Feb 14, 2023

How to Write An Argumentative Essay (With Examples)

Are you looking for ways how to write an argumentative essay check out these helpful examples.

An argumentative essay is a writing genre that obligates the writer to examine a topic; collect, generate, and evaluate proof; and clearly present a perspective on the issue. It can be tricky to write, but with a little practice, they can become relatively easy.

To write an argumentative essay, it is important to always have a strong argument as your topic and should greatly rely on evidence and logic. However, there is a slight bit of wiggle room within your essay. For example, your thesis statement may include an opinion or a controversial idea, and while you should still support it with facts, it is possible to add your opinion to the essay without going against the objective of the essay.

If you want to create a high-quality argumentative essay, Jenni.ai is here for you! This AI-assistant writing software can easily help you with writing any kind of academic paper, including your argumentative essay.

Tips on how to make an Argumentative Essay

Creating an argumentative essay can be quite daunting, especially if you are not used to writing this kind of essay. However, there are some simple guidelines you can follow to ensure that your essay will be both coherent and convincing:

Make sure to choose a topic with strong talking points. This makes it easier to form strong coherent arguments that will dictate the direction you want to take with your essay.

Use the correct tone when creating your argumentative essay. People mistake assertiveness in argumentative essays to mean being aggressive and argumentative, which will not win you any points with your readers. Convincing arguments should be presented calmly and clearly in the introduction section of your essay, with supporting information being presented throughout the body of your essay.

Make sure to use factual statements when presenting your arguments. This is important if you are writing an academic essay as this ensures that your arguments are well-researched and thought out. Fact-based research is always more reliable than opinions.

Keep your arguments logical and concise. This will make it easy for your readers to follow your train of thought and helps to keep them engaged throughout the essay.

Make sure that you indicate all the relevant talking points in a clear and concise manner in your conclusion section.

Always make sure to proofread your work thoroughly throughout your writing process because typos and grammatical errors will greatly affect the quality and credibility of your work.

With these tips in mind, you are on your way to creating a high-quality argumentative essay that is easy to understand and will be compelling to your readers.

How to create an Outline for your Argumentative Essay

As we already know, creating an argumentative essay involves a strong topic in order to create a strong argument. Creating an outline for it is a lot easier than most people think, especially for beginners. Here are some simple steps to create an argumentative essay:

1. Research your topic - As mentioned above, you will need to carry out in-depth research to find suitable evidence to back up your argument. If you know what you are going to write about before carrying out your research, then you will be able to structure it more easily.

2. Introduction - In this part of your essay, you will want to introduce the reader to the topic that you will be discussing. The introductory paragraph works like a hook to entice your readers about your interesting topic. Make sure to create an introduction that is easy to understand so that your readers will be interested in reading. A good way to do this is by providing them with a brief background about the topic so that they understand it better.

3. Hypothesis or Premise - This is where you present your main arguments about your topic. You could provide questions to answer or evidence to support your claims. It will serve as the basis for the argument in your essay. Keep in mind that you will need to support all of your points with evidence from your research.

4. Body - Like any good argumentative essay, your body should contain all of the supporting evidence that you will use to support your argument. Each body paragraph should be dedicated to a different point that you would like to make. Body paragraphs cover different pieces of evidence that you provide to support your claims throughout the essay.

5. Conclusion - This is where you create a summary of all your talking points. This could also serve as a brief refresher of what you have discussed in the body of the essay. The conclusion is one of the most important parts of your essay because this is where you rebut the opposing arguments and remind your reader of the key points that you have discussed in the paper.

Types of Argumentative Essay

1. Rogerian Argumentative Essay - This type of essay is great for controversial topics because its creator, Carl Rogers intended this essay type to be as tame and respectful as possible.

The Rogerian style is centred around maintaining a balance between the two sides of the argument rather than siding with one opinion over the other. After both sides have been considered, a great way to end this essay is with a proper resolution of all the arguments presented. Usually, this results in finding a way to bring the two sides together rather than permanently sidelining one opinion over another.

This approach promotes both intellectual honesty and responsible thinking, which is a great way to approach an argumentative essay!

2. Classic Argumentative Essay - This type of argumentative essay entices the reader to a certain point of view.

This style is developed by Aristotle and it requires the reader to look at both sides of the argument while ultimately deciding which one is the most concise and factual. An essay like this requires a presentation of claims and counterarguments as well as an overall claim about the topic being argued over.

3. Toulmin Argumentative Essay - Arguments are broken down into multiple elements in order to prove a point. The main elements to follow with the Toulmin argumentative essay are the claim, grounds, warrant, qualifier, rebuttal, and backing.

The claim is the thesis that is being argued for, while the grounds are the arguments that back up the claim.

The warrant is the argument from which the claim can be proven; this can be based on historical data, social or cultural research, or scientific research.

The qualifier is the explanation that explains the basis on which the claim was made and the justification provided to justify the claim.

The rebuttal is the part where you respond to the claims that have been presented against your claim. This can be used to acknowledge an opposing viewpoint by proving your reasoning and logic are stronger or more logical than theirs.

And the backing is the part of your essay where you convince your reader to take a side in the argument.

The Toulmin argument is best used when there could be several possible solutions to a certain argument. This style is also very useful for debates and discussions because it allows both sides of an argument to be laid out for consideration.

Argumentative Essay Examples

Now that we've explained the different types of argumentative essays as well as useful tips you can use throughout your writing process, here are some excerpt examples of the different types of argumentative essays:

1. Is School Conductive to Learning? (Classical Argumentative Essay)

"If students get As on a test then they know the material, right? How many of those students would still know the information if you asked them about a week later? How about a month later? Most students will not remember most of the information for very long after the test. Why is that? They learned it, didn't they? Well, that depends on how you define "learning". "Learning" is gaining knowledge and experience which stays in the long-term memory and is of value to the recipient. So we have to ask, is our education system really teaching children?

The way education is set up in this country is simple. There is usually only one teacher in a classroom teaching from 12 to 30 students at a time. Information is written on a blackboard in the front of the room while the children take notes and listen. There may be some variation depending on the school and teacher. Then the students are tested on the material. After the test, the class moves on to new information. The material is usually not looked at again until a final test at the end of the semester, for which students study very hard a few days before. If they pass the test it is assumed that they "learned" the information, regardless of if they forget it later. Our education system is not only not enhancing learning but may actually be inhibiting it.

The education system in the United States today treats the minds of children like bowls to be filled with information. What it does not realize is that if you fill a bowl too quickly most of the liquid will bounce back out. It is the same with the mind of a child. When they are given too much information in such a small amount of time very little of it is actually retained. This is because of the vast amount of information students are given in very small amounts of time. Children study a single topic for two weeks to a month and then they are tested on it. After the test, they study something different for the next two weeks to a month. This causes the previous information to be forgotten and replaced by new information. This means that children end up with only very general knowledge of the topics studied.

A few children do learn this quickly, but not very many. Children learn at greatly varying paces, however, schools assume that all children learn at the same speed. This causes many children to be very frustrated and give up trying to learn. Many children who learn at a slower pace fall behind beyond any hope of catching up. Often the children who learn more quickly get bored and give up completely. Many of these children begin associating learning with boredom or frustration and actually start to dislike and even fight against learning.

Our system of schooling is not set up the way it should be. It was created to enhance learning, to teach children what they needed to know. It has strayed from that purpose. Our school system not only does not teach, but it turns students away from learning. Our children deserve better than this. They deserve to be shown how much fun and how beneficial learning can be. Learning can be what gives our lives value, but we are cheating our children of that. The school system needs to be seriously looked at and changed. The future of our world could be shaped by how well our children are prepared for it. They will be better prepared for it if they are shown how important and how rewarding knowledge and confidence can be. If our children are given these building blocks then they will become stronger adults and they will enhance the structure of the human world."

2. Helmets: Life or Liberty? (Rogerian Argumentative Essay)

"Snowboarding and snow skiing are two of the most enjoyed recreational sports in the world today. They give a unique sense of freedom and satisfaction that is unlike any other sport that can offer. Rob Reichenfeld remarked after his first lesson, “When you’re onto a good thing you stick with it, and like millions around the world I had discovered something undefinably special” (2). The freedom to carve down an entire mountain as fast or as slowly as desired, to drop off a twenty-foot cliff into five feet of fluff, to weave a line through a patch of technical trees, or to float down a steep face with bottomless powder is just a few reasons so many people are determined to make it to the mountains every year in search of a supreme rush. Snow sports provide an outlet for people to express themselves in unconventional ways by taking risks they normally would not take.

Snow sports are becoming more popular than ever before. They are prevalent in movies such as Extreme Days, Out Cold, several James Bond films, and Aspen Extreme, just to name a few. Now we see the X Games on television and snow sports in the Olympics. And the commercial market has taken full advantage of the extreme side of these sports as well. Mountain Dew has created an entire marketing scheme based solely on extreme sports, with snowboarding being a large part. Not only are snow sports becoming exceeding popular in the media, but more and more newcomers are also picking up a board or a set of skis every day of the winter season.

Along with all of this new popularity and thousands of new partakers in these sports, head injuries are becoming an increasing element of the equation. Although the percentage of head injuries due to snow sports is fairly low, about 0.3—6.5 skiers or snowboarders per thousand a day (“Heads you win?…”), a lot of people are affected when you consider how many thousands of people might be skiing or snowboarding in the entire U.S. on any given day. These numbers have raised a question of some magnitude: should ski resorts intrude on their guests’ individual liberties by implementing helmet rules?

Helmets do have several distinct drawbacks, despite their many benefits. Though opinions are starting to change, helmets are sometimes viewed as uncool or “nerdy”. These ideas are similar to those people used to have about motorcycle helmets, car seat belts, bicycle helmets, and skating elbow- and kneepads. Initially, it seems, any form of safety equipment gets a bad rap, especially from a young crowd that has no real concern for bodily harm.

The benefits of wearing head protection while resort skiing or snowboarding greatly outweigh the disadvantages, so such protective headgear should be required by all ski resorts. With the improvements being made in the comfort, stylishness, and effectiveness of helmets in the industry, there are no excuses left for skiers or boarders not to be wearing them. These types of resort rules could save countless lives as well as possibly save innumerable tax dollars that are spent on the medical costs of people who receive brain damage as a result of snow sport-induced head trauma. Such rules would also serve to lower lift ticket prices, as less money would be spent by resorts to defending against lawsuits brought on by head trauma victims. It would be to the benefit of everyone in the snow sports community if such regulations were to be put into place. I hope that they will indeed be applied in the near future, further insuring many more years of safe and exhilarating snow sporting."

3. The Power of Black Panther (Toulmin)

"Despite it just hitting theatres, Black Panther is already labelled as a ‘cultural movement’. Many Marvel fans eagerly waited to see the movie while discussions exploded on social media about Marvel’s new black superhero. However, not all of the discussions have stayed peaceful. With the emergence of this hero comes the emergence of the timeless debate of race, more specifically race in the media and how it is presented. There are some who say that having a black hero should not be this big of a deal and they deny the need for heroes of colour. Morals are colourless; we’ve learned from and enjoyed the millions of white heroes, so why is this black hero so special?

The issue here runs far deeper than this and goes beyond comic book characters. The real issue is the overall representation of minority groups in America. There needs to be a better representation of minorities in media to help the majority understand them and to help minorities feel a part of society. These are important factors in peace and unity within our nation. II. For the longest time, white men have dominated all American media industries, especially cishet men. Cishet refers to a person who is both cisgender and heterosexual. Over the years, women and minorities have fought to get where they are Background and issue questionClaimDefinitionDunne 2in the media today. They are now performing more and more roles outside of their stereotypes.

We need a more understanding majority and minorities who feel like they are an equal part of society, in order to come together and work for a better nation. Having fair media representation for minorities is a vital key to doing so. With the current hate destroying our country, we need to educate ourselves and each other. What better way to change a nation obsessed with its media, than with the media?"

Creating argumentative essays is quite a complex process and there are multiple styles and ways to approach it. The goal of the process is to convince the audience of your point of view based on evidence or facts rather than personal opinions.

If you want to create high-quality argumentative essays, we recommend using Jenni.ai to speed up your writing process and help you craft more compelling arguments! You can sign up at Jenni.ai for free here !

Try Jenni for free today

Create your first piece of content with Jenni today and never look back

- Gradehacker

- Meet the Team

- Essay Writing

- Degree Accelerator

- Entire Class Bundle

- Learning Center

- Gradehacker TV

How to Write an Argumentative Essay: What You Need to Know

Santiago mallea.

- College Skills , Student Life Hacks , Writing Tips

Chief of Content At Gradehacker

Updated August 2023

Learn how to write an argumentative essay with our video:

Among the many types of essays that students find in their college classes, argumentative essays are one of the most common. Whether you are studying nursing, business, or economics, you will eventually have to write an argumentative paper for one of your courses.

But if academic writing is not one of your best skills, creating an argumentative essay won’t be an easy task.

Luckily, there are many things you can learn to improve your results, and here at Gradehacker, we are about to show you all of them!

After many years of helping students with their essays as the non-traditional student #1 resource, here is a step-by-step guide on how to write an argumentative essay.

Get a Convincing Argumentative Essay

Struggling to write a complex argumentative paper? Submit your request for free and get personalized help!

But first, let’s start from the basics.

What is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative paper is a type of essay that requires the writer to:

- Choose a topic

- Develop a solid anchor statement

- Collect and cite evidence

- Establish a firm piece of writing on the selected subject

It’s fact-based evidence work where school students persuade the reader to care about your topic.

You’ll always have to use extensive research , peer-reviewed arguments, and a strong piece of evidence that supports your original argument.

You can always share any personal opinions, but it needs to be sustained with key arguments.

Still, it’s also necessary to include a point of view that opposes your perspective . By addressing and refuting it with reliable academic sources, you give more credibility to your thesis to persuade any target audience!

Undoubtedly, one of the most common assignments that college students have to face. But because it’s common doesn’t have to mean that it’s easy.

Now that we understand the purpose of an argumentative essay let’s move on to tips on how to write it.

1. Choose a Strong Argumentative Essay Topic

Before you write your paper, you need to choose a suitable subject with plenty of academic sources that will let you develop a strong thesis statement.

Avoid simple, vague, or chliché debatable topics since they are too general and uninteresting. Choosing a broad subject will take you more time to research and most likely won’t give you the grade you desire.

Instead, think of a research subject you like and go for a more specific topic that will lead you to build a high-quality persuasive essay.

For instance, imagine your statement being:

“The death penalty in the United States is disproportionate.”

Rather than going with this vague argument, you might want to go for something like:

“The death penalty in the United States has been historically racially uneven since killers of white people were more likely than the killers of Black people to face the death penalty.”

See the difference? The second thesis statement is strong, interesting, and covers a specific ground, and there is a lot of information, statistics, and academic papers you can use to support your argument.

Pro Tip: Choose the topic with the most sources

Academic sources are what add value and credibility to your essay.

So, you need to ensure that the topic you choose has plenty of options . If you see that there isn’t enough information about it, try thinking of a new perspective or consider writing about a different subject.

2. Create an Outline

Once you have your thesis developed and sources selected, you’ll need to structure all that information in a simple outline.

While some courses will ask you to include an outline with your paper, the truth is that you should always make one , at least for you.

This way, you can organize all the topics you have to cover in one place, which will work as your roadmap while you are in the middle of the writing process.

To achieve a simple argumentative essay outline, here are some examples you can use:

- Introduction: Thesis statement

- First Paragraph: Argument 1

- Second Paragraph: Argument 2

- Third Paragraph: Opposite argument

- Fourth Paragraph: Counter-argument

- Conclusion: Restate the thesis

You can take a further step and add a concise summary of what each paragraph will touch on and which source you’ll use.

This personal roadmap might take you more time, but believe us, i t will rearrange all of the ideas altogether , and you can go back to it while you are writing in case you lose the flow.

Again, some courses don’t require you to create either of these outlines, but incorporating this practice as part of your writing process will significantly improve your experience throughout the entire essay by giving you a proper structure to follow from the start.

Pro Tip: Have an approximation of how long each paragraph will be

While it depends on the length of your assignment, knowing before you start how many words you should dedicate to each paragraph will give you a better idea of your current status.

You don’t necessarily have to stick to it as if it was mandatory but have these approximate numbers in mind to track your progress.

Stop Worrying About Essay Writing

Submit your request and see how our team of expert writers can help you deliver a plagiarism-free paper!

3. Introductory Paragraph

With sources selected and an outline is done, you can finally start writing your paper.

The introductory paragraph has two main goals:

- Provide a general context on your chosen topic

- Introduce the thesis statement

You need to hook the reader into your subject by making them understand why you are writing about that specific topic and why they should care about your statement.

You can achieve this by talking about a current problem or using a strong statistic that catches the eye of the reader.

Don’t quote any sources or refute opposite arguments yet. Just focus on making the reader interested in your topic by giving them context and stating your main argument, which will set up the rest of the essay.

Pro Tip: Don’t make the introduction too long or too short

Sometimes, college students write short or long introductions and barely touch or explain the thesis.

We recommend writing between 100 and 150 words . This should be enough to contextualize and state your main argument.

4. Body Paragraphs

The body paragraphs are the part where you get to develop your thesis by providing solid arguments supported by qualified sources.

This part is all about explaining why your argument is valid to the reader who was hooked by your thesis statement. Don’t be afraid of showing a solid position on the subject. Without using the first person, the reader should clearly understand your opinion.

After all, y ou are trying to convince them to care about your topic!

How to do it? Start by addressing the first issues within your topic and showing clear evidence supporting your point.

Once you have touched on all the main statements that prove your thesis right, you’ll have to include a perspective that states the contrary to your opinion . Find an accessible information source that counters your thesis, and refute it with more supporting ones.

Doing this will strengthen your main point and persuade the reader even more right before they finish reading your paper.

Still, whether it’s supporting or contradicting your statement, you should limit one idea per paragraph . If you develop each topic thoroughly in a separate paragraph, you’ll be able to build a naturally flowing structure where all arguments are related.

How can you keep the paragraphs linked? With connectors:

However; Furthermore; Moreover; Nevertheless; In addition to this; Even though; Nonetheless; On the contrary, and more!

Connectors are your best friends when writing any type of essay, and you should always have them in mind when writing.

Pro Tip: Use as many sources as you need

The more academic sources you use, the better!

Even if you only need to use one sentence or a small statistic, as long as it adds value to your statement, it’s worth using it!

5. Conclusion

You should think of your conclusion as what you want the reader to remember from your essay.

Start by recognizing the main issue with your subject. Then, you’ll have to revisit the main points of your paper and restate your thesis one last time .

Don’t just repeat the same words you have been using throughout your essay. Think about the most important statements you have made and expose them all together in the conclusion so the reader leaves with all these critical topics in mind.

Pro Tip: Don’t add new information

One common mistake some students make is adding new ideas to the conclusion.

Maybe you add a point you didn’t get to include, but if it wasn’t explained before, don’t bring it up! You can either f ind a way to include it in another part of the text or simply leave that information out.

Now that you know how to write an argumentative essay from scratch, you are ready to take the extra step and use Chat GPT to help you . Here is how you can do it!

Write The Best Argumentative Essay You Can

Writing an argumentative essay can be a challenging task.

If you want to write an outstanding paper , you’ll need to do extensive research, find a way to link all that information together, and come up with a specific and interesting thesis statement that has material to work with and catches the eye of the reader.

But if you still feel like you need some help writing, you can count on Gradehacker to have your back. We are experts in writing all types of essays and have helped many college students with their exams and classes . We’ll be happy to help you too!

If you want to learn more tips on how to improve your writing skills, you can check our related blog posts:

7 Best Websites to Find Free College Textbooks in 2024

Best iPads For College Students

List of Topics for your Research Paper | Find Yours Here!

Argumentative Essay vs Narrative Essay | Everything You Need to Know

The Best Thesis Generator Apps

How Much Does it Cost to Write My Essay?

How to use Chat GPT to Write an Essay

How To Write The GED Essay 2024 (Extended Response)

Top 5 Plagiarism Checkers For College Students

- Best Apps and Tools

- Writing Tips

- Financial Tips and Scholarships

- Career Planning

- Non-Traditional Students

- Student Wellness

- Cost & Pricing

- 2525 Ponce de Leon Blvd Suite 300 Coral Gables, FL 33134 USA

- Phone: (786) 991-9293

- Gradehacker 2525 Ponce de Leon Blvd Suite 300 Coral Gables, FL 33134 USA

About Gradehacker

Business hours.

Mon - Fri: 10:00 am - 7 pm ET Sat - Sun: 10 am - 3 pm ET

© 2024 Gradehacker LLC All Rights Reserved.

Last places remaining for June 30th start. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- 9 Ways to Construct a Compelling Argument

You might also enjoy…

- How to Write with Evidence in a Time of Fake News

- 4 Ridiculous Things Actually Suggested in Parliament

But especially in the circumstances that we’re deeply convinced of the rightness of our points, putting them across in a compelling way that will change other people’s mind is a challenge. If you feel that your opinion is obviously right, it’s hard work even to understand why other people might disagree. Some people reach this point and don’t bother to try, instead concluding that those who disagree with them must be stupid, misled or just plain immoral. And it’s almost impossible to construct an argument that will persuade someone if you’re starting from the perspective that they’re either dim or evil. In the opposite set of circumstances – when you only weakly believe your perspective to be right – it can also be tricky to construct a good argument. In the absence of conviction, arguments tend to lack coherence or force. In this article, we take a look at how you can put together an argument, whether for an essay, debate speech or social media post, that is forceful, cogent and – if you’re lucky – might just change someone’s mind.

1. Keep it simple

Almost all good essays focus on a single powerful idea, drawing in every point made back to that same idea so that even someone skim-reading will soon pick up the author’s thesis. But when you care passionately about something, it’s easy to let this go. If you can see twenty different reasons why you’re right, it’s tempting to put all of them into your argument, because it feels as if the sheer weight of twenty reasons will be much more persuasive than just focusing on one or two; after all, someone may be able rebut a couple of reasons, but can they rebut all twenty? Yet from the outside, an argument with endless different reasons is much less persuasive than one with focus and precision on a small number of reasons. The debate in the UK about whether or not to stay in the EU was a great example of this. The Remain campaign had dozens of different reasons. Car manufacturing! Overfishing! Cleaner beaches! Key workers for the NHS! Medical research links! Economic opportunities! The difficulty of overcoming trade barriers! The Northern Irish border! Meanwhile, the Leave campaign boiled their argument down to just one: membership of the EU means relinquishing control. Leaving it means taking back control. And despite most expectations and the advice of most experts, the simple, straightforward message won. Voters struggled to remember the many different messages put out by the Remain campaign, as compelling as each of those reasons might have been; but they remembered the message about taking back control.

2. Be fair on your opponent

One of the most commonly used rhetorical fallacies is the Strawman Fallacy. This involves constructing a version of your opponent’s argument that is much weaker than the arguments they might use themselves, in order than you can defeat it more easily. For instance, in the area of crime and punishment, you might be arguing in favour of harsher prison sentences, while your opponent argues in favour of early release where possible. A Strawman would be to say that your opponent is weak on crime, wanting violent criminals to be let out on to the streets without adequate punishment or deterrence, to commit the same crimes again. In reality, your opponent’s idea might exclude violent criminals, and focus on community-based restorative justice that could lead to lower rates of recidivism. To anyone who knows the topic well, if your argument includes a Strawman, then you will immediately have lost credibility by demonstrating that either you don’t really understand the opposing point of view, or that you simply don’t care about rebutting it properly. Neither is persuasive. Instead, you should be fair to your opponent and represent their argument honestly, and your readers will take you seriously as a result

3. Avoid other common fallacies

It’s worth taking the time to read about logical fallacies and making sure that you’re not making them, as argument that rest of fallacious foundations can be more easily demolished. (This may not apply on social media, but it does in formal debating and in writing essays). Some fallacies are straightforward to understand, such as the appeal to popularity (roughly “everyone agrees with me, so I must be right!”), but others are a little trickier. Take “begging the question”, which is often misunderstood. It gets used to mean “raises the question” (e.g. “this politician has defended terrorists, which raises the question – can we trust her?”), but the fallacy it refers to is a bit more complicated. It’s when an argument rests on the assumption that its conclusions are true. For example, someone might argue that fizzy drinks shouldn’t be banned in schools, on the grounds that they’re not bad for students’ health. How can we know that they’re not bad for students’ health? Why, if they were, they would be banned in schools! When put in a condensed form like this example, the flaw in this approach is obvious, but you can imagine how you might fall for it over the course of a whole essay – for instance, paragraphs arguing that teachers would have objected to hyperactive students, parents would have complained, and we can see that none of this has happened because they haven’t yet been banned. With more verbosity, a bad argument can be hidden, so check that you’re not falling prey to it in your own writing.

4. Make your assumptions clear

Every argument rests on assumptions. Some of these assumptions are so obvious that you’re not going to be aware that you’re making them – for instance, you might make an argument about different economic systems that rests on the assumption that reducing global poverty is a good thing. While very few people would disagree with you on that, in general, if your assumption can be proven false, then the entire basis of your argument is undermined. A more controversial example might be an argument that rests on the assumption that everyone can trust the police force – for instance, if you’re arguing for tougher enforcement of minor offences in order to prevent them from mounting into major ones. But in countries where the police are frequently bribed, or where policing has obvious biases, such enforcement could be counterproductive. If you’re aware of such assumptions underpinning your argument, tackle them head on by making them clear and explaining why they are valid; so you could argue that your law enforcement proposal is valid in the particular circumstances that you’re suggesting because the police force there can be relied on, even if it wouldn’t work everywhere.

5. Rest your argument on solid foundations

If you think that you’re right in your argument, you should also be able to assemble a good amount of evidence that you’re right. That means putting the effort in and finding something that genuinely backs up what you’re saying; don’t fall back on dubious statistics or fake news . Doing the research to ensure that your evidence is solid can be time-consuming, but it’s worthwhile, as then you’ve removed another basis on which your argument could be challenged. What happens if you can’t find any evidence for your argument? The first thing to consider is whether you might be wrong! If you find lots of evidence against your position, and minimal evidence for it, it would be logical to change your mind. But if you’re struggling to find evidence either way, it may simply be that the area is under-researched. Prove what you can, including your assumptions, and work from there.

6. Use evidence your readers will believe

So far we’ve focused on how to construct an argument that is solid and hard to challenge; from this point onward, we focus on what it takes to make an argument persuasive. One thing you can do is to choose your evidence with your audience in mind. For instance, if you’re writing about current affairs, a left-wing audience will find an article from the Guardian to be more persuasive (as they’re more likely to trust its reporting), while a right-wing audience might be more swayed by the Telegraph. This principle doesn’t just hold in terms of politics. It can also be useful in terms of sides in an academic debate, for instance. You can similarly bear in mind the demographics of your likely audience – it may be that an older audience is more skeptical of footnotes that consist solely of web addresses. And it isn’t just about statistics and references. The focus of your evidence as a whole can take your probable audience into account; for example, if you were arguing that a particular drug should be banned on health grounds and your main audience was teenagers, you might want to focus more on the immediate health risks, rather than ones that might only appear years or decades later.

7. Avoid platitudes and generalisations, and be specific

A platitude is a phrase used to the point of meaninglessness – and it may not have had that much meaning to begin with. If you find yourself writing something like “because family life is all-important” to support one of your claims, you’ve slipped into using platitudes. Platitudes are likely to annoy your readers without helping to persuade them. Because they’re meaningless and uncontroversial statements, using them doesn’t tell your reader anything new. If you say that working hours need to be restricted because family ought to come first, you haven’t really given your reader any new information. Instead, bring the importance of family to life for your reader, and then explain just how long hours are interrupting it. Similarly, being specific can demonstrate the grasp you have on your subject, and can bring it to life for your reader. Imagine that you were arguing in favour of nationalising the railways, and one of your points was that the service now was of low quality. Saying “many commuter trains are frequently delayed” is much less impactful than if you have the full facts to hand, e.g. “in Letchworth Garden City, one key commuter hub, half of all peak-time trains to London were delayed by ten minutes or more.”

8. Understand the opposing point of view

As we noted in the introduction, you can’t construct a compelling argument unless you understand why someone might think you were wrong, and you can come up with reasons other than them being mistaken or stupid. After all, we almost all target them same end goals, whether that’s wanting to increase our understanding of the world in academia, or increase people’s opportunities to flourish and seek happiness in politics. Yet we come to divergent conclusions. In his book The Righteous Mind , Jonathan Haidt explores the different perspectives of people who are politically right or left-wing. He summarises the different ideals people might value, namely justice, equality, authority, sanctity and loyalty, and concludes that while most people see that these things have some value, different political persuasions value them to different degrees. For instance, someone who opposes equal marriage might argue that they don’t oppose equality – but they do feel that on balance, sanctity is more important. An argument that focuses solely on equality won’t sway them, but an argument that addresses sanctity might.

9. Make it easy for your opponent to change their mind

It’s tricky to think of the last time you changed your mind about something really important. Perhaps to preserve our pride, we frequently forget that we ever believed something different. This survey of British voters’ attitudes to the Iraq war demonstrates the point beautifully. 54% of people supporting invading Iraq in 2003; but twelve years on, with the war a demonstrable failure, only 37% were still willing to admit that they had supported it at the time. The effect in the USA was even more dramatic. It would be tempting for anyone who genuinely did oppose the war at the time to be quite smug towards anyone who changed their mind, especially those who won’t admit it. But if changing your mind comes with additional consequences (e.g. the implication that you were daft ever to have believed something, even if you’ve since come to a different conclusion), then the incentive to do so is reduced. Your argument needs to avoid vilifying people who have only recently come around to your point of view; instead, to be truly persuasive, you should welcome them.

Images: pink post it hand ; megaphone girl ; pencil shavings ; meeting ; hand writing ; boxers ; pink trainers; tools ; magnifying glass ; bridge ; thinking girl ; puzzle hands

Essay Papers Writing Online

Why argumentative essay writing is crucial for developing critical thinking and persuasive skills.

In today’s fast-paced and interconnected world, the ability to articulate one’s thoughts and opinions effectively has become an indispensable skill. Writing persuasive essays is an art that requires precision, creativity, and a deep understanding of the subject matter at hand. Whether you are a student aiming to excel in academics or a professional seeking to persuade others in the workplace, mastering the art of crafting persuasive essays can open doors to endless opportunities.

A persuasive essay is not simply an expression of personal beliefs; it is a carefully constructed argument that aims to convince the reader of a particular point of view. As such, it requires a strategic approach that involves thorough research, critical analysis, and logical reasoning. While some may view persuasive writing as an arduous task, it is, in fact, a fulfilling endeavor that allows individuals to harness the power of language and shape the perceptions of others.

Throughout this comprehensive guide, we will explore the various components that contribute to the art of persuasive essay writing. From developing a strong thesis statement to incorporating persuasive techniques, this manual will equip you with the necessary tools and knowledge to effectively convey your ideas and sway even the most skeptical of minds. So, prepare to embark on a journey of exploration and self-discovery as we delve into the intricacies of the craft of crafting persuasive essays.

Understanding the Basics of Argumentative Writing

Mastering the fundamentals of persuasive composition is an essential step in becoming a proficient writer. Argumentative writing is a skill that enables writers to present persuasive arguments, backed by evidence and reasoning, to convince readers of a particular viewpoint. By understanding the basics of argumentative writing, writers can effectively communicate their opinions and persuade their audiences to adopt their side of the argument.

In argumentative writing, the writer aims to present a clear and concise thesis statement that outlines their main contention. The thesis statement serves as the backbone of the essay, guiding the writer’s logical reasoning and supporting evidence. Furthermore, the writer must develop well-structured paragraphs, each with a specific topic sentence that supports the overall thesis statement.

In addition to presenting strong evidence, argumentative writing requires writers to acknowledge and address counterarguments. By acknowledging opposing viewpoints, writers can weaken the opposition’s arguments and strengthen their own. A well-developed argumentative essay should also include a rebuttal, where the writer refutes counterarguments and reinforces their thesis statement.

Argumetative writing is not only about presenting a strong argument but also about using persuasive language and rhetoric to engage the reader. Writers should strive to appeal to the reader’s emotions and logic through careful word choice and sentence structure. By effectively utilizing persuasive techniques, writers can enhance the overall impact of their argument and leave a lasting impression on the reader.

Overall, understanding the basics of argumentative writing is crucial for anyone aiming to craft compelling essays. With a solid understanding of thesis statements, logical reasoning, supporting evidence, counterarguments, and persuasive techniques, writers can effectively convey their ideas and persuade readers to adopt their viewpoint. By honing these skills, writers can become powerful advocates for their opinions and make a meaningful impact through their writing.

Research: The Key to Building a Strong Argument

Conducting thorough research is vital when it comes to constructing a strong and persuasive argument. In order to effectively convince your audience and present a persuasive case, you must gather relevant information and evidence to support your claims and counter any opposing viewpoints.

Research provides you with the necessary tools and resources to develop a well-informed argument. By exploring various sources such as academic journals, books, reputable websites, and expert opinions, you can gather valuable information that will strengthen your position and make your argument more persuasive.

One important aspect of research is the ability to critically analyze and evaluate the credibility of sources. It is essential to ensure that the information you include in your argument is from reliable and trustworthy sources. This helps establish your credibility as a writer and enhances the credibility of your argument as a whole.

Additionally, research allows you to anticipate and address potential counterarguments. By uncovering and understanding different viewpoints and perspectives related to your topic, you can preemptively address any opposing arguments and provide rebuttals. This not only strengthens your own argument but also demonstrates your knowledge and understanding of the topic.

Incorporating research into your argumentative essay also helps you develop a logical and well-structured presentation of your ideas. By organizing your researched information in a coherent manner, you can effectively guide your readers through your argument and present your evidence in a logical and convincing way.

In conclusion, research plays a significant role in building a strong argument. By conducting thorough research, analyzing and evaluating sources, addressing counterarguments, and organizing your information effectively, you can develop a persuasive and compelling argument that captures your readers’ attention and convinces them of your viewpoint.

Crafting a Persuasive Thesis Statement

The foundation of a strong argumentative essay lies in a well-crafted thesis statement. This vital component serves as the guiding force behind the entire essay, setting the tone and direction for the writer’s persuasive argument. A persuasive thesis statement effectively communicates the writer’s stance on a particular topic while also providing a clear roadmap for the reader to follow throughout the essay.

To craft a persuasive thesis statement, it is essential to choose a topic that sparks controversy or disagreement among readers. This ensures that the thesis statement will inspire strong emotions and opinions, making it easier for the writer to present their argument and persuade the reader to agree with their viewpoint.

When formulating a persuasive thesis statement, it is essential to clearly state the writer’s position on the topic. This can be accomplished through a direct statement or by posing a thought-provoking question that invites the reader to consider the writer’s perspective. By being explicit in their stance, the writer establishes credibility and demonstrates their confidence in their argument.

In addition to taking a clear position, a persuasive thesis statement should also provide a compelling reason or rationale for the writer’s viewpoint. This can involve presenting relevant evidence, citing trusted sources, or appealing to moral or emotional values. By incorporating a persuasive element into the thesis statement, the writer sets the stage for the rest of the essay to build upon and support this position.

Furthermore, a persuasive thesis statement should be concise and focused. It should convey the main idea of the essay in a succinct manner, avoiding ambiguity or excessive complexity. By keeping the thesis statement clear and to the point, the writer ensures that the reader understands the overall objective of the essay and can easily follow the writer’s line of reasoning.

To conclude, crafting a persuasive thesis statement is a critical step in the process of writing an argumentative essay. It lays the groundwork for a strong and compelling argument, guiding the writer’s thought process and providing a clear direction for the reader. By choosing a controversial topic, taking a clear position, providing solid rationale, and maintaining conciseness, the writer can create a persuasive thesis statement that sets the stage for a successful essay.

The Structure and Organization of an Argumentative Essay

When it comes to composing a persuasive piece of writing, having a clear and well-structured essay is of utmost importance. The structure and organization of an argumentative essay play a vital role in effectively presenting your ideas and persuading your audience to agree with your viewpoint. By following a logical structure and organizing your arguments coherently, you can strengthen the impact of your essay and make it more compelling.

There are several key components that contribute to the structure and organization of an argumentative essay. First and foremost, your essay should have a strong introduction that grabs the reader’s attention and clearly states your thesis statement. The thesis statement is the central argument or claim that you will be supporting throughout your essay.

After the introduction, the body paragraphs of your essay should be devoted to presenting and supporting your arguments. Each body paragraph should focus on a single point or aspect of your argument and provide evidence, examples, or reasoning to back it up. It is essential to present your arguments in a logical and organized manner, using transitional phrases or words to ensure smooth flow between paragraphs.

Additionally, it is crucial to acknowledge and address counterarguments or opposing viewpoints in your essay. By acknowledging opposing viewpoints, you demonstrate a thorough understanding of the topic and establish your credibility as a writer. Refuting counterarguments and providing evidence to support your own argument will strengthen your essay’s persuasiveness.

In the conclusion of your argumentative essay, you should summarize your main points and restate your thesis statement in a way that leaves a lasting impression on your reader. A strong conclusion should not introduce any new information but should instead reinforce the importance and validity of your argument.

Overall, the structure and organization of an argumentative essay are essential elements that contribute to the effectiveness of your writing. By carefully planning and structuring your essay, presenting and supporting your arguments coherently, and addressing counterarguments, you can create a compelling and persuasive piece of writing that effectively communicates your viewpoint.

Effective Strategies for Presenting Evidence and Counterarguments

Mastering the art of persuasive writing involves being able to effectively present evidence and counterarguments. As a skilled writer, you must not only provide strong evidence to support your claims but also anticipate and address potential counterarguments. This section will explore some effective strategies for presenting evidence and counterarguments in order to build a compelling case for your argument.

One strategy for presenting evidence is through the use of credible sources. By referencing reputable research studies, expert opinions, and statistical data, you can add credibility and validity to your argument. Be sure to properly cite your sources and include a variety of different types of evidence to strengthen your points.

In addition to using credible sources, it is important to clearly explain how the evidence supports your argument. Provide a logical and coherent analysis of the evidence, outlining the key findings and explaining why they are relevant to your thesis. By demonstrating a deep understanding of the evidence, you can make a convincing case for your argument.

Another effective strategy is to anticipate and address potential counterarguments. By acknowledging opposing viewpoints and addressing them head-on, you can strengthen your own argument and demonstrate your ability to think critically. Use logical reasoning and evidence to refute counterarguments, demonstrating why they are flawed or invalid.

When presenting counterarguments, it is important to do so respectfully and objectively. Avoid using inflammatory language or attacking the person making the counterargument. Instead, focus on the weaknesses in their logic or evidence and present a strong counterpoint backed up by evidence and reasoning.

In conclusion, presenting evidence and counterarguments effectively is essential for writing a persuasive argumentative essay. By using credible sources, explaining how the evidence supports your argument, anticipating and addressing counterarguments, and maintaining a respectful and objective tone, you can build a strong case for your point of view.

Related Post

How to master the art of writing expository essays and captivate your audience, convenient and reliable source to purchase college essays online, step-by-step guide to crafting a powerful literary analysis essay, unlock success with a comprehensive business research paper example guide, unlock your writing potential with writers college – transform your passion into profession, “unlocking the secrets of academic success – navigating the world of research papers in college”, master the art of sociological expression – elevate your writing skills in sociology.

- How It Works

- Topic Generator

- United States

- View all categories

Best Tips for Writing a Strong Argumentative Essay: Easy Step-by-Step Guide

Most likely, you have heard about argumentative essays at least once. What is this paper, and what is its purpose? Well, the main goal is to establish a definite position and attitude towards the selected issue and substantiate it with evidence. What is the best way to write an argumentative essay? There are four aspects that you should pay attention to:

- Your subject must be interesting.

- You must be convincing (make your claims).

- It is necessary to find answers to counterarguments in advance.

- Motivate the reader to accept your point of view.

Of course, such a paper's complexity depends on the chosen topic and the depth of research. But here, you get the main argumentative essay tips. This will help analyze the subject better and prepare the most reasoned position on each item.

What Should Such a Paper Have?

The first thing you need is to argue your position and create a strong thesis. Next, you have to conduct logical reasoning and provide convincing arguments. But these are not all tips for writing an argumentative essay . Do not forget about good examples, evidence, and any data that will prove your position on each point or question.

Three Main Steps & Tips on How to Write a Strong Argumentative Essay

1: topic & thesis statement.

A good hook for an argumentative essay is the first thing you need. The topic you choose may have varying degrees of relevance. Moreover, your professor may not leave you a chance. In any case, you should create a strong thesis statement. This will allow you to indicate the paper's main purpose, its significance, and even the level of expertise.

This is something like a vector of your movement because all subsequent paragraphs will reveal your position and argumentation. It is good if you have a personal opinion about the chosen topic. But the best way to start an argumentative essay is to find evidence that you are right. You cannot claim anything without support, so consider collecting all the data that will prove you are right.

2: Research & organize your findings

How to write a good argumentative essay? Your paper should be compelling and supported with facts. Do your research and take notes. You might want to highlight individual quotes or even paragraphs. And you should organize your findings. Save and organize all the trusted sources that you use while working.

Search for a hook for an argumentative essay. You should also work on your arguments and counterarguments. It's like chess because you need to think about the strategy a few moves ahead. Another aspect is impartiality. Your essay may contradict certain authors' work, or it may run counter to generally accepted standards.

But you shouldn't include an emotional component. Try to describe the problems and argue your position neutrally. Sometimes research requires a non-standard approach. Perhaps you should look at the problem from a different angle and pay attention to what has gone unnoticed by other people.

3: Draft a structure

The correct structure of an argumentative essay is the most important aspect. Without this, your work may be in vain. There are key steps and points to help your paper be compelling and logical.

First Paragraph

How to make an argumentative essay catchy? You need to grab attention with good background and a thesis statement. Your first paragraph is where you should formulate your idea and position, which will gradually unfold in other parts of the paper. The main challenge is to meet all academic requirements. But you can start with certain data or research findings that can be a compelling start to uncover the subject further.

After disclosing the background, you need to provide a few key questions that will be fundamental to you. In the future, you will need to give exhaustive answers in each of the paragraphs.

- Why is your chosen subject relevant?

- What is the problem, and how to solve it?

- Is this important in the context of your research?

- What should be done to solve the problem?

- Are there any root causes that made this subject relevant?

If the chosen topic involves statistics, then you can post them to show the significance of the problem or the relevance of your paper and all the arguments.

Body Paragraphs

Every argument of fact essay must be based on evidence. It's best if you reserve each paragraph for a specific aspect worth mentioning. Start with the statement. Uncover the root cause of your claim, which real data in the future will back up. You have to provide clear and structured evidence because your statements are meaningless without this.

Indicate the data that you received as a result of the research. In any case, you should only rely on reliable and trustworthy sources. For example, it is better to accompany some legal statements with references to legislation or certain amendments. There are many tips for argumentative essay tasks, and they are all closely related to the search for evidence. This is why you need to provide facts and explain how this can make your case persuasive.

Another important point concerns the connection of the main paragraphs with your thesis. If your paper has clear goals and arguments, then the structure of each block should be interconnected. This is necessary in order to maintain a logical consistency and expand your topic .

Additional Paragraphs

Almost any argument can have a counterargument. That is why you need additional paragraphs to address all the controversial aspects. But how to write an argumentative essay and not get confused by your evidence structure? Examine the subject and collect all the main arguments.

Next, you need to study opposing opinions and familiarize yourself with the evidence base. If you have clear confirmation of your case, then you can provide data, a quote from the research, and strengthen your thesis. In other words, you must be ready for the opposite opinion and have proof of your case.

This is the logical ending where you need to try to be as convincing as possible. Summarize everything you have written about up to this point. Perhaps you need to add a call to action or provide hypotheses. This type of assignment involves adding real-life examples to prove the strength of your arguments in action. You can also speculate about how your ideas might affect a subject or a specific problem.

Final Words

Any argumentative essay takes a lot of research time. You can't just take key aspects of a subject and question them. All your statements should be based not only on personal feelings and judgments. Study everything that is important and present the most convincing arguments.

You should also follow the plan clearly and adhere to all formatting requirements. Do not exceed the allowed word count. Try to be as concise as possible, but remember to be convincing. When all of your arguments are supported by credible sources or research results, then your essay can be considered a success.

And do not forget that grammatical or spelling mistakes are not allowed. You need to pay extra attention to the accuracy of the wording to be more convincing. Then your arguments will be understandable and more weighty.

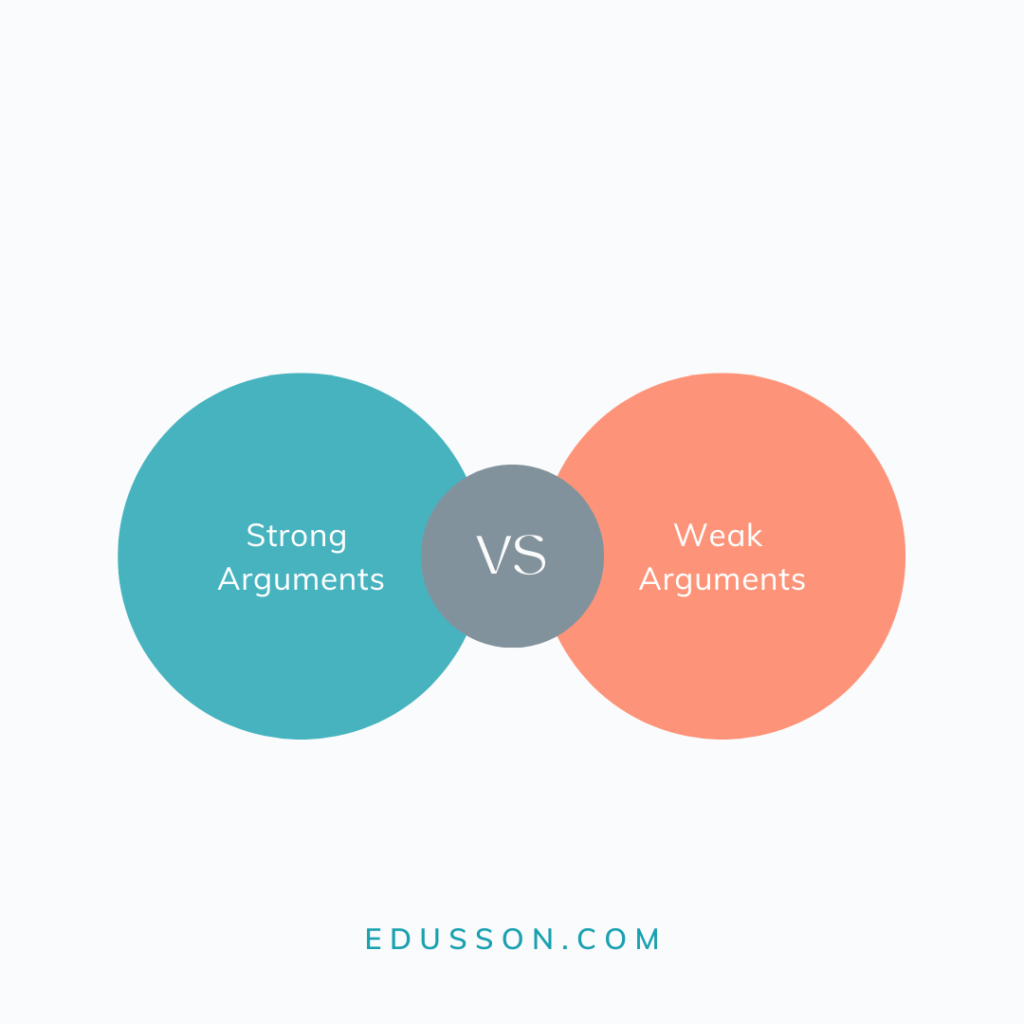

How to Distinguish a Strong Argument from Weak

How to differentiate a strong argument from weak argument can be confusing if you do not know the criteria that is used for it. The differentiation is very similar to what is obtainable in the soundness for a deductive argument.

A strong argument that has true proof or premises is considered cogent. When an essay writing is said to be cogent, it means that the argument is very good and believable with strong evidence to back up the conclusion. A weak argument is not cogent because is not true and has premises that is false.

College coursework help can be beneficial to students who struggle with using arguments in their essays; they can use guides to learn more about deductive or inductive reasoning, and gain an understanding of how to write an essay effectively.

Inductive vs Deductive

When it comes to deductive reasoning, the essay writer may want to give information or premises that will be able to proven in conclusion. However, inductive reasoning or logic is totally based on conclusion that is taken generally from behavior in some cases. Deductive reasoning can be invalid or valid. For those who are making use of inductive reasoning, it can be wrong even if the premises that was used is correct.

If you are taking arguments based on deductive logic and reasoning, they can either be invalid or valid. When it comes to invalid arguments, you should know that they are unsound or weak. Valid arguments are known to be very sound when the premises is true. Arguments based on inductive reasoning can either be weak or strong. The weak argument is not convent but strong arguments are strong if only the premises is true.

Essay hacks will help you understand what a strong argument is and what you need to make a weak argument strong. An argument can be defined as a type of communication that is able or tries to convince or persuade a person or an audience to accept a topic.

Argument have three parts:

- Claim- this talks about the position that has to be argued.

- Reason- this explains logically why the claim should be valid.

- Evidence – the evidence comes with expert testimony, statistics, examples and lots more.

Strong argument

A strong argument is solely based upon reasons, facts and figures that can be proven without reasonable doubts.

Weak argument

A series of facts that are based on personal beliefs that may not true if investigated deeply.

Moreover, utilizing some essay hacks may help you put your argument into a convincing presentation that will make a strong impact on your audience. To make sure you do that, you may even consider working with a presentation writing service to make sure your communication will be delivered in the most effective way.

How to Differentiate a Strong Argument From Week?

Strong Arguments

The essay form of a strong argument always begins with opinions and facts about the subject. Relevant opinions and facts are given to back the argument. The arguments are logically arranged and clear to understand.

Weak Arguments

Weak arguments are not back by proven opinions or facts. Most times, the argument for a particular topic is watery or weak to be supported by a large number of people. If you must differentiate what is a strong or weak argument, it is critics that you carefully see through what is written by a writer. You will have to read between the lines to ensure that you know what the writer is talking about. This will help you understand if the argument is strong or weak.

Weak Evidence vs Strong Evidence

A strong reason or claim requires a writer to come up with evidence that are strong and trustworthy. The evidence must be convincing and relevant to what is been argued upon. While a weak evidence cannot be supported in a lot of places because it is not convincing and has no backing when it is researched. How to differentiate a strong argument from a weak argument can be easily noticed if the above facts are taken into consideration. Essay conclusion in differentiating the two arguments should be concluded in a simple and clear manner that will help the reader understand the type of argument that is placed before them.

In conclusion, distinguishing between a strong argument and a weak one is crucial for effectively communicating ideas and convincing others. To improve your argumentative skills, take note of logical fallacies, gather credible evidence, address opposing viewpoints, and present your ideas clearly and concisely. However, if you still find it difficult, you ask to write an argumentative essay for me or can seek assistance from professionals who can guide you through the process and help you develop a strong and convincing argument.

Related posts:

- Effective Ways to Improve Creativity

How to Write a Synthesis Essay

- How to Use Sentence Starters for Essays

- How to Write a Hook for your Essay or Paper [Examples Included]

Improve your writing with our guides

Writing a Great Research Summary and where to Get Help on it

How To Write A Process Essay: Essay Outline, Tips, Topics and Essay Help

Get 15% off your first order with edusson.

Connect with a professional writer within minutes by placing your first order. No matter the subject, difficulty, academic level or document type, our writers have the skills to complete it.

100% privacy. No spam ever.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Understanding Argument

Angie Smibert

Introduction

Where can you find the best tacos in Texas? Who wrote the best version of the song “Wagon Wheel”? Which cause is most deserving of a federal grant? While all of these topics seem like fodder for a happy hour conversation, each one can be proven with specifically defined criteria and evidence. And while the word argument conjures up negative memories for some, in rhetoric we use the term to refer to a persuasive essay. In this section, we introduce you to the concepts surrounding argumentation and discuss two of the more prominent methodologies used today.

Features of an Argument

Argument is not the loud, assertive, unwavering statement of your opinion in the hopes of conquering the opposition. Argument is the careful consideration of numerous positions and the careful development of logically sound, carefully constructed assertions that, when combined, offer a worthwhile perspective in an ongoing debate. Certainly you want to imagine yourself arguing with others—and certainly you want to believe your opinion has superior qualities to theirs—but the purpose of argument in the college setting is not to solve a practical problem or shut down a conversation. Rather, it’s to illuminate, expand, and further inform a debate happening on a worthwhile subject between reasonable, intelligent people. In other words, calling the opposition stupid is not good argument, it’s an ad hominem attack. For a review of other logical fallacies, refer to section 3 of this text. Some of the key tools of argument are the strategies that students are asked to consider when doing a Rhetorical Analysis. Before beginning an argument of your own, review the basic concepts of rhetorical appeals from the Rhetorical Analysis Chapter. As you plan and draft your own argument, carefully use the following elements of rhetoric to your own advantage.

Approaches to Argument

A well-structured argument is one that is carefully and optimally planned. It is organized so that the argument has a continuous building of ideas, one upon the other or in concert with the other, in order to produce the most persuasive impact or effect on the reader. For clarity, avoid repeating ideas, reasons, or evidence. Instead, consider how each idea in your argument connects to the others. Should some ideas come before others? Should you build your reasons from simple to complex or from complex to simple? Should you present the counterargument before your reasons? Or, would it make more sense for you to present your reasons and then the concessions and rebuttals? How can you use clear transitional phrases to facilitate reader comprehension of your argument? Consider these questions while constructing and revising your argument.

Simple to Complex/Complex to Simple

Whether structuring a paragraph or a research paper, the simple to complex (or reverse) method can be an effective way to build cohesion throughout your writing. Just as the phrase implies, simple to complex is when a writer introduces a simple concept then builds upon it to heighten interest. Sometimes, the opposite structure works to move the reader through your position. For example, if you choose to write on the topic of pollution as it impacts the world, you might begin with the concept of straws and sea turtles. Your simple topic of sea turtles swallowing straws thrown away might then move to the complex issues of consumption, consumerism and disposal. Conversely, if you begin with the broad, complex topic of consumerism, you could then move to the story of the sea turtles as a way of building pathos in the reader. Whichever method you choose, make sure that the relationship between the topics is logical and clear so that readers find validity in your position.

Cause/Effect

The cause/effect method is a way of establishing a reason, or reasons, why something has occurred. For example, if you live in south Texas, then you understand the problem that mosquitoes cause in the hot, humid summer months. While there is no way to eliminate all mosquitoes, there are ways to minimize their growth in your backyard. If you research the ways in which mosquitoes are born, you would understand the importance of things such as emptying containers of all stagnant water so that they cannot incubate or keeping your grass mowed to eliminate areas for them to populate. The process by which you go through to determine the cause of mosquito infestations is the cause and effect method. In argumentation, you might use this method to support a claim for community efforts to prevent mosquitoes from growing in your neighborhood. Demonstrating that process is effective for a logos based argument.

Chronological

Sometimes an argument is presented best when a sequential pattern is used. Oftentimes, that pattern will be based on the pattern of time in which the sequence occurs. For example, if you are writing an argumentative essay in which you are calling for a new stop light to be installed at a busy intersection, you might utilize a chronological structure to demonstrate the rate of increased accidents over a given period of time at that intersection. If your pattern demonstrates a marked increase in accidents, then your data would show a logical reason for supporting your position. Oftentimes, a chronological pattern involves steps indicated by signal words such as first, next, and finally. Utilizing this pattern will walk readers through your line of reasoning and guide them towards reaching your proposed conclusion.

Another method for organizing your writing is by order of importance. This method is often referred to as emphatic because organization is done based upon emphasis. The direction you choose to go is yours whether you begin with the strongest, most important point of your argument, or the weakest. In either case, the hierarchy of ideas should be clear to readers. The emphatic method is often subjective based upon the writer’s beliefs. If, for example, you want to build an argument for a new rail system to be used in your city, you will have to decide which reason is most important and which is simply support material. For one writer, the decrease in the number of cars on the road might be the most important aspect as it would result in a reduction of toxic emissions. For another writer, the time saved for commuters might be the most important aspect. The decision to start with your strongest or weakest point is one of style.

Style/ Eloquence

When we discuss style in academic writing, we generally mean the use of formal language appropriate for the given academic audience and occasion. Academics generally favor Standard American English and the use of precise language that avoids idioms, clichés, or dull, simple word choices. This is not to imply that these tropes are not useful; however, strong academic writing is typically objective and frequently avoids the use of first-person pronouns unless the disciplinary style and conventions suggest otherwise.

Some writing assignments allow you to choose your audience. In that case, the style in which you write may not be the formal, precise Standard American English that the academy prefers. For some writing assignments, you may even be asked to use, where appropriate, poetic or figurative language or language that evokes the senses.

In all cases, it is important to understand what style of writing your audience expects, as delivering your argument in that style could make it more persuasive.

Basic Structure and Content of Argument

When you are tasked with crafting an argumentative essay, it is likely that you will be expected to craft your argument based upon a given number of sources–all of which should support your topic in some way. Your instructor might provide these sources for you, ask you to locate these sources, or provide you with some sources and ask you to find others. Whether or not you are asked to do additional research, an argumentative essay should be comprised of the following basic components.

Claim: What do you want the reader to believe?

In an argument paper, the thesis is often called a claim. This claim is a statement in which you take a stand on a debatable issue. A strong, debatable claim has at least one valid counterargument, an opposite or alternative point of view, that is as sensible as the position that you take in your claim. In your thesis statement, you should clearly and specifically state the position you will convince your audience to adopt. You can accomplish this via either a closed or open thesis statement.

A closed thesis statement includes sub-claims or reasons why you choose to support your claim.

For example: ● The city of Houston has displayed a commitment to attracting new residents by making improvements to its walkability, city centers, and green spaces.

In this instance, walkability, city centers, and green spaces are the sub-claims, or reasons, why you would make the claim that Houston is attracting new residents.

An open thesis statement does not include sub-claims and might be more appropriate when your argument is less easy to prove with two or three easily-defined sub-claims.

For example: ● The city of Houston is a vibrant metropolis due to its walkability, city centers, and green spaces.

The choice between an open or a closed thesis statement often depends upon the complexity of your argument. When in doubt about how to structure your thesis statement, seek the advice of your instructor or a writing center consultant.

A note on context:

What background information about the topic does your audience need.

Before you get into defending your claim, you will need to place your topic (and argument) into context by including relevant background material. Remember, your audience is relying on you for vital information such as definitions, historical placement, and controversial positions. This background material might appear in either your introductory paragraph(s) or your body paragraphs. How and where to incorporate background material depends a lot upon your topic, assignment, evidence, and audience.

Evidence or Grounds: What makes your reasoning valid?

To validate the thinking that you put forward in your claim and subclaims, you need to demonstrate that your reasoning is based on more than just your personal opinion. Evidence, sometimes referred to as grounds, can take the form of research studies or scholarship, expert opinions, personal examples, observations made by yourself or others, or specific instances that make your reasoning seem sound and believable. Evidence only works if it directly supports your reasoning — and sometimes you must explain how the evidence supports your reasoning (do not assume that a reader can see the connection between evidence and reason that you see).

Warrants: Why should a reader accept your claim?