Peer Recognized

Make a name in academia

How to Write a Research Paper: the LEAP approach (+cheat sheet)

In this article I will show you how to write a research paper using the four LEAP writing steps. The LEAP academic writing approach is a step-by-step method for turning research results into a published paper .

The LEAP writing approach has been the cornerstone of the 70 + research papers that I have authored and the 3700+ citations these paper have accumulated within 9 years since the completion of my PhD. I hope the LEAP approach will help you just as much as it has helped me to make an real, tangible impact with my research.

What is the LEAP research paper writing approach?

I designed the LEAP writing approach not only for merely writing the papers. My goal with the writing system was to show young scientists how to first think about research results and then how to efficiently write each section of the research paper.

In other words, you will see how to write a research paper by first analyzing the results and then building a logical, persuasive arguments. In this way, instead of being afraid of writing research paper, you will be able to rely on the paper writing process to help you with what is the most demanding task in getting published – thinking.

The four research paper writing steps according to the LEAP approach:

I will show each of these steps in detail. And you will be able to download the LEAP cheat sheet for using with every paper you write.

But before I tell you how to efficiently write a research paper, I want to show you what is the problem with the way scientists typically write a research paper and why the LEAP approach is more efficient.

How scientists typically write a research paper (and why it isn’t efficient)

Writing a research paper can be tough, especially for a young scientist. Your reasoning needs to be persuasive and thorough enough to convince readers of your arguments. The description has to be derived from research evidence, from prior art, and from your own judgment. This is a tough feat to accomplish.

The figure below shows the sequence of the different parts of a typical research paper. Depending on the scientific journal, some sections might be merged or nonexistent, but the general outline of a research paper will remain very similar.

Here is the problem: Most people make the mistake of writing in this same sequence.

While the structure of scientific articles is designed to help the reader follow the research, it does little to help the scientist write the paper. This is because the layout of research articles starts with the broad (introduction) and narrows down to the specifics (results). See in the figure below how the research paper is structured in terms of the breath of information that each section entails.

How to write a research paper according to the LEAP approach

For a scientist, it is much easier to start writing a research paper with laying out the facts in the narrow sections (i.e. results), step back to describe them (i.e. write the discussion), and step back again to explain the broader picture in the introduction.

For example, it might feel intimidating to start writing a research paper by explaining your research’s global significance in the introduction, while it is easy to plot the figures in the results. When plotting the results, there is not much room for wiggle: the results are what they are.

Starting to write a research papers from the results is also more fun because you finally get to see and understand the complete picture of the research that you have worked on.

Most importantly, following the LEAP approach will help you first make sense of the results yourself and then clearly communicate them to the readers. That is because the sequence of writing allows you to slowly understand the meaning of the results and then develop arguments for presenting to your readers.

I have personally been able to write and submit a research article in three short days using this method.

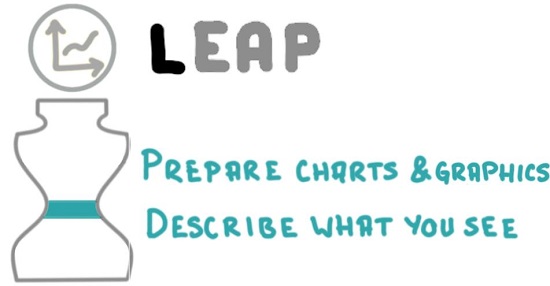

Step 1: Lay Out the Facts

You have worked long hours on a research project that has produced results and are no doubt curious to determine what they exactly mean. There is no better way to do this than by preparing figures, graphics and tables. This is what the first LEAP step is focused on – diving into the results.

How to p repare charts and tables for a research paper

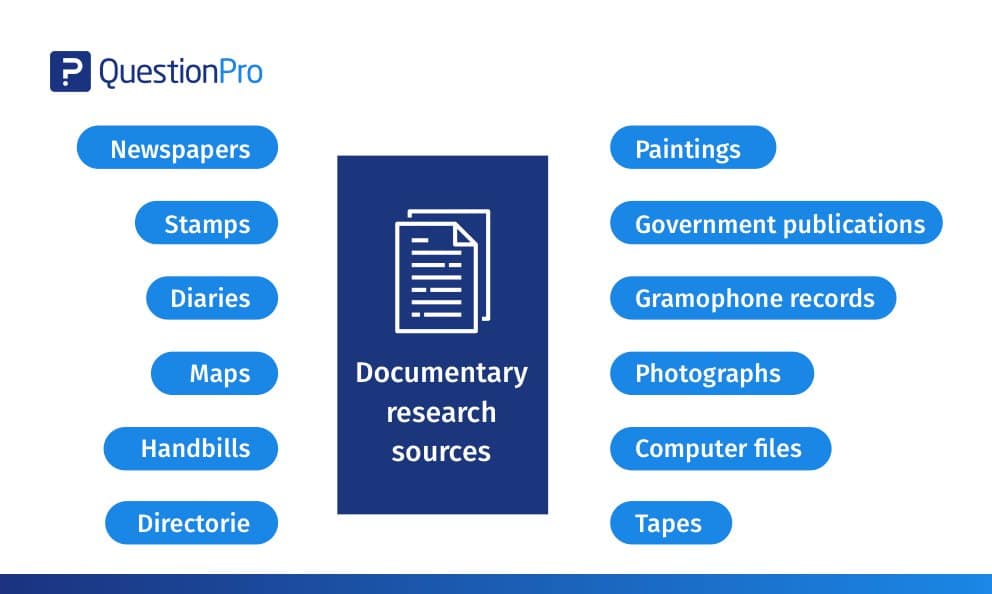

Your first task is to try out different ways of visually demonstrating the research results. In many fields, the central items of a journal paper will be charts that are based on the data generated during research. In other fields, these might be conceptual diagrams, microscopy images, schematics and a number of other types of scientific graphics which should visually communicate the research study and its results to the readers. If you have reasonably small number of data points, data tables might be useful as well.

Tips for preparing charts and tables

- Try multiple chart types but in the finished paper only use the one that best conveys the message you want to present to the readers

- Follow the eight chart design progressions for selecting and refining a data chart for your paper: https://peerrecognized.com/chart-progressions

- Prepare scientific graphics and visualizations for your paper using the scientific graphic design cheat sheet: https://peerrecognized.com/tools-for-creating-scientific-illustrations/

How to describe the results of your research

Now that you have your data charts, graphics and tables laid out in front of you – describe what you see in them. Seek to answer the question: What have I found? Your statements should progress in a logical sequence and be backed by the visual information. Since, at this point, you are simply explaining what everyone should be able to see for themselves, you can use a declarative tone: The figure X demonstrates that…

Tips for describing the research results :

- Answer the question: “ What have I found? “

- Use declarative tone since you are simply describing observations

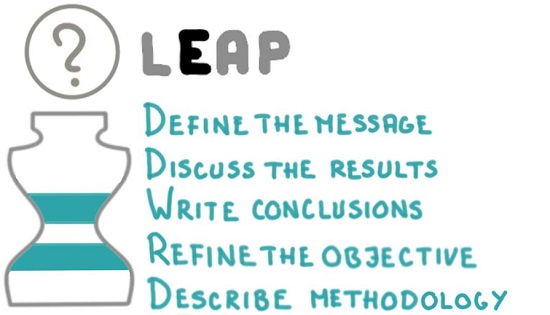

Step 2: Explain the results

The core aspect of your research paper is not actually the results; it is the explanation of their meaning. In the second LEAP step, you will do some heavy lifting by guiding the readers through the results using logic backed by previous scientific research.

How to define the Message of a research paper

To define the central message of your research paper, imagine how you would explain your research to a colleague in 20 seconds . If you succeed in effectively communicating your paper’s message, a reader should be able to recount your findings in a similarly concise way even a year after reading it. This clarity will increase the chances that someone uses the knowledge you generated, which in turn raises the likelihood of citations to your research paper.

Tips for defining the paper’s central message :

- Write the paper’s core message in a single sentence or two bullet points

- Write the core message in the header of the research paper manuscript

How to write the Discussion section of a research paper

In the discussion section you have to demonstrate why your research paper is worthy of publishing. In other words, you must now answer the all-important So what? question . How well you do so will ultimately define the success of your research paper.

Here are three steps to get started with writing the discussion section:

- Write bullet points of the things that convey the central message of the research article (these may evolve into subheadings later on).

- Make a list with the arguments or observations that support each idea.

- Finally, expand on each point to make full sentences and paragraphs.

Tips for writing the discussion section:

- What is the meaning of the results?

- Was the hypothesis confirmed?

- Write bullet points that support the core message

- List logical arguments for each bullet point, group them into sections

- Instead of repeating research timeline, use a presentation sequence that best supports your logic

- Convert arguments to full paragraphs; be confident but do not overhype

- Refer to both supportive and contradicting research papers for maximum credibility

How to write the Conclusions of a research paper

Since some readers might just skim through your research paper and turn directly to the conclusions, it is a good idea to make conclusion a standalone piece. In the first few sentences of the conclusions, briefly summarize the methodology and try to avoid using abbreviations (if you do, explain what they mean).

After this introduction, summarize the findings from the discussion section. Either paragraph style or bullet-point style conclusions can be used. I prefer the bullet-point style because it clearly separates the different conclusions and provides an easy-to-digest overview for the casual browser. It also forces me to be more succinct.

Tips for writing the conclusion section :

- Summarize the key findings, starting with the most important one

- Make conclusions standalone (short summary, avoid abbreviations)

- Add an optional take-home message and suggest future research in the last paragraph

How to refine the Objective of a research paper

The objective is a short, clear statement defining the paper’s research goals. It can be included either in the final paragraph of the introduction, or as a separate subsection after the introduction. Avoid writing long paragraphs with in-depth reasoning, references, and explanation of methodology since these belong in other sections. The paper’s objective can often be written in a single crisp sentence.

Tips for writing the objective section :

- The objective should ask the question that is answered by the central message of the research paper

- The research objective should be clear long before writing a paper. At this point, you are simply refining it to make sure it is addressed in the body of the paper.

How to write the Methodology section of your research paper

When writing the methodology section, aim for a depth of explanation that will allow readers to reproduce the study . This means that if you are using a novel method, you will have to describe it thoroughly. If, on the other hand, you applied a standardized method, or used an approach from another paper, it will be enough to briefly describe it with reference to the detailed original source.

Remember to also detail the research population, mention how you ensured representative sampling, and elaborate on what statistical methods you used to analyze the results.

Tips for writing the methodology section :

- Include enough detail to allow reproducing the research

- Provide references if the methods are known

- Create a methodology flow chart to add clarity

- Describe the research population, sampling methodology, statistical methods for result analysis

- Describe what methodology, test methods, materials, and sample groups were used in the research.

Step 3: Advertize the research

Step 3 of the LEAP writing approach is designed to entice the casual browser into reading your research paper. This advertising can be done with an informative title, an intriguing abstract, as well as a thorough explanation of the underlying need for doing the research within the introduction.

How to write the Introduction of a research paper

The introduction section should leave no doubt in the mind of the reader that what you are doing is important and that this work could push scientific knowledge forward. To do this convincingly, you will need to have a good knowledge of what is state-of-the-art in your field. You also need be able to see the bigger picture in order to demonstrate the potential impacts of your research work.

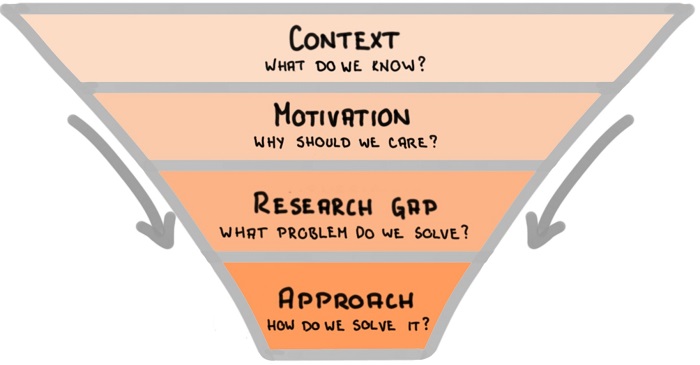

Think of the introduction as a funnel, going from wide to narrow, as shown in the figure below:

- Start with a brief context to explain what do we already know,

- Follow with the motivation for the research study and explain why should we care about it,

- Explain the research gap you are going to bridge within this research paper,

- Describe the approach you will take to solve the problem.

Tips for writing the introduction section :

- Follow the Context – Motivation – Research gap – Approach funnel for writing the introduction

- Explain how others tried and how you plan to solve the research problem

- Do a thorough literature review before writing the introduction

- Start writing the introduction by using your own words, then add references from the literature

How to prepare the Abstract of a research paper

The abstract acts as your paper’s elevator pitch and is therefore best written only after the main text is finished. In this one short paragraph you must convince someone to take on the time-consuming task of reading your whole research article. So, make the paper easy to read, intriguing, and self-explanatory; avoid jargon and abbreviations.

How to structure the abstract of a research paper:

- The abstract is a single paragraph that follows this structure:

- Problem: why did we research this

- Methodology: typically starts with the words “Here we…” that signal the start of own contribution.

- Results: what we found from the research.

- Conclusions: show why are the findings important

How to compose a research paper Title

The title is the ultimate summary of a research paper. It must therefore entice someone looking for information to click on a link to it and continue reading the article. A title is also used for indexing purposes in scientific databases, so a representative and optimized title will play large role in determining if your research paper appears in search results at all.

Tips for coming up with a research paper title:

- Capture curiosity of potential readers using a clear and descriptive title

- Include broad terms that are often searched

- Add details that uniquely identify the researched subject of your research paper

- Avoid jargon and abbreviations

- Use keywords as title extension (instead of duplicating the words) to increase the chance of appearing in search results

How to prepare Highlights and Graphical Abstract

Highlights are three to five short bullet-point style statements that convey the core findings of the research paper. Notice that the focus is on the findings, not on the process of getting there.

A graphical abstract placed next to the textual abstract visually summarizes the entire research paper in a single, easy-to-follow figure. I show how to create a graphical abstract in my book Research Data Visualization and Scientific Graphics.

Tips for preparing highlights and graphical abstract:

- In highlights show core findings of the research paper (instead of what you did in the study).

- In graphical abstract show take-home message or methodology of the research paper. Learn more about creating a graphical abstract in this article.

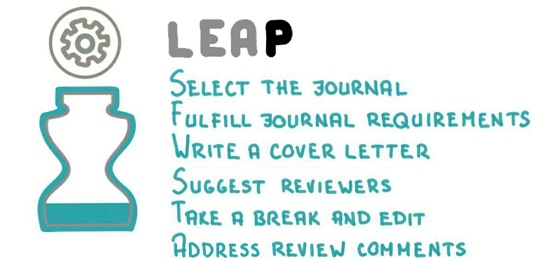

Step 4: Prepare for submission

Sometimes it seems that nuclear fusion will stop on the star closest to us (read: the sun will stop to shine) before a submitted manuscript is published in a scientific journal. The publication process routinely takes a long time, and after submitting the manuscript you have very little control over what happens. To increase the chances of a quick publication, you must do your homework before submitting the manuscript. In the fourth LEAP step, you make sure that your research paper is published in the most appropriate journal as quickly and painlessly as possible.

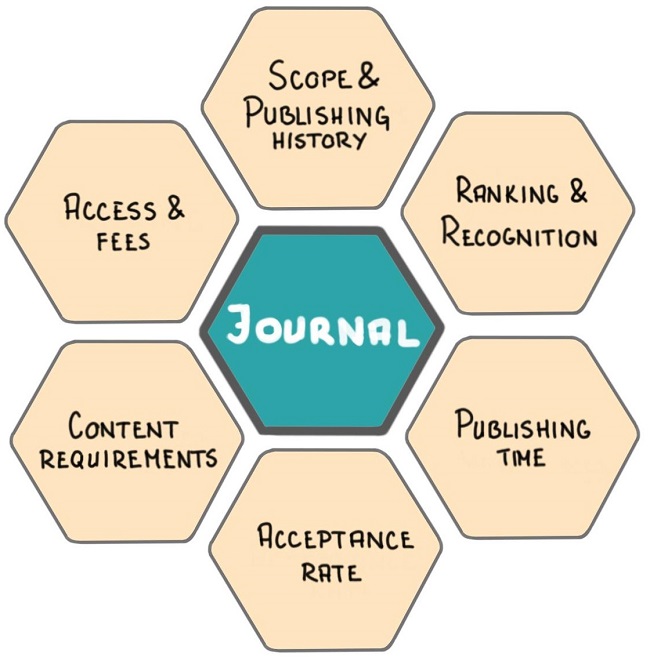

How to select a scientific Journal for your research paper

The best way to find a journal for your research paper is it to review which journals you used while preparing your manuscript. This source listing should provide some assurance that your own research paper, once published, will be among similar articles and, thus, among your field’s trusted sources.

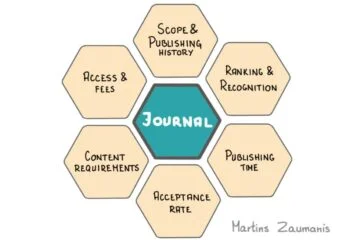

After this initial selection of hand-full of scientific journals, consider the following six parameters for selecting the most appropriate journal for your research paper (read this article to review each step in detail):

- Scope and publishing history

- Ranking and Recognition

- Publishing time

- Acceptance rate

- Content requirements

- Access and Fees

How to select a journal for your research paper:

- Use the six parameters to select the most appropriate scientific journal for your research paper

- Use the following tools for journal selection: https://peerrecognized.com/journals

- Follow the journal’s “Authors guide” formatting requirements

How to Edit you manuscript

No one can write a finished research paper on their first attempt. Before submitting, make sure to take a break from your work for a couple of days, or even weeks. Try not to think about the manuscript during this time. Once it has faded from your memory, it is time to return and edit. The pause will allow you to read the manuscript from a fresh perspective and make edits as necessary.

I have summarized the most useful research paper editing tools in this article.

Tips for editing a research paper:

- Take time away from the research paper to forget about it; then returning to edit,

- Start by editing the content: structure, headings, paragraphs, logic, figures

- Continue by editing the grammar and language; perform a thorough language check using academic writing tools

- Read the entire paper out loud and correct what sounds weird

How to write a compelling Cover Letter for your paper

Begin the cover letter by stating the paper’s title and the type of paper you are submitting (review paper, research paper, short communication). Next, concisely explain why your study was performed, what was done, and what the key findings are. State why the results are important and what impact they might have in the field. Make sure you mention how your approach and findings relate to the scope of the journal in order to show why the article would be of interest to the journal’s readers.

I wrote a separate article that explains what to include in a cover letter here. You can also download a cover letter template from the article.

Tips for writing a cover letter:

- Explain how the findings of your research relate to journal’s scope

- Tell what impact the research results will have

- Show why the research paper will interest the journal’s audience

- Add any legal statements as required in journal’s guide for authors

How to Answer the Reviewers

Reviewers will often ask for new experiments, extended discussion, additional details on the experimental setup, and so forth. In principle, your primary winning tactic will be to agree with the reviewers and follow their suggestions whenever possible. After all, you must earn their blessing in order to get your paper published.

Be sure to answer each review query and stick to the point. In the response to the reviewers document write exactly where in the paper you have made any changes. In the paper itself, highlight the changes using a different color. This way the reviewers are less likely to re-read the entire article and suggest new edits.

In cases when you don’t agree with the reviewers, it makes sense to answer more thoroughly. Reviewers are scientifically minded people and so, with enough logical and supported argument, they will eventually be willing to see things your way.

Tips for answering the reviewers:

- Agree with most review comments, but if you don’t, thoroughly explain why

- Highlight changes in the manuscript

- Do not take the comments personally and cool down before answering

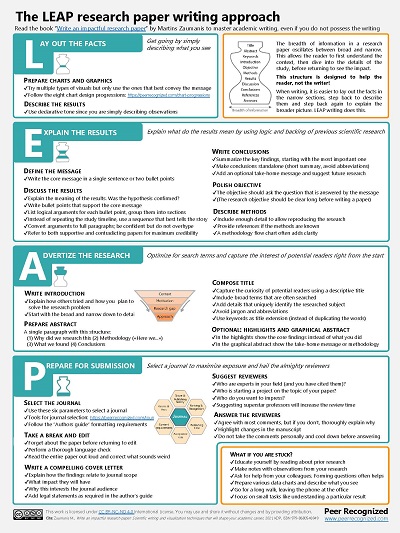

The LEAP research paper writing cheat sheet

Imagine that you are back in grad school and preparing to take an exam on the topic: “How to write a research paper”. As an exemplary student, you would, most naturally, create a cheat sheet summarizing the subject… Well, I did it for you.

This one-page summary of the LEAP research paper writing technique will remind you of the key research paper writing steps. Print it out and stick it to a wall in your office so that you can review it whenever you are writing a new research paper.

Now that we have gone through the four LEAP research paper writing steps, I hope you have a good idea of how to write a research paper. It can be an enjoyable process and once you get the hang of it, the four LEAP writing steps should even help you think about and interpret the research results. This process should enable you to write a well-structured, concise, and compelling research paper.

Have fund with writing your next research paper. I hope it will turn out great!

Learn writing papers that get cited

The LEAP writing approach is a blueprint for writing research papers. But to be efficient and write papers that get cited, you need more than that.

My name is Martins Zaumanis and in my interactive course Research Paper Writing Masterclass I will show you how to visualize your research results, frame a message that convinces your readers, and write each section of the paper. Step-by-step.

And of course – you will learn to respond the infamous Reviewer No.2.

Hey! My name is Martins Zaumanis and I am a materials scientist in Switzerland ( Google Scholar ). As the first person in my family with a PhD, I have first-hand experience of the challenges starting scientists face in academia. With this blog, I want to help young researchers succeed in academia. I call the blog “Peer Recognized”, because peer recognition is what lifts academic careers and pushes science forward.

Besides this blog, I have written the Peer Recognized book series and created the Peer Recognized Academy offering interactive online courses.

Related articles:

One comment

- Pingback: Research Paper Outline with Key Sentence Skeleton (+Paper Template)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

I want to join the Peer Recognized newsletter!

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Copyright © 2024 Martins Zaumanis

Contacts: [email protected]

Privacy Policy

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

13.1 Formatting a Research Paper

Learning objectives.

- Identify the major components of a research paper written using American Psychological Association (APA) style.

- Apply general APA style and formatting conventions in a research paper.

In this chapter, you will learn how to use APA style , the documentation and formatting style followed by the American Psychological Association, as well as MLA style , from the Modern Language Association. There are a few major formatting styles used in academic texts, including AMA, Chicago, and Turabian:

- AMA (American Medical Association) for medicine, health, and biological sciences

- APA (American Psychological Association) for education, psychology, and the social sciences

- Chicago—a common style used in everyday publications like magazines, newspapers, and books

- MLA (Modern Language Association) for English, literature, arts, and humanities

- Turabian—another common style designed for its universal application across all subjects and disciplines

While all the formatting and citation styles have their own use and applications, in this chapter we focus our attention on the two styles you are most likely to use in your academic studies: APA and MLA.

If you find that the rules of proper source documentation are difficult to keep straight, you are not alone. Writing a good research paper is, in and of itself, a major intellectual challenge. Having to follow detailed citation and formatting guidelines as well may seem like just one more task to add to an already-too-long list of requirements.

Following these guidelines, however, serves several important purposes. First, it signals to your readers that your paper should be taken seriously as a student’s contribution to a given academic or professional field; it is the literary equivalent of wearing a tailored suit to a job interview. Second, it shows that you respect other people’s work enough to give them proper credit for it. Finally, it helps your reader find additional materials if he or she wishes to learn more about your topic.

Furthermore, producing a letter-perfect APA-style paper need not be burdensome. Yes, it requires careful attention to detail. However, you can simplify the process if you keep these broad guidelines in mind:

- Work ahead whenever you can. Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” includes tips for keeping track of your sources early in the research process, which will save time later on.

- Get it right the first time. Apply APA guidelines as you write, so you will not have much to correct during the editing stage. Again, putting in a little extra time early on can save time later.

- Use the resources available to you. In addition to the guidelines provided in this chapter, you may wish to consult the APA website at http://www.apa.org or the Purdue University Online Writing lab at http://owl.english.purdue.edu , which regularly updates its online style guidelines.

General Formatting Guidelines

This chapter provides detailed guidelines for using the citation and formatting conventions developed by the American Psychological Association, or APA. Writers in disciplines as diverse as astrophysics, biology, psychology, and education follow APA style. The major components of a paper written in APA style are listed in the following box.

These are the major components of an APA-style paper:

Body, which includes the following:

- Headings and, if necessary, subheadings to organize the content

- In-text citations of research sources

- References page

All these components must be saved in one document, not as separate documents.

The title page of your paper includes the following information:

- Title of the paper

- Author’s name

- Name of the institution with which the author is affiliated

- Header at the top of the page with the paper title (in capital letters) and the page number (If the title is lengthy, you may use a shortened form of it in the header.)

List the first three elements in the order given in the previous list, centered about one third of the way down from the top of the page. Use the headers and footers tool of your word-processing program to add the header, with the title text at the left and the page number in the upper-right corner. Your title page should look like the following example.

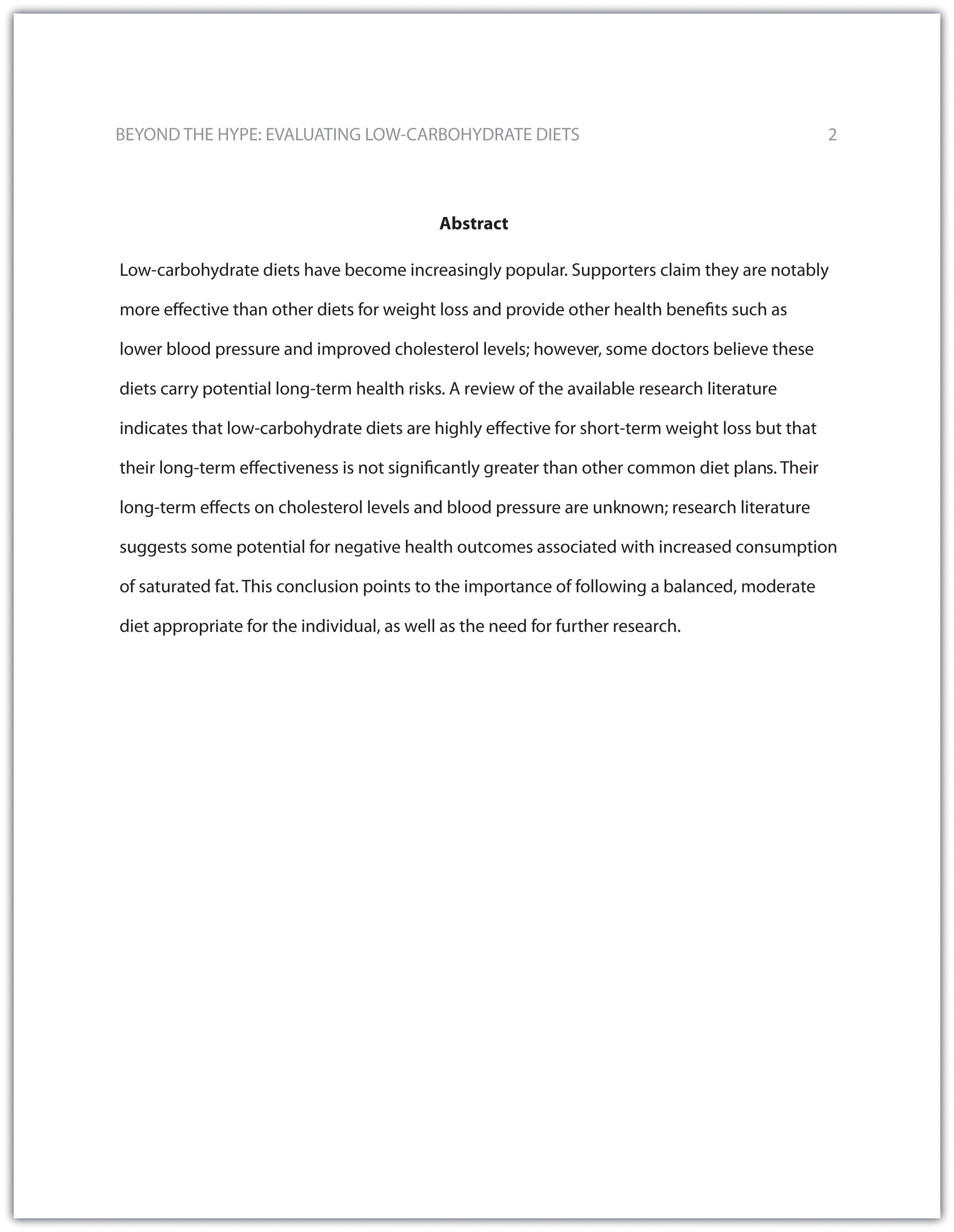

The next page of your paper provides an abstract , or brief summary of your findings. An abstract does not need to be provided in every paper, but an abstract should be used in papers that include a hypothesis. A good abstract is concise—about one hundred fifty to two hundred fifty words—and is written in an objective, impersonal style. Your writing voice will not be as apparent here as in the body of your paper. When writing the abstract, take a just-the-facts approach, and summarize your research question and your findings in a few sentences.

In Chapter 12 “Writing a Research Paper” , you read a paper written by a student named Jorge, who researched the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets. Read Jorge’s abstract. Note how it sums up the major ideas in his paper without going into excessive detail.

Write an abstract summarizing your paper. Briefly introduce the topic, state your findings, and sum up what conclusions you can draw from your research. Use the word count feature of your word-processing program to make sure your abstract does not exceed one hundred fifty words.

Depending on your field of study, you may sometimes write research papers that present extensive primary research, such as your own experiment or survey. In your abstract, summarize your research question and your findings, and briefly indicate how your study relates to prior research in the field.

Margins, Pagination, and Headings

APA style requirements also address specific formatting concerns, such as margins, pagination, and heading styles, within the body of the paper. Review the following APA guidelines.

Use these general guidelines to format the paper:

- Set the top, bottom, and side margins of your paper at 1 inch.

- Use double-spaced text throughout your paper.

- Use a standard font, such as Times New Roman or Arial, in a legible size (10- to 12-point).

- Use continuous pagination throughout the paper, including the title page and the references section. Page numbers appear flush right within your header.

- Section headings and subsection headings within the body of your paper use different types of formatting depending on the level of information you are presenting. Additional details from Jorge’s paper are provided.

Begin formatting the final draft of your paper according to APA guidelines. You may work with an existing document or set up a new document if you choose. Include the following:

- Your title page

- The abstract you created in Note 13.8 “Exercise 1”

- Correct headers and page numbers for your title page and abstract

APA style uses section headings to organize information, making it easy for the reader to follow the writer’s train of thought and to know immediately what major topics are covered. Depending on the length and complexity of the paper, its major sections may also be divided into subsections, sub-subsections, and so on. These smaller sections, in turn, use different heading styles to indicate different levels of information. In essence, you are using headings to create a hierarchy of information.

The following heading styles used in APA formatting are listed in order of greatest to least importance:

- Section headings use centered, boldface type. Headings use title case, with important words in the heading capitalized.

- Subsection headings use left-aligned, boldface type. Headings use title case.

- The third level uses left-aligned, indented, boldface type. Headings use a capital letter only for the first word, and they end in a period.

- The fourth level follows the same style used for the previous level, but the headings are boldfaced and italicized.

- The fifth level follows the same style used for the previous level, but the headings are italicized and not boldfaced.

Visually, the hierarchy of information is organized as indicated in Table 13.1 “Section Headings” .

Table 13.1 Section Headings

| Level of Information | Text Example |

|---|---|

| Level 1 | |

| Level 2 | |

| Level 3 | |

| Level 4 | |

| Level 5 |

A college research paper may not use all the heading levels shown in Table 13.1 “Section Headings” , but you are likely to encounter them in academic journal articles that use APA style. For a brief paper, you may find that level 1 headings suffice. Longer or more complex papers may need level 2 headings or other lower-level headings to organize information clearly. Use your outline to craft your major section headings and determine whether any subtopics are substantial enough to require additional levels of headings.

Working with the document you developed in Note 13.11 “Exercise 2” , begin setting up the heading structure of the final draft of your research paper according to APA guidelines. Include your title and at least two to three major section headings, and follow the formatting guidelines provided above. If your major sections should be broken into subsections, add those headings as well. Use your outline to help you.

Because Jorge used only level 1 headings, his Exercise 3 would look like the following:

| Level of Information | Text Example |

|---|---|

| Level 1 | |

| Level 1 | |

| Level 1 | |

| Level 1 |

Citation Guidelines

In-text citations.

Throughout the body of your paper, include a citation whenever you quote or paraphrase material from your research sources. As you learned in Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” , the purpose of citations is twofold: to give credit to others for their ideas and to allow your reader to follow up and learn more about the topic if desired. Your in-text citations provide basic information about your source; each source you cite will have a longer entry in the references section that provides more detailed information.

In-text citations must provide the name of the author or authors and the year the source was published. (When a given source does not list an individual author, you may provide the source title or the name of the organization that published the material instead.) When directly quoting a source, it is also required that you include the page number where the quote appears in your citation.

This information may be included within the sentence or in a parenthetical reference at the end of the sentence, as in these examples.

Epstein (2010) points out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Here, the writer names the source author when introducing the quote and provides the publication date in parentheses after the author’s name. The page number appears in parentheses after the closing quotation marks and before the period that ends the sentence.

Addiction researchers caution that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (Epstein, 2010, p. 137).

Here, the writer provides a parenthetical citation at the end of the sentence that includes the author’s name, the year of publication, and the page number separated by commas. Again, the parenthetical citation is placed after the closing quotation marks and before the period at the end of the sentence.

As noted in the book Junk Food, Junk Science (Epstein, 2010, p. 137), “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive.”

Here, the writer chose to mention the source title in the sentence (an optional piece of information to include) and followed the title with a parenthetical citation. Note that the parenthetical citation is placed before the comma that signals the end of the introductory phrase.

David Epstein’s book Junk Food, Junk Science (2010) pointed out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Another variation is to introduce the author and the source title in your sentence and include the publication date and page number in parentheses within the sentence or at the end of the sentence. As long as you have included the essential information, you can choose the option that works best for that particular sentence and source.

Citing a book with a single author is usually a straightforward task. Of course, your research may require that you cite many other types of sources, such as books or articles with more than one author or sources with no individual author listed. You may also need to cite sources available in both print and online and nonprint sources, such as websites and personal interviews. Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” , Section 13.2 “Citing and Referencing Techniques” and Section 13.3 “Creating a References Section” provide extensive guidelines for citing a variety of source types.

Writing at Work

APA is just one of several different styles with its own guidelines for documentation, formatting, and language usage. Depending on your field of interest, you may be exposed to additional styles, such as the following:

- MLA style. Determined by the Modern Languages Association and used for papers in literature, languages, and other disciplines in the humanities.

- Chicago style. Outlined in the Chicago Manual of Style and sometimes used for papers in the humanities and the sciences; many professional organizations use this style for publications as well.

- Associated Press (AP) style. Used by professional journalists.

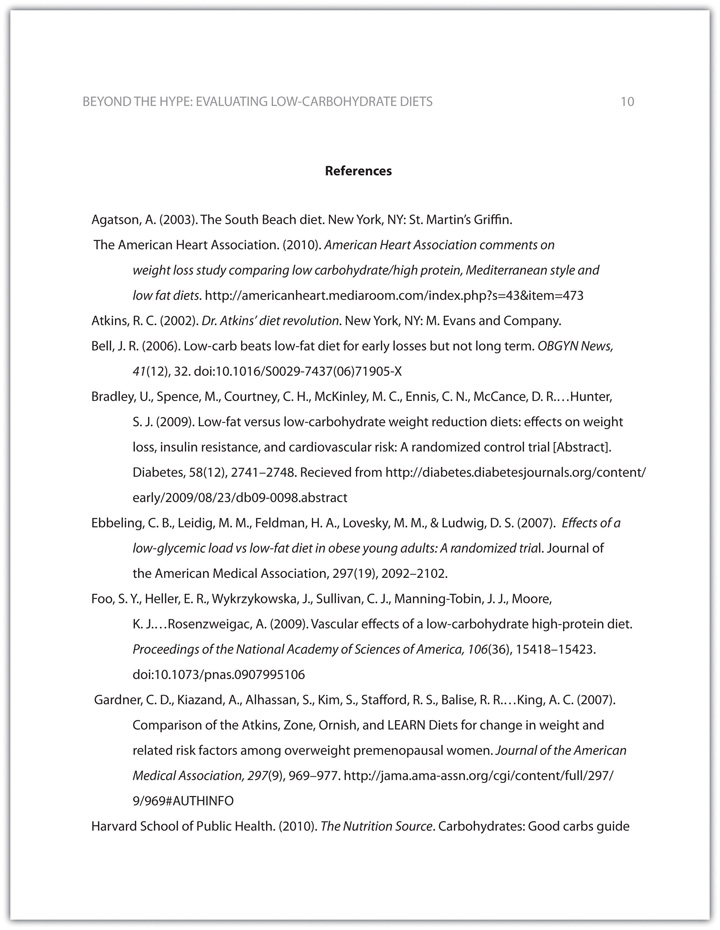

References List

The brief citations included in the body of your paper correspond to the more detailed citations provided at the end of the paper in the references section. In-text citations provide basic information—the author’s name, the publication date, and the page number if necessary—while the references section provides more extensive bibliographical information. Again, this information allows your reader to follow up on the sources you cited and do additional reading about the topic if desired.

The specific format of entries in the list of references varies slightly for different source types, but the entries generally include the following information:

- The name(s) of the author(s) or institution that wrote the source

- The year of publication and, where applicable, the exact date of publication

- The full title of the source

- For books, the city of publication

- For articles or essays, the name of the periodical or book in which the article or essay appears

- For magazine and journal articles, the volume number, issue number, and pages where the article appears

- For sources on the web, the URL where the source is located

The references page is double spaced and lists entries in alphabetical order by the author’s last name. If an entry continues for more than one line, the second line and each subsequent line are indented five spaces. Review the following example. ( Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” , Section 13.3 “Creating a References Section” provides extensive guidelines for formatting reference entries for different types of sources.)

In APA style, book and article titles are formatted in sentence case, not title case. Sentence case means that only the first word is capitalized, along with any proper nouns.

Key Takeaways

- Following proper citation and formatting guidelines helps writers ensure that their work will be taken seriously, give proper credit to other authors for their work, and provide valuable information to readers.

- Working ahead and taking care to cite sources correctly the first time are ways writers can save time during the editing stage of writing a research paper.

- APA papers usually include an abstract that concisely summarizes the paper.

- APA papers use a specific headings structure to provide a clear hierarchy of information.

- In APA papers, in-text citations usually include the name(s) of the author(s) and the year of publication.

- In-text citations correspond to entries in the references section, which provide detailed bibliographical information about a source.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Free Download

Research Paper Template

The fastest (and smartest) way to craft a research paper that showcases your project and earns you marks.

Available in Google Doc, Word & PDF format 4.9 star rating, 5000 + downloads

Step-by-step instructions

Tried & tested academic format

Fill-in-the-blanks simplicity

Pro tips, tricks and resources

What It Covers

This template’s structure is based on the tried and trusted best-practice format for academic research papers. Its structure reflects the overall research process, ensuring your paper has a smooth, logical flow from chapter to chapter. Here’s what’s included:

- The title page/cover page

- Abstract (or executive summary)

- Section 1: Introduction

- Section 2: Literature review

- Section 3: Methodology

- Section 4: Findings /results

- Section 5: Discussion

- Section 6: Conclusion

- Reference list

Each section is explained in plain, straightforward language , followed by an overview of the key elements that you need to cover within each section.

You can download a fully editable MS Word File (DOCX format), copy it to your Google Drive or paste the content to any other word processor.

download your copy

100% Free to use. Instant access.

I agree to receive the free template and other useful resources.

Download Now (Instant Access)

FAQs: Research Paper Template

What format is the template (doc, pdf, ppt, etc.).

The research paper template is provided as a Google Doc. You can download it in MS Word format or make a copy to your Google Drive. You’re also welcome to convert it to whatever format works best for you, such as LaTeX or PDF.

What types of research papers can this template be used for?

The template follows the standard best-practice structure for formal academic research papers, so it is suitable for the vast majority of degrees, particularly those within the sciences.

Some universities may have some additional requirements, but these are typically minor, with the core structure remaining the same. Therefore, it’s always a good idea to double-check your university’s requirements before you finalise your structure.

Is this template for an undergrad, Masters or PhD-level research paper?

This template can be used for a research paper at any level of study. It may be slight overkill for an undergraduate-level study, but it certainly won’t be missing anything.

How long should my research paper be?

This depends entirely on your university’s specific requirements, so it’s best to check with them. We include generic word count ranges for each section within the template, but these are purely indicative.

What about the research proposal?

If you’re still working on your research proposal, we’ve got a template for that here .

We’ve also got loads of proposal-related guides and videos over on the Grad Coach blog .

How do I write a literature review?

We have a wealth of free resources on the Grad Coach Blog that unpack how to write a literature review from scratch. You can check out the literature review section of the blog here.

How do I create a research methodology?

We have a wealth of free resources on the Grad Coach Blog that unpack research methodology, both qualitative and quantitative. You can check out the methodology section of the blog here.

Can I share this research paper template with my friends/colleagues?

Yes, you’re welcome to share this template. If you want to post about it on your blog or social media, all we ask is that you reference this page as your source.

Can Grad Coach help me with my research paper?

Within the template, you’ll find plain-language explanations of each section, which should give you a fair amount of guidance. However, you’re also welcome to consider our private coaching services .

Additional Resources

If you’re working on a research paper or report, be sure to also check these resources out…

1-On-1 Private Coaching

The Grad Coach Resource Center

The Grad Coach YouTube Channel

The Grad Coach Podcast

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

113 Great Research Paper Topics

General Education

One of the hardest parts of writing a research paper can be just finding a good topic to write about. Fortunately we've done the hard work for you and have compiled a list of 113 interesting research paper topics. They've been organized into ten categories and cover a wide range of subjects so you can easily find the best topic for you.

In addition to the list of good research topics, we've included advice on what makes a good research paper topic and how you can use your topic to start writing a great paper.

What Makes a Good Research Paper Topic?

Not all research paper topics are created equal, and you want to make sure you choose a great topic before you start writing. Below are the three most important factors to consider to make sure you choose the best research paper topics.

#1: It's Something You're Interested In

A paper is always easier to write if you're interested in the topic, and you'll be more motivated to do in-depth research and write a paper that really covers the entire subject. Even if a certain research paper topic is getting a lot of buzz right now or other people seem interested in writing about it, don't feel tempted to make it your topic unless you genuinely have some sort of interest in it as well.

#2: There's Enough Information to Write a Paper

Even if you come up with the absolute best research paper topic and you're so excited to write about it, you won't be able to produce a good paper if there isn't enough research about the topic. This can happen for very specific or specialized topics, as well as topics that are too new to have enough research done on them at the moment. Easy research paper topics will always be topics with enough information to write a full-length paper.

Trying to write a research paper on a topic that doesn't have much research on it is incredibly hard, so before you decide on a topic, do a bit of preliminary searching and make sure you'll have all the information you need to write your paper.

#3: It Fits Your Teacher's Guidelines

Don't get so carried away looking at lists of research paper topics that you forget any requirements or restrictions your teacher may have put on research topic ideas. If you're writing a research paper on a health-related topic, deciding to write about the impact of rap on the music scene probably won't be allowed, but there may be some sort of leeway. For example, if you're really interested in current events but your teacher wants you to write a research paper on a history topic, you may be able to choose a topic that fits both categories, like exploring the relationship between the US and North Korea. No matter what, always get your research paper topic approved by your teacher first before you begin writing.

113 Good Research Paper Topics

Below are 113 good research topics to help you get you started on your paper. We've organized them into ten categories to make it easier to find the type of research paper topics you're looking for.

Arts/Culture

- Discuss the main differences in art from the Italian Renaissance and the Northern Renaissance .

- Analyze the impact a famous artist had on the world.

- How is sexism portrayed in different types of media (music, film, video games, etc.)? Has the amount/type of sexism changed over the years?

- How has the music of slaves brought over from Africa shaped modern American music?

- How has rap music evolved in the past decade?

- How has the portrayal of minorities in the media changed?

Current Events

- What have been the impacts of China's one child policy?

- How have the goals of feminists changed over the decades?

- How has the Trump presidency changed international relations?

- Analyze the history of the relationship between the United States and North Korea.

- What factors contributed to the current decline in the rate of unemployment?

- What have been the impacts of states which have increased their minimum wage?

- How do US immigration laws compare to immigration laws of other countries?

- How have the US's immigration laws changed in the past few years/decades?

- How has the Black Lives Matter movement affected discussions and view about racism in the US?

- What impact has the Affordable Care Act had on healthcare in the US?

- What factors contributed to the UK deciding to leave the EU (Brexit)?

- What factors contributed to China becoming an economic power?

- Discuss the history of Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies (some of which tokenize the S&P 500 Index on the blockchain) .

- Do students in schools that eliminate grades do better in college and their careers?

- Do students from wealthier backgrounds score higher on standardized tests?

- Do students who receive free meals at school get higher grades compared to when they weren't receiving a free meal?

- Do students who attend charter schools score higher on standardized tests than students in public schools?

- Do students learn better in same-sex classrooms?

- How does giving each student access to an iPad or laptop affect their studies?

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of the Montessori Method ?

- Do children who attend preschool do better in school later on?

- What was the impact of the No Child Left Behind act?

- How does the US education system compare to education systems in other countries?

- What impact does mandatory physical education classes have on students' health?

- Which methods are most effective at reducing bullying in schools?

- Do homeschoolers who attend college do as well as students who attended traditional schools?

- Does offering tenure increase or decrease quality of teaching?

- How does college debt affect future life choices of students?

- Should graduate students be able to form unions?

- What are different ways to lower gun-related deaths in the US?

- How and why have divorce rates changed over time?

- Is affirmative action still necessary in education and/or the workplace?

- Should physician-assisted suicide be legal?

- How has stem cell research impacted the medical field?

- How can human trafficking be reduced in the United States/world?

- Should people be able to donate organs in exchange for money?

- Which types of juvenile punishment have proven most effective at preventing future crimes?

- Has the increase in US airport security made passengers safer?

- Analyze the immigration policies of certain countries and how they are similar and different from one another.

- Several states have legalized recreational marijuana. What positive and negative impacts have they experienced as a result?

- Do tariffs increase the number of domestic jobs?

- Which prison reforms have proven most effective?

- Should governments be able to censor certain information on the internet?

- Which methods/programs have been most effective at reducing teen pregnancy?

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of the Keto diet?

- How effective are different exercise regimes for losing weight and maintaining weight loss?

- How do the healthcare plans of various countries differ from each other?

- What are the most effective ways to treat depression ?

- What are the pros and cons of genetically modified foods?

- Which methods are most effective for improving memory?

- What can be done to lower healthcare costs in the US?

- What factors contributed to the current opioid crisis?

- Analyze the history and impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic .

- Are low-carbohydrate or low-fat diets more effective for weight loss?

- How much exercise should the average adult be getting each week?

- Which methods are most effective to get parents to vaccinate their children?

- What are the pros and cons of clean needle programs?

- How does stress affect the body?

- Discuss the history of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians.

- What were the causes and effects of the Salem Witch Trials?

- Who was responsible for the Iran-Contra situation?

- How has New Orleans and the government's response to natural disasters changed since Hurricane Katrina?

- What events led to the fall of the Roman Empire?

- What were the impacts of British rule in India ?

- Was the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki necessary?

- What were the successes and failures of the women's suffrage movement in the United States?

- What were the causes of the Civil War?

- How did Abraham Lincoln's assassination impact the country and reconstruction after the Civil War?

- Which factors contributed to the colonies winning the American Revolution?

- What caused Hitler's rise to power?

- Discuss how a specific invention impacted history.

- What led to Cleopatra's fall as ruler of Egypt?

- How has Japan changed and evolved over the centuries?

- What were the causes of the Rwandan genocide ?

- Why did Martin Luther decide to split with the Catholic Church?

- Analyze the history and impact of a well-known cult (Jonestown, Manson family, etc.)

- How did the sexual abuse scandal impact how people view the Catholic Church?

- How has the Catholic church's power changed over the past decades/centuries?

- What are the causes behind the rise in atheism/ agnosticism in the United States?

- What were the influences in Siddhartha's life resulted in him becoming the Buddha?

- How has media portrayal of Islam/Muslims changed since September 11th?

Science/Environment

- How has the earth's climate changed in the past few decades?

- How has the use and elimination of DDT affected bird populations in the US?

- Analyze how the number and severity of natural disasters have increased in the past few decades.

- Analyze deforestation rates in a certain area or globally over a period of time.

- How have past oil spills changed regulations and cleanup methods?

- How has the Flint water crisis changed water regulation safety?

- What are the pros and cons of fracking?

- What impact has the Paris Climate Agreement had so far?

- What have NASA's biggest successes and failures been?

- How can we improve access to clean water around the world?

- Does ecotourism actually have a positive impact on the environment?

- Should the US rely on nuclear energy more?

- What can be done to save amphibian species currently at risk of extinction?

- What impact has climate change had on coral reefs?

- How are black holes created?

- Are teens who spend more time on social media more likely to suffer anxiety and/or depression?

- How will the loss of net neutrality affect internet users?

- Analyze the history and progress of self-driving vehicles.

- How has the use of drones changed surveillance and warfare methods?

- Has social media made people more or less connected?

- What progress has currently been made with artificial intelligence ?

- Do smartphones increase or decrease workplace productivity?

- What are the most effective ways to use technology in the classroom?

- How is Google search affecting our intelligence?

- When is the best age for a child to begin owning a smartphone?

- Has frequent texting reduced teen literacy rates?

How to Write a Great Research Paper

Even great research paper topics won't give you a great research paper if you don't hone your topic before and during the writing process. Follow these three tips to turn good research paper topics into great papers.

#1: Figure Out Your Thesis Early

Before you start writing a single word of your paper, you first need to know what your thesis will be. Your thesis is a statement that explains what you intend to prove/show in your paper. Every sentence in your research paper will relate back to your thesis, so you don't want to start writing without it!

As some examples, if you're writing a research paper on if students learn better in same-sex classrooms, your thesis might be "Research has shown that elementary-age students in same-sex classrooms score higher on standardized tests and report feeling more comfortable in the classroom."

If you're writing a paper on the causes of the Civil War, your thesis might be "While the dispute between the North and South over slavery is the most well-known cause of the Civil War, other key causes include differences in the economies of the North and South, states' rights, and territorial expansion."

#2: Back Every Statement Up With Research

Remember, this is a research paper you're writing, so you'll need to use lots of research to make your points. Every statement you give must be backed up with research, properly cited the way your teacher requested. You're allowed to include opinions of your own, but they must also be supported by the research you give.

#3: Do Your Research Before You Begin Writing

You don't want to start writing your research paper and then learn that there isn't enough research to back up the points you're making, or, even worse, that the research contradicts the points you're trying to make!

Get most of your research on your good research topics done before you begin writing. Then use the research you've collected to create a rough outline of what your paper will cover and the key points you're going to make. This will help keep your paper clear and organized, and it'll ensure you have enough research to produce a strong paper.

What's Next?

Are you also learning about dynamic equilibrium in your science class? We break this sometimes tricky concept down so it's easy to understand in our complete guide to dynamic equilibrium .

Thinking about becoming a nurse practitioner? Nurse practitioners have one of the fastest growing careers in the country, and we have all the information you need to know about what to expect from nurse practitioner school .

Want to know the fastest and easiest ways to convert between Fahrenheit and Celsius? We've got you covered! Check out our guide to the best ways to convert Celsius to Fahrenheit (or vice versa).

These recommendations are based solely on our knowledge and experience. If you purchase an item through one of our links, PrepScholar may receive a commission.

Trending Now

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

ACT vs. SAT: Which Test Should You Take?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Get Your Free

Find Your Target SAT Score

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score, by an Expert Full Scorer

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading and Writing

How to Improve Your Low SAT Score

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading and Writing

Find Your Target ACT Score

Complete Official Free ACT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect ACT Score, by a 36 Full Scorer

Get a 36 on ACT English

Get a 36 on ACT Math

Get a 36 on ACT Reading

Get a 36 on ACT Science

How to Improve Your Low ACT Score

Get a 24 on ACT English

Get a 24 on ACT Math

Get a 24 on ACT Reading

Get a 24 on ACT Science

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Christine graduated from Michigan State University with degrees in Environmental Biology and Geography and received her Master's from Duke University. In high school she scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT and was named a National Merit Finalist. She has taught English and biology in several countries.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

- Weblog home

OpenScience blog

Documenting your research data along the way: tips and tools.

By Hilde van Zeeland

It happens all too often: researchers fail to use data collected by themselves or by others due to a lack of documentation. Documentation refers to information about your research data. It is meant to make your data understandable – to others who might want to reuse it, but also to your future self. Wageningen University & Research Library provides courses and advice on data documentation. In this blog post, we discuss what to document, and give tips & tools for documenting throughout the research process.

What to document?

In short, you should document all information needed to understand your data. Think of:

- General project information: title of the study, people involved and their roles, etc.

- Methodological information: methods of data collection and analysis, instrument calibrations, etc.

- Data-specific information: variable names and definitions, units of measurement, etc.

Documentation is often added to a dataset in a separate README.txt file. This page gives more information on README-files including a template you can use.

How do I document?

The trick to good documentation is to start long before you create the README-file – it’s best to document your data throughout your research. If you wait until the end, chances are that you will no longer remember what variable P2_scomF stands for, or how you got to the figures in a certain column.

A few tips for continuous documentation:

- Try a generic tool like OneNote for keeping and organising notes. You can structure these notebooks to your own research. Once you have finished your research, you can easily select the notes you wish to add to your dataset (e.g. as a README-file).

- Use an electronic lab notebook for structured documenting. Your group might have a shared e-lab notebook tool you can use. One example is eLabJournal .

- If you use a proprietary software such as OneNote or a e-lab notebook, make sure to export or convert your documentation to an open file format when you make it available to others. This way, people do not need the original software to open the files – and the files will remain readable even if the software becomes obsolete.

- Do you work with spreadsheets? The free tool Colectica for Excel allows you to add documentation to your spreadsheets. Think of the explanation of variables and code lists. You can also export these to create separate documentation files.

- If you work with scripting languages, such as R or Python, take a look at Jupyter Notebook . With this free, web-based tool you create one single document showing code snippets and their results in place. This provides a step-by-step overview of your data processing and analysis. Find examples of Jupyter notebooks by research domain here . This page also provides a list of journal articles with documentation in Jupyter notebooks.

Put it to the test!

How do you know if your final documentation is understandable to others? Put it to the test! Simply give your dataset with documentation to somebody else. If this person has trouble understanding your data, there’s room for improvement. Of course you can always contact Data Management Support if you need help.

Good luck documenting your data!

Join the new Research Data Management group on Intranet for more tips & tricks, events, and other data info.

Related posts:

- Create more impact: dare to share your research data

- 10 Tweets on The Making of… Research Data Management Policy

- Wageningen Economic Research: secure data storing and sharing

- Data Management Plan Requirements of Public Funding Agencies

View articles

There are 2 comments.

[…] Management Support gives tips and tools for documenting data along the research […]

[…] facilitates and encourages reuse of his data. For details on data documentation, read this page and blog post – or contact our data librarian, who can also help you create documentation if you archive with […]

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Instant insights, infinite possibilities

How to write a research plan: Step-by-step guide

Last updated

30 January 2024

Reviewed by

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Today’s businesses and institutions rely on data and analytics to inform their product and service decisions. These metrics influence how organizations stay competitive and inspire innovation. However, gathering data and insights requires carefully constructed research, and every research project needs a roadmap. This is where a research plan comes into play.

Read this step-by-step guide for writing a detailed research plan that can apply to any project, whether it’s scientific, educational, or business-related.

- What is a research plan?

A research plan is a documented overview of a project in its entirety, from end to end. It details the research efforts, participants, and methods needed, along with any anticipated results. It also outlines the project’s goals and mission, creating layers of steps to achieve those goals within a specified timeline.

Without a research plan, you and your team are flying blind, potentially wasting time and resources to pursue research without structured guidance.

The principal investigator, or PI, is responsible for facilitating the research oversight. They will create the research plan and inform team members and stakeholders of every detail relating to the project. The PI will also use the research plan to inform decision-making throughout the project.

- Why do you need a research plan?

Create a research plan before starting any official research to maximize every effort in pursuing and collecting the research data. Crucially, the plan will model the activities needed at each phase of the research project .

Like any roadmap, a research plan serves as a valuable tool providing direction for those involved in the project—both internally and externally. It will keep you and your immediate team organized and task-focused while also providing necessary definitions and timelines so you can execute your project initiatives with full understanding and transparency.

External stakeholders appreciate a working research plan because it’s a great communication tool, documenting progress and changing dynamics as they arise. Any participants of your planned research sessions will be informed about the purpose of your study, while the exercises will be based on the key messaging outlined in the official plan.

Here are some of the benefits of creating a research plan document for every project:

Project organization and structure

Well-informed participants

All stakeholders and teams align in support of the project

Clearly defined project definitions and purposes

Distractions are eliminated, prioritizing task focus

Timely management of individual task schedules and roles

Costly reworks are avoided

- What should a research plan include?

The different aspects of your research plan will depend on the nature of the project. However, most official research plan documents will include the core elements below. Each aims to define the problem statement , devising an official plan for seeking a solution.

Specific project goals and individual objectives

Ideal strategies or methods for reaching those goals

Required resources

Descriptions of the target audience, sample sizes , demographics, and scopes

Key performance indicators (KPIs)

Project background

Research and testing support

Preliminary studies and progress reporting mechanisms

Cost estimates and change order processes

Depending on the research project’s size and scope, your research plan could be brief—perhaps only a few pages of documented plans. Alternatively, it could be a fully comprehensive report. Either way, it’s an essential first step in dictating your project’s facilitation in the most efficient and effective way.

- How to write a research plan for your project

When you start writing your research plan, aim to be detailed about each step, requirement, and idea. The more time you spend curating your research plan, the more precise your research execution efforts will be.

Account for every potential scenario, and be sure to address each and every aspect of the research.

Consider following this flow to develop a great research plan for your project:

Define your project’s purpose

Start by defining your project’s purpose. Identify what your project aims to accomplish and what you are researching. Remember to use clear language.

Thinking about the project’s purpose will help you set realistic goals and inform how you divide tasks and assign responsibilities. These individual tasks will be your stepping stones to reach your overarching goal.

Additionally, you’ll want to identify the specific problem, the usability metrics needed, and the intended solutions.

Know the following three things about your project’s purpose before you outline anything else:

What you’re doing

Why you’re doing it

What you expect from it

Identify individual objectives

With your overarching project objectives in place, you can identify any individual goals or steps needed to reach those objectives. Break them down into phases or steps. You can work backward from the project goal and identify every process required to facilitate it.

Be mindful to identify each unique task so that you can assign responsibilities to various team members. At this point in your research plan development, you’ll also want to assign priority to those smaller, more manageable steps and phases that require more immediate or dedicated attention.

Select research methods

Once you have outlined your goals, objectives, steps, and tasks, it’s time to drill down on selecting research methods . You’ll want to leverage specific research strategies and processes. When you know what methods will help you reach your goals, you and your teams will have direction to perform and execute your assigned tasks.

Research methods might include any of the following:

User interviews : this is a qualitative research method where researchers engage with participants in one-on-one or group conversations. The aim is to gather insights into their experiences, preferences, and opinions to uncover patterns, trends, and data.

Field studies : this approach allows for a contextual understanding of behaviors, interactions, and processes in real-world settings. It involves the researcher immersing themselves in the field, conducting observations, interviews, or experiments to gather in-depth insights.

Card sorting : participants categorize information by sorting content cards into groups based on their perceived similarities. You might use this process to gain insights into participants’ mental models and preferences when navigating or organizing information on websites, apps, or other systems.

Focus groups : use organized discussions among select groups of participants to provide relevant views and experiences about a particular topic.

Diary studies : ask participants to record their experiences, thoughts, and activities in a diary over a specified period. This method provides a deeper understanding of user experiences, uncovers patterns, and identifies areas for improvement.

Five-second testing: participants are shown a design, such as a web page or interface, for just five seconds. They then answer questions about their initial impressions and recall, allowing you to evaluate the design’s effectiveness.

Surveys : get feedback from participant groups with structured surveys. You can use online forms, telephone interviews, or paper questionnaires to reveal trends, patterns, and correlations.

Tree testing : tree testing involves researching web assets through the lens of findability and navigability. Participants are given a textual representation of the site’s hierarchy (the “tree”) and asked to locate specific information or complete tasks by selecting paths.

Usability testing : ask participants to interact with a product, website, or application to evaluate its ease of use. This method enables you to uncover areas for improvement in digital key feature functionality by observing participants using the product.

Live website testing: research and collect analytics that outlines the design, usability, and performance efficiencies of a website in real time.

There are no limits to the number of research methods you could use within your project. Just make sure your research methods help you determine the following:

What do you plan to do with the research findings?

What decisions will this research inform? How can your stakeholders leverage the research data and results?

Recruit participants and allocate tasks

Next, identify the participants needed to complete the research and the resources required to complete the tasks. Different people will be proficient at different tasks, and having a task allocation plan will allow everything to run smoothly.

Prepare a thorough project summary

Every well-designed research plan will feature a project summary. This official summary will guide your research alongside its communications or messaging. You’ll use the summary while recruiting participants and during stakeholder meetings. It can also be useful when conducting field studies.

Ensure this summary includes all the elements of your research project . Separate the steps into an easily explainable piece of text that includes the following:

An introduction: the message you’ll deliver to participants about the interview, pre-planned questioning, and testing tasks.

Interview questions: prepare questions you intend to ask participants as part of your research study, guiding the sessions from start to finish.

An exit message: draft messaging your teams will use to conclude testing or survey sessions. These should include the next steps and express gratitude for the participant’s time.

Create a realistic timeline

While your project might already have a deadline or a results timeline in place, you’ll need to consider the time needed to execute it effectively.

Realistically outline the time needed to properly execute each supporting phase of research and implementation. And, as you evaluate the necessary schedules, be sure to include additional time for achieving each milestone in case any changes or unexpected delays arise.

For this part of your research plan, you might find it helpful to create visuals to ensure your research team and stakeholders fully understand the information.

Determine how to present your results

A research plan must also describe how you intend to present your results. Depending on the nature of your project and its goals, you might dedicate one team member (the PI) or assume responsibility for communicating the findings yourself.

In this part of the research plan, you’ll articulate how you’ll share the results. Detail any materials you’ll use, such as:

Presentations and slides

A project report booklet

A project findings pamphlet

Documents with key takeaways and statistics

Graphic visuals to support your findings

- Format your research plan

As you create your research plan, you can enjoy a little creative freedom. A plan can assume many forms, so format it how you see fit. Determine the best layout based on your specific project, intended communications, and the preferences of your teams and stakeholders.

Find format inspiration among the following layouts:

Written outlines

Narrative storytelling

Visual mapping

Graphic timelines

Remember, the research plan format you choose will be subject to change and adaptation as your research and findings unfold. However, your final format should ideally outline questions, problems, opportunities, and expectations.

- Research plan example

Imagine you’ve been tasked with finding out how to get more customers to order takeout from an online food delivery platform. The goal is to improve satisfaction and retain existing customers. You set out to discover why more people aren’t ordering and what it is they do want to order or experience.

You identify the need for a research project that helps you understand what drives customer loyalty . But before you jump in and start calling past customers, you need to develop a research plan—the roadmap that provides focus, clarity, and realistic details to the project.

Here’s an example outline of a research plan you might put together:

Project title

Project members involved in the research plan

Purpose of the project (provide a summary of the research plan’s intent)

Objective 1 (provide a short description for each objective)

Objective 2

Objective 3

Proposed timeline

Audience (detail the group you want to research, such as customers or non-customers)

Budget (how much you think it might cost to do the research)

Risk factors/contingencies (any potential risk factors that may impact the project’s success)

Remember, your research plan doesn’t have to reinvent the wheel—it just needs to fit your project’s unique needs and aims.

Customizing a research plan template