Knowledge is power

Stay in the know about climate impacts and solutions. Subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

By clicking submit, you agree to share your email address with the site owner and Mailchimp to receive emails from the site owner. Use the unsubscribe link in those emails to opt out at any time.

Yale Climate Connections

What is ‘climate justice’?

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

Climate change, an inherently social issue, can upset anyone’s daily life in countless ways. But not all climate impacts are created equal, or distributed equally. From extreme weather to rising sea levels, the effects of climate change often have disproportionate effects on historically marginalized or underserved communities.

“Climate justice” is a term, and more than that a movement, that acknowledges climate change can have disproportionately harmful social, economic, and public health impacts on disinvested populations. Advocates for climate justice are striving to have these inequities addressed head-on through long-term mitigation and adaptation strategies.

The following are key factors to consider in thinking about climate justice:

1) Climate justice begins with recognizing key groups are differently affected by climate change.

From the United Nations and the IPCC to the NAACP , many organizations are connecting the dots between civil rights and climate change.

As a UN blog describes it: “The impacts of climate change will not be borne equally or fairly, between rich and poor, women and men, and older and younger generations.”

“Climate change is happening now and to all of us. No country or community is immune,” according to UN Secretary-General António Guterres. “And, as is always the case, the poor and vulnerable are the first to suffer and the worst hit.”

Generally, many victims of climate change also have disproportionately low responsibility for causing the emissions responsible for climate change in the first place – particularly youth or people of any age living in developing countries that produce fewer emissions per capita than is the case in the major polluting countries.

2) Climate impacts can exacerbate inequitable social conditions.

Low-income communities, people of color, indigenous people, people with disabilities, older or very young people, women – all can be more susceptible to risks posed by climate impacts like raging storms and floods, increasing wildfire, severe heat, poor air quality, access to food and water, and disappearing shorelines.

Here are a few examples of how some communities may be more affected by these impacts than others – and may have fewer resources to handle those impacts, too:

- Communities of color are often more at risk from air pollution, according to both the NAACP , the American Lung Association, and countless research papers.

- Seniors, people with disabilities , and people with chronic illnesses may have a harder time living through periods of severe heat, or being able to quickly and safely evacuate from major storms or fire.

- People with limited income may live in subsidized housing, which too often is located in a flood plain . Their housing options may also have inadequate insulation, mold problems, or air conditioning to effectively combat severe heat or cope with strong storms. Economically challenged people may also be hard-pressed to afford flood or fire insurance, rebuild homes, or pay for steep medical bills after catastrophe strikes.

- Language barriers can make it difficult for immigrant communities to get early information about incoming storms or weather disasters or wildfires, or to communicate effectively with first responders in the midst of an evacuation order.

- Some indigenous communities are already seeing their homes and livelihoods lost to rising sea levels or drought. For example, the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe has lost nearly all of its land and is relocating to higher ground.

- Prolonged drought and flooding can affect food supply or distribution, making it harder for people to access affordable, healthy food.

- Today’s youth and future generations will experience more profound impacts of climate change as it worsens over time, from direct adverse health impacts to the financial implications of needing to shore-up infrastructure and other adaptation and mitigation needs.

3) Momentum is building for climate justice solutions.

Organizations like the Climate Justice Alliance are working to bring race, gender, and class considerations to the center of the climate action discussion. The NAACP is also advocating for efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and advance clean energy while promoting food justice, transportation equity, and civil rights in emergency planning. And the UN and IPCC each continue to place greater emphasis on these issues.

In a June 29, 2020, Washington Post column headlined “ Climate Change is also a racial justice problem ,” reporter Sarah Kaplan wrote, “You can’t build a just and equitable society on a planet that’s been destabilized by human activities. Nor can you stop the world from warming without the experience and the expertise of those most affected by it.”

One indicator of the growing momentum of climate justice as a social issue is Democratic presidential hopeful Joe Biden’s campaign support for a “plan to secure environmental justice and equitable economic opportunity in a clean energy future…. Addressing environmental and climate justice is a core tenet.”

In the end, there is no single way to define, let alone champion, climate justice. But in combination with other current social justice movements – perhaps epitomized and including, but not limited to, the Black Lives Matter movement – many experts see climate justice becoming an increasingly significant component of overall concerns raised by climate change.

Also see: How inequality grows in the aftermath of hurricanes

Republish This Story

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

We love it when others republish our articles. Most of our content – other than images – is available to republish for free under a Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Here’s what to do:

- Credit us by name. For example: “This article was originally published by Yale Climate Connections.” Our preferred style for bylines is AUTHOR NAME, Yale Climate Connections.

- Include a link to yaleclimateconnections.org .

- Don’t edit the stories other than small changes for editorial style. It is OK to change the headline as long as you don’t misrepresent the content.

- Check image sources carefully before republishing. Where noted in photo captions, images have been licensed from their original creators under Creative Commons or are in the public domain. In other cases, we paid to license the images from Getty or similar sources and they are not available for republication.

- Contact us with questions.

by Daisy Simmons, Yale Climate Connections July 29, 2020

Daisy Simmons

Daisy Simmons, assistant editor at Yale Climate Connections, is a creative, research-driven storyteller with 25 years of professional editorial experience. With a purposeful focus on covering solutions... More by Daisy Simmons

Freshman Isaiah Swilley from Bourbonnais, Illinois, takes a practice dive at the Burr Gymnasium Pool. Howard is the only HBCU with a Division I swimming and diving team.

The Injustice of Climate Change

How extreme weather disproportionately affects communities of color.

Climate change is a global phenomenon that affects everyone on the planet – but it does not affect everyone equally. The consequences of climate change are as devastating as they are wide-ranging. From extreme heat to severe cold, from droughts to flooding, from wildfires to hurricanes and tornadoes, the fingerprint of climate change can be detected on an abundance of extreme weather events and environmental changes that disproportionately impact communities of color.

In the United States, the bulk of carbon emissions come from more affluent areas; but it is the poorer, under-resourced, oftentimes Black and minority communities that are bearing the brunt of a rapidly changing global climate – without benefiting from the consumption of resources that overwhelmingly contribute to it. When disaster strikes, it is those same communities that suffer the most and the longest; after others have rebuilt and moved on, Black communities are often still left reeling from the crisis. “Climate change is the issue of our time,” says Terri Adams, PhD, a professor of criminology in the Department of Sociology and Criminology. “And Howard needs to be a leader in the fields of climate change and environmental justice because of the disproportionate impacts on communities of color.”

Not-So-Natural Disasters

In Howard’s environmental inequality class during the Fall 2021 semester, visiting assistant professor Michelle Dovil, PhD, Department of Sociology and Criminology, mentions to her undergraduate students over Zoom that she prefers to use the term “natural hazards” rather than “natural disasters.”

“When we say, ‘natural disaster,’ it lacks accountability for those who should be accountable, like government officials,” she says. Dovil’s issue with this language has less to do with its descriptiveness and more to do with what it seems to imply or omit.

The implication of nature-based language like “natural disaster” is that Black individuals living in communities that are hit by storms or other phenomena are either the victims of poor luck or their own bad choices. The term suggests that the resulting “disaster” is not a social construct, but a product of nature.

“But it’s not coincidence; it’s intentional,” she says. “We also have to acknowledge the social, economic, political, and geological vulnerabilities these communities might be facing prior to a disaster. It is ultimately the natural hazard coming into contact with a potentially vulnerable social condition that creates the disaster.”

Stuck or Displaced

Dovil’s passion for environmental justice began, like many other professionals who work in this field, with Hurricane Katrina. She remembers watching TV coverage of the hurricane as a teenager and seeing images of people wading through chest-high water crying out for help – the vast majority of them African American. “I knew something was wrong,” she says. “In a lot of ways, [Katrina] uncovered the social fabric of our society.”

There are numerous reasons why the Black communities and residents of New Orleans were more vulnerable to the effects of a powerful hurricane and, as a result, represented a disproportionate share of the storm’s victims.

In the context of Katrina and other similar natural hazards, Dovil has studied a phenomenon she refers to as “place attachment,” an idea that captures why individuals might not evacuate in the face of an incoming natural hazard as well as why they might return to or continue to live in high-risk areas.

In a lot of ways, [Katrina] uncovered the social fabric of our society."

She explains that the act of evacuating requires resources – a car, money, someplace to go. Simply put, many low-income Americans do not have the ability to evacuate, even if they believe it would be in their own best interest to do so. Whether to stay or leave is less of a personal choice and more of a decision that was made for them by factors beyond their control.

But even if they have the means to leave, evacuation still presents a risk that might be just as ominous as the incoming storm. For those who face job insecurity or the regular threat of job loss, they cannot afford to misjudge the severity or impact of the crisis. If they were to evacuate and the hurricane did not prove to be as powerful or devastating as predicted, they would likely be fired for missing work. During the spate of devastating tornadoes in December 2021, employees of a candle factory in Mayfield, Kentucky , were told they would be fired if they left to seek shelter at home. Eight employees were killed when the factory was struck by a tornado.

“[Place attachment] has a lot to do with dependency,” says Dovil. So much of their lives and livelihoods are directly tied to the place they live that, to leave it behind, even temporarily, would be to risk losing it permanently.

For many Black individuals facing a potential disaster, their strongest means of insurance is themselves. Black families lag behind in homeownership rates at 44 percent, compared to nearly 74 percent of white families. Black homeowners have reported more difficulty getting insurance claims paid. Some whose homes were passed from generation to generation may not have home insurance. The only way to safeguard their familial wealth is to do whatever they personally can to physically protect the home from the ravages of the storm.

In addition to their social circumstances, Black communities are also disproportionately affected by virtue of their geographical location and environmental characteristics as well as the state of their local infrastructure. Prior to and after an extreme weather event, they are often displaced. The places they end up are more often lower-income, poorly resourced – and well positioned for devastation from the next nature-induced crisis.

Studies have shown that underserved populations are far more vulnerable in such events. A wildfire vulnerability index created by researchers at the University of Washington and the Nature Conservancy revealed that Native Americans are more susceptible to devastation from wildfires. African Americans were also among the list of those who would face harsher recovery. Other factors, such as housing, income, and health, were used to determine that these communities are more likely to struggle in the recovery from these natural events. And the poor air quality that arises as a result of wildfires has the potential to do long-term damage to residents in these communities who don’t have the ability to move elsewhere.

Gentrification has relegated Black communities to dense urban environments that are more exposed to the ravages of extreme heat and severe flooding. The heat becomes intensified when it is reflected off the concrete and the asphalt. As many in these poorer communities don’t have air conditioning or have to work outside, they are more susceptible to heat stroke.

According to Nea Maloo, M.Arch, lecturer in the College of Engineering and Architecture, introducing green spaces into urban landscapes could help offset some of the rising heat seen in cities. In addition to increasing gentrification, Black communities also have to contest with what Bradford Grant, M.Arch, professor in the Department of Architecture, describes as a type of “reverse gentrification.” Many inland Black communities are being displaced to live in areas closer to the coastal waterfronts that are more vulnerable to flooding and rising water levels, situations that are becoming more common and chronic with rising global temperatures.

Black communities are often situated in low-lying floodplains with poorer drainage systems. After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Hurricane Matthew in South Carolina in 2011, Hurricane Harvey in Houston, Texas in 2017, and many more, Black residents were more likely to be in harm’s way and to experience property damage.

“Segregation has been an instrument to divide this country, not only socially, but physically,” Grant says. “The built environment is really about where people live and where they work in segregated systems.”

Overlooked and Underserved

A 2018 study entitled “ As Disaster Costs Rise, So Does Inequality ” revealed that for white, affluent communities, natural hazards are actually profitable. To be sure, these events cause significant hardship and loss. But when looking at the total financial resources in these communities before an extreme weather event and after, they actually see an influx of wealth because of federal emergency funding and insurance payouts.

Many Black communities, on the other hand, see wealth decline after a crisis. The New York Times has reported that funding from the Federal Emergency Management Authority (FEMA) disproportionately goes to white survivors. Even when Black survivors encounter almost identical hardship, they still do not get equal amounts of funding. In addition, Black residents are more likely to rent than to own and are less likely to have either renter’s or homeowner’s insurance. So when their property is destroyed, they are less likely to receive the financial compensation needed to recover.

Resilience in the Face of Vulnerability

“Environmental justice is social justice,” Dovil says. “It is a slow violence, but it is still violence against poor Black and brown people that have to deal with these [issues] every single day.” Part of the ability to resist further devastation done to the Black community as a result of climate change and natural hazards begins with recognizing that fact. When Rubin Patterson, PhD, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, first became passionate about environmental justice, he says there wasn’t as much attention given to the field by other Black studies scholars and leaders.

“So many leaders in the Black community were focusing on other issues, and understandably so,” Patterson says, mentioning criminal justice reform, education outcomes, and health equity. There was a misconception that environmentalism was focused merely on conservation and not on social justice.

But now, Patterson says, there is more attention given to the subject and broad recognition that environmental justice and climate change have wide-ranging consequences that require urgent responses to safeguard African American communities in particular.

It is a slow violence, but it is still violence against poor Black and Brown people."

However, Black Americans are still largely underrepresented in industries, like clean technology, that are important for mitigating the effects of climate change.

“A lack of pipelines of entry into these industries can leave the historically marginalized communities of color once again looking in from the outside,” Patterson says. Without these pipelines, climate change mitigation efforts could simply recreate and reinforce existing social and racial inequalities.

There is an endless list of careers for which Howard is responsible for producing a disproportionate share of Black individuals in those professional ranks – doctors, lawyers, pharmacists, scientists, and more. However, Patterson wants to add more to the list – he wants Howard to produce a substantial share of Black environmental leaders and climate scientists, too.

“Preparing members of these communities to shape, implement, and manage the emerging clean tech industries is also a form of environmental justice,” Patterson says. “That is what I want to contribute to at Howard University.”

Developing Future Leaders

Howard’s environmental studies program is only five years old. But “our program has included equity in its curriculum from its inception [and] it’s been interdisciplinary,” says Janelle Burke, PhD, associate professor in the Department of Biology and director of the Interdisciplinary Environmental Studies Program.

The program was conceived and created by a collection of faculty, of which Rubin Patterson, PhD, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, was one of the leaders. When Patterson arrived at Howard in 2014 as a professor in sociology, creating an environmental studies program was one of his top priorities. “I was trying to advance environmental studies amongst members of the Black community,” Patterson says. “Black people are disproportionately adversely affected by pollution and climate matters and the like, but less likely to be at the forefront of institutions addressing those concerns.”

Patterson believed that if he could combine the subjects of Africana studies and environmental studies together, he could convey how important climate change is to students who have made social justice their personal mission and focus of their academic pursuits.

Faculty members who participate in the program represent a range of disciplines, including African American studies, biology, chemistry, English, history, mathematics, sociology, political science, psychology, and physics. In the environmental inequality course, one of the program’s core classes that was created and first taught by Patterson and is currently being taught by visiting assistant professor Michelle Dovil, PhD, Department of Sociology and Criminology, it’s sometimes possible to forget the focus is on the environment.

“Part of the environmental justice conversation is labor exploitation, right. And so, we have to also deal with people going out and putting themselves at risk [of pollution or exposure to natural hazards], just so they can pay rent, just so they can survive,” Dovil says. “We also have to talk about affordable housing [and] the issue with the eviction moratorium.” The curriculum also includes the digital divide, food insecurity, health care disparities, and more.

Patterson and the other faculty members are currently working to expand the environmental studies program. They want it to be more than just a concentration; they would like it to be a freestanding major housed within a brand-new department – the Department of Earth, Environment, and Equity. The proposal is currently under consideration.

Part of the need and justification for expanding the program is to be able to bring in even more students and conduct more research so as to help scale adaptation and mitigation efforts in vulnerable communities.

“If we can organically integrate Black studies and environmental studies, then that’d be a kind of a clever way of getting Black students to enter that space,” Patterson says. “They’re going to see how richly rewarding it is intellectually and otherwise. And then we’ll have these new Black environmental and climate leaders.”

News from the Columbia Climate School

Why Climate Change is an Environmental Justice Issue

September 21-27 is Climate Week in New York City. Join us for a series of online events and blog posts covering the climate crisis and pointing us towards action.

While COVID-19 has killed 200,000 Americans so far, communities of color have borne disproportionately greater impacts of the pandemic. Black, Indigenous and LatinX Americans are at least three times more likely to die of COVID than whites. In 23 states, there were 3.5 times more cases among American Indian and Alaskan Native communities than in white communities. Many of the reasons these communities of color are falling victim to the pandemic are the same reasons why they are hardest hit by the impacts of climate change.

How communities of color are affected by climate change

Climate change is a threat to everyone’s physical health, mental health, air, water, food and shelter, but some groups—socially and economically disadvantaged ones—face the greatest risks. This is because of where they live, their health, income, language barriers, and limited access to resources. In the U.S., these more vulnerable communities are largely the communities of color, immigrants, low-income communities and people for whom English is not their native language. As time goes on, they will suffer the worst impacts of climate change, unless we recognize that fighting climate change and environmental justice are inextricably linked.

The U.S. is facing warming temperatures and more intense and frequent heat waves as the climate changes. Higher temperatures lead to more deaths and illness, hospital and emergency room visits, and birth defects. Extreme heat can cause heat cramps, heat stroke, heat exhaustion, hyperthermia, and dehydration.

Disadvantaged communities have higher rates of health conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Heat stress can exacerbate heart disease and diabetes, and warming temperatures result in more pollen and smog, which can worsen asthma and COPD. Heat waves also affect birth outcomes. A study of the impact of California heat waves from 1999 to 2011 on infants found that mortality rates were highest for Black infants. Moreover, disadvantaged communities often lack access to good medical care and health insurance.

African Americans are three times more likely than whites to live in old, crowded or inferior housing; residents of homes with poor insulation and no air conditioning are particularly susceptible to the effects of increased heat. In addition, low-income areas in cities have been found to be five to 12 degrees hotter than higher income neighborhoods because they have fewer trees and parks, and more asphalt that retains heat.

Extreme weather events

While climate change cannot be definitively linked to any particular extreme weather event, incidents of heat waves, droughts, wildfires, heavy downpours, winter storms, floods and hurricanes have increased and climate change is expected to make them more frequent and intense.

Extreme weather events can cause injury, illness, and death. Changes in precipitation patterns and warming water temperatures enable bacteria, viruses, parasites and toxic algae to flourish; heavy rains and flooding can pollute drinking water and increase water contamination, potentially causing gastrointestinal illnesses like diarrhea and damaging livers and kidneys.

Extreme weather events also disrupt electrical power, water systems and transportation, as well as the communication networks needed to access emergency services and health care. Disadvantaged communities are particularly at risk because subpar housing with old infrastructure may be more vulnerable to power outages, water issues and damage. Residents of these communities may lack adequate health care, medicines, health insurance, and access to public health warnings in a language they can understand. In addition, they may not have access to transportation to escape the impacts of extreme weather, or home insurance and other resources to relocate or rebuild after a disaster. Communities of color are also less likely to receive adequate protection against disasters or a prompt response in case of emergencies. In addition to physical hardships, the stress and anxiety of dealing with these impacts of extreme weather can end up exacerbating mental health problems such as depression, post-traumatic stress and suicide.

Poor air quality

While climate change does not cause poor air quality , burning fossil fuels does; and climate change can worsen air quality. Heat waves cause air masses to remain stagnant and prevent air pollution from moving away. Warmer temperatures lead to the creation of more smog, particularly during summer. And wildfires, fueled by heat waves and drought, produce smoke that contains toxic pollutants.

Living with polluted air can lead to heart and lung diseases, aggravate allergies and asthma and cause premature death. People who live in urban areas with air pollution, or who have medical conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, asthma or COPD, are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of air pollution.

Black people are three times more likely to die from air pollution than white people. This is in part because they are 70 percent more likely to live in counties that are in violation of federal air pollution standards. A University of Minnesota study found that, on average, people of color are exposed to 38 percent higher levels of nitrogen dioxide outdoor air pollution than white people. One reason for the high COVID-19 death rate among African Americans is that cumulative exposure to air pollution leads to a significant increase in the COVID death rate, according to a new peer-reviewed study.

More people of color live in places that are polluted with toxic waste, which can lead to illnesses such as cancer, heart disease, high blood pressure and asthma. These pre-existing conditions put people at higher risk for the more severe effects of COVID-19.

The fact that disadvantaged communities are in some of the most polluted environments in the U.S. is no coincidence. Communities of color are often chosen as sites for landfills, chemical plants, bus terminals and other dirty businesses because corporations know it’s harder for these residents to object. They usually lack the connections to lawmakers who could protect them and can’t afford to hire technical or legal help to put up a fight. They may not understand how they will be impacted, perhaps because the information is not in their native language. A 1987 report showed that race was the single most important factor in determining where to locate a toxic waste facility in the U.S. It found that “Communities with the greatest number of commercial hazardous waste facilities had the highest composition of racial and ethnic residents.”

For example, while Blacks make up only 13 percent of the U.S. population, 68 percent live within 30 miles of a coal plant. LatinX people are 17 percent of the population, but 39 percent of them live near coal plants. A new report found that about 2,000 official and potential highly contaminated Superfund sites are at risk of flooding due to sea level rise; the areas around these sites are mainly communities of color and low-income communities.

The link between climate change and environmental justice

Mary Annaïse Heglar , a climate justice essayist and former writer-in-residence at the Earth Institute, asserts that climate change is actually the product of racism. “It started with conquest, genocides, slavery, and colonialism,” she wrote . “That is the moment when White men’s relationship with living things became extractive and disharmonious. Everything was for the taking; everything was for sale. The fossil fuel industry was literally built on the backs and over the graves of Indigenous people around the globe, as they were forced off their land and either slaughtered or subjugated — from the Arab world to Africa, from Asia to the Americas. Again, it was no accident.”

The harmful impacts of climate change are linked to historical neglect and racism. When Black people migrated North from the South in the early 20th century, many did not have jobs or money; consequently they were forced to live in substandard housing. Jim Crow laws in the South reinforced racial segregation, prohibiting Blacks from moving into white neighborhoods. In the 1930s through the 1960s, the federal government’s “redlining” policy denied federally backed mortgages and credit to minority neighborhoods. As a result, African Americans had limited access to better homes and all the advantages that went with them—a healthy environment, better schools and healthcare, and more food options.

Prime examples of environmental injustice

Poor sanitation in the U.S.

Catherine Flowers, founder of the Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice and a senior fellow for the Center for Earth Ethics , which is affiliated with the Earth Institute, is from Lowndes County, Alabama. As a child growing up in a poor, mostly Black rural area with less than 10,000 residents, she used an outhouse before her family installed indoor plumbing. After leaving to get an education, Flowers returned to Alabama in 2002 and still saw extreme disparities in rural wastewater treatment. She visited many homes with sewage backing up into their homes or pooling in their yards, as many residents couldn’t afford onsite wastewater treatment. She is still advocating for proper sanitation in Lowndes. As a result of her work, Baylor College’s National School of Tropical Medicine conducted a peer-reviewed study which showed that over 30 percent of Lowndes County residents had hookworm and other tropical parasites due to poor sanitation.

”We’re also seeing that there is a relationship between [wastewater and] COVID infections,” added Flowers. “We don’t know exactly what it is yet—but you can actually measure wastewater to determine the level of infections in the community before people start showing up with the illness.” In Lowndes, one of every 18 residents has COVID-19; it is one of the highest infection rates in the U.S.

Today, Flowers works at the intersection between climate change and wastewater throughout the U.S. “The more we see sea level rise, the more we’re going to have wastewater problems,” she said. Her new book, Waste, One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret , due out in November, shows how proper sanitation is essential as climate change will likely bring sewage to more backyards everywhere, not just in poor communities.

Cancer Alley

An 85-mile stretch along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana, hosts the densest concentration of petrochemical companies in the U.S. There have been so many cases of cancer and death in the area that it became known as “Cancer Alley.”

Most of these petrochemical plants are situated near towns that are largely poor and Black. There are 30 large plants within 10 miles of mostly Black St. Gabriel, with 13 within three miles. St. James Parish, whose population is roughly half Black and half white, has over 30 petrochemical plants, but the majority are located in the district that is 80 percent Black.

These plants not only emit greenhouse gases that are exacerbating climate change, but the particulate matter they expel can contain hundreds of different chemicals. Chronic exposure to this air pollution can lead to heart and respiratory illnesses and diabetes. As such, it is no surprise that St. James Parish is among the 20 U.S. counties with the highest per-capita death rates from COVID-19.

Despite efforts of the residents to fight back, seven new petrochemical plants have been approved since 2015; five more are awaiting approval.

Hurricane Katrina

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina, a Category 3 storm, caused extensive destruction in New Orleans and its environs. More than half of the 1,200 people who died were Black and 80 percent of the homes that were destroyed belonged to Black residents. The mostly Black neighborhoods of New Orleans East and the Lower Ninth Ward were hit hardest by Katrina because while the levees in white areas had been shored up after earlier hurricanes, these poorer neighborhoods had received less government funding for flood protection. After the hurricane, when initial plans for rebuilding were in process, white neighborhoods again got priority, even if they had experienced less flooding. Eventually federal funds were directed toward the rebuilding of parts of the Lower Ninth Ward and New Orleans East and the strengthening of their levees.

In 2014, the city of Flint, MI, whose population is 56.6 percent Black, decided to draw its drinking water from the polluted Flint River in order to save money until a new pipeline from Lake Huron could be built. Previously the city had brought in treated drinking water from Detroit. Because the river had been used by industry as an illegal waste dump for many years, the water was corrosive, but officials failed to treat it. As a result, the water leached lead from the city’s aging pipelines. Officials claimed the water was safe, but more than 40 percent of the homes had elevated lead levels. As almost 100,000 residents — including 9,000 children — drank lead-laced water, lead levels in the children’s blood doubled and tripled in some neighborhoods, putting them at high risk for neurological damage.

In October, 2015, the city began importing water from Detroit again. An ongoing project to replace lead service pipes is expected to be complete by the end of November. And just recently, Flint victims were awarded a settlement of $600 million, with 80 percent of it designated for the affected children.

Steps to achieve environmental justice

As the founder of the Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice, Catherine Flowers works to implement the best practices to reduce environmental injustice. Here are some key strategies she prescribes.

- Acknowledge the damage and try to repair it.

- Clean up sites where environmental damage has been done.

- Create an equitable system for decision-making so there is not an undue burden placed on disadvantaged communities. “Lobbyists that represent these [polluting] companies shouldn’t have more influence than the people who live in the area that are impacted by it,” said Flowers. “We need to make sure that the people that live in the community are sitting at the table when decisions are being made about what’s located in their community.”

- Call out the officials who are making decisions that are not in the best interest of the people they represent.

- Vote to put in place representatives that listen to their constituents rather than the people and companies that donate to them.

- Provide climate training to help people become more engaged. For example, the Climate Reality Project (Flowers sits on its board of directors) trains everyday people to fight for solutions and change in their communities.

- Partner with universities to conduct peer-reviewed studies of health impacts to help validate and draw attention to the experiences of disadvantaged communities.

- Build cleaner and greener. “We cannot discount the impact this could have on communities around the world,” said Flowers. “If we don’t pollute and we have a Green New Deal to build better, cleaner, and greener, then we won’t have these environmental justice issues.”

Related Posts

Mountaineering, Death and Climate Risk in the Patagonian Andes

A Showcase Combining Knowledge and Action

In Morningside Park, a Restored Waterfall, a Renewed Pond, and a Blueprint for Climate-Resilient Public Space

Injustice of any kind? It really does not matter. Unless people change their idea of materialism madness and understand the fact that they are threatened, we will get nowhere. When was the last time humans have done much of anything out of compassion if it would alter their own lifestyles?

I wonder if governments (particularly of modernized nations like America, the UK and China) have purposely chosen to ignore the issue of climate change? I agree that most of it falls on things like industrial shipping, transportation and processing, but governemnt incentivization is another issue with climate justice as a whole.

Simple VersionCOVID-19 has tragically claimed the lives of 200,000 Americans. However, it has disproportionately affected communities of color. Black, Indigenous, and LatinX Americans are at least three times more likely to die from COVID than their white counterparts. In 23 states, American Indian and Alaskan Native communities reported 3.5 times more cases compared to white communities. These same communities are also the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Factors such as location, health, income, language barriers, and limited resources contribute to their heightened susceptibility. These marginalized groups include communities of color, immigrants, low-income populations, and non-native English speakers. If not addressed, these groups will suffer the harshest consequences of climate change. It is crucial to acknowledge that addressing environmental justice and combating climate change go hand in hand. The rising temperatures and increased intensity of natural disasters in the U.S. are indicative of this pressing issue.

Hello Renée Cho, I agree with your position on climate change; the events that occur heavily affect the health of the economy; Your connection with how COVID-19 still affects people with the rise of climate change events. We’ve been seeing records of air pollution continuing to showcase dramatic numbers. With the long-term symptoms of COVID-19 being asthma and heart complications, air pollution can worsen those problems and make survivors of COVID-19 vulnerable. Your connection with these ex-patients explains how aggressive climate change can change someone’s life around so negatively. Also, we’ve seen aggressive heat waves hitting across the globe sending people of all ages into hospitals. If adults and children are barely handling such temperatures, imagine how infants are the most susceptible to suffering from these heat waves as their bodies are not meant to withstand such heat. These heat waves are affecting ex-COVID-19 individuals with asthma as the thick air makes it difficult to breathe. We cannot afford such catastrophes caused by these damages.

6/12/24, 2:48 pm

Get the Columbia Climate School Newsletter

Climate Justice in the Anthropocene: An Introductory Reading List

Justice discourse in the Anthropocene has shown us that perhaps we aren’t as homogeneous of an “Anthros” as we’d expect.

As the alarm bells have made it urgently clear—humanity has breached planetary boundaries —causing anthropogenic climate change and environmental disaster across the world. By burning fossil fuels, overconsuming material resources, and creating endless waste, we have disrupted Earth’s ecosystems, exacerbating natural hazards with effects lasting longer than human lifetimes. But who is the “we” being referred to here? The climate crisis is no longer a simple issue of “objective” science but an issue of political discourse and pop culture. Across the globe, the effects of anthropogenic climate change are experienced unevenly, disproportionately so for vulnerable communities within and between nations. We should be critical in our efforts to mitigate, adapt to, and be transformative in the face of climate change, ensuring that we are not weaponizing emergency in the process and ignoring issues of environmental justice and equity .

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

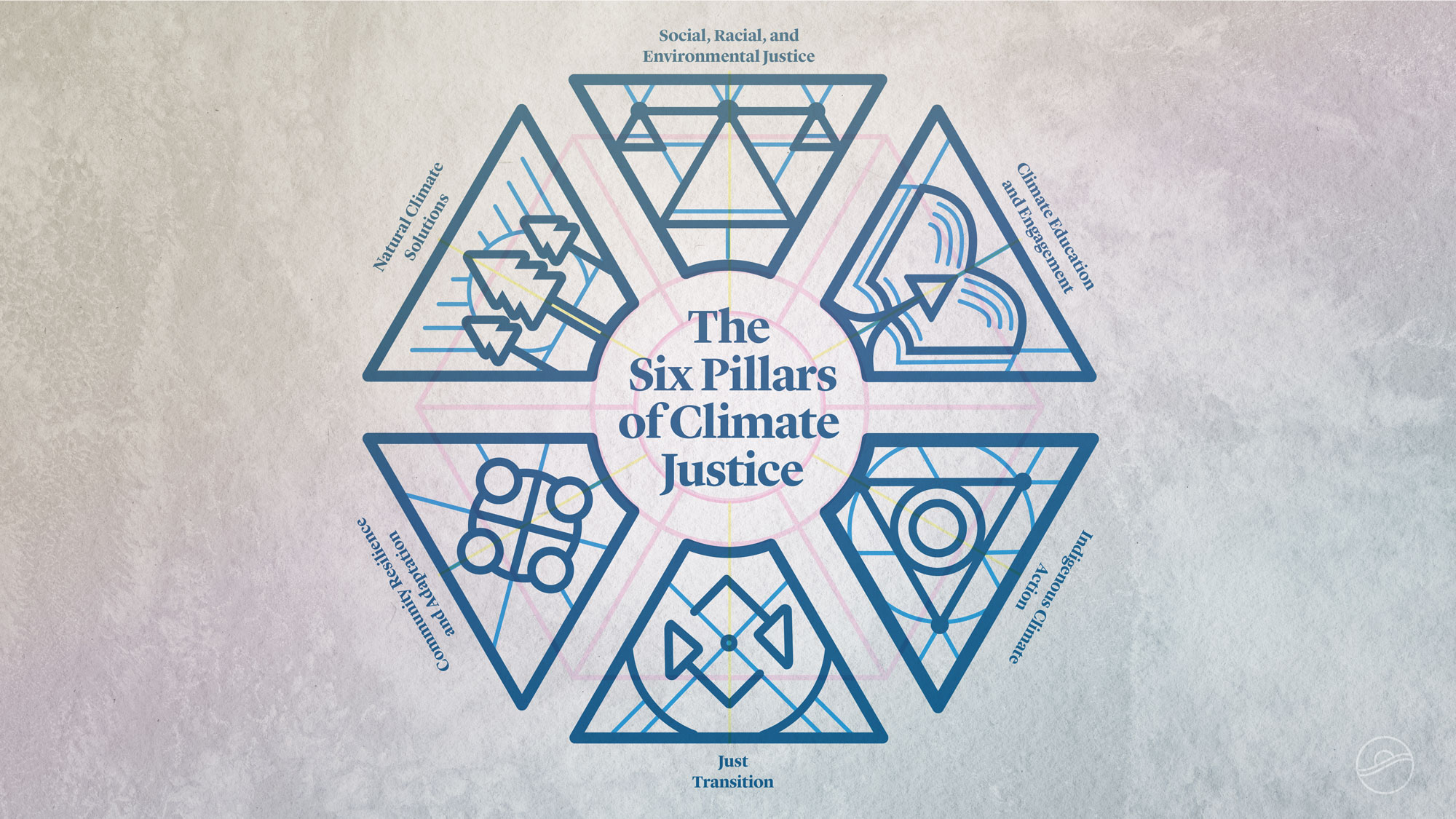

Climate justice, a movement emerging from the US environmental justice movement in the 1960s, attempts to re-center communities most vulnerable to the climate crisis in decision-making. Rather than viewing the climate crisis as a result of a homogenous humanity that has degraded the planet, climate justice assigns responsibility to oppressive systems and actors that have fueled the crisis. This reading list provides an introduction to climate justice and seeks to unsettle some of the familiar, dominant discourses of climate change.

Mike Hulme, “ Geographical Work at the Boundaries of Climate Change ,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 33, no. 1 (2008): 5–11.

To define climate change is a political act. Hulme explores key discourse, questions, issues, and framings around the anthropogenic climate crisis. He most notably unpacks the universalization of the climate crisis, the boundary-setting of global warming at 2° Celsius by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and the exclusion of certain forms of knowledge generation. Hulme helps to set the scene for a critical climate justice, understanding how space, place, power, and culture form a normative understanding of the climate crisis.

Arvind Jasrotia, “ Fighting 2° Celsius: The Quest for Climate Justice ,” Journal of the Indian Law Institute 58, no. 1 (2016): 55–82.

The IPCC in the fifth assessment report concluded that for humanity to avoid catastrophic impacts from anthropogenic climate change, warming since pre-industrial times must remain under 2° Celsius. Jasrotia unpacks the way the IPCC, alongside other climate organizations, negotiated this target, and its disparate impacts on developing countries. Pointing out that “climate change presents the largest (re)distributive dilemma of human history,” Jasrotia considers the atmosphere as a global common, questioning how best to equitably distribute the carbon budget. He then takes the reader through critical junctures in the history of international climate negotiations and explores how different forms of power pervade these spaces.

Elizabeth A. Povinelli, “ The Rhetorics of Recognition in Geontopower ,” Philosophy & Rhetoric 48, no. 4 (2015): 428–42.

“Geontopower”—at the center of climate justice—challenges how we come to understand what’s considered life and non-life, and therefore, create structures of governance that rule over what we have come to understand as “non-life.” Povinelli challenges this distinction, as Indigenous communities across the world have done for centuries. It’s possible to blow up a mountain and extract its minerals because it’s considered non-life; as Povinelli notes, “we cannot take away a soul they [mountains] do not have.” Povinelli grounds the creation of geontopower in the history of colonialism and Indigenous erasure, providing context to how and why non-life (nature) is governed in an environmentally destructive way.

Rikard Warlenius, “ Decolonizing the Atmosphere: The Climate Justice Movement on Climate Debt ,” The Journal of Environment & Development 27, no. 2 (2018): 131–55.

A core tenet of the climate justice movement is the concept of climate debt: those historically and disproportionately responsible for the climate crisis must pay those who are on the frontlines of disaster. Warlenius explores this concept through the notion of “decolonizing the atmosphere,” or the idea that the colonial powers have not only subjugated peoples and lands but also have taken up disproportionately more atmospheric “space” by overshooting the global carbon budget. As developing countries begin to industrialize, there is little room for their fossil emissions in the atmosphere. Warlenius argues that this is unfair and unjust and that paying climate debt is one avenue where one can “simply ask those who made the mess to clean it up.”

Federico Demaria, François Schneider, Filka Sekulova, and Joan Martinez-Alier, “ What Is Degrowth? From an Activist Slogan to a Social Movement ,” Environmental Values 22, no. 2 (2013): 191–215.

A popular call from activists, scientists, and academics alike is for degrowth discourse to be embedded in environmental policy. What is degrowth? “Degrowth” is a social movement that calls for the reduction of consumption (materialized as Gross Domestic Product) in developed nations while encouraging investment in social services and the care economy. As Demaria et al. explains, the term degrowth has re-politicized environmental issues, with the term and the movement both being oversimplified, co-opted, and simply misunderstood. This paper traces the idea of degrowth throughout history and geographies, attempting to capture the complexity and nuance of it as a call moving towards climate justice.

Kyle Powys Whyte, “ Indigenous Women, Climate Change Impacts, and Collective Action ,” Hypatia 29, no. 3 (2014): 599–616.

Indigenous communities are vital social actors in the fight against the anthropogenic climate crisis; as they steward approximately one-quarter of world’s land area and 40 percent of the world’s protected areas. For Indigenous communities especially, the anthropogenic climate crisis has the potential to completely disrupt what Whyte refers to as collective continuance , which captures Indigenous relationships with nature, secure Indigenous identities, and intergenerational sustainability of communal ties. Additionally, Whyte sheds light on the intersectional experiences of Indigenous women in the face of anthropogenic climate change.

Farhana Sultana, “ Suffering for Water, Suffering from Water: Emotional Geographies of Resource Access, Control, and Conflict ,” Geoforum 42, no. 2 (March 2011): 163–172.

Conflicts over safe water for consumption, agriculture, and production are often mediated by material and social relations. Drawing upon political ecology scholarship, Sultana explores how this critical resource is even more troubled by emotional relations, that is, the relations between the home, individual body, space, and feelings. Her discussion helps clarify the connections between gender and natural resource management in moving towards climate justice. Using a case study from Bangladesh, she explores how issues of disparate access and use of water impact water, society, and gender relations.

Filomina Chioma Steady, “ Women, Climate Change and Liberation in Africa ,” Race, Gender & Class 21, no. 1/2 (2014): 312–33.

The impacts of climate crisis have been seen and felt by African women, who provide the bulk of labor for agriculture, water procurement, fuel, animal husbandry, and natural resource stewardship on that continent. Steady uses an ecofeminist lens to highlight the positions of African women in climate concerns, including the degradation of forests, water insecurity, agricultural yield variation, and mitigation of and adaptation to natural hazards. She also provides context to explain how neo-colonialism and globalization are key drivers of the continued maldevelopment of the African continent and the unique impact experienced by African women as a result.

Adelle Thomas, April Baptiste, Rosanne Martyr-Koller, Patrick Pringle, and Kevon Rhiney, “ Climate Change and Small Island Developing States ,” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 45 (October 2020): 1–27.

Small Island Developing States (SIDs) have been identified by the United Nations as especially vulnerable to the anthropogenic climate crisis, primarily due to unpredicted sea level rise and the increased frequency and intensity of natural hazards. The Association of Small Island Developing States drove the 1.5° Celsius global temperature target at the 2015 Paris Climate Negotiations, bringing it down from 2° Celsius target in prior years. Thomas et al. notes that while SIDs have had a negligible impact on greenhouse gas emissions, they face disproportionately more risk, vulnerability, and exposure to natural hazards. The centering of SIDs in climate justice discourse has highlighted the need for climate reparations, loss and damage funding, and climate migration planning.

Avner de Shalit, “ Climate Change Refugees, Compensation, and Rectification ,” The Monist 94, no. 3 (2011): 310–28.

Who is pathologized as a result of climate change? De Shalit focuses on the evacuation and the destruction of homes due to natural hazards as “environmental displacement[s]” and explores how people become environmental refugees because of anthropogenic climate change. Solutions, such as loss and damage compensation, have been proposed to rectify the loss of space and place experienced by vulnerable communities. De Shalit challenges the notion of monetary compensation as an acceptable form of reparations for environmental refugees, arguing that not only does such compensation place a monetary value on a landscape that is incommensurable, but it gives license for polluters to continue worsening anthropogenic climate change—as they can simply pay for it later.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

Spider in the Telescope: The Mechanization of Astronomy

NASA’s Europa Clipper

Archimedes Rediscovered: Technology and Ancient History

The Strange Experiments of Henry Cavendish

Recent posts.

- Ghosts in the Machine

- How to Be a British Villain

- The Mayaguez Incident: The Last Chapter of the Vietnam War

- Autism Research, Dungan Food, and Forest Histories

- All Travelers are Infiltrators: An Introduction to the Study of Travel Writing

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

New to climate change?

Climate justice.

Some countries and populations have benefited more than others from the industries and technologies that are causing climate change. And at the same time, the countries that have benefited the least are more likely to be suffering first and worst because of climate change.

Climate justice is the principle that the benefits reaped from activities that cause climate change and the burdens of climate change impacts should be distributed fairly. Climate justice means that countries that became wealthy through unrestricted climate pollution have the greatest responsibility to not only stop warming the planet, but also to help other countries adapt to climate change and develop economically with nonpolluting technologies.

Climate justice also calls for fairness in environmental decision-making. The principle supports centering populations that are least responsible for, and most vulnerable to, the climate crisis as decision makers in global and regional plans to address the crisis. It also means acknowledging that climate change threatens basic human rights principles, which hold that all people are born with equal dignity and rights, including to food , water , and other resources needed to support health. Calling for climate justice, rather than climate action, has implications for policymaking, diplomacy, academic study and activism, by bringing attention to how different responses to climate change distribute harms and benefits, and who gets a role in forming those responses.

The unequal causes and effects of climate change

Wealthy, industrialized nations have released most of the greenhouse gas pollution to date — meaning they’ve played an outsized role in causing climate change. 4 Climate justice calls for these countries, along with multinational corporations that have become wealthy through polluting industries, to pay their “climate debt” to the rest of the world. In this view, stopping their greenhouse gas emissions, while hugely important, is not enough to fully pay the debt from over a century of pollution; these actors also have a responsibility to share wealth, technology, and other benefits of industrialization with the countries least responsible for the climate crisis, to help them cope with the effects of climate change and build clean energy systems and industries.

A climate justice perspective also brings attention to inequalities within countries. Within high and low income countries, wealthier people are more likely to enjoy energy-intensive homes, private cars, leisure travel, and other comforts that both exacerbate climate change and buffer them from impacts like extreme heat . Climate change also worsens pre-existing social inequalities stemming from structural racism, socioeconomic marginalization, and other forms of social exclusion. In the U.S., for example, communities of color and immigrant communities are more likely to be located in places where climate risks are more severe, such as in flood zones or urban heat islands . 5

The unequal impacts of taking action on climate change

Reducing climate pollution greatly benefits everyone. Yet the way we achieve these reductions could either improve or worsen current patterns of inequity for marginalized groups. For example, a carbon tax that makes it expensive to emit greenhouse gases is a part of many climate proposals; climate justice would additionally demand that these taxes be structured in a way that protects low-income people who are already struggling to pay for gasoline, home heating and cooling , and other basic energy needs. 6

Additionally, the principle of a “just transition” considers the economic and labor impacts of a transition to a nonpolluting economy. This incorporates the needs of workers employed in—and the communities supported by—the fossil fuel industry and other industries that contribute to climate change. 7 For example, the U.S. federal government offers over $180 billion in funding to assist coal field and power plant communities in economic diversification, infrastructure and workforce development as the coal industry declines. 8

Climate justice as a movement

Calls for climate justice grew out of a larger “environmental justice” movement, which is concerned with the ways pollution, land degradation, and other environmental problems harm already vulnerable people and communities who have contributed the least to, but suffer the most from, environmental problems. Global South nations, Black, Indigenous, and other people of the global majority and women—who have been historically excluded from decision making—have led the push for climate justice, arguing that climate change endangers their health and livelihoods. In recent years, younger people have also been leading the call for just climate action, observing that they will bear the heaviest burden from the climate change that past generations have contributed to, and demanding immediate action from those in positions of power.

Published March 14, 2022.

1 King, Andrew D., and Luke J. Harrington. “The Inequality of Climate Change From 1.5 to 2°C of Global Warming.” Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 45, no. 10, 28 May 2018, doi:10.1029/2018GL078430.

2 Martin, Richard. “ Climate Change: Why the Tropical Poor Will Suffer Most. ” MIT Technology Review, 17 June 2015.

3 Diffenbaugh, Noah S., and Marshall Burke. “ Global Warming Has Increased Global Economic Inequality .” PNAS, vol. 116, no. 20, 14 May 2019, doi:10.1073/pnas.1816020116.

4 Ritchie, Hannah. “ Who Has Contributed Most to Global CO2 Emissions? ” Our World in Data, 1 Oct. 2019.

5 Gamble, J.L., et al. “ Ch. 9: Populations of Concern. ” The Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health in the United States: A Scientific Assessment, U.S. Global Change Research Program, 4 Apr. 2016.

6 Fremstad, Anders, and Mark Paul. “ The Impact of a Carbon Tax on Inequality .” Ecological Economics, vol. 163, 29 May 2019, doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.04.016.

7 Smith, Samantha. Just Transition Centre, 2017, Just Transition: A Report for the OECD .

8 Interagency Working Group on Coal & Power Plant Communities & Economic Revitalization , 25 Feb 2022.

More Resources for Learning

Keep exploring.

With more Explainers from our library:

Urban Heat Islands

Cities and Climate Change

Food Systems and Agriculture

Mit climate news in your inbox.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Climate Justice

There is overwhelming evidence that human activities are changing the climate system. [ 1 ] The emission of greenhouse gases is resulting in increased temperatures, rising sea-levels, and severe weather events (such as storm surges). These climatic changes raise a number of issues of justice. These include (but are not limited to) the following

- How do we assess the impacts of climate change?

- What climate responsibilities do current generations have to future generations?

- How should political actors take into account the risks and uncertainties involved in climate projections?

- Who has what responsibilities to address climate change?

- Given that there is a limited “greenhouse gas budget” how should it be distributed?

- What constraints should regulate and constrain climate policies?

- Given high levels of noncompliance with climate responsibilities how should we make trade-offs between competing principles of climate justice?

Before considering these normative issues, it is important to introduce some scientific terms. Climate scientists often refer to “mitigation” and “adaptation”. Mitigation involves either reducing the emission of greenhouse gases or creating greenhouse gas sinks (which absorb greenhouse gases), or both. Adaptation involves making changes to people’s context so that they can cope better with a world undergoing climatic changes. Examples of adaptation might be constructing buildings that can cope better with extreme heat, or building seawalls that can cope with storm surges. It is arguable that this typology is incomplete. Suppose that humans do not mitigate by enough so the climate system continues to change; and suppose that human societies also fail to implement the necessary adaptation policies and so people are unable to enjoy the kinds of lives to which they are entitled. Then, many would argue, they are entitled to compensation.

1. Isolationism and Integrationism

2. assessing climate impacts, 3.1 principles of intergenerational justice, 3.2 intertemporal discounting, 3.3 objections and concerns, 4. risk and uncertainty, 5.1 the climate action question, 5.2.1 the polluter pays principle, 5.2.2 the beneficiary pays principle, 5.2.3 the ability to pay principle, 5.3 the political action question and first-order and second-order responsibilities, 5.4 who are the duty bearers, 6.1 subsistence, 6.2 equality, 7.1 mitigation and alternative energy sources, 7.2 population, 7.3 geoengineering, 8. climate justice in a nonideal world, 9. concluding remarks, other internet resources, related entries.

It is helpful to draw attention to a distinction between two different ways in which one might approach issues of climate justice.

One approach—Isolationism—holds that it is best to treat the ethical issues posed by climate change in isolation from other issues (such as poverty, migration, trade and so forth). The isolationist seeks to bracket these other considerations and treat climate change on its own. A second approach—Integrationism—holds that it is best to treat the ethical issues posed by climate change in light of a general theory of justice and in conjunction with other issues (such as poverty, development and so on).

Some philosophers have adopted an isolationist approach. Some, for example, propose principles for allocating rights to emit greenhouse gases that treat greenhouse gases in isolation from other issues ( Section 6.2 ). Two related reasons are given for this approach. First, some argue that there is value in simplifying the issue, and since introducing these other concerns would complicate the question it is worth bracketing them out. Second, some make a related pragmatic argument about the implications of adopting an integrationist approach for reaching agreement in climate negotiations. They argue that insisting that climate justice be pursued in light of a general theory, and in conjunction with other issues, would be a recipe for deadlock because there is often deep disagreement about what theory of justice is correct. For this reason, they propose bracketing out other phenomena and treating climate change in isolation (Blomfield 2019: 24; Gosseries 2005: 283; L. Meyer & Roser 2006: 239).

In reply, those who favour an integrationist approach tend to offer the following considerations. First, they argue that in order to treat climate change in isolation there would need to be something special about it that warranted separate treatment. However, they argue, climate change is not special in this way. For example, it impacts on the same interests (people’s interests in food and water; their health; their access to land and so on) as other phenomena (such as the distribution of economic resources, poverty and poverty alleviation, migration, and trade). Furthermore, they claim that the same distributive principles seem to be salient for climate change as they are for other phenomena. If, for example, one thinks that individuals have human rights to meet their socio-economic needs then this should surely also bear on questions of climate justice too since it provides a reason to combat climate change and a reason to distribute responsibilities so that they do not burden the poor and vulnerable. Another way of putting this point is that when people engage in deliberation about, say, how the costs of tackling climate change should be distributed then—so Integrationists claim—they inescapably end up drawing on more general values (such as “people have a right to a decent standard of living” or “people should be accountable for their choices”) (Caney 2005: 763 & 765–766). If philosophers eschew Integrationism and they try to answer questions such as “who should bear the burdens of combating climate change?” in an isolationist fashion—bracketing out, for example, what economic rights persons have—then, so the argument runs, we end up with very counter-intuitive conclusions (Caney 2018b: 682–684).

Whether this is true or not cannot be fully resolved in advance. Rather it can only be decided by engaging in a normative analysis of climate change and seeing whether it is borne out.

A second point that those who favour an Integrationist approach might make is that climate change is causally interconnected with a wide variety of other phenomena—such as economic growth, poverty reduction, migration, health, trade, natural resource ownership, and cultural rights—such that it is artificial to treat it on its own. Climate change does not present itself to us as a discrete problem that can be treated separately. Rather it is part and parcel of a larger process. It is an upshot of people’s activity (primarily through the use of energy) and, as such, it is causally intertwined with economic growth, poverty alleviation, urban design, and land use. Furthermore, the effects of climatic change are often mediated through other factors such as poverty, existing infrastructures, and the responsiveness of political authorities. They interact with existing inequalities and vulnerability, producing what Leichenko and O’Brien (2008) term “double exposures”. In addition to this, the extraction of fossil fuels and the industry built around it often directly harm the same interests (such as health and access to land) that are harmed by the emission of greenhouse gases. So, from this point of view, it seems artificial to focus on the effect of the emissions rather than the whole phenomenon. Finally, the policies proposed to tackle climate change themselves affect a wide range of other phenomena (impacting on land use, access to food, health, poverty alleviation, biodiversity loss, individual liberty, and so on). Given this any attempt to cordon off climate change and apply principles of justice to it in isolation seems misguided and quixotic.

As we shall see—especially when we consider the distribution of responsibilities and the application of principles of distributive justice to the greenhouse gas budget—it matters a great deal whether one takes an Isolationist or Integrationist perspective.

With this point duly noted, we can turn to the substantive issues.

One question of justice that arises is “What account of persons” interests should be employed to evaluate the impacts of climate change?’ Such an account is needed for several reasons. First, we need it to design adaptation policies for we need to know what kind of protection people are entitled to and what interests ought to be protected. In addition to this, when we are considering proposed temperature targets we need to be able to evaluate them, and to do this we need to have some account of persons’ interests by which to compare the different possibilities. For many years the appropriate temperature target was assumed by many to be that of keeping the increase in global mean temperatures from pre-industrial times to below 2°C. However, some have campaigned for lower targets. This is reflected in the Paris Agreement (2015, Other Internet Resources ) which specified that the target should be

[h]olding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. (Article 2.1(a))

Others, by contrast, have argued that higher temperatures are permissible. For example, William Nordhaus, a leading climate economist, has argued that if we implement what he deems to be the “optimal” climate policy the temperature increase would be 3.5°C in 2100 (when compared to a 1900 baseline) (Nordhaus 2018: 348 Fig 4).

Theories of distributive justice concern the just distribution of burdens and benefits. We therefore need to know how we should conceive of “burdens” and “benefits”. Different theories of distributive justice have put forward different accounts of what it is that persons should have fair shares of (the distribuendum ) (see entries on distributive justice and egalitarianism ).

When we consider climate change, different accounts of the distribuendum are highly likely to converge in very many cases. Climate change results in many dying (because of severe weather events, such as extreme heatwaves, flooding, and storm surges). It leads to droughts and crop failure and thus threatens people’s interests in food and water. It leads to an increase in certain diseases. These impacts—threats to life, food and water, and to health—would be condemned by many, if not all, theories of distributive justice. (For a detailed discussion of the implications of different accounts of the distribuenda of distributive justice for the evaluation of climatic impacts see Page [2006: 50–77].)

Some, however, would argue that to limit our focus to these interests (in life, health, food and water) is too narrow. They hold that some persons have deep attachments to certain places, such as the land that they have traditionally inhabited, and that being rooted in a particular place is an integral part of what makes their life go well. On this view, forcible displacement results in a non-substitutable loss. This is highly pertinent in the case of climate change since many indigenous peoples will be forcibly displaced from traditional homelands. This is true both of those in small island states and coastal settlements, as well as of inland communities forced to move because of environmental degradation to their traditional lands. Many argue, on this basis, that climate change constitutes a form of cultural injustice (de Shalit 2011, Heyward 2014, Whyte 2016). An adequate theory of climate justice must then consider whether persons’ have such cultural rights.

This last example also helps to underscore another important point, namely that which account of persons’ interests is adopted can have considerable practical implications, affecting what temperature target to employ and what form adaptation should take.

The key issue here concerns the relationship between persons’ interests, on the one hand, and changes in the climate system, on the other. On some views people’s interests are such that a change in the climate system might—at least in principle—be made up for through adaptation and/or through the provision of other goods. If, for example, one thinks that distributive justice is concerned solely with persons’ wealth and income, then the loss of a good (such as one’s house) because of climatic changes can be compensated for by a transfer of wealth and/or income.

Other accounts of persons’ interests will not, however, sanction this kind of “compensation”. Those who think that some persons’ good is bound up with a certain place or territory will think that climate change inflicts on such people a loss that cannot be compensated for. Protecting their interests necessarily requires the environment to be a certain way (de Shalit 2011; Heyward 2014 esp. 156–157; Whyte 2016).

To put the point in other words, the key concern is about “substitutability” (Neumayer 2003: 37–40). The question is whether one can substitute the loss of nature with the provision of other goods. Different accounts of justice will yield different answers to this. This take us to a long-standing debate in ecological economics and ethics between proponents of what has been termed “weak sustainability” (which permits the substitution of capital for the loss of nature) and proponents of “strong sustainability” (which denies the possibility of such substitution) (Neumayer 2003).

Four further points are in order.

First, it would be a mistake simply to employ an account of the distribuendum and then apply that to evaluate climatic impacts without considering whether that account adequately reflects the values and ethical orientations of affected communities. See, in this context, Krushil Watene’s (2016) evaluation of the extent to which the “capability” approach can accommodate the insights of Maori philosophy concerning the value of nature. (See entry on capability approach for information on the capability approach and relevant sources.)

Second, it is worth noting that once one has an account of the relevant interests a further question is how one incorporates them into a theory of justice. For example, some have argued that many of the adverse impacts described above can accurately be described as threatening people’s human rights (Caney 2010b). This view maintains that persons have certain human rights—to life, health, water, food, not to be displaced—and that climate change is unjust because it violates these human rights. Others are sceptical of the applicability of human rights, arguing that they are too inflexible and are unable to provide guidance when trade-offs are necessary (Moellendorf 2014: 24–26 & 230–235).

Moellendorf suggests that we should instead adopt what he terms an “Antipoverty Principle”: this judges climate impacts (and climate policies) in terms of their impact on poverty (Moellendorf 2014: 22–24). This, however, will be vulnerable to the objection that it is unduly narrow in its focus, for climate change has harmful effects that cannot simply be reduced to its effect on poverty levels (such as its effects on political self-determination, people’s ability to practise their traditional ways of life, and their right not to be displaced) (Gardiner 2017: 441–443).

Another approach would be to follow the practice of many climate economists. They employ what they term the “social cost of carbon” where this calculates “a monetized value of the present and future damages caused by the emission of a ton of CO 2 ” (Fleurbaey et al. 2019: 84). What stance one adopts here will, then, depend on one’s more general theory of justice and normative public policy.

Third, the focus so far has been on the entitlements of individuals. However, some will argue that this is too restrictive and that a comprehensive account would include the rights of collective units to be self-determining. The clearest and starkest (but not, of course, the only) illustration of this is the destruction of small island states.

Fourth, the focus, so far, has been on the impacts on human beings. On some accounts, this is incomplete for it excludes nonhuman animals (Cripps 2013: chapter 4). Clearly, evaluating such claims raises questions that go beyond this entry. The point here is just that if the interests of other creatures are included then this will have implications for the evaluation of climatic impacts.

3. Intergenerational Justice

The question of what climate target to aim for will also depend on what responsibilities members of one generation have to future generations. The emission of some greenhouse gases can have an impact far into the future. For example, CO 2 lasts in the atmosphere for “hundreds of thousands of years” (Allen, Dube, & Solecki 2019: 64). So while climate change affects large numbers of people alive now, many of the impacts of climate change will fall on future generations. To know what temperature target is appropriate it is necessary, then, to have an account of our responsibilities to future generations and to know how much weight, if any, to attribute to their interests.

Such an account is also needed for two further reasons. First, the question of who should bear the burdens of climate change has an intergenerational dimension. Some, for example, have argued that it would be fair to impose some of the costs of mitigating (and adapting to) climate change on future generations (Rendall 2011).

Finally, there is a fixed quantity of greenhouse gases which can be emitted. [ 2 ] Considering how this should be shared also raises questions of intergenerational justice for if there is a fixed greenhouse gas budget we need to consider what claims, if any, future people have to emit greenhouse gases.

A number of different principles of intergenerational justice have been proposed. Many for example, adopt a sufficientarian position and hold that justice requires merely that all persons be above a certain specified threshold. (For sophisticated analyses see L. Meyer & Roser 2009 and Page 2006: 90–95; 2007.)

One challenge for this view will, of course, be determining how to specify this threshold. Many, however, will grant that a sufficiency condition is necessary even if it is hard to specify. Some may though query whether it is sufficient. For example, a sufficientarian view would allow members of one generation to leave future generations worse off than them just so long as they are above a certain threshold. This will strike many as too weak. Consider a case where one generation could leave future people much better off than the sufficientarian threshold at no (or little) cost. Here it would seem inadequate to say that current generations need only ensure that future people do not fall beneath the sufficientarian’s designated threshold.

Some adopt more demanding accounts of intertemporal justice which avoid these problems. For example, in their book Sustainability for a Warming Planet (2015) Humberto Llavador, John E. Roemer, and Joaquim Silvestre defend what they term “growth sustainability”. They explain it as follows:

Growth sustainability (say, at 25% per generation) means to find that path of economic activity that maximizes the welfare of the present generation, subject to guaranteeing that welfare grows at least at 25% per generation, forever after. (Llavador, Roemer & Silvestre 2015: 4)