The Importance of Technological Change in Shaping Generational Perspectives

If we name each generation based on the technological conditions it experienced, generations may soon encompass only a few years apiece.

“There are a number of labels to describe the young people currently studying at school, college and university,” Ellen John Helsper and Rebecca Evnon wrote in a 2010 article in the British Educational Research Journal . “They include the digital natives, the net generation, the Google generation or the millenials. All of these terms are being used to highlight the significance and importance of new technologies within the lives of young people.”

What seemed noteworthy a decade ago is now commonplace: Slicing the population into ever-narrower generations, each defined by its very specific relationship to technology, is fundamental to how we think about the relationship between age, culture, and technology.

But generation gaps did not begin with the invention of the microchip. What’s new is the fine-slicing of generational divides, the centrality of technology to defining each successive generation. Both of these developments rest on a remarkably intellectual innovation: the idea of generations as socially significant categories.

As Marius Hentea points out in his article “ The Problem of Literary Generations :” “[t]he sociological meaning of ‘generation’ is a post-Enlightenment development.” We’ve moved from a view of generations as biological “in the sense of the generation of a butterfly from a caterpillar,” as Hentea puts it, to a view of generations as sociological. Hentea argues that three nineteenth-century developments were responsible for this emergent concept of generational divides, the first of which was democratization :

By no longer limiting political power to a defined group but rather encouraging political participation across social strata, democracy eased youth into public life in a way other regimes had proven incapable of doing. At the same time, democratization paradoxically created generational categories. With aristocratic privileges abolished and republican duties diminished, the generation provided a fallback for social belonging: not everyone can belong to my generation, so the vestigial desire for distinction is satisfied, but at the same time, no one remains without a generation, so the democratic impulse toward equality is met.

Another important factor was centralization : “the spectacular rise of the bureaucratic state and its disciplinary instruments of control and categorization.” Last but not least, Hentea notes, was the role of technologization :

As technology advanced ever more quickly in the nineteenth century, differentiation based on age became even more important: the young had at their disposal tools their elders did not. The concentration of rapid technological change in urban centers led to youth gaining economic and social advantages at the same time that the transmission of accumulated knowledge and experience from elders lost its relevance for changing industries.

If the role of technology in shaping an emergent generational consciousness seems obvious to us now, however, it far from evident to earlier observers. “Why does contemporary western civilization manifest an extraordinary amount of parent-adolescent conflict?” Kinsley Davis asked in his article “ The Sociology of Parent-Youth Conflict .” In 1940, apparently, it was still possible to see inter-generational conflict as a novel and perplexing mystery.

To one of Davis’ contemporaries, the answer was clear: “the two generations in question have lived under such different economic conditions,” wrote Julien Brenda in a 1938 article, “ The Conflict of Generations in France .” “The old generation was a happy one—unusually happy, I venture to say; the young generation is unhappy, hard pressed by circumstances.”

Wallace Stegner picks up the theme of generational angst in his 1949 article, “ The Anxious Generation .” Writing of the twenty-somethings who came of age during or just after World War II, Stegner says:

They could no more have missed awareness of the tension and fear in their world than a bird could avoid awareness of wind. Far more has been taken from them than had been taken from preceding generations: politically, only uncertainty and fear and the Cold War is left them; the atom bomb is a threat such as the world has a never faced; if by a miracle we escape another war and the bomb, there is always the longer-term disaster of an incredibly multiplying world population and the shrinkage and wastage of world resources and the diminishing of world food supplies.

If that rather grim assessment implicitly rests on a set of assumptions about the impact of technological change—for what else is an atom bomb, if not a technological innovation?—then that assessment only seems apparent through our twenty-first century lens. In the middle of the last century, many still thought it preposterous to attribute generational differences to technological innovation. Writing in the middle of World War II, C. E. Ayres wrote that:

No serious student attributes the evils of the age to its machines. Popular essayists sometimes write as though tanks and airplanes were responsible for the bloodshed which is now going on, and novelists occasionally draw pictures of the horrors of a future in which life will have become wholly mechanized, with babies germinating in test tubes, “scientifically” maimed for the “more efficient” performance of industrial tasks. But this of course is literary nonsense…

Just a few years later, however, A. J. Jaffe would take a very different position in the pages of Scientific Monthly. “ Of the factors causing change in our society, one of the most important is technology—important new inventions as well as minor technical innovations,” Jaffe wrote in “ Technological Innovations and the Changing Socioeconomic Structure .” Making the case for the importance of studying technological change, Jaffe argued that:

Perhaps the single most important reason for studying technological change is to afford society a mechanism for predicting the social changes which are expected to occur… any thinking that will permit a society to better adapt itself to the inevitable changes which will occur—changes stemming in large measure from technological innovations—will be better able to meet such changes.

If that seems like a rather rapid turnaround on the importance of technological change in shaping generational perspectives, well, the pace of change was very much the point. In a 1945 article, “ Characteristics of an Age of Change ,” J. B. McKinney observed that “change, which was hitherto a gradual process, has become, for us, cataclysmic; it has become a tidal wave that threatens to overwhelm us. A decade to-day is the equivalent of a generation, and standards and values topple over like ninepins.”

From this rapid change, it was perceived, sprang generational discord. In his 1940 article, Davis argued that:

Extremely rapid change in modern civilization… tends to increase parent-youth conflict, for within a fast-changing social order the time-interval between generations, ordinarily but a mere moment in the life of a social system, become historically significant, thereby creating a hiatus between one generation and the next. Inevitably, under such a condition, youth is reared in a milieu different from that of the parents; hence the parents become old-fashioned, youth rebellious, and clashes occur which, in the closely confined circle of the immediate family, generate sharp emotion.

This 80-year-old assertion does an excellent job of anticipating our current tendency to label a new generation every decade, based on its unique relationship to emergent technology. Smartphones have only been in widespread use for a decade, but they’re now so fundamental to our daily lives that it’s hard to remember life without them. How could we possibly see those who can remember life before the smartphone as part of the same generation as those who’ve known nothing else? How could we see kids who’ve grown up on YouTube as part of the same generation that still watched actual TV? Doesn’t the leap from Facebook to SnapChat constitute its own profound generational divide?

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

As the pace of technological innovation continues to accelerate, and as each successive round of innovation becomes more widely disseminated, it’s hard to imagine a return to the days when sociological generations spanned multiple decades. If you believe that technological conditions profoundly shape the life experience and perspectives of each successive generation, then those generations will only get narrower.

But that accuracy will come at a price. If we name each generation based on the specific technological conditions it experienced during childhood or adolescence, we may soon be dealing with generations that encompass only a few years apiece. At that point, the very idea of “generations” will cease to have much utility for social scientists, since it will be very hard to analyze attitudinal or behavioral differences between generations that are just a few years part. We’ll have come full circle, back to the early nineteenth century, when the only way to think of generations was in terms of biology, not sociology.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

- Meteorite Strike in South Africa

HMS Challenger and the History of Science at Sea

Astronomers Have Warned against Colonial Practices in the Space Industry

Tree of Peace, Spark of War

Recent posts.

- Richard Gregg: An American Pioneer of Nonviolence Remembered

- The Gift of the Grange

- L. M. Montgomery’s Plain Jane

- Where Are the Trees?

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

How Teens Today Are Different from Past Generations

Every generation of teens is shaped by the social, political, and economic events of the day. Today’s teenagers are no different—and they’re the first generation whose lives are saturated by mobile technology and social media.

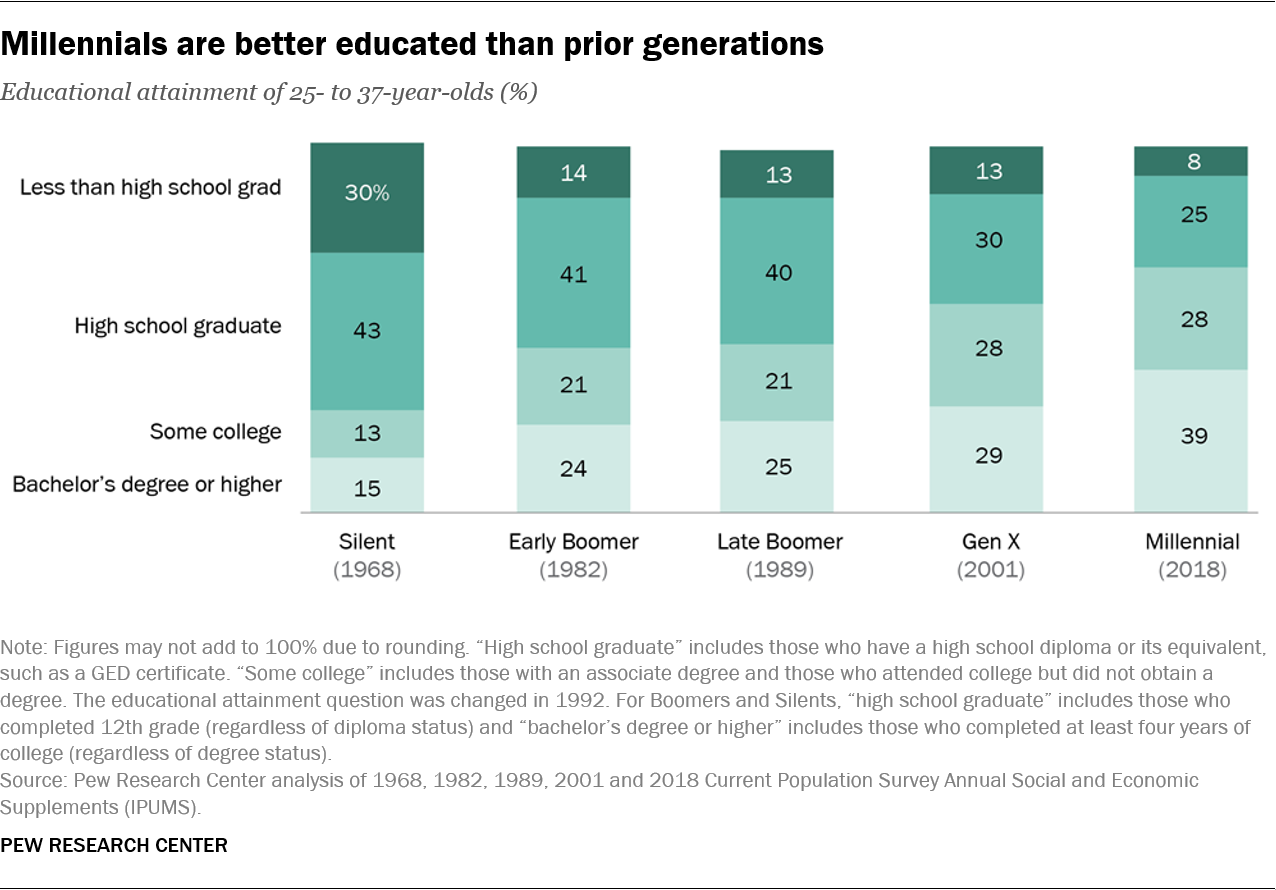

In her new book, psychologist Jean Twenge uses large-scale surveys to draw a detailed portrait of ten qualities that make today’s teens unique and the cultural forces shaping them. Her findings are by turn alarming, informative, surprising, and insightful, making the book— iGen:Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood—and What That Means for the Rest of Us —an important read for anyone interested in teens’ lives.

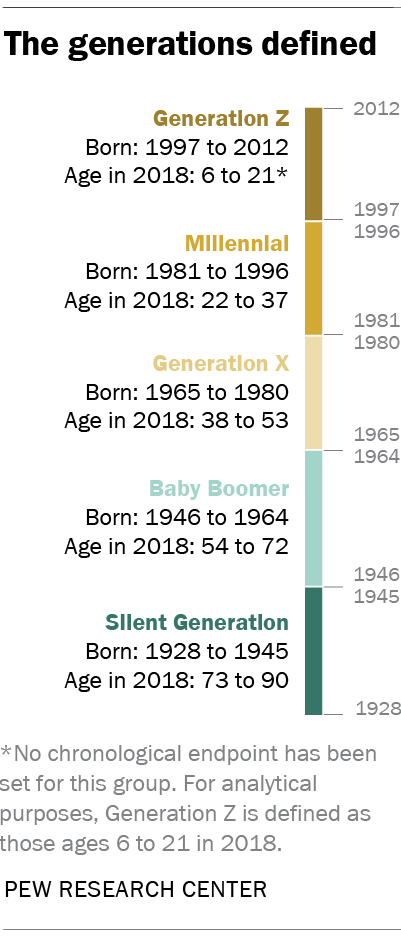

Who are the iGens?

Twenge names the generation born between 1995 and 2012 “iGens” for their ubiquitous use of the iPhone, their valuing of individualism, their economic context of income inequality, their inclusiveness, and more.

She identifies their unique qualities by analyzing four nationally representative surveys of 11 million teens since the 1960s. Those surveys, which have asked the same questions (and some new ones) of teens year after year, allow comparisons among Boomers, Gen Xers, Millennials, and iGens at exactly the same ages. In addition to identifying cross-generational trends in these surveys, Twenge tests her inferences against her own follow-up surveys, interviews with teens, and findings from smaller experimental studies. Here are just a few of her conclusions.

iGens have poorer emotional health thanks to new media. Twenge finds that new media is making teens more lonely, anxious, and depressed, and is undermining their social skills and even their sleep.

iGens “grew up with cell phones, had an Instagram page before they started high school, and do not remember a time before the Internet,” writes Twenge. They spend five to six hours a day texting, chatting, gaming, web surfing, streaming and sharing videos, and hanging out online. While other observers have equivocated about the impact, Twenge is clear: More than two hours a day raises the risk for serious mental health problems.

She draws these conclusions by showing how the national rise in teen mental health problems mirrors the market penetration of iPhones—both take an upswing around 2012. This is correlational data, but competing explanations like rising academic pressure or the Great Recession don’t seem to explain teens’ mental health issues. And experimental studies suggest that when teens give up Facebook for a period or spend time in nature without their phones, for example, they become happier.

The mental health consequences are especially acute for younger teens, she writes. This makes sense developmentally, since the onset of puberty triggers a cascade of changes in the brain that make teens more emotional and more sensitive to their social world.

Social media use, Twenge explains, means teens are spending less time with their friends in person. At the same time, online content creates unrealistic expectations (about happiness, body image, and more) and more opportunities for feeling left out—which scientists now know has similar effects as physical pain . Girls may be especially vulnerable, since they use social media more, report feeling left out more often than boys, and report twice the rate of cyberbullying as boys do.

Social media is creating an “epidemic of anguish,” Twenge says.

iGens grow up more slowly. iGens also appear more reluctant to grow up. They are more likely than previous generations to hang out with their parents, postpone sex, and decline driver’s licenses.

Twenge floats a fascinating hypothesis to explain this—one that is well-known in social science but seldom discussed outside academia. Life history theory argues that how fast teens grow up depends on their perceptions of their environment: When the environment is perceived as hostile and competitive, teens take a “fast life strategy,” growing up quickly, making larger families earlier, and focusing on survival. A “slow life strategy,” in contrast, occurs in safer environments and allows a greater investment in fewer children—more time for preschool soccer and kindergarten violin lessons.

“Youths of every racial group, region, and class are growing up more slowly,” says Twenge—a phenomenon she neither champions nor judges. However, employers and college administrators have complained about today’s teens’ lack of preparation for adulthood. In her popular book, How to Raise an Adult , Julie Lythcott-Haims writes that students entering college have been over-parented and as a result are timid about exploration, afraid to make mistakes, and unable to advocate for themselves.

Twenge suggests that the reality is more complicated. Today’s teens are legitimately closer to their parents than previous generations, but their life course has also been shaped by income inequality that demoralizes their hopes for the future. Compared to previous generations, iGens believe they have less control over how their lives turn out. Instead, they think that the system is already rigged against them—a dispiriting finding about a segment of the lifespan that is designed for creatively reimagining the future.

iGens exhibit more care for others. iGens, more than other generations, are respectful and inclusive of diversity of many kinds. Yet as a result, they reject offensive speech more than any earlier generation, and they are derided for their “fragility” and need for “ trigger warnings ” and “safe spaces.” (Trigger warnings are notifications that material to be covered may be distressing to some. A safe space is a zone that is absent of triggering rhetoric.)

Today’s colleges are tied in knots trying to reconcile their students’ increasing care for others with the importance of having open dialogue about difficult subjects. Dis-invitations to campus speakers are at an all-time high, more students believe the First Amendment is “outdated,” and some faculty have been fired for discussing race in their classrooms. Comedians are steering clear of college campuses, Twenge reports, afraid to offend.

The future of teen well-being

Social scientists will discuss Twenge’s data and conclusions for some time to come, and there is so much information—much of it correlational—there is bound to be a dropped stitch somewhere. For example, life history theory is a useful macro explanation for teens’ slow growth, but I wonder how income inequality or rising rates of insecure attachments among teens and their parents are contributing to this phenomenon. And Twenge claims that childhood has lengthened, but that runs counter to data showing earlier onset of puberty.

So what can we take away from Twenge’s thoughtful macro-analysis? The implicit lesson for parents is that we need more nuanced parenting. We can be close to our children and still foster self-reliance. We can allow some screen time for our teens and make sure the priority is still on in-person relationships. We can teach empathy and respect but also how to engage in hard discussions with people who disagree with us. We should not shirk from teaching skills for adulthood, or we risk raising unprepared children. And we can—and must—teach teens that marketing of new media is always to the benefit of the seller, not necessarily the buyer.

Yet it’s not all about parenting. The cross-generational analysis that Twenge offers is an important reminder that lives are shaped by historical shifts in culture, economy, and technology. Therefore, if we as a society truly care about human outcomes, we must carefully nurture the conditions in which the next generation can flourish.

We can’t market technologies that capture dopamine, hijack attention, and tether people to a screen, and then wonder why they are lonely and hurting. We can’t promote social movements that improve empathy, respect, and kindness toward others and then become frustrated that our kids are so sensitive. We can’t vote for politicians who stall upward mobility and then wonder why teens are not motivated. Society challenges teens and parents to improve; but can society take on the tough responsibility of making decisions with teens’ well-being in mind?

The good news is that iGens are less entitled, narcissistic, and over-confident than earlier generations, and they are ready to work hard. They are inclusive and concerned about social justice. And they are increasingly more diverse and less partisan, which means they may eventually insist on more cooperative, more just, and more egalitarian systems.

Social media will likely play a role in that revolution—if it doesn’t sink our kids with anxiety and depression first.

About the Author

Diana Divecha

Diana Divecha, Ph.D. , is a developmental psychologist, an assistant clinical professor at the Yale Child Study Center and Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, and on the advisory board of the Greater Good Science Center. Her blog is developmentalscience.com .

You May Also Enjoy

A Journey into the Teenage Brain

Why Won’t Your Teen Talk To You?

When Kindness Helps Teens (and When It Doesn’t)

When Teens Need Their Friends More Than Their Parents

When Going Along with the Crowd May be Good for Teens

Why Teens Turn from Parents to Peers

Youth have a love-hate relationship with tech in the digital age

Professor and Canada Research Chair, Young Lives, Education and Global Good, York University, Canada

Disclosure statement

Kate Tilleczek receives funding from Social Sciences and Humanities Research Foundation of Canada (SSHRC)

York University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA.

York University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

Young people are now fully ensconced in the digital age as it whirls around and within them .

This is the epoch of the Anthropocene — the age of humans, wherein a technological worldview and human tools hold the central place in re-shaping the earth and its people . It’s also a time when 1.8 billion youth make up the largest generation of 10 to 24 year olds in human history with 50 per cent of the world’s population under 30 years of age .

I have investigated the lives of young people for nearly three decades. I am interested in how young people are living today when our planet has been driven to fragility by consumption trends intimately related to the rise of mass production made possible through technologies.

Digital technologies have been too frequently adopted into schools with use and guideline policies that haven’t considered long-term environmental , health or ethical impacts: today, equity concerns have moved beyond worrying that poorer children don’t have devices to grappling with what it means if wealthy developers are raising children tech-free .

Researchers focused on the Global South have highlighted how access to technology has been driven by commercial interests and data about outcomes is generated by people who stand to profit . Those who care for youth must find new ways to determine if there are any potential benefits for youth when living immersed in digital technology — particularly because interventions to distribute more technology can compound rather than remove existing inequalities .

With my Young Lives Research Lab team based at York University, I conducted a five-year study of youth and the digital age by analyzing 185 narrative accounts we collected from young people (ages 16-24) in Canada, Australia and Scotland . From these accounts, it’s clear to me they don’t think technology is the panacea for well-being it was once argued to be .

Left to their own devices

Today, when digital surveillance is higher than ever, there is a hollowing out of learning, a shallowness that comes with abuses of privacy and surveillance and from a loss of cherished human contact .

Young people say that digital tools and ways of living are morphing beyond recognition. They live a deep modern techno-paradox and are left to their own devices (pardon the pun) to sort it out. They worry about what digital media is doing to the children they observe.

Naomi, one youth particiapant, highlighted a feeling of vulnerability:

“Most of their apps and social media apps are geared towards our age group because I feel like you can do the most … I don’t know why, it feels like they want to make us do damage. I don’t know who ‘they’ even is , but I feel like we’re just the most vulnerable crowd for them to zone in on, and for them to get as much as they possibly can out of us for their benefit.”

Earth stood still

As part of our youth study, my collaborator Ron Srigley designed and analyzed an inquiry whereby youth lived without their phones for a week. Ron’s chapter in Youth in the Digital Age: Paradox, Promise, Predicament reported the findings from this empirical inquiry.

Youth described a loss of human contact, finding more freedom and focus and having a chance to consider ethical and moral problems of living on mobile phones, apps and media. One comment was typical:

“My mom thought it was great that I did not have my phone because I paid more attention to her while she was talking.”

One youth noticed that simply walking “by strangers in the hallway or when I passed them on the street” caused almost everyone to take “out their phone right before I could gain eye contact with them.”

Several youth suggested that without the phone, they lacked the confidence to solve basic problems or feared for their safety:

“Believe it or not I had to walk up to a stranger and ask what time it was. It honestly took me a lot of guts and confidence to ask someone.” “Another thing I didn’t like about not having a cellphone that made me kind of scared at times was if someone were to attack me or kidnap me … I really wouldn’t be in any position to get help for myself …”

Youth reported a heightened awareness of a sense of acute conflict of missing instant online connection.

One person said living without their phone was “like the Earth stood still.”

Upgrades to people

In both the “no-phone experiment” and the other in-depth interviews, youth expressed both a deeply ingrained and taken-for-granted connection to their phones, while simultaneously feeling despair about a foreboding sense of technology taking over human lives .

As Easton stated:

“I think humans are going to become the new technology, and companies are going to be selling upgrades to people.”

Or, as Piper recounted:

“It’s good that technology is advancing fast because then maybe it will help some for a good cause. But also then there’s the downside of … how do you control it?”

Digital lives and wellness

Have we lost sight of the emotional, spiritual and physical well-being of youth?

Young people in our research asked that adults better attend to the myriad ways in which the digital age affects the well-being of youth. They showed how digital media affects all aspects of their lives in which well-being is measured such as health, education and social relationships .

More interesting is that they said new analyses about the depth and paradox of young digital lives is required if we are to fully understand youth wellness .

Read more: The mental health crisis among America's youth is real – and staggering

As one result of what I heard from the youth in our study, I am now involved in a global research network concerned with youth and the Anthropocene . This network is investigating what it’s like to be young now and how young people navigate wellness in this fragile time.

Researchers in this network have connected with the help of digital media — while raising concerns about the technological and capitalistic worldview from within which these tools are born.

It is time to ask whether and how societies will support youth wellness in the Anthropocene and digital age. To do this well, we must engage and listen to young people.

[ Expertise in your inbox. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter and get a digest of academic takes on today’s news, every day. ]

- Surveillance

- Digital media

- Anthropocene

- Youth mental health

- Digital lives

- young lives

- Canada youth

University Relations Manager

2024 Vice-Chancellor's Research Fellowships

Head of Research Computing & Data Solutions

Community member RANZCO Education Committee (Volunteer)

Director of STEM

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Dialogues Clin Neurosci

- v.22(2); 2020 Jun

Language: English | Spanish | French

The impact of digital technology use on adolescent well-being

El impacto del empleo de la tecnología digital en el bienestar de los adolescents, impact de l’usage des technologies numériques sur le bien-être de l’adolescent, tobias dienlin.

School of Communication, University of Hohenheim, Germany

Niklas Johannes

Institute of Neuroscience and Psychology, University of Glasgow, UK

This review provides an overview of the literature regarding digital technology use and adolescent well-being. Overall, findings imply that the general effects are on the negative end of the spectrum but very small. Effects differ depending on the type of use: whereas procrastination and passive use are related to more negative effects, social and active use are related to more positive effects. Digital technology use has stronger effects on short-term markers of hedonic well-being (eg, negative affect) than long-term measures of eudaimonic well-being (eg, life satisfaction). Although adolescents are more vulnerable, effects are comparable for both adolescents and adults. It appears that both low and excessive use are related to decreased well-being, whereas moderate use is related to increased well-being. The current research still has many limitations: High-quality studies with large-scale samples, objective measures of digital technology use, and experience sampling of well-being are missing.

Esta revisión entrega una panorámica de la literatura acerca del empleo de la tecnología digital y el bienestar de los adolescentes. En general, los resultados traducen que los efectos globales son negativos, aunque muy insignificantes. Los efectos difieren según el tipo de empleo: la procastinación y el empleo pasivo están relacionados con efectos más negativos; en cambio, el empleo social y activo se asocia con efectos más positivos. El empleo de la tecnología digital tiene efectos más potentes en los indicadores de corto plazo del bienestar hedónico (como los afectos negativos) que las mediciones a largo plazo del bienestar eudaimónico (como la satisfacción con la vida). Aunque los adolescentes son más vulnerables, los efectos son comparables para adolescentes y adultos. Parece que tanto el empleo reducido como el excesivo están relacionados con una disminución del bienestar, mientras que el empleo moderado se vincula con un mayor bienestar. La investigación actual todavía tiene muchas limitaciones: faltan estudios de alta calidad con muestras numerosas, mediciones objetivas del empleo de tecnología digital y muestras de experiencia de bienestar.

Nous proposons ici une revue de la littérature sur la pratique des technologies numériques et le bien-être de l’adolescent. Les données générales sont en faveur d’un effet négatif mais qui reste négligeable. L’usage définit la nature de l’effet : la procrastination et la passivité sont associées à un effet plus négatif alors qu’une pratique active et tournée vers la socialisation s’associe à un effet plus positif. Les effets sont plus importants sur les marqueurs à court terme du bien-être hédonique (comme les affects négatifs) que sur ceux à long terme du bien-être eudémonique (épanouissement personnel) ; ils sont comparables chez les adultes et les adolescents, même si ces derniers sont plus fragiles. Une utilisation excessive ou à l’inverse insuffisante semble diminuer le bien-être, alors qu’une pratique modérée l’augmenterait. Cependant, la recherche actuelle manque encore d’études de qualité élevée à grande échelle, de mesures objectives de la pratique des technologies numériques et d’expérience d’échantillonnage du bien-être.

With each new technology come concerns about its potential impact on (young) people’s well-being. 1 In recent years, both scholars and the public have voiced concerns about the rise of digital technology, with a focus on smartphones and social media. 2 To ascertain whether or not these concerns are justified, this review provides an overview of the literature regarding digital technology use and adolescent well-being.

Digital technology use and well-being are broad and complex concepts. To understand how technology use might affect well-being, we first define and describe both concepts. Furthermore, adolescence is a distinct stage of life. To obtain a better picture of the context in which potential effects unfold, we then examine the psychological development of adolescents. Afterward, we present current empirical findings about the relation between digital technology use and adolescent well-being. Because the empirical evidence is mixed, we then formulate six implications in order to provide some general guidelines, and end with a brief conclusion.

Digital technology use

Digital technology use is an umbrella term that encompasses various devices, services, and types of use. Most adolescent digital technology use nowadays takes place on mobile devices. 3 , 4 Offering the functions and affordances of several other media, smartphones play a pivotal role in adolescent media use and are thus considered a “metamedium.” 5 Smartphones and other digital devices can host a vast range of different services. A representative survey of teens in the US showed that the most commonly used digital services are YouTube (85%), closely followed by the social media Instagram (72%), and Snapchat (69%). Notably, there exist two different types of social media: social networking sites such as Instagram or TikTok and instant messengers such as WhatsApp or Signal.

All devices and services offer different functionalities and affordances, which result in different types of use . 6 When on social media, adolescents can chat with others, post, like, or share. Such uses are generally considered active . In contrast, adolescents can also engage in passive use, merely lurking and watching the content of others. The binary distinction between active and passive use does not yet address whether behavior is considered as procrastination or goal-directed. 7 , 8 For example, chatting with others can be considered procrastination if it means delaying work on a more important task. Observing, but not interacting with others’ content can be considered to be goal-directed if the goal is to stay up to date with the lives of friends. Finally, there is another important distinction between different types of use: whether use is social or nonsocial. 9 Social use captures all kinds of active interpersonal communication, such as chatting and texting, but also liking photos or sharing posts. Nonsocial use includes (specific types of) reading and playing, but also listening to music or watching videos.

When conceptualizing and measuring these different types of digital technology use, there are several challenges. Collapsing all digital behaviors into a single predictor of well-being will inevitably decrease precision, both conceptually and empirically. Conceptually, subsuming all these activities and types of use under one umbrella term fails to acknowledge that they serve different functions and show different effects. 10 Understanding digital technology use as a general behavior neglects the many forms such behavior can take. Therefore, when asking about the impact of digital technology use on adolescent well-being, we need to be aware that digital technology use is not a monolithic concept.

Empirically, a lack of validated measures of technology use adds to this imprecision. 11 Most work relies on self-reports of technology use. Self-reports, however, have been shown to be imprecise and of low validity because they correlate poorly with objective measures of technology use. 12 In the case of smartphones, self-reported duration of use correlated moderately, at best, with objectively logged use. 13 These findings are mirrored when comparing self-reports of general internet use with objectively measured use. 14 Taken together, in addition to losing precision by subsuming all types of technology use under one behavioral category, the measurement of this category contributes to a lack of precision. To gain precision, it is necessary that we look at effects for different types of use, ideally objectively measured.

Well-being

Well-being is a subcategory of mental health. Mental health is generally considered to consist of two parts: negative and positive mental health. 15 Negative mental health includes subclinical negative mental health, such as stress or negative affect, and psychopathology, such as depression or schizophrenia. 16 Positive mental health is a synonym for well-being; it comprises hedonic well-being and eudaimonic well-being. 17 Whereas hedonic well-being is affective, focusing on emotions, pleasure, or need satisfaction, eudaimonic well-being is cognitive, addressing meaning, self-esteem, or fulfillment.

Somewhat surprisingly, worldwide mental health problems have not increased in recent decades. 18 Similarly, levels of general life satisfaction remained stable during the last 20 years. 19 , 20 Worth noting, the increase in mental health problems that has been reported 21 could merely reflect increased awareness of psychosocial problems. 22 , 23 In other words, an increase in diagnoses might not mean an increase in psychopathology.

Which part of mental health is the most likely to be affected by digital technology use? Empirically, eudaimonic well-being, such as life satisfaction, is stable. Although some researchers maintain that 40% of happiness is volatile and therefore malleable, 24 more recent investigations argued that the influences of potentially stabilizing factors such as genes and life circumstances are substantially larger. 25 These results are aligned with the so-called set-point hypothesis, which posits that life satisfaction varies around a fixed level, showing much interpersonal but little intrapersonal variance. 26 The hypothesis has repeatedly found support in empirical studies, which demonstrate the stability of life satisfaction measures. 27 , 28 Consequently, digital technology use is not likely to be a strong predictor of eudaimonic well-being. In contrast, hedonic well-being such as positive and negative affect is volatile and subject to substantial fluctuations. 17 Therefore, digital technology use might well be a driver of hedonic well-being: Watching entertaining content can make us laugh and raise our spirits, while reading hostile comments makes us angry and causes bad mood. In sum, life satisfaction is stable, and technology use is more likely to affect temporary measures of hedonic well-being instead of more robust eudaimonic well-being. If this is the case, we should expect small to medium-sized effects on short-term affect, but small to negligible effects on both long-term affect and life satisfaction.

Adolescents

Adolescence is defined as “the time between puberty and adult independence,” 29 during which adolescents actively develop their personalities. Compared with adults, adolescents are more open-minded, more social-oriented, less agreeable, and less conscientious 30 ; more impulsive and less capable of inhibiting behavior 31 ; more risk-taking and sensation seeking 29 ; and derive larger parts of their well-being and life satisfaction from other peers. 32 During adolescence, general levels of life satisfaction and self-esteem drop and are often at their all-time lowest. 33 , 34 At the same time, media use increases and reaches a first peak in late adolescence. 3 Analyzing the development of several well-being-related variables across the last two decades, the answers of 46 817 European adolescents and young adults show that, whereas overall internet use has risen strongly, both life satisfaction and health problems remained stable. 19 Hence, although adolescence is a critical life stage with substantial intrapersonal fluctuations related to well-being, the current generation does not seem to do better or worse than those before.

Does adolescent development make them particularly susceptible to the influence of digital technology? Several scholars argue that combining the naturally occurring trends of low self-esteem, a spike in technology use, and higher suggestibility into a causal narrative can take the form of a foregone conclusion. 35 For one, although adolescents are in a phase of development, there might be more similarities between adolescents and adults than differences. 30 Concerns about the effects of a new technology on an allegedly vulnerable group has historically often taken the form of paternalization. 36 For example, and maybe in contrast to popular opinion, adolescents already possess much media literacy or privacy literacy. 3

This has two implications. First, asking what technology does to adolescents ascribes an unduly passive role to adolescents, putting them in the place of simply responding to technology stimuli. Recent theoretical developments challenge such a one-directional perspective and advise to rather ask what adolescents do with digital technology , including their type of use. 37 Second, in order to understand the effects of digital technology use on well-being, it might not be necessary to focus on adolescents. It is likely that similar effects can be found for both adolescents and adults. True, in light of the generally decreased life satisfaction and the generally increased suggestibility, results might be more pronounced for adolescents; however, it seems implausible that they are fundamentally different. When assessing how technology might affect adolescents compared with adults, we can think of adolescents as “canaries in the coalmine.” 38 If digital technology is indeed harmful, it will affect people from all ages, but adolescents are potentially more vulnerable.

Effects

What is the effect of digital technology use on well-being? If we ask US adolescents directly, 31% are of the opinion that the effects are mostly positive, 45% estimate the effects to be neither positive nor negative, and 24% believe that effects are mostly negative. 4 Teens who considered the effects to be positive stated that social media help (i) connect with friend; (ii) obtain information; and (c) find like-minded people. 4 Those who considered the effects to be negative explained that social media increase the risks of (i) bullying; (ii) neglecting face-to-face contacts; (iii) obtaining unrealistic impressions of other people’s lives. 4

Myriad studies lend empirical support to adolescents’ mixed feelings, reporting a wide range of positive, 39 neutral, 40 or negative 41 relations between specific measures of digital technology use and well-being. Aligned with these mixed results of individual studies, several meta-analyses support the lack of a clear effect. 42 In an analysis of 43 studies on the effects of online technology use on adolescent mental well-being, Best et al 43 found that “[t]he majority of studies reported either mixed or no effect(s) of online social technologies on adolescent wellbeing.” Analyzing eleven studies on the relation between social media use and depressive symptoms, McCrae et al 44 report a small positive relationship. Similarly, Lissak 45 reports positive relations between excessive screen time and insufficient sleep, physiological stress, mind wandering, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)-related behavior, nonadaptive/negative thinking styles, decreased life satisfaction, and potential health risks in adulthood. On the basis of 12 articles, Wu et al 46 find that “the use of [i]nternet technology leads to an increased sense of connectedness to friend[s] and school, while at the same time increasing levels of anxiety and loneliness among adolescents.” Relatedly, meta-analyses on the relation between social media use and adolescent academic performance find no or negligible effects. 47

It is important to note that the overall quality of the literature these meta-analyses rely upon has been criticized. 48 This is problematic because low quality of individual studies biases meta-analyses. 49 To achieve higher quality, scholars have called for more large-scale studies using longitudinal designs, objective measures of digital technology use that differentiate types of use, experience sampling measures of well-being (ie, in-the-moment measures of well-being; also known as ambulant assessment or in situ assessment), and a statistical separation of between-person variance and within-person variance. 50 In addition, much research cannot be reproduced because the data and the analysis scripts are not shared. 51 In what follows, we look at studies that implemented some of these suggestions.

Longitudinal studies generally find a complex pattern of effects. In an 8 year study of 500 adolescents in the US, time spent on social media was positively related to anxiety and depression on the between-person level. 52 At the within-person level, these relationships disappeared. The study concludes that those who use social media more often might also be those with lower mental health; however, there does not seem to be a causal link between the two. A study on 1157 Croatians in late adolescence supports these findings. Over a period of 3 years, changes in social media use and life satisfaction were unrelated, speaking to the stability of life satisfaction. 40 In a sample of 1749 Australian adolescents, Houghton et al 53 distinguished between screen activities (eg, web browsing or gaming) and found overall low within-person relations between total screen time and depressive symptoms. Out of all activities, only web surfing was a significant within-person predictor of depressive symptoms. However, the authors argue that this effect might not survive corrections for multiple testing. Combining a longitudinal design with experience sampling in a sample of 388 US adolescents, Jensen et al 54 did not find a between-person association between baseline technology use and mental health. Interestingly, they only observed few and small within-person effects. Heffer et al 55 found no relation between screen use and depressive symptoms in 594 Canadian adolescents over 2 years. These results emphasize the growing need for more robust and transparent methods and analysis. In large adolescent samples from the UK and the US, a specification curve analysis, which provides an overview of many different plausible analyses, found small, negligible relations between screen use and well-being, both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. 56 Employing a similar analytical approach, Orben, Dienlin, and Przybylski 57 found small negative between-person relations between social media use and life satisfaction in a large UK sample of adolescents over 7 years. However, there was no robust within-person effect. Similarly, negligible effect sizes between adolescent screen use and well-being are found in cross-sectional data sets representative of the population in the UK and US. 58 In analyzing the potential effects of social media abstinence on well-being, two large-scale studies using adult samples found small positive effects of abstinence on well-being. 59 , 60 Two studies with smaller and mostly student samples instead found mixed 61 or no effects of abstinence on well-being. 62

The aforementioned studies often relied on composite measures of screen use, possibly explaining the overall small effects. In contrast, work distinguishing between different types of use shows that active use likely has different effects than passive use. Specifically, active use may contribute to making meaningful social connections, whereas passive use does not. 9 For example, meaningful social interactions have been shown to increase social gratification in adults, 63 , 64 whereas passive media use or media use as procrastination has been negatively related to well-being. 6 , 8 This distinction should also apply to adolescents. 6 The first evidence for this proposition already exists. In a large sample of Icelandic adolescents, passive social media use was positively related to anxiety and depressive symptoms; the opposite was the case for active use. 65

Furthermore, longitudinal work so far relies on self-reports of media use. Self-reported media use has been shown to be inaccurate compared with objectively measured use. 14 Unfortunately, there is little work employing objective measures to test whether the results of longitudinal studies using self-reports hold up when objective use is examined. The limited existing evidence suggests that effects remain small. In a convenience sample of adults, only phone use at night negatively predicted well-being. 66 Another study that combined objective measures of social smartphone applications with experience sampling in young adults found a weak negative relation between objective use and well-being. 67

Effects might also not be linear. Whereas both low and high levels of internet use have been shown to be associated with slightly decreased life satisfaction, moderate use has been shown to be related to slightly increased life satisfaction. 10 , 35 , 68 However, evidence for this position is mixed; other empirical studies did not find this pattern of effects. 53 , 54

Taken together, do the positive or the negative effects prevail? The literature implies that the relationship between technology use and adolescent well-being is more complicated than an overall negative linear effect. In line with meta-analyses on adults, effects of digital technology use in general are mostly neutral to small. In their meta-review of 34 meta-analyses and systematic reviews, Meier and Reinecke 42 summarize that “[f]indings suggest an overall (very) small negative association between using SNS [social networking sites], the most researched CMC [computer mediated communication] application, and mental health.” In conclusion, the current literature is mostly ambivalent, although slightly emphasizing the negative effects of digital tech use.

Implications

Although there are several conflicting positions and research findings, some general implications emerge:

1. The general effects of digital technology use on well-being are likely in the negative spectrum, but very small—potentially too small to matter.

2. No screen time is created equal; different uses will lead to different effects.

3. Digital technology use is more likely to affect short-term positive or negative affect than long-term life satisfaction.

4. The dose makes the poison; it appears that both low and excessive use are related to decreased well-being, whereas moderate use is related to increased well-being.

5. Adolescents are likely more vulnerable to effects of digital technology use on well-being, but it is important not to patronize adolescents—effects are comparable and adolescents not powerless.

6. The current empirical research has several limitations: high-quality studies with large-scale samples, objective measures of digital technology use, and experience sampling of well-being are still missing.

Conclusion

Despite almost 30 years of research on digital technology, there is still no coherent empirical evidence as to whether digital technology hampers or fosters well-being. Most likely, general effects are small at best and probably in the negative spectrum. As soon as we take other factors into account, this conclusion does not hold up. Active use that aims to establish meaningful social connections can have positive effects. Passive use likely has negative effects. Both might follow a nonlinear trend. However, research showing causal effects of general digital technology use on well-being is scarce. In light of these limitations, several scholars argue that technology use has a mediating role69: already existing problems increase maladapted technology use, which then decreases life satisfaction. Extreme digital technology use is more likely to be a symptom of an underlying sociopsychological problem than vice versa. In sum, when assessing the effects of technology use on adolescent well-being, one of the best answers is that it’s complicated.

This lack of evidence is not surprising, because there is no consensus on central definitions, measures, and methods. 42 Specifically, digital technology use is an umbrella term that encompasses many different behaviors. Furthermore, it is theoretically unclear as to why adolescents in particular should be susceptible to the effects of technology and what forms of well-being are candidates for effects. At the same time, little research adopts longitudinal designs, differentiates different types of technology use, or measures technology use objectively. Much work in the field has also been criticized for a lack of transparency and rigor. 51 Last, research (including this review) is strongly biased toward a Western perspective. In other cultures, adolescents use markedly different services (such as WeChat or Renren, etc). Although we assume most effects to be comparable, problems seem to differ somewhat. For example, online gaming addiction is more prevalent in Asian than Western cultures. 70

Adults have always criticized the younger generation, and media (novels, rock music, comic books, or computer games) have often been one of the culprits. 1 Media panics are cyclical, and we should refrain from simply blaming the unknown and the novel. 1 In view of the public debate, we should rather emphasize that digital technology is not good or bad per se. Digital technology does not “happen” to individuals. Individuals, instead, actively use technology, often with much competence. 3 The current evidence suggests that typical digital technology use will not harm a typical adolescent. That is not to say there are no individual cases and scenarios in which effects might be negative and large. Let’s be wary, but not alarmist.

Acknowledgments

Both authors declare no conflicts of interest. Both authors contributed equally to this manuscript. Tobias Dienlin receives funding from the Volkswagen Foundation. We would like to thank Amy Orben for valuable feedback and comments

Gen Z and tech dependency: How the youngest generation interacts differently with the digital world

The term “tech-savvy” conjures images of young digital savants effortlessly manipulating technology in ways that people from older generations often struggle to emulate. This perception can exacerbate generational divides. With so much of our personal and professional worlds now inextricably tied to digital technology, Gen X and especially Baby Boomers can feel frustrated and intimidated by the idea of younger generations mastering complex modern technology with such ease — and usually while walking (or, unfortunately, driving!).

Are Gen Z really a generation of digital wizards, able to intuitively navigate code, design motion graphics, and maintain server infrastructure? Not quite.

CGK research on Gen Z points to a different phenomenon: Tech dependency. Gen Z lives and breathes the digital world. Social media, information saturation, and rapid advances in physical technology have assimilated into the Gen Z psyche in a fundamentally unique way. Leaders in the workplace and marketplace can use this knowledge to help Gen Z as employees, unlock their potential as customers, and increase trust across generations.

Digital natives and internet attachment

Gen Z are true digital natives. Our State of Gen Z research studies show that 95% own a smartphone, 83% own a laptop, 78% own an advanced gaming console, and 57% have a desktop computer. 29% use their smartphone past midnight on a nightly basis.

They thrive in this environment, but they also show signs of dependency. 69% become uncomfortable after being away from internet access for more than eight hours — and 27% can only last one hour! Engaging with online communities and absorbing digital information has become second nature to Gen Z, and severing that connection can cause distress.

The internet is Gen Z’s evergreen wellspring for entertainment, too. As our previous research shows, 73% of Boomers, 69% of Gen Z, and 59% of Millennials report using the internet primarily to access information, 72% of Gen Z access the internet mainly for entertainment: videos, apps, message boards, etc.

The attachment also extends to communication and interpersonal fulfillment. 51% of Gen Z report daily dependence on the internet for access to other people and connections. They consider themselves members in an amalgam of distinct digital communities, with friendships and even reputations to maintain—60% of Gen Z believe online reputations will be the primary determinant of their dating options in the near future.

Tech dependency is complex

This doesn’t mean Gen Z can’t be parted from their smartphones for any reason. Just 22% of Gen Z report feeling stress if they aren’t allowed to use or look at their phones while at work. This could be interpreted as Gen Z continuing to develop their preferred communication channels and expectations.

In addition to tech expectations, Gen Z’s tech dependency also cultivates an instinct for digital authenticity that should be a benefit as they become adults and trendsetters. 48% say they want a standardized form of authentication from every person they meet online so they can trust that a person isn’t misrepresenting themselves. They are also 25% more likely than Boomers and Gen X to self-select into digital worlds where websites and apps track user data and run interference on bad actors.

Leaders have a unique opportunity to understand, adapt, and leverage Gen Z’s tech dependency in ways that benefit both Gen Z and the companies that employ and sell to them. Recognizing this new mode of interacting with technology as a paradigm shift—and not merely the latest fad or PokemonGo—will help leaders better connect generations in the workplace and beyond.

At CGK, we help leaders understand how to leverage technology across generations to drive trust, innovation, and teamwork. Reach out to us today to see how we can be a resource through speaking, research, or consulting. We look forward to hearing from you–in whatever tech way you prefer to use!

Posted: November 14th, 2019

Categories: Gen Z | Research | Technology

Written by Jason Dorsey

Jason Dorsey is an acclaimed generations and behavioral researcher and speaker. He's received over 1,000 standing ovations for his unique keynote presentations. Jason has led over 120 research studies. Adweek calls him a "research guru." His mission is to deliver new insights and practical strategies that solve business challenges for leaders.

You may also be interested in —

Jason Dorsey Shares His Top 10 Favorite Memories of 2023

Working Closely with Atlas Holdings’ HR Leaders

Keynoting FINRA’s Annual Conference in Washington D.C.!

Subscribe to jason's email newsletter.

The Technology Influence on Youth Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Today, the importance of technology makes many people prefer to scroll through the timeline rather than get a few hours of sleep. Teenagers who are deprived of controlling their free time or filtering information coming from social networks are especially susceptible to this. Absorbing all the information that the Internet introduces, teenagers tend to stop evaluating the acquired knowledge sensibly. This leads to a deterioration of mental state physical health and increases the risk of falling into the hands of fraudsters. Since the spread of the Internet provides easier access to extensive knowledge and carries hidden harm, research has been conducted to analyze the impact of the Internet on adolescents. These studies were aimed at identifying the dangers that teenagers face on the Internet, finding their causes and measures that can help overcome them. This paper examines some of the main effects of new technologies on adolescents and young people, including deterioration of the physical and mental condition, increased risk of becoming a victim of a fraudster, and the gradual loss of moral values in an entire generation.

The interest of young people in social networks has specific consequences in the form of mental and physical health problems. For example, sitting in a constantly uncomfortable posture while checking social networks leads to the deterioration of the neck and back, provoking chronic pain in these areas. Moreover, bright light contributes to the damage of vision and sleep disorders, such as lack of sleep or even insomnia. Online interactions affect a teen’s emotional state, which can never be restored when it comes to mental health. Adolescents have learned to interact with people while staying behind the curve, which disrupts communication abilities (Bibi et al. 480). This proves that when technology is used incorrectly, it harms comprehensively.

The use of social networks by young people also weakens the institution of moral education and disregard for moral values. Uncontrolled publications on the social network Instagram with a demonstration of tobacco or the smoking process lead to the popularization of smoking among teenagers. Another problem is the distribution of images with alcohol consumption in the same social network, which erases the boundaries of what is permissible for minors. In addition, the lack of filtering of images of aggression and cruelty also leads to an increase in the risks of immoral behavior among adolescents whose personality has not yet been fully formed (Krylova 498). Having a negative impact on teenagers’ vision of tobacco and alcohol, technologies, where not all information is filtered and suitable for children and adolescents, also harm moral values.

The growing popularity of technology among young people has also led to an increase in their involvement in the sex industry, leading to a rise in crime and the experience of traumatic experiences by adolescents. Viewing prohibited materials causes the appearance of curiosity, which means the risk of harmful sexual contact even with the right person is becoming possible. New technologies and poor awareness of teenagers have also led to an increased risk of sharing an intimate photo on the Internet with an unfamiliar person. The possibility of involving children in the porn industry is also greatly simplified, which sometimes happens by the voluntary consent of a teenager due to the influence of the availability of sexual content (Senadjki et al. 63). As a result, the number of sexual crimes, where the victims are teenagers, is increasing because of the lack of filtering information in social networks.

From all of the above, it follows that the Internet has a huge negative impact of unverified information on the still unformed personalities of teenagers. All this leads to the understanding that the quantity and quality of resources viewed by teenagers must be controlled. Moreover, it is worth raising awareness among young people about the dangers and risks that await them with excessive use of technology.

Works Cited

Bibi, Arifa, et al. “Effect of Latest Technology and Social Media on Interpersonal Communication on Youth of Balochistan.” Journal of Managerial Sciences , vol. 11, n. 3, 2018, pp. 475-490.

Krylova, Palageya. “The Impact of the Social Networks Having Name Instagram on Values of Youth.” Culture and Education: Social Transformations and Multicultural Communication, 2019, pp. 494-501

Senadjki, Abdelhak, et al. “The Influence of Technology on Youth Sexual Prevalence: Evidences from Malaysia.” Malaysian Journal of Youth Studies, 2017, pp. 38-68.

- Trends in Embedded Systems

- Analyzing the iPhone as an Artifact

- Computer Literacy: Parents and Guardians Role

- Tobacco Smoking and Its Dangers

- Kinds of IP-Servers and Their Characteristics

- Smartwatches: Developments of Niche Devices

- Human Impact on Technology: Ethics for the Information Age

- COVID-19 Pandemic in Singapore

- Future Innovations and Their Role in People’s Life

- Science and Technology: Impact on Human Life

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, January 11). The Technology Influence on Youth. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-technology-influence-on-youth/

"The Technology Influence on Youth." IvyPanda , 11 Jan. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/the-technology-influence-on-youth/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'The Technology Influence on Youth'. 11 January.

IvyPanda . 2023. "The Technology Influence on Youth." January 11, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-technology-influence-on-youth/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Technology Influence on Youth." January 11, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-technology-influence-on-youth/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Technology Influence on Youth." January 11, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-technology-influence-on-youth/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

- Research Article

- Open access

- Published: 03 April 2022

Young people’s technological images of the future: implications for science and technology education

- Tapio Rasa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1315-5207 1 &

- Antti Laherto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5062-7571 2

European Journal of Futures Research volume 10 , Article number: 4 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

16 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

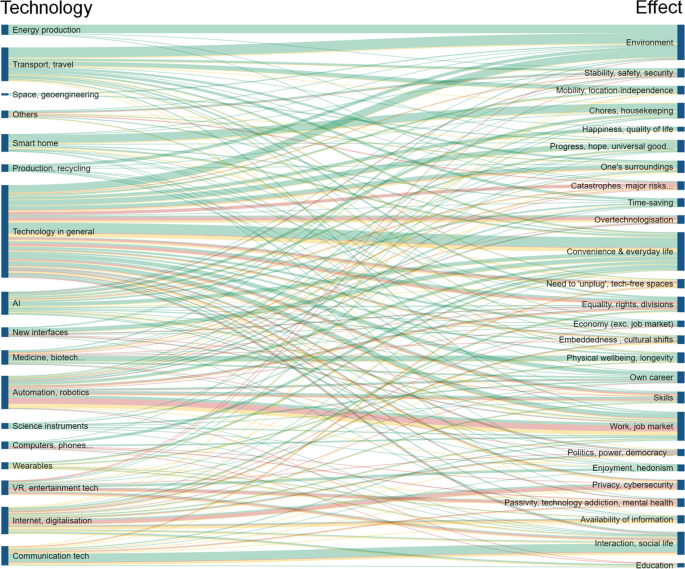

Modern technology has had and continues to have various impacts on societies and human life in general. While technology in some ways defines the ‘digital age’ of today, discourses of ‘technological progress’ may dominate discussions of tomorrow. Conceptions of technology and futures seem to be intertwined, as technology has been predicted by experts to lead us anywhere between utopia and extinction within as little as a century. Understandably, hopes and fears regarding technology may also dominate images of the future for our current generation of young people. Meanwhile, global trends in science and technology education have increasingly emphasised goals such as agency, anticipation and active citizenship. As one’s agency is connected to one’s future perceptions, young people’s views of technological change are highly relevant to these educational goals. However, students’ images of technological futures have not yet been used to inform the development of science and technology education. We set out to address this issue by investigating 58 secondary school students’ essays describing a typical day in 2035 or 2040, focusing on technological surroundings. Qualitative content analysis showed that students’ images of the future feature technological changes ranging from improved everyday devices to large-scale technologisation. A variety of effects was attributed to technology, relating to convenience, environment, employment, privacy, general societal progress and more. Technology was discussed both in positive and negative terms, as imagined technological futures were problematised to differing extents. We conclude by discussing the potential implications of the results for the development of future-oriented science and technology education.

Introduction

Modern technology has had and continues to have an impact on human life and civilisation that is hard to overstate. While technology in some ways defines the ‘digital age’ of today, discourses of ‘technological progress’ may dominate discussions of tomorrow. Meanwhile, predicting the ‘real future’ and figuring out how to do it well is a field in itself, and experts within and outside specific technological fields project a wide range of predictions for the coming decades: technology has been predicted to lead us anywhere between human extinction [ 10 ] and planet-sized self-aware computers [ 32 ] within the timescale of a century, with more cautious predictions forecasting a ‘third industrial revolution’ by 2030 ([ 16 ], p. 33). Understandably, hopes and fears regarding technology may also dominate the images of the future for our current generation of young people (see, e.g. [ 3 , 36 ]).

Obviously, the fact that developments in science and technology can have great desirable and undesirable societal implications is reflected in science education. This element is central to research currents such as STSE (science, technology, society, environment—see, e.g. [ 6 ]), SSI (socioscientific issues—e.g. [ 49 ]) and the various visions of scientific literacy (e.g. [ 45 ]). Interestingly, however, these socioscientific leanings rarely address explicitly the temporal aspects of socioscientific thinking. Thus, even if local and global SSIs ‘are all related to important aspects of our future’ ([ 44 ], pp. 2–3) and environmental education should address ‘Where do we want to go?—knowledge about alternatives and visions’ ([ 28 ], p. 331), the connection to futures thinking is often unaddressed when contextualising science as societally relevant. For example, the focus of STSE has been applying science and technology in social (more or less real-world) contexts, understanding the sociocultural embeddedness of such activity and exploring holistic, value-centred approaches to evaluating technoscientific issues [ 39 ]. These aspects of scientific literacy certainly have a ‘time component’, but seem to lack a more nuanced relationship with futures. This oversight seems to reflect a general pattern in education (see, e.g. [ 24 ]).

Understandably this ‘blind spot’ has been criticised in the futures field: according to Gidley & Hampson [ 22 ],

[s]chool education seems to be mostly stuck in an outdated industrial era worldview, unable to sufficiently address the significance and increasing rapidity of changes to humanity that are upon us. An integrated forward-looking view should, now more than ever, be of central importance in how we educate. Yet there is little sign that – unlike corporations – school systems are recognising the true value of futures studies.

While the field of science education has seen some recent initiatives for developing students’ futures thinking [ 29 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 41 ], much work remains to be done in communicating between the two fields. One approach to strengthening the foothold of futures thinking in schools may be identifying practical contexts for future-oriented education and joining with natural ‘allies’ within the range of educational fields [ 23 ], or formalising the concept of ‘futures literacy’ in education, eliciting students’ images of the future, and supporting their agency [ 24 ]. A further goal may be formalising relevant capacities to also enable evaluation of learning processes and outcomes, where constructions such as ‘futures consciousness’ [ 1 ] may prove useful.

Meanwhile, young people’s future thinking has been analysed in several studies (e.g. [ 3 , 15 , 43 ]), revealing both pessimistic and optimistic future outlooks. Such studies also support the notion that technology is strongly associated with imagined future worlds—a connection embodied in science fiction, which arguably could also be called ‘technology fiction’ or ‘future fiction’, demonstrating a strong association between the concepts. Within futures studies, this link may seem obvious (see, e.g. the role of technology in the ‘future archetypes’ of [ 27 ]), but it is underrepresented in science education literature; students’ hopes, fears and expectations regarding the future are rarely addressed.

There may also exist a discontinuity between the approaches taken when addressing socioscientific thinking within education, and those taken when studying young people’s perceptions of the future. Namely, societally oriented science education research and practice may tend to be based on individual issues [ 6 ] and case studies, while research on young people’s perceptions of technology may look at technology more generally [ 7 ].

Thus our goal in this paper is to explore the following question:

What kinds of technology and what desirable and undesirable impacts of technology are present in upper-secondary school students’ images of the future?

Specifically, we examine a set of Finnish upper secondary school students’ essays that describe imagined future worlds, set in years 2035 and 2040. We analyse what technologies are present in these essays, what aspects of the world and human life are affected by technology and whether these effects are framed as positive, negative or in neutral or conflicted terms.

Our goal is to diversify the meaning of the term ‘technology’ in (young) people’s futures thinking by providing an exploratory study on expectations, hopes and fears associated with specific envisioned technological developments or the processes of technologisation in general. Finally, we conclude by discussing potential implications of the results for the development of science and technology education, and the potential of using socioscientific and sociotechnical issues as a context for futures thinking in education.

Definitions and rationale

In this paper, we examine the role of technology in upper-secondary school students’ images of the future. By images of the future we mean ‘snapshots of the major features of interest at various points in time’ ([ 42 ], p. 14). Images of the future do not necessarily contain ‘an account of the flow of events leading to such future conditions’ (Ibid., p. 14); this temporal perspective would turn an image into a scenario (which are more commonly explored in futures studies and also in future-oriented science education—see, e.g. [ 35 ]).

Images of the future are widely addressed in futures studies. However, as they exist in people’s imaginations and are by nature complex, they are difficult to fully pin down. Perceptions about the future are an integral part of one’s worldview [ 36 ], and at least in the case of nonexpert futures thinking, they can be expected to lack some systematicity. Imagined futures are often inconsistent [ 30 ] and can perhaps be better understood as reflecting the present [ 9 ]. An example of inconsistency is the common finding of a disconnection between optimistic personal and gloomy global futures [ 15 , 43 , 47 ].

In the case of images of technological futures, one’s understanding of technology is naturally a component, but only one of many. To quote Zeidler et al. [ 49 ], p. 360, ‘knowledge and understanding of the interconnections among science, technology, society, and the environment (...) do not exist independently of students’ personal beliefs’. For our purposes, no attempt to separate these components is necessary: our goal is to give voice to the image that emerges from these influences.

Defining technology is something of an arduous task, partly because the meaning of the word seems to vary greatly between contexts—it is a ‘slippery term’ ([ 5 ], p. 7). Thus for example the ‘T’ of STS (Science and technology studies) may be different from the ‘T’ of STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics). The students who wrote the essays that form the dataset for our study were asked to address the role of technology in their image of the future, and no theoretical definition was provided with this prompt. We expect students to have relied on some commonsense meaning of the word, and for the purposes of our study, we consider technology to be related to artefacts, tools, methods and systems that are based on the application of knowledge specific to STEM subjects. We expect this meaning to correspond to some extent with students’ thinking.

This study uses a unified view of science and technology education, or scientific and technological literacy (see, e.g. [ 33 ]) that is typical in current trends of interdisciplinary and societally oriented science education, or STEM education (see, e.g. [ 12 ]). As a clarification, we do not wish to convey the idea that the relationship between science and technology is obvious and uncomplicated (see, e.g. [ 4 ]). However, this is a context-dependent issue: firstly, technology experts and technologically literate citizens are expected to gain much of their education within science education, and secondly, the boundary between science and technology tends to disappear (or lose some of its meaning) in societal and future-oriented contexts [ 26 ]. Thus, studies of students’ images of technological futures can be expected to provide insight into the expectations, opportunities and sociotechnical thinking that will eventually be reflected in both the practice of technology experts and the actions of nonexpert citizens [ 31 ].

Perceptions of (technological) futures

Research on young people’s futures thinking has shown that science and technology are typical ingredients in young people’s dystopian views [ 13 ] but also central to their hopes of sustainable or otherwise progressive futures [ 15 , 36 ]. According to Cook ([ 15 ], p. 528), young people may generally feel ‘a loss of faith in the notion that humanity is progressing towards a positive future’—and thus society is ‘due for another break through’ with the help of technology.