This Huge Study Is The Best Evidence Yet That Your Personality Changes Over Time

You might be fundamentally you for your entire life, but don't expect your personality to stay the same.

That's according to a major study of 50,000 people over the course of several decades, which found the traditional notion of personality – as fixed and unchanged after adolescence – is mostly untrue.

People included in the sample showed a common trend as they got older, declining in all five major personality metrics that psychologists have come to trust as the gold-standard.

Psychologists have been writing about personality for the better part of three centuries, beginning most famously with William James' 1890 text The Principles of Psychology . Relying on personal observation, James wrote that personality is "set like plaster" after age 30.

In the century or so since The Principles of Psychology was published, psychologists have come to rethink personality in bits and pieces.

In 2003, the American Psychological Association observed the changing consensus among members of the field: Personality was beginning to look more like it was ever-evolving, even through old age.

The latest study combined 14 longitudinal studies that gathered information about people's personalities, including data from the United States, Europe, and Scandinavia.

Many of the subjects had already reached adulthood, which gave the researchers unique perspective on personality changes. Typically, studies skew toward young people.

Of the Big Five personality traits – neuroticism, conscientiousness, openness, extroversion, and agreeableness – all five showed major fluctuations across individual participants' lives.

And all traits, except for agreeableness, showed downward trends of about 1-2 percent per decade across the overall studies.

In part, this suggested to researchers that the so-called "Dolce Vita" effect was real – that when people age, they enjoy fewer social responsibilities and can do more of what they want.

People can be less neurotic about conforming to the group, less open to trying new things in order to savour the classics, less conscientious as they become more selfish, and less extroverted as they keep more to themselves.

These trends appeared at nearly every stage of the 14 studies and held mostly steady across different geographical regions. Some regions deviated from the norm, however.

People from the US showed considerably larger declines in extroversion as they aged, which signalled to the investigators that they were especially done with with seeming social.

People aren't set in plaster, as William James asserted 128 years ago. They're more like clay, constantly getting moulded by their changing circumstances.

This article was originally published by Business Insider .

More From Forbes

New research identifies personality types that are naturally good at self-care.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Extraverts have the upper hand when it comes to caring for their basic psychological needs.

A new study published in the Journal of Research in Personality identifies the types of people who may be best equipped to satisfy their basic psychological needs, such as the need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

The researchers, led by Martina Pocrnic of the University of Zagreb in Croatia, found the traits of extraversion, conscientiousness, and agreeableness to be most strongly associated with self-care behaviors and routines — and that people who possessed these traits were most likely to care for their basic needs.

“Although basic psychological needs are a human universal, there are individual differences in the degree to which people satisfy those needs,” comments Pocrnic. “We wanted to investigate how individual differences in the satisfaction of basic psychological needs arise and how they are related to differences in personality.”

To study this, the researchers asked 668 Croatian adults to complete a series of psychological questionnaires that measured various dimensions of need satisfaction and personality. Specifically, they asked respondents to self-report on the following dimensions of psychological needs:

- Sense of competence — i.e., feeling effective and having opportunities to express and expand one’s abilities

- Sense of autonomy — i.e., having the ability to make one’s own choices in life

- Sense of relatedness — i.e., feeling connected and sharing a sense of belonging with others

Best Travel Insurance Companies

Best covid-19 travel insurance plans.

The researchers used the “Big Five” model of personality, which divides personality into five distinct dimensions (agreeableness, neuroticism, conscientiousness, openness, and extraversion), to measure respondents’ personality traits.

They found extraversion and neuroticism to be most predictive of the three dimensions of psychological need satisfaction. Specifically, higher levels of extraversion promoted higher levels of need satisfaction while higher levels of neuroticism promoted lower levels of need satisfaction.

“It was a surprise to us that neuroticism and extraversion had the biggest correlations with all three needs — autonomy, competence, and relatedness,” says Pocrnic. “We had expected that all three needs would show significant relationships with at least one trait, but we had not expected that extraversion and neuroticism would be the crucial traits for all three needs. That was certainly the most interesting finding for us.”

They also found conscientiousness to be important when satisfying the need for competence and agreeableness to play a role in satisfying the need for autonomy and relatedness.

Pocrnic offers the following example to explain how personality traits impact our ability to satisfy our basic psychological needs.

“Someone with a high level of extraversion is likely to have a wide social network, is more prone to initiate contact with other people, spend leisure time socializing, and accept invitations to social events,” says Pocrnic. “All of this can lead to situations that satisfy the need for relatedness. Another example is a student who has a high level of conscientiousness. Because of that personality trait, he/she is hardworking, organized, and highly self-disciplined and likely to study regularly, achieve better grades, and consequently satisfy the need for competence.”

Importantly, the authors point out that personality traits are not fixed and that everyone has an opportunity to better meet their basic psychological needs.

“Although personality traits by definition are relatively stable over time, they are not set in stone,” says Pocrnic. “If we try to lower our levels of neuroticism through practicing meditation or mindfulness, for example, it could lead to greater satisfaction of our psychological needs.”

In the future, the authors hope to examine how a more nuanced analysis of personality might influence their results.

“It would be interesting to find out which specific facets of neuroticism are more important for low levels of need satisfaction,” says Pocrnic. “Is it anxiety, depression, anger, or perhaps vulnerability?”

A full interview with Martina Pocrnic discussing her new research can be found here: Which personality traits facilitate self-care?

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

July 1, 2009

What Your Choice of Words Says about Your Personality

A language analysis program reveals personality, mental health and intent by counting and categorizing words

By Jan Dönges

NO ONE DOUBTS that the words we write or speak are an expression of our inner thoughts and personalities. But beyond the meaningful content of language, a wealth of unique insights into an author’s mind are hidden in the style of a text—in such elements as how often certain words and word categories are used, regardless of context.

It is how an author expresses his or her thoughts that reveals character, asserts social psychologist James W. Pennebaker of the University of Texas at Austin. When people try to present themselves a certain way, they tend to select what they think are appropriate nouns and verbs, but they are unlikely to control their use of articles and pronouns. These small words create the style of a text, which is less subject to conscious manipulation.

Pennebaker’s statistical analyses have shown that these small words may hint at the healing progress of patients and give us insight into the personalities and changing ideals of public figures, from political candidates to terrorists. “Virtually no one in psychology has realized that low-level words can give clues to large-scale behaviors,” says Pennebaker, who, with colleagues, developed a computer program that analyzes text, called Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC, pronounced “Luke”). The software has been used to examine other speech characteristics as well, tallying up nouns and verbs in hundreds of categories to expose buried patterns.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Character Count Most recently, Pennebaker and his colleagues used LIWC to analyze the candidates’ speeches and interviews during last fall’s presidential election. The software counts how many times a speaker or author uses words in specific categories, such as emotion or perception, and words that indicate complex cognitive processes. It also tallies up so-called function words such as pronouns, articles, numerals and conjunctions. Within each of these major categories are subsets: Are there more mentions of sad or happy emotions? Does the speaker prefer “I” and “me” to “us” and “we”? LIWC answers these quantitative questions; psychologists must then figure out what the numbers mean. Before LIWC was developed in the mid-1990s, years of psychological research in which people counted words by hand established robust connections between word usage and psychological states or character traits

The political candidates, for example, showed clear differences in their speaking styles. John McCain tended to speak directly and personally to his constituency, using a vocabulary that was both emotionally loaded and impulsive. Barack Obama, in contrast, made frequent use of causal relationships, which indicated more complex thought processes. He also tended to be more vague than his Republican rival. Pennebaker’s team has posted a far more in-depth breakdown, including analyses of the vice presidential candidates, at www.wordwatchers.wordpress.com .

Skeptics of LIWC’s usefulness point out that many of these characteristics of McCain’s and Obama’s speeches could be gleaned without the use of a computer program. When the subjects of analysis are not accessible, however, LIWC may provide a unique insight. Such was the case with Pennebaker’s study of al Qaeda communications. In 2007 he and several co-workers, under contract with the FBI, analyzed 58 texts by Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, bin Laden’s second in command.

The comparison showed how much pronouns are able to disclose. For example, between 2004 and 2006 the frequency with which al-Zawahiri used the word “I” tripled, whereas it remained constant in bin Laden’s writings. “Normally, higher rates of ‘I’ words correspond with feelings of insecurity, threat and defensiveness. Closer inspection of his ‘I’ use in context tends to confirm this,” Pennebaker says.

Other studies have shown that words that are used to express balance or nuance (“except,” “but,” and so on) are associated with higher cognitive complexity, better grades and even the truthfulness with which facts are reported. For bin Laden, analysis showed that the thought processes in his texts had reached a higher level over the years, whereas those of his lieutenant had stagnated.

Healing Words This power of statistical analysis to quantify a person’s changing language use over time is a key advantage to programs such as LIWC. In 2003 Pennebaker and statistician R. Sherlock Campbell, now at Yale University, used a statistical tool called latent semantic analysis (LSA) to study the diary entries of trauma patients from three earlier studies, looking for text characteristics that had changed in patients who were convalescing and met rarely with their physician. Again, the researchers showed that content was unimportant. The factor that was most clearly associated with recovery was the use of pronouns. Patients whose writings changed perspective from day to day were less likely to seek medical treatment during the follow-up period.

It may be that patients who describe their situation both from their own viewpoint and from the perspective of others recover more quickly from traumatic experiences—a variation on the already well-established idea that writing about negative experiences is therapeutic. Or perhaps the LSA simply detected the patients’ recovery as reflected by their writing but not brought about by it—in that case, programs such as LIWC could aid doctors in diagnosing illness and gauging treatment progression. Researchers are currently investigating many other patient groups, including those with cancer, mental illness and suicidal tendencies, using LIWC to uncover clues about their emotional well-being and their mental state.

Although the statistical study of language is relatively young, it is clear that analyzing patterns of word use and writing style can lead to insights that would otherwise remain hidden. Because these tools offer predictions based on probability, however, such insights will never be definitive. “In the final analysis, our situation is much like that of economists,” Pennebaker says. “It’s too early to come up with a standardized analysis. But at the end of the day, we all are making educated guesses, the same way economists can understand, explain and predict economic ups and downs.”

He Said, She Said The way we write and speak can reveal volumes about our identity and character. Here is a sampling of the many variables that can be detected in our use of style-related words such as pronouns and articles:

Gender : In general, women tend to use more pronouns and references to other people. Men are more likely to use articles, prepositions and big words.

Age : As people get older, they typically refer to themselves less, use more positive-emotion words and fewer negative-emotion words, and use more future-tense verbs and fewer past-tense verbs.

Honesty : When telling the truth, people are more likely to use first-person singular pronouns such as “I.” They also use exclusive words such as “except” and “but.” These words may indicate that a person is making a distinction between what they did do and what they did not do—liars often do not deal well with such complex constructions.

Depression and suicide risk : Public figures and published poets use more first-person singular pronouns when they are depressed or suicidal, possibly indicating excessive self-absorption and social isolation.

Reaction to trauma : In the days and weeks after a cultural upheaval, people use “I” less and “we” more, suggesting a social bonding effect.

Note: This article was originally printed with the title, "You Are What You Say."

Jan Dönges is an editor at Spektrum der Wissenschaft .

Personality Assessments: 10 Best Inventories, Tests, & Methods

Perhaps they respond differently to news or react differently to your feedback. They voice different opinions and values and, as such, behave differently.

If you respond with a resounding yes, we understand the challenges you face.

As more and more organizations diversify their talent, a new challenge emerges of how to get the best out of employees and teams of all personality configurations.

In this article, we embark on a whistle-stop tour of the science of personality, focusing on personality assessments to measure clients’ and employees’ character plus the benefits of doing so, before rounding off with practical tools for those who want to bolster their professional toolkits.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Strengths Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help your clients or employees realize their unique potential and create a life that feels energizing and authentic.

This Article Contains

What are personality assessments in psychology, 4 methods and types of personality assessments, 7 evidence-based inventories, scales, and tests.

- Helpful Tools & Questions

Fascinating Books About Personality Assessments

Resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message.

Personality is a tricky concept to define in concrete terms, and this is reflected both in the number of personality theories that exist and the lack of consensus among personality psychologists.

However, for this article, we can think of personality as the totality of one’s behavioral patterns and subjective experiences (Kernberg, 2016).

All individuals have a constellation of traits and experiences that make them unique yet simultaneously suggest that there are some generalizable or distinct qualities inherent in all humans.

In psychology, we are interested in understanding how traits and qualities that people possess cluster together and the extent to which these vary across and within individuals.

Now, it’s all very well and good knowing that personality exists as a concept and that your employees and clients differ in their groupings of traits and subjective experiences, but how can you apply this information to your professional work with them?

This is where measuring and assessing personality comes into play. Like most psychological concepts, researchers want to show that theoretical knowledge can be useful for working life and brought to bear in the real world.

For example, knowing a client’s or employee’s personality can be key to setting them up for success at work and pursuing and achieving work-related goals. But we first need to identify or assess personality before we can help others to reap these benefits.

Personality assessments are used for several reasons.

First, they can provide professionals with an opportunity to identify their strengths and reaffirm their sense of self. It is no coincidence that research on strengths is so popular or that strengths have such a prominent place in the working world. People like to know who they are, and they want to capitalize on the qualities and traits they possess.

Second, personality assessments can provide professionals with a social advantage by helping them to understand how they are perceived by others such as colleagues, managers, and stakeholders — the looking glass self (Cooley, 1902).

In the sections below, we will explore different personality assessments and popular evidence-based scales.

1. Self-report assessments

Self-reports are one of the most widely used formats for psychometric testing. They are as they sound: reports or questionnaires that a client or employee completes themselves (and often scores themselves).

Self-report measures can come in many formats. The most common are Likert scales where individuals are asked to rate numerically (from 1 to 7 for example) the extent to which they feel that each question describes their thoughts, feelings, or behaviors.

These types of assessments are popular because they are easy to distribute and complete, they are often cost effective, and they can provide helpful insights into behavior. Self-reports can be completed in both personal and professional settings and can be particularly helpful in a coaching practice, for example.

However, they also have downsides to be wary of, including an increase in unconscious biases such as the social desirability bias (i.e., the desire to answer “correctly”). They can also be prone to individuals not paying attention, not answering truthfully, or not fully understanding the questions asked.

Such issues can lead to an inaccurate assessment of personality.

However, if you are a professional working with clients in any capacity, it is advised to first try out any self-report measure before suggesting them to clients. In this way, you can gauge for yourself the usefulness and validity of the measure.

2. Behavioral observation

Another useful method of personality assessment is behavioral observation. This method entails someone observing and documenting a person’s behavior.

While this method is more resource heavy in terms of time and requires an observer (preferably one who is experienced and qualified in observing and coding the behavior), it can be useful as a complementary method employed alongside self-reports because it can provide an external corroboration of behavior.

Alternatively, behavioral observation can fail to corroborate self-report scores, raising the question of how reliably an individual has answered their self-report.

3. Interviews

Interviews are used widely from clinical settings to workplaces to determine an individual’s personality. Even a job interview is a test of behavioral patterns and experiences (i.e., personality).

During such interviews, the primary aim is to gather as much information as possible by using probing questions. Responses should be recorded, and there should be a standardized scoring system to determine the outcome of the interview (for example, whether the candidate is suitable for the role).

While interviews can elicit rich data about a client or employee, they are also subject to the unconscious biases of the interviewers and can be open to interpretation if there is no method for scoring or evaluating the interviewee.

4. Projective tests

These types of tests are unusual in that they present individuals with an abstract or vague object, task, or activity and require them to describe what they see. The idea here is that the unfiltered interpretation can provide insight into the person’s psychology and way of thinking.

A well-known example of a projective test is the Rorschach inkblot test. However, there are limitations to projective tests due to their interpretative nature and the lack of a consistent or quantifiable way of coding or scoring individuals’ responses.

Download 3 Free Strengths Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to discover and harness their unique strengths.

Download 3 Free Strengths Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Personality assessments can be used in the workplace during recruitment to gauge whether someone would be a good fit for a job or organization and to help determine job performance, career progression, and development.

Below, we highlight a few commonly used inventories and tests for such career assessments.

1. The Hogan personality inventory (HPI)

The Hogan personality inventory (Hogan & Hogan, 2002) is a self-report personality assessment created by Robert Hogan and Joyce Hogan in the late 1970s.

It was originally based on the California Personality Inventory (Gough, 1975) and also draws upon the five-factor model of personality. The five-factor model of personality suggests there are five key dimensions of personality: openness to experience , conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (Digman, 1990).

The Hogan assessment comprises 206 items across seven different scales that measure and predict social behavior and social outcomes rather than traits or qualities , as do other popular personality measures.

These seven scales include:

- Sociability

- Interpersonal sensitivity

- Inquisitiveness

- Learning approach

The HPI’s primary use is within organizations to help with recruitment and the development of leaders. It is a robust scale with over 40 years of evidence to support it, and the scale itself takes roughly 15–20 minutes to complete (Hogan Assessments, n.d.).

2. DISC test

The DISC test of personality developed by Merenda and Clarke (1965) is a very popular personality self-assessment used primarily within the corporate world. It is based on the emotional and behavioral DISC theory (Marston, 1928), which measures individuals on four dimensions of behavior:

The self-report comprises 24 questions and takes roughly 10 minutes to complete. While the test is simpler and quicker to complete than other popular tests (e.g., the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator), it has been subject to criticism regarding its psychometric properties.

3. Gallup – CliftonStrengths™ Assessment

Unlike the DISC test, the CliftonStrengths™ assessment , employed by Gallup and based on the work of Marcus Buckingham and Don Clifton (2001), is a questionnaire designed specifically to help individuals identify strengths in the workplace and learn how to use them.

The assessment is a self-report Likert scale comprising 177 questions and takes roughly 30 minutes to complete. Once scored, the assessment provides individuals with 34 strength themes organized into four key domains:

- Strategic thinking

- Influencing

- Relationship building

The scale has a solid theoretical and empirical grounding, making it a popular workplace assessment around the world.

4. NEO-PI-R

The NEO-PI-R (Costa & McCrae, 2008) is a highly popular self-report personality assessment based on Allport and Odbert’s (1936) trait theory of personality.

With good reliability, this scale has amassed a large evidence base, making it an appealing inventory for many. The NEO-PI-R assesses an individual’s strengths, talents, and weaknesses and is often used by employers to identify suitable candidates for job openings.

It uses the big five factors of personality (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism) and also includes an additional six subcategories within the big five, providing a detailed breakdown of each personality dimension.

The scale itself comprises 240 questions that describe different behaviors and takes roughly 30–40 minutes to complete. Interestingly, this inventory can be administered as a self-report or, alternatively, as an observational report, making it a favored assessment among professionals.

5. Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ)

The EPQ is a personality assessment developed by personality psychologists Hans Eysenck and Sybil Eysenck (1975).

The scale results from successive revisions and improvements of earlier scales: the Maudsley Personality Inventory (Eysenck 1959) and Eysenck Personality Inventory (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1964).

The aim of the EPQ is to measure the three dimensions of personality as espoused by Eysenck’s psychoticism–extraversion–neuroticism theory of personality The scale itself uses a Likert format and was revised and shortened in 1992 to include 48 items (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1992).

This is a generally useful scale; however, some researchers have found that there are reliability issues with the psychoticism subscale, likely because this was a later addition to the scale.

6. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)

The MMPI (Hathaway & McKinley, 1943) is one of the most widely used personality inventories in the world and uses a true/false format of questioning.

It was initially designed to assess mental health problems in clinical settings during the 1940s and uses 10 clinical subscales to assess different psychological conditions.

The inventory was revised in the 1980s, resulting in the MMPI-2, which comprised 567 questions, and again in 2020, resulting in the MMPI-3, which comprises a streamlined 338 questions.

While the revised MMPI-3 takes a lengthy 35–50 minutes to complete, it remains popular to this day, particularly in clinical settings, and enables the accurate capture of aspects of psychopathy and mental health disturbance. The test has good reliability but must be administered by a professional.

7. 16 Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF)

The 16PF (Cattell et al., 1970) is another rating scale inventory used primarily in clinical settings to identify psychiatric disorders by measuring “normal” personality traits.

Cattell identified 16 primary personality traits, with five secondary or global traits underneath that map onto the big five factors of personality.

These include such traits as warmth, reasoning, and emotional stability, to name a few. The most recent version of the questionnaire (the fifth edition) comprises 185 multiple-choice questions that ask about routine behaviors on a 10-point scale and takes roughly 35–50 minutes to complete.

The scale is easy to administer and well validated but must be administered by a professional.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

Helpful Tools & Questions

In addition to the collection of science-based interventions, we also have to mention a controversial but well-known personality assessment tool: Myers-Briggs.

We share two informative videos on this topic and then move on to a short collection of questions that can be used for career development.

1. Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)

A mother and daughter team developed the MBTI in the 1940s during the Second World War. The MBTI comprises 93 questions that aim to measure an individual on four different dimensions of personality:

- Introversion/extraversion

- Sensing/ intuition

- Thinking/feeling

- Judging/perceiving

The test provides individuals with a type of personality out of a possible 16 combinations. Whilst this test is a favorite in workplaces, there are serious criticisms leveled at how the scale was developed and the lack of rigorous evidence to support its use.

For more information on the MBTI, you might enjoy the below videos:

We recommend that if you employ MBTI, be mindful of its scientific deficiencies and support your personality testing further by completing an additional validated scale.

10 Career development questions

- Tell me about what inspires you. What gets you out of bed in the morning?

- Tell me about your vision for your career/life.

- What aspects of your role do you love? What aspects do you struggle with?

- Tell me about a time where you used your strengths to achieve a positive outcome.

- Are there any healthy habits you want to build into your work life?

- Describe your perfect working day. What would it look like?

- Tell me about your fears.

- What do you value most about your job?

- What goals are you currently working toward?

- How would your work colleagues describe you?

If you are interested in learning more about personality and personality assessments, the following three books are an excellent place to start.

These books were chosen because they give an excellent overview of what personality is and how it can be measured. They also illuminate some issues with personality assessments. They provide a good grounding for any professional looking to implement personality assessments in the workplace.

1. Mindset: Changing the Way You Think to Fulfil Your Potential – Carol Dweck

Enter Dr. Carol Dweck and several decades of psychological research she has conducted on motivation and personality.

The main thesis of the book is to explore the idea that people can have either a fixed or growth mindset (i.e., beliefs we hold about ourselves and the world around us). Adopting a growth mindset can be a critical determinant of outcomes such as performance and academic success.

Find the book on Amazon .

2. The Personality Brokers: The Strange History of Myers-Briggs and the Birth of Personality Testing – Merve Emre

If you are interested in the dark side of psychology assessments, this is the book for you.

This book explores how the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator was developed and discusses the questionable validity of the scale despite its widespread popularity in the corporate world.

While many assessments can be helpful for self-reflecting on your own behavior, The Personality Brokers delve into the murky side of how psychological concepts can be used for monetary gains, even when evidence is lacking or disputed.

3. Psychological Types – Carl Jung

This is an excellent book from one of history’s most influential psychologists: Carl Jung.

The book focuses most on extraversion and introversion as the two key types of personality and also discusses the limitations of categorizing individuals into “types” of personality.

For those interested in the science of personality and who prefer a slightly heavier, academic read, this book is for you.

Interested in supplementing your professional life by exploring personality types? Here at PositivePsychology.com, we have several highly useful resources.

Maximizing Strengths Masterclass©

While strengths finding is a distinct and popular topic within positive psychology, we can draw parallels between strengths research and some conceptualizations of personality.

The Maximizing Strengths Masterclass© is designed to help clients reach their potential by looking at their strengths and what energizes them and helping them delve into their authentic selves. As a six-module coaching package, it includes 19 videos, a practitioner handbook, slide presentations, and much more.

Recommended Reading

For more information on personality psychology and personality assessments, check out the following related articles.

- Big Five Personality Traits: The OCEAN Model Explained

- Personality & Character Traits: The Good, the Bad, the Ugly

- Personal Strengths Defined (+ List of 92 Personal Strengths)

17 Career exercises

Designed to help people use their personality and strengths at work, this collection of 17 work and career coaching exercises is grounded in scientific evidence. The exercises help individuals and clients identify areas for career growth and development. Some of these exercises include:

- Achievement Story Chart your successes at work, take time to reflect on your achievements, and identify how to use your strengths for growth.

- Job Analysis Through a Strengths Lens Identify your strengths and opportunities to use them when encountering challenges at work.

- Job Satisfaction Wheel Complete the job satisfaction wheel, which measures your current levels of happiness at work across seven different dimensions.

- What Work Means to You Identify how meaningful your work is to you by assessing your motivational orientation toward work (i.e., whether it is something you are called to and that aligns with your sense of self).

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others develop their strengths, this collection contains 17 strength-finding tools for practitioners. Use them to help others better understand and harness their strengths in life-enhancing ways.

17 Exercises To Discover & Unlock Strengths

Use these 17 Strength-Finding Exercises [PDF] to help others discover and leverage their unique strengths in life, promoting enhanced performance and flourishing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

When managing people, it is always helpful to have insight into why they behave the way they do. The same applies to assisting someone on their career path. Having an understanding of the qualities that influence behavioral responses can improve relationships, parenting, how people work, and even goal setting.

But there are some caveats to be mindful of:

- When using self-reports, take the scores with a pinch of salt, particularly as we all operate with unconscious biases that can skew results.

- Remain open minded about our personality traits; if we are resigned to the idea that they are inherited at birth, fixed, and unchanging, we are unlikely to gain any real discernment into our own evolving identity.

- Labels can oftentimes be limiting. Trying to condense the myriad aspects of an individual into a neat “personality” category could backfire.

In the right hands, validated personality assessments are valuable tools for guiding clients on the right career path, ensuring a good job fit and building strong teams.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Strengths Exercises for free .

- Allport, G. W., & Odbert, H. S. (1936). Trait-names: A psycho-lexical study. Psychological Monographs , 47 (1), i–171.

- Buckingham, M., & Clifton, D. O. (2001). Now, discover your strengths . Simon and Schuster.

- Cattell, R. B., Eber, H. W., & Tatsuoka, M. M. (1970). Handbook for the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire . Institute for Personality and Ability Testing.

- Cooley, C. H. (1902). Human nature and the social order . Transaction.

- Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (2008). The Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) . In G. J. Boyle, G. Matthews, & D. H. Saklofske (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of personality theory and assessment, Vol. 2. Personality measurement and testing (pp. 179–198). SAGE.

- Digman, J. M. (1990). Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annual Review of Psychology , 41 (1), 417–440.

- Eysenck, H. J. (1959). Manual of the Maudsley Personality Inventory . University of London Press.

- Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1964). Manual of the Eysenck Personality Inventory . University of London Press.

- Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1975). Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire . Educational and Industrial Testing Service.

- Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1992). Manual for the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire–Revised . Educational and Industrial Testing Service.

- Gough, H. G. (1975). Manual: The California Psychological Inventory (Rev. ed.). Consulting Psychologist Press.

- Hathaway, S. R., & McKinley, J. C. (1943). The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (Rev. ed., 2nd printing). University of Minnesota Press.

- Hogan Assessments. (n.d.). About. Retrieved May 8, 2023, from https://www.hoganassessments.com/about/.

- Hogan, R., & Hogan, J. (2002). The Hogan personality inventory. In B. de Raad & M. Perugini (Eds.), Big five assessment (pp. 329–346). Hogrefe & Huber.

- Kernberg, O. F. (2016). What is personality? Journal of Personality Disorders , 30 (2), 145–156.

- Marston, W. M. (1928). Emotions of normal people . Kegan Paul Trench Trubner and Company.

- Merenda, P. F., & Clarke, W. V. (1965). Self description and personality measurement. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 21 , 52–56.

- Myers, I. B., & McCaulley, M. H. (1985). Manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator . Palo Alto Consulting Psychologists Press.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Very insightful yet easy to read article, thank you for sharing! Have you heard of the Strength Finder test from Personality Quizzes? https://www.personality-quizzes.com/strength-finder It’s a free version of Clifton Strengths (although you have to pay to see complete results). I liked the experience, may be worth updating the list!

I learned so much. This article gave me more food for thought.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Type B Personality Advantages: Stress Less, Achieve More

Type B personalities, known for their relaxed, patient, and easygoing nature, offer unique advantages in both personal and professional contexts. There are myriad benefits to [...]

Jungian Psychology: Unraveling the Unconscious Mind

Alongside Sigmund Freud, the Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961) is one of the most important innovators in the field of modern depth [...]

12 Jungian Archetypes: The Foundation of Personality

In the vast tapestry of human existence, woven with the threads of individual experiences and collective consciousness, lies a profound understanding of the human psyche. [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (52)

- Coaching & Application (39)

- Compassion (23)

- Counseling (40)

- Emotional Intelligence (21)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (18)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (16)

- Mindfulness (40)

- Motivation & Goals (41)

- Optimism & Mindset (29)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (23)

- Positive Education (36)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (16)

- Positive Parenting (14)

- Positive Psychology (21)

- Positive Workplace (35)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (29)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (42)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (54)

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 02 September 2024

The role of personality traits and online behavior in belief in fake news

- Erika L. Peter ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7063-3928 1 ,

- Peter J. Kwantes 1 ,

- Madeleine T. D’Agata 1 &

- Janani Vallikanthan 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 1126 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

The current study examines how careless online behavior and personality traits are related to the detection of fake news. We tested the relationships among accurately distinguishing between fake and real news headlines, careless online behavioral tendencies, and the HEXACO and dark triad personality traits. Poorer discernment between fake and real news headlines was associated with greater careless behavior online (i.e., greater online disinhibition, greater risky online behavior, greater engagement with strangers online, and less suspicion of others’ intentions online), as well as lower Conscientiousness, Openness, and Honesty-Humility, and greater dark triad traits. Implications for the literature as well as potential interventions to reduce susceptibility to misinformation and fake news are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

A prosocial fake news intervention with durable effects

The relation between authoritarian leadership and belief in fake news

The fingerprints of misinformation: how deceptive content differs from reliable sources in terms of cognitive effort and appeal to emotions

Introduction.

The information environment is leveraged by adversaries, criminals, and individuals to spread fake news, conspiracy theories, disinformation, and misinformation. Footnote 1 Belief in conspiracy theories can increase during times of uncertainty, often to explain things that are out of one’s control (Douglas, 2021 ; Miller, 2020 ; van Prooijen and Acker, 2015 ). Amidst the global COVID-19 pandemic, for example, conspiracy theories and misinformation about the spread, prevention, and severity of the disease proliferated (e.g., Douglas, 2021 ). Research shows that conspiratorial beliefs regarding medicine and health can have behavioral consequences. For example, holding conspiratorial beliefs about AIDS has been associated with reduced safer sex practices (Grebe and Nattrass, 2012 ). In addition, holding conspiratorial beliefs about birth control being a form of Black genocide reduced contraceptive use in African American respondents (Thorburn and Bogart, 2005 ). Further still, individuals who held more anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs, and those who were exposed to anti-vaccine conspiracy theories, were less likely to report intentions to vaccinate their children than those who did not (Jolley and Douglas, 2014 ). From the examples above, the uptake of false information can have real consequences on participation in public health measures like vaccine uptake, which has been a priority since COVID-19 vaccines became available. Endorsement of conspiracy theories about COVID-19 have even been associated with self-reported reduced participation, compliance (Earnshaw et al., 2020 ; Pummerer et al., 2022 ), and support for public health measures like handwashing, social distancing (Allington et al., 2020 ; Bierwiaczonek et al., 2020 ), mask-wearing (Romer and Jamieson, 2020 ), and intentions to become vaccinated (Earnshaw et al., 2020 ; Romer and Jamieson, 2020 ). In sum, there seems to exist a portion of the population that possesses a propensity to believe, or at least hold plausible, conspiracy theories that propagate throughout the information environment, and in response, adjust their behavior in a manner accordingly. In the following sections, we explore current work done to understand the personality factors that have been identified as diagnostic indicators of a person’s propensity to believe untrue or potentially misleading information and propose an expansion of the role of personality by including the socially aversive so-called ‘dark triad’ traits that have been examined in the literature.

The role of personality

Intuitively, whether a person is influenced by misinformation in the information environment depends on their ability to identify it as misinformation in the first place. But to what extent might personality make one more or less able to do so? While personality is traditionally assessed using the Big Five model of personality (John et al., 1991 ), for this article, we used a framework of personality that includes a sixth trait, Honesty-Humility (Ashton et al., 2014 ; Ashton and Lee, 2007 ), with the remaining five traits sharing much similarity with the Big Five. Together, they are (along with their behavioral and emotional tendencies in parentheses): Honesty-Humility (honest, sincere, fair, modest), Emotionality (vulnerable, sensitive, anxious), eXtraversion (confident, enjoy social gatherings, positive feelings), Agreeableness (peaceful, gentle, patient, agreeable), Conscientiousness (diligent, organized, planning), and Openness (curiosity, imaginativeness, depth). In what follows we provide a brief overview of work done to explore how personality is related to the ways in which a person interacts with the information environment.

Calvillo et al. ( 2021 ) reported that individuals higher on Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Openness, and lower on Extraversion, showed better accuracy in discriminating between real and fake news headlines (Calvillo et al., 2021 ). Hence, it is plausible that individuals high on these traits tend to authenticate whether headlines are true before sharing them online. Several published studies support this notion. Sampat and Raj ( 2022 ) found that individuals higher in Agreeableness and Conscientiousness had an increased tendency to vet news stories before sharing them. By contrast, they found that those higher in Extraversion and Neuroticism demonstrated an elevated tendency to share news stories online prematurely rather than vetting them. In addition, higher Agreeableness has been associated with a lower tendency to interact with suspicious Facebook posts (Buchanan and Benson, 2019 ). In sum, personality traits seem to shape how content in the information environment is regarded and treated.

While most of the existing research on personality and misinformation rely on the traditional Big Five model of personality (John et al., 1991 ), this model does not include the trait of Honesty-Humility—a trait that has been implicated in online behavior. For example, Honesty-Humility has been found to predict a person’s tendency and willingness to behave in a careless manner in the information environment as indicated by its strong association with the frequency of risky online behaviors, and feelings of disinhibition when operating online (D’Agata and Kwantes, 2020 ). Although there is a dearth of research studying Honesty-Humility and fake news belief, the related construct of Intellectual Humility (the tendency to be humble about, and acknowledge the limitations of, one’s own knowledge and understanding; Krumei-Mancuso and Rouse, 2016 ) provides theoretical support for the role of Honesty-Humility. Intellectual Humility is associated with less susceptibility to fake news and conspiratorial beliefs (Bowes and Tasimi, 2022 ) and more fact-checking behavior when encountering misinformation (Koetke et al., 2022 ; Koetke et al., 2023 ). In sum, Honesty-Humility seems to represent a highly predictive personality trait of the extent to which a person is susceptible to being influenced in the information environment. The first goal of this article, therefore, is to augment the contribution provided by Calvillo et al. ( 2021 ) that measured personality using the traditional five-factor model by including an examination of how Honesty-Humility contributes to the relationship using the HEXACO personality inventory (Ashton et al., 2014 ; Ashton and Lee, 2007 ).

An understanding of how personality traits influence susceptibility to online misinformation would be enhanced by an exploration of how the socially aversive dark triad traits of personality might also be related. Hodson et al. ( 2018 ) conducted a meta-analysis from which they concluded that the dark triad traits, which consist of psychopathy (i.e., impulsivity, lack of empathy), narcissism (i.e., a grandiose sense of self), and Machiavellianism (i.e., manipulative, amoral, and cunning) are not distinct from Honesty-Humility, but rather correspond to tendencies at the low end of the Honesty-Humility spectrum. Irrespective of whether high scores on the dark traits correspond to low Honesty-Humility, past research has identified an association between conspiratorial beliefs and the dark personality traits, however the pattern of results are inconsistent. For example, in a set of three studies, Cichocka et al. ( 2016 ) found that narcissism was related to conspiracy theory belief. Similarly, Lantian et al. ( 2017 ) found that a greater need for uniqueness, which is a feature of narcissism (Emmons, 1984 ), leads to greater belief in conspiracy theories. By contrast, March and Springer ( 2019 ) found that Machiavellianism and psychopathy, and not narcissism, predict conspiratorial beliefs. Relatedly, willingness to conspire has been reported to mediate the relationship between Machiavellianism and conspiratorial belief, such that that individuals who conspire against others tend to believe that they are likely to be conspired against (Douglas and Sutton, 2011 ). In more recent work, still others have found that all three dark triad traits were related to COVID-19 specific conspiracy theory belief (Giancola et al., 2023 ; Hughes and Machan, 2021 ). The differences across studies may be partially explained by the different scales used to measure the dark triad traits among studies. Overall, the dark triad traits may lead to conspiratorial belief due to one’s need to feel special and know things others do not (an element of narcissism), a high level of mistrust in others (present in psychopathy), or the high willingness to conspire (exhibited in high Machiavellianism).

What is less clear from our examination of the literature is the role that the dark personality traits play in the detection of misinformation in the information environment. Recent research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic found that, similar to individuals who believed misinformation about COVID-19, individuals higher in the dark triad traits were less likely to partake in health promoting behaviors (Ścigała et al., 2021 ; Zajenkowski et al., 2020 ), like handwashing (Nowak et al., 2020 ; Triberti et al., 2021 ), mask-wearing (Chávez-Ventura et al., 2022 ), and willingness to get vaccinated (Howard, 2022 ) than people lower on these traits. However, this pattern may not necessarily be due to misinformation belief, it could indicate a general tendency for people high on the dark traits to behave in a selfish, self-centered, self-important manner. The most convincing study to suggest that the dark triad traits could be associated with misinformation detection was by Triberti et al. ( 2021 ) who reported that individuals higher on all three dark triad traits endorsed spreading alarming news before verifying it was true. However, it is unclear whether the pattern exhibited by Triberti et al.’s participants indicated an inability to discern misinformation, or the lack of motivation to do so. To better understand the role that personality plays in one’s identification of misinformation, we have included a measure of the Dark Triad traits alongside the HEXACO traits to determine how the collection of personality traits predicts one’s discernment of true from fake news headlines. Based on the results reported by Triberti et al., and the evidence suggesting that the dark triad traits represent component features associated with low Honesty-Humility (Hodson et al., 2018 ), we predict that greater narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism should be associated with a decreased ability to discern real from fake news stories.

Careless online behavior

Besides personality, the current study examines how one’s propensity to engage in unsafe or risky online behaviors and interactions might make them less sensitive to misinformation propagated within the information environment. Individuals who feel increased disinhibition online show an increased willingness to participate in risky online behaviors, such as disclosing personal information to others, and a higher frequency of falling victim to social engineering attacks (D’Agata and Kwantes, 2020 ). In addition, individuals who report a willingness to form relationships online have an increased tendency to disclose personal information, leaving them vulnerable to deception, whereas people who are more suspicious of others’ intentions online tend to be more conscientious, and thus may be better protected against deception from others online (D’Agata et al., 2021 ).

The way in which users interact with information and others online seems therefore to be shaped by the level of trust (or level of suspicion) they feel in exploring or consuming information from unknown sources and forming relationships with individuals who have only ever presented themselves online. It has been established that personality factors are associated with one’s tendency and willingness to engage in risky online behaviors (D’Agata and Kwantes, 2020 ) and one’s willingness to form relationships with others completely online (D’Agata et al., 2021 ). Common to both studies are the idea that some people have a high tolerance for risk when operating online—a risk that seems to have its basis in a tendency to trust the information presented to them. We postulate therefore, that the factors that put people at risk for social engineering and romance scams might also be at play in one’s tendency to believe unverified content presented in the information environment. Hence, in the current study, we tested the hypothesis that people who have a willingness, tendency, or history of reckless online behavior will exhibit a diminished ability to discern real from fake news headlines.

Demographic characteristics

In the misinformation and fake news literature, the effects of a variety of demographic variables have been studied, including gender, religiosity, and age. In the following section, we outline the current evidence for demographic differences in susceptibility to misinformation and fake news.

The effect of gender on belief in misinformation is inconsistent in the literature. Some studies have found that women had a higher prevalence of sharing misinformation on social media than men (e.g., Chen et al., 2015 ), while others have found no significant gender differences in detecting or sharing misinformation (Almenar et al., 2021 ; Mansoori et al., 2023 ). These differences are likely due in part to the heterogeneity between studies, particularly in the types of misinformation used and cultural differences in the sample. For example, Mansoori et al. ( 2023 ) noted that despite finding no gender effects, they had predicted an impact of gender because the sample used men and women from the United Arab Emirates, a traditionally patriarchal culture where genders differ in access to news and technology. Most of the research on gender differences in conspiracy theories have also found null results (e.g., Farhart et al., 2020 ; Miller et al., 2016 ), though some research using COVID-19 conspiracy theories specifically found women reported less belief than men (Cassese et al., 2020 ; Kim and Kim, 2021 ). It is likely the case that gender does not have a consistent effect on all fake news and misinformation belief and may play a more significant role when certain types of misinformation are used, such as when gendered narratives are leveraged to influence conspiracy theory belief (Bracewell, 2021 ). A discussion of gendered narratives is beyond the scope of this article, but a review of the literature makes clear that gender is an important demographic variable to measure and test in the current study.

Religious beliefs

Religiosity has also been implicated as a correlate to misinformation belief. Greater religious beliefs have been associated with belief in fake news (Bronstein et al., 2019 ), and political and medical conspiracy theories (Galliford and Furnham, 2017 ). This susceptibility to misinformation may be due to differences in thinking styles. Religious skeptics showed more use of an analytical thinking style (Pennycook et al., 2012 ; Pennycook et al., 2014 ; Shenhav et al., 2012 ), less errors on logical reasoning problems (Pennycook et al., 2013 ), and better performance on tests of critical thinking skills (Pennycook et al., 2016 ). Based on these associations in the literature, we expect to find that participants who self-report as high on a scale of religiosity will be less skilled at discerning fake from real news than those who report low religiosity.

Age is a point of focus in the misinformation literature; Many media literacy campaigns target young people (e.g., Schulten, 2022 ) and there is evidence that exposure to fake news and misinformation can have deleterious effects on youth (Dhiman, 2023 ). This specific focus on youth could be due to the significant amount of time younger generations spend on the internet and social media (Pérez-Escoda et al., 2021 )—a place where fake news and misinformation proliferate. Compounding this exposure risk is that younger people may not have developed the critical thinking skills (Kuhn, 1999 ) required to combat misinformation. Indeed, there is evidence that younger people tend to believe general conspiracy theories (Galliford and Furnham, 2017 ) and fake news (Halpern et al., 2019 ), more than older people. We expect to replicate the reported patterns in the current study.

The current research

In this study, we sought to examine the role that personality, the propensity for careless or risky online behavior, gender, religiosity, and age play in predicting one’s accuracy in discerning real from fake content presented in the online information environment. It is our view that with a better understanding of the antecedents of misinformation belief, educational materials to enhance media literacy can be enhanced to reduce the public’s susceptibility to it. However, with respect to personality, we acknowledge that traits are considered relatively fixed and resistant to change. Accordingly, our goals for the work presented here exclude any suggestion that resilience to misinformation requires adjustments to one’s personality. Instead, we hope that training materials for media literacy can incorporate our findings about personality to include components that explain how personality relates to susceptibility to misinformation belief, and perhaps even include personality measures to promote self-awareness about how one’s own traits could put them at risk online.

The literature suggests that personality influences one’s susceptibility to misinformation (e.g., Calvillo et al., 2021 )—a finding we predict will be replicated in the current study. The current research augments the work testing the relationships to the Big Five personality traits by Calvillo et al. ( 2021 ) to include a consideration of how Honesty-Humility (and the three dark triad personality traits that may be associated with those low on the Honesty-Humility dimension) relates to a person’s accuracy in discerning real from fake information. Based on work demonstrating a relationship between intellectual humility and belief in fake news and conspiracy theories (Bowes and Tasimi, 2022 ), an association between low Honesty-Humility and a heightened tendency to make oneself vulnerable while operating online (e.g., (D’Agata and Kwantes, 2020 ), and the evidence suggesting that the dark triad traits represent component features associated with low Honesty-Humility (Hodson et al., 2018 ), we predicted that ( H1 ) lower Honesty-Humility and ( H2 ) higher scores on the dark triad traits of narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism would be associated with decreased accuracy in discerning real from fake information.

We also predicted that those who show a willingness and tendency to interact with information and strangers online in manners that put them at risk for falling victim to scams or other online criminal acts (e.g., D’Agata et al., 2021 ) will also demonstrate a lack judgment when faced with new information of ambiguous veracity. Hence, we hypothesized that individuals who tend to be ( H3 ) disinhibited and reckless online (i.e., higher scores on the careless online behavior measures) will perform more poorly in a task that asks them to discern real from fake information than those who show good judgement online.

Finally, we collected demographic data to identify factors that relate to discernment of truthful from false information. We expected to demonstrate the same patterns with respect to age and religion already documented in the literature, such that ( H4 ) lower age and ( H5 ) less religiosity will be related to better accuracy in distinguishing between real and fake news. In terms of gender, the results in the literature are inconsistent, likely due in part to the heterogeneity of study methods, especially the types of misinformation used across studies. Since we do not employ specific gendered narratives and use a wide range of misinformation in our fake news content, ( H6 ) we did not expect to find gender differences in accuracy in distinguishing between real and fake news.

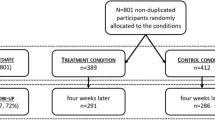

Participants

This research was granted approval by our organization’s Human Research Ethics Committee. We conducted an a priori power analysis based on a small effect size and determined a goal sample size of 500 participants. We used Qualtrics Panels to recruit participants, which is a web-based survey platform that allows researchers to build and monitor surveys, while Qualtrics Panels distributes the survey links and collects data on the researchers’ behalf. Footnote 2 To be eligible for the study, participants had to be between the ages of 18 and 80, live in the US or Canada, and be fluent in English. In addition, partial responses were not recorded, and those who failed any of the validity checks for random responses were removed from the sample. Further, respondents with completion times that were extreme outliers or those who took 50% less than the median time to complete the survey were removed.

The sample ( N = 510) comprised of Canadian and American adults (see Table 1 ). The sample included 315 females and 188 males (four participants identified outside of the gender binary), ranging in age from 18–80 ( M = 39.8, SD = 15.8). In our sample, 83.3% had some post-secondary education, and 60.6% of the sample was currently employed.

Demographic questionnaire

Participants completed questions on demographic characteristics, including gender, age, highest level of education, and current employment status. In addition, they completed a religious belief scale to assess religiosity and spirituality (Pennycook et al., 2016 ). The questionnaire contains items such as, “I believe in heaven” and “I believe in demons,” and uses a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) .

Online behavior measures

Risky online behaviors.

We used the Risky Online Behaviors scale (ROB; D’Agata and Kwantes, 2020 ) which includes a range of online behaviors for which participants are asked to indicate how often they have engaged in each. Items were rated using a 5-point frequency scale: 0 (never) , 1 (1 time) , 2 (2 times) , 3 (3–5 times) and 4 (more than 5 times) . The measure is not a psychometric tool but rather a count of the frequency with which a person has engaged in risky online behaviors. Behaviors range from the relatively benign (“ I’ve posted personal information in comments on social media that were public” ) to ones that make the participant vulnerable (e.g., “ I’ve disclosed a password to one of my own accounts via email” ). The measure indicated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.94).

Online Disinhibition

We used the Online Disinhibition scale (OD; D’Agata and Kwantes, 2020 ) to assess the extent to which individuals feel disinhibited online in the manner described by Suler ( 2004 ). The measure includes 20 items designed to measure comfort and feelings of anonymity while operating online. Example items include, “ I don’t need to monitor my behavior online as much as I do offline” and “ I have a different personality online than I do in the real world” . Items are rated using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) . The measure indicated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.90).

Openness to Form Online Relationships

We used the Openness to Form Online Relationships scale (OFOR; D’Agata et al., 2021 ) to assess one’s willingness to develop friendships and romantic relationships with strangers online. The 6-items are rated on a 5-point rating scale, ranging from 1 ( strongly disagree ) to 5 ( strongly agree ) and consists of two subscales: Engagement, a measure of a person’s level of comfort in engaging with strangers online (good internal consistency, Cronbach’s α = 0.84) and Suspicion, a measure of a person’s level of mistrust of others while operating online (acceptable internal consistency, Cronbach’s α = 0.63).

Personality measures

Hexaco personality inventory.

We used the 100-item HEXACO Personality Inventory —Revised (HEXACO–PI–R; Lee and Ashton, 2018 ), to assess the six-factor model of personality (Honesty-Humility, Emotionality, eXtraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Openness). Participants rated the items (e.g., “people sometimes tell me that I am too critical of others” and “I avoid making ‘small talk’ with people” using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) . The subscales indicated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α ’s = 0.74–0.85).

The Short Dark Triad

We used the 27-Item Short Dark Triad (SD3; Jones and Paulhus, 2014 ) to measure the three socially aversive dark triad personality traits (narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy). Participants were asked to rate the items (e.g., “ It’s not wise to tell your secrets” , and “I like to get acquainted with important people” ) using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) . The subscales indicated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α ’s = 0.75–0.83).

Discerning real from fake information: The Headline Task

Twelve real and twelve fake headlines were selected from Peter et al.’s ( 2021 ) headline task which used real news and fake news headlines published on the internet and was adapted from Pennycook and Rand ( 2019 ). Mainstream news sources, such as CBC News and The New York Times were used to select real news headlines. These sources fell anywhere from far-left to far-right on the political spectrum. The real news headlines included topics such as climate change, government spending, and teen drug use. Headlines categorized as fake were selected from articles labeled as ‘false’ by Snopes.com, a fact-checking resource that directly evaluates information in the news. Examples of news stories featured in the fake news headlines include inmates outliving life sentences, micro-chipping campaigns, and animal limit laws. The headlines were categorized into three bins based on data from Peter et al. ( 2021 ) where headlines were classified as high accuracy (i.e., most of their participants accurately identified that the headline was either real or fake), 50–50 accuracy (i.e., ~50% of their participants were accurate), and low accuracy (i.e., most of their participants did not accurately identify that the headline was either real or fake). We selected eight headlines from each bin (four real and four fake) to use in the current study.

Participants were shown each headline separately and were told that while some may be real or accurate, others may not be. For each headline, participants were asked to rate whether they think the headline is from a real or fake news story. Task performance was assessed using measures borrowed from signal detection theory (Stanislaw and Todorov, 1999 ). Specifically, sensitivity, or accuracy in distinguishing between real and fake headlines was assessed by calculating the statistic d’ . Response bias (i.e., a tendency for one response to be favored over the other regardless of veracity) was assessed by calculating the statistic c . Footnote 3

Following the completion of the demographic questionnaire, participants completed the Headline Task where real and fake headlines were presented in randomized order. Next, they completed the Online Disinhibition Scale, Risky Online Behavior Scale, Openness to Form Online Relationships Scale, The HEXACO-PI-R, and the SD3 in a randomized order.

Descriptive statistics for all measures are reported in Table 2 and correlations among all measures are reported in Table 3 .

Headline task accuracy

First, we examined the associations between performance on the Headline Task and the demographic variables, using two-tailed Pearson’s correlation tests with an alpha level of 0.05. Age was not significantly correlated with headline task accuracy ( r = 0.03, p = 0.49). Religiosity was negatively correlated with headline task accuracy, such that people who were lower on religiosity were better at distinguishing between real and fake news headlines ( r = −0.24, p < 0.001). A two-tailed paired samples t -test with an alpha level of 0.05 indicated no significant difference in headline task performance between men and women ( t (501) = −0.77, p = 0.44).

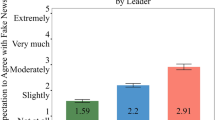

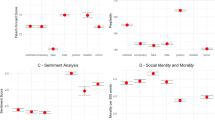

As expected, the different personality and online behavior variables were associated with one’s discernment of real from fake news. We conducted two-tailed Pearson’s correlation tests with a Bonferroni corrected alpha level of 0.004 to control for the Type I error rate due to multiple comparisons (see Table 3 for correlations among all measures). The correlational analysis provided support for our a priori predictions that poorer performance on the Headline Task would be associated with lower feelings of suspicion towards others’ intentions online ( r = 0.16), greater willingness to engage in relationships with strangers online ( r = −0.19), and greater online disinhibition ( r = −0.23), and greater risky online behaviors ( r = −0.18; all p ’s < 0.001). With respect to the personality measures, lower Honesty-Humility ( r = 0.22), lower Openness ( r = 0.16), and lower Conscientiousness ( r = 0.20) were associated with poorer performance on the Headline task, as were greater Machiavellianism ( r = −0.19), greater narcissism ( r = −0.22), and greater psychopathy ( r = −0.25; all p ’s < 0.001).

Headline task response bias

To test whether personality and individual differences were associated with a particular response pattern, we correlated response bias (i.e., c ) with the personality and online behavior measures (see Table 3 ). A positive c statistic indicated a tendency toward responding “true” to a headline regardless of its veracity, and a negative c statistic indicated a tendency toward responding ‘false’. The two-tailed Pearson’s correlation tests with a Bonferroni corrected alpha level of 0.004 indicated a significant bias toward rating the headlines as true among those who reported greater online disinhibition ( r = 0.23), greater risky online behaviors ( r = 0.28), and greater willingness to engage with strangers online ( r = 0.19; all p ’s < 0.001). The same bias was found among those reporting higher levels of Machiavellianism ( r = 0.22), narcissism ( r = 0.21), and psychopathy ( r = 0.26; all p’ s < 0.001). Finally, lower Honesty-Humility ( r = −0.21, p < 0.001) was associated with a bias toward indicating a headline is true. We did not find that suspicion of others’ intentions online, and the remaining personality traits, were significantly correlated with response bias.

Overall, our findings suggest that there are psychological and personality factors that affect the accurate assessment of the veracity of information encountered online. Individuals who self-reported as less diligent and organized (lower Conscientiousness), less curious and imaginative (lower Openness), and less sincere and honest (lower Honesty-Humility) demonstrated a diminished discernment between fake from real headlines. Consistent with the features of those who score low on Honesty-Humility, those high on the dark triad traits, and therefore those who self-report as more manipulative and cunning (higher Machiavellianism), more selfish and paranoid (higher Narcissism), and more impulsive and callous (higher Psychopathy) exhibited the same reduced accuracy, and a bias toward considering headlines as being ‘true’. Finally, those who were careless online (i.e., feeling more disinhibited online, more willing to engage with and share personal information with strangers online, or being less suspicious of strangers’ intentions online) were less accurate in discerning between fake and real news headlines, and similarly exhibited a bias towards considering the headlines to be true.

Our results confirm previously reported associations between personality and susceptibility to misinformation and provide some novel contributions. Although our personality results partially replicated Calvillo et al. ( 2021 ) with greater fake news detection accuracy being associated with higher Openness and Conscientiousness, unlike Calvillo et al., correlations for the role of Extraversion and Agreeableness did not reach significance; however, this could have resulted from the use of a different personality assessment tool or any differences between our task and theirs.

The novel contribution to the body of work is our finding that low levels of Honesty-Humility, and its associated high scores on dark triad traits, are related to a reduced accuracy in distinguishing real from false information, and an apparent bias toward interpreting information they encounter as true—a pattern suggesting that the lack of accuracy in identifying fake news from real news could be due to the tendency to consider all information as truthful. While results in the literature are mixed on the relationship between the dark triad traits and conspiratorial belief, with some studies finding only some of the triad traits having significant associations (e.g., Cichocka et al., 2016 ; March and Springer, 2019 ), our results align most closely with Hughes and Machan ( 2021 ) and Giancola et al. ( 2023 ) who found that greater levels of all three dark triad traits were associated with greater endorsement of conspiracy theories. Our results complement and build upon their findings by raising the possibility that the lower accuracy in distinguishing real from fake news headlines among those who score low on Honesty-Humility may be because the dark triad traits represent Honesty-Humility’s key features (n.b. Hodson et al., 2018 ). Based on our analysis of response bias, we propose further that individuals with greater dark triad traits could be especially susceptible to accepting conspiracy theories (Cichocka et al., 2016 ; Douglas and Sutton, 2011 ; Giancola et al., 2023 ; Hughes and Machan, 2021 ; Lantian et al., 2017 ; March and Springer, 2019 ) because of a general tendency or bias to believe information, thus making them more apt to consider far-fetched claims about government conspiracies to be believable or probable.