Why we need reparations for Black Americans

- Download the full report

Subscribe to How We Rise

Rashawn ray and rashawn ray senior fellow - governance studies andre m. perry andre m. perry senior fellow - brookings metro , director - center for community uplift.

April 15, 2020

- 14 min read

Central to the idea of the American Dream lies an assumption that we all have an equal opportunity to generate the kind of wealth that brings meaning to the words “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” boldly penned in the Declaration of Independence. The American Dream portends that with hard work, a person can own a home, start a business, and grow a nest egg for generations to draw upon. This belief, however, has been defied repeatedly by the United States government’s own decrees that denied wealth-building opportunities to Black Americans.

Today, the average white family has roughly 10 times the amount of wealth as the average Black family. White college graduates have over seven times more wealth than Black college graduates. Making the American Dream an equitable reality demands the same U.S. government that denied wealth to Blacks restore that deferred wealth through reparations to their descendants in the form of individual cash payments in the amount that will close the Black-white racial wealth divide. Additionally, reparations should come in the form of wealth-building opportunities that address racial disparities in education, housing, and business ownership.

In 1860, over $3 billion was the value assigned to the physical bodies of enslaved Black Americans to be used as free labor and production. This was more money than was invested in factories and railroads combined. In 1861, the value placed on cotton produced by enslaved Blacks was $250 million. Slavery enriched white slave owners and their descendants, and it fueled the country’s economy while suppressing wealth building for the enslaved. The United States has yet to compensate descendants of enslaved Black Americans for their labor. Nor has the federal government atoned for the lost equity from anti-Black housing, transportation, and business policy. Slavery, Jim Crow segregation, anti-Black practices like redlining, and other discriminatory public policies in criminal justice and education have robbed Black Americans of the opportunities to build wealth (defined as assets minus debt) afforded to their white peers.

Bootstrapping isn’t going to erase racial wealth divides. As economists William “Sandy” Darity and Darrick Hamilton point out in their 2018 report , What We Get Wrong About Closing the Wealth Gap , “Blacks cannot close the racial wealth gap by changing their individual behavior –i.e. by assuming more ‘personal responsibility’ or acquiring the portfolio management insights associated with ‘[financial] literacy.’” In fact, white high school dropouts have more wealth than Black college graduates . Moreover, the racial wealth gap did not result from a lack of labor. Rather, it came from a lack of financial capital.

Not only do racial wealth disparities reveal fallacies in the American Dream, the financial and social consequences are significant and wide-ranging. Wealth is positively correlated with better health, educational, and economic outcomes. Furthermore, assets from homes, stocks, bonds, and retirement savings provide a financial safety net for the inevitable shocks to the economy and personal finances that happen throughout a person’s lifespan.

Recessions impact everyone, but wealth is distributed quite unevenly in the U.S. The woeful inadequacy of a government-sponsored safety net was made apparent in the wake of economic disasters like the 2008 housing crisis and natural ones like Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Those who can draw upon the equity in a home, savings, and securities are able to recover faster after economic downturns than those without wealth. The lack of a social safety net and the racial wealth divide are currently on display amid the COVID-19 crisis. Disparities in access to health care along with inequities in economic policies combine to make Black people more vulnerable to negative consequences than white individuals.

Below, we provide a history of reparations in the United States, missed opportunities to redress the racial wealth gap, and specific details of a viable reparations package for Black Americans.

History of reparations in the United States

Reparations—a system of redress for egregious injustices—are not foreign to the United States. Native Americans have received land and billions of dollars for various benefits and programs for being forcibly exiled from their native lands. For Japanese Americans, $1.5 billion was paid to those who were interned during World War II . Additionally, the United States, via the Marshall Plan , helped to ensure that Jews received reparations for the Holocaust, including making various investments over time. In 1952, West Germany agreed to pay 3.45 billion Deutsche Marks to Holocaust survivors.

Black Americans are the only group that has not received reparations for state-sanctioned racial discrimination, while slavery afforded some white families the ability to accrue tremendous wealth. And, we must note that American slavery was particularly brutal. About 15 percent of the enslaved shipped from Western Africa died during transport. The enslaved were regularly beaten and lynched for frivolous infractions. Slavery also disrupted families as one in three marriages were split up and one in five children were separated from their parents. The case for reparations can be made on economic, social, and moral grounds. The United States had multiple opportunities to atone for slavery—each a missed chance to make the American Dream a reality—but has yet to undertake significant action.

Missed policy opportunities to atone for slavery with reparations

40 Acres and a Mule

The first major opportunity that the United States had and where it should have atoned for slavery was right after the Civil War. Union leaders including General William Sherman concluded that each Black family should receive 40 acres. Sherman signed Field Order 15 and allocated 400,000 acres of confiscated Confederate land to Black families. Additionally, some families were to receive mules left over from the war, hence 40 acres and a mule .

Yet, after President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, President Andrew Johnson reversed Field Order 15 and returned land back to former slave owners. Instead of giving Blacks the means to support themselves, the federal government empowered former enslavers. For example, in Washington D.C., slave owners were actually paid reparations for lost property —the formally enslaved. This practice was also common in nearby states. Many Black Americans with limited work options returned as sharecroppers to till the same land for the very slave owners to whom they were once enslaved. Slave owners not only made money off the chattel enslavement of Black Americans, but they then made money multiple times over off the land that the formerly enslaved had no choice but to work.

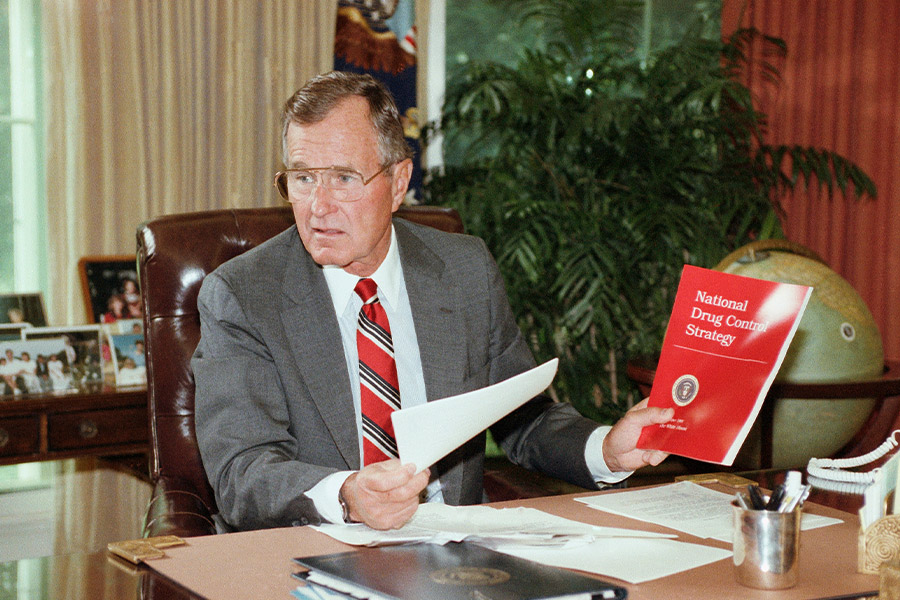

The New Deal

There’s never a bad time to do what’s morally right, but the United States has had prime opportunities to atone for slavery. In the 1930s, the United States was reeling from the 1929 stock market crash and was firmly engulfed in the Great Depression. The Franklin Roosevelt administration implemented a series of policies as part of his New Deal legislation, estimated to cost roughly $50 billion then, to catapult the country out of depression. Current estimates price the New Deal at about $50 trillion.

Two particular policies of the New Deal fell short in redressing American’s racial wrongs—the G.I. Bill and Social Security. Though white and Black Americans fought in WWII, Black veterans could not redeem their post-war benefits like their white peers. While the G.I. Bill was mandated federally, it was implemented locally. The presence of racial housing covenants and redlining among local municipalities prohibited Blacks from utilizing federal benefits. White soldiers were afforded the opportunity to build wealth by sending themselves and their children to college and by obtaining housing and small business grants.

Regarding Social Security, two key professions that would have improved equity in America were excluded from the legislation—domestic and farm workers. These omissions effectively excluded 60 percent of Blacks across the U.S. and 75 percent in southern states who worked in these occupations. Roosevelt bargained these exclusionary provisions in the legislation on the backs of Black veterans and workers in order to propel mostly white America out of the Great Depression.

There are other policies and practices that contributed to racial wealth gap. Government-sanctioned discrimination related to the 1862 Homestead Act, redlining, restrictive covenants, and convict leasing blocked Blacks from the ability to gain wealth at similar rates as whites. Separate from slavery, damages should be awarded to Black people who were harmed by these policies and practices.

Reparations for slavery and anti-Black policies

We know the monetary value that was placed on enslaved Blacks and the productivity of their labor, as well as the amount of the racial wealth gap. We’ve seen other groups receive restitutions while the federal government pulled back reparations for Black Americans. Accordingly, if we want to close the racial wealth gap and live up to our moral creed to protect “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” a federal reparations package for Black Americans is in order. This package should include individual and collective public benefits that simultaneously builds wealth and eliminates debt among Black citizens. We assert that it should be similar to the Harriet Tubman Community Investment Act, which was recently heard before the Maryland General Assembly where Ray testified on its behalf . The Harriet Tubman Community Investment Act aims to atone for slavery and its legacy by addressing education, homeownership, and business ownership barriers.

Individual payments for descendants of enslaved Black Americans

The U.S. government owes lost wages as well as damages to the people it helped enslave. In addition to the lost wages, the accumulative amount of restitution for individuals should eliminate the racial wealth gap that currently exists. According to the Federal Reserve’s most recent numbers in 2016, based on the Survey of Consumer Finances, white families had the highest median family wealth at $171,000, compared to Black and Hispanic families, which had $17,600 and $20,700, respectively.

College tuition to 4-year or 2-year colleges and universities for descendants of enslaved Black Americans

People should be able to use the tuition remission to obtain a bachelor’s degree or an associate’s/vocational or technical degree. Tuition should be available for public or private universities. Considering the racial gap in the ability to obtain degrees at private schools, this part of the package will further help to reduce racial disparities by affording more social network access and opportunity structures.

Student loan forgiveness for descendants of enslaved Black Americans

Student loan debt continues to be a significant barrier to wealth creation for Black college graduates. Among 25-55 year olds, about 40 percent of Blacks compared to 30 percent of whites have student loan debt . Blacks also have nearly $45,000 of student loan debt compared to about $30,000 for whites. Recent research finds that Blacks are more likely to be allocated unsubsidized loans. Furthermore, graduates of Historically Black Colleges and Universities, compared to Predominately White Institutions, are more likely to receive subprime loans with higher interest rates.

Universities including Georgetown and Princeton Theological Seminary, which is the second-oldest seminary in the country, are aiming to atone for the fact that the sale of slaves helped to fortify their university endowments and establish them as elite institutions of higher education on a global scale. Descendants of the slaves sold by Georgetown and Princeton Theological Seminary are now entitled to full rights and benefits bestowed by those universities to obtain degrees across the higher education pipeline. The Virginia state legislature voted for some of its state universities to atone for slavery with reparations. Other universities, along with state legislatures and the federal government, should follow suit.

Down payment grants and housing revitalization grants for descendants of enslaved Black Americans

Down payment grants will provide Black Americans with some initial equity in their homes relative to mortgage insurance loans. Housing revitalization grants will help Black Americans to refurbish existing homes in neighborhoods that have been neglected due to a lack of government and corporate investments in predominately Black communities. Given recent settlements for predatory lending , low and fixed interest rates as well as property tax caps in areas in which housing prices are significantly devalued should be part of the package. After accounting for factors such as housing quality, neighborhood quality, education, and crime, owner-occupied homes in Black neighborhoods are undervalued by $48,000 per home on average, amounting to a whopping $156 billion that homeowners would have received if their homes were priced at market rates, according to Brookings research .

As gentrification occurs, Blacks are typically priced out of neighborhoods they helped to maintain, while the historical and current remnants of redlining and restrictive covenants inhibited investments. Some Black Americans are being forced from their family home of decades because of tax increases as neighborhoods are gentrified. This is an important point because some 2020 Democratic presidential candidates aimed to redress the racial wealth gap by focusing on historically redlined districts. Perry’s research shows that these policies fall short of capturing a large segment of Black Americans.

Business grants for business starting up, business expansion to hire more employees, or purchasing property for descendants of enslaved Black Americans

Black-owned businesses are more likely to be located in predominately Black neighborhoods that need the infrastructure and businesses. However, Black business owners are still less likely to obtain capital from banks to make their businesses successful.

This reparations package for Black Americans is about restoring the wealth that has been extracted from Black people and communities. Still, reparations are all for naught without enforcement of anti-discrimination policies that remove barriers to economic mobility and wealth building. The architecture of the economy must change in order to create an equitable society. The racial wealth gap was created by racist policies. Federal intervention is needed to remove the racism that undergirds those polices. In some respects, the question of who should receive reparations is more controversial than what or how much people should be awarded.

Who should receive reparations?

One key question after deciding what a reparations package should include is who should qualify. In short, a Black person who can trace their heritage to people enslaved in U.S. states and territories should be eligible for financial compensation for slavery. Meanwhile, Black people who can show how they were excluded from various policies after emancipation should seek separate damages. For instance, a person like Senator Cory Booker whose parents are descendants of slaves would qualify for slavery reparations whereas Senator Kamala Harris (Jamaican immigrant father and Indian immigrant mother) and President Barack Obama (Kenyan immigrant father and white mother) may seek redress for housing and/or education segregation. Sasha and Malia Obama (whose mother is Michelle Robinson Obama, a descendant of enslaved Africans) would qualify.

To determine qualification, birth records can initially be used to determine if a person was classified as Black American. Economist Sandy Darity asserts that people should show a consistent pattern of identification . Census records can then be used to determine if a person has consistently identified as Black American. Finally, DNA testing can be used as a supplement to determine lineage. This is how Senator Booker, who first introduced a reparations bill in the Senate, learned that his lineage stemmed from Sierra Leone.

For the descendants of the 12.5 million Blacks who were shipped in chains from Western Africa, “America has a genetic birth defect when it comes to the question of race,” as stated recently by U.S. Representative Hakeem Jeffries. If America is to atone for this defect, reparations for Black Americans is part of the healing and reconciliation process.

With April 4 marking the fifty-second year since Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, we think it is appropriate to end with an oft-forgotten quote from Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream Speech” that he gave in 1963 in Washington, D.C. This statement is still one of the unfulfilled aspects of this policy-related speech:

We have come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. … It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.” But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt.

Given the lingering legacy of slavery on the racial wealth gap, the monetary value we know that was placed on enslaved Blacks, the fact that other groups have received reparations, and the fact that Blacks were originally awarded reparations only to have them rescinded provide overwhelming evidence that it is time to pay reparations to the descendants of enslaved Blacks.

Related Content

Read Andre Perry’s new book, “Know Your Price: Valuing Black Lives and Property in America’s Black Cities”

Read Rashawn Ray’s testimony before the Maryland General Assembly on the Harriet Tubman Community Investment Act.

Watch a virtual Brookings event on economic reparations with William “Sandy” Darity.

Listen to Rashawn Ray and Andre Perry discuss their proposal on an episode of The Brookings Cafeteria podcast.

William “Sandy” Darity, Kirsten Mullen

June 15, 2020

Vanessa Williamson

December 9, 2020

Rashawn Ray

April 7, 2020

Related Books

Andrew Yeo, Isaac B. Kardon

August 20, 2024

Mara Karlin

January 19, 2018

Tom Wheeler

July 1, 2024

Brookings Metro Governance Studies

U.S. States and Territories

Race, Prosperity, and Inclusion Initiative

Keesha Middlemass

June 26, 2024

Nicol Turner Lee

August 6, 2024

Online Only

1:00 pm - 2:00 pm EDT

The Case for Reparations

Two hundred fifty years of slavery. Ninety years of Jim Crow. Sixty years of separate but equal. Thirty-five years of racist housing policy. Until we reckon with our compounding moral debts, America will never be whole.

Editor’s note: On February 1, 2023, the College Board announced its finalized curriculum for an AP African American Studies course. It has removed work—present in the pilot program—by writers such as bell hooks, Kimberlé Crenshaw, and Ta-Nehisi Coates, the author of this article.

We’ve gathered dozens of the most important pieces from our archives on race and racism in America. Find the collection here .

And if thy brother, a Hebrew man, or a Hebrew woman, be sold unto thee, and serve thee six years; then in the seventh year thou shalt let him go free from thee. And when thou sendest him out free from thee, thou shalt not let him go away empty: thou shalt furnish him liberally out of thy flock, and out of thy floor, and out of thy winepress: of that wherewith t he LORD thy God hath blessed thee thou shalt give unto him. And thou shalt remember that thou wast a bondman in the land of Egypt, and the LORD thy God redeemed thee: therefore I command thee this thing today.

— Deuteronomy 15: 12–15

Besides the crime which consists in violating the law, and varying from the right rule of reason, whereby a man so far becomes degenerate, and declares himself to quit the principles of human nature, and to be a noxious creature, there is commonly injury done to some person or other, and some other man receives damage by his transgression: in which case he who hath received any damage, has, besides the right of punishment common to him with other men, a particular right to seek reparation.

— John Locke, “Second Treatise”

By our unpaid labor and suffering, we have earned the right to the soil, many times over and over, and now we are determined to have it.

— Anonymous, 1861

I. “So That’s Just One Of My Losses”

C lyde Ross was born in 1923, the seventh of 13 children, near Clarksdale, Mississippi, the home of the blues. Ross’s parents owned and farmed a 40-acre tract of land, flush with cows, hogs, and mules. Ross’s mother would drive to Clarksdale to do her shopping in a horse and buggy, in which she invested all the pride one might place in a Cadillac. The family owned another horse, with a red coat, which they gave to Clyde. The Ross family wanted for little, save that which all black families in the Deep South then desperately desired—the protection of the law.

In the 1920s, Jim Crow Mississippi was, in all facets of society, a kleptocracy. The majority of the people in the state were perpetually robbed of the vote—a hijacking engineered through the trickery of the poll tax and the muscle of the lynch mob. Between 1882 and 1968, more black people were lynched in Mississippi than in any other state. “You and I know what’s the best way to keep the nigger from voting,” blustered Theodore Bilbo, a Mississippi senator and a proud Klansman. “You do it the night before the election.”

The state’s regime partnered robbery of the franchise with robbery of the purse. Many of Mississippi’s black farmers lived in debt peonage, under the sway of cotton kings who were at once their landlords, their employers, and their primary merchants. Tools and necessities were advanced against the return on the crop, which was determined by the employer. When farmers were deemed to be in debt—and they often were—the negative balance was then carried over to the next season. A man or woman who protested this arrangement did so at the risk of grave injury or death. Refusing to work meant arrest under vagrancy laws and forced labor under the state’s penal system.

Well into the 20th century, black people spoke of their flight from Mississippi in much the same manner as their runagate ancestors had. In her 2010 book, The Warmth of Other Suns , Isabel Wilkerson tells the story of Eddie Earvin, a spinach picker who fled Mississippi in 1963, after being made to work at gunpoint. “You didn’t talk about it or tell nobody,” Earvin said. “You had to sneak away.”

When Clyde Ross was still a child, Mississippi authorities claimed his father owed $3,000 in back taxes. The elder Ross could not read. He did not have a lawyer. He did not know anyone at the local courthouse. He could not expect the police to be impartial. Effectively, the Ross family had no way to contest the claim and no protection under the law. The authorities seized the land. They seized the buggy. They took the cows, hogs, and mules. And so for the upkeep of separate but equal, the entire Ross family was reduced to sharecropping.

This was hardly unusual. In 2001, the Associated Press published a three-part investigation into the theft of black-owned land stretching back to the antebellum period. The series documented some 406 victims and 24,000 acres of land valued at tens of millions of dollars. The land was taken through means ranging from legal chicanery to terrorism. “Some of the land taken from black families has become a country club in Virginia,” the AP reported, as well as “oil fields in Mississippi” and “a baseball spring training facility in Florida.”

Clyde Ross was a smart child. His teacher thought he should attend a more challenging school. There was very little support for educating black people in Mississippi. But Julius Rosenwald, a part owner of Sears, Roebuck, had begun an ambitious effort to build schools for black children throughout the South. Ross’s teacher believed he should attend the local Rosenwald school. It was too far for Ross to walk and get back in time to work in the fields. Local white children had a school bus. Clyde Ross did not, and thus lost the chance to better his education.

Then, when Ross was 10 years old, a group of white men demanded his only childhood possession—the horse with the red coat. “You can’t have this horse. We want it,” one of the white men said. They gave Ross’s father $17.

“I did everything for that horse,” Ross told me. “Everything. And they took him. Put him on the racetrack. I never did know what happened to him after that, but I know they didn’t bring him back. So that’s just one of my losses.”

The losses mounted. As sharecroppers, the Ross family saw their wages treated as the landlord’s slush fund. Landowners were supposed to split the profits from the cotton fields with sharecroppers. But bales would often disappear during the count, or the split might be altered on a whim. If cotton was selling for 50 cents a pound, the Ross family might get 15 cents, or only five. One year Ross’s mother promised to buy him a $7 suit for a summer program at their church. She ordered the suit by mail. But that year Ross’s family was paid only five cents a pound for cotton. The mailman arrived with the suit. The Rosses could not pay. The suit was sent back. Clyde Ross did not go to the church program.

It was in these early years that Ross began to understand himself as an American—he did not live under the blind decree of justice, but under the heel of a regime that elevated armed robbery to a governing principle. He thought about fighting. “Just be quiet,” his father told him. “Because they’ll come and kill us all.”

Clyde Ross grew. He was drafted into the Army. The draft officials offered him an exemption if he stayed home and worked. He preferred to take his chances with war. He was stationed in California. He found that he could go into stores without being bothered. He could walk the streets without being harassed. He could go into a restaurant and receive service.

Ross was shipped off to Guam. He fought in World War II to save the world from tyranny. But when he returned to Clarksdale, he found that tyranny had followed him home. This was 1947, eight years before Mississippi lynched Emmett Till and tossed his broken body into the Tallahatchie River. The Great Migration, a mass exodus of 6 million African Americans that spanned most of the 20th century, was now in its second wave. The black pilgrims did not journey north simply seeking better wages and work, or bright lights and big adventures. They were fleeing the acquisitive warlords of the South. They were seeking the protection of the law.

Clyde Ross was among them. He came to Chicago in 1947 and took a job as a taster at Campbell’s Soup. He made a stable wage. He married. He had children. His paycheck was his own. No Klansmen stripped him of the vote. When he walked down the street, he did not have to move because a white man was walking past. He did not have to take off his hat or avert his gaze. His journey from peonage to full citizenship seemed near-complete. Only one item was missing—a home, that final badge of entry into the sacred order of the American middle class of the Eisenhower years.

In 1961, Ross and his wife bought a house in North Lawndale, a bustling community on Chicago’s West Side. North Lawndale had long been a predominantly Jewish neighborhood, but a handful of middle-class African Americans had lived there starting in the ’40s. The community was anchored by the sprawling Sears, Roebuck headquarters. North Lawndale’s Jewish People’s Institute actively encouraged blacks to move into the neighborhood, seeking to make it a “pilot community for interracial living.” In the battle for integration then being fought around the country, North Lawndale seemed to offer promising terrain. But out in the tall grass, highwaymen, nefarious as any Clarksdale kleptocrat, were lying in wait.

Three months after Clyde Ross moved into his house, the boiler blew out. This would normally be a homeowner’s responsibility, but in fact, Ross was not really a homeowner. His payments were made to the seller, not the bank. And Ross had not signed a normal mortgage. He’d bought “on contract”: a predatory agreement that combined all the responsibilities of homeownership with all the disadvantages of renting—while offering the benefits of neither. Ross had bought his house for $27,500. The seller, not the previous homeowner but a new kind of middleman, had bought it for only $12,000 six months before selling it to Ross. In a contract sale, the seller kept the deed until the contract was paid in full—and, unlike with a normal mortgage, Ross would acquire no equity in the meantime. If he missed a single payment, he would immediately forfeit his $1,000 down payment, all his monthly payments, and the property itself.

The men who peddled contracts in North Lawndale would sell homes at inflated prices and then evict families who could not pay—taking their down payment and their monthly installments as profit. Then they’d bring in another black family, rinse, and repeat. “He loads them up with payments they can’t meet,” an office secretary told The Chicago Daily News of her boss, the speculator Lou Fushanis, in 1963. “Then he takes the property away from them. He’s sold some of the buildings three or four times.”

Ross had tried to get a legitimate mortgage in another neighborhood, but was told by a loan officer that there was no financing available. The truth was that there was no financing for people like Clyde Ross. From the 1930s through the 1960s, black people across the country were largely cut out of the legitimate home-mortgage market through means both legal and extralegal. Chicago whites employed every measure, from “restrictive covenants” to bombings, to keep their neighborhoods segregated.

Their efforts were buttressed by the federal government. In 1934, Congress created the Federal Housing Administration. The FHA insured private mortgages, causing a drop in interest rates and a decline in the size of the down payment required to buy a house. But an insured mortgage was not a possibility for Clyde Ross. The FHA had adopted a system of maps that rated neighborhoods according to their perceived stability. On the maps, green areas, rated “A,” indicated “in demand” neighborhoods that, as one appraiser put it, lacked “a single foreigner or Negro.” These neighborhoods were considered excellent prospects for insurance. Neighborhoods where black people lived were rated “D” and were usually considered ineligible for FHA backing. They were colored in red. Neither the percentage of black people living there nor their social class mattered. Black people were viewed as a contagion. Redlining went beyond FHA-backed loans and spread to the entire mortgage industry, which was already rife with racism, excluding black people from most legitimate means of obtaining a mortgage.

Explore Redlining in Chicago

“A government offering such bounty to builders and lenders could have required compliance with a nondiscrimination policy,” Charles Abrams, the urban-studies expert who helped create the New York City Housing Authority, wrote in 1955. “Instead, the FHA adopted a racial policy that could well have been culled from the Nuremberg laws.”

The devastating effects are cogently outlined by Melvin L. Oliver and Thomas M. Shapiro in their 1995 book, Black Wealth/White Wealth :

Locked out of the greatest mass-based opportunity for wealth accumulation in American history, African Americans who desired and were able to afford home ownership found themselves consigned to central-city communities where their investments were affected by the “self-fulfilling prophecies” of the FHA appraisers: cut off from sources of new investment[,] their homes and communities deteriorated and lost value in comparison to those homes and communities that FHA appraisers deemed desirable.

In Chicago and across the country, whites looking to achieve the American dream could rely on a legitimate credit system backed by the government. Blacks were herded into the sights of unscrupulous lenders who took them for money and for sport. “It was like people who like to go out and shoot lions in Africa. It was the same thrill,” a housing attorney told the historian Beryl Satter in her 2009 book, Family Properties . “The thrill of the chase and the kill.”

The kill was profitable. At the time of his death, Lou Fushanis owned more than 600 properties, many of them in North Lawndale, and his estate was estimated to be worth $3 million. He’d made much of this money by exploiting the frustrated hopes of black migrants like Clyde Ross. During this period, according to one estimate, 85 percent of all black home buyers who bought in Chicago bought on contract. “If anybody who is well established in this business in Chicago doesn’t earn $100,000 a year,” a contract seller told The Saturday Evening Post in 1962, “he is loafing.”

Contract sellers became rich. North Lawndale became a ghetto.

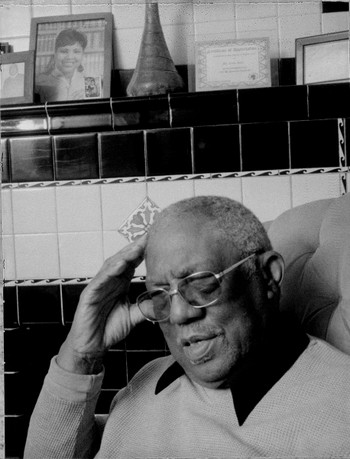

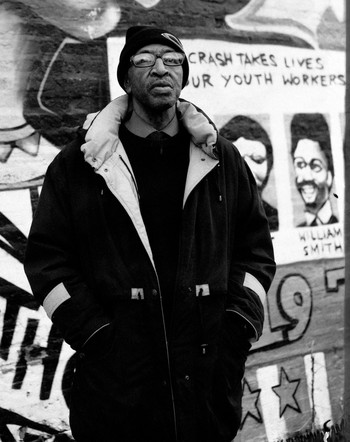

Clyde Ross still lives there. He still owns his home. He is 91, and the emblems of survival are all around him—awards for service in his community, pictures of his children in cap and gown. But when I asked him about his home in North Lawndale, I heard only anarchy.

“We were ashamed. We did not want anyone to know that we were that ignorant,” Ross told me. He was sitting at his dining-room table. His glasses were as thick as his Clarksdale drawl. “I’d come out of Mississippi where there was one mess, and come up here and got in another mess. So how dumb am I? I didn’t want anyone to know how dumb I was.

“When I found myself caught up in it, I said, ‘How? I just left this mess. I just left no laws. And no regard. And then I come here and get cheated wide open.’ I would probably want to do some harm to some people, you know, if I had been violent like some of us. I thought, ‘Man, I got caught up in this stuff. I can’t even take care of my kids.’ I didn’t have enough for my kids. You could fall through the cracks easy fighting these white people. And no law.”

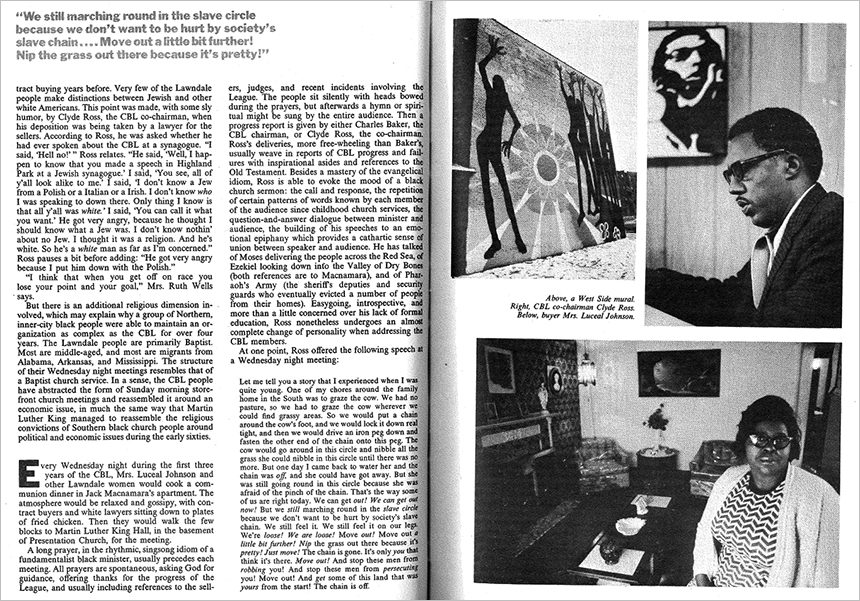

But fight Clyde Ross did. In 1968 he joined the newly formed Contract Buyers League —a collection of black homeowners on Chicago’s South and West Sides, all of whom had been locked into the same system of predation. There was Howell Collins, whose contract called for him to pay $25,500 for a house that a speculator had bought for $14,500. There was Ruth Wells, who’d managed to pay out half her contract, expecting a mortgage, only to suddenly see an insurance bill materialize out of thin air—a requirement the seller had added without Wells’s knowledge. Contract sellers used every tool at their disposal to pilfer from their clients. They scared white residents into selling low. They lied about properties’ compliance with building codes, then left the buyer responsible when city inspectors arrived. They presented themselves as real-estate brokers, when in fact they were the owners. They guided their clients to lawyers who were in on the scheme.

The Contract Buyers League fought back. Members—who would eventually number more than 500—went out to the posh suburbs where the speculators lived and embarrassed them by knocking on their neighbors’ doors and informing them of the details of the contract-lending trade. They refused to pay their installments, instead holding monthly payments in an escrow account. Then they brought a suit against the contract sellers, accusing them of buying properties and reselling in such a manner “to reap from members of the Negro race large and unjust profits.”

Video: The Contract Buyers League

In return for the “deprivations of their rights and privileges under the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments,” the league demanded “prayers for relief”—payback of all moneys paid on contracts and all moneys paid for structural improvement of properties, at 6 percent interest minus a “fair, non-discriminatory” rental price for time of occupation. Moreover, the league asked the court to adjudge that the defendants had “acted willfully and maliciously and that malice is the gist of this action.”

Ross and the Contract Buyers League were no longer appealing to the government simply for equality. They were no longer fleeing in hopes of a better deal elsewhere. They were charging society with a crime against their community. They wanted the crime publicly ruled as such. They wanted the crime’s executors declared to be offensive to society. And they wanted restitution for the great injury brought upon them by said offenders. In 1968, Clyde Ross and the Contract Buyers League were no longer simply seeking the protection of the law. They were seeking reparations.

II. “A Difference of Kind, Not Degree”

A ccording to the most-recent statistics , North Lawndale is now on the wrong end of virtually every socioeconomic indicator. In 1930 its population was 112,000. Today it is 36,000. The halcyon talk of “interracial living” is dead. The neighborhood is 92 percent black. Its homicide rate is 45 per 100,000—triple the rate of the city as a whole. The infant-mortality rate is 14 per 1,000—more than twice the national average. Forty-three percent of the people in North Lawndale live below the poverty line—double Chicago’s overall rate. Forty-five percent of all households are on food stamps—nearly three times the rate of the city at large. Sears, Roebuck left the neighborhood in 1987, taking 1,800 jobs with it. Kids in North Lawndale need not be confused about their prospects: Cook County’s Juvenile Temporary Detention Center sits directly adjacent to the neighborhood.

North Lawndale is an extreme portrait of the trends that ail black Chicago. Such is the magnitude of these ailments that it can be said that blacks and whites do not inhabit the same city. The average per capita income of Chicago’s white neighborhoods is almost three times that of its black neighborhoods. When the Harvard sociologist Robert J. Sampson examined incarceration rates in Chicago in his 2012 book, Great American City , he found that a black neighborhood with one of the highest incarceration rates (West Garfield Park) had a rate more than 40 times as high as the white neighborhood with the highest rate (Clearing). “This is a staggering differential, even for community-level comparisons,” Sampson writes. “A difference of kind, not degree.”

Interactive Census Map

In other words, Chicago’s impoverished black neighborhoods—characterized by high unemployment and households headed by single parents—are not simply poor; they are “ecologically distinct.” This “is not simply the same thing as low economic status,” writes Sampson. “In this pattern Chicago is not alone.”

The lives of black Americans are better than they were half a century ago. The humiliation of Whites Only signs are gone. Rates of black poverty have decreased. Black teen-pregnancy rates are at record lows—and the gap between black and white teen-pregnancy rates has shrunk significantly. But such progress rests on a shaky foundation, and fault lines are everywhere. The income gap between black and white households is roughly the same today as it was in 1970. Patrick Sharkey, a sociologist at New York University, studied children born from 1955 through 1970 and found that 4 percent of whites and 62 percent of blacks across America had been raised in poor neighborhoods. A generation later, the same study showed, virtually nothing had changed. And whereas whites born into affluent neighborhoods tended to remain in affluent neighborhoods, blacks tended to fall out of them.

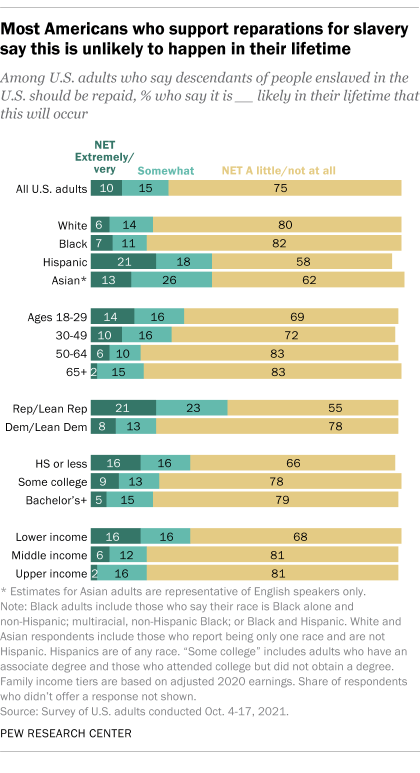

This is not surprising. Black families, regardless of income, are significantly less wealthy than white families. The Pew Research Center estimates that white households are worth roughly 20 times as much as black households, and that whereas only 15 percent of whites have zero or negative wealth, more than a third of blacks do. Effectively, the black family in America is working without a safety net. When financial calamity strikes—a medical emergency, divorce, job loss—the fall is precipitous.

And just as black families of all incomes remain handicapped by a lack of wealth, so too do they remain handicapped by their restricted choice of neighborhood. Black people with upper-middle-class incomes do not generally live in upper-middle-class neighborhoods. Sharkey’s research shows that black families making $100,000 typically live in the kinds of neighborhoods inhabited by white families making $30,000. “Blacks and whites inhabit such different neighborhoods,” Sharkey writes, “that it is not possible to compare the economic outcomes of black and white children.”

The implications are chilling. As a rule, poor black people do not work their way out of the ghetto—and those who do often face the horror of watching their children and grandchildren tumble back .

Even seeming evidence of progress withers under harsh light. In 2012, the Manhattan Institute cheerily noted that segregation had declined since the 1960s. And yet African Americans still remained—by far—the most segregated ethnic group in the country.

With segregation, with the isolation of the injured and the robbed, comes the concentration of disadvantage. An unsegregated America might see poverty, and all its effects, spread across the country with no particular bias toward skin color. Instead, the concentration of poverty has been paired with a concentration of melanin. The resulting conflagration has been devastating.

One thread of thinking in the African American community holds that these depressing numbers partially stem from cultural pathologies that can be altered through individual grit and exceptionally good behavior. (In 2011, Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter, responding to violence among young black males, put the blame on the family: “Too many men making too many babies they don’t want to take care of, and then we end up dealing with your children.” Nutter turned to those presumably fatherless babies: “Pull your pants up and buy a belt, because no one wants to see your underwear or the crack of your butt.”) The thread is as old as black politics itself. It is also wrong. The kind of trenchant racism to which black people have persistently been subjected can never be defeated by making its victims more respectable. The essence of American racism is disrespect. And in the wake of the grim numbers, we see the grim inheritance.

The Contract Buyers League’s suit brought by Clyde Ross and his allies took direct aim at this inheritance. The suit was rooted in Chicago’s long history of segregation, which had created two housing markets—one legitimate and backed by the government, the other lawless and patrolled by predators. The suit dragged on until 1976, when the league lost a jury trial. Securing the equal protection of the law proved hard; securing reparations proved impossible. If there were any doubts about the mood of the jury, the foreman removed them by saying, when asked about the verdict, that he hoped it would help end “the mess Earl Warren made with Brown v. Board of Education and all that nonsense.”

The Supreme Court seems to share that sentiment. The past two decades have witnessed a rollback of the progressive legislation of the 1960s. Liberals have found themselves on the defensive. In 2008, when Barack Obama was a candidate for president, he was asked whether his daughters—Malia and Sasha—should benefit from affirmative action. He answered in the negative.

The exchange rested upon an erroneous comparison of the average American white family and the exceptional first family. In the contest of upward mobility, Barack and Michelle Obama have won. But they’ve won by being twice as good—and enduring twice as much. Malia and Sasha Obama enjoy privileges beyond the average white child’s dreams. But that comparison is incomplete. The more telling question is how they compare with Jenna and Barbara Bush—the products of many generations of privilege, not just one. Whatever the Obama children achieve, it will be evidence of their family’s singular perseverance, not of broad equality.

III. “We Inherit Our Ample Patrimony”

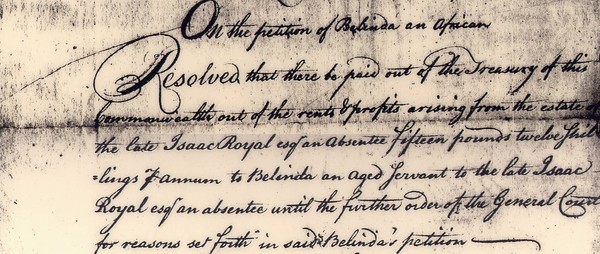

In 1783 , the freedwoman Belinda Royall petitioned the commonwealth of Massachusetts for reparations. Belinda had been born in modern-day Ghana. She was kidnapped as a child and sold into slavery. She endured the Middle Passage and 50 years of enslavement at the hands of Isaac Royall and his son. But the junior Royall, a British loyalist, fled the country during the Revolution. Belinda, now free after half a century of labor, beseeched the nascent Massachusetts legislature:

The face of your Petitioner, is now marked with the furrows of time, and her frame bending under the oppression of years, while she, by the Laws of the Land, is denied the employment of one morsel of that immense wealth, apart whereof hath been accumilated by her own industry, and the whole augmented by her servitude. WHEREFORE, casting herself at your feet if your honours, as to a body of men, formed for the extirpation of vassalage, for the reward of Virtue, and the just return of honest industry—she prays, that such allowance may be made her out of the Estate of Colonel Royall, as will prevent her, and her more infirm daughter, from misery in the greatest extreme, and scatter comfort over the short and downward path of their lives.

Belinda Royall was granted a pension of 15 pounds and 12 shillings, to be paid out of the estate of Isaac Royall—one of the earliest successful attempts to petition for reparations. At the time, black people in America had endured more than 150 years of enslavement, and the idea that they might be owed something in return was, if not the national consensus, at least not outrageous.

“A heavy account lies against us as a civil society for oppressions committed against people who did not injure us,” wrote the Quaker John Woolman in 1769, “and that if the particular case of many individuals were fairly stated, it would appear that there was considerable due to them.”

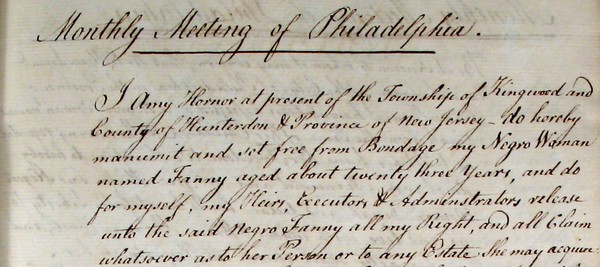

As the historian Roy E. Finkenbine has documented, at the dawn of this country, black reparations were actively considered and often effected. Quakers in New York, New England, and Baltimore went so far as to make “membership contingent upon compensating one’s former slaves.” In 1782, the Quaker Robert Pleasants emancipated his 78 slaves, granted them 350 acres, and later built a school on their property and provided for their education. “The doing of this justice to the injured Africans,” wrote Pleasants, “would be an acceptable offering to him who ‘Rules in the kingdom of men.’ ”

Edward Coles, a protégé of Thomas Jefferson who became a slaveholder through inheritance, took many of his slaves north and granted them a plot of land in Illinois. John Randolph, a cousin of Jefferson’s, willed that all his slaves be emancipated upon his death, and that all those older than 40 be given 10 acres of land. “I give and bequeath to all my slaves their freedom,” Randolph wrote, “heartily regretting that I have been the owner of one.”

In his book Forever Free , Eric Foner recounts the story of a disgruntled planter reprimanding a freedman loafing on the job:

Planter: “You lazy nigger, I am losing a whole day’s labor by you.” Freedman: “Massa, how many days’ labor have I lost by you?”

In the 20th century, the cause of reparations was taken up by a diverse cast that included the Confederate veteran Walter R. Vaughan, who believed that reparations would be a stimulus for the South; the black activist Callie House; black-nationalist leaders like “Queen Mother” Audley Moore; and the civil-rights activist James Forman. The movement coalesced in 1987 under an umbrella organization called the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America ( N’COBRA ). The NAACP endorsed reparations in 1993. Charles J. Ogletree Jr., a professor at Harvard Law School, has pursued reparations claims in court.

But while the people advocating reparations have changed over time, the response from the country has remained virtually the same. “They have been taught to labor,” the Chicago Tribune editorialized in 1891. “They have been taught Christian civilization, and to speak the noble English language instead of some African gibberish. The account is square with the ex‑slaves.”

Not exactly. Having been enslaved for 250 years, black people were not left to their own devices. They were terrorized. In the Deep South, a second slavery ruled. In the North, legislatures, mayors, civic associations, banks, and citizens all colluded to pin black people into ghettos, where they were overcrowded, overcharged, and undereducated. Businesses discriminated against them, awarding them the worst jobs and the worst wages. Police brutalized them in the streets. And the notion that black lives, black bodies, and black wealth were rightful targets remained deeply rooted in the broader society. Now we have half-stepped away from our long centuries of despoilment, promising, “Never again.” But still we are haunted. It is as though we have run up a credit-card bill and, having pledged to charge no more, remain befuddled that the balance does not disappear. The effects of that balance, interest accruing daily, are all around us.

Broach the topic of reparations today and a barrage of questions inevitably follows: Who will be paid? How much will they be paid? Who will pay? But if the practicalities, not the justice, of reparations are the true sticking point, there has for some time been the beginnings of a solution. For the past 25 years, Congressman John Conyers Jr., who represents the Detroit area, has marked every session of Congress by introducing a bill calling for a congressional study of slavery and its lingering effects as well as recommendations for “appropriate remedies.”

A country curious about how reparations might actually work has an easy solution in Conyers’s bill, now called HR 40, the Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act. We would support this bill, submit the question to study, and then assess the possible solutions. But we are not interested.

“It’s because it’s black folks making the claim,” Nkechi Taifa, who helped found N’COBRA , says. “People who talk about reparations are considered left lunatics. But all we are talking about is studying [reparations]. As John Conyers has said, we study everything. We study the water, the air. We can’t even study the issue? This bill does not authorize one red cent to anyone.”

That HR 40 has never—under either Democrats or Republicans—made it to the House floor suggests our concerns are rooted not in the impracticality of reparations but in something more existential. If we conclude that the conditions in North Lawndale and black America are not inexplicable but are instead precisely what you’d expect of a community that for centuries has lived in America’s crosshairs, then what are we to make of the world’s oldest democracy?

One cannot escape the question by hand-waving at the past, disavowing the acts of one’s ancestors, nor by citing a recent date of ancestral immigration. The last slaveholder has been dead for a very long time. The last soldier to endure Valley Forge has been dead much longer. To proudly claim the veteran and disown the slaveholder is patriotism à la carte. A nation outlives its generations. We were not there when Washington crossed the Delaware, but Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze’s rendering has meaning to us. We were not there when Woodrow Wilson took us into World War I, but we are still paying out the pensions. If Thomas Jefferson’s genius matters, then so does his taking of Sally Hemings’s body. If George Washington crossing the Delaware matters, so must his ruthless pursuit of the runagate Oney Judge.

In 1909, President William Howard Taft told the country that “intelligent” white southerners were ready to see blacks as “useful members of the community.” A week later Joseph Gordon, a black man, was lynched outside Greenwood, Mississippi. The high point of the lynching era has passed. But the memories of those robbed of their lives still live on in the lingering effects. Indeed, in America there is a strange and powerful belief that if you stab a black person 10 times, the bleeding stops and the healing begins the moment the assailant drops the knife. We believe white dominance to be a fact of the inert past, a delinquent debt that can be made to disappear if only we don’t look.

There has always been another way. “It is in vain to alledge, that our ancestors brought them hither, and not we,” Yale President Timothy Dwight said in 1810.

We inherit our ample patrimony with all its incumbrances; and are bound to pay the debts of our ancestors. This debt, particularly, we are bound to discharge: and, when the righteous Judge of the Universe comes to reckon with his servants, he will rigidly exact the payment at our hands. To give them liberty, and stop here, is to entail upon them a curse.

IV. “The Ills That Slavery Frees Us From”

A merica begins in black plunder and white democracy , two features that are not contradictory but complementary. “The men who came together to found the independent United States, dedicated to freedom and equality, either held slaves or were willing to join hands with those who did,” the historian Edmund S. Morgan wrote. “None of them felt entirely comfortable about the fact, but neither did they feel responsible for it. Most of them had inherited both their slaves and their attachment to freedom from an earlier generation, and they knew the two were not unconnected.”

When enslaved Africans, plundered of their bodies, plundered of their families, and plundered of their labor, were brought to the colony of Virginia in 1619, they did not initially endure the naked racism that would engulf their progeny. Some of them were freed. Some of them intermarried. Still others escaped with the white indentured servants who had suffered as they had. Some even rebelled together, allying under Nathaniel Bacon to torch Jamestown in 1676.

One hundred years later, the idea of slaves and poor whites joining forces would shock the senses, but in the early days of the English colonies, the two groups had much in common. English visitors to Virginia found that its masters “abuse their servantes with intollerable oppression and hard usage.” White servants were flogged, tricked into serving beyond their contracts, and traded in much the same manner as slaves.

This “hard usage” originated in a simple fact of the New World—land was boundless but cheap labor was limited. As life spans increased in the colony, the Virginia planters found in the enslaved Africans an even more efficient source of cheap labor. Whereas indentured servants were still legal subjects of the English crown and thus entitled to certain protections, African slaves entered the colonies as aliens. Exempted from the protections of the crown, they became early America’s indispensable working class—fit for maximum exploitation, capable of only minimal resistance.

For the next 250 years, American law worked to reduce black people to a class of untouchables and raise all white men to the level of citizens. In 1650, Virginia mandated that “all persons except Negroes” were to carry arms. In 1664, Maryland mandated that any Englishwoman who married a slave must live as a slave of her husband’s master. In 1705, the Virginia assembly passed a law allowing for the dismemberment of unruly slaves—but forbidding masters from whipping “a Christian white servant naked, without an order from a justice of the peace.” In that same law, the colony mandated that “all horses, cattle, and hogs, now belonging, or that hereafter shall belong to any slave” be seized and sold off by the local church, the profits used to support “the poor of the said parish.” At that time, there would have still been people alive who could remember blacks and whites joining to burn down Jamestown only 29 years before. But at the beginning of the 18th century, two primary classes were enshrined in America.

“The two great divisions of society are not the rich and poor, but white and black,” John C. Calhoun, South Carolina’s senior senator, declared on the Senate floor in 1848. “And all the former, the poor as well as the rich, belong to the upper class, and are respected and treated as equals.”

In 1860, the majority of people living in South Carolina and Mississippi, almost half of those living in Georgia, and about one-third of all Southerners were on the wrong side of Calhoun’s line. The state with the largest number of enslaved Americans was Virginia, where in certain counties some 70 percent of all people labored in chains. Nearly one-fourth of all white Southerners owned slaves, and upon their backs the economic basis of America—and much of the Atlantic world—was erected. In the seven cotton states, one-third of all white income was derived from slavery. By 1840, cotton produced by slave labor constituted 59 percent of the country’s exports. The web of this slave society extended north to the looms of New England, and across the Atlantic to Great Britain, where it powered a great economic transformation and altered the trajectory of world history. “Whoever says Industrial Revolution,” wrote the historian Eric J. Hobsbawm, “says cotton.”

The wealth accorded America by slavery was not just in what the slaves pulled from the land but in the slaves themselves. “In 1860, slaves as an asset were worth more than all of America’s manufacturing, all of the railroads, all of the productive capacity of the United States put together,” the Yale historian David W. Blight has noted. “Slaves were the single largest, by far, financial asset of property in the entire American economy.” The sale of these slaves—“in whose bodies that money congealed,” writes Walter Johnson, a Harvard historian—generated even more ancillary wealth. Loans were taken out for purchase, to be repaid with interest. Insurance policies were drafted against the untimely death of a slave and the loss of potential profits. Slave sales were taxed and notarized. The vending of the black body and the sundering of the black family became an economy unto themselves, estimated to have brought in tens of millions of dollars to antebellum America. In 1860 there were more millionaires per capita in the Mississippi Valley than anywhere else in the country.

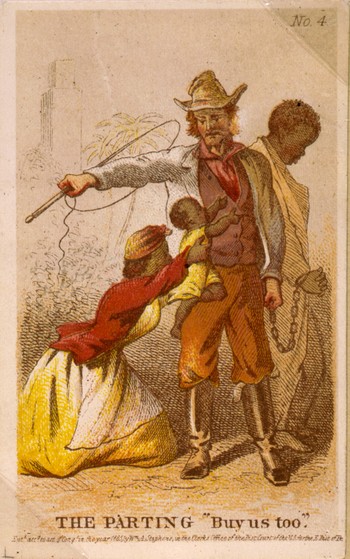

Beneath the cold numbers lay lives divided. “I had a constant dread that Mrs. Moore, her mistress, would be in want of money and sell my dear wife,” a freedman wrote, reflecting on his time in slavery. “We constantly dreaded a final separation. Our affection for each was very strong, and this made us always apprehensive of a cruel parting.”

Forced partings were common in the antebellum South. A slave in some parts of the region stood a 30 percent chance of being sold in his or her lifetime. Twenty-five percent of interstate trades destroyed a first marriage and half of them destroyed a nuclear family.

When the wife and children of Henry Brown, a slave in Richmond, Virginia, were to be sold away, Brown searched for a white master who might buy his wife and children to keep the family together. He failed:

The next day, I stationed myself by the side of the road, along which the slaves, amounting to three hundred and fifty, were to pass. The purchaser of my wife was a Methodist minister, who was about starting for North Carolina. Pretty soon five waggon-loads of little children passed, and looking at the foremost one, what should I see but a little child, pointing its tiny hand towards me, exclaiming, “There’s my father; I knew he would come and bid me good-bye.” It was my eldest child! Soon the gang approached in which my wife was chained. I looked, and beheld her familiar face; but O, reader, that glance of agony! may God spare me ever again enduring the excruciating horror of that moment! She passed, and came near to where I stood. I seized hold of her hand, intending to bid her farewell; but words failed me; the gift of utterance had fled, and I remained speechless. I followed her for some distance, with her hand grasped in mine, as if to save her from her fate, but I could not speak, and I was obliged to turn away in silence.

In a time when telecommunications were primitive and blacks lacked freedom of movement, the parting of black families was a kind of murder. Here we find the roots of American wealth and democracy—in the for-profit destruction of the most important asset available to any people, the family. The destruction was not incidental to America’s rise; it facilitated that rise. By erecting a slave society, America created the economic foundation for its great experiment in democracy. The labor strife that seeded Bacon’s rebellion was suppressed. America’s indispensable working class existed as property beyond the realm of politics, leaving white Americans free to trumpet their love of freedom and democratic values. Assessing antebellum democracy in Virginia, a visitor from England observed that the state’s natives “can profess an unbounded love of liberty and of democracy in consequence of the mass of the people, who in other countries might become mobs, being there nearly altogether composed of their own Negro slaves.”

V. The Quiet Plunder

The consequences of 250 years of enslavement, of war upon black families and black people, were profound. Like homeownership today, slave ownership was aspirational, attracting not just those who owned slaves but those who wished to. Much as homeowners today might discuss the addition of a patio or the painting of a living room, slaveholders traded tips on the best methods for breeding workers, exacting labor, and doling out punishment. Just as a homeowner today might subscribe to a magazine like This Old House , slaveholders had journals such as De Bow’s Review , which recommended the best practices for wringing profits from slaves. By the dawn of the Civil War, the enslavement of black America was thought to be so foundational to the country that those who sought to end it were branded heretics worthy of death. Imagine what would happen if a president today came out in favor of taking all American homes from their owners: the reaction might well be violent.

“This country was formed for the white , not for the black man,” John Wilkes Booth wrote, before killing Abraham Lincoln. “And looking upon African slavery from the same standpoint held by those noble framers of our Constitution, I for one have ever considered it one of the greatest blessings (both for themselves and us) that God ever bestowed upon a favored nation.”

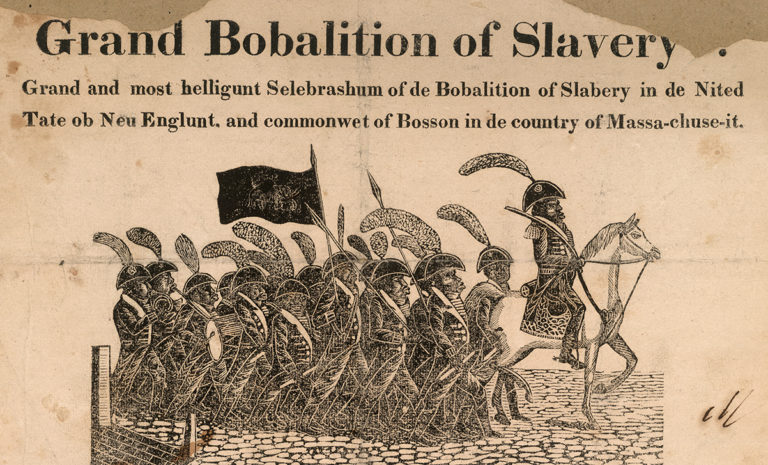

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Radical Republicans attempted to reconstruct the country upon something resembling universal equality—but they were beaten back by a campaign of “Redemption,” led by White Liners, Red Shirts, and Klansmen bent on upholding a society “formed for the white , not for the black man.” A wave of terrorism roiled the South. In his massive history Reconstruction , Eric Foner recounts incidents of black people being attacked for not removing their hats; for refusing to hand over a whiskey flask; for disobeying church procedures; for “using insolent language”; for disputing labor contracts; for refusing to be “tied like a slave.” Sometimes the attacks were intended simply to “thin out the niggers a little.”

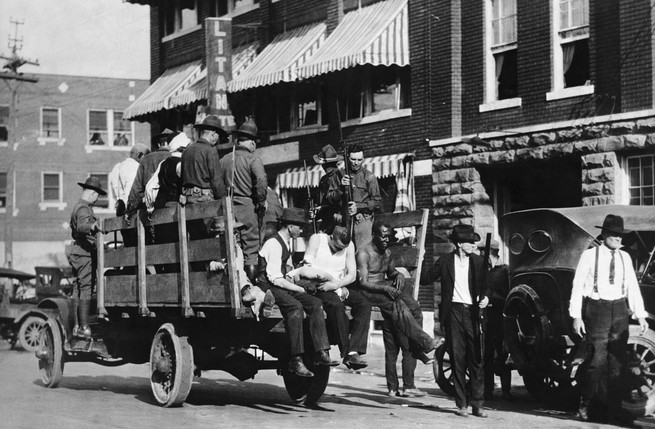

Terrorism carried the day. Federal troops withdrew from the South in 1877. The dream of Reconstruction died. For the next century, political violence was visited upon blacks wantonly, with special treatment meted out toward black people of ambition. Black schools and churches were burned to the ground. Black voters and the political candidates who attempted to rally them were intimidated, and some were murdered. At the end of World War I, black veterans returning to their homes were assaulted for daring to wear the American uniform. The demobilization of soldiers after the war, which put white and black veterans into competition for scarce jobs, produced the Red Summer of 1919: a succession of racist pogroms against dozens of cities ranging from Longview, Texas, to Chicago to Washington, D.C. Organized white violence against blacks continued into the 1920s—in 1921 a white mob leveled Tulsa’s “Black Wall Street,” and in 1923 another one razed the black town of Rosewood, Florida—and virtually no one was punished.

The work of mobs was a rabid and violent rendition of prejudices that extended even into the upper reaches of American government. The New Deal is today remembered as a model for what progressive government should do—cast a broad social safety net that protects the poor and the afflicted while building the middle class. When progressives wish to express their disappointment with Barack Obama, they point to the accomplishments of Franklin Roosevelt. But these progressives rarely note that Roosevelt’s New Deal, much like the democracy that produced it, rested on the foundation of Jim Crow.

“The Jim Crow South,” writes Ira Katznelson, a history and political-science professor at Columbia, “was the one collaborator America’s democracy could not do without.” The marks of that collaboration are all over the New Deal. The omnibus programs passed under the Social Security Act in 1935 were crafted in such a way as to protect the southern way of life. Old-age insurance (Social Security proper) and unemployment insurance excluded farmworkers and domestics—jobs heavily occupied by blacks. When President Roosevelt signed Social Security into law in 1935, 65 percent of African Americans nationally and between 70 and 80 percent in the South were ineligible. The NAACP protested, calling the new American safety net “a sieve with holes just big enough for the majority of Negroes to fall through.”

The oft-celebrated G.I. Bill similarly failed black Americans, by mirroring the broader country’s insistence on a racist housing policy. Though ostensibly color-blind, Title III of the bill, which aimed to give veterans access to low-interest home loans, left black veterans to tangle with white officials at their local Veterans Administration as well as with the same banks that had, for years, refused to grant mortgages to blacks. The historian Kathleen J. Frydl observes in her 2009 book, The GI Bill , that so many blacks were disqualified from receiving Title III benefits “that it is more accurate simply to say that blacks could not use this particular title.”

In Cold War America, homeownership was seen as a means of instilling patriotism, and as a civilizing and anti-radical force. “No man who owns his own house and lot can be a Communist,” claimed William Levitt, who pioneered the modern suburb with the development of the various Levittowns, his famous planned communities. “He has too much to do.”

But the Levittowns were, with Levitt’s willing acquiescence, segregated throughout their early years. Daisy and Bill Myers, the first black family to move into Levittown, Pennsylvania, were greeted with protests and a burning cross. A neighbor who opposed the family said that Bill Myers was “probably a nice guy, but every time I look at him I see $2,000 drop off the value of my house.”

The neighbor had good reason to be afraid. Bill and Daisy Myers were from the other side of John C. Calhoun’s dual society. If they moved next door, housing policy almost guaranteed that their neighbors’ property values would decline.

Whereas shortly before the New Deal, a typical mortgage required a large down payment and full repayment within about 10 years, the creation of the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation in 1933 and then the Federal Housing Administration the following year allowed banks to offer loans requiring no more than 10 percent down, amortized over 20 to 30 years. “Without federal intervention in the housing market, massive suburbanization would have been impossible,” writes Thomas J. Sugrue, a historian at the University of Pennsylvania. “In 1930, only 30 percent of Americans owned their own homes; by 1960, more than 60 percent were home owners. Home ownership became an emblem of American citizenship.”

That emblem was not to be awarded to blacks. The American real-estate industry believed segregation to be a moral principle. As late as 1950, the National Association of Real Estate Boards’ code of ethics warned that “a Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood … any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values.” A 1943 brochure specified that such potential undesirables might include madams, bootleggers, gangsters—and “a colored man of means who was giving his children a college education and thought they were entitled to live among whites.”

The federal government concurred. It was the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, not a private trade association, that pioneered the practice of redlining, selectively granting loans and insisting that any property it insured be covered by a restrictive covenant—a clause in the deed forbidding the sale of the property to anyone other than whites. Millions of dollars flowed from tax coffers into segregated white neighborhoods.

“For perhaps the first time, the federal government embraced the discriminatory attitudes of the marketplace,” the historian Kenneth T. Jackson wrote in his 1985 book, Crabgrass Frontier , a history of suburbanization. “Previously, prejudices were personalized and individualized; FHA exhorted segregation and enshrined it as public policy. Whole areas of cities were declared ineligible for loan guarantees.” Redlining was not officially outlawed until 1968, by the Fair Housing Act. By then the damage was done—and reports of redlining by banks have continued.

The federal government is premised on equal fealty from all its citizens, who in return are to receive equal treatment. But as late as the mid-20th century, this bargain was not granted to black people, who repeatedly paid a higher price for citizenship and received less in return. Plunder had been the essential feature of slavery, of the society described by Calhoun. But practically a full century after the end of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, the plunder—quiet, systemic, submerged—continued even amidst the aims and achievements of New Deal liberals.

VI. Making The Second Ghetto

Today Chicago is one of the most segregated cities in the country, a fact that reflects assiduous planning. In the effort to uphold white supremacy at every level down to the neighborhood, Chicago—a city founded by the black fur trader Jean Baptiste Point du Sable—has long been a pioneer. The efforts began in earnest in 1917, when the Chicago Real Estate Board, horrified by the influx of southern blacks, lobbied to zone the entire city by race. But after the Supreme Court ruled against explicit racial zoning that year, the city was forced to pursue its agenda by more-discreet means.

Like the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, the Federal Housing Administration initially insisted on restrictive covenants, which helped bar blacks and other ethnic undesirables from receiving federally backed home loans. By the 1940s, Chicago led the nation in the use of these restrictive covenants, and about half of all residential neighborhoods in the city were effectively off-limits to blacks.

It is common today to become misty-eyed about the old black ghetto, where doctors and lawyers lived next door to meatpackers and steelworkers, who themselves lived next door to prostitutes and the unemployed. This segregationist nostalgia ignores the actual conditions endured by the people living there—vermin and arson, for instance—and ignores the fact that the old ghetto was premised on denying black people privileges enjoyed by white Americans.

In 1948, when the Supreme Court ruled that restrictive covenants, while permissible, were not enforceable by judicial action, Chicago had other weapons at the ready. The Illinois state legislature had already given Chicago’s city council the right to approve—and thus to veto—any public housing in the city’s wards. This came in handy in 1949, when a new federal housing act sent millions of tax dollars into Chicago and other cities around the country. Beginning in 1950, site selection for public housing proceeded entirely on the grounds of segregation. By the 1960s, the city had created with its vast housing projects what the historian Arnold R. Hirsch calls a “second ghetto,” one larger than the old Black Belt but just as impermeable. More than 98 percent of all the family public-housing units built in Chicago between 1950 and the mid‑1960s were built in all-black neighborhoods.

Governmental embrace of segregation was driven by the virulent racism of Chicago’s white citizens. White neighborhoods vulnerable to black encroachment formed block associations for the sole purpose of enforcing segregation. They lobbied fellow whites not to sell. They lobbied those blacks who did manage to buy to sell back. In 1949, a group of Englewood Catholics formed block associations intended to “keep up the neighborhood.” Translation: keep black people out. And when civic engagement was not enough, when government failed, when private banks could no longer hold the line, Chicago turned to an old tool in the American repertoire—racial violence. “The pattern of terrorism is easily discernible,” concluded a Chicago civic group in the 1940s. “It is at the seams of the black ghetto in all directions.” On July 1 and 2 of 1946, a mob of thousands assembled in Chicago’s Park Manor neighborhood, hoping to eject a black doctor who’d recently moved in. The mob pelted the house with rocks and set the garage on fire. The doctor moved away.

In 1947, after a few black veterans moved into the Fernwood section of Chicago, three nights of rioting broke out; gangs of whites yanked blacks off streetcars and beat them. Two years later, when a union meeting attended by blacks in Englewood triggered rumors that a home was being “sold to niggers,” blacks (and whites thought to be sympathetic to them) were beaten in the streets. In 1951, thousands of whites in Cicero, 20 minutes or so west of downtown Chicago, attacked an apartment building that housed a single black family, throwing bricks and firebombs through the windows and setting the apartment on fire. A Cook County grand jury declined to charge the rioters—and instead indicted the family’s NAACP attorney, the apartment’s white owner, and the owner’s attorney and rental agent, charging them with conspiring to lower property values. Two years after that, whites picketed and planted explosives in South Deering, about 30 minutes from downtown Chicago, to force blacks out.

When terrorism ultimately failed, white homeowners simply fled the neighborhood. The traditional terminology, white flight , implies a kind of natural expression of preference. In fact, white flight was a triumph of social engineering, orchestrated by the shared racist presumptions of America’s public and private sectors. For should any nonracist white families decide that integration might not be so bad as a matter of principle or practicality, they still had to contend with the hard facts of American housing policy: When the mid-20th-century white homeowner claimed that the presence of a Bill and Daisy Myers decreased his property value, he was not merely engaging in racist dogma—he was accurately observing the impact of federal policy on market prices. Redlining destroyed the possibility of investment wherever black people lived.

VII. “A Lot Of People Fell By The Way”

Speculators in North Lawndale , and at the edge of the black ghettos, knew there was money to be made off white panic. They resorted to “block-busting”—spooking whites into selling cheap before the neighborhood became black. They would hire a black woman to walk up and down the street with a stroller. Or they’d hire someone to call a number in the neighborhood looking for “Johnny Mae.” Then they’d cajole whites into selling at low prices, informing them that the more blacks who moved in, the more the value of their homes would decline, so better to sell now. With these white-fled homes in hand, speculators then turned to the masses of black people who had streamed northward as part of the Great Migration, or who were desperate to escape the ghettos: the speculators would take the houses they’d just bought cheap through block-busting and sell them to blacks on contract.

To keep up with his payments and keep his heat on, Clyde Ross took a second job at the post office and then a third job delivering pizza. His wife took a job working at Marshall Field. He had to take some of his children out of private school. He was not able to be at home to supervise his children or help them with their homework. Money and time that Ross wanted to give his children went instead to enrich white speculators.

“The problem was the money,” Ross told me. “Without the money, you can’t move. You can’t educate your kids. You can’t give them the right kind of food. Can’t make the house look good. They think this neighborhood is where they supposed to be. It changes their outlook. My kids were going to the best schools in this neighborhood, and I couldn’t keep them in there.”