An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Analyzing the evolution of technostress: A science mapping approach

Cristian salazar-concha, pilar ficapal-cusí, joan boada-grau, luis j camacho.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author. [email protected]

Received 2019 Jul 31; Revised 2020 Dec 2; Accepted 2021 Apr 1; Collection date 2021 Apr.

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

This paper analyzes the scientific map of technostress and the scientific production on this topic between 1982 and 2017, highlighting its structure, evolution, and trends in this field. A literature review based on bibliometric analysis of 246 records indexed in Scopus database was conducted. These publications were analyzed according to bibliometric indicators and through science maps with SciMAT. Co-occurrence of terms by grouping techniques was implemented. In addition, elaboration of maps of science and performance analysis for periods was executed. The main contribution of this work is to provide the first scientific map of technostress and a detailed understanding of the scientific production that predicts the directions of future research. The bibliometric analyses permit an overview of the growth, extent and distribution of the scientific literature related to the technostress and the study of the scientific production of an institution, country, author or research group.

Keywords: Technostress, Bibliometric analysis, Science mapping, Bibliometric indicators, SciMat

Technostress, bibliometric analysis, science mapping; bibliometric indicators; SciMat.

1. Introduction

Information and communication technologies (ICT) are fully integrated into our lives and jobs and will even more in the future. However, for many workers, ICT is surpassing the boundaries between labor and going into their personal experience. The use of ICT in different industries, the internet prevalence, and their ubiquitous nature, forces employees to deal with a considerable amount of information that grows along with the unprecedented development of new tools which demand employees be updated ( Shu et al., 2011 ). In many cases, employees are exposed to more information than they can efficiently manage ( Fisher and Wesolkowski, 1999 ).

The capabilities of a human being to deal with information is limited, although the development of new ICT is limitless. ITC's will be incorporated in our lives, and we will have fewer possibilities the be free of the technostress that they produce ( Shu et al., 2011 ). Technostress is a managerial problem that organizations are facing in a technologically dependent working environment ( Hung et al., 2015 ); in the organizational context, this reality can be attributed to ITC's constant presence and pace of change ( Ayyagari et al., 2011 ). Conceptualization of the technostress phenomenon is directly related to psychosocial effects associated with the use of ICT, and negative feelings related to the value of its use ( Burke, 2009 ; Carlotto et al., 2017 ).

Technostress is defined as the stress that people experience due to the use of information and communication systems and technologies ( Tarafdar et al., 2007 , 2019 ; Ragu-Nathan et al., 2008 ; Ayyagari et al., 2011 ; Chen and Muthitacharoen, 2016 ). It represents an emergent global phenomenon of academic research experienced by workers who transcends national and cultural boundaries ( Chen, 2015 ). For instance, at the global level, high levels of technostress have been reported among workers in some of the fastest growing economies, such as China ( Tu et al., 2005 ), India ( Sinkovics et al., 2002 ), Indonesia ( Suharti and Susanto, 2014 ) and the malaysian economy ( Ibrahim and Othman, 2014 ).

The purpose of the present research is, first, to explore the scientific production and evolution of technostress research, and second, provide the first technostress science map that shows the structure, evolution, and trends of this topic over time. We go further to investigate with several questions we considered relevant. First, who are the most prolific authors and most influential researches in technostress. Second, what are the journals with the highest number of publications related to technostress. Third, what are the main research topics in this topic. Fourth, what are the most used methods in leading publications about technostress. Fifth, what are the most critical themes in terms of production and impact. Finally, how have the themes evolved since 1982, and what topics have not yet been addressed or developed.

We have chosen a bibliometric research methodology allows to quantify and measure the performance, quality, and impact of generated maps and their components ( Cobo et al., 2012 ). A bibliographic analysis of the scientific production of technostress indexed from 1982 to 2017 in the Scopus database is carried out using a scientific mapping approach, analyzing its co-occurrence of terms through grouping techniques, making maps of science and performance analysis for to detect and visualize conceptual subdomains on technostress, as well as its thematic evolution. This study used a bibliometrics tool (SciMat v1.1.04) to build maps of science and strategic diagrams to analyze the temporal evolution of technostress main topics. The bibliometric analysis ( Pritchard, 1969 ) allows to quantify and measure the performance, quality, and impact of generated maps and their components ( Cobo et al., 2012 ) and provides objective criteria for evaluating scientific production ( Noyons et al., 1999 ).

The paper is structured as follows. In the next section, works of literature reviews of the selected articles related to technostress are highlighted. Afterwards, we explain the methodological approach, bibliometrics, and science mapping. Next, we analyze the findings. Finally, we propose some discussion and present conclusions regarding the limitations of the present research and a number of venues of future research.

2. Literature review

The phenomenon of technostress has been studied since the 1980s. First, it was associated with the automation of the workplace, and later it evolved to problems generated by employees use of ICT ( Polakoff, 1982 ; Shu et al., 2011 ). The term technostress was coined by the American psychotherapist Craig Brod as "a modern disease of adaptation caused by an inability to cope with the new computer technologies in a healthy manner” ( Brod, 1984 ) (p. 16). Years later, Weil and Rosen (1997) extended this definition because they did not agree that technostress was a disease. Technostress is "any negative impact on attitudes, thoughts, behaviors, or body psychology caused directly or indirectly by technology” ( Weil and Rosen, 1997 ) (p. 36). Despite the popularity of these first definitions, Connolly and Bhattacherjee (2011) pointed out that they did not have a theoretical or empirical basis.

From a transactional perspective, Caro and Sethi (1985) define technostress as "a perceived, dynamic adaptive state between the person and the environment, mediated by sociopsychological processes and influenced by the nature of the technological environment" ( Caro and Sethi, 1985 ) (p. 292). Therefore, technostress' experience depends on the users' individual characteristics, and their coping mechanisms or adaptive capabilities. In the organizational context, Tarafdar et al. (2007) indicated that technostress is caused by individual attempts and struggles to deal with constantly evolving ICTs and the changing physical, social, and cognitive requirements related to their use. They presented one of the most cited articles on the subject. The authors point out that technostress is a phenomenon that encapsulates a combination based on a condition of demand that causes stress. Technostress creators are defined as the factors that cause technostress for employees ( Krishnan, 2017 ) and the individual's response to it -adverse manifest results or tension. The work of reference ( Tarafdar et al., 2007 ) found that technostress was manifested behaviorally and psychologically in the following five dimensions: techno-overload, techno-invasion, techno-complexity, techno-insecurity, and techno-uncertainty ( Chen, 2015 ).

Although the above definitions are widely used in literature, Lei and Ngai (2014) stated these definitions assume that technostress is negative and do not conform to the nature of stress, which is neither positive or negative ( Webster et al., 2011 ). The authors define technostress as "the state of mental or physiological stimulation caused by the ICT usage for work purpose, which is usually attributed to increasing work overload, accelerated tempo, and erosion of personal time, among others" ( Lei and Ngai, 2014 ) (p. 2).

According to the transactional theory of stress ( Lei and Ngai, 2014 ), technostress can produce both negative and positive outcomes. In this regard, Tarafdar et al. (2019) indicated that stress embodies the condition of unbalance experienced by an individual between the demands of a situation and the ability to fulfill them.

Not all people react in the same way to certain internal or external alterations; hereof, two concepts arise, techno-eustress and techno-distress. Techno-eustress is positive stress that causes satisfaction, joy, increases vitality, does not cause imbalances and helps facilitate people's decision making ( Tarafdar et al., 2019 ). According this reference, it originates due to the emergence of new challenges and opportunities, allowing skill development. If adequate use of the technologies is given, these tools would facilitate the human being to reach new goals and challenges based on coexistence and interrelation with the new ICT, improving the performance and providing a faster use of new technologies.

Positive effects generated by technostress in people are to improve individual performance, greater efficiency, and innovation, and improve tasks made through ICT producing happiness and stability. Wajcman and Rose (2011) mentioned that first-line positions employees use information systems under positive or motivating pressures. The result of these positive pressures can increase efficiency (e.g., reducing time and effort, working faster, reducing errors) and effectiveness (e.g., improving service quality), resulting in better performance.

A risk that technostress can cause is that, in the long term, an individual could be overloaded and can, therefore, be stressed causing harm to his health. The worker will have a greater personal development thanks to the stress; however, it will be probably based on the detriment of his health; therefore, it is advisable not to exceed its use.

On the other hand, techno-distress is the negative effect generated by peoples use of ICT. It is originated due to the emergence of threats or obstacles ( Tarafdar et al., 2019 ). Since ICT goes beyond the competences of users, they see ICT's as a threat, not as a benefit. Ragu-Nathan et al. (2008) stated that individuals evaluate characteristics of information systems as threatening, with pressures that go beyond their own abilities. Moreover, they perceive negative consequences of not facing them.

In the beginning, researchers observed technostress as a disease; however, further researches consider it more as an inability of adopting changes in organization produced by ICT. Also, it is a natural reaction to technology where each employee must be prepared to adopt new technologies ( Jena, 2015 ) and organizations should be ready to support workers to reduce technostress ( Chen, 2015 ). Nimrod (2018) points out that technostress is a consequence of an individual's attempts and struggles to deal with evolving ICT regularly, as well as changes in cognitive and social needs related to their use.

First definitions of technostress were quite broad, and the authors often used the same concept to refer to different phenomena related to technostress such as Technophobia and Technoadiction ( Nimrod, 2018 ). Tarafdar et al. (2019) mention that technostress represents an emergent phenomenon of academic research. It is a process that includes the presence of technological environmental conditions, which are evaluated as demands or techno stressors, which bond the individual and require change. It is a physical and psychological discomfort condition caused by the interaction with the technology; however, these authors point out that technostress can be considered as positive or negative according to the personality of an individual and the reaction to the trigger situation of the fact.

In the last decade, three works of literature reviews related to technostress is highlighted. The first review conducted a search through Google Scholar. This Study analyzed 40 works with more than 4 quotations each ( Riedl, 2012 ). The second work reviewed relevant articles from different disciplines including the information systems, organizational behavior, psychological stress, and other disciplines where stress in workplaces had been studied. This study included articles published in 20 years (1995–2016). The Authors selected 27 articles for their analyses ( Tarafdar et al., 2019 ).

The third article analyzed 103 empirical studies. Specifically, they focused on the data and methods used in various researches and concluded that research in technostress constitutes a field conducive to multidisciplinary collaboration and the application of approaches that use multiple methods ( Fischer and Riedl, 2017 ).

3. Methodology

3.1. sources and data.

Cobo et al. (2011a) highlighted the concept of bibliometric analyses can be employed to carry out a performance analysis of the generated maps. This paper uses science mapping analysis, that is focused on monitoring a scientific field and defining the areas of research determining its cognitive and evolutionary structure, showing the structural and dynamic aspects of scientific research ( Noyons et al., 1999 ; Börner et al., 2003 ; Morris and Van der Veer Martens, 2008 ; Cobo et al., 2012 ). Two software tools have been used on the bibliometric analysis carried out in this study: a) The Scopus analysis tool allows conducting the performance bibliometric analysis and; b) The SciMAT software tool, which allows to carry out bibliometric analysis of content based on science maps. The publications were analyzed according to bibliometric indicators and through science maps with SciMat 1.1.04 version.

To provide a rigorous analysis, we followed the steps of a scientific mapping analysis ( Börner et al., 2003 ; Cobo et al., 2011a ): data recovery, data preprocessing, network extraction, network normalization, mapping, analysis and visualization. At the end of this process, we interpreted and obtained conclusions from the results.

In the data search stage, we use the Scopus database. It is a good choice among multidisciplinary databases ( Norris and Oppenheim, 2007 ). It offers a greater selection of journals in all different fields ( Goodman and Deis, 2007 ) and includes, in addition to articles, other document types such as books and conference proceedings ( Fingerman, 2006 ). In addition to the above, Scopus has a greater degree of singularity, containing a greater number of unique documents than other databases as WoS, which is of particular interest when making a selection of information sources ( Sánchez et al., 2017 ).

In order to create a representative corpus of documents for investigation all records containing one or more of the keywords “technostress” or “techno-stress” in the fields abstract, title and keywords were selected from the Scopus database. The tracking formula in Scopus was: TITLE-ABS-KEY (technostress OR "techno-stress") AND PUBYEAR >1981 AND PUBYEAR <2018.

A total of 246 publications were found, obtaining relevant data from each of them (title, authors, abstract, keywords, journal, volume, number, pages, year, direction and author affiliation) along with received appointments until August 17 of 2018. The sample is restricted to the period 1982–2017.

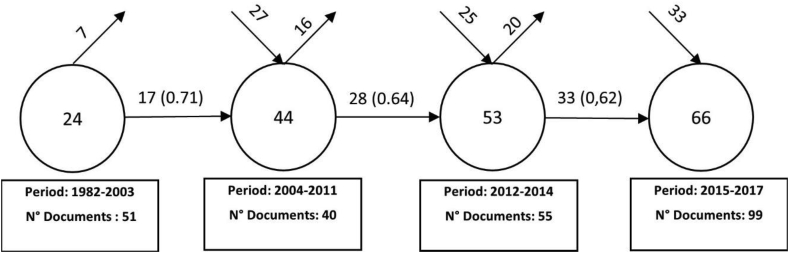

According to the combined trends in productivity, documents, citations and total citation, the period was divided into four discrete subperiods for evolutionary analysis. The time slice process is useful to divide the data into different time subperiods, or time slices, to analyze the evolution of the research field under study ( Cobo et al., 2011b ). Four discrete periods were established that identify the most relevant research topics, emerging topics, declining issues, and peripheral issues. Temporary segmentation has been established considering two criteria. The first of these periods, 1982–2003, refers to the main scientific milestones when the first publications on technostress are carried out and have served as theoretical frameworks in subsequent studies. In the periods 2004–2011 and 2012–2014 scientific groups from the United States and Europe appear that changed the orientation of this area of science due to the great technological leap that changed the usual way of work and lifestyle. Finally, 2015–2017 reflects current work and trends in the field of techno-stress science. On the other hand, it has been contemplated that the documentary volume of each period is representative enough to allow the detection of research lines. Scopus includes 51, 40, 55 and 99 documents respectively in each period.

3.2. Bibliometric analysis tools

With Scopus analysis tool, the main authors, universities, journals and other antecedents that characterize the scientific production on technostress will be analyzed preliminarily, for example, impact assessed by h-index ( Hirsch, 2005 ). To conduct the evolutionary evaluations, SciMat v1.1.04 was used. This tool carries out the publications' content analysis, allows constructing maps of the scientific production, which allow monitoring a scientific field, delimiting the areas of investigation to understand its intellectual, social and cognitive structure, as well as to analyze its structural evolution. To carry out the scientific mapping production associated with the technostress, the recommended stages were followed by ( Cobo et al., 2012 ). SciMAT allows building science maps based on the co-occurrences analysis that characterize each publication. Also, SciMAT helps to analyze the structural evolution to construct scientific maps and visualize the evolution of a scientific area ( Cobo et al., 2012 ). The bibliometric tools may produce a higher level of analysis of research trends, productivity in different fields or scientific connection patterns ( Ellegaard and Wallin, 2015 ). The analysis carried out by SciMat is based on the methodology of associated words or co-words analysis developed in the 1980s by the École des Mines de Paris with Leximappe software tool, which greatly promoted the analysis of Science and thematic maps ( Callon et al., 1983 , 1986 ). The advantages of using SciMAT compared to other bibliometric tools (e.g., Bibexcel, CiteSpace, CoPalRed, IN-SPIRE, VantajaPoint, VOsViewer) have been demonstrated ( Cobo et al., 2011a ).

In Addition, the thematic networks between keywords were established through this tool SciMAT allows identifying the importance of each thematic network by the construction of strategic diagrams through measures of analysis of thematic networks: centrality and density ( Callon et al., 1991 ). The centrality measures the topic's degree of strength of external links with other topics; this measure allows interpreting the importance of a topic in the overall development of a field of investigation. The density measures the internal cohesion of all links between the keywords that describe the topic and provides an idea of the level of development of that topic ( Cobo et al., 2011b ; Martínez et al., 2015 , 2018 ). Through centrality and density, a field of research can be represented in a strategic diagram.

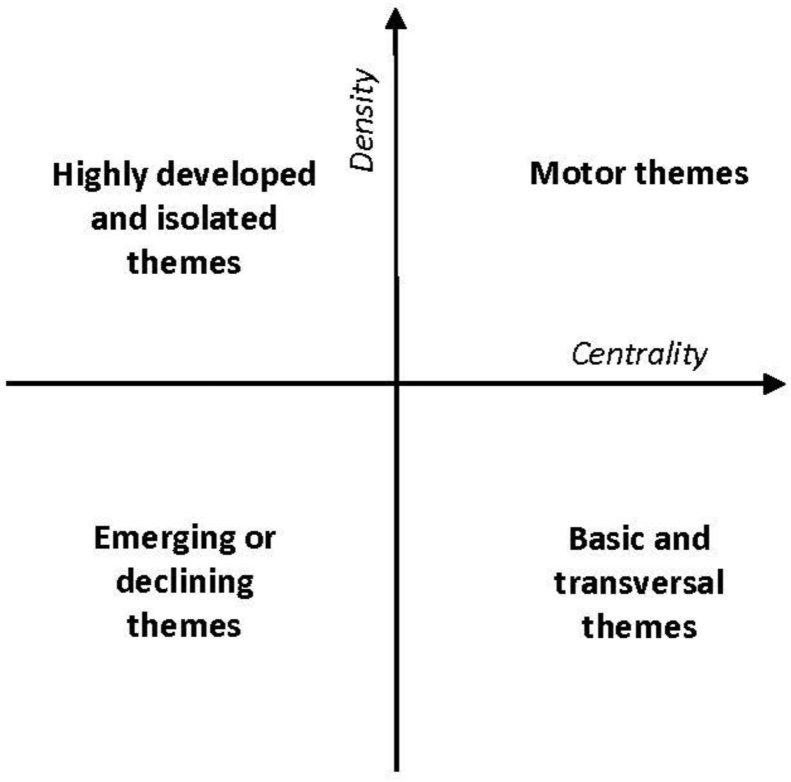

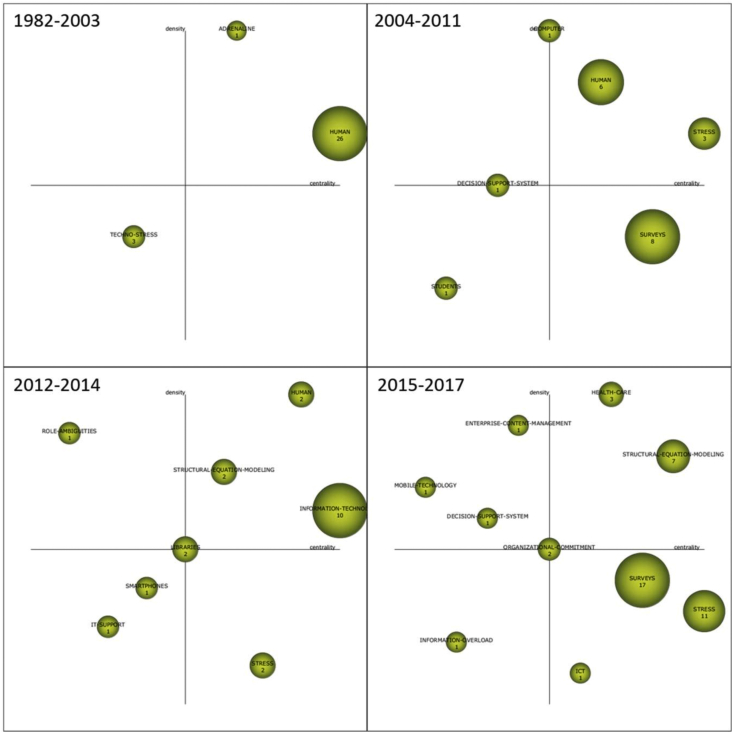

SciMat allows to characterize the importance of each thematic network with a scientific field that can be represented as a set of subjects classified in four categories and positioned on a two-dimensional space called strategic diagram ( Figure 1 ):

Right Upper Quadrant: Represents those subjects that are well developed and essential for the construction of the scientific field, since they represent a strong centrality and a high density. They are also called as "Motor themes" because they are fundamental for building the research area.

Upper left Quadrant: Represents those that correspond subjects well developed internally, but isolated from the rest of the subjects and have marginal importance in the development of the scientific field. They are called "Highly Developed and isolated themes" because they have little relevance for the field and these are specialized peripheric topics of the area.

Right lower Quadrant: Represents those basic themes that are important to the scientific field but are not well developed. They are called "Basic and Transversal themes" because they show relevant issues but with little development.

Left Lower Quadrant: Represents those that correspond to very few developed and marginal subjects with a low density and centrality. They are also referred to as "emerging or vanishing topics" because they include lack development and relevance topics.

The strategic diagram. Source ( Cobo et al., 2011b ):

4.1. Analysis

The first publications on technostress emerged in the year 1982. The journal Occupational Health & Safety , in its July 1982 issue, published the first article that included the concept of Technostress: “Technostress: Old villain in new guise” ( Polakoff, 1982 ). The same year, in October, The Personnel Journal published the article: "Managing Technostress: Optimizing the use of computer technology" ( Brod, 1982 ). These are the first studies that consider technostress as a modern disease caused by the inability of workers to use new technologies. In addition, these studies were realized based on observations of people's health effects.

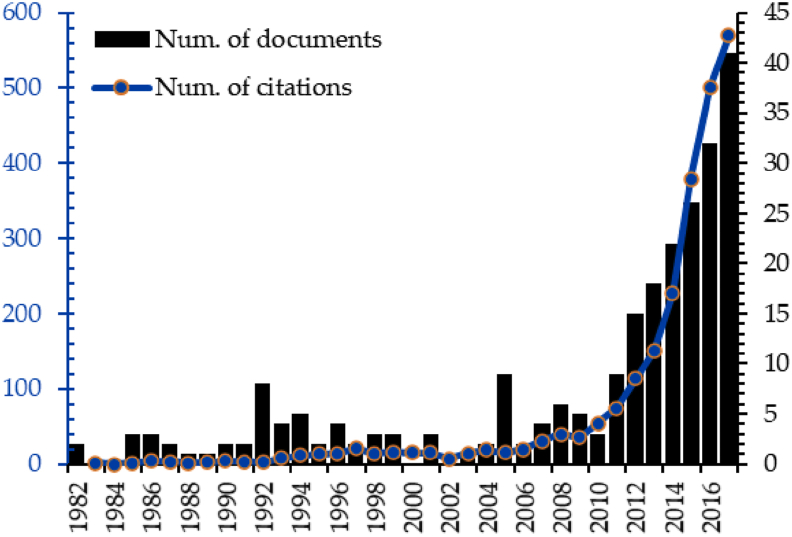

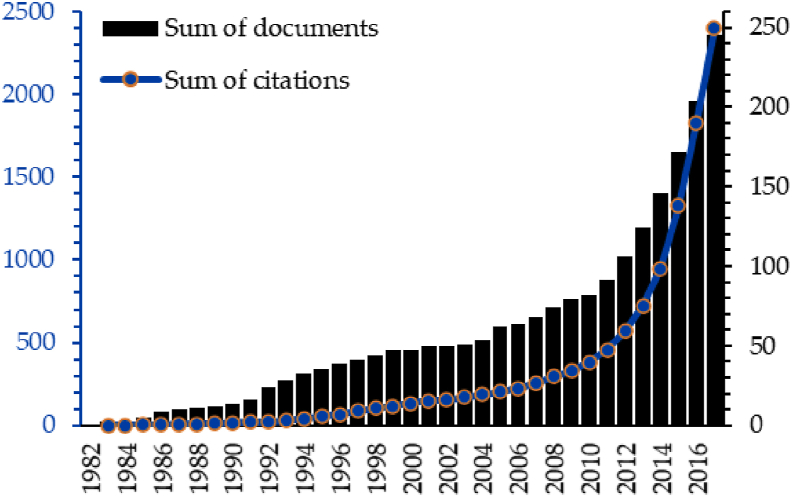

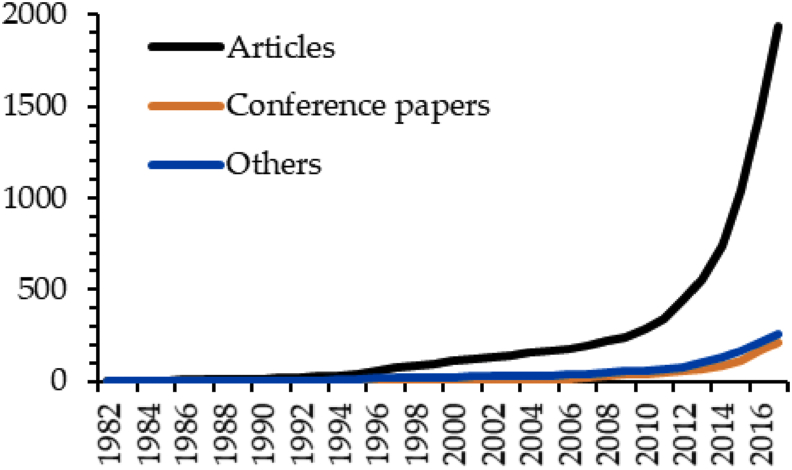

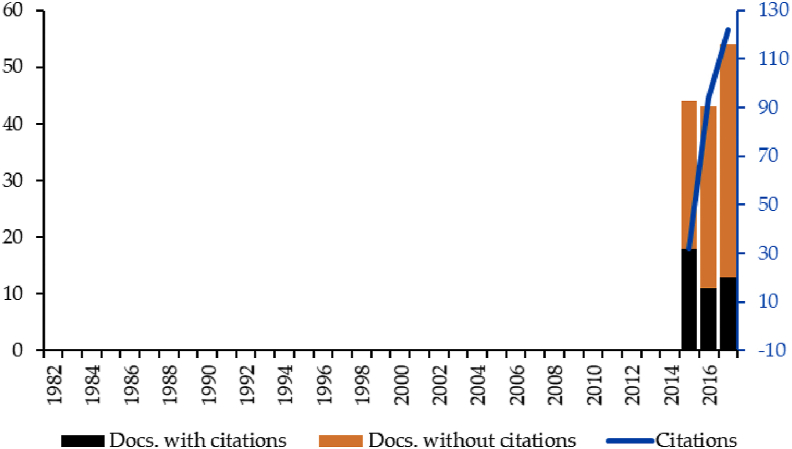

In 1984, Craig Brod published the book "Technostress: The human cost of the Computer revolution" ( Brod, 1984 ). Brod's works have been citated in many articles, and it is explained by being the two oldest articles in this field, and because has been considered one of the pioneers in studying and conceptualizing and defining technostress. The research development on technostress has progressed slowly and it has been consolidated from the year 2011, where different lines of research have been developed on this subject. Figure 2 shows the number of publications and citations received between 1982 and 2017, and Figure 3 shows the publications and citations cumulative frequency in the period studied.

Published items and appointments for each year.

Accumulated graph of publications and citations.

Since 2007, the number of citations and publications began to grow steadily due to the publication of three articles (Figures. 3 and 4 ). These three articles are the most cited in the study of this topic during the last ten years. In 2007, the first article "The impact of technical stress on stress and productivity of roles" ( Tarafdar et al., 2007 ) was published in the Journal of Management Information Systems , the first quartile journal in the Information Science & Library Science categories of Journal Citation Reports (JCR). In 2008, the second article "The consequences of technostress for end users in organizations: Conceptual development and validation" ( Ragu-Nathan et al., 2008 ) was published in Information Systems Research , journal of the second quartile in the JCR category. These two works built and validated a measuring scale on technostress creators called Technostress Questionnaire that it has been used in many numbers of subsequent publications (e.g., Shu et al., 2011 ; Srivastava et al., 2015 ; Alam, 2016 ; Krishnan, 2017 ) as shown in Figure 4 . Finally, in 2011, the article "Technostress: Technological Background and Implications" ( Ayyagari et al., 2011 ) was published in a first quartile journal in the JCR category ( MIS Quarterly ). Figure 5 depicts the cumulative number of quotations from the scientific production on technostress. It is observed that since the year 2007, citations on conference papers and other sources begin to appear.

Citations average value per published document per year.

Accumulated citations by types of scientific work.

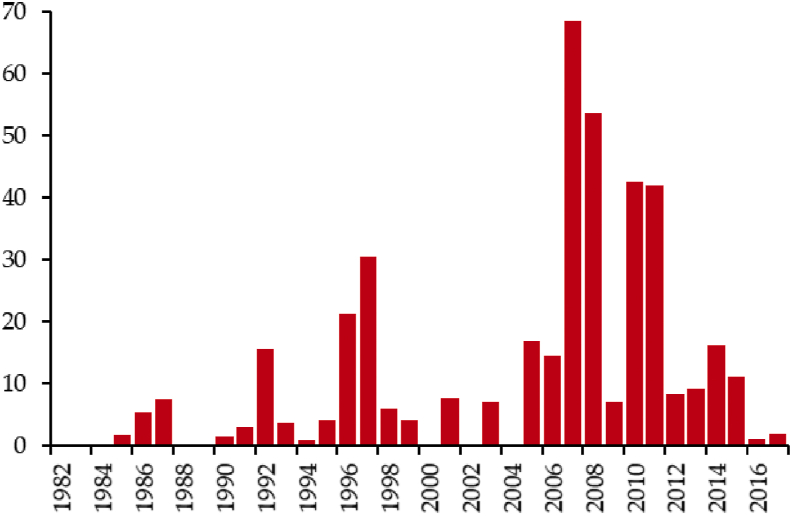

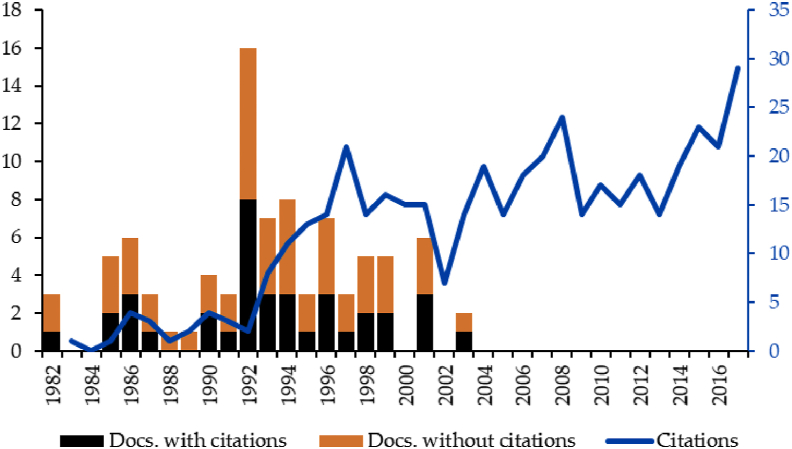

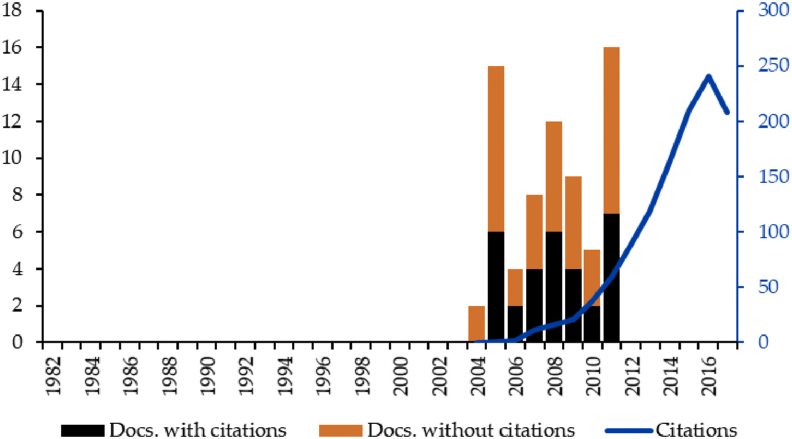

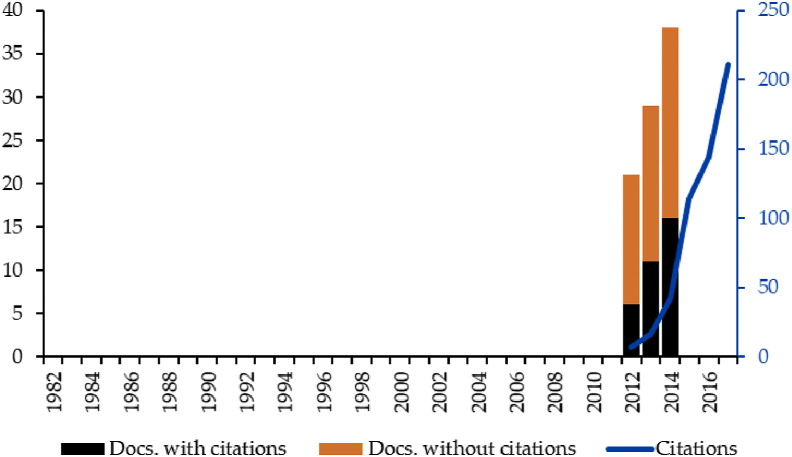

According to the combined trends of productivity, documents, citations and total citation, the period was divided into four discrete sub periods to conduct evolutionary analyses. Figures 6 , 7 , 8 , and 9 shows the number of citation-free publications for each year of the periods 1982–2003, 2004–2011, 2012–2014 and 2015–2017. It can be observed that from 1982-2003 ( Figure 6 ), where the first studies on technostress are carried out, the publications have served as theoretical frameworks in later studies (a). In the period 2004–2011 (Figures 7 and 8 ) citations take time to appear (approximately two years since an article is published), instead of in the period 2015–2017 ( Figure 9 ) citations appear in the same year of publication; therefore, the delay decreases from an article was published and quoted.

Publication citation evolution in period 1982–2003.

Publication citation evolution in period 2004–2011.

Publication citation evolution in period 2012–2014.

Publication citation evolution in period 2015–2017.

Table 1 presents the main published topics. It is appreciated that in the period 1982–2003, the scientific production on technostress was more oriented to the area of medicine and health. Technological innovations were incorporated into companies, and individuals had to adapt to these innovations and learn new skills to use them. Therefore, it is understandable that the interest of scientists in this period was analyzing the connection between the effects of the human health with the use of new technologies.

Topics published in indexed scientific documents 1982–2017.

Periods 2004–2011 and 2012–2014 were characterized because technostress publications are no longer aimed at studying the effects of technology focused on human health. "Computer Science" and "Social Sciences" appear in the first places.

Scientific groups from the United States and Europe changed the orientation in these periods. At that time, the global population entered the moment when most people have integrated into their life and work different ICT technologies. The development of technologies compared to the past period took a big jump; internet, social networks, smartphones, office automation software, and new business information systems changed the usual way of working and lifestyle ( Stadin et al., 2016 ; Haddadi Harandi et al., 2018 ).

In the last period, 2015–2017, the subject "Computer Science" as well as the previous two periods appears in the first place. In Addition, it is appreciated that the topic "Business, Management and Accounting" appears in second place and covers 10% of all the publications. "Medicine" and "Psychology" together cover 15% of all publications during this period.

Globally, technostress-related scientific production focuses on 3 Regions: North America (mainly the United States with 28% of production), European Union with 29% (notably Germany with 9%), East Asia and South-East (mainly Japan and China with 12% and 9% respectively).

Table 2 shows the most relevant publications, with more than 100 citations, are related to "Computer Science", "Business Management & Accounting" and "Psychology". Regarding to the number of citations stand out of study about used the person-environment fit model as a theoretical foundation ( Ayyagari et al., 2011 ). In another study, the authors used the transaction-based stress model as a theoretical lines ( Ragu-Nathan et al., 2008 ). It is also worth noting that, according to Yin et al. (2014) the most of the modern technostress research is based on the technostress questionnaire developed by Ragu-Nathan et al. (2008) .

Publications with more than 100 citations in Scopus between 1982-2017 (August 17, 2018).

Psychology, as a topic related to technostress, has been growing as research development area. As an example, the research "The Dark side of smartphone usage: Psychological traits, compulsive behavior and technostress" ( Lee et al., 2014 ), published in the journal Computers in Human Behavior . Researchers used the view from personality theories to explain compulsive behavior.

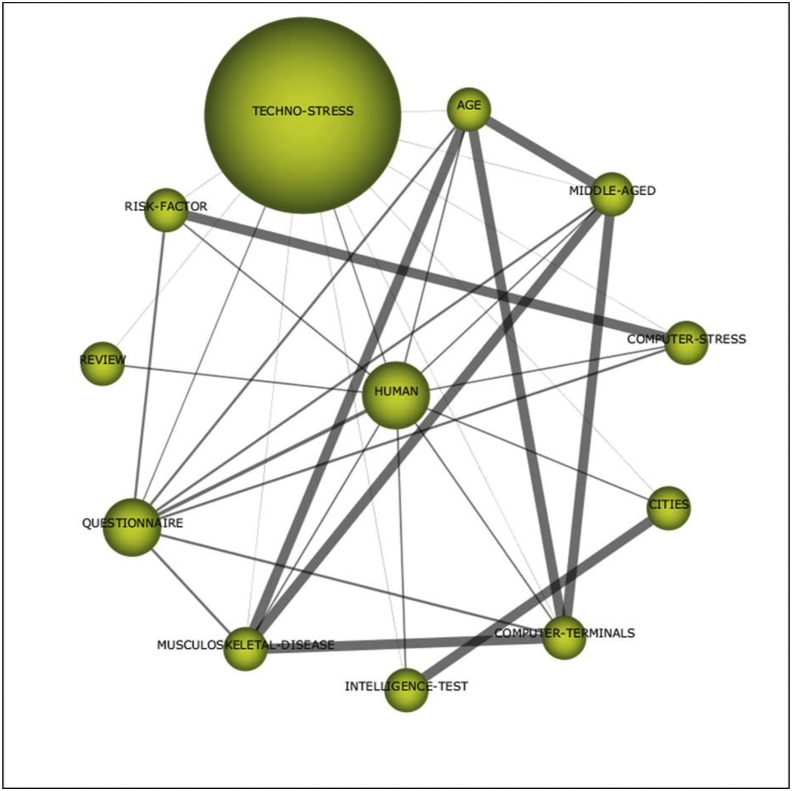

Table 3 exhibits the most used keywords in the articles in the period 1982–2017. Three groups of words are identified. All terms that connect with stress add 230 repetitions in all publications analyzed (technostress/techno-stress, stress, mental-stress, stress-psychological). Another group of words focuses on the human being (human, adult, female, male, human) which add up to 146 repetitions. A third group is composed of words related to technology (information systems, technology, information-and-communication technology) which add up to 88.

Number of keyword occurrences greater than 15 repetitions (August 17, 2018).

Related to authoring tendencies, authors who contributed to more than ten documents in all periods were identified ( Table 4 ). Noteworthy that most of the scientific production on technostress is generated by groups of authors that change their position in each publication. The authors with more than ten documents published, therefore with higher productivity in this field, are: Monideepa Tarafdar, Professor of information systems, affiliated to Lancaster University, England; and Professor Nobuyo Kasuga, member of the Shibaura Institute of Technology, Japan.

Top researchers on technostress and its h-index generated through SciMat in period 1982–2017.

period = 1982–2017.

In the case of h-index, Professor Monideepa Tarafdar presents the major h-index (h = 23), followed by Emeritus Professor T.S. Ragu-Nathan, from the University of Toledo in the United States, that holds an h-index = 22. Both researchers co-authored several publications on technostress. In the third place, with an h-index = 21, the Professor Ofir Turel, who belongs to the Department of Information Systems and Decision Sciences of the California State University Fullerton, United States. Table 4 presents that despite Nobuyo Kasuga holds second place in published documents, his h-index is the lowest since each of his publications has between one and two citations.

Journals with the most significant number of research papers published on technostress are presented in Table 5 . The journal with the largest number of publications is Computers in Human Behavior , which highlights the work presented by Lee et al. (2014) . The journal with the greatest impact factor is the Information Systems Journal , which highlights the article "Technostress: negative effect on performance and possible mitigations" ( Tarafdar et al., 2015 ).

Journal with the largest number of publications related to technostress (August 17, 2018).

Table 6 exhibits articles with more than 50 and less than 100 citations in the period studied. Works with the highest number of citations are published in the Journal of Occupational and Environment Medicine ( Berg et al., 1992 ; Arnetz and Wiholm, 1997 ).

Top ten papers with more than 50 and less than 100 citations in the period studied.

Cit. = N° citations (1982–2017).

4.2. Thematic analysis on the scientific production of technostress using SciMat

The production of technostress thematic analysis, in the superposition map ( Figure 10 ), it can be seen the co-appearance continuity of the terms that make up the titles of scientific documents indicating the number of terms per period and how these are repeated in the following period. Each circle represents a period of scientific production. The central numbers show the total terms of the period, the numbers on the oblique arrow up indicate the terms that did not have co-occurrence in the following period; those on the down arrow indicate the new terms that co-appeared in the next period and those of the horizontal arrow show the total terms that continued to co-appear, expressed in proportion in the parentheses. As can be seen in Figure 10 , in those four periods there was a similar behavior, with an average level of thematic overlap.

Therm overlapping map in the scientific production of technostress, indexed in Scopus the period 1982–2017. Data were retrieved on August 17, 2018 and processed in SciMat V. 1.1.04.

4.3. Analysis of research topics and thematic evolution

To analyze the most relevant topics related to technostress scientific production, a strategic diagram is presented for each period ( Figure 11 ). The size and number within the sphere are proportional to the set of documents linked to the particular research topic.

Strategic diagram of the scientific production on technostress, indexed in Scopus, for periods 1982–2003, 2004–2011, 2012–2014 and 2015–2017 (The quadrants correspond to Figure 1 ).

First period: 1982–2003. During the first 22 years the field revolves around three subjects ( Figure 11 ). According to the topic's performance measures indicated for this period in Table 7 and Figure 11 , "Human" stands out, who gets the largest number of documents reaching 300 citations and corresponds to the theme of greater centrality and density, consolidating as a motor topic. The theme "Adrenaline" appears as a driving theme, presenting only one publication in the period, but with a high number of citations. The theme "technostress" is categorized as emergent, presenting three publications with 7.3 average citations.

Performance of topics for technostress in four analysis periods.

Second period: 2004–2011. During these eight years, the field consists mainly of two motive themes "Human" and "Stress" and a basic and transversal theme "Surveys". Unlike the previous period, documents related to technostress revolves around six topics. The theme "Human" is consolidated as a driving theme; however, it decreases its number of documents from 6 to 2 in comparison with the previous period, but its average number of citations increased. The subject "Surveys" appeared in eight documents which are highly cited. The theme "Stress" appears as the driving theme and is the second most cited theme of the period.

Third period: 2012–2014. During this two-year period, documents related to technostress revolves around eight themes. The theme "Information Technology" appears as the driving theme and is the most important according to performance indicators; however, the theme "Human" despite having only two publications presents a higher average of citations. The theme "Stress" which in the previous period appeared as the driving theme, now appears like a basic and transversal theme. The topic "Structural-Equation-Modeling" appears as a driving theme, possibly because in the previous period scales were developed to measure the technostress.

Fourth period: 2015–2017. The field revolves around nine subjects. The themes "Surveys" and "Stress" consolidated as basic and transversal themes; "ICT" also appears as a transversal theme. "Health-Care" and "Structural-Equation-Modeling" appear as motive issues. Also "Organizational-Commitment" appears with an interesting average of citations. In this period, technostress studies tend to analyze the effects of technological stress associated with health care and commitment to the organization.

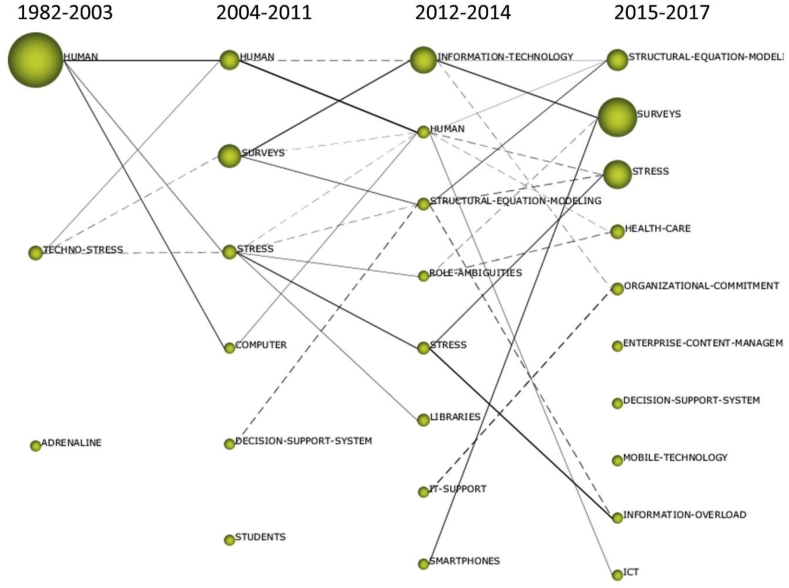

Figure 12 presents the thematic evolution of the investigated periods. The first column of nodes depicts the period of articles that were published between 1982 and 2003, which represent 21% of all documents analyzed. In this period the term technostress was formulated, and science was focused on analyzing the effect of stress associated with technology on human health. Main researches of this period were carried out by researchers from Japan and the United States. The leading journal where these works were published was the Japanese Journal of Psychosomatic Medicine . The performance of each topic in the period can be seen in Table 7 .

Thematic evolution for periods of study.

In the second period, between 2004 and 2011, 16% of all works investigated were presented. Main topics were centered on the human being, stress, and the computer, which are connected with the subject related to the human being of the first period. The technostress theme of the first period evolved into research related mainly to the human being and stress and measuring instruments.

The third and fourth periods, comprised between 2012-2014 and 2015–2017, which represent approximately 22% and 40% respectively of all published works on the subject area, start to develop measurement instruments that connect stress with information technologies and information overload. Most of these works developed theoretical models that were validated empirically through the technique of structural equation models. The study of stress associated with technology has given rise to works that relate stress to role ambiguity and its effect on health care (fourth period).

It is observed that in the last period researches are focused on the application of measuring instruments that strongly connect with information technologies, smartphones, role ambiguity, and health care. Likewise, the study of stress has given rise to investigations about the effect of information overload on human health. In this period, studies focused on organizational commitment related to technological support and the use of information technologies appear. Likewise, studies related to human health begin to be relevant, since globalization has democratized technology. The use of technology has become more frequent in organizations and people and has started to be observed within organizations, people's adverse effects related to information overload and the use of ICT.

In Figure 13 it is possible to observe how all the themes associated with the technostress are connected. In Figures 12 and 13 it can be seen that the scientific production investigated focuses on analyzing different factors associated with ICT that generate technostress and psychosocial risks in workers. There are also investigations that perform sociodemographic studies to determine how various factors such as age, gender, level of education, among others, can be related to technostress.

Thematic network associated to the topic technostress.

In the last two periods, the use of methodologies such surveys and questionnaires have multiplied to analyze, through structural equations, how different variables are correlated with technostress, such as self-efficacy, work overload, technological overload, role ambiguity, work at home, privacy invasion, job insecurity, job satisfaction, individual performance and productivity, technological dependence, innovation, use of social networks, mobile devices, technostress inhibitors, labor exhaustion, work environment, among others.

5. Discussion and conclusions

After a systematic literature review on technostress, the results present that the most influential works in the field of research correspond to those developed in the period 2004–2011. These correspond to the work of Ragu-Nathan et al. (2008) and Ayyagari et al. (2011) . Both studies applied questionnaires to ICT professionals and end-users in the United States. These works developed and validated theoretical measures and constructs that have served as the basis for modern research.

Regarding the most prolific authors standing out with more than ten documents: Monideepa Tarafdar, Nobuyo Kasuga and Qiang Tu, from the United Kingdom, Japan, and the United States, respectively. Authors with higher h-index: Monideepa Tarafdar from Lancaster University, T.S. Ragu-Nathan of the University of Toledo and Ofir Turel of California State University.

Journals with the highest number of published works correspond to Q1 journals: Computers in Human Behavior (United Kingdom), Information Systems Journal (United Kingdom) and Telematics and Informatics (Netherlands).

Technostress is an emerging research field with little fragmentation. The results show that the research field is in evolution and has not yet reached a state of maturity. Fifteen fundamental thematic areas have been identified with little relation between them. Initially, the mutual connections were not very related; however, in the period 2015–2017 these connections have been more prevalent. The analysis has shown that “Computer Science”, “Business, Management and Accounting”, “Social Sciences” and “Medicine” are significant themes. “Medicine "was the most significant topic in the period 1982–2003, and in the last period is the fourth. Researchers' tendency has been marked by investigating the stress caused by the use of ICT which affect the health of the human being and that generate stress and psychosocial risks in workers.

In general, technostress research has been developed as new technologies appear and advance in their use, leading to the need to know its repercussions on people's health at work (e.g., Arnetz and Wiholm, 1997 ; Brod, 1984 ; Weil and Rosen, 1997 ), in working groups, in organizations and in society in general (e.g., Brillhart, 2004 ; Tarafdar et al., 2007 ; Ayyagari et al., 2011 ; Tarafdar et al., 2015 ; Fischer and Riedl, 2017 ). Literature analysis has reported that the effect of different factors and sociodemographic variables associated with ICT such as age, gender, level of education, among others, can be related to technostress and its consequences on job outcomes such as organizational commitment, information overload, role ambiguities, invasion of privacy, job insecurity, job satisfaction and exhaustion, individual performance and productivity, technological dependence, among others.

Most research on technostress has been carried out in organizational settings, studying employees in specific sectors. In this work the publications with more citations correspond to works that incorporate the Technostress Questionnaire developed by Tarafdar et al. (2007) (e.g., Ragu-Nathan et al., 2008 ; Tarafdar et al., 2011 , 2010 ).

Technostress research has been evolving and has spread to other domains, adopting measures and terminologies to the relevant contexts. The impact of new mobile technologies and social communication tools to produce technostress in people has not been explored in depth. For example, Tarafdar et al. (2011) developed and validated a scale to measure anxiety for the use of the mobile computer; Lee et al. (2014) examined technostress derived from the use of smartphones, exploring its association with various psychological traits and compulsive use, as well as the registry of differences between users of smartphones and traditional mobile phones; in this line, other authors also examined the consequences of technostress mobile (e.g., Hung et al., 2015 ; Yin et al., 2014 ; Yu et al., 2009 ).

Other studies have examined technostress based on social network use, exploring both techno-stressors such as the degree of use and the number of friends, as well as consequences such as social overload and exhaustion ( Maier et al., 2015b ); It has also been explored how the use of social networks affect the performance of school work and happiness ( Brooks, 2015 ), or how it affects the elderly specifically ( Nimrod, 2018 ). Also, the literature has extended in the realization of critical analyzes arguing that in contrast to the negative consequences, technostress can generate positive effects in the improvement of efficiency and innovation ( Tarafdar et al., 2019 ).

Regarding research methods and data analysis, scholars have mainly carried out cross-sectional studies. They have used self-administered surveys, the technique of structural equations to validate their models and test their working hypotheses. In particular, the use of this technique began to increase as of 2005 and more frequently from 2011 onwards.

The thematic evolution reflects that the studies related to this field of science have developed slowly. It is appreciated that since 2016, there has been an increase in publications and citations. The subjects with more citations correspond to those included in the first three periods: "Surveys", "Human", "Stress", "Information technology" and "Smartphones" methods ( Fischer and Riedl, 2017 ).

In almost 40 years of research on technostress, some issues have not been addressed yet or are poorly developed. Technostress is a promising field of science to conduct studies related to different business environments, different types of workers and professions (including disabled). Also, studies can be performed through different modalities such as face-to-face, flexible, remote work, and homework, and various technologies and social networks. Besides, it is a field that facilitates studies to all managerial levels and non-working population as students, with different labor and sociocultural contexts that involve countries outside the developed or developing economies.

As evidenced in the bibliometric analysis of this work psychosocial research in the field of the introduction and use of ICTs is growing. In developing a framework of ICT demands and supports, there are several important general models of work stress ( Day et al., 2012 ). The theoretical models used in the works aim to describe what happens during the stress process and are based on theories that study human behavior rooted in social psychology ( Sonentag and Frese, 2013 ; Maier et al., 2015a ), such as the Theory of Reasoned Action and its extension ( Effiyanti and Sagala, 2018 ), the Socio-Technical Theory and Role Theory ( Tarafdar et al., 2007 ), Social Cognitive Theory ( Koo and Wati, 2011 ; Shu et al., 2011 ), Person-Environment Fit Model ( Ayyagari et al., 2011 ; Yan et al., 2013 ; Saganuwan et al., 2015 ), Transaction-Based Model of Stress ( Ragu-Nathan et al., 2008 ; Hung et al., 2011 ; Fuglseth and Sorebo, 2014 ; Lei and Ngai, 2014 ; Chandra et al., 2015 ; Fischer and Riedl, 2017 ), Job Demands-Resources Model ( Salanova et al., 2014 ; Wu et al., 2017 ), Technology Acceptance Model ( Maier et al., 2013 , 2015b , 2015c ), among others. Despite this, there are studies that do not have an explicit theoretical basis, nor do they have a theoretical basis that belongs to the organizational level.

The researchers who have studied organizational behavior describe the technostress as a collection of interrelated psychosocial constructions that negatively impact employees. Mentioning, in addition, that this line of research focuses on the transactions of employees at work in a de-balance situation that affects the results of the organization ( Atanasoff and Venable, 2017 ). We consider it important that new studies on this phenomenon ben addressed from different theoretical and methodological approaches.

Attitudes play an important role in the adoption of new technologies. Individuals do not necessarily accept technology based on their traits, but in relation to perceived benefits. For this reason, we consider that future studies could addressed research on the Theory of Reasoned Action. This theory pretends predicting the human behavior by linking attitudes, social pressure, and behavior ( Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980 ).

In the area of ICT, the impacts of attitude and norm subjective differ depending on whether the use of technology is voluntary or not. This background can lead to new researches that addresses his research on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). This theory relates behavior, intent, attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavior control. This theory posits that the intention is determined by the attitude of the individual, the degree to which a person has a favorable or unfavorable assessment of the behavior in question, the subjective norm and the perceived social pressure to perform the conduct or not ( Ajzen, 1991 ). TPB includes a third predictor of intent called perceived behavior control, which reflects an individual's perception that there are personal and situational impairments to behavior performance ( Grandón and Ramirez-Correa, 2018 ). This theory intent is the best determinant of behavior, but attitude, subjective norm and perceived control are those that facilitate understanding of the factors that explain actions ( Rao and Troshani, 2007 ). The TPB also explains almost any human behavior and not just the use of technological innovations ( Ajzen, 1991 ).

Today, because of the innovation caused by telework, new researches could address Socio-Technical Theory and study how this change in the way they work impacts the social structure of workers and their families ( Trist and Bamforth, 1951 ). Likewise, measure the effect of new variables that allow to inhibit or decrease the effects of technostress in the work at home. In the same vein, studies based on Stress Theory and Coping could measure the effect of the continued use of videoconference platforms and collaborative work platforms and measure if active breaks in telework can inhibit the effect of technostress caused by this modality.

In general, we have detected empirical, cross-cutting, and self-reporting studies. We recommend the conduct of new longitudinal studies that measure the effect of the use of ICTs, over a prolonged period, incorporating different neuroscientific techniques to expand the methodological framework in the field of cognitive and behavioral neurosciences. There are few cross-national and cross-country studies. This field of research reflects interesting opportunities for research related to experiments and neuroscience.

As limitations indicate that only the SCOPUS database was used and the works up to December 2017 were analyzed, however, a formula for bibliographic search is presented and therefore this work can be repeated and updated. The fact that by using a single concept, it is possible that studies related to the topic analysed, but in which the concept of "technostress" was not specifically mentioned, have been left out of the analysis. Another limiting factor of this research is that the word co-occurrence method was used for the analyzes and probably with another methodology (for example of common references) other results could come out, but in any situation the main works and their effect on this theme. There are few cross-national and cross-country studies. This field of research reflects interesting opportunities for research related to experiments and neuroscience.

We analyzed classic works that are fundamental in the formation of this area of science. For future research they may focus on analyzes of works published in recent years and check our conclusions and main evolutionary steps in this area. Also, it is possible to implement works using quantitative indices to describe the contribution of certain countries to the overall development of the technostress scientific field ( López-Muñoz et al., 1996 , 2008 ).

Modern literature has been incorporating new concepts related to positive stress. The techno-eustrés cause satisfaction, joy, increase vitality, produce no imbalances and help facilitate people's decision-making. Techno-eustres it originates due to the emergence of new challenges and opportunities, allowing them to develop their skills. If technologies are properly used, they would be tools that facilitate and enable humans to balance and live with new ICTs by enabling them to achieve new goals and challenges, improving their performance and integrating faster into the use of new technologies. Contrary to the dominant belief that stressors are always harmful stress can help people improve their work, motivate them at work and keep them on alert.

A solution to technostress is the prevention of this through tools that allow to inhibit and/or reduce the effects of stress caused by the technologies. We recommend that organizations implement coping strategies through the theoretical concept of technostress inhibitors. The literature reports that inhibitors have the potential to decrease the stress levels created in workers by the use of ICTs, which will, likely, increase their job satisfaction by providing advantages to organizations.

Additionally, it is necessary to determine the position of this research topic in connection with other sciences and for that it is recommended to carry out an analysis of the common references of the works to find out with which sciences the field of technostress is connected.

Declarations

Author contribution statement.

Cristian Salazar-Concha: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Pilar Ficapal-Cusí: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Joan Boada-Grau, Luis J. Camacho: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was partially funded by the Vicerrectoría de Investigación, Desarrollo y Creación Artística of the Universidad Austral de Chile, Chile.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991;50:179–211. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ajzen I., Fishbein M. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1980. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. https://www.amazon.es/Understanding-Attitudes-Predicting-Social-Behavior/dp/0139364358 Available at: [ Google Scholar ]

- Alam M.A. Techno-stress and productivity: survey evidence from the aviation industry. J. AIR Transp. Manag. 2016;50:62–70. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arnetz B. Techno-stress: a prospective psychophysiological study of the impact of a controlled stress-reduction program in advanced telecommunication systems design work. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 1996;38:53–65. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199601000-00017. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Arnetz B., Wiholm C. Technological stress: psychophysiological symptoms in modern offices. J. Psychosom. Res. 1997;43:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00083-4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Atanasoff L., Venable M.A. Technostress: Implications for adults in the workforce. Career Dev. Q. 2017;65:326–338. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ayyagari R., Grover V., Purvis R. Technostress: technological antecedents and Implications. MIS Q. 2011;35:831–858. [ Google Scholar ]

- Berg M., Arnetz B., Lidén S., Eneroth P., Kallner A. Techno-Stress: a psychophysiological study of employees with VDU-associated skin complaints. J. Occup. Med. 1992;34:698–701. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Börner K., Chen C., Boyack K. Visualizing knowledge domains. Annu. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2003;37:179–255. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brillhart P. Technostress in the workplace: managing stress in the electronic workplace. J. Am. Acad. Bus. 2004;5:302–307. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brod C. Managing technostress: optimizing the use of computer technology. Persica J. 1982;61:753–757. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brod C. Addison-Wesley; Reading, MA: 1984. Technostress: the Human Cost of Computer Revolution. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brooks S. Does personal social media usage affect efficiency and well-being? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015;46:26–37. [ Google Scholar ]

- Burke M. The incidence of technological stress among baccalaureate nurse educators using technology during course preparation and delivery. Nurse Educ. Today. 2009;29:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2008.06.008. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Callon M., Courtial J., Laville F. Co-word analysis as a tool for describing the network of interactions between basic and technological research: the case of polymer chemsitry. Scientometrics. 1991;22:155–205. [ Google Scholar ]

- Callon M., Courtial J., Turner W., Bauin S. From translations to problematic networks: an Introduction to co-word analysis. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1983;22:191–235. [ Google Scholar ]

- Callon M., Law J., Rip A. The Macmillan Press Ltda; London, United Kingdom: 1986. Mapping the Dynamics of Science and Technology: Sociology of Sciencein the Real World. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carlotto M., Welter G., Jones A. Technostress, caree commitment, satisfaction with life, and work-family interaction among workers in information and communication technologies. Curr. Events Psychol. 2017;31:91–102. [ Google Scholar ]

- Caro D., Sethi A. Strategic management of technostress - the chaining of Prometheus. J. Med. Syst. 1985;9:291–304. doi: 10.1007/BF00992568. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chandra S., Srivastava S.C., Shirish A. Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, PACIS 2015 - Proceedings (Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems) 2015. Do technostress creators influence employee innovation? https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85011106115&partnerID=40&md5=37e5875f7aa24150e17aeecb550bf5de Available at: [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen L. Validating the technostress instrument using a sample of Chinese knowledge workers. J. Int. Technol. Inf. Manag. 2015;24:65–81. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen L., Muthitacharoen A. An empirical investigation of the consequences of technostress: evidence from China. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. 2016;29:14–36. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cobo M.J., López-Herrera A.G., Herrera-Viedma E., Herrera F. Science mapping software tools: review, analysis, and cooperative study among tools. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011;62:1382–1402. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cobo M., López-Herrera A., Herrera-Viedma E., Herrera F. An approach for detecting, quantifying, and visualizing the evolution of a research field: a practical application to the Fuzzy Sets Theory field. J. Informetr. 2011;5:146–166. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cobo M., López-Herrera A., Herrera-Viedma E., Herrera F. SciMat: a New Science mapping analysis software tool. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2012;63:22688. [ Google Scholar ]

- Connolly A., Bhattacherjee A. AMCIS 2011 Proceedings (Detroit) 2011. Coping with the dynamic process of technostress, appraisal and adaptation; pp. 4–8. [ Google Scholar ]

- D’Arcy J., Herath T., Shoss M. Understanding employee responses to stressful information security requirements: a coping perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2014;31:285–318. [ Google Scholar ]

- Day A., Paquet S., Scott N., Hambley L. Perceived information and communication technology (ICT) demands on employee outcomes: the moderating effect of organizational ICT support. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012;17:473–491. doi: 10.1037/a0029837. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Effiyanti T., Sagala G.H. Technostress among teachers: a confirmation of its stressors and antecedent. Int. J. Educ. Econ. Dev. 2018;9:134–148. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ellegaard O., Wallin J.A. The bibliometric analysis of scholarly production: how great is the impact? Scientometrics. 2015;105:1809–1831. doi: 10.1007/s11192-015-1645-z. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fingerman S. Web of science and Scopus: current features and capabilities. Issues Sci. Technol. Librarian. 2006;48:4. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fischer T., Riedl R. Technostress research: a nurturing ground for measurement pluralism? Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2017;40:375–401. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fisher W., Wesolkowski S. Tempering technostress. IEEE Technol. Soc. Mag. 1999;18:28–42. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fuglseth A.M., Sorebo O. The effects of technostress within the context of employee use of ICT. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014;40:161–170. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goodman D., Deis L. Update on Scopus and web of science. Charlest. Advis. 2007;8:15–18. [ Google Scholar ]

- Grandón E., Ramirez-Correa P.E. Managers/owners’ innovativeness and electronic commerce acceptance in Chilean SMEs: a multi-group Analysis based on a structural equation model. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2018;13:1–16. [ Google Scholar ]

- Haddadi Harandi A., Bokharaei Nia M., Valmohammadi C. Kybernetes; 2018. The Impact of Social Technologies on Knowledge Management Processes: the Moderator Effect of E-Literacy. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hirsch J.E. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:16569–16572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507655102. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hung W.-H., Chang L.-M., Lin C.-H. PACIS 2011 - 15th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems: Quality Research in Pacific (Brisbane, QLD) 2011. Managing the risk of overusing mobile phones in the working environment: a study of ubiquitous technostress. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hung W., Chen K., Lin C. Does the proactive personality mitigate the adverse effect of technostress on productivity in the mobile environment? Telematics Inf. 2015;32:143–157. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ibrahim H., Othman N. The influence of techno stress and organizational-is related support on user satisfaction in government organizations: a proposed model and literature review. Inf. Manag. Bus. Rev. 2014;6:63–71. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jena R. Impact of technostress on job Satisfaction : an empirical study among Indian academician. Int. Technol. Manag. Rev. 2015;5:117–124. [ Google Scholar ]

- Koo C., Wati Y. What factors do really influence the level of technostress in organizations? (An empirical study) Information-AN Int. Interdiscip. J. 2011;14:3647–3654. [ Google Scholar ]

- Krishnan S. Personality and espoused cultural differences in technostress creators. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;66:154–167. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee Y.K., Chang C.T., Lin Y., Cheng Z.H. The dark side of smartphone usage: psychological traits, compulsive behavior and technostress. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014;31:373–383. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lei C., Ngai E. 35th International Conference on Information Systems. Association for Information Systems); Auckland: 2014. The double-edged nature of technostress on work performance: a research model and research agenda; pp. 1–18. [ Google Scholar ]

- López-Muñoz F., Boya J., Marín F., Calvo J.L. Scientific research on the pineal gland and melatonin: a bibliometric study for the period 1966–1994. J. Pineal Res. 1996;20:115–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1996.tb00247.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- López-Muñoz F., García-García P., Sáiz-Ruiz J., Mezzich J., Rubio G., Vieta E. A bibliometric study of the use of the classification and diagnostic systems in psychiatry over the last 25 years. Psychopathology. 2008;41:214–225. doi: 10.1159/000125555. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maier C., Laumer S., Eckhardt A. Information technology as daily stressor: pinning down the causes of burnout. J. Bus. Econ. 2015;85:349–387. [ Google Scholar ]

- Maier C., Laumer S., Eckhardt A., Weitzel T. Giving too much social support: social overload on social networking sites. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2015;24:447–464. [ Google Scholar ]

- Maier C., Laumer S., Weinert C., Weitzel T. The effects of technostress and switching stress on discontinued use of social networking services: a Study of Facebook use. Inf. Syst. J. 2015;25:275–308. [ Google Scholar ]

- Maier C., Laumer S., Weitzel T. International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2013): Reshaping Society through Information Systems Design (Milan) 2013. Although i am stressed, i still use it! theorizing the decisive impact of strain and addiction of social network site users in postacceptance theory; pp. 314–325. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84897740873&partnerID=40&md5=bfd67e5d1fb48aa53605c201f76610a1 Available at: [ Google Scholar ]

- Martínez M., Cobo M., Herrera M., Herrera-Viedma E. Analyzing the scientific evolution of social work using science mapping. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2015;25:257–277. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martínez M., Rodríguez F., Cobo M., Herrera-Viedma E. What is happening in social work according the web of science? Cuad. Trab. Soc. 2018;30:125–134. [ Google Scholar ]

- Morris S., Van der Veer Martens B. Mapping research specialties. Annu. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:213–295. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nimrod G. Technostress: measuring a new threat to well-being in later life. Aging Ment. Health. 2018;22:1080–1087. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1334037. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Norris M., Oppenheim C. Comparing alternatives to the Web of Science for coverage of the social sciences’ literature. J. Informetr. 2007;1(2):161–169. https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:infome:v:1:y Available at: [ Google Scholar ]

- Noyons E., Moed H., Luwel M. Combining Mapping and citation analysis for evaluative bibliometric purposes: a bibliometric study. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1999;50:115–131. [ Google Scholar ]

- Polakoff P. Technostress: Old villain in new guise. Occup. Health Saf. 1982;51:32–33. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pritchard A. Statistical bibliography or bibliometrics. J. Doc. 1969;25:348–349. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ragu-Nathan T.S., Tarafdar M., Ragu-Nathan B.S., Tu Q. The consequences of technostress for end users in organizations: conceptual development and validation. Inf. Syst. Res. 2008;19:417–433. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rao S., Troshani I. A conceptual framework and propositions for the acceptance of mobile services. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2007;2:61–73. [ Google Scholar ]

- Riedl R. On the biology of technostress: literature review and research agenda. Database Adv. Inf. Syst. 2012;44:18–55. [ Google Scholar ]

- Riedl R., Kindermann H., Auinger A., Javor A. Technostress from a neurobiological perspective: system breakdown increases the stress hormone cortisol in computer users. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2012;4:61–69. [ Google Scholar ]

- Saganuwan M.U., Ismail W.K.W., Ahmad U.N.U. Conceptual framework: AIS technostress and its effect on professionals’ job outcomes. Asian Soc. Sci. 2015;11:97–107. [ Google Scholar ]

- Salanova M., Llorens S., Ventura M. Technostress: the dark side of technologies, In: Korunka C., Hoonakker P., editors. The Impact of ICT on Quality of Working Life. Springer; Dordrecht: 2014. pp. 87–103. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sánchez A.D., de la Cruz Del Río Rama M., García J.Á. Bibliometric analysis of publications on wine tourism in the databases Scopus and WoS. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2017;23:8–15. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shu Q., Tu Q., Wang K. The impact of computer self-efficacy and technology dependence on computer-related Technostress : a social cognitive theory perspective. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2011;27:923–939. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sinkovics R., Stottinger B., Schlegelmilch B., Sundaresan R. Reluctance to use technology-related products: development of a technophobia scale. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2002;44:477–494. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sonentag S., Frese M. Stress in organizations. In: Weiner I., Schmitt N., Highhouse S., editors. Jhon Wiley & Sons; Hoboken: 2013. pp. 477–494. (Handbook of Psychology). [ Google Scholar ]

- Srivastava S.C., Chandra S., Shirish A. Technostress creators and job outcomes: theorising the moderating influence of personality traits. Inf. Syst. J. 2015;25:355–401. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stadin M., Nordin M., Broström A., Magnusson Hanson L., Westerlund H., Fransson E.I. Information and communication technology demands at work: the association with job strain, effort-reward imbalance and self-rated health in different socio-economic strata. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 2016;89:1049–1058. doi: 10.1007/s00420-016-1140-8. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Suharti L., Susanto A. The impact of workload and technology competence on technostress and performance of employees. Indian J. Commer. Manag. Stud. 2014;5:1–7. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tarafdar M., Bolman E., Ragu-Nathan T. Technostress: negative effect on performance and possible mitigations. Inf. Syst. J. 2015;25:103–132. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tarafdar M., Cooper C.L., Stich J.F. The technostress trifecta - techno eustress, techno distress and design: theoretical directions and an agenda for research. Inf. Syst. J. 2019;29:6–42. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tarafdar M., Tu Q., Ragu-Nathan B., Ragu-Nathan T. The impact of technostress on role stress and productivity. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007;24:301–328. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tarafdar M., Tu Q., Ragu-Nathan T. Impact of technostress on end-user satisfaction and performance. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2010;27:303–334. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tarafdar M., Tu Q., Ragu-Nathan T., Ragu-Nathan B. Crossing to the dark side: examining creators, outcomes, and inhibitors of technostress. Commun. ACM. 2011;54:113–120. [ Google Scholar ]

- Trist E.L., Bamforth K.W. Some social and psychological consequences of the longwall method of coal-getting: an examination of the psychological situation and defences of a work group in relation to the social structure and technological content of the work system. Hum. Relat. 1951;4:3–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tu Q., Wang K., Shu Q. Computer-related technostress in China. Commun. ACM. 2005;48:77–81. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wajcman J., Rose E. Constant connectivity: rethinking interruptions at work. Organ. Stud. 2011;32:941–961. [ Google Scholar ]

- Webster J., Beehr T., Love K. Extending the challenge-hindrance model of occupational stress: the role of appraisal. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011;97:505–516. [ Google Scholar ]

- Weil M., Rosen L. Wiley; New York: 1997. Technostress: Coping with Technology Work Home Play. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wu J., Wang N., Mei W., Liu L. Sixteenth Wuhan International Conference on E-BUSINESS, Ed. Tu, YP (2500 UNIV DR NW, CALGARY, AB T2N 1N4. Canada: Univ Calgary Press); 2017. Does techno-invasion trigger job anxiety? Moderating effects of computer self-efficacy and perceived organizational support; pp. 241–250. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yan Z., Guo X., Lee M.K.O., Vogel D.R., Yan Z. A conceptual model of technology features and technostress in telemedicine communication. Inf. Technol. People. 2013;26:283–297. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yin P., Davison R., Bian Y., Wu J., Liang L. Proceeding of the 19th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems PACIS 2014. 2014. The sources and consequences of mobile technostress in the workplace. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yu J.C., Kuo L.H., Chen L.M., Yang H.J., Yang H.H., Hu W.C. Assessing and managing mobile technostress. WSEAS Trans. Commun. 2009;8:416–425. [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

- View on publisher site

- PDF (1.8 MB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Leadership and technostress: a systematic literature review

- Open access

- Published: 13 December 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Tim Rademaker ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4709-0237 1 ,

- Ingo Klingenberg ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8693-4140 1 &

- Stefan Süß ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7454-4092 1

4551 Accesses

6 Citations

Explore all metrics

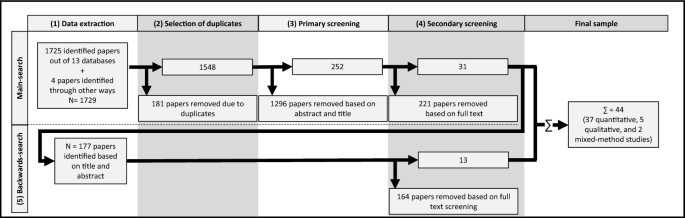

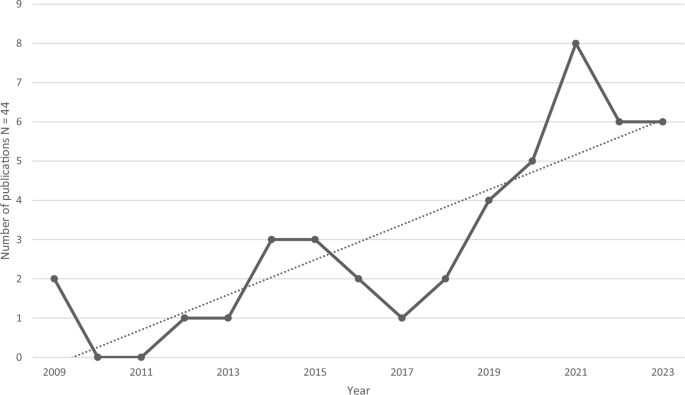

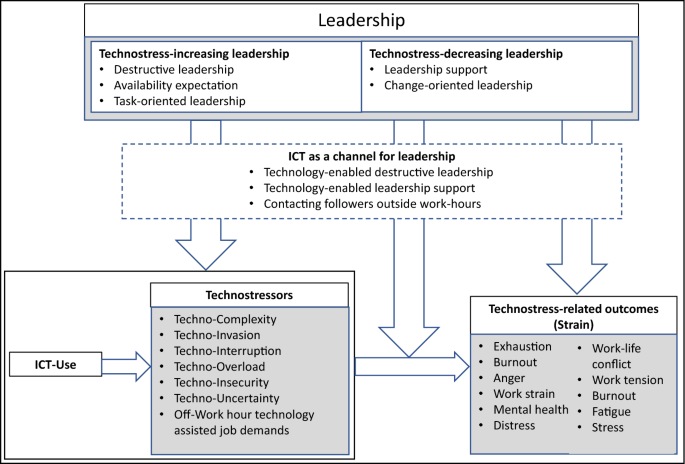

With the growing use of digital technologies at work, employees are facing new demands. Digital technologies are also changing how leaders and followers interact. Leadership must adapt to these changes and find ways to reduce the demands of digital work for their followers so they maintain their capacity for and motivation to work. Against this background, we analyze the impact leadership has on technostress by conducting a systematic literature review. An electronic search was based on 13 databases (ACM Digital, AIS eLibrary, APA PsychInfo, EBSCO, Emerald Insight, Jstor, Pubmed, SAGE, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Taylor & Francis Online, WISO, and Web of Science) and was carried out in October 2023. We identified 1725 articles—31 of which met the selection criteria. Thirteen more were identified in a backward search, leaving 44 articles for analysis. The conceptual analysis reveals that empowering and supportive leadership can decrease follower technostress. Leadership that emphasizes high availability expectations, task orientation and control can increase technostress and technostress-related outcomes. Furthermore, leadership’s impact on follower technostress is influenced by how ICTs are being used to convey leadership. We synthesize seven analytical themes of leadership among the technostress literature and derive them into the three aggregated dimensions which serve as the foundation of a conceptual model of leadership’s impact on follower technostress: technostress-increasing leadership, technostress-decreasing leadership, and technology-enabled leadership. Furthermore, we formulate avenues for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Identifying and Overcoming Future Challenges in Leadership: The Role of IS in Facilitating Empowerment

The Validity and Reliability of the Measure for Digital Leadership: Turkish Form

A systematic review and meta-analysis: leadership and interactional justice

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Work is constantly changing, but there are some technological developments that have groundbreaking effects on work, like the steam engine or the assembly line. Information and communication technologies (ICTs) can join the ranks of these technologies when it comes to changing work (e.g., Kamarul Bahrin et al. 2016 ). Like the other technologies, the digital penetration of the workplace bears great potential for improvement of work, as the use of ICTs can enhance productivity and flexibility with an increasing number of tasks that had been done offline moving to the digital sphere (Schmidtner et al. 2021 ; Vargo et al. 2021 ). However, digitalization also poses risks for employees, including increased strain by blurring boundaries between the work sphere and private life or by overwhelming employees with the inherent complexity of digital technology (Ragu-Nathan et al. 2008 ). The mechanisms of strain triggered by digital technology—often termed technostress —can have a significant impact on employees’ health, as technostress is associated with emotional exhaustion (Brown et al. 2014 ; Kim et al. 2015 ; Turel and Gaudioso 2018 ), burnout (Leung 2011 ; Srivastava et al. 2015 ), and depression (Torales et al. 2022 ). Besides workers’ health, work-related factors like productivity (Tarafdar et al. 2007 , 2011 ), commitment and engagement (Ragu-Nathan et al. 2008 ; Srivastava et al. 2015 ), and job satisfaction (Ragu-Nathan et al. 2008 ; Suh and Lee 2017 ) can be negatively affected by technostress.

Researchers ascribe leadership—understood here as “a process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal” (Northouse 2019 )—an increasingly important role in the context of digitalization (Cortellazzo et al. 2019 ) and technostress (Fischer and Riedl 2017 ; Salazar-Concha et al. 2021 ). According to Cortellazzo et al. ( 2019 ), leaders take an active part in the digitalization by supporting and motivating followers, who face challenges like the ongoing requirement to learn how to use new technologies. Leadership itself is also affected by digital technologies. As teams become locally decentralized and increasing amounts of work are done outside the traditional office environment, ICTs influence the interactions between leaders and followers. Leaders should adapt to these changes to be able to lead their followers through the ongoing change process related to digitalization and maintain their capacity for and motivation to work (Cortellazzo et al. 2019 ). Not incidentally, in view of the potential impact of technostress on employees’ health, health management has also become an important part of successful leadership (Schwarzmüller et al. 2018 ).