BLOG | PODCAST NETWORK | ADMIN. MASTERMIND | SWAG & MERCH | ONLINE TRAINING

- Meet the Team

- Join the Team

- Our Philosophy

- Teach Better Mindset

- Custom Professional Development

- Livestream Shows & Videos

- Administrator Mastermind

- Academy Online Courses

- EDUcreator Club+

- Podcast Network

- Speakers Network

- Free Downloads

- Ambassador Program

- Free Facebook Group

- Professional Development

- Request Training

- Speakers Network Home

- Keynote Speakers

Strategies to Increase Critical Thinking Skills in students

Teach Better Team October 2, 2019 Blog , Engage Better , Lesson Plan Better , Personalize Student Learning Better

In This Post:

- The importance of helping students increase critical thinking skills.

- Ways to promote the essential skills needed to analyze and evaluate.

- Strategies to incorporate critical thinking into your instruction.

We ask our teachers to be “future-ready” or say that we are teaching “for jobs that don’t exist yet.” These are powerful statements. At the same time, they give teachers the impression that we have to drastically change what we are doing .

So how do we plan education for an unknown job market or unknown needs?

My answer: We can’t predict the jobs, but whatever they are, students will need to think critically to do them. So, our job is to teach our students HOW to think, not WHAT to think.

Helping Students Become Critical Thinkers

My answer is rooted in the call to empower our students to be critical thinkers. I believe that to be critical thinkers, educators need to provide students with the strategies they need. And we need to ask more than just surface-level questions.

Questions to students must motivate them to dig up background knowledge. They should inspire them to make connections to real-world scenarios. These make the learning more memorable and meaningful.

Critical thinking is a general term. I believe this term means that students effectively identify, analyze, and evaluate content or skills. In this process, they (the students) will discover and present convincing reasons in support of their answers or thinking.

You can look up critical thinking and get many definitions like this one from Wikipedia: “ Critical thinking consists of a mental process of analyzing or evaluating information, particularly statements or propositions that people have offered as true. ”

Essential Skills for Critical Thinking

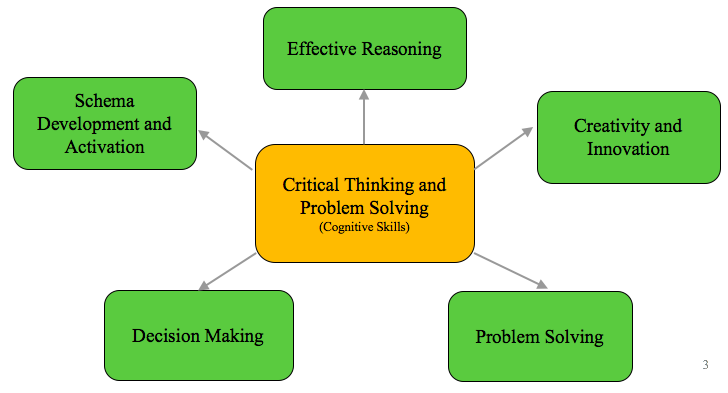

In my current role as director of curriculum and instruction, I work to promote the use of 21st-century tools and, more importantly, thinking skills. Some essential skills that are the basis for critical thinking are:

- Communication and Information skills

- Thinking and Problem-Solving skills

- Interpersonal and Self- Directional skills

- Collaboration skills

These four bullets are skills students are going to need in any field and in all levels of education. Hence my answer to the question. We need to teach our students to think critically and for themselves.

One of the goals of education is to prepare students to learn through discovery . Providing opportunities to practice being critical thinkers will assist students in analyzing others’ thinking and examining the logic of others.

Understanding others is an essential skill in collaboration and in everyday life. Critical thinking will allow students to do more than just memorize knowledge.

Ask Questions

So how do we do this? One recommendation is for educators to work in-depth questioning strategies into a lesson launch.

Ask thoughtful questions to allow for answers with sound reasoning. Then, word conversations and communication to shape students’ thinking. Quick answers often result in very few words and no eye contact, which are skills we don’t want to promote.

When you are asking students questions and they provide a solution, try some of these to promote further thinking:

- Could you elaborate further on that point?

- Will you express that point in another way?

- Can you give me an illustration?

- Would you give me an example?

- Will you you provide more details?

- Could you be more specific?

- Do we need to consider another point of view?

- Is there another way to look at this question?

Utilizing critical thinking skills could be seen as a change in the paradigm of teaching and learning. Engagement in education will enhance the collaboration among teachers and students. It will also provide a way for students to succeed even if the school system had to start over.

[scroll down to keep reading]

Promoting critical thinking into all aspects of instruction.

Engagement, application, and collaboration are skills that withstand the test of time. I also promote the integration of critical thinking into every aspect of instruction.

In my experience, I’ve found a few ways to make this happen.

Begin lessons/units with a probing question: It shouldn’t be a question you can answer with a ‘yes’ or a ‘no.’ These questions should inspire discovery learning and problem-solving.

Encourage Creativity: I have seen teachers prepare projects before they give it to their students many times. For example, designing snowmen or other “creative” projects. By doing the design work or by cutting all the circles out beforehand, it removes creativity options.

It may help the classroom run more smoothly if every child’s material is already cut out, but then every student’s project looks the same. Students don’t have to think on their own or problem solve.

Not having everything “glue ready” in advance is a good thing. Instead, give students all the supplies needed to create a snowman, and let them do it on their own.

Giving independence will allow students to become critical thinkers because they will have to create their own product with the supplies you give them. This might be an elementary example, but it’s one we can relate to any grade level or project.

Try not to jump to help too fast – let the students work through a productive struggle .

Build in opportunities for students to find connections in learning. Encouraging students to make connections to a real-life situation and identify patterns is a great way to practice their critical thinking skills. The use of real-world scenarios will increase rigor, relevance, and critical thinking.

A few other techniques to encourage critical thinking are:

- Use analogies

- Promote interaction among students

- Ask open-ended questions

- Allow reflection time

- Use real-life problems

- Allow for thinking practice

Critical thinking prepares students to think for themselves for the rest of their lives. I also believe critical thinkers are less likely to go along with the crowd because they think for themselves.

About Matthew X. Joseph, Ed.D.

Dr. Matthew X. Joseph has been a school and district leader in many capacities in public education over his 25 years in the field. Experiences such as the Director of Digital Learning and Innovation in Milford Public Schools (MA), elementary school principal in Natick, MA and Attleboro, MA, classroom teacher, and district professional development specialist have provided Matt incredible insights on how to best support teaching and learning. This experience has led to nationally publishing articles and opportunities to speak at multiple state and national events. He is the author of Power of Us: Creating Collaborative Schools and co-author of Modern Mentoring , Reimagining Teacher Mentorship (Due out, fall 2019). His master’s degree is in special education and his Ed.D. in Educational Leadership from Boston College.

Visit Matthew’s Blog

- Featured Articles

- Report Card Comments

- Needs Improvement Comments

- Teacher's Lounge

- New Teachers

- Our Bloggers

- Article Library

- Featured Lessons

- Every-Day Edits

- Lesson Library

- Emergency Sub Plans

- Character Education

- Lesson of the Day

- 5-Minute Lessons

- Learning Games

- Lesson Planning

- Subjects Center

- Teaching Grammar

- Leadership Resources

- Parent Newsletter Resources

- Advice from School Leaders

- Programs, Strategies and Events

- Principal Toolbox

- Administrator's Desk

- Interview Questions

- Professional Learning Communities

- Teachers Observing Teachers

- Tech Lesson Plans

- Science, Math & Reading Games

- Tech in the Classroom

- Web Site Reviews

- Creating a WebQuest

- Digital Citizenship

- All Online PD Courses

- Child Development Courses

- Reading and Writing Courses

- Math & Science Courses

- Classroom Technology Courses

- A to Z Grant Writing Courses

- Spanish in the Classroom Course

- Classroom Management

- Responsive Classroom

- Dr. Ken Shore: Classroom Problem Solver

- Worksheet Library

- Highlights for Children

- Venn Diagram Templates

- Reading Games

- Word Search Puzzles

- Math Crossword Puzzles

- Geography A to Z

- Holidays & Special Days

- Internet Scavenger Hunts

- Student Certificates

Newsletter Sign Up

Search form

Strategies for encouraging critical thinking skills in students.

With kids today dealing with information overload, the ability to think critically has become a forgotten skill. But critical thinking skills enable students to analyze, evaluate, and apply information, fostering their ability to solve complex problems and make informed decisions. So how do we bridge that gap?

As educators, we need to use more strategies that promote critical thinking in our students. These seven strategies can help students cultivate their critical thinking skills. (These strategies can be modified for all students with the aid of a qualified educator.)

1. Encourage Questioning

One of the fundamental pillars of critical thinking is curiosity. Encourage students to ask questions about the subject matter and challenge existing assumptions. Create a safe and supportive environment where students feel comfortable expressing their thoughts and ideas. By nurturing their inquisitive nature, you can stimulate critical thinking and empower students to explore different perspectives.

2. Foster Discussions

Engage students in meaningful discussions that require them to examine various viewpoints. Encourage active participation, respectful listening, and constructive criticism. Assign topics that involve controversial and current issues, enabling students to analyze arguments, provide evidence, and formulate their own conclusions in a safe environment.

By engaging in intellectual discourse, students refine their critical thinking skills while honing their ability to articulate and defend their positions. And remember to offer sentence starters for ELD students to feel successful and included in the process, such as:

- "I felt the character Wilbur was a good friend to Charlotte because..."

- "I felt the character Wilbur was not a good friend to Charlotte because..."

3. Teach Information Evaluation

In the age of readily available information, students must be able to evaluate sources. Teach your students how to assess information's credibility, bias, and relevance. Encourage them to cross-reference multiple sources and identify reliable and reputable resources.

Emphasize the importance of distinguishing fact from opinion and encourage students to question the validity of claims. Providing students with tools and frameworks for information evaluation equips them to make informed judgments and enhances their critical thinking abilities.

4. Incorporate Problem-Solving Activities

Integrate problem-solving activities into your curriculum to foster critical thinking skills. Provide students with real-world scenarios that require analysis, synthesis, and decision-making. These activities can include case studies, group projects, or simulations.

Encourage students to break down complex problems into manageable parts, consider alternative solutions, and evaluate the potential outcomes. Students will begin to develop their critical thinking skills and apply their knowledge to practical situations by engaging in problem-solving activities.

5. Promote Reflection and Metacognition

Allocate time for reflection and metacognitive (an understanding of one's thought process) practices. Encourage students to review their thinking processes and reflect on their learning experiences. For example, what went right and/or wrong helps students evaluate the learning process.

Provide prompts that help your students analyze their reasoning, identify biases, and recognize areas for improvement. Journaling, self-assessments, and group discussions can facilitate this reflective process. By engaging in metacognition, students become more aware of their thinking patterns and develop strategies to enhance their critical thinking abilities.

6. Encourage Creative Thinking

Creativity and critical thinking go hand in hand. Encourage students to think creatively by incorporating open-ended tasks and projects. Assign projects requiring them to think outside the box, develop innovative solutions, and analyze potential risks and benefits. Emphasize the value of brainstorming, divergent thinking, and considering multiple perspectives. By nurturing creative thinking, students develop the ability to approach problems from unique angles, fostering their critical thinking skills.

7. Provide Scaffolding and Support

Recognize that critical thinking is a developmental process. Provide scaffolding and support as students build their critical thinking skills. This strategy is especially important for students needing additional help as outlined in their IEP or 504.

Offer guidance, modeling, and feedback to help students navigate complex tasks. Gradually increase the complexity of assignments and provide opportunities for independent thinking and decision-making. By offering appropriate support, you empower students to develop their critical thinking skills while building their confidence and independence.

Implement Critical Thinking Strategies Now

Cultivating critical thinking skills in your students is vital for their academic success and their ability to thrive in an ever-changing world. By implementing various strategies, educators can foster an environment that nurtures critical thinking skills. As students develop these skills, they become active learners who can analyze, evaluate, and apply knowledge effectively, enabling them to tackle challenges and make informed decisions throughout their lives.

EW Lesson Plans

EW Professional Development

Ew worksheets.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter and receive top education news, lesson ideas, teaching tips and more! No thanks, I don't need to stay current on what works in education! COPYRIGHT 1996-2016 BY EDUCATION WORLD, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COPYRIGHT 1996 - 2024 BY EDUCATION WORLD, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Helping Students Hone Their Critical Thinking SkillsUsed consistently, these strategies can help middle and high school teachers guide students to improve much-needed skills.  Critical thinking skills are important in every discipline, at and beyond school. From managing money to choosing which candidates to vote for in elections to making difficult career choices, students need to be prepared to take in, synthesize, and act on new information in a world that is constantly changing. While critical thinking might seem like an abstract idea that is tough to directly instruct, there are many engaging ways to help students strengthen these skills through active learning. Make Time for Metacognitive ReflectionCreate space for students to both reflect on their ideas and discuss the power of doing so. Show students how they can push back on their own thinking to analyze and question their assumptions. Students might ask themselves, “Why is this the best answer? What information supports my answer? What might someone with a counterargument say?” Through this reflection, students and teachers (who can model reflecting on their own thinking) gain deeper understandings of their ideas and do a better job articulating their beliefs. In a world that is go-go-go, it is important to help students understand that it is OK to take a breath and think about their ideas before putting them out into the world. And taking time for reflection helps us more thoughtfully consider others’ ideas, too. Teach Reasoning SkillsReasoning skills are another key component of critical thinking, involving the abilities to think logically, evaluate evidence, identify assumptions, and analyze arguments. Students who learn how to use reasoning skills will be better equipped to make informed decisions, form and defend opinions, and solve problems. One way to teach reasoning is to use problem-solving activities that require students to apply their skills to practical contexts. For example, give students a real problem to solve, and ask them to use reasoning skills to develop a solution. They can then present their solution and defend their reasoning to the class and engage in discussion about whether and how their thinking changed when listening to peers’ perspectives. A great example I have seen involved students identifying an underutilized part of their school and creating a presentation about one way to redesign it. This project allowed students to feel a sense of connection to the problem and come up with creative solutions that could help others at school. For more examples, you might visit PBS’s Design Squad , a resource that brings to life real-world problem-solving. Ask Open-Ended QuestionsMoving beyond the repetition of facts, critical thinking requires students to take positions and explain their beliefs through research, evidence, and explanations of credibility. When we pose open-ended questions, we create space for classroom discourse inclusive of diverse, perhaps opposing, ideas—grounds for rich exchanges that support deep thinking and analysis. For example, “How would you approach the problem?” and “Where might you look to find resources to address this issue?” are two open-ended questions that position students to think less about the “right” answer and more about the variety of solutions that might already exist. Journaling, whether digitally or physically in a notebook, is another great way to have students answer these open-ended prompts—giving them time to think and organize their thoughts before contributing to a conversation, which can ensure that more voices are heard. Once students process in their journal, small group or whole class conversations help bring their ideas to life. Discovering similarities between answers helps reveal to students that they are not alone, which can encourage future participation in constructive civil discourse. Teach Information LiteracyEducation has moved far past the idea of “Be careful of what is on Wikipedia, because it might not be true.” With AI innovations making their way into classrooms, teachers know that informed readers must question everything. Understanding what is and is not a reliable source and knowing how to vet information are important skills for students to build and utilize when making informed decisions. You might start by introducing the idea of bias: Articles, ads, memes, videos, and every other form of media can push an agenda that students may not see on the surface. Discuss credibility, subjectivity, and objectivity, and look at examples and nonexamples of trusted information to prepare students to be well-informed members of a democracy. One of my favorite lessons is about the Pacific Northwest tree octopus . This project asks students to explore what appears to be a very real website that provides information on this supposedly endangered animal. It is a wonderful, albeit over-the-top, example of how something might look official even when untrue, revealing that we need critical thinking to break down “facts” and determine the validity of the information we consume. A fun extension is to have students come up with their own website or newsletter about something going on in school that is untrue. Perhaps a change in dress code that requires everyone to wear their clothes inside out or a change to the lunch menu that will require students to eat brussels sprouts every day. Giving students the ability to create their own falsified information can help them better identify it in other contexts. Understanding that information can be “too good to be true” can help them identify future falsehoods. Provide Diverse PerspectivesConsider how to keep the classroom from becoming an echo chamber. If students come from the same community, they may have similar perspectives. And those who have differing perspectives may not feel comfortable sharing them in the face of an opposing majority. To support varying viewpoints, bring diverse voices into the classroom as much as possible, especially when discussing current events. Use primary sources: videos from YouTube, essays and articles written by people who experienced current events firsthand, documentaries that dive deeply into topics that require some nuance, and any other resources that provide a varied look at topics. I like to use the Smithsonian “OurStory” page , which shares a wide variety of stories from people in the United States. The page on Japanese American internment camps is very powerful because of its first-person perspectives. Practice Makes PerfectTo make the above strategies and thinking routines a consistent part of your classroom, spread them out—and build upon them—over the course of the school year. You might challenge students with information and/or examples that require them to use their critical thinking skills; work these skills explicitly into lessons, projects, rubrics, and self-assessments; or have students practice identifying misinformation or unsupported arguments. Critical thinking is not learned in isolation. It needs to be explored in English language arts, social studies, science, physical education, math. Every discipline requires students to take a careful look at something and find the best solution. Often, these skills are taken for granted, viewed as a by-product of a good education, but true critical thinking doesn’t just happen. It requires consistency and commitment. In a moment when information and misinformation abound, and students must parse reams of information, it is imperative that we support and model critical thinking in the classroom to support the development of well-informed citizens. Classroom Q&AWith larry ferlazzo. In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog. Integrating Critical Thinking Into the Classroom

(This is the second post in a three-part series. You can see Part One here .) The new question-of-the-week is: What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom? Part One ‘s guests were Dara Laws Savage, Patrick Brown, Meg Riordan, Ph.D., and Dr. PJ Caposey. Dara, Patrick, and Meg were also guests on my 10-minute BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here. Today, Dr. Kulvarn Atwal, Elena Quagliarello, Dr. Donna Wilson, and Diane Dahl share their recommendations. ‘Learning Conversations’Dr. Kulvarn Atwal is currently the executive head teacher of two large primary schools in the London borough of Redbridge. Dr. Atwal is the author of The Thinking School: Developing a Dynamic Learning Community , published by John Catt Educational. Follow him on Twitter @Thinkingschool2 : In many classrooms I visit, students’ primary focus is on what they are expected to do and how it will be measured. It seems that we are becoming successful at producing students who are able to jump through hoops and pass tests. But are we producing children that are positive about teaching and learning and can think critically and creatively? Consider your classroom environment and the extent to which you employ strategies that develop students’ critical-thinking skills and their self-esteem as learners. Development of self-esteem One of the most significant factors that impacts students’ engagement and achievement in learning in your classroom is their self-esteem. In this context, self-esteem can be viewed to be the difference between how they perceive themselves as a learner (perceived self) and what they consider to be the ideal learner (ideal self). This ideal self may reflect the child that is associated or seen to be the smartest in the class. Your aim must be to raise students’ self-esteem. To do this, you have to demonstrate that effort, not ability, leads to success. Your language and interactions in the classroom, therefore, have to be aspirational—that if children persist with something, they will achieve. Use of evaluative praise Ensure that when you are praising students, you are making explicit links to a child’s critical thinking and/or development. This will enable them to build their understanding of what factors are supporting them in their learning. For example, often when we give feedback to students, we may simply say, “Well done” or “Good answer.” However, are the students actually aware of what they did well or what was good about their answer? Make sure you make explicit what the student has done well and where that links to prior learning. How do you value students’ critical thinking—do you praise their thinking and demonstrate how it helps them improve their learning? Learning conversations to encourage deeper thinking We often feel as teachers that we have to provide feedback to every students’ response, but this can limit children’s thinking. Encourage students in your class to engage in learning conversations with each other. Give as many opportunities as possible to students to build on the responses of others. Facilitate chains of dialogue by inviting students to give feedback to each other. The teacher’s role is, therefore, to facilitate this dialogue and select each individual student to give feedback to others. It may also mean that you do not always need to respond at all to a student’s answer. Teacher modelling own thinking We cannot expect students to develop critical-thinking skills if we aren’t modeling those thinking skills for them. Share your creativity, imagination, and thinking skills with the students and you will nurture creative, imaginative critical thinkers. Model the language you want students to learn and think about. Share what you feel about the learning activities your students are participating in as well as the thinking you are engaging in. Your own thinking and learning will add to the discussions in the classroom and encourage students to share their own thinking. Metacognitive questioning Consider the extent to which your questioning encourages students to think about their thinking, and therefore, learn about learning! Through asking metacognitive questions, you will enable your students to have a better understanding of the learning process, as well as their own self-reflections as learners. Example questions may include:

‘Adventures of Discovery’Elena Quagliarello is the senior editor of education for Scholastic News , a current events magazine for students in grades 3–6. She graduated from Rutgers University, where she studied English and earned her master’s degree in elementary education. She is a certified K–12 teacher and previously taught middle school English/language arts for five years: Critical thinking blasts through the surface level of a topic. It reaches beyond the who and the what and launches students on a learning journey that ultimately unlocks a deeper level of understanding. Teaching students how to think critically helps them turn information into knowledge and knowledge into wisdom. In the classroom, critical thinking teaches students how to ask and answer the questions needed to read the world. Whether it’s a story, news article, photo, video, advertisement, or another form of media, students can use the following critical-thinking strategies to dig beyond the surface and uncover a wealth of knowledge. A Layered Learning Approach Begin by having students read a story, article, or analyze a piece of media. Then have them excavate and explore its various layers of meaning. First, ask students to think about the literal meaning of what they just read. For example, if students read an article about the desegregation of public schools during the 1950s, they should be able to answer questions such as: Who was involved? What happened? Where did it happen? Which details are important? This is the first layer of critical thinking: reading comprehension. Do students understand the passage at its most basic level? Ask the Tough Questions The next layer delves deeper and starts to uncover the author’s purpose and craft. Teach students to ask the tough questions: What information is included? What or who is left out? How does word choice influence the reader? What perspective is represented? What values or people are marginalized? These questions force students to critically analyze the choices behind the final product. In today’s age of fast-paced, easily accessible information, it is essential to teach students how to critically examine the information they consume. The goal is to equip students with the mindset to ask these questions on their own. Strike Gold The deepest layer of critical thinking comes from having students take a step back to think about the big picture. This level of thinking is no longer focused on the text itself but rather its real-world implications. Students explore questions such as: Why does this matter? What lesson have I learned? How can this lesson be applied to other situations? Students truly engage in critical thinking when they are able to reflect on their thinking and apply their knowledge to a new situation. This step has the power to transform knowledge into wisdom. Adventures of Discovery There are vast ways to spark critical thinking in the classroom. Here are a few other ideas:

Critical thinking has the power to launch students on unforgettable learning experiences while helping them develop new habits of thought, reflection, and inquiry. Developing these skills prepares students to examine issues of power and promote transformative change in the world around them.  ‘Quote Analysis’Dr. Donna Wilson is a psychologist and the author of 20 books, including Developing Growth Mindsets , Teaching Students to Drive Their Brains , and Five Big Ideas for Effective Teaching (2 nd Edition). She is an international speaker who has worked in Asia, the Middle East, Australia, Europe, Jamaica, and throughout the U.S. and Canada. Dr. Wilson can be reached at [email protected] ; visit her website at www.brainsmart.org . Diane Dahl has been a teacher for 13 years, having taught grades 2-4 throughout her career. Mrs. Dahl currently teaches 3rd and 4th grade GT-ELAR/SS in Lovejoy ISD in Fairview, Texas. Follow her on Twitter at @DahlD, and visit her website at www.fortheloveofteaching.net : A growing body of research over the past several decades indicates that teaching students how to be better thinkers is a great way to support them to be more successful at school and beyond. In the book, Teaching Students to Drive Their Brains , Dr. Wilson shares research and many motivational strategies, activities, and lesson ideas that assist students to think at higher levels. Five key strategies from the book are as follows:

Below are two lessons that support critical thinking, which can be defined as the objective analysis and evaluation of an issue in order to form a judgment. Mrs. Dahl prepares her 3rd and 4th grade classes for a year of critical thinking using quote analysis . During Native American studies, her 4 th grade analyzes a Tuscarora quote: “Man has responsibility, not power.” Since students already know how the Native Americans’ land had been stolen, it doesn’t take much for them to make the logical leaps. Critical-thought prompts take their thinking even deeper, especially at the beginning of the year when many need scaffolding. Some prompts include:

Analyzing a topic from occupational points of view is an incredibly powerful critical-thinking tool. After learning about the Mexican-American War, Mrs. Dahl’s students worked in groups to choose an occupation with which to analyze the war. The chosen occupations were: anthropologist, mathematician, historian, archaeologist, cartographer, and economist. Then each individual within each group chose a different critical-thinking skill to focus on. Finally, they worked together to decide how their occupation would view the war using each skill. For example, here is what each student in the economist group wrote:

This was the first time that students had ever used the occupations technique. Mrs. Dahl was astonished at how many times the kids used these critical skills in other areas moving forward.  Thanks to Dr. Auwal, Elena, Dr. Wilson, and Diane for their contributions! Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post. Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind. You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo . Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching . Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones won’t be available until February). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column . The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications. Sign Up for EdWeek UpdateEdweek top school jobs.  Sign Up & Sign In Critical Thinking: Facilitating and Assessing the 21st Century Skills in EducationSo many times we hear our students say, “Why am I learning this?”  I believe that Critical Thinking is the spark that begins the process of authentic learning. Before going further, we must first develop an idea of what learning is… and what learning is not. So many times we hear our students say, “Why am I learning this?” The reason they ask is because they have not really experienced the full spectrum of learning, and because of this are actually not learning to a full rewarding extent! We might say they are being exposed to surface learning and not authentic (real) learning. The act of authentic learning is actually an exciting and engaging concept. It allows students to see real meaning and begin to construct their own knowledge. Critical Thinking is core to learning. It is rewarding, engaging, and life long. Without critical thinking students are left to a universe of concepts and memorization. Yes… over twelve years of mediocrity! When educators employ critical thinking in their classrooms, a whole new world of understanding is opened up. What are some reasons to facilitate critical thinking with our students? Let me begin: Ten Reasons For Student Critical Thinking in the classroom

I am excited by the spark that critical thinking ignites to support real and authentic learning in the classroom. I often wonder how much time students spend in the process of critical thinking in the classroom. I ask you to reflect on your typical school day. Are your students spending time in area of surface learning , or are they plunging into the engaging culture of deeper (real) learning? At the same time … how are you assessing your students? So many times as educators, we are bound by the standards, and we forget the importance of promoting that critical thinking process that makes our standards come alive with understanding. A culture of critical thinking is not automatic, though with intentional planning it can become a reality. Like the other 21st century skills, it must be built and continuously facilitated. Let’s take a look at how, we as educators, can do this. Ten Ways to Facilitate Student Critical Thinking in the Classroom and School

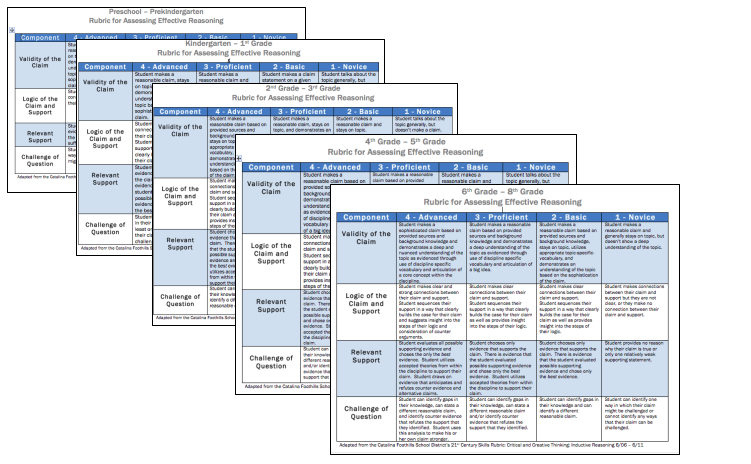

I keep talking about the idea of surface learning and deeper learning. This can best be seen in Bloom’s Taxonomy. Often we start with Remembering. This might be essential in providing students the map to the further areas of Bloom’s. Of course, we then find the idea of Understanding. This is where I believe critical thinking begins. Sometimes we need to critically think in order to understand. In fact, you might be this doing right now. I believe that too much time might be spent in Remembering, which is why students get a false idea of what learning really is. As we look at the rest of Bloom’s ( Apply, Analyze, Evaluate, and Create) we can see the deeper learning take place. and even steps toward the transfer and internalization of the learning. Some educators even tip Bloom’s upside down, stating that the Creating at the top will build an understanding. This must be done with careful facilitation and intentional scaffold to make sure there is some surface learning. After-all, Critical Thinking will need this to build on. I have been mentioning rubrics and assessment tools through out this post. To me, these are essential in building that culture of critical thinking in the classroom. I want to provide you with some great resources that will give your some powerful tools to assess the skill of Critical Thinking. Keep in mind that students can also self assess and journal using prompts from a Critical Thinking Rubric. Seven Resources to Help with Assessment and Facilitation of Critical Thinking

Critical Thinking “I Can Statements”As you can see, I believe that Critical Thinking is key to PBL, STEM, and Deeper Learning. It improves Communication and Collaboration, while promoting Creativity. I believe every student should have these following “I Can Statements” as part of their learning experience. Feel free to copy and use in your classroom. Perhaps this is a great starting place as you promote collaborative and powerful learning culture!

cross-posted at 21centuryedtech.wordpress.com Michael Gorman oversees one-to-one laptop programs and digital professional development for Southwest Allen County Schools near Fort Wayne, Indiana. He is a consultant for Discovery Education, ISTE, My Big Campus, and November Learning and is on the National Faculty for The Buck Institute for Education. His awards include district Teacher of the Year, Indiana STEM Educator of the Year and Microsoft’s 365 Global Education Hero. Read more at 21centuryedtech.wordpress.com . Tech & Learning NewsletterTools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below. What to Know About Buying a VR Headset Tech & Learning Launches “Best for Back to School” Contest How A Board Game Night For Educators Turned Out To Be The Right Move Most PopularJavaScript seems to be disabled in your browser. For the best experience on our site, be sure to turn on Javascript in your browser.

200+ Award-Winning Educational Textbooks, Activity Books, & Printable eBooks!

Reading, Writing, Math, Science, Social Studies

How To Promote Critical Thinking In Your ClassroomPromoting Thinking November 25, 2006, by The Critical Thinking Co. Staff Modeling of critical thinking skills by instructors is crucial for teaching critical thinking successfully. By making your own thought processes explicit in class - explaining your reasoning, evaluating evidence for a claim, probing the credibility of a source, or even describing what has puzzled or confused you - you provide a powerful example to students, particularly if you invite them to join in; e.g., "Can you see where we're headed with this?" "I can't think of other explanations; can you?" "This idea/principle struck me as difficult or confusing at first, but here's how I figured it out." You can encourage students to emulate this by using them in demonstrations, asking them to "think out loud" in order for classmates to observe how they reason through a problem. Develop the habit of asking questions that require students to think critically, and tell students that you really expect them to give answers! In particular, Socratic questioning encourages students to develop and clarify their thinking: e.g., "Would your answer hold in all cases?" "How would you respond to a counter-example or counter-argument?" "Explain how you arrived at that answer?" This is another skill that students can learn from your example, and can use in working with each other. Providing regular opportunities for pair or small group discussions after major points or demonstrations during lectures is also important: this allows students to process the new material, connect it to previously learned topics, and practice asking questions that promote further critical thinking. Obviously, conveying genuine respect for student input is essential. Communicating the message that you value and support student contributions and efforts to think critically increases confidence, and motivates students to continue building their thinking skills. An essential component of this process is the creation of a climate where students feel comfortable with exploring the process of reasoning through a problem without being "punished" for getting the wrong answer. Researchers have found consistently that interaction among students, in the form of well-structured group discussions plays a central role in stimulating critical thinking. Discussing course material and its applications allows students to formulate and test hypotheses, practice asking thought-provoking questions, hear other perspectives, analyze claims, evaluate evidence, and explain and justify their reasoning. As they become more sophisticated and fluent in thinking critically, students can observe and critique each others' reasoning skills. The Importance of Critical Thinking Skills for StudentsLink Copied Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on LinkedIn .jpg) Brains at Work! If you’re moving toward the end of your high school career, you’ve likely heard a lot about college life and how different it is from high school. Classes are more intense, professors are stricter, and the curriculum is more complicated. All in all, it’s very different compared to high school. Different doesn’t have to mean scary, though. If you’re nervous about beginning college and you’re worried about how you’ll learn in a place so different from high school, there are steps you can take to help you thrive in your college career. If you’re wondering how to get accepted into college and how to succeed as a freshman in such a new environment, the answer is simple: harness the power of critical thinking skills for students. What is critical thinking?Critical thinking entails using reasoning and the questioning of assumptions to address problems, assess information, identify biases, and more. It's a skillset crucial for students navigating their academic journey and beyond, including how to get accepted into college . At its crux, critical thinking for students has everything to do with self-discipline and making active decisions to 'think outside the box,' allowing individuals to think beyond a concept alone in order to understand it better. Critical thinking skills for students is a concept highly encouraged in any and every educational setting, and with good reason. Possessing strong critical thinking skills will make you a better student and, frankly, help you gain valuable life skills. Not only will you be more efficient in gathering knowledge and processing information, but you will also enhance your ability to analyse and comprehend it. Importance of critical thinking for studentsDeveloping critical thinking skills for students is essential for success at all academic levels, particularly in college. It introduces reflection and perspective while encouraging you to question what you’re learning! Even if you’ve seen solid facts. Asking questions, considering other perspectives, and self-reflection cultivate resilient students with endless potential for learning, retention, and personal growth.A well-developed set of critical thinking skills for students will help them excel in many areas. Here are some critical thinking examples for students: 1. Decision-makingIf you’re thinking critically, you’re not making impulse decisions or snap judgments; you’re taking the time to weigh the pros and cons. You’re making informed decisions. Critical thinking skills for students can make all the difference. 2. Problem-solvingStudents with critical thinking skills are more effective in problem-solving. This reflective thinking process helps you use your own experiences to ideate innovations, solutions, and decisions. 3. CommunicationStrong communication skills are a vital aspect of critical thinking for students, helping with their overall critical thinking abilities. How can you learn without asking questions? Critical thinking for students is what helps them produce the questions they may not have ever thought to ask. As a critical thinker, you’ll get better at expressing your ideas concisely and logically, facilitating thoughtful discussion, and learning from your teachers and peers. 4. Analytical skillsDeveloping analytical skills is a key component of strong critical thinking skills for students. It goes beyond study tips on reviewing data or learning a concept. It’s about the “Who? What? Where? Why? When? How?” When you’re thinking critically, these questions will come naturally, and you’ll be an expert learner because of it. How can students develop critical thinking skillsAlthough critical thinking skills for students is an important and necessary process, it isn’t necessarily difficult to develop these observational skills. All it takes is a conscious effort and a little bit of practice. Here are a few tips to get you started: 1. Never stop asking questionsThis is the best way to learn critical thinking skills for students. As stated earlier, ask questions—even if you’re presented with facts to begin with. When you’re examining a problem or learning a concept, ask as many questions as you can. Not only will you be better acquainted with what you’re learning, but it’ll soon become second nature to follow this process in every class you take and help you improve your GPA . 2. Practice active listeningAs important as asking questions is, it is equally vital to be a good listener to your peers. It is astounding how much we can learn from each other in a collaborative environment! Diverse perspectives are key to fostering critical thinking skills for students. Keep an open mind and view every discussion as an opportunity to learn. 3. Dive into your creativityAlthough a college environment is vastly different from high school classrooms, one thing remains constant through all levels of education: the importance of creativity. Creativity is a guiding factor through all facets of critical thinking skills for students. It fosters collaborative discussion, innovative solutions, and thoughtful analyses. 4. Engage in debates and discussionsParticipating in debates and discussions helps you articulate your thoughts clearly and consider opposing viewpoints. It challenges the critical thinking skills of students about the evidence presented, decoding arguments, and constructing logical reasoning. Look for debates and discussion opportunities in class, online forums, or extracurricular activities. 5. Look out for diverse sources of informationIn today's digital age, information is easily available from a variety of sources. Make it a habit to explore different opinions, perspectives, and sources of information. This not only broadens one's understanding of a subject but also helps in distinguishing between reliable and biased sources, honing the critical thinking skills of students. Unlock the power of critical thinking skills while enjoying a seamless student living experience!Book through amber today! 6. Practice problem-solvingTry engaging in challenging problems, riddles or puzzles that require critical thinking skills for students to solve. Whether it's solving mathematical equations, tackling complex scenarios in literature, or analysing data in science experiments, regular practice of problem-solving tasks sharpens your analytical skills. It enhances your ability to think critically under pressure. Nurturing critical thinking skills helps students with the tools to navigate the complexities of academia and beyond. By learning active listening, curiosity, creativity, and problem-solving, students can create a sturdy foundation for lifelong learning. By building upon all these skills, you’ll be an expert critical thinker in no time—and you’ll be ready to conquer all that college has to offer! Frequently Asked QuestionsWhat questions should i ask to be a better critical thinker, how can i sharpen critical thinking skills for students, how do i avoid bias, can i use my critical thinking skills outside of school, will critical thinking skills help students in their future careers. Your ideal student home & a flight ticket awaits Follow us on :  Related Posts 30 Canadian Sayings & Slang Terms That You NEED to Know! The Top 10 Oldest Football Clubs in England to Know About! 20 Amazing Things To Do In NYC At Night! | Amber amber © 2024. All rights reserved. 4.8/5 on Trustpilot Rated as "Excellent" • 4800+ Reviews by students Rated as "Excellent" • 4800+ Reviews by Students  50 Super-Fun Critical Thinking Strategies to Use in Your Classroomby AuthorAmy Teaching students to be critical thinkers is perhaps the most important goal in education. All teachers, regardless of subject area, contribute to the process of teaching students to think for themselves. However, it’s not always an easy skill to teach. Students need guidance and practice with critical thinking strategies at every level. One problem with teaching critical thinking is that many different definitions of this skill exist. The Foundation for Critical Thinking offers four different definitions of the concept. Essentially, critical thinking is the ability to evaluate information and decide what we think about that information, a cumulative portfolio of skills our students need to be successful problem solvers in an ever-changing world. Here is a list of 50 classroom strategies for teachers to use to foster critical thinking among students of all ages. 1. Don’t give them the answersLearning is supposed to be hard, and while it may be tempting to jump in and direct students to the right answer, it’s better to let them work through a problem on their own. A good teacher is a guide, not an answer key. The goal is to help students work at their “challenge” level, as opposed to their “frustration” level. 2. Controversial issue barometerIn this activity, a line is drawn down the center of the classroom. The middle represents the neutral ground, and the ends of the line represent extremes of an issue. The teacher selects an issue and students space themselves along the line according to their opinions. Being able to articulate opinions and participate in civil discourse are important aspects of critical thinking. 3. Play devil’s advocateDuring a robust classroom discussion, an effective teacher challenges students by acting as devil’s advocate, no matter their personal opinion. “I don’t care WHAT you think, I just care THAT you think” is my classroom mantra. Critical thinking strategies that ask students to analyze both sides of an issue help create understanding and empathy. 4. Gallery walkIn a gallery walk, the teacher hangs images around the classroom related to the unit at hand (photographs, political cartoons, paintings). Students peruse the artwork much like they are in a museum, writing down their thoughts about each piece. 5. Review somethingA movie, TV show , a book, a restaurant, a pep assembly, today’s lesson – anything can be reviewed. Writing a review involves the complex skill of summary without spoilers and asks students to share their opinion and back it up with evidence. 6. Draw analogiesPick two unrelated things and ask students how those things are alike (for example, how is a museum like a snowstorm). The goal here is to encourage creativity and look for similarities. 7. Think of 25 uses for an everyday thingPick an everyday object (I use my camera tripod) and set a timer for five minutes. Challenge students to come up with 25 things they can use the object for within that time frame. The obvious answers will be exhausted quickly, so ridiculous answers such as “coatrack” and “stool” are encouraged. 8. Incorporate riddlesStudents love riddles. You could pose a question at the beginning of the week and allow students to ask questions about it all week. 9. Crosswords and sudoku puzzlesThe games section of the newspaper provides great brainteasers for students who finish their work early and need some extra brain stimulation. 10. Fine tune questioning techniquesA vibrant classroom discussion is made even better by a teacher who asks excellent, provocative questions. Questions should move beyond those with concrete answers to a place where students must examine why they think the way they do. 11. Socratic seminarThe Socratic seminar is perhaps the ultimate critical thinking activity. Students are given a universal question, such as “Do you believe it is acceptable to break the law if you believe the law is wrong?” They are given time to prepare and answer, and then, seated in a circle, students are directed to discuss the topic. Whereas the goal of a debate is to win, the goal of a Socratic discussion is for the group to reach greater understanding. 12. Inquiry based learningIn inquiry-based learning, students develop questions they want answers to, which drives the curriculum toward issues they care about. An engaged learner is an essential step in critical thinking. 13. Problem-based learningIn problem-based learning, students are given a problem and asked to develop research-based solutions. The problem can be a school problem (the lunchroom is overcrowded) or a global problem (sea levels are rising). 14. Challenge all assumptionsThe teacher must model this before students learn to apply this skill on their own. In this strategy, a teacher helps a student understand where his or her ingrained beliefs come from. Perhaps a student tells you they believe that stereotypes exist because they are true. An effective teacher can ask “Why do you think that?” and keep exploring the issue as students delve into the root of their beliefs. Question everything. 15. Emphasize data over beliefsData does not always support our beliefs, so our first priority must be to seek out data before drawing conclusions. 16. Teach confirmation biasConfirmation bias is the human tendency to seek out information that confirms what we already believe, rather than letting the data inform our conclusions. Understanding that this phenomenon exists can help students avoid it. 17. VisualizationHelp students make a plan before tackling a task. 18. Mind mappingMind mapping is a visual way to organize information. Students start with a central concept and create a web with subtopics that radiate outward. 19. Develop empathyEmpathy is often cited as an aspect of critical thinking. To do so, encourage students to think from a different point of view. They might write a “con” essay when they believe the “pro,” or write a letter from someone else’s perspective. 20. SummarizationSummarizing means taking all the information given and presenting it in a shortened fashion. 21. EncapsulationEncapsulation is a skill different from summarization. To encapsulate a topic, students must learn about it and then distill it down to its most relevant points, which means students are forming judgements about what is most and least important. 22. Weigh cause and effectThe process of examining cause and effect helps students develop critical thinking skills by thinking through the natural consequences of a given choice. 23. Problems in a jarPerfect for a bell-ringer, a teacher can stuff a mason jar with dilemmas that their students might face, such as, “Your best friend is refusing to talk to you today. What do you do?” Then, discuss possible answers. This works well for ethical dilemmas, too. 24. Transform one thing into anotherGive students an object, like a pencil or a mug. Define its everyday use (to write or to drink from). Then, tell the students to transform the object into something with an entirely separate use. Now what is it used for? 25. Which one doesn’t belong?Group items together and ask students to find the one that doesn’t belong. In first grade, this might be a grouping of vowels and a consonant; in high school, it might be heavy metals and a noble gas. 26. Compare/contrastCompare and contrast are important critical thinking strategies. Students can create a Venn diagram to show similarities or differences, or they could write a good old-fashioned compare/contrast essay about the characters of Romeo and Juliet . 27. Pick a word, find a related wordThis is another fun bell-ringer activity. The teacher starts with any word, and students go around the room and say another word related to that one. The obvious words go quickly, meaning the longer the game goes on, the more out-of-the-box the thinking gets. 28. Ranking of sourcesGive students a research topic and tell them to find three sources (books, YouTube videos, websites). Then ask them, what resource is best – and why. 29. HypothesizeThe very act of hypothesizing is critical thinking in action. Students are using what they know to find an answer to something they don’t know. 30. Guess what will happen nextThis works for scientific reactions, novels, current events, and more. Simply spell out what we know so far and ask students “and then what?” 31. Practice inferenceInference is the art of making an educated guess based on evidence presented and is an important component of critical thinking. 32. Connect text to selfAsk students to draw connections between what they are reading about to something happening in their world. For example, if their class is studying global warming, researching how global warming might impact their hometown will help make their studies relevant.  33. Levels of questioningThere are several levels of questions (as few as three and as many as six, depending on who you ask). These include factual questions, which have a right or wrong answer (most math problems are factual questions). There are also inferential questions, which ask students to make inferences based on both opinion and textual evidence. Additionally, there are universal questions, which are “big picture” questions where there are no right or wrong answers. Students should practice answering all levels of questions and writing their own questions, too. 34. Demand precise languageAn expansive vocabulary allows a student to express themselves more exactly, and precision is a major tool in the critical thinking toolkit. 35. Identify bias and hidden agendasHelping students to critically examine biases in sources will help them evaluate the trustworthiness of their sources. 36. Identify unanswered questionsAfter a unit of study is conducted, lead students through a discussion of what questions remain unanswered. In this way, students can work to develop a lifelong learner mentality. 37. Relate a topic in one subject area to other disciplinesHave students take something they are studying in your class and relate it to other disciplines. For example, if you are studying the Civil War in social studies, perhaps they could look up historical fiction novels set during the Civil War era or research medical advancements from the time period for science. 38. Have a question conversationStart with a general question and students must answer your question with a question of their own. Keep the conversation going. 39. Display a picture for 30 seconds, then take it downHave students list everything they can remember. This helps students train their memories and increases their ability to notice details. 40. Brainstorm, free-writeBrainstorming and freewriting are critical thinking strategies to get ideas on paper. In brainstorming, anything goes, no matter how off-the-wall. These are great tools to get ideas flowing that can then be used to inform research. 41. Step outside your comfort zoneDirect students to learn about a topic they have no interest in or find particularly challenging. In this case, their perseverance is being developed as they do something that is difficult for them. 42. The answer is, the question might beThis is another bell-ringer game that’s great for engaging those brains. You give students the answer and they come up with what the question might be. 43. Cooperative learningGroup work is a critical thinking staple because it teaches students that there is no one right way to approach a problem and that other opinions are equally valid. 44. What? So what? Now what?After concluding a unit of study, these three question frames can be used to help students contextualize their learning. 45. ReflectionAsk students to reflect on their work – specifically, how they can improve moving forward. 46. Classify and categorizeThese are higher level Bloom’s tasks for a reason. Categorizing requires students to think about like traits and rank them in order of importance. 47. Role playRoleplay allows students to practice creative thinking strategies. Here, students assume a role and act accordingly. 48. Set goalsHave students set concrete, measurable goals in your class so they understand why what they do matters. No matter your subject area, encourage students to read voraciously. Through reading they will be exposed to new ideas, new perspectives, and their worlds will grow. 50. Cultivate curiosityA curious mind is an engaged mind. Students should be encouraged to perform inquiry simply for the sake that it is a joy to learn about something we care about.  TREAT YO' INBOX!All the trending teacher stories, resources, videos, memes, podcasts, deals, and the laughter you need in your life! Distance LearningUsing technology to develop students’ critical thinking skills. by Jessica Mansbach What Is Critical Thinking?Critical thinking is a higher-order cognitive skill that is indispensable to students, readying them to respond to a variety of complex problems that are sure to arise in their personal and professional lives. The cognitive skills at the foundation of critical thinking are analysis, interpretation, evaluation, explanation, inference, and self-regulation. When students think critically, they actively engage in these processes:

To create environments that engage students in these processes, instructors need to ask questions, encourage the expression of diverse opinions, and involve students in a variety of hands-on activities that force them to be involved in their learning. Types of Critical Thinking SkillsInstructors should select activities based on the level of thinking they want students to do and the learning objectives for the course or assignment. The chart below describes questions to ask in order to show that students can demonstrate different levels of critical thinking.

*Adapted from Brown University’s Harriet W Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning Using Online Tools to Teach Critical Thinking SkillsOnline instructors can use technology tools to create activities that help students develop both lower-level and higher-level critical thinking skills.

Pulling it All TogetherCritical thinking is an invaluable skill that students need to be successful in their professional and personal lives. Instructors can be thoughtful and purposeful about creating learning objectives that promote lower and higher-level critical thinking skills, and about using technology to implement activities that support these learning objectives. Below are some additional resources about critical thinking. Additional ResourcesCarmichael, E., & Farrell, H. (2012). Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Online Resources in Developing Student Critical Thinking: Review of Literature and Case Study of a Critical Thinking Online Site. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice , 9 (1), 4. Lai, E. R. (2011). Critical thinking: A literature review. Pearson’s Research Reports , 6 , 40-41. Landers, H (n.d.). Using Peer Teaching In The Classroom. Retrieved electronically from https://tilt.colostate.edu/TipsAndGuides/Tip/180 Lynch, C. L., & Wolcott, S. K. (2001). Helping your students develop critical thinking skills (IDEA Paper# 37. In Manhattan, KS: The IDEA Center. Mandernach, B. J. (2006). Thinking critically about critical thinking: Integrating online tools to Promote Critical Thinking. Insight: A collection of faculty scholarship , 1 , 41-50. Yang, Y. T. C., & Wu, W. C. I. (2012). Digital storytelling for enhancing student academic achievement, critical thinking, and learning motivation: A year-long experimental study. Computers & Education , 59 (2), 339-352. Insight Assessment: Measuring Thinking Worldwide http://www.insightassessment.com/ Michigan State University’s Office of Faculty & Organizational Development, Critical Thinking: http://fod.msu.edu/oir/critical-thinking The Critical Thinking Community http://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/defining-critical-thinking/766 Related PostsThe Benefits of Using Digital Badges in an Online Course Student Video Assignments Zaption: October 2015 Online Learning Webinar Recording an Interview Over Blue Jeans 9 responses to “ Using Technology To Develop Students’ Critical Thinking Skills ”This is a great site for my students to learn how to develop critical thinking skills, especially in the STEM fields. Great tools to help all learners at all levels… not everyone learns at the same rate. Thanks for sharing the article. Is there any way to find tools which help in developing critical thinking skills to students? Technology needs to be advance to develop the below factors: Understand the links between ideas. Determine the importance and relevance of arguments and ideas. Recognize, build and appraise arguments. Excellent share! Can I know few tools which help in developing critical thinking skills to students? Any help will be appreciated. Thanks!

Brilliant post. Will be sharing this on our Twitter (@refthinking). I would love to chat to you about our tool, the Thinking Kit. It has been specifically designed to help students develop critical thinking skills whilst they also learn about the topics they ‘need’ to. Leave a Reply Cancel replyYour email address will not be published. Required fields are marked * Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment. Insert/edit linkEnter the destination URL Or link to existing content College Info Geek 7 Ways to Improve Your Critical Thinking SkillsC.I.G. is supported in part by its readers. If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. Read more here.  When I was in 7th grade, my U.S. history teacher gave my class the following advice: Your teachers in high school won’t expect you to remember every little fact about U.S. history. They can fill in the details you’ve forgotten. What they will expect, though, is for you to be able to think ; to know how to make connections between ideas and evaluate information critically. I didn’t realize it at the time, but my teacher was giving a concise summary of critical thinking. My high school teachers gave similar speeches when describing what would be expected of us in college: it’s not about the facts you know, but rather about your ability to evaluate them. And now that I’m in college, my professors often mention that the ability to think through and solve difficult problems matters more in the “real world” than specific content. Despite hearing so much about critical thinking all these years, I realized that I still couldn’t give a concrete definition of it, and I certainly couldn’t explain how to do it. It seemed like something that my teachers just expected us to pick up in the course of our studies. While I venture that a lot of us did learn it, I prefer to approach learning deliberately, and so I decided to investigate critical thinking for myself. What is it, how do we do it, why is it important, and how can we get better at it? This post is my attempt to answer those questions. In addition to answering these questions, I’ll also offer seven ways that you can start thinking more critically today, both in and outside of class. What Is Critical Thinking?“Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action.” – The Foundation for Critical Thinking The above definition from the Foundation for Critical Thinking website is pretty wordy, but critical thinking, in essence, is not that complex. Critical thinking is just deliberately and systematically processing information so that you can make better decisions and generally understand things better. The above definition includes so many words because critical thinking requires you to apply diverse intellectual tools to diverse information. Ways to critically think about information include:

That information can come from sources such as:

And all this is meant to guide: You can also define it this way: Critical thinking is the opposite of regular, everyday thinking. Moment to moment, most thinking happens automatically. When you think critically, you deliberately employ any of the above intellectual tools to reach more accurate conclusions than your brain automatically would (more on this in a bit). This is what critical thinking is. But so what? Why Does Critical Thinking Matter? Most of our everyday thinking is uncritical. If you think about it, this makes sense. If we had to think deliberately about every single action (such as breathing, for instance), we wouldn’t have any cognitive energy left for the important stuff like D&D. It’s good that much of our thinking is automatic. We can run into problems, though, when we let our automatic mental processes govern important decisions. Without critical thinking, it’s easy for people to manipulate us and for all sorts of catastrophes to result. Anywhere that some form of fundamentalism led to tragedy (the Holocaust is a textbook example), critical thinking was sorely lacking. Even day to day, it’s easy to get caught in pointless arguments or say stupid things just because you failed to stop and think deliberately. But you’re reading College Info Geek, so I’m sure you’re interested to know why critical thinking matters in college. Here’s why: According to Andrew Roberts, author of The Thinking Student’s Guide to College , c ritical thinking matters in college because students often adopt the wrong attitude to thinking about difficult questions. These attitudes include: Ignorant CertaintyIgnorant certainty is the belief that there are definite, correct answers to all questions–all you have to do is find the right source (102). It’s understandable that a lot of students come into college thinking this way–it’s enough to get you through most of your high school coursework. In college and in life, however, the answers to most meaningful questions are rarely straightforward. To get anywhere in college classes (especially upper-level ones), you have to think critically about the material. Naive RelativismNaive relativism is the belief that there is no truth and all arguments are equal (102-103). According to Roberts, this is often a view that students adopt once they learn the error of ignorant certainty. While it’s certainly a more “critical” approach than ignorant certainty, naive relativism is still inadequate since it misses the whole point of critical thinking: arriving at a more complete, “less wrong” answer. Part of thinking critically is evaluating the validity of arguments (yours and others’). Therefore, to think critically you must accept that some arguments are better (and that some are just plain awful). Critical thinking also matters in college because:

Doing college level work without critical is a lot like walking blindfolded: you’ll get somewhere , but it’s unlikely to be the place you desire.  The value of critical thinking doesn’t stop with college, however. Once you get out into the real world, critical thinking matters even more. This is because:

Take my free productivity masterclassWith a proper productivity system, nothing ever slips through the cracks. In just one hour, you'll learn how to set up your to-do list, calendar, note-taking system, file management, and more — the smart way. 7 Ways to Think More Critically Now we come to the part that I’m sure you’ve all been waiting for: how the heck do we get better at critical thinking? Below, you’ll find seven ways to get started. 1. Ask Basic Questions“The world is complicated. But does every problem require a complicated solution?” – Stephen J. Dubner Sometimes an explanation becomes so complex that the original question get lost. To avoid this, continually go back to the basic questions you asked when you set out to solve the problem. Here are a few key basic question you can ask when approaching any problem:

Some of the most breathtaking solutions to problems are astounding not because of their complexity, but because of their elegant simplicity. Seek the simple solution first. 2. Question Basic Assumptions“When you assume, you make an ass out of you and me.” The above saying holds true when you’re thinking through a problem. it’s quite easy to make an ass of yourself simply by failing to question your basic assumptions. Some of the greatest innovators in human history were those who simply looked up for a moment and wondered if one of everyone’s general assumptions was wrong. From Newton to Einstein to Yitang Zhang , questioning assumptions is where innovation happens. You don’t even have to be an aspiring Einstein to benefit from questioning your assumptions. That trip you’ve wanted to take? That hobby you’ve wanted to try? That internship you’ve wanted to get? That attractive person in your World Civilizations class you’ve wanted to talk to? All these things can be a reality if you just question your assumptions and critically evaluate your beliefs about what’s prudent, appropriate, or possible. If you’re looking for some help with this process, then check out Oblique Strategies . It’s a tool that musician Brian Eno and artist Peter Schmidt created to aid creative problem solving . Some of the “cards” are specific to music, but most work for any time you’re stuck on a problem. 3. Be Aware of Your Mental ProcessesHuman thought is amazing, but the speed and automation with which it happens can be a disadvantage when we’re trying to think critically. Our brains naturally use heuristics (mental shortcuts) to explain what’s happening around us. This was beneficial to humans when we were hunting large game and fighting off wild animals, but it can be disastrous when we’re trying to decide who to vote for. A critical thinker is aware of their cognitive biases and personal prejudices and how they influence seemingly “objective” decisions and solutions. All of us have biases in our thinking. Becoming aware of them is what makes critical thinking possible. 4. Try Reversing ThingsA great way to get “unstuck” on a hard problem is to try reversing things. It may seem obvious that X causes Y, but what if Y caused X? The “chicken and egg problem” a classic example of this. At first, it seems obvious that the chicken had to come first. The chicken lays the egg, after all. But then you quickly realize that the chicken had to come from somewhere, and since chickens come from eggs, the egg must have come first. Or did it? Even if it turns out that the reverse isn’t true, considering it can set you on the path to finding a solution. 5. Evaluate the Existing Evidence“If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” – Isaac Newton When you’re trying to solve a problem, it’s always helpful to look at other work that has been done in the same area. There’s no reason to start solving a problem from scratch when someone has already laid the groundwork. It’s important, however, to evaluate this information critically, or else you can easily reach the wrong conclusion. Ask the following questions of any evidence you encounter: