40 Best Essays of All Time (Including Links & Writing Tips)

I had little money (buying forty collections of essays was out of the question) so I’ve found them online instead. I’ve hacked through piles of them, and finally, I’ve found the great ones. Now I want to share the whole list with you (with the addition of my notes about writing). Each item on the list has a direct link to the essay, so please click away and indulge yourself. Also, next to each essay, there’s an image of the book that contains the original work.

About this essay list:

40 best essays of all time (with links and writing tips), 1. david sedaris – laugh, kookaburra.

A great family drama takes place against the backdrop of the Australian wilderness. And the Kookaburra laughs… This is one of the top essays of the lot. It’s a great mixture of family reminiscences, travel writing, and advice on what’s most important in life. You’ll also learn an awful lot about the curious culture of the Aussies.

Writing tips from the essay:

2. charles d’ambrosio – documents.

Do you think your life punches you in the face all too often? After reading this essay, you will change your mind. Reading about loss and hardships often makes us sad at first, but then enables us to feel grateful for our lives . D’Ambrosio shares his documents (poems, letters) that had a major impact on his life, and brilliantly shows how not to let go of the past.

3. E. B. White – Once more to the lake

What does it mean to be a father? Can you see your younger self, reflected in your child? This beautiful essay tells the story of the author, his son, and their traditional stay at a placid lake hidden within the forests of Maine. This place of nature is filled with sunshine and childhood memories. It also provides for one of the greatest meditations on nature and the passing of time.

4. Zadie Smith – Fail Better

Aspiring writers feel tremendous pressure to perform. The daily quota of words often turns out to be nothing more than gibberish. What then? Also, should the writer please the reader or should she be fully independent? What does it mean to be a writer, anyway? This essay is an attempt to answer these questions, but its contents are not only meant for scribblers. Within it, you’ll find some great notes about literary criticism, how we treat art , and the responsibility of the reader.

5. Virginia Woolf – Death of the Moth

6. meghan daum – my misspent youth.

Many of us, at some point or another, dream about living in New York. Meghan Daum’s take on the subject differs slightly from what you might expect. There’s no glamour, no Broadway shows, and no fancy restaurants. Instead, there’s the sullen reality of living in one of the most expensive cities in the world. You’ll get all the juicy details about credit cards, overdue payments, and scrambling for survival. It’s a word of warning. But it’s also a great story about shattered fantasies of living in a big city. Word on the street is: “You ain’t promised mañana in the rotten manzana.”

7. Roger Ebert – Go Gentle Into That Good Night

8. george orwell – shooting an elephant.

Even after one reading, you’ll remember this one for years. The story, set in British Burma, is about shooting an elephant (it’s not for the squeamish). It’s also the most powerful denunciation of colonialism ever put into writing. Orwell, apparently a free representative of British rule, feels to be nothing more than a puppet succumbing to the whim of the mob.

9. George Orwell – A Hanging

10. christopher hitchens – assassins of the mind.

In one of the greatest essays written in defense of free speech, Christopher Hitchens shares many examples of how modern media kneel to the explicit threats of violence posed by Islamic extremists. He recounts the story of his friend, Salman Rushdie, author of Satanic Verses who, for many years, had to watch over his shoulder because of the fatwa of Ayatollah Khomeini. With his usual wit, Hitchens shares various examples of people who died because of their opinions and of editors who refuse to publish anything related to Islam because of fear (and it was written long before the Charlie Hebdo massacre). After reading the essay, you realize that freedom of expression is one of the most precious things we have and that we have to fight for it. I highly recommend all essay collections penned by Hitchens, especially the ones written for Vanity Fair.

11. Christopher Hitchens – The New Commandments

12. phillip lopate – against joie de vivre.

While reading this fantastic essay, this quote from Slavoj Žižek kept coming back to me: “I think that the only life of deep satisfaction is a life of eternal struggle, especially struggle with oneself. If you want to remain happy, just remain stupid. Authentic masters are never happy; happiness is a category of slaves”. I can bear the onus of happiness or joie de vivre for some time. But this force enables me to get free and wallow in the sweet feelings of melancholy and nostalgia. By reading this work of Lopate, you’ll enter into the world of an intelligent man who finds most social rituals a drag. It’s worth exploring.

13. Philip Larkin – The Pleasure Principle

14. sigmund freud – thoughts for the times on war and death.

This essay reveals Freud’s disillusionment with the whole project of Western civilization. How the peaceful European countries could engage in a war that would eventually cost over 17 million lives? What stirs people to kill each other? Is it their nature, or are they puppets of imperial forces with agendas of their own? From the perspective of time, this work by Freud doesn’t seem to be fully accurate. Even so, it’s well worth your time.

15. Zadie Smith – Some Notes on Attunement

“You are privy to a great becoming, but you recognize nothing” – Francis Dolarhyde. This one is about the elusiveness of change occurring within you. For Zadie, it was hard to attune to the vibes of Joni Mitchell – especially her Blue album. But eventually, she grew up to appreciate her genius, and all the other things changed as well. This top essay is all about the relationship between humans, and art. We shouldn’t like art because we’re supposed to. We should like it because it has an instantaneous, emotional effect on us. Although, according to Stansfield (Gary Oldman) in Léon, liking Beethoven is rather mandatory.

16. Annie Dillard – Total Eclipse

My imagination was always stirred by the scene of the solar eclipse in Pharaoh, by Boleslaw Prus. I wondered about the shock of the disoriented crowd when they saw how their ruler could switch off the light. Getting immersed in this essay by Annie Dillard has a similar effect. It produces amazement and some kind of primeval fear. It’s not only the environment that changes; it’s your mind and the perception of the world. After the eclipse, nothing is going to be the same again.

17. Édouard Levé – When I Look at a Strawberry, I Think of a Tongue

This suicidally beautiful essay will teach you a lot about the appreciation of life and the struggle with mental illness. It’s a collection of personal, apparently unrelated thoughts that show us the rich interior of the author. You look at the real-time thoughts of another person, and then recognize the same patterns within yourself… It sounds like a confession of a person who’s about to take their life, and it’s striking in its originality.

18. Gloria E. Anzaldúa – How to Tame a Wild Tongue

19. kurt vonnegut – dispatch from a man without a country.

In terms of style, this essay is flawless. It’s simple, conversational, humorous, and yet, full of wisdom. And when Vonnegut becomes a teacher and draws an axis of “beginning – end”, and, “good fortune – bad fortune” to explain literature, it becomes outright hilarious. It’s hard to find an author with such a down-to-earth approach. He doesn’t need to get intellectual to prove a point. And the point could be summed up by the quote from Great Expectations – “On the Rampage, Pip, and off the Rampage, Pip – such is Life!”

20. Mary Ruefle – On Fear

Most psychologists and gurus agree that fear is the greatest enemy of success or any creative activity. It’s programmed into our minds to keep us away from imaginary harm. Mary Ruefle takes on this basic human emotion with flair. She explores fear from so many angles (especially in the world of poetry-writing) that at the end of this personal essay, you will look at it, dissect it, untangle it, and hopefully be able to say “f**k you” the next time your brain is trying to stop you.

21. Susan Sontag – Against Interpretation

In this highly intellectual essay, Sontag fights for art and its interpretation. It’s a great lesson, especially for critics and interpreters who endlessly chew on works that simply defy interpretation. Why don’t we just leave the art alone? I always hated it when at school they asked me: “What did the author have in mind when he did X or Y?” Iēsous Pantocrator! Hell if I know! I will judge it through my subjective experience!

22. Nora Ephron – A Few Words About Breasts

This is a heartwarming, coming-of-age story about a young girl who waits in vain for her breasts to grow. It’s simply a humorous and pleasurable read. The size of breasts is a big deal for women. If you’re a man, you may peek into the mind of a woman and learn many interesting things. If you’re a woman, maybe you’ll be able to relate and at last, be at peace with your bosom.

23. Carl Sagan – Does Truth Matter – Science, Pseudoscience, and Civilization

24. paul graham – how to do what you love.

How To Do What You Love should be read by every college student and young adult. The Internet is flooded with a large number of articles and videos that are supposed to tell you what to do with your life. Most of them are worthless, but this one is different. It’s sincere, and there’s no hidden agenda behind it. There’s so much we take for granted – what we study, where we work, what we do in our free time… Surely we have another two hundred years to figure it out, right? Life’s too short to be so naïve. Please, read the essay and let it help you gain fulfillment from your work.

25. John Jeremiah Sullivan – Mister Lytle

A young, aspiring writer is about to become a nurse of a fading writer – Mister Lytle (Andrew Nelson Lytle), and there will be trouble. This essay by Sullivan is probably my favorite one from the whole list. The amount of beautiful sentences it contains is just overwhelming. But that’s just a part of its charm. It also takes you to the Old South which has an incredible atmosphere. It’s grim and tawny but you want to stay there for a while.

26. Joan Didion – On Self Respect

Normally, with that title, you would expect some straightforward advice about how to improve your character and get on with your goddamn life – but not from Joan Didion. From the very beginning, you can feel the depth of her thinking, and the unmistakable style of a true woman who’s been hurt. You can learn more from this essay than from whole books about self-improvement . It reminds me of the scene from True Detective, where Frank Semyon tells Ray Velcoro to “own it” after he realizes he killed the wrong man all these years ago. I guess we all have to “own it”, recognize our mistakes, and move forward sometimes.

27. Susan Sontag – Notes on Camp

I’ve never read anything so thorough and lucid about an artistic current. After reading this essay, you will know what camp is. But not only that – you will learn about so many artists you’ve never heard of. You will follow their traces and go to places where you’ve never been before. You will vastly increase your appreciation of art. It’s interesting how something written as a list could be so amazing. All the listicles we usually see on the web simply cannot compare with it.

28. Ralph Waldo Emerson – Self-Reliance

29. david foster wallace – consider the lobster.

When you want simple field notes about a food festival, you needn’t send there the formidable David Foster Wallace. He sees right through the hypocrisy and cruelty behind killing hundreds of thousands of innocent lobsters – by boiling them alive. This essay uncovers some of the worst traits of modern American people. There are no apologies or hedging one’s bets. There’s just plain truth that stabs you in the eye like a lobster claw. After reading this essay, you may reconsider the whole animal-eating business.

30. David Foster Wallace – The Nature of the Fun

The famous novelist and author of the most powerful commencement speech ever done is going to tell you about the joys and sorrows of writing a work of fiction. It’s like taking care of a mutant child that constantly oozes smelly liquids. But you love that child and you want others to love it too. It’s a very humorous account of what it means to be an author. If you ever plan to write a novel, you should read that one. And the story about the Chinese farmer is just priceless.

31. Margaret Atwood – Attitude

This is not an essay per se, but I included it on the list for the sake of variety. It was delivered as a commencement speech at The University of Toronto, and it’s about keeping the right attitude. Soon after leaving university, most graduates have to forget about safety, parties, and travel and start a new life – one filled with a painful routine that will last until they drop. Atwood says that you don’t have to accept that. You can choose how you react to everything that happens to you (and you don’t have to stay in that dead-end job for the rest of your days).

32. Jo Ann Beard – The Fourth State of Matter

Read that one as soon as possible. It’s one of the most masterful and impactful essays you’ll ever read. It’s like a good horror – a slow build-up, and then your jaw drops to the ground. To summarize the story would be to spoil it, so I recommend that you just dig in and devour this essay in one sitting. It’s a perfect example of “show, don’t tell” writing, where the actions of characters are enough to create the right effect. No need for flowery adjectives here.

33. Terence McKenna – Tryptamine Hallucinogens and Consciousness

34. eudora welty – the little store.

By reading this little-known essay, you will be transported into the world of the old American South. It’s a remembrance of trips to the little store in a little town. It’s warm and straightforward, and when you read it, you feel like a child once more. All these beautiful memories live inside of us. They lay somewhere deep in our minds, hidden from sight. The work by Eudora Welty is an attempt to uncover some of them and let you get reacquainted with some smells and tastes of the past.

35. John McPhee – The Search for Marvin Gardens

The Search for Marvin Gardens contains many layers of meaning. It’s a story about a Monopoly championship, but also, it’s the author’s search for the lost streets visible on the board of the famous board game. It also presents a historical perspective on the rise and fall of civilizations, and on Atlantic City, which once was a lively place, and then, slowly declined, the streets filled with dirt and broken windows.

36. Maxine Hong Kingston – No Name Woman

A dead body at the bottom of the well makes for a beautiful literary device. The first line of Orhan Pamuk’s novel My Name Is Red delivers it perfectly: “I am nothing but a corpse now, a body at the bottom of a well”. There’s something creepy about the idea of the well. Just think about the “It puts the lotion in the basket” scene from The Silence of the Lambs. In the first paragraph of Kingston’s essay, we learn about a suicide committed by uncommon means of jumping into the well. But this time it’s a real story. Who was this woman? Why did she do it? Read the essay.

37. Joan Didion – On Keeping A Notebook

38. joan didion – goodbye to all that, 39. george orwell – reflections on gandhi, 40. george orwell – politics and the english language, other essays you may find interesting, oliver sacks – on libraries.

One of the greatest contributors to the knowledge about the human mind, Oliver Sacks meditates on the value of libraries and his love of books.

Noam Chomsky – The Responsibility of Intellectuals

Sam harris – the riddle of the gun.

Sam Harris, now a famous philosopher and neuroscientist, takes on the problem of gun control in the United States. His thoughts are clear of prejudice. After reading this, you’ll appreciate the value of logical discourse overheated, irrational debate that more often than not has real implications on policy.

Tim Ferriss – Some Practical Thoughts on Suicide

Edward said – reflections on exile.

The life of Edward Said was a truly fascinating one. Born in Jerusalem, he lived between Palestine and Egypt and finally settled down in the United States, where he completed his most famous work – Orientalism. In this essay, he shares his thoughts about what it means to be in exile.

Richard Feynman – It’s as Simple as One, Two, Three…

Rabindranath tagore – the religion of the forest, richard dawkins – letter to his 10-year-old daughter.

Every father should be able to articulate his philosophy of life to his children. With this letter that’s similar to what you find in the Paris Review essays , the famed atheist and defender of reason, Richard Dawkins, does exactly that. It’s beautifully written and stresses the importance of looking at evidence when we’re trying to make sense of the world.

Albert Camus – The Minotaur (or, The Stop In Oran)

Koty neelis – 21 incredible life lessons from anthony bourdain.

I included it as the last one because it’s not really an essay, but I just had to put it somewhere. In this listicle, you’ll find the 21 most original thoughts of the high-profile cook, writer, and TV host, Anthony Bourdain. Some of them are shocking, others are funny, but they’re all worth checking out.

Lucius Annaeus Seneca – On the Shortness of Life

Bertrand russell – in praise of idleness, james baldwin – stranger in the village.

It’s an essay on the author’s experiences as an African-American in a Swiss village, exploring race, identity, and alienation while highlighting the complexities of racial dynamics and the quest for belonging.

Bonus – More writing tips from two great books

The sense of style – by steven pinker, on writing well – by william zinsser, now immerse yourself in the world of essays, rafal reyzer.

Hey there, welcome to my blog! I'm a full-time entrepreneur building two companies, a digital marketer, and a content creator with 10+ years of experience. I started RafalReyzer.com to provide you with great tools and strategies you can use to become a proficient digital marketer and achieve freedom through online creativity. My site is a one-stop shop for digital marketers, and content enthusiasts who want to be independent, earn more money, and create beautiful things. Explore my journey here , and don't miss out on my AI Marketing Mastery online course.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write Top-Graded Essays in English

5-minute read

- 7th December 2022

Writing English papers and essays can be challenging at first, but with the right tools, knowledge, and resources, you can improve your writing skills. In this article, you’ll get some tips and tricks on how to write a top-graded essay in English.

Have you heard the saying “practice makes perfect”? Well, it’s wrong. Practice does make improvement, though. Whether you’re taking an English composition class, studying for the IELTS or TOEFL , or preparing to study abroad, you can always find new ways to practice writing in English.

If you practice on a daily basis, you’ll be exercising the skills you know while challenging yourself to learn even more. There are many ways you can practice writing in English daily:

- Keep a daily journal.

- Write practice essays.

- Do creative writing exercises .

Read in English

The best way to improve your writing is to read English books, news articles, essays, and other media. By reading the writing of other authors (whether they’re native or non-native speakers), you’re exposing yourself to different writing styles and learning new vocabulary. Be sure to take notes when you’re reading so you can write down things you don’t know (e.g., new words or phrases) or sentences or phrases you like.

For example, maybe you need to write a paper related to climate change. By reading news articles or research papers on this topic, you can learn relevant vocabulary and knowledge you can use in your essay.

FluentU has a great article with a list of 20 classic books you can read in English for free.

Immerse Yourself in English

If you don’t live in an English-speaking country, you may be thinking, “How can I immerse myself in English?” There are many ways to overcome this challenge. The following strategies are especially useful if you plan to study or travel abroad:

- Follow YouTube channels that focus on learning English or that have English speakers.

- Use social media to follow English-speaking accounts you are interested in.

- Watch movies and TV shows in English or use English subtitles when watching your favorite shows.

- Participate in your English club or salon at school to get more practice.

- Become an English tutor at a local school (teaching others is the best way to learn).

By constantly exposing yourself to English, you will improve your writing and speaking skills.

Visit Your Writing Center

If you’re enrolled at a university, you most likely have a free writing center you can use if you need help with your assignments. If you don’t have a writing center, ask your teacher for help and for information on local resources.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Use Your Feedback

After you submit an English writing assignment, you should receive feedback from your teacher on how you did. Use this feedback to your advantage. If you haven’t been getting feedback on your writing, ask your teacher to explain what issues they are seeing in your writing and what you could do to improve.

Be Aware of Your Common Writing Mistakes

If you review your feedback on writing assignments, you might notice some recurring mistakes you are making. Make a list of common mistakes you tend to make when writing, and use it when doing future assignments. Some common mistakes include the following:

- Grammar errors (e.g., not using articles).

- Incorrect vocabulary (e.g., confusing however and therefore ).

- Spelling mistakes (e.g., writing form when you mean from ).

- Missing essay components (e.g., not using a thesis statement in your introduction).

- Not using examples in your body paragraphs.

- Not writing an effective conclusion .

This is just a general list of writing mistakes, some of which you may make. But be sure to go through your writing feedback or talk with your teacher to make a list of your most common mistakes.

Use a Prewriting Strategy

So many students sit down to write an essay without a plan. They just start writing whatever comes to their mind. However, to write a top-graded essay in English, you must plan and brainstorm before you begin to write. Here are some strategies you can use during the prewriting stage:

- Freewriting

- Concept Mapping

For more detailed information on each of these processes, read “5 Useful Prewriting Strategies.”

Follow the Writing Process

All writers should follow a writing process. However, the writing process can vary depending on what you’re writing. For example, the process for a Ph.D. thesis is going to look different to that of a news article. Regardless, there are some basic steps that all writers should follow:

- Understanding the assignment, essay question, or writing topic.

- Planning, outlining, and prewriting.

- Writing a thesis statement.

- Writing your essay.

- Revising and editing.

Writing essays, theses, news articles, or papers in English can be challenging. They take a lot of work, practice, and persistence. However, with these tips, you will be on your way to writing top-graded English essays.

If you need more help with your English writing, the experts at Proofed will proofread your first 500 words for free!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

Free email newsletter template.

Promoting a brand means sharing valuable insights to connect more deeply with your audience, and...

6-minute read

How to Write a Nonprofit Grant Proposal

If you’re seeking funding to support your charitable endeavors as a nonprofit organization, you’ll need...

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Save £500 when you enrol by 30th September! T&C’s apply

- How to Write Dazzlingly Brilliant Essays: Sharp Advice for Ambitious Students

Rachel McCombie, a graduate of St John’s College, Oxford, shares actionable tips on taking your essays from “Good” to “Outstanding.”

For ambitious students, essays are a chance to showcase academic flair, demonstrate original thinking and impress with advanced written English skills.

The best students relish the challenge of writing essays because they’re a chance to exercise academic research skills and construct interesting arguments. Essays allow you to demonstrate your knowledge, understanding and intelligence in a creative and relatively unrestricted way – provided you keep within the word count! But when lots of other people are answering the same essay question as you, how do you make yours stand out from the crowd? In this article, we’re going to show you the secret of writing a truly brilliant essay.

What are essays actually for?

Before we get into the nitty gritty of how to write an outstanding essay, we need to go right back to basics and think about what essays are actually designed to test. Only by understanding the purpose of an essay can you really begin to understand what it is that tutors are looking for when they read your work. No matter what the academic level of the student is, essays are designed to test many things: – Knowledge – fundamentally, essays test and help consolidate what you’ve read and learned, making them an important part of the learning process, particularly for humanities subjects. – Comprehension – they test your ability to make sense of and clearly explain complex concepts and issues. – They test your ability to understand the question and produce a considered response to it. – They evaluate your ability to absorb and condense information from a variety of sources , which will probably mean covering a lot of material in a short space of time; this necessitates appraisal of which bits of material are relevant and which are not. – They test your ability to write a balanced and coherent argument that considers a number of points of view. – They showcase your level of written English skills. – They even put your time management to the test – essays are a part of your workload that must be planned, prioritised and delivered to a high standard, to deadline.

Characteristics of the perfect essay

Now that we know why we’re asked to write essays, what are the characteristics that define the essays that impress? The tutors marking your essays may have their own preferences and things they look for in outstanding essays, but let’s take a look at a few of the irrefutable traits of the best.

Original thinking

The hallmark of the truly brilliant essay is original thinking. That doesn’t have to mean coming up with an entirely new theory; most of, if not all, the topics you’ll be studying at GCSE , A-level or even undergraduate level have been thought about in so much depth and by so many people that virtually every possible angle will have been thought of already. But what it does mean is that the essay stands out from those of other students in that it goes beyond the obvious and takes an original approach – perhaps approaching the topic from a different angle, coming up with a different hypothesis from what you’ve been discussing in class, or introducing new evidence and intelligent insights from material not included on the reading list.

Solid, in-depth knowledge and understanding

It goes without saying that the brilliant essay should demonstrate a strong knowledge of the facts, and not just knowledge but sound comprehension of the concepts or issues being discussed and why they matter. The perfect essay demonstrates an ability to deploy relevant facts and use them to form the basis of an argument or hypothesis. It covers a wide range of material and considers every point of view, confidently making use of and quoting from a variety of sources.

Clear structure with intelligent debate

The perfect essay provides a coherent discussion of both sides of the story, developing a balanced argument throughout, and with a conclusion that weighs up the evidence you’ve covered and perhaps provides your own intelligent opinion on how the topic should be interpreted based on the evidence covered.

No superfluous information

Everything written in the perfect essay serves a purpose – to inform and persuade. There’s no rambling or going off at tangents – it sticks to the point and doesn’t waste the reader’s time. This goes back to our earlier point about sorting the relevant facts from the irrelevant material; including material that isn’t relevant shows that you’ve not quite grasped the real heart of the matter.

Exceptional English

The words in the perfect essay flow effortlessly, and the reader feels in safe hands. Sentences need never be read more than once to be understood, and each follows logically on from the next, with no random jumping about from topic to topic from one paragraph to the next. Spelling and grammar are flawless, with no careless typos. So how do you go about writing this mythical Perfect Essay? Read on to find out!

Put in extra background work

Committed students always read beyond what the reading list tells them to read. Guaranteed to impress, wide reading gives you deeper knowledge than your peers and gives you the extra knowledge and insights you need to make your essay stand out. If you’re studying English, for example, don’t just read the set text! Here are some ideas to widen your reading and give you a good range of impressive quotes to include in your essay: – Other works by the same author – how do they compare with your set text? – Works by contemporary authors – does your set text fit into a wider movement, or is it very different from what was being written at the time? – Works by the author’s predecessors – what works inspired the author of your set text? How do you see them shining through in the text you’re studying, and how have they been developed? – Literary criticism – gauge the range of opinions about your set text by reading what the literary critics have to say. Whose opinion do you most agree with, and why? – Background history – so that you can appreciate and refer to the context in which the author was writing (we’ll come back to this last point a little later). It sounds like a lot of extra work, but you don’t necessarily have to read everything in full. It’s fine to dip into these other resources providing you don’t inadvertently take points out of context.

Know what you want to say before you start writing

You’re probably sick of hearing this particular piece of advice, but it’s important to start out with a clear idea in your mind of what you want to say in your essay and how you will structure your arguments. The easiest way to do this is to write an essay plan. This needn’t be a big deal, or time-consuming; all you need to do is to open a new document on your computer, type out the ideas you want to cover and drag and drop them into a logical order. From there, you simply start typing your essay directly into the plan itself. Your essay should include an introduction, a series of paragraphs that develop an argument rather than just jumping from topic to topic, and a conclusion that weighs up the evidence.

Answer the question you’ve been set, not the question you want to answer

A common problem with students’ responses to essays is that rather than answering the question they’ve been set , they try to mould the question to what they’d prefer to write about, because that’s what they feel most comfortable with. Be very careful not to do this! You could end up writing a brilliant essay, but if didn’t actually answer the question then it’s not going to be well received by the person marking it.

Give a balanced argument…

Good essays give both sides of an argument, presenting information impartially and considering multiple points of view. One-sided arguments won’t impress, as you need to show that you’ve thought about the evidence comprehensively.

…but your opinion and interpretation matter too

Show that you’ve made your own mind up based on your weighing up of the evidence. This shows that you’re not just hiding behind what other people say about the topic, but that you’ve had the independence of mind to form your own intelligent opinion about it.

Quote liberally

Use quotations from academic works and sources to back up points you want to make. Doing so strengthens your argument by providing evidence for your statements, as well as demonstrating that you’ve read widely around your subject. However, don’t go too far and write an essay that’s essentially just a list of what other people say about the subject. Quoting too much suggests that you don’t have the confidence or knowledge to explain things in your own words, so have to hide behind those of other people. Make your own mind up about what you’re writing about – as already mentioned, it’s fine to state your own opinion if you’ve considered the arguments and presented the evidence.

Context matters

As we’ve already touched on, if you can demonstrate knowledge of the context of the subject you’re writing about, this will show that you’ve considered possible historical influences that may have shaped a work or issue. This shows that you haven’t simply taken the essay question at face value and demonstrates your ability to think beyond the obvious. An ability to look at the wider picture marks you out as an exceptional student, as many people can’t see the wood for the trees and have a very narrow focus when it comes to writing essays. If you’re an English student, for instance, an author’s work should be considered not in isolation but in the context of the historical events and thinking that helped define the period in which the author was writing. You can’t write about Blake’s poetry without some knowledge and discussion of background events such as the Industrial Revolution, and the development of the Romantic movement as a whole.

Include images and diagrams

You know what they say – a picture speaks a thousand words. What matters in an essay is effective and persuasive communication, and if a picture or diagram will help support a point you’re making, include it. As well as helping to communicate, visuals also make your essay more enjoyable to read for the person marking it – and if they enjoy reading it, the chances are you’ll get better marks! Don’t forget to ensure that you include credits for any images and diagrams you include.

Use full academic citations and a bibliography

Show you mean business by including a full set of academic citations, with a bibliography at the end, even if you haven’t been told to. The great thing about this is that it not only makes you look organised and scholarly, but it also gives you the opportunity to show off just how many extra texts you’ve studied to produce your masterpiece of an essay! Make use of the footnote feature in your word processor and include citations at the bottom of each page, with a main bibliography at the end of the essay. There are different accepted forms for citing an academic reference, but the main thing to remember is to pick one format and be consistent. Typically the citation will include the title and author of the work, the date of publication and the page number(s) of the point or quotation you’re referring to. Here’s an example: 1. Curta, F. (2007) – “Some remarks on ethnicity in medieval archaeology” in Early Medieval Europe 15 (2), pp. 159-185

Before you ask, no, a spell check isn’t good enough! How many times have you typed “form” instead of “from”? That’s just one of a huge number of errors that spell check would simply miss. Your English should be impeccable if you want to be taken seriously, and that means clear and intelligent sentence structures, no misplaced apostrophes, no typos and no grammar crimes. Include your name at the top of each page of your essay, and number the pages. Also, make sure you use a font that’s easy to read, such as Times New Roman or Arial. The person marking your essay won’t appreciate having to struggle through reading a fancy Gothic font, even if it does happen to match the Gothic literature you’re studying!

Meet the deadline

You don’t need us to tell you that, but for the sake of being comprehensive, we’re including it anyway. You could write the best essay ever, but if you deliver it late, it won’t be looked upon favourably! Don’t leave writing your essay until the last minute – start writing with plenty of time to spare, and ideally leave time to sleep on it before you submit it. Allowing time for it to sink in may result in you having a sudden brilliant revelation that you want to include. So there we have it – everything you need to know in order to write an essay to impress. If you want to get ahead, you might also want to think about attending an English summer school .

Image credits: banner

Improve your English. Speak with confidence!

- Free Mini Course

- Posted in in Writing

30 Advanced Essay Words to Improve Your Grades

- Posted by by Cameron Smith

- 12 months ago

- Updated 2 months ago

In this guide, you’ll find 30 advanced essay words to use in academic writing. Advanced English words are great for making academic writing more impressive and persuasive, which has the potential to wow teachers and professors, and even improve your grades.

30 Advanced Essay Words

- Definition: Present, appearing, or found everywhere.

- Example: The smartphone has become ubiquitous in modern society.

- Replaces: Common, widespread, prevalent.

- Definition: Fluent or persuasive in speaking or writing.

- Example: Her eloquent speech captivated the audience.

- Replaces: Well-spoken, articulate.

- Definition: To make less severe, serious, or painful.

- Example: Planting more trees can help mitigate the effects of climate change.

- Replaces: Alleviate, lessen, reduce.

- Definition: In contrast or opposite to what was previously mentioned.

- Example: Some believe in climate change; conversely, others deny its existence.

- Replaces: On the other hand, in opposition.

- Definition: Stated or appearing to be true, but not necessarily so.

- Example: His ostensible reason for the delay was a traffic jam.

- Replaces: Apparent, seeming, supposed.

- Definition: A countless or extremely great number.

- Example: The internet offers a myriad of resources for research.

- Replaces: Countless, numerous.

- Definition: Exceeding what is necessary or required.

- Example: His lengthy introduction was filled with superfluous details.

- Replaces: Excessive, redundant.

- Definition: To cause something to happen suddenly or unexpectedly.

- Example: The economic crisis precipitated widespread unemployment.

- Replaces: Trigger, prompt.

- Definition: Too great or extreme to be expressed or described in words.

- Example: The beauty of the sunset over the ocean was ineffable.

- Replaces: Indescribable, inexpressible.

- Definition: Having knowledge or awareness of something.

- Example: She was cognizant of the risks involved in the project.

- Replaces: Aware, conscious.

- Definition: Relevant or applicable to a particular matter.

- Example: Please provide only pertinent information in your report.

- Replaces: Relevant, related.

- Definition: Showing great attention to detail; very careful and precise.

- Example: The researcher conducted a meticulous analysis of the data.

- Replaces: Thorough, careful.

- Definition: Capable of producing the desired result or effect.

- Example: The medication has proved to be efficacious in treating the disease.

- Replaces: Effective, successful.

- Definition: Mentioned earlier in the text or conversation.

- Example: The aforementioned study provides valuable insights.

- Replaces: Previously mentioned, previously discussed.

- Definition: To make a problem, situation, or condition worse.

- Example: His criticism only served to exacerbate the conflict.

- Replaces: Worsen, intensify.

- Definition: The state or capacity of being everywhere, especially at the same time.

- Example: The ubiquity of social media has changed how we communicate.

- Replaces: Omnipresence, pervasiveness.

- Definition: In every case or on every occasion; always.

- Example: The professor’s lectures are invariably informative.

- Replaces: Always, consistently.

- Definition: To be a perfect example or representation of something.

- Example: The city’s skyline epitomizes modern architecture.

- Replaces: Symbolize, represent.

- Definition: A harsh, discordant mixture of sounds.

- Example: The cacophony of car horns during rush hour was deafening.

- Replaces: Discord, noise.

- Definition: A person who acts obsequiously toward someone important to gain advantage.

- Example: He surrounded himself with sycophants who praised his every move.

- Replaces: Flatterer, yes-man.

- Definition: To render unclear, obscure, or unintelligible.

- Example: The politician attempted to obfuscate the details of the scandal.

- Replaces: Confuse, obscure.

- Definition: Having or showing keen mental discernment and good judgment.

- Example: Her sagacious advice guided the team to success.

- Replaces: Wise, insightful.

- Definition: Not or no longer needed or useful; superfluous.

- Example: His repeated explanations were redundant and added no value.

- Replaces: Unnecessary, surplus.

- Definition: Unwilling or refusing to change one’s views or to agree about something.

- Example: The intransigent negotiators couldn’t reach a compromise.

- Replaces: Unyielding, stubborn.

- Definition: Characterized by vulgar or pretentious display; designed to impress or attract notice.

- Example: The mansion’s ostentatious decorations were overwhelming.

- Replaces: Showy, extravagant.

- Definition: A tendency to choose or do something regularly; an inclination or predisposition.

- Example: She had a proclivity for taking risks in her business ventures.

- Replaces: Tendency, inclination.

- Definition: Difficult to interpret or understand; mysterious.

- Example: The artist’s enigmatic paintings left viewers puzzled.

- Replaces: Mysterious, cryptic.

- Definition: Having a harmful effect, especially in a gradual or subtle way.

- Example: The pernicious influence of gossip can damage reputations.

- Replaces: Harmful, destructive.

- Definition: Shining with great brightness.

- Example: The bride looked resplendent in her wedding gown.

- Replaces: Radiant, splendid.

- Definition: Optimistic, especially in a difficult or challenging situation.

- Example: Despite the setbacks, he remained sanguine.

- Replaces: Optimistic, hopeful.

Using these advanced words in your essays can elevate your writing, making it more precise, engaging, and impactful.

As you work on your essays, consider the nuanced meanings and applications of these advanced words, and use them judiciously to enhance the quality of your academic writing.

Cameron Smith

Cameron Smith is an English Communication Coach based in Vancouver, Canada. He's the founder of Learn English Every Day, and he's on a mission to help millions of people speak English with confidence. If you want longer video content, please follow me on YouTube for fun English lessons and helpful learning resources!

Post navigation

- Posted in in ESL Conversation Questions

170 Small Talk Questions to Start a Conversation with Anyone

- September 12, 2023

- Posted in in Business English

60 Essential Business Idioms: Sound Fluent at Work!

- October 14, 2023

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Rewrite your text with precision and ease

Transform your text with DeepL Write, the AI-driven paraphraser and grammar checker. Offering unparalleled accuracy and versatility in rewriting, experience the future of paraphrasing today. And for unlimited text improvement, try DeepL Write Pro.

Revolutionize your writing with our advanced AI paraphraser

Embrace the power of DeepL’s cutting-edge AI to transform your writing. Our paraphrasing tool goes beyond simple synonym replacement, using a sophisticated language model to capture and convey the nuances of your text.

With our paraphraser, you'll not only retain the essence of your original content, but also enhance its clarity.

We currently offer text rewriting only in English, German, French and Spanish. In the future, we'll release new languages gradually to ensure we deliver texts that are not just rewritten, but elevated.

Why use DeepL’s paraphrasing tool?

With our AI writing assistant, you can:

Improve your writing

Enhance the style, clarity, tone, and grammar of your writing, especially in professional contexts.

Avoid errors

Forgo errors and present your ideas concisely for more polished writing. Our tool also serves as a powerful spell checker.

Speed up writing

Expedite the writing process with suggestions for more formal, refined language.

Express yourself clearly

Perfect sentences and express yourself clearly—particularly for non-native speakers.

Here's what you can do with our paraphraser

For business or academic use:

Great for short-form writing, like emails or messages, and long-form content, like PowerPoint presentations, essays, or scientific papers.

For personal use:

Improve your writing and vocabulary, generate ideas, and express your thoughts more clearly.

DeepL’s paraphraser is also helpful for language learners. For example, you can memorize suggested vocabulary and phrases.

Key features of our AI paraphrasing tool

Incorporated into translator: Translate your text into English or German, and click "Improve translation" to explore alternate versions of your translation. No more copy/paste between tools.

Easy-to-see changes: When you insert the text to be rewritten, activate "Show changes" to see suggested edits.

AI-powered suggestions: By deactivating "Show changes", you can click on any word to see suggestions and refine your writing.

Grammar and spell checker: Our paraphrasing tool is all-in-one, helping you correct grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors.

Helpful integrations: Access our paraphrasing tool in Gmail, Google Slides, or Google Docs , via our browser extension or in Microsoft Word via add-ins .

Still have questions about DeepL’s paraphrasing tool?

1. what makes our paraphrasing tool unique.

DeepL uses advanced AI to provide high-quality, context-aware paraphrasing in English and German. Our tool intelligently restructures and rephrases text, preserving the original meaning and enhancing your writing.

2. How do you use DeepL’s paraphrasing tool?

To accomplish writing tasks, you can:

- Paste your existing text into the tool

- Compose directly in the tool

- Use DeepL Translator before refining your writing with our paraphraser

3. Can the tool paraphrase complex academic texts?

Absolutely. DeepL's paraphraser is designed to handle complex sentence structures, making it useful for academic writing.

4. How does DeepL's paraphraser support language learners?

By making suggestions, the tool enables you to learn new phrases or words to incorporate into your vocabulary.

5. Is the paraphrasing tool free to use?

The amount of text you can improve is limited if you want to use the tool for free. For maximum security, unlimited text improvement and unlimited use of writing styles, it's best to upgrade to DeepL Write Pro. The other advantage of upgrading to the Pro version is that you'll also benefit from the advanced features of the translator.

Explore the capabilities of our tool

Unlock advanced paraphrasing to refine your writing with precision and clarity. Upgrade to the Pro version for enhanced rewriting options, maximum security, and faster results.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Check your paper for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- College essay

How to Write a College Essay | A Complete Guide & Examples

The college essay can make or break your application. It’s your chance to provide personal context, communicate your values and qualities, and set yourself apart from other students.

A standout essay has a few key ingredients:

- A unique, personal topic

- A compelling, well-structured narrative

- A clear, creative writing style

- Evidence of self-reflection and insight

To achieve this, it’s crucial to give yourself enough time for brainstorming, writing, revision, and feedback.

In this comprehensive guide, we walk you through every step in the process of writing a college admissions essay.

Table of contents

Why do you need a standout essay, start organizing early, choose a unique topic, outline your essay, start with a memorable introduction, write like an artist, craft a strong conclusion, revise and receive feedback, frequently asked questions.

While most of your application lists your academic achievements, your college admissions essay is your opportunity to share who you are and why you’d be a good addition to the university.

Your college admissions essay accounts for about 25% of your application’s total weight一and may account for even more with some colleges making the SAT and ACT tests optional. The college admissions essay may be the deciding factor in your application, especially for competitive schools where most applicants have exceptional grades, test scores, and extracurriculars.

What do colleges look for in an essay?

Admissions officers want to understand your background, personality, and values to get a fuller picture of you beyond your test scores and grades. Here’s what colleges look for in an essay :

- Demonstrated values and qualities

- Vulnerability and authenticity

- Self-reflection and insight

- Creative, clear, and concise writing skills

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

It’s a good idea to start organizing your college application timeline in the summer of your junior year to make your application process easier. This will give you ample time for essay brainstorming, writing, revision, and feedback.

While timelines will vary for each student, aim to spend at least 1–3 weeks brainstorming and writing your first draft and at least 2–4 weeks revising across multiple drafts. Remember to leave enough time for breaks in between each writing and editing stage.

Create an essay tracker sheet

If you’re applying to multiple schools, you will have to juggle writing several essays for each one. We recommend using an essay tracker spreadsheet to help you visualize and organize the following:

- Deadlines and number of essays needed

- Prompt overlap, allowing you to write one essay for similar prompts

You can build your own essay tracker using our free Google Sheets template.

College essay tracker template

Ideally, you should start brainstorming college essay topics the summer before your senior year. Keep in mind that it’s easier to write a standout essay with a unique topic.

If you want to write about a common essay topic, such as a sports injury or volunteer work overseas, think carefully about how you can make it unique and personal. You’ll need to demonstrate deep insight and write your story in an original way to differentiate it from similar essays.

What makes a good topic?

- Meaningful and personal to you

- Uncommon or has an unusual angle

- Reveals something different from the rest of your application

Brainstorming questions

You should do a comprehensive brainstorm before choosing your topic. Here are a few questions to get started:

- What are your top five values? What lived experiences demonstrate these values?

- What adjectives would your friends and family use to describe you?

- What challenges or failures have you faced and overcome? What lessons did you learn from them?

- What makes you different from your classmates?

- What are some objects that represent your identity, your community, your relationships, your passions, or your goals?

- Whom do you admire most? Why?

- What three people have significantly impacted your life? How did they influence you?

How to identify your topic

Here are two strategies for identifying a topic that demonstrates your values:

- Start with your qualities : First, identify positive qualities about yourself; then, brainstorm stories that demonstrate these qualities.

- Start with a story : Brainstorm a list of memorable life moments; then, identify a value shown in each story.

After choosing your topic, organize your ideas in an essay outline , which will help keep you focused while writing. Unlike a five-paragraph academic essay, there’s no set structure for a college admissions essay. You can take a more creative approach, using storytelling techniques to shape your essay.

Two common approaches are to structure your essay as a series of vignettes or as a single narrative.

Vignettes structure

The vignette, or montage, structure weaves together several stories united by a common theme. Each story should demonstrate one of your values or qualities and conclude with an insight or future outlook.

This structure gives the admissions officer glimpses into your personality, background, and identity, and shows how your qualities appear in different areas of your life.

Topic: Museum with a “five senses” exhibit of my experiences

- Introduction: Tour guide introduces my museum and my “Making Sense of My Heritage” exhibit

- Story: Racial discrimination with my eyes

- Lesson: Using my writing to document truth

- Story: Broadway musical interests

- Lesson: Finding my voice

- Story: Smells from family dinner table

- Lesson: Appreciating home and family

- Story: Washing dishes

- Lesson: Finding moments of peace in busy schedule

- Story: Biking with Ava

- Lesson: Finding pleasure in job well done

- Conclusion: Tour guide concludes tour, invites guest to come back for “fall College Collection,” featuring my search for identity and learning.

Single story structure

The single story, or narrative, structure uses a chronological narrative to show a student’s character development over time. Some narrative essays detail moments in a relatively brief event, while others narrate a longer journey spanning months or years.

Single story essays are effective if you have overcome a significant challenge or want to demonstrate personal development.

Topic: Sports injury helps me learn to be a better student and person

- Situation: Football injury

- Challenge: Friends distant, teachers don’t know how to help, football is gone for me

- Turning point: Starting to like learning in Ms. Brady’s history class; meeting Christina and her friends

- My reactions: Reading poetry; finding shared interest in poetry with Christina; spending more time studying and with people different from me

- Insight: They taught me compassion and opened my eyes to a different lifestyle; even though I still can’t play football, I’m starting a new game

Brainstorm creative insights or story arcs

Regardless of your essay’s structure, try to craft a surprising story arc or original insights, especially if you’re writing about a common topic.

Never exaggerate or fabricate facts about yourself to seem interesting. However, try finding connections in your life that deviate from cliché storylines and lessons.

| Common insight | Unique insight |

|---|---|

| Making an all-state team → outstanding achievement | Making an all-state team → counting the cost of saying “no” to other interests |

| Making a friend out of an enemy → finding common ground, forgiveness | Making a friend out of an enemy → confront toxic thinking and behavior in yourself |

| Choir tour → a chance to see a new part of the world | Choir tour → a chance to serve in leading younger students |

| Volunteering → learning to help my community and care about others | Volunteering → learning to be critical of insincere resume-building |

| Turning a friend in for using drugs → choosing the moral high ground | Turning a friend in for using drugs → realizing the hypocrisy of hiding your secrets |

Admissions officers read thousands of essays each year, and they typically spend only a few minutes reading each one. To get your message across, your introduction , or hook, needs to grab the reader’s attention and compel them to read more..

Avoid starting your introduction with a famous quote, cliché, or reference to the essay itself (“While I sat down to write this essay…”).

While you can sometimes use dialogue or a meaningful quotation from a close family member or friend, make sure it encapsulates your essay’s overall theme.

Find an original, creative way of starting your essay using the following two methods.

Option 1: Start with an intriguing hook

Begin your essay with an unexpected statement to pique the reader’s curiosity and compel them to carefully read your essay. A mysterious introduction disarms the reader’s expectations and introduces questions that can only be answered by reading more.

Option 2: Start with vivid imagery

Illustrate a clear, detailed image to immediately transport your reader into your memory. You can start in the middle of an important scene or describe an object that conveys your essay’s theme.

A college application essay allows you to be creative in your style and tone. As you draft your essay, try to use interesting language to enliven your story and stand out .

Show, don’t tell

“Tell” in writing means to simply state a fact: “I am a basketball player.” “ Show ” in writing means to use details, examples, and vivid imagery to help the reader easily visualize your memory: “My heart races as I set up to shoot一two seconds, one second一and score a three-pointer!”

First, reflect on every detail of a specific image or scene to recall the most memorable aspects.

- What are the most prominent images?

- Are there any particular sounds, smells, or tastes associated with this memory?

- What emotion or physical feeling did you have at that time?

Be vulnerable to create an emotional response

You don’t have to share a huge secret or traumatic story, but you should dig deep to express your honest feelings, thoughts, and experiences to evoke an emotional response. Showing vulnerability demonstrates humility and maturity. However, don’t exaggerate to gain sympathy.

Use appropriate style and tone

Make sure your essay has the right style and tone by following these guidelines:

- Use a conversational yet respectful tone: less formal than academic writing, but more formal than texting your friends.

- Prioritize using “I” statements to highlight your perspective.

- Write within your vocabulary range to maintain an authentic voice.

- Write concisely, and use the active voice to keep a fast pace.

- Follow grammar rules (unless you have valid stylistic reasons for breaking them).

You should end your college essay with a deep insight or creative ending to leave the reader with a strong final impression. Your college admissions essay should avoid the following:

- Summarizing what you already wrote

- Stating your hope of being accepted to the school

- Mentioning character traits that should have been illustrated in the essay, such as “I’m a hard worker”

Here are two strategies to craft a strong conclusion.

Option 1: Full circle, sandwich structure

The full circle, or sandwich, structure concludes the essay with an image, idea, or story mentioned in the introduction. This strategy gives the reader a strong sense of closure.

In the example below, the essay concludes by returning to the “museum” metaphor that the writer opened with.

Option 2: Revealing your insight

You can use the conclusion to show the insight you gained as a result of the experiences you’ve described. Revealing your main message at the end creates suspense and keeps the takeaway at the forefront of your reader’s mind.

Revise your essay before submitting it to check its content, style, and grammar. Get feedback from no more than two or three people.

It’s normal to go through several rounds of revision, but take breaks between each editing stage.

Also check out our college essay examples to see what does and doesn’t work in an essay and the kinds of changes you can make to improve yours.

Respect the word count

Most schools specify a word count for each essay , and you should stay within 10% of the upper limit.

Remain under the specified word count limit to show you can write concisely and follow directions. However, don’t write too little, which may imply that you are unwilling or unable to write a thoughtful and developed essay.

Check your content, style, and grammar

- First, check big-picture issues of message, flow, and clarity.

- Then, check for style and tone issues.

- Finally, focus on eliminating grammar and punctuation errors.

Get feedback

Get feedback from 2–3 people who know you well, have good writing skills, and are familiar with college essays.

- Teachers and guidance counselors can help you check your content, language, and tone.

- Friends and family can check for authenticity.

- An essay coach or editor has specialized knowledge of college admissions essays and can give objective expert feedback.

The checklist below helps you make sure your essay ticks all the boxes.

College admissions essay checklist

I’ve organized my essay prompts and created an essay writing schedule.

I’ve done a comprehensive brainstorm for essay topics.

I’ve selected a topic that’s meaningful to me and reveals something different from the rest of my application.

I’ve created an outline to guide my structure.

I’ve crafted an introduction containing vivid imagery or an intriguing hook that grabs the reader’s attention.

I’ve written my essay in a way that shows instead of telling.

I’ve shown positive traits and values in my essay.

I’ve demonstrated self-reflection and insight in my essay.

I’ve used appropriate style and tone .

I’ve concluded with an insight or a creative ending.

I’ve revised my essay , checking my overall message, flow, clarity, and grammar.

I’ve respected the word count , remaining within 10% of the upper word limit.

Congratulations!

It looks like your essay ticks all the boxes. A second pair of eyes can help you take it to the next level – Scribbr's essay coaches can help.

Colleges want to be able to differentiate students who seem similar on paper. In the college application essay , they’re looking for a way to understand each applicant’s unique personality and experiences.

Your college essay accounts for about 25% of your application’s weight. It may be the deciding factor in whether you’re accepted, especially for competitive schools where most applicants have exceptional grades, test scores, and extracurricular track records.

A standout college essay has several key ingredients:

- A unique, personally meaningful topic

- A memorable introduction with vivid imagery or an intriguing hook

- Specific stories and language that show instead of telling

- Vulnerability that’s authentic but not aimed at soliciting sympathy

- Clear writing in an appropriate style and tone

- A conclusion that offers deep insight or a creative ending

While timelines will differ depending on the student, plan on spending at least 1–3 weeks brainstorming and writing the first draft of your college admissions essay , and at least 2–4 weeks revising across multiple drafts. Don’t forget to save enough time for breaks between each writing and editing stage.

You should already begin thinking about your essay the summer before your senior year so that you have plenty of time to try out different topics and get feedback on what works.

Most college application portals specify a word count range for your essay, and you should stay within 10% of the upper limit to write a developed and thoughtful essay.

You should aim to stay under the specified word count limit to show you can follow directions and write concisely. However, don’t write too little, as it may seem like you are unwilling or unable to write a detailed and insightful narrative about yourself.

If no word count is specified, we advise keeping your essay between 400 and 600 words.

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- What Do Colleges Look For in an Essay? | Examples & Tips

- College Essay Format & Structure | Example Outlines

- How to Revise Your College Admissions Essay | Examples

More interesting articles

- Choosing Your College Essay Topic | Ideas & Examples

- College Essay Examples | What Works and What Doesn't

- Common App Essays | 7 Strong Examples with Commentary

- How Long Should a College Essay Be? | Word Count Tips

- How to Apply for College | Timeline, Templates & Checklist

- How to End a College Admissions Essay | 4 Winning Strategies

- How to Make Your College Essay Stand Out | Tips & Examples

- How to Research and Write a "Why This College?" Essay

- How to Write a College Essay Fast | Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Diversity Essay | Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Great College Essay Introduction | Examples

- How to Write a Scholarship Essay | Template & Example

- How to Write About Yourself in a College Essay | Examples

- Style and Tone Tips for Your College Essay | Examples

- US College Essay Tips for International Students

"I thought AI Proofreading was useless but.."

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Years Of English Study And Still Not Fluent?

Learn what you are doing wrong and how to fix it.

Our Unique 7-Day Online Video Course Shows You Exactly What You Need To Change Right Now About The Way You Are Studying English

Thank you for supporting us!

Extensive Reading for Better Fluency

Would you like to become a more fluent English speaker? Your answer is probably, “yes”. But did you know that to become more fluent, you need lots and lots of practice? And to do that, you need more contact hours with the English language. That is, you need a lot of input that you can actually understand. You know, you can be surrounded by English speakers all the time, but if you can’t understand them, then you won’t progress as quickly.

So what should you do? Well, one way to increase your contact hours with English that you can actually understand is through a practice called extensive reading . The idea is that you choose books to read that are very easy to understand, and you then read lots and lots of them. For most learners, this involves using graded readers , that is, books written using the most common English words for people who are not yet fluent at English. And if you read at a level just at or just below your actual level, then you can read easily and smoothly. Then you can focus on the actual content of what you are reading instead of the language itself.

When you can just enjoy the story, then you can forget about the language. And then guess what? You are exposing your mind to many different English patterns over and over again. And if you see a new vocabulary word, you just skip right over it and infer the meaning. You’ll see it again anyway. You don’t actually need a dictionary. You simply internalize these vocabulary words and sentence patterns. And then when you go to speak, the patterns can express themselves through your speech since you have seen them so many times. Interesting, huh?

If you want to try extensive reading, you will need to get some graded readers from the library. Some popular graded reader series are Oxford Bookworms , Cambridge English Readers , Penguin Active Reading , and so on. If your local library does not have any graded readers, then urge your librarian to purchase them. They will be a great community resource for everyone.

Let us know what you think about extensive reading.

Get Our Free 7 Day Course Now

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

This website uses Google Analytics to collect anonymous information such as the number of visitors to the site, and the most popular pages.

Keeping this cookie enabled helps us to improve our website.

Please enable Strictly Necessary Cookies first so that we can save your preferences!

This website uses the following additional cookies:

Advertising Cookies

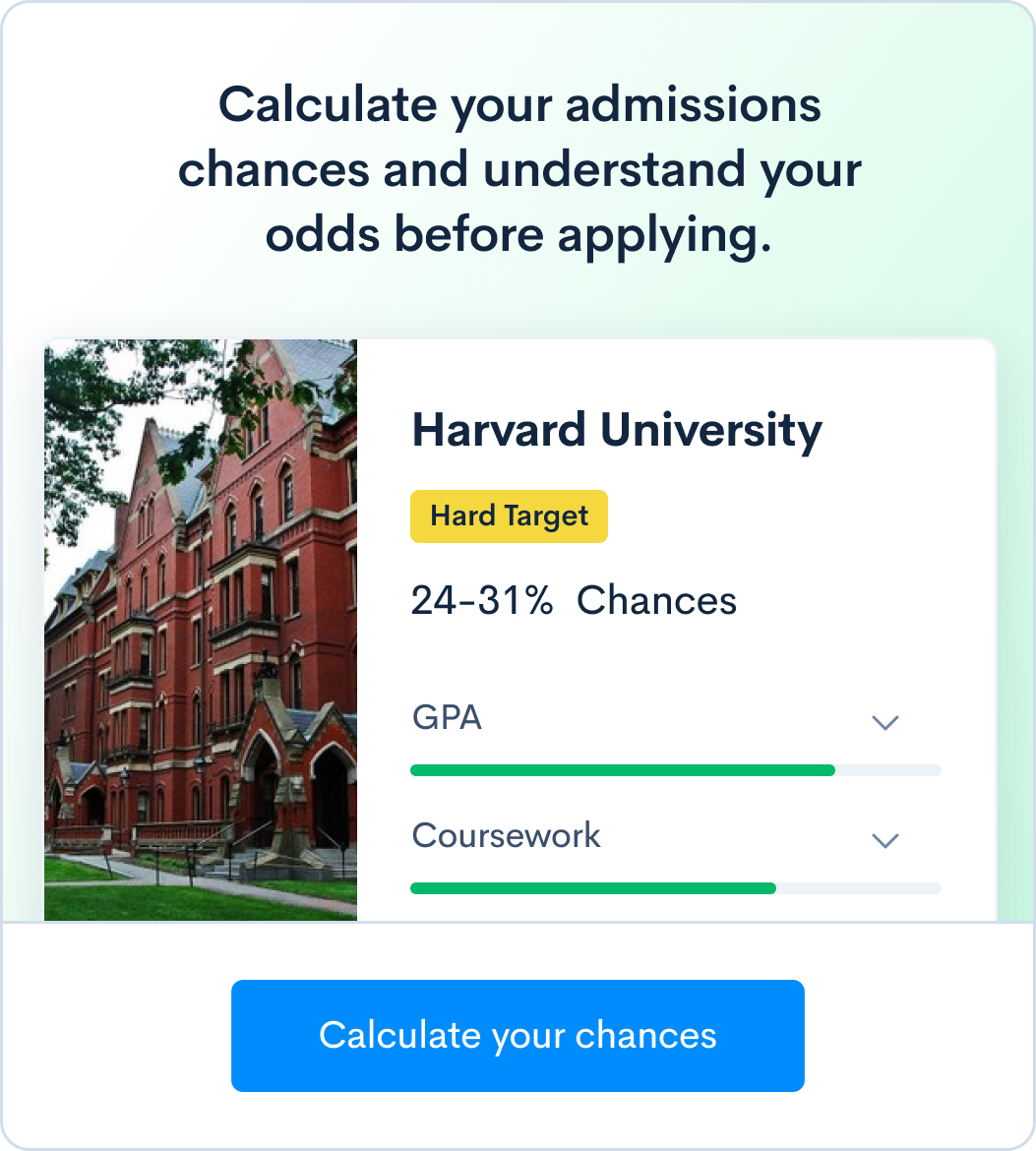

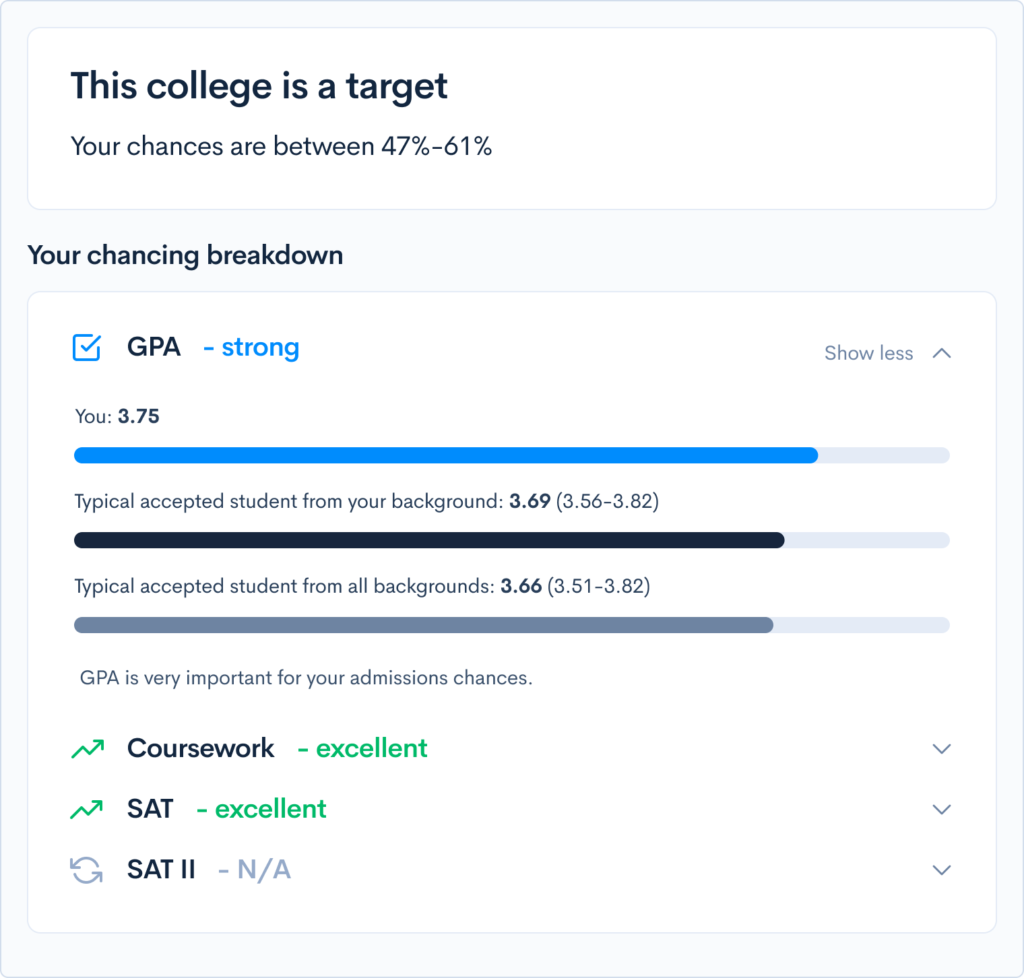

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

The 50 Best Vocab Words for the ACT Essay

When taking the ACT essay section, students have 45 minutes to write a well-reasoned argumentative essay about a given prompt. The new ACT Essay prompts tend to be about “debate” topics — two sides of an issue are presented, with no obviously “right” side. Oftentimes, these subjects carry implications for broader issues such as freedom or morality. Test-takers are expected to convey some stance on the issue and support their argument with relevant facts and analysis.

In addition to some of the more obvious categories, like grammar and structure, students’ essays are also evaluated on their mastery of the English language. One way to demonstrate such mastery is through the correct usage of advanced vocabulary words. Below are 50 above-average vocabulary words sorted by the contexts in which they could most easily be worked into an ACT essay.

(Key: N = Noun, V= Verb, Adj. = Adjective)

Context 1: Factual Support For ACT Essay

These words can easily be used when stating facts and describing examples to support one’s argument. On ACT essays, common examples are trends or patterns of human behavior, current or past events, and large-scale laws or regulations.

1. Antecedent – a precursor, or preceding event for something – N

2. Bastion – an institution/place/person that strongly maintains particular principles, attitudes, or activities – N

3. Bellwether – something that indicates a trend – N

4. Burgeon – to begin to grow or increase rapidly – V

5. Catalyst – an agent that provokes or triggers change – N

6. Defunct – no longer in existence or functioning – Adj.

7. Entrenched – characterized by something that is firmly established and difficult to change – Adj.

8. Foster – to encourage the development of something – V

9. Galvanize – to shock or excite someone into taking action – V

10. Impetus – something that makes a process or activity happen or happen faster – N

11. Inadvertent – accidental or unintentional – Adj.

12. Incessant – never ending; continuing without pause – Adj.

13. Inflame – to provoke or intensify strong feelings in someone – V

14. Instill – to gradually but firmly establish an idea or attitude into a person’s mind – V

15. Lucrative – having a large reward, monetary or otherwise – Adj.

16. Myriad – countless or extremely large in number – Adj.

17. Precipitate – to cause something to happen suddenly or unexpectedly – V

18. Proponent – a person who advocates for something – N

19. Resurgence – an increase or revival after a period of limited activity – N

20. Revitalize – to give something new life and vitality – V

21. Ubiquitous – characterized by being everywhere; widespread – Adj.

22. Watershed – an event or period that marks a turning point – N

How do your standardized test scores affect your chances?

Find out with our free Chancing Engine, which uses your standardized test scores, GPA, extracurriculars, and more to determine your real chances of admission.

Context 2: Analysis

These words can often be used when describing common patterns between examples or casting some form of opinion or judgement.

23. Anomaly – deviation from the norm – N

24. Automaton – a mindless follower; someone who acts in a mechanical fashion – N

25. Belie – to fail to give a true impression of something – V

26. Cupidity – excessive greed – Adj.

27. Debacle – a powerful failure; a fiasco – N

28. Demagogue – a political leader or person who looks for support by appealing to prejudices instead of using rational arguments – N

29. Deter – to discourage someone from doing something by making them doubt or fear the consequences – V

30. Discredit – to harm the reputation or respect for someone – V

31. Draconian – characterized by strict laws, rules and punishments – Adj.

32. Duplicitous – deliberately deceitful in speech/behavior – Adj.

33. Egregious – conspicuously bad; extremely evil; monstrous and outrageous – Adj.

34. Exacerbate – to make a situation worse – V

35. Ignominious – deserving or causing public disgrace or shame – Adj.

36. Insidious – proceeding in a subtle way but with harmful effects – Adj.

37. Myopic – short-sighted; not considering the long run – Adj.

38. Pernicious – dangerous and harmful – Adj.

39. Renegade – a person who betrays an organization, country, or set of principles – N

40. Stigmatize – to describe or regard as worthy of disgrace or disapproval – V

41. Superfluous – unnecessary – Adj.

42. Venal – corrupt; susceptible to bribery – Adj.

43. Virulent – extremely severe or harmful in its effects – Adj.

44. Zealot – a person who is fanatical and uncompromising in pursuit of their religious, political, or other ideals – N

Want to see your chances at the schools on your list? Use our free chancing calculator to see your chances based on ACT score, GPA, extracurriculars, and more.

C ontext 3: Thesis and Argument

These words are appropriate for taking a stance on controversial topics, placing greater weight on one or the other end of the spectrum, usually touching on abstract concepts, and/or related to human nature or societal issues.

45. Autonomy – independence or self governance; the right to make decisions for oneself – N

46. Conundrum – a difficult problem with no easy solution – N

47. Dichotomy – a division or contrast between two things that are presented as opposites or entirely different – N

48. Disparity – a great difference between things – N

49. Divisive – causing disagreement or hostility between people – Adj.

50. Egalitarian – favoring social equality and equal rights – Adj.

Although it’s true that vocabulary is one of the lesser criteria by which students’ ACT essays are graded, the small boost it may give to a student’s score could be the difference between a good score and a great score. For those who are already confident in their ability to create and support a well-reasoned argument but still want to go the extra mile, having a few general-purpose, impressive-sounding vocabulary words up one’s sleeve is a great way to tack on even more points.