- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Criminal Justice

IResearchNet

Academic Writing Services

Social learning theory.

The purpose of this research paper is to provide an overview of Akers’s social learning theory with attention to its theoretical roots in Sutherland’s differential association theory and the behavioral psychology of Skinner and Bandura. Empirical research testing the utility of social learning theory for explaining variation in crime or deviance is then reviewed; this is followed by a discussion of recent macrolevel applications of the theory (i.e., social structure and social learning). (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

- Introduction

- Origin and Overview of Social Learning Theory

- Differential Association

- Definitions

- Differential Reinforcement

- Testing Social Learning Theory

- Social Structure and Social Learning

- Future Directions

I. Introduction

The purpose of this research paper is to provide an overview of Akers’s social learning theory with attention to its theoretical roots in Sutherland’s differential association theory and the behavioral psychology of Skinner and Bandura. Empirical research testing the utility of social learning theory for explaining variation in crime or deviance is then reviewed; this is followed by a discussion of recent macrolevel applications of the theory (i.e., social structure and social learning). The research paper concludes with a brief offering of suggestions for future research and a summary of the importance of social learning theory as a general theory in the criminological literature.

II. Origin and Overview of Social Learning Theory

Burgess and akers’s (1966).

differential association-reinforcement theory was an effort to meld Sutherland’s (1947) sociological approach in his differential association theory and principles of behavioral psychology. This was the foundation for Akers’s (1968, 1973; Akers, Krohn, Lanza-Kaduce, & Radosevich, 1979) further development of the theory, which he came more often to refer to as social learning theory. Sutherland’s differential association theory is contained in nine propositions:

- Criminal behavior is learned in interaction with other persons in a process of communication.

- The principal part of the learning of criminal behavior occurs within intimate personal groups.

- When criminal behavior is learned, the learning includes (a) techniques of committing the crime, which are sometimes very complicated, sometimes very simple, and (b) the specific direction of motives, drives, rationalizations, and attitudes.

- The specific direction of motives and drives is learned from definitions of the legal codes as favorable or unfavorable.

- A person becomes delinquent because of an excess of definitions favorable to violation of law over definitions unfavorable to violation of the law.

- The process of learning criminal behavior by association with criminal and anti-criminal patterns involves all of the mechanisms that are involved in any other learning.

- Although criminal behavior is an expression of general needs and values, it is not explained by those general needs and values, because noncriminal behavior is an expression of the same needs and values.

- Differential association varies in frequency, duration, priority, and intensity. The most frequent, longest-running, earliest and closest influences will be most efficacious or determinant of learned behavior. (pp. 6–7)

Sutherland (1947)

referred to the sixth statement as the principle of differential association. According to Sutherland, an individual learns two types of definitions toward committing a particular behavior. He can either learn favorable definitions from others that would likely increase the probability that he will commit the behavior, or he can learn unfavorable definitions that would likely decrease the probability that he would engage in a particular behavior. Stated in terms of criminal involvement, when an individual learns favorable definitions toward violations of the law in excess of the definitions unfavorable to violations of the law, that individual is more likely to commit the criminal act(s).

Learning favorable versus unfavorable definitions can also be described as a process whereby individuals attempt to balance pro-criminal definitions against prosocial or conforming definitions. It is logical to assume that individuals learn favorable or pro-criminal definitions for committing crime from those involved in crime themselves (i.e., the criminals) and, in contrast, learn unfavorable definitions for committing crime from those individuals who are not involved in crime, and this assumption is supported empirically. It should be remembered, however, that it is possible for law-abiding persons to expose individuals to pro-criminal attitudes and definitions, just as it is possible for an individual to learn conforming definitions from criminals (see Cressey, 1960, p. 49).

According to Sutherland’s (1947) seventh principle, the theory does not merely state that being associated with criminals leads to crime or that being associated with law-abiding persons leads to conforming behavior. It is the nature, characteristics, and balance of the differential association that affect an individual’s likelihood of violating the law. More specifically, if a person is exposed to pro-criminal definitions first (priority), and these definitions increase in frequency and strength (intensity) and persist for some time (duration), the individual is more likely to demonstrate involvement in criminal and deviant acts.

Although Sutherland’s (1947) differential association theory began to accumulate a rather large amount of attention throughout the sociological and criminological literature in the years after its emergence, Burgess and Akers (1966) noted that the theory had still failed to receive considerable empirical support and had yet to be adequately modified in response to some of its shortcomings and criticisms.

Some of these issues included the inconsistency both within and between studies regarding the support for differential association and a common criticism among scholars on the difficulty of operationalizing the theory’s concepts. In response to these criticisms and the prior failure of differential association theorists in specifying the learning process of the theory, Burgess and Akers presented their reformulated version of the theory, that is, differential association-reinforcement theory.

To describe their revised version in terms of its modifications and derivations from the original theory (as exemplified in Sutherland’s [1947] nine principles), Burgess and Akers (1966) offered the following seven principles that illustrate the process wherein learning takes place:

- Criminal behavior is learned according to the principles of operant conditioning (reformulation of Sutherland’s Principles 1 and 8).

- Criminal behavior is learned both in nonsocial situations that are reinforcing or discriminative and through that social interaction in which the behavior of other persons is reinforcing or discriminative for criminal behavior (reformulation of Sutherland’s Principle 2).

- The principal part of the learning of criminal behavior occurs in those groups whi ch comprise the individual’s major source of reinforcements (reformulation of Sutherland’s Principle 3).

- The learning of criminal behavior, including specific techniques, attitudes, and avoidance procedures, is a function of the effective and available reinforcers, and the existing reinforcement contingencies (reformulation of Sutherland’s Principle 4).

- The specific class of behaviors which are learned and their frequency of occurrence are a function of the reinforcers which are effective and available, and the rules or norms by which these reinforcers are applied (reformulation of Sutherland’s Principle 5).

- Criminal behavior is a function of norms which are discriminative for criminal behavior, the learning of which takes place when such behavior is more highly reinforced than noncriminal behavior (reformulation of Sutherland’s Principle 6).

- The strength of criminal behavior is a direct function of the amount, frequency, and probability of its reinforcement (reformulation of Sutherland’s Principle 7). (pp. 132–145)1

Akers (1973, 1977, 1985, 1998)

has since discussed modifications to this original serial list and has further revised the theory in response to criticisms, theoretical and empirical developments in the literature, and to ease the interpretation and explanations of the key assumptions of social learning theory, but the central tenets remain the same. It is important to note here that, contrary to how social learning is often described in the literature, social learning is not a rival or competitor of Sutherland’s (1947) theory and his original propositions. Instead, it is offered as a broader theory that modifies and builds on Sutherland’s theory and integrates this theoretical perspective with aspects of other scholars’ principles explicated in behavioral learning theory, in particular behavioral acquisition, continuation, and cessation (see Akers, 1985, p. 41). Taken together, social learning theory is presented as a more comprehensive explanation for involvement in crime and deviance compared with Sutherland’s original theory; thus, any such support that it offered for differential association theory provides support for social learning theory, and findings that support social learning theory do not negate/discredit differential association theory.

The behavioral learning aspect of Akers’s social learning theory (as first proposed by Burgess and Akers, 1966) draws from the classical work of B. F. Skinner, yet, more recently, Akers (1998) commented on how his theory is more closely aligned with cognitive learning theories such as those associated with Albert Bandura (1977), among others. According to Burgess and Akers (1996) and, later, Akers (1973, 1977, 1985, 1998), the specific mechanisms by which the learning process takes place are primarily through operant conditioning or differential reinforcement. Stated more clearly, operant behavior, or voluntary actions taken by an individual, are affected by a system of rewards and punishments. These reinforcers and punishers (described later) ultimately influence an individual’s decision of whether to participate in conforming and/or nonconforming behavior.

Burgess and Akers (1966)

originally considered the imitation element of the behavioral learning process (or modeling) to be subsumed under the broad umbrella of operant conditioning; that is, imitation was itself seen as simply one kind of behavior that could be shaped through successive approximations and not a separate behavioral mechanism. However, Akers later began to accept the uniqueness of the learning mechanism of imitation from operant or instrumental learning and to discuss it in terms of observational learning or vicarious reinforcement. Burgess and Akers also recognized the importance of additional behavioral components and principles of learning theory, such as classical conditioning, discriminative stimuli, schedules of reinforcement, and other mechanisms.

Considering the brief overview of social learning theory as described earlier, the central assumption and proposition of social learning theory can be best summarized in the two following statements:

The basic assumption in social learning theory is that the same learning process in a context of social structure, interaction, and situation, produces both conforming and deviant behavior. The difference lies in the direction . . . [of] the balance of influences on behavior. The probability that persons will engage in criminal and deviant behavior is increased and the probability of their conforming to the norm is decreased when they differentially associate with others who commit criminal behavior and espouse definitions favorable to it, are relatively more exposed in-person or symbolically to salient criminal/deviant models, define it as desirable or justified in a situation discriminative for the behavior, and have received in the past and anticipate in the current or future situation relatively greater reward than punishment for the behavior. (Akers, 1998, p. 50)

It is worth emphasizing that social learning theory is a general theory in that it offers an explanation for why individuals first participate in crime and deviance, why they continue to offend, why they escalate/deescalate, why they specialize/generalize, and why they choose to desist from criminal/deviant involvement. Social learning theory also explains why individuals do not become involved in crime/deviance, instead opting to participate only in conforming behaviors. Thus, considering the generality of the theory as an explanation for an individual’s participation in (or lack thereof) prosocial and pro-criminal behaviors, more attention is devoted in the following paragraphs to fleshing out the four central concepts of Akers’s social learning theory that have received considerable (yet varying) amounts of attention and empirical support in the criminological literature: differential association, definitions, differential reinforcement, and imitation (Akers, 1985, 1998; Akers et al., 1979).

III. Differential Association

The differential association component in Akers’s social learning theory is one of primary importance. Although its significance cannot simply be reduced to having “bad” friends, the individuals with whom a person decides to differentially associate and interact (either directly or indirectly) play an integral role in providing the social context wherein social learning occurs. An individual’s direct interaction with others who engage in certain kinds of behavior (criminal/deviant or conforming) and expose the individual to the norms, values, and attitudes supportive of these behaviors affects the decision of whether the individual opts to participate in a particular behavior.

Akers has indicated that family and friends (following Sutherland’s [1947] emphasis on “intimate face-to-face” groups) are typically the primary groups that are the most salient for exposing an individual to favorable/unfavorable definitions and exhibiting conforming and/or nonconforming behaviors. For the most part, learning through differential association occurs within the family in the early childhood years and by means of the associations formed in school, leisure, recreational, and peer groups during adolescence. In contrast, during young adulthood and later in life, the spouses, work groups, and friendship groups typically assume the status of the primary group that provides the social context for learning. Secondary or reference groups can also indirectly provide the context for learning if an individual differentially associates him or herself with the behaviors, norms, values, attitudes, and beliefs with groups of individuals, including neighbors, church leaders, schoolteachers, or even what Warr (2002) called virtual groups, such as the mass media, the Internet, and so on.

According to the theory, the associations that occur early (priority); last longer or occupy a disproportionate amount of one’s time (duration); happen the most frequently; and involve the intimate, closest, or most important partners/peer groups (intensity) will likely exert the greatest effect on an individual’s decision to participate in either conforming or nonconforming behavior. Taking these elements into consideration, the theory proposes that individuals are exposed to pro-criminal and prosocial norms, values, and definitions as well as patterns of reinforcement supportive of criminal or prosocial behavior. The more an individual is differentially associated and exposed to deviant behavior and attitudes transmitted by means of his or her primary and secondary peer groups, the greater his or her probability is for engaging in deviant or criminal behavior:

The groups with which one is in differential association provide the major social contexts in which all of the mechanisms of social learning operate. They not only expose one to definitions, but they also present one with models to imitate and differential reinforcement (source, schedule, value, and amount) for criminal or conforming behavior. (Akers & Sellers, 2004, pp. 85–86)

IV. Definitions

Definitions are one’s own orientations and attitudes toward a given behavior. These personal as opposed to peer and other group definitions (i.e., differential association) are influenced by an individual’s justifications, excuses, and attitudes that consider the commission of a particular act as being more right or wrong, good or bad, desirable or undesirable, justified or unjustified, appropriate or inappropriate. Akers considered these definitions to be expressed in two types: (1) general and (2) specific. General beliefs are one’s personal definitions that are based on religious, moral, and other conventional values. In comparison, specific beliefs are personal definitions that orient an individual either toward committing or away from participating in certain criminal or deviant acts. For example, an individual may believe that it is morally wrong to assault someone and choose not to partake in or condone this sort of violence. Yet, despite his belief toward violence, this same individual may not see any moral or legal wrong in smoking a little bit of marijuana here and there.

Akers also has discussed personal definitions as comprising either conventional beliefs or positive or neutralizing beliefs. Conventional beliefs are definitions that are negative or unfavorable toward committing criminal and deviant acts or favorable toward committing conforming behaviors. In contrast, positive or neutralizing beliefs are those that are supportive or favorable toward crime and deviance. A positive belief is a definition an individual holds that committing a criminal or deviant act is morally desirable or wholly permissible. For instance, if an individual believes that it is “cool” and wholly acceptable to get high on marijuana, then this is a positive belief favorable toward smoking marijuana. Not all who hold this attitude will necessarily indulge, but those who adhere to these definitions have a much higher probability of using marijuana than those who hold to conventional or negative definitions. A neutralizing belief also favors the commission of a criminal or deviant act, but this type of belief is influenced by an individual’s justifications or excuses for why a particular behavior is permissible. For instance, one may have an initially negative attitude toward smoking marijuana but through observation of using models and through associating with users come to accept it as not really bad, or not as harmful as using alcohol, or otherwise come to justify or excuse its use.

Akers’s conceptualization of neutralizing definitions incorporates notions of verbalizations, techniques of neutralization, and moral disengagement that are apparent in other behavioral and criminological literatures (see Bandura, 1990; Cressey, 1953; Sykes & Matza, 1957). Examples of these neutralizing definitions (i.e., justifications, rationalizations, etc.) include statements such as “I do not get paid enough, so I am going to take these office supplies”; “The restaurant makes enough money, so they can afford it if I want to give my friends some free drinks”; “I was under the influence of alcohol, so it is not my fault”; and “This individual deserves to get beat up because he is annoying.” These types of beliefs have both a cognitive and behavioral effect on an individual’s decision to engage in criminal or deviant behavior. Cognitively, these beliefs provide a readily accessible system of justifications that make an individual more likely to commit a criminal or deviant act. Behaviorally, they provide an internal discriminative stimulus that presents an individual with cues as to what kind of behavior is appropriate/justified in a particular situation. For example, if a minimum-wage employee who has been washing dishes full-time at the same restaurant for 5 years suddenly gets his or her hours reduced to part-time because the manager chose to hire another part-time dishwasher, then the long-time employee might decide to steal money from the register or steal food because she believes that she has been treated unjustly and “deserves” it.

Akers and Silverman (2004) went on to argue that some personal definitions are so intense and ingrained into an individual’s learned belief system, such as the radical ideologies of militant and/or terrorists groups, that these definitions alone exert a strong effect on an individual’s probability of committing a deviant or criminal act. Similarly, Anderson’s (1999) “code of the street” can serve as another example of a personal definition that is likely to have a significant role in motivating an individual to participate in crime or deviance. For example, if an urban inner-city youth is walking down the street and observes another youth (who resides in the same area) flaunting nice jewelry, then the urban juvenile might feel justified in “jumping” the kid and taking his jewelry because of the code of the street or the personal belief that “might makes right.” Despite these examples, Akers suggested that the majority of criminal and deviant acts are not motivated in this way; they are either weak conventional beliefs that offer little to no restraint for engaging in crime/deviance or they are positive or neutralizing beliefs that motivate an individual to commit the criminal/deviant act when faced with an opportunity or the right set of circumstances.

V. Differential Reinforcement

Similar to the mechanism of differential association, whereby an imbalance of norms, values, and attitudes favorable toward committing a deviant or criminal act increases the probability that an individual will engage in such behavior, an imbalance in differential reinforcement also increases the likelihood that an individual will commit a given behavior. Furthermore, the past, present, and future anticipated and/or experienced rewards and punishments affect the probability that an individual will participate in a behavior in the first place and whether he or she continues or refrains from the behavior in the future. The differential reinforcement process operates in four key modes: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment.

Consider the following scenario. John is a quiet and shy boy who has difficulty making friends. Two of his classmates approach him on the playground and tell him that they will be his friend if he hits another boy because they do not like this particular child. John may know that hitting others is not right, but he decides to go along with their suggestion in order to gain their friendship. Immediately after he punches the boy, his classmates smile with approval and invite John to come over to their house after school to play with them. This peer approval serves as positive reinforcement for the assault. Positive reinforcement can also be provided when a behavior yields an increase in status, money, awards, or pleasant feelings.

Negative reinforcement can increase the likelihood that a behavior will be repeated if the act allows the individual to escape or avoid adverse or unpleasant stimuli. For example, Chris hates driving to and home from work because every day he has to drive through the same speed trap on the interstate. One day, Chris decides to come into work 1 hour early so he can in turn leave 1 hour early. Chris realizes that by coming in early and subsequently leaving early, he is able to avoid the speed trap because the officers are not posted on the interstate during his new travel times. He repeats this new travel schedule the following day, and once again he avoids the speed trap. His behavior (coming in an hour early and leaving an hour early) has now been negatively reinforced because he avoids the speed trap (i.e., the negative stimulus).

In contrast to reinforcers (positive and negative), there are positive and negative punishers that serve to increase or decrease the probability of a particular behavior being repeated. For example, Rachel has always had a designated driver when she decides to go out to the bar on Friday nights, but on one particular night she decides to drive herself to and from the local bar. On her way home, she gets pulled over for crossing the yellow line and is arrested for driving under the influence. Her decision and subsequent behavior to drink and drive resulted in a painful and unpleasant consequence: an arrest (a positive punishment).

This last scenario is an example of negative punishment. Mark’s mom decides to buy him a new car but tells him not to smoke cigarettes in the car. Despite his mom’s warning, Mark and his friends still decide to smoke cigarettes in the vehicle. His mom smells the odor when she chooses to drive his car to the grocery store one day and decides to take away Mark’s driving privileges for 2 months for not following her rules. Mark’s behavior (smoking cigarettes in the car) has now been negatively punished (removal of driving privileges).

Similar to differential association, there are modalities for differential reinforcement; more specifically, rewards that are higher in value and/or are greater in number are more likely to increase the chances that a behavior will occur and be repeated. Akers clarified that the reinforcement process does not necessarily occur in an either–or fashion but instead operates according to a quantitative law of effect wherein the behaviors that occur most frequently and are highly reinforced are chosen in favor of alternative behaviors.

VI. Imitation

Imitation is perhaps the least complex of the four dimensions of Akers’s social learning theory. Imitation occurs when an individual engages in a behavior that is modeled on or follows his or her observation of another individual’s behavior. An individual can observe the behavior of potential models either directly or indirectly (e.g., through the media). Furthermore, the characteristics of the models themselves, the behavior itself, and the observed consequences of the behavior all affect the probability that an individual will imitate the behavior. The process of imitation is often referred to as vicarious reinforcement (Bandura, 1977). Baldwin and Baldwin (1981) provided a concise summary of this process:

Observers tend to imitate modeled behavior if they like or respect the model, see the model receive reinforcement, see the model give off signs of pleasure, or are in an environment where imitating the model’s performance is reinforced. . . . Inverse imitation is common when an observer does not like the model, sees the model get punished, or is in an environment where conformity is being punished. (p. 187)

Although social learning theory maintains that the process of imitation occurs throughout an individual’s life, Akers has argued that imitation is most salient in the initial acquisition and performance of a novel or new behavior. Thus, an individual’s decision to engage in crime or deviance after watching a violent television show for the first time or observing his friends attack another peer for the first time provides the key social context in which imitation can occur. Nevertheless, the process of imitation is still assumed to exert an effect in maintaining or desisting from a given behavior.

VII. Testing Social Learning Theory

Although full empirical tests of all of the dimensions of Akers’s social learning theory did not emerge in the literature until the late 1970s, early research, such as Sutherland’s (1937) qualitative study of professional theft and Cressey’s (1953) well-known research on apprehended embezzlers, provided preliminary support for differential association (e.g., also offering support for social learning). Following these seminal studies, research now spanning more than five decades has continued to demonstrate varying levels of support for the various components of social learning theory, and the evidence is rather robust (see Akers & Jensen, 2006). There are far too many studies to make an attempt to list or discuss each individually; therefore, the following discussion is limited to noting the findings of some of the most recognizable and comprehensive tests of Akers’s social learning theory performed by Akers and his associates.

Akers has tested his own theory with a number of scholars over the years across a variety of samples and on a range of behaviors from minor deviance to serious criminal behavior, and this research can best be summarized in terms of four projects: (1) the Boys Town study, (2) the Iowa study, (3) the elderly drinking study, and (4) the rape and sexual coercion study. The first of these projects, and by far the most well-known and cited, is the Boys Town study (for a review, see Akers & Jensen, 2006). This research project involved primary collection of survey data from approximately 3,000 students in Grades 7 through 12 in eight communities in the Midwest. The majority of the survey questions focused on adolescent substance use and abuse, but it was also the first survey that included questions that permitted Akers and his associates (Akers et al., 1979) to fully test the four components of social learning theory.

The results of the studies relying on the Boys Town data provided overwhelming support for Akers’s social learning theory, including each of its four main sets of variables of differential association, definitions, differential reinforcement, and imitation. The multivariate results indicated that greater than half of the total variance in the frequency of drinking alcohol (R2 = .54) and more than two thirds of the variance in marijuana use (R2 = .68) were explained by the social learning variables. The social learning variables also affected the probability that the adolescent who began to use substances would move on to more serious involvement in drugs and alcohol. Not only did the social learning variables yield a large cumulative effect on explaining substance use, but also each of the four elements exerted a substantial independent effect on the dependent variable (with the exception of imitation). The more modest results found for the effect of imitation on substance use was not surprising considering the hypothesized interrelationships among the social learning variables. Also, imitation is expected to play a more important role in initiating use (first use) versus having a strong effect on the frequency or maintenance of use. Lanza-Kaduce, Akers, Krohn, and Radosevich (1984) also demonstrated that the social learning variables were significantly correlated with the termination of alcohol, marijuana, and hard drug use, with cessation being related to a preponderance of non-using associations, aversive drug experiences, negative social sanctions, exposure to abstinence models, and definitions unfavorable to continued use of each of these substances.

The second research project, the Iowa study, was a 5-year longitudinal examination of smoking among junior and senior high school students in Muscatine, Iowa (for a review, see Akers & Jensen, 2006). Spear and Akers (1988) provided the initial test of social learning theory on the first wave (year) of the Iowa data in an attempt to replicate the findings of the Boys Town study. The results of the cross-sectional analysis revealed nearly identical results among the youth in the Iowa study as was previously found in the Boys Town study. Once again, the social learning variables explained over half of the variance in self-reported smoking, and each of the social learning variables had a rather strong independent effect on the outcome (with the exception of imitation). Additional evidence provided by Akers (1998) illustrated the substantial influence of the adolescents’ parents and peers on their behavior. When neither of the parents or friends smoked, there was a very high probability that the adolescent abstained from smoking, and virtually none of these youth reported being regular smokers. In contrast, when the adolescent’s parents and peers smoked, more than 3 out of every 4 of these youth reported having smoked, and nearly half reported being regular smokers.

The longitudinal analysis of the Iowa data also provided support for social learning theory. Path models constructed using the first 3 years of data indicated that the direct and indirect effects of the social learning variables explained approximately 3% of the variance in predicting who would be a smoker in Year 3 if that individual had not reported being a smoker in either of the 2 prior years. Although this evidence was relatively weak, stronger results were found for the ability of the social learning variables to predict the continuation and the cessation of smoking by the third year (approximately 41% explained variance; Krohn, Skinner, Massey, & Akers, 1985). Akers and Lee (1996) also provided longitudinal support for the social learning variables’ capacity to predict the frequency of smoking using the complete 5 years of data from the Iowa study and revealed some reciprocal effects for smoking behavior on the social learning variables.

The third project was a 4-year longitudinal study of the frequency of alcohol use and problem drinking among a large sample of elderly respondents in four communities in Florida and New Jersey (for a review, see Akers & Jensen, 2006). Similar to the results of the Boys Town and Iowa studies, which examined substance use among adolescents, the multivariate results in this study of elderly individuals also demonstrated significant effects for the social learning variables as predictors of the frequency of alcohol use and problem drinking. The social learning process accounted for more than 50% of the explained variance in self-reported elderly alcohol use/abuse.

The last project by Akers and his associates reviewed here is a study of rape and sexual coercion among two samples of college men (Boeringer, Shehan, & Akers, 1991). The findings in these studies also mirrored the results of the previous studies by Akers and his associates, with the social learning variables exerting moderate to strong effects on self-reported use of nonphysical coercion in sex in addition to predicting rape and rape proclivity (i.e., the readiness to rape). Although Akers and his associates have continued to test social learning theory to various degrees using dependent variables such as adolescent alcohol and drug use (Hwang & Akers, 2003), cross-national homicide rates (Akers & Jensen, 2006), and even terrorism (Akers & Silverman, 2004), the findings from the classic studies just reviewed clearly identify the strength of the empirical status of social learning theory.

VIII. Social Structure and Social Learning: Theoretical Assumptions and Preliminary Evidence

Akers’s social learning theory has explained a considerable amount of the variation in criminal and deviant behavior at the individual level (see Akers & Jensen, 2006), and Akers (1998) recently extended it to posit an explanation for the variation in crime at the macrolevel. Akers’s social structure and social learning (SSSL) theory hypothesizes that there are social structural factors that have an indirect effect on individuals’ behavior. The indirect effect hypothesis is guided by the assumption that the effect of these social structural factors is operating through the social learning variables (i.e., differential association, definitions, differential reinforcement, and imitation) that have a direct effect on individuals’ decisions to engage in crime or deviance. Akers (1998; Akers & Sellers, 2004, p. 91) identified four specific domains of social structure wherein the social learning process can operate:

- Differential social organization refers to the structural correlates of crime in the community or society that affect the rates of crime and delinquency, including age composition, population density, and other attributes that lean societies, communities, and other social systems “toward relatively high or relatively low crime rates” (Akers, 1998, p. 332).

- Differential location in the social structure refers to sociodemographic characteristics of individuals and social groups that indicate their niches within the larger social structure. Class, gender, race and ethnicity, marital status, and age locate the positions and standing of persons and their roles, groups, or social categories in the overall social structure.

- Theoretically defined structural variables refer to anomie, class oppression, social disorganization, group conflict, patriarchy, and other concepts that have been used in one or more theories to identify criminogenic conditions of societies, communities, or groups.

- Differential social location refers to individuals’ membership in and relationship to primary, secondary, and reference groups such as the family, friendship/peer groups, leisure groups, colleagues, and work groups.

With attention to these social structural domains, Akers contended that the differential social organization of society and community and the differential locations of individuals within the social structure (i.e., individuals’ gender, race, class, religious affiliation, etc.) provide the context in which learning occurs (Akers & Sellers, 2004, p. 91). Individuals’ decisions to engage in crime/deviance are thus a function of the environment wherein the learning takes place and the individuals’ exposure to deviant peers and attitudes, possession of definitions favorable to the commission of criminal or deviant acts, and interactions with deviant models. Stated in terms of a causal process, if the social learning variables mediate social structural effects on crime as hypothesized, then (a) the social structural variables should exhibit direct effects on the social learning variables; (b) the social structural variables should exert direct effects on the dependent variable; and (c) once the social learning variables are included in the model, these variables should demonstrate strong independent effects on the dependent variable, and the social structural variables should no longer exhibit direct effects on the dependent variable, or at least their direct effects should be substantially reduced.

Considering the relative novelty of Akers’s proposed social structure and social learning theory, only a handful of studies thus far have attempted to examine its theoretical assumptions and/or its mediation hypothesis. However, the few preliminary studies to date have demonstrated positive findings in support of social structure and social learning for delinquency and substance use, elderly alcohol abuse, rape, violence, binge drinking by college students, and variation in cross-national homicide rates (Akers & Jensen, 2006). Yet, despite the consistency of positive preliminary findings in support of Akers’s social structure and social learning theory, there are some non-supportive findings, and it is still too soon to make a definitive statement that social learning is the primary mediating force in the association between social structure and crime/deviance. Nevertheless, these few studies provide a suitable benchmark against which future studies testing the theory can build upon and improve.

IX. Future Directions

The future of social learning theory lies along three paths. First, there will continue to be further and more accurate tests of social learning at the micro- or process level (i.e., at the level of differences across individuals), including measures of variables from other criminological theories, and these studies will use better measures of all of the central concepts of the theory. Having said this, it is not likely that the empirical findings will be much different from the research so far, but these future studies should continue to include more research on social leaning explanations of the most serious and violent criminal behavior as well as white-collar and corporate crime.

Second, there is need for continued development and testing of the SSSL model, again using better measures. A very promising direction that this could take would follow the lead of Jensen and Akers (2003, 2006) to extend the basic social learning principles and the SSSL model “globally” to the most macrolevel. Structural theories at that level are more apt to be valid the more they reference or incorporate the most valid principles found at the individual level, and those are social learning principles.

Third, social learning principles will continue to be applied in cognitive–behavioral (Cullen, Wright, Gendreau, &Andrews, 2003) prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and correctional programs and otherwise provide some theoretical underpinning for social policy. Research on the application and evaluations of such programs have thus far found them to be at least moderately effective (and usually more effective than alternative programs), but there are still many unanswered questions about the feasibility and effectiveness of programs designed around social learning theory.

Future research along all of these lines is also more likely to be in the form of longitudinal studies over the life course and to be cross-cultural studies of the empirical validity of the theory in different societies. If social learning is truly a general theory, then it should have applicability to the explanation and control of crime and deviance not only in American and Western societies but also societies around the world. There have already been some cross-cultural studies supporting the social learning theory (see, e.g., Hwang &Akers, 2003; Miller, Jennings, Alvarez-Rivera, & Miller, 2008), but much more research needs to examine both how well the theory holds up in different societies and on how much variation there is in the effects of the social learning variables in different cultures.

X. Conclusion

The purpose of this research paper was to provide a historical overview of the theoretical development of Akers’s social learning theory, review the seminal research testing the general theory, and discuss the recently proposed macrolevel version of social learning theory (i.e., social structure and social learning), as well as offer suggestions of where future research may wish to proceed in order to further advance the status of the theory. What is clear from the research evidence presented in this research paper, along with a number of studies that have not been specifically mentioned or discussed in this research paper (for a review, see Akers & Jensen, 2006), is that social learning has rightfully earned its place as a general theory of crime and deviance. One theorist has referred to it (along with control and strain theories) as constituting the “core” of contemporary criminological theory (Cullen, Wright, & Blevins, 2006). The theory has been rigorously tested a number of times, not only by the theorist himself but also by other influential criminologists and sociologists; it has been widely cited in the scholarly literature and in textbooks; it is a common topic covered in a variety of undergraduate and graduate courses; and it provides a basis for sound policy and practice.

Ultimately, the task levied at any general theory of crime and deviance is that it should be able to explain crime/deviance across crime/deviance type, time, place, culture, and context. Therefore, if past behavior is the best predictor of future behavior, then the expectation is that social learning theory will continue to demonstrate its generalizability across these various dimensions and that future tests of Akers’s SSSL theory will also garner support as a macrolevel explanation of crime. Yet these outcomes are indeed open to debate. No theory can account for all variations in criminal behavior. Only through the process of continuing to subject the theory and its macrolevel version to rigorous and sound empirical tests in sociology and criminology can it be determined how much the theory can account for on its own and in comparison to other theories.

- In their reformulation of the theory, Burgess and Akers chose to omit Sutherland’s ninth principle.

References:

- Akers, R. L. (1968). Problems in the sociology of deviance: Social definitions and behavior. Social Forces, 46, 455–465.

- Akers, R. L. (1973). Deviant behavior: A social learning approach. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Akers, R. L. (1977). Deviant behavior: A social learning approach (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Akers, R. L. (1985). Deviant behavior: A social learning approach (3rd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Akers, R. L. (1998). Social learning and social structure: A general theory of crime and deviance. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

- Akers, R. L., & Jensen, G. F. (2006). The empirical status of social learning theory of crime and deviance: The past, present, and future. In. F. T. Cullen, J. P. Wright, & K. R. Blevins (Eds.), Taking stock: The status of criminological theory (pp. 37–76). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

- Akers, R. L., Krohn, M. D., Lanza-Kaduce, L., & Radosevich, M. (1979). Social learning and deviant behavior: A specific test of a general theory. American Sociological Review, 44, 636–655.

- Akers, R. L., & Lee, G. (1996). A longitudinal test of social learning theory: Adolescent smoking. Journal of Drug Issues, 26, 317–343.

- Akers, R. L., & Sellers, C. S. (2004). Criminological theories: Introduction, evaluation, and application (4th ed.) Los Angeles: Roxbury.

- Akers, R. L., & Silverman, A. (2004).Toward a social learning model of violence and terrorism. In M. A. Zahn, H. H. Brownstein, & S. L. Jackson (Eds.), Violence: From theory to research (pp. 19–35). Cincinnati, OH: LexisNexis–Anderson.

- Anderson, E. (1999). Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. New York: W. W. Norton. Baldwin, J. D., & Baldwin, J. I. (1981). Beyond sociobiology. New York: Elsevier.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. New York: General Learning Press.

- Bandura, A. (1990). Mechanisms of moral disengagement. In W. Reich (Ed.), Origins of terrorism: Psychologies, ideologies, theologies, and states of mind (pp. 161–191). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Boeringer, S., Shehan, C. L., & Akers, R. L. (1991). Social contexts and social learning in sexual coercion and aggression: Assessing the contribution of fraternity membership. Family Relations, 40, 558–564.

- Burgess, R. L., & Akers, R. L. (1966). A differential association-reinforcement theory of criminal behavior. Social Problems, 14, 128–147.

- Cressey,D.R. (1953).Other people’s money. Glencoe, IL: Free Press. Cressey, D. R. (1960). Epidemiology and individual conduct: A case from criminology. Pacific Sociological Review, 3, 47–58.

- Cullen, F. T., Wright, J. P., & Blevins, K. R. (Eds.). (2006). Taking stock: The status of criminological theory. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

- Cullen, F. T., Wright, J. P., Gendreau, P., &Andrews, D. A. (2003). What correctional treatment can tell us about criminological theory: Implications for social learning theory. In R. L. Akers & G. F. Jensen (Eds.), Advances in criminological theory: Vol. 11. Social learning theory and the explanation of crime: A guide for the new century (pp. 339–362). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

- Hwang, S., &Akers, R. L. (2003). Substance use by Korean adolescents: A cross-cultural test of social learning, social bonding, and self-control theories. In R. L. Akers & G. F. Jensen (Eds.), Advances in criminological theory: Vol. 11. Social learning theory and the explanation of crime: A guide for the new century (pp. 39–64). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

- Jensen, G. F. (2003). Gender variation in delinquency: Self-images, beliefs, and peers as mediating mechanisms. In R. L. Akers & G. F. Jensen (Eds.), Advances in criminological theory: Vol. 11. Social learning theory and the explanation of crime (pp. 151–178). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

- Krohn, M. D., Skinner, W. F., Massey, J. L., & Akers, R. L. (1985). Social learning theory and adolescent cigarette smoking. Social Problems, 32, 455–473.

- Lanza-Kaduce, L., Akers, R. L., Krohn, M. D., & Radosevich, M. (1984). Cessation of alcohol and drug use among adolescents: A social learning model. Deviant Behavior, 5, 79–96.

- Miller, H.V., Jennings, W. G., Alvarez-Rivera, L. L., &Miller, J.M. (2008). Explaining substance use among Puerto Rican adolescents: A partial test of social learning theory. Journal of Drug Issues, 38, 261–284.

- Spear, S., & Akers, R. L. (1988). Social learning variables and the risk of habitual smoking among adolescents: The Muscatine study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 4, 336–348.

- Sutherland, E. H. (1937). The professional thief. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Sutherland, E. H. (1947). Principles of criminology (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott.

- Sykes, G., & Matza, D. (1957). Techniques of neutralization: A theory of delinquency. American Journal of Sociology, 22, 664–670.

- Warr, M. (2002). Companions in crime: The social aspects of criminal conduct. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Social Learning Theory

Introduction, general treatments.

- Differential Association

- Social Learning

- Social Structure and Social Learning

- Critiques Against Social Learning Theory

- The Role of Peers, Family, and Community in Social Learning

- Social Learning–Based Intervention Strategies

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Campus Crime

- Cultural Theories

- Edwin H. Sutherland

- Longitudinal Research in Criminology

- Mass Media, Crime, and Justice

- Nature Versus Nurture

- Offense Specialization/Expertise

- Rehabilitation

- Ruth Rosner Kornhauser

- Situational Action Theory

- Social Control Theory

- Substance Use and Abuse

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Education Programs in Prison

- Juvenile Justice Professionals' Perceptions of Youth

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Social Learning Theory by Thomas Holt LAST REVIEWED: 14 December 2009 LAST MODIFIED: 14 December 2009 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195396607-0002

Social learning theory has had a distinct and lasting impact on the field of criminology. This framework evolved from Edwin Sutherland’s Differential Association in the 1940s, which argued that crime is learned through interactions with intimate peers where individuals acquire definitions that support or refute the violation of law. This theory was revised in Burgess and Akers 1966 (see Social Learning ) to become a Differential Association-Reinforcement model recognizing the impact of peer attitudes and reactions to delinquency. The theory was further revised in the 1970s and 1980s to become a social learning model developed by Ronald Akers. This model builds from the previous work by recognizing the significance of delinquent peers, differential definitions of and reinforcement for offending behaviors, and the influence of imitation of peer behavior. Finally, Akers adapted the model in 1998 to become a macro-level model of delinquency and crime by arguing that social learning mediates the influence of structural factors on offending. This perspective provides a distinct framework to understand the influence of human agency, social forces, and peers on behavior.

Akers and Jensen 2003 provides an excellent theoretical and empirical assessment of multiple facets of the micro and macro social learning models. Akers and Jensen 2006 provides a detailed overview of the research on social learning in 2006 and find that this theory is generally supported when various individual and aggregate-level variables are included in models with social learning constructs. These two works are appropriate for graduates and researchers, while Akers and Sellers 2008 provides a comprehensive and accessible chapter on social learning theory that would be appropriate for graduates and undergraduates alike. Other seminal texts on social learning theory are discussed in other sections of this bibliography.

Akers, Ronald L., and Gary F. Jensen, eds. 2003. Social learning theory and the explanation of crime: A guide for the new century . New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Significant edited volume that provides a robust discussion of social learning theory from multiple authors, including empirical and theoretical discussions of a variety of components of both social learning and the larger social structure and social learning models.

Akers, Ronald L., and Gary F. Jensen. 2006. The empirical status of social learning theory of crime and deviance: The past, present, and future. In Taking stock: The status of criminological theory . Edited by Francis T. Cullen, John Paul Wright, and Kristie R. Blevins, 37–76. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Summary of the body of social learning research, including support for and critiques of this theory, as well as future areas of exploration.

Akers, Ronald L., and Christine S. Sellers. 2008. Criminological theories: Introduction, evaluation, and application . New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

Provides a robust discussion of social learning theory and its evolution over time, along with a variety of other criminological theories.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Criminology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Active Offender Research

- Adler, Freda

- Adversarial System of Justice

- Adverse Childhood Experiences

- Aging Prison Population, The

- Airport and Airline Security

- Alcohol and Drug Prohibition

- Alcohol Use, Policy and Crime

- Alt-Right Gangs and White Power Youth Groups

- Animals, Crimes Against

- Back-End Sentencing and Parole Revocation

- Bail and Pretrial Detention

- Batterer Intervention Programs

- Bentham, Jeremy

- Big Data and Communities and Crime

- Biosocial Criminology

- Black's Theory of Law and Social Control

- Blumstein, Alfred

- Boot Camps and Shock Incarceration Programs

- Burglary, Residential

- Bystander Intervention

- Capital Punishment

- Chambliss, William

- Chicago School of Criminology, The

- Child Maltreatment

- Chinese Triad Society

- Civil Protection Orders

- Collateral Consequences of Felony Conviction and Imprisonm...

- Collective Efficacy

- Commercial and Bank Robbery

- Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children

- Communicating Scientific Findings in the Courtroom

- Community Change and Crime

- Community Corrections

- Community Disadvantage and Crime

- Community-Based Justice Systems

- Community-Based Substance Use Prevention

- Comparative Criminal Justice Systems

- CompStat Models of Police Performance Management

- Confessions, False and Coerced

- Conservation Criminology

- Consumer Fraud

- Contextual Analysis of Crime

- Control Balance Theory

- Convict Criminology

- Co-Offending and the Role of Accomplices

- Corporate Crime

- Costs of Crime and Justice

- Courts, Drug

- Courts, Juvenile

- Courts, Mental Health

- Courts, Problem-Solving

- Crime and Justice in Latin America

- Crime, Campus

- Crime Control Policy

- Crime Control, Politics of

- Crime, (In)Security, and Islam

- Crime Prevention, Delinquency and

- Crime Prevention, Situational

- Crime Prevention, Voluntary Organizations and

- Crime Trends

- Crime Victims' Rights Movement

- Criminal Career Research

- Criminal Decision Making, Emotions in

- Criminal Justice Data Sources

- Criminal Justice Ethics

- Criminal Justice Fines and Fees

- Criminal Justice Reform, Politics of

- Criminal Justice System, Discretion in the

- Criminal Records

- Criminal Retaliation

- Criminal Talk

- Criminology and Political Science

- Criminology of Genocide, The

- Critical Criminology

- Cross-National Crime

- Cross-Sectional Research Designs in Criminology and Crimin...

- Cultural Criminology

- Cybercrime Investigations and Prosecutions

- Cycle of Violence

- Deadly Force

- Defense Counsel

- Defining "Success" in Corrections and Reentry

- Developmental and Life-Course Criminology

- Digital Piracy

- Driving and Traffic Offenses

- Drug Control

- Drug Trafficking, International

- Drugs and Crime

- Elder Abuse

- Electronically Monitored Home Confinement

- Employee Theft

- Environmental Crime and Justice

- Experimental Criminology

- Family Violence

- Fear of Crime and Perceived Risk

- Felon Disenfranchisement

- Feminist Theories

- Feminist Victimization Theories

- Fencing and Stolen Goods Markets

- Firearms and Violence

- Forensic Science

- For-Profit Private Prisons and the Criminal Justice–Indust...

- Gangs, Peers, and Co-offending

- Gender and Crime

- Gendered Crime Pathways

- General Opportunity Victimization Theories

- Genetics, Environment, and Crime

- Green Criminology

- Halfway Houses

- Harm Reduction and Risky Behaviors

- Hate Crime Legislation

- Healthcare Fraud

- Hirschi, Travis

- History of Crime in the United Kingdom

- History of Criminology

- Homelessness and Crime

- Homicide Victimization

- Honor Cultures and Violence

- Hot Spots Policing

- Human Rights

- Human Trafficking

- Identity Theft

- Immigration, Crime, and Justice

- Incarceration, Mass

- Incarceration, Public Health Effects of

- Income Tax Evasion

- Indigenous Criminology

- Institutional Anomie Theory

- Integrated Theory

- Intermediate Sanctions

- Interpersonal Violence, Historical Patterns of

- Interrogation

- Intimate Partner Violence, Criminological Perspectives on

- Intimate Partner Violence, Police Responses to

- Investigation, Criminal

- Juvenile Delinquency

- Juvenile Justice System, The

- Juvenile Waivers

- Kornhauser, Ruth Rosner

- Labeling Theory

- Labor Markets and Crime

- Land Use and Crime

- Lead and Crime

- LGBTQ Intimate Partner Violence

- LGBTQ People in Prison

- Life Without Parole Sentencing

- Local Institutions and Neighborhood Crime

- Lombroso, Cesare

- Mandatory Minimum Sentencing

- Mapping and Spatial Analysis of Crime, The

- Measuring Crime

- Mediation and Dispute Resolution Programs

- Mental Health and Crime

- Merton, Robert K.

- Meta-analysis in Criminology

- Middle-Class Crime and Criminality

- Migrant Detention and Incarceration

- Mixed Methods Research in Criminology

- Money Laundering

- Motor Vehicle Theft

- Multi-Level Marketing Scams

- Murder, Serial

- Narrative Criminology

- National Deviancy Symposia, The

- Neighborhood Disorder

- Neutralization Theory

- New Penology, The

- Offender Decision-Making and Motivation

- Organized Crime

- Outlaw Motorcycle Clubs

- Panel Methods in Criminology

- Peacemaking Criminology

- Peer Networks and Delinquency

- Perceptions of Youth, Juvenile Justice Professionals'

- Performance Measurement and Accountability Systems

- Personality and Trait Theories of Crime

- Persons with a Mental Illness, Police Encounters with

- Phenomenological Theories of Crime

- Plea Bargaining

- Police Administration

- Police Cooperation, International

- Police Discretion

- Police Effectiveness

- Police History

- Police Militarization

- Police Misconduct

- Police, Race and the

- Police Use of Force

- Police, Violence against the

- Policing and Law Enforcement

- Policing, Body-Worn Cameras and

- Policing, Broken Windows

- Policing, Community and Problem-Oriented

- Policing Cybercrime

- Policing, Evidence-Based

- Policing, Intelligence-Led

- Policing, Privatization of

- Policing, Proactive

- Policing, School

- Policing, Stop-and-Frisk

- Policing, Third Party

- Polyvictimization

- Positivist Criminology

- Pretrial Detention, Alternatives to

- Pretrial Diversion

- Prison Administration

- Prison Classification

- Prison, Disciplinary Segregation in

- Prison Education Exchange Programs

- Prison Gangs and Subculture

- Prison History

- Prison Labor

- Prison Visitation

- Prisoner Reentry

- Prisons and Jails

- Prisons, HIV in

- Private Security

- Probation Revocation

- Procedural Justice

- Property Crime

- Prosecution and Courts

- Prostitution

- Psychiatry, Psychology, and Crime: Historical and Current ...

- Psychology and Crime

- Public Criminology

- Public Opinion, Crime and Justice

- Public Order Crimes

- Public Social Control and Neighborhood Crime

- Punishment Justification and Goals

- Qualitative Methods in Criminology

- Queer Criminology

- Race and Sentencing Research Advancements

- Race, Ethnicity, Crime, and Justice

- Racial Threat Hypothesis

- Racial Profiling

- Rape and Sexual Assault

- Rape, Fear of

- Rational Choice Theories

- Religion and Crime

- Restorative Justice

- Risk Assessment

- Routine Activity Theories

- School Bullying

- School Crime and Violence

- School Safety, Security, and Discipline

- Search Warrants

- Seasonality and Crime

- Self-Control, The General Theory:

- Self-Report Crime Surveys

- Sentencing Enhancements

- Sentencing, Evidence-Based

- Sentencing Guidelines

- Sentencing Policy

- Sex Offender Policies and Legislation

- Sex Trafficking

- Sexual Revictimization

- Snitching and Use of Criminal Informants

- Social and Intellectual Context of Criminology, The

- Social Construction of Crime, The

- Social Control of Tobacco Use

- Social Disorganization

- Social Ecology of Crime

- Social Learning Theory

- Social Networks

- Social Threat and Social Control

- Solitary Confinement

- South Africa, Crime and Justice in

- Sport Mega-Events Security

- Stalking and Harassment

- State Crime

- State Dependence and Population Heterogeneity in Theories ...

- Strain Theories

- Street Code

- Street Robbery

- Surveillance, Public and Private

- Sutherland, Edwin H.

- Technology and the Criminal Justice System

- Technology, Criminal Use of

- Terrorism and Hate Crime

- Terrorism, Criminological Explanations for

- Testimony, Eyewitness

- Therapeutic Jurisprudence

- Trajectory Methods in Criminology

- Transnational Crime

- Truth-In-Sentencing

- Urban Politics and Crime

- US War on Terrorism, Legal Perspectives on the

- Victim Impact Statements

- Victimization, Adolescent

- Victimization, Biosocial Theories of

- Victimization Patterns and Trends

- Victimization, Repeat

- Victimization, Vicarious and Related Forms of Secondary Tr...

- Victimless Crime

- Victim-Offender Overlap, The

- Violence Against Women

- Violence, Youth

- Violent Crime

- White-Collar Crime

- White-Collar Crime, The Global Financial Crisis and

- White-Collar Crime, Women and

- Wilson, James Q.

- Wolfgang, Marvin

- Women, Girls, and Reentry

- Wrongful Conviction

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|109.248.223.228]

- 109.248.223.228

Social Learning Theory in Criminology Research Paper

Introduction, introducing the theory, evolution of the theory, application of the theory.

Criminology as a distinct science evolves and acquires new approaches, research data, and theories. The numerous methods applicable to criminology clarify a lot of questions concerning the behavior of a criminal or the influence of diverse psychological and sociological factors on the crime rates. During the past several decades, there has been a significant advancement in the research of the field of criminology and its theoretical background.

Social learning theory is one of the most influential psychological theories; it is widely used for the identification of behavioral patterns of criminals. A correct substantial approach applied to a crime analysis might be a crucial tool for the detection of the roots of the problem and possible ways of preventing criminal behavior in others. The paper concentrates on the history of the introduction of the social learning theory to science, its evolution over the years, and its possible application to the analysis of a recent criminal event.

A social learning theory was introduced to criminology by Robert L. Burgess and Ronald L. Akers from the University of Washington in 1966. Their study entitled A differential association-reinforcement theory of criminal behavior was based on the previous advancement in the field, which Sutherland contributed to in 1947 (Burgess & Akers, 1966). Sutherland’s idea of a differential association theory was developed and supported by several scholars. However, Burges and Akers were the first who empirically studied the theory and connected the differential association theory with a sociological pattern.

Sutherland’s idea that “criminal behavior is learned as any behavior is learned” was elaborated on and applied to the analysis of the crime rates and their roots (Burgess & Akers, 1966, p. 128). Thus, the social learning theory grounds on the idea of differential association-reinforcement and attempts to explain criminal behavior not individually but in the connection to environmental influences.

The authors of the theory provide a broader view on the issue of behavioral association and ask specific questions to be answered by their contemporary criminology. Those questions concern the reasons why particular individuals being in the same environment as many others acquire delinquent behavior. To provide answers, the criminologists reformulated the primary points of Sutherland’s theory through the processes of conditioned reinforcement and stimulus discrimination (Burgess & Akers, 1966).

The main components of the approach constitute the following ideas: criminal behavior is learned, it is absorbed in nonsocial and social situations of reinforcement, criminal behavior patterns are acquired within the influential groups. Also, the frequency of the specific behaviors learned depends on the “reinforcers,” criminal behavior is learned when “such behavior is more highly reinforced” than a noncriminal one (Burgess & Akers, 1966, p. 134). Finally, deviant behavior learning relates to the frequency and amount of reinforcing influences.

The theory was developed and tested during the following years by other criminologists, as well as by the authors. Akers and colleagues later applied it to study the behavioral patterns among drug and alcohol users, the results of which proved the validity of the theory. This study provided prospects for further studies and the use of the social learning theory for other abnormal behaviors (Akers, Krohn, Lanza-Kaduce, & Radosevich, 1979).

It remains relevant in the present and is widely used in criminology as one of the ideas most capable of identifying the connections between criminal inclinations and the environment in which a criminal exists. One of the latest studies applies social structure to the social learning theory and provides a broad overview of the preventive interventions (Nicholson & Higgins, 2017). Due to the contribution of many scholars investigating the issue since the 1960s, the theory evolved into a powerful tool enabling the productive work of criminologists.

The social learning theory may be applied to the criminal events in the USA. The massive shootings that shook several US cities have a wave character. A mass shooting incident that took place in Chicago on October 29 took the lives of five people and left a dozen hurt, according to CNN (Baldacci, 2018). The actions of a criminal might be analyzed according to the social learning theory based on the preceding events of the same character.

The occasions mass shooting periodically occur in Chicago during the past several years, increasing the crime rates in the city (Baldacci, 2018). The modern world of globalization, where an environment influencing an individual reaches far beyond his or her spatial location and embraces informational impacts, presents a broader perspective on the application of the theory. That is why the theory is incapable of introducing an effective preventive technique in such circumstances. A person aware of a crime incident might be influenced by it and learn the same behavior. However, the discussed theory does not give precise answers to the questions of why these crimes happen in particular time periods and what their frequency depends on.

Summarizing the discussion, it is essential to underline that appropriate application of a particular theory to a crime might provide numerous opportunities, as well as limitations, to understanding the driving forces of deviant behavior.

Such understanding allows retrieving the core relation between people’s behavioral patterns and their crime inclination. When applied to criminology, social learning theory determines basic components of deviant behavior, which is learned (as any other behavior is learned) through environmental influences and reinforcements. Although the method does not provide answers to all the questions concerning a crime, thus justifying the importance of other theories, it contributes to the development of preventive interventions capable of decreasing crime rates.

Akers, R. L., Krohn, M. D., Lanza-Kaduce, L., & Radosevich, M. (1979). Social learning and deviant behavior: A specific test of a general theory. American Sociological Review, 44 (4), 636-655. Web.

Baldacci, M. (2018). 5 die, dozens hurt in Chicago weekend shootings, police say . CNN. Web.

Burgess, R. L., & Akers, R. L. (1966). A differential association-reinforcement theory of criminal behavior. Social Problems, 14(2), 128-147. Web.

Nicholson, J., & Higgins, G. E. (2017). Social structure social learning theory: Preventing crime and violence. In B. Teasdale & M. S. Bradley (Eds.), Preventing crime and violence (pp. 11-20). New York, NY: Springer. Web.

- Serial Murders Explained by Psychological Theory

- Punishment from the Sociological Standpoint

- Advertising’s Capacity to Affect Perceptions

- Criminal Behavior: Criminology Theories

- Analysis of the Differential Association Theory

- Bernie Madoff Ponzi's Crime Scheme

- Public Shaming and Justice

- Crime Theories Differentiating Criminal Behavior

- Social Disorganization Theory in Criminology

- Feminist Theory of Delinquency by Chesney-Lind

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, May 26). Social Learning Theory in Criminology. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-learning-theory-in-criminology/

"Social Learning Theory in Criminology." IvyPanda , 26 May 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/social-learning-theory-in-criminology/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Social Learning Theory in Criminology'. 26 May.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Social Learning Theory in Criminology." May 26, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-learning-theory-in-criminology/.

1. IvyPanda . "Social Learning Theory in Criminology." May 26, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-learning-theory-in-criminology/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Social Learning Theory in Criminology." May 26, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-learning-theory-in-criminology/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

5.4 Social Learning and Motivational Theories of Crime

In Chapter 4 , we discussed social learning theory from a sociological perspective. In this section, we will examine social learning theory from a psychological perspective. This involves also diving deeper into what motivates a person to behave in a certain way. Crime prevention practices tend to center more on rational thought and the belief that people understand punishment is bad, so they will not complete the act. However, when criminal behavior occurs because the person committing the act thinks of it more in terms of the positive reinforcement they receive from committing the crime based on what they have seen through observation and action during the course of their lives, that goes against the way prevention had been planned.

5.4.1 Social Learning Theory

Canadian-American psychologist Albert Bandura (1974) defined observational learning as the process by which “people convert future consequences into motivations for behavior.” In other words, people learn by watching others and observing the results of their actions. The unique part of Bandura’s theory was that he argued observational learning did not require direct reinforcement. This is because humans are capable of learning vicariously through the experiences of others or even through their own imaginations.

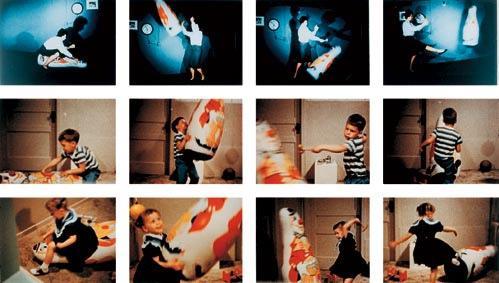

Bandura centered his research on learning aggression. His famous Bobo Doll study involved children who watched an adult attack a plastic clown punching bag named “Bobo,” and then they were rewarded with sweets and drinks for their behavior. Later when the children were in the room with other toys, they chose to attack the doll in a similar fashion as the adults (figure 5.4).

Culture & Social Learning

Given that this is a criminological theory class, I can’t reiterate the following enough. So, you’ll keep seeing the following:

Theory is a statement about how something affects something else.

Scientific theory states how something empirical (an independent variable) affects something else empirical (the dependent variable).

Something is empirical if you can hear, see, touch, smell, or taste it.