The Importance of Values and Virtues

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Values are the main beliefs of a person, which can either be their lifetime goal or represent their preferred behavior. These features have a significant impact on the way a person acts and their attitude. To further illustrate this concept in a more detailed manner, I will refer to a couple of the values I follow, while depicting a situation when I have broken them. Afterward, I will depict a situation where I happened to have broken them.

For my example, I will use two out of the ten motivational values listed by Schwartz and his colleagues. Said values may be differentiated by referring to two pairs of opposite dimensions: conservation and openness to change, self-transcendence, and self-enhancement (Lecture 2, n. d.). I am a strong supporter of benevolence and universalism; unfortunately, there was one case when I failed to follow these values that I consider to be important.

One day, my friend needed my help with a project for her job assignment. Unfortunately, due to a conflict that had happened before it, I instantly declined the request. During that time, I had no regard for the possible outcome of the event. However, as expected, my reluctance to help my friend with the project resulted in her losing the opportunity to get a raise at her job.

By doing so, I had broken the two aforementioned virtues: benevolence and universalism. My friend’s well-being at the time did not matter to me, as it normally would have, thus, violating benevolence (Lecture 2, n. d.). Since our conflict mattered more to me than the possible outcome of my not helping my friend, I had no regard for universalism at the time. This, in turn, is a prime example of a conflict between two opposite dimensions: self-transcendence versus self-enhancement. I have chosen power and hedonism (pleasing my hurt feelings and putting my friend in a fragile position) over benevolence and universalism.

The aforementioned situation raises the question of how I would support these values. Understandably, the conflict makes my claim quite questionable, as I had failed to follow my beliefs in that case. Fortunately, a few weeks after the conflict, I experienced two situations, where I used the opportunity to uphold these values. These two events, in a way, helped me redeem myself after what had happened.

One day, I came across a situation where my coworker needed my help in creating some contracts for his assignment. While I had some errands to finish myself, I couldn’t decline the request, so I agreed. Although my colleague’s assignment was quite hard, I successfully finished it. This, in turn, resulted in him getting an impressive raise. By doing so, I managed to uphold one of the two values: benevolence.

One week later, my coworkers and I were at a group meeting with our boss. The goal of the meeting was to brainstorm some ideas for our future project. One of my colleagues suggested an idea that I did not like, for I found it quite ridiculous. As she was sitting by the same desk next to me, she asked me if I had any ideas. Having heard my idea, my coworker told me that it was too dangerous for the future of the company and provided a reasonable explanation for this opinion. Thus, I chose not to suggest my idea to protect the company and uphold another value: universalism.

The importance of values can be defined by the role they play in one’s life. They represent realistic goals that help a person navigate through their life. Moreover, values assist people in differentiating right from wrong and help them make ethical decisions. In the two aforementioned situations, I successfully followed my two values: universalism and benevolence. These two beliefs will assist me in becoming a better person and prevent me from making the wrong decisions.

Lecture 2 – Values, Virtues and Character. (n. d.) PowerPoint.

- Ethical Decision-Making: Aristotle on the Sources of the Ethical Life

- Equality of Victims in the Legal System

- Mansoor’s ‘Universalism’ vs. Harris’ ‘Transnationalism’

- Universalism vs. Social Contract in Organizations

- Has the European Integration Process since 1950s Reflect Carl Schmitt's Critique on Universalism?

- Payment to Organ Donors: Why It Needs to Be Abandoned

- Ethical Codes and Their Importance

- Ethics of Television Reality Shows

- Global Poverty: Famine, Affluence, and Morality

- A Controversial Process of Abortion

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, April 10). The Importance of Values and Virtues. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-importance-of-values-and-virtues/

"The Importance of Values and Virtues." IvyPanda , 10 Apr. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/the-importance-of-values-and-virtues/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'The Importance of Values and Virtues'. 10 April.

IvyPanda . 2023. "The Importance of Values and Virtues." April 10, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-importance-of-values-and-virtues/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Importance of Values and Virtues." April 10, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-importance-of-values-and-virtues/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Importance of Values and Virtues." April 10, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-importance-of-values-and-virtues/.

- Environment

- Information Science

- Social Issues

- Argumentative

- Cause and Effect

- Classification

- Compare and Contrast

- Descriptive

- Exemplification

- Informative

- Controversial

- Exploratory

- What Is an Essay

- Length of an Essay

- Generate Ideas

- Types of Essays

- Structuring an Essay

- Outline For Essay

- Essay Introduction

- Thesis Statement

- Body of an Essay

- Writing a Conclusion

- Essay Writing Tips

- Drafting an Essay

- Revision Process

- Fix a Broken Essay

- Format of an Essay

- Essay Examples

- Essay Checklist

- Essay Writing Service

- Pay for Research Paper

- Write My Research Paper

- Write My Essay

- Custom Essay Writing Service

- Admission Essay Writing Service

- Pay for Essay

- Academic Ghostwriting

- Write My Book Report

- Case Study Writing Service

- Dissertation Writing Service

- Coursework Writing Service

- Lab Report Writing Service

- Do My Assignment

- Buy College Papers

- Capstone Project Writing Service

- Buy Research Paper

- Custom Essays for Sale

Can’t find a perfect paper?

- Free Essay Samples

Values and Virtues

Updated 03 June 2022

Subject Behavior

Downloads 52

Category Philosophy , Psychology , Sociology

Topic Conformity , Society , Virtue

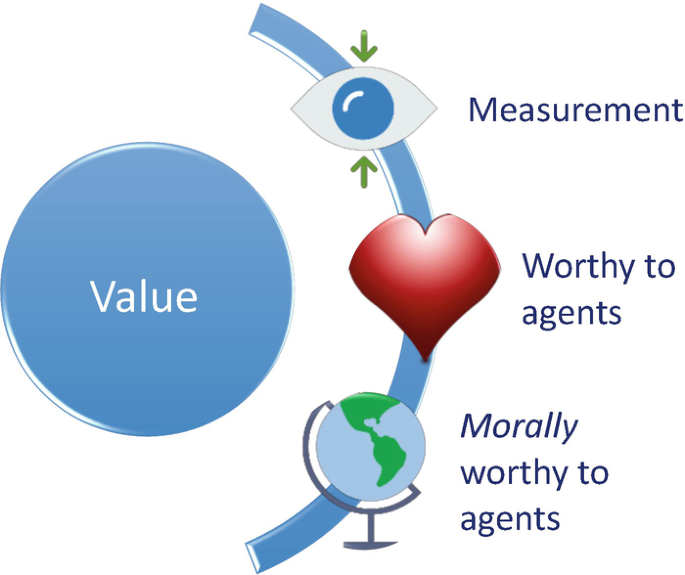

Virtues are described in a given institution or community as conforming to a standard of moral or correct excellence, whereas values are regarded as culturally accepted norms. Values are, in turn, the commonly accepted and appropriate ways of behaving associated with particular performance. Workplace principles, for example, play an important role in defining the guidelines or boundaries for the actions of employees. As such, the organizational principles are part and parcel of the business that drives the output of the company. Since principles are integrated as part of business goals, virtues act as the instrument to achieve these goals. Therefore, virtues are characteristics of an individual, which support collective well-being and moral excellence. They are mainly the innate qualities that do not always align with societal or organizational values (Baer, 2015). It is, however, of the essence to realize that both values and virtues are essential in a company or community for success and peaceful coexistence respectively. Although the two concepts, value, and virtue are similar regarding describing things that a person or society finds desirable, there is a lot of overlap between virtues and values. For instance, virtues explain an ideal that people or workplace groups look up to and try to emulate; on the other hand, values describe what an individual might hold dear and finds valuable. As such, it can be possible that values are not necessarily moral as they are based on personal perspectives, which are diverse and can be positive and negative. However, virtues will always be based on morality since they are developed for the entire population in a community as the positive attributes acceptable to all people (Crossan, Mazutis, & Seijts, 2013). Virtues have been continuously passed on into consecutive generations, while values form from a person’s view of the world. ReferencesBaer, R. (2015). Ethics, values, virtues, and character strengths in mindfulness-based interventions: a psychological science perspective. Mindfulness, 6(4), 956-969.Crossan, M., Mazutis, D., & Seijts, G. (2013). In search of virtue: The role of virtues, values and character strengths in ethical decision making. Journal of Business Ethics, 113(4), 567-581.

Deadline is approaching?

Wait no more. Let us write you an essay from scratch

Related Essays

Related topics.

Find Out the Cost of Your Paper

Type your email

By clicking “Submit”, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy policy. Sometimes you will receive account related emails.

Essays About Values: 5 Essay Examples Plus 10 Prompts

Similar to how our values guide us, let this guide with essays about values and writing prompts help you write your essay.

Values are the core principles that guide the actions we take and the choices we make. They are the cornerstones of our identity. On a community or organizational level, values are the moral code that every member must embrace to live harmoniously and work together towards shared goals.

We acquire our values from different sources such as parents, mentors, friends, cultures, and experiences. All of these build on one another — some rejected as we see fit — for us to form our perception of our values and what will lead us to a happy and fulfilled life.

| IMAGE | PRODUCT | |

|---|---|---|

| Grammarly | ||

| ProWritingAid |

5 Essay Examples

1. what today’s classrooms can learn from ancient cultures by linda flanagan, 2. stand out to your hiring panel with a personal value statement by maggie wooll, 3. make your values mean something by patrick m. lencioni, 4. how greed outstripped need by beth azar, 5. a shift in american family values is fueling estrangement by joshua coleman, 1. my core values, 2. how my upbringing shaped my values, 3. values of today’s youth, 4. values of a good friend, 5. an experience that shaped your values, 6. remembering our values when innovating, 7. important values of school culture, 8. books that influenced your values, 9. religious faith and moral values, 10. schwartz’s theory of basic values.

“Connectedness is another core value among Maya families, and teachers seek to cultivate it… While many American teachers also value relationships with their students, that effort is undermined by the competitive environment seen in many Western classrooms.”

Ancient communities keep their traditions and values of a hands-off approach to raising their kids. They also preserve their hunter-gatherer mindsets and others that help their kids gain patience, initiative, a sense of connectedness, and other qualities that make a helpful child.

“How do you align with the company’s mission and add to its culture? Because it contains such vital information, your personal value statement should stand out on your resume or in your application package.”

Want to rise above other candidates in the jobs market? Then always highlight your value statement. A personal value statement should be short but still, capture the aspirations and values of the company. The essay provides an example of a captivating value statement and tips for crafting one.

“Values can set a company apart from the competition by clarifying its identity and serving as a rallying point for employees. But coming up with strong values—and sticking to them—requires real guts.”

Along with the mission and vision, clear values should dictate a company’s strategic goals. However, several CEOs still needed help to grasp organizational values fully. The essay offers a direction in setting these values and impresses on readers the necessity to preserve them at all costs.

“‘He compared the values held by people in countries with more competitive forms of capitalism with the values of folks in countries that have a more cooperative style of capitalism… These countries rely more on strategic cooperation… rather than relying mostly on free-market competition as the United States does.”

The form of capitalism we have created today has shaped our high value for material happiness. In this process, psychologists said we have allowed our moral and ethical values to drift away from us for greed to take over. You can also check out these essays about utopia .

“From the adult child’s perspective, there might be much to gain from an estrangement: the liberation from those perceived as hurtful or oppressive, the claiming of authority in a relationship, and the sense of control over which people to keep in one’s life. For the mother or father, there is little benefit when their child cuts off contact.”

It is most challenging when the bonds between parent and child weaken in later years. Psychologists have been navigating this problem among modern families, which is not an easy conflict to resolve. It requires both parties to give their best in humbling themselves and understanding their loved ones, no matter how divergent their values are.

10 Writing Prompts On Essays About Values

For this topic prompt, contemplate your non-negotiable core values and why you strive to observe them at all costs. For example, you might value honesty and integrity above all else. Expound on why cultivating fundamental values leads to a happy and meaningful life. Finally, ponder other values you would like to gain for your future self. Write down how you have been practicing to adopt these aspired values.

Many of our values may have been instilled in us during childhood. This essay discusses the essential values you gained from your parents or teachers while growing up. Expound on their importance in helping you flourish in your adult years. Then, offer recommendations on what households, schools, or communities can do to ensure that more young people adopt these values.

Is today’s youth lacking essential values, or is there simply a shift in what values generations uphold? Strive to answer this and write down the healthy values that are emerging and dying. Then think of ways society can preserve healthy values while doing away with bad ones. Of course, this change will always start at home, so also encourage parents, as role models, to be mindful of their words, actions and behavior.

The greatest gift in life is friendship. In this essay, enumerate the top values a friend should have. You may use your best friend as an example. Then, cite the best traits your best friend has that have influenced you to be a better version of yourself. Finally, expound on how these values can effectively sustain a healthy friendship in the long term.

We all have that one defining experience that has forever changed how we see life and the values we hold dear. Describe yours through storytelling with the help of our storytelling guide . This experience may involve a decision, a conversation you had with someone, or a speech you heard at an event.

With today’s innovation, scientists can make positive changes happen. But can we truly exercise our values when we fiddle with new technologies whose full extent of positive and adverse effects we do not yet understand such as AI? Contemplate this question and look into existing regulations on how we curb the creation or use of technologies that go against our values. Finally, assess these rules’ effectiveness and other options society has.

Highlight a school’s role in honing a person’s values. Then, look into the different aspects of your school’s culture. Identify which best practices distinct in your school are helping students develop their values. You could consider whether your teachers exhibit themselves as admirable role models or specific parts of the curriculum that help you build good character.

In this essay, recommend your readers to pick up your favorite books, particularly those that served as pathways to enlightening insights and values. To start, provide a summary of the book’s story. It would be better if you could do so without revealing too much to avoid spoiling your readers’ experience. Then, elaborate on how you have applied the values you learned from the book.

For many, religious faith is the underlying reason for their values. For this prompt, explore further the inextricable links between religion and values. If you identify with a certain religion, share your thoughts on the values your sector subscribes to. You can also tread the more controversial path on the conflicts of religious values with socially accepted beliefs or practices, such as abortion.

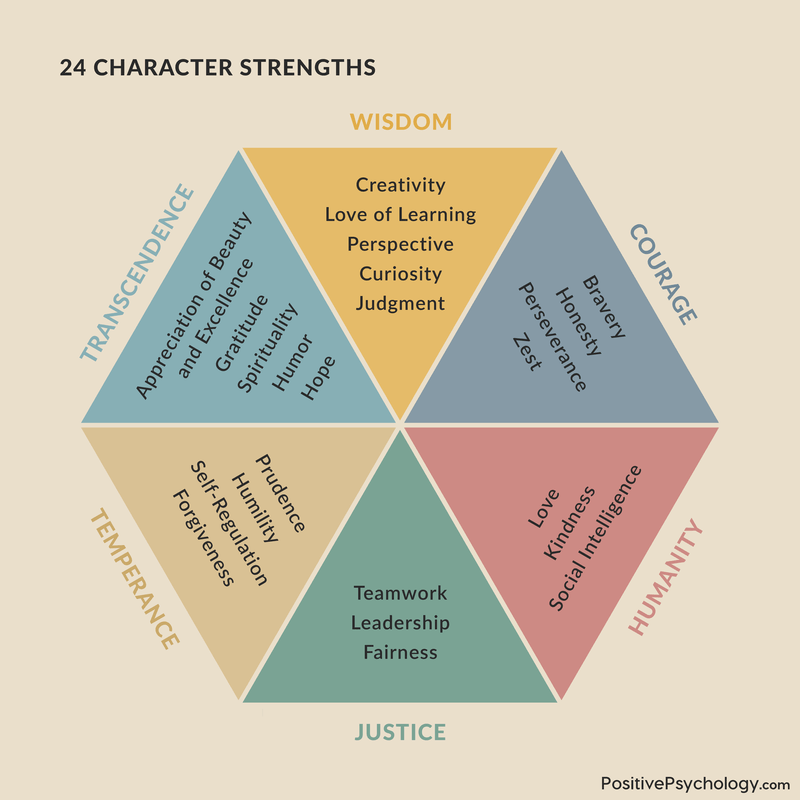

Dive deeper into the ten universal values that social psychologist Shalom Schwartz came up with: power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, self-direction, universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, and security. Look into their connections and conflicts against each other. Then, pick your favorite value and explain how you relate to it the most. Also, find if value conflicts within you, as theorized by Schwartz.

Make sure to check out our round-up of the best essay checkers . If you want to use the latest grammar software, read our guide on using an AI grammar checker .

Essay on Values for Students and Children

500+ words essay on values.

Importance of Values

For an individual, values are most important. An individual with good values is loved by everyone around as he is compassionate about others and also he behaves ethically.

Values Help in Decision Making

A person is able to judge what is right and what is wrong based on the values he imbibes. In life at various steps, it makes the decision-making process easier. A person with good values is always likely to make better decisions than others.

Values Can Give Direction to Our Life

In life, Values give us clear goals. They always tell us how we should behave and act in different situations and give the right direction to our life. In life, a person with good values can take better charge.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Values Can Build Character

If a person wants a strong character, then he has to possesses good values such as honesty , loyalty, reliability, efficiency, consistency, compassion, determination, and courage. Values always help in building our character.

Values Can Help in Building a Society

If u want a better society then people need to bear good values. Values play an important role in society. They only need to do their hard work, with compassion, honesty, and other values. Such people will help in the growth of society and make it a much better place to live.

Characteristics of Values

Values are always based on various things. While the basic values remain the same across cultures and are intact since centuries some values may vary. Values may be specific to a society or age. In the past, it was considered that women with good moral values must stay at home and not voice their opinion on anything but however, this has changed over time. Our culture and society determine the values to a large extent. We imbibe values during our childhood years and they remain with us throughout our life.

Family always plays the most important role in rendering values to us. Decisions in life are largely based on the values we possess. Values are permanent and seldom change. A person is always known by the values he possesses. The values of a person always reflect on his attitude and overall personality.

The Decline of Values in the Modern Times

While values are of great importance and we are all aware of the same unfortunately people these days are so engrossed in making money and building a good lifestyle that they often overlook the importance of values. At the age when children must be taught good values, they are taught to fight and survive in this competitive world. Their academics and performance in other activities are given importance over their values.

Parents , as well as teachers, teach them how to take on each other and win by any means instead of inculcating good sportsman spirit in them and teaching them values such as integrity, compassion, and patience. Children always look up to their elders as their role models and it is unfortunate that elders these days have a lack of values. Therefore the children learn the same.

In order to help him grow into a responsible and wise human being, it is important for people to realize that values must be given topmost priority in a child’s life because children are the future of the society. There can be nothing better in a society where a majority of people have good values and they follow the ethical norms.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

Virtues and Vices: and other essays in moral philosophy

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This collection of essays, written between 1957 and 1977, contains discussions of the moral philosophy of David Hume, Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Nietzsche, and some modern philosophers. It presents virtues and vices rather than rights and duties as the central concepts in moral philosophy. Throughout, the author rejects contemporary anti‐ naturalistic moral philosophies such as emotivism and prescriptivism, but defends the view that moral judgements may be hypothetical rather than (as Kant thought) categorical imperatives. The author also applies her moral philosophy to the current debates on euthanasia and abortion, the latter discussed in relation to the doctrine of the double effect. She argues against the suggestion, on the part of A. J. Ayer and others, that free will actually requires determinism. In a final essay, she asks whether the concept of moral approval can be understood except against a particular background of social practices.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 18 |

| October 2022 | 5 |

| October 2022 | 3 |

| October 2022 | 3 |

| October 2022 | 5 |

| October 2022 | 5 |

| October 2022 | 2 |

| October 2022 | 3 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 17 |

| October 2022 | 14 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 7 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 133 |

| October 2022 | 141 |

| October 2022 | 20 |

| October 2022 | 4 |

| October 2022 | 8 |

| October 2022 | 11 |

| October 2022 | 26 |

| November 2022 | 6 |

| November 2022 | 2 |

| November 2022 | 6 |

| November 2022 | 15 |

| November 2022 | 4 |

| November 2022 | 4 |

| November 2022 | 103 |

| November 2022 | 125 |

| November 2022 | 3 |

| November 2022 | 3 |

| November 2022 | 11 |

| November 2022 | 7 |

| November 2022 | 2 |

| November 2022 | 2 |

| November 2022 | 1 |

| November 2022 | 1 |

| November 2022 | 19 |

| December 2022 | 17 |

| December 2022 | 1 |

| December 2022 | 4 |

| December 2022 | 1 |

| December 2022 | 9 |

| December 2022 | 87 |

| December 2022 | 6 |

| December 2022 | 6 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 3 |

| December 2022 | 6 |

| December 2022 | 5 |

| December 2022 | 38 |

| December 2022 | 8 |

| December 2022 | 1 |

| January 2023 | 13 |

| January 2023 | 5 |

| January 2023 | 3 |

| January 2023 | 9 |

| January 2023 | 18 |

| January 2023 | 8 |

| January 2023 | 146 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 20 |

| January 2023 | 3 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 22 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 8 |

| January 2023 | 6 |

| January 2023 | 5 |

| January 2023 | 3 |

| January 2023 | 54 |

| January 2023 | 14 |

| January 2023 | 4 |

| February 2023 | 17 |

| February 2023 | 8 |

| February 2023 | 5 |

| February 2023 | 1 |

| February 2023 | 6 |

| February 2023 | 2 |

| February 2023 | 17 |

| February 2023 | 170 |

| February 2023 | 16 |

| February 2023 | 60 |

| February 2023 | 2 |

| February 2023 | 118 |

| February 2023 | 10 |

| February 2023 | 5 |

| February 2023 | 9 |

| February 2023 | 6 |

| March 2023 | 15 |

| March 2023 | 11 |

| March 2023 | 7 |

| March 2023 | 32 |

| March 2023 | 16 |

| March 2023 | 7 |

| March 2023 | 10 |

| March 2023 | 285 |

| March 2023 | 24 |

| March 2023 | 25 |

| March 2023 | 10 |

| March 2023 | 11 |

| March 2023 | 1 |

| March 2023 | 3 |

| March 2023 | 8 |

| March 2023 | 1 |

| March 2023 | 5 |

| March 2023 | 59 |

| March 2023 | 1 |

| March 2023 | 186 |

| April 2023 | 16 |

| April 2023 | 6 |

| April 2023 | 6 |

| April 2023 | 12 |

| April 2023 | 2 |

| April 2023 | 15 |

| April 2023 | 8 |

| April 2023 | 190 |

| April 2023 | 2 |

| April 2023 | 12 |

| April 2023 | 27 |

| April 2023 | 10 |

| April 2023 | 2 |

| April 2023 | 153 |

| April 2023 | 28 |

| April 2023 | 3 |

| April 2023 | 6 |

| April 2023 | 2 |

| April 2023 | 8 |

| April 2023 | 3 |

| May 2023 | 25 |

| May 2023 | 5 |

| May 2023 | 2 |

| May 2023 | 12 |

| May 2023 | 2 |

| May 2023 | 11 |

| May 2023 | 16 |

| May 2023 | 135 |

| May 2023 | 6 |

| May 2023 | 1 |

| May 2023 | 7 |

| May 2023 | 16 |

| May 2023 | 2 |

| May 2023 | 111 |

| May 2023 | 5 |

| May 2023 | 26 |

| May 2023 | 9 |

| May 2023 | 2 |

| May 2023 | 1 |

| May 2023 | 6 |

| June 2023 | 9 |

| June 2023 | 7 |

| June 2023 | 8 |

| June 2023 | 10 |

| June 2023 | 8 |

| June 2023 | 7 |

| June 2023 | 7 |

| June 2023 | 52 |

| June 2023 | 4 |

| June 2023 | 7 |

| June 2023 | 9 |

| June 2023 | 15 |

| June 2023 | 8 |

| June 2023 | 7 |

| June 2023 | 28 |

| June 2023 | 7 |

| June 2023 | 9 |

| June 2023 | 10 |

| June 2023 | 11 |

| June 2023 | 7 |

| June 2023 | 8 |

| July 2023 | 11 |

| July 2023 | 9 |

| July 2023 | 5 |

| July 2023 | 5 |

| July 2023 | 7 |

| July 2023 | 4 |

| July 2023 | 13 |

| July 2023 | 77 |

| July 2023 | 5 |

| July 2023 | 10 |

| July 2023 | 4 |

| July 2023 | 7 |

| July 2023 | 4 |

| July 2023 | 5 |

| July 2023 | 18 |

| July 2023 | 4 |

| July 2023 | 10 |

| July 2023 | 4 |

| July 2023 | 5 |

| August 2023 | 8 |

| August 2023 | 6 |

| August 2023 | 4 |

| August 2023 | 7 |

| August 2023 | 7 |

| August 2023 | 1 |

| August 2023 | 6 |

| August 2023 | 3 |

| August 2023 | 34 |

| August 2023 | 2 |

| August 2023 | 4 |

| August 2023 | 35 |

| August 2023 | 2 |

| August 2023 | 15 |

| August 2023 | 9 |

| August 2023 | 1 |

| August 2023 | 1 |

| August 2023 | 1 |

| September 2023 | 3 |

| September 2023 | 3 |

| September 2023 | 1 |

| September 2023 | 3 |

| September 2023 | 7 |

| September 2023 | 144 |

| September 2023 | 13 |

| September 2023 | 1 |

| September 2023 | 5 |

| September 2023 | 3 |

| September 2023 | 1 |

| September 2023 | 29 |

| September 2023 | 4 |

| September 2023 | 1 |

| September 2023 | 1 |

| September 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 1 |

| October 2023 | 17 |

| October 2023 | 9 |

| October 2023 | 6 |

| October 2023 | 7 |

| October 2023 | 3 |

| October 2023 | 34 |

| October 2023 | 27 |

| October 2023 | 10 |

| October 2023 | 234 |

| October 2023 | 6 |

| October 2023 | 8 |

| October 2023 | 9 |

| October 2023 | 123 |

| October 2023 | 25 |

| October 2023 | 3 |

| October 2023 | 9 |

| October 2023 | 8 |

| October 2023 | 1 |

| October 2023 | 2 |

| October 2023 | 9 |

| November 2023 | 19 |

| November 2023 | 10 |

| November 2023 | 5 |

| November 2023 | 14 |

| November 2023 | 22 |

| November 2023 | 5 |

| November 2023 | 136 |

| November 2023 | 5 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 14 |

| November 2023 | 9 |

| November 2023 | 12 |

| November 2023 | 2 |

| November 2023 | 6 |

| November 2023 | 14 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 4 |

| November 2023 | 132 |

| November 2023 | 14 |

| November 2023 | 6 |

| November 2023 | 9 |

| December 2023 | 12 |

| December 2023 | 11 |

| December 2023 | 7 |

| December 2023 | 3 |

| December 2023 | 9 |

| December 2023 | 8 |

| December 2023 | 5 |

| December 2023 | 3 |

| December 2023 | 48 |

| December 2023 | 91 |

| December 2023 | 2 |

| December 2023 | 3 |

| December 2023 | 2 |

| December 2023 | 3 |

| December 2023 | 3 |

| January 2024 | 19 |

| January 2024 | 6 |

| January 2024 | 15 |

| January 2024 | 9 |

| January 2024 | 10 |

| January 2024 | 2 |

| January 2024 | 9 |

| January 2024 | 49 |

| January 2024 | 15 |

| January 2024 | 4 |

| January 2024 | 120 |

| January 2024 | 8 |

| January 2024 | 4 |

| January 2024 | 1 |

| January 2024 | 6 |

| February 2024 | 33 |

| February 2024 | 14 |

| February 2024 | 4 |

| February 2024 | 37 |

| February 2024 | 6 |

| February 2024 | 13 |

| February 2024 | 4 |

| February 2024 | 308 |

| February 2024 | 5 |

| February 2024 | 10 |

| February 2024 | 1 |

| February 2024 | 12 |

| February 2024 | 24 |

| February 2024 | 18 |

| February 2024 | 72 |

| February 2024 | 5 |

| February 2024 | 4 |

| February 2024 | 168 |

| February 2024 | 6 |

| February 2024 | 11 |

| February 2024 | 8 |

| March 2024 | 26 |

| March 2024 | 12 |

| March 2024 | 10 |

| March 2024 | 48 |

| March 2024 | 17 |

| March 2024 | 343 |

| March 2024 | 12 |

| March 2024 | 6 |

| March 2024 | 8 |

| March 2024 | 8 |

| March 2024 | 6 |

| March 2024 | 12 |

| March 2024 | 2 |

| March 2024 | 10 |

| March 2024 | 6 |

| March 2024 | 9 |

| March 2024 | 6 |

| March 2024 | 194 |

| March 2024 | 9 |

| March 2024 | 42 |

| March 2024 | 7 |

| April 2024 | 35 |

| April 2024 | 13 |

| April 2024 | 2 |

| April 2024 | 15 |

| April 2024 | 12 |

| April 2024 | 150 |

| April 2024 | 15 |

| April 2024 | 13 |

| April 2024 | 2 |

| April 2024 | 18 |

| April 2024 | 2 |

| April 2024 | 9 |

| April 2024 | 62 |

| April 2024 | 30 |

| April 2024 | 88 |

| April 2024 | 11 |

| April 2024 | 15 |

| April 2024 | 9 |

| April 2024 | 3 |

| April 2024 | 1 |

| May 2024 | 6 |

| May 2024 | 7 |

| May 2024 | 6 |

| May 2024 | 9 |

| May 2024 | 7 |

| May 2024 | 11 |

| May 2024 | 1 |

| May 2024 | 1 |

| May 2024 | 230 |

| May 2024 | 2 |

| May 2024 | 22 |

| May 2024 | 22 |

| May 2024 | 12 |

| May 2024 | 1 |

| May 2024 | 28 |

| May 2024 | 146 |

| May 2024 | 2 |

| May 2024 | 3 |

| June 2024 | 10 |

| June 2024 | 7 |

| June 2024 | 4 |

| June 2024 | 7 |

| June 2024 | 6 |

| June 2024 | 17 |

| June 2024 | 2 |

| June 2024 | 74 |

| June 2024 | 5 |

| June 2024 | 4 |

| June 2024 | 6 |

| June 2024 | 1 |

| June 2024 | 15 |

| June 2024 | 4 |

| June 2024 | 10 |

| June 2024 | 5 |

| June 2024 | 107 |

| June 2024 | 8 |

| June 2024 | 1 |

| June 2024 | 11 |

| June 2024 | 4 |

| July 2024 | 8 |

| July 2024 | 9 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 13 |

| July 2024 | 9 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 12 |

| July 2024 | 72 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 1 |

| July 2024 | 15 |

| July 2024 | 13 |

| July 2024 | 44 |

| July 2024 | 5 |

| July 2024 | 4 |

| July 2024 | 16 |

| July 2024 | 6 |

| July 2024 | 3 |

| July 2024 | 3 |

| July 2024 | 7 |

| July 2024 | 7 |

| August 2024 | 2 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

| August 2024 | 5 |

| August 2024 | 23 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

| August 2024 | 8 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

| August 2024 | 30 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

112 Personal Values Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Personal values are the beliefs and principles that guide our decisions and actions in life. They are the core of who we are and what we stand for. Identifying and understanding our personal values is crucial for living a fulfilling and authentic life.

To help you explore and reflect on your personal values, we have compiled a list of 112 essay topic ideas and examples. These topics cover a wide range of values, from honesty and integrity to compassion and empathy. Whether you are writing an essay for a class assignment or simply reflecting on your values, these prompts will help you delve deep into what matters most to you.

- The importance of honesty in relationships

- How integrity shapes our character

- The value of perseverance in achieving our goals

- Why empathy is essential for understanding others

- The role of compassion in building a more caring society

- The significance of gratitude in fostering happiness

- How courage helps us overcome challenges

- The power of forgiveness in healing relationships

- The impact of generosity on others

- The value of respect in building trust

- Why humility is important in personal growth

- The role of responsibility in being a good citizen

- The importance of loyalty in friendships

- How authenticity leads to self-acceptance

- The significance of kindness in a world filled with negativity

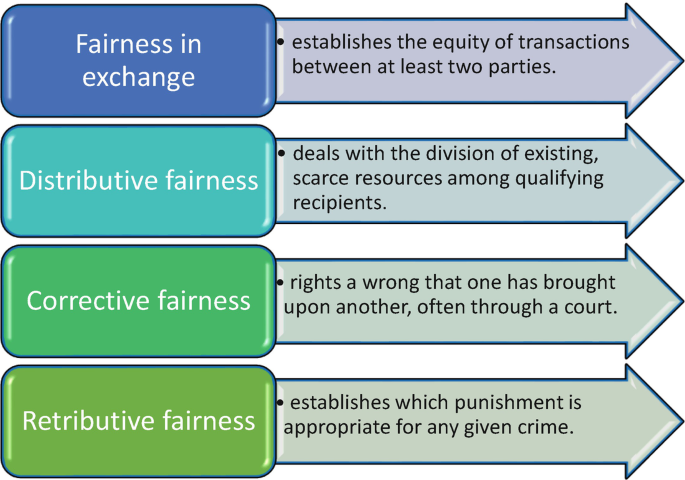

- Why fairness is essential for justice

- The value of patience in dealing with difficult situations

- How self-discipline leads to success

- The impact of open-mindedness on personal growth

- The role of independence in making our own choices

- Why self-care is crucial for mental health

- The importance of self-reflection in personal development

- How mindfulness leads to a more peaceful life

- The value of perseverance in overcoming obstacles

- Why self-respect is key to self-esteem

- The significance of self-awareness in understanding our emotions

- How self-compassion leads to self-acceptance

- The impact of self-confidence on our actions

- The role of self-control in managing impulses

- Why self-expression is important for creativity

- The value of self-improvement in reaching our full potential

- How self-reliance leads to independence

- The importance of selflessness in helping others

- Why selflessness is essential for building strong relationships

- The significance of service to others in making a difference

- How simplicity leads to a more meaningful life

- The impact of sincerity on building trust

- The role of solidarity in standing up for others

- Why spirituality is important for inner peace

- The value of stewardship in protecting the environment

- How strength of character leads to resilience

- The importance of teamwork in achieving common goals

- Why tolerance is crucial for diversity

- The significance of trust in building relationships

- How truthfulness leads to authenticity

- The impact of understanding on resolving conflicts

- The role of unity in creating harmony

- Why uprightness is essential for moral integrity

- The value of virtue in guiding our actions

- How wisdom leads to sound decision-making

- The importance of work ethic in achieving success

- Why ambition is crucial for reaching our goals

- The significance of balance in maintaining harmony

- How beauty leads to appreciation of life

- The impact of belief in oneself on achieving dreams

- The role of boldness in taking risks

- Why creativity is essential for innovation

- The value of curiosity in learning new things

- How determination leads to achievement

- The importance of diligence in pursuing excellence

- Why enthusiasm is crucial for motivation

- The significance of flexibility in adapting to change

- How focus leads to productivity

- The impact of freedom on individual rights

- The role of friendship in providing support

- Why fun is essential for a balanced life

- The value of generosity in giving back

- How growth leads to personal development

- The importance of harmony in relationships

- Why health is crucial for overall well-being

- The significance of honesty in communication

- How humor leads to laughter and joy

- The impact of independence on autonomy

- The role of innovation in progress

- Why justice is essential for fairness

- The value of leadership in guiding others

- How love leads to compassion

- Why moderation is crucial for balance

- The significance of optimism in facing challenges

- How passion leads to fulfillment

- The impact of patience in waiting for results

- The role of perseverance in achieving long-term goals

- Why positivity is essential for a healthy mindset

- The value of purpose in finding meaning in life

- How resilience leads to bouncing back from setbacks

- The importance of responsibility in taking ownership

- Why service to others is crucial for community

- The significance of simplicity in decluttering our lives

- How sincerity leads to trustworthiness

- The impact of social justice on equality

- The role of solidarity in standing up for what is right

- Why spirituality is essential for inner peace

- The value of stewardship in caring for the environment

These essay topics are just a starting point for exploring your personal values. Take the time to reflect on what matters most to you and why these values are important in your life. By understanding and living by your personal values, you can lead a more authentic and fulfilling life.

Want to research companies faster?

Instantly access industry insights

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Leverage powerful AI research capabilities

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2024 Pitchgrade

Inner Strength For Life – The 12 Master Virtues

Our journey of growth in life can be described as a journey of developing both insights and also virtues (qualities of mind and heart). This article maps out what are the main qualities to develop, and what particular strengths or gifts are gained from each of them.

Developing virtues is not about being better than others, but about developing the potential of our own heart and mind. The philosophers of ancient Greece , Buddha , the Yogis, and the Positive Psychology movement all value the cultivation of certain personal qualities. In this essay I attempt to systematize these core strengths into 12 “buckets” or “power virtues”, as many of them share common features.

Each of these virtues, rather than being an inborn personal trait, are habits and states of mind that can be consciously cultivated using a systematic approach.

There are many books written about each of these virtues. In this post I can only cover a brief introduction of each, and suggest some further reading. Finally, I have separated them into virtues of mind and heart only for the sake of exposition – in truth there is great overlap between both.

Let us begin by talking about the need to develop virtues holistically.

Jump to section

What is a Virtue

Balanced self-development, tranquility, virtues list, parting thoughts.

A virtue is a positive character trait that is consider a foundation for living well, and a key ingredient to greatness.

For some, the word “virtue” may have a bit of a Victorian puritanism associated with it. This is not my understanding of it, nor is this the spirit of this article.

Rather, a virtue is a personal asset , a shield to protect us from difficulty, trouble, and suffering. Each virtue is a special sort of “power” that enables us to experience a level of well-being that we wouldn’t be able to access otherwise. Indeed, “virtue”comes from the latin virtus (force, worth, power).

Let’s take the virtue of equanimity as an example.

Developing equanimity protects us from suffering through the ups and downs of life, and saves us from the pain of being criticized, wronged, or left behind. It unlocks a new level of well-being: the emotional stability of knowing we will always be ok.

The same is true for every virtue discussed in this essay.

We all have certain personal qualities more naturally developed than the others. And our tendency is often to double-down on the virtues that we already have, rather than developing complementary virtues . For instance, people who are good at self-discipline may focus on getting even better at that, and overlook the need to develop the opposing virtue of flexibility.

There is no doubt that we need to play our strengths . But when we focus solely on our strengths and use them to overcompensate our weaknesses, the result is often not good. We can become victims of our own blessings.

Let’s take the case of a person whose natural strength is compassion and kindness. In certain relationships, this might be abused by other people (directly or indirectly). Dealing with this situation by becoming kinder would not be wise. Instead, the opposing virtue of self-assertiveness (the courage of setting boundaries), is to be exercised.

Here are some other examples of virtues that are incomplete (and potentially harmful) in isolation:

- Tranquility without joy and energy is stale;

- Detachment and equanimity without love can be cold;

- Trust without wisdom can be blind;

- Morality without humility can be self-righteous;

- Love without wisdom can cause harm to oneself;

- Focus and courage without love and wisdom is just blind power.

It took me years to get to this precious insight – and I’ll probably need a lifetime to learn how to implement it. 😉

Funnily enough, afterwards I discovered that this was already a concept praised by the Stoics. In Stoicism, it is called anacoluthia , the mutual entailment of virtues.

The point is: we need to focus on our strengths, but we also need to pay attention to the virtues we lack the most. Any development in these areas, however small, has the potential to be life-changing. I go deeper into this topic here .

Have a look at your current strengths. What complementary virtues might you be overlooking?

Best Virtues of Mind

“Life shrinks or expands in proportion to one’s courage.” – Anais Nin

Related qualities: boldness, fearlessness, decisiveness, leadership, assertiveness, confidence, magnanimity.

Courage says: “The consequences of this action might be painful for me, but it’s the right thing to do. I’ll do it.”

Courage is the ability to hold on to the feeling “I need to do this”, ignore the fear mongering thoughts, and take action. For a few, it is the absence of fear; for most, it’s the willingness to act despite fear.

Examples: It takes courage to expose yourself, to try something new, to change directions, to take a risk, to let go of an attachment, to say “I was wrong”, to have a difficult conversation, to trust yourself. Its manifestations are many, both in small and big things in life.

Without courage we feel powerless. Because we know what we want to do, or what we need to do, but we lack the boldness to take action. We default to the easy way out, the path of least resistance. It might feel comfortable now, but in the long term it doesn’t make us happy.

Recommended book: Daring Greatly (Brené Brown)

“The more tranquil a man becomes, the greater his success, his influence, his power for good. Calmness of mind is one of the beautiful jewels of wisdom.” – James Allen

Related qualities: serenity, calmness, non-reactivity, gentleness, peace, acceptance.

Tranquility says: “There is no need to stress. All is well.”

Tranquility involves keeping your mind and heart calm, like the ocean’s depth. You take your time to perceive what’s going on and act purposefully, without agitation, without hurry, and without overreacting. On a deeper level, it means to diminish rumination, worries, and useless thinking.

Examples: Taking a deep breath before answering an email or phone call, or before responding to the hurtful behavior of someone else. Being ok with the fact that things are often not going to go as we expect. Not brooding about the past or worrying too much about the future. Shunning busyness in favor of a more purposeful living. Not living in fight-or-flight mode.

Without tranquility we expend more energy than what’s really needed. We experience a constant feeling of stress, anxiety, or agitation in the back of our minds. And sometimes we may be fooling ourselves thinking we are being “active” or “productive”.

Recommended book: The Path to Tranquility (Dalai Lama)

“Success is going from failure to failure without loss of enthusiasm.” -Winston Churchill

Related qualities: energy, enthusiasm, passion, vitality, zeal, perseverance, willpower, determination, discipline, self-control, resolution, mindfulness, steadfastness, tenacity, grit.

Diligence says: “I am committed to this work / habit / path. I will continue it no matter what , even in the face of challenges, discouragement, and tiredness.”

Some may say that it is the most essential virtue for success in any field – career, art, sports or business. It is about making a decision once, in something that is good for you, and then keeping it up despite adversities and mood fluctuations.

Examples: Deciding to stop smoking and never again lighting acigarette. Deciding that I will meditate every day and keeping that up, like a perfect habit chain. Showing up to train / study / work in your passion project day after day, regardless of how you feel. Always getting up as soon as you fall. Having an unbreakable, almost stubborn, determination. Treating challenges like energy bars.

Without diligence we can’t accomplish anything meaningful. We can’t properly take care of our health, finances, mind, or relationships. We give up on everything too soon. We can’t create good habits, break bad habits, or manifest the things we want in our lives. We are a victim of circumstances, social/familial conditioning, and genetics.

Recommended books: The Willpower Instinct (Kelly McGonigal), Grit (Angela Duckworth), Power of Habit (Charles Duhhig)

“The powers of the mind are like the rays of the sun – when they are concentrated they illumine.” – Swami Vivekananda

Related qualities: concentration, one-pointedness, depth, contemplation, essentialism, meditation, orderliness.

Focus says: “I will ignore distractions, ignore the thousand different trivial things, and put all my energy in the most important thing. I will keep going deeper into what really matters. I can tame my own mind.”

Focus, the ability to control your attention, is the core skill of meditation . It involves bringing your mind, moment after moment, to dwell where you want it to dwell, rather than being pulled by the gravity of all the noise going on inside and outside of you.

Examples: Bringing your mind again and again to your breathing or mantra , during meditation. Cutting down on social media, TV and gossip. Learning to say “no” to 90% of good opportunities, so you can say yes to the 10% of great opportunities. Staying on your chosen path and not chasing the next shiny thing.