ultrasound scanning in the detection of hepatic fibrosis and steatosis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;292(6512):13-15.

Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68(2):723-750.

Afdhal NH. Diagnosing fibrosis in hepatitis C: is the pendulum swinging from biopsy to blood tests?. Hepatology. 2003;37(5):972-974.

Herrera JL, Rodríguez R. Medical care of the patient with compensated cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2006;2(2):124-133.

Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, et al. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases [published correction appears in Hepatology . 2017;66(1):304]. Hepatology. 2017;65(1):310-335.

Addolorato G, Mirijello A, Leggio L, et al. Management of alcohol dependence in patients with liver disease. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(4):287-299.

Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of baclofen for maintenance of alcohol abstinence in alcohol-dependent patients with liver cirrhosis: randomised, double-blind controlled study. Lancet. 2007;370(9603):1915-1922.

Runyon BA. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: update 2012. Accessed August 20, 2019. https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/2019-06/141020_Guideline_Ascites_4UFb_2015.pdf

Wadhawan M, Anand AC. Coffee and liver disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2016;6(1):40-46.

Zhang X, Harmsen WS, Mettler TA, et al. Continuation of metformin use after a diagnosis of cirrhosis significantly improves survival of patients with diabetes. Hepatology. 2014;60(6):2008-2016.

Glass LM, Dickson RC, Anderson JC, et al. Total body weight loss of ≥ 10% is associated with improved hepatic fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(4):1024-1030.

European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis [published correction appears in J Hepatol . 2018;69(5):1207]. J Hepatol. 2018;69(2):406-460.

Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60(2):715-735.

Terrault NA, Lok AS, McMahon BJ, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67(4):1560-1599.

Starr SP, Raines D. Cirrhosis: diagnosis, management, and prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(12):1353-1359. Accessed August 28, 2019. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2011/1215/p1353.html

Heidelbaugh JJ, Bruderly M. Cirrhosis and chronic liver failure: part I. Diagnosis and evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(5):756-762. Accessed August 28, 2019. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2006/0901/p756.html

Riley TR, Bhatti AM. Preventive strategies in chronic liver disease: part II. Cirrhosis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(10):1735-1740. Accessed August 28, 2019. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2001/1115/p1735.html

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2019 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

Cirrhosis of the Liver Ch. 44 Case Study

Published by Elfreda Cunningham Modified over 9 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "Cirrhosis of the Liver Ch. 44 Case Study"— Presentation transcript:

Hepatocirrhosis Liver cirrhosis.

Gallbladder Disease Candice W. Laney Spring 2014.

HEPATIC FAILURE TITO A. GALLA. HEALTHY LIVER LIVER FUNCTION METABOLISM DETOXIFICATION PROCESS PROTEIN SYNTHESIS MANUFACTURE OF CLOTTING FACTOR.

Pancreatitis Acute pancreatitis. Definition Is an inflamation of the pancreas ranging from mild edema to extensive hemorrhage the structure and function.

: foul mouth odor, bad breath Etiology: poor dental hygiene, lung or intestinal disorder S/S: bad breath TX: proper dental hygiene,

Cirrhosis of the Liver. Hepatic Cirrhosis It is a chronic progressive disease characterized by: - replacement of normal liver tissue with diffuse fibrosis.

Hepatic Working knowledge of physiological changes during disease process & effects on nutrition care.

Cirrhosis Biol E-163 TA session 1/8/06. Cirrhosis Fibrosis (accumulation of connective tissue) that progresses to cirrhosis Replacement of liver tissue.

CDI Education Cirrhosis 4/17/2017.

Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology II Pancreas and Liver Nancy Long Sieber Ph.D. December 13, 2010.

Cirrhosis of the Liver Kayla Shoaf.

Cirrhosis of the Liver (relates to Chapter 42, “Nursing Management: Liver, Biliary Tract, and Pancreas Problems,” in the textbook)

Liver pathology: CIRRHOSIS

Liver Cirrhosis S. Diana Garcia

HEPATIC DISORDERS NUR – 224. LEARNING OUTCOMES Explain liver function tests. Relate jaundice, portal hypertension, ascites, varices, nutritional deficiencies.

Hepatic Encephalopathy in End-Stage Liver Disease Megan Dudley End of Life Care for Adults and Families The University of Iowa College of Nursing 1.

Liver, Gall Bladder, and Pancreatic Disease. Manifestations of Liver Disease Inflammation - Hepatitis –Elevated AST, ALT –Steatosis –Enlarged Liver Portal.

Pre and Post Operative Nursing Management

By: Michelle Russell Case Study Presentation NUR 4216L

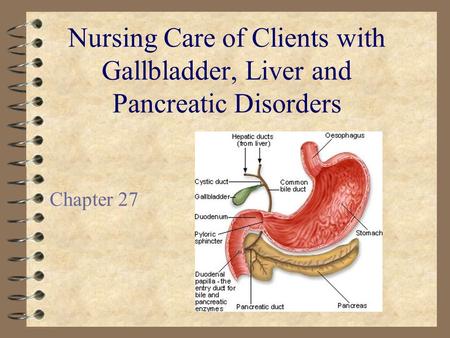

Nursing Care of Clients with Gallbladder, Liver and Pancreatic Disorders Chapter 27.

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

Understanding Liver Cirrhosis: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment Options

Apr 11, 2023

120 likes | 201 Views

Liver cirrhosis is a chronic liver disease that results in scarring and damage to liver tissue, affecting liver function and overall health. Learn about the causes, symptoms, and treatment options available to manage this condition.<br><br>TO know more check here : https://www.livertransplantinternational.com/liver-cirrhosis/

Share Presentation

Presentation Transcript

Understanding Liver Cirrhosis

Introduction • Definition of liver cirrhosis • Causes of liver cirrhosis • Symptoms of liver cirrhosis • Importance of early detection and treatment

What is Liver Cirrhosis? • A chronic liver disease that results in scarring and damage to liver tissue • Scar tissue replaces healthy liver tissue, making it difficult for the liver to function properly • Liver function is critical to overall health and well-being

Causes of Liver Cirrhosis • Alcohol abuse • Hepatitis B and C • Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease • Autoimmune disorders • Inherited diseases

Symptoms of Liver Cirrhosis • Fatigue and weakness • Loss of appetite • Nausea and vomiting • Weight loss • Jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes) • Abdominal pain and swelling • Itchy skin • Dark urine and pale stools

Diagnosis of Liver Cirrhosis • Blood tests to check liver function • Imaging tests, such as ultrasound or CT scan • Liver biopsy to confirm diagnosis and determine severity of liver damage

Treatment of Liver Cirrhosis • Treating the underlying cause, such as stopping alcohol abuse or treating viral hepatitis • Medications to manage symptoms and complications, such as diuretics to reduce fluid buildup • Liver transplant for severe cases

Complications of Liver Cirrhosis • Portal hypertension, which can lead to varices and bleeding • Ascites, which is fluid buildup in the abdomen • Hepatic encephalopathy, which is a brain disorder caused by liver failure • Liver cancer

Prevention of Liver Cirrhosis • Limit alcohol intake • Practice safe sex and get vaccinated for hepatitis B • Maintain a healthy weight and diet • Avoid exposure to harmful chemicals

Conclusion • Liver cirrhosis is a serious condition that can have severe complications • Early detection and treatment can help manage symptoms and prevent further damage • Prevention is key to reducing the risk of liver cirrhosis

- More by User

Cirrhosis liver

Cirrhosis liver. Dr. Arun R Nair Assistant Professor, dept. of PM. Definition. Cirrhosis, which can be the final stage of any chronic liver disease, is a diffuse process characterized by fibrosis and conversion of normal architecture to structurally abnormal nodules.

1.52k views • 17 slides

Liver Cirrhosis

Liver Cirrhosis. K. Dionne Posey, MD, MPH Internal Medicine & Pediatrics December 9, 2004. Introduction. The two most common causes in the United States are alcoholic liver disease and hepatitis C, which together account for almost one-half of those undergoing transplantation . Introduction.

3.84k views • 60 slides

Liver Cirrhosis. Lamya Alnaim, PharmD. Background. Cirrhosis → the end stage of any chronic liver disease. Hepatitis C and alcohol are the main causes Two major syndromes result Portal hypertension Hepatic insufficiency.

2.44k views • 87 slides

LIVER CIRRHOSIS – AYURVEDIC TREATMENT

LIVER CIRRHOSIS – AYURVEDIC TREATMENT. Dr. Vikram Chauhan is One of the most Promising Ayurvedic doctors in the world and a senior consultant physician from India. He has 12 years of international exposure & treated patients of all ages and all races and

1.09k views • 25 slides

LIVER CIRRHOSIS – AYURVEDIC TREATMENT . Dr. Vikram Chauhan is One of the most Promising Ayurvedic doctors in the world and a senior consultant physician from India. He has 12 years of international exposure & treated patients of all ages and all races and

1.32k views • 25 slides

Liver Cirrhosis . S. Diana Garcia . What is Liver Cirrhosis?. Cirrhosis (pronounced sih-ROW-sis) is a consequence of chronic liver disease characterized by replacement of liver tissue by fibrosis, scar tissue, and regenerative nodules leading to loss of liver function. .

1.37k views • 11 slides

Liver Cirrhosis. S. Diana Garcia. What is Liver Cirrhosis?. Cirrhosis (pronounced sih-ROW-sis) is a consequence of chronic liver disease characterized by replacement of liver tissue by fibrosis, scar tissue, and regenerative nodules leading to loss of liver function.

924 views • 11 slides

LIVER CIRRHOSIS

LIVER CIRRHOSIS. DEFINITION : pathological condition with the development of fibrosis to the point that there is architectural distorsion with formation of regenerative nodules. CAUSES : Alcoholism Chronic viral hepatitis (Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C) Autoimmune hepatitis

1.34k views • 27 slides

Liver Cirrhosis and Its Treatment

Cirrhosis is scarring of the liver that occurs as a result of chronic liver disease. Scarring causes disruptions to the flow of blood and bile through the liver and keeps the liver from working properly.

649 views • 4 slides

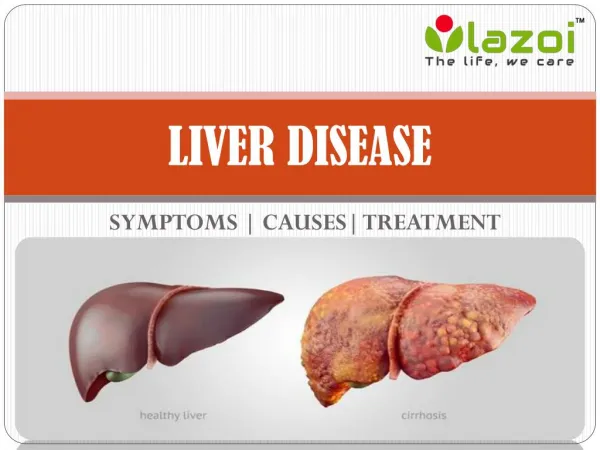

Liver Disease: Symptoms, causes, treatment, prevention and more

The liver is the largest internal organ in the body located under your rib cage on the right side of your abdomen. It is necessary for digesting food, absorbing nutrients, and eliminating toxic substances. Other than these, liver is vital for storing nutrients and producing proteins.

705 views • 8 slides

Cirrhosis of Liver: Causes and Symptoms

Highest Success Rate of Liver Transplants in India! With 17 years of experience, Dr. Vivek Vij has a track record of 95% patients and 100% donor success rate.

81 views • 1 slides

Symptoms of Male Menopause- Causes and Treatment Options

Women aren’t the only ones that can experience menopause symptoms. Men can suffer from age-related hormonal upheaval as well. Symptoms and treatment options for male menopause are the subject of this article.

108 views • 8 slides

Tinnitus – Symptoms, Causes and Treatment Options

The sensation of noise or resonant in the ears is known as Tinnitus.At the Audiology clinic all the treatments are performed by the Doctor of Audiology, Dr. Deepak Kumar. Firstly, we take a complete diagnostic audiology test of the patients and on the basis of their report, suitable hearing aids recommend to the patients.

56 views • 3 slides

Acid Reflux - Symptoms, Causes and Treatment Options

1.tAcid Reflux - Symptoms, Causes and Treatment Options 2.tAcid Reflux - Acid reflux is a fairly common disease, and more than 10 million cases are reported each year in India. It is technically known as GERD or u2018gastroesophageal reflux diseaseu2019. Acid reflux results in the backing up of stomach acids and bile into the food pipe in a reverse upward direction. An abnormal functioning of the LES (lower oesophageal sphincter), which connects the food pipe with the stomach results in acid reflux disease. It causes a burning pain in the chest, and irritation in the lining of the oesophagus (food pipe). 3.tAs it is a common disease, diagnosing acidic refluxes do not require a medical professional at all times. One can discern the presence of refluxes, based on symptoms experienced by oneself. Also laboratory testing is generally not required to diagnose acid refluxes. Let us study the symptoms, causes and various options for treatment of acid reflux in detail. 10.tIf you are struggling with Acid Reflux or GERD, take an appointment with GERD Specialist - Dr. Chirag Thakkar at Adroit Centre for Digestive and Obesity Surgery. 11.t Consult us for GERD Treatment - For Appointment Call - 079-29703438 Or Visit:- www.drchiragthakkar.com

125 views • 11 slides

Liver Transplant Symptoms and Causes

A liver transplant is a process by which failing liver is surgically replaced with the normal and healthy liver. For liver failures, only cure is to go for liver transplant. When an originally healthy live suffers major injury, acute liver failure occurs.

38 views • 2 slides

Tonsillitis – Symptoms, Causes & Treatment Options

Tonsils are the two lymph nodes located on each side of the back of your throat. They function as a defense mechanism and help prevent your body from getting an infection. When tonsils become infected, the condition is called tonsillitis. View this presentation to know more.

130 views • 6 slides

Liver Cirrhosis - Symptoms, Prevention, Diagnosis Tests

Liver Cirrhosis is the last stage of scarring (Fibrosis) of the liver that involves loss of liver cells. The main cause of cirrhosis are alcohol, hepatitis, and other liver diseases. Know about the symptoms, causes, prevention and diagnosis tests for liver cirrhosis.

144 views • 10 slides

1.19k views • 87 slides

Liver CIRRHOSIS

Liver CIRRHOSIS. Doç.Dr .Atakan Yeşil Yeditepe Unıversıty Department of Gastroenterology. Consequence of chronic liver disease characterized by replacement of liver tissue by fibrosis, scar tissue and regenerative nodules leading to progressive loss of liver function.

1.09k views • 73 slides

Liver Cirrhosis. K. Dionne Posey, MD, MPH Internal Medicine & Pediatrics December 9, 2004. Introduction. The two most common causes in the United States are alcoholic liver disease and hepatitis C, which together account for almost one-half of those undergoing transplantation. Introduction.

875 views • 60 slides

Neurological Problems: Causes, Symptoms & Treatment Options

The symptoms may seem like that of the other health conditions, so it is essential to consult the best neurologist in Dubai and get a diagnosis before the condition gets worse. Coming to the available treatment options, the most popular treatments among the masses. Read more info: https://bit.ly/2FJf68g

89 views • 8 slides

Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Causes Symptoms and Treatment Options

Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis is the most common type of Scoliosis suffered by children between the ages of 10 and 18. As the onset of the curve coincides with the growth spurt of the children, the possibility of curve progression increases, severely impacting the body anatomy over time.

120 views • 9 slides

Warning: The NCBI web site requires JavaScript to function. more...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Hepatic cirrhosis.

Bashar Sharma ; Savio John .

Affiliations

Last Update: October 31, 2022 .

- Continuing Education Activity

Cirrhosis is characterized by fibrosis and nodule formation of the liver secondary to chronic injury, leading to alteration of the normal lobular organization of the liver. Various insults can injure the liver, including viral infections, toxins, hereditary conditions, or autoimmune processes. With each injury, the liver initially forms scar tissue (fibrosis) without losing its function. After a chronic injury, most of the liver tissue becomes fibrotic, leading to loss of function and the development of cirrhosis. This activity reviews the causes, evaluation, and management of hepatic cirrhosis and highlights the interprofessional team's role in managing patients with this condition.

- Identify the pathophysiology of cirrhosis.

- Assess the etiology of cirrhosis.

- Evaluate the presentation of a patient with cirrhosis.

- Communicate the importance of improving care coordination amongst interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for cirrhotic patients.

- Introduction

Cirrhosis is characterized by fibrosis and nodule formation of the liver, secondary to a chronic injury, which leads to alteration of the normal lobular organization of the liver. Various insults can injure the liver, including viral infections, toxins, hereditary conditions, or autoimmune processes. The liver initially forms scar tissue (fibrosis) with each injury without losing its function. After a long-standing injury, most of the liver tissue gets fibrosed, leading to loss of function and the development of cirrhosis. See image. Cirrhosis, Liver.

Chronic liver diseases usually progress to cirrhosis. In the developed world, the most common causes of cirrhosis are hepatitis C virus (HCV), alcoholic liver disease, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). In contrast, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and HCV are the most common causes in the developing world. [1] Other causes of cirrhosis include autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, hemochromatosis, Wilson disease, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, Budd-Chiari syndrome, drug-induced liver cirrhosis, and chronic right-sided heart failure. Cryptogenic cirrhosis is defined as cirrhosis of unclear etiology.

- Epidemiology

The worldwide prevalence of cirrhosis is unknown; however, it has been estimated to be between 0.15% and 0.27% in the United States. [2] [3]

- Pathophysiology

Multiple cells play a role in liver cirrhosis, including hepatocytes and sinusoidal lining cells such as hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), sinusoidal endothelial cells (SECs), and Kupffer cells (KCs). HSCs form a part of the wall of the liver sinusoids, and their function is to store vitamin A. When these cells are exposed to inflammatory cytokines, they get activated, transform into myofibroblasts, and start depositing collagen, which results in fibrosis. SECs form the endothelial lining and are characterized by the fenestrations they make in the wall that allow the exchange of fluid and nutrients between the sinusoids and the hepatocytes. [4] Defenestration of the sinusoidal wall can happen secondary to chronic alcohol use and promote perisinusoidal fibrosis. [5] KCs are satellite macrophages that line the wall of the sinusoids as well. Studies from animal models have shown that they play a role in liver fibrosis by releasing harmful mediators when exposed to injurious agents and acting as antigen-presenting cells for viruses. [6] Hepatocytes are also involved in cirrhosis's pathogenesis, as damaged hepatocytes release reactive oxygen species and inflammatory mediators that can promote activating HSCs and liver fibrosis. [7]

The major cause of morbidity and mortality in cirrhotic patients is the development of portal hypertension and hyperdynamic circulation. Portal hypertension develops secondary to fibrosis and vasoregulatory changes intrahepatically and systematically, leading to collateral circulation formation and hyperdynamic circulation. [8] Intrahepatically, SECs synthesize nitric oxide (NO) and endothelin-1 (ET-1), which act on HSCs, causing relaxation or contraction of the sinusoids, respectively, and controlling sinusoidal blood flow. In patients with cirrhosis, there is an increase in ET-1 production and the sensitivity of its receptors with a decrease in NO production. This leads to increased intrahepatic vasoconstriction and resistance, initiating portal hypertension. Vascular remodeling mediated by the contractile effects of HSCs in the sinusoids augments the increase in vascular resistance. To compensate for this increase in intrahepatic pressure, collateral circulation is formed. [8] In systemic and splanchnic circulation, the opposite effect happens, with an increase in NO production, leading to systemic and splanchnic vasodilation and decreased systemic vascular resistance. This activates the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, leading to sodium and water retention and hyperdynamic circulation. Thus, in cirrhosis with portal hypertension, there is a depletion of vasodilators (predominantly NO) intrahepatic-ally but a renin-excess of NO extrahepatically in the splanchnic and systemic circulation, leading to sinusoidal vasoconstriction and splanchnic (systemic) vasodilation. The collaterals also contribute to the hyperdynamic circulation by increasing the venous return to the heart. [8] [9]

- Histopathology

Cirrhosis is classified based on morphology or etiology.

- Viral - hepatitis B, C, and D

- Toxins - alcohol, drugs

- Autoimmune - autoimmune hepatitis

- Cholestatic - primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Vascular - Budd-Chiari syndrome, sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, cardiac cirrhosis

- History and Physical

Patients with cirrhosis can be asymptomatic or symptomatic, depending on whether their cirrhosis is clinically compensated or decompensated. In compensated cirrhosis, patients are usually asymptomatic, and their disease is detected incidentally by labs, physical exams, or imaging. One of the common findings is mild to moderate elevation in aminotransferases or gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase with possible enlarged liver or spleen on the exam. On the other hand, patients with decompensated cirrhosis usually present with a wide range of signs and symptoms arising from a combination of liver dysfunction and portal hypertension. The diagnosis of ascites, jaundice, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, or hepatocellular carcinoma in a patient with cirrhosis signifies the transition from a compensated to a decompensated phase of cirrhosis. Other cirrhosis complications include spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and hepatorenal syndrome, which occur in patients who have ascites.

Multiple Organs Affected

Gastrointestinal

Portal hypertension can cause ascites, hepatosplenomegaly, and prominence of the periumbilical abdominal veins, resulting in caput medusa. Esophageal varices are another complication of cirrhosis secondary to increased blood flow in the collateral circulation, with a mortality rate of at least 20% at 6 weeks after a bleeding episode. [10] Patients with alcoholic cirrhosis are at increased risk of small bowel bacterial overgrowth and chronic pancreatitis, and patients with chronic liver disease have a higher rate of gallstone formation. [11] [12]

Hematologic

Anemia can occur due to folate deficiency, hemolytic anemia (spur cell anemia in severe alcoholic liver disease), and hypersplenism. There can be pancytopenia due to hypersplenism in portal hypertension, impaired coagulation, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and hemosiderosis in cirrhosis patients due to different causes.

Patients with cirrhosis are prone to develop hepatorenal syndrome secondary to systemic hypotension and renal vasoconstriction, causing the underfilling phenomenon. Splanchnic vasodilation in cirrhosis leads to decreased effective blood flow to the kidneys, activating the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, leading to sodium and water retention and renal vascular constriction. [13] However, this effect is not enough to overcome the systemic vasodilation caused by cirrhosis, leading to renal hypoperfusion and worsened by renal vasoconstriction with the endpoint of renal failure. [14]

Manifestations of cirrhosis include hepatopulmonary syndrome, portopulmonary hypertension, hepatic hydrothorax, decreased oxygen saturation, ventilation-perfusion mismatch, reduced pulmonary diffusion capacity, and hyperventilation.

Spider nevi, central arterioles surrounded by multiple smaller vessels resembling a spider, are seen in cirrhosis patients secondary to hyperestrogenemia. Liver dysfunction leads to a sex hormone imbalance, causing an increased estrogen-to-free testosterone ratio and the formation of spider nevi. [15] Palmar erythema is another skin finding that is seen in cirrhosis and is also secondary to hyperestrogenemia. Jaundice is a yellowish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes seen when the serum bilirubin is greater than 3 mg/dL and in decompensated cirrhosis.

Patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis can develop hypogonadism and gynecomastia. The pathophysiology is multifactorial, mainly due to the hypersensitivity of estrogen and androgen receptors seen in cirrhotic patients. Hypothalamic pituitary dysfunction has also been implicated in the development of these conditions. [16] Hypogonadism can lead to decreased libido and impotence in males with loss of secondary sexual characteristics and feminization. Women can develop amenorrhea and irregular menstrual bleeding, as well as infertility.

Nail Changes

Clubbing, hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, and the Dupuytren contracture are seen. Other nail changes include azure lunules (Wilson disease), Terry nails, and Muehrcke nails.

Fetor hepaticus (sweet, musty breath smell due to high levels of dimethyl sulfide and ketones in the blood) and asterixis (flapping tremor when the arms are extended and the hands are dorsiflexed) are both features of hepatic encephalopathy that can be seen in cirrhosis. [17] Cirrhosis can lead to hyperdynamic circulation, reduced lean muscle mass, muscle cramps, and umbilical herniation. Physical examination in patients with cirrhosis may reveal stigmata of chronic liver disease (spider telangiectasias, palmar erythema, Dupuytren contractures, gynecomastia, testicular atrophy), signs of portal hypertension (ascites, splenomegaly, caput medusae, Cruveilhier-Baumgarten murmur- epigastric venous hum), signs of hepatic encephalopathy (confusion, asterixis, and fetor hepaticus), and other features such as jaundice, bilateral parotid enlargement, and scant chest/axillary hair.

Lab Findings

Aminotransferases are usually mildly to moderately elevated, with aspartate aminotransferase (AST) greater than alanine aminotransferase (ALT); however, normal levels do not exclude cirrhosis. [18] In most forms of chronic hepatitis (except alcoholic hepatitis), the AST/ALT ratio is less than 1. As chronic hepatitis progresses to cirrhosis, there is a reversal of this AST/ALT ratio. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 5'- nucleotidase, and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) are elevated in cholestatic disorders. Prothrombin time (PT) is elevated due to coagulation factor defects and bilirubin, while albumin is low as the liver synthesizes it, and its functional capacity decreases. Thus, serum albumin and PT are true indicators of synthetic hepatic function. Normochromic anemia is seen; however, macrocytic anemia can be seen in alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Leukopenia and thrombocytopenia are also seen secondary to sequestration by the enlarged spleen and alcohol suppression effect on the bone marrow. [19] Immunoglobulins, especially the gamma fraction, are usually elevated due to impaired clearance by the liver. [20]

Specific Labs to Investigate Newly Diagnosed Cirrhosis

Serology and PCR techniques for viral hepatitis and autoimmune antibodies (anti-nuclear antibodies [ANA], anti-smooth muscle antibodies (ASMA), anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibodies type 1 (ALKM-1) and serum IgG immunoglobulins) for autoimmune hepatitis and anti-mitochondrial antibody for primary biliary cholangitis may be ordered. Ferritin and transferrin saturation for hemochromatosis, ceruloplasmin, and urinary copper for Wilson disease, Alpha 1-antitrypsin level, and protease inhibitor phenotype for alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency, and serum alpha-fetoprotein for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are other useful tests.

Imaging and Liver Biopsy