- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Scientific Discovery

Scientific discovery is the process or product of successful scientific inquiry. Objects of discovery can be things, events, processes, causes, and properties as well as theories and hypotheses and their features (their explanatory power, for example). Most philosophical discussions of scientific discoveries focus on the generation of new hypotheses that fit or explain given data sets or allow for the derivation of testable consequences. Philosophical discussions of scientific discovery have been intricate and complex because the term “discovery” has been used in many different ways, both to refer to the outcome and to the procedure of inquiry. In the narrowest sense, the term “discovery” refers to the purported “eureka moment” of having a new insight. In the broadest sense, “discovery” is a synonym for “successful scientific endeavor” tout court. Some philosophical disputes about the nature of scientific discovery reflect these terminological variations.

Philosophical issues related to scientific discovery arise about the nature of human creativity, specifically about whether the “eureka moment” can be analyzed and about whether there are rules (algorithms, guidelines, or heuristics) according to which such a novel insight can be brought about. Philosophical issues also arise about the analysis and evaluation of heuristics, about the characteristics of hypotheses worthy of articulation and testing, and, on the meta-level, about the nature and scope of philosophical analysis itself. This essay describes the emergence and development of the philosophical problem of scientific discovery and surveys different philosophical approaches to understanding scientific discovery. In doing so, it also illuminates the meta-philosophical problems surrounding the debates, and, incidentally, the changing nature of philosophy of science.

1. Introduction

2. scientific inquiry as discovery, 3. elements of discovery, 4. pragmatic logics of discovery, 5. the distinction between the context of discovery and the context of justification, 6.1 discovery as abduction, 6.2 heuristic programming, 7. anomalies and the structure of discovery, 8.1 discoverability, 8.2 preliminary appraisal, 8.3 heuristic strategies, 9.1 kinds and features of creativity, 9.2 analogy, 9.3 mental models, 10. machine discovery, 11. social epistemology and discovery, 12. integrated approaches to knowledge generation, other internet resources, related entries.

Philosophical reflection on scientific discovery occurred in different phases. Prior to the 1930s, philosophers were mostly concerned with discoveries in the broad sense of the term, that is, with the analysis of successful scientific inquiry as a whole. Philosophical discussions focused on the question of whether there were any discernible patterns in the production of new knowledge. Because the concept of discovery did not have a specified meaning and was used in a very wide sense, almost all discussions of scientific method and practice could potentially be considered as early contributions to reflections on scientific discovery. In the course of the 18 th century, as philosophy of science and science gradually became two distinct endeavors with different audiences, the term “discovery” became a technical term in philosophical discussions. Different elements of scientific inquiry were specified. Most importantly, during the 19 th century, the generation of new knowledge came to be clearly and explicitly distinguished from its assessment, and thus the conditions for the narrower notion of discovery as the act or process of conceiving new ideas emerged. This distinction was encapsulated in the so-called “context distinction,” between the “context of discovery” and the “context of justification”.

Much of the discussion about scientific discovery in the 20 th century revolved around this distinction It was argued that conceiving a new idea is a non-rational process, a leap of insight that cannot be captured in specific instructions. Justification, by contrast, is a systematic process of applying evaluative criteria to knowledge claims. Advocates of the context distinction argued that philosophy of science is exclusively concerned with the context of justification. The assumption underlying this argument is that philosophy is a normative project; it determines norms for scientific practice. Given this assumption, only the justification of ideas, not their generation, can be the subject of philosophical (normative) analysis. Discovery, by contrast, can only be a topic for empirical study. By definition, the study of discovery is outside the scope of philosophy of science proper.

The introduction of the context distinction and the disciplinary distinction between empirical science studies and normative philosophy of science that was tied to it spawned meta-philosophical disputes. For a long time, philosophical debates about discovery were shaped by the notion that philosophical and empirical analyses are mutually exclusive. Some philosophers insisted, like their predecessors prior to the 1930s, that the philosopher’s tasks include the analysis of actual scientific practices and that scientific resources be used to address philosophical problems. They maintained that it is a legitimate task for philosophy of science to develop a theory of heuristics or problem solving. But this position was the minority view in philosophy of science until the last decades of the 20 th century. Philosophers of discovery were thus compelled to demonstrate that scientific discovery was in fact a legitimate part of philosophy of science. Philosophical reflections about the nature of scientific discovery had to be bolstered by meta-philosophical arguments about the nature and scope of philosophy of science.

Today, however, there is wide agreement that philosophy and empirical research are not mutually exclusive. Not only do empirical studies of actual scientific discoveries in past and present inform philosophical thought about the structure and cognitive mechanisms of discovery, but works in psychology, cognitive science, artificial intelligence and related fields have become integral parts of philosophical analyses of the processes and conditions of the generation of new knowledge. Social epistemology has opened up another perspective on scientific discovery, reconceptualizing knowledge generation as group process.

Prior to the 19 th century, the term “discovery” was used broadly to refer to a new finding, such as a new cure, an unknown territory, an improvement of an instrument, or a new method of measuring longitude. One strand of the discussion about discovery dating back to ancient times concerns the method of analysis as the method of discovery in mathematics and geometry, and, by extension, in philosophy and scientific inquiry. Following the analytic method, we seek to find or discover something – the “thing sought,” which could be a theorem, a solution to a geometrical problem, or a cause – by analyzing it. In the ancient Greek context, analytic methods in mathematics, geometry, and philosophy were not clearly separated; the notion of finding or discovering things by analysis was relevant in all these fields.

In the ensuing centuries, several natural and experimental philosophers, including Avicenna and Zabarella, Bacon and Boyle, the authors of the Port-Royal Logic and Newton, and many others, expounded rules of reasoning and methods for arriving at new knowledge. The ancient notion of analysis still informed these rules and methods. Newton’s famous thirty-first query in the second edition of the Opticks outlines the role of analysis in discovery as follows: “As in Mathematicks, so in Natural Philosophy, the Investigation of difficult Things by the Method of Analysis, ought ever to precede the Method of Composition. This Analysis consists in making Experiments and Observations, and in drawing general Conclusions from them by Induction, and admitting of no Objections against the Conclusions, but such as are taken from Experiments, or other certain Truths … By this way of Analysis we may proceed from Compounds to Ingredients, and from Motions to the Forces producing them; and in general, from Effects to their Causes, and from particular Causes to more general ones, till the Argument end in the most general. This is the Method of Analysis” (Newton 1718, 380, see Koertge 1980, section VI). Early modern accounts of discovery captured knowledge-seeking practices in the study of living and non-living nature, ranging from astronomy and physics to medicine, chemistry, and agriculture. These rich accounts of scientific inquiry were often expounded to bolster particular theories about the nature of matter and natural forces and were not explicitly labeled “methods of discovery ”, yet they are, in fact, accounts of knowledge generation and proper scientific reasoning, covering topics such as the role of the senses in knowledge generation, observation and experimentation, analysis and synthesis, induction and deduction, hypotheses, probability, and certainty.

Bacon’s work is a prominent example. His view of the method of science as it is presented in the Novum Organum showed how best to arrive at knowledge about “form natures” (the most general properties of matter) via a systematic investigation of phenomenal natures. Bacon described how first to collect and organize natural phenomena and experimentally produced facts in tables, how to evaluate these lists, and how to refine the initial results with the help of further trials. Through these steps, the investigator would arrive at conclusions about the “form nature” that produces particular phenomenal natures. Bacon expounded the procedures of constructing and evaluating tables of presences and absences to underpin his matter theory. In addition, in his other writings, such as his natural history Sylva Sylvarum or his comprehensive work on human learning De Augmentis Scientiarium , Bacon exemplified the “art of discovery” with practical examples and discussions of strategies of inquiry.

Like Bacon and Newton, several other early modern authors advanced ideas about how to generate and secure empirical knowledge, what difficulties may arise in scientific inquiry, and how they could be overcome. The close connection between theories about matter and force and scientific methodologies that we find in early modern works was gradually severed. 18 th - and early 19 th -century authors on scientific method and logic cited early modern approaches mostly to model proper scientific practice and reasoning, often creatively modifying them ( section 3 ). Moreover, they developed the earlier methodologies of experimentation, observation, and reasoning into practical guidelines for discovering new phenomena and devising probable hypotheses about cause-effect relations.

It was common in 20 th -century philosophy of science to draw a sharp contrast between those early theories of scientific method and modern approaches. 20 th -century philosophers of science interpreted 17 th - and 18 th -century approaches as generative theories of scientific method. They function simultaneously as guides for acquiring new knowledge and as assessments of the knowledge thus obtained, whereby knowledge that is obtained “in the right way” is considered secure (Laudan 1980; Schaffner 1993: chapter 2). On this view, scientific methods are taken to have probative force (Nickles 1985). According to modern, “consequentialist” theories, propositions must be established by comparing their consequences with observed and experimentally produced phenomena (Laudan 1980; Nickles 1985). It was further argued that, when consequentialist theories were on the rise, the two processes of generation and assessment of an idea or hypothesis became distinct, and the view that the merit of a new idea does not depend on the way in which it was arrived at became widely accepted.

More recent research in history of philosophy of science has shown, however, that there was no such sharp contrast. Consequentialist ideas were advanced throughout the 18 th century, and the early modern generative theories of scientific method and knowledge were more pragmatic than previously assumed. Early modern scholars did not assume that this procedure would lead to absolute certainty. One could only obtain moral certainty for the propositions thus secured.

During the 18 th and 19 th centuries, the different elements of discovery gradually became separated and discussed in more detail. Discussions concerned the nature of observations and experiments, the act of having an insight and the processes of articulating, developing, and testing the novel insight. Philosophical discussion focused on the question of whether and to what extent rules could be devised to guide each of these processes.

Numerous 19 th -century scholars contributed to these discussions, including Claude Bernard, Auguste Comte, George Gore, John Herschel, W. Stanley Jevons, Justus von Liebig, John Stuart Mill, and Charles Sanders Peirce, to name only a few. William Whewell’s work, especially the two volumes of Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences of 1840, is a noteworthy and, later, much discussed contribution to the philosophical debates about scientific discovery because he explicitly distinguished the creative moment or “happy thought” as he called it from other elements of scientific inquiry and because he offered a detailed analysis of the “discoverer’s induction”, i.e., the pursuit and evaluation of the new insight. Whewell’s approach is not unique, but for late 20 th -century philosophers of science, his comprehensive, historically informed philosophy of discovery became a point of orientation in the revival of interest in scientific discovery processes.

For Whewell, discovery comprised three elements: the happy thought, the articulation and development of that thought, and the testing or verification of it. His account was in part a description of the psychological makeup of the discoverer. For instance, he held that only geniuses could have those happy thoughts that are essential to discovery. In part, his account was an account of the methods by which happy thoughts are integrated into the system of knowledge. According to Whewell, the initial step in every discovery is what he called “some happy thought, of which we cannot trace the origin; some fortunate cast of intellect, rising above all rules. No maxims can be given which inevitably lead to discovery” (Whewell 1996 [1840]: 186). An “art of discovery” in the sense of a teachable and learnable skill does not exist according to Whewell. The happy thought builds on the known facts, but according to Whewell it is impossible to prescribe a method for having happy thoughts.

In this sense, happy thoughts are accidental. But in an important sense, scientific discoveries are not accidental. The happy thought is not a wild guess. Only the person whose mind is prepared to see things will actually notice them. The “previous condition of the intellect, and not the single fact, is really the main and peculiar cause of the success. The fact is merely the occasion by which the engine of discovery is brought into play sooner or later. It is, as I have elsewhere said, only the spark which discharges a gun already loaded and pointed; and there is little propriety in speaking of such an accident as the cause why the bullet hits its mark.” (Whewell 1996 [1840]: 189).

Having a happy thought is not yet a discovery, however. The second element of a scientific discovery consists in binding together—“colligating”, as Whewell called it—a set of facts by bringing them under a general conception. Not only does the colligation produce something new, but it also shows the previously known facts in a new light. Colligation involves, on the one hand, the specification of facts through systematic observation, measurements and experiment, and on the other hand, the clarification of ideas through the exposition of the definitions and axioms that are tacitly implied in those ideas. This process is extended and iterative. The scientists go back and forth between binding together the facts, clarifying the idea, rendering the facts more exact, and so forth.

The final part of the discovery is the verification of the colligation involving the happy thought. This means, first and foremost, that the outcome of the colligation must be sufficient to explain the data at hand. Verification also involves judging the predictive power, simplicity, and “consilience” of the outcome of the colligation. “Consilience” refers to a higher range of generality (broader applicability) of the theory (the articulated and clarified happy thought) that the actual colligation produced. Whewell’s account of discovery is not a deductivist system. It is essential that the outcome of the colligation be inferable from the data prior to any testing (Snyder 1997).

Whewell’s theory of discovery clearly separates three elements: the non-analyzable happy thought or eureka moment; the process of colligation which includes the clarification and explication of facts and ideas; and the verification of the outcome of the colligation. His position that the philosophy of discovery cannot prescribe how to think happy thoughts has been a key element of 20 th -century philosophical reflection on discovery. In contrast to many 20 th -century approaches, Whewell’s philosophical conception of discovery also comprises the processes by which the happy thoughts are articulated. Similarly, the process of verification is an integral part of discovery. The procedures of articulation and test are both analyzable according to Whewell, and his conception of colligation and verification serve as guidelines for how the discoverer should proceed. To verify a hypothesis, the investigator needs to show that it accounts for the known facts, that it foretells new, previously unobserved phenomena, and that it can explain and predict phenomena which are explained and predicted by a hypothesis that was obtained through an independent happy thought-cum-colligation (Ducasse 1951).

Whewell’s conceptualization of scientific discovery offers a useful framework for mapping the philosophical debates about discovery and for identifying major issues of concern in 20 th -century philosophical debates. Until the late 20 th century, most philosophers operated with a notion of discovery that is narrower than Whewell’s. In more recent treatments of discovery, however, the scope of the term “discovery” is limited to either the first of these elements, the “happy thought”, or to the happy thought and its initial articulation. In the narrower conception, what Whewell called “verification” is not part of discovery proper. Secondly, until the late 20 th century, there was wide agreement that the eureka moment, narrowly construed, is an unanalyzable, even mysterious leap of insight. The main disagreements concerned the question of whether the process of developing a hypothesis (the “colligation” in Whewell’s terms) is, or is not, a part of discovery proper – and if it is, whether and how this process is guided by rules. Much of the controversies in the 20 th century about the possibility of a philosophy of discovery can be understood against the background of the disagreement about whether the process of discovery does or does not include the articulation and development of a novel thought. Philosophers also disagreed on the issue of whether it is a philosophical task to explicate these rules.

In early 20 th -century logical empiricism, the view that discovery is or at least crucially involves a non-analyzable creative act of a gifted genius was widespread. Alternative conceptions of discovery especially in the pragmatist tradition emphasize that discovery is an extended process, i.e., that the discovery process includes the reasoning processes through which a new insight is articulated and further developed.

In the pragmatist tradition, the term “logic” is used in the broad sense to refer to strategies of human reasoning and inquiry. While the reasoning involved does not proceed according to the principles of demonstrative logic, it is systematic enough to deserve the label “logical”. Proponents of this view argued that traditional (here: syllogistic) logic is an inadequate model of scientific discovery because it misrepresents the process of knowledge generation as grossly as the notion of an “aha moment”.

Early 20 th -century pragmatic logics of discovery can best be described as comprehensive theories of the mental and physical-practical operations involved in knowledge generation, as theories of “how we think” (Dewey 1910). Among the mental operations are classification, determination of what is relevant to an inquiry, and the conditions of communication of meaning; among the physical operations are observation and (laboratory) experiments. These features of scientific discovery are either not or only insufficiently represented by traditional syllogistic logic (Schiller 1917: 236–7).

Philosophers advocating this approach agree that the logic of discovery should be characterized as a set of heuristic principles rather than as a process of applying inductive or deductive logic to a set of propositions. These heuristic principles are not understood to show the path to secure knowledge. Heuristic principles are suggestive rather than demonstrative (Carmichael 1922, 1930). One recurrent feature in these accounts of the reasoning strategies leading to new ideas is analogical reasoning (Schiller 1917; Benjamin 1934, see also section 9.2 .). However, in academic philosophy of science, endeavors to develop more systematically the heuristics guiding discovery processes were soon eclipsed by the advance of the distinction between contexts of discovery and justification.

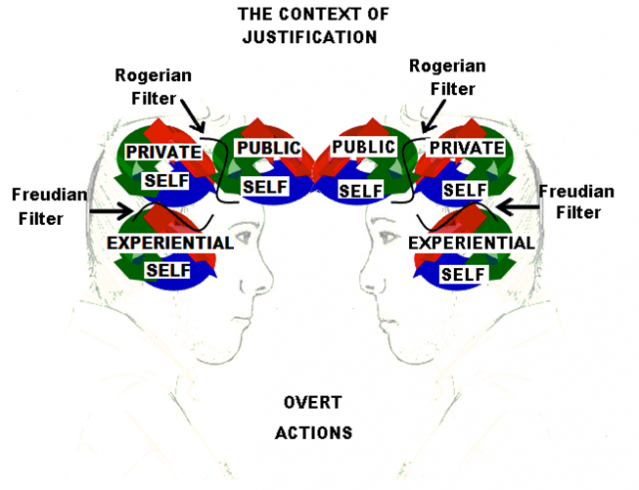

The distinction between “context of discovery” and “context of justification” dominated and shaped the discussions about discovery in 20 th -century philosophy of science. The context distinction marks the distinction between the generation of a new idea or hypothesis and the defense (test, verification) of it. As the previous sections have shown, the distinction among different elements of scientific inquiry has a long history but in the first half of the 20 th century, the distinction between the different features of scientific inquiry turned into a powerful demarcation criterion between “genuine” philosophy and other fields of science studies, which became potent in philosophy of science. The boundary between context of discovery (the de facto thinking processes) and context of justification (the de jure defense of the correctness of these thoughts) was now understood to determine the scope of philosophy of science, whereby philosophy of science is conceived as a normative endeavor. Advocates of the context distinction argue that the generation of a new idea is an intuitive, nonrational process; it cannot be subject to normative analysis. Therefore, the study of scientists’ actual thinking can only be the subject of psychology, sociology, and other empirical sciences. Philosophy of science, by contrast, is exclusively concerned with the context of justification.

The terms “context of discovery” and “context of justification” are often associated with Hans Reichenbach’s work. Reichenbach’s original conception of the context distinction is quite complex, however (Howard 2006; Richardson 2006). It does not map easily on to the disciplinary distinction mentioned above, because for Reichenbach, philosophy of science proper is partly descriptive. Reichenbach maintains that philosophy of science includes a description of knowledge as it really is. Descriptive philosophy of science reconstructs scientists’ thinking processes in such a way that logical analysis can be performed on them, and it thus prepares the ground for the evaluation of these thoughts (Reichenbach 1938: § 1). Discovery, by contrast, is the object of empirical—psychological, sociological—study. According to Reichenbach, the empirical study of discoveries shows that processes of discovery often correspond to the principle of induction, but this is simply a psychological fact (Reichenbach 1938: 403).

While the terms “context of discovery” and “context of justification” are widely used, there has been ample discussion about how the distinction should be drawn and what their philosophical significance is (c.f. Kordig 1978; Gutting 1980; Zahar 1983; Leplin 1987; Hoyningen-Huene 1987; Weber 2005: chapter 3; Schickore and Steinle 2006). Most commonly, the distinction is interpreted as a distinction between the process of conceiving a theory and the assessment of that theory, specifically the assessment of the theory’s epistemic support. This version of the distinction is not necessarily interpreted as a temporal distinction. In other words, it is not usually assumed that a theory is first fully developed and then assessed. Rather, generation and assessment are two different epistemic approaches to theory: the endeavor to articulate, flesh out, and develop its potential and the endeavor to assess its epistemic worth. Within the framework of the context distinction, there are two main ways of conceptualizing the process of conceiving a theory. The first option is to characterize the generation of new knowledge as an irrational act, a mysterious creative intuition, a “eureka moment”. The second option is to conceptualize the generation of new knowledge as an extended process that includes a creative act as well as some process of articulating and developing the creative idea.

Both of these accounts of knowledge generation served as starting points for arguments against the possibility of a philosophy of discovery. In line with the first option, philosophers have argued that neither is it possible to prescribe a logical method that produces new ideas nor is it possible to reconstruct logically the process of discovery. Only the process of testing is amenable to logical investigation. This objection to philosophies of discovery has been called the “discovery machine objection” (Curd 1980: 207). It is usually associated with Karl Popper’s Logic of Scientific Discovery .

The initial state, the act of conceiving or inventing a theory, seems to me neither to call for logical analysis not to be susceptible of it. The question how it happens that a new idea occurs to a man—whether it is a musical theme, a dramatic conflict, or a scientific theory—may be of great interest to empirical psychology; but it is irrelevant to the logical analysis of scientific knowledge. This latter is concerned not with questions of fact (Kant’s quid facti ?) , but only with questions of justification or validity (Kant’s quid juris ?) . Its questions are of the following kind. Can a statement be justified? And if so, how? Is it testable? Is it logically dependent on certain other statements? Or does it perhaps contradict them? […]Accordingly I shall distinguish sharply between the process of conceiving a new idea, and the methods and results of examining it logically. As to the task of the logic of knowledge—in contradistinction to the psychology of knowledge—I shall proceed on the assumption that it consists solely in investigating the methods employed in those systematic tests to which every new idea must be subjected if it is to be seriously entertained. (Popper 2002 [1934/1959]: 7–8)

With respect to the second way of conceptualizing knowledge generation, many philosophers argue in a similar fashion that because the process of discovery involves an irrational, intuitive process, which cannot be examined logically, a logic of discovery cannot be construed. Other philosophers turn against the philosophy of discovery even though they explicitly acknowledge that discovery is an extended, reasoned process. They present a meta-philosophical objection argument, arguing that a theory of articulating and developing ideas is not a philosophical but a psychological or sociological theory. In this perspective, “discovery” is understood as a retrospective label, which is attributed as a sign of accomplishment to some scientific endeavors. Sociological theories acknowledge that discovery is a collective achievement and the outcome of a process of negotiation through which “discovery stories” are constructed and certain knowledge claims are granted discovery status (Brannigan 1981; Schaffer 1986, 1994).

The impact of the context distinction on 20 th -century studies of scientific discovery and on philosophy of science more generally can hardly be overestimated. The view that the process of discovery (however construed) is outside the scope of philosophy of science proper was widely shared amongst philosophers of science for most of the 20 th century. The last section shows that there were some attempts to develop logics of discovery in the 1920s and 1930s, especially in the pragmatist tradition. But for several decades, the context distinction dictated what philosophy of science should be about and how it should proceed. The dominant view was that theories of mental operations or heuristics had no place in philosophy of science and that, therefore, discovery was not a legitimate topic for philosophy of science. Until the last decades of the 20 th century, there were few attempts to challenge the disciplinary distinction tied to the context distinction. Only during the 1970s did the interest in philosophical approaches to discovery begin to increase again. But the context distinction remained a challenge for philosophies of discovery.

There are several lines of response to the disciplinary distinction tied to the context distinction. Each of these lines of response opens a philosophical perspective on discovery. Each proceeds on the assumption that philosophy of science may legitimately include some form of analysis of actual reasoning patterns as well as information from empirical sciences such as cognitive science, psychology, and sociology. All of these responses reject the idea that discovery is nothing but a mystical event. Discovery is conceived as an analyzable reasoning process, not just as a creative leap by which novel ideas spring into being fully formed. All of these responses agree that the procedures and methods for arriving at new hypotheses and ideas are no guarantee that the hypothesis or idea that is thus formed is necessarily the best or the correct one. Nonetheless, it is the task of philosophy of science to provide rules for making this process better. All of these responses can be described as theories of problem solving, whose ultimate goal is to make the generation of new ideas and theories more efficient.

But the different approaches to scientific discovery employ different terminologies. In particular, the term “logic” of discovery is sometimes used in a narrow sense and sometimes broadly understood. In the narrow sense, “logic” of discovery is understood to refer to a set of formal, generally applicable rules by which novel ideas can be mechanically derived from existing data. In the broad sense, “logic” of discovery refers to the schematic representation of reasoning procedures. “Logical” is just another term for “rational”. Moreover, while each of these responses combines philosophical analyses of scientific discovery with empirical research on actual human cognition, different sets of resources are mobilized, ranging from AI research and cognitive science to historical studies of problem-solving procedures. Also, the responses parse the process of scientific inquiry differently. Often, scientific inquiry is regarded as having two aspects, viz. generation and assessments of new ideas. At times, however, scientific inquiry is regarded as having three aspects, namely generation, pursuit or articulation, and assessment of knowledge. In the latter framework, the label “discovery” is sometimes used to refer just to generation and sometimes to refer to both generation and pursuit.

One response to the challenge of the context distinction draws on a broad understanding of the term “logic” to argue that we cannot but admit a general, domain-neutral logic if we do not want to assume that the success of science is a miracle (Jantzen 2016) and that a logic of scientific discovery can be developed ( section 6 ). Another response, drawing on a narrow understanding of the term “logic”, is to concede that there is no logic of discovery, i.e., no algorithm for generating new knowledge, but that the process of discovery follows an identifiable, analyzable pattern ( section 7 ).

Others argue that discovery is governed by a methodology . The methodology of discovery is a legitimate topic for philosophical analysis ( section 8 ). Yet another response assumes that discovery is or at least involves a creative act. Drawing on resources from cognitive science, neuroscience, computational research, and environmental and social psychology, philosophers have sought to demystify the cognitive processes involved in the generation of new ideas. Philosophers who take this approach argue that scientific creativity is amenable to philosophical analysis ( section 9.1 ).

All these responses assume that there is more to discovery than a eureka moment. Discovery comprises processes of articulating, developing, and assessing the creative thought, as well as the scientific community’s adjudication of what does, and does not, count as “discovery” (Arabatzis 1996). These are the processes that can be examined with the tools of philosophical analysis, augmented by input from other fields of science studies such as sociology, history, or cognitive science.

6. Logics of discovery after the context distinction

One way of responding to the demarcation criterion described above is to argue that discovery is a topic for philosophy of science because it is a logical process after all. Advocates of this approach to the logic of discovery usually accept the overall distinction between the two processes of conceiving and testing a hypothesis. They also agree that it is impossible to put together a manual that provides a formal, mechanical procedure through which innovative concepts or hypotheses can be derived: There is no discovery machine. But they reject the view that the process of conceiving a theory is a creative act, a mysterious guess, a hunch, a more or less instantaneous and random process. Instead, they insist that both conceiving and testing hypotheses are processes of reasoning and systematic inference, that both of these processes can be represented schematically, and that it is possible to distinguish better and worse paths to new knowledge.

This line of argument has much in common with the logics of discovery described in section 4 above but it is now explicitly pitched against the disciplinary distinction tied to the context distinction. There are two main ways of developing this argument. The first is to conceive of discovery in terms of abductive reasoning ( section 6.1 ). The second is to conceive of discovery in terms of problem-solving algorithms, whereby heuristic rules aid the processing of available data and enhance the success in finding solutions to problems ( section 6.2 ). Both lines of argument rely on a broad conception of logic, whereby the “logic” of discovery amounts to a schematic account of the reasoning processes involved in knowledge generation.

One argument, elaborated prominently by Norwood R. Hanson, is that the act of discovery—here, the act of suggesting a new hypothesis—follows a distinctive logical pattern, which is different from both inductive logic and the logic of hypothetico-deductive reasoning. The special logic of discovery is the logic of abductive or “retroductive” inferences (Hanson 1958). The argument that it is through an act of abductive inferences that plausible, promising scientific hypotheses are devised goes back to C.S. Peirce. This version of the logic of discovery characterizes reasoning processes that take place before a new hypothesis is ultimately justified. The abductive mode of reasoning that leads to plausible hypotheses is conceptualized as an inference beginning with data or, more specifically, with surprising or anomalous phenomena.

In this view, discovery is primarily a process of explaining anomalies or surprising, astonishing phenomena. The scientists’ reasoning proceeds abductively from an anomaly to an explanatory hypothesis in light of which the phenomena would no longer be surprising or anomalous. The outcome of this reasoning process is not one single specific hypothesis but the delineation of a type of hypotheses that is worthy of further attention (Hanson 1965: 64). According to Hanson, the abductive argument has the following schematic form (Hanson 1960: 104):

- Some surprising, astonishing phenomena p 1 , p 2 , p 3 … are encountered.

- But p 1 , p 2 , p 3 … would not be surprising were an hypothesis of H ’s type to obtain. They would follow as a matter of course from something like H and would be explained by it.

- Therefore there is good reason for elaborating an hypothesis of type H—for proposing it as a possible hypothesis from whose assumption p 1 , p 2 , p 3 … might be explained.

Drawing on the historical record, Hanson argues that several important discoveries were made relying on abductive reasoning, such as Kepler’s discovery of the elliptic orbit of Mars (Hanson 1958). It is now widely agreed, however, that Hanson’s reconstruction of the episode is not a historically adequate account of Kepler’s discovery (Lugg 1985). More importantly, while there is general agreement that abductive inferences are frequent in both everyday and scientific reasoning, these inferences are no longer considered as logical inferences. Even if one accepts Hanson’s schematic representation of the process of identifying plausible hypotheses, this process is a “logical” process only in the widest sense whereby the term “logical” is understood as synonymous with “rational”. Notably, some philosophers have even questioned the rationality of abductive inferences (Koehler 1991; Brem and Rips 2000).

Another argument against the above schema is that it is too permissive. There will be several hypotheses that are explanations for phenomena p 1 , p 2 , p 3 …, so the fact that a particular hypothesis explains the phenomena is not a decisive criterion for developing that hypothesis (Harman 1965; see also Blackwell 1969). Additional criteria are required to evaluate the hypothesis yielded by abductive inferences.

Finally, it is worth noting that the schema of abductive reasoning does not explain the very act of conceiving a hypothesis or hypothesis-type. The processes by which a new idea is first articulated remain unanalyzed in the above schema. The schema focuses on the reasoning processes by which an exploratory hypothesis is assessed in terms of its merits and promise (Laudan 1980; Schaffner 1993).

In more recent work on abduction and discovery, two notions of abduction are sometimes distinguished: the common notion of abduction as inference to the best explanation (selective abduction) and creative abduction (Magnani 2000, 2009). Selective abduction—the inference to the best explanation—involves selecting a hypothesis from a set of known hypotheses. Medical diagnosis exemplifies this kind of abduction. Creative abduction, by contrast, involves generating a new, plausible hypothesis. This happens, for instance, in medical research, when the notion of a new disease is articulated. However, it is still an open question whether this distinction can be drawn, or whether there is a more gradual transition from selecting an explanatory hypothesis from a familiar domain (selective abduction) to selecting a hypothesis that is slightly modified from the familiar set and to identifying a more drastically modified or altered assumption.

Another recent suggestion is to broaden Peirce’s original account of abduction and to include not only verbal information but also non-verbal mental representations, such as visual, auditory, or motor representations. In Thagard’s approach, representations are characterized as patterns of activity in mental populations (see also section 9.3 below). The advantage of the neural account of human reasoning is that it covers features such as the surprise that accompanies the generation of new insights or the visual and auditory representations that contribute to it. Surprise, for instance, could be characterized as resulting from rapid changes in activation of the node in a neural network representing the “surprising” element (Thagard and Stewart 2011). If all mental representations can be characterized as patterns of firing in neural populations, abduction can be analyzed as the combination or “convolution” (Thagard) of patterns of neural activity from disjoint or overlapping patterns of activity (Thagard 2010).

The concern with the logic of discovery has also motivated research on artificial intelligence at the intersection of philosophy of science and cognitive science. In this approach, scientific discovery is treated as a form of problem-solving activity (Simon 1973; see also Newell and Simon 1971), whereby the systematic aspects of problem solving are studied within an information-processing framework. The aim is to clarify with the help of computational tools the nature of the methods used to discover scientific hypotheses. These hypotheses are regarded as solutions to problems. Philosophers working in this tradition build computer programs employing methods of heuristic selective search (e.g., Langley et al. 1987). In computational heuristics, search programs can be described as searches for solutions in a so-called “problem space” in a certain domain. The problem space comprises all possible configurations in that domain (e.g., for chess problems, all possible arrangements of pieces on a board of chess). Each configuration is a “state” of the problem space. There are two special states, namely the goal state, i.e., the state to be reached, and the initial state, i.e., the configuration at the starting point from which the search begins. There are operators, which determine the moves that generate new states from the current state. There are path constraints, which limit the permitted moves. Problem solving is the process of searching for a solution of the problem of how to generate the goal state from an initial state. In principle, all states can be generated by applying the operators to the initial state, then to the resulting state, until the goal state is reached (Langley et al. 1987: chapter 9). A problem solution is a sequence of operations leading from the initial to the goal state.

The basic idea behind computational heuristics is that rules can be identified that serve as guidelines for finding a solution to a given problem quickly and efficiently by avoiding undesired states of the problem space. These rules are best described as rules of thumb. The aim of constructing a logic of discovery thus becomes the aim of constructing a heuristics for the efficient search for solutions to problems. The term “heuristic search” indicates that in contrast to algorithms, problem-solving procedures lead to results that are merely provisional and plausible. A solution is not guaranteed, but heuristic searches are advantageous because they are more efficient than exhaustive random trial and error searches. Insofar as it is possible to evaluate whether one set of heuristics is better—more efficacious—than another, the logic of discovery turns into a normative theory of discovery.

Arguably, because it is possible to reconstruct important scientific discovery processes with sets of computational heuristics, the scientific discovery process can be considered as a special case of the general mechanism of information processing. In this context, the term “logic” is not used in the narrow sense of a set of formal, generally applicable rules to draw inferences but again in a broad sense as a label for a set of procedural rules.

The computer programs that embody the principles of heuristic searches in scientific inquiry simulate the paths that scientists followed when they searched for new theoretical hypotheses. Computer programs such as BACON (Simon et al. 1981) and KEKADA (Kulkarni and Simon 1988) utilize sets of problem-solving heuristics to detect regularities in given data sets. The program would note, for instance, that the values of a dependent term are constant or that a set of values for a term x and a set of values for a term y are linearly related. It would thus “infer” that the dependent term always has that value or that a linear relation exists between x and y . These programs can “make discoveries” in the sense that they can simulate successful discoveries such as Kepler’s third law (BACON) or the Krebs cycle (KEKADA).

Computational theories of scientific discoveries have helped identify and clarify a number of problem-solving strategies. An example of such a strategy is heuristic means-ends analysis, which involves identifying specific differences between the present and the goal situation and searches for operators (processes that will change the situation) that are associated with the differences that were detected. Another important heuristic is to divide the problem into sub-problems and to begin solving the one with the smallest number of unknowns to be determined (Simon 1977). Computational approaches have also highlighted the extent to which the generation of new knowledge draws on existing knowledge that constrains the development of new hypotheses.

As accounts of scientific discoveries, the early computational heuristics have some limitations. Compared to the problem spaces given in computational heuristics, the complex problem spaces for scientific problems are often ill defined, and the relevant search space and goal state must be delineated before heuristic assumptions could be formulated (Bechtel and Richardson 1993: chapter 1). Because a computer program requires the data from actual experiments, the simulations cover only certain aspects of scientific discoveries; in particular, it cannot determine by itself which data is relevant, which data to relate and what form of law it should look for (Gillies 1996). However, as a consequence of the rise of so-called “deep learning” methods in data-intensive science, there is renewed philosophical interest in the question of whether machines can make discoveries ( section 10 ).

Many philosophers maintain that discovery is a legitimate topic for philosophy of science while abandoning the notion that there is a logic of discovery. One very influential approach is Thomas Kuhn’s analysis of the emergence of novel facts and theories (Kuhn 1970 [1962]: chapter 6). Kuhn identifies a general pattern of discovery as part of his account of scientific change. A discovery is not a simple act, but an extended, complex process, which culminates in paradigm changes. Paradigms are the symbolic generalizations, metaphysical commitments, values, and exemplars that are shared by a community of scientists and that guide the research of that community. Paradigm-based, normal science does not aim at novelty but instead at the development, extension, and articulation of accepted paradigms. A discovery begins with an anomaly, that is, with the recognition that the expectations induced by an established paradigm are being violated. The process of discovery involves several aspects: observations of an anomalous phenomenon, attempts to conceptualize it, and changes in the paradigm so that the anomaly can be accommodated.

It is the mark of success of normal science that it does not make transformative discoveries, and yet such discoveries come about as a consequence of normal, paradigm-guided science. The more detailed and the better developed a paradigm, the more precise are its predictions. The more precisely the researchers know what to expect, the better they are able to recognize anomalous results and violations of expectations:

novelty ordinarily emerges only for the man who, knowing with precision what he should expect, is able to recognize that something has gone wrong. Anomaly appears only against the background provided by the paradigm. (Kuhn 1970 [1962]: 65)

Drawing on several historical examples, Kuhn argues that it is usually impossible to identify the very moment when something was discovered or even the individual who made the discovery. Kuhn illustrates these points with the discovery of oxygen (see Kuhn 1970 [1962]: 53–56). Oxygen had not been discovered before 1774 and had been discovered by 1777. Even before 1774, Lavoisier had noticed that something was wrong with phlogiston theory, but he was unable to move forward. Two other investigators, C. W. Scheele and Joseph Priestley, independently identified a gas obtained from heating solid substances. But Scheele’s work remained unpublished until after 1777, and Priestley did not identify his substance as a new sort of gas. In 1777, Lavoisier presented the oxygen theory of combustion, which gave rise to fundamental reconceptualization of chemistry. But according to this theory as Lavoisier first presented it, oxygen was not a chemical element. It was an atomic “principle of acidity” and oxygen gas was a combination of that principle with caloric. According to Kuhn, all of these developments are part of the discovery of oxygen, but none of them can be singled out as “the” act of discovery.

In pre-paradigmatic periods or in times of paradigm crisis, theory-induced discoveries may happen. In these periods, scientists speculate and develop tentative theories, which may lead to novel expectations and experiments and observations to test whether these expectations can be confirmed. Even though no precise predictions can be made, phenomena that are thus uncovered are often not quite what had been expected. In these situations, the simultaneous exploration of the new phenomena and articulation of the tentative hypotheses together bring about discovery.

In cases like the discovery of oxygen, by contrast, which took place while a paradigm was already in place, the unexpected becomes apparent only slowly, with difficulty, and against some resistance. Only gradually do the anomalies become visible as such. It takes time for the investigators to recognize “both that something is and what it is” (Kuhn 1970 [1962]: 55). Eventually, a new paradigm becomes established and the anomalous phenomena become the expected phenomena.

Recent studies in cognitive neuroscience of brain activity during periods of conceptual change support Kuhn’s view that conceptual change is hard to achieve. These studies examine the neural processes that are involved in the recognition of anomalies and compare them with the brain activity involved in the processing of information that is consistent with preferred theories. The studies suggest that the two types of data are processed differently (Dunbar et al. 2007).

8. Methodologies of discovery

Advocates of the view that there are methodologies of discovery use the term “logic” in the narrow sense of an algorithmic procedure to generate new ideas. But like the AI-based theories of scientific discovery described in section 6 , methodologies of scientific discovery interpret the concept “discovery” as a label for an extended process of generating and articulating new ideas and often describe the process in terms of problem solving. In these approaches, the distinction between the contexts of discovery and the context of justification is challenged because the methodology of discovery is understood to play a justificatory role. Advocates of a methodology of discovery usually rely on a distinction between different justification procedures, justification involved in the process of generating new knowledge and justification involved in testing it. Consequential or “strong” justifications are methods of testing. The justification involved in discovery, by contrast, is conceived as generative (as opposed to consequential) justification ( section 8.1 ) or as weak (as opposed to strong) justification ( section 8.2 ). Again, some terminological ambiguity exists because according to some philosophers, there are three contexts, not two: Only the initial conception of a new idea (the creative act is the context of discovery proper, and between it and justification there exists a separate context of pursuit (Laudan 1980). But many advocates of methodologies of discovery regard the context of pursuit as an integral part of the process of justification. They retain the notion of two contexts and re-draw the boundaries between the contexts of discovery and justification as they were drawn in the early 20 th century.

The methodology of discovery has sometimes been characterized as a form of justification that is complementary to the methodology of testing (Nickles 1984, 1985, 1989). According to the methodology of testing, empirical support for a theory results from successfully testing the predictive consequences derived from that theory (and appropriate auxiliary assumptions). In light of this methodology, justification for a theory is “consequential justification,” the notion that a hypothesis is established if successful novel predictions are derived from the theory or claim. Generative justification complements consequential justification. Advocates of generative justification hold that there exists an important form of justification in science that involves reasoning to a claim from data or previously established results more generally.

One classic example for a generative methodology is the set of Newton’s rules for the study of natural philosophy. According to these rules, general propositions are established by deducing them from the phenomena. The notion of generative justification seeks to preserve the intuition behind classic conceptions of justification by deduction. Generative justification amounts to the rational reconstruction of the discovery path in order to establish its discoverability had the researchers known what is known now, regardless of how it was first thought of (Nickles 1985, 1989). The reconstruction demonstrates in hindsight that the claim could have been discovered in this manner had the necessary information and techniques been available. In other words, generative justification—justification as “discoverability” or “potential discovery”—justifies a knowledge claim by deriving it from results that are already established. While generative justification does not retrace exactly those steps of the actual discovery path that were actually taken, it is a better representation of scientists’ actual practices than consequential justification because scientists tend to construe new claims from available knowledge. Generative justification is a weaker version of the traditional ideal of justification by deduction from the phenomena. Justification by deduction from the phenomena is complete if a theory or claim is completely determined from what we already know. The demonstration of discoverability results from the successful derivation of a claim or theory from the most basic and most solidly established empirical information.

Discoverability as described in the previous paragraphs is a mode of justification. Like the testing of novel predictions derived from a hypothesis, generative justification begins when the phase of finding and articulating a hypothesis worthy of assessing is drawing to a close. Other approaches to the methodology of discovery are directly concerned with the procedures involved in devising new hypotheses. The argument in favor of this kind of methodology is that the procedures of devising new hypotheses already include elements of appraisal. These preliminary assessments have been termed “weak” evaluation procedures (Schaffner 1993). Weak evaluations are relevant during the process of devising a new hypothesis. They provide reasons for accepting a hypothesis as promising and worthy of further attention. Strong evaluations, by contrast, provide reasons for accepting a hypothesis as (approximately) true or confirmed. Both “generative” and “consequential” testing as discussed in the previous section are strong evaluation procedures. Strong evaluation procedures are rigorous and systematically organized according to the principles of hypothesis derivation or H-D testing. A methodology of preliminary appraisal, by contrast, articulates criteria for the evaluation of a hypothesis prior to rigorous derivation or testing. It aids the decision about whether to take that hypothesis seriously enough to develop it further and test it. For advocates of this version of the methodology of discovery, it is the task of philosophy of science to characterize sets of constraints and methodological rules guiding the complex process of prior-to-test evaluation of hypotheses.

In contrast to the computational approaches discussed above, strategies of preliminary appraisal are not regarded as subject-neutral but as specific to particular fields of study. Philosophers of biology, for instance, have developed a fine-grained framework to account for the generation and preliminary evaluation of biological mechanisms (Darden 2002; Craver 2002; Bechtel and Richardson 1993; Craver and Darden 2013). Some philosophers have suggested that the phase of preliminary appraisal be further divided into two phases, the phase of appraising and the phase of revising. According to Lindley Darden, the phases of generation, appraisal and revision of descriptions of mechanisms can be characterized as reasoning processes governed by reasoning strategies. Different reasoning strategies govern the different phases (Darden 1991, 2002; Craver 2002; Darden 2009). The generation of hypotheses about mechanisms, for instance, is governed by the strategy of “schema instantiation” (see Darden 2002). The discovery of the mechanism of protein synthesis involved the instantiation of an abstract schema for chemical reactions: reactant 1 + reactant 2 = product. The actual mechanism of protein synthesis was found through specification and modification of this schema.

Neither of these strategies is deemed necessary for discovery, and they are not prescriptions for biological research. Rather, these strategies are deemed sufficient for the discovery of mechanisms. The methodology of the discovery of mechanisms is an extrapolation from past episodes of research on mechanisms and the result of a synthesis of rational reconstructions of several of these historical episodes. The methodology of discovery is weakly normative in the sense that the strategies for the discovery of mechanisms that were successful in the past may prove useful in future biological research (Darden 2002).

As philosophers of science have again become more attuned to actual scientific practices, interest in heuristic strategies has also been revived. Many analysts now agree that discovery processes can be regarded as problem solving activities, whereby a discovery is a solution to a problem. Heuristics-based methodologies of discovery are neither purely subjective and intuitive nor algorithmic or formalizable; the point is that reasons can be given for pursuing one or the other problem-solving strategy. These rules are open and do not guarantee a solution to a problem when applied (Ippoliti 2018). On this view, scientific researchers are no longer seen as Kuhnian “puzzle solvers” but as problem solvers and decision makers in complex, variable, and changing environments (Wimsatt 2007).

Philosophers of discovery working in this tradition draw on a growing body of literature in cognitive psychology, management science, operations research, and economy on human reasoning and decision making in contexts with limited information, under time constraints, and with sub-optimal means (Gigerenzer & Sturm 2012). Heuristic strategies characterized in these studies, such as Gigerenzer’s “tools to theory heuristic” are then applied to understand scientific knowledge generation (Gigerenzer 1992, Nickles 2018). Other analysts specify heuristic strategies in a range of scientific fields, including climate science, neurobiology, and clinical medicine (Gramelsberger 2011, Schaffner 2008, Gillies 2018). Finally, in analytic epistemology, formal methods are developed to identify and assess distinct heuristic strategies currently in use, such as Bayesian reverse engineering in cognitive science (Zednik and Jäkel 2016).

As the literature on heuristics continues to grow, it has become clear that the term “heuristics” is itself used in a variety of different ways. (For a valuable taxonomy of meanings of “heuristic,” see Chow 2015, see also Ippoliti 2018.) Moreover, as in the context of earlier debates about computational heuristics, debates continue about the limitations of heuristics. The use of heuristics may come at a cost if heuristics introduce systematic biases (Wimsatt 2007). Some philosophers thus call for general principles for the evaluation of heuristic strategies (Hey 2016).

9. Cognitive perspectives on discovery

The approaches to scientific discovery presented in the previous sections focus on the adoption, articulation, and preliminary evaluation of ideas or hypotheses prior to rigorous testing, not on how a novel hypothesis or idea is first thought up. For a long time, the predominant view among philosophers of discovery was that the initial step of discovery is a mysterious intuitive leap of the human mind that cannot be analyzed further. More recent accounts of discovery informed by evolutionary biology also do not explicate how new ideas are formed. The generation of new ideas is akin to random, blind variations of thought processes, which have to be inspected by the critical mind and assessed as neutral, productive, or useless (Campbell 1960; see also Hull 1988), but the key processes by which new ideas are generated are left unanalyzed.

With the recent rapprochement among philosophy of mind, cognitive science and psychology and the increased integration of empirical research into philosophy of science, these processes have been submitted to closer analysis, and philosophical studies of creativity have seen a surge of interest (e.g. Paul & Kaufman 2014a). The distinctive feature of these studies is that they integrate philosophical analyses with empirical work from cognitive science, psychology, evolutionary biology, and computational neuroscience (Thagard 2012). Analysts have distinguished different kinds and different features of creative thinking and have examined certain features in depth, and from new angles. Recent philosophical research on creativity comprises conceptual analyses and integrated approaches based on the assumption that creativity can be analyzed and that empirical research can contribute to the analysis (Paul & Kaufman 2014b). Two key elements of the cognitive processes involved in creative thinking that have been in the focus of philosophical analysis are analogies ( section 9.2 ) and mental models ( section 9.3 ).

General definitions of creativity highlight novelty or originality and significance or value as distinctive features of a creative act or product (Sternberg & Lubart 1999, Kieran 2014, Paul & Kaufman 2014b, although see Hills & Bird 2019). Different kinds of creativity can be distinguished depending on whether the act or product is novel for a particular individual or entirely novel. Psychologist Margaret Boden distinguishes between psychological creativity (P-creativity) and historical creativity (H-creativity). P-creativity is a development that is new, surprising and important to the particular person who comes up with it. H-creativity, by contrast, is radically novel, surprising, and important—it is generated for the first time (Boden 2004). Further distinctions have been proposed, such as anthropological creativity (construed as a human condition) and metaphysical creativity, a radically new thought or action in the sense that it is unaccounted for by antecedents and available knowledge, and thus constitutes a radical break with the past (Kronfeldner 2009, drawing on Hausman 1984).

Psychological studies analyze the personality traits and creative individuals’ behavioral dispositions that are conducive to creative thinking. They suggest that creative scientists share certain distinct personality traits, including confidence, openness, dominance, independence, introversion, as well as arrogance and hostility. (For overviews of recent studies on personality traits of creative scientists, see Feist 1999, 2006: chapter 5).

Recent work on creativity in philosophy of mind and cognitive science offers substantive analyses of the cognitive and neural mechanisms involved in creative thinking (Abrams 2018, Minai et al 2022) and critical scrutiny of the romantic idea of genius creativity as something deeply mysterious (Blackburn 2014). Some of this research aims to characterize features that are common to all creative processes, such as Thagard and Stewart’s account according to which creativity results from combinations of representations (Thagard & Stewart 2011, but see Pasquale and Poirier 2016). Other research aims to identify the features that are distinctive of scientific creativity as opposed to other forms of creativity, such as artistic creativity or creative technological invention (Simonton 2014).

Many philosophers of science highlight the role of analogy in the development of new knowledge, whereby analogy is understood as a process of bringing ideas that are well understood in one domain to bear on a new domain (Thagard 1984; Holyoak and Thagard 1996). An important source for philosophical thought about analogy is Mary Hesse’s conception of models and analogies in theory construction and development. In this approach, analogies are similarities between different domains. Hesse introduces the distinction between positive, negative, and neutral analogies (Hesse 1966: 8). If we consider the relation between gas molecules and a model for gas, namely a collection of billiard balls in random motion, we will find properties that are common to both domains (positive analogy) as well as properties that can only be ascribed to the model but not to the target domain (negative analogy). There is a positive analogy between gas molecules and a collection of billiard balls because both the balls and the molecules move randomly. There is a negative analogy between the domains because billiard balls are colored, hard, and shiny but gas molecules do not have these properties. The most interesting properties are those properties of the model about which we do not know whether they are positive or negative analogies. This set of properties is the neutral analogy. These properties are the significant properties because they might lead to new insights about the less familiar domain. From our knowledge about the familiar billiard balls, we may be able to derive new predictions about the behavior of gas molecules, which we could then test.

Hesse offers a more detailed analysis of the structure of analogical reasoning through the distinction between horizontal and vertical analogies between domains. Horizontal analogies between two domains concern the sameness or similarity between properties of both domains. If we consider sound and light waves, there are similarities between them: sound echoes, light reflects; sound is loud, light is bright, both sound and light are detectable by our senses. There are also relations among the properties within one domain, such as the causal relation between sound and the loud tone we hear and, analogously, between physical light and the bright light we see. These analogies are vertical analogies. For Hesse, vertical analogies hold the key for the construction of new theories.

Analogies play several roles in science. Not only do they contribute to discovery but they also play a role in the development and evaluation of scientific theories. Current discussions about analogy and discovery have expanded and refined Hesse’s approach in various ways. Some philosophers have developed criteria for evaluating analogy arguments (Bartha 2010). Other work has identified highly significant analogies that were particularly fruitful for the advancement of science (Holyoak and Thagard 1996: 186–188; Thagard 1999: chapter 9). The majority of analysts explore the features of the cognitive mechanisms through which aspects of a familiar domain or source are applied to an unknown target domain in order to understand what is unknown. According to the influential multi-constraint theory of analogical reasoning developed by Holyoak and Thagard, the transfer processes involved in analogical reasoning (scientific and otherwise) are guided or constrained in three main ways: 1) by the direct similarity between the elements involved; 2) by the structural parallels between source and target domain; as well as 3) by the purposes of the investigators, i.e., the reasons why the analogy is considered. Discovery, the formulation of a new hypothesis, is one such purpose.

“In vivo” investigations of scientists reasoning in their laboratories have not only shown that analogical reasoning is a key component of scientific practice, but also that the distance between source and target depends on the purpose for which analogies are sought. Scientists trying to fix experimental problems draw analogies between targets and sources from highly similar domains. In contrast, scientists attempting to formulate new models or concepts draw analogies between less similar domains. Analogies between radically different domains, however, are rare (Dunbar 1997, 2001).

In current cognitive science, human cognition is often explored in terms of model-based reasoning. The starting point of this approach is the notion that much of human reasoning, including probabilistic and causal reasoning as well as problem solving takes place through mental modeling rather than through the application of logic or methodological criteria to a set of propositions (Johnson-Laird 1983; Magnani et al. 1999; Magnani and Nersessian 2002). In model-based reasoning, the mind constructs a structural representation of a real-world or imaginary situation and manipulates this structure. In this perspective, conceptual structures are viewed as models and conceptual innovation as constructing new models through various modeling operations. Analogical reasoning—analogical modeling—is regarded as one of three main forms of model-based reasoning that appear to be relevant for conceptual innovation in science. Besides analogical modeling, visual modeling and simulative modeling or thought experiments also play key roles (Nersessian 1992, 1999, 2009). These modeling practices are constructive in that they aid the development of novel mental models. The key elements of model-based reasoning are the call on knowledge of generative principles and constraints for physical models in a source domain and the use of various forms of abstraction. Conceptual innovation results from the creation of new concepts through processes that abstract and integrate source and target domains into new models (Nersessian 2009).

Some critics have argued that despite the large amount of work on the topic, the notion of mental model is not sufficiently clear. Thagard seeks to clarify the concept by characterizing mental models in terms of neural processes (Thagard 2010). In his approach, mental models are produced through complex patterns of neural firing, whereby the neurons and the interconnections between them are dynamic and changing. A pattern of firing neurons is a representation when there is a stable causal correlation between the pattern or activation and the thing that is represented. In this research, questions about the nature of model-based reasoning are transformed into questions about the brain mechanisms that produce mental representations.

The above sections again show that the study of scientific discovery integrates different approaches, combining conceptual analysis of processes of knowledge generation with empirical work on creativity, drawing heavily and explicitly on current research in psychology and cognitive science, and on in vivo laboratory observations, as well as brain imaging techniques (Kounios & Beeman 2009, Thagard & Stewart 2011).

Earlier critics of AI-based theories of scientific discoveries argued that a computer cannot devise new concepts but is confined to the concepts included in the given computer language (Hempel 1985: 119–120). It cannot design new experiments, instruments, or methods. Subsequent computational research on scientific discovery was driven by the motivation to contribute computational tools to aid scientists in their research (Addis et al. 2016). It appears that computational methods can be used to generate new results leading to refereed scientific publications in astrophysics, cancer research, ecology, and other fields (Langley 2000). However, the philosophical discussion has continued about the question of whether these methods really generate new knowledge or whether they merely speed up data processing. It is also still an open question whether data-intensive science is fundamentally different from traditional research, for instance regarding the status of hypothesis or theory in data-intensive research (Pietsch 2015).

In the wake of recent developments in machine learning, some older discussions about automated discovery have been revived. The availability of vastly improved computational tools and software for data analysis has stimulated new discussions about computer-generated discovery (see Leonelli 2020). It is largely uncontroversial that machine learning tools can aid discovery, for instance in research on antibiotics (Stokes et al, 2020). The notion of “robot scientist” is mostly used metaphorically, and the vision that human scientists may one day be replaced by computers – by successors of the laboratory automation systems “Adam” and “Eve”, allegedly the first “robot scientists” – is evoked in writings for broader audiences (see King et al. 2009, Williams et al. 2015, for popularized descriptions of these systems), although some interesting ethical challenges do arise from “superhuman AI” (see Russell 2021). It also appears that, on the notion that products of creative acts are both novel and valuable, AI systems should be called “creative,” an implication which not all analysts will find plausible (Boden 2014)

Philosophical analyses focus on various questions arising from the processes involving human-machine complexes. One issue relevant to the problem of scientific discovery arises from the opacity of machine learning. If machine learning indeed escapes human understanding, how can we be warranted to say that knowledge or understanding is generated by deep learning tools? Might we have reason to say that humans and machines are “co-developers” of knowledge (Tamaddoni-Nezhad et al. 2021)?

New perspectives on scientific discovery have also opened up in the context of social epistemology (see Goldman & O’Connor 2021). Social epistemology investigates knowledge production as a group process, specifically the epistemic effects of group composition in terms of cognitive diversity and unity and social interactions within groups or institutions such as testimony and trust, peer disagreement and critique, and group justification, among others. On this view, discovery is a collective achievement, and the task is to explore how assorted social-epistemic activities or practices have an impact on the knowledge generated by groups in question. There are obvious implications for debates about scientific discovery of recent research in the different branches of social epistemology. Social epistemologists have examined individual cognitive agents in their roles as group members (as providers of information or as critics) and the interactions among these members (Longino 2001), groups as aggregates of diverse agents, or the entire group as epistemic agent (e.g., Koons 2021, Dragos 2019).

Standpoint theory, for instance, explores the role of outsiders in knowledge generation, considering how the sociocultural structures and practices in which individuals are embedded aid or obstruct the generation of creative ideas. According to standpoint theorists, people with standpoint are politically aware and politically engaged people outside the mainstream. Because people with standpoint have different experiences and access to different domains of expertise than most members of a culture, they can draw on rich conceptual resources for creative thinking (Solomon 2007).

Social epistemologists examining groups as aggregates of agents consider to what extent diversity among group members is conducive to knowledge production and whether and to what extent beliefs and attitudes must be shared among group members to make collective knowledge possible (Bird 2014). This is still an open question. Some formal approaches to model the influence of diversity on knowledge generation suggest that cognitive diversity is beneficial to collective knowledge generation (Weisberg and Muldoon 2009), but others have criticized the model (Alexander et al (2015), see also Thoma (2015) and Poyhönen (2017) for further discussion).

This essay has illustrated that philosophy of discovery has come full circle. Philosophy of discovery has once again become a thriving field of philosophical study, now intersecting with, and drawing on philosophical and empirical studies of creative thinking, problem solving under uncertainty, collective knowledge production, and machine learning. Recent approaches to discovery are typically explicitly interdisciplinary and integrative, cutting across previous distinctions among hypothesis generation and theory building, data collection, assessment, and selection; as well as descriptive-analytic, historical, and normative perspectives (Danks & Ippoliti 2018, Michel 2021). The goal no longer is to provide one overarching account of scientific discovery but to produce multifaceted analyses of past and present activities of knowledge generation in all their complexity and heterogeneity that are illuminating to the non-scientist and the scientific researcher alike.

- Abraham, A. 2019, The Neuroscience of Creativity, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Addis, M., Sozou, P.D., Gobet, F. and Lane, P. R., 2016, “Computational scientific discovery and cognitive science theories”, in Mueller, V. C. (ed.) Computing and Philosophy , Springer, 83–87.