Your web browser is outdated and may be insecure

The RCN recommends using an updated browser such as Microsoft Edge or Google Chrome

How to undertake a literature search

Introduction.

Undertaking a literature search can be a daunting prospect. By breaking the exercise down into smaller steps, you can make the process more manageable. The following ten steps will help you complete the task from identifying key concepts to choosing databases for your search and saving your results and search strategy. It discusses each of the steps in a little more detail with examples and suggestions of where to get help.

There are ten steps to undertaking a literature search which we'll take you through below:

🎬 - Indicates a video is available with more information.

Please click on the boxes below to get a bit more detail on each step.

First, write out your title and check that you understand all the terms. Look up the meaning of any you don’t understand. An online dictionary or medical encyclopaedia may help with this.

If your search is for a dissertation, you may need to choose your own research question. In this case, you will need to consider whether there is likely to be enough research on your topic. Alternatively, if your topic is too broad, you could be overwhelmed by the number of references.

One way of checking how much is written on your topic is to use Library Search. Most libraries offer a Library Search or discovery tool. It provides a quick search across all the library’s holdings. You can also limit your search by date or type of document. If you just need a few references to help you write an essay, Library Search may be helpful. It also gives quick access to full text items.

Next, you need to identify your key concepts. One way to do this is to look at your title and identify the most important words. Ignore words that tell you what to do with the information you find eg evaluate, assess, compare, as these are not generally used as search terms. In the example below, key concepts have been highlighted:

Evaluate the effectiveness of a mindfulness intervention on the health-related quality of life of rheumatoid arthritis patients

Another way to do this is to break down your title using the PEO framework:

P = Population E = Exposure O = Outcome

This works well where there is no comparison between two types of treatment or intervention.

In our example:

P = rheumatoid arthritis patients

E = mindfulness

O = health related quality of life

Other question formats are available such as PICO or SPIDER

Tip: Not all search topics will include every element of PICO – some include fewer items.

Once you have identified the key concepts, it’s important to think of any other terms or phrases that might have a very similar meaning. Including such synonyms will make your search as thorough as possible. For example, if your topic is looking for articles on Staff attitudes , you might also use the terms:

- Staff perceptions

- Staff opinions

- Stereotyping

- Labelling

If the database you are using has a list of subject heading s , this may help you to find the most appropriate term for your subject. Some databases provide definitions for terms used in the database and may suggest related terms.

A comprehensive search will usually include both subject headings from databases and terms that you have thought of yourself.

Tip: Often your search term will be a phrase instead of a single word. To carry out phrase searches, use double quotes, for example “problem drinking”.

Once you have chosen your search terms, you need to think about the best databases for your topic. The databases you choose will depend on the search question and the libraries you have access to.

Tip: It’s well worth taking a few minutes to get to know the databases available on the Library webpages and what they cover.

The next step is to combine your search terms in such a way that you only retrieve the more relevant references for your search question. In order to do this you need to build a search strategy . This involves using Boolean operators such as AND , OR and NOT .

AND narrows the results of the search by ensuring that all the search terms are present in the results.

OR broadens the results of the search by ensuring that any of the search terms are present in the results.

NOT limits the results by rejecting a particular search term. Be careful with NOT because it will exclude any results containing that search term regardless of whether other parts of the article might have been of interest.

OR will broaden your number of results while AND will produce fewer results.

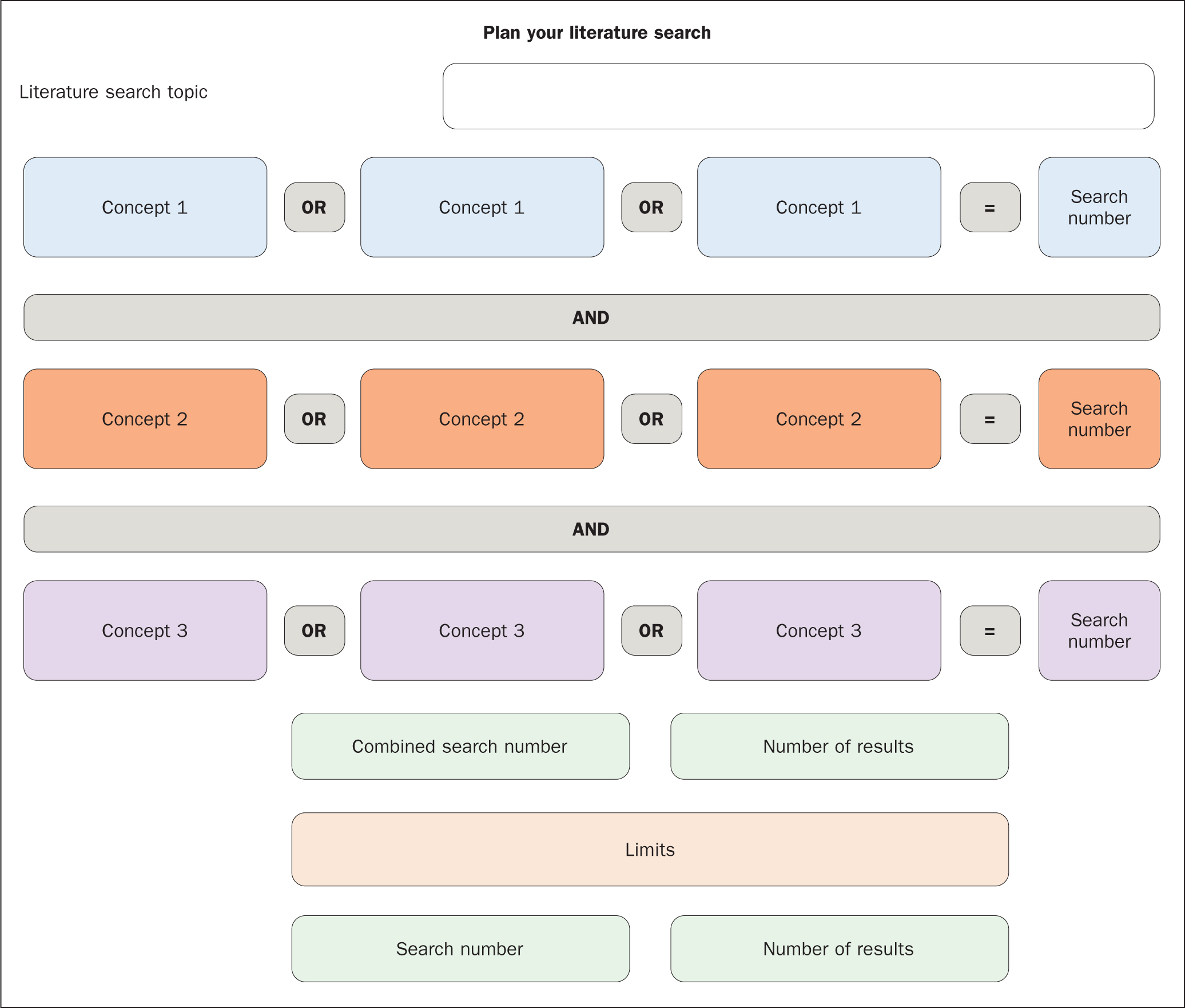

Try using this Search-plan-worksheet to break your topic down into concepts. These can then be linked together when you run the search. You can also add synonyms within each concept box. The yellow limits box is a prompt to think about any limits you want to apply when searching. This leads us to Step 6.

Tip: Most databases will allow you to use a truncation sign (*) or wildcard (?) to pick up various different endings to words or alternative spellings.

For example: alcohol* would pick up alcohol, alcoholic, alcoholism, etc

Sm?th would find Smith and Smyth

The next step is to think about any other restrictions you want to make to your results.

Common limiters found on databases include:

- Peer reviewed articles

- Research articles

- Age group (adult, child, older person)

- Document type

Not all databases allow all of the limiters above.

When writing a dissertation, primary research articles are normally required. Where the database allows you, try limiting to research articles only.

Non-research materials can also be useful as an overview of your topic; for example a literature review can give an analysis of what has already been written on a topic.

The video below includes a demonstration of how limits can be applied using the CINAHL database as an example:

CINAHL - advanced

Once you have identified all your search terms and any limits you want to apply, you are ready to run your search on the databases you have chosen.

Once you have some search results, you can look through them and start to select those that look relevant to your literature search. It is likely you will reject some because they are not quite what you wanted but there will be others that can be marked for further attention.

The title of an article on its own may not tell you very much; read the abstract quite carefully to see if the article is relevant or not.

Tip: You can show more details for each record by clicking on the article title. On some databases, there may be an abstract for the article which you can open.

If you find you are either generating more results than you can possibly look at or too few results to write about, be prepared to adjust your search terms and the way they are combined.

If you get too many results you could try: •limiting to just the most recent material •adding another term or concept and linking it using “AND” •limiting to a particular country or geographical area such as UK

If you get too few results, you might try: •expanding your date range •removing any geographical limits you have applied •removing the least important term or concept

Tip: Be prepared to try other databases and keep searching until you feel confident you have found enough relevant material.

Once you have selected some articles that look relevant for your piece of work, you will need to save them so that your hard work is not wasted.

At the same time, you will want to save your search strategy . This is a record of the terms you searched, how you combined them, any limits you applied and how many results you found.

You will also need to choose a way to save your results. One way is to email the results to yourself and this can be done from all the databases .

Another way is to export your results to reference management software such as Zotero, RefWorks, EndNote or Mendeley. This software allows you to collect, organise and cite research. It is suitable for managing references over a long period of time.

The RCN Library and Museum provides help with using Zotero .

Tip: Keep a record of all the databases you use as you carry out your search. It is also a good idea to note where you found any references you subsequently use for your dissertation.

The final step is to obtain the full text of the articles identified in your search which you believe may be useful for your assignment. If you are lucky, many of these will be available electronically and you may just be able to follow a link to the full text.

Alternatively you can copy and paste your article title into the Library search box and if it is available as full text, a hyperlink will be shown which will link you to the document.

If you are studying elsewhere and have access to a university or hospital library, they may subscribe to different journals to the RCN Library so it is worth exploring what they can offer. If your library does not have either an electronic copy or a physical copy, you may need to request the article by interlibrary loan .

Tip: It is also worth using Google or other browsers to check for the article title you require. Sometimes the article has been made freely available on the internet by the authors.

Boolean operators – words (AND, OR and NOT) which can be used to combine search terms in order to widen or limit the search results.

Database – this is an online collection of citations to journal articles which have been indexed to make retrieval easier. Some databases which also provide full text access to the articles.

Limits – these are options within a database which allow search results to be broken down further. Common limits are year(s) of publication, document type and language. MEDLINE and CINAHL allow age limits too.

Search Strategy – the list of search terms and limits used to retrieve relevant articles from a database in order to answer a search question.

Subject headings – terms that have been assigned to describe a concept that may have many alternative keywords. All these alternative keywords or terms are brought together under the umbrella of this single term. Most health-related databases use subject headings.

Additional information

If after following these steps, you still can’t find what you are looking for, remember that there is always help available at your library. The RCN Library and Museum offers a range of help materials via our Literature searching and training pages . These include: • Databases guides in electronic and printed formats • Video tutorials on how to search the databases • 1-1 training sessions pre-bookable via the RCN website face to face or via zoom

A reading list is also available on dissertation and essay support which provides suggestions for key resources, books and journal articles which may help. Click on the link below to access this list:

Dissertation and essay support reading list

Here are other resources you may also find helpful. You will find links to each resource below too:

- Aveyard H (2019) Doing a literature review in health and social care: a practical guide . 4th edn. London: Open University Press.

- Bettany-Satlikov J (2016) How to do a systematic literature review in nursing: a step-by-step guide . 2nd edn. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Coughlan M and Cronin P (2016) Doing a literature review in nursing, health and social care . 2nd edn. Los Angeles: Sage.

- De Brún C, Pearce-Smith N, Heneghan C, Perera R and Badenoch D (2014) Searching skills toolkit: finding the evidence . 2nd edn. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell / BMJ Books.

- Hewitt-Taylor J (2017) The essential guide to doing a health and social care literature review . London: Routledge.

Critical Appraisal subject guide

Your spaces.

- RCNi Profile

- Steward Portal

- RCN Foundation

- RCN Library

- RCN Starting Out

Work & Venue

- RCNi Nursing Jobs

- Work for the RCN

- RCN Working with us

Further Info

- Manage Cookie Preferences

- Modern slavery statement

- Accessibility

- Press office

Connect with us:

© 2024 Royal College of Nursing

In this Guide

- Access Key Resources

Overview & Steps for Searching the Literature

Step 1: formulate a research question, step 2: identify primary concepts & gather synonyms, step 3: locate medical subject headings mesh (database-specific indexing terms), step 4: combine search terms using boolean operators, step 5: apply search limits or filters, databases to search journal articles, useful websites and handouts, lane classes and tutorials.

- Find Journal Articles

- Drug Info and Calculators

- Patient Information

- Mobile Apps & Research Tools

Literature searching and literature reviews are often used interchangeably but are two different steps in the research process guided by EBM.

- Literature search is searching the literature for some studies. A search strategy is developed for one or more biomedical databases to search the literature, and gather relevant studies.

- Literature review is reviewing the studies which have been identified through a literature search. As part of the literature review, the retrieved articles are analyzed and critically appraised.

The following steps will help guide you through the process of literature searching in PubMed. Though we are focusing on PubMed, these steps can be used across bibliographic databases.

- Formulate a research question

- Identify primary concepts & gather synonyms

- Locate Medical Subject Headings MeSH (database-specific indexing terms)

- Combine search terms using Boolean operators

- Apply search limits or filters

To learn more about the literature searching process, you can explore Lane Library's Literature Searching guide .

The first step in literature searching involves taking a clinical topic or problem and formulating it into a well-defined, answerable question. The development of a clear and focused question will help to streamline the searching process to locate the literature needed to begin answering the question and addressing the clinical problem. A well-defined, answerable question:

- defines the focus of your literature search

- identifies the appropriate study design and methods

- makes searching for evidence simpler and more effective

- helps you identify relevant results and separate relevant results from irrelevant ones

What type of question are you asking?

Therapy: effectiveness/risk of a certain treatment

Diagnosis : accuracy/usefulness of a diagnostic test/tool; application to a specific patient

Prognosis : probable outcome, progression, or survivability of a disease or condition; likelihood of occurrence

Etiology/Harm : cause or risk factors for a disease or condition; questions about the harmful effect of an intervention or exposure on a patient

Tips for formulating a good question:

- The question is directly relevant to the most important health issue for the patient;

- The question is focused and when answered, will help the patient the most;

- The question is phrased to facilitate a targeted literature search for precise answers

Adopted from CEBM: what makes a good clinical question and Center for Evidence Based Medicine: Asking focused questions

PICO Framework

In EBM, following the PICO framework is a common way to create a focused and answerable question from a general topic. PICO is a mnemonic used to describe the four elements of a sound clinical foreground question.

PICO stands for:

- P - Population/Patient/Problem

- I - Intervention

- C - Comparison or Control

- O - Outcome

Alternative formats of PICO include PICOT and PICOTT:

- T - Time

- T - Type of question

- T - Type of study

What is the effectiveness of Prozac vs Zoloft in treating adolescents with depression?

P : adolescents with depression

Using PICO to formulate your research question makes it easier to follow the next step in the literature searching process -- identifying primary concepts & gathering synonyms.

Primary concepts for your research question can be identified using the PICO formula from Step 1. Each of the PICO elements can form a primary concept. If your PICO does not have a C omparison or O utcome, or if the Outcome is broad or vague, it is okay to leave out these concepts. Sometimes, one of the elements in the PICO framework will include more than one primary concept. For example, the Population for our example includes the concept of adolescents and the concept of depression.

P : adolescents with depression

I : Prozac

C : Zoloft

For each primary concept identified, make a list of other terms with the same or related meaning (synonyms). It is important to gather synonyms, because

Terms have different spellings, plural forms, and acronyms

Concepts are described inconsistently across time, geographies, or even among researchers

Terms have the same/close meaning, disciplinary jargon

Umbrella terms vs specific names for issues, interventions, or concepts

These terms will form the keywords of your search strategy.

Tips for finding synonyms:

- Do a quick search to find a relevant article or two. Look at the words used in the article titles and abstracts.

- Think of specific examples or types

- Use background information to help brainstorm (e.g. UpToDate, DynaMed, textbooks)

- Explore the entry terms and related subject headings in MeSH (see Step 3)

Remember that building a search strategy is iterative. As you learn more about your topic, you can add more keywords to your search to broaden your results, or remove keywords if you are finding too many results.

What is Mesh?

Databases like PubMed use subject headings or controlled vocabularies to index (or label) articles. Subject headings are standardized terms for describing what the articles are about. Subject headings are specific to databases, and in PubMed, they are called Medical Subject Headings or MeSH. MeSH terms are structured hierarchically in a tree structure, and when you search a MeSH term, you search automatically includes all the terms that fall beneath it in the tree. Indexers add MeSH terms to journal article records in PubMed to reflect their subject content.

MeSH terms are useful in a search to aid in locating synonyms and reduce term ambiguities. It facilitates the retrieval of relevant articles even when authors use different words or spelling to describe the same concept. For instance, using the MeSH term "Blood Pressure" will also find articles that use "pulse pressure," "diastolic pressure," and "systolic pressure."

Since MeSH terms are organized in hierarchies or MeSH trees, it also facilitates the searching for broad and narrow concepts. For instance, the MeSH term "Domestic Violence" will retrieve articles containing narrower topics such as "child abuse," "elder abuse," and "spouse abuse." But you can also expand the search, and move to a broader level, such as "Violence."

To look up a MeSH term, click on " MeSH Database " on PubMed's homepage. Type your concept into the search bar. The MeSH database will return appropriate MeSH (terms) if there are any. Not every concept will have a matching MeSH term. Remember to search for one concept at a time.

adolescents => "Adolescent"[Mesh]

Prozac => "Fluoxetine"[Mesh]

Zoloft => "Sertraline"[Mesh]

depression => "Depression"[Mesh]

When you search for a MeSH term in PubMed, use the [Mesh] tag following your search term to specify where to search for the term in the PubMed record.

You can also locate MeSH terms in PubMed by finding a relevant article and scrolling to the heading "MeSH terms" at the bottom of the article. This only works for articles that have been indexed.

Other PubMed Search Tags

In addition to searching specifically for MeSH terms, you can also use search tags to search for keywords in particular fields of the PubMed record. When you search in PubMed, you are automatically looking for your keywords in all the record fields. Sometimes this might be too broad and bring back too many search results. You can experiment with field tags like [ti] to look for keywords only in the title or [tiab] to look for keywords only in the title or abstract. Explore all of the available search tags and reach out to your liaison librarian if you have questions using search tags.

Now that you've identified keywords for your concepts (step 2) and related MeSH terms (step 3), you can combine your search terms with Boolean Operators to build your search strategy.

Boolean Operators are a set of commands that can be used in almost every search engine, database, or online catalog to provide more focus to a search. The most basic Boolean commands are AND and OR . In PubMed, you can use Boolean Operators to combine search terms, and narrow or broaden a set of results.

Narrow Results with AND

Use AND in a search to narrow your results. It tells the search engine to return results that contain ALL the search terms in a record.

adolescents AND depression

Note: Both the words adolescents and depression will be present in every record in the results.

Broaden Results with OR

Use OR in a search to broaden your results by connecting similar concepts (synonyms). It tells the search engine to return results that contain ANY of the search terms in a record.

adolescents OR youth OR teenagers

Note: Search results need to have at least one of the words adolescents or youth or teenagers .

Use parentheses ( ) to keep concepts that are alike together, and to tell the database to look for search terms in the parentheses first. It is particularly important when you use the Boolean Operator “OR”.

(adolescents OR youth OR teenagers) AND depression

Tip: You can use" Advanced Search " option in PubMed to help build your search strategy. Search concept by concept, adding ORs between all your keywords and MeSH terms for each concept. After you complete a search for each concept, you can use the "Actions" menu in the Advance Search Search History table to add combine your concept searches with AND. This will look for the overlap between your concept searches and help you avoid nesting errors.

Full Search Strategy Example:

("Adolescent"[Mesh] OR adolescent OR teen OR teens OR teenager OR youth OR youths) AND ("Depression"[Mesh] OR depressive OR depression) AND ("Fluoxetine"[Mesh] OR prozac OR fluoxetin* OR sarafem) AND ("Sertraline"[Mesh] OR zoloft OR sertraline OR altruline OR lustral OR sealdin OR gladem)

You can filter your search results using the PubMed filters in the left sidebar. You can filter by study type to look for the highest level of evidence to answer your question. You can also use date filters or filter to English language materials. If the study type you are looking for is not listed, select "Additional Filters" at the bottom of the left sidebar to see all the available options.

Note: Many PubMed filters depend on indexing, and using filters will exclude articles that do not have indexing.

You can also try PubMed's Clinical Queries to narrow your search results to the type of clinical questions you are asking (Therapy, Diagnosis, etc.).

Getting Too Many Results?

If your search retrieves too many results, you can limit the search results by

- replacing general (e.g. vague or broad) terms with more specific ones

- including additional concepts in your search

- using PubMed's sidebar filters on the left panel of the results page to restrict results by publication date, article type, population, and more

Getting Too Few Results?

If your search returns too few results, you can expand your search by

- browsing the Similar Articles on the abstract page for a citation to see closely related articles generated by PubMed's algorithm

- Removing specific or extraneous terms from the search string

- Using alternative terms to describe a similar concept used in the search

- CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health) Nursing and Allied Health Literature including nursing specialties, speech and language pathology, nutrition, general health, and medicine.

Provides fulltext access to Lane's resources. Contains coverage of over 5000 journals and more than 35.5 million citations for biomedical articles, including, but not limited to, clinical trials, systematic reviews, case reports, and clinical practice guidelines.

- Embase Biomedical and pharmacological abstracting and indexing database of published literature that contains over 32 million records from over 8,500 currently published journals (1947-present) and is noteworthy for its extensive coverage of the international pharmaceutical and alternative/complementary medicine literature.

- Scopus Largest abstract and citation database of peer-reviewed literature featuring scientific journals, books and conference proceedings.

- Web of Science Multidisciplinary coverage of over 10,000 high-impact journals in the sciences, social sciences, and arts and humanities, as well as international proceedings coverage for over 120,000 conferences. Features systematic reviews that summarize the effects of interventions and makes a determination whether the intervention is efficacious or not.

- Joanna Briggs Institute Evidence Based Practice Database Provides evidence-based health information prepared by expert reviewers at Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). It includes several databases: Best Practice Information Sheets, Consumer Information Sheets, Evidence Summaries, Recommended Practices, Systematic Review Protocols, Systematic Reviews, and Technical Reports.

- Cochrane Library Evidence-based collection of information from randomized controlled trials that contain different types of high-quality, independent systematic reviews conducted by the Cochrane Review Groups.

- PsycINFO Provides systematic coverage of the psychological literature from the 1800s to the present through articles, book chapters and dissertations.

- PsycTESTS Provides downloadable access to psychological tests, measures, scales, and other assessments as well as descriptive and administrative information. It includes both published and unpublished tests developed by researchers but not made commercially available.

- ERIC (Education Resources Information Center) Citations and abstracts to journal and report literature in all aspects of educational research. Access Instructions. . . less... Also available through EBSCO and ProQuest

Literature Searching Handouts and Checklist

- Literature searching in PubMed cheat sheet

- Search syntax for common databases cheat sheet

Evidence-Based Research Organizations & Repositories

- Center for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM)

- Cochrane Evidence Essentials

- Joanna Briggs Institute Evidence-Based Practice Resources

- John's Hopkins Nursing Center for Evidence-Based Practice

- Ohio State's Fuld Institute for EBP

- Oncology Nursing Society - Evidence-Based Practice Learning Library

- Sigma Repository It is a profession-based online platform that freely disseminates nursing research, research-related materials, clinical materials related to evidence-based practice and quality improvements, and educational materials.

- NLM PubMed Online Training PubMed training materials by the National Library of Medicine (NLM)

- << Previous: Access Key Resources

- Next: Find Books >>

- Last Updated: Oct 16, 2024 1:02 PM

- URL: https://laneguides.stanford.edu/nursing

Graduate Nursing Resources

- Get Started

- Find Articles

What is a Search Strategy?

How to search an information source, sample search strategy write up.

- Finding the Full-Text

- Conducting a Review of the Literature

- Evidence Based Practice

- Recognizing Scholarly and Refereed Journals

- Synthesizing Sources

- Determining a Theoretical Framework

- Finding a Research Instrument & Evaluating Data

- Citing sources - APA

- Scholary Project - tips

- Care Provider Toolkit

At its most basic, a search strategy is a way of keeping track of where (information sources such as databases, library catalogs, websites, etc.) and what (keywords or search terms) you used to look for sources and research on your topic.

When thinking about how to write up the search strategy for an assignment, including your DNP scholarly project, you will want to keep track of every place that you searched and the exact search terms you used for each source. It is helpful to first think about what constitutes an information sources and then what a search strategy is.

An information source is basically where you search for information. Here are some common examples:

- Journal databases - these are journal and citation indexes that use controlled vocabulary and produce clear repeatable results, examples include MEDLINE, CINAHL, and APA PsycInfo

- Multi-database searching - some sources allow you to search multiple databases at the same time, for example the databases vendors EBSCO and ProQuest allow you to search more than one database at a time

- For example, PubMed and Google Scholar (these seem like databases, but do not have controlled vocabulary or reproducible searches (there is a hidden algorithm that is determining what you see) so for this purpose would not be considered a journal database.)

- Also, journal platforms like Elsevier or Sage only allow you to search one publisher's journals and are not considered a journal database.

- Any websites you searched, for example, government or agency webpages (this is sometimes called the Grey Literature)

- Citation searching - this is when you look at the references of an article you have found, this can be done manual or through Google Scholar. If you have done searching this way, you will want to clearly reference the articles that you mined for citations

- Contacts - did you seek additional studies or data by contacting authors or experts in the field?

- Other methods - anything else you did to find references

A search strategy, is 'how' you searched the information sources, for each information source you will want to report:

- What were the exact keyword and terms you used and how did you combine them? (See box below for more on keywords and Boolean logic)

- How did you add anything to limit your search? (for example additional keywords, or limit by article type or publication type, limit by population)

- Did you add any filters after you searched? (For example, filter to English language or peer review, or certain publication dates)

- Include the date when you performed the search? (When writing up a search strategy you want to include the date you searched, this helps if you (and the reader of your search strategy) come back to see if there is anything new on the topic.)

This information is adapted from the PRISMA-S guidelines for reporting searches and search strategies.

Rethlefsen M. L., Kirtley S., Waffenschmidt S., Ayala A. P., Moher D., Page M.J., Koffel J.B. (2021). PRISMA-S Group. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z

You can always start searching an online source by just putting some keywords in the box to see what results come back, but knowing a little more about how the databases work can help in returning more relevant sources.

Boolean Logic: watch this short video on Boolean operators (e.g. AND; OR or NOT)

- AND means that both words must be present (makes for more narrow results) - Fungi and Cancer

- OR means that either word may be present (makes for broader results and is usually used for synonyms) - Fungi OR Mushrooms

- NOT means that a word will be excluded from the results (makes for more narrow results) - (Fungi OR Mushrooms) NOT Yeast

Parentheses: using parenthesis along with Boolean operators can help the database know what results you want (read the Boolean operators in the correct order).

- This search, Cancer AND Fungi OR Mushrooms, will return articles about cancer and fungi and articles about mushrooms

- This search, Cancer AND (Fungi OR Mushrooms), will return articles about cancer and fungi and articles about cancer and mushrooms

In the EBSCO databases I will usually put synonyms in the same box with an OR and different concepts each in their own box (the boxes effectively work as parentheses in the search:

Truncation symbols: most databases allow the use of * to truncate a word. In searching it will return results for any word that starts with the characters you enter for example: nurs* = nurse, nurses, nursing, and nursery (this can be very helpful if a word has multiple endings, but also note that this last word, nursery, actually has a different meaning than the rest, so sometimes truncating can bring in some irrelevant results.

Search strategy : Searching databases in a consistent, structured manner will save you time. Keeping track of your search history can help you refine your topic, your thinking and your search strategy, and ultimately retrieve more relevant results. After each search, reflect on the keywords and synonyms you used, are there other terms, or another way to combine, to get more relevant results?

Steps in developing a search strategy include:

- define terms and write down your research question - identify, and keep track of key words, terms, and phrases - identify keyword synonyms or reflect on narrower (or broader search terms) - determine a timeframe for search results - consider what type of material you will include and why - identify where you will search for the information

This is just one example (not a template) for how a search strategy might be written up. Note that the searches are clearly reproducible, someone could go to the information sources listed and do exactly the same searches. Additionally, it includes the date the searches were done and the limiters applied in each source.

In August 2021, the databases MEDLINE and Biological Abstracts were searched using the terms: (fungi or mushroom*) AND bioactive compounds. In each database the searches were further limited to English language, published between 2016 and 2021, and peer review articles. This resulted in 869 results in MEDLINE, and 2032 in Biological Abstracts. So I did a more narrow search by adding in the concept of depression, leaving me with seven results in Biological Abstracts and five results in MEDLINE. The resulting 12 articles were then hand reviewed by skimming titles and abstracts, and five applicable articles were selected for inclusion. Additionally, the online source, Google Scholar was searched (in incognito mode) using the terms: depression and mushrooms and "bioactive compounds". From there three additional articles were selected from the first two pages of results. As a final step, two previously selected articles were entered back into Google Scholar and the "cited by" function was used to find additional newer articles (Barros et al. 2007; Elkateeb et al. 2019).

- << Previous: Find Articles

- Next: Finding the Full-Text >>

- Last Updated: Sep 4, 2024 1:50 PM

- URL: https://spu.libguides.com/gradnur

- University of Detroit Mercy

- Health Professions

- Writing a Literature Review

- Find Articles (Databases)

- Evidence Based Nursing

- Searching Tips

- Books / eBooks

- Nursing Theory

- NCLEX-RN Prep

- Adult-Gerontology Clinical Nurse Specialist

- Doctor of Nursing Practice

- NHL and CNL (Clinical Nurse Leader)

- Nurse Anesthesia

- Nursing Education

- Nurse Practitioner (FNP / ENP)

- Undergraduate Nursing - Clinical Reference Library

- General Writing Support

- Creating & Printing Posters

- Statistics: Health / Medical

- Health Measurement Instruments

- Database & Library Help

- Streaming Video

- Anatomy Resources

- Web Resources

- Faculty Publications

- Evaluating Websites

Literature Review Overview

What is a Literature Review? Why Are They Important?

A literature review is important because it presents the "state of the science" or accumulated knowledge on a specific topic. It summarizes, analyzes, and compares the available research, reporting study strengths and weaknesses, results, gaps in the research, conclusions, and authors’ interpretations.

Tips and techniques for conducting a literature review are described more fully in the subsequent boxes:

- Literature review steps

- Strategies for organizing the information for your review

- Literature reviews sections

- In-depth resources to assist in writing a literature review

- Templates to start your review

- Literature review examples

Literature Reviews vs Systematic Reviews

Systematic Reviews are NOT the same as a Literature Review:

Literature Reviews:

- Literature reviews may or may not follow strict systematic methods to find, select, and analyze articles, but rather they selectively and broadly review the literature on a topic

- Research included in a Literature Review can be "cherry-picked" and therefore, can be very subjective

Systematic Reviews:

- Systemic reviews are designed to provide a comprehensive summary of the evidence for a focused research question

- rigorous and strictly structured, using standardized reporting guidelines (e.g. PRISMA, see link below)

- uses exhaustive, systematic searches of all relevant databases

- best practice dictates search strategies are peer reviewed

- uses predetermined study inclusion and exclusion criteria in order to minimize bias

- aims to capture and synthesize all literature (including unpublished research - grey literature) that meet the predefined criteria on a focused topic resulting in high quality evidence

Literature Review Steps

Graphic used with permission: Torres, E. Librarian, Hawai'i Pacific University

1. Choose a topic and define your research question

- Try to choose a topic of interest. You will be working with this subject for several weeks to months.

- Ideas for topics can be found by scanning medical news sources (e.g MedPage Today), journals / magazines, work experiences, interesting patient cases, or family or personal health issues.

- Do a bit of background reading on topic ideas to familiarize yourself with terminology and issues. Note the words and terms that are used.

- Develop a focused research question using PICO(T) or other framework (FINER, SPICE, etc - there are many options) to help guide you.

- Run a few sample database searches to make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow.

- If possible, discuss your topic with your professor.

2. Determine the scope of your review

The scope of your review will be determined by your professor during your program. Check your assignment requirements for parameters for the Literature Review.

- How many studies will you need to include?

- How many years should it cover? (usually 5-7 depending on the professor)

- For the nurses, are you required to limit to nursing literature?

3. Develop a search plan

- Determine which databases to search. This will depend on your topic. If you are not sure, check your program specific library website (Physician Asst / Nursing / Health Services Admin) for recommendations.

- Create an initial search string using the main concepts from your research (PICO, etc) question. Include synonyms and related words connected by Boolean operators

- Contact your librarian for assistance, if needed.

4. Conduct searches and find relevant literature

- Keep notes as you search - tracking keywords and search strings used in each database in order to avoid wasting time duplicating a search that has already been tried

- Read abstracts and write down new terms to search as you find them

- Check MeSH or other subject headings listed in relevant articles for additional search terms

- Scan author provided keywords if available

- Check the references of relevant articles looking for other useful articles (ancestry searching)

- Check articles that have cited your relevant article for more useful articles (descendancy searching). Both PubMed and CINAHL offer Cited By links

- Revise the search to broaden or narrow your topic focus as you peruse the available literature

- Conducting a literature search is a repetitive process. Searches can be revised and re-run multiple times during the process.

- Track the citations for your relevant articles in a software citation manager such as RefWorks, Zotero, or Mendeley

5. Review the literature

- Read the full articles. Do not rely solely on the abstracts. Authors frequently cannot include all results within the confines of an abstract. Exclude articles that do not address your research question.

- While reading, note research findings relevant to your project and summarize. Are the findings conflicting? There are matrices available than can help with organization. See the Organizing Information box below.

- Critique / evaluate the quality of the articles, and record your findings in your matrix or summary table. Tools are available to prompt you what to look for. (See Resources for Appraising a Research Study box on the HSA, Nursing , and PA guides )

- You may need to revise your search and re-run it based on your findings.

6. Organize and synthesize

- Compile the findings and analysis from each resource into a single narrative.

- Using an outline can be helpful. Start broad, addressing the overall findings and then narrow, discussing each resource and how it relates to your question and to the other resources.

- Cite as you write to keep sources organized.

- Write in structured paragraphs using topic sentences and transition words to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

- Don't present one study after another, but rather relate one study's findings to another. Speak to how the studies are connected and how they relate to your work.

Organizing Information

Options to assist in organizing sources and information :

1. Synthesis Matrix

- helps provide overview of the literature

- information from individual sources is entered into a grid to enable writers to discern patterns and themes

- article summary, analysis, or results

- thoughts, reflections, or issues

- each reference gets its own row

- mind maps, concept maps, flowcharts

- at top of page record PICO or research question

- record major concepts / themes from literature

- list concepts that branch out from major concepts underneath - keep going downward hierarchically, until most specific ideas are recorded

- enclose concepts in circles and connect the concept with lines - add brief explanation as needed

3. Summary Table

- information is recorded in a grid to help with recall and sorting information when writing

- allows comparing and contrasting individual studies easily

- purpose of study

- methodology (study population, data collection tool)

Efron, S. E., & Ravid, R. (2019). Writing the literature review : A practical guide . Guilford Press.

Literature Review Sections

- Lit reviews can be part of a larger paper / research study or they can be the focus of the paper

- Lit reviews focus on research studies to provide evidence

- New topics may not have much that has been published

* The sections included may depend on the purpose of the literature review (standalone paper or section within a research paper)

Standalone Literature Review (aka Narrative Review):

- presents your topic or PICO question

- includes the why of the literature review and your goals for the review.

- provides background for your the topic and previews the key points

- Narrative Reviews: tmay not have an explanation of methods.

- include where the search was conducted (which databases) what subject terms or keywords were used, and any limits or filters that were applied and why - this will help others re-create the search

- describe how studies were analyzed for inclusion or exclusion

- review the purpose and answer the research question

- thematically - using recurring themes in the literature

- chronologically - present the development of the topic over time

- methodological - compare and contrast findings based on various methodologies used to research the topic (e.g. qualitative vs quantitative, etc.)

- theoretical - organized content based on various theories

- provide an overview of the main points of each source then synthesize the findings into a coherent summary of the whole

- present common themes among the studies

- compare and contrast the various study results

- interpret the results and address the implications of the findings

- do the results support the original hypothesis or conflict with it

- provide your own analysis and interpretation (eg. discuss the significance of findings; evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the studies, noting any problems)

- discuss common and unusual patterns and offer explanations

- stay away from opinions, personal biases and unsupported recommendations

- summarize the key findings and relate them back to your PICO/research question

- note gaps in the research and suggest areas for further research

- this section should not contain "new" information that had not been previously discussed in one of the sections above

- provide a list of all the studies and other sources used in proper APA 7

Literature Review as Part of a Research Study Manuscript:

- Compares the study with other research and includes how a study fills a gap in the research.

- Focus on the body of the review which includes the synthesized Findings and Discussion

Literature Review Examples

Check out the following articles as examples for formatting a literature review.

- Breastfeeding initiation and support: A literature review of what women value and the impact of early discharge (2017). Women and Birth : Journal of the Australian College of Midwives

- Community-based participatory research to promote healthy diet and nutrition and prevent and control obesity among African-Americans: A literature review (2017). Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities

- Vitamin D deficiency in individuals with a spinal cord injury: A literature review (2017). Spinal Cord

Resources for Writing a Literature Review

These sources have been used in developing this guide.

Resources Used on This Page

Aveyard, H. (2010). Doing a literature review in health and social care : A practical guide . McGraw-Hill Education.

Purdue Online Writing Lab. (n.d.). Writing a literature review . Purdue University. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/conducting_research/writing_a_literature_review.html

Torres, E. (2021, October 21). Nursing - graduate studies research guide: Literature review. Hawai'i Pacific University Libraries. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://hpu.libguides.com/c.php?g=543891&p=3727230

- << Previous: General Writing Support

- Next: Creating & Printing Posters >>

- Last Updated: Oct 24, 2024 1:21 PM

- URL: https://udmercy.libguides.com/nursing

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 19, Issue 1

- Reviewing the literature

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Joanna Smith 1 ,

- Helen Noble 2

- 1 School of Healthcare, University of Leeds , Leeds , UK

- 2 School of Nursing and Midwifery, Queens's University Belfast , Belfast , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Joanna Smith , School of Healthcare, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK; j.e.smith1{at}leeds.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2015-102252

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Implementing evidence into practice requires nurses to identify, critically appraise and synthesise research. This may require a comprehensive literature review: this article aims to outline the approaches and stages required and provides a working example of a published review.

Are there different approaches to undertaking a literature review?

What stages are required to undertake a literature review.

The rationale for the review should be established; consider why the review is important and relevant to patient care/safety or service delivery. For example, Noble et al 's 4 review sought to understand and make recommendations for practice and research in relation to dialysis refusal and withdrawal in patients with end-stage renal disease, an area of care previously poorly described. If appropriate, highlight relevant policies and theoretical perspectives that might guide the review. Once the key issues related to the topic, including the challenges encountered in clinical practice, have been identified formulate a clear question, and/or develop an aim and specific objectives. The type of review undertaken is influenced by the purpose of the review and resources available. However, the stages or methods used to undertake a review are similar across approaches and include:

Formulating clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, for example, patient groups, ages, conditions/treatments, sources of evidence/research designs;

Justifying data bases and years searched, and whether strategies including hand searching of journals, conference proceedings and research not indexed in data bases (grey literature) will be undertaken;

Developing search terms, the PICU (P: patient, problem or population; I: intervention; C: comparison; O: outcome) framework is a useful guide when developing search terms;

Developing search skills (eg, understanding Boolean Operators, in particular the use of AND/OR) and knowledge of how data bases index topics (eg, MeSH headings). Working with a librarian experienced in undertaking health searches is invaluable when developing a search.

Once studies are selected, the quality of the research/evidence requires evaluation. Using a quality appraisal tool, such as the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tools, 5 results in a structured approach to assessing the rigour of studies being reviewed. 3 Approaches to data synthesis for quantitative studies may include a meta-analysis (statistical analysis of data from multiple studies of similar designs that have addressed the same question), or findings can be reported descriptively. 6 Methods applicable for synthesising qualitative studies include meta-ethnography (themes and concepts from different studies are explored and brought together using approaches similar to qualitative data analysis methods), narrative summary, thematic analysis and content analysis. 7 Table 1 outlines the stages undertaken for a published review that summarised research about parents’ experiences of living with a child with a long-term condition. 8

- View inline

An example of rapid evidence assessment review

In summary, the type of literature review depends on the review purpose. For the novice reviewer undertaking a review can be a daunting and complex process; by following the stages outlined and being systematic a robust review is achievable. The importance of literature reviews should not be underestimated—they help summarise and make sense of an increasingly vast body of research promoting best evidence-based practice.

- ↵ Centre for Reviews and Dissemination . Guidance for undertaking reviews in health care . 3rd edn . York : CRD, York University , 2009 .

- ↵ Canadian Best Practices Portal. http://cbpp-pcpe.phac-aspc.gc.ca/interventions/selected-systematic-review-sites / ( accessed 7.8.2015 ).

- Bridges J , et al

- ↵ Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). http://www.casp-uk.net / ( accessed 7.8.2015 ).

- Dixon-Woods M ,

- Shaw R , et al

- Agarwal S ,

- Jones D , et al

- Cheater F ,

Twitter Follow Joanna Smith at @josmith175

Competing interests None declared.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

De Brún C, Pearce-Smith N. Searching skills toolkit: finding the evidence, 2nd edn. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell/BMJ Books; 2014

Hewitt-Taylor J. The essential guide to doing a health and social care literature review.London: Routledge; 2017

Royal College of Nursing. Doing your dissertation subject guide. 2019. https://www.rcn.org.uk/library/subject-guides/doing-your-dissertation (accessed 10 September 2019)

How to undertake a literature search: a step-by-step guide

Mandy Watson

Literature Search Specialist, Library and Archive Service, Royal College of Nursing, London

View articles · Email Mandy

Undertaking a literature search can be a daunting prospect. Breaking the exercise down into smaller steps will make the process more manageable. This article suggests 10 steps that will help readers complete this task, from identifying key concepts to choosing databases for the search and saving the results and search strategy. It discusses each of the steps in a little more detail, with examples and suggestions on where to get help. This structured approach will help readers obtain a more focused set of results and, ultimately, save time and effort.

The first time you undertake a literature search, whether for an assignment, a dissertation, an interview or to help you care for a patient, the task can appear a little daunting. The key is to break the process down into smaller steps and think carefully about each step in advance.

There are 10 steps in the search process:

Think about your search question

Identify your key concepts, think about alternative search terms or synonyms, choose the most appropriate databases to search, combine your search terms.

- Consider any limits that you want to apply

Run your search and review your results

- Adapt your search strategy, if necessary

Save your results and search strategy

- Obtain your materials.

First, write out your title and check that you understand all the terms. Look up the meaning of any you do not understand. An online dictionary or medical encyclopaedia may help with this. If your search is for a dissertation, you may need to choose your own research question. In this case, you will need to consider whether there is likely to be enough research on your topic. On the other hand, if your topic is too broad, you may be overwhelmed by the number of references and will need to make your topic more specific.

Next, you need to identify your key concepts. One way to do this is to look at your title and identify the most important words. Ignore words that tell you what to do with the information you find (such as evaluate, assess, compare), because these are not generally used as search terms. In the example below, key concepts have been highlighted:

Evaluate the effectiveness of a mindfulness intervention on the health-related quality of life of rheumatoid arthritis patients .

Another way to do this is to break down your title using the PEO framework:

- P = population

- E = exposure

- O = outcome.

This works well where there is no comparison between two types of treatment or intervention.

In our example:

- P = rheumatoid arthritis patients

- E = mindfulness

- O = health-related quality of life.

Other question formats are available, such as PICOS (Population/problem/phenomenon, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study design) or SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type) ( Hewitt-Taylor, 2017 ).

Once you have identified the key concepts, it is important to think of any other terms or phrases that might have a very similar meaning. Including such synonyms will make your search as thorough as possible. For example, if your topic is looking for articles on staff attitudes, you might also use the terms ‘staff perceptions’ or ‘staff opinions’. A really thorough search might look for ‘stereotyping’ or ‘labelling’ as well. At this stage you should also consider whether your chosen terms have alternative spellings, eg anaemia and anemia, and make sure you include both. Most databases will allow you to use a truncation sign (usually *) or wildcard (usually ?) to pick up various different endings to words or alternative spellings. For example, alcohol* would pick up alcohol, alcoholic, alcoholism, etc. Sm?th would find Smith and Smyth.

If the database you are using has a list of subject headings, this may help you to find the most appropriate term for your subject. The database may provide a note defining how terms are used in the database and may even suggest related terms.

Some databases, such as CINAHL and MEDLINE, also allow you to select a term as a major heading, ensuring that the article is substantially about that subject.

A comprehensive search, however, will usually include both subject headings from databases and terms that you have thought of yourself.

Box 1 provides some useful basic terminology.

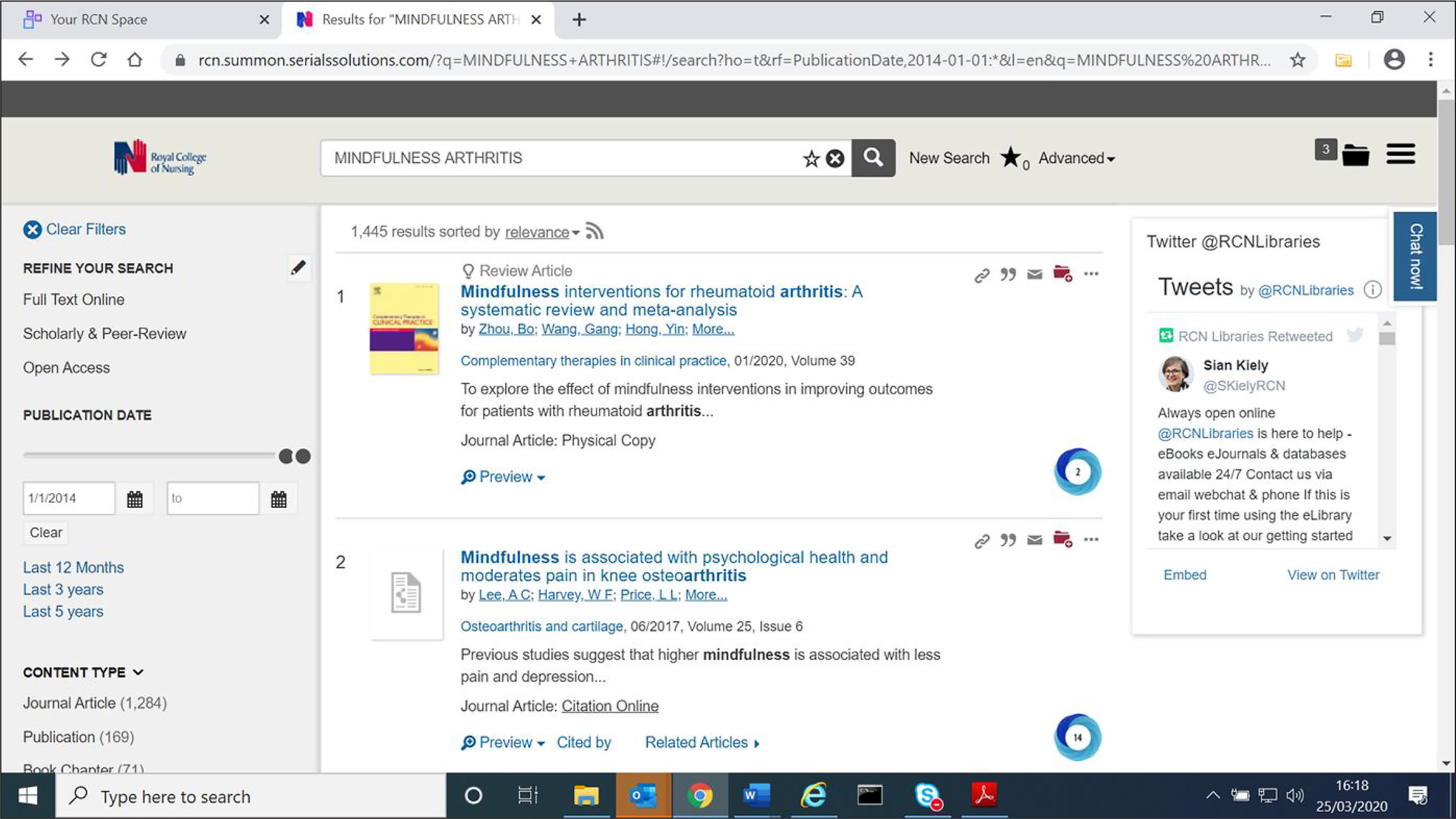

Once you have chosen your search terms, you need to think about the best databases for your topic. The databases you choose will depend on the search question and the libraries to which you have access. If you just need a few references to help you write an essay, most libraries offer a library search (see Figure 1 ) or discovery tool. This generally allows a quick search across all the library's holdings and should allow you to limit your search by date or type of document. It can also give quick access to full-text items. The drawback of a library search is that it does not allow complicated search strategies in the way that some other databases do.

If your search is for a more in-depth assignment such as a dissertation, you will need to look at other databases. The Royal College of Nursing (RCN) Library and Archive Service (LAS) offers our members access to CINAHL, British Nursing Index and MEDLINE. These databases are useful for nursing topics, but several more specific databases are also provided such as Maternity and Infant Care, AMED for alternative and complementary medicine and Social Policy and Practice.

To access a range of databases, you may need to visit more than one library. Although the RCN specialises in nursing-related materials, your hospital library or university library may offer a broader range of databases in other fields of practice.

The next step is to combine your search terms in such a way that you retrieve only the more relevant references for your search question. In order to do this you need to build a search strategy. This involves using Boolean operators such as AND, OR and NOT.

- AND narrows the results of the search by ensuring that all the search terms are present in the results

- OR broadens the results of the search by ensuring that any of the search terms are present in the results

- NOT limits the results by rejecting a particular search term. Be careful with NOT because it will exclude any results containing that search term regardless of whether other parts of the article might have been of interest.

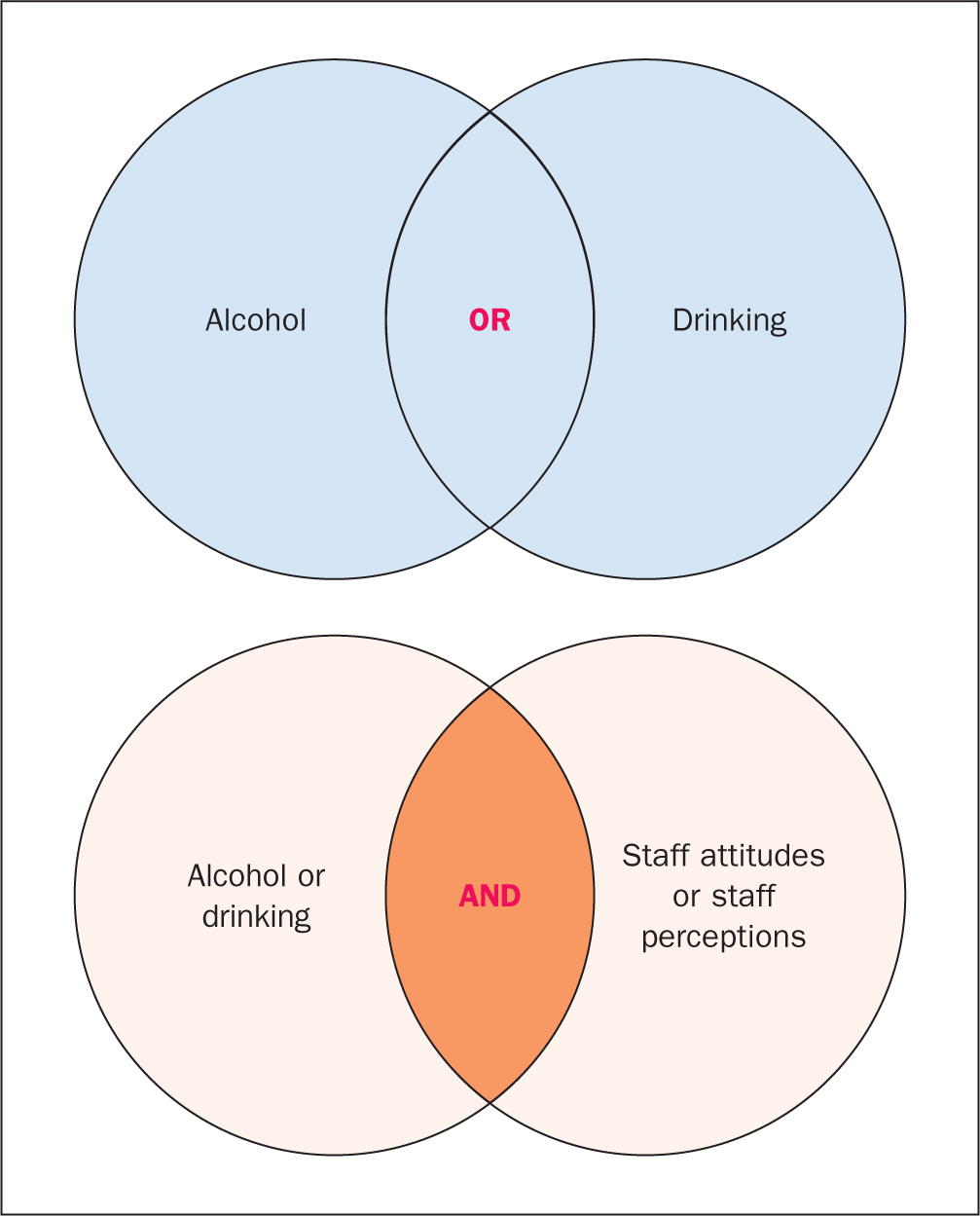

When you start to combine your search terms, it is important to link synonyms or alternative spellings with ‘OR’. For example, ‘staff attitudes’ OR ‘staff perceptions’. Concepts, on the other hand, should be linked with ‘AND’. For example, ‘alcohol’ OR ‘drinking’ AND ‘staff attitudes’ OR ‘staff perceptions’. This is sometimes called Boolean logic.

In Figure 2 , you can see that OR includes the contents of both circles, while AND includes only the contents of the area where the two circles overlap (the darker orange shaded area). From this diagram it is clear that OR will broaden the number of results, while AND will produce far fewer results.

Most databases will offer an Advanced Search option and this will allow you to build a complicated search with different concepts on different lines. In this way, you can group your synonyms into concepts (using OR) and then combine the different concepts together (using AND).

Figure 3 shows a template we use at the RCN Library to help with planning your search strategy. This can be used to break your topic down into concepts. These can then be linked together when you run the search. You can also add synonyms within each concept box. The ‘limits’ box is a prompt to think about any limits you want to make when searching.

Consider any limits you want to apply

The next step is to think about any other restrictions you want to make to your results. You may want to limit your search results to a certain time period. The most recently published will normally be most relevant. You may also want to specify that they should come from peer-reviewed journals.

On some databases (such as CINAHL), other limits are available, such as age group (adult, child) or document type. When writing a dissertation, primary research articles are normally required so it is worth checking whether the database allows you to limit to research articles only.

It might be worth looking at non-research materials too because a general article might provide a useful overview of your topic. A literature review can give an analysis of what has already been written on the topic.

Once you have identified all your search terms and any limits you want to apply, you are ready to run your search on the databases you have chosen, making sure that you include all your key words. Then you can look at the search results and start to select those that look relevant to your literature search. It is likely you will reject some because they are not quite what you wanted, but there will be others that can be marked for further attention.

The title of an article on its own may not tell you very much; read the abstract quite carefully to see whether or not the article is relevant. An abstract is a brief summary of an article or piece of writing on a particular subject and is often used to help the reader quickly understand the article's purpose. At this stage, try not to get sidetracked if you come across an article that is interesting but doesn't really answer your search question.

Adapt your search strategy as necessary

If you find that you are either generating more results than you can possibly look at or too few results to write about, be prepared to adjust your search terms and the way they are combined. If you get too many results, you could try:

- Limiting to just the most recent material

- Using more specific terms or adding another term and linking it using ‘AND’

- Limiting to a particular country or geographical area. If you get too few results, you might try:

- Expanding your date range

- Removing any geographical limits you have applied

- Removing the least important term or concept.

Also, be prepared to try other databases and keep searching until you feel confident that you have found enough relevant material.

Once you have run your search, and selected some useful references from the results that you want to follow up, it is important to save your search strategy. This is a record of the terms you searched, how you combined them and how many results you found for each. You can usually include your search strategy when emailing or saving your references.

You will also need to choose a way to save your results. One way is to email the results to yourself. A better way may be to use one of the reference management packages available, such as EndNote, Mendeley or Zotero to save the results. Such software has several advantages:

- It allows you to save your references into a file that you can add to as you extend your search to other resources

- You can manipulate the references to suit your purpose and delete any duplicates

- You can easily change the referencing style to suit the demands of the organisation or publication for which you are writing.

Keep a record of all the databases that you use as you carry out your search. It is also a good idea to note where you found any references that you subsequently use for your essay, dissertation or journal article.

Obtain your materials

The final step is to obtain the full text of the articles identified in your search that you consider may be useful for your assignment. If you are lucky, many of these will be available electronically and you may just be able to follow a link to the full text. Many libraries now offer a Library Search option like the one mentioned in Step 4. You can copy and paste your article title into the Library Search box and, if it is available as full text, a hyperlink will be shown that will link you to the document.

If the article is only available as a physical copy in your library, you will need the full citation details provided in the search results to access the article. This will include the journal title, volume and issue numbers and page numbers.

If your library does not have either an electronic copy or a physical copy, you may need to request the article by interlibrary loan. There is usually a charge for this service. You can ask your librarian for more details. It is also worth using Google or other search engines to check for the article title you require. Sometimes the article has been made freely available online by the authors or is available through PLOS One, a peer-reviewed open access scientific journal that covers primary research from any discipline within the fields of science and medicine.

Getting help

If, after following these steps, you still cannot find what you are looking for, remember that there is always help available at your library. The RCN Library and Archives Service offers a range of help materials ( https://www.rcn.org.uk/library/support/literature-searching-and-training). These include:

- Database guides in electronic and printed formats

- Video tutorials on how to search the databases

- One-to-one training sessions pre-bookable via the RCN website, face to face or via Skype.

A subject guide is also available on doing your dissertation and provides suggestions for key resources, books and journal articles that may help ( RCN, 2019 ).

A search service (where a literature search is carried out on your behalf by a librarian) may also be available at hospital/NHS trust libraries and some other specialist libraries, but these services are generally available only to qualified healthcare staff.

Breaking your search down into a series of smaller steps will help you to think carefully about your search topic and how to achieve the best results. This article has discussed the 10 steps involved in undertaking a literature search in detail. Taking a structured approach to searching will ultimately save time and effort. As a result you will obtain a more focused set of results that can be used as the basis for a successful assignment.

- Undertaking a literature search is an essential step of the research process and will be valuable when preparing for assignments, interviews and providing clinical care

- Careful planning of your search strategy (key concepts, search terms, synonyms, databases used and limits) will make your searching far more efficient

- Remember to save your search results and search strategy as you go along. Then you will be able to explain how you achieved your results

- Taking a structured step-by-step approach will save you time and effort and provide you with a more focused set of search results

CPD reflective questions

- Consider the different search question frameworks in Step 2. Can you apply one of these to a literature search topic you are researching?

- Using the concepts you have identified from your search topic, write out your search terms and consider any synonyms or alternative spellings that you might also include

- Think about any limits you would apply to your results, such as time frame, geographical, or restricting to primary research only

- Become Involved |

- Give to the Library |

- Staff Directory |

- UNF Library

- Brooks College of Health

Search Strategy

- Nursing Databases

- PICO(T) from Nutrition

- Systematic Reviews

- Tools to Manage the Systematic Review Process

- Conducting a Literature Review This link opens in a new window

Search Strategy: A search strategy is an organized structure of key terms used to search a database. PICO(T) is part of your search strategy. The search strategy combines the key concepts of your search questions in order to retrieve accurate results. NYU LibGuide provides students with a thorough overview of the Search Strategy. This LibGuide includes Boolean worksheets.

Researchers use Boolean Logic to combine search terms.

Most databases allow the use of AND, OR and NOT to broaden or narrow and search.

- AND will narrow the search to include only records with both terms.

- OR with broaden the search to include records with either term.

- NOT will narrow the search to exclude records with one of the terms.

Truncation: You can use an * at the end of a word stem to broaden your search to include related terms . For example, to search for child, children or childhood use the search term child *

Putting quotes "" around words allows you to search for a phrase. For example, searching language development, without quotes, finds records with both the word 'language' and 'development' somewhere in the record. Searching "language development", with quotes, only find records with the phrase "language development".

Here is a sample search that uses the quotation marks to keep the words overweight and adults next to one another; hence only articles with those terms side-by-side will show up in the result list. Furthermore, this search will only pull up articles with the terms dietary and supplements next to one another.

Limiters: Use limiters to hone in on topics. Health/Nursing databases provide many limiters. CINAHL's limiters enables you to limit by peer-reviewed, geography, age, sex, human study, evidence based practice, etc.

The PICO(T) question is the catalyst to your research:

1. PICOT Question:

How effective is the consumption of low glycemic index foods for reducing energy intake and promoting weight loss in adults?

Subject Searching

Subject searching is a more precise way to search, particularly when your search term can have more than one meaning. Every item in a database is assigned specific subject headings using a controlled vocabulary, which can vary by database. Most medical databases use MeSH (Medical Subject Headings), which is continually updated by the National Library of Medicine. MeSH uses a hierarchical system that allows for easy broadening or narrowing of topics. CINAHL uses subject headings unique to the database that use the same structure.

MESH Subject Headings -

MeSH is the National Library of Medicine's controlled vocabulary thesaurus. It consists of sets of terms naming descriptors in a hierarchical structure that permits searching at various levels of specificity.

MeSH descriptors are arranged in both an alphabetic and a hierarchical structure. At the most general level of the hierarchical structure are very broad headings such as "Anatomy" or "Mental Disorders." More specific headings are found at more narrow levels of the thirteen-level hierarchy, such as "Ankle" and "Conduct Disorder." There are over 28,000 descriptors in MeSH with over 90,000 entry terms that assist in finding the most appropriate MeSH Heading, for example, "Vitamin C" is an entry term to "Ascorbic Acid." In addition to these headings, there are more than 240,000 Supplementary Concept Records (SCRs) within a separate file. Generally SCR records contain specific examples of chemicals, diseases, and drug protocols. They are updated more frequently than descriptors. Each SCR is assigned to a related descriptor via the Heading Map (HM) field. The HM is used to rapidly identify the most specific descriptor class and include it in the citation.

CINAHL Subject Headings -

The CINAHL subject headings are based on the MeSH headings, with additional specific nursing and allied health headings added as appropriate. Each year, the headings are updated and revised relative to terminology needed in these fields. In addition, new terms from MeSH may be added as well.

Watch: Use MeSH to Build a Better PubMed Query

Credits: National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)

Your instructor will often request that you track your search terms. Many databases offer a "Search History" option.

You can also save your searches within CINAHL and PubMed. In CINAHL, you have the option to create a My EBSCOhost folder; In PubMed you can save your searches within a NCBI account. Other databases offer similar options.

- << Previous: PICO(T) from Nutrition

- Next: Systematic Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Oct 14, 2024 2:56 PM

- URL: https://libguides.unf.edu/nursing

How to conduct an effective literature search

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Nursing and Midwifery, Trinity College Dublin. [email protected]

- PMID: 16320963

- DOI: 10.7748/ns2005.11.20.11.41.c4010

The ability to describe and analyse published literature on a topic and develop discussion and argument is central to evidence-based patient care. A literature review is an assessment procedure that is commonly applied in nursing settings. Effective literature searching is a crucial stage in the process of writing a literature review, the significance of which is often overlooked. Although many current textbooks refer to the subject, information is often of insufficient depth to guide an effective search. This article outlines important considerations in the search strategy and recommends practical advice for students to ensure best use of their valuable time. It is suggested that a systematic, organised search of the literature, that uses available resources effectively, is more likely to produce quality work.

- Abstracting and Indexing

- Databases, Bibliographic*

- Documentation

- Information Storage and Retrieval*

- Nursing Research*

- Bodleian Libraries

- Oxford LibGuides

- Systematic Reviews and Evidence Syntheses

- Searching for studies

Systematic Reviews and Evidence Syntheses: Searching for studies

- Planning a Review

- Help and training

In conducting a search for a systematic review, scoping review or other evidence synthesis review, your aim is to conduct a sensitive and comprehensive search. For a systematic review, particularly if you’re going to make clinical decisions, it is important not to miss relevant studies as this could have an impact on the data analysis and subsequent recommendations. Chapter 4: Searching and Selecting Studies in the Cochrane Handbook is an invaluable source of advice and guidance on the conduct of searches for systematic reviews.

If you’re conducting a rapid review, you may need to make compromises with the breadth of the search and the number of databases searched. In this case. It would be important to highlight the potential limitations of the approach when presenting your findings.

If you need any help or advice on the issues discussed in this section, please consult your outreach or subject librarian for further guidance.

Developing your search strategy: Selecting the key search concepts

In planning your review, you will have broken down your topic using a question formulation tool e.g. PICO or PCC. In preparing your search strategy you will look again at the PICO and select which key concepts will be included in the search, and which will be used as inclusion / exclusion criteria at the title/abstract or full text screening stage. For a sensitive search, it’s common practice to select 2 (sometimes 3) elements of the PICO for searching, often the Population and Intervention elements. For example, for this PICO:

How do delayed antibiotic prescriptions for respiratory infections affect patient & service outcomes compared to immediate /no prescription?

Population = Patients with respiratory infections

Intervention = Delayed antibiotic prescription

Comparison = Immediate or no prescription

Outcomes = time to recovery, repeat GP appointment, emergency hospitalisation, patient satisfaction...

The key elements for starting your search would be respiratory infections, antibiotics and delayed prescribing. For this question, we have multiple comparators and multiple outcomes, if we added keywords for these concepts, we might overlook significant synonyms and miss relevant papers. By focusing on the population and intervention we will automatically retrieve papers reporting any or no comparator and any outcomes, primary or secondary.

Developing your search strategy: Brainstorming keywords