- Share full article

Elon Musk Wants to Save Humanity. The Only Problem: People.

Walter Isaacson’s biography of the billionaire entrepreneur depicts a mercurial “man-child” with grandiose ambitions and an ego to match.

Credit... Illustration by Jan Robert Dünnweller; Photo reference by Steven Ferdman/Getty Images

Supported by

By Jennifer Szalai

- Published Sept. 9, 2023 Updated Sept. 11, 2023

- Apple Books

- Barnes and Noble

- Books-A-Million

- Bookshop.org

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

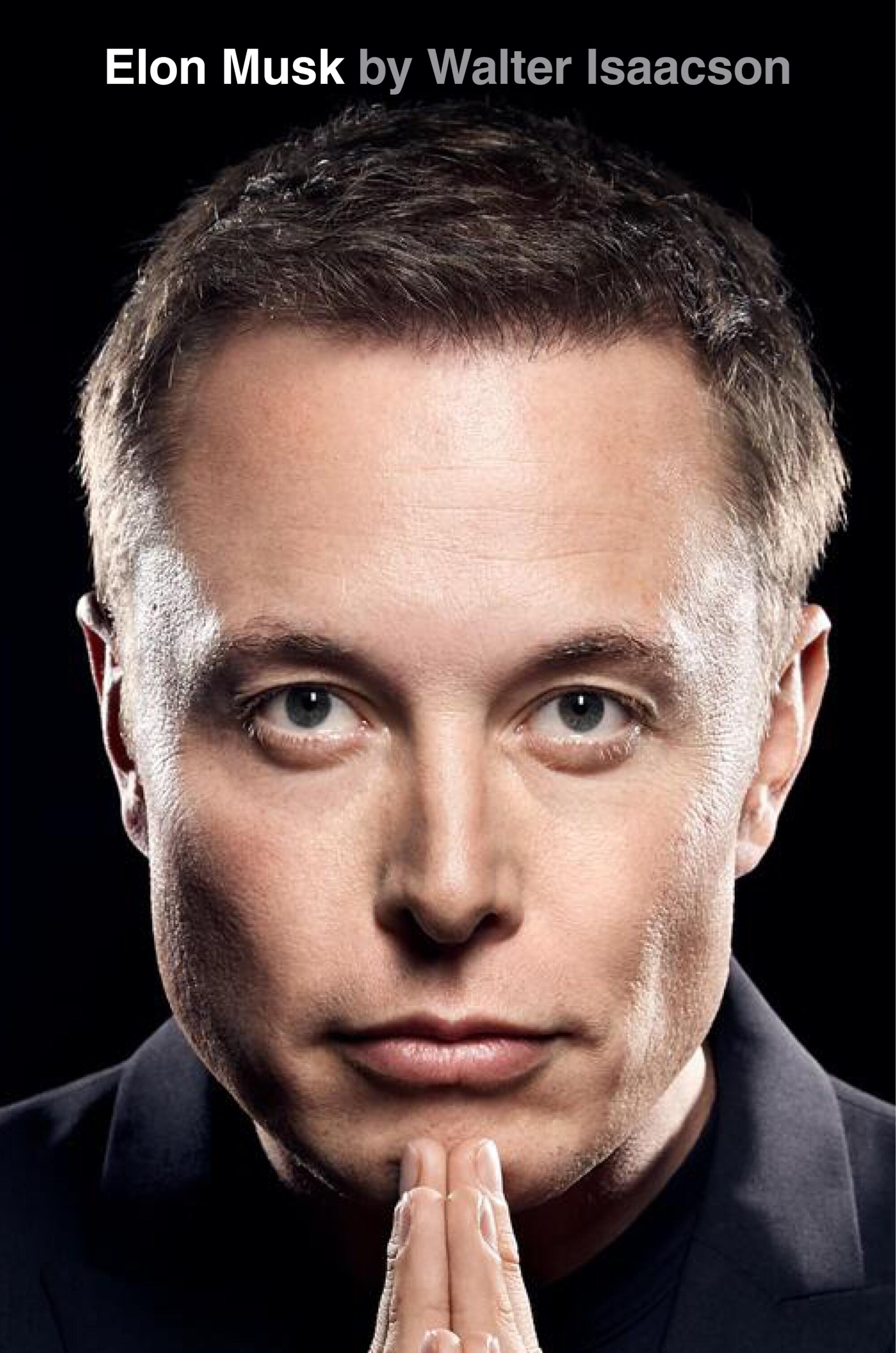

ELON MUSK , by Walter Isaacson

At various moments in “Elon Musk,” Walter Isaacson’s new biography of the world’s richest person , the author tries to make sense of the billionaire entrepreneur he has shadowed for two years — sitting in on meetings, getting a peek at emails and texts, engaging in “scores of interviews and late-night conversations.” Musk is a mercurial “man-child,” Isaacson writes, who was bullied relentlessly as a kid in South Africa until he grew big enough to beat up his bullies. Musk talks about having Asperger’s, which makes him “bad at picking up social cues.” As the people closest to him will attest, he lacks empathy — something that Isaacson describes as a “gene” that’s “hard-wired.”

Yet even as Musk struggles to relate to the actual humans around him, his plans for humanity are grand. “A fully reusable rocket is the difference between being a single-planet civilization and being a multiplanet one”: Musk would “maniacally” repeat this message to his staff at SpaceX, his spacecraft and satellite company, where every decision is motivated by his determination to get earthlings to Mars. He pushes employees at his companies — he now runs six, including X, the platform formerly known as Twitter — to slash costs and meet brutal deadlines because he needs to pour resources into the moonshot of colonizing space “before civilization crumbles.” Disaster could come from climate change, from declining birthrates, from artificial intelligence. Isaacson describes Musk stalking the factory floor of Tesla, his electric car company, issuing orders on the fly. “If I don’t make decisions,” Musk explained, “we die.”

By “we,” Musk presumably meant Tesla in that instance. But Musk likes to speak of his business interests in superhero terms, so it’s sometimes hard to be sure. Isaacson, whose previous biographical subjects include Leonardo da Vinci and Steve Jobs, is a patient chronicler of obsession; in the case of Musk, he can occasionally seem too patient — a hazard for any biographer who is given extraordinary access. At one point, Isaacson asks why Musk is so offended by anything he deems politically correct, and Musk, as usual, has to dial it up to 11. “Unless the woke-mind virus, which is fundamentally anti-science, anti-merit and anti-human in general, is stopped,” he declares, “civilization will never become multiplanetary.” There are a number of curious assertions in that sentence, but it would have been nice if Isaacson had pushed him to answer a basic question: What on earth does any of it even mean?

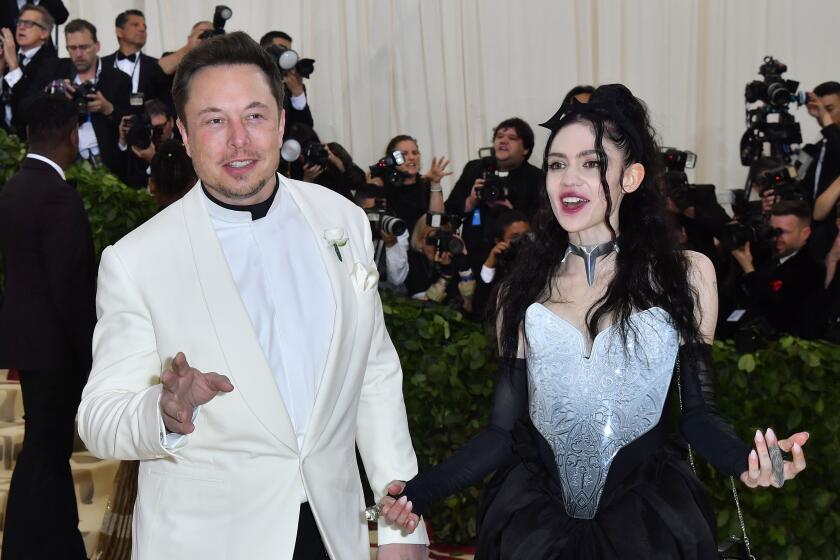

Isaacson has ably conveyed that Musk doesn’t truly like pushback. Some of his lieutenants insist that he will eventually listen to reason, but Isaacson sees firsthand Musk’s habit of deriding as a saboteur or an idiot anyone who resists him. The musician Grimes, the mother of three of Musk’s children (the existence of the third, Techno Mechanicus, nicknamed Tau, has been kept private until now), calls his roiling anger “demon mode” — a mind-set that “causes a lot of chaos.” She also insists that it allows him to get stuff done.

It’s a convenient assessment, one that Isaacson seems mostly to accept. “As Shakespeare teaches us,” he writes, “all heroes have flaws, some tragic, some conquered, and those we cast as villains can be complex.” Well, yes — but couldn’t this describe anyone? What is there to say specifically about Musk himself?

For that we can turn to Isaacson’s reporting, of which there is plenty. (Another thoroughly reported biography, by Ashlee Vance , was published in 2015 — four years before SpaceX started launching Starlink satellites and seven years before Musk acquired Twitter.) Isaacson even managed to get Errol, Elon’s intermittently estranged father, to talk — though mostly what Errol offers are rambling bigoted comments (while insisting he isn’t racist) and self-aggrandizing tales (at least one of which turns out to be “provably false”).

Errol has two children with his stepdaughter. As for Elon, he has 10 children with three women, one of whom — Shivon Zilis, who bore his twins in 2021 — is an executive at one of his companies. (Another child, Musk’s first, born in 2002, died from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome when he was 10 weeks old.)

“He really wants smart people to have kids,” Zilis said of Musk, who offered to be her sperm donor so that, Isaacson adds, “the kids would be genetically his.” At the time, Grimes and Musk were expecting their second child, a girl. Musk didn’t tell Grimes that he had just had twins with one of his employees.

But the details of such domestic intrigues are, in the book and in Musk’s life, largely beside the point. He is mostly preoccupied with his businesses, where he expects his staff to abide by “the algorithm,” his workplace creed, which commands them to “question every requirement” from a department, including “the legal department” and “the safety department”; and to “delete any part or process” they can. “Comradery is dangerous,” is one of the corollaries. So is this: “The only rules are the ones dictated by the laws of physics. Everything else is a recommendation.”

Still, Musk has accrued enough power to dictate his own rules. In one of the book’s biggest scoops, Isaacson describes Musk secretly instructing his engineers to “turn off” Starlink satellite internet coverage to prevent Ukraine from launching a surprise drone attack on Russian forces in Crimea. ( Isaacson has since posted on X that contrary to what he writes in the book, Musk didn’t shut down coverage but denied a request to extend the network’s range.) Musk decided that he was saving humanity from a nuclear war. When Ukraine’s vice prime minister texted him to say that Starlink service was “a matter of life and death,” Musk instructed him to “seek peace while you have the upper hand.”

Counseling the Ukrainians to “seek peace” sounds especially rich coming from someone who is “energized,” Isaacson says, by “dire threats.” But then the overall sense you get from this biography is that for all of Musk’s talk about the world-changing magic of “the algorithm,” he ultimately does what he wants. He will order his companies to scrimp fanatically on some things while insisting that they spend lavishly on others. At Tesla, Musk’s obsession with the minutiae of automotive design inflated costs and drained the company of cash. At SpaceX, instead of spending $1,500 for the kind of latch used by NASA, an engineer figured out how to modify a $30 latch intended for a bathroom stall. When Musk acquired Twitter last year, he eliminated 75 percent of the staff.

Since Musk’s acquisition, hate speech on the platform has proliferated while ad sales have plunged . Reading this book, one begins to wonder if the old bird-site will be Musk’s Waterloo. “He thought of it as a technology company,” Isaacson writes, “when in fact it was an advertising medium based on human emotions and relationships.” Isaacson believes that Musk wanted to buy Twitter because he had been so bullied as a kid and “now he could own the playground.” It’s an awkward metaphor, but that’s also what makes it perfect. Owning a playground won’t stop you from getting bullied. If you think about it, owning a playground won’t get you much of anything at all.

ELON MUSK | By Walter Isaacson | Illustrated | 670 pp. | Simon & Schuster | $35

Jennifer Szalai is the nonfiction book critic for The Times. More about Jennifer Szalai

The World of Elon Musk

The billionaire’s portfolio includes the world’s most valuable automaker, an innovative rocket company and plenty of drama..

Musk’s Tesla Pay: A Delaware judge affirmed an earlier ruling that rescinded a $50 billion pay package that Tesla had awarded its chief executive, Elon Musk. The pay is now worth $100 billion after Tesla’s share price jumped in recent weeks.

Musk and China: From electric cars to solar panels, Musk has built businesses in high-tech manufacturing sectors now targeted by Beijing for Chinese dominance .

A New Power Dynamic With Bezos: Musk and Jeff Bezos, the world’s two richest men, are longtime business rivals, but now one of them has the ear of the next president of the United States .

Crash Course in Trumpworld: Musk, not known for his humility, is still learning the cutthroat courtier politics of President-elect Donald Trump’s inner circle — and Musk’s ultimate influence remains an open question .

Moving to Texas: Four years ago, Musk left California for Texas, eager to embrace its wide-open business culture and be embraced by its Republican leaders. Since then, his companies have rapidly transformed parts of the state .

Advertisement

- Login / Sign Up

Believe that journalism can make a difference

If you believe in the work we do at Vox, please support us by becoming a member. Our mission has never been more urgent. But our work isn’t easy. It requires resources, dedication, and independence. And that’s where you come in.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

The big Elon Musk biography asks all the wrong questions

In Walter Isaacson’s buzzy new biography, Elon Musk emerges as a callous, chaos-loving man without empathy.

by Constance Grady

There’s a recurring phrase in Walter Isaacson’s new biography Elon Musk . Certain things, Isaacson writes again and again in his dense and thoroughly reported book, are simply “in Musk’s nature,” while others are “not in his nature.” This is a book in which Elon Musk — the richest man in history and surely one of the most infuriating, too — is driven by an immovable internal essence that no one can alter, least of all Musk himself.

Things that are in Musk’s nature according to Isaacson: the desire for total control; obsession; resistance to rules and regulations; insensitivity; a love of drama and chaos and urgency.

Things that are not in Musk’s nature according to Isaacson: deference; empathy; restraint; the ability to collaborate; the instinct to think about how the things he says impact the people around him; doting on his children; vacations.

“He didn’t have the emotional receptors that produce everyday kindness and warmth and a desire to be liked. He was not hardwired to have empathy,” Isaacson writes. “Or, to put it in less technical terms, he could be an asshole.”

The great question of Isaacson’s book is more or less the same question he posed in his 2011 biography of Steve Jobs : Is the innovation worth the assholery? Can we excuse Jobs’s cruelty to his partner Steve Wozniak because we have the iPhone? Can we excuse Musks’s many sins — his capricious firings, his callousness, his willingness to move fast and break things even when the things that get broken are human lives — because after all, he opened up the electric car market and reinvigorated the possibility for American space travel? Is it okay that Musk is an asshole if he’s also accomplishing big things?

“Would a restrained Musk accomplish as much as a Musk unbound?” Isaacson muses in the final sentences of the book. “Could you get the rockets to orbit or the transition to electric vehicles without accepting all aspects of him, hinged and unhinged? Sometimes great innovators are risk-seeking man-children who resist potty training.”

A hundred pages earlier, Isaacson depicted the man he describes as “resisting potty training” personally making the call that Ukraine should cede Crimea to Russia and on those grounds declining to extend satellite services to the Ukrainian military in the disputed territory.

“Risk of WW3 becomes very high,” Musk explained in a private exchange with Ukraine’s Vice Prime Minister Mykhailo Fedorov.

“We look through the eyes of Ukrainians,” Fedorov responded, “and you from the position of a person who wants to save humanity. And not just wants, but does more than anybody else for this.”

The risk-seeking man-child has amassed the power to have world leaders fawn over his unilateral judgment.

Isaacson portrays Musk as someone who loves chaos and has no empathy

Elon Musk was born in Pretoria, South Africa, in 1971. His mother was a model who spent most of her time at work; his father was an engineer and a wheeler-dealer with a violent temper. They sent Elon to nursery school when he was 3 because he seemed intelligent.

Musk was not, however, socially gifted. Isolated and friendless, he was prone to calling his peers stupid, at which point they would beat him up. He took refuge reading his father’s encyclopedia, plus comic books and science fiction novels about single-minded heroes who saved mankind.

For Isaacson, all this is the kind of foreshadowing biographers dream of. Most foreboding is the existence of Musk’s father, Errol, who Isaacson describes as having a “Jekyll and Hyde personality” that mirrors Musk’s own.

“One minute he would be super friendly,” says Elon’s brother Kimbal of Errol, “and the next he would be screaming at you, lecturing you for hours — literally two or three hours while he forced you to just stand there — calling you worthless, pathetic, making scarring and evil comments, not allowing you to leave.”

From Errol, Isaacson intimates, Musk inherited his explosive temper and fondness for dismissing anything that displeases him as stupid. He also learned to crave crisis, to the point that decades later, as CEO of six companies, he would develop a practice of arbitrarily picking one of those companies to send into panic mode. A rule he makes his executives intone like a religious litany is to “work with a maniacal sense of urgency.”

Another one of Musk’s rules is that empathy is not an asset, largely because he himself claims not to experience it. For Isaacson, this is one of the other foundations of Musk’s character, part of that unchangeable nature that was created by the mingled forces of Musk’s traumatic childhood and his neurodivergence. The lack of empathy, he argues, is hardwired in, probably due to the condition Musk describes as Asperger’s. (Asperger’s syndrome is a form of autism spectrum disorder that is no longer an official diagnosis . Musk is self-diagnosed.)

Studies suggest that people with autism actually experience just as much affective empathy as neurotypical people , but that is not a possibility either Musk or Isaacson ever discuss. For the narrative of this book, Musk’s callousness must be something beyond his control, one of the fundamental differences that sets him apart from the kinder, smaller people who make up the rest of the human race.

Musk goes through companies as rapidly as he goes through women

After high school, Musk fled: first to Canada, where his mother was born, and next to America. Over two years at Queen’s University and two at Penn, he earned a dual degree: in physics, so he could work as an engineer with an understanding of the fundamentals, and in business, so he would never have to work for anyone but himself. Upon graduating, he turned down a spot at Stanford’s PhD program to start his first business, an early online business directory called Zip2.

At Zip2, we see the beginnings of Musk’s maniacal work ethic take hold — that, and his inability to work well with others. He and his brother Kimbal sleep on futons in their office and shower at the Y down the street. When new engineers come in, Musk devotes extra time to “fixing their stupid fucking code.” He and Kimbal get into physical knockdown fights in the office; once, Musk has to go to the hospital for a tetanus shot after Kimbal bites him. They sell the company after two years for $300 million.

Zip2 establishes the pattern that will follow Musk throughout his professional career. He works exceptionally long hours, frequently camping out in his office, and he rages at anyone who does not. He tends to dismiss all his collaborators as stupid and will get into furious fights with them (albeit mostly not physical). He will end up having alienated a lot of people, created a pretty interesting product, and made a hell of a lot of money.

From Zip2, Musk moved on to X.com, an early online banking company. Musk had grand plans of using X.com to reinvent banking writ large, but he was pushed out when X merged with PayPal to develop a product he saw, disgustedly, as niche.

Licking his wounds, Musk decided that he would focus his energies only on companies that were truly changing the world. To make humankind an interplanetary species, in 2001 he founded SpaceX, with a mission of bringing humans to Mars. To help stave off the worst of climate change, in 2003 he brought together a group of engineers working on the electric car to amp up the fledgling company that was Tesla.

As Isaacson is always noting, it was not in Musk’s nature to give up control. After briefly experimenting with having other CEOs, he took personal control of both SpaceX and Tesla. Today, he’s CEO of six companies. In addition to Tesla and SpaceX, he’s got the Boring Company (for tunnels), Neuralink (for technology that can interface between human brains and machines), X (formerly known as Twitter), and X.AI, an artificial intelligence company he founded earlier this year. Musk goes through companies fast.

He also goes through women. Isaacson chronicles the four major romantic relationships of Musk’s adult life with a shamelessly misogynistic binary. All Musk’s girlfriends in this book are either devils or angels, and accordingly they bring out either the devil or angel in Musk’s uncontrollable nature.

His college girlfriend and first wife, fantasy novelist Justine Wilson, is one of the devils: “She has no redeeming features,” insists Musk’s mother. Per Isaacson, she thrives on drama and brings out Musk’s control freak side. He pushes her to dye her hair platinum blonde and act the part of the new millionaire’s trophy wife. “I am the alpha in this relationship,” he whispers into her ear as they dance on their wedding night.

Musk’s second wife, the English actress Talulah Riley, is meanwhile an angel. She dotes on Musk’s children with Justine, tells the press she sees it as her job to keep Musk from going “king-crazy,” and throws him elaborate theatrical parties. “If he had liked stability more than storm and drama,” Isaacson writes, “she would have been perfect for him.”

It goes on like that. Actress Amber Heard, who Musk dates for a tumultuous year after divorcing Riley, is a devil who “drew him into a dark vortex.” Musician Grimes, with whom he has three children, is an angel, “chaotic good” to Heard’s “chaotic evil.” (Musk repays her chaotic goodness by secretly fathering more children with one of Neuralink’s executives, a friend of Grimes’s, at the same time that he and Grimes are working with a surrogate to have their second child.) The idea that it might be Musk’s responsibility to control his nature, rather than the responsibility of his romantic partners, appears nowhere in this book.

The book’s big problem is that it ignores systemic problems for individual

In 2018, Musk became the richest man in the world and Time’s Person of the Year. From there he spiraled. His political views veered sharply to the right wing and paranoid. His tweets got weirder. Then he outright bought Twitter and commenced polarizing an already polarized user base. He’s still making the rockets that supply the International Space Station and he’s still building the most successful electric car in the world, but his reputation has taken a palpable hit.

In Isaacson’s narrative, Musk’s social downfall is part of his Shakespearean hubris, the tragic flaw that drives him to continually inflict pain on himself: the lack of empathy coupled with the craving for excitement; the genuine intelligence matched by over-the-top arrogance. It drives him to achieve great things and to mess up badly.

For Isaacson, this binary illustrates why Musk’s acquisition of Twitter was destined for trouble. “He thought of it as a technology company” within his realm of expertise, Isaacson writes, and didn’t understand that it was “an advertising medium based on human emotions and relationships,” and thus well outside his lane. What does the man who doesn’t believe in empathy know about connecting human beings to one another? But how could the man who needs chaos to function resist the internet’s most visibly chaotic platform?

That’s a genuine insight, but by and large, Isaacson’s focus in this book is not on analysis. Elon Musk is strictly a book of reportage, based on the two years Isaacson spent shadowing Musk and the scores of interviews he did with Musk’s associates. His reporting is rigorous and dogged; you can see the sweat on the pages. If his prose occasionally clunks (Isaacson cites the “feverish fervor” of Musk’s fans and critics), that’s not really the point of this kind of book. Instead, Isaacson’s great weakness shows itself in his blind spots, in the places where he declines to train his dutiful reporter’s eye.

Isaacson spends a significant amount of page time covering one of Musk’s signature moves: ignoring the rules. Part of the “algorithm” he makes his engineers run on every project involves finding the specific person who wrote each regulation they slam up against as they build and then interrogating the person as to what the regulation is supposed to do. All regulations are believed by default to be “dumb,” and Musk does not accept “safety” as a reason for a regulation to exist.

At one point, Isaacson describes Musk becoming enraged when, working on the Tesla Model S, he finds a government-mandated warning about child airbag safety on the passenger-side visor. “Get rid of them,” he demands. “People aren’t stupid. These stickers are stupid.” Tesla faces recall notices because of the change, Isaacson reports, but Musk “didn’t back down.”

What Isaacson doesn’t mention is that Musk consistently ignores safety regulations whenever they clash with his own aesthetic sense, to consistently dangerous results.

According to a 2018 investigation from the Center for Investigative Reporting’s Reveal , Musk demanded Tesla factories minimize the auto industry standard practice of painting hazard zones yellow and indicating caution with signs and beeps and flashing lights, on the grounds he doesn’t particularly care for any of those things. As a result, Tesla factories mostly distinguish caution zones from other zones with different shades of gray.

Isaacson does report that Musk removed safety sensors from the Tesla production lines because he thought they were slowing down the work, and that his managers worried that his process was unsafe. “There was some truth to the complaints,” Isaacson allows. “Tesla’s injury rate was 30 percent higher than the rest of the industry.” He does not report that Tesla’s injury rate is in fact on par with the injury rate at slaughterhouses, or that it apparently cooked its books to cover up its high injury rate .

Isaacson is vague about exactly what kind of injuries occur in the factories Musk runs. Nowhere does he mention anything along the lines of what Reveal reports as Tesla workers “sliced by machinery, crushed by forklifts, burned in electrical explosions, and sprayed with molten metal.” He notes that Musk violated public safety orders to keep Tesla factories open after the Covid-19 lockdown had begun, but claims that “the factory experienced no serious Covid outbreak.” In fact, the factory Musk illegally opened would report 450 positive Covid cases .

No one can accuse the biographer who frankly admits that his subject is an asshole of ignoring his flaws. Yet Isaacson does regularly ignore the moments at which Musk’s flaws scale . He has no interest in the many, many times when Musk did something mavericky and counterintuitive and, because of his power and wealth and platform and reach, it ended up hurting a whole lot of people.

Instead, Isaacson seems most interested in Musk’s cruelty when it’s confined to the level of the individual. He likes the drama of Musk telling his cousin that his solar roof prototype is “total fucking shit” and then pushing him out of the company, or of Musk scrambling to fire Twitter’s executive team before they can resign so he doesn’t have to pay out their severance packages. Those are the moments of this book with real juice to them.

Ultimately, it’s this blind spot that prevents Isaacson from fully exploring the question at the core of Elon Musk : Is Elon Musk’s cruelty worth it since he’s creating technology that might change the world? Because Isaacson is only interested in Musk’s cruelty when it’s personal, in this book, that question looks like: If SpaceX ends up taking us all to Mars and saving humanity, will it matter that Musk was really mean to his cousin?

Widen the scope, and the whole thing becomes much more interesting and urgent. If Elon Musk consistently endangers the people who work for him and the people who buy his products and the people who stand in his way, does it matter if he thinks he’s saving the human race?

Isaacson compares Musk to a “man-child who resists potty-training.” If we look closely at the amount of damage he is positioned to do, how comfortable are we with the power Elon Musk currently has?

Correction, September 15, 11:30 am: A previous version of this story misstated a university Musk attended. It is Queen’s University.

Most Popular

- A big insurer backed off its plan to pay less for anesthesia. That’s bad.

- Public housing didn’t fail in the US. But it was sabotaged.

- The deep roots of Americans’ hatred of their health care system

- Your drawer full of old cables is worth more than you think Member Exclusive

- After 13 years of war, Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria has been defeated. What comes next?

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Culture

25 years later, Kyle Mooney’s new movie revisits the apocalypse that wasn’t.

Why Brian Thompson’s death has provoked such complicated reactions from the public.

The cult reality show offered a darkly comic look at the American dream. Can a reboot recreate the horror?

8 books that made the case for art in a fraught year.

For music lovers, streaming has never felt more stale.

The Hawaii resident’s disappearance became a viral internet mystery. That may have made things worse.

In 2021, Elon Musk became the world’s richest man (no woman came close), and Time named him Person of the Year: “This is the man who aspires to save our planet and get us a new one to inhabit: clown, genius, edgelord, visionary, industrialist, showman, cad; a madcap hybrid of Thomas Edison, P. T. Barnum, Andrew Carnegie and Watchmen ’s Doctor Manhattan, the brooding, blue-skinned man-god who invents electric cars and moves to Mars.” Right about when Time was preparing that giddy announcement, three women whose ovaries and uteruses were involved in passing down the madcap man-god’s genes were in the maternity ward of a hospital in Austin. Musk believes a declining birth rate is a threat to civilization and, with his trademark tirelessness, is doing his visionary edgelord best to ward off that threat. Shivon Zilis, a thirty-five-year-old venture capitalist and executive at Musk’s company Neuralink, was pregnant with twins, conceived with Musk by in-vitro fertilization, and was experiencing complications. “He really wants smart people to have kids, so he encouraged me to,” Zilis said. In a nearby room, a woman serving as a surrogate for Musk and his thirty-three-year-old ex-wife, Claire Boucher, a musician better known as Grimes, was suffering from pregnancy complications, too, and Grimes was staying with her.

“I really wanted him to have a daughter so bad,” Grimes said. At the time, Musk had had seven sons, including, with Grimes, a child named X. Grimes did not know that Zilis, a friend of hers, was down the hall, or that Zilis was pregnant by Musk. Zilis’s twins were born seven weeks premature; the surrogate delivered safely a few weeks later. In mid-December, Grimes’s new baby came home and met her brother X. An hour later, Musk took X to New York and dandled him on his knee while being photographed for Time .

“He dreams of Mars as he bestrides Earth, square-jawed and indomitable,” the magazine’s Person of the Year announcement read. Musk and Grimes called the baby, Musk’s tenth, Y, or sometimes “Why?,” or just “?”—a reference to Musk’s favorite book, Douglas Adams’s “ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy ,” because, Grimes explained, it’s a book about how knowing the question is more important than knowing the answer.

Discover notable new fiction and nonfiction.

Elon Musk is currently at or near the helm of six companies: Tesla, SpaceX (which includes Starlink), the Boring Company, Neuralink, X (formerly known as Twitter), and X.AI, an artificial-intelligence company that he founded, earlier this year, because he believes that human intelligence isn’t reproducing fast enough, while artificial intelligence is getting more artificially intelligent exponentially. Call it Musk’s Law: the answer to killer robots is more Musk babies. Plus, more Musk companies. “I can’t just sit around and do nothing,” Musk says, fretting about A.I., in Walter Isaacson’s new biography, “ Elon Musk ” (Simon & Schuster), a book that can scarcely contain its subject, in that it raises infinitely more questions than it answers.

“Are you sincerely trying to save the world?” Stephen Colbert once asked Musk on “The Late Show.” “Well, I’m trying to do good things, yeah, saving the world is not, I mean . . . ,” Musk said, mumbling. “But you’re trying to do good things, and you’re a billionaire,” Colbert interrupted. “Yeah,” Musk said, nodding. Colbert said, “That seems a little like superhero or supervillain. You have to choose one.” Musk paused, his face blank. That was eight years, several companies, and as many children ago. Things have got a lot weirder since. More Lex Luthor, less Tony Stark.

Musk controls the very tiniest things, and the very biggest. He oversees companies, valued at more than a trillion dollars, whose engineers have built or are building, among other things, reusable rocket ships, a humanoid robot, hyperloops for rapid transit, and a man-machine interface to be implanted in human brains. He is an entrepreneur, a media mogul, a political provocateur, and, not least, a defense contractor: SpaceX has received not only billions of dollars in government contracts for space missions but also more than a hundred million dollars in military contracts for missile-tracking satellites, and Starlink’s network of four thousand satellites— which provides Pentagon-funded services to Ukraine —now offers a military service called Starshield. Day by day, Musk’s companies control more of the Internet, the power grid, the transportation system, objects in orbit, the nation’s security infrastructure, and its energy supply.

And yet. At a jury trial earlier this year, Musk’s lawyer repeatedly referred to his client, a middle-aged man, as a “kid.” The Wall Street Journal has described him as suffering from “tantrums.” The Independent has alleged that selling Twitter to Musk was “like handing a toddler a loaded gun.”

“I’m not evil,” Musk said on “Saturday Night Live” a couple of years ago, playing the dastardly Nintendo villain Wario, on trial for murdering Mario. “I’m just misunderstood.” How does a biographer begin to write about such a man? Some years back, after Isaacson had published a biography of Benjamin Franklin and was known to be writing one of Albert Einstein, the Apple co-founder Steve Jobs called him up and asked him to write his biography; Isaacson says he wondered, half jokingly, whether Jobs “saw himself as the natural successor in that sequence.” I don’t think Musk sees himself as a natural successor to anyone. As I read it, Isaacson found much to like and admire in Jobs but is decidedly uncomfortable with Musk. (He calls him, at one point, “an asshole.”) Still, Isaacson’s descriptions of Jobs and Musk are often interchangeable. “His passions, perfectionism, demons, desires, artistry, devilry, and obsession for control were integrally connected to his approach to business and the products that resulted.” (That’s Jobs.) “It was in his nature to want total control.” (Musk.) “He didn’t have the emotional receptors that produce everyday kindness and warmth and a desire to be liked.” (Musk.) “He was not a model boss or human being.” (Jobs.) “This is a book about the roller-coaster life and searingly intense personality of a creative entrepreneur whose passion for perfection and ferocious drive revolutionized six industries.” I ask you: Which?

“Sometimes great innovators are risk-seeking man-children who resist potty training,” Isaacson concludes in the last lines of his life of Musk. “They can be reckless, cringeworthy, sometimes even toxic. They can also be crazy. Crazy enough to think they can change the world.” It’s a disconcerting thing to read on page 615 of a biography of a fifty-two-year-old man about whom a case could be made that he wields more power than any other person on the planet who isn’t in charge of a nuclear arsenal. Not potty-trained? Boys will be . . . toddlers?

Elon Musk was born in Pretoria, South Africa, in 1971. His grandfather J. N. Haldeman was a staunch anti-Communist from Canada who in the nineteen-thirties and forties had been a leader of the anti-democratic and quasi-fascist Technocracy movement. (Technocrats believed that scientists and engineers should rule.) “In 1950, he decided to move to South Africa,” Isaacson writes, “which was still ruled by a white apartheid regime.” In fact, apartheid had been declared only in 1948, and the regime was soon recruiting white settlers from North America, promising restless men such as Haldeman that they could live like princes. Isaacson calls Haldeman’s politics “quirky.” In 1960, Haldeman self-published a tract, “The International Conspiracy to Establish a World Dictatorship & the Menace to South Africa,” that blamed the two World Wars on the machinations of Jewish financiers.

Musk’s mother, Maye Haldeman, was a finalist for Miss South Africa during her tumultuous courtship with his father, Errol Musk, an engineer and an aviator. In 2019, she published a memoir titled “A Woman Makes a Plan: Advice for a Lifetime of Adventure, Beauty, and Success.” For all that she writes about growing up in South Africa in the nineteen-fifties and sixties, she never once mentions apartheid.

Isaacson, in his account of Elon Musk’s childhood, barely mentions apartheid himself. He writes at length and with compassion about the indignities heaped upon young Elon by schoolmates. Elon, an awkward, lonely boy, was bored in school and had a tendency to call other kids “stupid”; he was also very often beaten up, and his father frequently berated him, but when he was ten, a few years after his parents divorced, he chose to live with him. (Musk is now estranged from his father, a conspiracist who has called Joe Biden a “pedophile President,” and who has two children by his own stepdaughter; he has said that “the only thing we are here for is to reproduce.” Recently, he warned Elon, in an e-mail, that “with no Whites here, the Blacks will go back to the trees.”)

Link copied

Musk’s childhood sounds bad, but Isaacson’s telling leaves out rather a lot about the world in which Musk grew up. In the South Africa of “Elon Musk,” there are Musks and Haldemans—Elon and his younger brother and sister and his many cousins—and there are animals, including the elephants and monkeys who prove to be a nuisance at a construction project of Errol’s. There are no other people, and there are certainly no Black people, the nannies, cooks, gardeners, cleaners, and construction workers who built, for white South Africans, a fantasy world. And so, for instance, we don’t learn that in 1976, when Elon was four, some twenty thousand Black schoolchildren in Soweto staged a protest and heavily armed police killed as many as seven hundred. Instead, we’re told, “As a kid growing up in South Africa, Elon Musk knew pain and learned how to survive it.”

Musk, the boy, loved video games and computers and Dungeons & Dragons and “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,” and he still does. “I took from the book that we need to extend the scope of consciousness so that we are better able to ask the questions about the answer, which is the universe,” Musk tells Isaacson. Isaacson doesn’t raise an eyebrow, and you can wonder whether he has read “Hitchhiker’s Guide,” or listened to the BBC 4 radio play on which it is based, first broadcast in 1978. It sounds like this:

Far back in the mists of ancient time, in the great and glorious days of the former galactic empire, life was wild, rich, and, on the whole, tax free. . . . Many men of course became extremely rich, but this was perfectly natural because no one was really poor, at least, no one worth speaking of.

“The Hitchhiker’s Guide” is not a book about how “we need to extend the scope of consciousness so that we are better able to ask the questions about the answer, which is the universe.” It is, among other things, a razor-sharp satiric indictment of imperialism:

And for these extremely rich merchants life eventually became rather dull, and it seemed that none of the worlds they settled on was entirely satisfactory. Either the climate wasn’t quite right in the later part of the afternoon or the day was half an hour too long or the sea was just the wrong shade of pink. And thus were created the conditions for a staggering new form of industry: custom-made, luxury planet-building.

Douglas Adams wrote “The Hitchhiker’s Guide” on a typewriter that had on its side a sticker that read “End Apartheid.” He wasn’t crafting an instruction manual for mega-rich luxury planet builders.

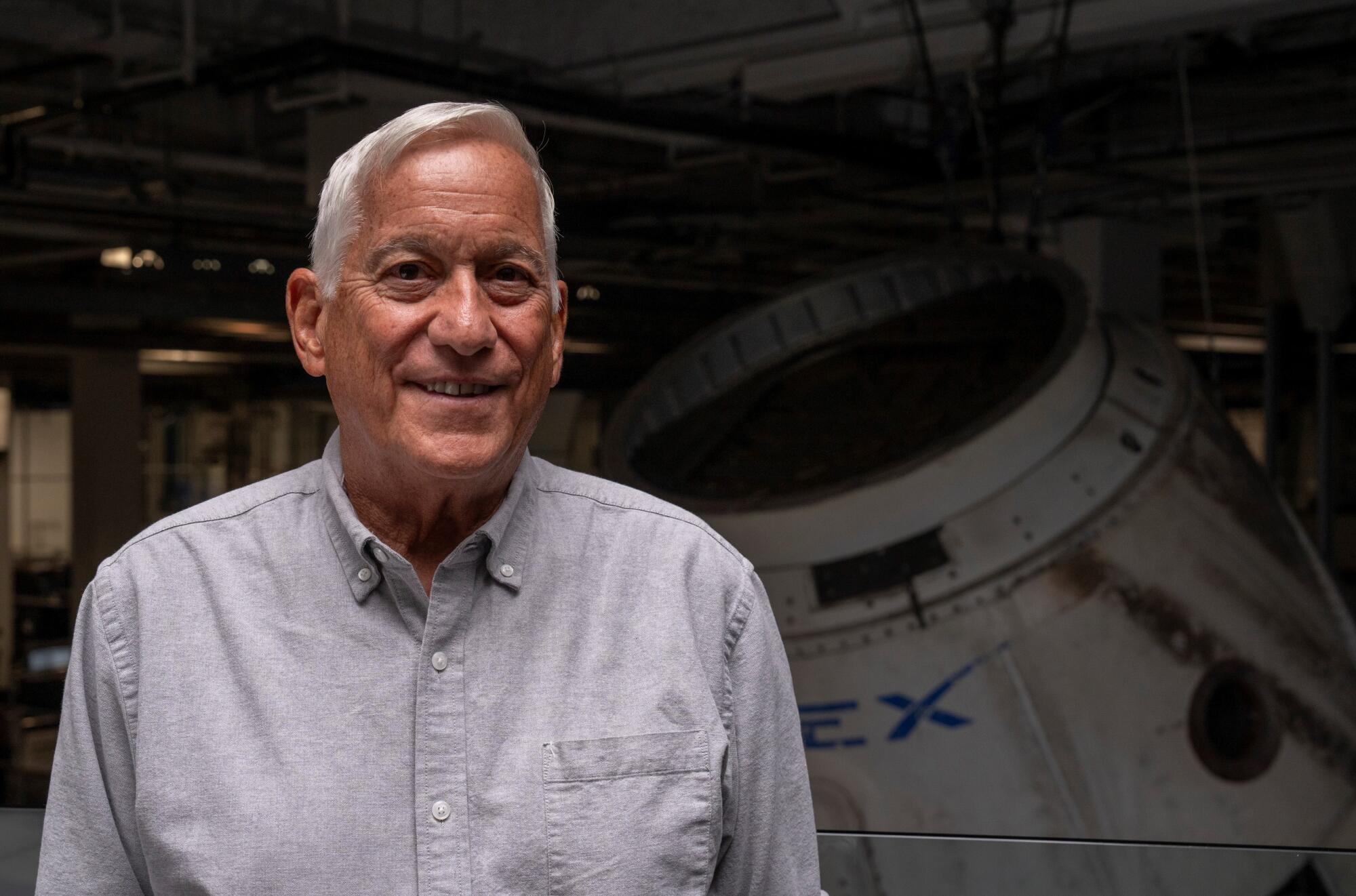

Biographers don’t generally have a will to power. Robert Caro is not Robert Moses and would seem to have very little in common with Lyndon the “B” is for “bastard” Johnson. Walter Isaacson is a gracious, generous, public-spirited man and a principled biographer. This year, he was presented with the National Humanities Medal. But, as a former editor of Time and a former C.E.O. of CNN and of the Aspen Institute, Isaacson also has an executive’s affinity for the C-suite, which would seem to make it a challenge to keep a certain distance from the world view of his subject. Isaacson shadowed Musk for two years and interviewed dozens of people, but they tend to have titles like C.E.O., C.F.O., president, V.P., and founder. The book upholds a core conviction of many executives: sometimes to get shit done you have to be a dick. He dreams of Mars as he bestrides Earth, square-jawed and indomitable . For the rest of us, Musk’s pettiness, arrogance, and swaggering viciousness are harder to take, and their necessity less clear.

Isaacson is interested in how innovation happens. In addition to biographies of Franklin, Einstein, Jobs, and Leonardo da Vinci , he has also written about figures in the digital revolution and in gene editing. Isaacson puts innovation first: This man might be a monster, but look at what he built! Whereas Mary Shelley, for instance, put innovation second: The man who built this is a monster! The political theorist Judith Shklar once wrote an essay called “ Putting Cruelty First .” Montaigne put cruelty first, identifying it as the worst thing people do; Machiavelli did not. As for “the usual excuse for our most unspeakable public acts,” the excuse “that they are necessary,” Shklar knew this to be nonsense. “Much of what passed under these names was merely princely wilfulness,” as Shklar put it. This is always the problem with princes.

Elon Musk started college at the University of Pretoria but left South Africa in 1989, at seventeen. He went first to Canada and, after two years at Queen’s University in Ontario, transferred to the University of Pennsylvania, where he studied physics and economics, and wrote a senior paper titled “The Importance of Being Solar.” He had done internships in Silicon Valley and, after graduating, enrolled in a Ph.D. program in materials science at Stanford, but he deferred admission and never went. It was 1995, the year the Internet opened to commercial traffic. All around him, frogs were turning into princes. He wanted to start a startup. Musk and his brother Kimball, with money from their parents, launched Zip2, an early online Yellow Pages that sold its services to newspaper publishers. In 1999, during the dot-com boom, they sold it to Compaq for more than three hundred million dollars. Musk, with his share of the money, launched one of the earliest online banking companies. He called it X.com. “I think X.com could absolutely be a multibillion-dollar bonanza,” he told CNN, but, meanwhile, “I’d like to be on the cover of Rolling Stone .” That would have to wait for a few years, but in 1999 Salon announced, “Elon Musk Is Poised to Become Silicon Valley’s Next Big Thing,” in a profile that advanced what was already a hackneyed set of journalistic conventions about the man-boy man-gods of Northern California: “The showiness, the chutzpah, the streak of self-promotion and the urge to create a dramatic public persona are major elements of what makes up the Silicon Valley entrepreneur. . . . Musk’s ego has gotten him in trouble before, and it may get him in trouble again, yet it is also part and parcel of what it means to be a hotshot entrepreneur.” Five months later, Musk married his college girlfriend, Justine Wilson. During their first dance at their wedding, he whispered in her ear, “I am the alpha in this relationship.”

“ Big Ego of Hotshot Entrepreneur Gets Him Into Trouble ” is more or less the running headline of Musk’s life. In 2000, Peter Thiel’s company Confinity merged with X.com, and Musk regretted that the new company was called PayPal, instead of X . (He later bought the domain x.com, and for years he kept it as a kind of shrine, a blank white page with nothing but a tiny letter “x” on the screen.) In 2002, eBay paid $1.5 billion for the company, and Musk drew on his share of the sale to start SpaceX. Two years later, he invested around $6.5 million in Tesla; he became both its largest shareholder and its chairman. Around then, in his Marvel Iron Man phase, Musk left Northern California for Los Angeles, to swan with starlets. Courted by Ted Cruz during COVID , he moved to Texas, because he dislikes regulation, and because he objected to California’s lockdowns and mask mandates.

Musk’s accomplishments as the head of a series of pioneering engineering firms are unrivalled. Isaacson takes on each of Musk’s ventures, venture by venture, chapter by chapter, emphasizing the ferocity and the velocity and the effectiveness of Musk’s management style—“A maniacal sense of urgency is our operating principles” is a workplace rule. “How the fuck can it take so long?” Musk asked an engineer working on SpaceX’s Merlin engines. “This is stupid. Cut it in half.” He pushed SpaceX through years of failures, crash after crash, with the confidence that success would come. “Until today, all electric cars sucked,” Musk said, launching Tesla’s Roadster, leaving every other electric car and most gas cars in the dust. No automotive company had broken into that industry in something like a century. Like SpaceX, Tesla went through very hard times. Musk steered it to triumph, a miracle amid fossil fuel’s stranglehold. “Fuck oil,” he said.

“Comradery is dangerous” is another of Musk’s workplace maxims. He was ousted as PayPal’s C.E.O. and ousted as Tesla’s chairman. He’s opposed to unions, pushed workers back to the Tesla plants at the height of the Covid pandemic—some four hundred and fifty reportedly got infected—and has thwarted workers’ rights at every turn.

Musk has run through companies and he has run through wives. In some families, domestic relations are just another kind of labor relations. He pushed his first wife, Justine, to dye her hair blonder. After they lost their firstborn son, Nevada, in infancy, Justine gave birth to twins (one of whom they named Xavier, in part for Professor Xavier, from “X-Men”) and then to triplets. When the couple fought, he told her, “If you were my employee, I would fire you.” He divorced her and soon proposed to Talulah Riley, a twenty-two-year-old British actress who had only just moved out of her parents’ house. She said her job was to stop Musk from going “king-crazy”: “People become king, and then they go crazy.” They married, divorced, married, and divorced. But “you’re my Mr. Rochester,” she told him. “And if Thornfield Hall burns down and you are blind, I’ll come and take care of you.” He dated Amber Heard, after her separation from Johnny Depp. Then he met Grimes. “I’m just a fool for love,” Musk tells Isaacson. “I am often a fool, but especially for love.”

He is also a fool for Twitter. His Twitter account first got him into real trouble in 2018, when he baselessly called a British diver, who helped rescue Thai children trapped in a flooded cave, a “pedo” and was sued for defamation. That same year, he tweeted, “Am considering taking Tesla private at $420,” making a pot joke. “Funding secured.” (“I kill me,” he says about his sense of humor.) The S.E.C. charged him with fraud, and Tesla stock fell more than thirteen per cent. Tesla shareholders sued him, alleging that his tweets had caused their stock to lose value. On Joe Rogan’s podcast, he went king-crazy, lighting up a joint. He looked at his phone. “You getting text messages from chicks?” Rogan asked. “I’m getting text messages from friends saying, ‘What the hell are you doing smoking weed?’ ”

“Musk’s goofy mode is the flip side of his demon mode,” Isaacson writes. Musk likes this kind of cover. “I reinvented electric cars, and I’m sending people to Mars in a rocket ship,” he said in his “S.N.L.” monologue, in 2021. “Did you think I was also going to be a chill, normal dude?” In that monologue, he also said that he has Asperger’s. A writer in Newsweek applauded this announcement as a “milestone in the history of neurodiversity.” But, in Slate, Sara Luterman, who is autistic, was less impressed; she denounced Musk’s “coming out” as “self-serving and hollow, a poor attempt at laundering his image as a heartless billionaire more concerned with cryptocurrency and rocket ships than the lives of others.” She put cruelty first.

Musk’s interest in acquiring Twitter dates to 2022. That year, he and Grimes had another child. His name is Techno Mechanicus Musk, but his parents call him Tau, for the irrational number. But Musk also lost a child. His twins with Justine turned eighteen in 2022 and one of them, who had apparently become a Marxist, told Musk, “I hate you and everything you stand for.” It was, to some degree, in an anguished attempt to heal this developing rift that, in 2020, Musk tweeted, “I am selling almost all physical possessions. Will own no house.” That didn’t work. In 2022, his disaffected child petitioned a California court for a name change, to Vivian Jenna Wilson, citing, as the reason for the petition, “Gender Identity and the fact that I no longer live with or wish to be related to my biological father in any way, shape or form.” She refuses to see him. Musk told Isaacson he puts some of the blame for this on her progressive Los Angeles high school. Lamenting the “woke-mind virus,” he decided to buy Twitter. I just can’t sit around and do nothing .

Musk’s estrangement from his daughter is sad, but of far greater consequence is his seeming estrangement from humanity itself. When Musk decided to buy Twitter, he wrote a letter to its board. “I believe free speech is a societal imperative for a functioning democracy,” he explained, but “I now realize the company will neither thrive nor serve this societal imperative in its current form.” This is flimflam. Twitter never has and never will be a vehicle for democratic expression. It is a privately held corporation that monetizes human expression and algorithmically maximizes its distribution for profit, and what turns out to be most profitable is sowing social, cultural, and political division. Its participants are a very tiny, skewed slice of humanity that has American journalism in a choke hold. Twitter does not operate on the principle of representation, which is the cornerstone of democratic governance. It has no concept of the “civil” in “civil society.” Nor has Elon Musk, at any point in his career, displayed any commitment to either democratic governance or the freedom of expression.

Musk gave Isaacson a different explanation for buying the company: “Unless the woke-mind virus, which is fundamentally antiscience, antimerit, and antihuman in general, is stopped, civilization will never become multiplanetary.” It’s as if Musk had come to believe the sorts of mission statements that the man-boy gods of Silicon Valley had long been peddling. “At first, I thought it didn’t fit into my primary large missions,” he told Isaacson, about Twitter. “But I’ve come to believe it can be part of the mission of preserving civilization, buying our society more time to become multiplanetary.”

Elon Musk plans to make the world safe for democracy, save civilization from itself, and bring the light of human consciousness to the stars in a ship he will call the Heart of Gold, for a spaceship fuelled by an Improbability Drive in “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.” In case you’ve never read it, what actually happens in “The Hitchhiker’s Guide” is that the Heart of Gold is stolen by Zaphod Beeblebrox, who is the President of the Galaxy, has two heads and three arms, is the inventor of the Pan Galactic Gargle Blaster, has been named, by “the triple-breasted whore of Eroticon 6,” the “Biggest Bang Since the Big One,” and, according to his private brain-care specialist, Gag Halfrunt, “has personality problems beyond the dreams of analysts.” Person of the Year material, for sure. All the same, as a Vogon Fleet prepares to shoot down the Heart of Gold with Beeblebrox on board, Halfrunt muses that “it will be a pity to lose him,” but, “well, Zaphod’s just this guy, you know?” ♦

New Yorker Favorites

A man was murdered in cold blood and you’re laughing ?

The best albums of 2024.

Little treats galore: a holiday gift guide .

How Maria Callas lost her voice .

An objectively objectionable grammatical pet peeve .

What happened when the Hallmark Channel “ leaned into Christmas .”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

More From Forbes

Book review: walter isaacson’s fascinating ‘elon musk’.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

At a retreat over the summer, one of the attendees was rather rich and rather famous in the technology space. Having made enormous sums of money in a variety of startups and corporate settings, this entrepreneur had started all over yet again.

My question to him was if he still had the energy to pursue the impossible when failure to achieve it would in no way shrink his own living standards, along with those of his family. He well understood the question, only to comment that one reason he accepted venture capital funding (despite not needing it) was to keep the outside pressure on him. It wasn’t exactly the same as being in full start-up mode, but as close as someone worth hundreds of millions could approximate.

This conversation came to mind quite a lot in reading Walter Isaacson’s excellent new biography of Elon Musk, appropriately titled Elon Musk . Long after Musk’s fortune (one measured in hundreds of billions) was of the world’s greatest variety, Musk was (and still is) acting like Alabama coach Nick Saban at the end of championship games that his team has already won: stern, uncompromising, unrelenting. Yelling .

In Musk’s case, he somehow finds the time to direct herculean energy to companies that include Tesla, SpaceX, Solar City, Neuralink, the Boring Company, a robot company bent on creating humanoids (Optimus), throw in Twitter, etc. etc. etc. Back to this review’s introduction, at one point Isaacson (he shadowed Musk for two years) found himself at an Optimus meeting during which a frequently dissatisfied Musk told his employees to “Pretend we are a startup about to run out of money.” Well, yes. If Musk’s ambition, like that of the unnamed entrepreneur, were beaches and splendor, then we wouldn’t be reading about him. For Musk it’s about creating things against all odds. A major reason he’s very rich has to do with the fact that he’s always in start-up mode .

Musk needs to operate on the proverbial edge. As he explained it to Isaacson in 2021, “When you are no longer in a survive-or-die mode, it’s not that easy to get motivated every day.” In Musk’s case, it seems he’s always putting the proverbial chips on the table. He put his first $13 million from Zip2 into what became Paypal, the $250 million from Paypal was directed to SpaceX ($100 million) and Tesla ($70 million) among others, only for those two alone to nearly bankrupt him. Capital gains provide him with the means to continually pursue the impossible.

It brings up two points that can’t be made enough. To read Isaacson, along with past Musk biographers like Ashlee Vance and Jimmy Soni , is to see just how impressively foolish is the Federal Reserve, “easy money,” “costless capital” narrative that pundits from both sides of the ideological spectrum routinely write about in all-knowing fashion. Supposedly cash was “free” from 2009 until recent years. One hopes these always on the sideline commentators pick up Isaacson’s book, or ideally all three. The most persistent theme in each is how Musk has routinely stared death and bankruptcy in the face. Money is never easy .

Best High-Yield Savings Accounts Of September 2023

Best 5% interest savings accounts of september 2023.

Hopefully from this simple realization they’ll also happen on another truth: not only can the Fed not create credit, it also rather crucially cannot create time . At one point in the midst of Musk’s Twitter acquisition, and while in conversation with Isaacson, this singular individual juggling multiple companies and multiple kids, admitted that “I think I just need to think about Twitter less. Even this conversation right now is not time well spent.” Musk clearly wasn’t insulting Isaacson. At the same time, imagine what a day is like for Musk. One guesses is that following him would exhaust the follower. It’s a quick hint to Isaacson that a book about what it was like to shadow Musk might actually be more interesting than the book about his subject. And that’s saying something.

Needless to say, Musk doesn’t nor can he waste time. There’s the famous Brian Billick (Super Bowl winning coach of the Baltimore Ravens) quip about arriving for work a half hour before Jon Gruden says he does, and more broadly about how NFL coaches have a tendency to claim an overused sofa at team offices. Is this true, or is some of this just talk? In Musk’s case, his shadow confirms the 7-day weeks, sleeping on the factory floors, plus in the words of Musk, the expectation that he would “pull a rabbit out of the hat” over and over again, as the norm. Not only is capital never cheap or “costless” as the simpleminded claim, neither is time. Musk’s is spoken for. Economic growth is a consequence of indefatigable people being matched with capital. The Fed’s influence could not be overstated enough.

So is education and its value overstated. Isaacson reports that the principal at Musk’s elementary school in South Africa thought he was retarded. Musk himself looks back on school and comments that “I wasn’t really going to put an effort into things I thought were meaningless.” After which, what could Musk’s teachers and future professors teach him? Isaacson reminds readers with some regularity that Musk had designs on changing humanity through “the internet, sustainable energy, and space travel.” It all reads as ho-hum now in a sense, but it’s ho-hum because people like Musk have, or soon will, achieve their once ridiculed goals.

Indeed, in a book full of classic re-tells of business stories, Isaacson writes of Kimbal Musk (Elon’s brother) meeting with the head of The Toronto Star about Zip2’s (Zip2 Musk’s first startup, a searchable database of companies married to mapping capabilities), only for this seasoned executive to ask him “Do you honestly think you’re going to replace this?” “This” was a thick Yellow Pages book…

Of course, this is what the wealth unequal do, and more important it explains how they become wealth unequal in the first place: they pursue notions of commerce that, if they’ve actually been thought about by established businesses or businessmen, they’ve been ridiculed. Entrepreneurs like Musk don’t meet needs, rather they lead them. Which is another reason to be grateful for rich people. Absent them, how would the most ridiculed ideas be given a chance to succeed?

As readers know, or should know, Musk’s career has been defined by achieving in the face of enormous skepticism. Only the rich have the means to lose money on business ideas that are viewed as outlandish. Musk is both a doer and investor, which says so much.

Having made $21 million on Zip2, Musk directed $13 million of it to what became PayPal. Musk, Peter Thiel, Max Levchin and the other free thinkers at PayPal were literally trying to digitize banking and payments at a time when something north of 90% of all transactions were still completed via U.S. Mail. Isaacson writes that Musk earned $250 million in the sale of PayPal, a company that at present has a $59 billion valuation. At times it’s been higher than $300 billion. Shout it from the rooftops that the unequal get that way by leading us in directions we never knew we wanted, but that we wouldn’t return from.

Having made $250 million, Musk put the proverbial chips on the table again. One of his ventures was a $70 million investment in Tesla. Isaacson notes that Michael Moritz, one of the world’s greatest VCs, explained to Musk while turning him down for funding that “we’re not going to compete against Toyota,” that the whole Tesla concept was “mission impossible.” At present, Tesla’s market valuation at $743 billion is more than double that of Toyota’s. Sometimes investors focused on investing in the impossible pass on what exceeds the bounds of impossible. A $743 billion valuation is all the evidence one need of just how much Musk reaches when he gets to work.

Crucially, it’s more than that. In thinking about how many times Tesla nearly went bankrupt (Isaacson writes of how Musk’s second wife’s family – Talulah Riley – literally offered to mortgage their house to help Musk with several hundred thousand dollars – he wouldn’t allow it), it’s difficult to forget the ridicule formerly endured by Jeff Bezos. An appearance on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno comes to mind, during which Amazon’s lack of profitability became a laugh line for the host as Bezos squirmed uncomfortably. In Musk’s case, it was more than endless laughter about his electric car company. It’s instead Isaacson’s anecdote about how by 2018, “Tesla had become the most shorted stock in history.” Shorting is a crucial driver of market progress, and also the riskiest market speculation of all. This is how deep-seated skepticism about Musk formerly was. Even the smart money thought his ideas were completely nuts.

That so many were so short Tesla shares requires mention in concert with Musk’s present status as the world’s richest man. A major driver of his wealth has come from the run-up in Tesla shares. As Isaacson explains it, around the time that the world’s most prominent “short” (Jim Chanos) “declared that Tesla stock was basically worthless,” Musk “made the opposite bet. The Tesla board granted him the boldest pay package in American history, one that would pay him nothing if the stock price did not rise dramatically but that had the potential to pay out $100 billion or more if the company achieved an extraordinarily aggressive set of targets, including a leap in the production numbers, revenue, and stock price.” It was an all-or-nothing bet on himself, and Musk bet correctly. Just as money is never “easy,” neither is wealth creation. Musk’s wealth is born of miracle after miracle. And it’s also a consequence of a relentless of focus on costs.

In thinking about costs, to read Isaacson’s book is to be reminded of why, when politicians claim they’ll run the government like a business, they’re lying . For one, governments aren’t in the business of innovation, of offering something better or all new. Really, who if they have a good idea would hatch it in government? From there, governments are never in “survive-or-die” mode simply because they can always count on inflows from those in actual business world, including Musk. According to Isaacson, Musk himself is a major benefactor of the federal government. In 2021, his tax federal bill was $11 billion, the largest in history.

Back to government and business, Isaacson’s book really hums when he writes about Musk’s focus on costs. With the SpaceX rockets, Isaacson notes that Musk “did not try to eliminate all possible risks,” and he didn’t because he couldn’t do so while also aiming to be the low-cost provider of rockets into space. In which case, Musk was and is always looking to get rockets into space with fewer and fewer expensive inputs. In Musk’s words, “If we don’t end up adding back some parts later, we haven’t deleted enough.” And while Boeing’s space business employs 50,000, Isaacson indicates that it’s 500 at SpaceX. These are but two of many reasons that SpaceX is such a bargain for the federal government. Though wise minds can argue the good or bad of a “U.S.” space program, they can’t pretend that Musk is some kind crony ripping off the taxpayer.

This is important, particularly considering the desire of libertarians over the years to claim that Musk is a “crony capitalist.” Libertarians in particular would gain so much from reading Isaacson and others. To see how unlikely the success of SpaceX and Tesla were, to see how close Musk came to financial ruin more than once, is to understand that no “crony capitalist” would have ever pursued either venture. As mentioned in the discussion of time, Musk in so many ways has no life so dominated are his days by at least “a hundred command decisions,” decisions that will not infrequently be wrong. SpaceX isn’t a crony exploit when it’s remembered how substantially Musk undercuts the competition, and then the $7,500/car that normally wise free thinkers (I consider myself a libertarian, albeit minus all the world-is-ending pessimism) focus on completely misses the point: if we ignore that every maker of electric cars enjoyed and enjoys the same tax credit per car sold, we can’t ignore Tesla’s strategy, which was “to enter at the high end of the market, where customers are prepared to pay a premium.” In other words, a $7,500 tax credit was meaningless to initial Tesla buyers, but the quality of the car wasn’t. When the Model S won Motor Trend’s 2012 Car of the Year, the vote was unanimous. Libertarians have rendered “crony capitalist” and “rent seeking” meaningless by casting aspersions on seemingly all who allegedly receive government handouts. What they miss is that the problem isn’t crony capitalists, rather it’s a federal government that has its hands in everything.

Isaacson doesn’t spend too much time on the coronavirus crack-up by the political class, but that’s one of the book’s many good qualities. Put another way, the chapters in Isaacson’s accounting of Musk are short. This allows him to touch on all manner of subjects and business happenings, but not so much that the biography is slowed down. There’s a little bit about everything. Still, he spends enough time on the virus panic by the political class to point to Musk’s oh-so-correct assertion that “The harm from the coronavirus panic far exceeds that of the virus itself.” Indeed. The virus had been spreading for months, it had been in the news since early January of 2020, and people were adjusting. Freely. As even the New York Times admitted after politicians panicked, it was in the “red” U.S. states that locked down last in which people were taking the biggest precautions. On the matter of health and living, force is superfluous. At the same time, expert control is the stuff of crises. The experts won. Musk could have seen it coming. Isaacson quotes Musk as observing from “the algorithm” that informs decision-making at his companies that “Requirements from smart people are the most dangerous, because people are less likely to question them.” If there’s one line I would remove from own book about the virus panic (titled, When Politicians Panicked ), it would be the one about how the federal government’s only role in 2020 should have been “be careful.” I was wrong. Freedom, and freedom from the experts, is most important when we know so little about what perhaps threatens us.

Unknown to me until Isaacson’s book is that Musk was a co-founder of OpenAI with Sam Altman. How does he do it!? Disappointing to this non-techie is Musk’s own skepticism and fear of AI. My own view is that precisely because AI will enable machines to surpass humans, the future is amazing. It will be defined by more and more of us working all the time not because we have to (4 and 3-day work weeks will be the future, as I argued in The End of Work ), but because we want to. And we’ll want to because the automation of so much will free us to specialize in wonderful ways. Just as parabolic skis turned intermediates into experts on the slopes, AI will amplify the genius that resides within all of us. Not according to Musk. Isaacson reports that he views AI as “our biggest existential threat.” It doesn’t sound like him.

Musk also fears falling birthrates. That he does contradicts his fear of AI. Think about it. If machines are poised to do and think for us, logic dictates that the babies lucky enough to be coming into the world now will be the productive equivalent of thousands from the past.

Most appealing were Musk’s comments about the why behind his products and services. About the Cybertrucks that many no doubt await, Musk has been clear that “I don’t care if no one buys it,” that “I don’t do focus groups.” Amen. Entrepreneurs once again lead consumer desires as opposed to meeting them.

Most economically informative in a book that could teach economics exponentially better than the textbooks actually used to teach economics, was Musk’s comment to Isaacson that “If you make things fast, you can find out fast.” Please use the latter as a metaphor for the healthy nature of recessions. During recessions, we rush to mistakes because we’re forced to. Recessions are the recovery, contra interventionist politicians who delay the recovery with wasteful spending. Capital is limited as this book makes clear over and over again. How counter to reason and logic that politicians and economists believe government spending is necessary during downturns. Quite the opposite.

Most uplifting beyond the world’s richest man constantly inventing the future is Neuralink, yet another Musk creation. One of the aims of this corporation is to “restore full-body functionality to someone who has a severed spinal cord.”

Are there weaknesses? My take is that the first 100-200 pages of the book didn’t grab as quickly as the final 400 did. There were also odd insertions that don’t indict Isaacson, but do indict the economics of modern publishing. There quite simply isn’t enough editing. After one of the SpaceX rocket crashes on Kwajalein, Isaacson inserted apropos of seemingly nothing that brother Kimbal “tried to cheer everyone up that evening by cooking an outdoor meal.” It read as out of place, and what validates this assertion is that later in the book Isaacson explains that Kimbal’s cooking had periodically calmed corporate nerves before. Eighteen pages later Isaacson wrote of Musk’s 6,000 square foot house in Bel-Air, then in the very next paragraph he writes of a “tender” period in Musk’s marriage to first wife Justine, when “they would walk to Kepler’s Books near Palo Alto, arms around each other’s waists.” The two anecdotes didn’t go together.

Early in the book, Isaacson writes of the first internet boom, “when one could just slap .com onto any fantasy and wait for the thunder of Porsches to descend from Sand Hill Road with venture capitalists waving checks.” Isaacson knows better. He knows better from Musk himself, but also because he’s written so much about Silicon Valley genius. It’s never that easy. That he’s written a book about Musk certifies Musk as a genius, only for Zip2 and PayPal to be created amid the first internet boom. Musk never had it as easy as Isaacson describes it when the internet first became a thing, and he hasn’t had it easy since.

From Isaacson’s wonderful book, readers will understand why Musk hasn’t nor will he ever have it easy. “Fantasy” is difficult, and even more difficult to find financing for. In which case, we can be grateful that Musk’s ambitions are much bigger than money despite money being a highly worthy driver of ambition. Musk really is trying to change the world given his view that the “arteries harden” of civilizations that “quit taking risks.” How fortunate we are to have Elon Musk, how fun it is to read about him, and how exciting if we could know now whom Isaacson will write about ten years from now. If we could know, we would be worth many millions, and perhaps billionaires by the time the book comes out.

- Editorial Standards

- Forbes Accolades

How the Elon Musk biography exposes Walter Isaacson

One way to keep musk’s myth intact is simply not to check things out..

By Elizabeth Lopatto , a reporter who writes about tech, money, and human behavior. She joined The Verge in 2014 as science editor. Previously, she was a reporter at Bloomberg.

Share this story

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24145486/226378_Twitter_Risk_Elon_Musk_WJoel.jpg)

The trouble began days before the biography was even published.

CNN had a story summarizing an excerpt of Walter Isaacson’s Elon Musk that claimed Musk had shut down SpaceX’s satellite network, Starlink, to prevent a “Ukrainian sneak attack” on the Russian navy. The Washington Post followed it up, publishing the excerpt where Isaacson claimed Musk had essentially shut down a military offensive on a personal whim.

This reporting did not pass the smell test to me, and I said so at the time ; I wondered about the sourcing. One of the things that anyone covering Elon Musk for long enough has to reckon with is that he loves to tell hilarious lies. For instance:

- “Funding secured.” Remember when Elon Musk pretended he was going to take Tesla private and had everything in order, and then whoopsie, that was not at all true ?

- Tesla share sales. Of course, there’s the time in April 2022 when he sold Tesla shares and said he had no further sales planned , followed by him selling more Tesla shares in August 2022, when he said he was done selling Tesla shares . He sold more shares in November 2022 .

- Tesla and Bitcoin. Remember when Musk said, “ I might pump but I don’t dump ,” and then Tesla sold 75 percent of its Bitcoin ?

- The staged 2016 Autopilot demo video. In the demo video, which features the title card “The car is driving by itself,” the car was not driving by itself , Tesla’s director of Autopilot software said in a deposition. Musk himself asked for that copy.

- The batteries in Teslas will be exchangeable. Refueling your EV will just be a battery swap that will happen faster than pumping gas.

- The time he said Teslas might fly. I am not making this up . He really said he’d replace the rear seats with thrusters, and journalists spent time trying to figure out what the fuck that meant .

The thing you learn after a while on the Musk beat is that his most self-aggrandizing statements usually bear the least resemblance to reality. Musk says a lot of stuff! Some of it is exaggeration, and some isn’t true at all.

Isaacson’s sweeping 670-page biography has an intense amount of access to the man at its center. The problem is the man is Elon Musk, a guy who in 2011 promised to get us to space in just three years . In reality, the first SpaceX crew launched into orbit almost a decade later. Sure, access is the appeal of the biography — but access gives Musk lots of chances to sell his own mythology.

I wanted to know if Isaacson had done his homework

So when I opened the Musk biography, I wanted to know if Isaacson had done his homework. The first thing I did was flip to the back, where the author lists his sources for the Ukraine thing. They are: interviews with Musk, Gwynne Shotwell, and Jared Birchall (Musk’s body man); emails from Lauren Dreyer; and text messages from Mykhailo Fedorov, “provided by Elon Musk.” Other sources are news articles, one of which was about SpaceX curbing Ukraine’s use of drones . Crucially, though, this article says nothing about Ukrainian submarines — instead, it’s primarily about aerial vehicles.

In his book, Isaacson writes:

Throughout the evening and into the night, he [Musk] personally took charge of the situation. Allowing the use of Starlink for the attack, he concluded, could be a disaster for the world. So he secretly told his engineers to turn off coverage within a hundred kilometers of the Crimean coast. As a result, when the Ukrainian drone subs got near the Russian fleet in Sevastopol, they lost connectivity and washed ashore harmlessly.

That final sentence is arresting, isn’t it? I could find no support for it in any of the news articles that Isaacson listed as sources for this chapter. There is a Financial Times story that confirms some Starlink outages during a Ukrainian push against the Russians, but it says nothing about drone subs or washing ashore harmlessly. A New York Times article confirms Musk doesn’t want Starlink running drones but says nothing about drone subs.

What could the possible source for this sentence be? In the following paragraph, Isaacson quotes text messages from Fedorov, who had “secretly shared with him [Musk] the details of how the drone subs were crucial” to the Ukrainians. Not very secret now, I suppose.

Musk disputed Isaacson’s account on Twitter: “SpaceX did not deactivate anything,” he said. “There was an emergency request from government authorities to activate Starlink all the way to Sevastopol,” he went on, though he did not specify which government’s authorities . “If I had agreed to their request, then SpaceX would be explicitly complicit in a major act of war and conflict escalation.”

Isaacson caved immediately :

To clarify on the Starlink issue: the Ukrainians THOUGHT coverage was enabled all the way to Crimea, but it was not. They asked Musk to enable it for their drone sub attack on the Russian fleet. Musk did not enable it, because he thought, probably correctly, that would cause a major war.

Tremendous statement. “To clarify” obfuscates what’s going on: is Isaacson saying his book is wrong? Surely that is what this means since “future editions will be updated” to correct it . The Post corrected its excerpt , anyway. “The Ukrainians thought” — which Ukrainians, and how did Isaacson know their thinking? In his listed sources, we have only the text messages of one Ukrainian, who, for diplomatic purposes, may be obscuring what he knows. “They asked Musk to enable it for their drone attack” is an entirely different account than the one given in the book, which says Musk shut off existing coverage rather than approving extended coverage; what could possibly be the source here? And of course, the last sentence — “Musk did not enable it because he thought, probably correctly, that would cause a major war” — is simple boot-licking.

We are dealing with not one but two unreliable narrators: Musk and Isaacson himself

Isaacson “clarified” further in another tweet. ”Based on my conversations with Musk, I mistakenly thought the policy to not allow Starlink to be used for an attack on Crimea had been first decided on the night of the Ukrainian attempted sneak attack that night,” he wrote on Twitter . “He now says that the policy had been implemented earlier, but the Ukrainians did not know it, and that night he simply reaffirmed the policy.”

There was a way to find out what’s true here, and it would have been to interview more sources, both Ukrainian and US military ones. Isaacson chose not to. Musk’s word was good enough for him — and so, when Musk contested the characterization, Isaacson rolled over.

I am lingering here because it highlights a major problem with Isaacson’s biography. We are dealing with not one but two unreliable narrators: Musk and Isaacson himself. After all, just before issuing his clarification, Isaacson had been touting a walk through the SpaceX factory with CBS’s David Pogue to promote his book.

Isaacson writes a specific kind of biography. There is even a “genius” boxed set of his biographies that includes Benjamin Franklin, Leonardo da Vinci, Albert Einstein, and — somewhat incongruously — Steve Jobs.

One way to keep Musk’s myth intact is simply not to check things out

Having made a pattern of writing biographies of important men — and one important woman, Jennifer Doudna of CRISPR fame — Isaacson is now in the position of a kind of kingmaker. To keep up his pattern, everyone he writes about implicitly is branded a genius.

One way to keep Musk’s myth intact is simply not to check things out. Within the first three paragraphs of the book, Isaacson describes a wilderness survival camp Musk attended, where “every few years, one of the kids would die.” This is a striking claim! I flipped to the “notes” section to see if Isaacson had interviewed any of Musk’s schoolmates. He hadn’t. There are no news articles backing it up, either. So what is the source? Presumably one or more of the Musks — Elon is quoted directly as saying the counselors told him not to die like another kid in a previous year.