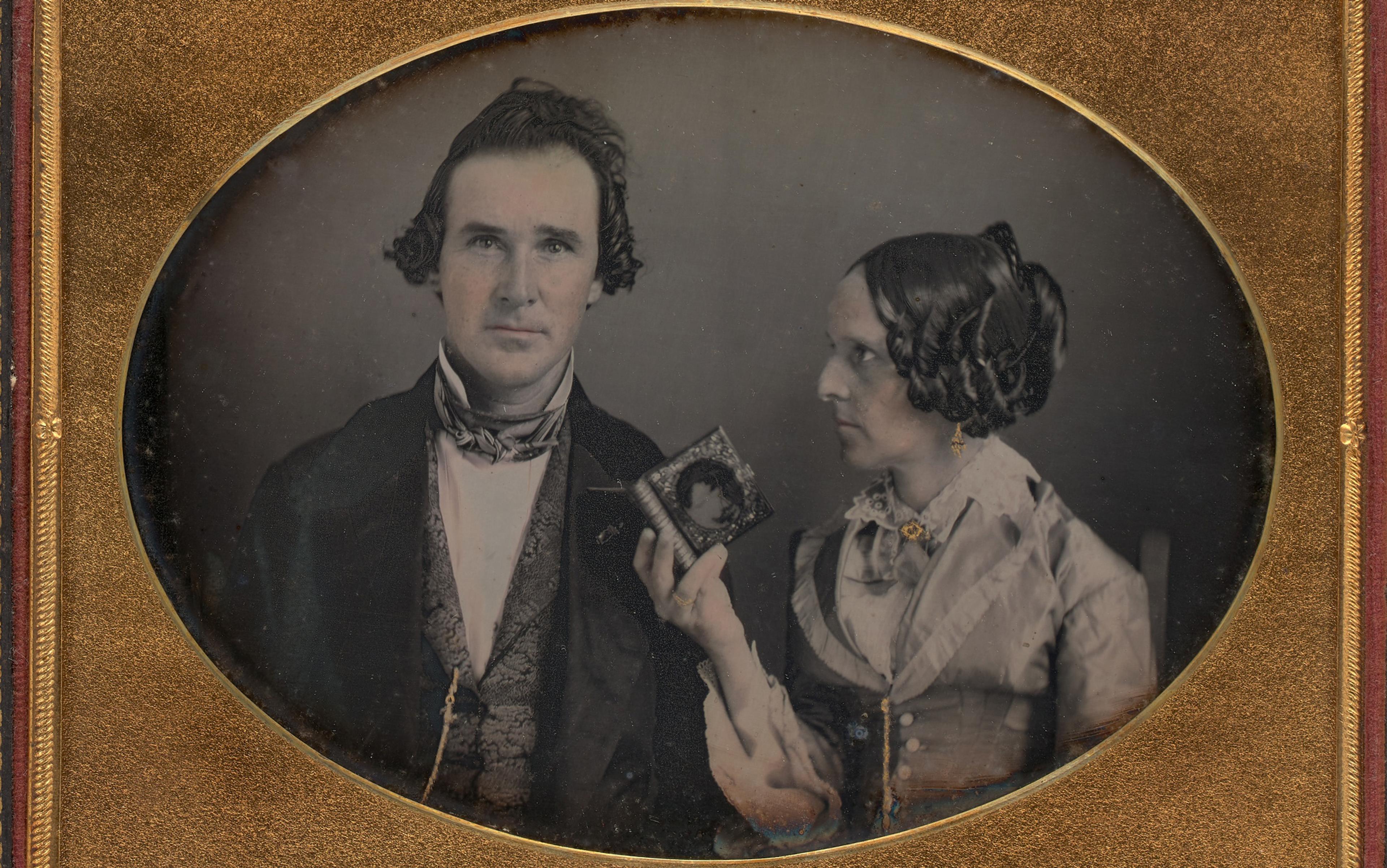

Untitled (Portrait of a Man and a Woman) (1851), daguerreotype, United States. Courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago

Tainted love

Love is both a wonderful thing and a cunning evolutionary trick to control us. a dangerous cocktail in the wrong hands.

by Anna Machin + BIO

We can all agree that, on balance, and taking everything into account, love is a wonderful thing. For many, it is the point of life. I have spent more than a decade researching the science behind human love and, rather than becoming immune to its charms, I am increasingly in awe of its complexity and its importance to us. It infiltrates every fibre of our being and every aspect of our daily lives. It is the most important factor in our mental and physical health, our longevity and our life satisfaction. And regardless of who the object of our love is – lover or friend, dog or god – these effects are largely underpinned, in the first instance, by the set of addictive neurochemicals supporting the bonds we create: oxytocin, dopamine, beta-endorphin and serotonin.

This suite of chemicals makes us feel euphoric and calm, they draw us towards those we love, and reward us for investing in our relationships, even when the going gets tough. Love feels wonderful but ultimately it is a form of biological bribery, a cunning evolutionary trick to make sure we cooperate and those all-important genes continue down the generations. The joy it brings is wonderful but is merely a side-effect. Its goal is to ensure our survival, and for this reason happiness is not always its end point. Alongside its joys, there exists a dark side.

Love is ultimately about control. It’s about using chemical bribery to make sure we stick around, cooperate and invest in each other, and particularly in the survival-critical relationships we have with our lovers, children and close friends. This is an evolutionary control of which we are hardly aware, and it brings many positive benefits.

But the addictive nature of these chemicals, and our visceral need for them, means that love also has a dark side. It can be used as a tool of exploitation, manipulation and abuse. Indeed, in part what may separate human love from the love experienced by other animals is that we can use love to manipulate and control others. Our desire to believe in the fairy tale means we rarely acknowledge the undercurrents but, as a scholar of love, I would be negligent if I did not consider it. Arguably our greatest and most intense life experience can be used against us, sometimes leading us to continue relationships with negative consequences in direct opposition to our survival.

We are all experts in love. The science I write about is always grounded in the lived experience of my subjects whose thoughts I collect as keenly as their empirical data. It might be the voice of the new father as he describes holding his firstborn, or the Catholic nun explaining how she works to maintain her relationship with God, or the aromantic detailing what it’s like living in a world apparently obsessed with the romantic love that they do not feel. I begin every interview in the same way, by asking what they think love is. Their answers are often surprising, always illuminating and invariably positive, and remind me that not all the answers to what love is can be found on the scanner screen or in the lab. But I will also ask them to consider whether love can ever be negative. The vast majority say no for, if love has a darker side, it is not love, and this is an interesting point to contemplate. But if they do acknowledge the possibility of love having a less sunny side, their go-to example is jealousy.

J ealousy is an emotion and, as with all emotions, it evolved to protect us, to alert us to a potential benefit or threat. It works its magic at three levels: the emotional, the cognitive and the behavioural. Physiology also throws its hat into the ring making you feel nauseous, faint or flushed. When we feel jealousy , it is generally urging us to do one of three things: to cut off the rival, to prevent our partner’s defection by redoubling our efforts, or to cut our losses and leave the relationship. All have evolved to make sure we balance the costs and benefits of the relationship. Investing time, energy and reproductive effort in the wrong partner is seriously damaging to your reproductive legacy and chances of survival. But what do we perceive to be a jealousy-inducing threat? The answer very much depends on your gender.

Men and women experience jealousy with the same intensity. However, there is a stark difference when it comes to what causes each to be jealous. One of the pioneers of human mating research is the American evolutionary psychologist David Buss and, in his book The Evolution of Desire (1994), he details numerous experiments that have highlighted this gender difference. In one study, in which subjects were asked to read different scenarios detailing incidences of sexual and emotional infidelity, 83 per cent of women found the emotional scenario the most jealousy-inducing, whereas only 40 per cent of men found this to be of concern. In contrast, 60 per cent of men found sexual infidelity difficult to deal with, compared with a significantly smaller percentage of women: 17 per cent.

Men also feel a much more extreme physiological response to sexual infidelity than women do. Hooking them up to monitors that measure skin conductance, muscle contraction and heartrate shows that men experience significant increases in heartrate, sweating and frowning when confronted with sexual infidelity, but the monitor readouts hardly flicker if their partner has become emotionally involved with a rival.

The reason for this difference sits with the different resources that men and women bring to the mating game. Broadly, men bring their resources and protection; women bring their womb. If a woman is sexually unfaithful and becomes pregnant with another man’s child, she has withdrawn the opportunity from her partner to father a child with her for at least nine months. Hence, he is the most concerned about sexual infidelity. In contrast, women are more concerned about emotional infidelity because this suggests that, if their partner does make a rival pregnant and becomes emotionally involved with her, his partner risks having to share his protection and resources with another, meaning that her children receive less of the pie.

To understand someone’s emotional needs means you can use that intelligence to control them

Jealousy is an evolved response to threats to our reproductive success and survival – of self, children and genes. In many cases, it is of positive benefit to those who experience it as it shines a light on the threat and enables us to decide what is best. But in some cases, jealousy gets out of hand.

Emotional intelligence sits at the core of healthy relationships. To truly deliver the benefits of the relationship to our partner, we must understand and meet their emotional needs as they must understand and meet ours. But, as with love, this skill has a darker side because to understand someone’s emotional needs presents the possibility that you can use that intelligence to control them. While we may all admit to using this skill for the wrong reasons every now and again – perhaps to get that sofa we desire or the holiday destination we prefer – for some, it is their go-to mechanism where relationships are concerned.

The most adept proponents of this skill are those who possess the Dark Triad of personality traits: Machiavellianism , psychopathy and narcissism . The first relies on using emotional intelligence to manipulate others, the second to toy with other’s feelings, and the third to denigrate others with the aim of glorifying oneself. For these people, characterised by exploitative, manipulative and callous personalities, emotional intelligence is the route to a set of mate-retention behaviours that certainly meet their goals but are less than beneficial to those whom they profess to love. Indeed, research has shown that a relationship with such a person leaves you open to a significantly greater risk that your love will be returned with abuse.

In 2018, the psychologist Razieh Chegeni and her team set out to explore whether a link existed between the Dark Triad and relationship abuse. Participants were identified as having the Dark Triad personality by expressing their degree of agreement with statements such as ‘I tend to want others to admire me’ (narcissism), ‘I tend to be unconcerned with the morality of my actions’ (psychopathy) and ‘I tend to exploit others to my own end’ (Machiavellianism). They then had to indicate to what extent they used a range of mate-retention behaviours, including ‘snooped through my partner’s personal belongings’, ‘talked to another man/woman at a party to make my partner jealous’, ‘bought my partner an expensive gift’ and ‘slapped a man who made a pass at my partner’.

The results were clear. Having a Dark Triad personality, whether you were a man or a woman, significantly increased the likelihood that ‘cost-inflicting mate-retention behaviours’ were your go-to mechanism when trying to retain your partner. These are behaviours that level an emotional, physical, practical and/or psychological cost on the partner such as physical or emotional abuse, coercive control or controlling access to food or money. Interestingly, however, these individuals did not employ this tactic all the time. There was nuance in their behaviour. Costly behaviours were peppered with rare incidences of gift giving or caretaking, so-called beneficial mate-retention behaviours. Why? Because the unpredictability of their behaviour caused psychological destabilisation in their partner and enabled them to assert further control through a practice we now identify as gaslighting .

The question remains – if these people are so destructive, why does their personality type persist in our population? Because, while their behaviour may harm those who are unfortunate enough to be close to them, they themselves must gain some survival advantage, which means that their traits persist in the population. It is true that no trait can be said to be 100 per cent beneficial, and here is a perfect example of where evolution is truly working at cross purposes.

N ot all Dark Triad personalities are abusers but the presence of abuse within our closest relationships is a very real phenomenon, the understanding of which continues to evolve and grow. Whereas we might have once imagined an abuser as someone who controlled their partner with their fists, we are now aware that abuse comes in many guises including emotional, psychological, reproductive and financial.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) questioned both men and women in the United States about the incidences of domestic violence they had experienced in their lifetime. Looking at severe physical abuse alone – which means being punched, slammed, kicked, burned, choked, beaten or attacked with a weapon – one in five women and one in seven men reported at least one incidence in their lifetime. If we consider emotional abuse, then the statistics for men and women are closer – more than 43 million women and 38 million men have experienced psychological aggression by an intimate partner in their lifetime.

It is hard to imagine that, having experienced such a litany of abuse, anyone could believe that love remained within their relationship. But here the power of the lived experience, of allowing everyone to have their ideas about love becomes clearer. Because, while we have many scientific tools to explore love objectively, at the end of the day, there is always an element of our experience of love that is subjective, that another cannot touch. This is no more powerfully evidenced than by the testimony of those who have experienced intimate partner violence. In 2013, three mental health nurses, led by Marilyn Smith in West Virginia, explored what love meant to 19 women who were experiencing, or had experienced, intimate partner violence. For them, this kind of abuse included, but was not limited to, ‘slapping, intimidation, shaming, forced intercourse, isolation, monitoring behaviours, restricting access to healthcare, opposing or interfering with school or employment, and making decisions concerning contraception, pregnancy, and elective abortion’.

Our cultural ideas of romantic love have a role to play in trapping women in abusive relationships

It was clear from the transcripts that all the women knew what love wasn’t: being hurt and fearful, being controlled and having a lack of trust and a lack of support or concern for their welfare. And it was clear that they all knew what love should be: built on a foundation of respect and understanding, of support and encouragement, of commitment, loyalty and trust. But despite this clear understanding of the stark difference between the ideal and their reality, many of these women still believed that love existed within their relationship. Some hoped the power of their love would change the behaviour of their partner, others said their sense of attachment made them stay. Some feared losing love, however flawed; and, if they left, might they not land in a relationship where their treatment was even worse? A lot of the time, cultural messaging had reinforced strongly held beliefs about the supremacy of the nuclear family, making victims reluctant to leave in case they ultimately harmed their children’s life chances. While it can be hard to understand these arguments – surely a non-nuclear setup is preferable to the harm inflicted on a child by the observation of intimate partner abuse – I strongly believe that this population has as much right to their definition and experience of love as any of us.

In fact, the cultural messages we hear about romantic love – from the media, religion, parents and family – not only potentially trap us in ‘ideal’ family units: they may also play a role in our susceptibility to experiencing intimate partner abuse. This view of reproductive love, once confined to Western culture, is now the predominant narrative globally. From a young age, we speak of ‘the one’, we consume stories of young people finding love against all the odds, of sacrifice, of being consumed. It is arguable that these narratives are unhelpful generally as the reality, while wonderful, is considerably more complex, involving light and shade. But research has shown that these stories may have more significant consequences when we consider their role in intimate partner abuse.

South Africa has one of the highest rates of partner abuse against women in the world. In their 2017 paper , Shakila Singh and Thembeka Myende explored the role of resilience in female students at risk of abuse, which is prevalent at a high rate on South African university campuses. Their paper ranges widely over the role of resilience in resisting and surviving partner abuse, but what is of interest to me is the 15 women’s ideas about how our cultural ideas of romantic love have a role to play in trapping women in abusive relationships. These women’s arguments are powerful and made me rethink the fairy-tale. Singh and Myende point to the romantic idea that love overcomes all obstacles and must be maintained at all costs, even when abuse makes these costs life-threateningly high. Or the idea that love is about losing control, being swept off your feet, having no say in who you fall for, even if they turn out to be an abuser. Or that lovers protect each other, fight for each other to the end, even if the person who is being protected, usually from the authorities, is violent or coercive. Or the belief that love is blind and we are incapable of seeing our partner’s faults, despite them often being glaringly obvious to anyone outside the relationship.

It is these cultural ideas about romantic love, the women argue, that lead to the erosion of a woman’s power to leave or entirely avoid an abusive partner. Add these ideas to the powerful physiological and psychological need we have for love, and you leave an open goal for the abuser.

L ove is the focus of so much science, philosophy and literary rumination because we struggle to define it, to predict its next move. Thanks to our biology and the reproductive mandate of evolution, love has long controlled us. But what if we could control love?

What if a magic potion existed that could induce us, or another, to fall in love or even wipe away the memories of a failed relationship? It is a quest as ancient as the first writings 5,000 years ago and the focus of many literary endeavours, including Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream – who can forget Titania’s love for the ass-headed Bottom – and Wagner’s opera Tristan and Isolde . Even in a world where science has largely usurped magic, type ‘love potions’ into Google and the first two questions are: ‘How do you make a love potion?’ and ‘Do love potions actually work?’

But today we know enough about the chemistry of love for the elixir to be within our grasp. And we don’t have to look very far for our first candidate: synthetic oxytocin, used right now as an induction drug in labour. We know from extensive research in social neuroscience that artificial oxytocin also increases prosociality, trust and cooperation. Squirt it up the nose of new parents and it increases positive parenting behaviours. Oxytocin, as released by the brain when we are attracted to someone, is vital for the first stages of love because it quiets the fear centre of your brain and lowers your inhibitions to forming new relationships. Would a squirt up the nose do the same before you head out on a Saturday night?

The other possibility is MDMA or ecstasy, which mimics the neurochemical of long-term love, beta-endorphin. Recreational users of ecstasy report that it makes them feel boundless love for their fellow clubbers and increases their empathy. Researchers in the US have reported encouraging results when MDMA was used in marriage therapy to increase empathy, allowing participants to gain further insight into each other’s needs and find common ground.

Love drugs could end up being yet another form of abuse

Both of these sound like promising candidates but there are still issues to iron out and ethical discussions to have. How effective they are is highly context dependent. Based on their genetics , some people do exactly what is predicted of them. Boundaries are lowered and love sensations abound. But for a significant minority, particularly when it comes to oxytocin, people do exactly the opposite of what we would expect. For some, a dose of oxytocin, while increasing bonds with those they perceive to be in their in-group, increases feelings of ethnocentrism – racism – toward the out-group.

MDMA has other issues . For some people, it simply does not work. But the bigger problem is that the effects endure only while usage continues; anecdotal evidence suggests that, if you stop, the feelings of love and empathy disappear. This raises questions of practicality and ethical issues surrounding power imbalance. If you commenced a relationship while taking MDMA, would you have to continue? What if you were in a relationship with someone who had taken MDMA and you didn’t know? What would happen if they stopped? And could someone be induced to take MDMA against their will?

The ethical conversation around love drugs is complex. On one side are those who argue that taking a love drug is no more controversial than an antidepressant. Both alter your brain chemistry and, given the strong relationship between love and good mental and physical health, surely it is important that we use all the tools at our disposal to help people succeed? But maybe an anecdote from the book Love Is the Drug (2020) by Brian Earp and Julian Savulescu will give you pause. They describe SSRI prescriptions used to suppress the sexual urges of young male yeshiva students, to ensure that they comply with Jewish orthodox religious law – no sex before marriage, and definitely no homosexuality.

Could such drugs gain wider traction in repressive regimes as a weapon against what some perceive to be immoral forms of love? Remember that 71 countries still deem homosexuality to be illegal. It is not a massive leap of imagination to envisage the use of SSRIs to ‘cure’ people of this ‘affliction’. We only have to look at the continued existence of conversion therapy to see that this is a distinct possibility. Love drugs could end up being yet another form of abuse over which the individual has very little control.

Evolution saw fit to give us love to ensure we would continue to form and maintain the cooperative relationships that are our route to personal and, most crucially, genetic survival. It can be the source of euphoric happiness, calm contentment and much-needed security, but this is not its point. Love is merely the sweet treat handed to you by your babysitter to make sure the goal is achieved. Combine the ultimate evolutionary aim of love with our visceral need for it and the quick intelligence of our brains, and you have the recipe for a darker side to emerge. Some of this darker side is adaptive but, for those who experience it, it rarely ends well. At the very least there is pain – physical, psychological, financial – and, at the most, there is death, and the grief of those we leave behind.

Maybe it is time to rewrite the stories we tell ourselves about love because the danger on the horizon is not the dragon that needs to be slain by the knight to save the beautiful princess but the presence of some who mean to use its powers for their gain and our considerable loss. Like all of us, love is a complex beast: only by embracing it in its entirety do we truly understand it, and ourselves. And this means understanding its evolutionary story, the good and the bad.

Metaphysics

Many worlds, many selves

If it’s true that we live in a vast multiverse, then our understanding of identity, morality and even God must be reexamined

Emily Qureshi-Hurst

Biography and memoir

A grief with no name

As a child, I was torn from a culture that I never knew. It is a loss that defines me, even as I struggle to define the loss

Jelena Markovic

Could humans hibernate?

Hibernation allows many animals to time-travel from difficult times to plenty. Could humans learn how to do it too?

Vladyslav Vyazovskiy

The cochlear question

As the hearing parent of a deaf baby, I’m confronted with an agonising decision: should I give her an implant to help her hear?

Abi Stephenson

Philosophy of science

The nature of natural laws

Physicists and philosophers today have formulated three opposing models that explain how laws work. Which is the best?

Mario Hubert

Technology and the self

We need raw awe

In this tech-vexed age, our life on screens prevents us from experiencing the mysteries and transformative wonder of life

Kirk Schneider

- Relationships

10 Reasons Why Romantic Love Can Be So Dangerous

Part 1: regardless of your age, romantic love activates your inner adolescent..

Posted August 11, 2021 | Reviewed by Lybi Ma

- Why Relationships Matter

- Take our Relationship Satisfaction Test

- Find counselling to strengthen relationships

- Love should involve emotion and reason; but regrettably, your rational faculties can be swept away by powerful amorous feelings.

- By too readily trusting your beloved, should the relationship end badly, placing so much confidence in them can come back to haunt you.

- Distracted by the thrilling “high” of courtship, women may give up or postpone their pre-romantic plans, which they may later regret.

- If you marry your beloved, you’ll soon realize they were never as “special” as—in your dreamy-eyed “love-sightedness”—you believed they were.

Romantic love is typically the most exciting experience you’ll ever have. What could be more thrilling, more gratifying, or (in endorphin production) more chemically rewarding? Still, many dangers link to this love. It frequently culminates in disappointment, hurt, regret, or—at its worst—despair. Here are 10 examples of its negative potential:

1. By altering your consciousness, love can lead you to feel, and act, off-balance. The descriptive phrases “ falling in love” or “ head over heels in love” testify to how easily this euphoric state can “trip you up.” It can make you behave “lopsidedly” to situations that realistically hardly warrant such a reaction.

The expression, “love is blind,” additionally alludes to not being able to see straight, indicating a myopic vision prompting you to ignore details that could be crucial.

2. When powerful feelings about your beloved not only dim your clear-sightedness but also what your friends and relatives may be telling you, the chances of making a beguiled mistake increase further. Others may be much more aware of critical warning signs that, amorously (or stubbornly) viewing your partner through a heavily biased, favorable filter, cause you to discount or dismiss their concerns.

3. There’s a strangely involuntary, uncontrollable aspect to romantic love. With a diminished ability to think logically about what’s happening to you, you may not be able to grasp the irrational dynamics of your inordinate passion. And regrettably, this emotionally or lustfully charged attraction might well oppose your (no-longer-accessible) better judgment and not at all reflect your basic values.

4. It could be that when you speak to, or even think about, the person you’re in love with, you feel tense, uneasy, and nervous—even when there’s no one on earth you’d rather be with. And, however ironic, it’s well known that “highs” can produce as much stress as “lows.”

5. Your ability to think lucidly is compromised when you’re full of romantic feelings. Ideally, love should involve emotion and reason, the two coming together in a manner that makes rational sense. But your rational faculties can be swept away when amorous feelings take you over.

6. It can threaten, or undermine, your integrity. If your self-acceptance is limited, inflicted with notions (real or not) of not being good enough, you’ll hide from your partner whatever qualities you associate with personal weakness or inadequacy. Unwilling to risk criticism or rejection, you’ll edit your behavior accordingly, only letting yourself be known to the degree it feels relationally safe.

But risk-reducing stratagems can’t be maintained indefinitely. If the relationship becomes longer-term, your actual (vs. imagined) deficits will become increasingly evident, jeopardizing the relationship.

7. Trusting someone is never without danger. In romantic love, when you’re over -confident about your partner’s unconditional acceptance, you’ll likely bare your soul to them, taking risks you probably wouldn’t take with anybody else. By all-too-readily extending such trust, should the relationship end badly your prematurely placing so much confidence in them can come back to haunt you.

8. Closely related to the above is that if the relationship is cut short, you’ll likely become more cynical. And although this increased skepticism may protect you from dashing headlong into another misguided relationship, researchers have connected a suspicious attitude to a shorter lifespan, and less happiness generally. Furthermore, because trusting others represents a fundamental human need, what you presumably learned from your intensely painful disillusionment can make it much harder to trust a prospective mate going forward.

9. In a romantic relationship , it’s normal to become preoccupied with your love object. Your hopes, dreams , and fears can be so absorbing that you may not be able to adequately attend to other responsibilities and commitments—like your studies, vocation, and other important relationships and pursuits. But disregarding what remains key to your personal and professional welfare is perilous, it can lead you to fail a course, get fired from your job, and so on.

It cannot be emphasized enough that romantic interests ought to be balanced by (non- narcissistic ) self-interests. Nonetheless, that can be a real challenge if you’re not sufficiently secure about being the other’s equal.

10. As pertains specifically to single women, Bella DePaulo, referring to several studies on the subject, reports that the career aspirations of many women end up taking a backseat to an all-consuming romantic relationship. Seduced by the extraordinary high experienced during courtship, they may give up or postpone pre-romantic plans. And later they may come to regret the "all for love" mentality that so distracted them from what earlier had been their foremost priority.

Doubtless, from your own experience of being in love you can think of more reasons to be cautious about its consequent thoughts and feelings, which can negatively affect your better judgment. My next post will list an additional 10 reasons. But right now you might want to add to the present list, to see how many of them dovetail with my upcoming post.

© 2021 Leon F. Seltzer, Ph.D. All Rights Reserved.

Capulet, S. (2019, Feb 11). Why We’re Obsessed With Romantic Love and Why It’s Dangerous. https://thoughtcatalog.com/sarah-capulet/2019/02/why-were-obsessed-with…

DePaulo, B. ( 2018, Nov 7). In Love With Romantic Love? That Comes With Risks. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/living-single/201811/in-love-ro…

Foy, K. (2017, Oct 6), 6 Things That Seem Really Romantic in Your Relationship, But Are Actually Dangerous. https://www.alliant.edu/blog/dangerous-disease-love

How Romanticism Ruined Love (n.a. & n.d.) https://www.theschooloflife.com/thebookoflife/how-romanticism-ruined-lo…

Langrial, D. (2020, Nov 6). Being Romantic Is the Most Dangerous Thing a Man or Woman Can Do. https://medium.com/illumination/being-romantic-is-the-most-dangerous-th…

Raypole, C. (2020, Aug 5). 15 Ways Love Affects Your Brain and Body. https://www.healthline.com/health/relationships/effects-of-love

Seltzer, L. F. (2013, Jun 21). How Rational Are “Rational” Marriages? https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evolution-the-self/201306/how-r…

Seltzer, L. F. (2017, Sept 1). 15 Reasons to Be Wary About Falling in Love. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evolution-the-self/201709/15-re…

Seltzer, L. F. (2021, Aug 12). 10 More Reasons Why Romantic Love Can Be So Dangerous. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/node/1165305/preview

Shorr, L. (2021, Apr 20). It Must Be Love on the Brain: The Neuroscience of Love. http://www.stitchfashion.com/home//love-on-the-brain

Villasenor, C. (n.d.). The Dangerous Disease that is Love. https://www.alliant.edu/blog/dangerous-disease-love

Leon F. Seltzer, Ph.D. , is the author of Paradoxical Strategies in Psychotherapy and The Vision of Melville and Conrad . He holds doctorates in English and Psychology. As of mid-July 2024, Dr. Seltzer has published some 590 posts, which have received over 54 million views.

- Find Counselling

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United Kingdom

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

When we fall prey to perfectionism, we think we’re honorably aspiring to be our very best, but often we’re really just setting ourselves up for failure, as perfection is impossible and its pursuit inevitably backfires.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

Romeo and Juliet

William shakespeare.

“These violent delights have violent ends,” says Friar Laurence in an attempt to warn Romeo , early on in the play, of the dangers of falling in love too hard or too fast. In the world of Romeo and Juliet , love is not pretty or idealized—it is chaotic and dangerous. Throughout the play, love is connected through word and action with violence, and Romeo and Juliet ’s deepest mutual expression of love occurs when the “star-crossed lovers take their life.” By connecting love with pain and ultimately with suicide, Shakespeare suggests that there is an inherent sense of violence in many of the physical and emotional facets of expressing love—a chaotic and complex emotion very different from the serene, idealized sweetness it’s so often portrayed as being.

There are countless instances throughout Romeo and Juliet in which love and violence are connected. After their marriage, Juliet imagines in detail the passion she and Romeo will share on their wedding night, and invokes the Elizabethan characterization of orgasm as a small death or “petite mort”—she looks forward to the moment she will “die” and see Romeo’s face reflected in the stars above her. When Romeo overhears Juliet say that she wishes he were not a Montague so that they could be together, he declares that his name is “hateful” and offers to write it down on a piece of paper just so he can rip it up and obliterate it—and, along with it, his very identity, and sense of self as part of the Montague family. When Juliet finds out that her parents, ignorant of her secret marriage to Romeo, have arranged for her to marry Paris , she goes to Friar Laurence’s chambers with a knife, threatening to kill herself if he is unable to come up with a plan that will allow her to escape her second marriage. All of these examples represent just a fraction of the instances in which language and action conspire to render love as a “violent delight” whose “violent ends” result in danger, injury, and even death. Feeling oneself in the throes of love, Shakespeare suggests, is tumultuous and destabilizing enough—but the real violence of love, he argues, emerges in the many ways of expressing love.

Emotional and verbal expressions of love are the ones most frequently deployed throughout the play. Romeo and Juliet wax poetic about their great love for each other—and the misery they feel as a result of that love—over and over again, and at great lengths. Often, one of their friends or servants must cut them off mid-speech—otherwise, Shakespeare seems to suggest, Romeo and Juliet would spend hours trying to wrestle their feelings into words. Though Romeo and Juliet say lovely things about one another, to be sure, their speeches about each other, or about love more broadly, are almost always tinged with violence, which illustrates their chaotic passion for each other and their desire to mow down anything that stands in its way. When Romeo, for instance, spots Juliet at her window in the famous “balcony scene” in Act 2, Scene 2, he wills her to come closer by whispering, “Arise, fair sun ”—a beautiful metaphor of his love and desire for Juliet—and quickly follows his entreaty with the dangerous language “and kill the envious moon, Who is already sick and pale with grief.” Juliet’s “sun”-like radiance makes Romeo want her to “kill” the moon (or Rosaline ,) his former love and her rival in beauty and glory, so that Juliet can reign supreme over his heart. Later on in the play, when the arrival of dawn brings an end to Romeo and Juliet’s first night together as man and wife, Juliet invokes the symbol of a lark’s song—traditionally a symbol of love and sweetness—as a violent, ill-meaning presence which seeks to pull Romeo and Juliet apart, “arm from arm,” and “hunt” Romeo out of Juliet’s chambers. Romeo calls love a “rough” thing which “pricks” him like a thorn; Juliet says that if she could love and possess Romeo in the way she wants to, as if he were her pet bird, she would “kill [him] with much cherishing.” The way the two young lovers at the heart of the play speak about love shows an enormously violent undercurrent to their emotions—as they attempt to name their feelings and express themselves, they resort to violence-tinged speech to convey the enormity of their emotions.

Physical expressions of love throughout the play also carry violent connotations. From Romeo and Juliet’s first kiss, described by each of them as a “sin” and a “trespass,” to their last, in which Juliet seeks to kill herself by sucking remnants of poison from the dead Romeo’s lips, the way Romeo and Juliet conceive of the physical and sexual aspects of love are inextricable from how they conceive of violence. Juliet looks forward to “dying” in Romeo’s arms—again, one Elizabethan meaning of the phrase “to die” is to orgasm—while Romeo, just after drinking a vial of poison so lethal a few drops could kill 20 men, chooses to kiss Juliet as his dying act. The violence associated with these acts of sensuality and physical touch furthers Shakespeare’s argument that attempts to adequately express the chaotic, overwhelming, and confusing feelings of intense passion often lead to a commingling with violence.

Violent expressions of love are at the heart of Romeo and Juliet . In presenting and interrogating them, Shakespeare shows his audiences—in the Elizabethan area, the present day, and the centuries in-between—that love is not pleasant, reserved, cordial, or sweet. Rather, it is a violent and all-consuming force. As lovers especially those facing obstacles and uncertainties like the ones Romeo and Juliet encounter, struggle to express their love, there may be eruptions of violence both between the lovers themselves and within the communities of which they’re a part.

Love and Violence ThemeTracker

Love and Violence Quotes in Romeo and Juliet

Two households, both alike in dignity, In fair Verona, where we lay our scene, From ancient grudge break to new mutiny, Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean. From forth the fatal loins of these two foes, A pair of star-cross'd lovers take their life; Whose misadventured piteous overthrows, Doth with their death bury their parents' strife. The fearful passage of their death-mark'd love, And the continuance of their parents' rage, Which, but their children's end, nought could remove, Is now the two hours' traffic of our stage; The which if you with patient ears attend, What here shall miss, our toil shall strive to mend.

Why then, O brawling love! O loving hate! O any thing, of nothing first created; O heavy lightness! serious vanity! Mis-shapen chaos of well-seeming forms!

Oh, she doth teach the torches to burn bright! It seems she hangs upon the cheek of night Like a rich jewel in an Ethiope's ear, Beauty too rich for use, for earth too dear. So shows a snowy dove trooping with crows As yonder lady o'er her fellows shows. The measure done, I'll watch her place of stand, And, touching hers, make blessèd my rude hand. Did my heart love till now? Forswear it, sight! For I ne'er saw true beauty till this night.

You kiss by th’ book.

My only love sprung from my only hate! Too early seen unknown, and known too late!

But, soft! what light through yonder window breaks? It is the east, and Juliet is the sun!

O Romeo, Romeo! wherefore art thou Romeo? Deny thy father and refuse thy name; Or, if thou wilt not, be but sworn my love, And I'll no longer be a Capulet.

'Tis but thy name that is my enemy; — Thou art thyself though, not a Montague. What's Montague? It is nor hand, nor foot, Nor arm, nor face, nor any other part Belonging to a man. O, be some other name! What's in a name? That which we call a rose, By any other word would smell as sweet; So Romeo would, were he not Romeo call'd, Retain that dear perfection which he owes Without that title: — Romeo, doff thy name; And for thy name, which is no part of thee, Take all myself.

I take thee at thy word: Call me but love, and I'll be new baptis'd; Henceforth I never will be Romeo.

O, swear not by the moon, the inconstant moon, That monthly changes in her circled orb, Lest that thy love prove likewise variable.

Good-night, good-night! Parting is such sweet sorrow That I shall say good-night till it be morrow.

Romeo, the hate I bear thee can afford No better term than this: thou art a villain.

Romeo: Courage, man; the hurt cannot be much. Mercutio: No, 'tis not so deep as a well, nor so wide as a church-door; but 'tis enough, 'twill serve: ask for me to-morrow, and you shall find me a grave man.

O, I am fortune's fool!

Come, gentle night, — come, loving black brow'd night, Give me my Romeo; and when he shall die, Take him and cut him out in little stars, And he will make the face of Heaven so fine That all the world will be in love with night, And pay no worship to the garish sun.

Wilt thou be gone? it is not yet near day. It was the nightingale, and not the lark, That pierc'd the fearful hollow of thine ear; Nightly she sings on yond pomegranate tree. Believe me love, it was the nightingale.

Is there no pity sitting in the clouds That sees into the bottom of my grief? O sweet my mother, cast me not away! Delay this marriage for a month, a week, Or if you do not, make the bridal bed In that dim monument where Tybalt lies.

Or bid me go into a new-made grave, And hide me with a dead man in his shroud - Things that, to hear them told, have made me tremble - And I will do it without fear or doubt, To live an unstain'd wife to my sweet love.

Then I defy you, stars!

O true apothecary! Thy drugs are quick. — Thus with a kiss I die.

Yea, noise, then I'll be brief; O, happy dagger! This is thy sheath; there rest, and let me die.

For never was a story of more woe Than this of Juliet and her Romeo.

- Quizzes, saving guides, requests, plus so much more.

Lit. Summaries

- Biographies

Exploring the Perils of Passion: A Review of Dangerous Love (1996) by Ben Okri

In his 1996 book Dangerous Love, Nigerian author Ben Okri delves into the complex and often perilous nature of love. Through a series of interconnected stories set in Lagos, Okri explores the ways in which love can bring both joy and pain, and how it can be both a source of liberation and a trap. This review will examine Okri’s portrayal of love in Dangerous Love, and consider the book’s wider themes and messages.

Themes of Dangerous Love

One of the central themes of Dangerous Love is the idea that love can be a dangerous and destructive force. The novel explores the ways in which love can lead people to make irrational decisions and engage in destructive behavior. This theme is exemplified in the character of Omovo, who becomes obsessed with his love for Ifeyi, a woman who is already married. Omovo’s obsession with Ifeyi leads him to engage in reckless behavior, including stealing and violence. The novel also explores the idea that love can be a source of power and control, as seen in the character of Ifeyi’s husband, Osifo, who uses his love for her as a means of exerting control over her. Overall, Dangerous Love offers a complex and nuanced exploration of the perils of passion, highlighting the ways in which love can both inspire and destroy.

Analysis of Characters

In Dangerous Love, Ben Okri presents a cast of characters whose passions lead them down dangerous paths. The protagonist, Omovo, is a young artist who becomes infatuated with a mysterious woman named Ifeyiwa. His obsession with her leads him to neglect his own art and become entangled in a web of deceit and violence. Ifeyiwa herself is a complex character, with a past shrouded in mystery and a present filled with secrets. The novel also features a cast of supporting characters, including Omovo’s friend Kola and Ifeyiwa’s husband, who add depth and complexity to the story. Through his portrayal of these characters, Okri explores the ways in which passion can both inspire and destroy, and the dangers of becoming too consumed by one’s desires.

Okri’s Writing Style

Okri’s writing style in Dangerous Love is both poetic and philosophical. He weaves together vivid imagery and introspective musings to create a hauntingly beautiful narrative. His use of language is masterful, with each sentence carefully crafted to convey a deeper meaning. Okri’s writing is not just about telling a story, but about exploring the human condition and the complexities of love. He delves into the darker aspects of passion, exposing the perils that come with it. Through his writing, Okri challenges readers to question their own beliefs about love and the sacrifices they are willing to make for it. Overall, Okri’s writing style in Dangerous Love is a testament to his skill as a writer and his ability to create a thought-provoking and emotionally resonant story.

The Role of Fate in the Novel

In Dangerous Love, Ben Okri explores the role of fate in the lives of his characters. The novel is set in Nigeria during the 1970s, a time of political upheaval and social change. The main characters, Omovo and Ifeyiwa, are young lovers who are caught up in the tumultuous events of their time. They are both passionate and idealistic, but their love is threatened by the forces of fate that seem to be working against them. Okri uses the theme of fate to explore the idea that our lives are not entirely within our control, and that we are often at the mercy of forces beyond our understanding. Through the experiences of Omovo and Ifeyiwa, Okri shows us how love can be both a source of joy and a source of pain, and how the choices we make can have far-reaching consequences. Ultimately, Dangerous Love is a powerful meditation on the human condition, and a testament to the enduring power of love in the face of adversity.

Exploring the Concept of Love

Love is a complex and multifaceted concept that has been explored in literature, art, and philosophy for centuries. It is a feeling that can bring immense joy and happiness, but it can also lead to heartbreak and pain. In his novel Dangerous Love, Ben Okri delves into the darker side of love and the perils that can come with it. The book tells the story of a young couple, Omovo and Ifeyiwa, who fall deeply in love but are faced with numerous obstacles that threaten to tear them apart. Through their struggles, Okri explores the idea that love can be both beautiful and dangerous, and that it is often difficult to navigate the complexities of human relationships. As readers follow Omovo and Ifeyiwa’s journey, they are forced to confront their own ideas about love and the risks that come with it. Ultimately, Dangerous Love is a powerful exploration of the human heart and the many ways in which it can be both a source of joy and a source of pain.

The Dangers of Obsession

Obsession can be a dangerous thing. It can consume a person’s thoughts and actions, leading them down a path of destruction. In his novel Dangerous Love, Ben Okri explores the perils of passion and the consequences of obsession. The characters in the novel are driven by their desires, and their actions have devastating consequences. Okri’s novel serves as a cautionary tale, warning readers of the dangers of obsession and the importance of self-control. Whether it be an obsession with a person, an idea, or a goal, it is important to maintain a healthy balance and not let our passions consume us. The characters in Dangerous Love learn this lesson the hard way, and their experiences serve as a reminder to us all to be mindful of our own obsessions.

Symbolism in Dangerous Love

Symbolism plays a significant role in Ben Okri’s Dangerous Love. The novel is filled with various symbols that add depth and meaning to the story. One of the most prominent symbols in the novel is the river. The river represents the flow of life and the journey that the characters must take. It is also a symbol of danger and uncertainty, as the characters must navigate through the treacherous waters to reach their destination. Another important symbol in the novel is the snake. The snake represents temptation and danger, as it is a creature that can be both beautiful and deadly. The snake is also a symbol of transformation, as it sheds its skin and emerges anew. These symbols, along with others in the novel, add layers of meaning to the story and help to create a rich and complex narrative.

Comparing Dangerous Love to Okri’s Other Works

When comparing Dangerous Love to Ben Okri’s other works, it becomes clear that the themes of love, passion, and the human condition are recurring motifs in his writing. However, what sets Dangerous Love apart is its focus on the dangers of love and how it can lead to destruction and chaos. This is a departure from Okri’s more mystical and magical works, such as The Famished Road and Songs of Enchantment, which explore the spiritual and supernatural realms.

In Dangerous Love, Okri delves into the complexities of human relationships and the consequences of giving in to our desires. The novel is set against the backdrop of political turmoil in Nigeria, and Okri uses this as a metaphor for the tumultuous nature of love. The characters are caught up in a web of passion, jealousy, and betrayal, and their actions have far-reaching consequences.

While Dangerous Love may not be as well-known as some of Okri’s other works, it is a powerful and thought-provoking novel that deserves more attention. It showcases Okri’s ability to explore the human psyche and the darker aspects of our nature, and it is a testament to his skill as a writer. Overall, Dangerous Love is a must-read for fans of Okri’s work and anyone interested in exploring the perils of passion.

Impact of the Setting on the Story

The setting of Dangerous Love plays a crucial role in shaping the story and its characters. The novel is set in Lagos, Nigeria, during a time of political and social upheaval. The city is portrayed as chaotic, dangerous, and unpredictable, with poverty and corruption rampant. This setting creates a sense of tension and unease throughout the novel, as the characters navigate their way through a world that is constantly changing and often hostile.

The setting also reflects the themes of the novel, particularly the dangers of passion and the consequences of obsession. Lagos is a city of extremes, where love and hate, hope and despair, are all heightened. The characters are driven by their desires, whether it be for power, money, or love, and the setting amplifies the intensity of these emotions.

Furthermore, the setting of Lagos is integral to the character development of the protagonist, Omovo. As a young artist, Omovo is drawn to the vibrant and chaotic city, but as he becomes more involved in the dangerous world of politics and corruption, he begins to see the darker side of Lagos. The city becomes a symbol of his own inner turmoil, as he struggles to reconcile his passion for art with his growing disillusionment with the world around him.

Overall, the setting of Dangerous Love is a powerful and evocative element of the novel, shaping the story and its characters in profound ways. It is a testament to Ben Okri’s skill as a writer that he is able to create such a vivid and compelling portrait of Lagos, and use it to explore complex themes of love, obsession, and the human condition.

The Use of Magical Realism in Dangerous Love

In Dangerous Love, Ben Okri employs the literary technique of magical realism to explore the complexities of love and its perils. Magical realism is a genre that blends the real and the fantastical, creating a world where the supernatural and the ordinary coexist. Okri uses this technique to create a dreamlike atmosphere that blurs the lines between reality and imagination. The novel is set in a fictional African city, where the characters are confronted with a series of surreal events that challenge their beliefs and perceptions. The use of magical realism allows Okri to delve into the psychological and emotional aspects of love, portraying it as a force that can both heal and destroy. The novel’s protagonist, Omovo, is a young artist who falls in love with an enigmatic woman named Ifeyiwa. Their relationship is fraught with danger and uncertainty, as they navigate the complexities of their feelings and the social and political turmoil of their city. Through the use of magical realism, Okri creates a world that is both familiar and strange, where the boundaries between love and madness are blurred. The novel’s ending is both tragic and hopeful, as Omovo comes to terms with the consequences of his actions and the power of love to transform and transcend. Overall, Dangerous Love is a powerful exploration of the human heart and its capacity for both beauty and destruction.

Exploring the Themes of Betrayal and Revenge

Betrayal and revenge are two themes that are intricately woven into the fabric of Dangerous Love by Ben Okri. The novel explores the consequences of betrayal and the lengths to which individuals will go to exact revenge. The characters in the novel are driven by their passions, which ultimately lead them down a path of destruction. The theme of betrayal is evident in the relationships between the characters, particularly in the love triangle between the protagonist, Omovo, his lover, Ifeyiwa, and her husband, Osifo. The betrayal of trust and loyalty leads to a series of events that ultimately result in tragedy. The theme of revenge is also prevalent in the novel, as the characters seek to avenge the wrongs that have been done to them. The desire for revenge consumes the characters, leading them to commit acts of violence and destruction. The novel serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of passion and the destructive consequences of betrayal and revenge.

The Significance of Dreams in the Novel

In Dangerous Love, dreams play a significant role in the development of the story and the characters. The dreams are not just random occurrences, but rather they serve as a means of foreshadowing events and revealing the inner thoughts and emotions of the characters. The dreams are often surreal and symbolic, adding to the overall mystical and magical tone of the novel. Okri uses dreams to explore the themes of love, passion, and the dangers that come with them. The dreams also serve as a reminder that reality is not always what it seems and that there is a deeper, more profound meaning to life. Overall, the significance of dreams in Dangerous Love cannot be overstated, as they add depth and complexity to the story and the characters, making it a truly unforgettable read.

Analysis of the Ending

The ending of Dangerous Love by Ben Okri is both satisfying and thought-provoking. The main character, Omovo, finally realizes the destructive nature of his obsession with Ifeyiwa and decides to let her go. This decision is a significant turning point for Omovo, as he has spent the entire novel consumed by his desire for Ifeyiwa.

However, the ending also leaves the reader with questions about the future of Omovo and Ifeyiwa’s relationship. Will Omovo be able to move on from his obsession and find happiness? Will Ifeyiwa ever forgive him for his past behavior? These questions are left unanswered, leaving the reader to ponder the complexities of love and the consequences of obsession.

Overall, the ending of Dangerous Love is a fitting conclusion to a novel that explores the perils of passion. It highlights the importance of self-reflection and the dangers of allowing one’s desires to consume them.

The Role of Tradition in Dangerous Love

In Ben Okri’s Dangerous Love, tradition plays a significant role in shaping the characters’ actions and beliefs. The novel is set in Nigeria during the 1970s, a time when traditional values and customs were still deeply ingrained in society. The protagonist, Omovo, is torn between his love for Ifeyiwa, a woman from a wealthy family, and his loyalty to his own cultural traditions.

Ifeyiwa’s family disapproves of their relationship because Omovo is not of the same social status as them. They believe that Ifeyiwa should marry someone from a similar background, someone who can provide for her and maintain their family’s reputation. Omovo, on the other hand, is deeply in love with Ifeyiwa and is willing to go against tradition to be with her.

Throughout the novel, Okri explores the tension between tradition and modernity, and how it affects the characters’ relationships and identities. Omovo’s struggle to reconcile his love for Ifeyiwa with his loyalty to his cultural traditions is a reflection of the larger societal conflict between tradition and progress.

In Dangerous Love, tradition is portrayed as both a source of comfort and a hindrance to personal growth. While it provides a sense of belonging and continuity, it can also be oppressive and limiting. Okri’s novel highlights the importance of questioning tradition and challenging societal norms in order to achieve personal fulfillment and happiness.

Exploring the Themes of Power and Control

In Dangerous Love, Ben Okri explores the themes of power and control through the tumultuous relationship between the two main characters, Omovo and Ifeyiwa. Omovo, a young artist, becomes infatuated with Ifeyiwa, a mysterious and alluring woman who seems to hold a power over him that he cannot resist. As their relationship progresses, Ifeyiwa’s control over Omovo becomes more apparent, and he begins to lose himself in her world of secrets and manipulation.

Through this portrayal of a toxic relationship, Okri highlights the dangers of allowing someone else to have power and control over one’s life. He shows how easily one can become trapped in a cycle of abuse and manipulation, unable to break free from the hold that another person has over them.

Furthermore, Okri also explores the idea of power dynamics within society, particularly in relation to gender. Ifeyiwa’s power over Omovo is rooted in her femininity and sexuality, which she uses to manipulate and control him. This highlights the ways in which women are often objectified and reduced to their physical attributes, and how this can be used as a tool for power and control.

Overall, Dangerous Love is a powerful exploration of the themes of power and control, and the perils of allowing oneself to become trapped in a toxic relationship. Okri’s vivid and evocative writing brings these themes to life, and serves as a cautionary tale for anyone who may find themselves in a similar situation.

Comparing Dangerous Love to Other Works of African Literature

When comparing Dangerous Love to other works of African literature, it is clear that Ben Okri’s novel stands out for its unique blend of magical realism and social commentary. While many African writers have explored themes of love, betrayal, and political upheaval, few have done so with the same level of poetic language and surreal imagery as Okri.

One work that comes to mind when considering Dangerous Love is Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. Both novels deal with the clash between traditional African culture and the forces of colonialism, and both feature complex characters struggling to navigate their changing world. However, while Achebe’s novel is more straightforward in its narrative style, Okri’s prose is more dreamlike and symbolic, blurring the lines between reality and fantasy.

Another work that shares some similarities with Dangerous Love is Tsitsi Dangarembga’s Nervous Conditions. Like Okri’s novel, Dangarembga’s book explores the challenges faced by young people growing up in a rapidly changing society. However, while Nervous Conditions is primarily focused on issues of gender and education, Dangerous Love is more concerned with the nature of love itself, and the ways in which it can both inspire and destroy us.

Overall, while Dangerous Love may share some thematic similarities with other works of African literature, its unique style and perspective make it a standout novel in its own right. Okri’s poetic language and vivid imagery make for a captivating read, while his exploration of the dangers of passion and obsession is both thought-provoking and emotionally resonant.

Okri’s Views on Love and Relationships

In Dangerous Love, Ben Okri explores the complexities of love and relationships in a society that is plagued by political and social unrest. Okri’s views on love and relationships are deeply rooted in the African culture, where love is seen as a force that can bring people together or tear them apart. According to Okri, love is not just a feeling but a way of life that requires sacrifice, commitment, and understanding. He believes that love is a powerful force that can transform individuals and society as a whole. However, Okri also acknowledges the dangers of love, especially when it is driven by passion and desire. In his book, he portrays the perils of love through the experiences of his characters, who are often caught in a web of love and betrayal. Okri’s views on love and relationships are both insightful and thought-provoking, and they offer a unique perspective on the complexities of human emotions.

The Significance of the Title

The title of a book can often provide insight into the themes and messages that the author is trying to convey. In the case of Ben Okri’s Dangerous Love, the title is particularly significant as it encapsulates the central theme of the novel. The story explores the dangers that can arise when passion is allowed to run unchecked, and how this can lead to destructive and even deadly consequences. The title also hints at the idea that love itself can be a perilous emotion, capable of causing both great joy and great pain. Overall, the title of Dangerous Love serves as a warning to readers about the potential dangers of giving in to our most intense emotions, and the importance of exercising caution and restraint in matters of the heart.

Okri’s Use of Language and Imagery

Ben Okri’s Dangerous Love is a novel that is rich in language and imagery. The author’s use of language is poetic and evocative, and his descriptions of the characters and their surroundings are vivid and detailed. Okri’s writing style is characterized by a lyrical quality that draws the reader in and immerses them in the world of the novel.

One of the most striking aspects of Okri’s use of language is his ability to create powerful images that stay with the reader long after they have finished reading. For example, in one scene, the protagonist, Omovo, is described as being “like a bird with a broken wing, fluttering helplessly in the wind.” This image is both poignant and haunting, and it captures the sense of vulnerability and desperation that Omovo feels throughout the novel.

Another example of Okri’s use of imagery can be seen in his descriptions of the city of Lagos, where the novel is set. Okri paints a vivid picture of the city, with its bustling streets, crowded markets, and towering skyscrapers. He also captures the darker side of the city, with its poverty, crime, and corruption. Through his descriptions, Okri creates a sense of place that is both vivid and complex, and he invites the reader to explore the city alongside his characters.

Overall, Okri’s use of language and imagery is one of the strengths of Dangerous Love. His writing is both beautiful and powerful, and it adds depth and richness to the novel. Whether he is describing the characters, the setting, or the emotions that drive the story, Okri’s language is always evocative and engaging.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Addicted to love: What is love addiction and when should it be treated?

Brian d earp, olga a wudarczyk, bennett foddy, julian savulescu.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Recent research suggests that romantic love can be literally addictive. Although the exact nature of the relationship between love and addiction has been described in inconsistent terms throughout the literature, we offer a framework that distinguishes between a narrow view and a broad view of love addiction. The narrow view counts only the most extreme, harmful forms of love or love-related behaviors as being potentially addictive in nature. The broad view, by contrast, counts even basic social attachment as being on a spectrum of addictive motivations, underwritten by similar neurochemical processes as more conventional addictions. We argue that on either understanding of love-as-addiction, treatment decisions should hinge on considerations of harm and well-being rather than on definitions of disease. Implications for the ethical use of anti-love biotechnology are considered.

Keywords: love, sex, addiction, oxytocin, psychiatry, well-being

“By nature we are all addicted to love … meaning we want it, seek it and have a hard time not thinking about it. We need attachment to survive and we instinctively seek connection, especially romantic connection. [But] there is nothing dysfunctional about wanting love.” – Smith, quoted in Berry (2013)

Introduction

Throughout the ages love has been rendered as an excruciating passion. Ovid was the first to proclaim: “I can’t live with or without you” ( Amores III, xi, 39)—a locution made famous to modern ears by the Irish band U2. Contemporary film expresses a similar sentiment: as Jake Gyllenhaal’s character famously says in Brokeback Mountain , “I wish I knew how to quit you.” And everyday speech, too, is rife with such expressions as “I need you” and “I’m addicted to you.” These widely-used phrases capture what many people know first-hand: that when we are in love, we feel an overwhelmingly strong attraction to another person—one that is persistent, urgent, and hard to ignore.

Love can be thrilling, but it can also be perilous. When our feelings are returned, we might feel euphoric. Other times, love’s pull is so strong that we might follow it even to the point of hardship or personal ruin ( Earp, Wudarczyk, Sandberg, and Savulescu 2013 ). Lovers can become distracted, unreliable, unreasonable, or even unfaithful. In the worst case, they can become deadly. In 2011, over 10% of murders in the United States were committed by the victim’s lover ( FBI 2011 ). When relationships come to an unwanted end, we feel pain, grief, and loss. We may even become depressed, or withdrawn from society ( Mearns 1991 ).

These phenomena—including cycles of alternating ecstasy and despair, desperate longing, and the extreme and sometimes damaging thoughts and behaviors that can follow from love’s loss—bear a resemblance to analogous phenomena associated with more “conventional” addictions like those for drugs, alcohol, or gambling. Nevertheless, although we do sometimes use the language of addiction when referring to love, there is at least one major feature that distinguishes love from the kinds of substance-based addictions typically described in the psychological and medical literature: nearly everyone aspires to fall in love at least once in their life. By contrast, nobody yearns to become addicted to heroin (for example), or cigarettes, or slot machines. So it might seem absurd on its face to suggest that there could be a real similarity between lovers and “genuine” addicts. Surely it is all just hyperbole and poetic license?

Addicted to love

Perhaps not. So numerous are the superficial similarities between addictive substance use and love- and sex-based interpersonal attachments, from exhilaration, ecstasy, and craving, to irregular physiological responses and obsessive patterns of thought, that a number of scientific theorists have begun to argue that both sorts of phenomena may rely upon similar or even identical psychological, chemical, and neuroanatomical substrates (e.g., Insel 2003 ; Fisher, Brown, Aron, Strong, and Mashek 2010 ; Burkett and Young 2012 ). 1

The past decade has seen a dramatic increase in published studies on the neurobiology and neurochemistry of romantic love (for overviews, see Savulescu and Sandberg 2008 ; Earp, Sandberg, and Savulescu 2012 ). Taken together, these studies suggest that the subjective state (or states) of “being in love” is intimately tied to characteristic biochemical reactions occurring within the brain. These reactions involve such compounds as dopamine, oxytocin, vasopressin, and serotonin and recruit brain regions known to play a role in the development of trust, the creation of feelings of pleasure, and the signalling of reward ( Esch and Stefano 2005 ). The involvement of similar neurochemicals and neural activities in processes associated with addiction has already been well established ( Blum, Chen, et al. 2012 ). Consequently, scientists have begun to draw a number of parallels between the naturally rewarding phenomena associated with human love and the artificial stimulation afforded by the use of addictive substances such as alcohol, heroin, or cocaine (see Frascella et al. 2010 ).

While the specific nature of these parallels has been described in inconsistent language throughout the literature, two main approaches to conceptualizing the relationship between love and addiction can be usefully teased out. The first approach counts only the most extreme cases (or phases) of love and love-related behaviors as being potential instances of addiction. Research in this vein focuses on sexual compulsions, paedophilia, toxic or abusive relationships, abnormal attachments and unhealthy tolerance of negative life- and relationship outcomes (e.g., Carnes 2005 ; Reynaud et al. 2010 ).

The second approach takes a wider view, and counts even “normal” romantic passions as being chemically and behaviorally analogous to addiction (e.g., Fisher et al. 2010 ; Burkett and Young, 2012 ). Studies in this vein emphasize the commonality between the experience of someone under the influence of certain drugs and the quite ordinary experience of someone in love—including her “focused attention” on a preferred individual, “mood swings, craving, obsession, compulsion, distortion of reality, emotional dependence, personality changes, risk-taking, and loss of self-control” ( Fisher et al. 2010 , 51). Burkett and Young ( 2012 , 1) go so far as to defend the hypothesis that basic social attachment – covering the whole course of love-based relationships from initiation to break-up – may be understood as a form of behavioral addiction “whereby the subject becomes addicted to another individual and the cues that predict social reward.”

In the following sections, we highlight some of the latest thinking on the nature of romantic love considered as an addiction, drawing on behavioral, neurophysiological, and neuroimaging studies of both love and addiction. By doing so, we hope to give a taste of, as well as to clarify, the existing evidence in favor of these differing accounts. Following that, we will attempt to explore some of the moral and practical implications that begin to emerge once we recognize that:

one can indeed become addicted to love, and

to be in love is in some sense to be addicted—i.e, to another person

Our main thesis will be that on either understanding of love-as-addiction, there is a reasonable case to be made that, in some instances, “treatment” of love could be justified or even desirable. We will also argue that respecting the lovers’ autonomy should be paramount in any treatment decision. Along the way, we will entertain some possible objections to our views, as well as offer our replies.

The narrow view: addiction as the result of abnormal brain processes

Although scholarly attitudes have been shifting in recent years, the dominant model of addictive drug use—among neuroscientists and psychiatrists, at least—is that drugs are addictive because they gradually elicit abnormal, unnatural patterns of function in the human brain ( Foddy and Savulescu 2010 ). On this ‘narrow’ view of addiction, addictive behaviors are produced by brain processes that simply do not exist in the brains of non-addicted persons. 2

One especially popular version of this view holds that drugs ‘co-opt’ neurotransmitters in the brain to create signals of reward that dwarf the strength of ‘natural rewards’ such as food or sex. They thereby produce patterns of learning and cellular adaptation in the brain that could never be produced without drugs (e.g. Volkow et al. 2010 ). According to this strict account, then, addictive drug-seeking is an aberrant form of behavior that is peculiar to drug addicts, both in form and in underlying function. It follows that natural rewards like food and love can never be truly addictive, and that food-seeking or love-seeking behaviors are not truly the result of addiction, no matter how addiction-like they may outwardly appear.

Other researchers, however, have noted appreciable behavioral similarities between binge-eaters (for example) and drug users, and have flagged a growing body of evidence that is suggestive of neurological similarities as well ( Foddy 2011 ). Sweet food, to take just one example, can elicit a reward signal in the brain as strong as the reward from a typical dose of cocaine ( Lenoir et al. 2007 ). In addition, it can even induce—at least in rats—a withdrawal syndrome as strong as that induced by heroin ( Avena et al. 2007 ). If an illicit drug like cocaine, therefore, can produce ‘abnormal’ brain processes by providing abnormal and chronic reward, then so might an abnormally high natural reward, like the reward one gets from bingeing on food, or from experiencing unusually strong or frequent feelings of love. Given these considerations, a more plausible ‘narrow’ view of love addiction would hold that one can indeed be addicted to love, but only if these abnormal brain processes are present.

Indeed, a number of addiction theorists have argued that otherwise harmless love-related phenomena can qualify as addictive if they take on such an ‘extreme’ or maladaptive form—termed “destructive” love by Fisher (2004) , and “unwise” or “desperate” love by Peele and Brodsky (1975) . One way to begin to understand love-related behaviors of this “destructive” type is to use the framework of process addiction ( Sussman 2010 ; Timmereck 1990). Process addiction—as opposed to substance addiction—typically refers to an obsession with certain activities such as sex, spending money, eating, or gambling. When a person in love repeatedly seeks contact with another individual—for physical intimacy, attention, or merely to be in the same room—it is often to secure momentary feelings of intense pleasure and to relieve obsessive thought patterns about the object of her passion. If this sort of behavior threatens the individual’s (or another’s) safety, mental or physical health, or incurs serious social or legal costs, it may rise to the level of an addiction (e.g., Sussman 2010 ).

A further distinction has been drawn by Sussman (2010) , following Curtis (1983) , between mature love and immature love. Sussman suggests that only the latter may be considered a form of addiction. Rather than permitting mutual growth within the partnership, or contributing to increased self-esteem and well-being in both individuals, immature love is typified by power games, possessive thoughts and behaviors, obsessive concern over the partner’s fidelity, “clinging” tendencies, uncertainty, and anxiety. Love-addicts on this model “feel desperate and alone when not in a relationship,” “continue trying to romance the love object long after the relationship has broken up,” and “replace ended relationships immediately” despite such declarations as “I’ll never love again” ( Sussman 2010 , 34).

To summarize, a lover might be suffering from a type of addiction (on this narrow view) if she expresses one of a number of abnormal sexual or attachment behaviors—perhaps underwritten by similarly abnormal brain processes—such that her quest for love (1) interferes with her ability to participate in the ordinary functions of everyday life, (2) disables her from experiencing healthy relationships, or (3) carries other clear negative consequences for herself or others. In the case of more ordinary examples of love—i.e., the ones to which most people probably aspire—these feelings, behaviors, and ill consequences are not present, or are present only to a mild or manageable degree.

The narrow view of love addiction is narrow , then, in the sense that it sees only extreme, radical brain processes, attachment behaviors, or manifestations of love as being potentially indicative of addiction—and hence it is thought to be quite rare. For example, Timmereck (1990) has estimated that love addiction of this type may affect between 5-10% of the U.S population. By contrast, “healthy” romantic love, which is assumed to be much more common, is described by scholars such as Sussman (2010) as being benign or even beneficial. Such love is said to have evolved, for example, for adaptive (and still-useful) ends, such as the promotion of procreative behaviors and the facilitation of cognitive and social learning. Reynaud et al. ( 2010 , 262) distinguish between love addiction and mere “love passion” which they describe as “a universal and necessary state for human beings.” And Peele and Brodsky (1975) refer to “genuine” love, which, unlike the self-seeking dependency associated with addictive love, involves a commitment to mutual growth and fulfillment between the partners involved.

As we explore in the following section, however, other researchers, notably Burkett and Young (2012) , have begun to highlight the similarities between addiction and even “normal” romantic relationships by emphasizing the common behavioral, neurophysiological, and neurochemical signatures of both.

The broad view: love as addiction