Building a Joyful Classroom Community

In a year full of uncertainty and stress, teachers in the early grades can create a safe and even joyful learning environment.

Your content has been saved!

As teachers, we are experiencing anxiety, disruptions, and uncertainty because of the lingering pandemic. However, happiness can still happen behind our closed classroom doors. This year, I’ve worked hard to make my classroom a happy place for my students, who come to class looking for some sense of normalcy in an otherwise chaotic world.

I ask myself the following questions: What are my students’ favorite activities? What draws the most engagement in the classroom? What can I do to make these occurrences more frequent?

These are the places I have seen joy emerge, and providing more opportunities for this to happen helps me keep going and stay focused on the essential part of my job this year—creating a safe environment where students can find joy in learning even in challenging times.

Build a Strong Community

Being a part of a powerful community allows students to see school as a safe, caring environment and provides support as together we navigate the unknown.

To give an example, I start the day by placing materials such as Legos, drawing paper, and books on tables for my students to choose from as they arrive, allowing them to talk casually and connect with their peers. Then, at our morning meeting, we form a circle and I ask them, “How are you feeling?”

The kids and I sit in silence for a moment, waiting for each other to respond. “I’m overwhelmed,” “I’m exhausted,” “I’m scared,” “I’m very happy to be here,” “I enjoy going to school,” and “I’m feeling all mixed up inside” are among my students’ responses. Sometimes we share some fabulous (or not-so-fabulous) news.

We reassemble for quiet time in the middle of the day. I turn on soft lights as we do a guided meditation to help us refocus and center ourselves. While the kids rest, draw, or read, soft music plays. This sets the tone for a calm afternoon.

We turn on a dance song and sing along to our favorite songs during transitions throughout the day and to add fun to our routine as we clean up the room.

We reassemble in our circle before school ends for the day. I ask each child to describe the day in one word, whether it be a feeling, an accomplishment, or a favorite activity.

These moments unite us as a happy community that looks out for each other, laughs together, takes deep breaths, and reflects on what we are doing together as a class.

Engage in Authentic Curriculum

For years, I’ve taught my students about animal adaptations by comparing various types of bears, which is a popular animal among them. On one of our outdoor learning days this year, my students stumbled upon a porcupine den in the woods behind our school. It piqued their interest, which showed up in their drawings, block constructions, and story writing.

“Everyone acknowledges that curriculum becomes intriguing, alive, and compelling when something out of the blue captures the imagination of a group of children,” David Sobel wrote in his book Childhood and Nature . Their newfound interest inspired me to change course.

In this year’s science unit, we are studying the adaptations of our local porcupine family. To learn more, we brought in a local naturalist. She brought in a real porcupine skull for the kids to see, quills for them to feel, stories about porcupines in the wild, and books to help us all learn more.

We brainstormed important questions the children had using the Question Formulation Technique , which we will use to guide our research. We used online resources to find more books and videos to aid us in our research and nonfiction writing . As a final project, each child will write a chapter book explaining the animal’s survival adaptations.

As a culminating project, we will collaborate with the art teacher to create an artistic representation of the den on a bulletin board, to which the children add information gleaned from the experience. The project keeps growing, and the excitement builds with each new idea that emerges. We invite parents to take part in our class project by posting updates on our classroom blog for them to follow.

This all started with the kids and their excitement because of a discovery we made as a class. Focusing on activities that encourage children’s happiness, curiosity, and engagement—or even making the tiniest change in the curriculum to a topic that matches their interests—can sometimes pave the way for happiness.

Share Student Voices

In these times of uncertainty, we all need a place to be seen and heard. This happens in my class during Writer’s Workshop. Every day, children find a quiet corner of the room to write in, where they create stories about things that matter to them. They write about everything, then draw colorful pictures to go along with their words.

Then comes the most exciting part. Returning to the rug, the children discuss their work with a friend. They enjoy getting together to read aloud to one another. During sharing time, the room is quiet, but the laughter is loud as they read their stories.

We form a circle and project a few stories onto the document camera so that the entire class can see and discuss them. The author then walks to the “Author’s Chair” to receive questions, comments, and compliments on their story from their peers.

One of my students recently wrote a story about how happy she was to receive her Covid shot. “I jumped up and down because I love my covid shot. I got it at school. When it happened, I wasn’t crying. My dad was so proud!” she wrote. She recalled the night we converted our school gymnasium into a vaccination center, with children and parents waiting in long lines for hours to get their shots.

When we get together as writers, we can share these experiences and support one another through the various emotions they bring out in us.

“The happiness of the child is one test of the correctness of educational procedure,” Maria Montessori once said. So, right now, do more of the things that make your students happy.

We all need more of that.

- Understanding Mental Health

- Suicide Prevention

- Body and Mind

- Depression +

- Developmental disorders

- Other disorders

- Adolescence

- Workplace Mental Health

- Legal Matters

Seven strategies for a happy classroom

School-going children spend a greater part of their day in classrooms, and for teaching and learning to be truly effective, it is important that classrooms are safe, happy and welcoming spaces. Here are nine strategies that can help teachers create a positive classroom experience.

The ‘Whale Done’ response

Teachers often wait for perfect work or behavior to praise a child. Sometimes it may never happen by the teacher’s standard of perfection. Instead, what if one praises the little steps the child is making to reach the goal?

Taken from the book titled Whale Done by Ken Blanchard, the 'Whale Done' response empowers one to build positive relationships – teacher and pupils, parents and children or in fact any relationship. A beautiful line in the book says ‘Praise progress, it’s a moving target’. Here is the 'Whale Done' response:

Praise students immediately, i.e. as soon as the behaviour occurs.

Be specific about what they did right or almost right.

Share your positive feelings about what they did.

Encourage them to keep up the good work.

The 'redirection' response

This response needs conscious practice before it becomes a part of a teacher’s behavior.

Describe the error or problem as soon as possible, clearly and without blame.

Explain its negative impact.

If appropriate, take the responsibility for not making the task clear (For instance, ‘I am sorry, I did not communicate the instructions clearly').

Go over the task in detail and make sure it is clearly understood.

Express your continuing trust and confidence in the student.

Ask yourself

When teachers embark on a teaching career, they need to answer some questions for themselves in order to be the kind of teacher they aspire to be. For instance, questions such as:

What kind of values and attitudes do I need, to develop the right kind of values and attitudes in my students?

What kind of skills would I require, to develop key life skills such as managing emotions and problem solving in my students?

How will I maintain a balance between academic performance and emotional wellbeing of my students?

Twenty or thirty years from now how will I want my students to remember me?

Answers to these questions will help teachers gain better insight on how they can excel in their chosen vocation.

Set healthy boundaries

Children need boundary lines within which they can operate and this applies to both classroom and home settings. It reminds me of a child who ran away from the house, and when found by the police, he explained, "I do not want to go home, my home lacks discipline." What the child meant was that there was no one who cared enough about him to give him the boundaries – the limits. Children need to feel secure and cared for and boundary lines help achieve this.

In the classroom, boundaries can be established in different ways. For example, in the lower classes, the teacher—with a little help from the students—can make a 'traffic light' for the class. The red light rules will be common for adults and children. For instance, "We will not use our hands to hit anyone." The amber light rules will be different for teachers and children. For example, "When at work you will not walk around in the class and disturb the others." The green light rules are the areas where children have freedom. For instance, the teacher could give them freedom to create a story, or an art piece or ask questions and share ideas and opinions.

In middle school and high school the students can be involved in the making of class agreements (for example, "We agree to be on time.") and the consequences.

Focus on the process

Teachers normally focus on the results or the outcome, and while this matters, the method or process is equally important. A seven-year-old child once said to her parents, "Going to school is like hurting a bird whose wings are not hurt." What the child meant was that learning was not fun as she had to do it the teacher’s way and there was no place for her way.

Children are happy when they can experience, explore, observe, communicate – in other words, when they are fully engaged in the process of learning. It is also important to remember that children learn differently.

Know as much as you can about the kids rather than make them pass through the same eye of the needle.

Howard Gardner

Avoid scapegoating

In every school and possibly in every classroom there are scapegoats. The scapegoat is the student who:

is caught and blamed for all misbehavior in the class/school.

is manipulated and not aware that they are being manipulated.

is generally slower in covering up and therefore the misbehavior is much more visible. The manipulators stand aside and watch the fun.

has no plausible excuse for their behavior except to say that someone else started it (The excuse is not believed by the teacher).

In such situations, teachers should be observant and listen with all their antennae out. Have a meeting with all the concerned students to understand the issue. Do not act as an umpire – instead ask everyone involved questions that will help put the issue in the right perspective. Refrain from being judgmental.

Dr Thomas Gordon in his book Teacher Effectiveness Training, brings out the concept of 'teacher-owned' problems and 'student-owned' problems. Teachers should learn to identify the problems that they 'own'. Does the behavior of the child affect your feelings and interfere with your needs? For example, is your own success tied to your student’s behavior and performance? If yes, then you as the teacher own the problem. You now have three choices before you:

Change the student: If the child’s behavior is a problem, then suggesting to the parents that they withdraw the child from school is definitely not the solution. A better way, would be to convey to the child, how the behavior makes you feel, without threatening or ridiculing them. Use the ‘I’ message, for instance, "I feel angry when you act the clown in class and disturb my flow of thought." This will bring in honesty and transparency into the teacher-student relationship. In the long run it will foster a rapport. A little affection and love shown can bring about a miraculous change in the behavior of a child. If the problem is ‘student owned’, help the child take ownership of the problem and face the consequences of the disruptive behavior. Above all, build a partnership with parents. Use the diary – not only as a “complaint book” but also as a means to communicate positive messages about the child to the parents.

Change the environment: Wherever possible think of changing the environment creatively. Generally, the education system tends to make everybody like everybody else. This could be one of the causes for misbehavior as the same fit does not fit all. Every teacher and every student is unique and therefore the system should be dynamic, constantly evolving and changing.

Change yourself: Let me share a thought that I picked up from a book titled Living, Loving and Learning by Leo F Buscaglia, PhD. He asks, "Should you be a loving teacher or a loving human being?" He goes on to say that children identify with people, with human beings. They have great difficulty identifying with a teacher for most of the time the teacher is playing a role. We have to be more than a loving teacher.

As a closing thought, let us also learn from the younger generation. They are our best teachers in that, through their behavior they are giving us messages on how they want to be treated. As a teacher, ask yourself whether you model being an enthusiastic learner. Look at the quality of your teaching and the preparation that goes into your teaching. Teachers who are knowledgeable, have the right attitudes, are organized, behave confidently, and have things under their control, are less likely to face aggression or disruption. The teacher with the greatest openness to the thoughts of others can, and generally will control the outcome of any interaction. Students do perceive the teacher’s efforts. Respect earned and commanded is the greatest antidote to disruptive behavior.

Phyllis Farias is a Bangalore-based Education Management Consultant. Over the years, she has taught at all levels – from primary school to teachers' training in college. In addition, she has conducted workshops, seminars and training programs in schools, colleges and professional institutions throughout the country.

We are a not-for-profit organization that relies on donations to deliver knowledge solutions in mental health. We urge you to donate to White Swan Foundation. Your donation, however small, will enable us to further enhance the richness of our portal and serve many more people. Please click here to support us.

How To Create A Happy Classroom

Author biography.

Adrian Bethune

Is your classroom a happy place?

Happiness in schools is becoming a serious business as heads and teachers try to tackle both a young people’s mental health crisis and a teaching crisis too.

The evidence is clear that happier children work better, get ill less, have less time off school, get higher grades and are generally more successful. And, if you think focusing on student happiness detracts from ‘serious’ learning, think again. The evidence also shows that schools that work on developing student wellbeing not only have happier pupils but that they do better academically and their behaviour improves too.

10 Steps To A Happy Place

Here are 10 ways to foster happy classrooms to maximise learning and teach your students some life-affirming skills.

1 Tribal classrooms

Humans are an innately tribal and social species. We operate the best and learn the most when we feel safe, secure and connected to others. So, greet your students at the door with a smile and shake their hand. Make everyone feel welcome and that they’re part of your tribe. When there are friendship issues, help to resolve them. A happy classroom is built primarily on positive relationships.

2 Mindfulness

There’s growing evidence that mindfulness interventions can help children reduce their levels of stress, anxiety and depression, whilst increasing their levels of positive emotion, attention and even metacognition. Create moments of stillness in your day when your class pause, take some deep breaths, and then focus on their normal breathing. Each time their mind wanders away from their breathing, guide them to gently bring their attention back to the breath. Every time you bring your attention back to the breath after it has wandered, you strengthen the parts of the brain in charge of attention and emotional regulation.

Click To Tweet

3 Rewire negativity bias

The human brain has an innate negativity bias. This helped keep us alive on the savannah as our ancestors who could spot dangers quickly and avoid them, survived and passed on their genes, but our more mindful ancestors who stopped to admire a beautiful vista were gobbled up by a lion. But a practice known as ‘Three Good Things’ can help rewire that bias and level the playing field. At the end of each day, get your students to write down three things that went well for them. Ask them to share their good things with a partner. Repeat often to rewire that bias!

Learning new things is a key facet of a happy life. When we’re engaged and interested in our work, we feel and do better. But if the work is not challenging enough, we get bored, and too challenging and we get overwhelmed. Aim for that elusive Goldilocks sweet-spot of stretching your students to just beyond what they can currently do as that is where neuroplasticity is maximised and the most learning takes place.

When the challenge of a task is just right, when the task has clear goals, and when we’re able to really focus on what it is we’re doing, we are likely to experience ‘flow’ – an optimal state of psychological being. Time rushes by, we lose sense of ourselves and it feels deeply satisfying. Children that experience flow more regularly show deeper learning, greater long-term interest in subjects, and higher levels of wellbeing. Create the atmosphere so your class can lose themselves in their work!

6 Play to their strengths

Character strengths are the core parts of ourselves that shape our personality and motivate us. Studies show that when we use our strengths in novel ways we are significantly happier. Why not get your class to take this youth strengths questionnaire to identify their top ‘signature strengths’ and task them with using them in their school work and at home.

7 Practice kindness

Humans are hardwired to be kind. We get more happiness from buying a gift for others, than we do for ourselves. Kindness is contagious too and it even helps make us healthier. The best way to spread it is to be kind yourself. Teachers who use kind words, are polite, respectful, patient and well-mannered have children who emulate them. You could even encourage your children to carry out random acts of kindness by hosting a ‘Kindness Week’ .

8 Be optimistic

Optimists are happier, have better health and are less likely to suffer from depression than their pessimistic counterparts. But how can you help students be optimistic when things aren’t going there way? A key is to let them know that the problem is temporary (it won’t last forever), that it is specific (it affects one area of their life but other areas are going well) and it isn’t personal (don’t blame yourself as other external factors would have been involved). Help them challenge their negative self-chatter and see their situation from a more hopeful perspective.

Exercise is one of the single biggest things we can do to boost our physical and mental health. Fitter students perform better academically, have better body-image and higher self-esteem. We need to be getting our students out of their chairs and moving more. You could get your class to do ‘The Daily Mile’ where they jog or run a mile every day. Or simply break up lessons with a round of star jumps, burpees, or a few laps of the playground. Short bursts of exercise raises the heart rate and sends more blood and oxygen up to the brain allowing it to think better. Feel good hormones like dopamine and endorphins that exercise releases not only boost happiness levels but they are neurotransmitters too, so they boost brain power!

10 Walk the talk

To create a happier classroom for your children, you must first work on yourself. If you don’t walk the talk, your message will feel inauthentic and your class won’t buy into it. So make sure you look after yourself and practice what you preach. Ultimately, a happy teacher makes a happy classroom. Have a great year fellow teachers!

Adrian Bethune’s new book Wellbeing In The Primary Classroom: A Practical Guide To Teaching Happiness is out now and includes many more practical tips for creating a happy classroom. Keep an eye on Teacher Toolkit social media this week because we’ll be giving away a free copy to one lucky winner!

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

7 thoughts on “ How To Create A Happy Classroom ”

Hi Adrian, I’d like to add on – Taking Action To Resolve Bullying in Classrooms. I’ve seen instances where teachers simply ignore students bullying others in the believe that “it’s a phase and will go away”. I’d say that as teachers in charge of a classroom the onus is absolutely on us to address these situations either through mediation, escalation to parents, or in extreme cases some sort of disciplinary action or a combination of the above. The teacher has to do what is necessary to create a safe environment for all students (including the bully!).

Hi there, I agree with you. Bullying behaviour does need to be dealt with swiftly and effectively. From experience, creating tribal classrooms where all children feel valued and part of a team and school community, as well as working on fostering kindness are very effective at promoting prosocial behaviour and reducing incidents of bullying.

Thanks for your comments. I agree. Incidents of bullying must be handled quickly and effectively. From experience, creating tribal classrooms where all children feel valued and part of a team, and are encouraged to look after one another, plus working on developing kindness, all goes to help Foster prosocial behaviour and reduce the incidents of bullying behaviour.

Adrian, really enjoyed your blog laced with elements of our Mentors in Motion and Mental Health Footprint programmes that The Children’s Foundation is delivering across North East England.

Hi Tony, thanks for your comments. Your work sounds really interesting. I’ll be in touch!

Thanks Adrian

Very engaging article. Reading about (happiness) makes the reader happy, too, just like what you’ve stated in your post that positivity is contagious. And it has to start with the leader in the classroom- the teacher. Then again, positivity has to be coupled by strength so that no one gets gobbled up by the lion. When students are in an optimistic and uncluttered frame of mind, they will be most receptive to learning. It is particularly essential to allow mindfulness to flow in the classroom so that teaching and learning becomes more effective.

Good article. Helps in managing s happy class.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Our partners

Privacy overview.

What Is Positive Education, and How Can We Apply It? (+PDF)

They want their children to be happy and to flourish. They want them to live out their dreams and reach their innate potential.

The challenge, however, is finding the right education model. One that doesn’t stifle their potential nor produce cookie-cutter pupils.

An excellent option to consider is positive education, which combines traditional education principles with research-backed ways of increasing happiness and wellbeing.

The fundamental goal of positive education is to promote flourishing or positive mental health within the school community.

Norrish, Williams, O’Connor, & Robinson, 2013

Continue exploring this article to learn more about the emerging field of positive education and how it is transforming lives around the world.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Education Exercises for free . These ready-made tools are perfect for enhancing your teaching approach, making it easier to engage students in meaningful, student-centered learning.

This Article Contains:

What is positive education, how to apply positive education, positive education in practice, restorative practices, further positive education research, limitations in research, where are we now, 11 positive education books for parents and teachers, 4 videos on positive education, 4 positive education resources, 3 worksheets for positive educators, a take-home message.

Positive education is the combination of traditional education principles with the study of happiness and wellbeing, using Martin Seligman’ s PERMA model and the Values in Action (VIA) classification .

Seligman, one of the founders of positive psychology, has incorporated positive psychology into education models as a way to decrease depression in younger people and enhance their wellbeing and happiness. By using his PERMA model (or its extension, the PERMAH framework) in schools, educators and practitioners aim to promote positive mental health among students and teachers.

The PERMA and PERMAH frameworks

PERMA encompasses five main elements that Seligman premised as critical for long-term wellbeing:

- Positive emotions : Feeling positive emotions such as joy, gratitude, interest, and hope

- Engagement: Being fully absorbed in activities that use your skills but still challenge you

- (Positive) relationships : Having positive relationships

- Meaning : Belonging to and serving something you believe is bigger than yourself

- Accomplishment : Pursuing success, winning, achievement, and mastery

The PERMAH framework adds Health onto this, covering aspects such as sleep, exercise, and diet as part of a robust positive education program (Norrish & Seligman, 2015).

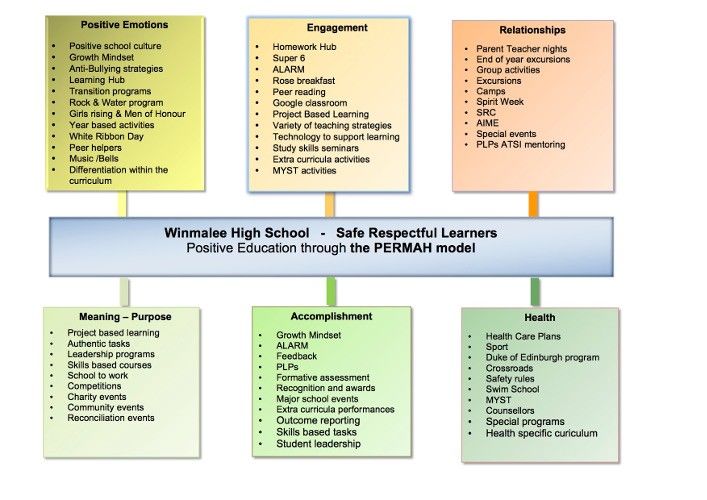

PERMAH in practice

The figure below is provided by Winmalee High School (2020) in New South Wales, and it shows how the PERMAH framework has been applied in practice through elements such as project-based learning, anti-bullying strategies, and more.

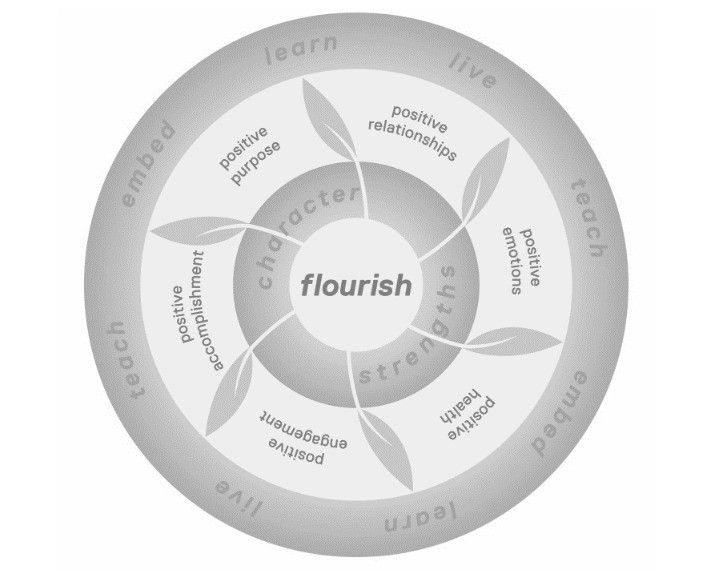

Below, you’ll find another example from Geelong Grammar School, one of the earliest models in the field (Norrish et al., 2013).

Source: Norrish et al., 2013, in Hoare, Bott, & Robinson, 2017, p. 59

VIA Character Strengths

Education has long focused on academics and fostering positive character strength development. However, before the publication of Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification by Peterson and Seligman (2004), any efforts to endorse character strengths were derived from religious, cultural, or political bias (Linkins, Niemiec, Gillham, & Mayerson, 2015).

The VIA classification, however, provides a cross-culturally relevant framework for ‘educating the heart’ (Linkins et al., 2015, p. 65).

Positive education programs usually define positive character using the core character strengths that are represented in the VIA’s six virtues:

- Wisdom and knowledge

- Transcendence

These positive characters aren’t innate; they’re external constructs that need to be nurtured. The goal of positive education is to reveal children’s combination of character strengths and to develop their ability to effectively engage those strengths (Linkins et al., 2015).

VIA strengths in practice

In practice, integrating character strengths into curricula can involve collecting information on students’ VIA strengths, talents, and interests when they enroll.

Revisiting these and communicating them to students throughout their academic journey can also be excellent ways to validate and nurture strengths (Robinson, 2019).

Self-report measures such as the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths for Youth may be useful (Park & Peterson, 2006).

VIA Strengths: Positive Education With Character Strengths

Strengths-based interventions in educational systems are powerful tools that are often surprisingly simple to introduce.

“A school curriculum that incorporates wellbeing will ideally prevent depression, increase life satisfaction, encourage social responsibility, promote creativity, foster learning, and even enhance academic achievement”

(Waters, 2014).

The Geelong Grammar School (GGS) in Australia has often been cited as a model for positive education, since it was one of the first schools to apply positive psychology approaches school wide (Norrish & Seligman, 2015).

At GGS, all teachers and support staff participate in training programs to learn about positive education and how to apply its teachings in both their work and personal lives (Norrish & Seligman, 2015).

For students at the school, positive education is incorporated into every course. For example, in an art class, students might explore the concept of flourishing by creating a visual representation of the concept. The students also have regular lessons on positive psychology, just like they would with subjects like mathematics and geography (Norrish & Seligman, 2015).

These strengths-based interventions also focus on the relationship between teachers and students. When a teacher gives feedback, they are instructed to be specific about the strength the student demonstrated rather than giving vague feedback like “Good job!”

Changes to these small interactions are significant, and paying attention to the wording of positive reinforcement can make a difference. A study of praise conducted by Elizabeth Hurlock (1925) found it a more effective classroom motivator than punishment regardless of age, gender, or ability.

The following video summarizes the innovative ways schools are incorporating positive education into their curriculum.

Euro News: The Art of Happiness Through Positive Education – Learning World

In Australia, one school focuses on wellbeing, under the belief that humans learn best when they are happy. The video above explains the application of positive psychology into the school system at GGS.

Here are just a sample of some ways to incorporate this model into any classroom or school system.

The jigsaw classroom

The jigsaw classroom is a technique in which students are split into groups based on shared skills and competencies. Each student is assigned a different topic and told to find students from other groups who were given the same topic. The result is that each group has a set of students with different strengths, collaborating to research the same topic.

The influence of positive psychology has even extended to classroom dynamics. In positive psychology-influenced curricula, more power is given to the students in choosing their curriculum, and students are given responsibility from a much younger age. In these types of classroom settings, students are treated differently when it comes to praise and discipline.

The character growth card

In Paul Tough’s (2013) book How Children Succeed , he argues that possessing inborn intelligence and academic competency is not enough for students to succeed in school. Instead, he argues that grit, resilience, and other character traits should receive a greater emphasis in schools. Doing so leads to better near-term academic performance in students.

The acclaimed charter school network KIPP took many of these ideas and made them an official part of school protocol. Students at KIPP schools receive a Character Growth Card, which evaluates students’ performance not just for academic subjects like math and history, but also regarding a series of seven character traits. These traits are culled from positive psychology research by Seligman and psychologist Chris Peterson.

KIPP’s system enables the formal assessment of traits that fall outside the metrics used to assess students at most schools, and it teaches the importance of these character traits in a few ways. Teachers model positive behavior, call out positive examples of the character traits in action, and discuss the traits openly and explicitly.

There are no formal lessons teaching character traits like zest or gratitude. Still, KIPP faculty believe that highlighting examples of these traits when they naturally occur is an effective way to encourage their development.

Not everyone seems to believe that KIPP’s method is effective. In an article in The New Republic , education professor Jeffrey Snyder (2014) argues that we don’t actually know how to teach character strengths, so numerically measuring them can do more harm than good.

Even critics of KIPP agree that calling attention to character and positive psychology in schools is a step in the right direction.

The Bounce Back program and building resilience

Researchers Toni Noble and Helen McGrath (2008) devised a practical, cost-effective, and efficient classroom resiliency program called Bounce Back , the first positive education program in the world.

Noble and McGrath (2008) argue that teaching resilience to young children is most useful for lasting change, but that the most pressing need for increased resilience is during students’ transition into secondary school.

The Bounce Back program is targeted to upper primary and lower secondary students, as adolescence is a critical period of change and stress for students. This concept is summarized by their video below:

Resilience: Bounce Back

Bounce Back addresses two key areas: the environmental factors that build up psychological capital and the personal coping skills that students can learn, the importance of which has been highlighted by many researchers such as Reivich and Shatté (2002), and Barbara Fredrickson (2001).

Noble and McGrath (2008) provided a series of practical, day-to-day school activities that helped students feel connected to their peers, school, and the community. Their research showed how schools could create a more supportive environment, both within the school and in students’ families and communities.

To help students develop coping skills, the Bounce Back curriculum provides resources and suggestions for teachers and exercises for pupils. The exercises are designed to encourage pupils to develop optimism in the classroom and grow an accepting and light-hearted attitude.

Bounce Back provides practical tools such as a responsibility pie chart, which guides children to realize that all negative situations are a combination of three factors: their own behavior, the behavior of others, and random events.

Using the responsibility pie chart to understand a specific negative event helps pupils learn what they can change and what they can’t, developing their senses of initiative and responsibility.

These principles have proven useful for other positive psychology client groups. Participants in Possibility Place, a program for boosting resilience and confidence in the long-term unemployed, found the responsibility pie chart very useful in preventing people from berating themselves for things that were not their fault and learning to understand what they could do to resolve the situation.

Bounce Back is a wonderful example of how positive psychology research can be transmuted into tools to help people flourish.

More case studies

As positive education grows in popularity across the world, there are increasingly more global cases of its implementation at the system level. Some great examples include the following (Seligman & Adler, 2018).

Israel’s Maytiv Positive Education Program starts in pre-school and stretches up to the high school level. While positive psychologists still call for cautious interpretation of extant data, the Maytiv Program has shown some promising results such as enhanced student self-efficacy, positive emotions, a feeling of school belongingness, and improvements in the quantity and quality of social peer ties (Shoshani & Steinmetz, 2014; Shoshani, Steinmetz, & Kanat-Maymon, 2016; Shoshani & Slone, 2017).

Dubai’s Knowledge and Human Development Authority partnered with the South Australian Department of Education to conduct the Dubai Student Wellbeing Census. Following this, some schools in the United Arab Emirates have been established on positive education principles, including rigorous training of all educators and the introduction of dedicated departments such as one school’s “wellbeing department.”

In Mexico, a partnership between the Jalisco Ministry of Education and University of Pennsylvania also resulted in randomized controlled studies at educational institutions, with promising results. Based on these outcomes, a wellbeing curriculum (Currículum de Bienestar) was developed and implemented with beneficial impacts on measures such as academic performance, student connectedness, perseverance, and engagement (Adler, 2016).

In any given school year, tens of thousands of students are expelled from U.S. public schools. In the 2015–2016 academic year, for example, over 11 million instructional days were lost, according to the ACLU (Washburn, 2018).

Many of these students will be forced to leave their school for an entire academic year, while others will be barred from ever attending a public school in their state.

Considering how many days of school and learning are lost to expulsions and suspensions, some school administrators are starting to rethink those methods. Expulsions and suspensions can sometimes be necessary if a student’s behavior is compromising the safety or learning environment of their fellow students.

Many educators now think these disciplinary measures are unlikely to help children learn from their mistakes or prevent repeat behavior once the offending students are back in school. Some argue that these punishments further alienate these children physically and emotionally from their peers, only making them more likely to repeat harmful behavior (Noble & McGrath, 2008).

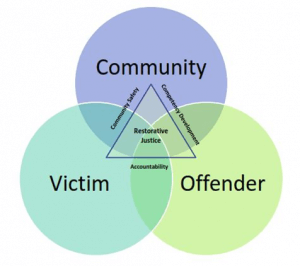

Source: Inequalitygaps.org

An alternative method, called restorative practice, is championed by some as an improvement upon the expulsion and suspension model (McCluskey et al., 2008). Restorative practice isn’t an entirely new concept; it’s based on the restorative justice model that has been championed by criminal justice reform advocates for years.

In this model, a meeting is held between the person who “offended” someone, the person directly affected by the offender, and the community entangled in this domino effect of actions. The Venn diagram above offers a visual as to how these parties intersect.

If a school disciplines a student, it’s usually because the student’s behavior had a specific effect on their environment. The idea behind restorative practice is to focus on that effect when pursuing disciplinary action.

Let’s take a look at an example.

Let’s say Maria was talking too loudly during class, disrupting her peers’ ability to focus. In a traditional disciplinary setting, the teacher might ask Maria to stop talking or give her a time-out.

In restorative practice, the teacher would ask Maria why she was speaking out of turn, what effect she’s having on the students around her, and whether she thinks it’s fair for the other students to be on the receiving end of that behavior.

In a more extreme case, like a student provoking and participating in a fight, the restorative practice would be more formal. The child would participate in a meeting with other students and adult leaders in the school. Together, they would discuss what spurred the student to start the fight, how it affected the others involved, and what the student might do instead if they were in a similar situation in the future (Hendry, 2010).

The student might also be assigned activities or programs that would help prevent further fights. As discussed in an article on restorative practice in EducationWeek , a California middle-schooler named Danny went through a similar process. In Danny’s case, his disciplinary requirements included “writing letters of apology, undergoing tutoring, and joining a school sports team.”

While precise recidivism rates vary based on location, the data on restorative practices shows promising results.

The New Low-Effort, High-Impact Wellbeing Program.

Wellbeing X© is a seven-session, science-based training template. It contains everything you need to position yourself as a wellbeing expert and deliver a scalable, high-impact program to help others develop sustainable wellbeing.

“A central question of youth development is how to get adolescents’ fires lit, how to have them develop the complex of dispositions and skills needed to take charge of their lives”

(Larson, 2000).

Lots of studies have been done on positive education and its potential impacts. Here are some summaries of research findings on the benefits of positive education.

Promoting human development

Clonan, Chafouleas, McDougal, and Riley-Tillman (2004) found that the incorporation of positive psychology in learning environments helped foster individual strengths. It encouraged the development of positive institutions and made students more successful.

Still more research confirms these results, including studies establishing that positive education interventions had a more lasting impact on changing student behavior than other methods (Adler, 2016).

Teaching students how to make themselves happy

In another study, researchers examined the effects of life coaching on high school students (Green, Grant, & Rynsaardt, 2007).

The results showed that following their life coaching sessions, students showed significant decreases in depression and increases in cognitive hardiness and hope (Green et al., 2007). Students are better equipped to improve their subjective wellbeing in the longer term through greater control over their positive emotional experiences (Fredrickson, 2001; 2011).

Decreasing depression

Positive psychology interventions that are used in positive education include identifying and developing strengths, cultivating gratitude, and visualizing best possible selves (Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005; Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2006; Liau, Neihart, Teo, & Lo, 2016).

A meta-analysis conducted by Sin and Lyubomirsky (2009) with 4,266 participants found that positive psychology interventions do significantly increase happiness and decrease depressive symptoms. Further evidence from randomized clinical trials indicates a similar impact from positive psychology interventions in children (Kwok, Gu, & Kit, 2016).

Facilitating academic performance

Among some of the great examples of positive education’s impact on academic performance, we recommend Angela Duckworth’s work on grit, and Shankland and Rosset’s (2017) study on the positive relationship between learner wellbeing and academic performance (Duckworth, Peterson, Matthews, & Kelly, 2007; Villavicencio & Bernardo, 2016; Akos & Kretchmar, 2017; Mason, 2018).

Offering easier systems for teachers

Positive education benefits teachers, too. It creates a school culture that is caring and trusting and prevents problem behavior. Recent research suggests that better teacher–student relationships may benefit student academic performance as well (Košir & Tement, 2014).

Increasing motivation among students

Positive education also offers a fresh model of pedagogy that emphasizes personalized motivation in education to promote learning (Seligman, Ernst, Gillham, Reivich, & Linkins, 2009).

Research has shown that goals associated positively with optimism resulted in highly motivated students (Fadlelmula, 2010). This study showed that motivation may be consistent and long term if it is always paired with positive psychology interventions.

Boosting resilience

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania developed the Penn Resiliency Program . Results from 19 controlled studies of the Penn Resiliency Program found that students in the program were more optimistic, resilient, and hopeful. Their scores on standardized tests increased by 11%, and they had less anxiety approaching exams (Brunwasser, Gillham, & Kim, 2009).

Where many earlier studies on positive psychology focused primarily on adults such as college students, we’re now welcoming research on students as young as pre-schoolers.

There will always be calls for more research, so what’s next, specifically?

Seligman and Adler (2018) suggest the following in a publication on positive education:

- More evidence on the reality of the wellbeing improvements and academic achievement data we’ve seen thus far

- Rigorous cost-benefit analyses on existing positive education programs, which consider effect sizes and duration of reported results

- More scientific rigor in general across the field, including cross-validating measures, less obtrusive and reactive measures, and more big data techniques

- Treatment fidelity measurement, assessing how closely educators are adhering to the manuals they are provided in positive education systems

Overall, research findings on positive education have been promising so far, and time will tell what the future holds for positive education. Interest in applying positive psychology interventions in schools is certainly growing rapidly.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

In the time since Seligman established the basic tenets of positive psychology, it has been implemented worldwide in many ways. While the objective of giving students the tools to build meaningful relationships, feel good, become well rounded, and bring positivity to everything that they do is common among all positive education institutions, each has its own approach.

For example, Perth College trains its staff in positive psychology and coaching and has full lesson units on ethical issues and social justice.

Other schools utilize the Montessori method, which emphasizes student-led, project-based curricula to enhance creativity and hands-on learning.

With the success of many of these approaches and no single dominant method, many organizations are starting to grow in an attempt to consolidate and organize the efforts among different schools.

The International Positive Education Network is one of several institutions attempting to figure out what is working and spread it through means such as conferences and even policy reform.

Recent research has suggested that these sorts of initiatives lead to students growing up with higher levels of creativity, leadership skills, and emotional intelligence (Leventhal et al., 2015). Furthermore, they even lead to improved academic performance and significantly better mental health (Adler, 2016).

With high levels of anxiety and depression in the world today, proactively raising children to handle these problems effectively may be the best antidote we can provide.

Are you interested in reading about how other institutions have embraced positive education or discovering some tactical approaches for teaching strengths? Here is a list of recommended books on topics in positive education.

- Positive Education: The Geelong Grammar School Journey ( Amazon ) – by J. Norrish

- Building Positive Behavior Support Systems in Schools: Functional Behavioral Assessment ( Amazon ) – by D. Crone, L. Hawken, and R. Horner

- Teaching That Changes Lives: 12 Mindset Tools for Igniting the Love of Learning ( Amazon ) – by M. Adams

- Positive Academic Leadership: How to Stop Putting Out Fires and Start Making a Difference ( Amazon ) – by J. Buller

- Playful Learning: Develop Your Child’s Sense of Joy and Wonder ( Amazon ) – by M. Bruehl

- Activities for Teaching Positive Psychology: A Guide for Instructors ( Amazon ) – by J. Froh and A. Parks

- Building Resilience in Children and Teens: Giving Kids Roots and Wings ( Amazon ) – by K. Ginsburg

- Making Wellbeing Practical: An Effective Guide to Helping Schools Thrive ( Amazon ) – by L. McKenna

- Positive Psychology in Practice: Promoting Human Flourishing in Work, Health, Education, and Everyday Life ( Amazon ) – by S. Joseph

- Celebrating Strengths: Building Strengths-Based Schools ( Amazon ) – by J. Eades

- Reshaping School Culture: Implementing a Strengths-Based Approach in Schools ( Amazon ) – by E. Rawana, K. Brownlee, M. Probizanski, H. Harris, and D. Baxter

If you want to learn more about positive education, try watching these videos on the subject. We would also love to hear any additional ideas in our comments section.

1. What Is Positive Education?

This video gives a very brief introduction to positive education and the role it can have on a student’s wellbeing. It also delves into the specific positive psychology techniques used in positive education.

2. Positive Education: Overcoming Disadvantage

How do positive education instructors teach and observe students differently from traditional teachers?

The video shows teachers reflecting on the program, discussing the benefits of “talking back,” focusing on what’s right with children and teenagers, and rebuilding a school’s culture.

3. Positive Education: Teaching Wellbeing

Geelong Grammar School, as described above, is taking an innovative approach in their students’ wellbeing.

This video explains how the school helps students cope with the stressors of life and gives a glimpse of what goes on in a positive education classroom. What makes this video remarkable is it shows how self-aware the students are.

4. Positive Education at Perth College, Anglican School for Girls

At Perth College, skills of wellbeing are taught to girls as a core part of their educational program. “ It’s important to start at a really young age, ” the school director explains.

This video focuses on a school that has wholly implemented positive education into their school program. It outlines how educators incorporate positive education for every age group, how they help their students flourish, and the results it has had on the staff, too.

If you’re interested in learning more about positive education, be sure to check out the following sources.

1. Institute of Positive Education | The Geelong Grammar School

As described above, the faculty at Geelong Grammar School believes that wellbeing should be at the heart of education. The school is known for pioneering a whole-school approach to positive education.

Here, you’ll find a positive education podcast, a curriculum to browse, and classroom materials such as the Mindful Moments and Brain Breaks .

2. International Positive Education Network (IPEN)

IPEN is a network that aims to bring individuals and institutions together to promote positive education.

On the IPEN website , educators can access learning materials such as meditations, vocabulary, video introductions to concepts, and inspiration for lesson plans. IPEN also has an active community of positive educators so users can connect and collaborate.

3. Positive Education Schools Association (PESA)

PESA is a school association working to embed positive psychology into school programs and aiming to improve student wellbeing and academic performance. This association helps schools and teachers gain access to resources and the latest research.

The association’s vision is for an education system that integrates wellbeing science and positive psychology. To this end, PESA facilitates collaboration between positive educators, provides resources, and hosts events.

4. Positive Schools Initiative

The Positive Schools Initiative website links to Australian and Asian conferences for educators, as well as the free digital Positive Times magazine . Here, parents and teachers can find news articles and opinion pieces on topics such as creativity, intrinsic motivation, engagement, goals, and other key positive education themes.

The Initiative is based on the contextual wellbeing model , which aims to create positive schools by supporting four interlinked domains: people, social norms, policy and practice, and physical space.

1. My Favorite Animals

Use this worksheet to help students identify positive qualities in their favorite animals, and acknowledge how those strengths can be seen in themselves as well.

Students are invited to reflect on qualities in their favorite animal that represents how they want others to see them. For example, flamingo – elegant, graceful, etc. Next, they select another animal, and list how others may see them. For example, an owl – quiet, shy etc. Lastly, they select yet another animal and identify who they truly are. For example, a monkey – funny, friendly, etc.

Here is the My Favorite Animals worksheet.

2. Daily Mood Tracker

The Daily Mood Tracker enables students to keep a record of their emotional state throughout the day. It’s simple to use and facilitates a better understanding of their moods while promoting emotional awareness through self-reflection.

Download this free Daily Mood Tracker .

3. Using Traits and Talents to Build Resilience

This fun exercise can be used to motivate students to take a more active approach in dealing with challenging events. By understanding their own gifts – traits and talents – they build their self-esteem, vital to being resilient. For example, dealing with peer problems, a student can find the strength to cope by living in line with their strengths, such as being kind or inventive.

The My Gifts – Traits and Talents activity involves four steps, and is a great tool to remind students of their great qualities.

Top 17 Exercises for Positive Education

Use these 17 Positive Education Exercises [PDF] to enhance student engagement, resilience, and wellbeing while also equipping students with valuable life skills.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

To encourage positive education in more schools, researchers argue that more practitioners should share their knowledge and experiences. Can you recommend any books, strategies, institutions, or resources to your fellow educators? Do you have a case study from your personal experience?

Or perhaps you’re a researcher who is studying the field – in that case, what’s brand new? What would you like to see more of in positive education curricula?

Let us know; we’d like to hear from you. Share your insights below in our comments section.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Education Exercises for free .

- Adams, M. (2013). Teaching that changes lives: 12 Mindset tools for igniting the love of learning. Berrett-Koehler.

- Adler, A. (2016). Teaching wellbeing increases academic performance: Evidence from Bhutan, Mexico, and Peru (Doctoral dissertation). University of Pennsylvania. Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations, 1572.

- Akos, P., & Kretchmar, J. (2017). Investigating grit at a non-cognitive predictor of college success. The Review of Higher Education, 40 (2), 163–186.

- Bruehl, M. (2011). Playful learning: Develop your child’s sense of joy and wonder. Roost Books.

- Brunwasser, S. M., Gillham, J. E., & Kim, E. S. (2009). A meta-analytic review of the Penn Resiliency Program’s effect on depressive symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77 (6), 1042–1054.

- Buller, J. L. (2013). Positive academic leadership: How to stop putting out fires and start making a difference. Jossey-Bass.

- Clonan, S. M., Chafouleas, S. M., McDougal, J. L., & Riley-Tillman, T. C. (2004). Positive psychology goes to school: Are we there yet? Psychology in the Schools , 41 (1), 101–110.

- Crone, D. A., Hawken, L. S., & Horner, R. H. (2015). Building positive behavior support systems in schools: Functional behavioral assessment (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92 (6), 1087–1101.

- Eades, J. M. F. (2008). Celebrating strengths: Building strengths-based schools. CAPP Press.

- EducationWeek. (2012, October 16). ‘Restorative practices’: Discipline but different. Retrieved May 21, 2021, from https://www.edweek.org/leadership/restorative-practices-discipline-but-different/2012/10

- Fadlelmula, F. K. (2010). Educational motivation and students’ achievement goal orientations. Procedia–Social and Behavioral Sciences , 2 (2), 859–863.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56 (3), 218–226.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2011). Positivity . Crown.

- Froh, J. J., & Parks, A. C. (Eds.). (2012). Activities for teaching positive psychology: A guide for instructors. American Psychological Association.

- Ginsburg, K. R. (2014). Building resilience in children and teens: Giving kids roots and wings. American Academy of Pediatrics.

- Green, S., Grant, A. M., & Rynsaardt, J. (2007). Evidence-based life coaching for senior high school students: Building hardiness and hope. International Coaching Psychology Review , 2 (1), 24–32.

- Hendry, R. (2010). Building and restoring respectful relationships in schools: A guide to using restorative practice. Routledge.

- Hoare, E., Bott, D., & Robinson, J. (2017). Learn it, live it, teach it, embed it: Implementing a whole school approach to foster positive mental health and wellbeing through positive education. International Journal of Wellbeing, 7 (3), 56–71.

- Hurlock, E. B. (1925). An evaluation of certain incentives used in school work. Journal of Educational Psychology , 16 (3) , 145–159.

- Inequalitygaps.org. (2020). Students exploring inequality in Canada. Retrieved from https://inequalitygaps.org/first-takes/racism-in-canada/restorative-justice-an-essential-component-to-the-legal-system/

- Joseph, S. (2015). Positive psychology in practice: Promoting human flourishing in work, health, education, and everyday life (2nd ed.). Wiley.

- Košir, K., & Tement, S. (2014). Teacher–student relationship and academic achievement: A cross-lagged longitudinal study on three different age groups. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 29 (3), 409–428.

- Kwok, S. Y., Gu, M., & Kit, K. T. K. (2016). Positive psychology intervention to alleviate child depression and increase life satisfaction: A randomized clinical trial. Research on Social Work Practice, 26 (4), 350–361.

- Larson, R. W. (2000). Toward a psychology of positive youth development. American Psychologist , 55 (1), 170–183.

- Leventhal, K. S., Gillham, J., DeMaria, L., Andrew, G., Peabody, J., & Leventhal, S. (2015). Building psychosocial assets and wellbeing among adolescent girls: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Adolescence, 45 , 284–295.

- Liau, A. K., Neihart, M. F., Teo, C. T., & Lo, C. H. (2016). Effects of the best possible self-activity on subjective wellbeing and depressive symptoms. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 25 (3), 473–481.

- Linkins, M., Niemiec, R. M., Gillham, J., & Mayerson, D. (2015). Through the lens of strength: A framework for educating the heart. The Journal of Positive Psychology , 10 (1), 64–68.

- Mason, H. D. (2018). Grit and academic performance among first-year university students: A brief report. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 28 (1), 66–68.

- McCluskey, G., Lloyd, G., Kane, J., Riddell, S., Stead, J., & Weedon, E. (2008). Can restorative practices in schools make a difference? Educational Review, 60 (4), 405-417.

- McKenna, L. (2019). Making wellbeing practical: An effective guide to helping schools thrive. Unleashing Personal Potential.

- Noble, T., & McGrath, H. (2008). The positive educational practices framework: A tool for facilitating the work of educational psychologists in promoting pupil wellbeing. Educational and Child Psychology, 25 (2), 119–134.

- Norrish, J. M. (2015). Positive education: The Geelong Grammar School journey. Oxford University Press.

- Norrish, J. M., Williams, P., O’Connor, M., & Robinson, J. (2013). An applied framework for positive education. International Journal of Wellbeing, 3 (2), 147–161.

- Norrish, J. M., & Seligman, M. E. (2015). Positive education: The Geelong Grammar School journey. Oxford Positive Psychology Series.

- Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2006). Moral competence and character strengths among adolescents: The development and validation of the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths for Youth. Journal of Adolescence, 29 , 891–905.

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. American Psychological Association.

- Rawana, E., Brownlee, K., Probizanski, M., Harris, H., & Baxter, D. (2014). Reshaping school culture: Implementing a strengths-based approach in schools. The Centre of Education and Research on Positive Youth Development.

- Reivich, K., & Shatté, A. (2002). The resilience factor: 7 Essential skills for overcoming life’s inevitable obstacles. Broadway Books.

- Robinson, J. (2019). Four ways to integrate the power of character strengths into your school. Institute of Positive Education. Retrieved from https://www.ggs.vic.edu.au/blog-posts/four-ways-to-integrate-the-power-of-character-strengths-into-your-school

- Seligman, M. E. P., & Adler, A. (2018). Positive education. In Global Happiness Council, Global Happiness Policy Report 2018 (pp. 52–74). Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

- Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., & Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Review of Education, 35 , 293–311.

- Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist , 60 (5), 410–421.

- Shankland, R., & Rosset, E. (2017). Review of brief school-based positive psychological interventions: A taster for teachers and educators. Educational Psychology Review, 29 (2), 363–392.

- Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How to increase and sustain positive emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves. The Journal of Positive Psychology , 1 (2), 73–82.

- Shoshani, A., & Slone, M. (2017). Positive education for young children: Effects of a positive psychology intervention for preschool children on subjective wellbeing and learning behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 8 (1866), 1–11.

- Shoshani, A., & Steinmetz, S. (2014). Positive psychology at school: A school-based intervention to promote adolescents’ mental health and wellbeing. The Journal of Happiness Studies, 15 (6), 1289–1311.

- Shoshani, A., Steinmetz, S., & Kanat-Maymon, Y. (2016). Effects of the Maytiv positive psychology school program on early adolescents’ wellbeing, engagement, and achievement. Journal of School Psychology, 57 , 73–92.

- Sin, N. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology , 65 (5), 467–487.

- Snyder, J. A. (2014, May 7). Teaching kids ‘grit’ is all the rage: Here’s what’s wrong with it. The New Republic. Retrieved May 21, 2021 from https://newrepublic.com/article/117615/problem-grit-kipp-and-character-based-education

- Tough, P. (2013). How children succeed: Grit, curiosity, and the hidden power of character. Mariner Books.

- Villavicencio, F. T., & Bernardo, A. B. (2016). Beyond math anxiety: Positive emotions predict mathematics achievement, self-regulation, and self-efficacy. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 25 (3), 415–422.

- Washburn, D. (2018). The price of punishment — New report shows students nationwide lost 11 million school days due to suspensions. EdSource. Retrieved from https://edsource.org/2018/the-price-of-punishment-new-report-shows-students-nationwide-lost-11-million-school-days-due-to-suspensions/601889

- Waters, L. (2014). Balancing the curriculum: Teaching gratitude, hope and resilience. In H. Sykes (Ed.), A love of ideas (pp. 117–124). Future Leaders Press.

- Winmalee High School. (2020). Positive education. Retrieved from https://winmalee-h.schools.nsw.gov.au/about-our-school/positive-education.html

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Why is positive education important. What r its advantages?

Hi Nibedita,

Thank you for your question! Positive education integrates traditional educational values with the study of happiness and well-being, aiming to enhance mental health within educational settings. It utilizes Seligman’s PERMA model and VIA classification to promote students’ and educators’ happiness, leading to benefits such as reduced depression, increased life satisfaction, and improved academic performance.

Hope this answers your question! 🙂

Warm regards, Julia | Community Manager

A very insightful read indeed! Positive Education’s integration of traditional principles with happiness and well-being research, such as the PERMA model, is transformative. Implementing character strengths through VIA classification adds depth to nurturing students’ holistic development. A valuable resource for educators at Schools in Magadi Road! #SchoolsInMagadiRoad #PositiveEducation #WellBeingInEducation Thank You Mayank Jain CEO Ezyschooling

Thanks very interesting blog!

Thank you!. I have been looking for information on Positive Education so I can put it into practise in my classroom, and after what I am reading, I am well on the way.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Peer Support: A Student-Led Approach to Mental Wellbeing

Generation Z comprises most full-time students in further and higher education in 2024 and are the world’s first digital natives. Research has shown that Gen [...]

Ensuring Student Success: 7 Tools to Help Students Excel

Ensuring student success requires a multi-faceted approach, incorporating tools like personalized learning plans, effective time management strategies, and emotional support systems. By leveraging technology and [...]

EMDR Training & 6 Best Certification Programs

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy has gained significant recognition for its effectiveness in treating trauma-related conditions and other mental health issues (Oren & [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (52)

- Coaching & Application (40)

- Compassion (23)

- Counseling (41)

- Emotional Intelligence (22)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (18)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (16)

- Mindfulness (40)

- Motivation & Goals (41)

- Optimism & Mindset (29)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (23)

- Positive Education (36)

- Positive Emotions (33)

- Positive Leadership (16)

- Positive Parenting (14)

- Positive Psychology (21)

- Positive Workplace (35)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (39)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (30)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (43)

- Therapy Exercises (38)

- Types of Therapy (55)

Save 60% for a limited time only →

[New!] Wellbeing X©. The low-effort, high-impact wellbeing program.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Meta-Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine