Biography Online

Indira Gandhi Biography

In 1999, she was voted the greatest woman of the past thousand years in a poll carried by BBC News, ahead of other notable women such as Queen Elizabeth I of England, Marie Curie and Mother Teresa.

Gandhi and Indira

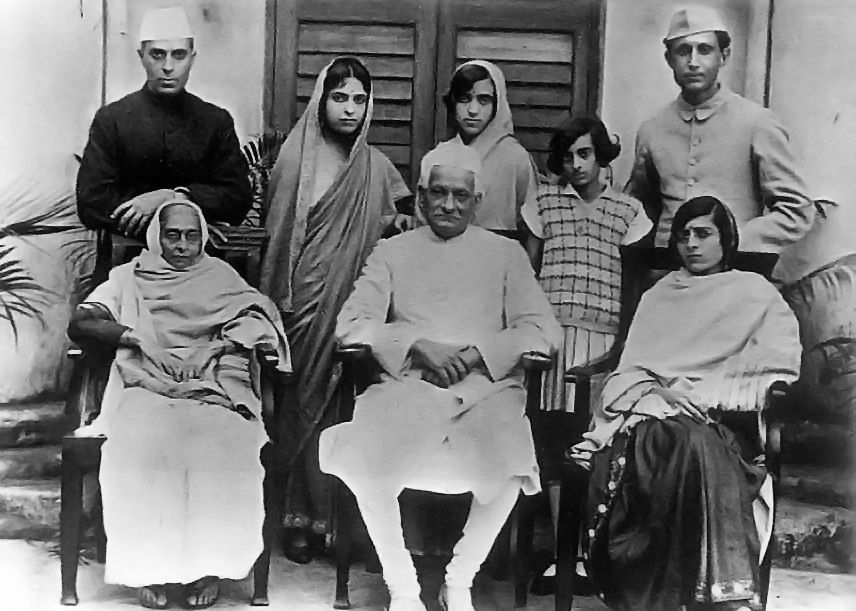

Born in the politically influential Nehru dynasty, she grew up in an intensely political atmosphere. Despite the same last name, she was no relation to the statesman Mohandas Gandhi. Her grandfather, Motilal Nehru, was a prominent Indian nationalist leader. Her father, Jawaharlal Nehru , was a pivotal figure in the Indian independence movement and the first Prime Minister of Independent India.

She was brought up in an environment with great exposure to the political figures of the day and was particularly influenced by her father. She stated of her father:

“My father was a statesman, I’m a political woman. My father was a saint. I’m not.”

In one early photograph (above), she was sitting on the bed of Mohandas Gandhi as he recovered from one of his fasts. From an early age, she took as a political role model, Joan of Arc and expressed the hope that one day she would lead her people to freedom like the French saint.

In 1937, she passed the Oxford entrance exam and studied at Somerville College, Oxford. At university, she was often subject to ill health and returned to India without completing her degree – though later she was conferred an honorary degree by Oxford University.

On returning to India from Oxford in 1941, Indira became involved in the Indian Independence movement. Between 1947 and 1965, she served in her father’s (J. Nehru) government. Although she was unofficially acting as a personal assistant, she wielded considerable power within the government. After her father’s death in 1964, she was appointed as Minister of Information and Broadcasting in Lal Bahadur Shastri’s cabinet. Shortly after, Shastri died unexpectedly and, with the help of Congress Party President, K. Kamaraj, Indira Gandhi was chosen to be the new Prime Minister of India.

Gandhi attracted significant electoral popularity helped by her personality and populist economic measures. She introduced more left-wing economic policies and sought to promote agricultural productivity. In 1971, she led India to a decisive victory in a war with Pakistan in East Pakistan. This led to the creation of Bangladesh. In 1974, India completed their own nuclear bomb.

However, in the early 1970s, partly due to rising oil prices the Indian economy suffered from high inflation, falling living standards, and combined with protests over corruption, there was great instability that led her to impose a state of emergency in 1975. In the state of emergency, political opponents were imprisoned, constitutional rights removed, and the press placed under strict censorship. This gave her a reputation for being authoritarian, willing to ignore democratic principles.

Her son Sanjay Gandhi was also increasingly unpopular as he wielded substantial powers, such as slum clearance and enforced sterilisation to deal with India’s growing population. In 1977, against a backdrop of economic difficulties and growing disillusionment, Indira Gandhi lost the election and temporarily dropped out of politics.

However, she was returned to office in 1980. But, in this period, she became increasingly involved in an escalating conflict with Sikh separatists in Punjab. She was later assassinated by her own Sikh bodyguards in 1984 for her role in storming the sacred Golden Temple. Shortly before her assassination, she spoke on the frequent threats to her life.

“I do not care whether I live or die. I have lived a long life and I am proud that I spend the whole of my life in the service of my people. I am only proud of this and nothing else. I shall continue to serve until my last breath and when I die, I can say, that every drop of my blood will invigorate India and strengthen it.” S elected Speeches of Indira Gandhi : January 1, 1982-October 30, 1984.

Indira married Feroze Gandhi in 1942. The couple had two sons Rajiv (b. 1944) and Sanjay (b. 1946). Her husband died of a heart attack in 1960 and Sanjay – who was destined to be her political heir – perished in a plane crash in 1980. Devastated by the loss of Sanjay, Indira persuaded a reluctant Rajiv to quit his job and enter into politics. After his mother’s assassination in 1984, he served as Indian Prime Minister from 1984-89. (Rajiv was assassinated by Tamil Tigers in 1991)

Indira Gandhi views on women

Indira Gandhi was a rare example of a woman rising to the most powerful position in Indian society. She did not consider herself a feminist but was concerned with issues relating to women and she saw her own success as proof that talented women could rise to the top. During her administration, equal pay for men and women was enshrined in the constitution. In a speech on “True Liberation Of Women”, March 26, 1980, she said:

“To be liberated, a woman must feel free to be herself, not in rivalry to man but in the context of her own capacity and her personality.”

She also sought to mobilise Indian woman for the cause of Indian Independence.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography Indira Gandhi ”, Oxford, UK. www.biographyonline.net , 11th March 2009. Last updated 17th February 2017.

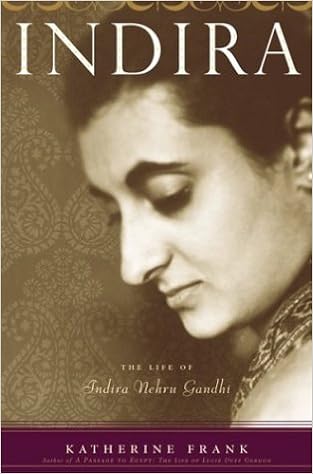

The Life of Indira Nehru Gandhi

The Life of Indira Nehru Gandhi at Amazon

Related pages

- Indian politicians

Indira Gandhi Biography

- Figures & Events

- Southeast Asia

- Middle East

- Central Asia

- Asian Wars and Battles

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- Ph.D., History, Boston University

- J.D., University of Washington School of Law

- B.A., History, Western Washington University

Indira Gandhi, prime minister of India in the early 1980s, feared the growing power of the charismatic Sikh preacher and militant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. Throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, sectarian tension and strife had been growing between Sikhs and Hindus in northern India.

Tensions in the region had grown so high that by June of 1984, Indira Gandhi decided to take action. She made a fatal choice - to send in the Indian Army against the Sikh militants in the Golden Temple.

Indira Gandhi's Early Life

Indira Gandhi was born on November 19, 1917, in Allahabad (in modern-day Uttar Pradesh), British India . Her father was Jawaharlal Nehru , who would go on to become the first prime minister of India following its independence from Britain; her mother, Kamala Nehru, was just 18 years old when the baby arrived. The child was named Indira Priyadarshini Nehru.

Indira grew up as an only child. A baby brother born in November of 1924 died after just two days. The Nehru family was very active in the anti-imperial politics of the time; Indira's father was a leader of the nationalist movement and a close associate of Mohandas Gandhi and Muhammad Ali Jinnah .

Sojourn in Europe

In March 1930, Kamala and Indira were marching in protest outside of the Ewing Christian College. Indira's mother suffered from heat-stroke, so a young student named Feroz Gandhi rushed to her aid. He would become a close friend of Kamala's, escorting and attending her during her treatment for tuberculosis, first in India and later in Switzerland. Indira also spent time in Switzerland, where her mother died of TB in February of 1936.

Indira went to Britain in 1937, where she enrolled at Somerville College, Oxford, but never completed her degree. While there, she began to spend more time with Feroz Gandhi, then a London School of Economics student. The two married in 1942, over the objections of Jawaharlal Nehru, who disliked his son-in-law. (Feroz Gandhi was no relation to Mohandas Gandhi.)

Nehru eventually had to accept the marriage. Feroz and Indira Gandhi had two sons, Rajiv, born in 1944, and Sanjay, born in 1946.

Early Political Career

During the early 1950s, Indira served as an unofficial personal assistant to her father, then the prime minister. In 1955, she became a member of the Congress Party's working committee; within four years, she would be president of that body.

Feroz Gandhi had a heart attack in 1958, while Indira and Nehru were in Bhutan on an official state visit. Indira returned home to take care of him. Feroz died in Delhi in 1960 after suffering a second heart attack.

Indira's father also died in 1964 and was succeeded as prime minister by Lal Bahadur Shastri. Shastri appointed Indira Gandhi his minister of information and broadcasting; in addition, she was a member of the upper house of parliament, the Rajya Sabha .

In 1966, Prime Minister Shastri died unexpectedly. Indira Gandhi was named the new Prime Minister as a compromise candidate. Politicians on both sides of a deepening divide within the Congress Party hoped to be able to control her. They had completely underestimated Nehru's daughter.

Prime Minister Gandhi

By 1966, the Congress Party was in trouble. It was dividing into two separate factions; Indira Gandhi led the left-wing socialist faction. The 1967 election cycle was grim for the party - it lost almost 60 seats in the lower house of parliament, the Lok Sabha . Indira was able to keep the Prime Minister seat through a coalition with the Indian Communist and Socialist parties. In 1969, the Indian National Congress Party split in half for good.

As prime minister, Indira made some popular moves. She authorized the development of a nuclear weapons program in response to China's successful test at Lop Nur in 1967. (India would test its own bomb in 1974.) In order to counterbalance Pakistan's friendship with the United States, and also perhaps due to mutual personal antipathy with US President Richard Nixon , she forged a closer relationship with the Soviet Union.

In keeping with her socialist principles, Indira abolished the maharajas of India's various states, doing away with their privileges as well as their titles. She also nationalized the banks in July of 1969, as well as mines and oil companies. Under her stewardship, traditionally famine-prone India became a Green Revolution success story, actually exporting a surplus of wheat, rice and other crops by the early 1970s.

In 1971, in response to a flood of refugees from East Pakistan, Indira began a war against Pakistan. The East Pakistani/Indian forces won the war, resulting in the formation of the nation of Bangladesh from what had been East Pakistan.

Re-election, Trial, and the State of Emergency

In 1972, Indira Gandhi's party swept to victory in national parliamentary elections based on the defeat of Pakistan and the slogan of Garibi Hatao , or "Eradicate Poverty." Her opponent, Raj Narain of the Socialist Party, charged her with corruption and electoral malpractice. In June of 1975, the High Court in Allahabad ruled for Narain; Indira should have been stripped of her seat in Parliament and barred from elected office for six years.

However, Indira Gandhi refused to step down from the prime ministership, despite wide-spread unrest following the verdict. Instead, she had the president declare a state of emergency in India.

During the state of emergency, Indira initiated a series of authoritarian changes. She purged the national and state governments of her political opponents, arresting and jailing political activists. To control population growth , she instituted a policy of forced sterilization, under which impoverished men were subjected to involuntary vasectomies (often under appallingly unsanitary conditions). Indira's younger son Sanjay led a move to clear the slums around Delhi; hundreds of people were killed and thousands left homeless when their homes were destroyed.

Downfall and Arrests

In a key miscalculation, Indira Gandhi called new elections in March 1977. She may have begun to believe her own propaganda, convincing herself that the people of India loved her and approved of her actions during the years-long state of emergency. Her party was trounced at the polls by the Janata Party, which cast the election as a choice between democracy or dictatorship, and Indira left office.

In October of 1977, Indira Gandhi was jailed briefly for official corruption. She would be arrested again in December of 1978 on the same charges. However, the Janata Party was struggling. A cobbled-together coalition of four previous opposition parties, it could not agree on a course for the country and accomplished very little.

Indira Emerges Once More

By 1980, the people of India had had enough of the ineffectual Janata Party. They reelected Indira Gandhi's Congress Party under the slogan of "stability." Indira took power again for her fourth term as prime minister. However, her triumph was dampened by the death of her son Sanjay, the heir apparent, in a plane crash in June of that year.

By 1982, rumblings of discontent and even outright secessionism were breaking out all over India. In Andhra Pradesh, on the central east coast, the Telangana region (comprising the inland 40%) wanted to break away from the rest of the state. Trouble also flared in the ever-volatile Jammu and Kashmir region in the north. The most serious threat, though, came from Sikh secessionists in Punjab, led by Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale.

Operation Bluestar at the Golden Temple

In 1983, the Sikh leader Bhindranwale and his armed followers occupied and fortified the second-most holy building in the sacred Golden Temple complex (also called the Harmandir Sahib or Darbar Sahib ) in Amritsar, the Indian Punjab. From their position in the Akhal Takt building, Bhindranwale and his followers called for armed resistance to Hindu domination. They were upset that their homeland, Punjab, had been divided between India and Pakistan in the 1947 Partition of India .

To make matters worse, the Indian Punjab had been lopped in half once more in 1966 to form the Haryana state, which was dominated by Hindi-speakers. The Punjabis lost their first capital at Lahore to Pakistan in 1947; the newly-built capital at Chandigarh ended up in Haryana two decades later, and the government in Delhi decreed that Haryana and Punjab would simply have to share the city. To right these wrongs, some of Bhindranwale's followers called for an entirely new, separate Sikh nation, to be called Khalistan.

During this period, Sikh extremists were waging a campaign of terror against Hindus and moderate Sikhs in Punjab. Bhindranwale and his following of heavily armed militants holed up in the Akhal Takt, the second-most holy building after the Golden Temple itself. The leader himself was not necessarily calling for the creation of Khalistan; rather he demanded the implementation of the Anandpur Resolution, which called for the unification and purification of the Sikh community within Punjab.

Indira Gandhi decided to send the Indian Army on a frontal assault of the building to capture or kill Bhindranwale. She ordered the attack at the beginning of June 1984, even though June 3rd was the most important Sikh holiday (honoring the martyrdom of the Golden Temple's founder), and the complex was full of innocent pilgrims. Interestingly, due to the heavy Sikh presence in the Indian Army, the commander of the attack force, Major General Kuldip Singh Brar, and many of the troops were also Sikhs.

In preparation for the attack, all electricity and lines of communication to Punjab were cut off. On June 3, the army surrounded the temple complex with military vehicles and tanks. In the early morning hours of June 5, they launched the attack. According to official Indian government numbers, 492 civilians were killed, including women and children, along with 83 Indian army personnel. Other estimates from hospital workers and eyewitnesses state that more than 2,000 civilians died in the bloodbath.

Among those killed were Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and the other militants. To the further outrage of Sikhs worldwide, the Akhal Takt was badly damaged by shells and gunfire.

Aftermath and Assassination

In the aftermath of Operation Bluestar, a number of Sikh soldiers resigned from the Indian Army. In some areas, there were actual battles between those resigning and those still loyal to the army.

On October 31, 1984, Indira Gandhi walked out to the garden behind her official residence for an interview with a British journalist. As she passed two of her Sikh bodyguards, they drew their service weapons and opened fire. Beant Singh shot her three times with a pistol, while Satwant Singh fired thirty times with a self-loading rifle. Both men then calmly dropped their weapons and surrendered.

Indira Gandhi died that afternoon after undergoing surgery. Beant Singh was shot dead while under arrest; Satwant Singh and alleged conspirator Kehar Singh were later hanged.

When news of the Prime Minister's death was broadcast, mobs of Hindus across northern India went on a rampage. In the Anti-Sikh Riots, which lasted for four days, anywhere from 3,000 to 20,000 Sikhs were murdered, many of them burned alive. The violence was particularly bad in Haryana state. Because the Indian government was slow to respond to the pogrom, support for the Sikh separatist Khalistan movement increased markedly in the months following the massacre.

Indira Gandhi's Legacy

India's Iron Lady left behind a complicated legacy. She was succeeded in the office of Prime Minister by her surviving son, Rajiv Gandhi. This dynastic succession is one of the negative aspects of her legacy - to this day, the Congress Party is so thoroughly identified with the Nehru/Gandhi family that it cannot avoid charges of nepotism. Indira Gandhi also instilled authoritarianism into India's political processes, warping the democracy to suit her need for power.

On the other hand, Indira clearly loved her country and did leave it in a stronger position relative to neighboring countries. She sought to improve the lives of India's poorest and supported industrialization and technological development. On balance, however, Indira Gandhi seems to have done more harm than good during her two stints as the prime minister of India.

- Jawaharlal Nehru, India's First Prime Minister

- Timeline of Indian History

- What Was the Partition of India?

- The British Raj in India

- Female Heads of State in Asia

- Benazir Bhutto of Pakistan

- Biography of Mohandas Gandhi, Indian Independence Leader

- Bangladesh: Facts and History

- Gandhi's Historic March to the Sea in 1930

- Pakistan | Facts and History

- Kashmir History and Background

- Sarojini Naidu

- 20 Facts About the Life of Mahatma Gandhi

- The Sri Lankan Civil War

- The Indian Revolt of 1857

- Nobel Peace Prize Laureates From Asia

7 Facts About Indira Gandhi

Her life involved politics from a young age

Almost from the moment she was born in 1917, Indira Nehru's life was steeped in politics. Her father, Jawaharlal Nehru , was a leader in the fight for India's independence from British rule, so it was natural for Indira to become a supporter of this struggle.

One tactic of India's nationalist movement was to reject foreign — particularly British — products. At a young age, Indira witnessed a bonfire of foreign goods. Later, the 5-year-old chose to burn her own beloved doll because the toy had been made in England.

When she was 12, Indira played an even bigger role in India's struggle for self-determination by leading children in the Vanar Sena (the name means Monkey Brigade; it was inspired by the monkey army that aided Lord Rama in the epic Ramayana). The group grew to include 60,000 young revolutionaries who addressed envelopes, made flags, conveyed messages and put up notices about demonstrations. It was a risky undertaking, but Indira was happy to be participating in the independence movement.

Her marriage wasn't widely supported

Indira's father was a close associate of Mahatma Gandhi . However, the fact that Indira ended up with the same last name as the iconic Indian leader wasn't due to a connection with the Mahatma; instead, Indira became Indira Gandhi following her marriage to Feroze Gandhi (who wasn't related to the Mahatma). And despite the fact that Indira and Feroze were in love, theirs was a wedding that few people in India supported.

Feroze, a fellow participant in the struggle for independence, was Parsi, while Indira was Hindu, and at the time mixed marriages were unusual. It was also out-of-the-norm not to have an arranged marriage. In fact, there was such a public outcry against the match that Mahatma Gandhi had to offer a public statement of support, which included the request: "I invite the writers of abusive letters to shed your wrath and bless the forthcoming marriage."

Indira and Feroze wed in 1942. Unfortunately, though the pair had two sons together, the marriage was not a great success. Feroze had extramarital liaisons, while much of Indira's time was spent with her father after he became India's prime minister in 1947. The marriage ended with Feroze's death in 1960.

A refugee crisis put pressure on her

In 1971, Indira faced a crisis when troops from West Pakistan went into Bengali East Pakistan to crush its independence movement. She spoke out against the horrific violence on March 31, but harsh treatment continued and millions of refugees began to stream into neighboring India.

Taking care of these refugees stretched India's resources; tensions also mounted because India offered support to independence fighters. Making the situation even more complicated were geopolitical considerations — President Richard Nixon wanted the United States to stand by Pakistan and China was arming Pakistan, while India had signed a "treaty of peace, friendship and cooperation" with the Soviet Union. The situation didn't improve when Indira visited the United States in November — Oval Office recordings from the time reveal that Nixon told Henry Kissinger the prime minister was an "old witch."

War began when Pakistan's air force bombed Indian bases on December 3; Indira recognized the independence of Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan) on December 6. On December 9, Nixon directed a U.S. fleet to head for Indian waters — but then Pakistan surrendered on December 16.

The war's conclusion was a triumph for India and Indira (and, of course, for Bangladesh). After the conflict had ended, Indira declared in an interview, "I am not a person to be pressured — by anybody or any nation."

Millions were sterilized when she declared a state of emergency

In June 1975, Indira was found guilty of electoral malpractice. When rivals began advocating for her removal as prime minister, she opted to declare a state of emergency. Emergency rule would be a dark moment for India's democracy, with opponents imprisoned and press freedoms limited. Perhaps most shockingly, millions of people were sterilized — some against their will — during this period.

At the time, population control was seen as necessary in order for India to prosper (Indira's favored son and confidant, Sanjay, became particularly focused on reducing the birth rate). During the Emergency, the government directed its energies toward sterilization, with a focus on the simpler procedure of vasectomies. To encourage men to undergo the operation, incentives such as cooking oil and cash were offered.

Then government workers began to be required to meet sterilization quotas to get paid. Reports came out that vasectomies had been performed on boys, and that men were being arrested, then sent to be sterilized. Some began sleeping in fields so as to avoid sterilization teams. According to a 1977 article in TIME magazine, between April 1976 and January 1977, 7.8 million were sterilized (the initial target had been 4.3 million).

At the beginning of 1977, Indira called for elections, ending her Emergency rule. She'd expected to win this vote, but the fear and worries brought on by the sterilization policy contributed to her defeat at the polls, and she was kicked out of office.

She clashed with her daughter-in-law

In 1982, a disagreement between Indira and daughter-in-law Maneka led to a showdown. Practically from the moment Maneka wed Sanjay and entered Indira's household, the younger woman didn't fit in. After Sanjay died in 1980 (he was killed in a plane crash), tensions rose further. Things came to a head when Maneka defied Indira to attend a rally of Sanjay's former political allies (which didn't help the political interests of Rajiv, Sanjay's brother).

As punishment, Indira ordered Maneka to leave her house. In return, Maneka made sure the press captured her bags being unceremoniously left outside. Maneka also publicly decried her treatment, stating, "I have not done anything to merit being thrown out. I don't understand why I am being attacked and held personally responsible. I am more loyal to my mother-in-law than even to my mother."

Though the prime minister got Maneka to move out, she paid a price as well: Maneka took her son, Varun, with her, and being separated from a beloved grandson was a blow for Indira.

She was close with Margaret Thatcher

As a female leader in the 20th century, Indira Gandhi was a member of a very small club. Yet she had one friend who could understand what her life was like: the Iron Lady herself, Britain's Margaret Thatcher .

Indira and Thatcher first met in 1976. They got on well, despite the fact that Indira was engaged in her undemocratic Emergency rule at the time. And when Indira was temporarily out of power after her electoral defeat in 1977, Thatcher didn't abandon her. The two continued to have a good rapport after Indira returned to power in 1980.

When Thatcher came close to being killed by an IRA bomb in October 1984, Indira was sympathetic. Following Indira's own assassination a few weeks later, Thatcher ignored death threats to attend the funeral. The note of condolence that she sent to Rajiv stated: "I cannot describe to you my feelings at the news of the loss of your mother, except to say that it was like losing a member of my own family. Our many talks together had a closeness and mutual understanding which will always remain with me. She was not just a great statesman but a warm and caring person."

Her son succeeded her after her death

One significant factor that buoyed Indira's political career was her heritage. As the daughter of India's first prime minister, the Congress Party was happy to put her in a position of leadership, then later selected her to become prime minister.

After Indira's 1984 assassination, her son Rajiv succeeded her as prime minister. In 1991, he was also assassinated, but the Nehru-Gandhi clan still wasn't done with politics: though Rajiv's widow, Sonia, initially declined the Congress Party's request to step into a leadership role, she eventually became its president. By the 2014 election, Rajiv and Sonia's son Rahul had joined the Congress Party as well; however, the party went on to experience a big loss at the polls. At a press conference, Rahul admitted, "The Congress has done pretty badly, there is a lot for us to think about. As vice president of the party I hold myself responsible."

Yet not all Gandhis fared poorly in the 2014 election — as members of the victorious Bharatiya Janata Party, Maneka Gandhi and her son Varun are now in power, with Maneka serving as minister of women and child development (though considering her acrimonious relationship with Maneka, this development likely wouldn't thrill Indira). And despite their poor showing in 2014, the Congress Party refused to accept Sonia and Rahul's resignations. It seems that various members of Indira's family will continue to play a role in Indian politics for the foreseeable future.

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Women’s History

Simone Biles

Kamala Harris

Deb Haaland

14 Hispanic Women Who Have Made History

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

Ava DuVernay

Betty Friedan

Madeleine Albright

Greta Gerwig

Jane Goodall

Hillary Clinton

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- Indira Gandhi Biography

Who was Indira Gandhi?

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi, a notable woman in the history of The Indian politics, the Iron Lady, was the first woman prime minister of India. She was an icon of the Indian National Congress. Indira Gandhi father, Jawaharlal Nehru, was the very first Prime Minister of India to support Mahatma Gandhi in the fight for independence. Indira Gandhi was the second prime minister to serve for a longer period of time, first from 1966 to 1977 and second from 1980 to her death in 1984. From 1947 to 1964, she continued as Chief of Staff in the Jawaharlal Nehru administration, which was highly integrated. In 1959, she was elected president of the Congress.

Indira Gandhi, as Prime Minister, was seen as ferocious, weak and extraordinary with the centralization of power. From 1975 to 1977, she placed an emergency in the country to suppress the political opposition. India gained popularity in South Asia with major economic, military and political changes under her leadership. Indira Gandhi was elected by the India Today Magazine in 2001 as the world's greatest Prime Minister. In 1999, BBC called her the "Woman of the Millennium."

Birth and Education

Born on November 19, 1917, Indira Gandhi family was an illustrious family. She was the daughter of Jawaharlal Nehru. Indira Gandhi Education was at prime institutions like Ecole Nouvelle, Bex, Ecole Internationale, Geneva, Pupils’ Own School, Poona and Bombay, Badminton School, Bristol, Vishwa Bharati, Shantiniketan and Somerville College, Oxford. A number of universities worldwide awarded her honorary doctoral degree. She also received a Citation of Distinction from Columbia University with an outstanding academic record. Smt. Indira Gandhi was deeply involved in the fight for independence. In her childhood, she established the 'Bal Charkha Sangh' and also in 1930 the 'Vanar Sena' of kids to assist the Congress Party in the Non-Cooperation Movement. She was arrested in September 1942 and served in the riot-affected areas of Delhi with Gandhi's supervision in 1947.

Marriage and Political Journey

Indira Gandhi Husband was Feroze Gandhi. On 26 March 1942, she married him and had two children. In 1955, she became a member of the working committee for the Congress and the Party's central election. She was appointed to the Central Parliamentary Congress Board in 1958. She was Chairman, National Council Integration for A.I.C.C. and President, All India Youth Congress, Women's Department, 1956. In 1959 she was President of the Indian National Congress, serving until 1960 and from January 1978 again.

She was Information and Broadcasting Minister (1964- 1966). From January 1966 through March 1977, she held the highest office as Indian Prime Minister. At the same time, from September 1967 until March 1977, she was Minister of Atomic Energy. From 5 September 1967 to 14 February 1969, she was additionally appointed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. From June 1970 to November 1973, Gandhi headed the Ministry of Home Affairs and from June 1972 to March 1977 was Minister of Space. She was President of the Planning Commission from January 1980. From 14 January 1980, she again presided over the Prime Minister's Office.

Organisations and Institutions

Indira Gandhi has been affiliated with a number of organizations and institutions, such as Kamala Nehru Memorial Hospital, Gandhi Smarak Nidhi and Kasturba Gandhi Memorial Trust. She was the Swaraj Bhavan Trust Chairman. In 1955, Bal Sahyog, Bal Bhavan Board and the Children's National Museum were also affiliated with her. In Allahabad, she established Kamala Nehru Vidyalaya. During 1966-77, she was also linked to several major institutions including the University of Jawaharlal Nehru and the North-Eastern University. She was also a member of the Delhi University Court, the Indian Delegation to UNESCO (1960-64), a member of the Executive Board of UNESCO from 1960-64 and a member of the National Defense Council from 1962. She has also been involved with the Sangeet Natak Academy, the National Integration Council, the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute, the Dakshina Bharat Hindi Prachar Sabha, the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library Society and the Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund.

In August 1964, Indira Gandhi also became a Rajya Sabha member and served until February 1967. During the fourth, fifth and sixth sessions, she was a Lok Sabha member. In January 1980, she was elected to the Seventh Lok Sabha, from Rae Bareli (U.P.) and Medak (Andhra Pradesh). She preferred the Medak seat to be held and gave up the Rae Bareli seat. In 1967-77 and again in January 1980, she was appointed as the leader of the Congress Parliamentary Party.

Achievements

To her credit, she had many achievements. In 1972, she was the receiver of Bharat Ratna, Mexican Academy Award for Liberation of Bangladesh (1972), FAO's 2nd Annual Medal (1973) and Nagari Pracharini Sabha's Sahitya Vachaspati (Hindi) in 1976. In 1953, Gandhi was also awarded the Mothers' Award, U.S.A., the Italian Islbella d'Este Award for excellent diplomatic work, and the Howland Memorial Prize from Yale University. According to a poll by the French Institute of Public Opinion, she was the woman most respected by the French for two years, in 1967 and 1968. She was the world's most respected female in 1971, according to a special Gallup Poll Survey in the U.S.A. She was awarded Diploma of Honour by the Argentine Society in the year 1971 for the Protection of Animals.

Indira Gandhi Death

Indira Gandhi, the Iron Lady of India, died in 1984 on October 31. She was killed by two of her bodyguards. Her words, spoken at a public rally in Bhubaneswar just the previous day, had become prophetic. Indira Gandhi was reading from a speech prepared by her information advisor, HY Sharada Prasad. For a few moments, by removing the script written, Indira Gandhi talked about the chances of a tragic end to her life. She said, “I'm here today, and maybe tomorrow I won't be here. Nobody knows how many attempts to shoot me have been made. If I live or die, I do not care. I've lived a long life, and I'm proud that I've spent my entire life helping my country.”

Indira Gandhi History is perhaps one of the most popular Indian leaders in the world. She was India's first and only female Prime Minister, in addition to being the daughter of one of the founding fathers of the country, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. Internationally, her strong presence helped to develop India's place as an emerging global superpower. At the time of her tenure, she was dubbed 'The Iron Lady of India' by many. She was praised as a 'goddess' by many political leaders after leading India to victory in the 1971 Indo-Pakistan War, with Atal Bihari Vajpayee naming her 'Goddess Durga' in particular. Her tenure was not short of controversy, for all her successes.

Her declaration of a national emergency, which resulted in a ban on the press and media, received criticism from many; from the governments of the people and the opposition. While aimed at removing Sikh extremists from a shrine, Operation Blue Star was a highly contentious problem and was eventually seen as the cause of her death in 1984. Nonetheless, as one of India's greatest Prime Ministers, she leaves behind a legacy. After her assassination, Indira Gandhi was succeeded by her mother, Rajiv Gandhi.

FAQs on Indira Gandhi Biography

1. What is Indira Gandhi Date of birth?

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi, a notable woman in the history of Indian politics. Born on November 19, 1917, Indira Gandhi family was an illustrious family. She was the daughter of Jawaharlal Nehru.

2. Who was the first Woman Prime Minister of India?

The first women Prime Minister of India to serve three consecutive terms was Indira Gandhi. She was succeeded as PM by Lal Bahadur Shastri. Indira Gandhi was Jawaharlal Nehru's only child.

3. Who is Indira Gandhi?

The only woman who served as India's Prime Minister was Indira Gandhi, the daughter of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. Born into a political family, she was, after her father, the second longest-serving prime minister in India.

- Bihar Board

2024 Election Results

Cfa institute, srm university.

- UP Election Result

- Bihar Election Result

- AP Election Result

- Delhi Election Result

- Rajasthan Election Result

- Maharashtra Election Result

- MP Election Result

- Haryana Election Result

- West Bengal Election Result

- Shiv Khera Special

- Education News

- Web Stories

- Current Affairs

- School & Boards

- College Admission

- Govt Jobs Alert & Prep

- GK & Aptitude

- general knowledge

Indira Gandhi Biography: Birth, Family, Education, Political Career, Posthumus Awards, Legacy and more

Indira gandhi biography: indira gandhi was the central figure of indian national congress and is the first and only women prime minister of india to date. she was the daughter of the first prime minister of india, jawaharlal nehru. on this day, 45 years ago, she imposed emergency in india. .

On this day, 45 years ago, Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India declared Emergency in India in 1975. The proclamation was signed by the then President of India, Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed. Indira Gandhi was the central figure of Indian National Congress and is the first and only women Prime Minister of India to date.

Indira Gandhi: Birth, Family, Education

Indira Gandhi was born on 19 November 1917, to Jawaharlal Nehru and Kamala Nehru in Allahabad, India. Her father was the leading freedom fighter and was the first Prime Minister of Independent India. After her younger brother died at an early age, Indira was raised by her mother at Anand Bhawan. When Indira was young, Kamala Nehru died an early death after suffering from tuberculosis.

Indira was taught by tutors at home and she didn't attend school regularly. She attended Modern School in Delhi, St Cecilia's and St Mary's Christian convent schools in Allahabad, the International School of Geneva, the Ecole Nouvelle in Bex, the Pupils' Own School in Poona and Bombay, Vishwa Bharati in Santiniketan. She left Vishwa Bharti to attend her ailing mother in Europe and continued her education at the University of Oxford. After the death of her mother, she attended the Badminton School and then enrolled at Somerville College in 1937 to study History.

Indira Gandhi: Personal Life

Indira gandhi: career in indian politics.

After her marriage in 1942, Indira Gandhi served her father and the first Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru unofficially. In the late 1950s, she serves as the President of the Indian National Congress. In 1964, Jawaharlal Nehru died and she was appointed as a Rajya Sabha member. She served as the Minister of Information and Broadcasting under the then Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri.

In 1996, after the death of Lal Bahadur Shastri, she was elected as the leader by the Congress legislative party.

In January 1966, Indira Gandhi became the first and only female Prime Minister of India to date. Moraji Desai served as the Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister under Indira Gandhi's cabinet. At the beginning of her first term as the Prime Minister, media and opposition parties criticised her as 'Goongi Gudiya'.

In 1967 General Elections, Congress Party's magic started vanishing due to the widespread disenchantment over the rising prices of commodities, unemployment, economic stagnation and a food crisis. For the first time, Congress lost in the majority of states. Despite this, Indira Gandhi managed to win from the Raebareli constituency and promised to devalue the rupee. The wheat import from the US fell due to political differences.

In 1969, she faced differences due to her socialist policies. She supported independent candidate V. V. Giri for the vacant post of President of India, rather than supporting the official Congress party candidate Neelam Sanjiva Reddy.

She also announced bank nationalism without consulting the then Finance Minister, Moraji Desai. She nationalised 14 largest banks in India in 1969.

After all these decisions, the then Congress President S. Nijalingappa expelled her from the INC citing indiscipline. This, in turn, angered Indira Gandhi and she formed her own Congress Party known as Congress (R) with most of the MP's from the party on her side. The other side was known as Congress (O). The Indira Gandhi faction lost its majority in the Parliament, but with the support of several regional parties remained in power.

In 1971, 'Garibi Hatao' was the slogan for Indira Gandhi's political bid in response to the opposition's slogan as 'Indira Hatao'. The Garibi Hatao slogan and the proposed anti-poverty programs gave her independent national support. These programs were designed to bypass dominant rural castes. The voiceless poor will now gain political worth and weight. The anti-poverty programs were carried out locally and were funded by the Central Government.

Indira Gandhi after winning the 1971 elections, served as the PM again. In 1971, despite facing pressure from America, Indira Gandhi defeated Pakistan in the Indo-Pakistan War and led to the liberation of East Pakistan into independent Bangladesh. After the Bangladesh liberation war in 1971, the then President, V. V. Giri awarded her with India's highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna. Opposition leader Atal Bihari Vajpayee hailed her as 'Goddess Durga'.

Despite the Indira wave, Congress Government faced several problems in this term due to high inflation (caused by wartime expenses), droughts in India and the 1973 oil crisis.

On June 12, 1975, the Allahabad High Court declared 1971 elections void on the grounds of electoral malpractice. In 1971, her opponent Raj Narain alleged several major as well as minor instances of the use of government resources for campaigning. She asked her colleague Ashok Kumar Sen to defend her in the court and also provided evidence herself in the court. However, 4 years later, in 1975, the High Court of Allahabad found her guilty of dishonest election practices, excessive election expenditure, and of using government machinery and officials for party purposes.

The court ordered her to strip off her parliamentary seat and banned her from running the office for the next six years. However, Indira Gandhi refused to resign and announced to move to the Supreme Court. As soon as the news of Allahabad's HC verdict spread, thousands of supporters demonstrated outside Indira's house and pledged their loyalty.

On June 25, 1975, Indira Gandhi imposed a 21-month long emergency across India. The proclamation was signed a day before by the then President of India Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed under Article 352 of the Constitution because of the prevailing internal disturbance. The emergency was withdrawn on March 21, 1977. The emergency allowed the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to rule by decree. The elections, freedom of the press and constitutional rights were suspended.

Indira Gandhi: Things named after her

Awards and Competitions

1- Indira Gandhi Award for Best Debut Film of a Director

2- Indira Gandhi Award for National Integration

3- Indira Gandhi Boat Race

4- Indira Gandhi Paryavaran Puraskar

5- Indira Gandhi Prize

1- Indira Gandhi Arena

2- Indira Gandhi Athletic Stadium

3- Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts

4- Indira Gandhi Stadium, Alwar

5- Indira Gandhi Stadium, Solapur

6- Indira Gandhi Stadium (Una)

7- Indira Gandhi Stadium, Vijayawada

8- Indira Priyadarshini Stadium

9- Indira Gandhi Centre for Indian Culture, Phoenix, Mauritius

10- Indira Gandhi Indoor Stadium

1- Indira Gandhi Children's Hospital

2- Indira Gandhi Co-operative Hospital

3- Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences

4- Indira Gandhi Medical College

5- Indira Gandhi Memorial Hospital

6- North Eastern Indira Gandhi Regional Institute of Health and Medical Sciences

Current Government Programmes

1- Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme

2- Indira Canteens

Former Central Government Schemes

1- Indira Awas Yojana

2- Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme

3- Indira Gandhi Canal Project (Funded by World Bank)

4- Indira Kisan Vikas Patra

5- Indira Gandhi Garib Kalyan Yojna

Former State Government Schemes

1- Indira Gandhi Utkrishtha Chhattervritti Yojna for Post Plus Two Students by Himachal Pradesh Government (Sponsored by Central Government)

2- Indira Gandhi Women Protection Scheme by Maharashtra Government

3- Indira Gandhi Prathisthan by Uttar Pradesh Government

4- Indira Kranthi Patham Scheme by Andhra Pradesh Government

5- Indira Gandhi Nahar Pariyojana Scheme by Kerela Government

6- Indira Gandhi Vruddha Bhumiheen Shetmajoor Anudan Yojana by Maharashtra Government

7- Indira Gandhi Nahar Project (IGNP), Jaisalmer by Rajasthan Government

8- Indira Gandhi Niradhar Yojna by Maharashtra Government

9- Indira Gandhi Kuppam by Kerela Government

10- Indira Gandhi Drinking Water Scheme, 2006 by Haryana Government

11- Indira Gandhi Niradhar Old, Landless, Destitute women farm labour Scheme by Maharashtra Government

12- Indira Gandhi Women Protection Scheme by Maharashtra Government

13- Indira Gaon Ganga Yojana by Chattisgarh Government

14- Indira Sahara Yojana by Chattisgarh Government

15- Indira Soochna Shakti Yojana by Chattisgarh Government

16- Indira Gandhi Balika Suraksha Yojana by Himachal Pradesh Government

17- Indira Gandhi Garibi Hatao Yojana (DPIP) by Madhya Pradesh Government

18- Indira Gandhi super thermal power project by Haryana Government

19- Indira Gandhi Water Project by Haryana Government

20- Indira Gandhi Sagar Project, Bhandara District Gosikhurd by Maharashtra Government

21- Indira Jeevitha Bima Pathakam by Andhra Pradesh Government

22- Indira Gandhi Priyadarshani Vivah Shagun Yojana by Haryana Government

23- Indira Mahila Yojana Scheme by Meghalaya Government

24- Indira Gandhi Calf Rearing Scheme by Chhattisgarh Government

25- Indira Gandhi Priyadarshini Vivah Shagun Yojana by Haryana Government

26- Indira Gandhi Calf Rearing Scheme by Andhra Pradesh Government

27- Indira Gandhi Landless Agriculture Labour scheme by Maharashtra Government

Museums and Parks

1- Indira Gandhi Planetarium

2- Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya

3- Indira Gandhi Wildlife Sanctuary

4- Indira Gandhi Wildlife Sanctuary and National Park

5- Indira Gandhi Zoological Park

Transport Infrastructure

1- Indira Gandhi Canal

2- Indira Gandhi International Airport

Universities and Institutes

1- Indira Gandhi Agricultural University

2-Indira Gandhi Centre for Atomic Research

3-Indira Gandhi Delhi Technical University for Women

4- Indira Gandhi Institute of Developmental Research

5- Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences

6- Indira Gandhi Institute of Technology (Delhi)

7- Indira Gandhi Institute of Technology (Orissa)

8- Indira Gandhi Medical College

9- Indira Gandhi National Forest Academy

10- Indira Gandhi National Open University

11- Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Akademi

12- Indira Gandhi Institute of Physical Education and Sports Sciences (University Of Delhi)

13- North Eastern Indira Gandhi Regional Institute of Health and Medical Sciences

14- Gandhi Memorial International School

15- Srimati Indira Gandhi State Secondary School, Quartier Militaire, Mauritius

Indira Gandhi: Posthumous Honours

1- The Southernmost point of India 'Indira Point' is named after Indira Gandhi.

Indira Gandhi: Legacy

1- Despite facing pressure from America, Indira Gandhi defeated Pakistan and led to the liberation of East Pakistan into independent Bangladesh. After the Bangladesh liberation war in 1971, the then President, V. V. Giri awarded her with India's highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna.

2- In 1999, she was named as the 'Woman of the Millennium' in an online poll by BBC.

3- 42nd Amendment of the Indian Constitution at the time of Emergency can be listed as a part of her legacy.

4- In 2011, Bangladesh Swadhinata Sammanona, Bangladesh's highest civilian award was posthumously conferred on Indira Gandhi for her outstanding contributions in the Bangladesh liberation war in 1971.

5- In 2020, she was named among world's 100 powerful women who defined last century by Time Magazine.

6- Indira Gandhi was amongst the first Indians whose wax statue is at Madame Tussauds, London.

Get here current GK and GK quiz questions in English and Hindi for India , World, Sports and Competitive exam preparation. Download the Jagran Josh Current Affairs App .

- India Election Result 2024

- Lok Sabha Election Results 2024

- Election Commission of India

- India T20 World Cup Squad 2024

- ECI Results 2024

- T20 World Cup 2024 Points Table

- UP Election Result 2024

- Bihar Election Result 2024

- AP Election Results 2024

- Rajasthan Election Result 2024

Latest Education News

UP Election Result 2024 Live: Check Lok Sabha Vote Count for SP, BJP, Congress Party

India Election Results 2024 Live Updates: NDA Leads in 294 Seats, INDIA Bloc Lead in 231 Seats, Check Stats and Key Facts Here

Delhi Lok Sabha Election Result 2024 LIVE: BJP's Manoj Tiwari, Kamaljeet Sehrawat, and Ramvir Singh Bidhuri Leading by Big Margins

NEET UG Result 2024 Declared: Check Results at exams.nta.ac.in

Sultanpur Lok Sabha Election Result 2024: Sultanpur Lok Sabha Election Result 2024: Maneka Gandhi or Rambhual Nishad, Who Will Win here?

Kaiserganj Lok Sabha Election Results 2024 Declared: Karan Bhushan Singh from BJP Won by 148843+ Votes

Election Results 2024 Stats: State, Party-wise and Candidates Lok Sabha Election Results and Analysis

AP Election Results 2024 LIVE Updates: TDP in the Lead Check District or City Wise Result of Andhra Pradesh Lok Sabha Elections at results.eci.gov.in, Latest Updates Here

Mandi Election Result 2024: Kangana Ranaut Won in Mandi Chunav by 74755 Votes

Bihar Saran Lok Sabha Chunav Result 2024: रोहिणी या रूडी, कौन जीत रहा बिहार की सारण सीट? पाटलिपुत्र से मिसा आगे या पीछे

Rajasthan Lok Sabha Election Result 2024: राजस्थान के जयपुर से बीजेपी की मंजू शर्मा, राजसमन्द से महिमा कुमारी जीतीं

Rajasthan Lok Sabha Election Results 2024: BJP Leads Winners List, Check Latest Live Updated Results Here

UP Lok Sabha Election Result 2024 Live: यूपी लोकसभा चुनाव में वाराणसी से इतने मार्जिन से जीते नरेंद्र मोदी, यहां देखें नवीनतम अपडेट

Bihar Saran Election Result 2024: By How Many Votes Rohini Acharya Leading the Lok Sabha Seat? Latest Updates on Vote Counting

Purnia Election Result 2024: By How Many Votes Pappu Yadav Leading the Lok Sabha Seat? Latest Updates on Vote Counting

Kaiserganj Election Result 2024: कैसरगंज सीट से करण भूषण सिंह ने 148843 वोटों से जीती बाजी

Ghazipur Lok Sabha 2024: क्या पारस नाथ दे पाएंगे अफजाल अंसारी को टक्कर? जानिए वोट काउंटिंग की लेटेस्ट अपडेट

Haryana Lok Sabha Chunav Result 2024: हरियाणा में कांग्रेस और BJP में कड़ी टक्कर, सबसे तेज नतीजे यहां देखें

KTET Previous Year Question Paper: Download Kerala TET PDF with Answers Here

CBSE Class 10 Elements Of Business Syllabus 2024-25: Download Free PDF For Board Exam!

- International

- Today’s Paper

- LIVE: LOK SABHA RESULTS 2024

- Kerala Election Results

- Bengal Election Results

- Andhra Election Results

- Karnataka Results

- UP Election Results

Indira Gandhi

Indira gandhi news.

1952 to 2019: A look at India's general election results so far

June 04, 2024 4:48 pm

Look at the history of general election and how the people have voted in India in previous elections.

To say the world only became curious about Gandhi after Richard Attenborough’s film is sheer ‘mann ki baat’, not fact

June 03, 2024 10:20 am

Certainly ‘Gandhi’ and its eight Oscars made Mahatma Gandhi part of international pop culture’s mainstream. But if there is anything India managed to export successfully to the world, even before 1982, other than curry and yoga, it’s undoubtedly Mahatma Gandhi

For kin of other Indira Gandhi assassin, no plans to enter electoral politics in Punjab

May 31, 2024 9:13 am

When asked who he thought will win the Gurdaspur Lok Sabha seat, Gurnam Singh says it appears the Congress candidate Sukhjinder Singh Randhawa is a favourite.

In Faridkot, Indira Gandhi assassin’s son raises 2015 sacrilege case to draw votes

May 27, 2024 9:32 pm

Sarabjeet Singh Khalsa, son of Beant Singh, is contesting as an Independent in the seat that was at the centre of the Guru Granth Sahib desecration case

Why Congress hit ‘400 paar’ in 1984 elections, how Rajiv Gandhi’s tenure was marred by struggles

May 22, 2024 10:11 am

After Indira Gandhi’s assassination and a lack of coordination among opposition parties – including the BJP – the Congress won the highest-ever seats for a single party. Read in part 8 of our series on the history of India's general elections.

1977 Lok Sabha elections: Emergency imposition, first non-Congress Govt, and a promise belied

May 17, 2024 2:47 pm

In Part 6 of our series on India’s Lok Sabha elections, we take a look at the the first elections post Emergency, where Indira Gandhi and the Congress party lost to the Janata Party coalition.

From Feroze to Rahul: Brief history of Rae Bareli, bastion of Gandhi-Nehru family

May 17, 2024 2:39 pm

Since India’s first election in 1952, Congress has held the Rae Bareli Lok Sabha seat for 66 of 72 years. As Rahul Gandhi files his nomination from the seat, a brief history.

Congress fights for women, BJP reduced them to election jumla

May 03, 2024 2:04 pm

Whenever heinous attacks occur on women, Rahul Gandhi raises his voice. Our Prime Minister, on the other hand, pretends that women don’t exist

How Indira Gandhi returned to power in 1971 Lok Sabha polls, amid political turmoil and Congress split

May 17, 2024 2:02 pm

Indira took oath as Prime Minister once again on March 18, 1971. In the lead up to the polls, there was a split in the Congress party. How did it still manage a victory? Read in part 5 of our series on the history of India's Lok Sabha elections.

Rajnath Singh in Gujarat: Indira Gandhi scored a half-ton in toppling govts, but we're accused of killing democracy

April 30, 2024 8:16 am

Defence Minister Rajnath Singh says that for BJP, Lok Sabha polls have begun in Surat, where its candidate was declared to have been elected unopposed.

INDIRA GANDHI PHOTOS

As Modi embarks on US visit, a look at Indian PMs attending State dinners at White House

June 20, 2023 9:15 pm

Here's a look at Indian Prime Ministers with US Presidents during their State Dinners over the years since India gained Independence.

As Rahul Gandhi turns 53, a look at his life and politics: From the archives

June 19, 2023 2:46 pm

As Rahul Gandhi turns 53, we take a look at his life and politics. Take a look at pictures from Express Archives.

On Indira Gandhi's 105th birth anniversary, a look back at the Iron Lady's journey in politics

November 19, 2022 2:44 pm

Kangana Ranaut to Suchitra Sen: 9 actresses who have portrayed Indira Gandhi on screen

July 14, 2022 1:22 pm

Ahead of Kangana Ranaut's portrayal of Indira Gandhi in her directorial debut Emergency, here is a look at actresses who have played the Iron Lady on screen.

Rare images of Jawaharlal Nehru on his 57th death anniversary

May 27, 2021 11:59 am

May 27, 2021 marks the 57th year of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru aka Chacha Nehru's demise. Following are some rare archival images commemorating highlights of his lifetime.

On Sonia Gandhi's 73rd birthday, here are some rare photographs that you wouldn’t have seen

December 10, 2019 6:44 am

The Congress interim chief Sonia Gandhi turned 73 Monday. She has decided not to celebrate her birthday in the wake of rape incidents across the country and growing concerns over women’s security.

Indira Gandhi's birth anniversary: Rare photos of the 'Iron Lady' from Express archives

November 19, 2019 12:33 pm

Today marks the 102nd birth anniversary of India’s first and only female prime minister Indira Gandhi. Political leaders from across the spectrum paid rich tributes to the ‘Iron Lady of India’.

Indira Gandhi’s birth anniversary: Rare photos of the ‘Iron Lady’

November 20, 2018 7:05 am

Today marks the 101st birth anniversary of India’s first and only female prime minister Indira Gandhi.

Close aide to Indira Gandhi, Congress veteran R K Dhawan passes away

August 07, 2018 9:24 am

Veteran Congress leader Rajinder Kumar Dhawan who was a close aide of former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi breathed his last at B L Kapur hospital on Monday.

A look at Time magazine's most iconic covers featuring women

December 08, 2017 4:20 pm

The Time magazine in 2017 chose a bunch of brave women, those who had spoken up against sexual harassment as the Person of the Year. Here's a look at some similar iconic covers of the magazine featuring women.

INDIRA GANDHI VIDEOS

Priyanka Gandhi takes a political Plunge, appointed Congress in-charge of UP East

June 22, 2020 6:04 pm

Ahead of the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the Congress Wednesday appointed Priyanka Gandhi Vadra as general secretary of Uttar Pradesh East. She will take charge in the second week of February.

Rare pictures: Protests at the Boat Club

June 22, 2020 6:20 pm

Take a look at some of the candid pictures of protests at Boat Club in Delhi . This is part of a weekly photo series where we bring you some unguarded moments captured over the years by The Indian Express photographers’ network.

Indu Sarkar: Who Is Playing Sanjay Gandhi, Indira Gandhi And More, Complete Gallery Of Who’s Who In The Film

June 22, 2020 7:00 pm

Congress exposed by its alliance partner: BJP

January 11, 2016 1:00 pm

New Delhi, Jan 11 (ANI): Taking a jibe at the Congress after a report published on the Bihar Government's official website said former prime minister Indira Gandhi's regime was worse than the British raj. The Bharatiya Janata Party ( BJP) National secretary Shrikant Sharma on Monday said the grand old party now stands exposed at the hands of its alliance partner.

Had Indira Gandhi not listened to Siddhartha Shankar Ray the emergency would not have happened

June 29, 2015 10:01 am

I hold three people responsible for making Sanjay Gandhi the unconstitutional authority: R K Dhawan

June 29, 2015 9:58 am

EXPLAINED | The Emergency and the significance of June 12

June 16, 2015 2:30 pm

Rahul Gandhi, Congress leader, won the Rae Bareli seat in Uttar Pradesh with a huge margin of 4 lakh votes, surpassing his mother Sonia Gandhi's victory in 2019. BJP's Dinesh Pratap Singh came in second and BSP's Thakur Prasad Yadav was third. Sonia nominated Rahul in hopes of continuing the Gandhi family's legacy in the constituency.

Best of Express

Jun 04: Latest News

- Elections 2024

- Political Pulse

- Entertainment

- Movie Review

- Newsletters

- Web Stories

India Votes 2024

Lok Sabha election result: BJP-led NDA ahead, but margin narrower than predicted

BJP Tamil Nadu chief K Annamalai trails in Coimbatore Lok Sabha seat

West Bengal: Congress’s Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury trails TMC’s Yusuf Pathan in Baharampur

CEC on Modi’s anti-Muslim speeches: ‘We decided not to touch top two leaders of BJP and Congress’

BJP’s Smriti Irani trails in Uttar Pradesh’s Amethi Lok Sabha seat

Lok Sabha elections 2024: The story of the rise and fall of the Election Commission of India

Indore: NOTA votes over 2 lakh in constituency where Congress candidate joined BJP days before polls

Suspended JD(S) leader Prajwal Revanna trails in Karnataka’s Hassan seat

Stock markets plunge with BJP’s dwindling Lok Sabha tally

Jammu and Kashmir: Ex-CMs Omar Abdullah and Mehbooba Mufti trail in Baramulla, Anantnag-Rajouri

Five biographies through which to revisit the strange life and times of Indira Gandhi

November 19 marked her 99th birth anniversary..

Had she lived, Indira Gandhi would have turned 99 on November 19, 2016. That was the age to which her long-standing rival and former colleague, Morarji Desai, lived.

Indira was born in 1917, exactly a year after her father Jawahar Lal Nehru met Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi for the very first time, and several months after the Russian Revolution swept aside the old Tsarist order and led to the eventual rise of the Soviet Union. Nehru makes the latter connection in a letter to Indira on her thirteenth birthday, holding it out to her as a happy portend throughout her childhood. It is perhaps only fitting that the Soviet Union was to be Indira Gandhi’s most loyal ally, despite her avowed non-alignment.

Everything about her gives rise to fierce passions. There are those who declare unequivocally that she was the finest Prime Minister of India – and that one needs only look at Bangladesh for proof. There are others who hotly dispute this, stating the exact opposite, holding her responsible for rupturing the fabric of Indian democracy in the Emergency years. There are those who laud her secular politics, and those who revile her mismanagement of the Punjab situation, especially her decision to send tanks into the Golden Temple.

Five minutes and a quick hashtag search on twitter today will reveal to you the persistence of this polarisation. This strobe-lit drama of extreme positions is apt for social media, perhaps. But for those who do not wish to measure life in Prufrockian coffee spoons, what is of interest is precisely that which is invariably elided over in bang-smash assessments: the minor details of the long years. The chiaroscuro of light and shadow that, twinned in biographical material and news stories, tell the story of India too. Perhaps this is the reason why so many and such various writers have chosen to write about her life – for it was a heady mix of enigma and drama.

Out of the many biographies of Indira Gandhi, we have picked out five that matter:

Indira Gandhi: A Biography , Pupul Jaykar, 1988

Cultural activist and life-long crusader for Indian handicrafts, Pupul Jaykar was a close friend of Indira Gandhi’s – they met in their teens – and her intimate biography is filled with wonderful anecdotes and moving accounts of Indira Gandhi’s encounters with common people in the course of her travels across the country. It draws from her many recorded interviews with people who’d lived through these interesting times: RN Kao, the grand old spymaster of India; LK Jha, Cabinet Secretary and Ambassador to the United States during the historic war of liberation in Bangladesh; Ganga Saran Sinha, close associate of Jayprakash Narayan; Siddhartha Shankar Ray, Chief Minister of West Bengal; and countless others. She also records rare stories of Indira’s interactions with Jiddu Krishnamurti during the Emergency years.

“I was to visit Varanasi in August [1976] and went to see Indira to ask if there was anything I could do. I found her agitated, reports had reached her of attempts to beautify Varanasi. ‘The city needs cleaning up,’ she said, ‘but to beautify Varanasi has ominous overtones.’ She asked me to speak to the Commissioner and attempt to discover what was happening to the city. ... As we walked along the lane, the Commissioner said casually that the Governor desired to drive by car to Vishwanathji. I expressed surprise. ‘You cannot take a car through this lane,’ I said. ‘We are broadening the lane,’ he said. ‘How?’ He said, ‘We will break down the walls of some of these houses and pave the road so that a car can go through.’ ‘How can you break down seventeenth-eighteen century buildings?’ I enquired in horror. ‘These stones are many centuries old.’ ~~~ We drove to Kamacha, the road which was being ‘beautified’. Kamacha looked as if a bomb had fallen on it. A bulldozer stood to one side, with two eyes painted on the front. It had finished its task of beautification. It had bulldozed, cut through the front of houses leaving sitting-rooms with half the floor space cut away; rooms were open to the road, verandas smashed. Any impediment that came in the way of broadening the road had been removed. The map used to determine what was an encroachment was dated 1920. In the eyes of the authorities, in a city of exploding population, no fresh housing was needed or had been authorised after 1920 and every house built after that was an encroachment.” ~~~ By now the furious owners of the buildings surrounded me and insisted on giving me photographs of the site, to show the Prime Minister. I was shaken and on my return to Delhi went immediately to see Indira Gandhi. I told her what I had seen, what the Commissioner had told me and handed over the photographs. She hit the ceiling. I had never seen her so angry; she picked up the telephone and asked her Special Assistant, RK Dhawan, to put her through Narayan Dutt Tiwari, then Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh. She exploded when she spoke to him. Did he know what was happening in Varanasi? She said she had seen the photographs and would he come immediately to Delhi to see her. She put down the phone, put her hands to her face and said, ‘What is happening in this country? No one seems to tell me.’ There was utter despair and sorrow in her voice. ‘Do you think they would have really broken down Vishwanath Gali? She was aware of the gravity and consequences of such an act. — From Chapter Four, Part VI (1975 to 1977)

Indira Gandhi: Return of The Red Rose (1966); That Woman: Her Seven Years in Power (1973); Indira Gandhi: The Last Post (1985), Khwaja Ahmad Abbas

The immensely popular novelist, film-writer and columnist Khwaja Ahmad Abbas wrote the very first biography of Indira Gandhi, Return of the Red Rose , which was dashed off in three months after she became the Prime Minister of India in 1966. The title refers to the slogans that greeted Mrs Gandhi when she disembarked from her car in front of Gate No. 1 of Parliament House, on her way to the Central Hall where votes were being cast to pick her or Morarji Desai as the next Prime Minister of India, after the death of Lal Bahadur Shastri. Indira Gandhi had pinned a Nehruvian red rose to her brown Kashmiri shawl, seeing which the crowds began to chorus loudly, ‘Lal Gulaab Zindabad!’

The second volume draws its name from Yahya Khan’s dismissal of Indira Gandhi (“That Woman!”) before her dismissal of him, as it were, while The Last Post begins with her assassination, records the spiralling riots against the Sikhs in Delhi, and then goes back in time to trace the last few years of her leadership, ending with an interview with Rajiv Gandhi, the young Prime Minister in the present.

Abbas’s narrative is jaunty and anecdotal, both rooted and lofty, in a uniquely Indian way, allowing our innate oral tradition to inform the telling of every story, whether serious, comic or heroic. It is very different from the other biographies; and therein lies its charm.

“It was spring-time in Kashmir, and the flowers were all out to greet the couple [Feroze and Indira] on their honeymoon. They were as happy as any newly-wedded couple has ever been, but even in that time of bliss they could not forget the lonely man in Anand Bhawan who was sweltering in the heat of the plains to prepare the country for the final struggle. From Gulmarg they sent a jointly signed telegram: WISH WE COULD SEND YOU SOME COOL BREEZE FROM HERE. He must have been touched by their affectionate concern but Jawaharlal summoned his celebrated and subtle sense of humour to promptly send the telegraphic reply. THANKS. BUT YOU HAVE NO MANGOES.” — From "Honeymoon Behind Bars", "Return of The Red Rose"

Indira: The Life of Indira Nehru Gandhi , Katherine Frank (2001)

A serious, rigorously researched book written by a professional biographer, Katherine Frank’s Indira is exquisitely detailed, and recreates Indira Gandhi’s life with a meticulous eye. While the other four biographers listed here had all known Mrs Gandhi, the person, with some degree of familiarity, Frank neither knew her nor lived in India when she was the prime minister.

Instead, liberated by this, perhaps, she recreates the life and times of Indira Gandhi through deep and sustained research – over six years, in India and England – and the degree of remove provides a certain freshness to her work. However, the Western slant also means that there are certain things that do not sit well with Frank’s own assessment of Indira Gandhi – her later religiosity, for instance, seems to contradict her secularism – and Frank seems a bit embarrassed by it. And yet, as Indians know, an embracing of Hindu rituals can co-exist with a secular practice in public life.

(Ideally, reading Jaykar and Frank together should take care of that problem completely!)

“Indira was actually in Calcutta, addressing a huge rally of half-a-million people at the Calcutta Brigade Grounds, when the Pakistani planes made their raid. Just as she was saying, ‘India stands for peace. But if a war is thrust on us we are prepared to fight, for the issues involved are our ideals as much as our security,’ an aide rushed to the podium and handed her a slip of paper on which was scrawled the news of the Pakistani attack. She made no announcement, but hurriedly wound up her talk. Privately, she said to those with her, ‘Thank god, they’ve attacked us.’ She had not wanted to be seen as the aggressor, but had approved General Manekshaw’s secret plan to strike the next day. Now Indira’s strategy of deferred action and her exquisite sense of timing had been vindicated. That evening Indira flew back to Delhi, encircled by an escort of Indian air force planes. When they approached Delhi, there was nothing but darkness below: the capital was shrouded in a blackout. Indira went directly to her office in Parliament’s South Block and called an emergency meeting of the Cabinet. Then she met leaders of the opposition…The next morning she told the Lok Sabha: For over nine months the military regime of West Pakistan has barbarously trampled upon freedom and basic human rights in Bangladesh. The army of occupation has committed heinous crimes unmatched for their vindictive ferocity. Many millions have been uprooted, ten millions have been pushed into our country. We repeatedly drew the attention of the world to this annihilation of a whole people, to this menace to our security…West Pakistan has escalated and enlarged the aggression against Bangladesh into full war against India.” — From “Seeing Red”

Indira Gandhi: Tryst With Power , Nayantara Sahgal (1982)

Perhaps the least sympathetic of all these biographies is the one by Indira Gandhi’s cousin, the award-winning writer Nayantara Sahgal.

Sahgal’s is an interesting perspective. As a writer, an outsider to the system, someone whose job is to critique the establishment anyway, she can retain the purity of the Nehruvian idealism, and use that filter to take a hard look at her cousin’s years in hard core politics. An admirer of Jayprakash Narayan, Nayantara Sahgal captures the revolutionary eddies surrounding Indira’s “centre”, the student movements, the trade union struggles – and her sympathy is clearly on the side of the “outsiders”.

The relationship between Sehgal’s mother Vijayalakshmi Pandit and Indira’s mother Kamala Nehru had always been strained, and in spite of the many hours Indira spent with her aunt and her family, she never really forgot the tensions of her childhood. She carried her mother’s wound deep inside her, and it invariably cast a long unfortunate shadow on her relationship with Pandit, especially after Nehru’s death. Sahgal’s prism is edged with this aspect too.

“India’s leader, from 1966 to 1977, had been a woman whose childhood, education and family tradition had provided her with unusual opportunities for training in democratic ideals, yet whose own temperament had apparently never felt entirely comfortable with this inheritance. The stages of her career as prime minister made it plain she was not a democrat in practice. She firmly believed in her own indispensability. Concessions, compromise and discussion signified weakness to her, and opposition jarred and angered her. She needed the constant assurance of acceptance and loyalty to feel secure...Democracy was not Mrs Gandhi’s style, but it remained an insistent craving.” — From “Why Mrs Gandhi Called an Election”

Mrs Gandhi , Dom Moraes (1980)

The poet Dom Moraes’s father, the journalist and newspaper editor Frank Moraes, had written a rather delightful biography of Jawaharlal Nehru. It was almost to keep up with the eccentricity of the idea that two generations would write biographies of two generations that Dom Moraes, brilliant writer and, sometimes, almost insufferable Anglophile, attempted to write Mrs Gandhi . It is an eminently readable book, enlivened by a poet’s whimsy. (Dom Moraes was married to Leela Naidu at the time, and often it was she who translated his “mumbled” questions to Mrs G.)

“I had an extraordinary lunch, in 1975, in the palace where Mountbatten had once presided over the partition of India. The hostess was Mrs Gandhi, and the occasion was in honour of Prince Charles. In the garden of the presidential palace, filled with roses and trees, the guests lined up before lunch while Mrs Gandhi introduced the royal party to them. That is, she introduced Charles, and the Duke and the Duchess of Gloucester, but for some reason she omitted to introduce Mountbatten. He wandered along, behind the rest, explaining to everyone, ‘My name is Mountbatten,’ and, ‘waving his hand around the lawns, ‘and I had those trees planted.’ ~~~ After lunch, the Gloucesters shot off. I needed to see Mrs Gandhi, so, as she was saying goodbye to Prince Charles, I hovered around. The Prince having departed, I asked her for an appointment. ‘Yes, yes,’ she said. ‘Tomorrow. Phone my secretary.’ Her normally impassive face displayed some irritation. ‘Where?’ she asked, ‘are the Gloucesters? Weren’t you sitting with them?’ I said yes, but I thought they had left. ...Mrs Gandhi turned back to me and she was obviously furious. ‘They didn’t even say goodbye,’ she told me. ‘Don’t they know I am the Prime Minister of India?’” — From "Prince Consort"

Devapriya Roy is the author of two novels, one long-dragged-out-and-nearly-abandoned PhD thesis on the Natyashastra , and most recently of The Heat and Dust Project: The Broke Couple’s Guide to Bharat , which she co-wrote with husband Saurav Jha.

- Indira Gandhi

- Autobiographies

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Indira Gandhi : a personal and political biography

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

268 Previews

4 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station05.cebu on April 21, 2021

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)