- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 June 2021

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: an overview of systematic reviews

- Israel Júnior Borges do Nascimento 1 , 2 ,

- Dónal P. O’Mathúna 3 , 4 ,

- Thilo Caspar von Groote 5 ,

- Hebatullah Mohamed Abdulazeem 6 ,

- Ishanka Weerasekara 7 , 8 ,

- Ana Marusic 9 ,

- Livia Puljak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8467-6061 10 ,

- Vinicius Tassoni Civile 11 ,

- Irena Zakarija-Grkovic 9 ,

- Tina Poklepovic Pericic 9 ,

- Alvaro Nagib Atallah 11 ,

- Santino Filoso 12 ,

- Nicola Luigi Bragazzi 13 &

- Milena Soriano Marcolino 1

On behalf of the International Network of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (InterNetCOVID-19)

BMC Infectious Diseases volume 21 , Article number: 525 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

34 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

Navigating the rapidly growing body of scientific literature on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is challenging, and ongoing critical appraisal of this output is essential. We aimed to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in humans that were available at the beginning of the pandemic.

Nine databases (Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Web of Sciences, PDQ-Evidence, WHO’s Global Research, LILACS, and Epistemonikos) were searched from December 1, 2019, to March 24, 2020. Systematic reviews analyzing primary studies of COVID-19 were included. Two authors independently undertook screening, selection, extraction (data on clinical symptoms, prevalence, pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, diagnostic test assessment, laboratory, and radiological findings), and quality assessment (AMSTAR 2). A meta-analysis was performed of the prevalence of clinical outcomes.

Eighteen systematic reviews were included; one was empty (did not identify any relevant study). Using AMSTAR 2, confidence in the results of all 18 reviews was rated as “critically low”. Identified symptoms of COVID-19 were (range values of point estimates): fever (82–95%), cough with or without sputum (58–72%), dyspnea (26–59%), myalgia or muscle fatigue (29–51%), sore throat (10–13%), headache (8–12%) and gastrointestinal complaints (5–9%). Severe symptoms were more common in men. Elevated C-reactive protein and lactate dehydrogenase, and slightly elevated aspartate and alanine aminotransferase, were commonly described. Thrombocytopenia and elevated levels of procalcitonin and cardiac troponin I were associated with severe disease. A frequent finding on chest imaging was uni- or bilateral multilobar ground-glass opacity. A single review investigated the impact of medication (chloroquine) but found no verifiable clinical data. All-cause mortality ranged from 0.3 to 13.9%.

Conclusions

In this overview of systematic reviews, we analyzed evidence from the first 18 systematic reviews that were published after the emergence of COVID-19. However, confidence in the results of all reviews was “critically low”. Thus, systematic reviews that were published early on in the pandemic were of questionable usefulness. Even during public health emergencies, studies and systematic reviews should adhere to established methodological standards.

Peer Review reports

The spread of the “Severe Acute Respiratory Coronavirus 2” (SARS-CoV-2), the causal agent of COVID-19, was characterized as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2020 and has triggered an international public health emergency [ 1 ]. The numbers of confirmed cases and deaths due to COVID-19 are rapidly escalating, counting in millions [ 2 ], causing massive economic strain, and escalating healthcare and public health expenses [ 3 , 4 ].

The research community has responded by publishing an impressive number of scientific reports related to COVID-19. The world was alerted to the new disease at the beginning of 2020 [ 1 ], and by mid-March 2020, more than 2000 articles had been published on COVID-19 in scholarly journals, with 25% of them containing original data [ 5 ]. The living map of COVID-19 evidence, curated by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre), contained more than 40,000 records by February 2021 [ 6 ]. More than 100,000 records on PubMed were labeled as “SARS-CoV-2 literature, sequence, and clinical content” by February 2021 [ 7 ].

Due to publication speed, the research community has voiced concerns regarding the quality and reproducibility of evidence produced during the COVID-19 pandemic, warning of the potential damaging approach of “publish first, retract later” [ 8 ]. It appears that these concerns are not unfounded, as it has been reported that COVID-19 articles were overrepresented in the pool of retracted articles in 2020 [ 9 ]. These concerns about inadequate evidence are of major importance because they can lead to poor clinical practice and inappropriate policies [ 10 ].

Systematic reviews are a cornerstone of today’s evidence-informed decision-making. By synthesizing all relevant evidence regarding a particular topic, systematic reviews reflect the current scientific knowledge. Systematic reviews are considered to be at the highest level in the hierarchy of evidence and should be used to make informed decisions. However, with high numbers of systematic reviews of different scope and methodological quality being published, overviews of multiple systematic reviews that assess their methodological quality are essential [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. An overview of systematic reviews helps identify and organize the literature and highlights areas of priority in decision-making.

In this overview of systematic reviews, we aimed to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in humans that were available at the beginning of the pandemic.

Methodology

Research question.

This overview’s primary objective was to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews that assessed any type of primary clinical data from patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Our research question was purposefully broad because we wanted to analyze as many systematic reviews as possible that were available early following the COVID-19 outbreak.

Study design

We conducted an overview of systematic reviews. The idea for this overview originated in a protocol for a systematic review submitted to PROSPERO (CRD42020170623), which indicated a plan to conduct an overview.

Overviews of systematic reviews use explicit and systematic methods for searching and identifying multiple systematic reviews addressing related research questions in the same field to extract and analyze evidence across important outcomes. Overviews of systematic reviews are in principle similar to systematic reviews of interventions, but the unit of analysis is a systematic review [ 14 , 15 , 16 ].

We used the overview methodology instead of other evidence synthesis methods to allow us to collate and appraise multiple systematic reviews on this topic, and to extract and analyze their results across relevant topics [ 17 ]. The overview and meta-analysis of systematic reviews allowed us to investigate the methodological quality of included studies, summarize results, and identify specific areas of available or limited evidence, thereby strengthening the current understanding of this novel disease and guiding future research [ 13 ].

A reporting guideline for overviews of reviews is currently under development, i.e., Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews (PRIOR) [ 18 ]. As the PRIOR checklist is still not published, this study was reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009 statement [ 19 ]. The methodology used in this review was adapted from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and also followed established methodological considerations for analyzing existing systematic reviews [ 14 ].

Approval of a research ethics committee was not necessary as the study analyzed only publicly available articles.

Eligibility criteria

Systematic reviews were included if they analyzed primary data from patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 as confirmed by RT-PCR or another pre-specified diagnostic technique. Eligible reviews covered all topics related to COVID-19 including, but not limited to, those that reported clinical symptoms, diagnostic methods, therapeutic interventions, laboratory findings, or radiological results. Both full manuscripts and abbreviated versions, such as letters, were eligible.

No restrictions were imposed on the design of the primary studies included within the systematic reviews, the last search date, whether the review included meta-analyses or language. Reviews related to SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses were eligible, but from those reviews, we analyzed only data related to SARS-CoV-2.

No consensus definition exists for a systematic review [ 20 ], and debates continue about the defining characteristics of a systematic review [ 21 ]. Cochrane’s guidance for overviews of reviews recommends setting pre-established criteria for making decisions around inclusion [ 14 ]. That is supported by a recent scoping review about guidance for overviews of systematic reviews [ 22 ].

Thus, for this study, we defined a systematic review as a research report which searched for primary research studies on a specific topic using an explicit search strategy, had a detailed description of the methods with explicit inclusion criteria provided, and provided a summary of the included studies either in narrative or quantitative format (such as a meta-analysis). Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews were considered eligible for inclusion, with or without meta-analysis, and regardless of the study design, language restriction and methodology of the included primary studies. To be eligible for inclusion, reviews had to be clearly analyzing data related to SARS-CoV-2 (associated or not with other viruses). We excluded narrative reviews without those characteristics as these are less likely to be replicable and are more prone to bias.

Scoping reviews and rapid reviews were eligible for inclusion in this overview if they met our pre-defined inclusion criteria noted above. We included reviews that addressed SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses if they reported separate data regarding SARS-CoV-2.

Information sources

Nine databases were searched for eligible records published between December 1, 2019, and March 24, 2020: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews via Cochrane Library, PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Web of Sciences, LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature), PDQ-Evidence, WHO’s Global Research on Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19), and Epistemonikos.

The comprehensive search strategy for each database is provided in Additional file 1 and was designed and conducted in collaboration with an information specialist. All retrieved records were primarily processed in EndNote, where duplicates were removed, and records were then imported into the Covidence platform [ 23 ]. In addition to database searches, we screened reference lists of reviews included after screening records retrieved via databases.

Study selection

All searches, screening of titles and abstracts, and record selection, were performed independently by two investigators using the Covidence platform [ 23 ]. Articles deemed potentially eligible were retrieved for full-text screening carried out independently by two investigators. Discrepancies at all stages were resolved by consensus. During the screening, records published in languages other than English were translated by a native/fluent speaker.

Data collection process

We custom designed a data extraction table for this study, which was piloted by two authors independently. Data extraction was performed independently by two authors. Conflicts were resolved by consensus or by consulting a third researcher.

We extracted the following data: article identification data (authors’ name and journal of publication), search period, number of databases searched, population or settings considered, main results and outcomes observed, and number of participants. From Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), we extracted journal rank (quartile) and Journal Impact Factor (JIF).

We categorized the following as primary outcomes: all-cause mortality, need for and length of mechanical ventilation, length of hospitalization (in days), admission to intensive care unit (yes/no), and length of stay in the intensive care unit.

The following outcomes were categorized as exploratory: diagnostic methods used for detection of the virus, male to female ratio, clinical symptoms, pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, laboratory findings (full blood count, liver enzymes, C-reactive protein, d-dimer, albumin, lipid profile, serum electrolytes, blood vitamin levels, glucose levels, and any other important biomarkers), and radiological findings (using radiography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging or ultrasound).

We also collected data on reporting guidelines and requirements for the publication of systematic reviews and meta-analyses from journal websites where included reviews were published.

Quality assessment in individual reviews

Two researchers independently assessed the reviews’ quality using the “A MeaSurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR 2)”. We acknowledge that the AMSTAR 2 was created as “a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomized or non-randomized studies of healthcare interventions, or both” [ 24 ]. However, since AMSTAR 2 was designed for systematic reviews of intervention trials, and we included additional types of systematic reviews, we adjusted some AMSTAR 2 ratings and reported these in Additional file 2 .

Adherence to each item was rated as follows: yes, partial yes, no, or not applicable (such as when a meta-analysis was not conducted). The overall confidence in the results of the review is rated as “critically low”, “low”, “moderate” or “high”, according to the AMSTAR 2 guidance based on seven critical domains, which are items 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15 as defined by AMSTAR 2 authors [ 24 ]. We reported our adherence ratings for transparency of our decision with accompanying explanations, for each item, in each included review.

One of the included systematic reviews was conducted by some members of this author team [ 25 ]. This review was initially assessed independently by two authors who were not co-authors of that review to prevent the risk of bias in assessing this study.

Synthesis of results

For data synthesis, we prepared a table summarizing each systematic review. Graphs illustrating the mortality rate and clinical symptoms were created. We then prepared a narrative summary of the methods, findings, study strengths, and limitations.

For analysis of the prevalence of clinical outcomes, we extracted data on the number of events and the total number of patients to perform proportional meta-analysis using RStudio© software, with the “meta” package (version 4.9–6), using the “metaprop” function for reviews that did not perform a meta-analysis, excluding case studies because of the absence of variance. For reviews that did not perform a meta-analysis, we presented pooled results of proportions with their respective confidence intervals (95%) by the inverse variance method with a random-effects model, using the DerSimonian-Laird estimator for τ 2 . We adjusted data using Freeman-Tukey double arcosen transformation. Confidence intervals were calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method for individual studies. We created forest plots using the RStudio© software, with the “metafor” package (version 2.1–0) and “forest” function.

Managing overlapping systematic reviews

Some of the included systematic reviews that address the same or similar research questions may include the same primary studies in overviews. Including such overlapping reviews may introduce bias when outcome data from the same primary study are included in the analyses of an overview multiple times. Thus, in summaries of evidence, multiple-counting of the same outcome data will give data from some primary studies too much influence [ 14 ]. In this overview, we did not exclude overlapping systematic reviews because, according to Cochrane’s guidance, it may be appropriate to include all relevant reviews’ results if the purpose of the overview is to present and describe the current body of evidence on a topic [ 14 ]. To avoid any bias in summary estimates associated with overlapping reviews, we generated forest plots showing data from individual systematic reviews, but the results were not pooled because some primary studies were included in multiple reviews.

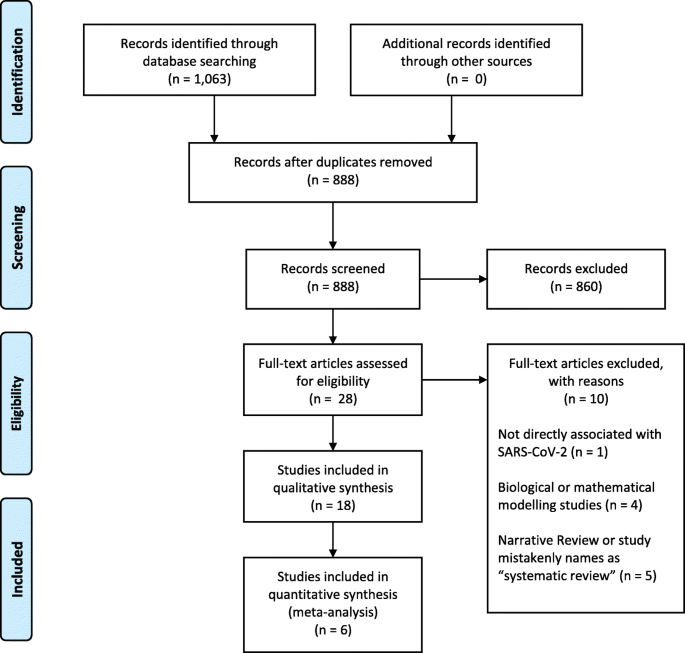

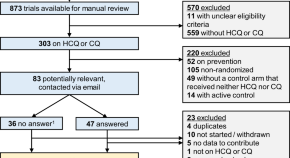

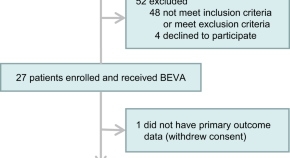

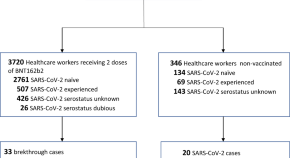

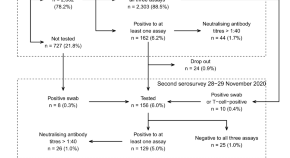

Our search retrieved 1063 publications, of which 175 were duplicates. Most publications were excluded after the title and abstract analysis ( n = 860). Among the 28 studies selected for full-text screening, 10 were excluded for the reasons described in Additional file 3 , and 18 were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1 ) [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ]. Reference list screening did not retrieve any additional systematic reviews.

PRISMA flow diagram

Characteristics of included reviews

Summary features of 18 systematic reviews are presented in Table 1 . They were published in 14 different journals. Only four of these journals had specific requirements for systematic reviews (with or without meta-analysis): European Journal of Internal Medicine, Journal of Clinical Medicine, Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Clinical Research in Cardiology . Two journals reported that they published only invited reviews ( Journal of Medical Virology and Clinica Chimica Acta ). Three systematic reviews in our study were published as letters; one was labeled as a scoping review and another as a rapid review (Table 2 ).

All reviews were published in English, in first quartile (Q1) journals, with JIF ranging from 1.692 to 6.062. One review was empty, meaning that its search did not identify any relevant studies; i.e., no primary studies were included [ 36 ]. The remaining 17 reviews included 269 unique studies; the majority ( N = 211; 78%) were included in only a single review included in our study (range: 1 to 12). Primary studies included in the reviews were published between December 2019 and March 18, 2020, and comprised case reports, case series, cohorts, and other observational studies. We found only one review that included randomized clinical trials [ 38 ]. In the included reviews, systematic literature searches were performed from 2019 (entire year) up to March 9, 2020. Ten systematic reviews included meta-analyses. The list of primary studies found in the included systematic reviews is shown in Additional file 4 , as well as the number of reviews in which each primary study was included.

Population and study designs

Most of the reviews analyzed data from patients with COVID-19 who developed pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), or any other correlated complication. One review aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of using surgical masks on preventing transmission of the virus [ 36 ], one review was focused on pediatric patients [ 34 ], and one review investigated COVID-19 in pregnant women [ 37 ]. Most reviews assessed clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, or radiological results.

Systematic review findings

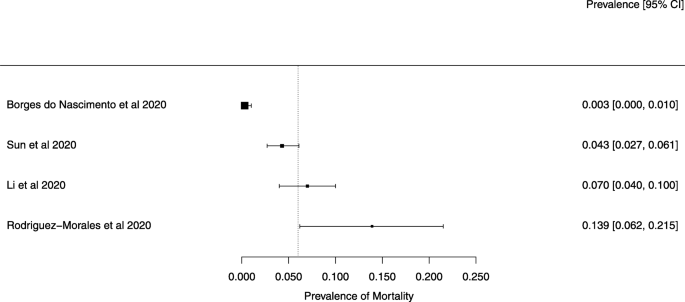

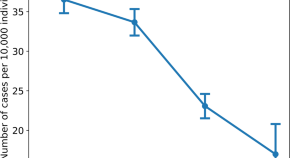

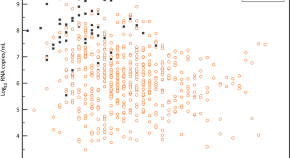

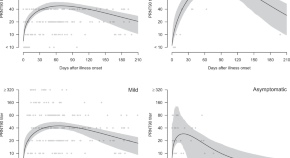

The summary of findings from individual reviews is shown in Table 2 . Overall, all-cause mortality ranged from 0.3 to 13.9% (Fig. 2 ).

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of mortality

Clinical symptoms

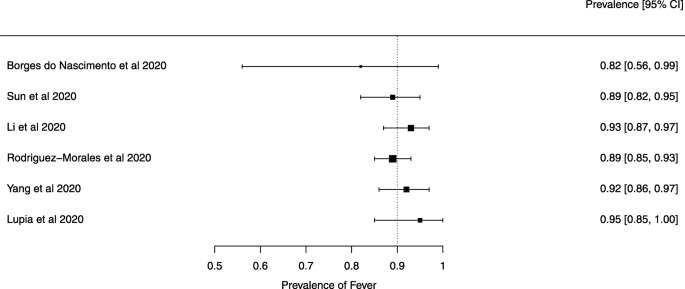

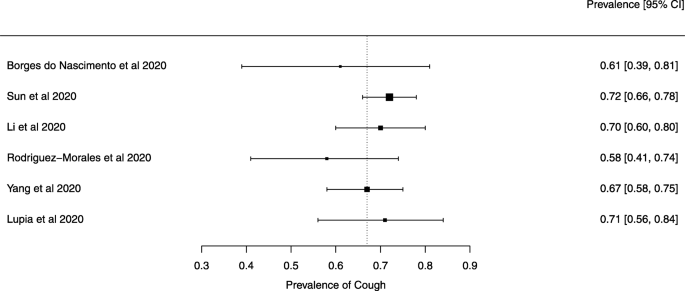

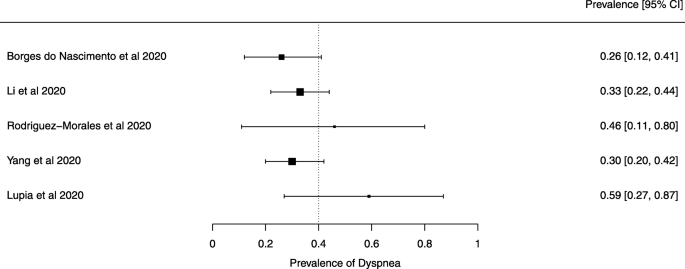

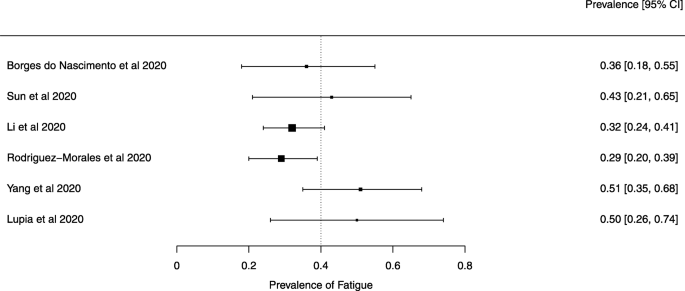

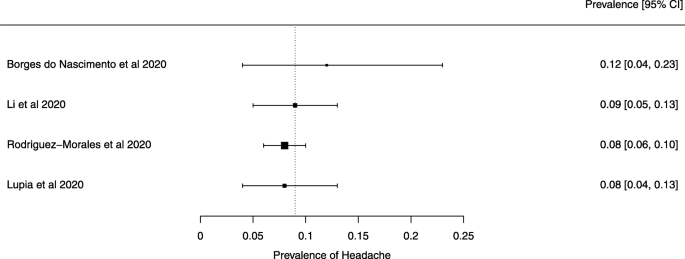

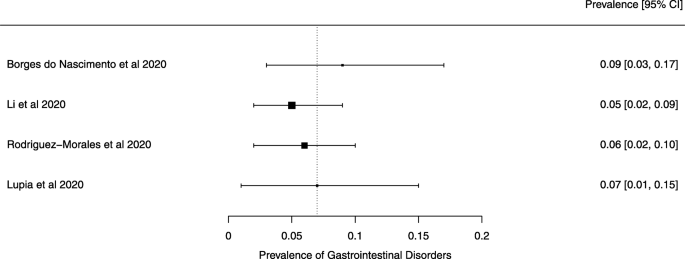

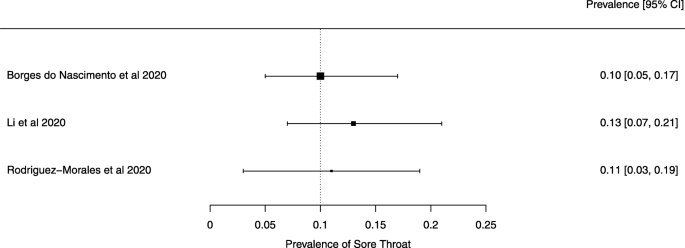

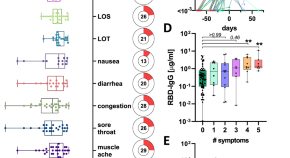

Seven reviews described the main clinical manifestations of COVID-19 [ 26 , 28 , 29 , 34 , 35 , 39 , 41 ]. Three of them provided only a narrative discussion of symptoms [ 26 , 34 , 35 ]. In the reviews that performed a statistical analysis of the incidence of different clinical symptoms, symptoms in patients with COVID-19 were (range values of point estimates): fever (82–95%), cough with or without sputum (58–72%), dyspnea (26–59%), myalgia or muscle fatigue (29–51%), sore throat (10–13%), headache (8–12%), gastrointestinal disorders, such as diarrhea, nausea or vomiting (5.0–9.0%), and others (including, in one study only: dizziness 12.1%) (Figs. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 and 9 ). Three reviews assessed cough with and without sputum together; only one review assessed sputum production itself (28.5%).

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of fever

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of cough

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of dyspnea

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of fatigue or myalgia

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of headache

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of gastrointestinal disorders

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of sore throat

Diagnostic aspects

Three reviews described methodologies, protocols, and tools used for establishing the diagnosis of COVID-19 [ 26 , 34 , 38 ]. The use of respiratory swabs (nasal or pharyngeal) or blood specimens to assess the presence of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid using RT-PCR assays was the most commonly used diagnostic method mentioned in the included studies. These diagnostic tests have been widely used, but their precise sensitivity and specificity remain unknown. One review included a Chinese study with clinical diagnosis with no confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection (patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 if they presented with at least two symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, together with laboratory and chest radiography abnormalities) [ 34 ].

Therapeutic possibilities

Pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions (supportive therapies) used in treating patients with COVID-19 were reported in five reviews [ 25 , 27 , 34 , 35 , 38 ]. Antivirals used empirically for COVID-19 treatment were reported in seven reviews [ 25 , 27 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 41 ]; most commonly used were protease inhibitors (lopinavir, ritonavir, darunavir), nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (tenofovir), nucleotide analogs (remdesivir, galidesivir, ganciclovir), and neuraminidase inhibitors (oseltamivir). Umifenovir, a membrane fusion inhibitor, was investigated in two studies [ 25 , 35 ]. Possible supportive interventions analyzed were different types of oxygen supplementation and breathing support (invasive or non-invasive ventilation) [ 25 ]. The use of antibiotics, both empirically and to treat secondary pneumonia, was reported in six studies [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 34 , 35 , 38 ]. One review specifically assessed evidence on the efficacy and safety of the anti-malaria drug chloroquine [ 27 ]. It identified 23 ongoing trials investigating the potential of chloroquine as a therapeutic option for COVID-19, but no verifiable clinical outcomes data. The use of mesenchymal stem cells, antifungals, and glucocorticoids were described in four reviews [ 25 , 34 , 35 , 38 ].

Laboratory and radiological findings

Of the 18 reviews included in this overview, eight analyzed laboratory parameters in patients with COVID-19 [ 25 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 39 ]; elevated C-reactive protein levels, associated with lymphocytopenia, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, as well as slightly elevated aspartate and alanine aminotransferase (AST, ALT) were commonly described in those eight reviews. Lippi et al. assessed cardiac troponin I (cTnI) [ 25 ], procalcitonin [ 32 ], and platelet count [ 33 ] in COVID-19 patients. Elevated levels of procalcitonin [ 32 ] and cTnI [ 30 ] were more likely to be associated with a severe disease course (requiring intensive care unit admission and intubation). Furthermore, thrombocytopenia was frequently observed in patients with complicated COVID-19 infections [ 33 ].

Chest imaging (chest radiography and/or computed tomography) features were assessed in six reviews, all of which described a frequent pattern of local or bilateral multilobar ground-glass opacity [ 25 , 34 , 35 , 39 , 40 , 41 ]. Those six reviews showed that septal thickening, bronchiectasis, pleural and cardiac effusions, halo signs, and pneumothorax were observed in patients suffering from COVID-19.

Quality of evidence in individual systematic reviews

Table 3 shows the detailed results of the quality assessment of 18 systematic reviews, including the assessment of individual items and summary assessment. A detailed explanation for each decision in each review is available in Additional file 5 .

Using AMSTAR 2 criteria, confidence in the results of all 18 reviews was rated as “critically low” (Table 3 ). Common methodological drawbacks were: omission of prospective protocol submission or publication; use of inappropriate search strategy: lack of independent and dual literature screening and data-extraction (or methodology unclear); absence of an explanation for heterogeneity among the studies included; lack of reasons for study exclusion (or rationale unclear).

Risk of bias assessment, based on a reported methodological tool, and quality of evidence appraisal, in line with the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) method, were reported only in one review [ 25 ]. Five reviews presented a table summarizing bias, using various risk of bias tools [ 25 , 29 , 39 , 40 , 41 ]. One review analyzed “study quality” [ 37 ]. One review mentioned the risk of bias assessment in the methodology but did not provide any related analysis [ 28 ].

This overview of systematic reviews analyzed the first 18 systematic reviews published after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, up to March 24, 2020, with primary studies involving more than 60,000 patients. Using AMSTAR-2, we judged that our confidence in all those reviews was “critically low”. Ten reviews included meta-analyses. The reviews presented data on clinical manifestations, laboratory and radiological findings, and interventions. We found no systematic reviews on the utility of diagnostic tests.

Symptoms were reported in seven reviews; most of the patients had a fever, cough, dyspnea, myalgia or muscle fatigue, and gastrointestinal disorders such as diarrhea, nausea, or vomiting. Olfactory dysfunction (anosmia or dysosmia) has been described in patients infected with COVID-19 [ 43 ]; however, this was not reported in any of the reviews included in this overview. During the SARS outbreak in 2002, there were reports of impairment of the sense of smell associated with the disease [ 44 , 45 ].

The reported mortality rates ranged from 0.3 to 14% in the included reviews. Mortality estimates are influenced by the transmissibility rate (basic reproduction number), availability of diagnostic tools, notification policies, asymptomatic presentations of the disease, resources for disease prevention and control, and treatment facilities; variability in the mortality rate fits the pattern of emerging infectious diseases [ 46 ]. Furthermore, the reported cases did not consider asymptomatic cases, mild cases where individuals have not sought medical treatment, and the fact that many countries had limited access to diagnostic tests or have implemented testing policies later than the others. Considering the lack of reviews assessing diagnostic testing (sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of RT-PCT or immunoglobulin tests), and the preponderance of studies that assessed only symptomatic individuals, considerable imprecision around the calculated mortality rates existed in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Few reviews included treatment data. Those reviews described studies considered to be at a very low level of evidence: usually small, retrospective studies with very heterogeneous populations. Seven reviews analyzed laboratory parameters; those reviews could have been useful for clinicians who attend patients suspected of COVID-19 in emergency services worldwide, such as assessing which patients need to be reassessed more frequently.

All systematic reviews scored poorly on the AMSTAR 2 critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews. Most of the original studies included in the reviews were case series and case reports, impacting the quality of evidence. Such evidence has major implications for clinical practice and the use of these reviews in evidence-based practice and policy. Clinicians, patients, and policymakers can only have the highest confidence in systematic review findings if high-quality systematic review methodologies are employed. The urgent need for information during a pandemic does not justify poor quality reporting.

We acknowledge that there are numerous challenges associated with analyzing COVID-19 data during a pandemic [ 47 ]. High-quality evidence syntheses are needed for decision-making, but each type of evidence syntheses is associated with its inherent challenges.

The creation of classic systematic reviews requires considerable time and effort; with massive research output, they quickly become outdated, and preparing updated versions also requires considerable time. A recent study showed that updates of non-Cochrane systematic reviews are published a median of 5 years after the publication of the previous version [ 48 ].

Authors may register a review and then abandon it [ 49 ], but the existence of a public record that is not updated may lead other authors to believe that the review is still ongoing. A quarter of Cochrane review protocols remains unpublished as completed systematic reviews 8 years after protocol publication [ 50 ].

Rapid reviews can be used to summarize the evidence, but they involve methodological sacrifices and simplifications to produce information promptly, with inconsistent methodological approaches [ 51 ]. However, rapid reviews are justified in times of public health emergencies, and even Cochrane has resorted to publishing rapid reviews in response to the COVID-19 crisis [ 52 ]. Rapid reviews were eligible for inclusion in this overview, but only one of the 18 reviews included in this study was labeled as a rapid review.

Ideally, COVID-19 evidence would be continually summarized in a series of high-quality living systematic reviews, types of evidence synthesis defined as “ a systematic review which is continually updated, incorporating relevant new evidence as it becomes available ” [ 53 ]. However, conducting living systematic reviews requires considerable resources, calling into question the sustainability of such evidence synthesis over long periods [ 54 ].

Research reports about COVID-19 will contribute to research waste if they are poorly designed, poorly reported, or simply not necessary. In principle, systematic reviews should help reduce research waste as they usually provide recommendations for further research that is needed or may advise that sufficient evidence exists on a particular topic [ 55 ]. However, systematic reviews can also contribute to growing research waste when they are not needed, or poorly conducted and reported. Our present study clearly shows that most of the systematic reviews that were published early on in the COVID-19 pandemic could be categorized as research waste, as our confidence in their results is critically low.

Our study has some limitations. One is that for AMSTAR 2 assessment we relied on information available in publications; we did not attempt to contact study authors for clarifications or additional data. In three reviews, the methodological quality appraisal was challenging because they were published as letters, or labeled as rapid communications. As a result, various details about their review process were not included, leading to AMSTAR 2 questions being answered as “not reported”, resulting in low confidence scores. Full manuscripts might have provided additional information that could have led to higher confidence in the results. In other words, low scores could reflect incomplete reporting, not necessarily low-quality review methods. To make their review available more rapidly and more concisely, the authors may have omitted methodological details. A general issue during a crisis is that speed and completeness must be balanced. However, maintaining high standards requires proper resourcing and commitment to ensure that the users of systematic reviews can have high confidence in the results.

Furthermore, we used adjusted AMSTAR 2 scoring, as the tool was designed for critical appraisal of reviews of interventions. Some reviews may have received lower scores than actually warranted in spite of these adjustments.

Another limitation of our study may be the inclusion of multiple overlapping reviews, as some included reviews included the same primary studies. According to the Cochrane Handbook, including overlapping reviews may be appropriate when the review’s aim is “ to present and describe the current body of systematic review evidence on a topic ” [ 12 ], which was our aim. To avoid bias with summarizing evidence from overlapping reviews, we presented the forest plots without summary estimates. The forest plots serve to inform readers about the effect sizes for outcomes that were reported in each review.

Several authors from this study have contributed to one of the reviews identified [ 25 ]. To reduce the risk of any bias, two authors who did not co-author the review in question initially assessed its quality and limitations.

Finally, we note that the systematic reviews included in our overview may have had issues that our analysis did not identify because we did not analyze their primary studies to verify the accuracy of the data and information they presented. We give two examples to substantiate this possibility. Lovato et al. wrote a commentary on the review of Sun et al. [ 41 ], in which they criticized the authors’ conclusion that sore throat is rare in COVID-19 patients [ 56 ]. Lovato et al. highlighted that multiple studies included in Sun et al. did not accurately describe participants’ clinical presentations, warning that only three studies clearly reported data on sore throat [ 56 ].

In another example, Leung [ 57 ] warned about the review of Li, L.Q. et al. [ 29 ]: “ it is possible that this statistic was computed using overlapped samples, therefore some patients were double counted ”. Li et al. responded to Leung that it is uncertain whether the data overlapped, as they used data from published articles and did not have access to the original data; they also reported that they requested original data and that they plan to re-do their analyses once they receive them; they also urged readers to treat the data with caution [ 58 ]. This points to the evolving nature of evidence during a crisis.

Our study’s strength is that this overview adds to the current knowledge by providing a comprehensive summary of all the evidence synthesis about COVID-19 available early after the onset of the pandemic. This overview followed strict methodological criteria, including a comprehensive and sensitive search strategy and a standard tool for methodological appraisal of systematic reviews.

In conclusion, in this overview of systematic reviews, we analyzed evidence from the first 18 systematic reviews that were published after the emergence of COVID-19. However, confidence in the results of all the reviews was “critically low”. Thus, systematic reviews that were published early on in the pandemic could be categorized as research waste. Even during public health emergencies, studies and systematic reviews should adhere to established methodological standards to provide patients, clinicians, and decision-makers trustworthy evidence.

Availability of data and materials

All data collected and analyzed within this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

World Health Organization. Timeline - COVID-19: Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline . Accessed 1 June 2021.

COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). Available at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Anzai A, Kobayashi T, Linton NM, Kinoshita R, Hayashi K, Suzuki A, et al. Assessing the Impact of Reduced Travel on Exportation Dynamics of Novel Coronavirus Infection (COVID-19). J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):601.

Chinazzi M, Davis JT, Ajelli M, Gioannini C, Litvinova M, Merler S, et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science. 2020;368(6489):395–400. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba9757 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fidahic M, Nujic D, Runjic R, Civljak M, Markotic F, Lovric Makaric Z, et al. Research methodology and characteristics of journal articles with original data, preprint articles and registered clinical trial protocols about COVID-19. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(1):161. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-01047-2 .

EPPI Centre . COVID-19: a living systematic map of the evidence. Available at: http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Projects/DepartmentofHealthandSocialCare/Publishedreviews/COVID-19Livingsystematicmapoftheevidence/tabid/3765/Default.aspx . Accessed 1 June 2021.

NCBI SARS-CoV-2 Resources. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sars-cov-2/ . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Gustot T. Quality and reproducibility during the COVID-19 pandemic. JHEP Rep. 2020;2(4):100141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100141 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kodvanj, I., et al., Publishing of COVID-19 Preprints in Peer-reviewed Journals, Preprinting Trends, Public Discussion and Quality Issues. Preprint article. bioRxiv 2020.11.23.394577; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.23.394577 .

Dobler CC. Poor quality research and clinical practice during COVID-19. Breathe (Sheff). 2020;16(2):200112. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.0112-2020 .

Article Google Scholar

Bastian H, Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med. 2010;7(9):e1000326. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000326 .

Lunny C, Brennan SE, McDonald S, McKenzie JE. Toward a comprehensive evidence map of overview of systematic review methods: paper 1-purpose, eligibility, search and data extraction. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):231. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0617-1 .

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Becker LA, Pieper D, Hartling L. Chapter V: Overviews of Reviews. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane. 2020. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane. 2020; Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Newton AS, Scott SD, Hartling L. The impact of different inclusion decisions on the comprehensiveness and complexity of overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0914-3 .

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Newton AS, Scott SD, Hartling L. A decision tool to help researchers make decisions about including systematic reviews in overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0768-8 .

Hunt H, Pollock A, Campbell P, Estcourt L, Brunton G. An introduction to overviews of reviews: planning a relevant research question and objective for an overview. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0695-8 .

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Pieper D, Tricco AC, Gates M, Gates A, et al. Preferred reporting items for overviews of reviews (PRIOR): a protocol for development of a reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):335. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1252-9 .

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Open Med. 2009;3(3):e123–30.

Krnic Martinic M, Pieper D, Glatt A, Puljak L. Definition of a systematic review used in overviews of systematic reviews, meta-epidemiological studies and textbooks. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):203. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0855-0 .

Puljak L. If there is only one author or only one database was searched, a study should not be called a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;91:4–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.08.002 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gates M, Gates A, Guitard S, Pollock M, Hartling L. Guidance for overviews of reviews continues to accumulate, but important challenges remain: a scoping review. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):254. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01509-0 .

Covidence - systematic review software. Available at: https://www.covidence.org/ . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

Borges do Nascimento IJ, et al. Novel Coronavirus Infection (COVID-19) in Humans: A Scoping Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):941.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu YJ, Mao YP, Ye RX, Wang QZ, et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-020-00646-x .

Cortegiani A, Ingoglia G, Ippolito M, Giarratano A, Einav S. A systematic review on the efficacy and safety of chloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. J Crit Care. 2020;57:279–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.005 .

Li B, Yang J, Zhao F, Zhi L, Wang X, Liu L, et al. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin Res Cardiol. 2020;109(5):531–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-020-01626-9 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Li LQ, Huang T, Wang YQ, Wang ZP, Liang Y, Huang TB, et al. COVID-19 patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate, and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):577–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25757 .

Lippi G, Lavie CJ, Sanchis-Gomar F. Cardiac troponin I in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): evidence from a meta-analysis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63(3):390–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2020.03.001 .

Lippi G, Henry BM. Active smoking is not associated with severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Eur J Intern Med. 2020;75:107–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2020.03.014 .

Lippi G, Plebani M. Procalcitonin in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;505:190–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.004 .

Lippi G, Plebani M, Henry BM. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;506:145–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022 .

Ludvigsson JF. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(6):1088–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15270 .

Lupia T, Scabini S, Mornese Pinna S, di Perri G, de Rosa FG, Corcione S. 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak: a new challenge. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;21:22–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2020.02.021 .

Marasinghe, K.M., A systematic review investigating the effectiveness of face mask use in limiting the spread of COVID-19 among medically not diagnosed individuals: shedding light on current recommendations provided to individuals not medically diagnosed with COVID-19. Research Square. Preprint article. doi : https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-16701/v1 . 2020 .

Mullins E, Evans D, Viner RM, O’Brien P, Morris E. Coronavirus in pregnancy and delivery: rapid review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;55(5):586–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.22014 .

Pang J, Wang MX, Ang IYH, Tan SHX, Lewis RF, Chen JIP, et al. Potential Rapid Diagnostics, Vaccine and Therapeutics for 2019 Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV): a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3):623.

Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, Villamizar-Peña R, Holguin-Rivera Y, Escalera-Antezana JP, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;34:101623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101623 .

Salehi S, Abedi A, Balakrishnan S, Gholamrezanezhad A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review of imaging findings in 919 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;215(1):87–93. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.20.23034 .

Sun P, Qie S, Liu Z, Ren J, Li K, Xi J. Clinical characteristics of hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: a single arm meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):612–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25735 .

Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, Pu K, Chen Z, Guo Q, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:91–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017 .

Bassetti M, Vena A, Giacobbe DR. The novel Chinese coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infections: challenges for fighting the storm. Eur J Clin Investig. 2020;50(3):e13209. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.13209 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hwang CS. Olfactory neuropathy in severe acute respiratory syndrome: report of a case. Acta Neurol Taiwanica. 2006;15(1):26–8.

Google Scholar

Suzuki M, Saito K, Min WP, Vladau C, Toida K, Itoh H, et al. Identification of viruses in patients with postviral olfactory dysfunction. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(2):272–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlg.0000249922.37381.1e .

Rajgor DD, Lee MH, Archuleta S, Bagdasarian N, Quek SC. The many estimates of the COVID-19 case fatality rate. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):776–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30244-9 .

Wolkewitz M, Puljak L. Methodological challenges of analysing COVID-19 data during the pandemic. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(1):81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-00972-6 .

Rombey T, Lochner V, Puljak L, Könsgen N, Mathes T, Pieper D. Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of non-Cochrane updates of systematic reviews: a cross-sectional study. Res Synth Methods. 2020;11(3):471–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1409 .

Runjic E, Rombey T, Pieper D, Puljak L. Half of systematic reviews about pain registered in PROSPERO were not published and the majority had inaccurate status. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;116:114–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.08.010 .

Runjic E, Behmen D, Pieper D, Mathes T, Tricco AC, Moher D, et al. Following Cochrane review protocols to completion 10 years later: a retrospective cohort study and author survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;111:41–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.03.006 .

Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, Strifler L, Ghassemi M, Ivory J, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):224. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0465-6 .

COVID-19 Rapid Reviews: Cochrane’s response so far. Available at: https://training.cochrane.org/resource/covid-19-rapid-reviews-cochrane-response-so-far . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Cochrane. Living systematic reviews. Available at: https://community.cochrane.org/review-production/production-resources/living-systematic-reviews . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Millard T, Synnot A, Elliott J, Green S, McDonald S, Turner T. Feasibility and acceptability of living systematic reviews: results from a mixed-methods evaluation. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):325. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1248-5 .

Babic A, Poklepovic Pericic T, Pieper D, Puljak L. How to decide whether a systematic review is stable and not in need of updating: analysis of Cochrane reviews. Res Synth Methods. 2020;11(6):884–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1451 .

Lovato A, Rossettini G, de Filippis C. Sore throat in COVID-19: comment on “clinical characteristics of hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: a single arm meta-analysis”. J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):714–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25815 .

Leung C. Comment on Li et al: COVID-19 patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate, and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(9):1431–2. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25912 .

Li LQ, Huang T, Wang YQ, Wang ZP, Liang Y, Huang TB, et al. Response to Char’s comment: comment on Li et al: COVID-19 patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate, and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(9):1433. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25924 .

Download references

Acknowledgments

We thank Catherine Henderson DPhil from Swanscoe Communications for pro bono medical writing and editing support. We acknowledge support from the Covidence Team, specifically Anneliese Arno. We thank the whole International Network of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (InterNetCOVID-19) for their commitment and involvement. Members of the InterNetCOVID-19 are listed in Additional file 6 . We thank Pavel Cerny and Roger Crosthwaite for guiding the team supervisor (IJBN) on human resources management.

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University Hospital and School of Medicine, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil

Israel Júnior Borges do Nascimento & Milena Soriano Marcolino

Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA

Israel Júnior Borges do Nascimento

Helene Fuld Health Trust National Institute for Evidence-based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare, College of Nursing, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA

Dónal P. O’Mathúna

School of Nursing, Psychotherapy and Community Health, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

Department of Anesthesiology, Intensive Care and Pain Medicine, University of Münster, Münster, Germany

Thilo Caspar von Groote

Department of Sport and Health Science, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany

Hebatullah Mohamed Abdulazeem

School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Health and Medicine, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan, Australia

Ishanka Weerasekara

Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka

Cochrane Croatia, University of Split, School of Medicine, Split, Croatia

Ana Marusic, Irena Zakarija-Grkovic & Tina Poklepovic Pericic

Center for Evidence-Based Medicine and Health Care, Catholic University of Croatia, Ilica 242, 10000, Zagreb, Croatia

Livia Puljak

Cochrane Brazil, Evidence-Based Health Program, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Vinicius Tassoni Civile & Alvaro Nagib Atallah

Yorkville University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada

Santino Filoso

Laboratory for Industrial and Applied Mathematics (LIAM), Department of Mathematics and Statistics, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Nicola Luigi Bragazzi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

IJBN conceived the research idea and worked as a project coordinator. DPOM, TCVG, HMA, IW, AM, LP, VTC, IZG, TPP, ANA, SF, NLB and MSM were involved in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and initial draft writing. All authors revised the manuscript critically for the content. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Livia Puljak .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not required as data was based on published studies.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: appendix 1..

Search strategies used in the study.

Additional file 2: Appendix 2.

Adjusted scoring of AMSTAR 2 used in this study for systematic reviews of studies that did not analyze interventions.

Additional file 3: Appendix 3.

List of excluded studies, with reasons.

Additional file 4: Appendix 4.

Table of overlapping studies, containing the list of primary studies included, their visual overlap in individual systematic reviews, and the number in how many reviews each primary study was included.

Additional file 5: Appendix 5.

A detailed explanation of AMSTAR scoring for each item in each review.

Additional file 6: Appendix 6.

List of members and affiliates of International Network of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (InterNetCOVID-19).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Borges do Nascimento, I.J., O’Mathúna, D.P., von Groote, T.C. et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: an overview of systematic reviews. BMC Infect Dis 21 , 525 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06214-4

Download citation

Received : 12 April 2020

Accepted : 19 May 2021

Published : 04 June 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06214-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Coronavirus

- Evidence-based medicine

- Infectious diseases

BMC Infectious Diseases

ISSN: 1471-2334

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Ther Adv Vaccines Immunother

Comprehensive literature review on COVID-19 vaccines and role of SARS-CoV-2 variants in the pandemic

Charles yap.

School of Medicine, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland

Abulhassan Ali

Amogh prabhakar, akul prabhakar, ying yi lim, pramath kakodkar.

School of Medicine, National University of Ireland, Galway, University Road, Galway H91 TK33, Ireland

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a rapid expansion in vaccine research focusing on exploiting the novel discoveries on the pathophysiology, genomics, and molecular biology of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. Although the current preventive measures are primarily socially distancing by maintaining a 1 m distance, it is supplemented using facial masks and other personal hygiene measures. However, the induction of vaccines as primary prevention is crucial to eradicating the disease to attempt restoration to normalcy. This literature review aims to describe the physiology of the vaccines and how the spike protein is used as a target to elicit an antibody-dependent immune response in humans. Furthermore, the overview, dosing strategies, efficacy, and side effects will be discussed for the notable vaccines: BioNTech/Pfizer, Moderna, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Gamaleya, and SinoVac. In addition, the development of other prominent COVID-19 vaccines will be highlighted alongside the sustainability of the vaccine-mediated immune response and current contraindications. As the research is rapidly expanding, we have looked at the association between pregnancy and COVID-19 vaccinations, in addition to the current reviews on the mixing of vaccines. Finally, the prominent emerging variants of concern are described, and the efficacy of the notable vaccines toward these variants has been summarized.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has resulted in over 192 million cases and 4.1 million deaths as of July 22, 2021. 1 This pandemic has brought along a massive burden in morbidity and mortality in the healthcare systems. Despite the implementation of stringent public health measures, there have been devasting effects in other sectors contributing to our economy. This has plunged the global economies toward deep recession and has racked up a debt of approximately 19.5 trillion USD. 2

Immune protection in COVID-19 infection can be conceptualized as a spectrum wherein sterile immunity is at the end of positive spectrum. This is followed by transient infection (<3 days) and asymptomatic infection (~1 week). The negative spectrum of immune protection includes patients who are symptomatic, or hospitalized, or admitted to the intensive care unit for multiorgan support. The extreme end of the negative spectrum of immune protection is encompassed by case fatality. The vaccine will intervene prior to the viral insult and stabilize the population at the positive end of the spectrum of the immune protection. It will also prevent the perpetuating cycle of infection and reinfection via variants of SARS-CoV-2 virus in those who have achieved prior convalescence. One study by Dan et al. showed that in patients infected with COVID-19, immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 remained intact for up to 6 months. 3 Unfortunately, there is no long-term data on the duration of protected immunity against SARS-CoV-2 in patients after convalescence. Therefore, these patients may also require vaccination but the current priority for vaccination can be stretched relative to the unaffected population.

While the ideal goal of the COVID-19 vaccine roll-out is to instill a global herd immunity; it is important to remember that this goal may never be reached. Furthermore, additional goals of vaccination may be to reduce mortality and stress on healthcare systems by reducing the cases of admitted patients. Various countries have already approved COVID-19 vaccines for human use, and more are expected to be licensed in the upcoming year. It is important that these vaccines are safe, efficacious, and can be deployed on a large scale. It is also prudent to eliminate the concerns of both the scientific and general community regarding its effectiveness, side-effects, and dosing strategies.

Historically, the process of vaccine manufacturing and clinical trials required approximately 10 years, but due to the burden of this disease, various observational studies were expedited so that all crucial information regarding the vaccine pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, dosing, efficacy, and adverse events can be collected within a short period of time. Furthermore, there is a need to provide a compilation of accredited and appraised scientific literature on each of these approved vaccines with an aim to instill public health knowledge and vaccine literacy to members of the scientific and general community. A section dedicated to COVID-19 vaccines and pregnancy is also included in the penultimate section of this review.

Finally, the emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 viral variants of concern (VOC) has attained increased replication, transmission, and infectivity warranting exploration of these genomic mutations as their phenotypes. Hence, the final section of this review will aim to clarify the jargon, highlight the vaccine efficacy (VE) against VOCs, and eliminate any misinformation regarding these variants.

Vaccine physiology

The global burden of the pandemic requires an efficacious vaccine that elicits a lasting protective immune response against SARS-CoV-2. This will be an essential armament for the prevention and mitigation of the downstream morbidity and mortality caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. As of July 20, 2021, there are approximately 108 vaccines in clinical development and 184 vaccines in pre-clinical development with several vaccines being distributed globally. 4

The technologies employed in the vaccine synthesis and development aim to trigger the adaptive immune system and elicit memory cells that will protect the body from subsequent infections. These technologies may be mRNA-based vaccines such as the Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech, inactivated virus vector vaccines, DNA vaccines, and numerous other technologies. 5

Due to the urgent implementation of vaccine development, the most obvious target will be the robust proteins expressed on the surface of the virus. Therefore, these technologies target molecular expression of the trimeric SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) glycoprotein. These targets could include its mRNA, DNA, full S1 subunit, or fusion subunits. The S protein is a major component of the virus envelope, it is vital for viral fusion, receptor binding, and virus-entry through recognition of host-cellular receptor. The S protein comprises of two main functional units, the S1 subunit, which contains the receptor-binding domain (RBD) and the S2 subunit which is responsible for virus fusion with the host-cell membrane. 6 The choice to proceed with S protein as the target was reinforced when a study by Dan et al. confirmed that in 169 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, spike-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) remained stable for over 6 months. 3 In addition, both spike-specific CD4+ T-cells (CD137+ and OX40+) and spike-specific CD8+ T-cells (CD69+ and CD137+) were present at the 6-month post-convalescence period, but their subpopulations exhibited a steady decline with a half-life of 139 days and 225 days, respectively. 3

There are subtle differences in the mechanism by which the different vaccine products interact within host cells to induce immunity. Many successful vaccines of the 20 century utilized the target proteins directly such as the tetanus and pertussis vaccine. A summary of the major types of vaccines and their mechanism of action are shown in Figure 1 .

Summary of major vaccine types and their mechanism of action.

DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; HPV, Human papillomavirus; mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid; MMR, Measles, Mumps, and Rubella; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Historically, vaccines usually contained adjuvants which are protein sensitizers that heighten the migratory and sampling response of antigen presenting cells (APCs). Interestingly, the current mRNA vaccines are engineered to code for their own sensitizing protein alongside the S-protein epitopes. Therefore, these new mRNA vaccines usually do not contain any adjuvants. In addition, the mRNA vaccines utilize lipid nanoparticles to deliver the genetic material of a viral S-protein. Contrastingly, vaccines such as the AstraZeneca vaccine may employ a chimpanzee adenovirus vector to carry the DNA genome of the S-protein to the host-cell. 7 Once undergoing the processes of transcription and translation into proteins, these are trafficked and expressed on the host cell surface wherein the adaptive immune system mounts a response via the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules ( Figure 2 ).

Mechanism of induction of immunity through vaccination.

APC, antigen presenting cells; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

There are two types of MHC molecules, the first one that will be discussed is the MHC-II, which is found exclusively on APC: these comprise of B-cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells in the lymph nodes. Once the S-protein antigen is presented at the cell surface of the MHC-II molecules, the naïve helper T-cell’s (Th Cells) T-cell receptor (TCR) complex will interact with this antigen leading to activation of CD4+ Th cells. This activation is perpetuated by a secondary activation signal with B7 on the APC recognizing the CD28 on the Th cell which triggers the proliferation of Th cells that can recognize the S-protein antigen. Activated CD4+ Th cells then secrete numerous cytokines, namely interleukin (IL)-2 which activates CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells (Tc cell) and trigger clonal expansion of B-cells in memory B-cells and plasma cells. The cytokines IL-4 and IL-5 facilitate B-cell isotype switching and maturation to plasma cells; promoting secretion of IgG antibodies against S-protein. 8 Formation of antibodies allows the immune system to direct an immune response against cells expressing the S-protein of the virus. The second process involves MHC-I, which activates CD8+ Naïve Tc cells through TCR complex interaction with processed endogenously synthesized S-protein expressed on MHC-I. MHC-I is expressed in all nucleated cells, APCs, and platelets and require a second activation signal provided by IL-2 from activated CD4+ Th cells. This activates CD8+ Tc cells which can mount a cytotoxic response against SARS-CoV-2-infected cells through two mechanisms of apoptosis. The first mechanism is the secretion of perforin which create pores to allow granzyme to enter the targeted cell, thus activating apoptosis. The second mechanism is via the expression of FasL, which binds Fas on target cells and induces apoptosis. 8 A crucial part of this process is the stimulation of memory T-cells and memory B-cells. Importantly, while the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine’s lasting effect is still being researched in the context of the pandemic, theoretically these should provide lasting immunity and allow the immune system to mount a faster and more effective response should a vaccinated individual encounter the virus in the future.

Current prominent COVID-19 vaccines

Biontech/pfizer.

The BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine developed by BioNTech and Pfizer is a lipid nanoparticle-formulated, nucleoside-modified RNA vaccine that encodes a prefusion membrane-anchored SARS-CoV-2 full-length spike protein. 9 It was the first vaccine approved by the US Food and Drug Association (FDA) and now it has been approved in many other countries. 10 The BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine may be stored at standard refrigerator temperatures prior to use, but it requires very cold temperatures for long-term storage and shipping (−70°C) to maintain the stability of the lipid nanoparticle. In a phase-1 trial, it was compared to another vaccine candidate BNT162b1, and it was found to have a milder systemic side-effect profile with a similar antibody response. 11 Therefore, it was pushed forward to a blinded phase-2/3 clinical study. 9 In total, 43,548 participants were randomized to receive either two doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine (n = 21,720) or a placebo (n = 21,728) 21 days apart. The participant ages ranged from 16 to 91 years, 35.1% of participants were classified as having obesity and comorbidities within participants included HIV, malignancy, diabetes, and vascular diseases. 9 Based on the results of the study, 7 days after the second BNT162b2 dose, the VE was 95% (95% confidence interval (CI), 90.3–97.6) with only eight observed cases of COVID-19 in the vaccine recipients and 162 cases in the placebo recipients. 9 The efficacy remained consistent across subgroups characterized by age, sex, race, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), and comorbidities (generally 90–100%). 9 Although there were 10 cases of severe COVID-19 with onset after the first dose, only one occurred in a vaccine recipient and nine in placebo recipients. Like the phase-1 trial results, the safety profile remained favorable with the most common local reaction being mild-to-moderate pain at the injection site while the most common systemic symptoms were fatigue and headache (reported in ⩾50%). 9 In both the vaccine and placebo group, the incidence of severe adverse events did not differ significantly (0.6% and 0.5%, respectively) and no deaths occurred related to the vaccine. As indicated by the manufacturer’s information, contraindications for use include hypersensitivity to the active substance or any of the excipients. 12 These studies show that the mRNA-vaccine BNT162b2 is safe and effective in protecting against COVID-19. However, further investigations are needed to confirm long-term safety and to establish safety and efficacy for populations not included in this study.

The mRNA-1273 vaccine, developed by Moderna, relies on mRNA technology to encode prefusion stabilized SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. It is the second COVID-19 vaccine to receive emergency use approval by the US FDA, and it is given as two 100-µg doses intramuscularly into the deltoid muscle, 28 days apart. 13 Storage of the vaccine is done at temperatures between −25°C to −15°C for long-term storage, 2°C to 8°C for 30 days, or 8°C to 25°C for up to 12 hours. Results from the COVE phase-3 trial showed that the mRNA-1273 vaccine was effective at preventing COVID-19 illness in persons 18 years of age or older. A total of 30,420 participants aged 18 years or older were randomized 1:1 to receive either two doses of the vaccine or a placebo, 28 days apart. 14 The mean age of the participants was 51.4 years, and enrollment was adjusted for equal representation of racial and ethnic minorities. In the trial, symptomatic COVID-19 illness occurred in 11 participants within the vaccine group versus 185 participants within the placebo group, showing a 94.1% (95% CI, 89.3–96.8%) efficacy of the vaccine. Efficacy was similar across age, sex, race, and ethnicity as well as in patients with and without risk factors for severe disease (e.g. chronic lung disease, cardiac disease, and severe obesity). Importantly, a secondary endpoint for determining the efficacy of the vaccine in preventing severe COVID-19 was also used. All 30 participants with severe COVID-19 were in the placebo group, indicating a 100% efficacy of no hospital admissions. 14 Regarding the side effects of the vaccine, adverse events at the injection site and systemic adverse events occurred more commonly with the mRNA-1273 group compared to the placebo. The most common local reaction was mild to moderate pain at the injection site (75%). The most common systemic symptoms were fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia, and headache (50%). 14 The overall incidence of serious adverse events did not differ significantly between groups and no deaths occurred in relation to the vaccine. While this vaccine is already being administered, further investigations are still necessary to establish safety and efficacy profiles for populations not included in this study as well as to assess its long-term effects. Current contraindications of the mRNA-1273 vaccine include any persons with known allergy to polyethylene glycol (PEG), another mRNA vaccine component or polysorbate. 15

AstraZeneca

The Oxford and AstraZeneca ChAdOx1 COVID-19 vaccine uses a chimpanzee adenovirus vector to deliver the genetic sequence of a full-length spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 into host cells. 16 The storage for the ChAdOx1 vaccine is favorable, as it may be refrigerated at 2°C–8°C for 6 months. Pooled analysis of four ongoing clinical studies was used to assess efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of the ChAdOx1 vaccine: COV001 (phase 1/2), COV002 (phase 2/3), COV003 (phase 3), and COV005 (phase 1/2). 17 Across the four studies participants over 18 were randomized to receive either the vaccine or a control (meningococcal group A, C, W, or saline). ChAdOx1 vaccine recipients received two standard doses (SDs) of the vaccine (SD/SD cohort) except for a subset in the COV002 trial who received a half lower dose (LD) followed by an SD (LD/SD cohort). 17 In the four studies, there was a total 23,848 participants, all of whom were used for gathering safety data; only 11,636 participants from the COV002 and COV003 trials were included in the primary efficacy analysis. 17 Of the 11,636 participants in the efficacy analysis, 2741 were in the LD/SD cohort, 88% were between 18 and 55 years old, and comorbidities present included cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, and diabetes. 17 The results show that in the intended dosing regimen (SD/SD cohort), the VE was 62.1% (95% CI, 41.0–75.7) ⩾14 days after the second injection for symptomatic COVID-19 (27 cases vs 71 cases respectively). 17 In the group that received an LD (LD/SD cohort), the VE was 90.0% (95% CI, 67.4–97.0; 3 cases vs 30 cases, respectively) while across the two dosing regimens the overall efficacy was 70.4% (95.8% CI, 54.8–80.6;30 cases vs 101 cases, respectively). 17 The higher efficacy observed in the LD/SD cohort can be attributed to this group having a longer dosing interval between the two doses in comparison to the SD/SD cohort. Regarding safety, most of the adverse events were mild-moderate with the most frequently reported being injection site pain/tenderness, fatigue, headache, malaise, and myalgia. 18 About 175 serious adverse events were noted, only three of which were possibly linked to intervention: transverse myelitis 14 days after second dose, haemolytic anemia in a control recipient and fever >40°C in a participant still masked to group allocation. One contraindication for use of the vaccine is hypersensitivity to any of its components. In very rare cases, AstraZeneca has been associated internationally with venous thromboembolic events with thrombocytopenia with current estimates being 10–15 cases per million vaccinated patients. 19 This adverse event has been termed thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS). In summary, these studies demonstrate that the AstraZeneca ChAdOx1 vaccine has a good efficacy and side-effect profile. Limitations include that less than 4% of participants were >70, no one over 55 got the mixed-dose regimen (LD/SD cohort), and those with comorbidities were a minority. Additional investigations are required to analyze long-term effects and assess efficacy and safety in populations not included or underrepresented.

Janssen COVID-19 vaccine

The Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) COVID-19 vaccine, developed by Janssen Pharmaceutical in Netherlands. It is a single-dose intramuscular (IM) vaccine that contains a recombinant, replication incompetent human adenovirus (Ad26) vector encoding the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 in the stabilized conformation. 20 It can be stored between 2°C and 8°C for up to 6 hours or at room temperature for a duration of 2 hours. The ENSEMBLE Phase-3 trial (n = 43,783) is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study which included participants ⩾18 years. Efficacy assessment was performed at day 14 and 28. The primary outcome only included moderate and severe (hospitalization and death) infection. Overall, the VE in the moderate to severe cohort was 66.9% (95% CI: 59.0–73.4) at 14 days and 66.1% (95% CI: 55.0–74.8) at 28 days. 20 In the severe cohort, the VE was 76.7% (95% CI: 54.6–89.1) and 85.4% (95% CI: 54.2–96.9) at day 14 and 28 days, respectively. 20 At the time of the study, 96.4% of the strains in the United States, 96.4% were identified as the Wuhan-H1 variant D614G. The VE in the United States for the moderate to severe cohort was 74.4% (95% CI: 65.0–81.6) and 72.0% (95% CI: 58.2–81.7) at 14 days and 28 days, respectively. 20 In the US severe cohort, the VE was 78.0% (95% CI: 33.1–94.6) and 85.9% (95% CI: −9.4 to 99.7) at day 14 and 28 days, respectively. 20 Alternatively, 94.5% of the strains in South Africa were identified as beta variant. The VE in South Africa for the moderate to severe cohort was 52.0% (95% CI: 30.3–67.4) and 64.0% (95% CI: 41.2–78.7) at 14 days and 28 days, respectively. 20 In the South African severe cohort, the VE was 73.1% (95% CI: 40.0–89.4) and 81.7% (95% CI: 46.2–95.4) at day 14 and 28 days, respectively. 20 In Brazil, 69.4% of the strains were identified as P.2 lineage variant and 30.6% were identified as Wuhan-H1 variant D614G. The VE in Brazil for the moderate to severe cohort was 66.2% (95% CI: 51.0–77.1) and 68.1% (95% CI: 48.8–80.7) at 14 days and 28 days, respectively. 20 In the Brazilian severe cohort, the VE was 81.9% (95% CI: 17.0–98.1) and 87.6% (95% CI: 7.8–99.7) at day 14 and 28 days, respectively. 20 The most common localized solitary adverse reaction was the injection site pain (48.6%). Conversely, the most common systemic adverse reactions included headache, fatigue, myalgia, and nausea. 20 In the post authorization phase, adverse reaction included anaphylaxis, thrombosis with thrombocytopenia, Guillain Barré syndrome, and capillary leak syndrome. 20 Overall, the data demonstrate that the Janssen vaccine has a good efficacy and side-effect profile.