An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Brexanolone, a neurosteroid antidepressant, vindicates the GABAergic deficit hypothesis of depression and may foster resilience

Bernhard lüscher, hanns möhler.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Email: [email protected]

No competing interests were disclosed.

Accepted 2019 May 22; Collection date 2019.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The GABAergic deficit hypothesis of depression states that a deficit of GABAergic transmission in defined neural circuits is causal for depression. Conversely, an enhancement of GABA transmission, including that triggered by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or ketamine, has antidepressant effects. Brexanolone, an intravenous formulation of the endogenous neurosteroid allopregnanolone, showed clinically significant antidepressant activity in postpartum depression. By allosterically enhancing GABA A receptor function, the antidepressant activity of allopregnanolone is attributed to an increase in GABAergic inhibition. In addition, allopregnanolone may stabilize normal mood by decreasing the activity of stress-responsive dentate granule cells and thereby sustain resilience behavior. Therefore, allopregnanolone may augment and extend its antidepressant activity by fostering resilience. The recent structural resolution of the neurosteroid binding domain of GABA A receptors will expedite the development of more selective ligands as a potential new class of central nervous system drugs.

Keywords: Major depressive disorder, anxiety, postpartum depression, rapid acting antidepressant, allopregnanolone, neurosteroid, GABA receptor

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) represents the most common cause of total psychophysiological disability with a worldwide lifetime prevalence of 12 to 20% and estimated annual costs to the US economy of more than $100 billion 1 – 3 . MDD is difficult to treat, in part because it is a phenotypically and etiologically heterogeneous syndrome 4 . Accordingly, it is challenging to conceive of a single mechanism that could account for most forms of this disease and of a treatment that might alleviate symptoms in the majority of patients. Indeed, current first-line antidepressants that are designed to modulate monoaminergic transmitter systems separate from placebo in only about 50% of clinical trials 5 , are effective in fewer than two thirds of patients subjected to one or two regimens of treatment 6 , and act with a delay of several weeks to months 7 . Even among patients who respond to these treatments, only a small fraction show remission. These features often lead to endless and futile pursuits of an effective treatment and illustrate the enormous unmet need for better antidepressant therapies. Here, we summarize the GABAergic deficit hypothesis of depression and its clinical support by the neurosteroid brexanolone, which largely acts by enhancing GABAergic inhibition.

The GABAergic deficit hypothesis of depression

The GABAergic deficit hypothesis of MDD posits that diverse defects in GABAergic neural inhibition can causally contribute to common phenotypes of MDD and conversely that the efficacy of current and future antidepressant therapies depends on their ability to restore GABAergic neurotransmission 8 , 9 . Consistent with this hypothesis, clinical studies over the past 15 years have provided compelling evidence that MDD is associated with diverse defects in GABAergic neurotransmission. This includes well-replicated findings of reduced brain levels of GABA 10 – 12 , reduced expression of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) as the principal enzyme responsible for GABA synthesis by GABAergic interneurons 13 , 14 , reduced density or function of GABAergic interneurons 15 – 17 , and reduced expression and function of the principal receptors for GABA known as GABA A receptors 18 – 20 . Together, these changes explain the marked functional defects in cortical GABAergic inhibition observed in patients with MDD 21 .

Beyond MDD, GABAergic deficits are also broadly implicated in anxiety disorders, which are highly comorbid with MDD 22 but may have distinct developmental origins 23 . Compared with other neuropsychiatric disorders, MDD shows low heritability of about 38% 24 . Even this low heritability remains unexplained as attempts to replicate the identification of candidate genes of MDD have been failing 25 , 26 . Therefore, rather than relying on genetic models to explore disease mechanism, pre-clinical models of MDD are often based on the notion that chronic stress represents a major environmental vulnerability and precipitating factor of MDD. Consistent with a causative role of stress for MDD, chronic exposure of rodents to stress results in diverse behavioral alterations in a direction opposite to those induced by antidepressant drug treatment, and antidepressant drug treatments prevent or ameliorate the detrimental effects of stress in these models 27 , 28 . Chronic stress also results in reduced production and survival of adult-born hippocampal granule cell neurons and these cells are essential for at least some of the behavioral actions of antidepressants 29 . Importantly, stress-induced behavioral alterations of rodents are associated with impairment of GABAergic interneurons, reduced expression of GAD and of the vesicular and plasma membrane transporters for GABA, and reduced density and function of GABAergic synapses 30 – 34 . In addition, chronic stress leads to marked deficits in the synthesis of endogenous GABA-potentiating neurosteroids, as detailed below. Lastly, chronic stress also leads to a shift in the chloride reversal potential to more depolarized membrane potentials, which renders GABAergic inhibition ineffective 35 , 36 . In corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) neurons of the hypothalamus, corresponding stress-induced loss of inhibitory drive leads to chronic hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis activation 35 . Thus, stress-induced defects in GABAergic inhibition are self-perpetuating because they exacerbate stress-induced glutamate release and lead to chronically dysregulated stress axis function. Conversely, mechanisms that enhance GABAergic inhibition are predicted to confer stress resilience, a process that has been described by the American Psychological Association as “adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy threats or significant sources of stress” (American Psychological Association, www.apa.org/helpcenter/road-resilience , last checked April 25, 2019).

Some of the most compelling evidence that defects in GABA transmission can causally contribute to stress-induced anxiety- and depressive-like symptoms is available from analyses of GABA A receptor mutant mice. Knockout mice that were rendered heterozygous for the γ2 subunit (γ2 +/− mice, lacking one of 38 gene alleles that contribute to heteropentameric GABA A receptors) exhibit anxiety- and depression-related behavior, defects in hippocampal neurogenesis, cognitive deficits in emotional pattern separation, and chronic HPA axis activation that are expected of an animal model of MDD 23 , 37 – 40 . Some of these same behavioral defects have been described in mice lacking the α2 subunit of GABA A receptors 41 or the neurosteroid binding site of α2 GABA A receptors 42 and in mice with genetically reduced GABA synthesis 43 .

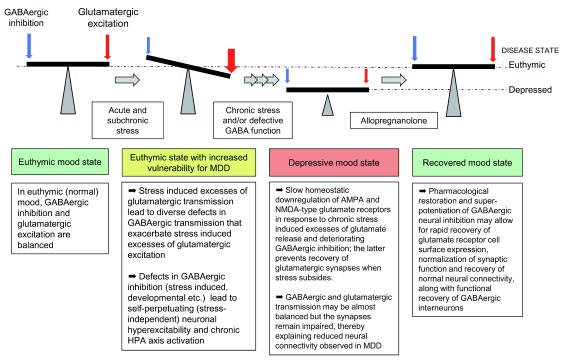

Chronic stress and defects in GABAergic transmission of γ2 +/− mice further have in common that they result in similar homeostatic-like downregulation of ionotropic glutamate receptors (AMPA and NMDA receptors) and glutamatergic synaptic transmission ( Figure 1 ) 44 – 46 . The anxious and depression-related behavior and the functional defects in GABAergic and glutamatergic synaptic transmission of γ2 +/− mice can be reversed for a prolonged period with the rapid-acting antidepressant ketamine 46 (see below). Such defects in functional neural connectivity and their rescue by antidepressant therapies represent functional hallmarks of MDD 47 , 48 . Importantly, chronic treatment of γ2 +/− mice with the norepinephrine (NE) reuptake inhibitor desipramine is able to similarly normalize the behavior of γ2 +/− mice along with normalization of HPA axis function in these mice 40 . Chronic stress–induced or optogenetic activation of NE neurons of the locus coerulus (LC) that project to dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) mediates resilience to chronic social defeat stress of mice 49 . In the VTA, LC-derived NE acts through α1- and β3-adrenergic receptors to induce homeostatic alterations of ion channel expression in DA neurons that contribute to stress resilience. Accordingly, we speculate that hyperexcitability of LC NE neurons in γ2 +/− mice facilitates the antidepressant action of NE reuptake inhibitors to induce slow homeostatic changes in DA neurons that underlie stress resilience. Thus, both conventional antidepressants and ketamine can act to overcome genetic (that is, hard-wired) defects in GABAergic synaptic transmission, albeit by entirely different mechanisms. Moreover, directly and deliberately increasing the excitability of certain subsets of GABAergic interneurons in mice has robust anxiolytic and antidepressant-like behavioral and biochemical consequences 50 . Collectively, these findings lend strong support to the GABAergic deficit hypothesis of MDD and suggest that certain (but not all) agents that enhance GABAergic inhibition may have antidepressant properties 8 , 9 . For example, benzodiazepines, which act as positive allosteric modulators of GABA A receptors and are first-line treatments for anxiety disorders, have only limited efficacy as antidepressants 51 , even though they are often used to augment conventional antidepressants and to treat comorbidities of MDD, such as anxiety and insomnia 52 – 55 . Limited antidepressant efficacy of benzodiazepines may be due to tolerance, which is thought to involve chronic drug-induced degradation of major subsets of GABA A receptors and corresponding loss of inhibitory synapses 56 , 57 . However, two negative allosteric modulators of α5-GABA A receptors—L-655,708 and MRK-016—have been shown to exhibit rapid antidepressant-like activity in a chronic stress model of rodents 44 , 58 . Notably, in contrast to benzodiazepines and comparable to ketamine (discussed in the following), these agents act by transient disinhibition of neural circuits, which results in antidepressant-like activity in the “drug-off” situation.

Figure 1. Schematic of chronic stress and GABAergic deficit-induced downregulation of glutamatergic transmission and recovery by allopregnanolone.

HPA, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal; MDD, major depressive disorder.

The antidepressant mechanism of ketamine is unique in that it is very rapid and has the clinical benefits observed in the “drug-off” situation following a single acute dose of the drug. Recent progress in understanding of its mechanism has been thoroughly reviewed elsewhere 59 , 60 and is only briefly recapitulated here. Key aspects of the antidepressant mechanism of ketamine are that it involves brief inhibition of GABAergic interneurons 61 followed by a transient surge in glutamate release 62 (lasting at most 1 hour) that then triggers the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) 63 and a wave of synaptogenesis 64 . The ensuing increase in synapse density, the corresponding restoration of neural connectivity, and normalized emotional behavior are all observed in the drug-off state and last for several days. Notably, ketamine-induced synaptogenesis and antidepressant behavioral response are drastically enhanced by GABAergic deficits, as observed in γ2 +/− mice 46 and also evident in animals exposed to chronic stress 65 , 66 , perhaps because neural hyperexcitability in these models facilitates the ketamine-induced glutamate surge and BDNF release. Importantly, restoration of glutamatergic synapses in γ2 +/− mice is associated with even more dramatic formation and pre- and post-synaptic potentiation of GABAergic synapses 46 , which appears to ensure that inhibitory and excitatory synaptic transmission remain balanced. Indeed, we found no evidence in the literature that ketamine treatment triggers seizures, despite the glutamate surge and evidence of a reduced seizure threshold in patients with MDD 67 . Similar to restoration of glutamatergic synapses, ketamine-induced strengthening of GABAergic synapses is long-lasting and observed in the drug-off situation 46 and temporally separated from the initial direct action of ketamine at GABAergic interneurons mentioned above. Here, we propose that direct and potent pharmacological enhancement of GABAergic transmission (that is, by allopregnanolone) will act accordingly to transiently dampen glutamate release and allow for lasting recovery of glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic transmission beyond the end of treatment ( Figure 1 ).

Neurosteroids differentially modulate phasic and tonic GABAergic inhibition

Neurosteroids are metabolites of cholesterol-derived steroid hormones synthesized in the brain by neurons and astrocytes. They act as potent, endogenous, positive allosteric modulators of GABA A receptors and include derivatives of progesterone and deoxycorticosterone, in particular 3a,5a-tetrahydroprogesterone (3α,5α-THP; allopregnanolone), 3α,5β-tetrahydro-progesterone (3α,5β-THP; pregnanolone), and 3α,5α tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone (3α,5α-THDOC; allotetrahydro-deoxycorticosterone).

Neurosteroids such as allopregnanolone have little effect on the rise time or the amplitude of GABA-induced synaptic currents but primarily prolong the decay kinetics of the GABA-gated ion channel 68 , which results in an increase of the mean channel open time of the GABA-activated chloride channel and a prolonged inhibitory post-synaptic current. However, when acting on extra-synaptic receptors that are kept tonically active by ambient concentrations of GABA, the allopregnanolone-induced prolonged decay kinetic results in an increased amplitude of the tonic current. In addition to potentiation of GABA A receptor channel function 69 , 70 , allopregnanolone and its synthetic derivatives may potentiate GABA transmission by promoting the cell surface expression of GABA A receptors 71 . The impact on phasic or tonic inhibition can be strikingly different because of the type of GABA A receptor subtype involved. The prototypic synaptic receptor contains α1, β2/3, and γ2 subunits and is sensitive to physiological concentrations of neurosteroids 68 . However, in certain cells, such as dentate gyrus (DG) granule cells or cerebellar granule cells, allopregnanolone at low concentrations (10–100 nM) selectively enhances tonic inhibition with little or no effect on phasic conductance. This appears to be due largely to the preponderance of highly neurosteroid-sensitive extra-synaptic δ subunit–containing receptors with the subunit combinations α4,β3,δ, and α6,β2,3,δ 72 – 74 . In addition, phosphorylation of the β3 subunit by protein kinase C appears to promote neurosteroid sensitivity of extra-synaptic receptors while limiting that of synaptic receptors 75 . In some neurons, the strict division of GABA A receptors into synaptic and extra-synaptic receptors mediating phasic and tonic inhibition, respectively, has become an oversimplification 76 . The therapeutic action of brexanolone (peak steady-state plasma concentration of about 150 nM; see below) is likely to comprise an enhancement of both phasic and tonic inhibition.

Downregulation of neurosteroids in affective disorders

The downregulation of neurosteroid biosynthesis has been implicated as a possible contributor to various psychiatric conditions, as shown in a number of clinical trials. In patients with MDD, allopregnanolone and pregnanolone were decreased in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) 77 and in plasma 78 , 79 . Plasma allopregnanolone was similarly decreased in postpartum “blues” 80 (but see below), post-traumatic stress disorder 81 , 82 , schizophrenia negative symptomatology 83 , pain 84 , and pharmacologically induced panic attacks 85 but did not reach significance in general anxiety disorder 86 . Conversely, the 3β isomer of allopregnanolone antagonizes GABA A receptor function 87 and is increased in panic attacks 88 . Based on studies of postmortem brain, changes in the neurosteroid synthesis pathways were also proposed to contribute to the pathologies of neurodegenerative and inflammatory diseases (Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis) 89 .

Stress-induced behavior linked to downregulation of neurosteroids

Because chronic stress is a major risk factor for depression, the influence of chronic stress on neurosteroids has become a major focus. In striking contrast to acute stress, which increases allopregnanolone levels 89 , 90 , chronic stress and pharmacological induction of panic attacks 84 result in reduced levels of neurosteroids. In animal models of chronic stress, the concentration of allopregnanolone was decreased in serum 91 – 93 and in selected corticolimbic brain areas 94 . This decrease was attributed to stress-induced downregulation of the 5α-hydroxysteroid-dehydrogenase, the rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of allopregnanolone 92 , 95 , 96 . Moreover, the stress-induced reduction of allopregnanolone was associated with heightened depressive/anxiety-like behavioral phenotypes, increased fear and aggression behavior, dysregulation of the HPA axis 92 , 94 , 97 , and impaired adult hippocampal neurogenesis 98 , 99 .

Allopregnanolone ameliorates anxiety- and depression-related behavior

Administration of allopregnanolone either before or after a period of chronic stress was able to alleviate the symptoms of depressive/anxiety behavior, prevent or normalize HPA axis dysfunction, and restore neurogenesis and cognitive deficits in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease 99 – 101 . Furthermore, allopregnanolone and pregnanolone produced anxiolytic-like effects in various animal models of anxiety 102 . Micro-infusion of allopregnanolone identified the amygdala as being relevant for anxiolysis 103 and both the hippocampus and amygdala for overcoming learned helplessness 104 . These results support a role of allopregnanolone in ameliorating symptoms of depression and anxiety and thereby support the view that a pathological deficit of GABAergic transmission contributes to these disorders 8 , 9 , 105 .

Classic antidepressants normalize neurosteroid levels in depression

With allopregnanolone being able to overcome depressive-like behavior, the question arose whether classic antidepressant drugs would act via an enhancement of neurosteroid levels. In animal models of depression, multiple antidepressants (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, desipramine, venlafaxine, and paroxetine) normalized corticolimbic levels of allopregnanolone concomitant with reduced anxiety-like, fear, and aggression behavior 83 , 92 , 106 , 107 . This effect, as shown for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), was independent of their ability to inhibit serotonin reuptake 108 – 110 and in the case of fluoxetine is thought to involve inhibition of a microsomal dehydrogenase that oxidizes allopregnanolone to 5α-dihydroprogesterone 111 .

These findings gave reason to test whether the clinical effectiveness of SSRIs was linked to normalizing the allopregnanolone level. Indeed, in patients with unipolar depression, the decreased allopregnanolone level, measured in CSF, was normalized after 8 to 10 weeks of treatment with fluoxetine or fluvoxamine and correlated with an improved symptomatology 77 . This finding was extended to a range of antidepressants (SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants), which normalized plasma allopregnanolone levels concomitant with an improvement of depression 109 . A normalization of plasma allopregnanolone and pregnenolone was also seen following 3 weeks of mirtazapine treatment in patients with major depression 79 . Notably, the mirtazapine-induced maximal increases in these neurosteroids preceded their maximal clinical effects by about 2 weeks, suggesting that they are part of the pharmacological response mechanism rather than a subsequent measure of clinical improvement. These pre-clinical and clinical findings support the view that the neurosteroidogenic action of SSRIs may constitute a major part of their therapeutic effectiveness in patients with depressive disorders.

Postpartum risk of depression

Postpartum depression (PPD) is an important public health issue as it affects women at a highly vulnerable time and can affect the cognitive and emotional development of the child 112 . The risk of depression in women becomes significantly increased during the postpartum period, and nearly 20% of mothers have PPD, which is frequently preceded by antenatal anxiety- and depression-related symptoms or chronic stress as the strongest predictors 113 – 115 . PPD is frequently attributed to a maladaptation to peripartum fluctuations in reproductive hormone levels during pregnancy and the postpartum period 116 , 117 . Plasma allopregnanolone concentrations rise in parallel with progesterone throughout pregnancy, reaching the highest level in the third trimester and decreasing abruptly after childbirth 80 .

Nevertheless, peripartum changes in gonadal hormones affect the emotional brain in vulnerable women. PPD was characterized by abnormal activation of the same brain regions implicated in non-puerperal major depression 118 . The resting-state functional connectivity within corticolimbic regions implicated in depression was attenuated compared with healthy postpartum women 114 . Similarly, emotionally normal (euthymic) women with a history of PPD showed stronger signs of depression than controls in tests of withdrawal from supra-physiological gonadal steroid levels 119 . Additional factors that have been implicated in the pathophysiology of PPD include the lactogenic hormones oxytocin and prolactin, thyroid function, and a hyperactivity of the HPA axis 117 . As outlined below, the potential importance of GABA A receptor plasticity in PPD has been derived largely from animal studies 120 .

Animal models of postpartum depression and GABAergic impact

Rodent models suggest that both phasic and tonic GABAergic inhibition in the brain are decreased during pregnancy in parallel with a decrease in GABA A receptor expression as shown for the GABA A receptor γ2 and δ subunit in mouse and rat hippocampus 121 . Within days after parturition, GABAergic transmission and the level of GABA A receptor expression rebound to control levels 121 , 122 . This fluctuation in receptor expression is considered to be a homeostatic response to the elevated levels of pregnenolone and allopregnanolone in plasma and brain during rodent pregnancy and their rapid return to control levels postpartum 122 , 123 .

A transgenic animal model of PPD supports the view that the pathophysiology of PPD may be related to a deficit of GABA A receptor plasticity. Mice that lacked the GABA A receptor δ subunit partly or fully ( Gabrd +/− and Gabrd −/− ) exhibited PPD-like behavior (reduced latency to immobility in the Porsolt forced swim test and reduced sucrose preference) and abnormal maternal behavior (reduced nesting behavior and pup care) 121 . Remarkably, the mice were behaviorally unremarkable until an animal was exposed to pregnancy and the postpartum state. Thus, reproductive events unmask the genetic susceptibility to affective dysregulation. The abnormal postpartum behavior in Gabrd +/− mice was ameliorated by THIP, a GABA analogue with preferential affinity to GABA A receptors containing the δ subunit 121 and the neuroactive steroid SGE-516 115 .

Another animal model suggests that the dysregulation of the HPA axis is sufficient to induce abnormal postpartum behavior 115 . CRH neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus govern the HPA axis and are critical for mounting the physiological response to stress. Chemogenetic activation of CRH neurons in the PVN was sufficient to induce abnormal postpartum behavior. Similarly, when GABAergic currents were reduced selectively in CRH neurons (KCC2/Crh mice), a depression-related phenotype and a deficit in maternal behavior were apparent in the postpartum period. In wild-type mice, the stress-induced activation of the HPA axis and the corresponding elevation of circulating corticosterone are normally blunted during pregnancy and postpartum 124 . The inability to blunt this stress-induced HPA axis activation in this model is thought to contribute to PPD. The neuroactive steroid SGE-516 ameliorated the behavioral deficits caused by the dysregulation of the HPA axis 115 .

Brexanolone in the treatment of postpartum depression

In line with the evidence described above, brexanolone, an intravenous formulation of allopregnanolone, underwent clinical tests to treat PPD. In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase II trial, female in-patients with PPD (n = 21) received a 60-hour continuous infusion of brexanolone at a dose of up to 60 μg/kg per hour or placebo. Women who received treatment, in comparison with those who received placebo, had a significant and clinically meaningful reduction in mean total score on the 17-item HAMILTON Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) at the 60-hour time point 125 . In a subsequent phase III study with 246 patients, performed in two parts using the same design but two doses of drug, the HAM-D score was again significantly and clinically meaningfully decreased. The HAM-D total score mean reductions versus placebo were −5.5 and −3.7 points for the high and low dose, respectively (90 and 60 μg/kg per hour), and dizziness and somnolence were potential side effects 126 . Notably, brexanolone is very rapidly cleared from plasma, which explains the need for continuous drug infusion 127 . The higher dose explored above (90 μg/kg per hour) results in peak steady-state plasma concentrations of allopregnanolone (50 ng/mL) equivalent to those naturally reached in the third trimester of pregnancy 128 . The antidepressant drug effect was shown to become significant within 48 hours of drug infusion for both doses. Moreover, the mean reduction in HAM-D total scores observed for the high-dose treatment at the end of the study (day 30) was similar in magnitude to that observed at the end of the 60-hour infusion. Thus, in the context of PPD, brexanolone showed a rapid mode of action that is reminiscent of that of ketamine in MDD and appears to result in durable clinical improvement ( Figure 1 ). Brexanolone was very recently approved for the treatment of PPD 129 .

Although a decrease in serum allopregnanolone (but not progesterone) was reported in one study in women with postpartum “blues” 80 , there is no consistent evidence of abnormal basal circulating levels of allopregnanolone in PPD 114 , 116 , 117 , 130 . With allopregnanolone levels being normal, the antidepressant action of brexanolone is attributed to an enhancement of GABA A receptor function, thereby supporting the GABAergic deficit hypothesis of depression. In addition, emerging evidence suggests that allopregnanolone has anti-inflammatory effects in vitro , a property that could contribute to its antidepressant activity in vivo 78 . The antidepressant properties of brexanolone in PPD may be applicable to other forms of depression that are less clearly linked to altered neurosteroid physiology and that may be associated with defects in phasic rather than tonic GABAergic inhibition 113 , 114 , 118 . Indeed, emerging evidence suggests that the anxiolytic effects of endogenous neurosteroids (even at their natural physiological concentrations) are mediated in part by α2 subunit–containing synaptic GABA A receptors 42 . Moreover, a synthetic derivative of allopregnanolone (zuranolone, SAGE-217) is currently in phase 3 clinical development for PPD and MDD 131 . Notably, potentiation of GABA transmission by brexanolone and potentially also zuranolone, unlike SSRIs that exhibit therapeutic delays of weeks or months, confers rapid and lasting antidepressant effects that are observed in the drug-off situation, reminiscent of mechanisms of ketamine. Interestingly, since allopregnanolone promotes proliferation of progenitor cells and restores neurogenesis in disease states 99 – 101 , 132 , it may also support neurogenesis-dependent resilience behavior, as outlined below.

Resilience due to changes in neural circuits

Studies of stress resilience have opened up a fundamentally new way of understanding an individual’s response to adverse life events such as trauma, tragedy, and chronic stress and its ability to avoid deleterious behavioral changes such as anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, or depression. Although resilience, as defined in humans, is difficult to relate to animal studies, animal models are indispensable in the search for biological determinants of resilience (that is, protective changes that occur in resilient animals). This is all the more important as mechanisms that promote resilience to stress hold the promise of enabling the development of more efficacious antidepressant therapies.

After chronic social defeat stress, about 40% of the stressed mice do not exhibit social avoidance or anhedonia in subsequent testing 133 , 134 . This is interpreted as resilience behavior and is associated with many distinct changes, particularly in the brain’s reward regions 133 – 135 . These changes include homeostatic adaptations of dopamine neurons in the VTA that prevent chronic stress–induced aberrant hyperexcitability of these cells 49 , 136 , 137 , the induction of immediate early gene products in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) 138 , the sustainment of GABAergic inhibition and reduction of excitatory activity in the nucleus accumbens 139 , the prevention of spine density loss in the mPFC and hippocampus 140 , and epigenetic genomic changes that promote resilience in later life because of greater maternal care 141 , 142 .

Adult neurogenesis linked to resilience via GABAergic inhibition

More recently, adult neurogenesis in the DG of the hippocampus has been implicated in conferring resilience to the detrimental depressive-like consequences of chronic stress exposure of mice 143 . Chemogenetic inhibition of immature adult-born neurons in ventral DG (vDG) in vivo promoted susceptibility to social defeat stress. In contrast, increasing neurogenesis by inducible deletion of the proapoptotic gene Bax (iBax mice) selectively from adult neural progenitor cells conferred resilience to chronic stress as measured by the time spent socially interacting with a novel mouse and the time spent exploring the center in an open field. On the cellular level, a subset of mature DG cells was identified as stress-responsive cells that were active preferentially during attack (17% of cells on defeat day 1 to 34% of cells on defeat day 10). The activity of the stress-responsive mature cells was decreased when neurogenesis was increased. Thus, immature adult-born granule cells inhibit mature stress-responsive granule cells in the vDG, which protects the animals from chronic stress–induced depressive and anxiety-like consequences. The inhibition of mature granule cells by immature adult-born cells is likely to involve activation of hilar GABAergic interneurons that are known to confer a strong inhibitory influence on mature granule cells 144 . Neurosteroids are predestined to inhibit DG granule cells because of their high level of expression of δ subunit–containing GABA A receptors, which are highly neurosteroid-sensitive 68 , 72 – 74 .

The finding that GABAergic interneuron activity can support resilience may give rise to a potential GABAergic hypothesis of resilience, which conceivably is independent of the prerequisite of adult neurogenesis. Decreased GABAergic interneuron activity would be expected to reduce resilience behavior whereas enhancing GABAergic transmission would sustain it. The neurosteroid allopregnanolone appears to be a case in point. Its clinical effectiveness as an antidepressant in treating PPD might be supported, at least in part, by its ability to foster resilience.

The demonstration of the clinical effectiveness of allopregnanolone in PPD lends new support to the GABAergic deficit hypothesis of MDD. This finding bodes well for further investigations of ligands for the neurosteroid site as a new class of drugs for affective disorders. To achieve this goal, a differentiation of GABA A receptors beyond that achieved by allopregnanolone is required. The recent molecular x-ray resolution of the neurosteroid binding domain is an essential step forward. In chimeric homopentameric GABA A receptor constructs, the neurosteroid THDOC was bound at the bottom of the transmembrane domain across each of the subunit interfaces 145 – 147 and similar findings are expected for heteropentameric GABA A receptors 145 , 148 . These studies provide a structural framework for the development of more selective ligands acting at the neurosteroid site for the treatment of affective disorders, including PPD and MDD, but also pain and epilepsy.

Editorial Note on the Review Process

F1000 Faculty Reviews are commissioned from members of the prestigious F1000 Faculty and are edited as a service to readers. In order to make these reviews as comprehensive and accessible as possible, the referees provide input before publication and only the final, revised version is published. The referees who approved the final version are listed with their names and affiliations but without their reports on earlier versions (any comments will already have been addressed in the published version).

The referees who approved this article are:

Trevor Smart , Department of Neuroscience, Physiology & Pharmacology, University College London, London, WC1E 6BT, UK

Istvan Mody , Departments of Neurology and Physiology, The David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, 90095, USA

Rainer Rupprecht , Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany

Jeremy Lambert , Department of Neuroscience, Division of Systems Medicine, Ninewells Hospital & Medical School, Dundee University, Dundee, DD19SY, UK

Funding Statement

Research in the laboratory of BL is supported by grant MH099851 from the National Institute of Mental Health. BL also consults for Lactocore, Inc.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; peer review: 4 approved]

- 1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. : The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–105. 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Belmaker RH, Agam G: Major depressive disorder. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(1):55–68. 10.1056/NEJMra073096 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Milane MS, Suchard MA, Wong ML, et al. : Modeling of the temporal patterns of fluoxetine prescriptions and suicide rates in the United States. PLoS Med. 2006;3(6):e190. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030190 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Kendler KS: The Phenomenology of Major Depression and the Representativeness and Nature of DSM Criteria. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(8):771–80. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15121509 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Khan A, Khan SR, Walens G, et al. : Frequency of positive studies among fixed and flexible dose antidepressant clinical trials: an analysis of the food and drug administration summary basis of approval reports. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(3):552–7. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300059 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. : Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905–17. 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1905 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Insel TR, Wang PS: The STAR*D trial: revealing the need for better treatments. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(11):1466–7. 10.1176/ps.2009.60.11.1466 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Luscher B, Shen Q, Sahir N: The GABAergic deficit hypothesis of major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16(4):383–406. 10.1038/mp.2010.120 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Luscher B, Fuchs T: GABAergic control of depression-related brain states. Adv Pharmacol. 2015;73:97–144. 10.1016/bs.apha.2014.11.003 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 10. Sanacora G, Gueorguieva R, Epperson CN, et al. : Subtype-specific alterations of gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate in patients with major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(7):705–13. 10.1001/archpsyc.61.7.705 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Hasler G, van der Veen JW, Tumonis T, et al. : Reduced prefrontal glutamate/glutamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid levels in major depression determined using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(2):193–200. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.193 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Gabbay V, Mao X, Klein RG, et al. : Anterior cingulate cortex γ-aminobutyric acid in depressed adolescents: relationship to anhedonia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(2):139–49. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.131 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Karolewicz B, Maciag D, O'Dwyer G, et al. : Reduced level of glutamic acid decarboxylase-67 kDa in the prefrontal cortex in major depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13(4):411–20. 10.1017/S1461145709990587 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Guilloux JP, Douillard-Guilloux G, Kota R, et al. : Molecular evidence for BDNF- and GABA-related dysfunctions in the amygdala of female subjects with major depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(11):1130–42. 10.1038/mp.2011.113 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 15. Sibille E, Morris HM, Kota RS, et al. : GABA-related transcripts in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in mood disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14(6):721–34. 10.1017/S1461145710001616 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Rajkowska G, O'Dwyer G, Teleki Z, et al. : GABAergic neurons immunoreactive for calcium binding proteins are reduced in the prefrontal cortex in major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(2):471–82. 10.1038/sj.npp.1301234 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Maciag D, Hughes J, O'Dwyer G, et al. : Reduced density of calbindin immunoreactive GABAergic neurons in the occipital cortex in major depression: relevance to neuroimaging studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(5):465–70. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.027 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Klumpers UM, Veltman DJ, Drent ML, et al. : Reduced parahippocampal and lateral temporal GABA A -[ 11 C]flumazenil binding in major depression: preliminary results. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37(3):565–74. 10.1007/s00259-009-1292-9 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Yin H, Pantazatos SP, Galfalvy H, et al. : A pilot integrative genomics study of GABA and glutamate neurotransmitter systems in suicide, suicidal behavior, and major depressive disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2016;171B(3):414–26. 10.1002/ajmg.b.32423 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Poulter MO, Du L, Weaver IC, et al. : GABA A receptor promoter hypermethylation in suicide brain: implications for the involvement of epigenetic processes. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(8):645–52. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.028 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Levinson AJ, Fitzgerald PB, Favalli G, et al. : Evidence of cortical inhibitory deficits in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(5):458–64. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.025 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Murphy JM, Horton NJ, Laird NM, et al. : Anxiety and depression: a 40-year perspective on relationships regarding prevalence, distribution, and comorbidity. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109(5):355–75. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2003.00286.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Shen Q, Fuchs T, Sahir N, et al. : GABAergic control of critical developmental periods for anxiety- and depression-related behavior in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47441. 10.1371/journal.pone.0047441 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Kendler KS, Gatz M, Gardner CO, et al. : A Swedish national twin study of lifetime major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):109–14. 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.109 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric GWAS Consortium, Ripke S, Wray NR, et al. : A mega-analysis of genome-wide association studies for major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(4):497–511. 10.1038/mp.2012.21 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Border R, Johnson EC, Evans LM, et al. : No Support for Historical Candidate Gene or Candidate Gene-by-Interaction Hypotheses for Major Depression Across Multiple Large Samples. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(5):376–387. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18070881 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 27. Yan HC, Cao X, Das M, et al. : Behavioral animal models of depression. Neurosci Bull. 2010;26(4):327–37. 10.1007/s12264-010-0323-7 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Czéh B, Fuchs E, Wiborg O, et al. : Animal models of major depression and their clinical implications. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;64:293–310. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.04.004 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 29. Samuels BA, Hen R: Neurogenesis and affective disorders. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33(6):1152–9. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07614.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Czéh B, Varga ZK, Henningsen K, et al. : Chronic stress reduces the number of GABAergic interneurons in the adult rat hippocampus, dorsal-ventral and region-specific differences. Hippocampus. 2015;25(3):393–405. 10.1002/hipo.22382 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Varga Z, Csabai D, Miseta A, et al. : Chronic stress affects the number of GABAergic neurons in the orbitofrontal cortex of rats. Behav Brain Res. 2017;316:104–14. 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.08.030 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 32. Lin LC, Sibille E: Somatostatin, neuronal vulnerability and behavioral emotionality. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(3):377–87. 10.1038/mp.2014.184 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Ma K, Xu A, Cui S, et al. : Impaired GABA synthesis, uptake and release are associated with depression-like behaviors induced by chronic mild stress. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(10):e910. 10.1038/tp.2016.181 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 34. Banasr M, Lepack A, Fee C, et al. : Characterization of GABAergic marker expression in the chronic unpredictable stress model of depression. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks). 2017;1. 10.1177/2470547017720459 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Hewitt SA, Wamsteeker JI, Kurz EU, et al. : Altered chloride homeostasis removes synaptic inhibitory constraint of the stress axis. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12(4):438–43. 10.1038/nn.2274 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 36. MacKenzie G, Maguire J: Chronic stress shifts the GABA reversal potential in the hippocampus and increases seizure susceptibility. Epilepsy Res. 2015;109:13–27. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2014.10.003 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Crestani F, Lorez M, Baer K, et al. : Decreased GABA A -receptor clustering results in enhanced anxiety and a bias for threat cues. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(9):833–9. 10.1038/12207 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Earnheart JC, Schweizer C, Crestani F, et al. : GABAergic control of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in relation to behavior indicative of trait anxiety and depression states. J Neurosci. 2007;27(14):3845–54. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3609-06.2007 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Ren Z, Sahir N, Murakami S, et al. : Defects in dendrite and spine maturation and synaptogenesis associated with an anxious-depressive-like phenotype of GABA A receptor-deficient mice. Neuropharmacology. 2015;88:171–9. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.07.019 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Shen Q, Lal R, Luellen BA, et al. : gamma-Aminobutyric acid-type A receptor deficits cause hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis hyperactivity and antidepressant drug sensitivity reminiscent of melancholic forms of depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68(6):512–20. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.024 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Vollenweider I, Smith KS, Keist R, et al. : Antidepressant-like properties of α2-containing GABA A receptors. Behav Brain Res. 2011;217(1):77–80. 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.10.009 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Durkin EJ, Muessig L, Herlt T, et al. : Brain neurosteroids are natural anxiolytics targeting α2 subunit γ-aminobutyric acid type-A receptors. BioRxiv. Preprint first posted online Nov. 8, 2018,2018. 10.1101/462457 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Kolata SM, Nakao K, Jeevakumar V, et al. : Neuropsychiatric Phenotypes Produced by GABA Reduction in Mouse Cortex and Hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(6):1445–56. 10.1038/npp.2017.296 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 44. Fischell J, van Dyke AM, Kvarta MD, et al. : Rapid Antidepressant Action and Restoration of Excitatory Synaptic Strength After Chronic Stress by Negative Modulators of Alpha5-Containing GABAA Receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(11):2499–509. 10.1038/npp.2015.112 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 45. Yuen EY, Wei J, Liu W, et al. : Repeated stress causes cognitive impairment by suppressing glutamate receptor expression and function in prefrontal cortex. Neuron. 2012;73(5):962–77. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.033 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Ren Z, Pribiag H, Jefferson SJ, et al. : Bidirectional Homeostatic Regulation of a Depression-Related Brain State by Gamma-Aminobutyric Acidergic Deficits and Ketamine Treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(6):457–68. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.02.009 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Anderson RJ, Hoy KE, Daskalakis ZJ, et al. : Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment resistant depression: Re-establishing connections. Clin Neurophysiol. 2016;127(11):3394–405. 10.1016/j.clinph.2016.08.015 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 48. Abdallah CG, Averill CL, Salas R, et al. : Prefrontal Connectivity and Glutamate Transmission: Relevance to Depression Pathophysiology and Ketamine Treatment. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2017;2(7):566–74. 10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.04.006 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 49. Zhang H, Chaudhury D, Nectow AR, et al. : α 1 - and β 3 -Adrenergic Receptor-Mediated Mesolimbic Homeostatic Plasticity Confers Resilience to Social Stress in Susceptible Mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;85(3):226–36. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.08.020 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 50. Fuchs T, Jefferson SJ, Hooper A, et al. : Disinhibition of somatostatin-positive GABAergic interneurons results in an anxiolytic and antidepressant-like brain state. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(6):920–30. 10.1038/mp.2016.188 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 51. Benasi G, Guidi J, Offidani E, et al. : Benzodiazepines as a Monotherapy in Depressive Disorders: A Systematic Review. Psychother Psychosom. 2018;87(2):65–74. 10.1159/000486696 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Petty F, Trivedi MH, Fulton M, et al. : Benzodiazepines as antidepressants: does GABA play a role in depression? Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38(9):578–91. 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00049-7 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. Birkenhäger TK, Moleman P, Nolen WA: Benzodiazepines for depression? A review of the literature. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;10(3):181–95. 10.1097/00004850-199510030-00008 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Furukawa TA, Streiner DL, Young LT: Antidepressant and benzodiazepine for major depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002; (1):CD001026. 10.1002/14651858.CD001026 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Delamarre L, Galvao F, Gohier B, et al. : How Much Do Benzodiazepines Matter for Electroconvulsive Therapy in Patients With Major Depression? J ECT. 2019. 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000574 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. Jacob TC, Michels G, Silayeva L, et al. : Benzodiazepine treatment induces subtype-specific changes in GABA A receptor trafficking and decreases synaptic inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(45):18595–600. 10.1073/pnas.1204994109 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. Nicholson MW, Sweeney A, Pekle E, et al. : Diazepam-induced loss of inhibitory synapses mediated by PLCδ/ Ca 2+ /calcineurin signalling downstream of GABAA receptors. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(9):1851–67. 10.1038/s41380-018-0100-y [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 58. Zanos P, Nelson ME, Highland JN, et al. : A Negative Allosteric Modulator for α5 Subunit-Containing GABA Receptors Exerts a Rapid and Persistent Antidepressant-Like Action without the Side Effects of the NMDA Receptor Antagonist Ketamine in Mice. eNeuro. 2017;4(1): pii: ENEURO.0285-16.2017. 10.1523/ENEURO.0285-16.2017 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 59. Duman RS, Shinohara R, Fogaça MV, et al. : Neurobiology of rapid-acting antidepressants: convergent effects on GluA1-synaptic function. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. 10.1038/s41380-019-0400-x [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 60. Zanos P, Thompson SM, Duman RS, et al. : Convergent Mechanisms Underlying Rapid Antidepressant Action. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(3):197–227. 10.1007/s40263-018-0492-x [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 61. Widman AJ, McMahon LL: Disinhibition of CA1 pyramidal cells by low-dose ketamine and other antagonists with rapid antidepressant efficacy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(13):E3007–E3016. 10.1073/pnas.1718883115 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 62. Chowdhury GM, Zhang J, Thomas M, et al. : Transiently increased glutamate cycling in rat PFC is associated with rapid onset of antidepressant-like effects. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(1):120–6. 10.1038/mp.2016.34 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 63. Autry AE, Adachi M, Nosyreva E, et al. : NMDA receptor blockade at rest triggers rapid behavioural antidepressant responses. Nature. 2011;475(7354):91–5. 10.1038/nature10130 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 64. Li N, Lee B, Liu RJ, et al. : mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science. 2010;329(5994):959–64. 10.1126/science.1190287 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 65. Li N, Liu RJ, Dwyer JM, et al. : Glutamate N -methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists rapidly reverse behavioral and synaptic deficits caused by chronic stress exposure. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(8):754–61. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.015 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 66. Fitzgerald PJ, Yen JY, Watson BO: Stress-sensitive antidepressant-like effects of ketamine in the mouse forced swim test. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0215554. 10.1371/journal.pone.0215554 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 67. Hesdorffer DC, Hauser WA, Annegers JF, et al. : Major depression is a risk factor for seizures in older adults. Ann Neurol. 2000;47(2):246–9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 68. Belelli D, Lambert JJ: Neurosteroids: endogenous regulators of the GABA A receptor. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(7):565–75. 10.1038/nrn1703 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 69. Majewska MD, Harrison NL, Schwartz RD, et al. : Steroid hormone metabolites are barbiturate-like modulators of the GABA receptor. Science. 1986;232(4753):1004–7. 10.1126/science.2422758 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 70. Paul SM, Purdy RH: Neuroactive steroids. FASEB J. 1992;6(6):2311–22. 10.1096/fasebj.6.6.1347506 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 71. Modgil A, Parakala ML, Ackley MA, et al. : Endogenous and synthetic neuroactive steroids evoke sustained increases in the efficacy of GABAergic inhibition via a protein kinase C-dependent mechanism. Neuropharmacology. 2017;113(Pt A):314–22. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.10.010 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 72. Sieghart W, Savić MM: International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. CVI: GABA A Receptor Subtype- and Function-selective Ligands: Key Issues in Translation to Humans. Pharmacol Rev. 2018;70(4):836–78. 10.1124/pr.117.014449 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 73. Fritschy JM, Panzanelli P: GABA A receptors and plasticity of inhibitory neurotransmission in the central nervous system. Eur J Neurosci. 2014;39(11):1845–65. 10.1111/ejn.12534 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 74. Rudolph U, Knoflach F: Beyond classical benzodiazepines: novel therapeutic potential of GABA A receptor subtypes. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(9):685–97. 10.1038/nrd3502 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 75. Adams JM, Thomas P, Smart TG: Modulation of neurosteroid potentiation by protein kinases at synaptic- and extrasynaptic-type GABA A receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2015;88:63–73. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.09.021 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 76. Herd MB, Brown AR, Lambert JJ, et al. : Extrasynaptic GABA A receptors couple presynaptic activity to postsynaptic inhibition in the somatosensory thalamus. J Neurosci. 2013;33(37):14850–68. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1174-13.2013 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 77. Uzunova V, Sheline Y, Davis JM, et al. : Increase in the cerebrospinal fluid content of neurosteroids in patients with unipolar major depression who are receiving fluoxetine or fluvoxamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(6):3239–44. 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3239 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 78. Murugan S, Jakka P, Namani S, et al. : The neurosteroid pregnenolone promotes degradation of key proteins in the innate immune signaling to suppress inflammation. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(12):4596–607. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.005543 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 79. Schüle C, Romeo E, Uzunov DP, et al. : Influence of mirtazapine on plasma concentrations of neuroactive steroids in major depression and on 3alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11(3):261–72. 10.1038/sj.mp.4001782 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 80. Nappi RE, Petraglia F, Luisi S, et al. : Serum allopregnanolone in women with postpartum "blues". Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(1):77–80. 10.1016/S0029-7844(00)01112-1 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 81. Rasmusson AM, Pinna G, Paliwal P, et al. : Decreased cerebrospinal fluid allopregnanolone levels in women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(7):704–13. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.026 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 82. Rasmusson AM, King MW, Valovski I, et al. : Relationships between cerebrospinal fluid GABAergic neurosteroid levels and symptom severity in men with PTSD. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;102:95–104. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.11.027 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 83. Marx CE, Keefe RS, Buchanan RW, et al. : Proof-of-concept trial with the neurosteroid pregnenolone targeting cognitive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(8):1885–903. 10.1038/npp.2009.26 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 84. Naylor JC, Kilts JD, Szabo ST, et al. : Allopregnanolone Levels Are Inversely Associated with Self-Reported Pain Symptoms in U.S. Iraq and Afghanistan-Era Veterans: Implications for Biomarkers and Therapeutics. Pain Med. 2016;17(1):25–32. 10.1111/pme.12860 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 85. Ströhle A, Romeo E, di Michele F, et al. : Induced panic attacks shift gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor modulatory neuroactive steroid composition in patients with panic disorder: preliminary results. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):161–8. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.161 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 86. Le Mellédo JM, Baker GB: Neuroactive steroids and anxiety disorders. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2002;27(3):161–5. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 87. Prince RJ, Simmonds MA: 5 beta-pregnan-3 beta-ol-20-one, a specific antagonist at the neurosteroid site of the GABAA receptor-complex. Neurosci Lett. 1992;135(2):273–5. 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90454-F [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 88. Luchetti S, Huitinga I, Swaab DF: Neurosteroid and GABA-A receptor alterations in Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis. Neuroscience. 2011;191:6–21. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.04.010 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 89. Girdler SS, Klatzkin R: Neurosteroids in the context of stress: implications for depressive disorders. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;116(1):125–39. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.05.006 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 90. Purdy RH, Morrow AL, Moore PH, Jr, et al. : Stress-induced elevations of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor-active steroids in the rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(10):4553–7. 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4553 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 91. Dong E, Matsumoto K, Uzunova V, et al. : Brain 5alpha-dihydroprogesterone and allopregnanolone synthesis in a mouse model of protracted social isolation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(5):2849–54. 10.1073/pnas.051628598 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 92. Matsumoto K, Pinna G, Puia G, et al. : Social isolation stress-induced aggression in mice: a model to study the pharmacology of neurosteroidogenesis. Stress. 2005;8(2):85–93. 10.1080/10253890500159022 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 93. Serra M, Pisu MG, Littera M, et al. : Social isolation-induced decreases in both the abundance of neuroactive steroids and GABA A receptor function in rat brain. J Neurochem. 2000;75(2):732–40. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750732.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 94. Pibiri F, Nelson M, Guidotti A, et al. : Decreased corticolimbic allopregnanolone expression during social isolation enhances contextual fear: A model relevant for posttraumatic stress disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(14):5567–72. 10.1073/pnas.0801853105 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 95. Agís-Balboa RC, Pinna G, Pibiri F, et al. : Down-regulation of neurosteroid biosynthesis in corticolimbic circuits mediates social isolation-induced behavior in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(47):18736–41. 10.1073/pnas.0709419104 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 96. Bortolato M, Devoto P, Roncada P, et al. : Isolation rearing-induced reduction of brain 5α-reductase expression: relevance to dopaminergic impairments. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60(7–8):1301–8. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.013 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 97. Nelson M, Pinna G: S-norfluoxetine microinfused into the basolateral amygdala increases allopregnanolone levels and reduces aggression in socially isolated mice. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60(7–8):1154–9. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.10.011 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 98. Snyder JS, Soumier A, Brewer M, et al. : Adult hippocampal neurogenesis buffers stress responses and depressive behaviour. Nature. 2011;476(7361):458–61. 10.1038/nature10287 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 99. Evans J, Sun Y, McGregor A, et al. : Allopregnanolone regulates neurogenesis and depressive/anxiety-like behaviour in a social isolation rodent model of chronic stress. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63(8):1315–26. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.08.012 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 100. Wang JM, Singh C, Liu L, et al. : Allopregnanolone reverses neurogenic and cognitive deficits in mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(14):6498–503. 10.1073/pnas.1001422107 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 101. Singh C, Liu L, Wang JM, et al. : Allopregnanolone restores hippocampal-dependent learning and memory and neural progenitor survival in aging 3xTgAD and nonTg mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(8):1493–506. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.06.008 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 102. Schüle C, Nothdurfter C, Rupprecht R: The role of allopregnanolone in depression and anxiety. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;113:79–87. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.09.003 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 103. Engin E, Treit D: The anxiolytic-like effects of allopregnanolone vary as a function of intracerebral microinfusion site: the amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, or hippocampus. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18(5–6):461–70. 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282d28f6f [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 104. Shirayama Y, Muneoka K, Fukumoto M, et al. : Infusions of allopregnanolone into the hippocampus and amygdala, but not into the nucleus accumbens and medial prefrontal cortex, produce antidepressant effects on the learned helplessness rats. Hippocampus. 2011;21(10):1105–13. 10.1002/hipo.20824 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 105. Möhler H: The GABA system in anxiety and depression and its therapeutic potential. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(1):42–53. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.08.040 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 106. Nin MS, Martinez LA, Pibiri F, et al. : Neurosteroids reduce social isolation-induced behavioral deficits: a proposed link with neurosteroid-mediated upregulation of BDNF expression. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2011;2:73. 10.3389/fendo.2011.00073 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 107. Uzunova V, Wrynn AS, Kinnunen A, et al. : Chronic antidepressants reverse cerebrocortical allopregnanolone decline in the olfactory-bulbectomized rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;486(1):31–4. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.12.002 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 108. Guidotti A, Costa E: Can the antidysphoric and anxiolytic profiles of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors be related to their ability to increase brain 3 alpha, 5 alpha-tetrahydroprogesterone (allopregnanolone) availability? Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44(9):865–73. 10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00070-5 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 109. Romeo E, Ströhle A, Spalletta G, et al. : Effects of antidepressant treatment on neuroactive steroids in major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(7):910–3. 10.1176/ajp.155.7.910 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 110. Griffin LD, Mellon SH: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors directly alter activity of neurosteroidogenic enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(23):13512–7. 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13512 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 111. Fry JP, Li KY, Devall AJ, et al. : Fluoxetine elevates allopregnanolone in female rat brain but inhibits a steroid microsomal dehydrogenase rather than activating an aldo-keto reductase. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171(24):5870–80. 10.1111/bph.12891 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 112. Field T: Postpartum depression effects on early interactions, parenting, and safety practices: a review. Infant Behav Dev. 2010;33(1):1–6. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.10.005 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 113. Kim DR, Epperson CN, Weiss AR, et al. : Pharmacotherapy of postpartum depression: an update. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15(9):1223–34. 10.1517/14656566.2014.911842 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 114. Deligiannidis KM, Sikoglu EM, Shaffer SA, et al. : GABAergic neuroactive steroids and resting-state functional connectivity in postpartum depression: a preliminary study. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(6):816–28. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.02.010 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 115. Melón L, Hammond R, Lewis M, et al. : A Novel, Synthetic, Neuroactive Steroid Is Effective at Decreasing Depression-Like Behaviors and Improving Maternal Care in Preclinical Models of Postpartum Depression. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:703. 10.3389/fendo.2018.00703 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 116. Schiller CE, Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR: Allopregnanolone as a mediator of affective switching in reproductive mood disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(17):3557–67. 10.1007/s00213-014-3599-x [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 117. Schiller CE, Meltzer-Brody S, Rubinow DR: The role of reproductive hormones in postpartum depression. CNS Spectr. 2015;20(1):48–59. 10.1017/S1092852914000480 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 118. Moses-Kolko EL, Perlman SB, Wisner KL, et al. : Abnormally reduced dorsomedial prefrontal cortical activity and effective connectivity with amygdala in response to negative emotional faces in postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(11):1373–80. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09081235 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 119. Bloch M, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau M, et al. : Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):924–30. 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.924 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 120. MacKenzie G, Maguire J: The role of ovarian hormone-derived neurosteroids on the regulation of GABA A receptors in affective disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(17):3333–42. 10.1007/s00213-013-3423-z [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 121. Maguire J, Mody I: GABA A R plasticity during pregnancy: relevance to postpartum depression. Neuron. 2008;59(2):207–13. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.019 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 122. Biggio G, Cristina Mostallino M, Follesa P, et al. : GABA A receptor function and gene expression during pregnancy and postpartum. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2009;85:73–94. 10.1016/S0074-7742(09)85006-X [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 123. Concas A, Mostallino MC, Porcu P, et al. : Role of brain allopregnanolone in the plasticity of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor in rat brain during pregnancy and after delivery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(22):13284–9. 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13284 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 124. Brunton PJ, Russell JA: Allopregnanolone and suppressed hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis stress responses in late pregnancy in the rat. Stress. 2011;14(1):6–12. 10.3109/10253890.2010.482628 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 125. Kanes S, Colquhoun H, Gunduz-Bruce H, et al. : Brexanolone (SAGE-547 injection) in post-partum depression: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10093):480–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31264-3 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 126. Meltzer-Brody S, Colquhoun H, Riesenberg R, et al. : Brexanolone injection in post-partum depression: two multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1058–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31551-4 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 127. Sage Therapeutics: Brexanolone Injection, for Intravenous Use: Sponsor Briefing Document. Joint Meeting of the Psychopharmacologic Drug Advisory Committee and Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee; November 2,2018. Reference Source [ Google Scholar ]

- 128. Luisi S, Petraglia F, Benedetto C, et al. : Serum allopregnanolone levels in pregnant women: changes during pregnancy, at delivery, and in hypertensive patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(7):2429–33. 10.1210/jcem.85.7.6675 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 129. U.S. Food and Drug Administration: FDA approves first treatment for post-partum depression. March 19,2019. Reference Source [ Google Scholar ]

- 130. Harris B, Lovett L, Smith J, et al. : Cardiff puerperal mood and hormone study. III. Postnatal depression at 5 to 6 weeks postpartum, and its hormonal correlates across the peripartum period. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168(6):739–44. 10.1192/bjp.168.6.739 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 131. Martinez Botella G, Salituro FG, Harrison BL, et al. : Neuroactive Steroids. 2. 3α-Hydroxy-3β-methyl-21-(4-cyano-1 H -pyrazol-1'-yl)-19-nor-5β-pregnan-20-one (SAGE-217): A Clinical Next Generation Neuroactive Steroid Positive Allosteric Modulator of the (γ-Aminobutyric Acid) A Receptor. J Med Chem. 2017;60(18):7810–9. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00846 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 132. Wang JM, Johnston PB, Ball BG, et al. : The neurosteroid allopregnanolone promotes proliferation of rodent and human neural progenitor cells and regulates cell-cycle gene and protein expression. J Neurosci. 2005;25(19):4706–18. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4520-04.2005 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 133. Russo SJ, Murrough JW, Han MH, et al. : Neurobiology of resilience. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(11):1475–84. 10.1038/nn.3234 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 134. Krishnan V, Han MH, Graham DL, et al. : Molecular adaptations underlying susceptibility and resistance to social defeat in brain reward regions. Cell. 2007;131(2):391–404. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.018 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 135. Han MH, Nestler EJ: Neural Substrates of Depression and Resilience. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(3):677–86. 10.1007/s13311-017-0527-x [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 136. Friedman AK, Walsh JJ, Juarez B, et al. : Enhancing depression mechanisms in midbrain dopamine neurons achieves homeostatic resilience. Science. 2014;344(6181):313–9. 10.1126/science.1249240 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 137. Cao JL, Covington HE, 3rd, Friedman AK, et al. : Mesolimbic dopamine neurons in the brain reward circuit mediate susceptibility to social defeat and antidepressant action. J Neurosci. 2010;30(49):16453–8. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3177-10.2010 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 138. Vialou V, Robison AJ, Laplant QC, et al. : DeltaFosB in brain reward circuits mediates resilience to stress and antidepressant responses. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(6):745–52. 10.1038/nn.2551 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 139. Zhu Z, Wang G, Ma K, et al. : GABAergic neurons in nucleus accumbens are correlated to resilience and vulnerability to chronic stress for major depression. Oncotarget. 2017;8(22):35933–45. 10.18632/oncotarget.16411 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 140. Qu Y, Yang C, Ren Q, et al. : Regional differences in dendritic spine density confer resilience to chronic social defeat stress. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2018;30(2):117–22. 10.1017/neu.2017.16 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 141. Anacker C, O'Donnell KJ, Meaney MJ: Early life adversity and the epigenetic programming of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2014;16(3):321–33. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 142. Weaver IC, Champagne FA, Brown SE, et al. : Reversal of maternal programming of stress responses in adult offspring through methyl supplementation: altering epigenetic marking later in life. J Neurosci. 2005;25(47):11045–54. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3652-05.2005 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 143. Anacker C, Luna VM, Stevens GS, et al. : Hippocampal neurogenesis confers stress resilience by inhibiting the ventral dentate gyrus. Nature. 2018;559(7712):98–102. 10.1038/s41586-018-0262-4 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 144. Drew LJ, Kheirbek MA, Luna VM, et al. : Activation of local inhibitory circuits in the dentate gyrus by adult-born neurons. Hippocampus. 2016;26(6):763–78. 10.1002/hipo.22557 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 145. Laverty D, Thomas P, Field M, et al. : Crystal structures of a GABA A -receptor chimera reveal new endogenous neurosteroid-binding sites. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017;24(11):977–85. 10.1038/nsmb.3477 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 146. Chen Q, Wells MM, Arjunan P, et al. : Structural basis of neurosteroid anesthetic action on GABA A receptors. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):3972. 10.1038/s41467-018-06361-4 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 147. Miller PS, Scott S, Masiulis S, et al. : Structural basis for GABA A receptor potentiation by neurosteroids. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017;24(11):986–92. 10.1038/nsmb.3484 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]; F1000 Recommendation

- 148. Masiulis S, Desai R, Uchański T, et al. : GABA A receptor signalling mechanisms revealed by structural pharmacology. Nature. 2019;565(7740):454–9. 10.1038/s41586-018-0832-5 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (1.9 MB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

VIDEO