Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1: The Speech Communication Process

The Speech Communication Process

- Listener(s)

Interference

As you might imagine, the speaker is the crucial first element within the speech communication process. Without a speaker, there is no process. The speaker is simply the person who is delivering, or presenting, the speech. A speaker might be someone who is training employees in your workplace. Your professor is another example of a public speaker as s/he gives a lecture. Even a stand-up comedian can be considered a public speaker. After all, each of these people is presenting an oral message to an audience in a public setting. Most speakers, however, would agree that the listener is one of the primary reasons that they speak.

The listener is just as important as the speaker; neither one is effective without the other. The listener is the person or persons who have assembled to hear the oral message. Some texts might even call several listeners an “audience. ” The listener generally forms an opinion as to the effectiveness of the speaker and the validity of the speaker’s message based on what they see and hear during the presentation. The listener’s job sometimes includes critiquing, or evaluating, the speaker’s style and message. You might be asked to critique your classmates as they speak or to complete an evaluation of a public speaker in another setting. That makes the job of the listener extremely important. Providing constructive feedback to speakers often helps the speaker improve her/his speech tremendously.

Another crucial element in the speech process is the message. The message is what the speaker is discussing or the ideas that s/he is presenting to you as s/he covers a particular topic. The important chapter concepts presented by your professor become the message during a lecture. The commands and steps you need to use, the new software at work, are the message of the trainer as s/he presents the information to your department. The message might be lengthy, such as the President’s State of the Union address, or fairly brief, as in a five-minute presentation given in class.

The channel is the means by which the message is sent or transmitted. Different channels are used to deliver the message, depending on the communication type or context. For instance, in mass communication, the channel utilized might be a television or radio broadcast. The use of a cell phone is an example of a channel that you might use to send a friend a message in interpersonal communication. However, the channel typically used within public speaking is the speaker’s voice, or more specifically, the sound waves used to carry the voice to those listening. You could watch a prerecorded speech or one accessible on YouTube, and you might now say the channel is the television or your computer. This is partially true. However, the speech would still have no value if the speaker’s voice was not present, so in reality, the channel is now a combination of the two -the speaker’s voice broadcast through an electronic source.

The context is a bit more complicated than the other elements we have discussed so far. The context is more than one specific component. For example, when you give a speech in your classroom, the classroom, or the physical location of your speech, is part of the context . That’s probably the easiest part of context to grasp.

But you should also consider that the people in your audience expect you to behave in a certain manner, depending on the physical location or the occasion of the presentation . If you gave a toast at a wedding, the audience wouldn’t be surprised if you told a funny story about the couple or used informal gestures such as a high-five or a slap on the groom’s back. That would be acceptable within the expectations of your audience, given the occasion. However, what if the reason for your speech was the presentation of a eulogy at a loved one’s funeral? Would the audience still find a high-five or humor as acceptable in that setting? Probably not. So the expectations of your audience must be factored into context as well.

The cultural rules -often unwritten and sometimes never formally communicated to us -are also a part of the context. Depending on your culture, you would probably agree that there are some “rules ” typically adhered to by those attending a funeral. In some cultures, mourners wear dark colors and are somber and quiet. In other cultures, grieving out loud or beating one’s chest to show extreme grief is traditional. Therefore, the rules from our culture -no matter what they are -play a part in the context as well.

Every speaker hopes that her/his speech is clearly understood by the audience. However, there are times when some obstacle gets in the way of the message and interferes with the listener’s ability to hear what’s being said. This is interference , or you might have heard it referred to as “noise. ” Every speaker must prepare and present with the assumption that interference is likely to be present in the speaking environment.

Interference can be mental, physical, or physiological. Mental interference occurs when the listener is not fully focused on what s/he is hearing due to her/his own thoughts. If you’ve ever caught yourself daydreaming in class during a lecture, you’re experiencing mental interference. Your own thoughts are getting in the way of the message.

A second form of interference is physical interference . This is noise in the literal sense -someone coughing behind you during a speech or the sound of a mower outside the classroom window. You may be unable to hear the speaker because of the surrounding environmental noises.

The last form of interference is physiological . This type of interference occurs when your body is responsible for the blocked signals. A deaf person, for example, has the truest form of physiological interference; s/he may have varying degrees of difficulty hearing the message. If you’ve ever been in a room that was too cold or too hot and found yourself not paying attention, you’re experiencing physiological interference. Your bodily discomfort distracts from what is happening around you.

The final component within the speech process is feedback. While some might assume that the speaker is the only one who sends a message during a speech, the reality is that the listeners in the audience are sending a message of their own, called feedback . Often this is how the speaker knows if s/he is sending an effective message. Occasionally the feedback from listeners comes in verbal form – questions from the audience or an angry response from a listener about a key point presented. However, in general, feedback during a presentation is typically non-verbal -a student nodding her/his head in agreement or a confused look from an audience member. An observant speaker will scan the audience for these forms of feedback, but keep in mind that non-verbal feedback is often more difficult to spot and to decipher. For example, is a yawn a sign of boredom, or is it simply a tired audience member?

Generally, all of the above elements are present during a speech. However, you might wonder what the process would look like if we used a diagram to illustrate it. Initially, some students think of public speaking as a linear process -the speaker sending a message to the listener -a simple, straight line. But if you’ll think about the components we’ve just covered, you begin to see that a straight line cannot adequately represent the process, when we add listener feedback into the process. The listener is sending her/his own message back to the speaker, so perhaps the process might better be represented as circular. Add in some interference and place the example in context, and you have a more complete idea of the speech process.

Fundamentals of Public Speaking Copyright © by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

What is a Rhetorical Situation?

Using the Power of Language to Persuade, Inform, and Inspire

ThoughtCo / Ran Zheng

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Understanding the use of rhetoric can help you speak convincingly and write persuasively—and vice versa. At its most basic level, rhetoric is defined as communication —whether spoken or written, predetermined or extemporaneous—that’s aimed at getting your intended audience to modify their perspective based on what you’re telling them and how you’re telling it to them.

One of the most common uses of rhetoric we see is in politics. Candidates use carefully crafted language—or messaging—to appeal to their audiences’ emotions and core values in an attempt to sway their vote. However, because the purpose of rhetoric is a form of manipulation , many people have come to equate it with fabrication, with little or no regard to ethical concerns. (There’s an old joke that goes: Q: How do you know when a politician is lying? A: His lips are moving. )

While some rhetoric is certainly far from fact-based, the rhetoric itself is not the issue. Rhetoric is about making the linguistic choices that will have the most impact. The author of the rhetoric is responsible for the veracity of its content, as well as the intent—whether positive or negative—of the outcome he or she is attempting to achieve.

The History of Rhetoric

Probably the most influential pioneer in establishing the art of rhetoric itself was the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle , who defined it as “an ability, in each particular case, to see the available means of persuasion.” His treatise detailing the art of persuasion, “On Rhetoric,” dates from the 4th century BCE. Cicero and Quintilian, two of the most famous Roman teachers of rhetoric, often relied on elements culled from Aristotle’s precepts in their own work.

Aristotle explained how rhetoric functions using five core concepts: logos , ethos , pathos , kairos, and telos and much of rhetoric as we know it today is still based on these principles. In the last few centuries, the definition of “rhetoric” has shifted to encompass pretty much any situation in which people exchange ideas. Because each of us has been informed by a unique set of life circumstances, no two people see things in exactly the same way. Rhetoric has become a way not only to persuade but to use language in an attempt to create mutual understanding and facilitate consensus.

Fast Facts: Aristotle's Five Core Concepts of Rhetoric

- Logos: Often translated as “logic or reasoning,” logos originally referred to how a speech was organized and what it contained but is now more about content and structural elements of a text.

- Ethos: Ethos translates as “credibility or trustworthiness,” and refers to the character a speaker or author and how they portray themselves through words.

- Pathos: Pathos is the element of language designed to play to the emotional sensibilities of an intended audience, and geared toward using the audience’s own attitudes to incite agreement or action.

- Telos: Telos refers to the particular purpose a speaker or author hopes to achieve, even though the goals and attitude of the speaker may differ vastly from those of his or her audience.

- Kairos: Loosely translated, kairos means “setting” and deals with the time and place that a speech takes place and how that setting may influence its outcome.

Elements of a Rhetorical Situation

What exactly is a rhetorical situation ? An impassioned love letter, a prosecutor's closing statement, an advertisement hawking the next needful thing you can't possibly live without—are all examples of rhetorical situations. As different as their content and intent may be, all of them have the same five basic underlying principles:

- The text , which is the actual communication, whether written or spoken

- The author , which is the person who creates a specific communication

- The audience , who is the recipient of a communication

- The purpose(s) , which are the various reasons for authors and audiences to engage in communication

- The setting , which is the time, place, and environment that surrounds a particular communication

Each of these elements has an impact on the eventual outcome of any rhetorical situation. If a speech is poorly written, it may be impossible to persuade the audience of its validity or worth, or if its author lacks credibility or passion the result may be the same. On the other hand, even the most eloquent speaker can fail to move an audience that is firmly set in a belief system that directly contradicts the goal the author hopes to achieve and is unwilling to entertain another point of view. Finally, as the saying implies, "timing is everything." The when, where, and prevailing mood surrounding a rhetorical situation can greatly influence its eventual outcome.

While the most commonly accepted definition of a text is a written document, when it comes to rhetorical situations, a text can take on any form of communication a person intentionally creates. If you think of communication in terms of a road trip, the text is the vehicle that gets you to your desired destination—depending on the driving conditions and whether or not you have enough fuel to go the distance. There are three basic factors that have the biggest influence on the nature of any given text: the medium in which it’s delivered, the tools that are used to create it, and the tools required to decipher it:

- The Medium —Rhetorical texts can take the form of pretty much any and every kind of media that people use to communicate. A text can be a hand-written love poem; a cover letter that’s typed, or a personal dating profile that’s computer-generated. Text can encompass works in the audio, visual, spoken-word, verbal, non-verbal, graphic, pictorial, and tactile realms, to name but a few. Text can take the form of a magazine ad, a PowerPoint presentation, a satirical cartoon, a film, a painting, a sculpture, a podcast, or even your latest Facebook post, Twitter tweet, or Pinterest pin.

- The Author’s Toolkit (Creating) —The tools required to author any form of text impact its structure and content. From the very rudimentary anatomical tools humans use to produce speech (lips, mouth, teeth, tongue, and so forth) to the latest high-tech gadget, the tools we choose to create our communication can help make or break the final outcome.

- Audience Connectivity (Deciphering) —Just as an author requires tools to create, an audience must have the capability to receive and understand the information that a text communicates, whether via reading, viewing, hearing, or other forms of sensory input. Again, these tools can range from something as simple as eyes to see or ears to hear to something as complex as sophisticated as an electron microscope. In addition to physical tools, an audience often requires conceptual or intellectual tools to fully comprehend the meaning of a text. For instance, while the French national anthem, “La Marseillaise,” may be a rousing song on its musical merits alone, if you don’t speak French, the meaning and importance of the lyrics are lost.

Loosely speaking, an author is a person who creates text to communicate. Novelists, poets, copywriters, speechwriters, singer/songwriters, and graffiti artists are all authors. Each author is influenced by his or her individual background. Factors such as age, gender identification, geographic location, ethnicity, culture, religion, socio-economic condition, political beliefs, parental pressure, peer involvement, education, and personal experience create the assumptions authors use to see the world, as well as the way in which they communicate to an audience and the setting in which they are likely to do so.

The Audience

The audience is the recipient of the communication. The same factors that influence an author also influence an audience, whether that audience is a single person or a stadium crowd, the audience’s personal experiences affect how they receive communication, especially with regard to the assumptions they may make about the author, and the context in which they receive the communication.

There are as many reasons to communicate messages as there are authors creating them and audiences who may or may not wish to receive them, however, authors and audiences bring their own individual purposes to any given rhetorical situation. These purposes may be conflicting or complementary.

The authors’ purpose in communicating is generally to inform, to instruct, or to persuade. Some other author goals may include to entertain, startle, excite, sadden, enlighten, punish, console, or inspire the intended audience. The purpose of the audience to become informed, to be entertained, to form a different understanding, or to be inspired. Other audience takeaways may include excitement, consolation, anger, sadness, remorse, and so on.

As with purpose, the attitude of both the author and the audience can have a direct impact on the outcome of any rhetorical situation. Is the author rude and condescending, or funny and inclusive? Does he or she appear knowledgeable on the subject on which they’re speaking, or are they totally out of their depth? Factors such as these ultimately govern whether or not the audience understands, accepts, or appreciates the author’s text.

Likewise, audiences bring their own attitudes to the communication experience. If the communication is undecipherable, boring, or of a subject that holds no interest, the audience will likely not appreciate it. If it’s something to which they are attuned or piques their curiosity, the author’s message may be well received.

Every rhetorical situation happens in a specific setting within a specific context, and are all constrained by the time and environment in which they occur. Time, as in a specific moment in history, forms the zeitgeist of an era. Language is directly affected by both historical influence and the assumptions brought to bear by the current culture in which it exists. Theoretically, Stephen Hawking and Sir Isaac Newton could have had a fascinating conversation on the galaxy, however, the lexicon of scientific information available to each during his lifetime would likely have influenced the conclusions they reached as a result.

The specific place that an author engages his or her audience also affects the manner in which a text is both created and received. Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I have a Dream” speech, delivered to a rapt crowd on August 28, 1963, is considered by many as one of the most memorable pieces of American rhetoric of the 20 th century, but a setting doesn’t have to be public, or an audience large for communication to have a profound impact. Intimate settings, in which information is exchanged, such as a doctor’s office or promises are made—perhaps on a moonlit balcony—can serve as the backdrop for life-changing communication.

In some rhetorical contexts, the term “community” refers to a specific group united by like interests or concerns rather than a geographical neighborhood. Conversation, which most often refers to a dialog between a limited number of people takes on a much broader meaning to and refers to a collective conversation which encompasses a broad understanding, belief system, or assumptions that are held by the community at large.

- Constraints: Definition and Examples in Rhetoric

- Audience Analysis in Speech and Composition

- Exigence in Rhetoric

- An Overview of Classical Rhetoric

- The Implied Audience

- Rhetorical Analysis Definition and Examples

- What Is a Message in Communication?

- Rhetoric: Definitions and Observations

- Definition of Audience

- Word Choice in English Composition and Literature

- Situated Ethos in Rhetoric

- The Meaning of Rhetor

- Use Social Media to Teach Ethos, Pathos and Logos

- Definition and Examples of Paragraphing in Essays

- Common Ground in Rhetoric

- Definition and Examples of Rhetorical Stance

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, rhetorical situation.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

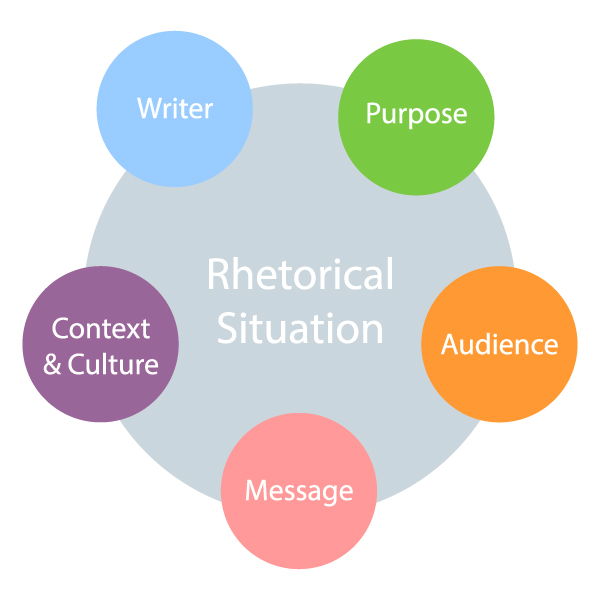

The rhetorical situation refers to the contextual variables (e.g. audience , purpose , and topic ) that influence composing and interpretation . Learn how to engage in rhetorical analysis of your rhetorical situation so you can create texts that your readers find to be clear and cogent, even if they don't necessarily agree with your argument , thesis , research question or hypothesis.

What is the Rhetorical Situation?

The rhetorical situation refers to

- Exigence — the driving force behind the call to write or speak. It’s the situation that prompts the need for communication , urging the speaker or writer to use discourse to respond to a particular matter

- Audience — the specific individuals or groups (aka discourse communities) to whom the discourse is directed

- Constraints — the effects of rhetorical affordances and constraints on communication, composing and style

The Rhetorical Situation may also be called occasion; rhetorical situation ; rhetorical occasion ; situational constraints; the spin room; the no-spin room, the communication situation.

Rhetorical Situations are sometimes described as formal, semi-formal, or informal. They may also be described as home-based, school-based, or work-based .

Related Concepts: Epistemology ; Rhetoric ; Rhetorical Analysis ; Rhetorical Stance

We are always situated, in situations, in the world, in a context, living in a certain way with others, trying to achieve this and avoid that. Eugene Gendlin, p.2

Why Does the Rhetorical Situation Matter?

Writers, speakers, and knowledge workers . . . need a robust understanding of the rhetorical situation in order to respond appropriately to an exigency , a call for discourse.

Having “rhetorical knowledge” and being able to In order to determine the available means of persuasion., successful communicators analyze their rhetorical situation .

Rhetorical Theory has been a major subject of study and conversation among writers and speakers since the 5th century BCE, when sophists taught persuasive techniques to young aristocrats who hoped to succeed in legal and political arenas. Rhetorical theories provide insights into ways writers and speakers can craft their messages so they are persuasive.

Rhetorical theory has had a profound impact on writing instruction in the U.S. The CWPA (Council of Writing Program Administrators) defines rhetorical knowledge as a foundational competency in college-level writing:

“The assertion that writing is “rhetorical” means that writing is always shaped by a combination of the purposes and expectations of writers and readers and the uses that writing serves in specific contexts. To be rhetorically sensitive, good writers must be flexible. They should be able to pursue their purposes by consciously adapting their writing both to the contexts in which it will be read and to the expectations, knowledge, experiences, values, and beliefs of their readers. They also must understand how to take advantage of the opportunities with which they are presented and to address the constraints they encounter as they write. In practice, this means that writers learn to identify what is possible and not possible in diverse writing situations. Writing an email to a friend holds different possibilities for language and form than does writing a lab report for submission to an instructor in a biology class. Instructors emphasize the rhetorical nature of writing by providing writers opportunities to study the expectations, values, and norms associated with writing in specific contexts. This principle is fundamental to the study of writing and writing instruction. It informs all other principles in this document” (Conference 2015).

What is Rhetorical Analysis?

Since antiquity, rhetoricians have exhorted writers and speakers to think deeply and carefully about their audience , purpose , and topic . In the rhetorical tradition, this process—this activity of considering what you want to say, your purpose , and then adjusting what you want to say based on your evaluation of your audience —is called rhetorical analysis .

Rhetorical Analysis begins with a careful consideration of the contextual variables that need to be considered to respond with clarity and persuasion to the communication situation.

Scholarly conversations about what those contextual variables are have evolved over time.

Loyd Bitzer’s Rhetorical Model

In 1968, Loyd Bitzer, a rhetorician, articulated a theoretical model of the rhetorical situation.

Bitzer depicts the rhetorical situation as

- “a complex of persons, events, objects, and relations presenting an actual or potential exigence [emphasis added] which can be completely or partially removed if discourse, introduced into the situation, can so constrain human decision or action as to bring about the significant modification of the exigence” (p.9).

Thus, Bitzer imagines the rhetorical situation as a dynamic between three primary forces:

- Constraints

For Bitzer, the impetus for writing or speaking is the situation:

- “Rhetorical discourse is called into existence by situation” (p. 9).

- The situation gives rise to an exigency , which is “an imperfection marked by urgency; it is a defect, an obstacle, something waiting to be done, a thing that is other than it should be” (p. 6)

Moreover, Bitzer argues the situation presumes a response:

- “the situation dictates the sorts of observations to be made; it dictates the significant physical and verbal responses. . . .” (p. 5)

Bitzer’s theory of the rhetorical situation, published as the first article in a new academic journal ( Rhetoric and Philosophy ) initiated an academic conversation that is still ongoing. To this day, Bitzer is credited for introducing the concept of exigency and for questioning how constraints — persons, events, objects, and relations –impinge on composing.

Furthermore, Bitzer deserves credit for introducing the notion that writing occurs in a sociocultural context–i.e., that there are rhetorical constraints that exist in the material world that shape how writers and speakers should respond to exigencies, situations.

However, in contemporary Writing Studies (as well as other academic disciplines), Bitzer’s argument that “Rhetorical discourse is called into existence by situation” (p. 9) has been disputed on theoretical and empirical grounds :

- Empirical Grounds Bitzer’s model presumes that the writer or speaker lacks agency, that they are merely reactive to situations, that the situation determines whether or not something is translated to discourse/text or not. In contrast to this view, empirical research has found that writers and speakers bring their own agendas and desires to writing situations. When people enter a new rhetorical situation, they have aims/purposes, personalities, literacy histories, past experiences. All of those histories and more shape the their perception of the rhetorical situation, their invention, research, and reasoning processes. Rhetors experience an incessant flow of occasions and problems during their lives. And it is the rhetor who chooses to focus on any one particular rhetorical situation.

- linguistic constraints

- material constraints (e.g., timing, economics, governments, technology)

- ideological constraints (especially gender, class, and race).

The Ecological Model

From the 1980s to 2000s, scholars from across disciplines (e.g., Rhetoric, Writing Studies, Gender Studies, and Philosophy) further problematized models of the rhetorical situation that

- implied communication is a simple process of transmitting a message, information, from sender to receiver

- portrayed rhetorical situations as “unique, unconnected with other situations” (Cooper, p. 367).

- oversimplified ways interpretation is an act of imagination, a social construction.

By the close of the 20th century, thanks to postmodernism , constructivism , and feminism , the discipline of Writing Studies embraced a new theory of the rhetorical situation: the ecological model.

The ecological model conceptualizes the rhetorical situation as composed of a universe of variables that interact with one another, rhetors, and audiences. Thus, rather than conceptualizing the rhetorical situation as a one-to-one dialog between the writer and the writer’s audience, the ecological model attempts to conceptualize the rhetorical situation with greater complexity–i.e., as a milieu of rhetorical elements that occur in a multi-dimensional space.

First introduced to Writing Studies by Greg Myers (1985) and then developed by Marilyn Cooper (1986), the ecological model of the rhetorical situation assumes “writing is an activity through which a person is continually engaged with a variety of socially constituted systems” Cooper p. 367).

“The metaphor for writing suggested by the ecological model is that of a web, in which anything that affects one strand of the web vibrates throughout the whole” (Cooper p, 370).

Rather than debate either the situation invokes the rhetoric or the writer/speaker invokes the rhetoric, the ecological view assumes both the rhetor and the sociocultural context are in dialog, in co-creation with one another:

“all organisms–but especially human beings-are not simply the results but are also the causes of their own environments. . . . While it may be true that at some instant the environment poses a problem or challenge to the organism, in the process of response to that challenge the organism alters the terms of its relation to the outer world and recreates the relevant aspects of that world. The relation between organism and environment is not simply one of interaction of internal and external factors, but of a dialectical development of organism and milieu in response to each other. (Lewontin et al ., p. 275)

The Psychological Model

In psychology, the STEM community, and the learning sciences, investigators explore the role of mindset and personality on interpretation , creativity, and composing .

For example, research has found that people’s mindset about their competencies as writers and public speakers influence how they interact with rhetorical situations. People who hold a growth mindset about their potential as writers and communicators are more likely than people who hold a fixed mindset to engage in rhetorical analysis and rhetorical reasoning . Being preoccupied with negative thoughts when composing makes writing aversive.

Being intellectually open is crucial to putting aside one’s own perspective and living in the shoes of the Other . Being narrow minded about a topic undermines efforts at research, rhetorical analysis and rhetorical reasoning . Being able to engage in metacognition & self-regulation is crucial to successfully navigating rhetorical contexts. We all don’t know what we don’t know. That’s unavoidable, that’s human. However, openness , metacognition and regulation are needed to question how our own experiences and observations shape our interpretations, research methods , and knowledge claims.

So, on the Topic of the Rhetorical Situation, What’s Next?

Moving forward, as bots emerge, as Artificial Intelligence reaches consciousness, technorhetoricians are beginning to explore ways nonhuman elements enter the communication situation and assert agency.

Bitzer, Lloyd. (1968). “The Rhetorical Situation.” Philosophy and Rhetoric 1:1: 1-14.

Gendlin, Eugene T (1978). “Befindlichkeit: Heidegger and the philosophy of psychology” (PDF) . Review of Existential Psychology and Psychiatry . 16 (1–3): 43–71.

Lewontin, R. C., Steven Rose, and Leon J. Kamin. Not in Our Genes: Biology, Ideology, and Human Nature. New York: Pantheon Books, 1984.

Marilyn M. Cooper College English , Vol. 48, No. 4 (Apr., 1986), pp. 364-375

Myers, Greg. “The Social Construction of Two Biologists’ Proposals.” Written Communication 2 (1985): 219-45.

Vatz, Richard (1973). “The Myth of the Rhetorical Situation.” Philosophy & Rhetoric 6:3: 154-161.

Related Articles:

Audience Awareness - How To Boost Clarity in Communications

Medium, media.

Occasion, Exigency, Kairos - How to Decode Meaning-Making Practices

Perspective - What is the Role of Perspective in Reading & Writing?

Purpose - Aim of Discourse - Intention

Subject, topic.

Text - Composition

Writer, speaker, knowledge worker . . ., suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Joseph M. Moxley

If your text doesn’t appeal to your audience, then all is lost. Awareness of your audience (as well as purpose and context) is crucial to clarity in communications. Learn how...

Medium refer to the materials and tools Rhetors use to compose, archive, and convey messages. For 21st Century Writers, messages often have to be remediated in multiple media.

This article explores ‘perspective’ in interpretation, reasoning, and composition. It questions how a reader’s or writer’s background — personal experiences, cultural and academic influences, and their chosen viewpoint — shapes...

What is purpose? How does purpose shape the processes? When composing, how can I best identify and express my purpose?

Learn to analyze the register of a communication situation so you know when you need to code switch. Use register as a measure of audience awareness and clarity in communication....

“Text,” traditionally associated with printed materials, has evolved to encapsulate anything that conveys symbolic meaning – signifying that in the lens of modern semiotics, the world is a text. Texts...

Writers, Speakers, Knowledge Workers . . . are authors. They may also be called called actors, artists, creators, investigators, knowledge makers, researchers, rhetors, senders.

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.6: The Speech Communication Process

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 82730

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Most who study the speech communication process agree that there are several critical components present in nearly every speech. We have chosen in this text to label these components using the following terms:

- Listener(s)

Interference

As you might imagine, the speaker is the crucial first element within the speech communication process. Without a speaker, there is no process. The speaker is simply the person who is delivering, or presenting, the speech. A speaker might be someone who is training employees in your workplace. Your professor is another example of a public speaker as s/he gives a lecture. Even a stand-up comedian can be considered a public speaker. After all, each of these people is presenting an oral message to an audience in a public setting. Most speakers, however, would agree that the listener is one of the primary reasons that they speak.

The listener is just as important as the speaker; neither one is effective without the other. The listener is the person or persons who have assembled to hear the oral message. Some texts might even call several listeners an “audience. ” The listener generally forms an opinion as to the effectiveness of the speaker and the validity of the speaker’s message based on what they see and hear during the presentation. The listener’s job sometimes includes critiquing, or evaluating, the speaker’s style and message. You might be asked to critique your classmates as they speak or to complete an evaluation of a public speaker in another setting. That makes the job of the listener extremely important. Providing constructive feedback to speakers often helps the speaker improve her/his speech tremendously.

Another crucial element in the speech process is the message. The message is what the speaker is discussing or the ideas that s/he is presenting to you as s/he covers a particular topic. The important chapter concepts presented by your professor become the message during a lecture. The commands and steps you need to use, the new software at work, are the message of the trainer as s/he presents the information to your department. The message might be lengthy, such as the President’s State of the Union address, or fairly brief, as in a five-minute presentation given in class.

The channel is the means by which the message is sent or transmitted. Different channels are used to deliver the message, depending on the communication type or context. For instance, in mass communication, the channel utilized might be a television or radio broadcast. The use of a cell phone is an example of a channel that you might use to send a friend a message in interpersonal communication. However, the channel typically used within public speaking is the speaker’s voice, or more specifically, the sound waves used to carry the voice to those listening. You could watch a prerecorded speech or one accessible on YouTube, and you might now say the channel is the television or your computer. This is partially true. However, the speech would still have no value if the speaker’s voice was not present, so in reality, the channel is now a combination of the two -the speaker’s voice broadcast through an electronic source.

The context is a bit more complicated than the other elements we have discussed so far. The context is more than one specific component. For example, when you give a speech in your classroom, the classroom, or the physical location of your speech, is part of the context . That’s probably the easiest part of context to grasp.

But you should also consider that the people in your audience expect you to behave in a certain manner, depending on the physical location or the occasion of the presentation . If you gave a toast at a wedding, the audience wouldn’t be surprised if you told a funny story about the couple or used informal gestures such as a high-five or a slap on the groom’s back. That would be acceptable within the expectations of your audience, given the occasion. However, what if the reason for your speech was the presentation of a eulogy at a loved one’s funeral? Would the audience still find a high-five or humor as acceptable in that setting? Probably not. So the expectations of your audience must be factored into context as well.

The cultural rules -often unwritten and sometimes never formally communicated to us -are also a part of the context. Depending on your culture, you would probably agree that there are some “rules ” typically adhered to by those attending a funeral. In some cultures, mourners wear dark colors and are somber and quiet. In other cultures, grieving out loud or beating one’s chest to show extreme grief is traditional. Therefore, the rules from our culture -no matter what they are -play a part in the context as well.

Every speaker hopes that her/his speech is clearly understood by the audience. However, there are times when some obstacle gets in the way of the message and interferes with the listener’s ability to hear what’s being said. This is interference , or you might have heard it referred to as “noise. ” Every speaker must prepare and present with the assumption that interference is likely to be present in the speaking environment.

Interference can be mental, physical, or physiological. Mental interference occurs when the listener is not fully focused on what s/he is hearing due to her/his own thoughts. If you’ve ever caught yourself daydreaming in class during a lecture, you’re experiencing mental interference. Your own thoughts are getting in the way of the message.

A second form of interference is physical interference . This is noise in the literal sense -someone coughing behind you during a speech or the sound of a mower outside the classroom window. You may be unable to hear the speaker because of the surrounding environmental noises.

The last form of interference is physiological . This type of interference occurs when your body is responsible for the blocked signals. A deaf person, for example, has the truest form of physiological interference; s/he may have varying degrees of difficulty hearing the message. If you’ve ever been in a room that was too cold or too hot and found yourself not paying attention, you’re experiencing physiological interference. Your bodily discomfort distracts from what is happening around you.

The final component within the speech process is feedback. While some might assume that the speaker is the only one who sends a message during a speech, the reality is that the listeners in the audience are sending a message of their own, called feedback . Often this is how the speaker knows if s/he is sending an effective message. Occasionally the feedback from listeners comes in verbal form – questions from the audience or an angry response from a listener about a key point presented. However, in general, feedback during a presentation is typically non-verbal -a student nodding her/his head in agreement or a confused look from an audience member. An observant speaker will scan the audience for these forms of feedback, but keep in mind that non-verbal feedback is often more difficult to spot and to decipher. For example, is a yawn a sign of boredom, or is it simply a tired audience member?

Generally, all of the above elements are present during a speech. However, you might wonder what the process would look like if we used a diagram to illustrate it. Initially, some students think of public speaking as a linear process -the speaker sending a message to the listener -a simple, straight line. But if you’ll think about the components we’ve just covered, you begin to see that a straight line cannot adequately represent the process, when we add listener feedback into the process. The listener is sending her/his own message back to the speaker, so perhaps the process might better be represented as circular. Add in some interference and place the example in context, and you have a more complete idea of the speech process.

- Provided by : Florida State College at Jacksonville. License : CC BY: Attribution

What is a Rhetorical Situation? (Definition, Examples, Rules)

What is a rhetorical situation? How does it work? We’ve all heard of things being “rhetorical,” although do we completely understand them? Learn more about a rhetorical situation in this short guide.

What is a rhetorical situation?

A piece of writing or a speech is influenced by its creator’s background, beliefs, interests, and values. Readers interpret the text or speech by considering the circumstances out of which it arises.

The rhetorical situation offers an understanding of how readers and writers relate to each other through the written or spoken medium. It helps writers produce more effective text that meets its intended goals. It allows readers to determine the context in which the writing took place and what the text aims to do.

Let’s look at the rhetorical situation in more detail and use examples for a better grasp of the model.

How do you find the rhetorical situation?

The rhetorical situation is made up of components that impact the development and reception of the text. The components are:

2. Exigence

3. Audience

The author is the individual who creates the text. Readers of the text will consider the author’s authority or experience in the subject on which he/she has written. They will also look at the values the author holds with regard to the subject, and factors that affect the author’s perspectives on the subject.

The exigence describes the urgent need that the author wants to address through the text. The author knows why he/she wants to express certain points and how those points will impact his/her audience.

The audience refers to the people the text aims to persuade, inform, or entertain. Individuals other than the intended recipients of the text are also included in the text’s audience.

Purpose

The purpose describes the aims of the text. Does the writer aim to inform, persuade, or entertain his/her audience? Readers that engage with the text think about the writer’s motivations to create the text and the goals of that text.

Context

The context is made up of all the factors that influence the meaning of the text. The types of context are:

Physical context

The physical settings of authors affect the texts they create. For example, some writers may find they’re able to produce more effective text in bustling coffee shops while others may prefer the solitude of libraries. The specific places in which readers receive the text affect how they respond to the text.

For example, those commuting by train may read a pamphlet in a more leisurely way, which will affect how they feel about its contents. If the same pamphlet were to be handed to them while they were walking, they may engage with it differently.

Social context

The social environment of writers and readers affects how they create and receive a text. Writers and readers belonging to similar communities are more likely to communicate effectively with one another compared to writers or readers belonging to different communities.

Writers may not need to provide a detailed background on a topic when presenting to groups already familiar with the topic. Supporters of a political party will not expect a columnist supporting the rival party to provide a nuanced or unbiased account of a key poll issue.

Cultural context

A documentary set in the sixties will connect more easily with viewers who are intimately familiar with the social behaviors and speech of that era. Millennials may find it hard to understand the colloquial speech and slang of earlier generations.

Readers based in India may find it easier to follow a news article on the issue of dowry deaths than counterparts in the west, where the dowry system has never existed.

The topic is the piece of communication, whether that occurs verbally or in writing.

What is an example of a rhetorical situation?

You’re surrounded by rhetoric . It’s in YouTube videos, newspaper ads, television commercials, billboards, political speeches, literary essays, songs, and graphic novels, to name some.

The examples below highlight the components of the rhetorical situation.

1. Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby delivered the funeral eulogy for Queen Elizabeth II.

- The exigence is that it is customary to publicly reflect on a Head of State’s life and achievements

- The audience comprises the British public and people from all over the world

- The purpose is to highlight the Queen’s life of public service

- In the west, it is customary to conduct a eulogy to pay tribute to someone who has died

- The topic is the sermon the archbishop delivered at the Queen’s funeral at Westminster Abbey

2. Inaugural address by President Joseph Biden.

- The exigence is that it is customary for the elected President of the United States to deliver an inaugural address

- The audience is Americans although the inaugural address is shown on all international news channels

- The purpose is to share the President’s vision for America and promise to the American people

- The inaugural address is part of the customary ceremony to mark the commencement of a new four-year term of the President of the United States.

- The topic is the inaugural speech by the President.

Use rhetorical analysis to shape messages and gain a detailed understanding of content

Breaking down the rhetorical situation is helpful for writers, speakers, and content creators. A rhetorical analysis of content is useful to identify the improvements needed to make it more appealing to its audience and meet its goals. As a reader, rhetorical analysis is a tool to effectively understand, critique, or enjoy different types of content. Use this model today to enhance your writing and interpretation skills.

Inside this article

Fact checked: Content is rigorously reviewed by a team of qualified and experienced fact checkers. Fact checkers review articles for factual accuracy, relevance, and timeliness. Learn more.

About the author

Dalia Y.: Dalia is an English Major and linguistics expert with an additional degree in Psychology. Dalia has featured articles on Forbes, Inc, Fast Company, Grammarly, and many more. She covers English, ESL, and all things grammar on GrammarBrain.

Core lessons

- Abstract Noun

- Accusative Case

- Active Sentence

- Alliteration

- Adjective Clause

- Adjective Phrase

- Adverbial Clause

- Appositive Phrase

- Body Paragraph

- Compound Adjective

- Complex Sentence

- Compound Words

- Compound Predicate

- Common Noun

- Comparative Adjective

- Comparative and Superlative

- Compound Noun

- Compound Subject

- Compound Sentence

- Copular Verb

- Collective Noun

- Colloquialism

- Conciseness

- Conditional

- Concrete Noun

- Conjunction

- Conjugation

- Conditional Sentence

- Comma Splice

- Correlative Conjunction

- Coordinating Conjunction

- Coordinate Adjective

- Cumulative Adjective

- Dative Case

- Declarative Statement

- Direct Object Pronoun

- Direct Object

- Dangling Modifier

- Demonstrative Pronoun

- Demonstrative Adjective

- Direct Characterization

- Definite Article

- Doublespeak

- Equivocation Fallacy

- Future Perfect Progressive

- Future Simple

- Future Perfect Continuous

- Future Perfect

- First Conditional

- Gerund Phrase

- Genitive Case

- Helping Verb

- Irregular Adjective

- Irregular Verb

- Imperative Sentence

- Indefinite Article

- Intransitive Verb

- Introductory Phrase

- Indefinite Pronoun

- Indirect Characterization

- Interrogative Sentence

- Intensive Pronoun

- Inanimate Object

- Indefinite Tense

- Infinitive Phrase

- Interjection

- Intensifier

- Indicative Mood

- Juxtaposition

- Linking Verb

- Misplaced Modifier

- Nominative Case

- Noun Adjective

- Object Pronoun

- Object Complement

- Order of Adjectives

- Parallelism

- Prepositional Phrase

- Past Simple Tense

- Past Continuous Tense

- Past Perfect Tense

- Past Progressive Tense

- Present Simple Tense

- Present Perfect Tense

- Personal Pronoun

- Personification

- Persuasive Writing

- Parallel Structure

- Phrasal Verb

- Predicate Adjective

- Predicate Nominative

- Phonetic Language

- Plural Noun

- Punctuation

- Punctuation Marks

- Preposition

- Preposition of Place

- Parts of Speech

- Possessive Adjective

- Possessive Determiner

- Possessive Case

- Possessive Noun

- Proper Adjective

- Proper Noun

- Present Participle

- Quotation Marks

- Relative Pronoun

- Reflexive Pronoun

- Reciprocal Pronoun

- Subordinating Conjunction

- Simple Future Tense

- Stative Verb

- Subjunctive

- Subject Complement

- Subject of a Sentence

- Sentence Variety

- Second Conditional

- Superlative Adjective

- Slash Symbol

- Topic Sentence

- Types of Nouns

- Types of Sentences

- Uncountable Noun

- Vowels and Consonants

Popular lessons

Stay awhile. Your weekly dose of grammar and English fun.

The world's best online resource for learning English. Understand words, phrases, slang terms, and all other variations of the English language.

- Abbreviations

- Editorial Policy

Ace the Presentation

The 5 Different Types of Speech Styles

Human beings have different ways of communicating . No two people speak the same (and nor should they). In fact, if you’ve paid any attention to people’s speeches around you, you might have already noticed that they vary from speaker to speaker, according to the context. Those variations aren’t merely coincidental.

The 5 Different Types of Speech Styles (Table)

Martin Joos, a famous german linguist and professor, was the first one to organize the speeches according to their variations, having come up with five speech styles, depending on their degree of formality:

1. Frozen Style (or Fixed speech)

A speech style is characterized by the use of certain grammar and vocabulary particular to a certain field, one in which the speaker is inserted. The language in this speech style is very formal and static, making it one of the highest forms of speech styles. It’s usually done in a format where the speaker talks and the audience listens without actually being given the space to respond.

Application: It’s generally reserved for formal settings such as important ceremonies (for instance, a ceremony at the royal palace or one in which a country’s president is present), weddings, funerals, etc.

Examples: a presidential speech, an anthem, and a school creed.

2. Formal Style

This style, just like the previous one, is also characterized by a formal (agreed upon and even documented) vocabulary and choice of words, yet it’s more universal as it doesn’t necessarily require expertise in any field and it’s not as rigid as the frozen style.

The language in this speech is respectful and rejects the use of slang, contractions, ellipses and qualifying modal adverbials. Oftentimes the speaker must plan the sentences before delivering them.

Application: Although it’s often used in writing, it also applies to speaking, especially to medium to large-sized groups. It’s also the type of speech that should be used when communicating with strangers and others such as older people, elders, professionals, and figures of authority.

Examples: meetings (corporate or other formal meetings), court, class, interview, speech, or presentation.

3. Consultative Style

The third level of communication it’s a style characterized by a semi-formal vocabulary, often unplanned and reliant on the listener ’s responses and overall participation.

Application: any type of two-way communication, dialogue, whether between two people or more, where there’s no intimacy or any acquaintanceship.

Examples: group discussions, teacher-student communication, expert-apprentice, communication between work colleagues or even between employer-employee, and talking to a stranger.

4. Casual Style (or Informal Style)

As the name says, this style is characterized by its casualty, with a flexible and informal vocabulary that may include slang. It’s usually unplanned, pretty relaxed, and reliant on the fluid back and forth between those involved, without any particular order.

Application: used between people with a sense of familiarity and a relatively close relationship, whether in a group or in a one-on-one scenario.

Examples: chats with friends and family, casual phone calls, or text messages.

5. Intimate Style

This is the speech style that’s reserved for people who have a really close connection. It’s casual and relaxed and goes beyond words, as it incorporates nonverbal communication and even personal language codes, such as terms of endearment and expressions whose meaning are only understood by the participants, besides slang.

Application: used between people who share an intimate bond.

Examples: chats between best friends, boyfriend and girlfriend, siblings and other family members, whether in messages, phone calls, or personally.

Here are some of our top recommended Articles to Check next!

The 4 Methods or Types of Speech Delivery

What Makes a Great Presenter? 9 Key Qualities to Look for!

An Easy Guide to All 15 Types of Speech

4 factors that influence speech styles.

Although knowing the definition and some examples of situations in which each speech style might apply is helpful, there are four important factors that are key in speech styles. These factors help the speakers understand when it is appropriate to use one style instead of the other. They are:

1. The Setting

The setting is essentially the context in which the speech shall take place. It’s probably the most important factor to be considered when choosing which speech style to use as nothing could be more harmful than applying the wrong speech style to the wrong setting.

Although it’s a factor that’s exhausted and diverse, to make things simple for you, I’ve divided them in three main categories:

- Formal Settings:

- Casual Settings:

In these settings, people are more relaxed and less uptight than in formal settings. Since there’s a degree of familiarity between those speaking, even though people are not necessarily intimate, the speaker can apply either consultative or casual speech styles. Some examples of these settings include weddings, company or team meetings, and school classes.

- Informal Settings:

These settings are more open than casual ones as there are almost no rules to how people should interact. Everyone in it either has a deep degree of familiarity or intimacy. The styles of speeches that are used in these settings are Casual and Intimate. A few examples of these settings are family and friends gatherings, private conversations, etc.

Misreading the setting can be really embarrassing and have devastating consequences. If, for instance, you make inappropriate jokes in a work meeting or use slang words, you could be perceived as unprofessional and disrespectful, and that could cost you your job.

2. The Participants

Your audience, the people to whom your speech is directed, or the people you interact with are decisive factors when choosing your speech style.

To put it simply:

- Reserve Frozen and Formal styles for people whom you respect and are not intimate or even familiar with , either because of their position in society or because of their position in relation to you. These can be authority figures or even superiors in your workplace and strangers.

- Use Consultative and Casual speech styles with people who, even though they are familiar to you (either because you both know each other or interact often), still owe them a certain level of respect . These can be people in your workplace such as your colleagues and business partners, people in school, elders and older family members, neighbors, acquaintances and even strangers .

- Feel free to use Intimate speech styles with anyone who you share an intimate bond with . These can be your friends and your immediate and extended family members .

3. The Topic

Speech styles can give appropriate weight to serious topics, just as they can help alleviate the heaviness of certain topics. There’s no specific rule of which style to use with each topic, actually, when it comes to topics, the choice should be more intuitive and keep in mind the other factors.

For example, sometimes, when making a presentation about a serious topic at a conference, you might want to mix formal speech with a more consultative or casual speech by sliding in a joke or two in between your presentation, as this helps lighten up the mood.

4. The Purpose of The Discourse or Conversation

The purpose of your discourse is your main motivation for speaking. Just like with the topic, when it comes to choosing the speech style taking into account the purpose, the choice is mostly intuitive and keeps in mind the other factors.

You should remember never to mix a business-centered discussion, where the purpose is mostly professional and formal, with a mainly informal speech of speaking.

Speaker Styles

- Content-rich speaker:

A content-rich speaker is one whose aim is to use the speech to inform. He is factual and very objective and focused on providing all the information the audience or receptor of the message needs.

A man speaking in a presentation could be an example of this, or even a lawyer defending a case in court.

- Funny or humorous speakers:

As the name already suggests, this type of speaker uses humor as a tool to help them deliver their message. Even when delivering facts, they make jokes to lighten things up and break the tension.

Stand-up comedians are a great example of this type of speaker.

- Storyteller:

This type of speaker usually relies on the story format to deliver his message; whether it’s factual or not is not relevant as long as the main message behind the story is relevant to the receptor.

Usually, the type of speaker is not fixed in each speech style; one person can be many types of speakers depending on the speech style that they are using and keeping in mind the factors that influence the choice of the speech style.

Make sure you weigh all factors equally before choosing a speech style. You don’t want to be THAT person bringing up an intimate subject to a friend in front of a group of strangers during a business meeting where the subject has nothing to do with whatever you’re talking about.

What’s The Importance of Speech Styles In Communication

Using and knowing speech styles is the key to effective communication. Choosing the right way to communicate in different settings and with different people is what separates a good communicator from a bad communicator.

Knowing the speech styles and the rules that apply to each of them saves you from embarrassment and positions you as someone of principles and respectful, especially in formal and conservative settings.

Besides that, people tend to gravitate more towards and get influenced by good communicators; therefore, learning something new in that area and improving the quality of your speech and presentations will only benefit you.

Further Readings

Speech Styles- ELCOMBLUS

Types of Speech Styles | PDF | Sentence (Linguistics) | Cognitive Science- SCRIBD

Similar Posts

Extemporaneous Presentation: Definition and Actionable tips

There are several forms or methods of speech delivery out there and it can be impromptu (with no warning, more improvisation required), or the most common case: extemporaneous presentations. EXTEMPORANEOUS PRESENTATION DEFINITION We need to define this properly and make sure people don’t get confused here. Because from a literal sense extemporaneous and impromptu have…

Why Mastering Public Speaking Skills Will Improve Your Life – 4 Examples.

Public speaking skills are the most important skills for all those who intend to inspire, influence, lead, support and educate others. It’s perhaps the oldest and most respected skill in our history as a species, and that alone tells you how important it is to keep improving your public speaking skills. Public Speaking Skills and…

An Engaging Business presentation? Read This!

You find yourself spending endless hours in tools like Microsoft Teams or Zoom or around a table discussing strategic agendas, busy schedules from beginning to end of the day with conversations about different projects. All this, not infrequently, leaves you exhausted. However, it doesn’t have to be that way! The problem, mind you, is not…

8 Simple Ways to Work out some Self-Confidence to Speak in Public

To have self-confidence is to see the potentialities, even when difficulties or complex challenges arise in the work environment. It’s about transmitting safety and setting an example to others. Even with experience and knowledge, many professionals do not know how to have the self-confidence to speak in public when they need to present themselves before…

How to Create a Mind Map to Organize and Remember your Presentation

Clarity when communicating is one of the essential characteristics of a good oratory. Well-organized speech inspires, informs, convinces, persuades. It is, therefore, necessary to find resources to organize your content, create a logical order between the information and convey a powerful and impactful message. Mind mapping is one of the most efficient content organization techniques….

How to Become a Confident Public Speaker – 6 Tips

Ever wondered what it feels like to command a room filled with people just with the way you speak? How to Become a Confident Public Speaker ? No, it’s not a gift (in case you are wondering); rather, it takes practice and time for you to master the art of public speaking. This simply means…

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.2 Persuasive Speaking

Learning objectives.

- Explain how claims, evidence, and warrants function to create an argument.

- Identify strategies for choosing a persuasive speech topic.

- Identify strategies for adapting a persuasive speech based on an audience’s orientation to the proposition.

- Distinguish among propositions of fact, value, and policy.

- Choose an organizational pattern that is fitting for a persuasive speech topic.

We produce and receive persuasive messages daily, but we don’t often stop to think about how we make the arguments we do or the quality of the arguments that we receive. In this section, we’ll learn the components of an argument, how to choose a good persuasive speech topic, and how to adapt and organize a persuasive message.

Foundation of Persuasion

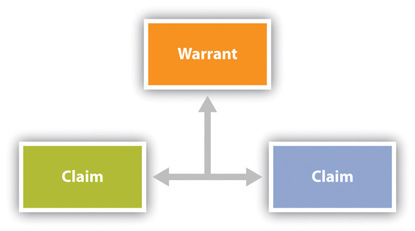

Persuasive speaking seeks to influence the beliefs, attitudes, values, or behaviors of audience members. In order to persuade, a speaker has to construct arguments that appeal to audience members. Arguments form around three components: claim, evidence, and warrant. The claim is the statement that will be supported by evidence. Your thesis statement is the overarching claim for your speech, but you will make other claims within the speech to support the larger thesis. Evidence , also called grounds, supports the claim. The main points of your persuasive speech and the supporting material you include serve as evidence. For example, a speaker may make the following claim: “There should be a national law against texting while driving.” The speaker could then support the claim by providing the following evidence: “Research from the US Department of Transportation has found that texting while driving creates a crash risk that is twenty-three times worse than driving while not distracted.” The warrant is the underlying justification that connects the claim and the evidence. One warrant for the claim and evidence cited in this example is that the US Department of Transportation is an institution that funds research conducted by credible experts. An additional and more implicit warrant is that people shouldn’t do things they know are unsafe.

Figure 11.2 Components of an Argument

The quality of your evidence often impacts the strength of your warrant, and some warrants are stronger than others. A speaker could also provide evidence to support their claim advocating for a national ban on texting and driving by saying, “I have personally seen people almost wreck while trying to text.” While this type of evidence can also be persuasive, it provides a different type and strength of warrant since it is based on personal experience. In general, the anecdotal evidence from personal experience would be given a weaker warrant than the evidence from the national research report. The same process works in our legal system when a judge evaluates the connection between a claim and evidence. If someone steals my car, I could say to the police, “I’m pretty sure Mario did it because when I said hi to him on campus the other day, he didn’t say hi back, which proves he’s mad at me.” A judge faced with that evidence is unlikely to issue a warrant for Mario’s arrest. Fingerprint evidence from the steering wheel that has been matched with a suspect is much more likely to warrant arrest.

As you put together a persuasive argument, you act as the judge. You can evaluate arguments that you come across in your research by analyzing the connection (the warrant) between the claim and the evidence. If the warrant is strong, you may want to highlight that argument in your speech. You may also be able to point out a weak warrant in an argument that goes against your position, which you could then include in your speech. Every argument starts by putting together a claim and evidence, but arguments grow to include many interrelated units.

Choosing a Persuasive Speech Topic

As with any speech, topic selection is important and is influenced by many factors. Good persuasive speech topics are current, controversial, and have important implications for society. If your topic is currently being discussed on television, in newspapers, in the lounges in your dorm, or around your family’s dinner table, then it’s a current topic. A persuasive speech aimed at getting audience members to wear seat belts in cars wouldn’t have much current relevance, given that statistics consistently show that most people wear seat belts. Giving the same speech would have been much more timely in the 1970s when there was a huge movement to increase seat-belt use.

Many topics that are current are also controversial, which is what gets them attention by the media and citizens. Current and controversial topics will be more engaging for your audience. A persuasive speech to encourage audience members to donate blood or recycle wouldn’t be very controversial, since the benefits of both practices are widely agreed on. However, arguing that the restrictions on blood donation by men who have had sexual relations with men be lifted would be controversial. I must caution here that controversial is not the same as inflammatory. An inflammatory topic is one that evokes strong reactions from an audience for the sake of provoking a reaction. Being provocative for no good reason or choosing a topic that is extremist will damage your credibility and prevent you from achieving your speech goals.

You should also choose a topic that is important to you and to society as a whole. As we have already discussed in this book, our voices are powerful, as it is through communication that we participate and make change in society. Therefore we should take seriously opportunities to use our voices to speak publicly. Choosing a speech topic that has implications for society is probably a better application of your public speaking skills than choosing to persuade the audience that Lebron James is the best basketball player in the world or that Superman is a better hero than Spiderman. Although those topics may be very important to you, they don’t carry the same social weight as many other topics you could choose to discuss. Remember that speakers have ethical obligations to the audience and should take the opportunity to speak seriously.

You will also want to choose a topic that connects to your own interests and passions. If you are an education major, it might make more sense to do a persuasive speech about funding for public education than the death penalty. If there are hot-button issues for you that make you get fired up and veins bulge out in your neck, then it may be a good idea to avoid those when speaking in an academic or professional context.

Choose a persuasive speech topic that you’re passionate about but still able to approach and deliver in an ethical manner.

Michael Vadon – Nigel Farage – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Choosing such topics may interfere with your ability to deliver a speech in a competent and ethical manner. You want to care about your topic, but you also want to be able to approach it in a way that’s going to make people want to listen to you. Most people tune out speakers they perceive to be too ideologically entrenched and write them off as extremists or zealots.

You also want to ensure that your topic is actually persuasive. Draft your thesis statement as an “I believe” statement so your stance on an issue is clear. Also, think of your main points as reasons to support your thesis. Students end up with speeches that aren’t very persuasive in nature if they don’t think of their main points as reasons. Identifying arguments that counter your thesis is also a good exercise to help ensure your topic is persuasive. If you can clearly and easily identify a competing thesis statement and supporting reasons, then your topic and approach are arguable.

Review of Tips for Choosing a Persuasive Speech Topic

- Not current. People should use seat belts.

- Current. People should not text while driving.

- Not controversial. People should recycle.

- Controversial. Recycling should be mandatory by law.

- Not as impactful. Superman is the best superhero.

- Impactful. Colleges and universities should adopt zero-tolerance bullying policies.

- Unclear thesis. Homeschooling is common in the United States.

- Clear, argumentative thesis with stance. Homeschooling does not provide the same benefits of traditional education and should be strictly monitored and limited.

Adapting Persuasive Messages

Competent speakers should consider their audience throughout the speech-making process. Given that persuasive messages seek to directly influence the audience in some way, audience adaptation becomes even more important. If possible, poll your audience to find out their orientation toward your thesis. I read my students’ thesis statements aloud and have the class indicate whether they agree with, disagree with, or are neutral in regards to the proposition. It is unlikely that you will have a homogenous audience, meaning that there will probably be some who agree, some who disagree, and some who are neutral. So you may employ all of the following strategies, in varying degrees, in your persuasive speech.

When you have audience members who already agree with your proposition, you should focus on intensifying their agreement. You can also assume that they have foundational background knowledge of the topic, which means you can take the time to inform them about lesser-known aspects of a topic or cause to further reinforce their agreement. Rather than move these audience members from disagreement to agreement, you can focus on moving them from agreement to action. Remember, calls to action should be as specific as possible to help you capitalize on audience members’ motivation in the moment so they are more likely to follow through on the action.

There are two main reasons audience members may be neutral in regards to your topic: (1) they are uninformed about the topic or (2) they do not think the topic affects them. In this case, you should focus on instilling a concern for the topic. Uninformed audiences may need background information before they can decide if they agree or disagree with your proposition. If the issue is familiar but audience members are neutral because they don’t see how the topic affects them, focus on getting the audience’s attention and demonstrating relevance. Remember that concrete and proxemic supporting materials will help an audience find relevance in a topic. Students who pick narrow or unfamiliar topics will have to work harder to persuade their audience, but neutral audiences often provide the most chance of achieving your speech goal since even a small change may move them into agreement.