Search form

- Speaking exams

- Typical speaking tasks

Oral presentation

Giving an oral presentation as part of a speaking exam can be quite scary, but we're here to help you. Watch two students giving presentations and then read the tips carefully. Which tips do they follow? Which ones don’t they follow?

Instructions

Watch the video of two students doing an oral presentation as part of a speaking exam. Then read the tips below.

Melissa: Hi, everyone! Today I would like to talk about how to become the most popular teen in school.

Firstly, I think getting good academic results is the first factor to make you become popular since, having a good academic result, your teacher will award you in front of your schoolmates. Then, your schoolmates will know who you are and maybe they would like to get to know you because they want to learn something good from you.

Secondly, I think participating in school clubs and student unions can help to make you become popular, since after participating in these school clubs or student union, people will know who you are and it can help you to make friends all around the school, no matter senior forms or junior forms.

In conclusion, I think to become the most popular teen in school we need to have good academic results and also participate in school clubs and student union. Thank you!

Kelvin: Good evening, everyone! So, today I want to talk about whether the sale of cigarettes should be made illegal.

As we all know, cigarettes are not good for our health, not only oneself but also other people around. Moreover, many people die of lung cancer every year because of smoking cigarettes.

But, should the government make it illegal? I don’t think so, because Hong Kong is a place where people can enjoy lots of freedom and if the government banned the sale of cigarettes, many people would disagree with this and stand up to fight for their freedom.

Moreover, Hong Kong is a free market. If there's such a huge government intervention, I think it’s not good for Hong Kong’s economy.

So, if the government wants people to stop smoking cigarettes, what should it do? I think the government can use other administrative ways to do so, for example education and increasing the tax on cigarettes. Also, the government can ban the smokers smoking in public areas. So, this is the end of my presentation. Thank you.

It’s not easy to give a good oral presentation but these tips will help you. Here are our top tips for oral presentations.

- Use the planning time to prepare what you’re going to say.

- If you are allowed to have a note card, write short notes in point form.

- Use more formal language.

- Use short, simple sentences to express your ideas clearly.

- Pause from time to time and don’t speak too quickly. This allows the listener to understand your ideas. Include a short pause after each idea.

- Speak clearly and at the right volume.

- Have your notes ready in case you forget anything.

- Practise your presentation. If possible record yourself and listen to your presentation. If you can’t record yourself, ask a friend to listen to you. Does your friend understand you?

- Make your opinions very clear. Use expressions to give your opinion .

- Look at the people who are listening to you.

- Write out the whole presentation and learn every word by heart.

- Write out the whole presentation and read it aloud.

- Use very informal language.

- Only look at your note card. It’s important to look up at your listeners when you are speaking.

Useful language for presentations

Explain what your presentation is about at the beginning:

I’m going to talk about ... I’d like to talk about ... The main focus of this presentation is ...

Use these expressions to order your ideas:

First of all, ... Firstly, ... Then, ... Secondly, ... Next, ... Finally, ... Lastly, ... To sum up, ... In conclusion, ...

Use these expressions to add more ideas from the same point of view:

In addition, ... What’s more, ... Also, ... Added to this, ...

To introduce the opposite point of view you can use these words and expressions:

However, ... On the other hand, ... Then again, ...

Example presentation topics

- Violent computer games should be banned.

- The sale of cigarettes should be made illegal.

- Homework should be limited to just two nights a week.

- Should school students be required to wear a school uniform?

- How to become the most popular teen in school.

- Dogs should be banned from cities.

Check your language: ordering - parts of a presentation

Check your understanding: grouping - useful phrases, worksheets and downloads.

Do you think these tips will help you in your next speaking exam? Remember to tell us how well you do in future speaking exams!

Sign up to our newsletter for LearnEnglish Teens

We will process your data to send you our newsletter and updates based on your consent. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking the "unsubscribe" link at the bottom of every email. Read our privacy policy for more information.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

21 Tips and Strategies Supporting Learners’ Oral Presentations

Design & assign.

There are many options to consider when assigning an oral presentation. As you answer the following questions, reflect on your own commitment to continue using traditional oral presentations for evaluation.

Determine Oral Presentation Type

If you answered “No” to at least half of the questions, you may want to consider the following alternative formats that mitigate some of the specific anxieties your ELLs experience with oral presentations. While the default may be the traditional individual or group presentation of concepts in front of the whole class, there are a number of alternatives that may serve the same purpose.

Consider the different types of presentations and the steps that you can do to help your learners succeed.

Types of Oral Presentations

Short oral talks in a group

Usually a short oral talk in a group is informal with little time to prepare for this type of speech. Learners share their thoughts or opinions about a specific topic. This type of talk follows a structure with a brief introductory statement, 2-3 ideas and a concluding statement. These brief oral talks can help students develop confidence because they are presenting to a small group rather than the whole class. They do not have to create and coordinate visuals with their talk and the talk is short. There still needs to be substance to the talk, so participants should be given advance warning that they will be asked to speak on a particular topic. One advantage is that several students in the class can be presenting simultaneously; however, as a result, in-process marking is not possible.

Formal oral presentations in front of class

Formal oral presentations in front of the class usually require individual students to make a longer presentation, supported with effective visual aids. Adequate time has been given for the presenter to prepare the topic. This type of presentation can be used to present research, information in general, or to persuade. The presenter is often put in charge of the class during the presentation time, so in addition to presenting, the presenter has to keep the class engaged and in line. Formal oral presentations often involve a Q & A. Most of the grading can be done in-process because you are only observing one student at a time. It is very time consuming to get through a whole class of presentations and have the class engaged and learning and you are giving up control of many course hours and content coverage.

Group Presentations

- Tips for giving a group presentation

Sharing Presentations Online

Students can be made the presenter in online platforms to complete presentations. Zoom, Blackboard, WebEx and other similar software allow the moderator (Professor) to make specific participants hosts which enables them to share their screens and control the participation options of other students in the class. As each platform has variations on how to share documents and control the presentation, it is important that students are given specific instructions on how to “present” using the various platforms. If possible, set up separate “rooms” for students to practice in before their presentation.

- Instructions for screen sharing in Zoom

- Instructions for screen sharing in WebEx

- Instructions for screen sharing in Blackboard Collaborate

Use Oral Recordings of Presentations Synchronously or Asynchronously

Consider allowing students to record their presentations and present the recording to the class. While this would not be appropriate for a language class where the performance of the presentation is likely more important than the content, in other classes providing the opportunity for learners to record multiple times until they are satisfied with the output is an ideal way to optimize the quality of the presentation as well as reduce the performance related stress. The presentation can then be shared synchronously in class or online with the presenter hosting and fielding questions, or asynchronously posted on a discussion board or other app such as Flipgrid with the presenter responding to comments posted over a set period of time. A side benefit to the use of some of these tools such as Skye and Google Meet is that they are commonly used in the workforce so it good practice for post-graduation application of skills.

Possible Tools for Recording and Sharing

- Flipgrid – an easy to use app that lets students record short video clips and resubmit as many times as needed. The video stays in the Flipgrid app for other students to see (if shared) and allow for easy teacher responses whether via video or text. (Asynchronous)

- Skype – Follow the instructions to record and share a video on the MS website (Either if posted on course platform)

- Google Meet – Follow the i nstructions to record and share a presentation on Google Meet . (Either if posted on course platform)

- Zoom – students can share their narrated PPT slides via Zoom (don’t forget to enable the sound)

- Powerpoint – Recording of narrations for slides

- Youtube – Recorded videos can be uploaded to Youtube to share by following instructions to upload Youtube video

- OneDrive – most institutions provide OneDrive accounts for faculty and students as part of Office 365. Students can save their video in OneDrive and choose who to share it with (faculty member, group, class)

Presenting in Another Language

If the goal of the presentation is to demonstrate in depth understanding of the course content and ability to communicate that information effectively, does the presentation have to be done in English? Can the student’s mastery of the subject matter be demonstrated in another language with a translator? It would still be possible to evaluate the content of the presentation, the confidence, the performance, the visual aids etc. On the global stage, translated speeches and presentations are the norm by political leaders and content experts – why not let students show the depth of their understanding in a language they are comfortable with?

If a more formal type of oral presentation is required, is it possible to give students some choice to help reduce their anxiety? For example, could they choose to present to you alone, to a small group, or to the whole class?

Teach Making a Presentation Step by Step

Don’t assume that all the students in your class have been taught how to make a presentation for a college or university level class. Furthermore, there are many purposes for presentations (inform, educate, persuade, motivate, activate, entertain) which require different organizational structure, tone, content and visual aids.

- Ask the class to raise their hands if they feel ♦ very comfortable presenting in front of the class, ♦ somewhat comfortable presenting in front of the class or ♦ not comfortable presenting in front of the class. This will help you gauge your learners’ prior experience / comfort and also let learners in the class see that others, both native speakers and ELLs are nervous about presenting orally in class.

Provide Clear Instructions

- Write clear, detailed instructions (following the suggestions in Module 3).

- Ask students to download a copy to bring to class and encourage them to record annotations as you discuss expectations.

- Example: How many slides should you use as your visual aid? Do you need to use outside sources? What tools can you use to create this presentation?

- Include the rubric that you will use to grade the presentations and explain each section, noting sections that have higher weighting.

Provide a Guide to Planning

- Have students write a description of the target audience for their presentation and explicitly state the purpose of the presentation.

- Encourage students to read widely on their topic. The more content knowledge the learner has about the topic, the more confident the learner will be when presenting.

- Teach students how to do an effective presentation that meets your course expectations (if class time does not permit, offer an optional ‘office hours’ workshop). Remember – many of your students many never have presented a post-secondary presentation which may cause significant anxiety. Your ELL’s experiences with oral presentations may be limited or significantly different in terms of expectations based on their prior educational contexts.

- Have students view examples of good presentations and some bad ones – there are many examples available on YouTube such as Good Presentation vs Bad Presentation .

- Provide specific guidelines for each section of the presentation. How should learners introduce their presentation? How much detail is required? Is audience interaction required? Is a call to action expected at the end?

- If audience interaction is required, teach your students specific elicitation techniques (See Module 3)

- Designing Visual Aids Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo

- Presentation Aids Video

- Paralinguistic features like eye contact are potentially culture – bound. If the subject that you are teaching values eye contact, then include this expectation in the presentation. On the other hand, if your field of study doesn’t require presentations typically, consider valuing the cultural diversity of your learners and not grading learners negatively for not making eye contact.

- Review the rubric. Let learners know what you are specifically grading during the presentation. The rubric should be detailed enough that learners know what elements of the presentation are weighted the heaviest.

Model an Effective Presentation

A good speech is like a pencil; it has to have a point.

- Provide an exemplar of a presentation that you have presented yourself and recorded, or a presentation done by a previous student for which you have written permission to share.

Require Students to Practice

- Practice saying the presentation out loud

- Practice with a room mate/ classmate / family member / friend

- Go on a walk and talk – encourage students to get outside, and go for a walk – as they walk, they can say their presentation orally out loud. The fresh air and sunshine helps one to relax and reduce anxiety, so it is easier to focus on the talk.

- Record a practice presentation. Encourage students to find a quiet place to record and to use headphones with a mic to improve quality of the recording.

- If time allows, build formative practice presentations into the schedule. Have students practice their presentation in small groups and have other group mates give targeted feedback based on content, organization and presentation skills. Provide a checklist of expectations for the others in the group to use to provide specific, targeted feedback to the presenter. Students can watch their performance at home along with their peer’s feedback to identify areas for improvement.

- If you have assigned oral presentations in your class, review the course outcomes and the content covered in the assignment and determine if a formal oral presentation is necessary.

- Think of one alternative you could offer to students who struggle with individual assignments.

- Annotate your assignment with notes indicating possible modifications you could make to improve the inclusivity and equity of the assignment.

Tips for Online Students , Tips for Students

Presentation Tips For Students – Show And Tell Like A Pro!

Updated: July 15, 2022

Published: May 4, 2020

Giving a presentation to fellow classmates can be a bit daunting, especially if you are new to oral and visual presenting. But with the right PowerPoint tips, public speaking skills, and plenty of practice, you can present like a pro at your upcoming presentation. Here, we’ve laid out the best college presentation tips for students. And once you have one successful presentation, you’ll get better each time!

The Best Presentation Tips for Students

1. arrive early and be technically prepared.

Get to the room early and make sure you leave plenty of time for technical set up and technical difficulties. Have several backup drives (including an online version if possible) so that you are prepared for anything!

2. Know More

Be educated on more than just what you are sharing. That way, you can add points, speak candidly and confidently, and be prepared to answer any audience or teacher questions.

3. Share Your Passion With Your Audience

Connect with your audience by showing that you are passionate about your topic. Do this with the right tone, eye contact, and enthusiasm in your speech.

Photo by Austin Distel on Unsplash

4. pace yourself.

When student presenters are nervous, they tend to speed up their speech. This can be a problem, however, because your speed may be distracting, hard to understand, and you may run under your time.

5. Rehearse Thoroughly

Don’t just practice, rehearse your college presentation. Rehearse the entire delivery, including standing up, using gestures, and going through the slides.

6. Show Your Personality

You don’t need to be professional to the point of stiffness during your college presentation . Don’t be afraid to show your personality while presenting. It will make your presentation more interesting, and you will seem more approachable and confident.

7. Improvise

You can’t be 100% certain what will happen during your presentation. If things aren’t exactly as you expected, don’t be afraid to improvise and run off script.

8. Pump Yourself Up

Get yourself excited and full of energy before your college presentation! Your mood sets the tone for your presentation, and if you get excited right before, you will likely carry that throughout and you’ll make your audience excited about your topic as well.

9. Remember To Pause

Pausing not only only prevents filler words and helps you recollect your thoughts, it can also be a powerful indicator of importance within your presentation.

10. Create “Um” Alternatives

Try hard not to use filler words as they make you look unprofessional and uncertain. The best alternatives to “um” “like” and “so” are taking a breath or a silent pause to collect your thoughts.

11. Using Your Hands

Using your hands makes your college presentation more interesting and helps to get your points across. Point at the slide, use common hand gestures, or mimic a motion.

12. Eye Contact

Eye contact is one of the most important presentation tips for students . Many students are nervous, so they look at their notes or their feet. It is important that you show your confidence and engage your audience by making eye contact. The more presentations you give, the more eye contact will feel natural.

13. The Right Tone

The best public speakers vary their tone and pitch throughout their presentation. Try to change it up, and choose the right tone for your message.

Preparing an Effective College Presentation

1. open strong.

Grab your fellow students’ attention by starting strong with a powerful quote, intriguing scenario, or prompt for internal dialogue.

2. Start With A Mind Map

Mind mapping is literally creating a map of the contents of your college presentation. It is a visual representation and flow of your topics and can help you see the big picture, along with smaller details.

Photo by Teemu Paananen on Unsplash

3. edit yourself.

Some students make the mistake of including too much information in their college presentations. Instead of putting all of the information in there, choose the most important or relevant points, and elaborate on the spot if you feel it’s necessary.

4. Tell A Story

People love stories — they capture interest in ways that figures and facts cannot. Make your presentation relatable by including a story, or presenting in a story format.

5. The Power Of Humor

Using humor in your college presentation is one of the best presentation tips for students. Laughter will relax both you and the audience, and make your presentation more interesting

PowerPoint Tips for Students

1. use key phrases.

Choose a few key phrases that remain throughout your PowerPoint presentation. These should be phrases that really illustrate your point, and items that your audience will remember afterwards.

2. Limit Number Of Slides

Having too many slides will cause you to feel you need to rush through them to finish on time. Instead, include key points on a slide and take the time to talk about them. Try to think about including one slide per one minute of speech.

3. Plan Slide Layouts

Take some time to plan out how information will be displayed on your PowerPoint. Titles should be at the top, and bullets underneath. You may want to add title slides if you are changing to a new topic.

Photo by NeONBRAND on Unsplash

4. the right fonts.

Choose an easy-to-read font that isn’t stylized. Sans serif fonts tend to be easier to read when they are large. Try to stick to only two different fonts as well to keep the presentation clean.

5. Choosing Colors And Images

When it comes to colors, use contrasting ones: light on dark or dark on light. Try to choose a few main colors to use throughout the presentation. Choose quality images, and make sure to provide the source for the images.

6. Use Beautiful Visual Aids

Keep your presentation interesting and your audience awake by adding visual aids to your PowerPoint. Add captivating photos, data representations, or infographics to illustrate your information.

7. Don’t Read Straight From Your Notes

When you read straight from your notes, your tone tends to remain monotonous, you don’t leave much room for eye contact. Try looking up often, or memorizing portions of your presentation.

8. Avoid Too Much Text

PowerPoint was made for images and bullets, not for your entire speech to be written in paragraph form. Too much text can lose your adiences’ interest and understanding.

9. Try A Theme

Choosing the right theme is one of those presentation tips for students that is often overlooked. When you find the right theme, you keep your college presentation looking interesting, professional, and relevant.

10. Be Careful With Transitions And Animations

Animations and transitions can add a lot to your presentation, but don’t add to many or it will end up being distracting.

Public Speaking Tips for Students

1. choose your topic wisely.

If you are able to pick your topic, try to pick something that interests you and something that you want to learn about. Your interest will come through your speech.

2. Visit The Room Beforehand

If your presentation is being held somewhere outside of class, try to visit the location beforehand to prep your mind and calm your nerves.

3. Practice Makes Perfect

Practice, practice, practice! The only way you will feel fully confident is by practicing many times, both on your own and in front of others.

Photo by Product School on Unsplash

4. talk to someone about anxiety.

If you feel anxious about your college presentation, tell someone. It could be a friend, family member, your teacher, or a counselor. They will be able to help you with some strategies that will work best for you.

5. Remind Yourself Of Your Audience

Remember, you are presenting to your peers! They all likely have to make a presentation too at some point, and so have been or will be in the same boat. Remembering that your audience is on your side will help you stay cool and collected.

6. Observe Other Speakers

Look at famous leaders, or just other students who typically do well presenting. Notice what they are doing and how you can adapt your performance in those ways.

7. Remind Yourself Of Your Message

If you can come up with a central message, or goal, of your college presentation, you can remind yourself of it throughout your speech and let it guide you.

8. Don’t Apologize

If you make a mistake, don’t apologize. It is likely that no one even noticed! If you do feel you need to point out your own mistake, simply say it and keep moving on with your presentation. No need to be embarrassed, it happens even to the best presenters!

When you smile, you appear warm and inviting as a speaker. You will also relax yourself with your own smile.

The Bottom Line

It can be nerve racking presenting as a college student, but if you use our presentation tips for students, preparing and presenting your college presentation will be a breeze!

Related Articles

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

fa51e2b1dc8cca8f7467da564e77b5ea

- Make a Gift

- Join Our Email List

- Oral Presentations

With some thoughtful reflection and minor modification, student presentations can be as valuable online as they are in person. In deciding how to modify your assignment for remote teaching, it is key to reflect on what you hoped to assess about your students' learning through their presentations in the first place. Were you looking to evaluate how they make an argument in a new form, conduct research, work together in a group, and/or learn to use visuals? You may have had many objectives for your assignment. You still might be able to fulfill all of them; however, you may need to consider modifying or removing one of them if it would be difficult to include all of them in one assignment. (E.g. given that it is difficult for students in disparate locations to present together, it may be worth asking whether it is more important for students to demonstrate their ability to work together to prepare the presentation, or to make an argument on the spot. If you want to assess both, do you need to modify your assignment to have some individual components and some group components?)

Below we suggest three ways to incorporate student presentations into a remote class: (1) live via Zoom ; (2) pre-recorded via Zoom ; and (3) narrated slide decks . (It is also possible to have students submit pre-recorded presentations via Canvas’ media recording function, but we find this option to be less effective than the other three options presented here.)

Live Presentations in Zoom

- courses in which all students have reliable access to the internet and are comfortable with Zoom functions such as screenshare.

- attempting to reproduce the interactivity or spontaneity of live presentations in a classroom.

- assessing/providing feedback on students’ ability to present (and possibly field questions) "live."

Pre-recorded Presentations in Zoom

- presentations that do not rely heavily/exclusively on slides (although a student can use Zoom to record a presentation that includes a slide show).

Here's one way to have students give pre-recorded oral presentations (with or without accompanying visuals) using Zoom. If students are presenting using a slide deck, it may be easier to have them record their presentations directly into Powerpoint and submit those.

1. How to record a student presentation

Students can use Zoom ( harvard.zoom.us ) to create a permanent link that can function as a sort of "private video studio"; any time they go back to their Zoom account and click on the link, it will start a solo "meeting" that is recorded until they either stop the recording or leave the meeting. This is a great way for them to record themselves giving a presentation which they can share with others, in any of their courses. Your students will have all of the capabilities that any Zoom meeting host has—for example, they will be able to share a slideshow or other piece of media from their screen while they talk. Here’s how they can do it:

- Navigate to harvard.zoom.us and login. They should see the button to “Schedule a new meeting” right near the top of the screen. They should select that option.

- They can name the meeting anything they like—maybe something like “My personal recording studio”—and leave the description blank.

- Continuing onward, they should ignore the “When,” “Duration,” and “Timezone” prompts, and skip right to the checkbox for “Recurring meeting.” They should turn that on.

- In the “Recurrence” dropdown menu, they should select “No Fixed Time,” which will cause all of the date and time information to disappear—that’s good, and means they have succeeded in creating a link that they can re-use again and again.

- Skipping further down the page, they can ignore many of the other options, but they should make sure that “Video” is set to “on” for the host, and that “Audio” is set to “Both.” (These are probably their default options.)

- Finally, make sure that they check the last checkbox, “Record the meeting automatically,” and choose “In the cloud."

- After making their selections, they should click “Save.”

- Now, whenever they visit the “My meetings” page within harvard.zoom.us , they’ll see “My personal recording studio” at the top of the list and can use it to record themselves for any reason, including your presentation.

- While recording, they can speak to the camera, share a slideshow or other media while they talk, etc. Whenever they are sharing something on your screen, the resulting recording will capture what they are sharing fullscreen and overlay the student as a talking head in a small window in the upper righthand corner. Encourage your students to try a quick dry run and then watch the video (see the next step, below) to think through how they want to use (or not use) slides/images/sound in your presentation.

- Whenever they make a recording, the resulting video will automatically appear in their account within a few minutes to an hour after they finish, and they’ll be able to access it by clicking on “Recordings” in the left-side menu in harvard.zoom.us . They can watch it there to make sure they are happy with it; if not, they just need to go back into their “studio” again and re-record. They can delete recordings they don’t want to use (or just leave them there—there’s no penalty to having lots of recordings in an account). (They can also change the beginning and ending time of their presentations using the editing tool in Zoom, though we would recommend that instructors not overemphasize these kinds of polishing touches in assessing the clarity/sophistication/creativity/etc. of the presentation itself.)

- When it comes time for them to share their videos, they will be able to do so through a secure link. More on that next.

2. How to share a presentation with teaching staff

You and your teaching staff will need to let your students know how you would like to receive access to their recorded presentation—whether by email, uploading to Canvas, etc. Your students will be able to share their presentations through any of those methods by sharing a secure link. Students can retrieve that link by:

- Navigating to the “Recordings” page in the left side menu of harvard.zoom.us , and identifying the video they’d like to share with you.

- To the right of the video, they’ll see a “Share” button. They should click that.

- In the dialog box that pops up, students will need to make sure to turn on “Share this recording” and select “Only authenticated users can view.” They should leave the other options turned off.

- Students should look for the link for their recording toward the bottom of the gray box. Once they find it, they should highlight it with their mouse, and copy it.

- They can share that link by pasting it into an email, Canvas, etc.—however you’ve asked to receive it. That’s it!

3. How to share a presentation with peers / generate asynchronous discussion

As the instructor, you can choose to give students individual feedback on the recordings they share with you. But you can also choose to share them with your class and to create opportunities for peer feedback by using the same link through which students shared their videos with you. You might, for example, create a Canvas discussion forum for each student presenter, paste the link for the respective student’s video in the prompt (which will lead Canvas to embed the video right in the page), and encourage their classmates to watch their presentation and leave feedback or questions in the discussion forum.

Narrated Slide Decks

- Projects where students were already asked to create slide decks.

- Presentations where the slide deck matters more than seeing the student talk about the slide deck (this format can be helpful for students who have had difficult participating synchronously and/or using their camera).

It is relatively easy for students to record over a PowerPoint presentation. They can insert an audio file on each page by selecting the “Insert” tab and then the “Audio” icon. Students can also create narrated presentations that include slide transitions. Microsoft offers useful advice on how to record a presentation with slide transitions and narration. (N.B. Students could use Google Slides, but they would have to pre-record the audio, which they could do using their phone or Quicktime if they have a Mac.)

If your students are creating a presentation with transitions, here are some tips for recording:

- To pause recording, use the option from the menu bar

- To record narration on your last slide, you need to advance to the black screen that tells you the slide show has ended before ending the recording

- PowerPoint will not record while slides are transitioning so it can be helpful to build in a pause before transitioning to the next slide

- If you have transitions between the slides, you may need to change them so they do not truncate your audio recording

You can use similar strategies to those described in the section on pre-recording presentations in Zoom to share the recordings and create discussion.

- Designing Your Course

- In the Classroom

- Getting Feedback

- Equitable & Inclusive Teaching

- Advising and Mentoring

- Teaching and Your Career

- Where to Begin

- Communicating Expectations

- Sustaining Community

- Equity & Access

- Assessing Online Participation

- Key Moves for Online Interactivity

- Seminars & Sections

- Science Labs

- Language courses

- Designing Assignments for Remote Teaching

- Final Exams

- Office Hours / Helprooms

- Review Sessions

- TFs & Teaching Teams

- Back Again: The Return to In-Person Teaching

- Tools and Platforms

- The Science of Learning

- Bok Publications

- Other Resources Around Campus

- Skip to Nav

- Skip to Main

- Skip to Footer

How to Use Oral Presentations to Help English Language Learners Succeed

Please try again

Excerpted from “ The ELL Teacher’s Toolbox: Hundreds of Practical Ideas to Support Your Students ,” by Larry Ferlazzo and Katie Hull Sypnieski, with permission from the authors.

Having the confidence to speak in front of others is challenging for most people. For English Language Learners, this anxiety can be heightened because they are also speaking in a new language. We’ve found several benefits to incorporating opportunities for students to present to their peers in a positive and safe classroom environment. It helps them focus on pronunciation and clarity and also boosts their confidence. This type of practice is useful since students will surely have to make presentations in other classes, in college, and/or in their future jobs. However, what may be even more valuable is giving students the chance to take these risks in a collaborative, supportive environment.

Presentations also offer students the opportunity to become the teacher—something we welcome and they enjoy! They can further provide valuable listening practice for the rest of the class, especially when students are given a task to focus their listening.

Research confirms that in order for ELLs to acquire English they must engage in oral language practice and be given the opportunity to use language in meaningful ways for social and academic purposes (Williams & Roberts, 2011). Teaching students to design effective oral presentations has also been found to support thinking development as “the quality of presentation actually improves the quality of thought, and vice versa” (Živković, 2014, p. 474). Additionally, t he Common Core Speaking and Listening Standards specifically focus on oral presentations. These standards call for students to make effective and well-organized presentations and to use technology to enhance understanding of them.

GUIDELINES AND APPLICATION

Oral presentations can take many different forms in the ELL classroom—ranging from students briefly presenting their learning in small groups to creating a multi-slide presentation for the whole class. In this section, we give some general guidelines for oral presentations with ELLs. We then share ideas for helping students develop their presentation skills and describe specific ways we scaffold both short and long oral presentations.

We keep the following guidelines in mind when incorporating oral presentations into ELL instruction:

Length —We have students develop and deliver short presentations (usually 2-4 minutes) on a regular basis so they can practice their presentation skills with smaller, less overwhelming tasks. These presentations are often to another student or a small group. Once or twice a semester, students do a longer presentation (usually 5-8 minutes), many times with a partner or in a small group.

Novelty —Mixing up how students present (in small groups, in pairs, individually) and what they use to present (a poster, a paper placed under the document camera, props, a slide presentation, etc.) can increase engagement for students and the teacher!

Whole Class Processing -- We want to avoid students “tuning out” during oral presentations. Not only can it be frustrating for the speakers, but students also miss out on valuable listening practice. During oral presentations, and in any activity, we want to maximize the probability that all students are thinking and learning all the time. Jim Peterson and Ted Appel, administrators with whom we’ve worked closely, call this “whole class processing” (Ferlazzo, 2011, August 16) and it is also known as active participation. All students can be encouraged to actively participate in oral presentations by being given a listening task-- taking notes on a graphic organizer, providing written feedback to the speaker, using a checklist to evaluate presenters, etc.

Language Support —It is critical to provide ELLs, especially at the lower levels of English proficiency, with language support for oral presentations. In other words, thinking about what vocabulary, language features and organizational structures they may need, and then providing students with scaffolding, like speaking frames and graphic organizers. Oral presentations can also provide an opportunity for students to practice their summarizing skills. When students are presenting information on a topic they have researched, we remind them to summarize using their own words and to give credit when using someone else’s words.

Technology Support —It can’t be assumed that students have experience using technology tools in presentations. We find it most helpful using simple tools that are easy for students to learn (like Powerpoint without all the “bells and whistles” or Google Slides). We also emphasize to students that digital media should be used to help the audience understand what they are saying and not just to make a presentation flashy or pretty. We also share with our students what is known as “The Picture Superiority Effect”-- a body of research showing that people are better able to learn and recall information presented as pictures as opposed to just being presented with words (Kagan, 2013).

Groups -- Giving ELLs the opportunity to work and present in small groups is helpful in several ways. Presenting as a group (as opposed to by yourself) can help students feel less anxious. It also offers language-building opportunities as students communicate to develop and practice their presentations. Creating new knowledge as a group promotes collaboration and language acquisition--an ideal equation for a successful ELL classroom!

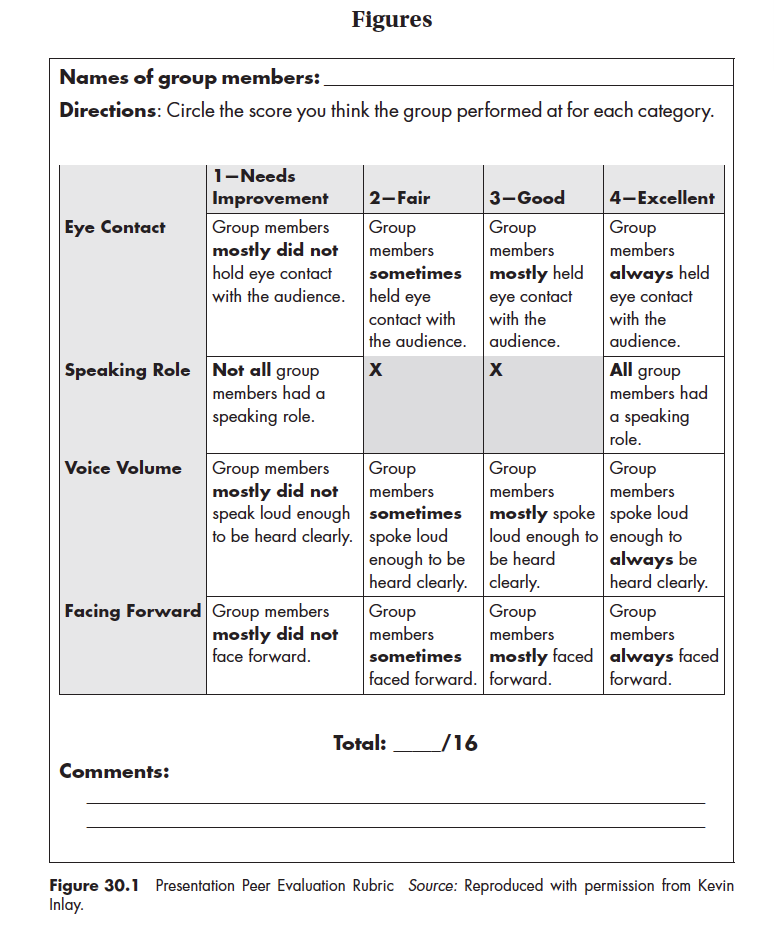

Teacher feedback/student evaluation --The focus of oral presentations with ELL students should be on the practice and skills they are gaining, not on the grade or “score” they are earning. Teachers can give out a simple rubric before students create their presentations. Then students can keep these expectations in mind as they develop and practice their presentations. The teacher, or classmates, can then use the rubric to offer feedback to the speaker. We also often ask students to reflect on their own presentation and complete the rubric as a form of self-assessment. Figure 30.1 – “Presentation Peer Evaluation Rubric” , developed by talented student teacher Kevin Inlay (who is now a teacher in his own classroom), is a simple rubric we used to improve group presentations in our ELL World History class.

Teaching Presentation Skills

We use the following two lesson ideas to explicitly teach how to develop effective presentation skills:

LESSON ONE: Speaking and Listening Do’s and Don’ts

We help our students understand and practice general presentation skills through an activity we call Speaking and Listening “Do’s and Don’ts.” We usually spread this lesson out among two class periods.

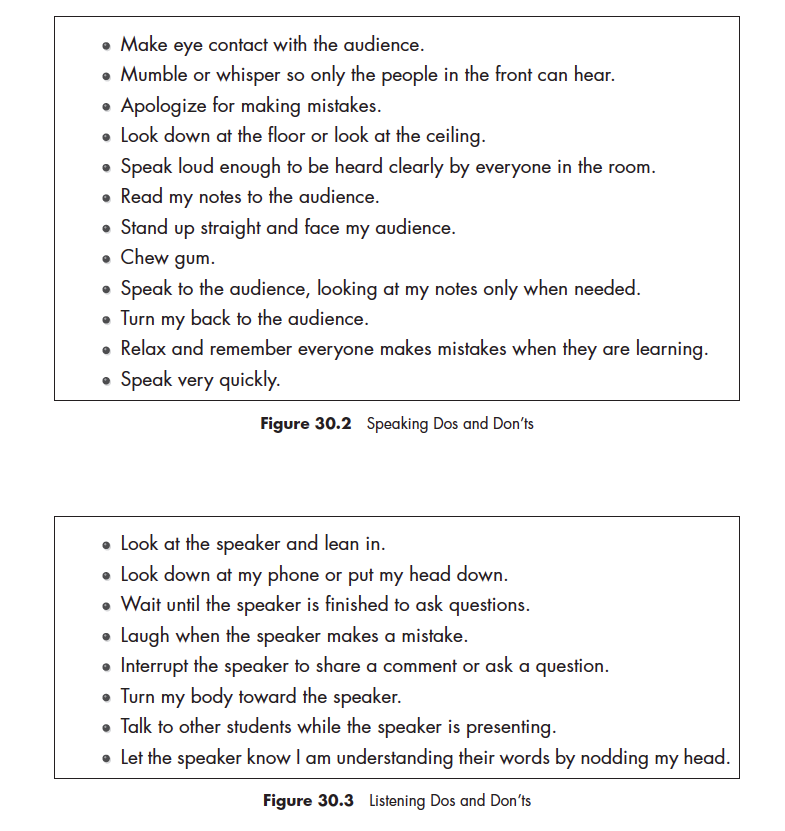

We first ask students to create a simple T-chart by folding a piece of paper in half and labeling one side “Do” and the other side “Don’t.” We then post Figure 30.2 “Speaking Do’s and Don’ts” on the document camera and display the first statement (the rest we cover with a blank sheet of paper).

We read the first statement, “Make eye contact with the audience,” and ask students if this is something they want to do when they are giving a presentation or if it is something they don’t want to do. Students write the statement where they think it belongs--under the “Do” column or “Don’t” Column. Students then share their answer with a partner and discuss why they put it in that column. After calling on a few pairs to share with the class, we move down the list repeating the same process of categorizing each statement as a “Do” or a “Don’t.” Students write it on their chart and discuss why it should be placed there.

After categorizing the statements for speaking, we give students Figure 30.3 “Listening Do’s and Don’ts .” We tell students to work in pairs to categorize the statements as something they do or something they don’t want to do when listening to a student presentation. This time, we ask students to make a quick poster with the headings “Do’s” and “Don’ts” for Listening. Under each heading students must list the corresponding statements--the teacher can circulate to check for accuracy. Students are asked to talk about why each statement belongs in each category and should be prepared to share their reasoning with the class. Students must also choose one “do” statement and one “don’t” statement to illustrate on their poster. Students can present their posters in small groups or with the whole class. This serves as a great opportunity to apply the speaking and listening “do’s” they just reviewed and heightens their awareness of the “don’ts!”

A fun twist, that also serves as a good review on a subsequent day, is to ask groups of students to pick two or three “do’s” and “don’ts” from both Speaking and Listening to act out in front of the class.

LESSON TWO Slide Presentations Concept Attainment

We periodically ask students to make slide presentations using PowerPoint or Google Slides to give them practice with developing visual aids (see the Home Culture activity later in this section). We show students how to make better slides, along with giving students the language support they may need in the form of an outline or sentence starters. An easy and effective way to do this is through Concept Attainment.

Concept Attainment involves the teacher identifying both "good" and "bad" examples of the intended learning objective. In this case, we use a PowerPoint containing three “good” slides and three “bad” ones (see them at The Best Resources For Teaching Students The Difference Between A Good and a Bad Slide ).

We start by showing students the first example of a “good” or “yes” slide (containing very little text and two images) and saying, “This is a yes.” However, we don’t explain why it is a “yes.” Then we show a “bad” or “no” example of a slide (containing multiple images randomly placed with a very “busy background”), saying, “This is a no” without explaining why. Students are then asked to think about them, and share with a partner why they think one is a "yes" and one is a "no."

At this point, we make a quick chart on a large sheet of paper (students can make individual charts on a piece of paper) and ask students to list the good and bad qualities they have observed so far. For example, under the “Good/Yes” column it might say “Has less words and the background is simple” and under the “Bad/No” column “Has too many pictures and the background is distracting.”

We then show the second “yes” example (containing one image with a short amount of text in a clear font) and the “no” example (containing way too much text and using a less clear font style). Students repeat the “think-pair-share” process and then the class again discusses what students are noticing about the “yes” and “no” examples. Then they add these observations to their chart.

Students repeat the whole process a final time with the third examples. The third “yes” example slide contains one image, minimal text and one bullet point. The third “no” example, on the other hand, contains multiple bullet points.

To reinforce this lesson at a later date, the teacher could show students more examples, or students could look for more “yes” and “no” examples online. They could continue to add more qualities of good and bad slides to their chart. See the Technology Connections section for links to good and bad PowerPoint examples, including the PowerPoint we use for this Concept Attainment lesson.

You can learn more about other presentations that support public speaking, such as home culture presentations, speed dating, talking points, top 5 and PechaKucha Book talks in our book, “ The ELL Teacher’s Toolbox: Hundreds of Practical Ideas to Support Your Students .”

Larry Ferlazzo has taught English Language Learners, mainstream and International Baccalaureate students at Luther Burbank High School in Sacramento for 15 years. He has authored eight books on education, hosts a popular blog for educators, and writes a weekly teacher advice column for Education Week Teacher . He was a community organizer for 19 years prior to becoming a high school teacher.

Katie Hull Sypnieski has worked with English Language Learners at the secondary level for over 20 years. She currently teaches middle school ELA and ELD at Rosa Parks K-8 School in Sacramento, California. She is a teaching consultant with the Area 3 Writing Project at the University of California, Davis and has leads professional development for teachers of ELLs. She is co-author (with Larry Ferlazzo) of The ESL/ELL Teacher’s Survival Guide and Navigating the Common Core with English Language Learners .

- Forms and Helpful Resources

- For New Grantseekers

- Federal Grant Information

- Managing Your Grant

- Fellowships

- IRB Policies, Procedures and Forms

- Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)

- Symposium on Undergraduate Research and Creative Expression (SOURCE)

- Sharing your Research

- Fall Interdisciplinary Research Symposium (FIReS)

- Summer Research Program and SIReS

- Oral Presentation Guidelines

An oral presentation provides a chance for students to present their research by reading a paper and/or showing PowerPoint slides to a group of interested faculty, students, and judges. These presentations will allow students to experience what it is like to present their research at a conference in their discipline.

Students making oral presentations will be organized into 90 minute sessions.

During each session, four students (or four groups of students working on the same project) from varying disciplines will present. Each student or group will have 15 minutes to present, followed by five minutes for questions and answers from the audience. A timer will sound at the 13-minute mark, letting you know when you have only two minutes left to wrap up.

At each session a faculty moderator will introduce the students and keep track of the allotted time. Several faculty judges will also be present at each session.

Guidelines for Oral Presentations:

- As with poster presentations, students are required to submit an abstract of their oral presentation via the Abstract Online Submission Form in ValpoScholar.

- If you have Google or PowerPoint slides, you will need to upload a copy of those slides to a Google Drive as instructed by the director of SOURCE at least 48 hours in advance . The director will then upload all slides onto the computer in the presentation room. You must also bring a flash drive copy of your slides as a backup on the day of the presentation.

- Practice your presentation in advance so that you know it will be within the 15-minute mark.

- A good rule of thumb is that it takes two minutes to read one page, so your paper should be no longer than seven to eight standard, double-spaced pages.

- Although you are not expected to memorize your presentation, you should be familiar enough with the material to make frequent eye contact with your audience.

- Handouts are not required, but if you choose to bring handouts to your presentation, you should bring 10 copies.

- Summarize your research succinctly: stating your thesis, argument, purpose, and research methods

- Present the evidence that supports your thesis

- Point out any conclusions you have reached

- Explain the larger significance of your research for your field

- Finally, students should consult with their faculty sponsor about the best way to present their material. Your faculty sponsor has probably made many such presentations and can give you some good tips.

- Institutional Review Board (IRB)

- Poster Presentation Guidelines

- Poster Presentation Resources

- SOURCE/Graduate Symposium 2022 (Final Program...

- be_ixf; php_sdk; php_sdk_1.4.26

- https://www.valpo.edu/sponsored-and-student-research/student-research/resources/oral-presentation-guidelines/

- Professional development

- Planning lessons and courses

Student presentations

In this article I would like to give you a few tips and some advice on what I've learned from helping students prepare and deliver presentations.

- Why I get students to do presentations

- Syllabus fit

- Planning a presentation lesson

- Classroom Management

Why I get students to do presentations Presentations are a great way to have students practise all language systems areas (vocabulary, grammar, discourse and phonology) and skills (speaking, reading, writing and listening). They also build confidence, and presenting is a skill that most people will need in the world of work. I find that students who are good presenters are better communicators all round, since they are able to structure and express their ideas clearly.

- Presentation skills are extremely useful both in and outside the classroom. After completing a project, a presentation is a channel for students to share with others what they have learned. It is also a chance to challenge and expand on their understanding of the topic by having others ask questions. And in the world of work, a confident presenter is able to inform and persuade colleagues effectively.

- Presentations can also form a natural part of task based learning. By focussing on a particular language point or skill, the presentation is a very practical way to revise and extend book, pair and group work. The audience can also be set a task, for example, a set of questions to answer on the presentation, which is a way of getting students to listen to each other.

Syllabus fit Normally the presentation will come towards the end of a lesson or series of lessons that focus on a particular language or skill area. It is a type of freer practice. This is because the students need to feel relatively confident about what they are doing before they stand up and do it in front of other people. If I have been teaching the past simple plus time phrases to tell a story, for example, I give my students plenty of controlled and semi controlled practice activities, such as gapfills, drills and information swaps before I ask them to present on, say, an important event in their country's history, which involves much freer use of the target grammar point.

Planning a presentation lesson Normally a presentation lesson will have an outline like this:

- Revision of key language areas

- Example presentation, which could be from a textbook or given by the teacher

- Students are given a transcript or outline of the presentation

- Students identify key stages of the example presentation – greeting, introduction, main points in order of importance, conclusion

- Focus on linking and signalling words ('Next…', 'Now I'd like you to look at…', etc.). Students underline these in the transcript/place them in the correct order

- Students are put into small groups and write down aims

- Students then write down key points which they order, as in the example

- Students decide who is going to say what and how

- Students prepare visuals (keep the time for this limited as too many visuals become distracting)

- Students practise at their tables

- Students deliver the presentations in front of the class, with the audience having an observation task to complete (see 'Assessment' below)

- The teacher takes notes for feedback later

It is important that the students plan and deliver the presentations in groups at first, unless they are extremely confident and/or fluent. This is because:

- Shy students cannot present alone

- Students can support each other before, during and after the presentation

- Getting ready for the presentation is a practice task in itself

- When you have a large class, it takes a very long time for everyone to present individually!

I find it's a good idea to spend time training students in setting clear aims. It is also important that as teachers we think clearly about why we are asking students to present.

Aims Presentations normally have one or more of the following aims:

- To inform/ raise awareness of an important issue

- To persuade people to do something

- Form part of an exam, demonstrating public speaking/presentation skills in a first or second language

I set students a task where they answer these questions:

- Why are you making the presentation?

- What do you want people to learn?

- How are you going to make it interesting?

Let's say I want to tell people about volcanoes. I want people to know about why volcanoes form and why they erupt. This would be an informative/awareness-raising presentation. So by the end, everyone should know something new about volcanoes, and they should be able to tell others about them. My plan might look like this:

- Introduction - what is a volcano? (2 minutes)

- Types of volcano (5 minutes)

- Volcanoes around the world (2 minutes)

- My favourite volcano (2 minutes)

- Conclusion (2-3 minutes)

- Questions (2 minutes)

Classroom Management I find that presentation lessons pass very quickly, due the large amount of preparation involved. With a class of 20 students, it will probably take at least 3 hours. With feedback and follow-up tasks, it can last even longer. I try to put students into groups of 3 or 4 with classes of up to 20 students, and larger groups of 5 or 6 with classes up to 40. If you have a class larger than 40, it would be a good idea to do the presentation in a hall or even outside.

Classroom management can become difficult during a presentations lesson, especially during the final presenting stage, as the presenters are partly responsible for managing the class! There are a few points I find effective here:

- Training students to stand near people who are chatting and talk 'through' the chatter, by demonstration

- Training students to stop talking if chatter continues, again by demonstration

- Asking for the audience's attention ('Can I have your attention please?')

- Setting the audience an observation task, which is also assessed by the teacher

- Limiting the amount of time spent preparing visuals

- Arranging furniture so everyone is facing the front

Most of these points are self-explanatory, but I will cover the observation task in more detail in the next section, which deals with assessment.

Assessment The teacher needs to carefully consider the assessment criteria, so that s/he can give meaningful feedback. I usually run through a checklist that covers:

- Level - I can't expect Elementary students to use a wide range of tenses or vocabulary, for example, but I'd expect Advanced students to have clear pronunciation and to use a wide range of vocabulary and grammar

- Age - Younger learners do not (normally) have the maturity or general knowledge of adults, and the teacher's expectations need to reflect this

- Needs - What kind of students are they? Business English students need to have much more sophisticated communication skills than others. Students who are preparing for an exam need to practise the skills that will be assessed in the exam.

I write a list of language related points I'm looking for. This covers:

- Range / accuracy of vocabulary

- Range / accuracy of grammar

- Presentation / discourse management- is it well structured? What linking words are used and how?

- Use of visuals- Do they help or hinder the presentation?

- Paralinguistic features

'Paralinguistics' refers to non-verbal communication. This is important in a presentation because eye contact, directing your voice to all parts of the room, using pitch and tone to keep attention and so on are all part of engaging an audience.

I find it's a good idea to let students in on the assessment process by setting them a peer observation task. The simplest way to do this is to write a checklist that relates to the aims of the lesson. A task for presentations on major historical events might have a checklist like this:

- Does the presenter greet the audience? YES/NO

- Does the presenter use the past tense? YES/NO

And so on. This normally helps me to keep all members of the audience awake. To be really sure, though, I include a question that involves personal response to the presentation such as 'What did you like about this presentation and why?'. If working with young learners, it's a good idea to tell them you will look at their answers to the observation task. Otherwise they might simply tick random answers!

Conclusion Presentations are a great way to practise a wide range of skills and to build the general confidence of your students. Due to problems with timing, I would recommend one lesson per term, building confidence bit by bit throughout the year. In a school curriculum this leaves time to get through the core syllabus and prepare for exams.

Presentations - Adult students

- Log in or register to post comments

Presentation Article

Research and insight

Browse fascinating case studies, research papers, publications and books by researchers and ELT experts from around the world.

See our publications, research and insight

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to prepare and...

How to prepare and deliver an effective oral presentation

- Related content

- Peer review

- Lucia Hartigan , registrar 1 ,

- Fionnuala Mone , fellow in maternal fetal medicine 1 ,

- Mary Higgins , consultant obstetrician 2

- 1 National Maternity Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

- 2 National Maternity Hospital, Dublin; Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Medicine and Medical Sciences, University College Dublin

- luciahartigan{at}hotmail.com

The success of an oral presentation lies in the speaker’s ability to transmit information to the audience. Lucia Hartigan and colleagues describe what they have learnt about delivering an effective scientific oral presentation from their own experiences, and their mistakes

The objective of an oral presentation is to portray large amounts of often complex information in a clear, bite sized fashion. Although some of the success lies in the content, the rest lies in the speaker’s skills in transmitting the information to the audience. 1

Preparation

It is important to be as well prepared as possible. Look at the venue in person, and find out the time allowed for your presentation and for questions, and the size of the audience and their backgrounds, which will allow the presentation to be pitched at the appropriate level.

See what the ambience and temperature are like and check that the format of your presentation is compatible with the available computer. This is particularly important when embedding videos. Before you begin, look at the video on stand-by and make sure the lights are dimmed and the speakers are functioning.

For visual aids, Microsoft PowerPoint or Apple Mac Keynote programmes are usual, although Prezi is increasing in popularity. Save the presentation on a USB stick, with email or cloud storage backup to avoid last minute disasters.

When preparing the presentation, start with an opening slide containing the title of the study, your name, and the date. Begin by addressing and thanking the audience and the organisation that has invited you to speak. Typically, the format includes background, study aims, methodology, results, strengths and weaknesses of the study, and conclusions.

If the study takes a lecturing format, consider including “any questions?” on a slide before you conclude, which will allow the audience to remember the take home messages. Ideally, the audience should remember three of the main points from the presentation. 2

Have a maximum of four short points per slide. If you can display something as a diagram, video, or a graph, use this instead of text and talk around it.

Animation is available in both Microsoft PowerPoint and the Apple Mac Keynote programme, and its use in presentations has been demonstrated to assist in the retention and recall of facts. 3 Do not overuse it, though, as it could make you appear unprofessional. If you show a video or diagram don’t just sit back—use a laser pointer to explain what is happening.

Rehearse your presentation in front of at least one person. Request feedback and amend accordingly. If possible, practise in the venue itself so things will not be unfamiliar on the day. If you appear comfortable, the audience will feel comfortable. Ask colleagues and seniors what questions they would ask and prepare responses to these questions.

It is important to dress appropriately, stand up straight, and project your voice towards the back of the room. Practise using a microphone, or any other presentation aids, in advance. If you don’t have your own presenting style, think of the style of inspirational scientific speakers you have seen and imitate it.

Try to present slides at the rate of around one slide a minute. If you talk too much, you will lose your audience’s attention. The slides or videos should be an adjunct to your presentation, so do not hide behind them, and be proud of the work you are presenting. You should avoid reading the wording on the slides, but instead talk around the content on them.

Maintain eye contact with the audience and remember to smile and pause after each comment, giving your nerves time to settle. Speak slowly and concisely, highlighting key points.

Do not assume that the audience is completely familiar with the topic you are passionate about, but don’t patronise them either. Use every presentation as an opportunity to teach, even your seniors. The information you are presenting may be new to them, but it is always important to know your audience’s background. You can then ensure you do not patronise world experts.

To maintain the audience’s attention, vary the tone and inflection of your voice. If appropriate, use humour, though you should run any comments or jokes past others beforehand and make sure they are culturally appropriate. Check every now and again that the audience is following and offer them the opportunity to ask questions.

Finishing up is the most important part, as this is when you send your take home message with the audience. Slow down, even though time is important at this stage. Conclude with the three key points from the study and leave the slide up for a further few seconds. Do not ramble on. Give the audience a chance to digest the presentation. Conclude by acknowledging those who assisted you in the study, and thank the audience and organisation. If you are presenting in North America, it is usual practice to conclude with an image of the team. If you wish to show references, insert a text box on the appropriate slide with the primary author, year, and paper, although this is not always required.

Answering questions can often feel like the most daunting part, but don’t look upon this as negative. Assume that the audience has listened and is interested in your research. Listen carefully, and if you are unsure about what someone is saying, ask for the question to be rephrased. Thank the audience member for asking the question and keep responses brief and concise. If you are unsure of the answer you can say that the questioner has raised an interesting point that you will have to investigate further. Have someone in the audience who will write down the questions for you, and remember that this is effectively free peer review.

Be proud of your achievements and try to do justice to the work that you and the rest of your group have done. You deserve to be up on that stage, so show off what you have achieved.

Competing interests: We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: None.

- ↵ Rovira A, Auger C, Naidich TP. How to prepare an oral presentation and a conference. Radiologica 2013 ; 55 (suppl 1): 2 -7S. OpenUrl

- ↵ Bourne PE. Ten simple rules for making good oral presentations. PLos Comput Biol 2007 ; 3 : e77 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Naqvi SH, Mobasher F, Afzal MA, Umair M, Kohli AN, Bukhari MH. Effectiveness of teaching methods in a medical institute: perceptions of medical students to teaching aids. J Pak Med Assoc 2013 ; 63 : 859 -64. OpenUrl

Academic Development Centre

Oral presentations

Using oral presentations to assess learning

Introduction.

Oral presentations are a form of assessment that calls on students to use the spoken word to express their knowledge and understanding of a topic. It allows capture of not only the research that the students have done but also a range of cognitive and transferable skills.

Different types of oral presentations

A common format is in-class presentations on a prepared topic, often supported by visual aids in the form of PowerPoint slides or a Prezi, with a standard length that varies between 10 and 20 minutes. In-class presentations can be performed individually or in a small group and are generally followed by a brief question and answer session.

Oral presentations are often combined with other modes of assessment; for example oral presentation of a project report, oral presentation of a poster, commentary on a practical exercise, etc.

Also common is the use of PechaKucha, a fast-paced presentation format consisting of a fixed number of slides that are set to move on every twenty seconds (Hirst, 2016). The original version was of 20 slides resulting in a 6 minute and 40 second presentation, however, you can reduce this to 10 or 15 to suit group size or topic complexity and coverage. One of the advantages of this format is that you can fit a large number of presentations in a short period of time and everyone has the same rules. It is also a format that enables students to express their creativity through the appropriate use of images on their slides to support their narrative.

When deciding which format of oral presentation best allows your students to demonstrate the learning outcomes, it is also useful to consider which format closely relates to real world practice in your subject area.

What can oral presentations assess?

The key questions to consider include:

- what will be assessed?

- who will be assessing?

This form of assessment places the emphasis on students’ capacity to arrange and present information in a clear, coherent and effective way’ rather than on their capacity to find relevant information and sources. However, as noted above, it could be used to assess both.

Oral presentations, depending on the task set, can be particularly useful in assessing:

- knowledge skills and critical analysis

- applied problem-solving abilities

- ability to research and prepare persuasive arguments

- ability to generate and synthesise ideas

- ability to communicate effectively

- ability to present information clearly and concisely

- ability to present information to an audience with appropriate use of visual and technical aids

- time management

- interpersonal and group skills.

When using this method you are likely to aim to assess a combination of the above to the extent specified by the learning outcomes. It is also important that all aspects being assessed are reflected in the marking criteria.

In the case of group presentation you might also assess:

- level of contribution to the group

- ability to contribute without dominating

- ability to maintain a clear role within the group.

See also the ‘ Assessing group work Link opens in a new window ’ section for further guidance.

As with all of the methods described in this resource it is important to ensure that the students are clear about what they expected to do and understand the criteria that will be used to asses them. (See Ginkel et al, 2017 for a useful case study.)

Although the use of oral presentations is increasingly common in higher education some students might not be familiar with this form of assessment. It is important therefore to provide opportunities to discuss expectations and practice in a safe environment, for example by building short presentation activities with discussion and feedback into class time.

Individual or group

It is not uncommon to assess group presentations. If you are opting for this format:

- will you assess outcome or process, or both?

- how will you distribute tasks and allocate marks?

- will group members contribute to the assessment by reporting group process?

Assessed oral presentations are often performed before a peer audience - either in-person or online. It is important to consider what role the peers will play and to ensure they are fully aware of expectations, ground rules and etiquette whether presentations take place online or on campus:

- will the presentation be peer assessed? If so how will you ensure everyone has a deep understanding of the criteria?

- will peers be required to interact during the presentation?

- will peers be required to ask questions after the presentation?

- what preparation will peers need to be able to perform their role?

- how will the presence and behaviour of peers impact on the assessment?

- how will you ensure equality of opportunities for students who are asked fewer/more/easier/harder questions by peers?

Hounsell and McCune (2001) note the importance of the physical setting and layout as one of the conditions which can impact on students’ performance; it is therefore advisable to offer students the opportunity to familiarise themselves with the space in which the presentations will take place and to agree layout of the space in advance.

Good practice

As a summary to the ideas above, Pickford and Brown (2006, p.65) list good practice, based on a number of case studies integrated in their text, which includes:

- make explicit the purpose and assessment criteria

- use the audience to contribute to the assessment process

- record [audio / video] presentations for self-assessment and reflection (you may have to do this for QA purposes anyway)

- keep presentations short

- consider bringing in externals from commerce / industry (to add authenticity)

- consider banning notes / audio visual aids (this may help if AI-generated/enhanced scripts run counter to intended learning outcomes)

- encourage students to engage in formative practice with peers (including formative practice of giving feedback)

- use a single presentation to assess synoptically; linking several parts / modules of the course

- give immediate oral feedback

- link back to the learning outcomes that the presentation is assessing; process or product.

Neumann in Havemann and Sherman (eds., 2017) provides a useful case study in chapter 19: Student Presentations at a Distance, and Grange & Enriquez in chapter 22: Moving from an Assessed Presentation during Class Time to a Video-based Assessment in a Spanish Culture Module.

Diversity & inclusion

Some students might feel more comfortable or be better able to express themselves orally than in writing, and vice versa . Others might have particular difficulties expressing themselves verbally, due for example to hearing or speech impediments, anxiety, personality, or language abilities. As with any other form of assessment it is important to be aware of elements that potentially put some students at a disadvantage and consider solutions that benefit all students.

Academic integrity

Oral presentations present relative low risk of academic misconduct if they are presented synchronously and in-class. Avoiding the use of a script can ensure that students are not simply reading out someone else’s text or an AI generated script, whilst the questions posed at the end can allow assessors to gauge the depth of understanding of the topic and structure presented. (Click here for further guidance on academic integrity .)

Recorded presentations (asynchronous) may be produced with help, and additional mechanisms to ensure that the work presented is their own work may be beneficial - such as a reflective account, or a live Q&A session. AI can create scripts, slides and presentations, copy real voices relatively convincingly, and create video avatars, these tools can enable students to create professional video content, and may make this sort of assessment more accessible. The desirability of such tools will depend upon what you are aiming to assess and how you will evaluate student performance.

Student and staff experience

Oral presentations provide a useful opportunity for students to practice skills which are required in the world of work. Through the process of preparing for an oral presentation, students can develop their ability to synthesise information and present to an audience. To improve authenticity the assessment might involve the use of an actual audience, realistic timeframes for preparation, collaboration between students and be situated in realistic contexts, which might include the use of AI tools.

As mentioned above it is important to remember that the stress of presenting information to a public audience might put some students at a disadvantage. Similarly non-native speakers might perceive language as an additional barrier. AI may reduce some of these challenges, but it will be important to ensure equal access to these tools to avoid disadvantaging students. Discussing criteria and expectations with your students, providing a clear structure, ensuring opportunities to practice and receive feedback will benefit all students.

Some disadvantages of oral presentations include:

- anxiety - students might feel anxious about this type of assessment and this might impact on their performance

- time - oral assessment can be time consuming both in terms of student preparation and performance