Search form (GSE) 1

The psychology of emotional and cognitive empathy.

The study of empathy is an ongoing area of major interest for psychologists and neuroscientists in many fields, with new research appearing regularly.

Empathy is a broad concept that refers to the cognitive and emotional reactions of an individual to the observed experiences of another. Having empathy increases the likelihood of helping others and showing compassion. “Empathy is a building block of morality—for people to follow the Golden Rule, it helps if they can put themselves in someone else’s shoes,” according to the Greater Good Science Center , a research institute that studies the psychology, sociology, and neuroscience of well-being. “It is also a key ingredient of successful relationships because it helps us understand the perspectives, needs, and intentions of others.”

Though they may seem similar, there is a clear distinction between empathy and sympathy. According to Hodges and Myers in the Encyclopedia of Social Psychology , “Empathy is often defined as understanding another person’s experience by imagining oneself in that other person’s situation: One understands the other person’s experience as if it were being experienced by the self, but without the self actually experiencing it. A distinction is maintained between self and other. Sympathy, in contrast, involves the experience of being moved by, or responding in tune with, another person.”

Emotional and Cognitive Empathy

Researchers distinguish between two types of empathy. Especially in social psychology, empathy can be categorized as an emotional or cognitive response. Emotional empathy consists of three separate components, Hodges and Myers say. “The first is feeling the same emotion as another person … The second component, personal distress, refers to one’s own feelings of distress in response to perceiving another’s plight … The third emotional component, feeling compassion for another person, is the one most frequently associated with the study of empathy in psychology,” they explain.

It is important to note that feelings of distress associated with emotional empathy don’t necessarily mirror the emotions of the other person. Hodges and Myers note that, while empathetic people feel distress when someone falls, they aren’t in the same physical pain. This type of empathy is especially relevant when it comes to discussions of compassionate human behavior. There is a positive correlation between feeling empathic concern and being willing to help others. “Many of the most noble examples of human behavior, including aiding strangers and stigmatized people, are thought to have empathic roots,” according to Hodges and Myers. Debate remains concerning whether the impulse to help is based in altruism or self-interest.

The second type of empathy is cognitive empathy. This refers to how well an individual can perceive and understand the emotions of another. Cognitive empathy, also known as empathic accuracy, involves “having more complete and accurate knowledge about the contents of another person’s mind, including how the person feels,” Hodges and Myers say. Cognitive empathy is more like a skill: Humans learn to recognize and understand others’ emotional state as a way to process emotions and behavior. While it’s not clear exactly how humans experience empathy, there is a growing body of research on the topic.

How Do We Empathize?

Experts in the field of social neuroscience have developed two theories in an attempt to gain a better understanding of empathy. The first, Simulation Theory, “proposes that empathy is possible because when we see another person experiencing an emotion, we ‘simulate’ or represent that same emotion in ourselves so we can know firsthand what it feels like,” according to Psychology Today .

There is a biological component to this theory as well. Scientists have discovered preliminary evidence of “mirror neurons” that fire when humans observe and experience emotion. There are also “parts of the brain in the medial prefrontal cortex (responsible for higher-level kinds of thought) that show overlap of activation for both self-focused and other-focused thoughts and judgments,” the same article explains.

Some experts believe the other scientific explanation of empathy is in complete opposition to Simulation Theory. It’s Theory of Mind, the ability to “understand what another person is thinking and feeling based on rules for how one should think or feel,” Psychology Today says. This theory suggests that humans can use cognitive thought processes to explain the mental state of others. By developing theories about human behavior, individuals can predict or explain others’ actions, according to this theory.

While there is no clear consensus, it’s likely that empathy involves multiple processes that incorporate both automatic, emotional responses and learned conceptual reasoning. Depending on context and situation, one or both empathetic responses may be triggered.

Cultivating Empathy

Empathy seems to arise over time as part of human development, and it also has roots in evolution. In fact, “Elementary forms of empathy have been observed in our primate relatives, in dogs, and even in rats,” the Greater Good Science Center says. From a developmental perspective, humans begin exhibiting signs of empathy in social interactions during the second and third years of life. According to Jean Decety’s article “The Neurodevelopment of Empathy in Humans ,” “There is compelling evidence that prosocial behaviors such as altruistic helping emerge early in childhood. Infants as young as 12 months of age begin to comfort victims of distress, and 14- to 18-month-old children display spontaneous, unrewarded helping behaviors.”

While both environmental and genetic influences shape a person’s ability to empathize, we tend to have the same level of empathy throughout our lives, with no age-related decline. According to “Empathy Across the Adult Lifespan: Longitudinal and Experience-Sampling Findings,” “Independent of age, empathy was associated with a positive well-being and interaction profile .”

And it’s true that we likely feel empathy due to evolutionary advantage : “Empathy probably evolved in the context of the parental care that characterizes all mammals. Signaling their state through smiling and crying, human infants urge their caregiver to take action … females who responded to their offspring’s needs out-reproduced those who were cold and distant,” according to the Greater Good Science Center. This may explain gender differences in human empathy.

This suggests we have a natural predisposition to developing empathy. However, social and cultural factors strongly influence where, how, and to whom it is expressed. Empathy is something we develop over time and in relationship to our social environment, finally becoming “such a complex response that it is hard to recognize its origin in simpler responses, such as body mimicry and emotional contagion,” the same source says.

Psychology and Empathy

In the field of psychology, empathy is a central concept. From a mental health perspective, those who have high levels of empathy are more likely to function well in society, reporting “larger social circles and more satisfying relationships,” according to Good Therapy , an online association of mental health professionals. Empathy is vital in building successful interpersonal relationships of all types, in the family unit, workplace, and beyond. Lack of empathy, therefore, is one indication of conditions like antisocial personality disorder and narcissistic personality disorder. In addition, for mental health professionals such as therapists, having empathy for clients is an important part of successful treatment. “Therapists who are highly empathetic can help people in treatment face past experiences and obtain a greater understanding of both the experience and feelings surrounding it,” Good Therapy explains.

Exploring Empathy

Empathy plays a crucial role in human, social, and psychological interaction during all stages of life. Consequently, the study of empathy is an ongoing area of major interest for psychologists and neuroscientists in many fields, with new research appearing regularly. Lesley University’s online bachelor’s degree in Psychology gives students the opportunity to study the field of human interaction within the broader spectrum of psychology.

Related Articles & Stories

Read more about our students, faculty, and alumni.

6 Critical Skills for Counselors

Janet Echelman ’97

Becoming a champion for the deaf community.

6 Ways Educators Can Prevent Bullying

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Neurodevelopment of Empathy in Humans

Jean decety.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

*Jean Decety, Center for Cognitive and Social Neuroscience, Departments of Psychology and Psychiatry, University of Chicago, 5848 South University Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637 (USA), E-Mail [email protected]

Received 2010 Mar 22; Accepted 2010 Jun 14; Issue date 2010 Dec.

Empathy, which implies a shared interpersonal experience, is implicated in many aspects of social cognition, notably prosocial behavior, morality and the regulation of aggression. The purpose of this paper is to critically examine the current knowledge in developmental and affective neuroscience with an emphasis on the perception of pain in others. It will be argued that human empathy involves several components: affective arousal, emotion understanding and emotion regulation, each with different developmental trajectories. These components are implemented by a complex network of distributed, often recursively connected, interacting neural regions including the superior temporal sulcus, insula, medial and orbitofrontal cortices, amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex, as well as autonomic and neuroendocrine processes implicated in social behaviors and emotional states. Decomposing the construct of empathy into subcomponents that operate in conjunction in the healthy brain and examining their developmental trajectory provides added value to our current approaches to understanding human development. It can also benefit our understanding of both typical and atypical development.

Key Words: Affective neuroscience, Amygdala, Empathy, Theory of mind, Neurodevelopment, Orbitofrontal cortex, Ventromedial prefrontal cortex

Introduction

Among the psychological processes that are the basis for much of social perception and smooth social interaction, empathy plays a key role. Empathy-related responding, including caring and sympathetic concern, is thought to motivate prosocial behavior, inhibit aggression and pave the way to moral reasoning [ Eisenberg and Eggum, 2009 ]. On the other hand, children suffering from certain developmental disorders such as conduct disorder and disruptive behavior disorders are considered to have little empathy and concern for the feelings and wellbeing of others, as well as a lack of remorse and guilt, all of which are regarded as risk factors in developing hostile, aggressive or even violent behavior [ de Wied et al., 2006 ].

This paper critically examines our current knowledge about the development of the mechanisms that support the experience of empathy and associated behavioral responses such as sympathy in the human brain. I begin by clarifying some definitional issues of empathy and associated phenomena. Next I address the neurodevelopment of empathy in relation to a model that distinguishes (a) bottom-up processing of affective communication, (b) emotion understanding, (c) top-down reappraisal processing in which the perceiver's motivation, intentions and attitudes moderate the extent of an empathic experience, and (d) an awareness of a self-other differentiation. I argue that studying subcomponents of more complex sociopsychological constructs like empathy can be particularly useful from a neurodevelopmental perspective when only some of its components or precursors may be observable. Developmental studies provide unique opportunities to see how the components of the system interact in ways that are not possible in adults when all the components are fully mature and operational [ de Haan and Gunnar, 2009 ]. Until quite recently, research on the development of empathy-related responding from a neurobiological level of analysis has been relatively sparse. Integrating this neuroperspective with behavioral work can shed light upon the neurobiological mechanisms underpinning the basic building blocks of empathy and sympathy and their age-related functional changes. Such integration can help us understand the neural processes that underpin prosocial behavior and can also benefit interventions in individuals with atypical development such as antisocial behavior problems.

Clearing Up Definitional Issues

The term empathy is applied to various phenomena which cover a broad spectrum ranging from feelings of concern for other people that create a motivation to help them, experiencing emotions that match another individual's emotions, knowing what the other is thinking or feeling, to blurring the line between self and other [ Hodges and Klein, 2001 ]. In developmental psychology, empathy is generally defined as an affective response stemming from the understanding of another's emotional state or condition similar to what the other person is feeling or would be expected to feel in the given situation [ Eisenberg et al., 1991 ]. Very often, empathy and sympathy are conflated. Here, I distinguish between empathy, simply defined as the ability to recognize the emotions and feelings of others with a minimal distinction between self and other, and sympathy, i.e. feelings of concern about the welfare of others. While empathy and sympathy are often confused, the two can be dissociated, and although sympathy may stem from the apprehension of another's emotional state, it does not have to be congruent with the affective state of the other. The experience of empathy can lead to sympathy (which includes an other-oriented motivation) or personal distress, an egoistic motivation to reduce stress by withdrawing from the stressor, thereby decreasing the likelihood of prosocial behavior (table 1 ).

Key concepts associated with the construct of empathy

OFC = Orbitofrontal cortex; mPFC = medial prefrontal cortex; vmPFC = ventromedial prefrontal cortex.

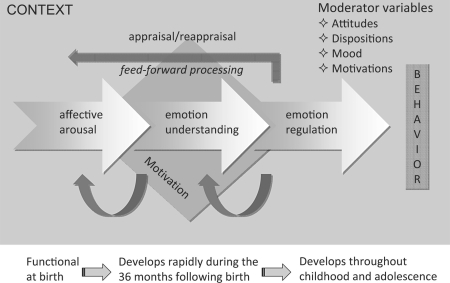

Given the complexity of what encompasses the phenomenological experience of empathy, investigation of its neurobiological underpinnings would be worthless without breaking down this construct into component processes (fig. 1 ). In spite of reports in the popular press that give the appealing, yet wrong, notion that the organization of psychological phenomena maps in a 1:1 fashion into the organization of the underlying neural substrate, in reality, empathy, like other social cognitive processes, draws on a large array of brain structures and systems which are not limited to the cortex but also include subcortical pathways, the autonomic nervous system, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and endocrine systems that regulate bodily states, emotion and reactivity [ Carter et al., 2009 ]. Moreover, sympathy (or empathic concern) has multiple antecedents within and across levels of organization, and a comprehensive social neuroscience theory of empathy requires the specification of various causal mechanisms producing some outcome variable (e.g. helping behavior), the moderator variables (e.g. implicit attitudes, ingroup/outgroup processes) that influence the conditions under which each of these mechanisms operate, and the unique consequences resulting from each of them.

Schematic illustration of the macrocomponents involved in human empathy. These different components are intertwined and contribute to different aspects of the experience of empathy. They can be dissociated by brain lesions. Affective arousal: first component in place in development having evolved to differentiate hostile from hospitable stimuli and to organize adaptive responses to these stimuli. This component refers to the automatic discrimination of a stimulus – or features of a stimulus – as appetitive or aversive, hostile or hospitable, pleasant or unpleasant, threatening or nurturing. Subcortical circuits including the amygdala, hypothalamus, hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) are the essential neural components of affective arousal. The amygdala and OFC with reciprocal connection with the superior temporal sulcus (STS) underlie rapid and prioritized processing of the emotion signal. Emotion understanding: develops later, and begins to be really mature around the age of 2–3 years. This component largely overlaps with theory-of-mind-like processing and draws on the ventromedial (vm) and medial (m) prefrontal cortex (PFC) as well as executive functions. The latter allow the child to entertain several perspectives and a decoupling mechanism between first-person and second-person information. Emotion regulation: enables the control of emotion, affect, drive and motivation. This component develops throughout childhood and adolescence, and parallels the maturation of execution functions. The dorsolateral PFC, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and the vmPFC, via their reciprocal connections with the amygdala and widespread cortical areas including the STS, play a primary role in self-regulation. Humans also have the capacity to appraise and reappraise emotions and feelings. Thus, empathy is not a passive affective resonance phenomenon with the emotions of others. Rather, goals, intentions, context and motivations play feed-forward roles in how emotions are perceived and experienced. From this model, it is clear that empathy is implemented by a complex network of distributed, often recursively connected, interacting neural regions (STS, insula, mPFC and vmPFC, amygdala and ACC) as well as autonomic and neuroendocrine processes implicated in social behaviors and emotional states.

Empathy is not unique to humans as many of the physiological mechanisms are shared with other mammalian species. Recognizing and evaluating signals of distress from newborns and infants is of primary importance in parental care for offspring survival and fitness. The thalamocingulate division of the forebrain is believed to have evolved in parallel with social behaviors related to the perception of emotional information involved in securing emotional bonding and social interactions [ MacLean, 1987 ]. However, humans are special in the sense that high-level cognitive abilities such as executive function, language and theory of mind (ToM) are layered on top of phylogenetically older social and emotional capacities. These evolutionarily newer aspects of information processing expand the range of behaviors that can be driven by empathy (like caring for and helping outgroup members or even individuals from different species).

Recent affective neuroscience research with children and adult participants indicates that the affective, cognitive and regulatory aspects of empathy involve interacting, yet partially nonoverlapping, neural circuits. Furthermore, there is now evidence for age-related changes in these neural circuits which, together with behavioral measures, reflect how brain maturation influences reactions to the distress of others [ Decety and Michalska, 2010 ].

The Neurodevelopment of Empathy

Empathy typically emerges as the child comes to a greater awareness of the experience of others, during the second and third years of life, and arises in the context of a social interaction. Each of the components of empathy (affective arousal, emotion understanding and emotion regulation) will be considered separately from both developmental and neuroscientific perspectives. These components are indeed dissociable, as documented in studies with neurological patients [ Decety, 2010 ; Strum et al., 2006 ], yet mature empathic sensitivity and concern depend on their functional integration in the service of goal-directed social behavior. There is compelling evidence that prosocial behaviors such as altruistic helping emerge early in childhood. Infants as young as 12 months of age begin to comfort victims of distress, and 14- to 18-month-old children display spontaneous, unrewarded helping behaviors [ Warneken and Tomasello, 2009 ]. In addition, both genetic and environmental factors contribute to the development of empathy and prosociality [ Knafo et al., 2008 ].

Most scholars agree that empathy includes both cognitive and affective components [ Decety and Jackson, 2004 ; Eisenberg and Eggum, 2009 ; Hodges and Klein, 2001 ] that have different developmental trajectories. Based on both theories and empirical evidence from affective neuroscience and developmental psychology, one may propose a model that includes bottom-up processing of affective sharing and top-down processing in which the perceiver's motivation, intentions and attitudes influence the extent of an empathic experience, and the likelihood of prosocial behavior [ Decety, 2005 ; Decety and Meyer, 2008 ]. In that model, a number of distinct and interacting neurocognitive components contribute to the experience of empathy: (1) affective arousal, a bottom-up process in which the amygdala, hypothalamus and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) underlie rapid and prioritized processing of the emotion signal; (2) emotion understanding, which relies on self- and other-awareness and involves the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), ventromedial (vm)PFC and temporoparietal junction (TPJ), and (3) emotion regulation, which depends on executive functions instantiated in the intrinsic corticocortical connections of the OFC, mPFC and dorsolateral (dl)PFC, as well as on connections with subcortical limbic structures implicated in processing emotional information. These networks operate as top-down mediators crucial in regulating emotions and thereby enhancing flexible and appropriate responses.

Affective Arousal

There is ample behavioral evidence demonstrating that the affective component of empathy develops earlier than the cognitive components. Prior to the onset of language, the primary means by which infants can communicate with others in their environment is by reading faces [ Leppanen and Nelson, 2009 ]. Thus, it is important for an infant not only to discriminate familiar from unfamiliar individuals, but also to derive information about the individual's feelings and intentions, for example, whether the caregiver is pleased or displeased, afraid or angry [ Ludemann and Nelson, 1988 ]. Affective responsiveness is known to be present at an early age, is involuntary, and relies on mimicry and somatosensorimotor resonance between other and self. For instance, newborns and infants become vigorously distressed shortly after another infant begins to cry [ Dondi et al., 1999 ]. Discrete facial expressions of emotion have been identified in newborns, including joy, interest, disgust and distress [ Izard, 1982 ], suggesting that subcomponents of emotional experience and expression are present at birth, and supporting the possibility that these processes are hard-wired in the brain. Human newborns by 10 weeks of age are capable of imitating expression of fear, sadness, and surprise [ Haviland and Lewica, 1987 ], preparing the individual for later empathic connections through affective interaction with others. This resonance may be partly based on the mirror neuron system (MNS), which – from electroencephalographic (EEG) studies – seems to be already functioning in infants as young as 6 months [ Nyström, 2008 ]. One fMRI study directly examined the relationship between MNS activity and two distinct indicators of social functioning in typically developing 10-year-olds: empathy and interpersonal competence [ Pfeifer et al., 2008 ]. Reliable activity in the inferior frontal gyrus was associated with both observation and imitation of emotional expressions. Importantly, activity in this region was significantly and positively correlated with behavioral measures, indexing the empathic behavior of children. But see a critical appraisal of the contribution of the MNS to empathy in Decety [2010 ].

Together, these findings indicate that, very early on, infants are able to perceive and respond to another's affective state. This automatic emotional resonance between other and self relies on a tight coupling between perceptual processing and emotion-related neural circuits. Infant arousal in response to the affects signaled by others can serve as an instrument for social learning, reinforcing the significance of the social exchange, which then becomes associated with the infant's own emotional experience. Consequently, infants come to experience emotions as shared states and learn to differentiate their own states partly by witnessing the resonant responses that they elicit in others [ Nielsen, 2002 ].

Emotion Understanding

While the capacity for two people to resonate with each other affectively, prior to any cognitive understanding, is the basis for developing shared emotional meanings, it is not enough for mature empathic understanding. Such an understanding requires the formation of an explicit representation of the feelings of another person as an intentional agent, which necessitates additional computational mechanisms beyond the affect sharing level [ Decety et al., 2008 ]. The cognitive components that give way to empathic understanding have a more protracted course of development than the affective components, even though many precursors are already in place very early in life.

An experience of emotion is a state of mind the content of which is at once affective (pleasant or unpleasant) and conceptual (a representation of the individual relation to the surrounding world) [ Barrett et al., 2007 ]. Emotion is also, however, an interpersonal communication system that elicits response from others. Thus, emotions can be viewed both as intrapersonal and interpersonal states, and the construct of empathy entails both such dimensions.

A number of studies have shown that the reliable perception of facial expressions, such as attention to configural rather than featural information in faces and the ability to recognize facial expressions across variations in identity or intensity, are not present until the age of 5–7 months [ Haviland and Lewica, 1987 ]. Some questions remain as to whether these early reactions represent recognition of emotion in another or simple mimicry, but by 2 years of age, most children use emotion labels for facial expressions and talk about emotion topics [ Gross and Ballif, 1991 ]. Recent work has documented that even very young children (18–25 months old) can sympathize with a victim even in the absence of overt emotion cues [ Vaish et al., 2009 ], which suggests that some early form of affective perspective taking that does not rely on emotion contagion or mimicry is present. Regarding the causes and effects of emotion and the cues used in inferring emotion, developmental research has detailed a progression from situation-bound, behavioral explanations of emotion to broader, more mentalistic understandings [ Harris et al., 1981 ]. As children develop, their emotional inferences contain a more complex and differentiated use of several types of information, such as relational and contextual factors and the goals or beliefs of the target child [ Harris, 1994 ]. This development appears to be somewhat slower for complex social emotions like pride, shame or embarrassment [ Lewis, 2000 ]. Development of this understanding proceeds from lack of acknowledgement of multiple emotions in younger children, to acknowledgement of different variables such as emotion valence and emotion intensity [ Carroll and Steward, 1984 ].

With cognitive empathy, the individual is thought to use perspective-taking processes to imagine or project into the place of the other in order to understand what she/he is feeling. These cognitive aspects of empathy are closely related to processes involved in ToM, executive function and self-regulation. There is growing evidence documenting that executive function and ToM are fundamentally linked in development and their relationship is stable [ Carlson et al., 2004 ]. Several studies have shown that, by around 4 years of age, children can understand that the emotion a person feels about a given event depends upon that person's perception of the event and their beliefs and desires about it. Notably, a longitudinal study of children aged 47–60 months examined developmental changes in understanding of false belief and emotion, as well as mental-state conversation with friends [ Hughes and Dunn, 1998 ]. They found that individual differences in understanding of both false belief and emotion were stable over this time period and were significantly related to each other. Emotion recognition continues to develop into later adolescence [ Tonks et al., 2007 ], and this improves social cognition performance as well.

ToM is layered on top of affective processes and its development depends on the forging of connections between brain circuits for domain-general cognition and circuits specialized for aspects of social understanding. Neuroimaging studies have identified a circumscribed neural network reliably underpinning the understanding of mental states (self and other) that links the mPFC with the posterior superior temporal sulcus at the TPJ [ Brunet et al., 2000 ]. These regions were activated in children aged 6–11 years while they were listening to sections of a story describing a character's thoughts compared to sections of the same story that described the physical context [ Saxe et al., 2009 ]. Further, change in response selectivity with age was observed in the right TPJ, which was recruited equally for mental and physical facts about people in younger children, but only for mental facts in older children. Results from a study with 4-year-old children showed that individual differences in EEG alpha activity localized to the dorsal mPFC and the right TPJ were positively associated with children's ToM performance, which suggests that the maturation of the dorsal mPFC and right TPJ is a critical constituent of the explicit ToM development of preschoolers [ Sabbagh et al., 2009 ]. Support for age-related changes in brain activity associated with metacognition is also provided by an fMRI investigation of ToM in participants whose age ranged between 9 and 16 years [ Moriguchi et al., 2007 ]. Both children and adolescents demonstrated significant activation in the neural circuits associated with mentalizing tasks, including the TPJ, the temporal poles and mPFC. Furthermore, the authors found a positive correlation between age and degree of activation in the dorsal part of the mPFC. Direct evidence for the implication of these regions in the accurate identification of interpersonal emotional states has recently been documented in a study in which adult participants were requested to rate how they believed target persons felt while talking about autobiographical emotional events [ Zaki et al., 2009 ].

In sum, the neural circuits implicated in emotion understanding partly overlap with those involved in ToM processing, especially the mPFC and right TPJ, and they still undergo maturation until late adolescence.

Emotion Regulation

The regulation of emotion is the ability to respond to the ongoing demands of experience with a range of emotions in a manner that is socially tolerable and sufficiently flexible to permit spontaneous reactions, including the ability to delay spontaneous reactions as needed [ Fox, 1994 ]. Difficulty in the ability to regulate emotions can result in deleterious emotional arousal, thereby hindering the ability to socially function adaptively and appropriately.

Developmental changes in emotion regulation are demonstrated as the infant progresses from almost total dependence on caregivers for regulation of emotion states to independent self-regulation of emotions. Early emotion regulation is mainly influenced by innate physiological mechanisms, and around 3 months of age, some voluntary control of arousal is evident, with more purposeful control evident by 12 months when developing motor skills and communication behaviors [ Bell and Wolfe, 2007 ]. Empathic concern is strongly related to effortful control, with children high in effortful control showing greater empathic concern [ Rothbart et al., 1994 ], as indicated by a number of developmental studies which reported that individual differences in the tendency to experience sympathy versus personal distress vary as a function of dispositional differences in the abilities of individuals to regulate their emotions. Well-regulated children who have control over their ability to focus and shift attention have been found to be relatively prone to sympathy, regardless of their emotional reactivity. This is because they can modulate their negative vicarious emotion to maintain an optimal level of emotional arousal. In contrast, children who are unable to regulate their emotions, especially if they are dispositionally prone to intense negative emotions, are found to be low in dispositional sympathy and prone to personal distress [ Eisenberg and Eggum, 2009 ].

Interestingly, the development of emotion regulation is functionally linked to the development of executive functions and metacognition. Indeed, improvement in inhibitory control corresponds with increasing metacognitive capacities [ Zelazo et al., 2004 ], as well as with maturation of brain regions which underlie working memory and inhibitory control [ Tamm et al., 2002 ]. The regions of the PFC that are most consistently involved in emotion regulation include the ventral and dorsal aspects of the PFC, as well as the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) [ Ochsner et al., 2002 ]. In primates, these regions comprise a mixture of dysgranular, granular and agranular cortical areas. Ventromedial areas of the PFC develop relatively early and are involved especially in the control of emotional behaviors, whereas lateral prefrontal cortical regions develop late, and are principally involved in higher executive functions [ Philips et al., 2008 ]. The PFC and its functions follow an extremely protracted developmental course, and age-related changes continue well into adolescence [ Bunge et al., 2002 ; Casey et al., 2005 ]. Frontal lobe maturation is associated with an increase in the ability of a child to activate areas involved in emotional control and to exercise inhibitory control over their thoughts, attention and action. The maturation of the PFC also allows children to use verbalizations to achieve self-regulation of their feelings [ Diamond, 2002 ]. It is therefore likely that different parts of the brain may be differentially involved in empathy at different ages. For example, Killgore and Yurgelun-Todd [2007 ] provided evidence that as a child matures into adolescence, there is a shift in response to emotional events from using more limbic-related anatomic structures such as the amygdala to using more frontal lobe regions to control emotional responses. Thus, not only may there be less neural activity related to the regulation of cognition and emotion in younger individuals, but the neural pattern itself is likely to differ.

Developmental studies conducted by Lewis et al. [2006 ] suggest that while young children, like adults, recruit cortical mechanisms of emotion regulation tapped by event-related potentials associated with effortful control and information processing, there are some important age-related changes. In one study with children 5–16 years of age, two event-related potential components associated with inhibitory control: the frontal N2 and frontal P3 were recorded before, during and after a negative emotion induction when engaged in a simple go/no-go procedure in which points for successful performance earned a valued prize. The temporary loss of all points triggered negative emotions, as confirmed by self-report scales. Both the frontal N2 and frontal P3 decreased in amplitude and latency with age, consistent with the hypothesis of increasing cortical efficiency. Amplitudes were also higher following the emotion induction, only in adolescents for the N2, but across the age span for the frontal P3, suggesting different but overlapping profiles of emotion-related control mechanisms. No-go N2 amplitudes were greater than go N2 amplitudes following the emotion induction at all ages, suggesting a consistent effect of negative emotion on mechanisms of response inhibition. No-go P3 amplitudes were also greater than go P3 amplitudes, and they decreased with age, whereas go P3 amplitudes remained low. Finally, source modeling indicated a developmental decline in central-posterior midline activity paralleled by increasing activity in ACC.

Measures of heart rate variability and its variations of respiratory sinus arrhythmia and vagal tone have been linked to emotional reactivity and regulation [ Bell and Wolfe, 2007 ]. Infants with higher heart rate variability are more emotionally expressive and reactive, and this reactivity produces distress and irritability [ Calkins and Fox, 2002 ]. As regulatory abilities develop, due to executive functions, the reactivity can lead to concentration when interest is paramount or to more expressive reactivity when other situations take precedent.

To sum up, regulating emotions is crucial in maintaining a connection with ongoing perceptual processes, having access to a greater number of adaptive responses and enhancing flexible and appropriate responses. Emotion regulation develops throughout early childhood and adolescence and parallels the maturation of executive functions. There is evidence indicating that inhibitory processes recruited for emotion regulation involve different prefrontal circuits and autonomic activity as children mature.

Perceiving Other People in Distress

The long history of mammalian evolution has shaped our brains to be sensitive to signs of suffering and distress in one's own offspring [ Haidt and Graham, 2007 ]. Pain warns of physical threat and danger on the one hand, and also signals an opportunity to care for and heal the person in pain on the other. A growing number of fMRI studies have demonstrated that the same neural circuit that is involved in the experience of physical pain is also involved in the perception or even the imagination of another individual in pain [ Jackson et al., 2006 ]. This neural network, which includes the supplementary motor area, dorsal ACC, anterior medial cingulate cortex, periaqueductal gray and insula [ Akitsuki and Decety, 2009 ; Lamm et al., 2007 ], underpins a physiological mechanism that mobilizes the organism to react, with heightened arousal and attention, to threatening situations [ Decety, 2010 ].

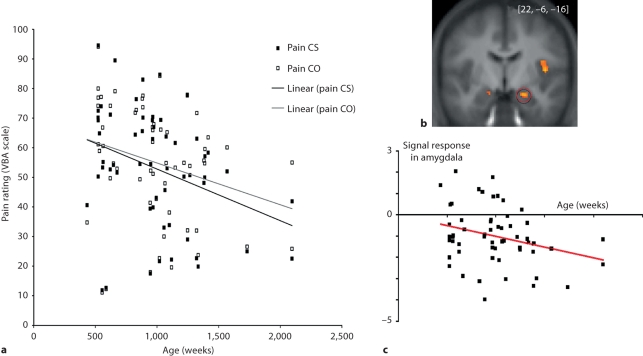

To examine developmental changes associated with empathy, Decety and Michalska [2010 ] collected fMRI and behavioral data from a group of 57 participants ranging from 7 to 40 years of age while they were exposed to short video clips depicting people accidentally in pain or intentionally harmed by another individual. Results at the whole-group level showed that attending to painful situations caused by accident was associated with activation of the pain matrix including the anterior medial cingulate cortex, insula, periaqueductal gray and somatosensory cortex. Interestingly, when watching one person intentionally inflicting pain onto another, regions that are consistently engaged in mental state understanding and affective evaluation (mPFC, TPJ and OFC) were also recruited. The younger the participants, the more strongly the amygdala, posterior insula and supplementary motor area were recruited when they watched painful, accidentally caused situations. While participants’ subjective ratings of the painful situations decreased with age and were significantly correlated with hemodynamic response in the mPFC, increases in pain ratings were correlated with bilateral amygdala activation (fig. 2 ).

a Subjective ratings of dynamic visual stimuli depicting painful situations accidentally caused by self (Pain CS) and painful situations intentionally caused by another individual (Pain CO) across age (in weeks) in 57 participants (from 7 to 40 years old). A gradual decrease in the subjective evaluation of pain intensity for both painful conditions was found across age, with younger participants rating them significantly higher than older participants (Pain CS: r = −0.327, p < 0.01; Pain CO: r = −0.267, p < 0.05). Further, while on average participants rated the pain caused intentionally (Pain CO) conditions as significantly more painful than when pain was accidentally caused by self (Pain CS; t 56 = 2.581; p < 0.01), this effect was not driven by age. b Bilateral amygdala activation. c Significant negative correlation between age and degree of activation in the amygdala when the participants are exposed to painful situations accidentally caused. Adapted from Decety and Michalska [2010 ].

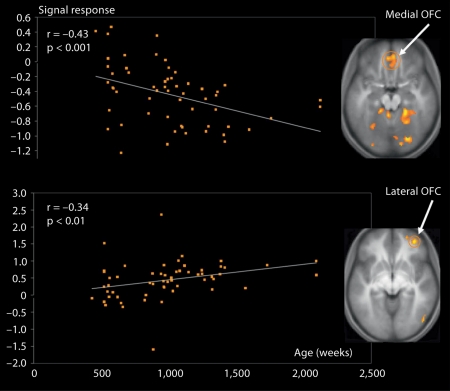

A significant negative correlation between age and degree of activation was found in the posterior insula. In contrast, a positive correlation was found in the anterior portion of the insula. This posterior-to-anterior progression of increasingly complex re-representations in the human insula is thought to provide a foundation for the sequential integration of the individual homeostatic condition with one's sensory environment and motivational condition [ Craig, 2004 ]. The posterior insula receives inputs from the ventromedial nucleus of the thalamus, which is highly specialized for conveying emotional and homeostatic information such as pain, temperature, hunger, thirst, itch and cardiorespiratory activity. It serves as a primary sensory cortex for each of these distinct interoceptive feelings from the body. The posterior part has been shown to be associated with interoception due to its intimate connections with the amygdala, hypothalamus, ACC and OFC [ Jackson et al., 2006 ]. It has been proposed that the right anterior insula serves to compute a higher-order metarepresentation of the primary interoceptive activity, which is related to the feeling of pain and its emotional awareness [ Craig, 2003 ]. In line with evidence that regulatory mechanisms continue into late adolescence and early adulthood, greater signal change with increasing age was found in the prefrontal regions involved in cognitive control and response inhibition, such as the dlPFC and inferior frontal gyrus [ Swick et al., 2008 ]. Overall, this pattern of age-related change in the amygdala, insula and PFC can be interpreted in terms of the frontalization of inhibitory capacity, hypothesized to provide a greater top-down modulation of activity within more primitive emotion-processing regions [ Yurgelun-Todd, 2007 ]. Another important age-related change was detected in the vmPFC/OFC: activation in the OFC in response to pain inflicted by another shifted from its medial portion in young participants to the lateral portion in older participants (fig. 3 ).

Shift in activation in the vmPFC across age when participants aged from 7 to 40 years are watching another person being intentionally hurt by another. A significant negative correlation (r = −43; p < 0.001) between age and degree of activation was detected in the medial portion of the OFC (x = 10, y = 50, z = −2), while a significant positive correlation (r = 0.34; p < 0.01) was noted in the lateral portion of the OFC (x = 38, y = 48, z = −8). Adapted from Decety and Michalska [2010 ].

The medial OFC appears integral to guiding visceral and motor responses, whereas the lateral OFC integrates the external sensory features of a stimulus with its impact on the homeostatic state of the body. The pattern of developmental change in the OFC seems to reflect a gradual shift between the monitoring of somatovisceral responses in young children, mediated by the medial aspect of the OFC, and the executive control of emotion processing implemented by its lateral portion in older participants. These data support the suggestion that the vmPFC contains two feedback-processing systems, consistent with hypotheses derived from anatomical studies [ Hurliman et al., 2005 ]. One subsystem, situated laterally in the OFC, preferentially processes information from the external environment; the other subsystem, situated medially, preferentially processes interoceptive information such as visceromotor output critical for the analysis of the affective significance of stimuli.

In sum, the behavioral evaluations of others in distress combined with the pattern of brain activation from childhood to adulthood reflect a gradual change from a visceral emotional response critical for the analysis of the affective significance of stimuli to a more evaluative function mediated by different aspects of the vmPFC and its reciprocal connections with the amygdala.

Given the importance of empathy for healthy psychological and social interaction, it is clear that a neurodevelopmental approach to elucidate the computational mechanisms underlying affective reactivity, emotion understanding and regulation is essential to complement traditional behavioral methods and gain a better understanding of how deficits may arise in the context of development. Breaking down empathy and related phenomena into components and examining their neurodevelopment can contribute to a more complete model of interpersonal sensitivity. Likewise, drawing from multiple sources of data can improve our understanding of the nature and causes of empathy deficits in individuals with antisocial behavior disorders. Recent advances in cognitive and affective neuroscience indicate that distinct but interacting brain circuits underpin the different components of empathy, each having their own developmental trajectory.

Humans are born with the neural circuitry that implements core affect (that can be described by hedonic valence and arousal), and binds sensory and somatovisceral information to create a meaningful representation that can be used to safely navigate the world [ Duncan and Barrett, 2007 ]. Gradually, the ability to apprehend the emotional states of others increases with age in terms of decoding confounded emotions, interpreting situational regulators of affect and understanding ‘unexpressed’ affect – the intensity of emotional reactions to the affect of others –, and may asymptote at a relatively young age and have a significant biological contribution, particularly relying on reciprocal connections between the vmPFC, ACC and amygdala. Part of the developmental process may consist of acquiring more elaborated empathy/sympathy complex behaviors – more occasions that evoke affect and buffer against such evocation – as well as better distancing, distracting, display and avoidance patterns [ More, 1990 ]. Empathic emotional response in the young child may be stronger, whereas sympathetic behavior may be less differentiated. With age and increased maturation of the mPFC, dlPFC and vmPFC, in conjunction with input from interpersonal experiences that are strongly modulated by various contextual and social factors such as ingroup versus outgroup processes, children and adolescents become sensitive to social norms regulating prosocial behavior and, accordingly, may become more selective in their response to others.

Developmental affective neuroscience is still a young discipline and much has to be learned beyond the mere correlations between structural, fMRI and developmental trajectories. Future research will greatly benefit from combining advances in imaging technologies (e.g. EEG, fMRI, diffusion tensor imaging, optical imaging), ecologically valid experimental paradigms, measures of hormonal levels, and genetics (too little is known about the impact of individual differences) for a more complete understanding of social cognition and a better grasp of neurodevelopmental disorders.

Acknowledgment

The writing of this paper was supported by a grant (BCS-0718480) from the National Science Foundation and a grant from the NIH/National Institute of Mental Health (MH84934-01A1).

- Akitsuki Y, Decety J. Social context and perceived agency modulate brain activity in the neural circuits underpinning empathy for pain: an event-related fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2009;47:722–734. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.04.091. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barrett LF, Mesquita B, Ochsner KN, Gross JJ. The experience of emotion. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:373–403. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085709. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bell MA, Wolfe CD. The cognitive neuroscience of early socioemotional development. In: Brownell CA, Kopp CB, editors. Socioemotional Development in Toddler Years. New York: Guilford; 2007. pp. 345–369. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brunet E, Sarfati Y, Hardy-Bayle MC, Decety J. A PET investigation of attribution of intentions to others with a non-verbal task. Neuroimage. 2000;11:157–166. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1999.0525. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bunge SA, Dudukovic NM, Thomasson ME, Vaidya CJ, Gabrieli JDE. Immature frontal lobe contributions to cognitive control in children: evidence from fMRI. Neuron. 2002;33:301–311. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00583-9. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Calkins SD, Fox NA. Self-regulatory processes in early personality development: a multilevel approach to the study of childhood social withdrawal and aggression. Dev Psychopathol. 2002;14:477–498. doi: 10.1017/s095457940200305x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carlson SM, Mandell DJ, Williams L. Executive function and theory of mind: stability and prediction from ages 2 to 3. Dev Psychol. 2004;40:1105–1122. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1105. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carroll JJ, Steward MS. The role of cognitive development in children's understandings of their own feelings. Dev Psychol. 1984;55:1486–1492. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter SS, Harris J, Porges SW. Neural and evolutionary perspectives on empathy. In: Decety J, Ickes W, editors. The Social Neuroscience of Empathy. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2009. pp. 169–182. [ Google Scholar ]

- Casey BJ, Tottenham N, Liston C, Durston S. Imaging the developing brain: what have we learned about cognitive development? Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.01.011. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Craig AD. Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:500–505. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00090-4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Craig AD. Human feelings: why are some more aware than others? Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8:239–241. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.04.004. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Decety J. Perspective taking as the royal avenue to empathy. In: Malle BF, Hodges SD, editors. Other Minds. How Humans Bridge the Divide between Self and Others. New York: Guilford; 2005. pp. 135–149. [ Google Scholar ]

- Decety J. To what extent is the experience of empathy mediated by shared neural circuits. Emot Rev. 2010;2:204–207. [ Google Scholar ]

- Decety J, Jackson PL. The functional architecture of human empathy. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev. 2004;3:71–100. doi: 10.1177/1534582304267187. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Decety J, Meyer M. From emotion resonance to empathic understanding: a social developmental neuroscience account. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20:1053–1080. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000503. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Decety J, Michalska KJ. Neurodevelopmental changes in the circuits underlying empathy and sympathy from childhood to adulthood. Dev Sci. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00940.x. E-pub ahead of print. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Decety J, Michalska KJ, Akitsuki Y. Who caused the pain? A functional MRI investigation of empathy and intentionality in children. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:2607–2614. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.05.026. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- de Haan M, Gunnar MR. The brain in a social environment: why study development? In: de Haan M, Gunnar MR, editors. Handbook of Developmental Social Neuroscience. New York: Guilford; 2009. pp. 3–10. [ Google Scholar ]

- de Wied M, van Boxtel A, Zaalberg R, Goudena PP, Matthys M. Facial EMG responses to dynamic emotional facial expressions in boys with disruptive behavior disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.08.003. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Diamond A. Normal development of prefrontal cortex from birth to young adulthood: cognitive functions, anatomy, and biochemistry. In: Stuss DT, Knight RT, editors. Principles of Frontal Lobe Function. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 446–503. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dondi M, Simion F, Caltran G. Can newborns discriminate between their own cry and the cry of another newborn infant? Dev Psychol. 1999;35:418–426. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.2.418. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Duncan S, Barrett LF. Affect is a form of cognition: a neurobiological analysis. Cogn Emot. 2007;21:1184–1211. doi: 10.1080/02699930701437931. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eisenberg N, Eggum ND. Empathic responding: sympathy and personal distress. In: Decety J, Ickes W, editors. The Social Neuroscience of Empathy. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2009. pp. 71–83. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eisenberg N, Shea CL, Carlo G, Knight GP. Empathy-related responding and cognition: a chicken and the egg dilemma. In: Kurtines WM, editor. Handbook of Moral Behavior and Development. vol 2. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 63–88. Research. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fox NA. The Development of Emotion Regulation. Biological and Behavioral Considerations. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1994;59 [ Google Scholar ]

- Gross AL, Ballif B. Children's understanding of emotion from facial expressions and situations: a review. Dev Rev. 1991;11:368–398. [ Google Scholar ]

- Haidt J, Graham J. When morality opposes justice: conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Soc Justice Res. 2007;20:98–116. [ Google Scholar ]

- Harris PL. The child's understanding of emotion: developmental change and the family environment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1994;35:3–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01131.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harris PL, Olthof T, Meerum-Terwogt M. Children's knowledge of emotion. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1981;22:247–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1981.tb00550.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haviland JM, Lewica M. The induced affect response: ten-week-old infants' responses to three emotion expressions. Dev Psychol. 1987;23:97–104. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hodges SD, Klein KJK. Regulating the costs of empathy: the price of being human. J Socio Econ. 2001;30:437–452. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hughes C, Dunn J. Understanding mind and emotion: longitudinal associations with mental state talk between young friends. Dev Psychol. 1998;34:1026–1037. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.1026. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hurliman E, Nagode JC, Pardo JV. Double dissociation of exteroceptive and interoceptive feedback systems in the orbital and ventromedial prefrontal cortex of humans. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4641–4648. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2563-04.2005. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Izard CE. Measuring Emotions in Infants and Young Children. New York: Cambridge Press; 1982. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jackson PL, Rainville P, Decety J. To what extent do we share the pain of others? Insight from the neural bases of pain empathy. Pain. 2006;125:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.013. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Killgore WDS, Yurgelun-Todd DA. Unconscious processing of facial affect in children and adolescents. Soc Neurosci. 2007;2:28–47. doi: 10.1080/17470910701214186. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Knafo A, Zahn-Waxler C, van Hulle C, Robinson JL, Rhee SH. The developmental origins of a disposition toward empathy: genetic and environmental contributions. Emotion. 2008;8:737–752. doi: 10.1037/a0014179. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lamm C, Batson CD, Decety J. The neural substrate of human empathy: effects of perspective-taking and cognitive appraisal. J Cogn Neurosci. 2007;19:42–58. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.1.42. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leppanen JM, Nelson CA. Tuning the developing brain to social signals of emotions. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:37–47. doi: 10.1038/nrn2554. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lewis M. Self-conscious emotions: embarrassment, pride, shame, and guilt. In: Lewis M, Haviland JM, editors. Handbook of Emotions. New York: Guilford; 2000. pp. 623–636. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lewis MD, Lamm C, Segalowitz SJ, Stieben J, Zelazo PD. Neurophysiological correlates of emotion regulation in children and adolescents. J Cogn Neurosci. 2006;18:430–443. doi: 10.1162/089892906775990633. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ludemann PM, Nelson CA. Categorical representation of facial expressions by 7-month-old infants. Dev Psychol. 1988;24:492–501. [ Google Scholar ]

- MacLean P. The midline frontal limbic cortex and the evolution of crying and laughter. In: Perecman E, editor. The Frontal Lobes Revisited. New York: IRBN; 1987. pp. 121–140. [ Google Scholar ]

- More BS. The origins and development of empathy. Motiv Emot. 1990;14:75–79. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moriguchi Y, Ohnishi T, Mori T, Matsuda H, Komaki G. Changes of brain activity in the neural substrates for theory of mind in childhood and adolescence. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61:355–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01687.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nielsen L. The simulation of emotion experience: on the emotional foundations of theory of mind. Phenomenol Cogn Sci. 2002;1:255–286. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nyström P. The infant mirror neuron system studied with high density EEG. Soc Neurosci. 2008;3:334–347. doi: 10.1080/17470910701563665. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ochsner KN, Bunge SA, Gross JJ, Gabrieli JDE. Rethinking feelings: an fMRI study of cognitive regulation of emotion. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002;14:1215–1229. doi: 10.1162/089892902760807212. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pfeifer JH, Iacoboni M, Maziotta JC, Dapretto M. Mirroring other's emotions relates to empathy and interpersonal competence in children. Neuroimage. 2008;39:2076–2098. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.032. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Philips ML, Ladouceur CD, Drevets WC. A neural model of voluntary and automatic emotion regulation: implications for understanding the pathophysiology and neurodevelopment of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:833–857. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.65. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL. Temperament and social behavior in childhood. Merrill Palmer Q. 1994;40:21–39. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sabbagh MA, Bowman LC, Evraire LE, Ito JMB. Neurodevelopmental correlates of theory of mind in preschool children. Child Dev. 2009;80:1147–1162. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01322.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Saxe RR, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Pelphrey KA, Scholz J. Brain regions for perceiving and reasoning about other people in school-aged children. Child Dev. 2009;80:1197–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01325.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Strum VE, Rosen HJ, Allison S, Miller BL, Levenson RW. Self-conscious emotion deficits in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Brain. 2006;129:2508–2516. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl145. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Swick D, Ashley V, Turken AU. Left inferior frontal gyrus is critical for response inhibition. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9:102e. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-102. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tamm L, Menon V, Reiss AL. Maturation of brain function associated with response inhibition. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:1231–1238. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200210000-00013. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tonks J, Williams H, Frampton I, Yates P, Slater A. Assessing emotion recognition in 9- to 15-year-olds: preliminary analysis of abilities in reading emotion from faces, voices and eyes. Brain Inj. 2007;21:623–629. doi: 10.1080/02699050701426865. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vaish A, Carpenter M, Tomasello M. Sympathy through affective perspective-taking, and its relation to prosocial behavior in toddlers. Dev Psychol. 2009;45:534–543. doi: 10.1037/a0014322. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Warneken F, Tomasello M. The roots of human altruism. Br J Psychol. 2009;100:455–471. doi: 10.1348/000712608X379061. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yurgelun-Todd D. Emotional and cognitive changes during adolescence. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.03.009. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zaki J, Weber J, Bolger N, Ochsner K. The neural bases of empathic accuracy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11382–11387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902666106. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zelazo PD, Craik FI, Booth L. Executive function across the life span. Acta Psychol (Amst) 2004;115:167–183. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2003.12.005. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (230.1 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 23 April 2019

The neural development of empathy is sensitive to caregiving and early trauma

- Jonathan Levy 1 ,

- Abraham Goldstein ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9349-0621 2 &

- Ruth Feldman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5048-1381 1 , 3

Nature Communications volume 10 , Article number: 1905 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

35k Accesses

71 Citations

67 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Neuroscience

Empathy is a core human social ability shaped by biological dispositions and caregiving experiences; yet the mechanisms sustaining maturation of the neural basis of empathy are unknown. Here, we followed eighty-four children, including 42 exposed to chronic war-related adversity, across the first decade of life, and assessed parenting, child temperament, and anxiety disorders as contributors to the neural development of empathy. At preadolescence, participants underwent magenetoencephalography while observing others’ distress. Preadolescents show a widely-distributed response in structures implicating the overlap of affective (automatic) and cognitive (higher-order) empathy, which is predicted by mother-child synchrony across childhood. Only temperamentally reactive young children growing in chronic adversity, particularly those who later develop anxiety disorders, display additional engagement of neural nodes possibly reflecting hyper-mentalizing and ruminations over the distressing stimuli. These findings demonstrate how caregiving patterns fostering interpersonal resonance, reactive temperament, and chronic adversity combine across early development to shape the human empathic brain.

Similar content being viewed by others

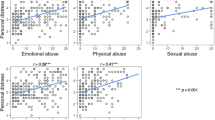

Increased empathic distress in adults is associated with higher levels of childhood maltreatment

Sensitive infant care tunes a frontotemporal interbrain network in adolescence

A context-dependent model of resilient functioning after childhood maltreatment—the case for flexible biobehavioral synchrony

Introduction.

Empathy, the capacity to resonate with and reflect upon the feelings and mental states of others 1 , is a core social ability sculpted by a long history of mammalian evolution to enhance species survival, afford group communication, and enable social life. To tap the neural mechanisms and maturational process of empathy, research has employed a cross-species approach and demonstrated that both rodents and nonhuman primates exhibit rudimentary empathy expressed in contagion and mimicry 2 . Complementing this effort, neuroimaging studies in humans, typically targeting the adult brain, show that while human empathy similarly implicates automatic resonance to others’ distress, it also integrates higher-order neural activations that afford mentalization of others’ feelings and generation of an empathic response that differentiates self from other 3 . Yet, to understand the unfolding of human empathy from its origins, research must complement the phylogenetic approach with an ontogenetic one by utilizing prospective longitudinal studies that can pinpoint factors which over time facilitate or undermine maturation of the human empathic brain.

Developmental evidence indicates that the capacity for empathy emerges across the first years of life through complex interactions between the child’s biological dispositions and the quality of caregiving 4 , 5 . In parallel, research in social neuroscience describes dramatic shifts in maturation of the neural systems that sustain empathy 6 , 7 ; yet, the determinants that shape this neural development remain obscure. To track how multiple factors integrate to support maturation of the neural empathic response, we utilized a longitudinal study of children followed from early childhood to preadolescence and focused on three factors known to impact children’s empathic abilities. These include chronic early life stress (ELS), synchronous and attuned parent-child relationship, and temperamental reactivity implying heightened inborn responsivity to negative stimuli. Since prolonged adversity, particularly exposure to ELS, negatively impacts various social functions 8 , 9 , 10 including empathy 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , we followed a cohort living in a distinct ELS context, repeatedly observed mother–child interactions in the home environment, assessed temperamental reactivity in early childhood, and evaluated children’s anxiety disorders in late childhood to test their direct and indirect effects on the neural substrates of empathy at the transition to adolescence.

The daily experience of empathy involves both simulation of the bodily and affective states of others and drawing inferences about their mental states 1 , 16 , 17 . Yet, the early studies on the neuroscience of empathy distinguished between these two processes and examined them separately under laboratory conditions. Subsequently, conceptual models differentiated two components of empathy; affective empathy/resonance and cognitive empathy/mentalization 1 , 17 , a dichotomy that was mapped into distinct brain structures and neural networks. The first, affective empathy/resonance, was thought to involve automatic response to others’ pain and feelings and to rely on structures that support sensorimotor perception and their representation in one’s own brain, such as the primary somatosensory and motor cortices, anterior cingulate cortex, and sensorimotor area (SMA), implicating the embodied simulation network; the second, cognitive empathy/mentalization integrates higher-order cortical regions to understand others’ mental life and includes the prefrontal cortex (PFC), temporoparietal junction, superior temporal sulcus (STS), and temporal pole, which comprise the mentalizing network 1 , 2 , 17 .

Notwithstanding this distinct cerebral mapping (Fig. 1 , right panel), such dual dissociation model is somewhat artificial. Drawing parallels between this and other dual models 18 , in real-life situations, one typically employs both processes, albeit to varying degrees pending on person and context. Indeed, ecologically valid experiments that simulate real-life settings indicate that the two networks reflect two facets of social living and function in concert to support human empathy 10 , 16 , 17 , 19 . One important observation from these studies was that under natural settings, the sensorimotor area and the middle cingulate cortex (SMA/MCC) underpin both embodied simulation and mentalizing processes, integrating the affective and cognitive components of empathy 2 , 20 , 21 (Fig. 1 , right panel in green). For instance, an empathy paradigm that exposed participants to distressing stimuli of everyday life (triggering embodied simulation) while asking participants to take the target’s perspective (activating mentalizing) yielded activations containing the SMA/MCC node 22 . Here, we adopt the same paradigm to probe empathy (hereafter we use the term “empathy” for the two facets, unless otherwise specified) and test the developmental precursors of this shared empathy network.

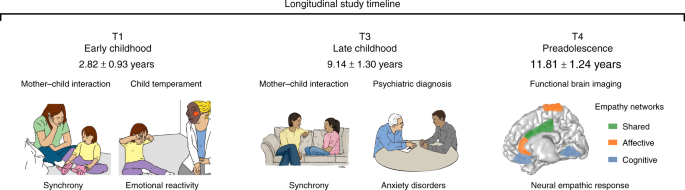

Longitudinal study timeline. In T1, at early childhood, child and mother interacted with each other; mother–child synchrony was calculated. In T3*, Psychiatric diagnosis was conducted and child and mother interacted again and the synchrony construct was again computed; hence Maternal Synchrony scores leaned on the T1 and T3 interactions. In T4, neural empathic response to vicarious distress was evaluated using MEG neuroimaging. Illustration of empathy networks is inspired by the comprehensive review of de Waal and Preston 2 . *The Synchrony illustration is adapted and reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press. © The Author 2017. All rights reserved. For permissions, please email [email protected]. This figure is not included under the open access license of this publication. The original figure is Fig. 1a —Jonathan Levy, Abraham Goldstein, Ruth Feldman, Perception of social synchrony induces mother–child gamma coupling in the social brain. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2017; 12 (7): 1036–1046

Despite growing interest in the neuroscience of empathy, there are nearly no data on the developmental processes that tune the brain toward an empathic response. Several factors may contribute to neural empathy, the first is sensitive caregiving. In particular, the experience of parent-child synchrony, the parent’s ongoing resonance and online adaptation to the child’s nonverbal signals and verbal communications, is associated with children’s empathy across childhood and adolescence 23 . The mother–child bond provides a setting where synchrony is first experienced and encoded in the brain 24 , creating a template for the child’s later resonance with the distress, feelings, and thoughts of others 25 . When the mother’s capacity to provide synchronous parenting is compromised, for instance, in cases of postpartum depression, children show reduced empathic behavior 26 and impaired neural empathic response to others’ pain in adolescence 27 . Synchrony is the process by which mother’s brain impacts the child’s brain and wires it to social participation 25 ; during moments of behavioral synchrony mother and child’s brains synchronize in the STS 28 , a social neural hub, and behavioral synchrony across the first 6 years predicts adolescents’ neural response to attachment cues in key nodes of the social brain, including the STS, STG, and Insula 29 .

Second, exposure to chronic adversity impairs social–emotional processing 4 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 and the effect is most prominent when adversity begins early and persists throughout early childhood 9 , 30 , 31 . Research utilizing fMRI 13 and MEG 11 show that trauma alters neural responses that underpin the affective and cognitive components of empathy. Adults exposed to early trauma exhibit abnormal neural response to negative emotional stimuli and impairments in the brain basis of social functions 30 , 32 , and children and adolescents exposed to ELS display impaired processing of affective facial expressions 33 , 34 , implying disruptions to emotional processing which sustains empathy. Thus, while no direct evidence links ELS to children’s neural empathic response, these lines of research lend support to this hypothesis.

Although chronic ELS disrupts social functioning, substantial individual differences exist, which are shaped by biological dispositions as they interact with the specific adversity 35 . Most studies on the long-term effects of ELS employed biology-by-context models that target variations in dispositional stress reactivity as they interact with stressful environments 36 . Heightened stress reactivity reflects increased biological sensitivity to context, which augments the effects of stress on negative outcomes under conditions of ELS 37 , 38 . One mechanism proposed to mediate the detrimental effects of ELS on social outcome is temperamental reactivity, the heightened dispositional response to negative stimuli. Early adversity augments attention to negative and frightening events 31 , and when combined with inborn reactivity to negative stimuli, it may lead to difficulties in disengaging from distressing cues 39 . Such exaggerated response is often accompanied by repeated mentalization and ruminations over the distressful event 40 . Moreover, early temperamental reactivity increases the propensity to develop anxiety disorders in later childhood and adolescence 41 . Anxiety disorders, in turn, impair the neural basis of multiple social–emotional functions 42 , are associated with increased ruminations over negative events, and link with inability to disengage from negative stimuli 43 .

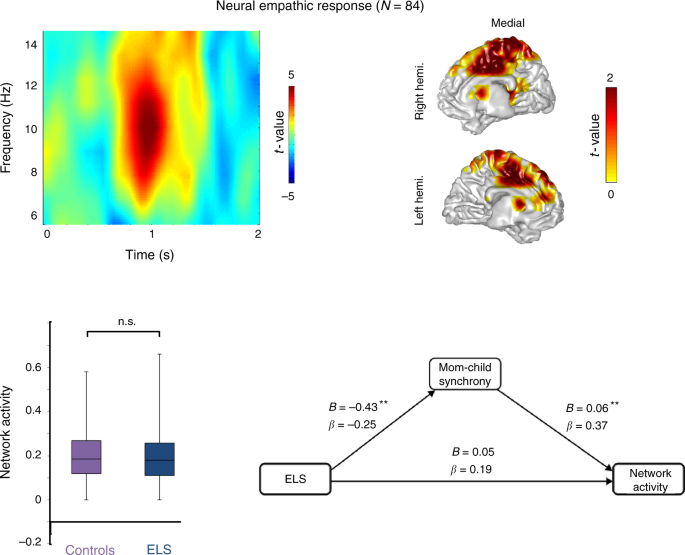

The current decade-long prospective longitudinal study integrated repeated observations of parenting with lab-based assessment of negative reactivity and psychiatric evaluations to predict the neural basis of empathy among children exposed to ELS versus controls. We utilized a unique cohort of children exposed to war-related trauma since birth who experience frequent, unpredictable exacerbations of the traumatic situation. Children and their families were followed from early childhood to early adolescence (Fig. 1 ) and thus, our study affords a rare “natural experiment” in ELS research that typically includes heterogeneous adversities. In preadolescence (11–13 years), we used magnetoencephalography (MEG) to probe children’s oscillatory response to others’ distress and focused on alpha rhythms, which underpin empathic processes 44 , 45 and express in children as late alpha-band enhancement in sensory cortex to others’ pain 7 . Here, our paradigm additionally involved perspective-taking and was expected to activate substrates supporting both affective and cognitive empathy, such as the SMA and MCC 2 , 20 , 21 .

We formulated two hypotheses and one open research question. First, we expected that the neural empathic response in preadolescence will implicate structures that support the shared affective and cognitive empathy, namely the SMA and the MCC, and that these activations will be underpinned by late alpha-band enhancement. Second, we hypothesized that activation of this neural network will be longitudinally predicted by mother–child synchrony across the first decade of life. Next, since no prior research linked ELS with the neural development of empathy, we explored direct and indirect ways by which ELS impacts the neural empathic response as an open research question. For this goal, we explored neural patterns that are specific to trauma-exposed youth and tested their associations with temperamental reactivity and anxiety disorders. Consistent with the biological sensitivity to context model 37 , we expected that only among trauma-exposed youth, these putative neural patterns will be shaped by early reactivity. Additionally, we conjectured that these stress-specific activations would link with the consolidation of a distinct anxiety disorder in late childhood. We find that at preadolescence, the neural empathic response implicates structures tapping the overlap of cognitive and affective empathy, such as SMA and MCC. In addition, adolescents’ neural empathic response is sensitive to caregiving across the first decade, particularly mother–child synchrony, and to chronic early trauma. Finally, temperamentally reactive children reared in stressful contexts are more likely to develop anxiety disorders and show additional activation in nodes possibly reflecting hyper-mentalizing and difficulties in disengaging from negative cues.

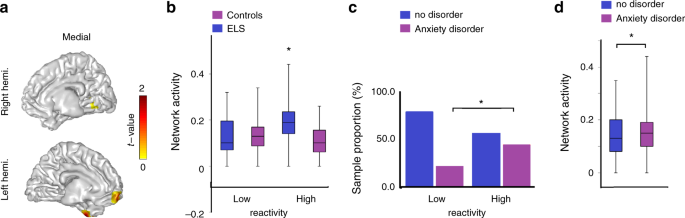

Group differences in study variables

A tendency toward lower ( t = −2.29, P = 0.02 uncorrected , t test; Cohen’s d = 0.50; 95% confidence interval [0.056–0.800]) mother–child synchrony was found for war-exposed families ( M = 3.45, SD = 0.90) compared to controls ( M = 3.88, SD = 0.78). No statistically significant differences ( t = −0.95, P = 0.34, t test) emerged in temperamental reactivity between exposed ( M = 0.37, SD = 0.09), and control ( M = 0.35, SD = 0.12) children. War-exposed children were significantly more likely to develop an anxiety disorders (50%), compared to only 11.90% among controls, Χ 2 (1) = 14.03, P FDR-cor = 0.0002, Χ 2 -test; Cramer’s V = 0.41. Comparing the current sample ( N = 84) and those lost to attrition from T1 ( N = 148), there were no significant differences on synchrony and temperamental reactivity ( t = 1.50 and −0.48, P = 0.13 and P = 0.63, respectively, t tests).

Self-reported empathy