- Get started with computers

- Learn Microsoft Office

- Apply for a job

- Improve my work skills

- Design nice-looking docs

- Getting Started

- Smartphones & Tablets

- Typing Tutorial

- Online Learning

- Basic Internet Skills

- Online Safety

- Social Media

- Zoom Basics

- Google Docs

- Google Sheets

- Career Planning

- Resume Writing

- Cover Letters

- Job Search and Networking

- Business Communication

- Entrepreneurship 101

- Careers without College

- Job Hunt for Today

- 3D Printing

- Freelancing 101

- Personal Finance

- Sharing Economy

- Decision-Making

- Graphic Design

- Photography

- Image Editing

- Learning WordPress

- Language Learning

- Critical Thinking

- For Educators

- Translations

- Staff Picks

- English expand_more expand_less

Google Classroom - Creating Assignments and Materials

Google classroom -, creating assignments and materials, google classroom creating assignments and materials.

Google Classroom: Creating Assignments and Materials

Lesson 2: creating assignments and materials.

/en/google-classroom/getting-started-with-google-classroom/content/

Creating assignments and materials

Google Classroom gives you the ability to create and assign work for your students, all without having to print anything. Questions , essays , worksheets , and readings can all be distributed online and made easily available to your class. If you haven't created a class already, check out our Getting Started with Google Classroom lesson.

Watch the video below to learn more about creating assignments and materials in Google Classroom.

Creating an assignment

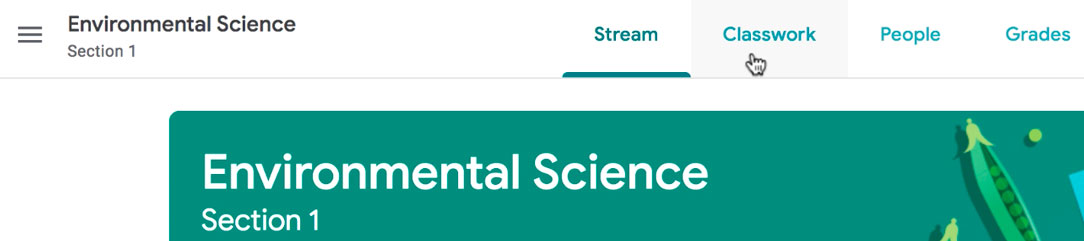

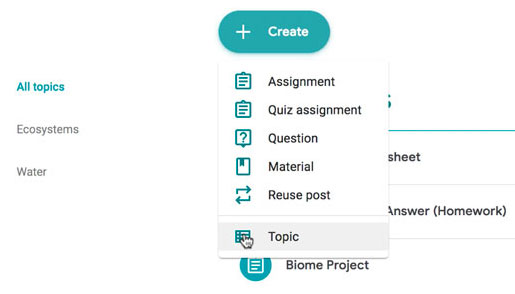

Whenever you want to create new assignments, questions, or material, you'll need to navigate to the Classwork tab.

In this tab, you can create assignments and view all current and past assignments. To create an assignment, click the Create button, then select Assignment . You can also select Question if you'd like to pose a single question to your students, or Material if you simply want to post a reading, visual, or other supplementary material.

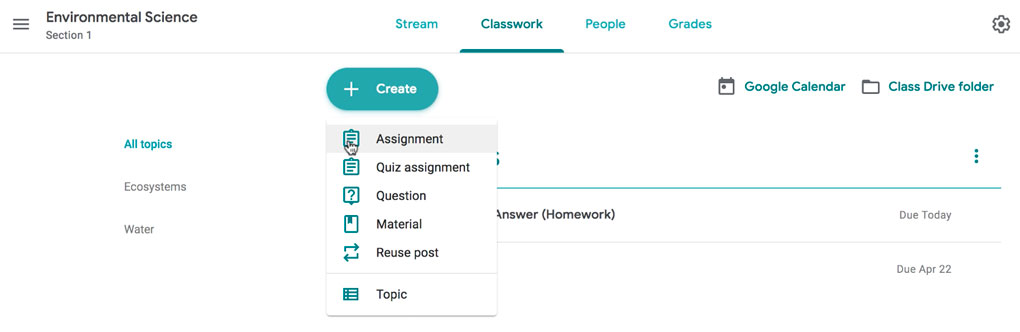

This will bring up the Assignment form. Google Classroom offers considerable flexibility and options when creating assignments.

Click the buttons in the interactive below to become familiar with the Assignment form.

This is where you'll type the title of the assignment you're creating.

Instructions

If you'd like to include instructions with your assignment, you can type them here.

Here, you can decide how many points an assignment is worth by typing the number in the form. You can also click the drop-down arrow to select Ungraded if you don't want to grade an assignment.

You can select a due date for an assignment by clicking this arrow and selecting a date from the calendar that appears. Students will have until then to submit their work.

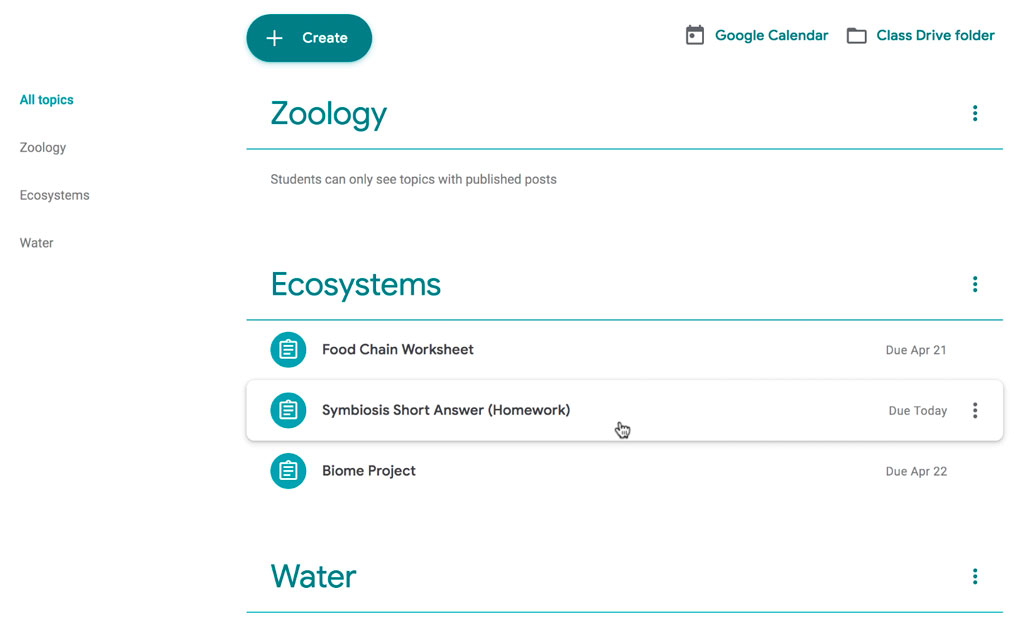

In Google Classroom, you can sort your assignments and materials into topics. This menu allows you to select an existing topic or create a new one to place an assignment under.

Attachments

You can attach files from your computer , files from Google Drive , URLs , and YouTube videos to your assignments.

Google Classroom gives you the option of sending assignments to all students or a select number .

Once you're happy with the assignment you've created, click Assign . The drop-down menu also gives you the option to Schedule an assignment if you'd like it to post it at a later date.

You can attach a rubric to help students know your expectations for the assignment and to give them feedback.

Once you've completed the form and clicked Assign , your students will receive an email notification letting them know about the assignment.

Google Classroom takes all of your assignments and automatically adds them to your Google Calendar. From the Classwork tab, you can click Google Calendar to pull this up and get a better overall view of the timeline for your assignments' due dates.

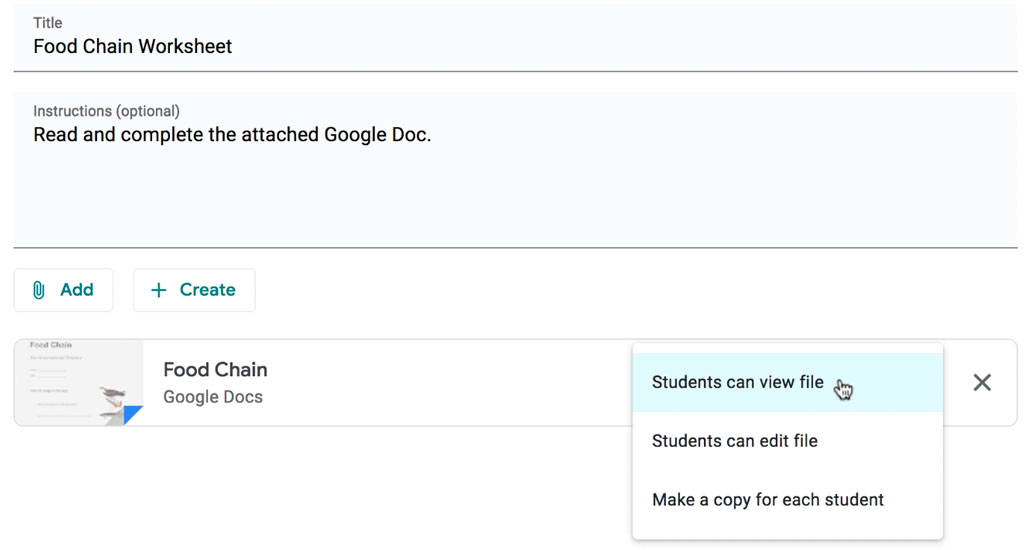

Using Google Docs with assignments

When creating an assignment, there may often be times when you want to attach a document from Google Docs. These can be helpful when providing lengthy instructions, study guides, and other material.

When attaching these types of files, you'll want to make sure to choose the correct setting for how your students can interact with it . After attaching one to an assignment, you'll find a drop-down menu with three options.

Let's take a look at when you might want to use each of these:

- Students can view file : Use this option if the file is simply something you want your students to view but not make any changes to.

- Students can edit file : This option can be helpful if you're providing a document you want your students to collaborate on or fill out collectively.

- Make a copy for each student : If you're creating a worksheet or document that you want each student to complete individually, this option will create a separate copy of the same document for every student.

Using topics

On the Classwork tab, you can use topics to sort and group your assignments and material. To create a topic, click the Create button, then select Topic .

Topics can be helpful for organizing your content into the various units you teach throughout the year. You could also use it to separate your content by type , splitting it into homework, classwork, readings, and other topic areas.

In our next lesson , we'll explore how to create quizzes and worksheets with Google Forms, further expanding how you can use Google Classroom with your students.

/en/google-classroom/using-forms-with-google-classroom/content/

for Education

- Google Classroom

- Google Workspace Admin

- Google Cloud

Gemini now has added data protection. Chat with Gemini to save time, personalize learning and inspire creativity.

Gemini now has added data protection. chat now ., easily distribute, analyze, and grade student work with assignments for your lms.

Assignments is an application for your learning management system (LMS). It helps educators save time grading and guides students to turn in their best work with originality reports — all through the collaborative power of Google Workspace for Education.

- Get started

- Explore originality reports

Bring your favorite tools together within your LMS

Make Google Docs and Google Drive compatible with your LMS

Simplify assignment management with user-friendly Google Workspace productivity tools

Built with the latest Learning Tools Interoperability (LTI) standards for robust security and easy installation in your LMS

Save time distributing and grading classwork

Distribute personalized copies of Google Drive templates and worksheets to students

Grade consistently and transparently with rubrics integrated into student work

Add rich feedback faster using the customizable comment bank

Examine student work to ensure authenticity

Compare student work against hundreds of billions of web pages and over 40 million books with originality reports

Make student-to-student comparisons on your domain-owned repository of past submissions when you sign up for the Teaching and Learning Upgrade or Google Workspace for Education Plus

Allow students to scan their own work for recommended citations up to three times

Trust in high security standards

Protect student privacy — data is owned and managed solely by you and your students

Provide an ad-free experience for all your users

Compatible with LTI version 1.1 or higher and meets rigorous compliance standards

Product demos

Experience google workspace for education in action. explore premium features in detail via step-by-step demos to get a feel for how they work in the classroom..

“Assignments enable faculty to save time on the mundane parts of grading and...spend more time on providing more personalized and relevant feedback to students.” Benjamin Hommerding , Technology Innovationist, St. Norbert College

Classroom users get the best of Assignments built-in

Find all of the same features of Assignments in your existing Classroom environment

- Learn more about Classroom

Explore resources to get up and running

Discover helpful resources to get up to speed on using Assignments and find answers to commonly asked questions.

- Visit Help Center

Get a quick overview of Assignments to help Educators learn how they can use it in their classrooms.

- Download overview

Get started guide

Start using Assignments in your courses with this step-by-step guide for instructors.

- Download guide

Teacher Center Assignments resources

Find educator tools and resources to get started with Assignments.

- Visit Teacher Center

How to use Assignments within your LMS

Watch this brief video on how Educators can use Assignments.

- Watch video

Turn on Assignments in your LMS

Contact your institution’s administrator to turn on Assignments within your LMS.

- Admin setup

Explore a suite of tools for your classroom with Google Workspace for Education

You're now viewing content for a different region..

For content more relevant to your region, we suggest:

Sign up here for updates, insights, resources, and more.

Skip to main content

- Skip to main menu

- Skip to user menu

What To Do When You Have No Idea How To Tackle A New Assignment

Published: Sep 30, 2018 By Kevin Dickinson

Your manager calls you into her office to discuss a new initiative—and its importance to the company. While she goes over the details, you smile and nod at the appropriate beats, but the whole time you’re thinking, “What does this have to do with me?” And then it hits you: Oh, no. She’s giving me the assignment?

Thing is, you have no idea how to tackle the project. None. This one is so far outside your wheelhouse , you’re not even sure you can bunt it, much less hit a home run.

But You Can

Follow the steps below and you’ll be able to tackle any new task even if you begin with no idea how. Start with step one, and work your way up to six. When you’re done, start over, and over, and over… If you bring your skills, intelligence, and determination to every stage of the process, you won’t just succeed—you’ll develop as a professional and gain valuable expertise.

Step 1. Don’t Panic

When you panic, your heart rate increases and your adrenaline spikes, drowning your senses in an unappeasable urgency. Feeling rushed, you lose focus and become even more stressed. These feelings will prompt you to multitask in a bid to ease that sense of impending crisis. This, of course, does the opposite, leading to further panic, additional stress, and more fruitless multitasking.

So don’t panic.

Take a deep breath , go for a quick walk to shake off the jitters, and remind yourself that you will succeed.

Step 2. Start With Something Small

The project is impossibly large when you look at it as a whole, and you’re tempted to freeze. Prevent stalling by starting small and easy—send out an email, set up a meeting, or outline the broad strokes and ignore the detail work. Whatever you need to do to prevent procrastination and gather momentum, do it.

Later on in the assignment, you’ll come across daunting components. Make them more manageable by breaking them into smaller steps and tackling them one at a time.

Step 3. Do Your Research

The chances are good someone, somewhere has tackled a similar task, so do your research and learn what you can. Ask around the office. Gather experience from former coworkers. Search for articles on the Internet or go to the library and find a book on the process.

Even if the information you discover doesn’t relate to the exact same work, you’ll likely be able to connect what you’ve found to your own knowledge and devise a preliminary path forward.

Step 4. Try Something

Once you’ve done your research, try something. Anything. The point is to put your research to use, and just start. And if you just start, you’ll begin making headway. Will you fail? Maybe. Will you succeed? Maybe. Either way, you’ll be making progress thanks to the next step.

Step 5. Assess Your Work

Once you’ve tried something, stop and assess your work. Does it fit within the assignment’s objective? Does it meet that objective? Is it up to your standards? What did you do correctly? What could be improved?

This is a good time to gather feedback . An outsider’s perspective will unveil qualities in your work—both negative and positive—that you’re too close to see. Taking criticism—even constructive, helpful criticism—can be difficult, but don’t take it personally. Use it to improve.

Depending on what your assessment reveals, you’ll want to do one of the following.

Step 6a. Did You Fail? Try, Try Again

Don’t look at failure as, well, failure . Remember, you had no idea what you were doing at first. To even have work to assess shows incredible progress. The knowledge you’ve gained and the lessons you’ve learned qualify as successes you can build on. Jump back to step one and try again.

Step 6b. Did You Succeed? Celebrate!

Congratulations! Whether large or small, success builds on success. The more successes you earn, the more comfortable you’ll feel, and the more likely you are to succeed again. Acknowledge your achievement, pick a new part of the assignment, and jump back to step one.

Once you’ve completed the assignment, treat yourself. Grab a cup of coffee or an after-work drink, and take a moment to consider what you’ve accomplished. Is it perfect? Nope. But you had no idea what you were doing, and you managed to tackle the project despite your lack of expertise. And next time, you’ll be able to take this experience and these steps and triumph once again!

Search for your next job now:

Back to listing

The Washington Post Jobs Newsletter

Subscribe to the latest news about DC's jobs market

Related articles

- Should You Tell Your Manager You Don't Have Enough Work to Do? This will open in a new window

- How To Manage Upward (If You Have A Bad Boss) This will open in a new window

- Are You In A Job That’s Wasting Your Time? This will open in a new window

Washington Post Jobs Recommends:

6 Tips for Looking for a Remote Job

3 Better Ways to Say “I Don’t Have Time for This Right Now”

How Successful People Write Their Self-Reviews

Ace Your Video Interview with These 6 Tips

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that they will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply —use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove their point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, they still have to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and they already know everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality they expect.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

You're signed out

Sign in to ask questions, follow content, and engage with the Community

- Canvas Instructor

- Instructor Guide

How do I create an assignment?

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

in Instructor Guide

Note: You can only embed guides in Canvas courses. Embedding on other sites is not supported.

Community Help

View our top guides and resources:.

To participate in the Instructure Community, you need to sign up or log in:

- Help Center

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Submit feedback

- Announcements

- Organize and communicate with your class

- Create assignments

Create an assignment

This article is for teachers.

When you create an assignment, you can post it immediately, save a draft, or schedule it to post at a later date. After students complete and turn in their work, you can grade and return it to the students.

Open all | Close all

Create & post assignments

When you create an assignment, you can:

- Select one or more classes

Select individual students

Add a grade category, add a grading period, change the point value, add a due date or time, add a topic, add attachments, add a rubric.

- Turn on originality reports

Go to classroom.google.com and click Sign In.

Sign in with your Google Account. For example, [email protected] or [email protected] . Learn more .

- Enter the title and any instructions.

You can continue to edit and customize your assignment. Otherwise, if you’re ready, find below to post, schedule, or save your assignment .

Select additional classes

Assignments to multiple classes go to all students in those classes.

- Create an assignment (details above).

Unless you’re selecting multiple classes, you can select individual students. You can’t select more than 100 students at a time.

- Click a student's name to select them.

Use grade categories to organize assignments. With grade categories, you and your students can find the category an assignment belongs to, such as Homework or Essays . Teachers also find the categories on the Grades page.

For more information on grade categories, go to Add a grade category to posts or Set up grading .

To organize assignments and grades into your school or district’s grading structure, create grading periods, such as quarters or semesters.

- From the menu, select a grading period.

Tip: Before adding a grading period to an assignment, create a grading period for the class first. Learn how to create or edit grading periods .

You can change the point value of an assignment or make the assignment ungraded. By default, assignments are set at 100 points.

- Under Points , click the value.

- Enter a new point value or select Ungraded .

By default, an assignment has no due date. To set a due date:

- Click a date on the calendar.

- To create a topic, click Create topic and enter a topic name.

- Click a topic in the list to select it.

Note : You can only add one topic to an assignment.

Learn more about how to add topics to the Classwork page .

- Create an assignment.

- Important: Google Drive files can be edited by co-teachers and are read-only to students. To change these share options, you can stop, limit, or change sharing .

- To add YouTube videos, an admin must turn on this option. Learn about access settings for your Google Workspace for Education account .

- You can add interactive questions to YouTube video attachments. Learn how to add interactive questions to YouTube video attachments .

- Tip: When you attach a practice set to an assignment, you can't edit it.

- If you find a message that you don’t have permission to attach a file, click Copy . Classroom makes a copy of the file to attach to the assignment and saves it to the class Drive folder.

- Students can view file —All students can read the file, but not edit it.

- Students can edit file —All students share the same file and can make changes to it.

Note : This option is only available before you post an assignment.

Use an add-on

For instructions, go to Use add-ons in Classroom

For instructions, go to Create or reuse a rubric for an assignment .

For instructions, go to Turn on originality reports .

You can post an assignment immediately, or schedule it to post later. If you don’t want to post it yet, you can save it as a draft. To find scheduled and drafted assignments, click Classwork .

Post an assignment

- Follow the steps above to create an assignment.

- Click Assign to immediately post the assignment.

Schedule the assignment to post later

Scheduled assignments might be delayed up to 5 minutes after the post time.

- To schedule the same assignment across multiple classes, make sure to select all classes you want to include.

- When you enter a time, Classroom defaults to PM unless you specify AM.

- (Optional) Select a due date and topic for each class.

- (Optional) To replicate your selected time and date for the first class into all subsequent classes, click Copy settings to all .

- Click Schedule . The assignment will automatically post at the scheduled date and time.

After scheduling multiple assignments at once, you can still edit assignments later by clicking into each class and changing them individually.

Save an assignment as a draft

- Follow the steps above to create an assignment

You can open and edit draft assignments on the Classwork page.

Manage assignments

Edits affect individual classes. For multi-class assignments, make edits in each class.

Note : If you change an assignment's name, the assignment's Drive folder name isn't updated. Go to Drive and rename the folder.

Edit a posted assignment

- Enter your changes and click Save .

Edit a scheduled assignment

- Enter your changes and click Schedule .

Edit a draft assignment

Changes are automatically saved.

- Assign it immediately (details above).

- Schedule it to post at a specific date and time (details above).

- Click a class.

You can only delete an assignment on the Classwork page.

If you delete an assignment, all grades and comments related to the assignment are deleted. However, any attachments or files created by you or the students are still available in Drive.

Related articles

- Create or reuse a rubric for an assignment

- Create a quiz assignment

- Create a question

- Use add-ons in Classroom

- Create, edit, delete, or share a practice set

- Learn about interactive questions for YouTube videos in Google Classroom

Was this helpful?

Need more help, try these next steps:.

IMAGES

VIDEO