Teaching Methods and Strategies: The Complete Guide

You’ve completed your coursework. Student teaching has ended. You’ve donned the cap and gown, crossed the stage, smiled with your diploma and went home to fill out application after application.

Suddenly you are standing in what will be your classroom for the next year and after the excitement of decorating it wears off and you begin lesson planning, you start to notice all of your lessons are executed the same way, just with different material. But that is what you know and what you’ve been taught, so you go with it.

After a while, your students are bored, and so are you. There must be something wrong because this isn’t what you envisioned teaching to be like. There is.

Figuring out the best ways you can deliver information to students can sometimes be even harder than what students go through in discovering how they learn best. The reason is because every single teacher needs a variety of different teaching methods in their theoretical teaching bag to pull from depending on the lesson, the students, and things as seemingly minute as the time the class is and the subject.

Using these different teaching methods, which are rooted in theory of different teaching styles, will not only help teachers reach their full potential, but more importantly engage, motivate and reach the students in their classes, whether in person or online.

Teaching Methods

Teaching methods, or methodology, is a narrower topic because it’s founded in theories and educational psychology. If you have a degree in teaching, you most likely have heard of names like Skinner, Vygotsky , Gardner, Piaget , and Bloom . If their names don’t ring a bell, you should definitely recognize their theories that have become teaching methods. The following are the most common teaching theories.

Behaviorism

Behaviorism is the theory that every learner is essentially a “clean slate” to start off and shaped by emotions. People react to stimuli, reactions as well as positive and negative reinforcement, the site states.

Learning Theories names the most popular theorists who ascribed to this theory were Ivan Pavlov, who many people may know with his experiments with dogs. He performed an experiment with dogs that when he rang a bell, the dogs responded to the stimuli; then he applied the idea to humans.

Other popular educational theorists who were part of behaviorism was B.F. Skinner and Albert Bandura .

Social Cognitive Theory

Social Cognitive Theory is typically spoken about at the early childhood level because it has to do with critical thinking with the biggest concept being the idea of play, according to Edwin Peel writing for Encyclopedia Britannica . Though Bandura and Lev Vygotsky also contributed to cognitive theory, according to Dr. Norman Herr with California State University , the most popular and first theorist of cognitivism is Piaget.

There are four stages to Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development that he created in 1918. Each stage correlates with a child’s development from infancy to their teenage years.

The first stage is called the Sensorimotor Stage which occurs from birth to 18 months. The reason this is considered cognitive development is because the brain is literally growing through exploration, like squeaking horns, discovering themselves in mirrors or spinning things that click on their floor mats or walkers; creating habits like sleeping with a certain blanket; having reflexes like rubbing their eyes when tired or thumb sucking; and beginning to decipher vocal tones.

The second stage, or the Preoperational Stage, occurs from ages 2 to 7 when toddlers begin to understand and correlate symbols around them, ask a lot of questions, and start forming sentences and conversations, but they haven’t developed perspective yet so empathy does not quite exist yet, the website states. This is the stage when children tend to blurt out honest statements, usually embarrassing their parents, because they don’t understand censoring themselves either.

From ages 7 to 11, children are beginning to problem solve, can have conversations about things they are interested in, are more aware of logic and develop empathy during the Concrete Operational Stage.

The final stage, called the Formal Operational Stage, though by definition ends at age 16, can continue beyond. It involves deeper thinking and abstract thoughts as well as questioning not only what things are but why the way they are is popular, the site states. Many times people entering new stages of their lives like high school, college, or even marriage go through elements of Piaget’s theory, which is why the strategies that come from this method are applicable across all levels of education.

The Multiple Intelligences Theory

The Multiple Intelligences Theory states that people don’t need to be smart in every single discipline to be considered intelligent on paper tests, but that people excel in various disciplines, making them exceptional.

Created in 1983, the former principal in the Scranton School District in Scranton, PA, created eight different intelligences, though since then two others have been debated of whether to be added but have not yet officially, according to the site.

The original eight are musical, spatial, linguistic, mathematical, kinesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal and naturalistic and most people have a predominant intelligence followed by others. For those who are musically-inclined either via instruments, vocals, has perfect pitch, can read sheet music or can easily create music has Musical Intelligence.

Being able to see something and rearrange it or imagine it differently is Spatial Intelligence, while being talented with language, writing or avid readers have Linguistic Intelligence. Kinesthetic Intelligence refers to understanding how the body works either anatomically or athletically and Naturalistic Intelligence is having an understanding of nature and elements of the ecosystem.

The final intelligences have to do with personal interactions. Intrapersonal Intelligence is a matter of knowing oneself, one’s limits, and their inner selves while Interpersonal Intelligence is knowing how to handle a variety of other people without conflict or knowing how to resolve it, the site states. There is still an elementary school in Scranton, PA named after their once-principal.

Constructivism

Constructivism is another theory created by Piaget which is used as a foundation for many other educational theories and strategies because constructivism is focused on how people learn. Piaget states in this theory that people learn from their experiences. They learn best through active learning , connect it to their prior knowledge and then digest this information their own way. This theory has created the ideas of student-centered learning in education versus teacher-centered learning.

Universal Design for Learning

The final method is the Universal Design for Learning which has redefined the educational community since its inception in the mid-1980s by David H. Rose. This theory focuses on how teachers need to design their curriculum for their students. This theory really gained traction in the United States in 2004 when it was presented at an international conference and he explained that this theory is based on neuroscience and how the brain processes information, perform tasks and get excited about education.

The theory, known as UDL, advocates for presenting information in multiple ways to enable a variety of learners to understand the information; presenting multiple assessments for students to show what they have learned; and learn and utilize a student’s own interests to motivate them to learn, the site states. This theory also discussed incorporating technology in the classroom and ways to educate students in the digital age.

Teaching Styles

From each of the educational theories, teachers extract and develop a plethora of different teaching styles, or strategies. Instructors must have a large and varied arsenal of strategies to use weekly and even daily in order to build rapport, keep students engaged and even keep instructors from getting bored with their own material. These can be applicable to all teaching levels, but adaptations must be made based on the student’s age and level of development.

Differentiated instruction is one of the most popular teaching strategies, which means that teachers adjust the curriculum for a lesson, unit or even entire term in a way that engages all learners in various ways, according to Chapter 2 of the book Instructional Process and Concepts in Theory and Practice by Celal Akdeniz . This means changing one’s teaching styles constantly to fit not only the material but more importantly, the students based on their learning styles.

Learning styles are the ways in which students learn best. The most popular types are visual, audio, kinesthetic and read/write , though others include global as another type of learner, according to Akdeniz . For some, they may seem self-explanatory. Visual learners learn best by watching the instruction or a demonstration; audio learners need to hear a lesson; kinesthetic learners learn by doing, or are hands-on learners; read/write learners to best by reading textbooks and writing notes; and global learners need material to be applied to their real lives, according to The Library of Congress .

There are many activities available to instructors that enable their students to find out what kind of learner they are. Typically students have a main style with a close runner-up, which enables them to learn best a certain way but they can also learn material in an additional way.

When an instructor knows their students and what types of learners are in their classroom, instructors are able to then differentiate their instruction and assignments to those learning types, according to Akdeniz and The Library of Congress. Learn more about different learning styles.

When teaching new material to any type of learner, is it important to utilize a strategy called scaffolding . Scaffolding is based on a student’s prior knowledge and building a lesson, unit or course from the most foundational pieces and with each step make the information more complicated, according to an article by Jerry Webster .

To scaffold well, a teacher must take a personal interest in their students to learn not only what their prior knowledge is but their strengths as well. This will enable an instructor to base new information around their strengths and use positive reinforcement when mistakes are made with the new material.

There is an unfortunate concept in teaching called “teach to the middle” where instructors target their lessons to the average ability of the students in their classroom, leaving slower students frustrated and confused, and above average students frustrated and bored. This often results in the lower- and higher-level students scoring poorly and a teacher with no idea why.

The remedy for this is a strategy called blended learning where differentiated instruction is occurring simultaneously in the classroom to target all learners, according to author and educator Juliana Finegan . In order to be successful at blended learning, teachers once again need to know their students, how they learn and their strengths and weaknesses, according to Finegan.

Blended learning can include combining several learning styles into one lesson like lecturing from a PowerPoint – not reading the information on the slides — that includes cartoons and music associations while the students have the print-outs. The lecture can include real-life examples and stories of what the instructor encountered and what the students may encounter. That example incorporates four learning styles and misses kinesthetic, but the activity afterwards can be solely kinesthetic.

A huge component of blended learning is technology. Technology enables students to set their own pace and access the resources they want and need based on their level of understanding, according to The Library of Congress . It can be used three different ways in education which include face-to-face, synchronously or asynchronously . Technology used with the student in the classroom where the teacher can answer questions while being in the student’s physical presence is known as face-to-face.

Synchronous learning is when students are learning information online and have a teacher live with them online at the same time, but through a live chat or video conferencing program, like Skype, or Zoom, according to The Library of Congress.

Finally, asynchronous learning is when students take a course or element of a course online, like a test or assignment, as it fits into their own schedule, but a teacher is not online with them at the time they are completing or submitting the work. Teachers are still accessible through asynchronous learning but typically via email or a scheduled chat meeting, states the Library of Congress.

The final strategy to be discussed actually incorporates a few teaching strategies, so it’s almost like blended teaching. It starts with a concept that has numerous labels such as student-centered learning, learner-centered pedagogy, and teacher-as-tutor but all mean that an instructor revolves lessons around the students and ensures that students take a participatory role in the learning process, known as active learning, according to the Learning Portal .

In this model, a teacher is just a facilitator, meaning that they have created the lesson as well as the structure for learning, but the students themselves become the teachers or create their own knowledge, the Learning Portal says. As this is occurring, the instructor is circulating the room working as a one-on-one resource, tutor or guide, according to author Sara Sanchez Alonso from Yale’s Center for Teaching and Learning. For this to work well and instructors be successful one-on-one and planning these lessons, it’s essential that they have taken the time to know their students’ history and prior knowledge, otherwise it can end up to be an exercise in futility, Alonso said.

Some activities teachers can use are by putting students in groups and assigning each student a role within the group, creating reading buddies or literature circles, making games out of the material with individual white boards, create different stations within the classroom for different skill levels or interest in a lesson or find ways to get students to get up out of their seats and moving, offers Fortheteachers.org .

There are so many different methodologies and strategies that go into becoming an effective instructor. A consistent theme throughout all of these is for a teacher to take the time to know their students because they care, not because they have to. When an instructor knows the stories behind the students, they are able to design lessons that are more fun, more meaningful, and more effective because they were designed with the students’ best interests in mind.

There are plenty of pre-made lessons, activities and tests available online and from textbook publishers that any teacher could use. But you need to decide if you want to be the original teacher who makes a significant impact on your students, or a pre-made teacher a student needs to get through.

Read Also: – Blended Learning Guide – Collaborative Learning Guide – Flipped Classroom Guide – Game Based Learning Guide – Gamification in Education Guide – Holistic Education Guide – Maker Education Guide – Personalized Learning Guide – Place-Based Education Guide – Project-Based Learning Guide – Scaffolding in Education Guide – Social-Emotional Learning Guide

Similar Posts:

- Discover Your Learning Style – Comprehensive Guide on Different Learning Styles

- Creating Inclusive Classrooms – Strategies and Best Practices

- 35 of the BEST Educational Apps for Teachers (Updated 2024)

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name and email in this browser for the next time I comment.

Teaching Learning Methods

- Open Access

- First Online: 23 November 2019

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Ane Landøy ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8589-2789 4 ,

- Daniela Popa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4538-7136 5 &

- Angela Repanovici ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8748-5332 6

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Education ((SPTE))

50k Accesses

2 Citations

After completing this learning unit, you will be able to:

Identify the characteristics of each method;

Differentiate between types of teaching and learning methods;

Argue the necessity of the adequacy of a didactic method to the proposed learning approach.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

- Active-participatory teaching methods

- Graphical viewing methods

- Metacognition facilitation methods

Problem solving methods

In this chapter we present an overview of pedagogical perspective from which we interpreted teaching information literacy. In order to achieve an effective teaching, we combined the techniques and methods considered classic with the modern ones (Blummer 2009 ). But the literature highlights that not only the technical aspects of a training determine the achievement of educational goals (Mackey and Jacobson 2007 ; Harkins et al. 2011 ). The human resource is a very important factor. Thus we believe that team teaching (teacher and librarian), creating a curriculum designed by a team of specialists information literacy, librarians and experts in teaching and learning are essential to achieve effective teaching learning. This belief was the basis of the collaboration between the authors of this book, combining the different areas of expertise to produce a product that can be considered, hopefully, a useful help to the trainer.

The way we teach is influenced by the way we perceive learning. Learning theories are closely related to IQ theories. The latter highlights the existence of a general intelligence that determines the level of development of learning capacity (Muijs and Reynolds 2017 ) as well as the existence of multiple intelligences (Gardner 1987 ).

One of the most popular classifications of learning theories has as a main criterion the historical period in which these theories and paradigms of psychology emerged. From this point of view, we group the theories of learning into: behavioural, cognitive, humanistic, and constructivist.

The functions that these theories fulfil are:

Informational, referential , giving an overview of the described reality;

Explanatory trying to answer the question of why the phenomenon of learning occurs;

Predictive or anticipatory through which can be predicted phenomena that cannot be explained in themselves;

Systematisers summarising a substantial amount of information in order to make theoretical generalisations; and

Praxiological, normative and prescriptive allowing practitioners to use certain methodological guidelines (Panţuru 2010 ).

Learning patterns are derived from learning theories. The most discussed are: behavioural models, the direct training model, models centred on information processing, person-centred models, models centred on a social dimension, the mastery learning model, and the modular approach model.

Training models guide the manner of implementing of teaching strategies. Didactical or Educational Strategies are those that designate the manner of pedagogical action, in order to achieve predetermined goals. Depending on the scope of the concept, we find the existence of two types of strategies: the macro type (developed for medium and long time periods) and the micro type (built for short time periods).

Structurally, teaching strategies consist of:

Models of learning experiences;

Learners’ learning styles;

Learner motivation for learning;

Methods and training procedures used in the didactic approach ;

The resources available for education;

Specific information content;

Particularities of learning tasks;

Forms of organising the teaching activity; and

Type of assessment considered (Bocos and Jucan 2008 ).

10.1 Teaching Strategies

Teaching strategies become appropriate to an educational approach by choosing them according to certain criteria such as:

The pedagogical conception of the teacher dependent on the paradigms on which he bases his opinions;

The pedagogical conception of the historical period to which reference is made, the trends in pedagogical practice;

Didactic principles that delineate the educational process;

Competencies to be developed;

Age and pupil’s level of schooling;

Informational specific of the specialised discipline;

Psychosocial characteristics of the group or class of students;

The time set for achieving the objectives; and

The specificity of the school unit to which the class or group of students belongs.

By degree of generality :

General strategies (used in multiple learning situations or school disciplines); and

Particular strategies (specific to less generalisable approaches, to specific disciplines);

According to the field of predominant instructional activities and the nature of operational objectives (Iucu 2005 ):

Cognitive strategies;

Psychomotor or action strategies;

Emotional strategies; and

Mixed strategies;

By the logic and strategies of student’s thinking (Cerghit 2002 ):

Inductive strategies;

Deductive strategies (axiomatic);

Analogue strategies;

Transductive strategies; and

By the level of directive/non-directive of learning :

Algorithmic/prescriptive strategies :

Explanatory-reproductive (expositive);

Explanatory-intuitive (demonstrative);

Algorithmic; and

Programmed;

Heuristic/non-algorithmic strategies :

Explanatory-investigatory (semi-disciplined discovery);

Conversation-heuristic;

Independent discovery;

Problematised;

Investigative observation;

Inductive-experimental; and

Mixed strategies (Bocos and Jucan 2008 )

Algoritmico-heuristic.

10.2 Methods and Training Procedures

The methods and the training procedures used in the didactic approach are elements of a didactic strategy. Although many other structural elements of educational strategy are equally important, field practitioners tend to focus especially on didactic methods as the visible part of the didactic iceberg. We intended to invite the reader of this paper to reflection, presenting very briefly some of the most well-known didactic strategies to discover the importance and interdependence of each element of the strategy with the others.

The method is a term of Greek origin “methodos” (“metha” translating to through and “odos” meaning direction, road ), namely it can be translated by the phrase “the way to”. The didactic method is a way through which the teacher conducts and organises the training of the trainees.

We define the method as “the assembly or the system of processes or modes of execution of the operations involved in the learning process, integrated into a single flow of action, in order to achieve the objectives proposed” (Cerghit 2006 , p. 46). The degree of freedom and of directing depends on the pedagogical conception at the core of the pedagogical approach.

It is recommended that the choice of teaching-learning methods to be made according to training objectives, the skills of the trainees and trainer and the information content to be mastered.

At present, pedagogues prefer less structured approaches, ambiguous contexts that allow students to discover by themselves the most appropriate way to introduce new information into their own knowledge systems. Although this orientation is predominant, the student-centered curriculum, literature is abundant in studies that still call into question a student centered approach (Garrett 2008 ; Sawant and Rizvi 2015 ; Jacobs et al. 2016 ).

The functions which teaching-learning methods carry out are:

The cognitive function , representing the way of access to knowledge, and information, necessary for its plenary development;

The formative-educational function through exercising skills, certain motor and psychic functions at the same time as discovering scientific facts;

The motivational function inspiring the student, transforming the learning activity into an attractive, stimulating activity;

The instrumental function allows the method to be positioned between the objectives and the results of the didactic activity, being a working tool, a means to efficiently achieve the plan and achieve the intended purpose; and

The normative function of optimising action is highlighted by the prescriptions, rules and phases that the method brings in achieving the objective (Cerghit 2006 ).

10.2.1 The Relationship Between the Method and Procedure

Some of the constituent elements of the methods are training procedures. These are required operations chained into a hierarchical and logical structure to ensure the effectiveness of the teaching method. Between the method and procedure there are subordinate relationships, with structural and functional connotations. Sometimes a method can become a procedure if it is used for a short period of time. A relevant example is that of the explanation method. Rarely, the method is used as the main approach of a lesson, but often, regardless of the method used, we use explanation in a training process.

10.3 Classifications of Teaching—Learning Methods

There are various classifications in the literature according to different criteria. Due to the multiple functions that methods can perform as well as the different variants they may have, the rankings in certain categories are relative. Thus, a method may belong to different categories, depending on classification criteria. The most popular classifications have as main criteria: the person/persons on whom the teaching activity is centered, the type of training/lesson, the type of activity predominantly targeted, the degree of activism/passivity of the pupils, the preponderant means of communication (oral, written).

We continue by presenting a classification of teaching and learning methods, which contains examples of methods in certain categories, without claiming to be exhaustive.

By the criterion of the persons on whom the teaching activity is centered or by degree of student activity:

Centred on the teacher—expository methods :

Lecture/exposure;

Story telling;

Explanation; or

Instruction.

Focused on the interaction between teacher and student

Conversation;

Collective discussion;

Problem solving;

Troubleshooting;

Demonstration;

Case analysis or study; or

Didactic game.

Student centred or active-participatory methods :

Methods of organising information and graphic visualisation:

Cube method;

Method of mosaic or reciprocal teaching;

Conceptual map;

Diagrams; or

Training on simulator.

Methods of stimulating creativity:

Brainstorming;

Philips 6–6;

6/3/5 Technique;

SINECTICA; or

Panel discussions.

Methods to facilitate metacognition:

The Know/Want/Learn method;

Reflective reading;

Walking through the pictures; or

The Learning Log.

10.4 Descriptions of the Methods Used in the Examples in Previous Chapters

Expository Methods :

It is considered a traditional, verbal, and exponential didactic method. Although some authors treat the lecture differently from exposure, the great similarities between them lead us to treat them together. Pedagogical practice highlights several forms of lecture according to the age of educators, their life experience, exposure time and scientific discipline: school lecture story, explanation, university lecture, lecture with opponent, and lecture—debate.

Except for the lecture with an opponent, the method involves passing a consistent volume of information in a verbal form in a monologue from the teacher to the students. As it generates a high degree of passivity among students, exposure methods have been strongly criticised but have also experienced improvements following these criticisms.

The school lecture requires the presentation of a series of ideas, theories, interpretations of scientific aspects, allowing the formation of a coherent image of the designated reality.

The story is used predominantly in educational contexts where trainees have limited life experience. It consists in presenting the information in a narrative form, respecting a sequence of events.

The explanation is an presentation in which rational logical reasoning is obvious, clarifying blocks of information such as theorems, or scientific laws.

The university lecture focuses more on descriptive—explanatory presentation of the results of recent scientific research, due to the fact that the particularities of the age and the level of education of the participants is different. The time allocated to it is longer than for the other exposure methods.

Lecture with an opponent involves the intervention of another teacher or a well-informed student by asking questions or requesting additional information. It creates an effect as in a role play that ensures dynamism of presentation.

The lecture—the debate is based on the teacher’s presentation of essential information and its deepening through debate with the students. The success of the method is requires that the target audience should have a minimum knowledge in advance.

In an attempt to reduce its limits, several conditions have been observed to achieve a high level of efficiency:

Information content should be logically connected, essentialised, without redundant information;

The quantity of information is appropriate to the psycho-pedagogical peculiarities of the educated;

Use examples to connect theory to practice;

Use language appropriate to the audience’s competency, explaining less-known scientific terms;

Maintaining an optimal verbal rhythm (approximately 60–70 words per minute) and an intensity adapted to the particularities of the audience;

Increased attention to expressive elements of verbal and nonverbal communication;

Maintaining visual contact with the public, adjusting speech according to their reactions;

Use of means of scientific expression to help communication (diagrams, schemes, or semantic maps);

Providing recapitulative loops to maintain the logical connection of ideas; and

Providing breaks or alternating scientific discourse with less formal or fun aspects that allow defocusing and refocusing the audience’s attention.

Advantages of a lecture :

A consistent amount of knowledge can be transmitted within a relatively short time frame;

Stimulates curiosity and stimulates pupils’ interest in the subject;

It presents a coherent presentation model and manner to systematise a theme and organise information;

Pupils know modalities to express and express themselves; and

Students can receive additional information that helps explain the interpretation of a scientific reality.

Disadvantages of lecture :

Presents fewer formative and more informative links;

Generates passivity among students;

Mild loss of attention and boredom;

Does not allow individualising the pedagogical discourse;

Induces a high degree of uniformity in behaviour; and

Few opportunities to check understanding of the discourse.

Conversation

Conversation consists in the didactic use of the questions through in-depth examination of a theme, capitalising on pupils’ answers in order to develop the logical reasoning of thinking. The conversation has several forms including: heuristic, examiner, collective discussion, and debate.

In its application, it is necessary to observe several conditions for the method to be considered effective. Thus, the teacher must ensure a socio-emotional climate appropriate to the conversation that will follow, to raise interest in the subject to be debated, to manage the number of participants in the discussion (maximum 20 people are considered optimal), and to allow each member to express their opinion. If the number of participants is higher, it is recommended to build several smaller discussion groups. The teacher will pay attention to the ergonomics of the space, facilitating the settlement of people in a way that they can communicate easily. The arrangement of the participants in a circle is preferable. Also, the teacher will assign the role of discussion moderator, will temper the tendencies of some to monopolise discussions and stimulate the involvement of the more reserved. Students will know the topic under discussion, they will be taught to present ideas in a smooth, appropriate way and allow others to express themselves. The teacher will also give importance to time, so that all the topics proposed are discussed.

Requirements for Formulating Questions :

To be correctly expressed, logically and grammatically;

The question contains limited content in need of clarifications, to be precise;

Questions can be varied: some claiming data, names, definitions, explanations, others expressing problematic situations;

Giving the necessary thinking time, depending on the difficulty of the questions; and

Students will be stimulated to ask questions that require complex answers, avoiding those which suggest the answer or have closed answers (yes/no).

Response Form Requirements :

Be grammatically and logically correct, regardless of the school discipline in which it is formulated;

The answer is as complete as possible and appropriate to the question; and

Avoid fragmented, or vague responses.

The heuristic , Socratic, mauvetic conversation was designed to lead to the “discovery” of something new for the learner. Presumes related series of questions and answers at the end of which to shape out, as a conclusion, new scientific facts for the student. Essential in this method is combining questions and answers in compact structures, each new question having as its origin or starting point the answer to the previous question. A disadvantage in its application is the conditioning of a pupil’s knowledge experience, which allows the formulation of answers necessary to the questions that are addressed to him.

Advantages of using the method :

Flexibility of logical operations, hypothetical-deductive reasoning of thinking;

Developing the vocabulary, organising ideas in elevated communication structures;

Forming a personal communication style.

Disadvantages of using the method :

It is dependent on the student’s previous knowledge and experience;

Lack of interest on certain topics may generate passivism or negativity;

Difficulty in involving all participants;

Some important aspects may remain undiscussed.

Methods of Direct and Indirect Exploration

Exercise Method

The method aims to obtain a high level of skill in the use of algorithms, to form or to strengthen a skill or ability. It can apply to any school discipline. The method consists of performing a repetitive and conscious action to learn a performance model or to automate the steps required to achieve high performance.

Depending on the form criterion of the exercise, they may be: oral, written or practical. Given their purpose and complexity, one can distinguish between exercises: introductory (done with the teacher), to consolidate a model of reasoning or movement (performed under the supervision of the teacher or independently), exercises with the role of integrating information, skills and abilities into ever larger systems, creative exercises or heuristics.

In order to achieve the optimal exercise, it is necessary to comply with certain conditions such as:

Conscious and correct assimilation of the model;

Using exercises that vary in form, to avoid negative emotions and stiffness;

Observing the didactic principle of grading the difficulty as far as mastering the previous levels;

(Self) applying corrective feed back immediately; and

Use an optimal number of exercises.

Advantages of using the method

The method allows the formation of skills or their consolidation in the shortest possible time, avoiding learning by trial and error. It produces positive emotional states due to satisfaction through success. Generates growth at a motivational level. It may be the basis for the formation of perseverance and will.

Disadvantages of using the method

It can generate rigidity in learning behaviour, stagnation in learning. If different forms of exercise are not used, it will cause fatigue, the impossibility of identifying similar structures that require the same type of exercises. Not scheduling learning can lead to adverse effects on the maintenance of new information, knowledge or formed skills.

Demonstration

The method consists in condensing the information that the student receives into a concrete object, a concrete action, or the substitution of objects, actions or phenomena.

Demonstration with objects involves the use of natural materials (rocks, plants, chemicals) in an appropriate educational context (used in a laboratory or natural environment). This type of demonstration is extremely convincing due to the direct, unmediated character of the lesson.

Demonstration with actions consists of a concrete example, not “mimed” by the teacher, along with the teacher’s explanations, followed by student practice.

Demonstration with substitutes (maps, casts, sheets, three-dimensional materials) is required when the object, the phenomenon we want to explain, is not directly accessible.

Combined demonstration —demonstration through experiences (combination of the above). One form of combined demonstration is that of a didactic drawing, combining the demonstration with action with that with a substitute.

Demonstration by technical means using multimedia, audio-visual means, highlighting aspects impossible or difficult to reproduce in another context and that can be repeated many times.

The method requires certain conditions for organising the space where the demonstrations take place (such as opaque curtains, lab, or niche.); special training for the teacher in maintaining the equipment, devices, materials used for this purpose.

Access to concrete objects or phenomena that cannot be accessed within limits of time and space;

Using substitutes simplifies, through visualising or schematising, the understanding of the composition of objects or phenomena;

Can be used for a long time;

The use of substitutes or technical means is less expensive than originals; and

Some aspects of reality cannot be reduced to be explained in a teaching environment.

The lack of correlation of this method with the modeling and the exercise may lead to didactic inefficiency;

Requires special technical equipment;

Students receive ready-made knowledge, thus not practising independent thinking;

Use of complicated procedures and pretentious language can distract the student from the essence of the activity.

This method can be used to deliver effective models (a simplified reproduction of the original) of action or thought. Uses several procedures:

Changing the dimensions of natural aspects to a usable scale (models, casts);

Concretising abstract notions (use of objects or forms to understand the figures);

Abstraction (rendering by numerical and/ or letter formulas of certain categories of objects, actions); and

Analogy (creating a new object comparable to the structure or functionality of a similar object).

Using the model involves activating/energising the student; and

Allows an efficient way of action.

Can form rigid behaviours; and

Insufficient practice of divergent thinking.

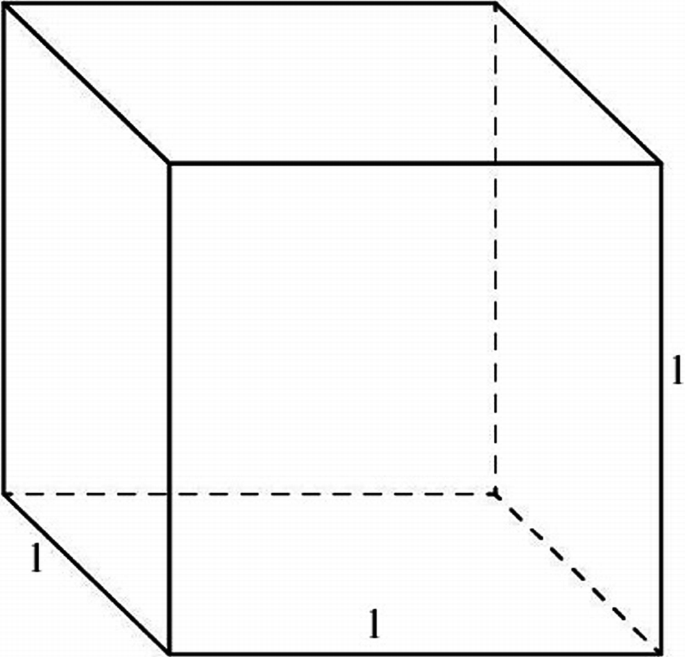

The Cube Method

The cube model is ideal for exercising students’ analysis capabilities and exploring multiple dimensions of a subject’s interpretation. It is based on an algorithm with the following sequences: description, comparison, analysis, association, application and discussion. It is ideal for usage by sub-groups or pairs of students.

It is done on a cube that on each of whose faces one of the following operations can be written: describes, compares, analyses, associates, applies, or discusses. It is recommended that the sides of the cube are covered in the above mentioned order, following the steps from simple to complex. If the method is applied to groups of students experienced in the use of such methods, each subgroup, team, or pair may receive a random assignment from the ones listed above.

The topic of the lesson or the issue to be analysed is announced. Six activity teams are formed, the activity procedure will be explained. Specify the task of each team, starting from the subject under consideration, the study material shared by all groups. The order of the stages will be kept, therefore: the first team will describe the subject matter in question; the second will compare the subject with that previously learned; the third will associate the central concept with the other; the fourth will analyse the phenomenon, the discussed subject matter, insisting on highlighting the details; the fifth team will highlight the applicability of the theme; and the sixth will discuss cons or pros.

The teams will present the results of their work, they will fill in new details that come up after the discussions. A variation of the method requires that the presentation of the contents of each team to be done within six minutes, giving one minute for each face of the cube. The results are displayed or recorded on the board to be commented by all participants (Fig. 10.1 ).

The advantages of this method are the demand for attention and thought, giving students the opportunity to develop the skills needed for a complex and integrative approach. Individual work, working in teams or the participation of the whole class in meeting the requirements of the cube is a challenge and results in a race to prove correct and complete assimilation of knowledge.

Requires more rigorous and lengthy training; may not be used in any lessons; information content is smaller; requires increased attention of students; and their ability to make connections and find the answers themselves.

The Mosaic Method

The method is based on group cooperative learning and teaching the acquisition of each team member to each other (intertwining individual and team learning). The mosaic is a method that builds confidence in the participants’ own strengths; develops communication skills (listening and speaking); reflection; creative thinking; problem solving; and cooperation.

Steps in engaging the activity

The teacher asks for the formation of teams of four students. Each team member receives a number from one to four. Students are grouped according to the received numbers. They are cautioned not to forget the composition of the original groups. Newly formed teams receive personalised cards that contain parts of larger material (the material has as many parts as the groups are formed). The teacher explains the topic to be addressed. Expert groups analyse the material received, consult each other and decide how to present the information to the members of the original groups.

Experts return to the initial teams and teach the information to others. If, until this stage, the teacher has only the role of monitoring the work of the groups, he can now intervene, clarifying unclear aspects. Teaching will be done in the logical order of material distribution that must coincide with scientific logic. At the end of the activity, a systematisation of the acquired knowledge will be presented before all the groups. The teacher can ask questions to discover the level of understanding the information studied.

All students contribute to the task. Students practise active listening and cooperate in solving requests. They are also encouraged to discover the most appropriate means of transmitting information and explaining to colleagues. Students are trained in the efficient organisation of working time. Students have freedom to choose their method of learning and teaching colleagues.

One of the biggest drawbacks of the method is the high cost of time. There is a risk that some groups may not finish their tasks in a timely manner and slow the activity of the whole group. It is also possible to generate formalism with pupils being superficially involved in didactic activity.

The best-known methods in this category are questioning, problem solving, and learning through discovery. They are based on the creation of a situation, or structures with insufficient data that give rise either to a socio-cognitive conflict, or a cognitive dissonance where the knowledge previously acquired by the student is insufficient or incomplete to solve the difficulty or a problem situation in which the student must apply his knowledge under new conditions. The problem-solving approach is a context in which the student learns something new.

In order for students to become consciously and positively involved in a problematic situation, they must be trained gradually in this educational approach. The teacher is responsible for explaining the problematic situation and providing guidance in solving it. Students, in their problem solving effort: analyse the problem’s data; select significant details; find correlations between data; use creative imagination; build solutions; and choose the right solution.

Stimulates students’ interest;

Exercises the operating schemes of thinking; and

Stimulates creativity.

Problems may be inadequate for the level of cognitive development and level of student knowledge, thus causing students to withdraw from such situations.

Methods of Information Management and Graphics Visualization :

Conceptual Map

Being able to make connections between acquired knowledge, to organise it in a well-defined structure is just as important as having a lot of complex information. Conceptual maps or cognitive maps are graphical renderings of an information system or concepts in a hierarchical or logical order. They can be used in all three processes: teaching, learning, or evaluation. Depending on the particularities of the trainees and the specificity of the educational discipline, the conceptual maps may be different. For conceptual schematics, circles, stars, and cottages can be used. Single or bidirectional arrows or lines can represent connections. A conceptual map contains at most one or two main themes, 10–15 subtopics, and tertiary subtitles, if there are significant details supporting the structure or relevant examples. The first concepts that are plotted, as well as the relationships between them, are the main ones, then the secondary ones are drawn. If needed, the tertiary ones are drawn. Then the relationships are drawn between them, and words can be used to explain relationships (they are written on the arrows).

It is important to get students to work with them because their construction involves the practice of cognitive operations such as: analysis, synthesis, comparison, systematisation, classification, hierarchy, argumentation, and evaluation. By building these maps, the student actively participates in their own training, seizing the structures that further develop the strength of the links between knowledge, and learning much more easily. Conceptual maps facilitate easy updating of information systems.

In evaluating conceptual charts, account will be taken of the correctness of concepts, the relevance of those identified and the relationships established between them.

Facilitates the storage and updating of information systems;

Visual memory is exercised;

The imagination, and creativity is exercised;

Forms logical thinking;

Usable in several school subjects;

Can be a pleasant and coherent way of systematisation, and consolidation of knowledge; and

Are flexible structures that can undergo improvements, and enrichments.

Requires a high degree of activism and involvement of student’s in their training;

May require mental effort too demanding for some students; and

Those with a visual learning style are advantaged.

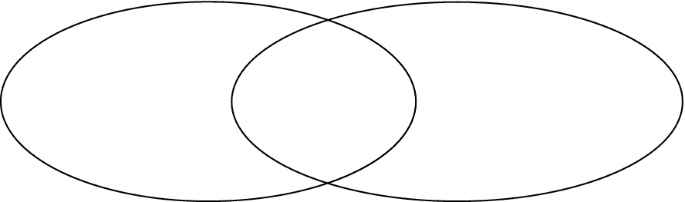

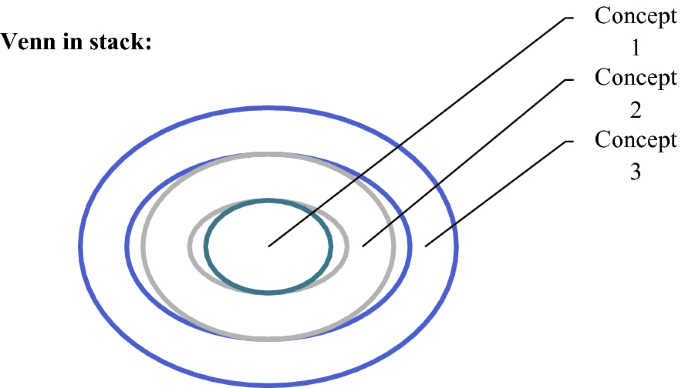

Venn Diagram

This method calls for students’ analysis and comparison capabilities, asking for the graphical organisation of information in two partially superimposed circles, which represent two notions, aspects, ideas, processes, or facts to be debated (Marzano 2015 ). In the overlapping area, the common attributes of the analysed concepts are placed, and in the free parts will be placed the aspects specific only to each concept. They are useful in all stages of the learning process: teaching, learning, and evaluation. Two types of Venn diagrams are commonly used: linear and stack.

Venn linear :

See Fig. 10.2 .

Venn linear

Venn in stack :

See Fig. 10.3 .

Develops the ability to hierarchise concepts;

Practice ability to grasp relationships between related issues; and

Exercises the ability to reason.

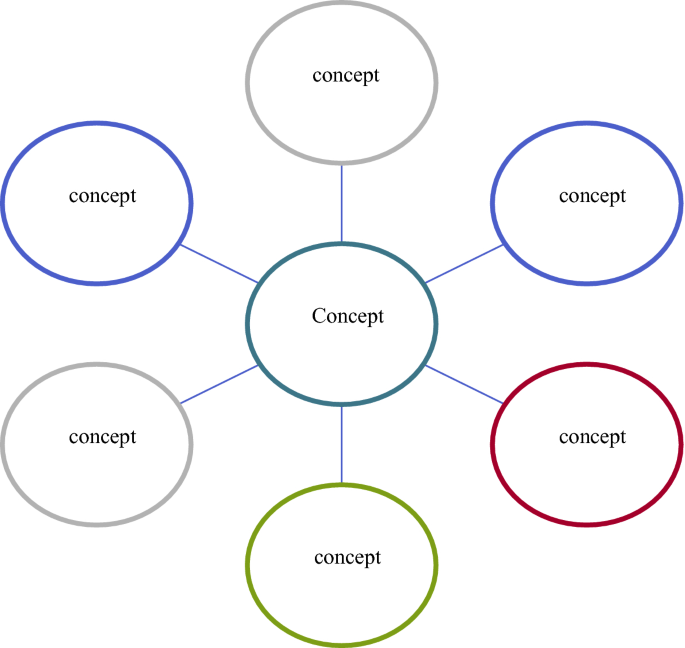

The Grape Bunches Method

“The grape bunches” method aims to integrate past knowledge and fill it with new information. It is a method that can be used both individually and in groups. It is also a technique that allows connections to be made between concepts. It is useful in recapitulative tasks or knowledge building lessons, in summative assessment of a unit of learning but also in teaching new content, because it allows students to think freely. It can be combined with other techniques or become a technique in another method.

The method involves several distinct steps:

Students are informed that they will use the bunch method and how to use it;

Groups will be formed, if it is a group activity;

The group designates the member who will build the clusters or if the activity is carried out individually, each one will draw the diagram;

If the activity is from the front, then the teacher will draw the diagram on the blackboard;

The teacher presents the key concept that will be analysed. He presents the chosen way of work, either by free expression or by updating previous contents. The teacher asks students to make connections between the concepts, phrases or ideas produced by the key term or central issue through lines or arrows, thus building up the cluster structure;

If it is a pairactivity, desk mates or teams will consult and work out the result of their work; and

The final results are discussed in front of the class, a question mark is added to incorrect concepts, necessary explanations are given and the final result is corrected. Also, trainees are invited to create new connections with aspects not taken into discussion.

The role of the teacher is to organise, monitor and support students’ work, to synthesise the information they receive, to ask questions and request additional information and to stimulate the production of new links between concepts or new ideas.

Developing cognitive capabilities for interpretation, identification, classification and definition;

Develop reflection, evaluation and self-assessment capabilities;

The method encourages the participation of all students;

Evaluate each student’s way of thinking;

Stimulates students to make connections between concepts;

It is a flexible method because it can be used successfully to evaluate a content unit, but also during teaching;

Stimulates student’s logical thinking;

Increases learning efficiency (students can learn from each other); and

The method helps the teacher to assess the extent to where students are relative to curriculum standards (Fig. 10.4 ).

Bunch method

Students can deviate from the topic discussed since it is a method that is based on creativity;

The method takes a long time to process ideas; and

There is a possibility for each student not to actively participate.

Tree Schemes

These may be horizontal or vertical. Among the horizontal ones we mention: horizontal cause—effect type; situation—problem—explanation type; and classification type. Some of the best-known vertical tree schemes are Tree of Ideas and Concept Tree.

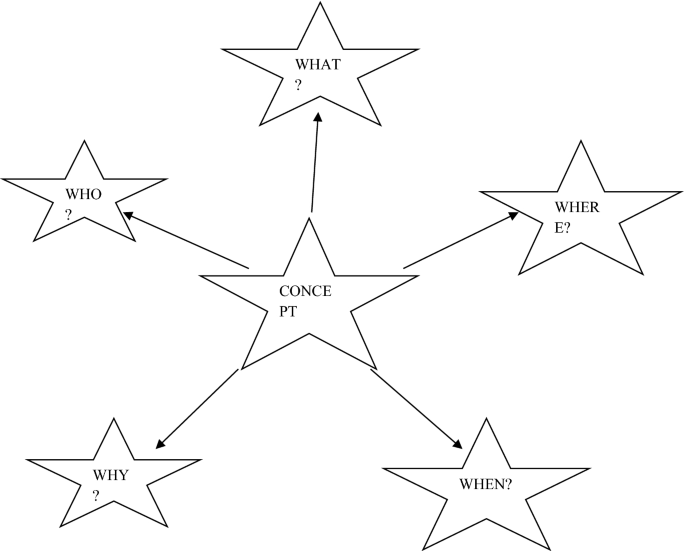

Starbursting

The method is considered a method of information management and graphic visualisation. It is a useful method in problem solving and one to stimulate the creativity of the trainers, similar to brainstorming. The difference is in the organisation of known information according to some key questions.

Write the issue or concept that will be debated on a whiteboard or flip chart and frame in a star. The teacher adds as many questions as possible to that concept. Each question will be framed in one star. Initial questions used will be essential questions, such as: who; what; when; where; and why; which may then give rise to other complex questions (Fig. 10.5 ).

Starbursting method

Proposing the problem, and the concept;

Organising the class in several subgroups, each of them stating the problem on a sheet of paper;

The elaboration in each group of a list of various questions related to the issue to be discussed;

Communicating the results of the group activity; and

Highlighting the most interesting questions and appreciating teamwork.

This is a method considered by students to be relaxing and enjoyable;

Stimulates individual and group creativity, the manifestation of spontaneity;

It is easy to apply, suitable for many types of student groups with different psychoindividual characteristics;

It develops the spirit of cooperation;

It creates the possibility of contagion of ideas;

Develops teamwork skills;

Stimulation of all participants in the discussion; and

There is no need for elaborate explanations, as it is very easy to understand by all students.

It takes a long time for application; and

Lack of involvement from some students.

Methods to Facilitate Metacognition :

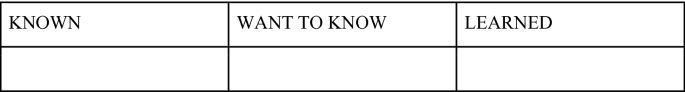

The “I Know/I Want to Know/I Learned” method

The method consists in valuing previous experience of the subject matter and discussing the prerequisites. The premise behind this method is to reconsider students’ previous or pre-requisite knowledge when introducing new insights. It can also be an excellent formative assessment of the lesson, an instrument for stimulating metacognition, but also a means for the teacher to get feedback on the understanding of new knowledge by students.

Method of implementation:

Presentation of the theme of the activity;

Dividing the class of students into sub-groups;

The teacher distributes the support sheets and asks students to inventory everything they know about the subject;

Students fill in the columns “KNOWN” and “WANT TO KNOW” of the worksheet table. In the column “KNOWN”, students will add all known aspects related to the subject matter under discussion. In the column “WANT TO KNOW”, those questions that arise in relation to the subject under consideration will be passed. Questions are identified as having an important role in guiding and personalising reading;

Individual reading of the text;

Fill in the column “LEARNED” in close connection with previously asked questions, highlighting those who receive such an answer;

In the next step, students will compare the results of the three analysis fields; and

Final discussions and drawing conclusions in a plenary.

Active reading from students;

Development and exercise categorisation capacity;

Increasing the motivation of students to engage in activity;

Stimulating students’ creativity; and

Good retention of the information presented during the course.

Difficulties can arise in formulating proper questions about the topic being debated;

The teacher must exercise the roles of organizer and facilitator in order for the activity to be accomplished and to achieve its objectives; and

May be demanding and tiring for younger participants.

Methods of Stimulating Creativity :

Brainstorming

The method stimulates students’ productivity and creativity. The basic principle of the method is “quantity generates quality”. By using this method students are encouraged and requested to participate actively avoiding the beaten path. Brainstorming facilitates exercising capabilities to critically analyse real situations, a random association that allows discovering unpredictable sources of inspiration, and making decisions about choosing the most appropriate solutions. This way, creativity is practised and allows a person to express himself genuinely. It has a beneficial effect on interpersonal relationships among the group of students.

The method’s steps:

The theme is chosen and the task is announced;

Students are asked to express as quickly, as concisely as possible all ideas as they come to their mind in solving a problem situation. They can associate with the ideas of their colleagues; they can take over, complete or transform their ideas. Any kind of criticism is prohibited, not to inhibit creative effort. The principle governing activity is “quantity generates quality”;

All ideas are recorded;

Leave a few minutes to “settle” ideas that were given and received;

The ideas issued are repeated, and students build criteria to assemble concepts given by categories, and key words;

The class of students is divided into subgroups, according to ideas, for debate. A variation at this stage is a debate in a large group, critically analysing and evaluating ideas; and

The results of each subgroup are communicated in varied and original forms such as: schemes, verbal constructions, images, songs, mosaic, and role-plays.

It stimulates creativity;

The development of critical thinking and the ability to argue;

The development communication skills;

Active participation of all students/learners;

Low application costs, broad applicability;

Enhancing the self-confidence and the spirit of initiative of a student; and

The development of a positive educational climate.

Time-consuming;

Success of the method depends on the moderator’s ability to lead the discussion in the desired direction;

It can be tedious and demanding for the participants; and

It proposes possible solutions to solve the problem, not an effective solution.

Applications/Exercises

Write a short essay on the subject: Didactic methods between normality and creativity .

Bibliographic Recommendations

Blummer, B. (2009). Providing library instruction to graduate students: A review of the literature. Public Services Quarterly, 5 (1), 15–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228950802507525 .

Article Google Scholar

Bocoș, M., & Jucan, D. (2008). Teoria și metodologia instruirii și Teoria și metodologia evaluării. Ediția a III-a . Pitești: Paralela 45.

Google Scholar

Cerghit, I., (2002). Sisteme de instruire alternative şi complementare. Structuri, stiluri, strategii. Bucureşti: Aramis.

Cerghit, I. (2006). Metode de învățământ. Ed. a IV-a. Iași: Polirom.

Gardner, H. (1987). The theory of multiple intelligences. Annals of Dyslexia, 37 (1), 19–35.

Garrett, T. (2008). Student-centered and teacher-centered classroom management: A case study of three elementary teachers. The Journal of Classroom Interaction , 34–47.

Harkins, M. J., Rodrigues, D. B., & Orlov, S. (2011). ‘Where to start?’ Considerations for faculty and librarians in delivering information literacy instruction for graduate students. Practical Academic Librarianship: The International Journal of the SLA Academic Division, 1 (1), 28–50.

Iucu, R. B. (2005). Teoria şi metodologia instruirii . Bucureşti: PIR.

Jacobs, J. C., van Luijk, S. J., van der Vleuten, C. P., Kusurkar, R. A., Croiset, G., & Scheele, F. (2016). Teachers’ conceptions of learning and teaching in student-centred medical curricula: the impact of context and personal characteristics. BMC Medical Education, 16 (1), 244.

Mackey, T. P., & Jacobson, T. (2007). Developing an integrated strategy for information literacy assessment in general education. The Journal of General Education , 56(2), 93–104.

Marzano, R. J. (2015). Arta și știința predării. Un cadru cuprinzător pentru o instruire eficientă. București: Ed Trei.

Muijs, D., & Reynolds, D. (2017). Effective teaching: Evidence and practice. Sage.

Panțuru, S. (coord.), (2010). Teoria și metodologia instruirii și Teoria și metodologia evaluării. Brașov: Ed. Universității Transilvania din Brașov.

Sawant, S. P., & Rizvi, S. (2015). Study of passive didactic teacher centered approach and an active student centered approach in teaching anatomy. International Journal of Anatomy and Research, 3 (3), 1192–1197. https://doi.org/10.16965/ijar.2015.147 .

Webography for the Whole Book

Erasmus+ CBHE Project 561987, “Library Network Support Services (LNSS): modernising libraries in Western Balkans through library staff development and reforming library services” 2015–2018 https://lnss-projects.eu/bal/module-7-access-to-libraries-and-society-for-learners-with-special-needs-disabilities/ .

Tempus Project. (2019). http://www.lit.ie/projects/tempus/default.aspx .

Transylvania University of Brasov also participated in two Erasmus + CBHE Projects: (561633) “Library Network Support Services (LNSS): modernising libraries in Armenia, Moldova and Belarus through library staff development and reforming library services” 2015–2018. https://lnss-projects.eu/amb/curriculum/module-7-access-to-libraries-and-society-for-learners-with-special-needs/ .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway

Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences, Transilvania University of Brașov, Brașov, Romania

Daniela Popa

Faculty of Product Design and Environment, Transilvania University of Brașov, Brașov, Romania

Angela Repanovici

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ane Landøy .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Landøy, A., Popa, D., Repanovici, A. (2020). Teaching Learning Methods. In: Collaboration in Designing a Pedagogical Approach in Information Literacy. Springer Texts in Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34258-6_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34258-6_10

Published : 23 November 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-34257-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-34258-6

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO