How to resolve group work challenges and issues in the classroom

With its focus on collaboration , group work has great potential to enhance learning. Not only does it bring students together to share ideas and experience different perspectives, but it can also equip them with real-world skills like problem-solving and teamwork.

However, group work is not without its share of obstacles! And sometimes, collaborative activities don’t go quite as planned. Let’s look at some approaches to overcoming common hurdles in group work and how Kialo Edu can help.

What are some common issues in group work, and how can teachers help address them?

Problem #1: Lack of enthusiasm for group work

What should teachers do when students don’t seem to like group work.

This common issue can put a dampener on an activity before it even starts. But let’s be honest, it’s understandable! Identifying why students feel this way can help teachers decide on the best tactics to address it.

Student complaint #1: “I’ve had negative experiences with group work in the past.”

Solution: Identify their concerns and work from there

Show students that you are receptive and responsive to their hesitation. An anonymous questionnaire on group work for older students can give them the space to air their concerns while giving their teacher context to work from.

Depending on student responses, teachers can spend some time troubleshooting difficult dynamics, encouraging students to come up with group expectations. Or, teachers can structure tasks to ensure an equitable balance of responsibilities.

Student complaint #2: “Some people do nothing and get the credit anyway!”

Solution: Give structured group tasks and assignments to ensure students share the load

Group members coasting is a salient issue. And for good reason. It’s natural to be irritated if you feel you are always picking up the slack!

Giving structured tasks that promote positive interdependence in small groups can put a spotlight on individual accountability, making it difficult for students to take a back seat.

Similarly, group grades can feel unfair due to variations in individual effort. Address this by requiring each student to submit a piece of work, such as a report or personal reflection. If groups are learning new content together, consider including an individual assessment at the end of the unit.

Student complaint #3: “I don’t see the value in group work — I prefer to work alone.”

Solution: Communicate clearly the skills and benefits students will develop with group work

Students may not see the pedagogical benefits of collaboration and active learning like their teacher does. Outlining the ways group activities can help them prepare for their future goals outside academia can ground it in the practical and the personal.

Group work can also be combined with individual work to give students the best of both worlds! Giving students time to process the material individually before asking them to explain it to peers can lead to deeper learning as it requires information retrieval and elaboration .

Problem #2: Lack of collaboration

What should teachers do when students aren’t actually working together on a group project?

You’ve put students in groups and given clear instructions, but they don’t seem to be interacting or getting fully into the task. There may be a number of reasons for this.

Issue #1: Students don’t feel comfortable enough with each other yet

Solution: Work to build a sense of community in the classroom

By cultivating a classroom community, teachers can help students feel more connected to each other and their group tasks. Use icebreakers and practice group activities to ease into the goals of communication and collaboration before expecting students to dive into more curriculum-specific projects.

This is particularly important if students are learning remotely as there’s a lack of natural interactions to forge relationships that come from a shared physical learning space.

Issue #2: Students don’t have the skills to effectively work as a group

Solution: Give explicit instructions while giving support as a facilitator

Teamwork is a learned skill. Expecting students to know how to work effectively together is often unrealistic since it depends on their previous experiences.

If you know your students have underdeveloped teamwork skills, give them explicit instruction in collaboration, communication, and project management skills while taking on a more active role as facilitator. This may mean assigning roles as necessary and having regular check-in points. For longer-term group projects, guide students to set time-specific goals to keep them on track.

Issue #3: Students aren’t actually working together

Solution: Design problem-solving tasks that require whole-group participation

Perhaps students are working individually or dividing tasks up so they can finish the project quicker. While this might work well for some intended cooperative group activities , it’s ideal for all group members to engage with all the content.

In this case, assign more complex and authentic tasks that require the whole group, rather than individuals, to solve. Try bringing in problem-solving activities with different pathways to the solution or case studies to stretch students’ creativity.

Problem #3: Lack of progress

What should teachers do if groups aren’t making progress on their projects.

It may be true that two (or more) heads are better than one, but groups can also run into stumbling blocks.

Issue #1: Students are struggling to find time to work together

Solution: Dedicate in-class time for group work

Students of all age groups have many time commitments, and asking them to work together outside school hours can be tricky! Help them out by giving time in class for some of their work and coordination, and make use of technology that allows them to collaborate virtually. If older students need to be together to complete their group tasks, take their schedules into consideration when assigning groups.

Issue #2: Group decisions lack focus

Solution: Provide space for teacher and peer feedback

So you’ve given students clear instructions and objectives, but they are struggling and talking themselves in circles. Some extra input from their teacher and peers can often get them back on track.

Activities such as “three-stay one-stray” can give groups a fresh set of eyes and a peek at what other groups are doing. In this technique, one group member rotates out to another group to learn about their approach, while the rest stay and explain what they’re doing to a member from another group. Repeat for a couple of rotations before students return to their original group to debrief and reassess their own task.

Problem #4: Group dynamic problems that hinder collaboration

What should teachers do when groups aren’t working well together.

Working with other people brings many personalities together while working with peers can bring its own pressures. This can get in the way of progress as well as relationships between students!

Issue #1: Participation is skewed by more dominant or passive students

Solution: Establish group norms and structure through assigned roles

Start by keeping groups small to about four participants to encourage more balanced participation and establish group norms in advance in collaboration with students. Teachers can also provide structure for those students less comfortable in group dynamics by assigning meaningful roles , such as questioner or skeptic.

Teachers can also give everyone a chance to speak (or listen) by adding small exercises to open up group interactions. Pause at an appropriate time for individual reflection on the task to give students a chance to gather their thoughts and identify anything they want to add. Or, ask each group to go in a circle, with each member taking a turn to share their ideas in a round-robin format.

Issue #2: Students are all just agreeing with each other!

Solution: Give space and time for individual brainstorming

It can be difficult to disagree with your peers but easy for a group to decide on a single idea to focus on! Prompt students to generate new ideas by asking them to do some individual brainstorming before moving into their groups, or at intervals during a group task. Teachers can also set up tasks that require students to explore different sides of a topic before coming to a conclusion.

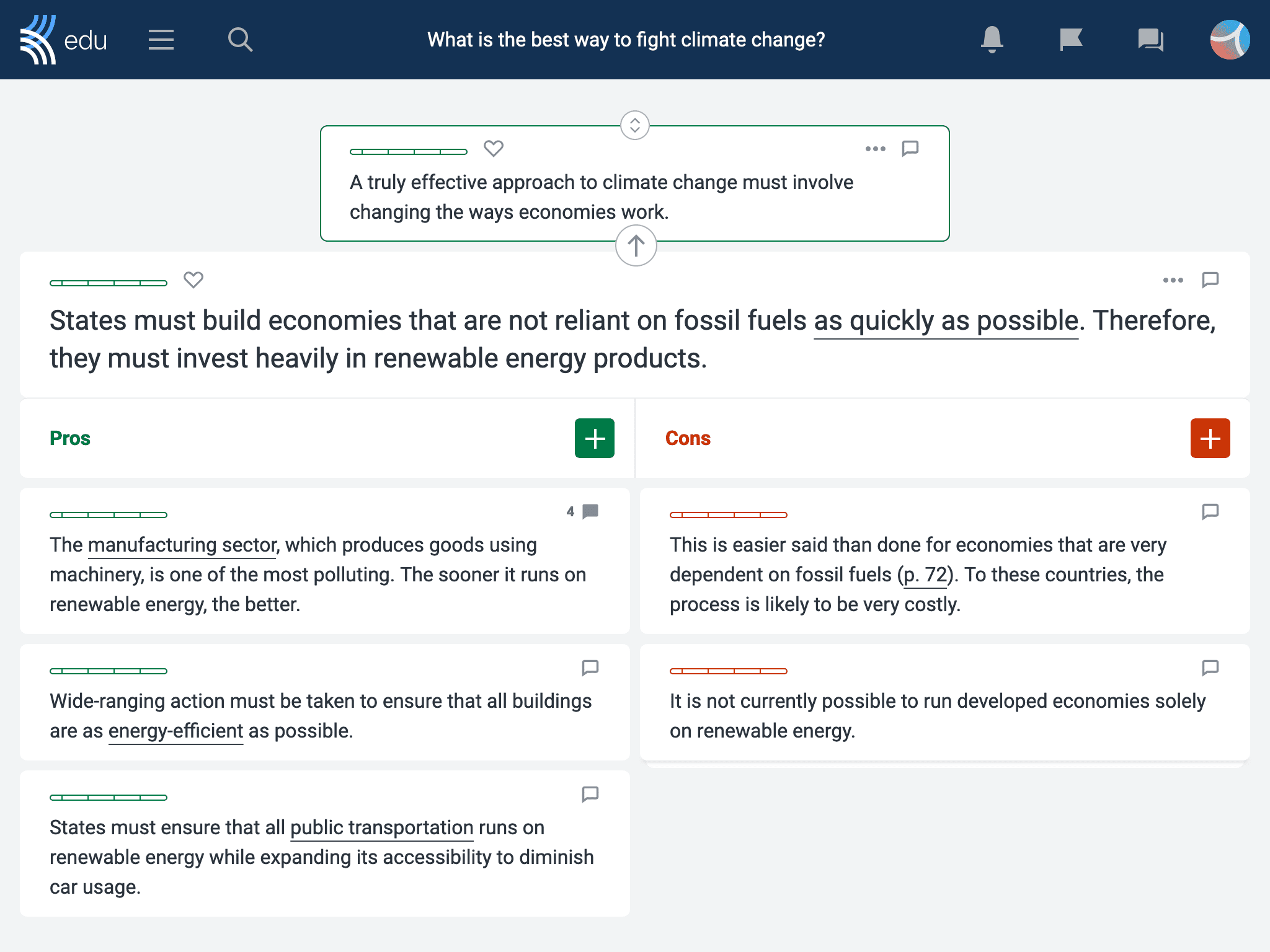

How to support effective group work with Kialo Edu

You can use Kialo Edu discussions to support effective group work, both inside and outside the classroom. Because they were designed with collaboration in mind, Kialo discussions give all students a voice while gently challenging their ideas by exposing them to their classmates’ perspectives.

These discussions can also serve as the tangible output of a collaborative effort, or be built by individual group members to demonstrate their engagement with the topic as an alternative to a report or essay .

We know there are many approaches to group work and we’d love to hear your tips and experiences with this classroom approach! Please do get in touch to share your ideas at [email protected] , or on any of our social media platforms.

Want to try Kialo Edu with your class?

Use Kialo Edu to have thoughtful classroom discussions and train students’ argumentation and critical thinking skills — completely free!

Challenges of Group Work in College

Group work allows college students to explore and apply concepts beyond the scope of lectures, but cooperative learning has drawbacks. Personalities, attitudes, schedules and confusion on the material can interfere with productive group work. No matter how you feel about group projects, anticipating the challenges helps you work with your classmates.

Coordinating Schedules

Collaborative work completed outside class time requires members to coordinate already busy schedules to find time to meet. Groups need to meet periodically, even if the work is delegated and completed individually. The group meetings allow members to discuss the project, synthesize individual parts and prepare for class presentation components of the assignment. Finding a chunk of time to complete all of the collaborative work is often difficult with varied schedules among the group members.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

Work Load Distribution

In an ideal group, all members contribute equally. In reality, many groups include at least one member who wants to let everyone else do the work. Frustrated group members pick up the slack so that the project is completed with a decent grade. Another problem is a group member who wants to control the entire project. This controlling personality may take on too much of the project himself or dictate work to other members without their approval. Splitting up the workload equally is often a challenge, even when all members are willing to participate, as some components of the project naturally require more work than others.

More For You

Tips on going to school part time while working, what are advantages of online colleges, losing focus in college, negative effects of online courses, the differences between small colleges & big universities.

Conflicts often arise when a group of people work together. Different personalities aren't always compatible, especially when you have one or more opinionated members. Different background experience affects individual perspectives and sometimes adds to the conflict. Individuals may have different ideas on how to proceed with the group work, or individuals may have different interpretations of the concepts or project requirements and goals. Conflict can push the group toward genuine discussion that improves the project, but too much conflict affects the group dynamic and wastes time better spent on the work.

Understanding

Group work puts the students in charge of learning, with limited input from the professor. While the material is usually covered in class before the assignment, group members are often left to explore the information in depth beyond the class information. If the concepts are unclear or confusing, the group will likely struggle to complete the assignment. Even if the work is completed, the members won't likely gain much value unless they truly comprehend the ideas.

- Faculty Focus: My Students Don't Like Group Work

- Stanford University: Cooperative Learning: Students Working in Small Groups

Based in the Midwest, Shelley Frost has been writing parenting and education articles since 2007. Her experience comes from teaching, tutoring and managing educational after school programs. Frost worked in insurance and software testing before becoming a writer. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in elementary education with a reading endorsement.

IMAGES

VIDEO