- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Taxation Without Representation

- Modern Examples

The Bottom Line

- Personal Finance

Taxation Without Representation: What It Means and History

Julia Kagan is a financial/consumer journalist and former senior editor, personal finance, of Investopedia.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Julia_Kagan_BW_web_ready-4-4e918378cc90496d84ee23642957234b.jpg)

Lea Uradu, J.D. is a Maryland State Registered Tax Preparer, State Certified Notary Public, Certified VITA Tax Preparer, IRS Annual Filing Season Program Participant, and Tax Writer.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/lea_uradu_updated_hs_121119-LeaUradu-7c54e49efe814a048e41278182ba02f8.jpg)

What Is Taxation Without Representation?

The phrase taxation without representation describes a populace that is required to pay taxes to a government authority without having any say in that government's policies. The term has its origin in a slogan of the American colonials against their British rulers: " Taxation without representation is tyranny."

Key Takeaways

- Taxation without representation was possibly the first slogan adopted by American colonists chafing under British rule.

- They objected to the imposition of taxes on colonists by a government that gave them no role in its policies.

- In the 21st century, residents of the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico are U.S. citizens who endure taxation without federal representation.

Investopedia / Candra Huff

History of Taxation Without Representation

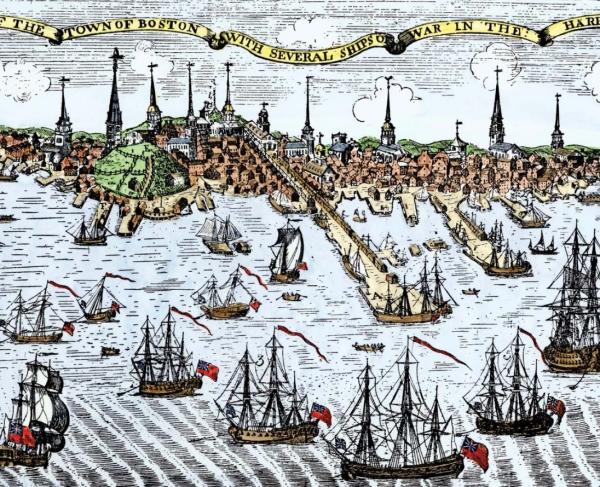

Although taxation without representation has been perpetrated in many cultures, the phrase came to the common lexicon during the 1700s in the American colonies. Opposition to taxation without representation was one of the primary causes of the American Revolution.

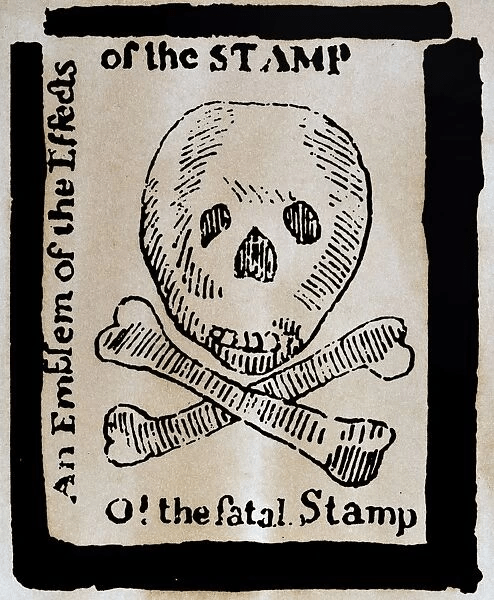

The Stamp Act Triggers Colonists

The British Parliament began taxing its American colonists directly in the 1760s, ostensibly to recoup losses incurred during the Seven Years’ War of 1754 to 1763.

One particularly despised tax, imposed by the Stamp Act of 1765 , required colonial printers to pay a tax on documents used or created in the colonies and to prove it by affixing an embossed revenue stamp to the documents.

Violators were tried in vice-admiralty courts without a jury. The denial of a trial by peers was a second injury in the minds of colonists, compounding the problem of taxation without governmental representation.

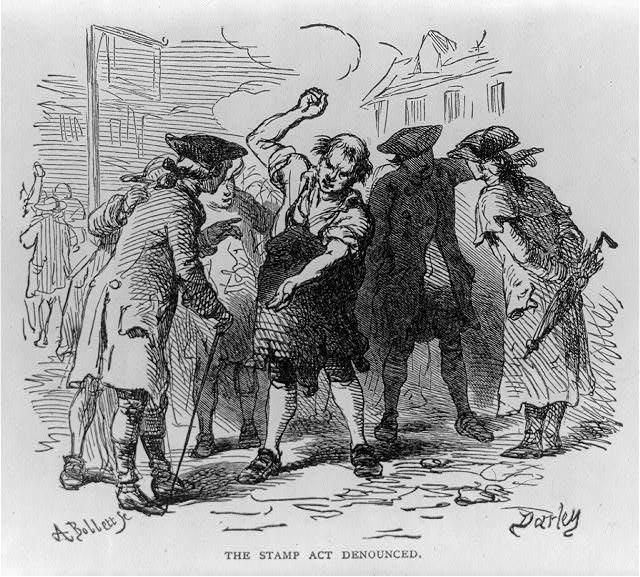

Revolt Against the Stamp Act

Colonists considered the tax to be illegal because they had no representation in the Parliament that passed it and were denied the right to a trial by a jury of their peers. Delegates from nine of the 13 colonies met in New York in October 1765 to form the Stamp Act Congress.

William Samuel Johnson of Connecticut, John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, John Rutledge of South Carolina, and other prominent colonials met for 18 days. They then approved a "Declaration of the Rights and Grievances of the Colonists," stating the delegates’ joint position for other colonists to read. Resolutions three, four, and five stressed the delegates’ loyalty to the crown while stating their objection to taxation without representation.

A later resolution disputed the use of admiralty courts that conducted trials without juries, citing a violation of the rights of all free Englishmen. The Congress eventually drafted three petitions addressed to King George III, the House of Lords, and the House of Commons.

After the Stamp Act

The petitions were initially ignored, but boycotts of British imports and other financial pressures by the colonists finally led to the repeal of the Stamp Act in March 1766. In spite of the repeal, and after years of increasing tensions, the American Revolution began on April 19, 1775, with battles between American colonists and British soldiers in Lexington and Concord.

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee introduced a resolution to Congress declaring the 13 colonies free from British rule. Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson were among the representatives chosen to word the resolution that declared the colonists' intent to dissolve ties with Britain and become self-governing. Taxation without representation has since been considered one of the instigating grievances of the American Revolution.

The Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, with the signing occurring primarily on Aug. 2, 1776.

Modern Examples of Taxation Without Representation

Taxation without representation in the United States did not end with the separation of the American colonies from Britain . There are still parts of the U.S. that pay taxes without receiving representation in the federal government.

Residents of Puerto Rico, for example, are U.S. citizens but do not have the right to vote in presidential elections. They also have no voting representatives in the U.S. Congress unless they move to one of the 50 states.

Residents of Washington, D.C., pay federal taxes despite having no voting representation in Congress. Beginning in the year 2000, the phrase "Taxation Without Representation" appeared on license plates issued by the District of Columbia to increase awareness of this disparity. In 2017, the District's City Council changed the slogan to "End Taxation Without Representation."

Which Tax Triggered the Rebellion Against Great Britain?

The Stamp Act of 1765 angered many colonists as it taxed every paper document used in the colonies. It was the first tax that the crown had demanded specifically from American colonists. However, there were many causes of the American Revolution in addition to anger over the Stamp Act.

Did Taxation Without Representation End After the American Revolution?

After the American Revolution, taxation without representation ended in some areas of the United States. While residents of the 50 states can elect representatives to the federal government, federal districts like Washington, D.C., and territories like Puerto Rico still lack the same representation on the federal level.

Does Taxation Without Representation Refer to Local or Federal Government?

Today, the phrase refers to a lack of representation at the federal level. As an example, Puerto Rico has the same structure as a state, with mayors of cities and a governor. Puerto Ricans are United States citizens. But instead of senators or representatives in Congress, they have a resident commissioner that represents the people in Washington, D.C., and Puerto Ricans can only vote for president if they establish residency in the 50 states.

"Taxation without representation" refers to those taxes imposed on a population who doesn't have representation in the government. The slogan "No taxation without representation" was first adopted during the American Revolution by American colonists under British rule.

Today, the phrase refers to a lack of representation at the federal level. Residents of Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico are still taxed without representation.

National Constitution Center. " On This Day: 'No Taxation Without Representation!' "

Government of the District of Columbia. " Why Statehood for DC ."

United States Department of State, Office of the Historian. " French and Indian War/Seven Years’ War, 1754–63 ."

National Parks Service. " Britain Begins Taxing the Colonies: The Sugar & Stamp Acts ."

Library of Congress. " Magna Carta: Muse and Mentor - No Taxation Without Representation ."

University of Michigan Library. " Proceedings of the Congress at the New-York, Boston, 1765 ."

University of Michigan Library. " Proceedings of the Congress at New York - WEDNESDAY, October 23, 1765, A. M ."

University of Michigan Library. " Proceedings of the Congress at New York - TUESDAY, October 22, 1765, A. M ."

Yale Law School, The Avalon Project. " Great Britain: Parliament - An Act Repealing the Stamp Act; March 18, 1766 ."

American Battlefield Trust. " Lexington and Concord ."

National Archives. " Signers of the Declaration of Independence ."

Library of Congress. " Declaring Independence: Drafting the Documents ."

National Park Service. " The Second Continental Congress and the Declaration of Independence ."

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. " Voting Rights in US Territories ." Page 4.

National Archives. " Unratified Amendments: DC Voting Rights ."

Department of Motor Vehicles, District of Columbia. " End Taxation Without Representation Tags ."

Council of the District of Columbia. " B21-0708 - End Taxation Without Representation Amendment Act of 2016 ."

Library of Congress. " The Commonwealth of Puerto Rico and its Government Structure ."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-183236912-31ef7b27044e4c2a965c4e4e61578482.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

Everything you've ever wanted to know about the American Revolution

No Taxation Without Representation – Meaning, Origins & More

About the author.

Edward A. St. Germain created AmericanRevolution.org in 1996. He was an avid historian with a keen interest in the Revolutionary War and American culture and society in the 18th century. On this website, he created and collated a huge collection of articles, images, and other media pertaining to the American Revolution. Edward was also a Vietnam veteran, and his investigative skills led to a career as a private detective in later life.

“No taxation without representation” was a political slogan used by American Patriots in the Thirteen Colonies.

In this article, we’ve explained the meaning and origins of this slogan, and its historical context.

Historical context

After the French and Indian War (1754–1763) the British government was in a huge amount of debt.

To repay the debt, they began implementing new taxes on their American colonies. To the British, the whole purpose of having overseas colonies was to enrich their empire, and they saw it as their right to raise taxes at their discretion in the Thirteen Colonies.

In 1764, the British parliament passed the Sugar Act. The new law imposed tighter trade restrictions on sugar and molasses, and introduced new taxes on wine, coffee, and certain types of fabrics.

The colonists were upset by the introduction of the new tax. The British stated that they were raising revenue to fund the continued presence of the British Army on the continent. However, the colonies were in an economic depression, and most people did not see the continued need to station large numbers of British soldiers in America.

In 1765, the British went a step further, implementing the Stamp Act, which was even more disliked.

The Stamp Act created a new tax on nearly all printed material, including newspapers, books, and even playing cards. Printed media had to have a special revenue stamp from the British government, to signify that the tax had been paid.

Meaning of “No taxation without representation”

The colonists heavily protested the Stamp Act, labeling it unfair, and saying that the British government was being tyrannical.

The amount of tax was not the biggest issue. The colonists’ main argument against the tax was that it was implemented without their input.

Crucially, colonists argued that it was unfair that in return for the tax they paid, they had no representation in the British parliament. They had no say in how much tax they would pay, or how the money would be spent. They also had no ability to vote in elections.

“No taxation without representation” meant that the Patriots felt unjustly treated by the British, and wanted political representation, at the very least, in return for the taxes they paid.

Who said “no taxation without representation”?

The phrase “no taxation without representation” became a political slogan of Patriots who protested against the British government, as well as Patriot politicians, from 1765 onwards.

Sons of Liberty members in Boston for example used this phrase while protesting British taxation policy. They also organized efforts to boycott British goods, where possible, to hurt the British government economically.

James Otis Jr. , a lawyer and Patriot politician from Massachusetts, is most closely linked with this slogan, although he may not have been the first to use it. He campaigned heavily against taxation without representation.

In 1764, Otis wrote “…the very act of taxing, exercised over those who are not represented, appears to me to be depriving them of one of their most essential rights, as freemen; and if continued, seems to be in effect an entire disfranchisement of every civil right.”

After the Stamp Act was implemented, he famously stated in a speech at the 1765 Stamp Act Congress “taxation without representation is tyranny”.

It’s important to remember, at the time, most people in America held loyalties to the British Crown, and still considered themselves British.

The positions that Otis Jr. and other Patriots took were quite bold in 1765. However, people thought that it was important to stand up for their rights, given how unfairly they were being treated by the British.

The end of the Stamp Act

Due to the level of backlash faced, the British repealed the Stamp Act in 1766, less than a year after it was implemented.

However, the British did not stop attempting to implement unjust taxes in the colonies, leading to further political unrest.

“No taxation without representation” continued to be used as a political slogan as discontent grew from 1766 to 1775, when the American Revolution began with the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

Was taxation without representation illegal?

Some politicians in the Thirteen Colonies argued that taxation without representation was illegal.

They argued that under British common law, which applied to America at the time, taxes could not be levied without the people’s consent, through their political representatives.

The British on the other hand argued that the colonists had “virtual representation”, meaning that members of the House of Commons and the House of Lords could advocate on their behalf, despite not being elected by them.

Also, taxation without representation was not specifically labeled as illegal under British law, although there were common law provisions that emphasized the importance of consent for taxation.

Could the colonists have received representation?

In the late 1700s, very few people in Britain, less than 5% of the population, could vote in elections, thanks to land ownership requirements. Therefore, any representation the colonists received would have been reserved for rich, white male landowners, rather than offering true representation of everyone in the colonies.

In the 1760s, there were discussions in British parliament about colonial representation. However, these discussions never progressed very far – the British believed that virtual representation was good enough for the colonists, and it would have been unheard of for the British to allow a colony to have its own members of British parliament.

The colonists rejected this, demanding direct representation. Only once the Revolutionary War began did the British attempt reconciliation, and offer the prospect of political representation in return for steps towards peace – but the offer was seen as too little, too late. The colonies were already on the path to seeking full independence, making the prospect of representation in parliament no longer sufficient to halt the momentum of the war.

Related posts

Diary of charles herbert, american prisoner of war in britain.

Read the diary of Charles Herbet, a Continental soldier that was captured by the British Army and sent to a prison of war camp in the UK.

1781 Entries | James Thatcher’s Military Journal

Read entries from 1781 in the journal of James Thatcher, Continental Army surgeon during the American Revolution.

1780 Entries | James Thatcher’s Military Journal

Read entries from 1780 in the journal of James Thatcher, Continental Army surgeon during the American Revolution.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Tax Planning

What Is Taxation Without Representation?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Sarah-Fisher-WebReady-01-271f64d902c2476daaec4cf43d53dd3b.jpg)

How Taxation Without Representation Works

Examples of taxation without representation, frequently asked questions.

miralex / Getty Images

“Taxation without representation” is a slogan used to describe being forced by a government to pay a tax without having a say—such as through an elected representative—in the actions of that government. This phrase illustrates the colonists' grievances during the American Revolution and fueled their desire for independence from British rule.

Key Takeaways

- “Taxation without representation” is a phrase used to describe being subjected to taxes without having a legislative say in the government imposing the tax.

- In the U.S., the phrase has its roots in the colonial period when colonists were angered by the British Parliament imposing taxes on them while the colonists themselves had no representatives in Parliament.

- Throughout the history of the U.S., other groups, such as free Black men, women, and residents of certain jurisdictions, have argued that they were and remain subject to taxation without representation.

In the U.S., the concept of taxation without representation has its origins in a 1754 letter from Benjamin Franklin to Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts.

In this letter, titled “On the Imposition of Direct Taxes Upon the Colonies Without Their Consent,” Franklin wrote:

“[E]xcluding the people of the colonies from all share in the choice of the grand council will give extreme dissatisfaction, as well as the taxing them by act of Parliament, where they have no representative… It is supposed an undoubted right of Englishmen not to be taxed but by their own consent, given through their representatives.”

The phrase was widely used a decade later in the colonial response to Parliament’s imposition of the Stamp Act of 1765. The Stamp Act imposed a tax on paper, legal documents, and various commodities. It also reduced the rights of colonists, including limiting trial by jury. It was repealed in 1766.

The same day that the Stamp Act was repealed, the Declaratory Act was enacted by the British Parliament. That Act effectively stated that the British Parliament had absolute legislative power over the colonies.

The Stamp Act and other British tax acts, like the Townshend Acts of 1776, were major catalysts for the American Revolution.

“Taxation without representation” is a phrase describing the situation of being subject to taxes imposed by a government without being represented in the decisions made by that government.

Washington, D.C.

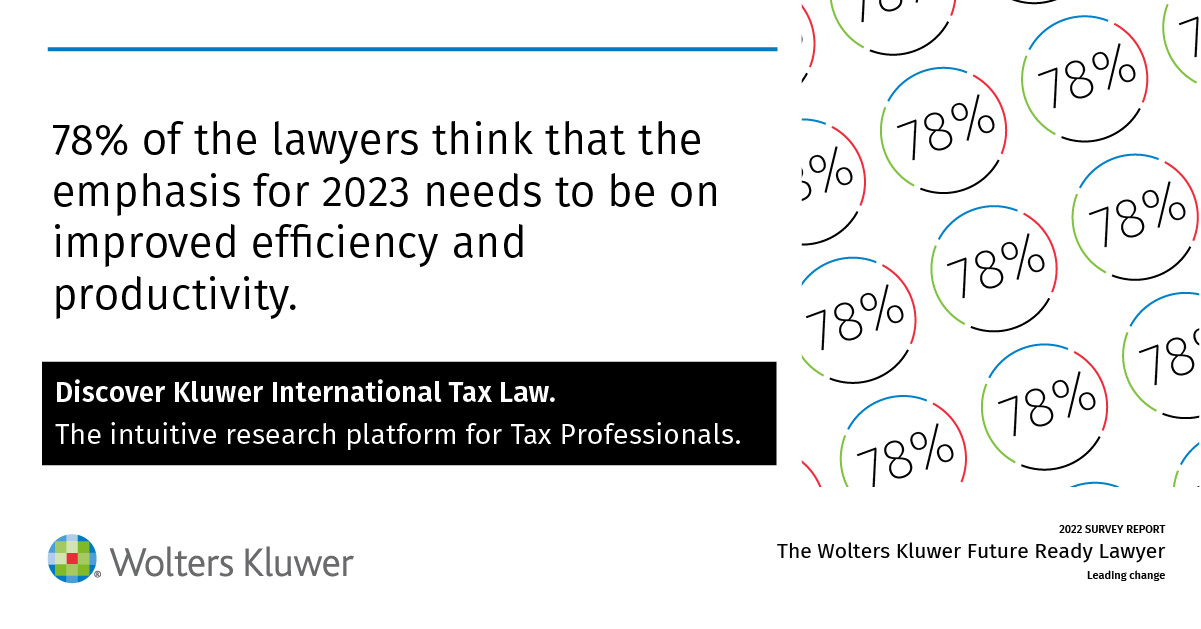

Throughout the history of the U.S.—and even today—various disenfranchised groups and individuals have criticized the fact that they have been subjected to taxation without representation.

Washington, D.C. is an example of modern-day taxation without representation. The residents of the district pay federal taxes, but the District of Columbia has no voting power in Congress . Because the District of Columbia is not a state, it sends a non-voting delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives. While this delegate can draft legislation, they can’t vote. In addition, the District of Columbia can’t send anyone to the U.S. Senate, so it is effectively shut out of that congressional body.

In Washington, D.C. license plates with the phrase “End Taxation Without Representation” at the bottom are issued by default to newly registered vehicles.

While the residents of the District of Columbia are subject to new federal taxes or increases of existing federal taxes that are passed by Congress, they do not have someone representing them who can actually vote on this legislation. They are, therefore, taxed without representation.

Many believe this issue of taxation without representation is a strong argument in favor of D.C. statehood. Others believe, instead, that residents of Washington, D.C., should not be subject to the same federal income taxes as residents of represented states.

Residents of U.S. Territories

The U.S. has five permanently inhabited territories: American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Like Washington, D.C., the five U.S. territories only have non-voting delegates in the U.S. House and no members in the U.S. Senate.

While those residing in the territories are subject to different income tax rules than other residents of the U.S. and, in some cases, pay no federal income taxes, they are subject to other federal taxes, such as the Social Security tax and Medicare tax.

As with Washington, D.C., many have called for statehood for these U.S. territories, especially Puerto Rico.

Free Black Men

Throughout most of the 19th century, free Black men complained they were subject to taxation without representation, and petitioned their governments for tax exemptions , in some cases receiving them. Other states that were petitioned chose to not use race as a voting qualification.

It was not until the 15th Amendment was ratified in 1870 that it was made unconstitutional to prevent a citizen’s right to vote on the basis of race.

It was not until the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920 that it was made unconstitutional in the U.S. to prevent a citizen’s right to vote on the basis of sex.

Before this amendment was ratified, many women appealed that they were subject to taxation without representation. For example, in 1872, American social reformer and women's rights activist Susan B. Anthony went on a speaking tour to deliver an address called “Is It a Crime for a Citizen of the United States to Vote?” In this address, she pointed out that it was taxation without representation to not allow women to vote:

“The women, dissatisfied as they are with this form of government, that enforces taxation without representation… are this half of the people left wholly at the mercy of the other half, in direct violation of the spirit and letter of the decorations of the framers of this government, every one of which was based on the immutable principle of equal rights to all.”

Is there still taxation without representation in the United States?

If you are a resident of Washington D.C. you have to pay federal income taxes, but you don't get a senator or voting congressperson to represent you. Minors are also subject to income taxes above a certain threshold, but they are not permitted to vote. In some states, felons lose the right to vote even after serving their prison sentence, but they are still required to pay taxes.

Why did colonists consider British taxes unjust?

American colonists were unable to vote for any of the legislators in London who determined how much they should pay in taxes, and how those taxes were used. That means they were forced to pay for and support a government that did not give them a voice or a vote.

Constitution.org. “ A Plan for Colonial Union by Benjamin Franklin .”

Library of Congress. “ Magna Carta: Muse and Mentor - No Taxation Without Representation .”

Library of Congress. “ Documents From the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention, 1774 to 1789 .”

Government Publishing Office - Ben’s Guide. “ Declaration of Independence - 1776 .”

Government of the District of Columbia. “ Why Statehood for DC .”

District of Columbia Department of Motor Vehicles. “ End Taxation Without Representation Tags .”

IRS. “ Individuals Living or Working in U.S. Territories/Possessions .”

IRS. “ Persons Employed in a U.S. Possession/Territory - FICA .”

Christopher J. Bryant. “ Without Representation, No Taxation: Free Blacks, Taxes, and Tax Exemptions Between the Revolutionary and Civil Wars .” Page 108. Michigan Journal of Race & Law .

National Constitution Center. “ 15th Amendment - Right to Vote Not Denied by Race .”

National Constitution Center. “ 19th Amendment - Women’s Right To Vote .”

Famous Trials by Prof. Douglas O. Linder. “ Address of Susan B. Anthony .”

- What Does "No Taxation Without Representation" Mean?

“No Taxation without Representation”' is a slogan that was developed in the 1700s by American revolutionists. It was popularized between 1763 and 1775 when American colonies protested against British taxes demanding representation in the British Parliament during the formulation of taxation laws.

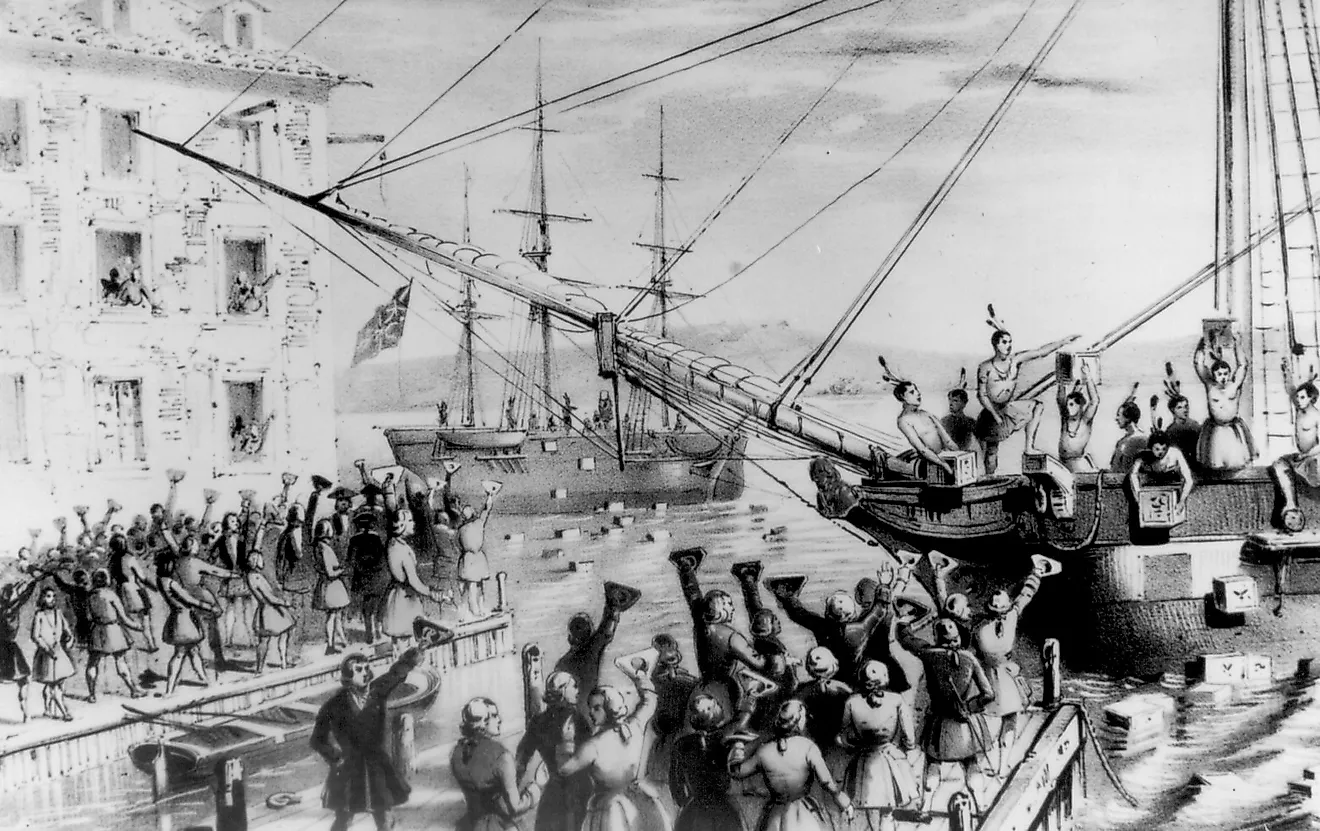

During the British rule in the United States, the Parliament levied taxes on the colonies without consultation, consent or approval of the taxed parties. These laws formed the foundation of the American Revolution and were among the reasons for the havoc of the Boston Tea Party. The Stamp, Tea, and Sugar Acts were among the laws passed by the British Parliament based in the United Kingdom. The colonists complained that parliament was violating the right to representation, which was a tradition of the Englishman. The British Parliament claimed that America was an extension of Britain, but the Americans argued that parliamentarians knew nothing concerning America.

In 1765, the Americans rejected the Stamp Act , and in 1773, they rebelled against taxation of tea imports. An armed tussle ensued and quickly escalated into the American War of Independence. Although the taxes introduced by the British were low, much of the complaint was not about the amount but the decision-making process in which the taxes were decided.

Origin Of The Phrase

Reverend Jonathan Mayhew coined the slogan “No Taxation without Representation" during a sermon in Boston in 1750. By 1764, the phrase had become popular among American activists in the city. Political activist James Otis later revamped the phrase to "taxation without representation is tyranny." In the mid-1760s, Americans believed that the British were depriving them of a historical right prompting Virginia to pass resolutions declaring Americans equal to the Englishmen. The English constitution stipulated that there should not be taxation without representation, and therefore only Virginia could tax Virginians.

Modern Usage

The phrase "No Taxation without Representation” has been adopted as a global slogan to rally against exclusion from political decisions, unresponsive governments, and high taxes. It was used by women movements to decry the denial of voting rights. The TEA (Taxed Already Enough) movement continues to use the slogan to undermine Washington’s continued lack of fiscal restraint without considering public opinion. The phrase appears on the District of Columbia license plates because the citizens of the district pay federal taxes yet they are not represented by a voting member in Congress .

- World Facts

More in World Facts

The Largest Countries In Asia By Area

The World's Oldest Civilizations

Olympic Games History

Southeast Asian Countries

Is Australia A Country Or A Continent?

Is Turkey In Europe Or Asia?

How Many Countries Are Recognized By The United States?

Commonwealth Of Independent States

"No Taxation Without Representation"

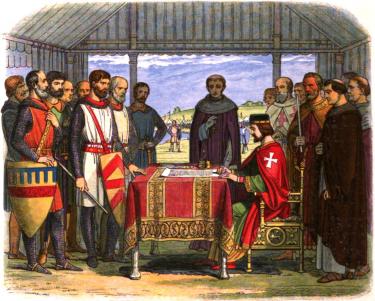

Perhaps no phrase is used more to describe the grievances of the colonists in the lead up to the American Revolution than “No taxation without representation!” While the exact phrase did not appear until 1768, the principle of having consent from the people on issues of taxation can be traced all the way back to the Magna Carta in 1215.

The Magna Carta was one of the first steps in limiting the power of the king and transferring that power to the legislative body in England, the Parliament. Parliament had the power to levy taxes. When King Charles I attempted to impose taxes by himself on the English people in 1627, the Parliament passed the Petition of Right the following year, which stated that the subjects of the king “should not be compelled to contribute to any tax, tallage, aid, or other like charge not set by common consent, in parliament.”

The Magna Carta, the Petition of Right and the English Bill of Rights from 1689 helped to form the basis of the British constitution (which is not a single document, but a combination of written and unwritten agreements). The British constitution protected the rights of Englishmen. English colonists in North America believed that they had the same rights of Englishmen. In North America, colonists formed their own colonial governments under charters from the king and regulated their own forms of taxation from their colonial legislatures. For many decades, these colonies enjoyed an extended period of benign neglect as the English parliament let them handle taxation on their own.

In Great Britain in the eighteenth century, there were no income taxes because it was viewed as too much of a government intrusion into the lives of the people. Instead, taxes were placed on property and on imported and exported goods. Money from these taxes helped to pay for public goods and services and supported the government’s military for defense.

In North America, the British colonies regulated their own tax system in each individual colony. These taxes, though, were exceedingly low, and the colonies did not have a professional military to support. Instead, they used a volunteer militia system to defend their towns and homes from attacks along the frontier.

In 1754, the French and Indian War broke out in North America. During the war, the British sent their military to help defend the colonies. The war spread across the globe and became known as the Seven Years’ War. Following Britain’s victory in 1763, the British national debt greatly increased. They now had a larger empire now that needed to be defended. In light of this tenuous situation, and since the North American colonists benefitted directly from the British military during the war, Great Britain looked to levy taxes on the colonists to raise revenue for the Crown.

In Massachusetts in 1764, James Otis published a pamphlet titled “The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved,” which argued that man’s rights come from God and that governments should only exist to protect those natural rights. He believed that any attempt to tax the colonists without their consent violated the British constitution. Here, Otis made a compelling argument for the need for representation in any taxation on the colonies: “no parts of His Majesty’s dominions can be taxed without their consent; that every part has a right to be represented in the supreme or some subordinate legislature; that the refusal of this would seem to be a contradiction in practice to the theory of the constitution.”

In 1764, the British Parliament passed the Sugar Act, which revised a 1733 tax on molasses being imported to the North American colonies from the West Indies. It improved the enforcement of this tax and explicitly stated that the reason was to raise revenue, a first of its kind. American colonists, especially in New England, responded furiously to this new tax.

Samuel Adams said in response to the Sugar Act: “If taxes are laid upon us in any shape without ever having a legal representative where they are laid, are we not reduced from the character of free subjects to the miserable state of tributary slaves?”

While the colonists likened their situation to slaves of the British Empire, American colonists paid very little in taxes compared with their counterparts in Great Britain. In Great Britain, a person paid about 26 shillings a year in taxes, while in America, they still paid only 1 shilling a year in taxes. Despite this, the American colonists strongly opposed the tax and the lack of any power to influence the decisions of Parliament.

The following year, in 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, which levied a tax on many paper goods (such as newspapers, pamphlets, and legal documents) within the colonies. American colonists met the Stamp Act with protests and outrage. Protests included violence against tax collectors, the formation of the Sons of Liberty, and the creation of numerous “Liberty Trees” where gatherings and demonstrations against British overreach were displayed. In October 1765, delegates from nine different colonies gathered in New York at the Stamp Act Congress. They passed a Declaration of Rights and Grievances in which they asserted in part “that it is inseparably essential to the freedom of a people, and the undoubted rights of Englishmen, that no taxes should be imposed on them, but with their own consent, given personally, or by their representatives.”

The Stamp Act became so unpopular that in 1766 Parliament repealed the act. However, they also passed a Declaratory Act that directly contradicted the colonists view on the authority to levy taxes. The Declaratory Act noted that Parliament “had hath, and of right ought to have, full power and authority to make laws and statutes of sufficient force and validity to bind the colonies and people of America, subjects of the crown of Great Britain, in all cases whatsoever.”

In 1768, the catchphrase of “No taxation without representation” first appeared in a London newspaper. As debate continued throughout the 1760s and 1770s over whether the Crown had the right to tax the colonial subjects, the phrase grew more and more popular. It provided an ideological argument in a short and powerful way against many of the subsequent taxes, such as the Townshend Acts in 1767 and 1768 and the Tea Act in 1773. As the colonies grew more and more rebellious to these taxes, the Crown pushed back stronger and only further drove the two parties towards organized conflict. Conflict finally ignited in 1775, and by the following year, the colonies united and declared their independence from Great Britain.

In 1778, Parliament finally passed the Taxation of Colonies Act which repealed the taxes, but by that point it was too late. What had begun as an argument over the ability and right to levy taxes had expanded into a conflict over the right of self-determination and freedom.

Today, the phrase “No taxation without representation” continues to be used by people who want to have a say in how they are taxed. It remains a powerful phrase that provokes people to think about the consent of the governed.

The Other Tea Parties

The Colonial Responses to the Intolerable Acts

“Boston a Teapot Tonight!”

You may also like.

All Subjects

study guides for every class

That actually explain what's on your next test, taxation without representation, from class:, ap us history.

Taxation without Representation refers to the principle that it is unfair for a government to impose taxes on its citizens without their consent, typically expressed through elected representatives. This concept became a rallying cry for the American colonists in the 18th century, leading them to oppose British taxation policies that they believed violated their rights. The discontent over such taxation practices contributed significantly to the growing desire for independence and ultimately fueled the American Revolution.

5 Must Know Facts For Your Next Test

- The phrase 'No taxation without representation' originated in colonial America and captured the resentment of colonists toward British laws that taxed them without their consent through elected officials.

- The imposition of various taxes by the British Parliament, such as the Stamp Act and Townshend Acts, sparked widespread protests and helped unify the colonies against British rule.

- Colonists argued that their rights as Englishmen included the right to be taxed only by their own elected representatives, and they believed that Parliament, being distant and unrepresentative, had no right to tax them.

- The concept of taxation without representation highlighted broader themes of liberty and self-governance, laying the groundwork for revolutionary sentiments among colonists.

- The push against taxation without representation was instrumental in fostering unity among the colonies, leading to organized resistance movements and ultimately paving the way for the Declaration of Independence.

Review Questions

- The principle of taxation without representation served as a key motivator for colonial unity by highlighting common grievances among the colonies regarding British tax policies. Colonists across different regions recognized that they were all facing similar injustices imposed by Parliament, which lacked their consent. This shared sentiment helped foster cooperation among colonies, culminating in collective actions like protests and boycotts against British goods.

- Specific tax acts such as the Stamp Act and Townshend Acts dramatically shifted colonial attitudes toward British governance. These acts not only imposed financial burdens but also galvanized widespread resistance and protest across the colonies. The backlash against these laws demonstrated that colonists were willing to challenge British authority, viewing these taxes as an infringement on their rights as English subjects. Such actions contributed to a growing revolutionary sentiment that rejected British rule altogether.

- Taxation without representation became a fundamental ideological foundation of the American Revolution by encapsulating a demand for self-governance and individual rights. This rallying cry informed revolutionary leaders' arguments for independence and established principles that would later influence democratic governance in America. The fight against unjust taxation laid the groundwork for future democratic ideals, emphasizing the importance of representation and consent in government operations, which remain relevant in contemporary discussions about political rights and responsibilities.

Related terms

A 1765 British law that imposed a direct tax on the colonies, requiring many printed materials to carry a tax stamp, igniting protests and resistance among colonists.

A 1773 protest by American colonists against British taxation, during which they dumped tea into Boston Harbor to oppose the Tea Act, symbolizing their resistance to taxation without representation.

A meeting of delegates from twelve of the thirteen colonies in 1774 to address colonial grievances, which included opposition to British taxes imposed without colonial representation.

" Taxation without Representation " also found in:

Subjects ( 10 ).

- Colonial Latin America

- Europe,1890-1945

- Growth of the American Economy

- Honors US History

- Honors World History

- Literature of the Americas Before 1900

- State and Federal Constitutions

- The American Revolution

- The Modern Period

- United States History to 1865

Practice Questions ( 10 )

- Which of the following best describes the colonists' response to the concept of "taxation without representation" in the mid-1700s?

- What was the reaction of American colonists to 'Taxation without Representation'?

- Who wrote a resolution against the Stamp Act in Virginia that denounced taxation without representation?

- What impact did 'Taxation Without Representation' have on America's relationship with Great Britain in the late eighteenth century?

- Which event ignited the widespread colonial protests against 'taxation without representation'?

- Which policy of taxation without representation continued despite growing American protests?

- What was a key principle that remained consistent during the period of "taxation without representation"?

- How did British authorities respond to colonist's protest against 'taxation without representation', reflecting a persistent approach?

- Which act represented the continuation of the policy of taxation without representation following the repeal of the Stamp Act?

- How does colonial opposition to "taxation without representation" still impact United States domestic policy today?

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.

Ap® and sat® are trademarks registered by the college board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website..

Taxation Without Representation — APUSH 3.3 Notes, Review, and Terms

Taxation Without Representation is Topic 3.3 in the AP US History curriculum. It covers Great Britain’s political and economic policies that altered its relationship with the American Colonies, leading to the movement known as the American Revolution.

Samuel Adams. Image Source: National Portrait Gallery .

Taxation Without Representation in Colonial America was the primary cause of the American Revolution. It led to the American Revolutionary War and, ultimately, the establishment of the United States of America.

Thematic Focus

The thematic focus for Topic 3.3 is “America in the World.” During the French and Indian War, the American Colonies took center stage in the final battle between Great Britain and France for control of North America. After the British victory, Parliament decided to raise money from the Colonies through taxes. Americans protested these measures because they did not have elected officials representing them in Parliament, calling it “Taxation Without Representation.” The ideology that developed from 1764 to 1775 was the platform for the American Revolution and laid the foundation for the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution.

Learning Objective

The Learning Objective for this topic is to be able to explain how British colonial policies regarding North America led to the Revolutionary War. The key points are:

The End of Salutary Neglect — British officials decided to end the unwritten policy of Salutary Neglect, enforce the Navigation Acts, and reduce smuggling. However, Prime Minister George Grenville took an extra step, authorizing the British Navy to help enforce the acts and providing officers with incentives to seize and inspect American merchant ships and warehouses without search warrants.

Taxation to Raise Revenue — Parliament passed new laws that taxed goods and products Americans used, including molasses, paper, and tea. The money collected was first used to help cover the cost of the British Army in North America, and the rest was sent to the British Treasury. Before this, the Navigation Acts controlled American trade and manufacturing as part of the British Mercantile System.

Internal Taxes vs. External Taxes — Americans had no say in these “External Taxes,” levied on them by Parliament, which the Coonies considered to be an external legislative body. Americans would have been more open to “Internal Taxes” levied on them by Colonial Legislatures because they elected those officials.

Violations of Rights — Americans believed Taxation Without Representation violated their rights as Englishmen. This included the use of Vice Admiralty Courts for trials and the extradition of Americans to England for trial, which denied Americans their right to trial by a jury of their peers.

Historical Developments

During the 18th Century, Great Britain sought to re-assert its authority over the American Colonies. British officials believed Americans would accept its political and economic measures as loyal subjects of King George III and did not need direct representation in Parliament. However, Americans united against both real and perceived threats to their rights and liberties.

Colonial leaders like James Otis , Stephen Hopkins , and Samuel Adams led the way in calling for resistance to Taxation Without Representation. These men were joined by key Founding Fathers like John Adams , Joseph Warren , and Thomas Jefferson — and many others. Together, they argued for their rights as British subjects based on the rights of individuals, local traditions of self-rule, and the ideas of the Enlightenment.

Benjamin Franklin, likely the most famous American in the world at the time, supported American resistance. Unlike the leaders in the colonies, Franklin was in Europe and often met with British officials to discuss matters regarding the Colonies. Despite his warnings, British officials persisted in governing the Colonies without their consent.

Most of the American leaders were merchants, lawyers, and politicians — members of the upper class. However, the movement for representation found support in the lower classes, especially artisans like Paul Revere.

The rallying cry of “No Taxation Without Representation” was not restricted to the upper class — British policies affected nearly every American in some way (including enslaved Africans). Working-class artisans and farmers, including men like Paul Revere and Israel Putnam , rallied and joined with the leaders of the Patriot Cause.

Review Video

This video from Heimler’s History provides an excellent overview of APUSH 3.3. You can also check out our APUSH Guide , which provides a look at all Units and Topics in the APUSH Curriculum.

Terms and Definitions

The following terms and definitions cover essential topics related to Topic 3.3 and link to content on American History Central that provides a deeper understanding of each topic. Terms and definitions are organized according to the APUSH Themes:

American and National Identity

Work, exchange, and technology, migration and settlement.

- Politics and Power

- America in the World

Geography and the Environment

Culture and society, sugar act crisis (1764).

The Sugar Act Crisis was caused by the passage of the Currency Act and Sugar Act in 1764, along with rumors of the pending Stamp Act. American political leaders, including Samuel Adams, Stephen Hopkins, and James Otis, responded with pamphlets outlining their opposition to the Sugar Act and Taxation Without Representation. At least one incident of violence took place when Rhode Islanders at Fort George fired on the British ship, St. John .

Stamp Act Crisis (1765–1766)

The Stamp Act Crisis was caused by the passage of the Stamp Act in 1765. The Crisis led to violence against British officials, including tax collectors, stamp agents, and governors. Riots took place in larger cities like Boston and New York. The groups that became known as the Sons of Liberty helped organize the civil unrest but quickly moved away from violence and turned their attention to political protest. This led to the organization of the Stamp Act Congress and Committees of Correspondence.

Townshend Crisis (1766–1770)

Following the repeal of the Stamp Act, Parliament looked at new ways to raise revenue from the American Colonies and tighten control over them. Parliament passed the Townshend Acts, which led to the Liberty Affair, the Massachusetts Circular Letter, and the Occupation of Boston.

Liberty Affair (1768)

The Liberty Affair was an incident that took place in Boston after British customs officials seized a ship owned by John Hancock , the wealthy merchant and prominent member of the Sons of Liberty. A violent riot followed, and British officials responded by sending troops to occupy Boston, setting the stage for the Boston Massacre.

Occupation of Boston (1768)

Following the Liberty Affair, British officials in Boston expressed concerns that an uprising was imminent. They accused the local assemblies of coordinating efforts to resist British policies and suggested if there were an uprising in Boston it would spread to other colonies. The only way to stop that from happening was to send troops to Boston to occupy the city. Officials in London responded by sending British troops to Boston to help maintain order. The ships carrying the troops arrived in Boston Harbor on September 28, 1768. On October 1, they disembarked, establishing the “Boston Garrison.” Troops secured quarters at various locations in Boston, including Castle Island, Faneuil Hall, and warehouses at Wheelwright’s Wharf.

Battle of Golden Hill (1770)

The Battle of Golden Hill , also known as the “Golden Hill Riot,” took place in New York City in January 1770. Citizens and workers of New York and members of the Sons of Liberty, led by Isaac Sears, John Lamb, and Alexander McDougall, fought with British Redcoats in the streets of the city — almost two months before the Boston Massacre.

Death of Christopher Seider (1770)

On February 22, 1770, a mob gathered outside the home of a Customs Official, Ebeneezer Richardson. The people were upset that Richardson had broken up a protest in front of the shop owned by Theophilus Lillie, a Loyalist merchant. The crowd turned violent and threw rocks through the windows of Richardson’s house. One of them hit Richardson’s wife. When that happened, Richardson grabbed his gun and fired into the crowd. 11-year-old Christopher Seider was shot twice and killed. Samuel Adams arranged for Seider’s funeral, and a public display was made of what Richardson had done. An estimated 2,000 people attended the funeral at the Granary Burial Ground, which fueled the outrage of the people of Boston.

Boston Massacre (1770)

The Boston Massacre was an incident in which British regulars fired into a group of Bostonians who were harassing them. It is generally considered one of the first acts of violence of the American Revolution.

- Boston Massacre — Facts

- Boston Massacre — APUSH Overview

Gaspee Affair (1772)

The Gaspee Affair was a dispute between British officials and colonial officials over how to handle the Gaspee Incident. The incident took place from June 9–10, 1772, and included Rhode Islanders attacking the British schooner HMS Gaspee, shooting a British naval officer, and destroying the ship by setting it on fire. In the aftermath, British officials investigating the incident wanted to arrest the men responsible and take them to Britain to stand trial. Americans were outraged and believed the right to a fair trial would be violated. Virginia responded by calling for each of the colonies to establish permanent Committees of Correspondence.

Tea Crisis (1773)

In 1770, as a result of colonial protests, Parliament repealed the Townshend duties, except for the tax on tea. In 1773, the Tea Act was passed to help the East India Company and gave it a monopoly on the sale and distribution of tea in the colonies. Colonists resented the act because it maintained the British position that Britain could tax the colonies without granting them representation in Parliament. The crisis over the Tea Act led to the Boston Tea Party.

Boston Tea Party (1773)

The Boston Tea Party was a political protest that took place on the night of December 16, 1773, at Griffin’s Wharf in Boston, Massachusetts. A mob organized by the Sons of Liberty raided three ships and threw all of the tea they were carrying into Boston Harbor . Parliament responded to the incident by passing the Intolerable Acts, which led to the colonies holding the First Continental Congress.

- Boston Tea Party — Facts

- Boston Tea Party — APUSH Overview

Edenton Tea Party (1774)

The Edenton Tea Party took place on October 25, 1774, in Edenton, North Carolina, where 51 women, led by Penelope Barker, signed a resolution to boycott British tea and other imported goods. It was one of the earliest organized political actions by women in the American colonies.

American and National Identity — People

Abigail adams.

Abigail Adams was the wife of John Adams, the second President of the United States, and the mother of the sixth President, John Quincy Adams. Her letters and memoirs of the Revolutionary era are considered to be major historical documents. She strongly supported her husband while he was serving in the Continental Congress and in Europe and famously told him to “Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors..”

John Adams was a Founding Father , America’s First Ambassador to the Court of St. James, and the Second President of the United States. He was also the first Vice President, serving two terms under George Washington.

Samuel Adams

Samuel Adams was a Founding Father , a member of the Continental Congress, a Signer of the Declaration of Independence, and a leading proponent of colonial independence from Great Britain. After the Revolution, Adams served four terms as Governor of Massachusetts.

Crispus Attucks

Crispus Attucks was born into slavery. He escaped and went on to be a seaman and rope maker in colonial Boston. He was involved in a mob that accosted British regulars on March 5, 1770. When the regulars retaliated, he was the first person killed in what was quickly known as the Boston Massacre. After his death, he would be remembered as a martyr and seen as a symbol of freedom during the American Revolution and later on during the Abolition movement.

John Dickinson

John Dickinson was a Founding Father , known as the “Penman of the Revolution,” for his Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania . Although he refused to sign the Declaration of Independence, his name was signed to the United States Constitution.

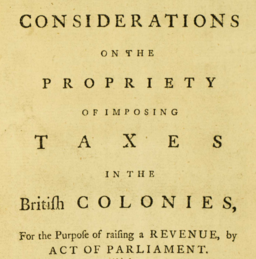

Daniel Dulaney

Daniel Dulany was a prominent Maryland lawyer known for his opposition to the Stamp Act. In his influential pamphlet, Considerations on the Propriety of Imposing Taxes in the British Colonies , Dulany argued that Parliament had no right to tax the colonies without their consent, as they lacked representation.

King George III

George III succeeded his father on the throne. Under his reign, British colonial policy dramatically shifted, leading to the American Revolution and American Revolutionary War. George III was the last British monarch to rule over the American Colonies.

George Grenville

George Grenville was the Prime Minister of Great Britain and was responsible for implementing policies that caused the American Revolution. His policies are known as the Grenville Acts and included the end of Salutary Neglect, the Sugar Act, and the Stamp Act.

Thomas Hutchinson

Thomas Hutchinson was a prominent figure in Massachusetts during the lead-up to the American Revolution. He is most well-known for serving as the Governor of Massachusetts during a significant portion of the American Revolution and the Boston Tea Party.

John Lamb was a prominent leader of the Sons of Liberty in New York and a vocal opponent of British policies during the American Revolution. He was a close associate of Alexander McDougall, Isaac Sears, and Caspar Wistar. He was involved in the Battle of Golden Hill. Lamb served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War.

Ebenezer Mackintosh

Ebenezer Mackintosh was a Boston shoemaker and gang leader of the working-class faction of the Sons of Liberty in Boston during the 1760s. He is well-known for leading violent protests, including the attack on the homes of Andrew Oliver and Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson.

Alexander McDougall

Alexander McDougall was a prominent leader of the New York Sons of Liberty and served as a General in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. McDougall is most famous for his role as a leader of the Patriot Cause in New York City.

James Otis was a Founding Father and a successful lawyer from Boston, Massachusetts, who significantly influenced the ideology of the American Revolution. He is most famous for his opposition to Writs of Assistance, the Sugar Act, and the Townshend Acts.

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine was a Founding Father , a philosopher of the American Revolution, and a true revolutionary. His essays and pamphlets, especially Common Sense , noted for their plain language, resonated with the common people of America and roused them to rally behind the movement for independence. Following the American Revolutionary War, Paine immigrated to Europe, where the British government declared him an outlaw for his anti-monarchist views and where he actively participated in the French Revolution.

Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Rush was a Founding Father , Signer of the Declaration of Independence, Member of the Continental Army, and advocate for the ratification of the United States Constitution. Rush was also a prominent physician, educator, and proponent of women’s rights and the abolition of slavery.

Joseph Warren

Dr. Joseph Warren was one of the prominent leaders of the Patriots in Boston . Closely aligned with Samuel Adams and the Sons of Liberty, Warren was involved in the Committee of Correspondence and Massachusetts Provincial Congress. He was the author of prominent documents, including the Suffolk Resolves.

Mercy Otis Warren

Mercy Otis Warren was the sister of James Otis and the wife of James Warren. She was also close friends with Abigail Adams. The Warrens were intense revolutionaries and hosted groups, including the Sons of Liberty and Committees of Correspondence, in their home. However, it was primarily her writing that made her “perhaps the most important of Revolutionary War women.” She wrote The Rise, Progress and Termination of the American Revolution (1805), her eyewitness account of the revolution, and the first published history of the Revolution.

Artisans in Colonial America were skilled craftspeople who produced goods such as furniture, clothing, metalwork, and tools by hand. They played an important role in the economy of the colonies, working in trades like blacksmithing, carpentry, shoemaking, and weaving. They were often organized into guilds or trade associations to regulate their work and maintain standards. They became involved in the Patriot Cause and joined groups like the Sons of Liberty. One of the most prominent artisans was Paul Revere , a silversmith.

East India Tea Company

The British East India Company , founded in 1600, played a key role in British imperial expansion, primarily in India and the East Indies. However, its financial troubles led Parliament to pass the Tea Act, which led to the Boston Tea Party, triggering a series of events that led to the American Revolutionary War.

Sycamore Shoals

Sycamore Shoals, located along the Watauga River in present-day Tennessee, is the site where Richard Henderson and Daniel Boone negotiated the Transylvania Purchase with Cherokee leaders. In 1780, it served as the rallying point for the Overmountain Men , who assembled and marched against British forces at the Battle of Kings Mountain .

Transylvania Colony

Colonel Richard Henderson, a North Carolina lawyer, envisioned the creation of his own proprietary colony in Kentucky, similar to Maryland and Pennsylvania. Henderson called his venture Transylvania Colony, but it failed to last. His company was dissolved in December 1776, roughly a year and a half after the establishment of Boonesborough. However, Henderson played an important role by providing organized support to the early settlements of 1775.

In the 1760s, settlers moved into Southwest Virginia, over the Allegheny Mountains, and established settlements along the Holston River, Watauga River, and Nolichucky River. One of the locations, Watauga Old Fields, was situated near the Watauga River. The site was also used as a traditional gathering place for Indians and as hunting grounds. Despite the Proclamation of 1763, settlers continued to live in the area and started the construction of a fort, originally known as Fort Caswell. It was near Sycamore Shoals, along the Watauga River, near present-day Elizabethton.

Wilderness Road

The Wilderness Road , blazed by Daniel Boone and a group of men under his command, was a vital route for American pioneers who emigrated west in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It is believed that as many as 300,000 people took the Wilderness Road into Kentucky.

Politics and Power — American Political Resistance

Stamp act congress (1765).

The Stamp Act Congress was a meeting of 27 delegates from nine of the 13 Original Colonies that took place in New York City from October 7 to October 25, 1765. They met to discuss a unified colonial response to the provisions of the Stamp Act. The Stamp Act was passed on March 22, 1765, and was set to go into effect on November 1, 1765. The meeting produced a document called the “Declaration of Rights and Grievances” that was sent to the colonial legislatures, the King, and both houses of Parliament. Although the Declaration and letters were rejected by colonial agents and British officials, the Stamp Act Congress marked the first time a “continental congress” was held by the colonies in order to respond to British policies. The Stamp Act Congress was one of the most significant events that took place during the American Revolution.

Boston Non-Importation Agreement (1768)

The Boston Non-Importation Agreement of 1768 was signed by Boston merchants and traders on August 1, 1768. The agreement established a trade boycott against British goods and products in protest of the Townshend Acts.

Massachusetts Circular Letter (1768)

The Massachusetts Circular Letter was written primarily by Samuel Adams in opposition to the Townshend Acts and “Taxation Without Representation.” The letter helped coordinate colonial opposition to the Townshend Acts . Although it increased tension with Great Britain, it also contributed to the growing sense of unity between the American Colonies, laying the foundation for the establishment of Committees of Correspondence and the First Continental Congress.

Watauga Association (1772)

The Watauga Association was the government organized by the settlers living in the Watauga Region. Watauga was outside of British-controlled territory, and the settlers negotiated an agreement with the Cherokee to lease “all the country on the waters of the Watauga.” In 1772, the settlers formed their government, which may have included John Sevier . This was the first American government in Tennessee.

Solemn League and Covenant (1774)

The Solemn League and Covenant was an agreement designed by Patriot leaders in Boston in response to the Boston Port Act. It was intended to stop all trade between the towns in Massachusetts and merchants in Great Britain and was a precursor to the Continental Association.

Suffolk Resolves (1774)

The Suffolk Resolves were written by Joseph Warren in protest of the Intolerable Acts and military preparations taken by Governor Thomas Gage after the Powder Alarm. In its first official act, the First Continental Congress endorsed the Resolves and ordered colonial newspapers to print them.

First Continental Congress (1774)

The First Continental Congress met in Carpenter’s Hall in Philadelphia from September 5, 1774, until October 26, 1774. The meeting was called in response to acts of the British Parliament, collectively known in the Colonies as the Intolerable Acts.

Continental Association (1774)

The Continental Association was an organization created by the First Continental Congress to enforce the Articles of Association — a trade boycott against British merchants — unless Britain repealed the Coercive Acts. Committees of Inspection enforced the rules of the Association. Although Georgia did not send delegates to Congress, it did adopt the Articles of Association.

Politics and Power — Concepts

Non-importation agreements.

Non-Importation Agreements were contracts signed by American merchants and citizens, promising not to import or buy British goods. They were used to protest British tax policies and contributed to the repeal of the Stamp Act.

Standing Army in North America

Following the French and Indian War, Britain needed to protect its new territory in North America and enforce the Proclamation of 1763. To do this, Parliament decided to keep a Standing Army of 10,000 British regulars in the colonies. To pay for and support this new army, Parliament passed the Sugar Act, Stamp Act, and Quartering Act. Americans opposed this army, believing it was a threat to their freedom.

Virtual Representation

Virtual Representation was a concept that argued American interests were represented in Parliament because the members represented all British subjects, regardless of whether they had directly voted for them. Americans rejected this concept because they were accustomed to democratic representation in their local and colonial governments.

Politics and Power — Groups

Committees of correspondence.

The Sons of Liberty and Colonial Legislatures used Committees of Correspondence to create an intercolonial communication network, share critical information, and coordinate opposition to British policies.

Committees of Safety

Committees of Safety were established by local and colonial legislatures to help gather goods, provisions, and military supplies for use by American Militia forces.

Daughters of Liberty

The Daughters of Liberty formed during the Stamp Act Crisis . After the Townshend Acts were passed, the Boston members supported the agreement by spinning wool and kitting wool into cloth. These gatherings were known as “Spinning Bees.” The clothing they made was called “Homespun.” They also refused to drink imported English tea and devised different concoctions of herbs to drink instead.

After news of the passage of the Stamp Act reached the colonies, a group of men in Boston came together. Their goal was to organize resistance to the Stamp Act, and they referred to themselves as the Loyal Nine. Prominent members were Benjamin Edes, the publisher and printer of the Boston Gazette , and Henry Bass, who was a cousin of Samuel Adams. The Loyal Nine are often viewed as the founders of the Sons of Liberty.

Sons of Liberty

The Sons of Liberty was a radical organization in Colonial America created to carry out public demonstrations against British policies that forced Americans to pay taxes without representation in Parliament. Many men associated with the group are considered Founding Fathers of the United States.

Politics and Power — Documents

Rights of the british colonies asserted and proved (1764).

James Otis of Massachusetts published Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved , objecting to the Sugar Act and Parliament’s encroachment on the rights of the colonies and the personal liberties of the colonists.

Rights of the Colonies Examined (1765)

Stephen Hopkins was the Governor of Rhode Island. After he returned from a trip to London in 1764, Hopkins wrote Rights of the Colonies Examined . It was published in 1765. Hopkins echoed many of the same sentiments as James Otis. Hopkins said, “British subjects are to be governed only agreeable to laws by which themselves have in some way consented.”

Virginia Stamp Act Resolves (1765)

On March 22, 1765, the Stamp Act received Royal Assent from King George III. News of the bill’s passage reached the colonies in April. At the next session of the House of Burgesses, a new member, Patrick Henry , delivered a fiery speech on May 29, 1765. In it, he presented a series of resolutions against the Stamp Act. The next day, the House of Burgesses adopted some of Henry’s resolutions and issued the Virginia Stamp Act Resolves . At least ten colonies followed in Virginia’s footsteps and issued Stamp Act Resolutions.

Declarations of the Stamp Act Congress (1765)

On October 19, 1765, the Stamp Act Congress passed the “ Declaration of Rights and Grievances ,” which claimed that American colonists were guaranteed the same rights as other British citizens, protested taxation without representation, and argued Parliament did not have the authority to levy taxes on the colonies.

Leedstown Resolves (1766)

The Leedstown Resolves — or Leedstown Resolutions — is a document that organized the Westmoreland Association for the purpose of resisting the Stamp Act and ensuring Virginians in Westmoreland County did not comply with the law. The document was written by Richard Henry Lee and signed at Leedstown, Virginia, on February 27, 1766. The Westmoreland Association is considered to be one of the first groups that were formally organized to resist British policies.

Letters From a Farmer in Pennsylvania (1767–1768)

Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania was a series of essays written by John Dickinson. They were published in colonial newspapers and became one of the most influential critiques of British taxation policies, particularly the Townshend Acts. Dickinson argued that Parliament could regulate colonial trade but had no right to tax the colonies without their consent.

Politics and Power — Laws and Treaties

Navigation acts.

The Navigation Acts were a series of British laws passed in the 17th and 18th centuries to regulate colonial trade and ensure that most of it benefited the British Empire. These acts required that certain colonial goods could only be transported in British ships, that goods bound for the colonies had to pass through British ports, and that certain key exports (like tobacco and sugar) could only be sold to Britain. These measures were intended to maintain British economic dominance over the American colonies but also generated tension and resentment, ultimately contributing to colonial discontent that led to the American Revolution.

Molasses Act (1733)

The Molasses Act of 1733 was a piece of British legislation that imposed high import duties on molasses, rum, and sugar imported into the American colonies from non-British Caribbean sources, primarily the French West Indies. The act aimed to protect the sugar plantations in the British West Indies and generate revenue for the British Crown. However, it was widely evaded through smuggling and was deeply unpopular among colonial merchants, contributing to the rise of illicit trade and colonial opposition to British economic policies. However, the unwritten policy of Salutary Neglect contributed to lax enforcement of the law’s provisions. Also, see Molasses Act Text .

Writs of Assistance

Writs of Assistance were broad search warrants that allowed British customs officials to search property without a court order and force law enforcement officials to help them. In 1761, James Otis challenged the Writs in court, leading James Adams to say, “American Independence was then and there born.”

Treaty of Paris (1763)

The Treaty of Paris ended the French and Indian War and the Seven Years’ War. France ceded nearly all its territory in North America to Britain and Spain, but it retained several small but valuable sugar islands in the West Indies and fishing stations in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. To compensate Spain for its losses during the war, the French ceded their territory in the Trans-Mississippi Louisiana Region, including New Orleans, to Spain. Great Britain emerged as the dominant power in North America and solidified its position as the leading naval power in the world.

Proclamation of 1763

The Proclamation of 1763 reserved the lands west of the crest of the Appalachian Mountains for the native inhabitants and prohibited colonists from settling in the area.

Currency Act (1764)

Following the French and Indian War, the American economy struggled and suffered from a recession. When American merchants fell behind on paying their bills, British merchants started to demand they pay their debts in hard money — gold and silver coins, also known as specie — rather than colonial paper currency. Hard Money was a far more stable currency than paper money, which meant British merchants could use it for other transactions. To address this issue, Parliament passed the Currency Act , which prohibited the colonies from issuing paper currency. This made it even more challenging for colonists to settle their debts and pay taxes because Hard Money was scarce. Under the Mercantile System, most Hard Money was held by British merchants.

Sugar Act (1764)

The Sugar Act , or the American Revenue Act, was passed by Parliament on April 5, 1764. The goal of the act was to raise revenue for Britain to pay part of the cost of a standing army in North America. It is most famous for starting the controversy over Taxation Without Representation.

- Sugar Act — Facts

- Sugar Act — Guide

Stamp Act (1765)

The Stamp Act was passed by Parliament in 1765 to raise money from the 13 Original Colonies. It required printers and publishers to buy stamps and place them on many legal documents and printed materials in the American colonies, increasing the cry of “No Taxation Without Representation.”

- Stamp Act — Facts

Declaratory Act (1765)

The Declaratory Act was passed by Parliament on March 18, 1766, and asserted Parliament’s authority to pass laws governing the colonies, including taxation.

Quartering Act (1765)

The Quartering Act of 1765 required the colonies to provide provisions and lodging to British soldiers. In New York, it led to political opposition and violent protests that culminated in the Battle of Golden Hill in 1770, just a few weeks before the Boston Massacre.

Townshend Acts (1767–1768)

The Townshend Acts were a series of acts passed by the British Parliament in 1767 and 1768. Colonial resistance to the Acts led to Parliament sending troops to Boston in 1768. Less than two years later, Redcoats fired into an angry mob and killed colonists in the event known as the Boston Massacre.

Tea Act (1773)

The Tea Act addressed the rampant smuggling of tea into the colonies, primarily by the Dutch. Previously, tea imported from the East India Company had to pass through England, where duties were imposed, before reaching the colonies, resulting in higher prices. The Tea Act allowed the direct export of tea to the colonies from the East India Company without customs charges in England, making the tea cheaper for colonial consumers. The British government anticipated the reduced price of tea would encourage colonists to purchase legally imported tea — and implicitly acknowledge parliamentary authority by paying the last tax that remained from the Townshend Acts. Instead, Americans protested, leading to the Boston Tea Party.

Intolerable Acts (Coervice Acts)

The Intolerable Acts , also known as the Coercive Acts, were five laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774. These laws led the colonies to hold the First Continental Congress in September and October 1774. The five laws went into effect on the following dates:

- May 20, 1774 — Administration of Justice Act

- June 1, 1774 — Boston Port Act

- June 2, 1774 — Quartering Act of 1774

- July 1, 1774 — Massachusetts Government Act

- May 1, 1775 — Quebec Act

The Fields, also known as “The Commons,” was an open public area in colonial New York City where the Sons of Liberty held gatherings. A Liberty Pole was erected there, which led to an ongoing conflict between Patriots and British soldiers known as the “Battle of the Liberty Poles.”

Liberty Trees and Liberty Poles

Liberty Trees and Liberty Poles were symbols of resistance against British rule in the American colonies during the lead-up to the American Revolution. The Boston Liberty Tree was a gathering place for the Sons of Liberty and other Patriots to organize protests against British policies. The Providence Liberty Tree served the same purpose in Rhode Island as did the New York Liberty Pole.

Unit 3 Topics and Key Concepts

Key concepts.

3.1 — British attempts to assert tighter control over its North American colonies and the colonial resolve to pursue self-government led to a colonial independence movement and the Revolutionary War.

3.2 — The American Revolution’s democratic and republican ideas inspired new experiments with different forms of government.

3.3 — Migration within North America and competition over resources, boundaries, and trade intensified conflicts among peoples and nations.

- 3.1 — Contextualizing Period 3

- 3.2 — The Seven Years’ War (The French and Indian War)

- 3.3 — Taxation Without Representation

- 3.4 — Philosophical Foundations of the American Revolution

- 3.5 — The American Revolution

- 3.6 — The Influence of Revolutionary Ideals

- 3.7 — The Articles of Confederation

- 3.8 — The Constitutional Convention and Debates over Ratification

- 3.9 — The Constitution

- 3.10 — Shaping a New Republic

- 3.11 — Developing an American Identity

- 3.12 — Movement in the Early Republic

- 3.13 — Continuity and Change in Period 3

- Written by Randal Rust

Explore the Constitution

- The Constitution

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

- Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

- Election Teaching Resources

Constitution 101 With Khan Academy

Explore our new course that empowers students to learn the constitution at their own pace..

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, on this day: “no taxation without representation”.

October 7, 2022 | by NCC Staff

The Stamp Act Congress met on this day in New York in 1765, a meeting that led nine Colonies to declare the English Crown had no right to tax Americans who lacked representation in British Parliament.

The Crown and British Parliament didn’t exactly agree with that idea, and within 10 years, the sides would be at war over some of the concepts endorsed by the 27 delegates in three documents sent by ship to England.