Case Formulation and Disorder-Specific Models

“[Formulation is] The lynch pin that holds theory and practice together” (Butler, 1998).

- all of a patient’s symptoms, disorders, and problems;

- hypotheses about the mechanisms causing the disorders and the problems;

- proposes the recent precipitants of the current problems and disorders;

- describes the origins of the mechanisms.

Resource type

Therapy tool.

Alternative Action Formulation

Belief Driven Formulation

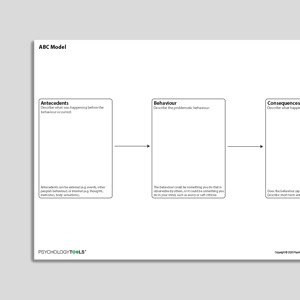

CBT Appraisal Model

Classical Conditioning

Information handouts

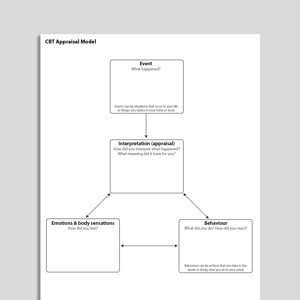

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Anorexia Nervosa (Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran, 2003)

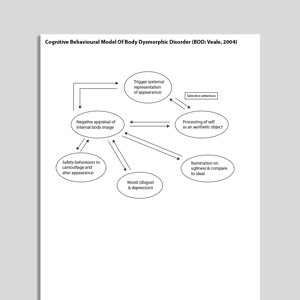

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD: Veale, 2004)

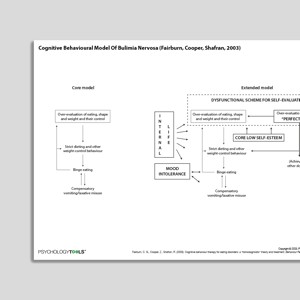

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Bulimia Nervosa (Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran, 2003)

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Clinical Perfectionism (Shafran, Cooper, Fairburn, 2002)

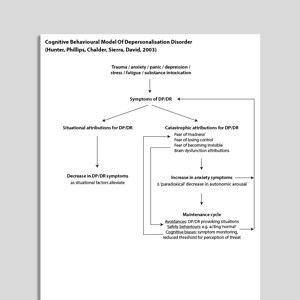

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Depersonalization (Hunter, Phillips, Chalder, Sierra, David, 2003)

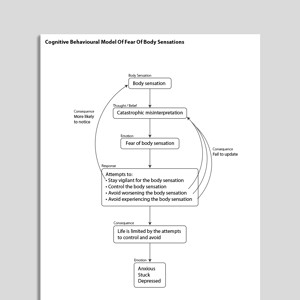

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Fear Of Body Sensations

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD: Dugas, Gagnon, Ladouceur, Freeston, 1998)

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Health Anxiety (Salkovskis, Warwick, Deale, 2003)

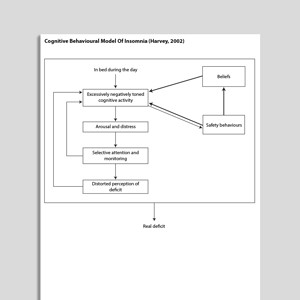

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Insomnia (Harvey, 2002)

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Intolerance Of Uncertainty And Generalized Anxiety Disorder Symptoms (Hebert, Dugas, 2019)

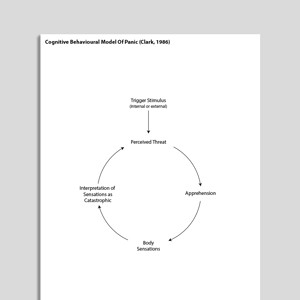

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Panic (Clark, 1986)

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD: Whalley, Cane, 2017)

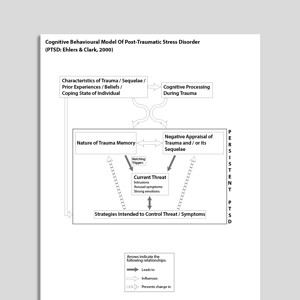

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD: Ehlers & Clark, 2000)

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Social Phobia (Clark, Wells, 1995)

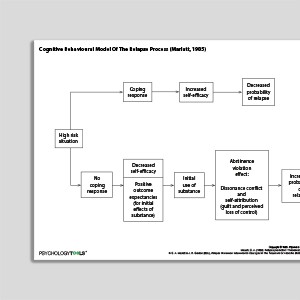

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of The Relapse Process (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985)

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Tinnitus (McKenna, Handscombe, Hoare, Hall, 2014)

Cognitive Case Formulation

Cross Sectional Formulation

Daily Monitoring Form

Developing Psychological Flexibility

Emotion Focused Formulation

Emotions Motivate Actions

Exploring Problems Using A Cross Sectional Model

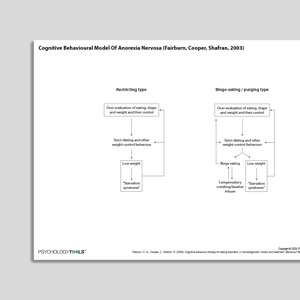

Exploring Problems Using An A-B-C Model

Friendly Formulation

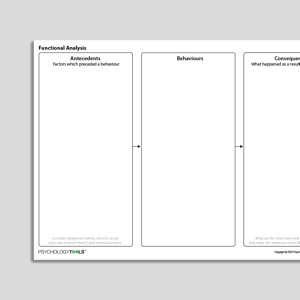

Functional Analysis

Functional Analysis With Intervention Planning

Health Anxiety Formulation

How Does Emotion Affect Your Life?

How Does This All Add Up To A Panic Attack? (Psychology Tools For Overcoming Panic)

Books & Chapters

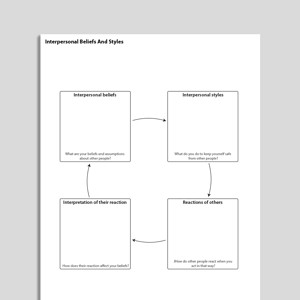

Interpersonal Beliefs And Styles

Longitudinal Formulation 1

Longitudinal Formulation 2

Low Self-Esteem Formulation

Making Sense Of Your Panic (Psychology Tools For Overcoming Panic)

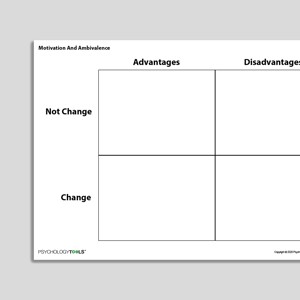

Motivation and Ambivalence

Motivational Systems (Emotional Regulation Systems)

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) Formulation

Operant Conditioning

Panic Formulation

Problem List

Process Focused Case Formulation

PTSD Formulation

Putting It All Together (Psychology Tools For Living Well)

Reciprocal CBT Formulation

Recognizing Agoraphobia

Recognizing Anorexia Nervosa

Recognizing Binge Eating Disorder

Recognizing Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Recognizing Bulimia Nervosa

Recognizing Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Recognizing Depersonalization-Derealization Disorder (DPD)

Recognizing Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

Recognizing Hoarding Disorder

Recognizing Hypochondriasis

Recognizing Insomnia Disorders

Recognizing Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

Recognizing Panic Disorder

Recognizing Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Recognizing Prolonged Grief Disorder

Recognizing Social Anxiety Disorder

Recognizing Specific Phobia

Schema Formulation

Social Anxiety Formulation

Stages Of Change

Stages Of Social Anxiety

SWOT Analysis

The Parts Of Your Panic (Psychology Tools For Overcoming Panic)

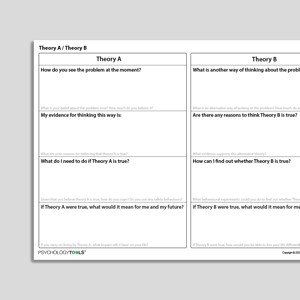

Theory A / Theory B

Theory A / Theory B (Archived)

Therapy Blueprint

Therapy Blueprint (Universal)

Therapy Blueprint For OCD

Therapy Blueprint For Panic

Therapy Blueprint For PTSD

Therapy Blueprint For Social Anxiety

Transdiagnostic Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Eating Disorders (Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran, 2003)

Transdiagnostic Processes

Treatment Planning Checklist

Understanding My Panic

Understanding PTSD

Vicious Flower Formulation

What Keeps Anorexia Going?

What Keeps Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) Going?

What Keeps Bulimia Going?

What Keeps Death Anxiety Going?

What Keeps Depersonalization And Derealization Going?

What Keeps Fears And Phobias Going?

What Keeps Low Self-Esteem Going?

What Keeps Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) Going?

What Keeps Panic Going?

What Keeps Perfectionism Going?

What Keeps Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Going?

What Keeps Social Anxiety Going?

Links to external resources.

Psychology Tools makes every effort to check external links and review their content. However, we are not responsible for the quality or content of external links and cannot guarantee that these links will work all of the time.

- Kuyken, W., Beshai, S., Dudley, R., Abel, A., Görg, N., Gower, P., … & Padesky, C. A. (2016). Assessing competence in collaborative case conceptualization: Development and preliminary psychometric properties of the Collaborative Case Conceptualization Rating Scale (CCC-RS).Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy,44(2), 179-192. Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Rating scale & coding manual Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Score sheet & feedback form Download Primary Link Archived Link

Case Conceptualization / Case Formulation

- Formulation in Compassion Focused Therapy | Paul Gilbert | 2007 Download Archived Link

- Maxi formulation | Helen Moya Download Primary Link Archived Link

- A case formulation approach to cognitive-behavior therapy | Jacqueline Persons | 2015 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- The “Blobby” formulation | Helen Kennerley | 2015 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Good practice guidelines on the use of psychological formulation | British Psychological Society: Division Of Clinical Psychology Download Archived Link

- A quick guide to ACT case conceptualization | Russ Harris | 2009 Download Archived Link

- Outline of ACT assessment / case formulation process | Jason Luoma Download Primary Link Archived Link

- ACT simple case formulation | Julian McNally Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Team formulation: key considerations in mental health services | Association of Clinical Psychologists UK | 2022 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- DBT Case Formulation Format | Comtois Download Archived Link

- The case formulation approach to cognitive behavior therapy | Jacqueline Persons | 2014 Download Primary Link Archived Link

Information Handouts

- Cycle vs. Heart Illustration for EFT | Paul Sigafus | 2013 Download Primary Link

Information (Professional)

- Working with Schemas, Core Beliefs, and Assumptions | Frank Wills | 2008 Download Primary Link Archived Link

Presentations

- The role of a case conceptualization model and core tasks of intervention | Donald Miechenbaum | 2014 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Cafe formulation in cognitive-behavioral therapy | Caleb Lack Download Primary Link Archived Link

- CBT case formulation | Jacqueline Persons Download Primary Link

- Case Formulation Template Download Archived Link

Recommended Reading

Cognitive behavioral models of disorders.

- Morrison, A. P. (2001). The interpretation of intrusions in psychosis: an integrative cognitive approach to hallucinations and delusions. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 29(3), 257-276.

- Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia.Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment,41(68), 00022-3.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- Dugas, M. J., Gagnon, F., Ladouceur, R., & Freeston, M. H. (1998). Generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary test of a conceptual model.Behaviour research and therapy,36(2), 215-226.

- Ehlers, A., & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(4), 319-345.

- Espie, C. A. (2002). Insomnia: conceptual issues in the development, persistence, and treatment of sleep disorder in adults. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 215–243.

- Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Shafran, R. (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment.Behaviour Research and Therapy,41(5), 509-528.

- Fennell, M. J. (1997). Low self-esteem: A cognitive perspective. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 25(1), 1-26.

- Fernie, B. A., Bharucha, Z., Nikčević, A. V., Marino, C., & Spada, M. M. (2017). A Metacognitive model of procrastination. Journal of Affective Disorders, 210, 196-203.

- Garety, P. A., Kuipers, E., Fowler, D., Freeman, D., & Bebbington, P. E. (2001). A cognitive model of the positive symptoms of psychosis. Psychological Medicine, 31(2), 189-195.

- Harvey, A. G. (2002). A cognitive model of insomnia. Behavior Research and Therapy, 40, 869–894.

- Heimberg, R. G., & Becker, R. E. (1981). Cognitive and behavioral models of assertive behavior: Review, analysis and integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 1(3), 353-373.

- Mansueto, C. S., Golomb, R. G., Thomas, A. M., & Stemberger, R. M. T. (1999). A comprehensive model for behavioral treatment of trichotillomania. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 6(1), 23-43.

- Marlatt, G. A. (1985). Relapse prevention: Theoretical rationale and overview of the model. In G. A. Marlatt & J. R. Gordon (Eds.), Relapse prevention (1st ed., pp. 280–250). New York: Guilford Press.

- Clark, D. M. (1986). A cognitive approach to panic. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 24(4), 461-470.

Social Anxiety Disorder

- Moscovitch, D. A. (2009). What is the core fear in social phobia? A new model to facilitate individualized case conceptualization and treatment. Cognitive and Behavioural Practice, 16. 123-134 Download Archived Link

- Salkovskis, P. M., Forrester, E., & Richards, C. (1998). Cognitive–behavioral approach to understanding obsessional thinking.The British Journal of Psychiatry,173(S35), 53-63.

- Salkovskis, P. M., Warwick, H. M. C., Deale, A. C. (2003). Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment for Severe and Persistent Health Anxiety (Hypochondriasis).Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 3, 353-367

- Vlaeyen, J. W. S., & Linton, S. J. (2000). Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain, 85(3), 317–332.

- Wells, A. (1995). Meta-cognition and worry: A cognitive model of generalized anxiety disorder.Behavioural and cognitive psychotherapy,23(3), 301-320 Download Archived Link

- Whalley, M. G., & Cane, D. A. (2017). A cognitive-behavioral model of persistent postural-perceptual dizziness. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 24(1), 72-89.

Team formulation

- Berry, K., Haddock, G., Kellett, S., Roberts, C., Drake, R., & Barrowclough, C. (2016). Feasibility of a ward‐based psychological intervention to improve staff and patient relationships in psychiatric rehabilitation settings. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55(3), 236-252. Download Primary Link Archived Link

- What is the case formulation approach to cognitive-behavior therapy? | Jacqueline Persons | 2008 Download Primary Link Archived Link

Case formulation / Case conceptualization

- Geisser, S., & Rizvi, S. L. (2014). The Case of” Sonia” Through the Lens of Dialectical Behavior Therapy.Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy,10(1), 30-39. Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Haynes, S. N., Leisen, M. B., Blaine, D. D. (1997). Design of individualized behavioral treatment programs using functional analytic clinical case models. Psychological Assessment, 9(4), 334-348 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Kuyken, W., Padesky, C. A., Dudley, R. (2008). The science and practice of case conceptualization. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36, 757-768 Download Archived Link

- Persons, J. B., & Lisa, S. T. (2015). Developing and Using a Case Formulation to Guide Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. Journal of Psychology & Psychotherapy, 5(2), 1 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Special issue: Team formulation. (2015). Clinical Psychology Forum, 275. Download Archived Link

- Spencer, H. M., Dudley, R., Johnston, L., Freeston, M. H., Turkington, D., & Tully, S. (2022). Case formulation—A vehicle for change? Exploring the impact of cognitive behavioural therapy formulation in first episode psychosis: A reflexive thematic analysis. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Boelen, P. A., van den Hout, M. A., & van den Bout, J. (2006). A Cognitive-Behavioral Conceptualization of Complicated Grief. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(2), 109–128.

- Borkovec, T. D., Alcaine, O., & Behar, E. (2004). Avoidance theory of worry and generalized anxiety disorder.Generalized anxiety disorder: Advances in research and practice,2004.

- Chapman, A. L., Gratz, K. L., & Brown, M. Z. (2006).Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: The experiential avoidance model.Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(3), 371–394.

What Is Case Conceptualization / Case Formulation?

Types of case formulation.

Case formulations can vary according to their purpose, and according to the information they attempt to convey. A number of types of formulation have been described:

- A cross-sectional formulation presents information relevant to a short time period, as though an event were sliced open at a particular moment in time to reveal the triggering event, thoughts (interpretations/appraisals), emotions, body feelings, and behaviors or reactions. One of the most popular formats for a cross-sectional formulation is Padesky and Mooney’s ‘hot cross bun’ (1990).

- A longitudinal formulation presents information relevant to the origin and maintenance of a problem. Weerasekera’s “Multiperspective model” popularized the use of the “5 Ps” approach (presenting, predisposing, precipitating, perpetuating, and protective) to case formulation (Weerasekera, 1993). Judith Beck’s cognitive conceptualization (1995) links longitudinal factors (including relevant childhood data, core beliefs, conditional assumptions, coping strategies) to cross-sectional breakdowns (situation, automatic thought and appraisal, emotion, behavior).

- Micro-formulations have been described as a helpful way of understanding the origin and effects of troubling imagery (Hackmann, Bennett-Levy, & Holmes, 2011). In this approach problematic images are explored along with their origin, associated appraisals, current impact, maintenance factors, and cognitive consequences.

- Disorder-specific models describe the critical presenting, predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors relevant to a condition. Disorder-specific cognitive behavioral conceptualizations have been published for most conditions including low self-esteem , panic , obsessive-compulsive disorder , psychosis , post-traumatic stress disorder .

- Beck, J. S. (1995). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond . New York: Guilford Press.

- Butler, G. (1998). Clinical formulation. In A. S. Bellack and M. Hersen (eds) Comprehensive clinical psychology . New York: Pergamon Press

- Hackmann, A., Bennett-Levy, J., & Holmes, E. A. (2011). Oxford guide to imagery in cognitive therapy . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Padesky, C. A., & Mooney, K. A. (1990). Presenting the cognitive model to clients. International Cognitive Therapy Newsletter , 6 , 13–14.

- Persons, J. B. (1989). Cognitive therapy in practice: A case formulation approach . New York: WW Norton.

- Persons, J. (2008). The case formulation approach to cognitive-behavior therapy (guides to individualized evidence-based treatment).

- Weerasekera, P. (1993). Formulation: A multiperspective model. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry , 38 (5), 351–358.

- For clinicians

- For students

- Resources at your fingertips

- Designed for effectiveness

- Resources by problem

- Translation Project

- Help center

- Try us for free

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

Case Formulation in Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: A Principle-Driven Approach

By Gillian A. Wilson, MA, and Martin M. Antony, PhD––Department of Psychology, Ryerson University

Cognitive-behavioral treatments are often described in step-by-step manuals. They provide strategies for treating a specific psychological disorder or diagnosis as opposed to addressing the specific problems and symptoms of a particular person.

Manualized treatments may fall short as they tend to adopt a general approach to treatment versus creating a specific approach tailored to each client.

While manualized treatments may be useful under certain circumstances—for example when individuals with a specific diagnosis have highly overlapping symptoms and problems—there are circumstances that call for a more flexible, individualized approach.

Here, we will focus on this specialized method known as a case formulation .

What is case formulation and when is it useful?

A case formulation is a hypothesis about the psychological mechanisms that cause and maintain an individual’s symptoms and problems (Kuyken et al., 2009; Persons, 2008).

It’s a principle-driven approach that targets mechanisms grounded in basic psychological theories—such as cognitive theory, classical and operant conditioning.

As outlined by Persons (2008), a case formulation can be useful when:

- A client has several disorders or problems.

- No treatment manual exists for a particular disorder or problem.

- A client has numerous treatment providers.

- Problems arise that are not addressed in a manual—nonadherence or therapeutic relationship ruptures.

Steps in Case Formulation

The case formulation should be developed in collaboration with the client to ensure engagement and increase commitment to treatment.

To develop a strong case formulation, the following steps are recommended (Persons, 2008):

- Conduct a thorough assessment to determine the presence of specific diagnoses, symptoms, and problems. It’s important to create a list of all of the client’s presenting symptoms and problems in various areas and life domains (i.e., panic attacks, excessive worry, low mood, poor academic performance, relationship difficulties).

- Factors that predisposed the client to develop the symptoms and problems

- Factors that precipitated the most recent episode

- Maintaining factors

- Protective factors

- Set up experiments to test out the initial case formulation. The results of these tests will confirm or disprove hypotheses about factors that cause or maintain the client’s symptoms and problems. For example, a therapist may use a thought record to test out whether a client’s procrastination stems from perfectionistic beliefs, which may reveal that procrastination or difficulty initiating tasks is instead due to thoughts of hopelessness. The case formulation should be revised based on the results.

- The case formulation should continue to be tested and revised throughout treatment with the goal of targeting mechanisms involved in the onset and maintenance of the client’s symptoms and problems. With ongoing consent of the client, it should be used as a guide for treatment planning and clinical decision making.

Components of Case Formulation

A case formulation should provide a coherent summary and explanation of a client’s symptoms and problems. It should include the following components (Persons, 2008):

- Problems: Psychological symptoms and features of a disorder, and related problems in various areas of life—social, interpersonal, academic, occupational.

- Mechanisms: Psychological factors—cognitive, behavioral—that cause or maintain the client’s problems. Mechanisms are the primary treatment targets.

- Origins: Distal factors or processes that lead to the mechanisms and thereby predispose the client to developing certain psychological symptoms and problems.

- Precipitants: Proximal factors that trigger or worsen the client’s symptoms and problems. Precipitants can be internal—physiological symptoms that trigger a panic attack—or external—a stressful life event that triggers a depressive episode.

The following is an example of a case formulation, based on recommendations by Persons (2008). It illustrates how a case formulation approach provides a parsimonious description of the cognitive and behavioral mechanisms underlying a client’s myriad of symptoms and problems.

When Rachel was in elementary school, her classmates laughed at her during her class presentations and teased her because of her stutter (ORIGINS). This led Rachel to develop the core schemas “I am socially awkward,” and “People are overly critical.” (COGNITIVE MECHANISMS). As an adult, she was preparing for a presentation at work (PRECIPITANT), and thought to herself, “I am going to humiliate myself in front of my colleagues.” (COGNITIVE MECHANISM). This lead to feelings of anxiety (PROBLEM). As a result, she called in sick the day of her presentation (BEHAVIORAL MECHANISM) and thought “I am a failure” (COGNITIVE MECHANISM) which lead to feelings of sadness and shame (PROBLEMS). She stayed in bed all day (PROBLEM) to avoid these feelings (BEHAVIORAL MECHANISM).

See also: Exposure Therapy for Anxiety-Related Disorders

A case formulation is an invaluable tool for highlighting how a client’s problems and symptoms are related. It aids the therapist in accurately identifying and targeting underlying psychological mechanisms with increased efficiency, leading to improved therapeutic outcomes

Join Us for a Training in Your Area!

Recommended Readings

Kuyken, W., Padesky, C. A., & Dudley, R. (2009). Collaborative case conceptualization: Working effectively with clients in cognitive-behavioral therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Persons, J. B. (2008). The case formulation approach to cognitive-behavior therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

In this article, I use a fictitious case study to help to describe and demonstrate how CBT Therapy can be used to reduce depression and anxiety.

CBT Therapy – A Simple Case Study

Carol is a fictional character used to explain the ways in which I may work. She presented with anxiety and feelings of depression, and hopelessness. I helped her challenge her thinking and fear.

My Response

I can hear your emotional distress and the presentation seems impossible for you at the moment. Let’s see if we can break things down and work on a little at a time, to hopefully make things feel more positive and manageable for you.

Using the ABC model of CBT.

This is based on the premise that an Activating event (A)

- In your case, it is your presentation at work.

Leads to emotional and behavioural Consequences (C)

- Which you could avoid the presentation/ phone in sick, and others will not see how well you know your stuff. This is discounting the positive.

The consequences are seen as arising from your individual belief (B)

- You described self-doubt. It makes you feel nervous and afraid, you think you might feel humiliated in front of others, and they might think you are an idiot.

From past experience, you have shared some unpleasant physical symptoms: your heart racing, feeling tongue-tied, sweating.

- These inferences could be seen as jumping to conclusions, every situation is different, and you are also describing emotional reasoning. If you do your presentation, symptoms will happen because it did last time.

You have evaluated that you cannot do it, others will judge you, and others can do better. You are magnifying the negatives, discounting the positives.

Fact – You have explained that you know your subject thoroughly and the management seem to have faith in you as they have asked you to do this. Let’s focus on this and aim to achieve your presentation.

To make this more manageable, we break things down into small tasks. We work on these smaller tasks in our sessions and as homework.

- Practice your presentation in front of others, trust the feedback, work on this and practice as necessary.

- While you concentrate on your knowledge, projection, confidence, delivery, body language and professionalism, record as necessary and we can discuss.

- Tap into the emotions and physical sensations you are feeling; we could look at grading them compared to the last time you spoke publicly and each time you practiced.

- We can practice relaxation strategies and positive thinking to help with physical symptoms and nervousness. You can continue to practice alone when in times of need.

- We will look at your common cognitive errors, look for evidence of them and disregard those that do not fit.

- We can check into your self-esteem and confidence levels and record results as we go along. Assessing progress and exploring and working on sticking points.

- I would like you to list all of the facts why you can complete your presentation, and we will explore the results.

I will support you through this Carol. I have faith in this process and in you, and evidence says you can do it. We can make a plan for the sessions/homework for the time we have before your presentation.

CBT Techniques and behavioural techniques used: The ABC Model

- Identifying faulty thoughts and feelings

- Identifying faulty thinking and looking at how it affects feelings and behaviour

- Challenging facts and focusing on positive

- Setting homework and goal and revisiting to look at progress

- Relaxation techniques

- Looking for evidence and Correcting distorted thinking

- Focusing on the client’s thoughts and feelings and underlying and irrational beliefs

- Looking at self-defeating beliefs and unrealistic beliefs

- Distinguishing between inferences and evaluations

- Teaching the client understanding and CBT method of change

- Triadic structure of CBT

- To help the client overcome blocks to change and independence

- To encourage positive thinking and change

- Looking at Schemata- underlying beliefs

- Applying distancing and decentring

- Using graded task performance

- Explaining and setting tasks/homework if the client agrees, and checking understanding.

- Explain and Test client commitment to tasks.

- Demonstrating how Carol might benefit from the sessions

- Reality testing

- Work on changing unhelpful work patterns

- Highlighting gaps between fears, experience and reality

- Review blocks and failure

- Empowering client to successfully take control

- Encouraging self-monitoring

So to summarise, for CBT therapy we work in manageable chunks. We identify the negatives and work on the fears you feel, finding strategies for you to cope and be calmer. We focus on you feeling confident and well equipped to deliver your presentation as we know you can.

About the Author:

I have many years of experience counselling individuals, young people and couples, supporting them through their struggles. I hope this article is of some help to you.

Please do get in touch through my “ Contact Me ” page to discuss your interest in CBT Therapy , or if you prefer, you are welcome to give me a call for a free introductory consultation.

Yours sincerely

BACP Accredited Counsellor Manchester

Writing a Counselling Case Study

As a counselling student, you may feel daunted when faced with writing your first counselling case study. Most training courses that qualify you as a counsellor or psychotherapist require you to complete case studies.

Before You Start Writing a Case Study

However good your case study, you won’t pass if you don’t meet the criteria set by your awarding body. So before you start writing, always check this, making sure that you have understood what is required.

For example, the ABC Level 4 Diploma in Therapeutic Counselling requires you to write two case studies as part of your external portfolio, to meet the following criteria:

- 4.2 Analyse the application of your own theoretical approach to your work with one client over a minimum of six sessions.

- 4.3 Evaluate the application of your own theoretical approach to your work with this client over a minimum of six sessions.

- 5.1 Analyse the learning gained from a minimum of two supervision sessions in relation to your work with one client.

- 5.2 Evaluate how this learning informed your work with this client over a minimum of two counselling sessions.

If you don’t meet these criteria exactly – for example, if you didn’t choose a client who you’d seen for enough sessions, if you described only one (rather than two) supervision sessions, or if you used the same client for both case studies – then you would get referred.

Check whether any more information is available on what your awarding body is looking for – e.g. ABC publishes regular ‘counselling exam summaries’ on its website; these provide valuable information on where recent students have gone wrong.

Selecting the Client

When you reflect on all the clients you have seen during training, you will no doubt realise that some clients are better suited to specific case studies than others. For example, you might have a client to whom you could easily apply your theoretical approach, and another where you gained real breakthroughs following your learning in supervision. These are good ones to choose.

Opening the Case Study

It’s usual to start your case study with a ‘pen portrait’ of the client – e.g. giving their age, gender and presenting issue. You might also like to describe how they seemed (in terms of both what they said and their body language) as they first entered the counselling room and during contracting.

If your agency uses assessment tools (e.g. CORE-10, WEMWBS, GAD-7, PHQ-9 etc.), you could say what your client scored at the start of therapy.

Free Handout Download

Writing a Case Study: 5 Tips

Describing the Client’s Counselling Journey

This is the part of the case study that varies greatly depending on what is required by the awarding body. Two common types of case study look at application of theory, and application of learning from supervision. Other possible types might examine ethics or self-awareness.

Theory-Based Case Studies

If you were doing the ABC Diploma mentioned above, then 4.1 would require you to break down the key concepts of the theoretical approach and examine each part in detail as it relates to practice. For example, in the case of congruence, you would need to explain why and how you used it with the client, and the result of this.

Meanwhile, 4.2 – the second part of this theory-based case study – would require you to assess the value and effectiveness of all the key concepts as you applied them to the same client, substantiating this with specific reasons. For example, you would continue with how effective and important congruence was in terms of the theoretical approach in practice, supporting this with reasoning.

In both, it would be important to structure the case study chronologically – that is, showing the flow of the counselling through at least six sessions rather than using the key concepts as headings.

Supervision-Based Case Studies

When writing supervision-based case studies (as required by ABC in their criteria 5.1 and 5.2, for example), it can be useful to use David Kolb’s learning cycle, which breaks down learning into four elements: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation.

Rory Lees-Oakes has written a detailed guide on writing supervision case studies – entitled How to Analyse Supervision Case Studies. This is available to members of the Counselling Study Resource (CSR).

Closing Your Case Study

In conclusion, you could explain how the course of sessions ended, giving the client’s closing score (if applicable). You could also reflect on your own learning, and how you might approach things differently in future.

Accreditation

- Wellbeing Registration

- Conferences

- What is CBT?

- Find a Therapist

Are you a member yet? Membership is open to all and is the first step towards accreditation.

- Case Study Marking Criteria

- Close Supervision Guidelines

- Cognitive Behavioural Psychotherapist Accreditation FAQs

- Core Professions

- Knowledge Skills and Attitudes

Guidance for assessing case studies

The BABCP Minimum Training standards require that at least four training cases must be presented and formally assessed as case studies. Case studies must meet our standards for formal assessment listed below.

The BABCP case study marking criteria (formerly known as Criteria for Evaluating Academic Case studies 2013) can be downloaded here .

Case studies are normally assessed as part of post-graduate CBT training. However, not all courses include all four we require. If this applies to you, or you do not have evidence of all the passed case studies, this document provides guidance on both how to write and assess case studies marked independently for accreditation.

Details of Training Cases

The criteria for BABCP CBT Practitioner Accreditation are set out in our Minimum Training Standards (MTS 2021) -

- at least four of the eight training cases must be presented and formally assessed as case studies, a further three must have received close supervision

- written case studies should be between 2000-4000 words (or 3-5000 if extended).

- the case studies can cover the same cases that are closely supervised or they can be different

- two of your formally assessed case studies may be delivered as a ‘live’ case report or presentation instead of a written study – if so, there should be supporting information such as slides or a written summary as part of the formal assessment

- case studies must be marked as a ‘pass’

- the marker must have experience of marking CBT case studies in an academic setting

- the completed mark sheet for the case study should be submitted along with an application for accreditation

A Suitable Assessor

The assessor should be accredited by BABCP or be a CBT therapist who is trained and qualified in CBT to postgraduate diploma level or equivalent (or would meet Minimum Training Standards ).

In addition, they should have experience of marking as a lecturer or tutor on an academic post-graduate CBT training course or equivalent. The assessor may, however, currently be independent of an academic institution.

If possible, we recommend that you contact assessors from your course, local courses or through other contacts. Otherwise, you can download a list of independent assessors here . It will be your responsibility to check that they still meet the criteria for a suitable assessor and to negotiate fees, timescale and, if appropriate, reasonable adjustments with them.

Assessors are asked to confirm that the case study has passed– this means that it is of an acceptable standard for a competent CBT therapist. Feedback should be given to the candidate and expectations of quality, content, layout, writing style and structure should be of a similar standard as case studies marked in a post-graduate programme.

Reasonable adjustments should be made where appropriate where the applicant can provide evidence of relevant additional needs.

The case study should demonstrate theoretical understanding and a research-based rationale for choosing a specific approach and knowledge of alternative options, which is consistent with evidence-based CBT practice. There should be a reflective element which identifies new learning.

All the areas described below should be covered where relevant.

Evidence of structured assessment, including the following areas -

- risk assessment

- current circumstances

- details of current presenting problem(s) and/or diagnosis, including co-morbidity and reason for seeking treatment at this point

- relevant personal history including development of the problem, previous treatment(s) and current coping

- use of appropriate standardised psychometric and idiographic measures

- suitability for CBT and socialisation to the model

- identified treatment goals

- assessment of diversity and relevant socio-cultural factors

Literature Review

- detailed description, explanation and critical evaluation of relevant CBT model(s) with rationale for choice of model

- knowledge of evidence base underpinning the theoretical model and chosen intervention(s)

- any adaptations to the model needed for the case

Case Formulation

The report should outline a coherent, concise formulation developed collaboratively over treatment with explicit input from client and include-

- evidence of individualised formulation at maintenance or cross-sectional level in keeping with diagnosis specific or generic CBT model, which is appropriate to the presentation and justified by the evidence base

- explanation of links between elements in maintenance cycle

- diagrams of maintenance cycles (and longitudinal formulation, if appropriate)

- identification of a trigger or critical incident/explanation of onset of problems (precipitating factors)

- underlying beliefs/assumptions (predisposing cognitive vulnerability factors) and explanation of links between these and maintenance cycles

- explanation of how past events may have contributed to/reinforced the beliefs

- awareness of any missing elements

Course of Therapy and Outcome

- Identification of theoretical aims of treatment according to the model used, and in relation to client’s presenting difficulties and goals for treatment

- treatment plan explicitly linked to formulation

- clear identification and description of the main phases of treatment and detail on at least two specific change processes, including the cognitive and/or behavioural interventions utilised and the rationale for their use

- examples of written materials used (may be in appendices)

- justification of any deviation from model or protocol used

- identification of client’s learning

- continued refinement of formulation (if necessary)

- evaluation of outcome including progress towards treatment goals

- changes in psychometric and idiographic measures, changes to client’s general functioning and client’s evaluation of therapy relapse prevention plan

- reflection on the progress of therapy and outcome of therapy, and the therapist’s learning. Including identification of therapist and client factors that helped or hindered therapy, use of supervision, the role of the therapeutic relationship and likelihood of treatment gains being maintained

- comment on the therapeutic alliance (interpersonal process) and if relevant how difficulties in treatment or the therapeutic relationship are understood in terms of the formulation, and how these were managed

- identification of what therapist may have done differently given another chance

- broader implications for the model or evidence base

- reflection on diversity and relevant socio-cultural factors

Structure, Presentation, References

The overall presentation should include -

- coherent structure with logical flow

- clarity of communication, grammar and spelling

- use of diagrams, tables and/or figures where appropriate

- quality of referencing in text and in reference list

- limited, judicious use of appendices

Additional guidance for verbally presented case studies

The criteria for written case reports above should be applied to marking verbally presented case studies, including the assessor criteria and the requirement for the report to pass. In addition -

- the presentation should include the opportunity for assessor(s) to give feedback and ask questions

- the presentation should be a minimum of 30 minutes’ duration (which may include the time for questions)

- there should be supporting information such as slides or a written summary

- any marking criteria that relate to the written aspect of the presentation should be used to assess the verbal aspect of a verbally presented report e.g. adhering to the word count would be equivalent to adhering to the allocated time

- as with written reports, the presentation should meet the standards expected of a healthcare profession with a post-graduate level qualification e.g. accurate and detailed slides, clarity of expression, logical sequence covering the areas outlined above, clarity and coherence of the content, respect for client confidentiality, effective use of tables and figures, lack of grammatical and spelling errors, appropriate links to evidence base and referencing

Marking and Feedback

A BABCP case study feedback sheet is available here . It is optional and assessors can use a different system of ensuring and demonstrating that the case studies have met all of the requirements.

A copy of the feedback sheet should be sent to the applicant for them to include with their accreditation application.

If the case study is not marked as a pass, please provide the applicant with constructive feedback.

We may request a copy of the report in order to moderate the marking.

Thought Records in CBT: 7 Examples and Templates

The good news is that by helping people view experiences differently and changing how they think, we can alter how they react. This shift in perception can offer clients the opportunity to gain control and handle situations more effectively.

But first, it is vital to capture negative and unhelpful thinking accurately. In this article, we explore how to do that using Thought Records and introduce examples, tips, and techniques that can help.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download these three Positive CBT Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will provide you with detailed insights into Positive CBT and give you the tools to apply it in your therapy or coaching.

This Article Contains:

What is a thought record and does it work, how are thought records used in cbt, real-life example, 3 tips for thought catching, thought records for anxiety and depression, 6 template worksheets.

- Aditional PositivePsychology.com Tools

A Take-Home Message

Unlike some forms of psychoanalysis, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy does not focus on the past. Instead, while acknowledging the importance of earlier experiences, CBT recognizes that our current thinking shapes how events are perceived (Wilding, 2015).

Perceptions are often more crucial than actual events.

CBT addresses our current irrational, illogical, and incorrect thinking. It offers a well-researched and widely validated tool for treating anxiety, stress, and many other mental health issues (Widnall, Price, Trompetter, & Dunn, 2019).

The strength of CBT comes from it being both short term and solution focused. People also get the commonsense approach of CBT. This is essential as, according to the American Psychological Association (2017), CBT “emphasizes helping individuals learn to be their own therapists.”

While CBT can be understood by the untrained, complex and persistent problems typically require a professional’s support to make negative automatic thoughts visible and learn better ways of coping.

How do we recognize negative thinking?

Negative (and illogical and incorrect) thinking is likely to stop us from reaching short-term and life goals.

CBT does not suggest we try to block such thoughts, but rather identify them before considering their accuracy and effectiveness. Unhelpful ones can be reevaluated and replaced with thoughts that are rational and open minded.

Negative thoughts can take many forms yet often arise from specific types of thinking, for example (Wilding, 2015):

- You believe you know what others are thinking

- You expect disaster

- You tend to personalize general comments

- You generalize specific incidents

- You blame others for your thoughts and actions

As opposed to positive or even neutral thinking, such thought patterns lead us to interpret events negatively; in the long term, they can lead to depression and anxiety.

Such cognitive distortions are often automatic; they pop into our heads, unannounced and unwanted, and linger. They profoundly affect how we feel, with thoughts such as “I can’t cope” or “I feel awful,” and how we behave by avoiding opportunities and situations.

How do we capture negative thinking?

It can be useful to check in and ask ourselves if our thoughts are positive and constructive or negative and damaging throughout the day.

A simple example is given below (modified from Wilding, 2015):

Does it work?

Once identified, Thought Records (TRs) provide a practical way to capture unhelpful thinking for functional analysis and review (Beck, 2011).

Indeed, TRs are potent tools for evaluating automatic thoughts at times of distress and remain a popular choice for therapists.

Research has confirmed that TRs are highly successful at effecting belief change and are recommended for CBT practitioners working with a client (McManus, Van Doorn, & Yiend, 2012).

Completing a thought record

The more often clients practice completing TRs, the greater their awareness of negative or dysfunctional thinking.

A good time to complete a TR is shortly after noticing a change in how we feel.

Begin by asking the client to consider the following questions regarding the thinking behind a recent emotional upset, difficult situation, or concern (modified from Beck, 2011):

- Is there any evidence to support this idea?

- What is the evidence for and against it?

- Are there other explanations or viewpoints?

- What is the worst that could happen, and how would I cope?

- What is the best that could happen?

- What outcome is most realistic?

- What is the result of such automatic thinking?

The following questions encourage us to start considering how we can challenge our thinking:

- What would happen if I changed my thinking?

- What would I tell a close friend if they were in this situation?

- What should I do next?

While automatic thoughts may have some supporting evidence, that evidence is typically inadequate and inaccurate and ignores evidence to the contrary.

When ready, ask your client to complete a Thought Record Worksheet , describing:

- A situation that led to unpleasant feelings (e.g., being turned down for a job)

- The negative thoughts that arose (I’m useless)

- The emotions running through your mind (I’m ashamed)

- Your response (blame interviewer, stop applying for jobs)

- A better, more adaptive response (ask for feedback from the interviewer)

Thought challenging

Our thinking style is influenced by inherited personality traits, upbringing, and meaningful events and interprets what we experience. Two people can have precisely the same encounter yet respond very differently.

CBT is a practical way to identify and challenge unhelpful thought patterns.

Thought challenging begins with focusing on the most powerful, negative thoughts captured in the TR Worksheet.

Ask your client to complete the first few columns in the Thought Record Worksheet, describing the situation in question. Here again is an example (modified from Wilding, 2015).

Is there anything you could do differently in the future? For example, rather than jumping to conclusions, challenge your thinking with questions.

With practice, such a change in thinking can become second nature. And the act of challenging thoughts will increasingly become internalized, with no need to write them down.

You don’t need to remove all negative thinking; instead, you are trying to find a more balanced outlook.

Download 3 Free Positive CBT Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to find new pathways to reduce suffering and more effectively cope with life stressors.

Download 3 Free Positive CBT Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Sally is with her therapist and has already been asked to consider a set of questions similar to those above to evaluate her thought “Bob won’t want to go out with me” (modified from Beck, 2011).

Taking one column at a time, she completes a TR, including percentage scores to indicate likelihood or intensity:

Sally was then asked to consider what cognitive distortion category her thinking might fall into (in this case, it’s fortune telling or mind reading ). She assumed that she knew what Bob was thinking, but she didn’t.

Next, Sally was asked to consider the following set of questions, write down her thoughts, and rate the likelihood (%) of each one:

- What is the evidence that the automatic thought is true?

- Is there a different explanation?

- What’s the worst (and best) that could happen?

- What’s the most likely outcome?

- What’s the effect of believing this automatic thought?

- How could changing my thinking help?

- What should I do about it?

- What would you say to a friend?

Adaptive responses

- I don’t really know if he wants to go or not (90%).

- He is friendly to me in class (90%).

- The worst that will happen is that he will say no, and I’ll feel bad for a while, but I could talk to my friend Alison about it (90%).

- The best is that he will say yes (100%).

- The most realistic outcome is that he will say he’s busy but still be friendly to me (80%).

- If I keep assuming he doesn’t want to go with me, I won’t ask him at all (100%).

- I should just go up and ask him (50%).

- What’s the big deal anyway (75%)?

Lastly, Sally was asked to rate how much she now believes the automatic thought, how intense her sadness is, and what she would do next.

- Automatic thought – 50%

- Sad (emotion) – 50%

- I’ll ask him

Completing a TR will not remove all negative emotions, but even reducing their impact by a small amount makes the effort worthwhile.

1. Complete the TR in stages

Most clients find that TRs are incredibly useful for organizing their thoughts and considering their responses.

However, if less daunting or confusing, ask the client to complete the first four columns (date and time, situation, automatic thoughts, and emotions) in one session, and then the last two columns (adaptive response, outcome) in the next session (Beck, 2011).

2. TR alternative

TRs aren’t the only way to capture thoughts. The following questions can be used to replace the worksheet and more easily guide the client as they challenge a thought (modified from Beck, 2011):

- What is the situation? My friend didn’t call .

- What am I thinking? She doesn’t like me anymore.

- Why do I think this is true? She said she would call .

- Why might this not be true? She has forgotten to call in the past, and her mother is not well .

- What’s another way to look at this? Something important came up .

- What’s the worst outcome? She stops being my friend, and I focus on my other friends .

- What’s the best outcome? She will call and say she is sorry, but something came up .

- What will probably happen? She will call and tell me she lost her phone .

- What will happen if I keep reacting in this way? I will keep getting upset and push friends away .

- What could happen if I changed my thinking? I could feel better and check if she is okay .

- What would I tell a friend if this happened to them? Give the person extra time to call, or call to see if everything is okay .

3. Positive and negative event TRs

We don’t have to limit our focus to negative TRs; it can be useful to explore positive ones too (Wilding, 2015):

Choose a recent event and complete a TR that also includes:

- Positive thoughts – I’m excited about my new job .

- Neutral thoughts – What am I going to have for dinner ?

- Evaluative thoughts – I wonder where I will sit in my new job ?

- Rational thoughts – If it’s not the right job, I can always take another .

- Action-oriented thoughts – I’m determined to be good in my new job; if I need to do some extra hours to catch up, then that’s okay .

It’s useful to understand multiple categories of thoughts. It is then easier to spot the negative ones; for example, I will be useless in the job, and they only gave it to me because no one else showed up .

Negative thoughts are the ones that will leave you feeling upset, unhappy, and anxious.

3 Steps of thought journaling using CBT – The Lukin Center

Reviewing our TRs is a vital exercise for recognizing repeating negative (or unhelpful) behavioral patterns.

We may spot the signs of anxiety – difficulty focusing and sleeping, feeling on edge – as we review our thoughts and responses.

Perhaps rather than addressing an issue, we reduce the unwanted symptoms through avoidance. We may decline invitations to social events or refuse to apply for more senior positions at work.

While such coping mechanisms may stop us from feeling bad, they do not solve underlying problems (Wilding, 2015).

As we assess our thoughts, it can be worth asking if this will make me feel better or get better. If it is the former, it can be worth seeking other ways of addressing feelings of anxiety, such as relaxation or working on our coping techniques.

Depression can leave us exhausted. Constant tiredness and staying in bed can all be signals to watch out for when reviewing TRs.

We may misguidedly think that additional rest will mean we are more ready for the world from which we are hiding. So, we avoid the effort of doing things. We call in sick, tell friends we can’t make social events, and miss the office party.

And yet, this behavior reinforces our negative feelings. If we don’t show up, we start to believe that no one notices or cares that we are absent. We are strengthening the negative.

Wilding (2015) describes this as the all-too-much error and suggests that the answer can come from adopting a do-the-opposite approach.

By first being aware of these negative thoughts while reviewing TRs, behavior can be turned on its head. Going into work and accepting the invitation can build mastery over emotions and an all-important sense of control.

Thought Record Worksheet

This Automatic Thought Record Worksheet provides an excellent way to capture faulty thinking and begin the process of cognitive restructuring .

‘Mood first’ thought record

The following variation on the TR theme provides a simple way to record feelings , situations , and automatic thoughts in one place.

If there are multiple, automatic thoughts for the same situation, circle the strongest one (for example, I can’t take on new responsibilities ). Focus on the thoughts and feelings that upset you the most and give them a score (fearful 60% and irritated 40%).

The thought that scores the highest is the causal thought – the base thought that caused the emotions – and should be addressed first.

Assess cognitive distortions

Review the TRs and complete the Exceptions to the Problem Questionnaire to understand how each one could be responded to differently. What happened when things were better?

Finding Discrepancies

Use the Finding Discrepancies Worksheet to challenge negative thoughts.

Understanding the impact of continuing with existing behavior is extremely valuable. What happens if I continue as I am versus taking a new, healthier approach?

Cognitive Restructuring Worksheet

Use Socratic questioning in the Cognitive Restructuring Worksheet to challenge irrational or illogical thinking. For example, ask yourself:

- Could I be misinterpreting the facts?

- How likely is this scenario?

- Could others have different perspectives?

Once complete, clients can determine whether they are misinterpreting facts or repeating a habit.

Facts or opinions

We often mistake subjective opinions for facts, leading to cognitive distortions about ourselves.

Use the Facts or Opinions Worksheet to practice how to differentiate between opinion and fact.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

Additional PositivePsychology.com Tools

PositivePsychology.com is a great source of information and help for Positive CBT .

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© provides various worksheets and exercises designed to help individuals conquer negative thinking.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others through CBT, this collection contains 17 validated positive CBT tools for practitioners. Use them to help others overcome unhelpful thoughts and feelings and develop more positive behaviors.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy provides a practical way to identify and challenge illogical and incorrect thought patterns.

To address a person’s unhelpful and often untrue beliefs, we must first capture their thoughts accurately and in sufficient detail. Thought Records are an invaluable and proven aid in capturing automatic thinking that can plague us and appear believable, despite being unreliable (McManus et al., 2012).

Paying attention to what is running through our minds – thoughts and pictures – when feelings and situations change can become a positive habit, helped by writing them down.

Capturing the situation, thought, and emotion to check its accuracy begins the process of changing the way we think.

Is there a more helpful way to think about myself and what has happened ? Most likely, yes .

Use Thought Records to collect data about your clients’ specific thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, and plan a strategy for overcoming their difficulties. Include problem solving and changes to thinking and behavior to help them build a better life.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. For more information, don’t forget to download our three Positive CBT Exercises for free .

- Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond . Guilford Press.

- McManus, F., Van Doorn, K., & Yiend, J. (2012). Examining the effects of thought records and behavioral experiments in instigating belief change. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry , 43 (1), 540–547.

- American Psychological Association (2017). What is cognitive behavioral therapy? Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder . Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/patients-and-families/cognitive-behavioral

- Widnall, E., Price, A., Trompetter, H., & Dunn, B. D. (2019). Routine cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety and depression is more effective at repairing symptoms of psychopathology than enhancing wellbeing. Cognitive Therapy and Research , 44 , 28–39.

- Wilding, C. (2015). Cognitive behavioural therapy: Techniques to improve your life . Quercus.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Thank you for all the information

What happened? I was not able to download the PDF of worksheets from your newsletter. Indicated the email address had already been used. Of course it has!! I get your newsletter!!!!

Thanks for reaching out – we are sorry that you are experiencing this! If you have still not received the worksheets, please email our customer support team at [email protected] , and they will help you immediately!

Kind regards, -Caroline | Community Manager

Thank you! The article was very insightful. The process to challenge the negative thinking so beneficial. I intend to read it again.

It was very useful.I feel use of CBT will certainly help a person to think in different ways whichvwill help them to be at peace.Thank you foe providing examples to understand the process of CBT. How can we effectively use this technique to treat adults with mobile or TV addiction.

Hi Vatsala,

Glad you found the post useful. That’s a tricky question. Research on mobile and TV addiction is still in the early stages, so I’m not sure how much work is out there linking the practice of thought records to treating these addictions. You may find it helpful to do a search for CBT-IA (internet addiction), which will cover different CBT techniques that apply to internet usage (and mobile phones by extension). You’ll also find a review on treatments for television addiction here .

I hope this helps a little!

– Nicole | Community Manager

Thank you. It’s very practical skills.

I enjoy reading this article. Very insightful.

thanks so much for those examples. very easy way to understand CBT concepts.

Thank you a whole lot for reminding me of this valuable thought correction process. Have a great day and year.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Fundamental Attribution Error: Shifting the Blame Game

We all try to make sense of the behaviors we observe in ourselves and others. However, sometimes this process can be marred by cognitive biases [...]

Halo Effect: Why We Judge a Book by Its Cover

Even though we may consider ourselves logical and rational, it appears we are easily biased by a single incident or individual characteristic (Nicolau, Mellinas, & [...]

Sunk Cost Fallacy: Why We Can’t Let Go

If you’ve continued with a decision or an investment of time, money, or resources long after you should have stopped, you’ve succumbed to the ‘sunk [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (21)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (19)

- Positive Parenting (16)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (18)

- Relationships (44)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Positive CBT Exercises (PDF)

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Low-intensity CBT Skills and Interventions a practitioner's manual

- Paul Farrand - CEDAR; University of Exeter

- Description

This book takes you step-by-step through the Low-intensity CBT interventions, competencies and clinical procedures. It provides a comprehensive manual for trainee and qualified Psychological Wellbeing Practitioners within NHS Talking Therapies anxiety and depression services or for other roles that support Low-intensity CBT.

New to this edition:

- Updated research and references

- Updated further reading and resources

- New chapters covering the different modalities available for remote LI-CBT and their benefits and drawbacks: telephone, email, and video

- New chapter on CBT Self-help in Groups

- New chapter on Working with People from Ethnic Minority Backgrounds

- New chapter on Working with Long-term Health Conditions

- Updated chapter on patient Assessment

- Updated chapter on Clinical Decision-Making

- Revised chapter on Using Behaviour Change Models

- Updated to reflect changes in the new LI-CBT National Curriculum

Supplements

Student Resources (Free to access)

1. Worksheet templates and short exercises for a patient to work through independently or a practitioner and patient to work through together are available at https://study.sagepub.com/farrand 2e

7.1 Example of a relapse prevention worksheet

12.1 Reflection record for use in clinical skills supervision

14.1 Behavioural activation schedule

14.2 Example of a classifying activity worksheet

14.3 Example of an activity grading worksheet

15.1 Thought diary

15.2 Evidence recording and revised thought

15.3 Behavioural experiments plan

15.4 Behavioural experiments review

17.1 Exposure goal diary

18.1 Jordan’s areas of my life that are really important to me

18.2 Jordan’s worry worksheet

18.3 Jordan’s my types of worry

18.4 Jordan’s my worry time

18.5 My worry time review 1

19.1 Example of an LICBT problem-solving worksheet

19.2 Jamie’s problem list

19.3 Jamie’s problem selection and potential solutions – in book but missing from worksheets

19.4 Advantages and disadvantages analysis

20.1 Sleep diary

20.2 Stimulus control worksheet

20.3 Stimulus restriction worksheet

24.1 Physical symptom diary

2. Workbooks and resources that Psychological Wellbeing Practitioners (PWP) can use in low-intensity training and practice with patients. They cover topics such as ‘Managing Your Worry’, ‘Unhelpful Thoughts’, ‘Facing Your Fears’ and support the specific interventions described in the chapters. Available at https://cedar.exeter.ac.uk/resources/iaptinterventions/

5.1 The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies Manual

5.2 Common Mental Health Disorders: Identification and Pathways to Care

12.1 IAPT Supervision Guidance

14.1 Get Active, Feel Good Workbook

14.2 Get Active, Feel Good: Helping Yourself to Get on Top of Low Mood Workbook

14.3 Case study: Jane

14.4 Case study: Mark 12.1 Unhelpful Thoughts: Challenging and Testing Them Out Workbook

15.1 Unhelpful Thoughts: Challenging and Testing Them Out Workbook

16.1 Facing Your Fears Workbook

17.1 Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: A Self-Help Book

18.1 Managing Your Worries Workbook

19.1 From Problems to Solutions Workbook

3. Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: A Self-Help Book (Lovell and Gega, 2011) is from the University of Manchester: https://documents.manchester.ac.uk/display.aspx?DocID=47030

This book provides LI IAPT trainee and practitioners need a step-by-step guide to clinical protocols and interventions, covering assessment, decision-making and the seven key interventions.

This books provides granular information on how to implement LI CBT, including suggested phrases, tips for trouble-shooting, worksheets and workbooks to support the interventions. This new edition is also updated to reflect changes in the new LI-CBT National Curriculum

Preview this book

For instructors.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 21 May 2024

Investigating nutrient biomarkers of healthy brain aging: a multimodal brain imaging study

- Christopher E. Zwilling ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2873-0115 1 , 2 ,

- Jisheng Wu ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0003-6000-453X 3 , 4 , 5 &

- Aron K. Barbey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6092-0912 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6

npj Aging volume 10 , Article number: 27 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

539 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cognitive ageing

The emerging field of Nutritional Cognitive Neuroscience aims to uncover specific foods and nutrients that promote healthy brain aging. Central to this effort is the discovery of nutrient profiles that can be targeted in nutritional interventions designed to promote brain health with respect to multimodal neuroimaging measures of brain structure, function, and metabolism. The present study therefore conducted one of the largest and most comprehensive nutrient biomarker studies examining multimodal neuroimaging measures of brain health within a sample of 100 older adults. To assess brain health, a comprehensive battery of well-established cognitive and brain imaging measures was administered, along with 13 blood-based biomarkers of diet and nutrition. The findings of this study revealed distinct patterns of aging, categorized into two phenotypes of brain health based on hierarchical clustering. One phenotype demonstrated an accelerated rate of aging, while the other exhibited slower-than-expected aging. A t-test analysis of dietary biomarkers that distinguished these phenotypes revealed a nutrient profile with higher concentrations of specific fatty acids, antioxidants, and vitamins. Study participants with this nutrient profile demonstrated better cognitive scores and delayed brain aging, as determined by a t-test of the means. Notably, participant characteristics such as demographics, fitness levels, and anthropometrics did not account for the observed differences in brain aging. Therefore, the nutrient pattern identified by the present study motivates the design of neuroscience-guided dietary interventions to promote healthy brain aging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Alzheimer’s disease risk reduction in clinical practice: a priority in the emerging field of preventive neurology

Associations of dietary patterns with brain health from behavioral, neuroimaging, biochemical and genetic analyses

Temporal dynamics of the multi-omic response to endurance exercise training

Introduction.

Accumulating evidence in Nutritional Cognitive Neuroscience indicates that diet and nutrition may benefit the aging brain (for a review, see ref. 1 ). A recent review of the literature surveyed 52 studies comprising more than 21,000 participants and found that dietary markers of the Mediterranean Diet were associated with healthy brain aging, as measured by MRI indices of structural and functional connectivity 2 . Despite the promise of these findings, questions remain about the causal effects of diet and nutrition on brain health and their role in age-related neurobiological decline; for example, whether elements of the Mediterranean Diet, such as polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), may limit the reduction in white matter volume with age. The potential benefits of the Mediterranean Diet may result from its focus on nutrient classes that have known functional relationships with the brain. For example, fatty acids, including monounsaturated, polyunsaturated, and saturated fatty acids, are necessary for structural brain integrity and development, cellular energy metabolism, and neurotransmission and neuromodulation 3 . Indeed, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) examining the effects of fatty acids on brain health typically observe improvements in brain function, white matter integrity, and gray matter volume 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 . Notably, however, RCTs that investigate the effects of fatty acids on cognitive performance (without additional measures of brain health) demonstrate mixed results, with positive 8 or null findings 9 . In addition to fatty acids, the Mediterranean Diet includes antioxidants (i.e., vitamins, flavonoids, and carotenoids), which are known to reduce oxidative stress and therefore to benefit brain health 10 , 11 . RCTs examining the effects of antioxidants on the aging brain demonstrate benefits in cerebral blood flow and for measures of functional brain connectivity (e.g., functional brain network integration 12 ). Evidence further suggests that antioxidants may have favorable effects on episodic memory, although these findings do not extend to all forms of memory affected by aging 7 , 13

More broadly, a large association study of ~75,000 participants revealed that greater consumption of antioxidants was associated with a lower chance of developing subjective cognitive impairment in late life 14 . Finally, research also suggests that choline, an essential nutrient that promotes structural brain integrity, cellular energy metabolism, and neurotransmission, may improve multiple facets of cognition in older adults 15 . Taken together, these findings suggest that nutrition may support and enhance cognitive function and brain health, especially in healthy older adults.

The potential for nutritional interventions to promote healthy brain function is particularly significant given the well-established effects of aging on cognitive performance and brain health 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 . Senescence is accompanied by age-related neurodegeneration in gray and white matter structures and an increase in ventricular space 22 . White matter fiber integrity declines with age, as indexed by decreased fractional anisotropy and increases in axial, radial, and mean diffusivity 23 . Concentrations of metabolic markers of neuronal integrity, measured by magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), also decline with age 22 . Advancing age is associated with smaller cerebral volume, likely due to cortical neuronal degeneration and synaptic density reduction, in addition to reduced cortical thickness and surface area 24 , 25 . The observed changes in the aging brain are also known to affect cognitive function, producing declines in cognitive control, fluid intelligence, processing speed, and memory 21 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 .

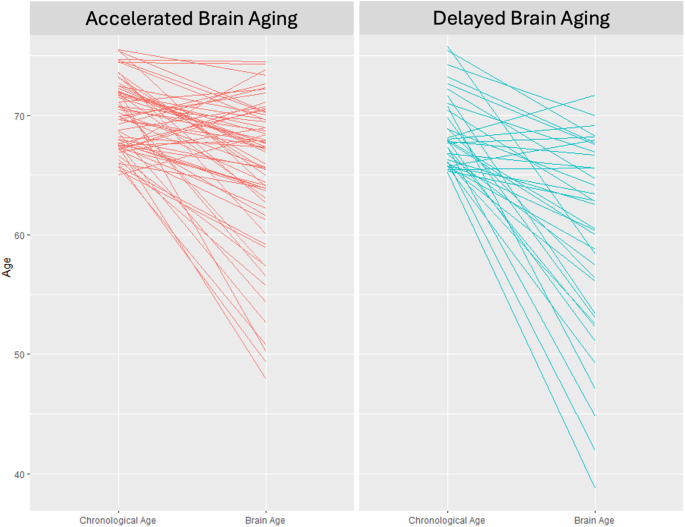

Age-related changes in brain health are known to vary within the population, reflecting individual differences in the onset, duration, and severity of age-related neurological symptoms 19 , 30 , 31 . Thus, chronological age alone does not fully explain the complex trajectory of brain health in late life. Indeed, recent evidence demonstrates that although structural MRI measures can predict chronological age, there are often deviations in the predicted and observed aging trajectory, such that accelerated aging results in a brain that is older than expected, whereas delayed aging results in a brain that is younger than predicted 32 , 33 .

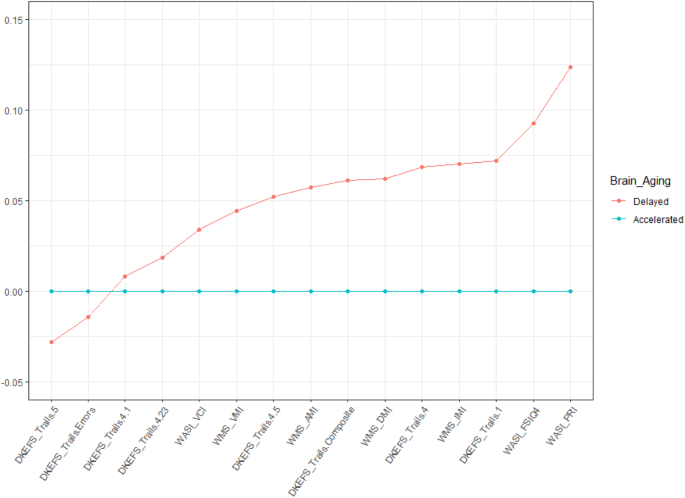

Although the literature on healthy aging has identified important risk factors that accelerate brain aging, much less is known about preventative factors that reduce the severity of neurobiological disease in late life 34 . Our research therefore sought to identify nutrient biomarker patterns that are associated with Accelerated versus Delayed Brain Aging, with an interest in guiding the development of nutritional interventions designed to promote healthy brain aging. Specifically, the present study was motivated by three primary aims. First, we sought to identify distinct phenotypes of Accelerated versus Delayed Brain Aging within a sample of 100 healthy older adults. Brain imaging measures were acquired from a comprehensive battery of over 100 neuroimaging markers of brain health, including measures of brain structure (i.e., volumetrics and white matter tracts), functional brain connectivity, and brain metabolites, as measured by MRS. Second, using a well-validated neuropsychological test battery, we compared performance on measures of intelligence, executive function, and memory in the Accelerated versus Delayed Brain Aging phenotypes. Finally, we investigated whether the observed phenotypes captured distinct nutrient biomarker profiles, with a focus on nutrients that are known to have favorable effects on cognitive function and brain health from the Mediterranean Diet (i.e., fatty acids, antioxidants, and vitamins).

We predicted that phenotypes of Accelerated versus Delayed Brain Aging would emerge, given well-established individual differences in brain aging trajectories. We also predicted that these distinct phenotypes would embody differences in cognitive function manifested by the observed differences in brain aging. Finally, our predictions about the role of nutrition in healthy brain aging were guided by findings to suggest that specific nutrients may benefit brain health, including poly- and mono-unsaturated fatty acids, vitamins, antioxidants, and carotenoids. Thus, by combining advances in Nutritional Cognitive Neuroscience—nutrient biomarkers of diet, multimodal brain imaging, and statistical modeling of brain aging—this interdisciplinary study aimed to identify nutrient profiles associated with Accelerated versus Delayed Brain Aging and to establish nutritional targets for future interventions designed to promote brain health.

Brain health phenotypes