Select "Patients / Caregivers / Public" or "Researchers / Professionals" to filter your results. To further refine your search, toggle appropriate sections on or off.

What Is Cancer Research?

Home > Patients, Caregivers, and Advocates > About Cancer > What Is Cancer Research?

Cancer research transforms and saves lives.

The purpose of studying cancer is to develop safe and effective methods to prevent, detect, diagnose, treat, and, ultimately, cure the collections of diseases we call cancer. The study of cancer is called oncology.

Why Cancer Research Is Important

Cancer research is important because the better we understand these diseases, the more progress we will make toward diminishing the tremendous human and economic tolls of cancer.

Research has helped us accumulate extensive knowledge about the biological processes involved in cancer onset, growth, and spread in the body. Those discoveries have led to more effective and targeted treatments and prevention strategies.

Breakthroughs in prevention, early detection, screening, diagnosis, and treatment are often the result of research and discoveries made by scientists in a wide array of disciplines over decades and even generations. Ultimately, cancer research requires partnerships and collaborations involving researchers, clinicians, patients, and others to translate yesterday’s discoveries into today’s advances and tomorrow’s cures.

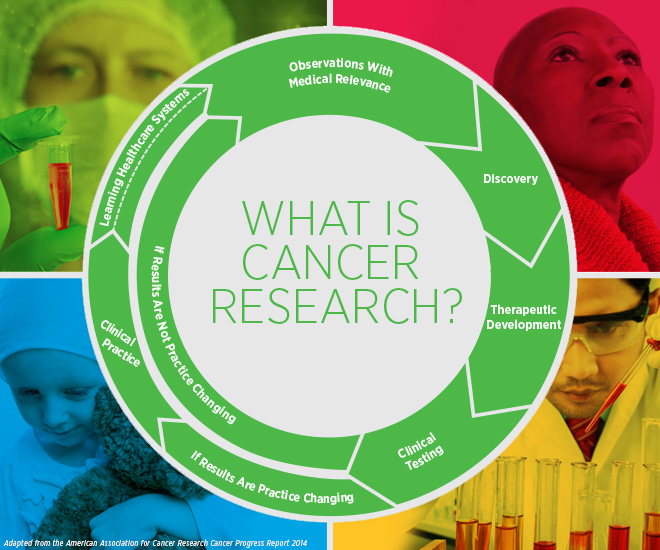

The Cancer Research Cycle

Research progress is often not linear, but cyclical and ongoing. Advances are the result of constantly building on earlier discoveries and observations.

The research cycle flows from observations with medical relevance to the patient’s bedside and back to the lab. Progress in cancer research depends on the participation of basic and population scientists, physician-scientists, and clinical cancer researchers, as well as patients, their caregivers, and health care providers. Insights from one discipline influence others, and discoveries made in one cancer can offer new ideas to better address others.

Categories of Cancer Research

Cancer research can be divided into several broad categories:

Basic Research

Basic research is the study of animals, cells, molecules, or genes to gain new knowledge about cellular and molecular changes that occur naturally or during the development of a disease. Basic research is also referred to as lab research or preclinical research.

Translational Research

Translational research seeks to accelerate the application of discoveries in the laboratory to clinical practice. This is often referred to as moving advances from bench to bedside.

Clinical Research

Clinical research involves the application of treatments and procedures in patients. Clinical cancer researchers conduct clinical trials, study a particular patient or group of patients, including their behaviors, or use materials from humans, such as blood or tissue samples, to learn about disease, how the healthy body works, or how it responds to treatment.

Population Research

Population research (also known as epidemiological research) is the study of causes and patterns of occurrence of cancer and evaluation of risk. Population scientists, also known as epidemiologists, study the patterns, causes, and effects of health and diseases in defined groups. Population research is highly collaborative and can span the spectrum from basic to clinical research.

We have made spectacular progress against cancer thanks to breakthroughs in cancer science. However, with more than 600,000 people in the United States projected to die from cancer this year, our work is not done. Get involved to ensure that the momentum continues:

- The Progression of Cancer

- Experts Forecast Cancer Research and Treatment...

- Open access

- Published: 11 October 2019

Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: a growing clinical and research priority

- Claire L. Niedzwiedz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6133-4168 1 ,

- Lee Knifton 2 , 3 ,

- Kathryn A. Robb 1 ,

- Srinivasa Vittal Katikireddi 4 &

- Daniel J. Smith 1

BMC Cancer volume 19 , Article number: 943 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

90k Accesses

352 Citations

44 Altmetric

Metrics details

A cancer diagnosis can have a substantial impact on mental health and wellbeing. Depression and anxiety may hinder cancer treatment and recovery, as well as quality of life and survival. We argue that more research is needed to prevent and treat co-morbid depression and anxiety among people with cancer and that it requires greater clinical priority. For background and to support our argument, we synthesise existing systematic reviews relating to cancer and common mental disorders, focusing on depression and anxiety.

We searched several electronic databases for relevant reviews on cancer, depression and anxiety from 2012 to 2019. Several areas are covered: factors that may contribute to the development of common mental disorders among people with cancer; the prevalence of depression and anxiety; and potential care and treatment options. We also make several recommendations for future research. Numerous individual, psychological, social and contextual factors potentially contribute to the development of depression and anxiety among people with cancer, as well as characteristics related to the cancer and treatment received. Compared to the general population, the prevalence of depression and anxiety is often found to be higher among people with cancer, but estimates vary due to several factors, such as the treatment setting, type of cancer and time since diagnosis. Overall, there are a lack of high-quality studies into the mental health of people with cancer following treatment and among long-term survivors, particularly for the less prevalent cancer types and younger people. Studies that focus on prevention are minimal and research covering low- and middle-income populations is limited.

Research is urgently needed into the possible impacts of long-term and late effects of cancer treatment on mental health and how these may be prevented, as increasing numbers of people live with and beyond cancer.

Peer Review reports

A cancer diagnosis can have a wide-ranging impact on mental health and the prevalence of depression and anxiety among people with cancer is high [ 1 , 2 ]. Among those with no previous psychiatric history, a diagnosis of cancer is associated with heightened risk of common mental disorders, which may adversely affect cancer treatment and recovery, as well as quality of life and survival [ 3 ]. People who have previously used psychiatric services may be particularly vulnerable and at greater risk of mortality following a cancer diagnosis [ 4 ]. However, the mental health needs of people with cancer, with or without a prior psychiatric history, are often given little attention during and after cancer treatment, which is primarily focused on monitoring physical health symptoms and side effects. Advances in the earlier detection of cancer and improved cancer treatments means that people are now living longer with cancer, presenting a significant global challenge. The total number of people who are alive within 5 years of a cancer diagnosis was estimated to be 43.8 million in 2018 for 36 cancers across 185 countries [ 5 ], and in the United States alone, the number of cancer survivors is projected to rise exponentially from 15.5 million in 2016 to 26.1 million in 2040 [ 6 ].

The main objective of this article is to argue that more research is needed into the prevention, care and treatment of co-morbid depression and anxiety among people with cancer and highlight it as a growing clinical and policy priority. For background and to support our argument, we provide a current evidence review of systematic reviews relating to common mental disorders amongst people living with and beyond cancer. We cover the factors that may increase the risk of experiencing co-morbid depression and anxiety, epidemiology, and potential care and treatment options.

We searched three key electronic databases: Medline, PsycINFO and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) for relevant reviews (favouring those using systematic methods) using the following search terms: (neoplasm OR carcinoma OR tumo*r OR cancer) AND (depression OR anxiety) AND review. Only English language articles were considered and searches were limited to the years 2012 to 2017 and updated during February 2019. These years were considered adequate to capture the main themes relating to cancer and common mental disorders in the current literature. The references of highly relevant articles were scrutinised for additional papers and a Google search for important grey literature was also conducted. A minority of significant research articles known to the authors were also consulted.

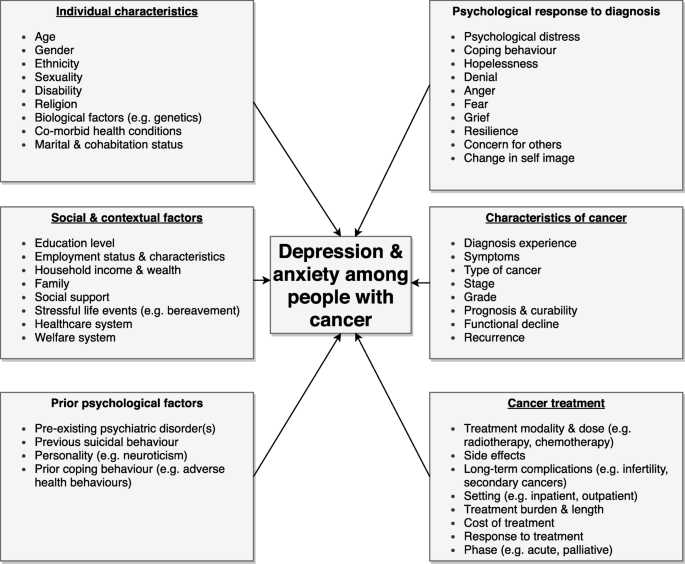

Factors influencing the development of depression and anxiety among people with cancer

A variety of factors are likely to interact to influence the development of depression and anxiety among people with cancer (summarised in Fig. 1 ), but these are not well understood [ 1 ], and require further research. Individual risk factors that may increase the risk of depression, similar to the general population, include demographic factors, such as age and gender, and social and economic factors such as unemployment, fewer educational qualifications and a lack of social support [ 7 ]. The development of depression and anxiety among people with cancer is also likely to depend on factors at the structural level, including healthcare costs and access, as well as access to welfare support, such as disability benefits, as cancer can have a significant financial impact [ 8 , 9 ]. Several psychological factors are also important. A key factor is the presence of pre-existing mental health problems and their severity. Research has demonstrated that individuals who have previously accessed mental health services before a cancer diagnosis experience excess mortality due to certain cancers, which may reflect late diagnosis, inadequate treatment and a higher rate of adverse health behaviours [ 4 , 10 ]. Personality factors, such as neuroticism, and existing coping skills may also contribute [ 11 ]. The risk of suicide among people with cancer is higher than the general population for certain diagnoses that tend to have poorer prognoses, such as mesothelioma and lung cancer, especially in the first 6 months after diagnosis [ 12 , 13 ]. Individuals who have previously engaged in suicidal behaviour are likely to be particularly vulnerable.

Factors that may contribute to depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer

The individual psychological response to a cancer diagnosis is also likely to be an important component. The experience of being diagnosed, particularly if the diagnosis has been delayed, can be a significant source of distress and can impact on illness acceptance [ 14 ]. Feelings of hopelessness, loss of control and uncertainty around survival and death can also have a detrimental impact, particularly in patients with a poor prognosis. Anxiety around a cancer diagnosis can also lead to sleep disturbance, which may increase the risk of depression [ 15 ]. The stigma surrounding both mental illness and certain types of cancer, such as lung cancer, can lead to feelings of guilt and shame, which could contribute to the onset of depression. For example, the link between smoking and lung cancer can lead to some patients blaming themselves for their illness and experiencing stigma if they have engaged in smoking [ 14 ].

A variety of factors related to the cancer and its treatment are likely to impact on the development of depression and anxiety, including the type of cancer, stage and prognosis. Cancer treatments including immunotherapy and chemotherapy may induce depression through particular biological mechanisms, such as inflammatory pathways, and some medications used to treat chemotherapy-induced nausea can reduce dopaminergic transmission, which is implicated in the development of depressive symptoms [ 16 ]. The use of steroids in cancer treatment can induce depression [ 17 ], and androgen deprivation therapy in the treatment of prostate cancer is also associated with increased risk [ 18 ]. The physical symptoms of specific cancers can also contribute to depression (e.g. incontinence and sexual dysfunction associated with prostate cancer) [ 19 ]. Iatrogenic distress is also commonly reported amongst patients, which could increase the risk of experiencing later problems with depression and anxiety, including post-traumatic stress disorder [ 20 ]. This is often related to a combination of poor communication, a lack of consideration of psychological concerns and disjointed care [ 14 , 20 ].

Prevalence of depression and anxiety among people with cancer

The prevalence of common mental disorders among people with cancer varies widely in the published literature. The mean prevalence of depression using diagnostic interviews is around 13% and using all assessment methods it varies from approximately 4 to 49% [ 2 , 21 ]. This wide variation is due to several factors including the treatment setting, type of cancer included and method used to screen for symptoms (e.g. interview by trained psychiatrist or self-report instrument). The estimated prevalence of depression was found to be 3% in patients with lung cancer, compared to 31% in patients with cancer of the digestive tract, when diagnostic interviews were used [ 21 ]. A meta-analyses of 15 studies meeting a number of quality criteria, including the use of diagnostic interviews, found that the estimated prevalence of depression varied across treatment settings (5 to 16% in outpatients, 4 to 14% in inpatients, 4 to 11% in mixed outpatient and inpatient samples, and 7 to 49% in palliative care) [ 2 ]. There is no universal standardised tool which is recommended for depression screening in patients with cancer and the method used is likely to differ depending on the treatment setting. A meta-analysis of screening and case finding tools for depression in cancer settings identified 63 studies that used 19 different screening tools for depression [ 22 ]. Common screening methods for depression include semi-structured diagnostic interviews, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale - depression subscale (HADS-D) and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD), which are designed to measure the severity of depressive symptoms.

An important aspect that needs to be considered is the timing of increased psychiatric risk. Studies demonstrate that depression tends to be highest during the acute phase and decreases following treatment, but again this likely differs depending on the type of cancer and prognosis [ 21 ]. Using diagnostic interviews, the prevalence of depression during treatment was found to be 14%, 9% in the first year after diagnosis and 8% a year or more after treatment in a meta-analysis of 211 studies [ 21 ]. Of the 238 cohorts included, around 30% included only breast cancer patients and there is a need for research including rarer types of cancer.

As well as the type of cancer, the type of mental health outcome considered is also important and fewer studies have examined anxiety. A systematic review and meta-analysis study focusing on patients with ovarian cancer found that anxiety tended to be higher following treatment (27%) and during treatment (26%), and was lowest pre-treatment (19%) [ 23 ]. The heightened anxiety observed post-treatment may be due to reduced clinical consultations and support following treatment, potential transfer to a palliative setting, and fear of recurrence. Fear of recurrence is one of the most commonly reported issues and an important area of unmet need for cancer survivors [ 24 ]. A lack of outward physical symptoms in ovarian cancer also means that self-monitoring is difficult [ 23 ]. In the same study of ovarian cancer patients, depression was highest before treatment (25%) and during treatment (23%), and reduced following treatment (13%). This is in the context of a lifetime prevalence for clinical depression and anxiety of around 10 and 8%, respectively, amongst women in the UK [ 23 , 25 ].

A similar systematic review of depression and anxiety among patients with prostate cancer found that anxiety tended to be highest pre-treatment (27%) and lowered during treatment (15%) and post-treatment (18%) [ 26 ]. Rates of depression were relatively similar following treatment (18%), during treatment (15%) and pre-treatment (17%), with the 95% confidence intervals for these estimates largely overlapping. For reference, the prevalence of clinical depression and anxiety in men aged over 65 years is less than 9 and 6%, respectively [ 26 ]. A systematic review on the prevalence of psychological distress among testicular cancer survivors demonstrated that around one in five experienced clinically significant anxiety, compared to one in eight among general population controls, with fear of recurrence again being one of the key issues reported [ 27 ]. However, depression was no more prevalent amongst those surviving testicular cancer compared to the general population. In Scotland, the prevalence of depression was found to be highest in patients with lung cancer (13%), followed by gynaecological cancer (11%), breast cancer (9%), colorectal cancer (7%), and genitourinary cancer (6%) [ 28 ]. The authors found depression to be more likely among younger and more socially disadvantaged individuals. In addition, 73% of the patients with depression were not receiving treatment for their mental health. Further research is needed to ascertain the factors which contribute to the uptake and efficacy of treatment for depression. This study also only considered people with cancer who had attended specialist cancer clinics within a defined time period, which likely excluded people who were diagnosed many years ago.

The longer-term psychological impact of cancer has received comparatively little research. The few studies in this area have mainly focused on women with breast cancer and demonstrate that depressive symptoms can persist for over 5 years after diagnosis, though the prevalence of anxiety was not elevated compared to the general population [ 29 ]. A systematic review of the prevalence of depression and anxiety among long-term cancer survivors, including all types, found that anxiety was more prevalent among cancer survivors, compared to healthy controls [ 30 ]. Few studies have focused specifically on younger cancer survivors and more research is needed in this area. A representative study of young adult cancer survivors aged 15 to 39 years in the United States demonstrated that moderate (23% vs 17%) and severe (8% vs 3%) mental distress were significantly higher in those living with cancer for at least 5 years after diagnosis, compared to controls [ 31 ]. 75 and 52% of people with cancer with moderate and severe distress, respectively, had not talked to a mental health professional, with the cost of treatment a potential barrier. Limitations of this study included the focus on self-reported mental distress and not clinical depression or anxiety, as well as the relatively small sample size.

Many studies in this area have a poor response rate, lack representativeness, are based on a small sample of patients (often with the most common types of cancer), which often exclude those with cognitive impairment and patients who are too physically or mentally unwell to take part [ 32 ]. Future studies would benefit from using administrative health data [ 33 ], for example, linking together cancer registries, inpatient and outpatient records and prescribing data. There are also a lack of studies covering populations from low- and middle-income countries [ 34 ]. The estimated prevalence of comorbid common mental disorders is likely to vary depending on the country studied, due to factors such as the health and welfare system. These factors may influence mental health inequalities among people with cancer, which has received little research focus. In a Scottish study, depression was found to be higher in the least advantaged groups (19%), compared to the most advantaged (10%) [ 35 ]. Cancer and comorbid anxiety was also unequally distributed; in the least advantaged groups around 12% had both conditions, compared to 7% among the most advantaged [ 35 ]. Further research is needed in this area to quantify, monitor and prevent inequalities among people with cancer.

It should also be highlighted that the psychological impact of cancer may not always be negative and many people will not experience problems with depression and anxiety. Experiencing temporary distress related to a cancer diagnosis may lead to positive psychological changes in the long-term whereby individuals feel a greater appreciation of life and are able to re-evaluate their priorities [ 36 ]. The factors that protect against the development of common mental disorders and contribute to positive mental health among people living with and beyond cancer merits further research.

Treatment and management of depression and anxiety among people with cancer

To effectively manage and treat depression and anxiety among people with cancer, symptoms must first be identified. However, several social and clinical barriers have been reported. A key issue is the lack of physician time for assessing symptoms. There can also be a normalisation of distress and attribution of the somatic symptoms of depression and anxiety to the cancer. Patients may not disclose psychiatric symptoms because of the stigma surrounding mental health conditions [ 37 ]. Screening for depression and anxiety among patients with cancer is also only of value if it leads to effective treatment and support that is able to improve patient outcomes. Patients may be more reluctant to discuss their mental health needs if they perceive a lack of effective treatment options.

The existing evidence for treating anxiety and depression among patients with cancer is limited and of varying quality [ 38 ]. Studies with small sample sizes are common; this mitigates against the detection of meaningful changes in patient outcomes and these studies often suffer from a high rate of attrition, which likely reflects the high symptom burden and reduced survival in this patient population [ 39 ]. Systematic reviews demonstrate there is a preponderance of studies from the United States, which include a high number of studies focusing on female patients with breast cancer [ 40 ]. However, these studies demonstrate that psychotherapy, psychoeducation and relaxation training may have small to medium short-term effects on relieving emotional distress and reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression, as well as improving health-related quality of life. The evidence for pharmacological treatment of depression with antidepressants is mixed - there are very few studies in this area and those that exist are of low quality [ 41 ]. There is also concern around potential side effects of antidepressants and drug interactions that may affect the efficacy of cancer treatments [ 42 ].

A systematic review and meta-analysis focusing on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) found that it may be effective in reducing depression and anxiety and improving quality of life in patients with cancer in the short-term, but potential long-term effects were only sustained for quality of life [ 43 ]. However, in this meta-analysis the included participants were primarily women with breast cancer and there are a lack of studies covering other cancer types. It is likely that collaborative care interventions which involve partnership between psychiatry, clinical psychology and primary care, overseen by a care manager are likely to be most effective in the management and treatment of depression amongst people with cancer [ 44 ]. Treatment should be based on patient preference and also take into account potential adverse side effects [ 44 ]. In a UK-based study it was found that only a third of patients with cancer and related psychological or emotional distress were willing to be referred for support [ 45 ]. Qualitative studies also demonstrate that patients often do not want to discuss their feelings with nurses during cancer treatment [ 46 ]. However, patients valued having the option to talk about their emotions, but they preferred to choose with whom and when. There is therefore a need for further research into some of the barriers to obtaining mental health support among those affected by cancer and experiencing distress to prevent future problems.

The self-management of psychological distress among people with cancer may be beneficial and could help prevent distress becoming clinical depression or anxiety. Self-management can be defined as: “The individual’s ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a chronic condition. Efficacious self-management encompasses the ability to monitor one’s condition and to affect the cognitive, behavioural and emotional responses necessary to maintain a satisfactory quality of life. Thus, a dynamic and continuous process of self-regulation is established.” [ 47 ] . Studies on self-management, cancer and psychological distress have focused on the treatment phase, with fewer investigating interventions following treatment or at the end of life [ 48 ]. There is evidence to suggest that self-management of psychological distress in cancer can help to empower patients and families to care for themselves in a way which is preferable for them. Self-management interventions that have shown promise include education, monitoring, teaching and counselling to help patients manage the short- and long-term physical and psychosocial effects of cancer [ 48 ]. However, a recent systematic review examining the impact of self-management interventions on outcomes including quality of life, self-efficacy and symptom management (such as psychological distress) amongst cancer survivors demonstrated a lack of evidence to support any specific intervention and found that the six included interventions lacked sustainability, bringing into question their long-term effectiveness and value for money [ 49 ]. Again, the included studies were dominated by women with breast cancer, with only two covering other cancers.

Effective treatment and management strategies may also differ according to the demographic group affected. In a report by CLIC (Cancer and Leukaemia in Childhood) Sargent which surveyed 146 young people with cancer, keeping in touch with friends and family, talking to others with similar experiences and access to the internet in hospital were reported to help maintain mental health during cancer treatment [ 50 ]. Of the young people who mentioned they would find it helpful to talk to other people with similar experiences, 60% said they would prefer to do this online. Young people also reported that the available services were not tailored to deal with those aged under 18 or the emotional impact of cancer. In addition, those who accessed services mentioned that there is a lack of suitable long-term emotional support. Just over 40% of the young people who took part did not access support for their mental health needs.

It is clear that a more personalised approach to supporting the psychological health of people with cancer is needed [ 51 ]. Some people may not want or require support or treatment, others will be able to self-manage, and some may have more complex needs that require more intensive follow-up and support. At diagnosis, the psychological health of patients should be considered alongside their physical health and sources of support offered. Needs and symptoms may also change over time. Evaluation of more recent personalised approaches to follow-up care that have been adopted in several areas including England and Northern Ireland [ 51 ] are needed to understand the role they may have in preventing longer term depression and anxiety amongst cancer survivors.

A key barrier affecting research progress in this area is funding [ 52 ]. In the UK, money spent on research into the biology of cancer was more than five times than that spent on ‘Cancer Control, Survivorship and Outcomes’ during 2017/18 [ 53 ]. Research into the mental health and wellbeing of people living with and beyond cancer is likely to only be a small part of this. Research is urgently needed in this area as more people survive cancer and for some cancers, such as multiple myeloma and colorectal cancer, risk is increasing in younger cohorts [ 54 ]. The long-term (those that begin during treatment and continue afterwards) and late effects of cancer treatment (those that begin after treatment is completed), such as secondary cancers, infertility, chronic pain and insomnia, are likely to affect the mental wellbeing of cancer survivors, potentially contributing to depression and anxiety [ 6 ]. The National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) in the UK have also recently highlighted research into the short-term and long-term psychological impacts of cancer and its treatment as a key priority, following surveys of over 3500 patients, carers, and health and social care professionals [ 55 ].

The mental health of people living with and beyond cancer in its various types and stages is an important and growing research and clinical priority. Compared to the general population, the prevalence of anxiety and depression is often higher among people with cancer, but estimates vary due to a number of factors, such as the type and stage of cancer. Patients often do not obtain psychological support or treatment. This is likely due to several factors, including lack of awareness and identification of psychiatric symptoms, an absence of support available or offered, lack of evidence around effective treatments, stigma, and patient preference. In particular, we highlight the lack of high-quality research into the mental health of long-term cancer survivors, the potential impact of long-term and late effects of cancer treatment, and the few studies focused on prevention. Further research that includes the less common types of cancer is required, as well as the inclusion of younger people and populations from low- and middle-income countries. Given the increasing numbers of people living with and beyond cancer, this research is of timely importance.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

Cognitive behavioural therapy

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

Cancer and Leukaemia in Childhood

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale - depression subscale

National Cancer Research Institute

Pitman A, Suleman S, Hyde N, Hodgkiss A. Depression and anxiety in patients with cancer. BMJ. 2018;361:k1415.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Walker J, Hansen CH, Martin P, Sawhney A, Thekkumpurath P, Beale C, Symeonides S, Wall L, Murray G, Sharpe M. Prevalence of depression in adults with cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(4):895–900.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Zhu J, Fang F, Sjölander A, Fall K, Adami HO, Valdimarsdóttir U. First-onset mental disorders after cancer diagnosis and cancer-specific mortality: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(8):1964–9.

Klaassen Z, Wallis CJD, Goldberg H, Chandrasekar T, Sayyid RK, Williams SB, Moses KA, Terris MK, Nam RK, Urbach D, et al. The impact of psychiatric utilisation prior to cancer diagnosis on survival of solid organ malignancies. Br J Cancer. 2019;120:840–7.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

Shapiro CL. Cancer survivorship. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(25):2438–50.

Wen S, Xiao H, Yang Y. The risk factors for depression in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(1):57–67.

Gilligan AM, Alberts DS, Roe DJ, Skrepnek GH. Death or Debt? National Estimates of Financial Toxicity in Persons with Newly-Diagnosed Cancer. Am J Med. 2018;131(10):1187–99 e1185.

Lu L, O'Sullivan E, Sharp L. Cancer-related financial hardship among head and neck cancer survivors: Risk factors and associations with health-related quality of life. Psycho-Oncology. 2019;28(4):863–71.

Musuuza JS, Sherman ME, Knudsen KJ, Sweeney HA, Tyler CV, Koroukian SM. Analyzing excess mortality from cancer among individuals with mental illness. Cancer. 2013;119(13):2469–76.

Cook SA, Salmon P, Hayes G, Byrne A, Fisher PL. Predictors of emotional distress a year or more after diagnosis of cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Psycho-oncology. 2018;27(3):791–801.

Henson KE, Brock R, Charnock J, Wickramasinghe B, Will O, Pitman A. Risk of suicide after cancer diagnosis in England. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(1):51–60.

Wang SM, Chang JC, Weng SC, Yeh MK, Lee CS. Risk of suicide within 1 year of cancer diagnosis. Int J Cancer. 2018;142(10):1986–93.

Ball H, Moore S, Leary A. A systematic literature review comparing the psychological care needs of patients with mesothelioma and advanced lung cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;25:62–7.

Howell D, Harris C, Aubin M, Olson K, Sussman J, MacFarlane J, Taylor C, Oliver TK, Keller-Olaman S, Davidson JR, et al. Sleep disturbance in adults with cancer: a systematic review of evidence for best practices in assessment and management for clinical practice. Ann Oncol. 2013;25(4):791–800.

Smith HR. Depression in cancer patients: pathogenesis, implications and treatment (review). Oncol Lett. 2015;9(4):1509–14.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ismail MF, Lavelle C, Cassidy EM. Steroid-induced mental disorders in cancer patients: a systematic review. Future Oncol. 2017;13(29):2719–31.

Nead KT, Sinha S, Yang DD, Nguyen PL. Association of androgen deprivation therapy and depression in the treatment of prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Urologic Oncol. 2017;35(11):664 e661–664.e669.

CAS Google Scholar

De Sousa A, Sonavane S, Mehta J. Psychological aspects of prostate cancer: a clinical review. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012;15(2):120–7.

Cordova MJ, Riba MB, Spiegel D. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cancer. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(4):330–8.

Krebber AMH, Buffart LM, Kleijn G, Riepma IC, de Bree R, Leemans CR, Becker A, Brug J, van Straten A, Cuijpers P, et al. Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: a meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psycho-Oncology. 2014;23(2):121–30.

Mitchell AJ, Meader N, Davies E, Clover K, Carter GL, Loscalzo MJ, Linden W, Grassi L, Johansen C, Carlson LE, et al. Meta-analysis of screening and case finding tools for depression in cancer: evidence based recommendations for clinical practice on behalf of the depression in Cancer care consensus group. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(2):149–60.

Watts S, Prescott P, Mason J, McLeod N, Lewith G. Depression and anxiety in ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence rates. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11):e007618.

Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, Dixon M, Hayden C, Mireskandari S, Ozakinci G. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):300–22.

Halliwell E, Main L, Richardson C. The fundamental facts: the latest facts and figures on mental health: mental Health Foundation; 2007.

Google Scholar

Watts S, Leydon G, Birch B, Prescott P, Lai L, Eardley S, Lewith G. Depression and anxiety in prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence rates. BMJ Open. 2014;4(3):e003901.

Smith AB, Rutherford C, Butow P, Olver I, Luckett T, Grimison P, Toner G, Stockler M, King M. A systematic review of quantitative observational studies investigating psychological distress in testicular cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2018;27(4):1129–37.

Walker J, Hansen CH, Martin P, Symeonides S, Ramessur R, Murray G, Sharpe M. Prevalence, associations, and adequacy of treatment of major depression in patients with cancer: a cross-sectional analysis of routinely collected clinical data. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(5):343–50.

Maass SW, Roorda C, Berendsen AJ, Verhaak PF, de Bock GH. The prevalence of long-term symptoms of depression and anxiety after breast cancer treatment: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2015;82(1):100–8.

Mitchell AJ, Ferguson DW, Gill J, Paul J, Symonds P. Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouses and healthy controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(8):721–32.

Kaul S, Avila JC, Mutambudzi M, Russell H, Kirchhoff AC, Schwartz CL. Mental distress and health care use among survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer: a cross-sectional analysis of the National Health Interview Survey. Cancer. 2017;123(5):869–78.

Ryan D, Gallagher P, Wright S, Cassidy E. Methodological challenges in researching psychological distress and psychiatric morbidity among patients with advanced cancer: what does the literature (not) tell us? Palliat Med. 2012;26(2):162–77.

Lu L, Deane J, Sharp L. Understanding survivors’ needs and outcomes: the role of routinely collected data. Curr Opinion Supportive Palliative Care. 2018;12(3):254–60.

Article Google Scholar

Walker ZJ, Jones MP, Ravindran AV. Psychiatric disorders among people with cancer in low- and lower-middle-income countries: study protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e017043.

Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37–43.

Casellas-Grau A, Ochoa C, Ruini C. Psychological and clinical correlates of posttraumatic growth in cancer: a systematic and critical review. Psycho-Oncology. 2017;26(12):2007–18.

Kissane DW. Unrecognised and untreated depression in cancer care. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(5):320–1.

Rodin G, Lloyd N, Katz M, Green E, Mackay JA, Wong RK. Supportive care guidelines Group of Cancer Care Ontario Program in evidence-based care: the treatment of depression in cancer patients: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(2):123–36.

Hui D, Glitza I, Chisholm G, Yennu S, Bruera E. Attrition rates, reasons, and predictive factors in supportive care and palliative oncology clinical trials. Cancer. 2013;119(5):1098–105.

Faller H, Schuler M, Richard M, Heckl U, Weis J, Küffner R. Effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(6):782–93.

Ostuzzi G, Matcham F, Dauchy S, Barbui C, Hotopf M. Antidepressants for the treatment of depression in people with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4(4):CD011006.

Ostuzzi G, Benda L, Costa E, Barbui C. Efficacy and acceptability of antidepressants on the continuum of depressive experiences in patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41(8):714–24.

Osborn RL, Demoncada AC, Feuerstein M. Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer survivors: meta-analyses. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36(1):13–34.

Li M, Kennedy EB, Byrne N, Gérin-Lajoie C, Katz MR, Keshavarz H, Sellick S, Green E. Systematic review and meta-analysis of collaborative care interventions for depression in patients with cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2017;26(5):573–87.

Baker-Glenn EA, Park B, Granger L, Symonds P, Mitchell AJ. Desire for psychological support in cancer patients with depression or distress: validation of a simple help question. Psycho-Oncol. 2011;20(5):525–31.

Kvåle K. Do cancer patients always want to talk about difficult emotions? A qualitative study of cancer inpatients communication needs. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11(4):320–7.

Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, Hainsworth J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(2):177–87.

McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, Schulman-Green D, Schilling LS, Lorig K, Wagner EH. Self-management: enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(1):50–62.

Boland L, Bennett K, Connolly D. Self-management interventions for cancer survivors: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(5):1585–95.

PubMed Google Scholar

Sargent CLIC. Hidden costs: the mental health impact of a cancer diagnosis on young people; 2017.

Alfano CM, Mayer DK, Bhatia S, Maher J, Scott JM, Nekhlyudov L, Merrill JK, Henderson TO. Implementing personalized pathways for cancer follow-up care in the United States: proceedings from an American Cancer Society–American Society of Clinical Oncology summit. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(3):234–47.

Foster C, Calman L, Richardson A, Pimperton H, Nash R. Improving the lives of people living with and beyond cancer: generating the evidence needed to inform policy and practice. J Cancer Policy. 2018;15:92–5.

National Cancer Research Institute. Spend by Research Category and Disease Site. [ https://www.ncri.org.uk/ncri-cancer-research-database-old/spend-by-research-category-and-disease-site/ ]. Accessed 27 June 2019.

Sung H, Siegel RL, Rosenberg PS, Jemal A. Emerging cancer trends among young adults in the USA: analysis of a population-based cancer registry. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(3):e137–47.

National Cancer Research Institute. The UK Top living with and beyond cancer research priorities. [ https://www.ncri.org.uk/lwbc/#lwbc_questions ]. Accessed 27 June 2019.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This article is built on a literature review conducted by CLN and LK for a project on ‘Supporting the mental and emotional health of people with cancer’ funded by the Big Lottery Fund when CLN was an employee of the Mental Health Foundation in Scotland during 2017.

CLN is currently supported by the Medical Research Council (grant number MR/R024774/1). SVK is funded by a NHS Research Scotland (NRS) Senior Clinical Fellowship (SCAF/15/02), the Medical Research Council (MC_UU_12017/13 & MC_UU_12017/15) and Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office (SPHSU13 & SPHSU15). The funders had no role in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; the writing of the article; and in the decision to submit it for publication.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland, UK

Claire L. Niedzwiedz, Kathryn A. Robb & Daniel J. Smith

University of Strathclyde, Centre for Health Policy, Glasgow, Scotland, UK

Lee Knifton

Mental Health Foundation, Glasgow, Scotland, UK

MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland, UK

Srinivasa Vittal Katikireddi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

CLN and LK conceived the article. CLN conducted the searches and drafted the manuscript. CLN, LK, SVK, KAR and DJS interpreted the findings. All authors critically revised the manuscript, read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Claire L. Niedzwiedz .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests except for the funding acknowledged.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Niedzwiedz, C.L., Knifton, L., Robb, K.A. et al. Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: a growing clinical and research priority. BMC Cancer 19 , 943 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6181-4

Download citation

Received : 19 March 2019

Accepted : 20 September 2019

Published : 11 October 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6181-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

- Multimorbidity

- Survivorship

ISSN: 1471-2407

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 19 April 2022

Focus Issue: The Future Of Cancer Research

Nature Medicine volume 28 , page 601 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

6 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

New treatments and technologies offer exciting prospects for cancer research and care, but their global impact rests on widespread implementation and accessibility.

Cancer care has advanced at an impressive pace in recent years. New insights into tumor immunology and biology, combined with advances in artificial intelligence, nano tools, genetic engineering and sequencing — to name but a few — promise ever-more-powerful capabilities in the prevention, diagnosis and personalized treatment of cancer. How do we harness and build on these advances? How do we make them work in different global settings? In this issue, we present a Focus dedicated to the future of cancer research, in which we take stock of progress and explore ways to deliver research and care that is innovative, sustainable and patient focused.

This year brought news that two of the first patients with leukemia to receive chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell treatment remain in remission more than a decade later . Writing in this issue, Carl June — who helped to treat these first patients — and colleagues reflect on how early transplant medicine laid a solid foundation for CAR T cell development in blood cancers, and how this is now paving the way for the use of engineered cell therapies in solid cancers. In a noteworthy step toward this goal, Haas and colleagues present results of a phase 1 trial of CAR T cells in metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer — a disease that has seen relatively few new treatment options in recent years.

Up to now, CAR T cells have been used only in the context of relapsed or refractory hematological malignancies, but in this issue, Neelapu et al . present phase 2 study data that suggest CAR T cell therapy could be beneficial when used earlier in certain high-risk patients. In addition, prospective data from van den Brink et al . support a role for the gut microbiome composition in CAR T cell therapy outcomes, highlighting new avenues of research to help maximize therapeutic benefit.

Although the idea that the gut microbiome influences CAR T cell therapy outcomes may be relatively new, it has been known for some time that it has a role in the response to checkpoint-inhibitor immunotherapy. A plethora of microbe-targeting therapies are now under investigation for cancer treatment; in this issue, Pal and colleagues describe one such strategy — whereby the combination of a defined microbial supplement with checkpoint blockade led to improved responses in patients with advanced kidney cancer. In their Review, Jennifer Wargo and colleagues take stock of the latest research in this field, and predict that microbial targeting could become a pillar of personalized cancer care over the next decade.

The theme for this year’s World Cancer Day was ‘Close the care gap’ — a message that is woven through several pieces in this issue. Early detection strategies have enormous potential to make a difference in this area; reviewing the latest advances, Rebecca Fitzgerald and colleagues ask who should be tested, and how — and outline their vision for personalized, risk-based screening, keeping in mind practicality and clinical implementation. Journalist Carrie Arnold reports on an emerging strategy known as ‘theranostics’ that aims to both diagnose and treat cancers in a unified approach, highlighting the growing commercial interest in this field. Of course, commercial interest does not equate to widespread availability or equal access to new therapies, and increasingly sophisticated technologies — although beneficial for some — can serve to widen existing inequalities.

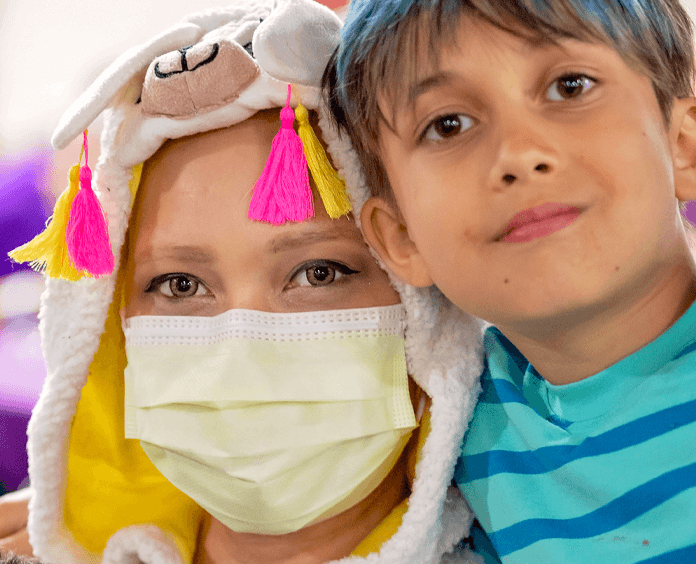

Pediatric cancers lag far behind adult cancers in terms of drug development and approval. Nancy Goodman, a patient advocate whose son died from a childhood cancer, argues that market failures are largely to blame for the gap — but that legislative changes can correct this. Although in some cases there is a strong mechanistic rationale for testing promising adult cancer therapies or combinations in children, translational research is also needed to identify new therapeutic targets — such as the approach taken by Behjati and colleagues , which sheds new light on the molecular characteristics of an aggressive form of infant leukemia.

Meanwhile, for adult cancers, countless new therapeutic modalities are on the horizon , and drug approvals based on genomic biomarkers have accelerated in recent years. Unfortunately, their implementation into routine clinical care is progressing at a much slower pace. In their Perspective, Emile Voest and colleagues point out that bridging this gap will require investment in health infrastructure, as well as in education and decision-support tools, among other things.

Perhaps the most striking gap is that between high-income countries and low- and middle-income countries, not only in terms of cancer survival outcomes but also in terms of resources and infrastructure for impactful research. In their Perspective, CS Pramesh and colleagues outline their top priorities for cancer research in low- and middle-income countries, arguing that cancer research must be regionally relevant and geared toward reducing the number of patients diagnosed with advanced disease. Practicality is key — a sentiment echoed by Bishal Gyawali and Christopher Booth, who call for a “ common sense revolution ” in oncology, and regulatory policies and trial designs that serve patients better.

To realize this goal, clinical trial endpoints and outcome measures should be designed to minimize the burden on patients and maximize the potential for improving on the standard of care. This should go beyond survival outcomes; systemic effects, including cachexia and pain, have a major impact on quality of life and mental health during and after treatment. Two articles in this issue highlight the enormous psychological burden associated with a cancer diagnosis; increased risks of depression, self-harm and suicide emphasize the need for psychosocial interventions and a holistic approach to treatment.

As noted by members of the Bloomberg New Economy International Cancer Coalition in their Comment , the widespread adoption of telemedicine and remote monitoring in response to the COVID-19 pandemic could, if retained, help to make cancer trials more patient centered. Therefore, as health systems and research infrastructures adapt to the ongoing pandemic, there exists an unprecedented opportunity to reshape the landscape of cancer research.

We at Nature Medicine are committed to helping shape this transformation. We are issuing a call for research papers that utilize innovative approaches to address current challenges in cancer prevention, detection, diagnosis and treatment — both clinical trials and population-based studies with global implications. Readers can find more information about publishing clinical research in Nature Medicine at https://www.nature.com/nm/clinicalresearch .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Focus Issue: The Future Of Cancer Research. Nat Med 28 , 601 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01809-z

Download citation

Published : 19 April 2022

Issue Date : April 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01809-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

This experimental drug could change the field of cancer research

Sacha Pfeiffer

Jonaki Mehta

The new treatment is categorized as immunotherapy. skaman306/Getty Images hide caption

The new treatment is categorized as immunotherapy.

A tiny group of people with rectal cancer just experienced something of a scientific miracle: their cancer simply vanished after an experimental treatment.

In a very small trial done by doctors at New York's Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, patients took a drug called dostarlimab for six months. The trial resulted in every single one of their tumors disappearing. The trial group included just 18 people, and there's still more to be learned about how the treatment worked. But some scientists say these kinds of results have never been seen in the history of cancer research.

Dr. Hanna Sanoff of the University of North Carolina's Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center joined NPR's All Things Considered to outline how this drug works and what it could mean for the future of cancer research. Although she was not involved with the study, Dr. Sanoff has written about the results.

This interview has been lightly edited

On her first reaction to the results: I mean, I am incredibly optimistic. Like you said in the introduction, we have never seen anything work in 100 percent of people in cancer medicine.

On how the drug works to treat cancer: This drug is one of a class of drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors. These are immunotherapy medicines that work not by directly attacking the cancer itself, but actually getting a person's immune system to essentially do the work. These are drugs that have been around in melanoma and other cancers for quite a while, but really have not been part of the routine care of colorectal cancers until fairly recently.

On the kinds of side effects patients experienced: Very, very few in this study - in fact, surprisingly few. Most people had no severe adverse effects at all.

On how this study could be seen as 'practice-changing': Our hope would be that for this subgroup of people - which is only about five percent to 10 percent of people who have rectal cancer - if they can go on and just get six months of immunotherapy and not have any of the rest of this - I don't even know the word to use. Paradigm shift is often used, but this really absolutely is paradigm-shifting.

On why the idea of being able to skip surgery for cancer treatment is so revolutionary: In rectal cancer, this is part of the conversation we have with someone when they're diagnosed. We are very hopeful for being able to cure you, but unfortunately, we know our treatments are going to leave you with consequences that may, in fact, be life-changing. I have had patients who, after their rectal cancer, have barely left the house for years - and in a couple of cases, even decades - because of the consequences of incontinence and the shame that's associated with this.

On next steps for the drug: What I'd really like us to do is get a bigger trial where this drug is used in a much more diverse setting to understand what the real, true response rate is going to be. It's not going to end up being 100 percent. I hope I bite my tongue on that in the future, but I can't imagine it will be 100 percent. And so when we see what the true response rate is, that's when I think we can really do this all the time.

This piece was reported by Sacha Pfeiffer, produced by Jonaki Mehta and edited by Kathryn Fox. It was adapted for the web by Manuela Lopez Restrepo.

- cancer treatment

Cancer patients often do better with less intensive treatment, research shows

Scaling back treatment for three kinds of cancer can make life easier for patients without compromising outcomes, doctors reported at the world’s largest cancer conference .

It’s part of a long-term trend toward studying whether doing less — less surgery, less chemotherapy or less radiation — can help patients live longer and feel better. The latest studies involved ovarian and esophageal cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma.

Thirty years ago, cancer research was about doing more, not less. In one sobering example, women with advanced breast cancer were pushed to the brink of death with massive doses of chemotherapy and bone marrow transplants. The approach didn’t work any better than chemotherapy and patients suffered.

Now, in a quest to optimize cancer care, researchers are asking: “Do we need all that treatment that we have used in the past?”

It’s a question, “that should be asked over and over again,” said Dr. Tatjana Kolevska, medical director for the Kaiser Permanente National Cancer Excellence Program, who was not involved in the new research.

Often, doing less works because of improved drugs.

“The good news is that cancer treatment is not only becoming more effective, it’s becoming easier to tolerate and associated with less short-term and long-term complications,” said Dr. William G. Nelson of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, who was also not involved in the new research.

Latest news on cancer treatment

- Cancer-fighting antibodies inject chemo directly into tumor cells, upping effectiveness.

- Long-term study shows 'remarkable' treatment helps patients with deadly nonsmoking-related lung cancer.

- FDA approves groundbreaking treatment for advanced melanoma.

Studies demonstrating the trend were discussed over the weekend at an American Society of Clinical Oncology conference in Chicago. Here are the highlights:

Ovarian cancer

French researchers found that it’s safe to avoid removing lymph nodes that appear healthy during surgery for advanced ovarian cancer. The study compared the results for 379 patients — half had their lymph nodes removed and half did not. After nine years, there was no difference in how long the patients lived and those with less-extreme surgery had fewer complications, such as the need for blood transfusions. The research was funded by the National Institute of Cancer in France.

Esophageal cancer

This German study looked at 438 people with a type of cancer of the esophagus that can be treated with surgery. Half received a common treatment plan that included chemotherapy and surgery on the esophagus, the tube that carries food from the throat to the stomach. Half got another approach that includes radiation too. Both techniques are considered standard. Which one patients get can depend on where they get treatment.

After three years, 57% of those who got chemo and surgery were alive, compared to 51% of those who got chemo, surgery and radiation. The German Research Foundation funded the study.

Hodgkin lymphoma

A comparison of two chemotherapy regimens for advanced Hodgkin lymphoma found the less intensive treatment was more effective for the blood cancer and caused fewer side effects.

After four years, the less harsh chemo kept the disease in check in 94% of people, compared to 91% of those who had the more intense treatment. The trial included 1,482 people in nine countries — Germany, Austria, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Australia and New Zealand — and was funded by Takeda Oncology, the maker of one of the drugs used in the gentler chemo that was studied.

The Associated Press

- Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer

- Bile Duct Cancer

- Bladder Cancer

- Brain Cancer

- Breast Cancer

- Cervical Cancer

- Childhood Cancer

- Colorectal Cancer

- Endometrial Cancer

- Esophageal Cancer

- Head and Neck Cancer

- Kidney Cancer

- Liver Cancer

- Lung Cancer

- Mouth Cancer

- Mesothelioma

- Multiple Myeloma

- Neuroendocrine Tumors

- Ovarian Cancer

- Pancreatic Cancer

- Prostate Cancer

- Skin Cancer/Melanoma

- Stomach Cancer

- Testicular Cancer

- Throat Cancer

- Thyroid Cancer

- Prevention and Screening

- Diagnosis and Treatment

- Research and Clinical Trials

- Survivorship

Request an appointment at Mayo Clinic

New research discovers a new combination of therapy for people with a type of leukemia, leading them to live longer

Share this:.

By Kelley Luckstein

In a new multicenter international study led by the Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center , researchers found that people with the B-cell precursor subtype of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL), who also lacked a genetic abnormality known as the Philadelphia chromosome and were in remission with no trace of cancer, showed significantly higher survival rates when blinatumomab was added to their chemotherapy treatment. The randomized study results are published this month in the New England Journal of Medicine.

"These results are encouraging and establish a new standard of treatment for people with BCP-ALL," says Mark Litzow, M.D. , lead study author and hematologist at the Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center. "The addition of blinatumomab to chemotherapy reduced the risk of leukemia recurrence and death by nearly 60%."

Blinatumomab is a type of immunotherapy administered intravenously and brings a normal immune cell called a T cell close to a leukemia cell so it can destroy it. The Food and Drug Administration approved blinatumomab for patients in remission who have traces of cancer, also known as measurable residual disease (MRD)-positive. In this study, blinatumomab was added to see if it could lessen the risk of the ALL coming back and relapsing in a person who had no detection of cancer, also known as MRD-negative, following initial chemotherapy.

The study enrolled 488 participants aged 30 to 70 years with BCP-ALL, and 224 of them were in remission and MRD-negative following the initial course of treatment with chemotherapy. The 224 participants were equally randomized into two arms; the first arm would receive blinatumomab with chemotherapy, and the second arm would receive the standard treatment of chemotherapy alone.

The results showed that 85% of participants treated with blinatumomab and chemotherapy were alive at three years, compared to 68% of those who received chemotherapy alone, which is the standard treatment.

"We plan to build on this study to reduce the amount of chemotherapy people need to receive, ultimately leading to fewer side effects from the treatment and improving overall survival rates," Dr. Litzow says.

This study was conducted by the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group and funded in part by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health . See the full paper for the complete list of funding and authors.

Dr. Litzow has received research funding from Amgen and served on a speaker's bureau for Amgen related to this study.

A version of this article was originally published on the Mayo Clinic News Network .

Related Posts

Diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia at 38, Alli Benezra found support to navigate treatment through two pregnancies at Mayo Clinic.

With the help of specialized genetic testing at Mayo Clinic, Shannon Camlek was finally able to achieve remission of acute myeloid leukemia.

Learn about CAR-T cell therapy and research at Mayo Clinic to reduce its side effects and expand its use beyond blood cancers.

Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Endometriosis

- Excessive heat

- Mental disorders

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Fact sheets /

- Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for nearly 10 million deaths in 2020, or nearly one in six deaths.

- The most common cancers are breast, lung, colon and rectum and prostate cancers.

- Around one-third of deaths from cancer are due to tobacco use, high body mass index, alcohol consumption, low fruit and vegetable intake, and lack of physical activity. In addition, air pollution is an important risk factor for lung cancer.

- Cancer-causing infections, such as human papillomavirus (HPV) and hepatitis, are responsible for approximately 30% of cancer cases in low- and lower-middle-income countries.

- Many cancers can be cured if detected early and treated effectively.

Cancer is a generic term for a large group of diseases that can affect any part of the body. Other terms used are malignant tumours and neoplasms. One defining feature of cancer is the rapid creation of abnormal cells that grow beyond their usual boundaries, and which can then invade adjoining parts of the body and spread to other organs; the latter process is referred to as metastasis. Widespread metastases are the primary cause of death from cancer.

The problem

Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for nearly 10 million deaths in 2020 (1). The most common in 2020 (in terms of new cases of cancer) were:

- breast (2.26 million cases);

- lung (2.21 million cases);

- colon and rectum (1.93 million cases);

- prostate (1.41 million cases);

- skin (non-melanoma) (1.20 million cases); and

- stomach (1.09 million cases).

The most common causes of cancer death in 2020 were:

- lung (1.80 million deaths);

- colon and rectum (916 000 deaths);

- liver (830 000 deaths);

- stomach (769 000 deaths); and

- breast (685 000 deaths).

Each year, approximately 400 000 children develop cancer. The most common cancers vary between countries. Cervical cancer is the most common in 23 countries.

Cancer arises from the transformation of normal cells into tumour cells in a multi-stage process that generally progresses from a pre-cancerous lesion to a malignant tumour. These changes are the result of the interaction between a person's genetic factors and three categories of external agents, including:

- physical carcinogens, such as ultraviolet and ionizing radiation;

- chemical carcinogens, such as asbestos, components of tobacco smoke, alcohol, aflatoxin (a food contaminant), and arsenic (a drinking water contaminant); and

- biological carcinogens, such as infections from certain viruses, bacteria, or parasites.

WHO, through its cancer research agency, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), maintains a classification of cancer-causing agents.

The incidence of cancer rises dramatically with age, most likely due to a build-up of risks for specific cancers that increase with age. The overall risk accumulation is combined with the tendency for cellular repair mechanisms to be less effective as a person grows older.

Risk factors

Tobacco use, alcohol consumption, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and air pollution are risk factors for cancer and other noncommunicable diseases.

Some chronic infections are risk factors for cancer; this is a particular issue in low- and middle-income countries. Approximately 13% of cancers diagnosed in 2018 globally were attributed to carcinogenic infections, including Helicobacter pylori, human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and Epstein-Barr virus (2).

Hepatitis B and C viruses and some types of HPV increase the risk for liver and cervical cancer, respectively. Infection with HIV increases the risk of developing cervical cancer six-fold and substantially increases the risk of developing select other cancers such as Kaposi sarcoma.

Reducing the burden

Between 30 and 50% of cancers can currently be prevented by avoiding risk factors and implementing existing evidence-based prevention strategies. The cancer burden can also be reduced through early detection of cancer and appropriate treatment and care of patients who develop cancer. Many cancers have a high chance of cure if diagnosed early and treated appropriately.

Cancer risk can be reduced by:

- not using tobacco;

- maintaining a healthy body weight;

- eating a healthy diet, including fruit and vegetables;

- doing physical activity on a regular basis;

- avoiding or reducing consumption of alcohol;

- getting vaccinated against HPV and hepatitis B if you belong to a group for which vaccination is recommended;

- avoiding ultraviolet radiation exposure (which primarily results from exposure to the sun and artificial tanning devices) and/or using sun protection measures;

- ensuring safe and appropriate use of radiation in health care (for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes);

- minimizing occupational exposure to ionizing radiation; and

- reducing exposure to outdoor air pollution and indoor air pollution, including radon (a radioactive gas produced from the natural decay of uranium, which can accumulate in buildings — homes, schools and workplaces).

Early detection

Cancer mortality is reduced when cases are detected and treated early. There are two components of early detection: early diagnosis and screening.

Early diagnosis

When identified early, cancer is more likely to respond to treatment and can result in a greater probability of survival with less morbidity, as well as less expensive treatment. Significant improvements can be made in the lives of cancer patients by detecting cancer early and avoiding delays in care.

Early diagnosis consists of three components:

- being aware of the symptoms of different forms of cancer and of the importance of seeking medical advice when abnormal findings are observed;

- access to clinical evaluation and diagnostic services; and

- timely referral to treatment services.

Early diagnosis of symptomatic cancers is relevant in all settings and the majority of cancers. Cancer programmes should be designed to reduce delays in, and barriers to, diagnosis, treatment and supportive care.

Screening aims to identify individuals with findings suggestive of a specific cancer or pre-cancer before they have developed symptoms. When abnormalities are identified during screening, further tests to establish a definitive diagnosis should follow, as should referral for treatment if cancer is proven to be present.

Screening programmes are effective for some but not all cancer types and in general are far more complex and resource-intensive than early diagnosis as they require special equipment and dedicated personnel. Even when screening programmes are established, early diagnosis programmes are still necessary to identify those cancer cases occurring in people who do not meet the age or risk factor criteria for screening.

Patient selection for screening programmes is based on age and risk factors to avoid excessive false positive studies. Examples of screening methods are:

- HPV test (including HPV DNA and mRNA test), as preferred modality for cervical cancer screening; and

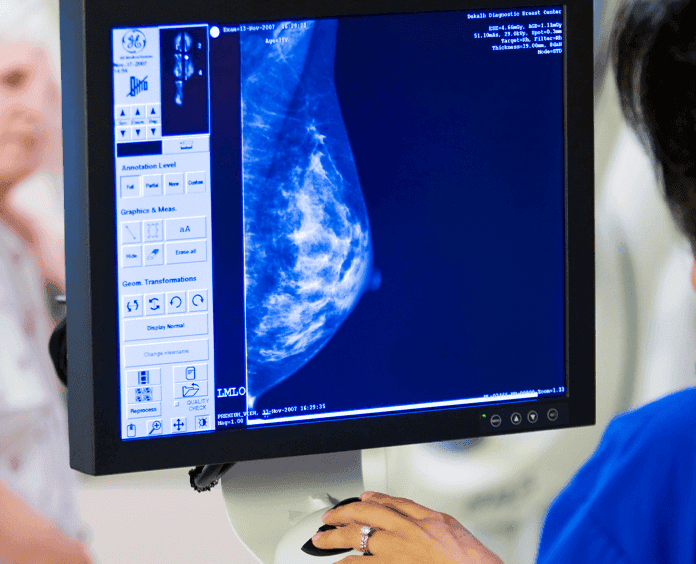

- mammography screening for breast cancer for women aged 50–69 residing in settings with strong or relatively strong health systems.

Quality assurance is required for both screening and early diagnosis programmes.

A correct cancer diagnosis is essential for appropriate and effective treatment because every cancer type requires a specific treatment regimen. Treatment usually includes surgery, radiotherapy, and/or systemic therapy (chemotherapy, hormonal treatments, targeted biological therapies). Proper selection of a treatment regimen takes into consideration both the cancer and the individual being treated. Completion of the treatment protocol in a defined period of time is important to achieve the predicted therapeutic result.

Determining the goals of treatment is an important first step. The primary goal is generally to cure cancer or to considerably prolong life. Improving the patient's quality of life is also an important goal. This can be achieved by support for the patient’s physical, psychosocial and spiritual well-being and palliative care in terminal stages of cancer.

Some of the most common cancer types, such as breast cancer, cervical cancer, oral cancer, and colorectal cancer, have high cure probabilities when detected early and treated according to best practices.

Some cancer types, such as testicular seminoma and different types of leukaemia and lymphoma in children, also have high cure rates if appropriate treatment is provided, even when cancerous cells are present in other areas of the body.

There is, however, a significant variation in treatment availability between countries of different income levels; comprehensive treatment is reportedly available in more than 90% of high-income countries but less than 15% of low-income countries (3).

Palliative care

Palliative care is treatment to relieve, rather than cure, symptoms and suffering caused by cancer and to improve the quality of life of patients and their families. Palliative care can help people live more comfortably. It is particularly needed in places with a high proportion of patients in advanced stages of cancer where there is little chance of cure.

Relief from physical, psychosocial, and spiritual problems through palliative care is possible for more than 90% of patients with advanced stages of cancer.

Effective public health strategies, comprising community- and home-based care, are essential to provide pain relief and palliative care for patients and their families.

WHO response

In 2017, the World Health Assembly passed the Resolution Cancer prevention and control in the context of an integrated approach (WHA70.12) that urges governments and WHO to accelerate action to achieve the targets specified in the Global Action Plan for the prevention and control of NCDs 2013-2020 and the 2030 UN Agenda for Sustainable Development to reduce premature mortality from cancer.

WHO and IARC collaborate with other UN organizations, inlcuing the International Atomic Energy Agency, and partners to:

- increase political commitment for cancer prevention and control;

- coordinate and conduct research on the causes of human cancer and the mechanisms of carcinogenesis;

- monitor the cancer burden (as part of the work of the Global Initiative on Cancer Registries);

- identify “best buys” and other cost-effective, priority strategies for cancer prevention and control;

- develop standards and tools to guide the planning and implementation of interventions for prevention, early diagnosis, screening, treatment and palliative and survivorship care for both adult and child cancers;

- strengthen health systems at national and local levels to help them improve access to cancer treatments;

- set the agenda for cancer prevention and control in the 2020 WHO Report on Cancer;

- provide global leadership as well as technical assistance to support governments and their partners build and sustain high-quality cervical cancer control programmes as part of the Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer;