Does Homework Really Help Students Learn?

A conversation with a Wheelock researcher, a BU student, and a fourth-grade teacher

“Quality homework is engaging and relevant to kids’ lives,” says Wheelock’s Janine Bempechat. “It gives them autonomy and engages them in the community and with their families. In some subjects, like math, worksheets can be very helpful. It has to do with the value of practicing over and over.” Photo by iStock/Glenn Cook Photography

Do your homework.

If only it were that simple.

Educators have debated the merits of homework since the late 19th century. In recent years, amid concerns of some parents and teachers that children are being stressed out by too much homework, things have only gotten more fraught.

“Homework is complicated,” says developmental psychologist Janine Bempechat, a Wheelock College of Education & Human Development clinical professor. The author of the essay “ The Case for (Quality) Homework—Why It Improves Learning and How Parents Can Help ” in the winter 2019 issue of Education Next , Bempechat has studied how the debate about homework is influencing teacher preparation, parent and student beliefs about learning, and school policies.

She worries especially about socioeconomically disadvantaged students from low-performing schools who, according to research by Bempechat and others, get little or no homework.

BU Today sat down with Bempechat and Erin Bruce (Wheelock’17,’18), a new fourth-grade teacher at a suburban Boston school, and future teacher freshman Emma Ardizzone (Wheelock) to talk about what quality homework looks like, how it can help children learn, and how schools can equip teachers to design it, evaluate it, and facilitate parents’ role in it.

BU Today: Parents and educators who are against homework in elementary school say there is no research definitively linking it to academic performance for kids in the early grades. You’ve said that they’re missing the point.

Bempechat : I think teachers assign homework in elementary school as a way to help kids develop skills they’ll need when they’re older—to begin to instill a sense of responsibility and to learn planning and organizational skills. That’s what I think is the greatest value of homework—in cultivating beliefs about learning and skills associated with academic success. If we greatly reduce or eliminate homework in elementary school, we deprive kids and parents of opportunities to instill these important learning habits and skills.

We do know that beginning in late middle school, and continuing through high school, there is a strong and positive correlation between homework completion and academic success.

That’s what I think is the greatest value of homework—in cultivating beliefs about learning and skills associated with academic success.

You talk about the importance of quality homework. What is that?

Quality homework is engaging and relevant to kids’ lives. It gives them autonomy and engages them in the community and with their families. In some subjects, like math, worksheets can be very helpful. It has to do with the value of practicing over and over.

What are your concerns about homework and low-income children?

The argument that some people make—that homework “punishes the poor” because lower-income parents may not be as well-equipped as affluent parents to help their children with homework—is very troubling to me. There are no parents who don’t care about their children’s learning. Parents don’t actually have to help with homework completion in order for kids to do well. They can help in other ways—by helping children organize a study space, providing snacks, being there as a support, helping children work in groups with siblings or friends.

Isn’t the discussion about getting rid of homework happening mostly in affluent communities?

Yes, and the stories we hear of kids being stressed out from too much homework—four or five hours of homework a night—are real. That’s problematic for physical and mental health and overall well-being. But the research shows that higher-income students get a lot more homework than lower-income kids.

Teachers may not have as high expectations for lower-income children. Schools should bear responsibility for providing supports for kids to be able to get their homework done—after-school clubs, community support, peer group support. It does kids a disservice when our expectations are lower for them.

The conversation around homework is to some extent a social class and social justice issue. If we eliminate homework for all children because affluent children have too much, we’re really doing a disservice to low-income children. They need the challenge, and every student can rise to the challenge with enough supports in place.

What did you learn by studying how education schools are preparing future teachers to handle homework?

My colleague, Margarita Jimenez-Silva, at the University of California, Davis, School of Education, and I interviewed faculty members at education schools, as well as supervising teachers, to find out how students are being prepared. And it seemed that they weren’t. There didn’t seem to be any readings on the research, or conversations on what high-quality homework is and how to design it.

Erin, what kind of training did you get in handling homework?

Bruce : I had phenomenal professors at Wheelock, but homework just didn’t come up. I did lots of student teaching. I’ve been in classrooms where the teachers didn’t assign any homework, and I’ve been in rooms where they assigned hours of homework a night. But I never even considered homework as something that was my decision. I just thought it was something I’d pull out of a book and it’d be done.

I started giving homework on the first night of school this year. My first assignment was to go home and draw a picture of the room where you do your homework. I want to know if it’s at a table and if there are chairs around it and if mom’s cooking dinner while you’re doing homework.

The second night I asked them to talk to a grown-up about how are you going to be able to get your homework done during the week. The kids really enjoyed it. There’s a running joke that I’m teaching life skills.

Friday nights, I read all my kids’ responses to me on their homework from the week and it’s wonderful. They pour their hearts out. It’s like we’re having a conversation on my couch Friday night.

It matters to know that the teacher cares about you and that what you think matters to the teacher. Homework is a vehicle to connect home and school…for parents to know teachers are welcoming to them and their families.

Bempechat : I can’t imagine that most new teachers would have the intuition Erin had in designing homework the way she did.

Ardizzone : Conversations with kids about homework, feeling you’re being listened to—that’s such a big part of wanting to do homework….I grew up in Westchester County. It was a pretty demanding school district. My junior year English teacher—I loved her—she would give us feedback, have meetings with all of us. She’d say, “If you have any questions, if you have anything you want to talk about, you can talk to me, here are my office hours.” It felt like she actually cared.

Bempechat : It matters to know that the teacher cares about you and that what you think matters to the teacher. Homework is a vehicle to connect home and school…for parents to know teachers are welcoming to them and their families.

Ardizzone : But can’t it lead to parents being overbearing and too involved in their children’s lives as students?

Bempechat : There’s good help and there’s bad help. The bad help is what you’re describing—when parents hover inappropriately, when they micromanage, when they see their children confused and struggling and tell them what to do.

Good help is when parents recognize there’s a struggle going on and instead ask informative questions: “Where do you think you went wrong?” They give hints, or pointers, rather than saying, “You missed this,” or “You didn’t read that.”

Bruce : I hope something comes of this. I hope BU or Wheelock can think of some way to make this a more pressing issue. As a first-year teacher, it was not something I even thought about on the first day of school—until a kid raised his hand and said, “Do we have homework?” It would have been wonderful if I’d had a plan from day one.

Explore Related Topics:

- Share this story

Senior Contributing Editor

Sara Rimer A journalist for more than three decades, Sara Rimer worked at the Miami Herald , Washington Post and, for 26 years, the New York Times , where she was the New England bureau chief, and a national reporter covering education, aging, immigration, and other social justice issues. Her stories on the death penalty’s inequities were nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and cited in the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision outlawing the execution of people with intellectual disabilities. Her journalism honors include Columbia University’s Meyer Berger award for in-depth human interest reporting. She holds a BA degree in American Studies from the University of Michigan. Profile

She can be reached at [email protected] .

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.

There are 81 comments on Does Homework Really Help Students Learn?

Insightful! The values about homework in elementary schools are well aligned with my intuition as a parent.

when i finish my work i do my homework and i sometimes forget what to do because i did not get enough sleep

same omg it does not help me it is stressful and if I have it in more than one class I hate it.

Same I think my parent wants to help me but, she doesn’t care if I get bad grades so I just try my best and my grades are great.

I think that last question about Good help from parents is not know to all parents, we do as our parents did or how we best think it can be done, so maybe coaching parents or giving them resources on how to help with homework would be very beneficial for the parent on how to help and for the teacher to have consistency and improve homework results, and of course for the child. I do see how homework helps reaffirm the knowledge obtained in the classroom, I also have the ability to see progress and it is a time I share with my kids

The answer to the headline question is a no-brainer – a more pressing problem is why there is a difference in how students from different cultures succeed. Perfect example is the student population at BU – why is there a majority population of Asian students and only about 3% black students at BU? In fact at some universities there are law suits by Asians to stop discrimination and quotas against admitting Asian students because the real truth is that as a group they are demonstrating better qualifications for admittance, while at the same time there are quotas and reduced requirements for black students to boost their portion of the student population because as a group they do more poorly in meeting admissions standards – and it is not about the Benjamins. The real problem is that in our PC society no one has the gazuntas to explore this issue as it may reveal that all people are not created equal after all. Or is it just environmental cultural differences??????

I get you have a concern about the issue but that is not even what the point of this article is about. If you have an issue please take this to the site we have and only post your opinion about the actual topic

This is not at all what the article is talking about.

This literally has nothing to do with the article brought up. You should really take your opinions somewhere else before you speak about something that doesn’t make sense.

we have the same name

so they have the same name what of it?

lol you tell her

totally agree

What does that have to do with homework, that is not what the article talks about AT ALL.

Yes, I think homework plays an important role in the development of student life. Through homework, students have to face challenges on a daily basis and they try to solve them quickly.I am an intense online tutor at 24x7homeworkhelp and I give homework to my students at that level in which they handle it easily.

More than two-thirds of students said they used alcohol and drugs, primarily marijuana, to cope with stress.

You know what’s funny? I got this assignment to write an argument for homework about homework and this article was really helpful and understandable, and I also agree with this article’s point of view.

I also got the same task as you! I was looking for some good resources and I found this! I really found this article useful and easy to understand, just like you! ^^

i think that homework is the best thing that a child can have on the school because it help them with their thinking and memory.

I am a child myself and i think homework is a terrific pass time because i can’t play video games during the week. It also helps me set goals.

Homework is not harmful ,but it will if there is too much

I feel like, from a minors point of view that we shouldn’t get homework. Not only is the homework stressful, but it takes us away from relaxing and being social. For example, me and my friends was supposed to hang at the mall last week but we had to postpone it since we all had some sort of work to do. Our minds shouldn’t be focused on finishing an assignment that in realty, doesn’t matter. I completely understand that we should have homework. I have to write a paper on the unimportance of homework so thanks.

homework isn’t that bad

Are you a student? if not then i don’t really think you know how much and how severe todays homework really is

i am a student and i do not enjoy homework because i practice my sport 4 out of the five days we have school for 4 hours and that’s not even counting the commute time or the fact i still have to shower and eat dinner when i get home. its draining!

i totally agree with you. these people are such boomers

why just why

they do make a really good point, i think that there should be a limit though. hours and hours of homework can be really stressful, and the extra work isn’t making a difference to our learning, but i do believe homework should be optional and extra credit. that would make it for students to not have the leaning stress of a assignment and if you have a low grade you you can catch up.

Studies show that homework improves student achievement in terms of improved grades, test results, and the likelihood to attend college. Research published in the High School Journal indicates that students who spent between 31 and 90 minutes each day on homework “scored about 40 points higher on the SAT-Mathematics subtest than their peers, who reported spending no time on homework each day, on average.” On both standardized tests and grades, students in classes that were assigned homework outperformed 69% of students who didn’t have homework. A majority of studies on homework’s impact – 64% in one meta-study and 72% in another – showed that take home assignments were effective at improving academic achievement. Research by the Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) concluded that increased homework led to better GPAs and higher probability of college attendance for high school boys. In fact, boys who attended college did more than three hours of additional homework per week in high school.

So how are your measuring student achievement? That’s the real question. The argument that doing homework is simply a tool for teaching responsibility isn’t enough for me. We can teach responsibility in a number of ways. Also the poor argument that parents don’t need to help with homework, and that students can do it on their own, is wishful thinking at best. It completely ignores neurodiverse students. Students in poverty aren’t magically going to find a space to do homework, a friend’s or siblings to help them do it, and snacks to eat. I feel like the author of this piece has never set foot in a classroom of students.

THIS. This article is pathetic coming from a university. So intellectually dishonest, refusing to address the havoc of capitalism and poverty plays on academic success in life. How can they in one sentence use poor kids in an argument and never once address that poor children have access to damn near 0 of the resources affluent kids have? Draw me a picture and let’s talk about feelings lmao what a joke is that gonna put food in their belly so they can have the calories to burn in order to use their brain to study? What about quiet their 7 other siblings that they share a single bedroom with for hours? Is it gonna force the single mom to magically be at home and at work at the same time to cook food while you study and be there to throw an encouraging word?

Also the “parents don’t need to be a parent and be able to guide their kid at all academically they just need to exist in the next room” is wild. Its one thing if a parent straight up is not equipped but to say kids can just figured it out is…. wow coming from an educator What’s next the teacher doesn’t need to teach cause the kid can just follow the packet and figure it out?

Well then get a tutor right? Oh wait you are poor only affluent kids can afford a tutor for their hours of homework a day were they on average have none of the worries a poor child does. Does this address that poor children are more likely to also suffer abuse and mental illness? Like mentioned what about kids that can’t learn or comprehend the forced standardized way? Just let em fail? These children regularly are not in “special education”(some of those are a joke in their own and full of neglect and abuse) programs cause most aren’t even acknowledged as having disabilities or disorders.

But yes all and all those pesky poor kids just aren’t being worked hard enough lol pretty sure poor children’s existence just in childhood is more work, stress, and responsibility alone than an affluent child’s entire life cycle. Love they never once talked about the quality of education in the classroom being so bad between the poor and affluent it can qualify as segregation, just basically blamed poor people for being lazy, good job capitalism for failing us once again!

why the hell?

you should feel bad for saying this, this article can be helpful for people who has to write a essay about it

This is more of a political rant than it is about homework

I know a teacher who has told his students their homework is to find something they are interested in, pursue it and then come share what they learn. The student responses are quite compelling. One girl taught herself German so she could talk to her grandfather. One boy did a research project on Nelson Mandela because the teacher had mentioned him in class. Another boy, a both on the autism spectrum, fixed his family’s computer. The list goes on. This is fourth grade. I think students are highly motivated to learn, when we step aside and encourage them.

The whole point of homework is to give the students a chance to use the material that they have been presented with in class. If they never have the opportunity to use that information, and discover that it is actually useful, it will be in one ear and out the other. As a science teacher, it is critical that the students are challenged to use the material they have been presented with, which gives them the opportunity to actually think about it rather than regurgitate “facts”. Well designed homework forces the student to think conceptually, as opposed to regurgitation, which is never a pretty sight

Wonderful discussion. and yes, homework helps in learning and building skills in students.

not true it just causes kids to stress

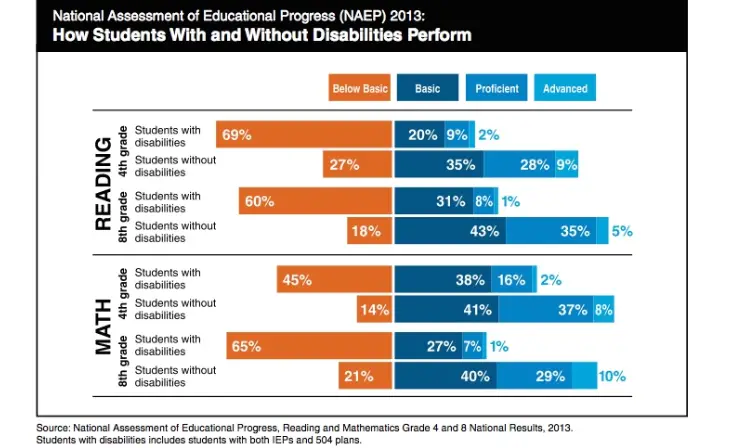

Homework can be both beneficial and unuseful, if you will. There are students who are gifted in all subjects in school and ones with disabilities. Why should the students who are gifted get the lucky break, whereas the people who have disabilities suffer? The people who were born with this “gift” go through school with ease whereas people with disabilities struggle with the work given to them. I speak from experience because I am one of those students: the ones with disabilities. Homework doesn’t benefit “us”, it only tears us down and put us in an abyss of confusion and stress and hopelessness because we can’t learn as fast as others. Or we can’t handle the amount of work given whereas the gifted students go through it with ease. It just brings us down and makes us feel lost; because no mater what, it feels like we are destined to fail. It feels like we weren’t “cut out” for success.

homework does help

here is the thing though, if a child is shoved in the face with a whole ton of homework that isn’t really even considered homework it is assignments, it’s not helpful. the teacher should make homework more of a fun learning experience rather than something that is dreaded

This article was wonderful, I am going to ask my teachers about extra, or at all giving homework.

I agree. Especially when you have homework before an exam. Which is distasteful as you’ll need that time to study. It doesn’t make any sense, nor does us doing homework really matters as It’s just facts thrown at us.

Homework is too severe and is just too much for students, schools need to decrease the amount of homework. When teachers assign homework they forget that the students have other classes that give them the same amount of homework each day. Students need to work on social skills and life skills.

I disagree.

Beyond achievement, proponents of homework argue that it can have many other beneficial effects. They claim it can help students develop good study habits so they are ready to grow as their cognitive capacities mature. It can help students recognize that learning can occur at home as well as at school. Homework can foster independent learning and responsible character traits. And it can give parents an opportunity to see what’s going on at school and let them express positive attitudes toward achievement.

Homework is helpful because homework helps us by teaching us how to learn a specific topic.

As a student myself, I can say that I have almost never gotten the full 9 hours of recommended sleep time, because of homework. (Now I’m writing an essay on it in the middle of the night D=)

I am a 10 year old kid doing a report about “Is homework good or bad” for homework before i was going to do homework is bad but the sources from this site changed my mind!

Homeowkr is god for stusenrs

I agree with hunter because homework can be so stressful especially with this whole covid thing no one has time for homework and every one just wants to get back to there normal lives it is especially stressful when you go on a 2 week vaca 3 weeks into the new school year and and then less then a week after you come back from the vaca you are out for over a month because of covid and you have no way to get the assignment done and turned in

As great as homework is said to be in the is article, I feel like the viewpoint of the students was left out. Every where I go on the internet researching about this topic it almost always has interviews from teachers, professors, and the like. However isn’t that a little biased? Of course teachers are going to be for homework, they’re not the ones that have to stay up past midnight completing the homework from not just one class, but all of them. I just feel like this site is one-sided and you should include what the students of today think of spending four hours every night completing 6-8 classes worth of work.

Are we talking about homework or practice? Those are two very different things and can result in different outcomes.

Homework is a graded assignment. I do not know of research showing the benefits of graded assignments going home.

Practice; however, can be extremely beneficial, especially if there is some sort of feedback (not a grade but feedback). That feedback can come from the teacher, another student or even an automated grading program.

As a former band director, I assigned daily practice. I never once thought it would be appropriate for me to require the students to turn in a recording of their practice for me to grade. Instead, I had in-class assignments/assessments that were graded and directly related to the practice assigned.

I would really like to read articles on “homework” that truly distinguish between the two.

oof i feel bad good luck!

thank you guys for the artical because I have to finish an assingment. yes i did cite it but just thanks

thx for the article guys.

Homework is good

I think homework is helpful AND harmful. Sometimes u can’t get sleep bc of homework but it helps u practice for school too so idk.

I agree with this Article. And does anyone know when this was published. I would like to know.

It was published FEb 19, 2019.

Studies have shown that homework improved student achievement in terms of improved grades, test results, and the likelihood to attend college.

i think homework can help kids but at the same time not help kids

This article is so out of touch with majority of homes it would be laughable if it wasn’t so incredibly sad.

There is no value to homework all it does is add stress to already stressed homes. Parents or adults magically having the time or energy to shepherd kids through homework is dome sort of 1950’s fantasy.

What lala land do these teachers live in?

Homework gives noting to the kid

Homework is Bad

homework is bad.

why do kids even have homework?

Comments are closed.

Latest from Bostonia

From bu hockey fan to entrepreneur to filmmaker, sports broadcaster and com alum tyler murray heads to the nba, three bu alums—alex cooper, howard stern, bill whitaker—land interviews kamala harris, a clear case of distortion, celebrate alumni weekend 2024 with these six community events, podcast looks at a forgotten chapter of the civil rights struggle, two bu alums take on same roles in leopoldstadt, huntington theatre company’s latest production, this sha alum handles fenway park’s celebrity artists, bu alum chompon boonnak runs mahaniyom, one of greater boston’s hottest thai restaurants, champion of indie films, china scholar merle goldman dies, cfa alum jonathan knight is head of games for the new york times, is our democracy at risk americans think so. bu experts talk about why—and the way forward, a commitment to early childhood education, reading list: alum bonnie hammer publishes 15 lies women are told at work —plus fiction, poetry, and short stories, one good deed: jason hurdich (cas’97) is uniting the deaf community, one cup at a time, space force general b. chance saltzman is a bu alum, feedback: readers weigh in on a bu superager, the passing of otto lerbinger, and alum’s book fat church, law alum steven m. wise, who fought for animal rights, dies, pups wearing custom-designed veterinary collars get star treatment in alum’s new coffee-table book.

More Homework Won't Make American Students Smarter

Reformers in the Progressive Era (from the 1890s to 1920s) depicted homework as a “sin” that deprived children of their playtime . Many critics voice similar concerns today.

Yet there are many parents who feel that from early on, children need to do homework if they are to succeed in an increasingly competitive academic culture. School administrators and policy makers have also weighed in, proposing various policies on homework .

So, does homework help or hinder kids?

For the last 10 years, my colleagues and I have been investigating international patterns in homework using databases like the Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) . If we step back from the heated debates about homework and look at how homework is used around the world, we find the highest homework loads are associated with countries that have lower incomes and higher social inequality.

Does homework result in academic success?

Let’s first look at the global trends on homework.

Undoubtedly, homework is a global phenomenon ; students from all 59 countries that participated in the 2007 Trends in Math and Science Study (TIMSS) reported getting homework. Worldwide, only less than 7 percent of fourth graders said they did no homework.

TIMSS is one of the few data sets that allow us to compare many nations on how much homework is given (and done). And the data show extreme variation.

For example, in some nations, like Algeria, Kuwait and Morocco, more than one in five fourth graders reported high levels of homework. In Japan, less than 3 percent of students indicated they did more than four hours of homework on a normal school night.

TIMSS data can also help to dispel some common stereotypes. For instance, in East Asia, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Japan–countries that had the top rankings on TIMSS average math achievement–reported rates of heavy homework that were below the international mean.

In the Netherlands, nearly one out of five fourth graders reported doing no homework on an average school night, even though Dutch fourth graders put their country in the top 10 in terms of average math scores in 2007.

Going by TIMSS data, the U.S. is neither “ A Nation at Rest” as some have claimed, nor a nation straining under excessive homework load . Fourth and eighth grade U.S. students fall in the middle of the 59 countries in the TIMSS data set, although only 12 percent of U.S. fourth graders reported high math homework loads compared to an international average of 21 percent.

So, is homework related to high academic success?

At a national level, the answer is clearly no. Worldwide, homework is not associated with high national levels of academic achievement .

But, the TIMSS can’t be used to determine if homework is actually helping or hurting academic performance overall , it can help us see how much homework students are doing, and what conditions are associated with higher national levels of homework.

We have typically found that the highest homework loads are associated with countries that have lower incomes and higher levels of social inequality–not hallmarks that most countries would want to emulate.

Impact of homework on kids

TIMSS data also show us how even elementary school kids are being burdened with large amounts of homework.

Almost 10 percent of fourth graders worldwide (one in 10 children) reported spending multiple hours on homework each night. Globally, one in five fourth graders report 30 minutes or more of homework in math three to four times a week.

These reports of large homework loads should worry parents, teachers and policymakers alike.

Empirical studies have linked excessive homework to sleep disruption , indicating a negative relationship between the amount of homework, perceived stress and physical health.

What constitutes excessive amounts of homework varies by age, and may also be affected by cultural or family expectations. Young adolescents in middle school, or teenagers in high school, can study for longer duration than elementary school children.

But for elementary school students, even 30 minutes of homework a night, if combined with other sources of academic stress, can have a negative impact . Researchers in China have linked homework of two or more hours per night with sleep disruption .

Even though some cultures may normalize long periods of studying for elementary age children, there is no evidence to support that this level of homework has clear academic benefits . Also, when parents and children conflict over homework, and strong negative emotions are created, homework can actually have a negative association with academic achievement.

Should there be “no homework” policies?

Administrators and policymakers have not been reluctant to wade into the debates on homework and to formulate policies . France’s president, Francois Hollande, even proposed that homework be banned because it may have inegaliatarian effects.

However, “zero-tolerance” homework policies for schools, or nations, are likely to create as many problems as they solve because of the wide variation of homework effects. Contrary to what Hollande said, research suggests that homework is not a likely source of social class differences in academic achievement .

Homework, in fact, is an important component of education for students in the middle and upper grades of schooling.

Policymakers and researchers should look more closely at the connection between poverty, inequality, and higher levels of homework. Rather than seeing homework as a “solution,” policymakers should question what facets of their educational system might impel students, teachers and parents to increase homework loads.

At the classroom level, in setting homework, teachers need to communicate with their peers and with parents to assure that the homework assigned overall for a grade is not burdensome, and that it is indeed having a positive effect.

Perhaps, teachers can opt for a more individualized approach to homework. If teachers are careful in selecting their assignments–weighing the student’s age, family situation and need for skill development–then homework can be tailored in ways that improve the chance of maximum positive impact for any given student.

I strongly suspect that when teachers face conditions such as pressure to meet arbitrary achievement goals, lack of planning time or little autonomy over curriculum, homework becomes an easy option to make up what could not be covered in class.

Whatever the reason, the fact is a significant percentage of elementary school children around the world are struggling with large homework loads. That alone could have long-term negative consequences for their academic success.

This article was originally published on The Conversation . Read the original article .

Home » Tips for Teachers » 7 Research-Based Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework: Academic Insights, Opposing Perspectives & Alternatives

7 Research-Based Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework: Academic Insights, Opposing Perspectives & Alternatives

In recent years, the question of why students should not have homework has become a topic of intense debate among educators, parents, and students themselves. This discussion stems from a growing body of research that challenges the traditional view of homework as an essential component of academic success. The notion that homework is an integral part of learning is being reevaluated in light of new findings about its effectiveness and impact on students’ overall well-being.

The push against homework is not just about the hours spent on completing assignments; it’s about rethinking the role of education in fostering the well-rounded development of young individuals. Critics argue that homework, particularly in excessive amounts, can lead to negative outcomes such as stress, burnout, and a diminished love for learning. Moreover, it often disproportionately affects students from disadvantaged backgrounds, exacerbating educational inequities. The debate also highlights the importance of allowing children to have enough free time for play, exploration, and family interaction, which are crucial for their social and emotional development.

Checking 13yo’s math homework & I have just one question. I can catch mistakes & help her correct. But what do kids do when their parent isn’t an Algebra teacher? Answer: They get frustrated. Quit. Get a bad grade. Think they aren’t good at math. How is homework fair??? — Jay Wamsted (@JayWamsted) March 24, 2022

As we delve into this discussion, we explore various facets of why reducing or even eliminating homework could be beneficial. We consider the research, weigh the pros and cons, and examine alternative approaches to traditional homework that can enhance learning without overburdening students.

Once you’ve finished this article, you’ll know:

- Insights from Teachers and Education Industry Experts →

- 7 Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework →

- Opposing Views on Homework Practices →

- Exploring Alternatives to Homework →

Insights from Teachers and Education Industry Experts: Diverse Perspectives on Homework

In the ongoing conversation about the role and impact of homework in education, the perspectives of those directly involved in the teaching process are invaluable. Teachers and education industry experts bring a wealth of experience and insights from the front lines of learning. Their viewpoints, shaped by years of interaction with students and a deep understanding of educational methodologies, offer a critical lens through which we can evaluate the effectiveness and necessity of homework in our current educational paradigm.

Check out this video featuring Courtney White, a high school language arts teacher who gained widespread attention for her explanation of why she chooses not to assign homework.

Here are the insights and opinions from various experts in the educational field on this topic:

“I teach 1st grade. I had parents ask for homework. I explained that I don’t give homework. Home time is family time. Time to play, cook, explore and spend time together. I do send books home, but there is no requirement or checklist for reading them. Read them, enjoy them, and return them when your child is ready for more. I explained that as a parent myself, I know they are busy—and what a waste of energy it is to sit and force their kids to do work at home—when they could use that time to form relationships and build a loving home. Something kids need more than a few math problems a week.” — Colleen S. , 1st grade teacher

“The lasting educational value of homework at that age is not proven. A kid says the times tables [at school] because he studied the times tables last night. But over a long period of time, a kid who is drilled on the times tables at school, rather than as homework, will also memorize their times tables. We are worried about young children and their social emotional learning. And that has to do with physical activity, it has to do with playing with peers, it has to do with family time. All of those are very important and can be removed by too much homework.” — David Bloomfield , education professor at Brooklyn College and the City University of New York graduate center

“Homework in primary school has an effect of around zero. In high school it’s larger. (…) Which is why we need to get it right. Not why we need to get rid of it. It’s one of those lower hanging fruit that we should be looking in our primary schools to say, ‘Is it really making a difference?’” — John Hattie , professor

”Many kids are working as many hours as their overscheduled parents and it is taking a toll – psychologically and in many other ways too. We see kids getting up hours before school starts just to get their homework done from the night before… While homework may give kids one more responsibility, it ignores the fact that kids do not need to grow up and become adults at ages 10 or 12. With schools cutting recess time or eliminating playgrounds, kids absorb every single stress there is, only on an even higher level. Their brains and bodies need time to be curious, have fun, be creative and just be a kid.” — Pat Wayman, teacher and CEO of HowtoLearn.com

7 Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework

Let’s delve into the reasons against assigning homework to students. Examining these arguments offers important perspectives on the wider educational and developmental consequences of homework practices.

1. Elevated Stress and Health Consequences

The ongoing debate about homework often focuses on its educational value, but a vital aspect that cannot be overlooked is the significant stress and health consequences it brings to students. In the context of American life, where approximately 70% of people report moderate or extreme stress due to various factors like mass shootings, healthcare affordability, discrimination, racism, sexual harassment, climate change, presidential elections, and the need to stay informed, the additional burden of homework further exacerbates this stress, particularly among students.

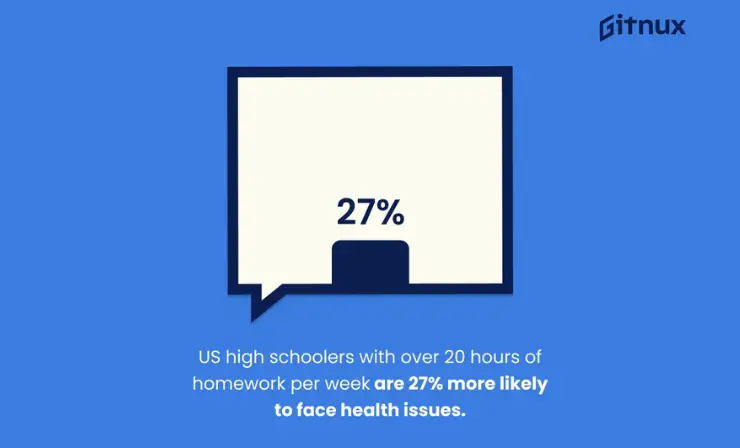

Key findings and statistics reveal a worrying trend:

- Overwhelming Student Stress: A staggering 72% of students report being often or always stressed over schoolwork, with a concerning 82% experiencing physical symptoms due to this stress.

- Serious Health Issues: Symptoms linked to homework stress include sleep deprivation, headaches, exhaustion, weight loss, and stomach problems.

- Sleep Deprivation: Despite the National Sleep Foundation recommending 8.5 to 9.25 hours of sleep for healthy adolescent development, students average just 6.80 hours of sleep on school nights. About 68% of students stated that schoolwork often or always prevented them from getting enough sleep, which is critical for their physical and mental health.

- Turning to Unhealthy Coping Mechanisms: Alarmingly, the pressure from excessive homework has led some students to turn to alcohol and drugs as a way to cope with stress.

This data paints a concerning picture. Students, already navigating a world filled with various stressors, find themselves further burdened by homework demands. The direct correlation between excessive homework and health issues indicates a need for reevaluation. The goal should be to ensure that homework if assigned, adds value to students’ learning experiences without compromising their health and well-being.

By addressing the issue of homework-related stress and health consequences, we can take a significant step toward creating a more nurturing and effective educational environment. This environment would not only prioritize academic achievement but also the overall well-being and happiness of students, preparing them for a balanced and healthy life both inside and outside the classroom.

2. Inequitable Impact and Socioeconomic Disparities

In the discourse surrounding educational equity, homework emerges as a factor exacerbating socioeconomic disparities, particularly affecting students from lower-income families and those with less supportive home environments. While homework is often justified as a means to raise academic standards and promote equity, its real-world impact tells a different story.

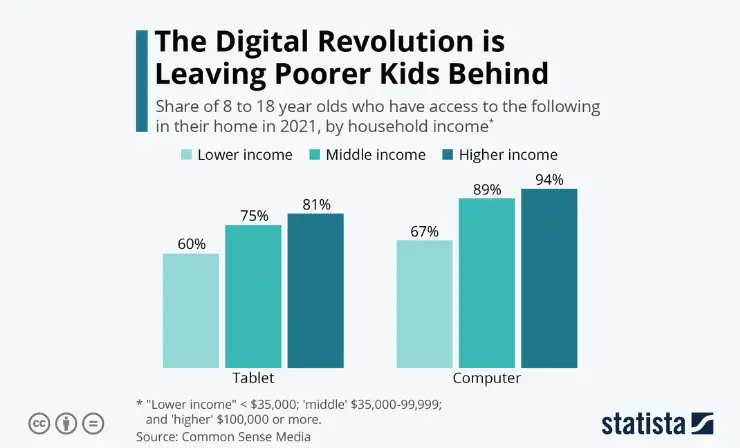

The inequitable burden of homework becomes starkly evident when considering the resources required to complete it, especially in the digital age. Homework today often necessitates a computer and internet access – resources not readily available to all students. This digital divide significantly disadvantages students from lower-income backgrounds, deepening the chasm between them and their more affluent peers.

Key points highlighting the disparities:

- Digital Inequity: Many students lack access to necessary technology for homework, with low-income families disproportionately affected.

- Impact of COVID-19: The pandemic exacerbated these disparities as education shifted online, revealing the extent of the digital divide.

- Educational Outcomes Tied to Income: A critical indicator of college success is linked more to family income levels than to rigorous academic preparation. Research indicates that while 77% of students from high-income families graduate from highly competitive colleges, only 9% from low-income families achieve the same . This disparity suggests that the pressure of heavy homework loads, rather than leveling the playing field, may actually hinder the chances of success for less affluent students.

Moreover, the approach to homework varies significantly across different types of schools. While some rigorous private and preparatory schools in both marginalized and affluent communities assign extreme levels of homework, many progressive schools focusing on holistic learning and self-actualization opt for no homework, yet achieve similar levels of college and career success. This contrast raises questions about the efficacy and necessity of heavy homework loads in achieving educational outcomes.

The issue of homework and its inequitable impact is not just an academic concern; it is a reflection of broader societal inequalities. By continuing practices that disproportionately burden students from less privileged backgrounds, the educational system inadvertently perpetuates the very disparities it seeks to overcome.

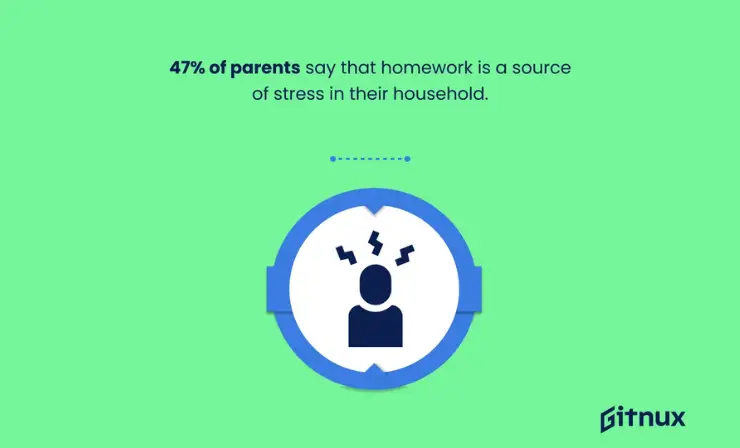

3. Negative Impact on Family Dynamics

Homework, a staple of the educational system, is often perceived as a necessary tool for academic reinforcement. However, its impact extends beyond the realm of academics, significantly affecting family dynamics. The negative repercussions of homework on the home environment have become increasingly evident, revealing a troubling pattern that can lead to conflict, mental health issues, and domestic friction.

A study conducted in 2015 involving 1,100 parents sheds light on the strain homework places on family relationships. The findings are telling:

- Increased Likelihood of Conflicts: Families where parents did not have a college degree were 200% more likely to experience fights over homework.

- Misinterpretations and Misunderstandings: Parents often misinterpret their children’s difficulties with homework as a lack of attention in school, leading to feelings of frustration and mistrust on both sides.

- Discriminatory Impact: The research concluded that the current approach to homework disproportionately affects children whose parents have lower educational backgrounds, speak English as a second language, or belong to lower-income groups.

The issue is not confined to specific demographics but is a widespread concern. Samantha Hulsman, a teacher featured in Education Week Teacher , shared her personal experience with the toll that homework can take on family time. She observed that a seemingly simple 30-minute assignment could escalate into a three-hour ordeal, causing stress and strife between parents and children. Hulsman’s insights challenge the traditional mindset about homework, highlighting a shift towards the need for skills such as collaboration and problem-solving over rote memorization of facts.

The need of the hour is to reassess the role and amount of homework assigned to students. It’s imperative to find a balance that facilitates learning and growth without compromising the well-being of the family unit. Such a reassessment would not only aid in reducing domestic conflicts but also contribute to a more supportive and nurturing environment for children’s overall development.

4. Consumption of Free Time

In recent years, a growing chorus of voices has raised concerns about the excessive burden of homework on students, emphasizing how it consumes their free time and impedes their overall well-being. The issue is not just the quantity of homework, but its encroachment on time that could be used for personal growth, relaxation, and family bonding.

Authors Sara Bennett and Nancy Kalish , in their book “The Case Against Homework,” offer an insightful window into the lives of families grappling with the demands of excessive homework. They share stories from numerous interviews conducted in the mid-2000s, highlighting the universal struggle faced by families across different demographics. A poignant account from a parent in Menlo Park, California, describes nightly sessions extending until 11 p.m., filled with stress and frustration, leading to a soured attitude towards school in both the child and the parent. This narrative is not isolated, as about one-third of the families interviewed expressed feeling crushed by the overwhelming workload.

Key points of concern:

- Excessive Time Commitment: Students, on average, spend over 6 hours in school each day, and homework adds significantly to this time, leaving little room for other activities.

- Impact on Extracurricular Activities: Homework infringes upon time for sports, music, art, and other enriching experiences, which are as crucial as academic courses.

- Stifling Creativity and Self-Discovery: The constant pressure of homework limits opportunities for students to explore their interests and learn new skills independently.

The National Education Association (NEA) and the National PTA (NPTA) recommend a “10 minutes of homework per grade level” standard, suggesting a more balanced approach. However, the reality often far exceeds this guideline, particularly for older students. The impact of this overreach is profound, affecting not just academic performance but also students’ attitudes toward school, their self-confidence, social skills, and overall quality of life.

Furthermore, the intense homework routine’s effectiveness is doubtful, as it can overwhelm students and detract from the joy of learning. Effective learning builds on prior knowledge in an engaging way, but excessive homework in a home setting may be irrelevant and uninteresting. The key challenge is balancing homework to enhance learning without overburdening students, allowing time for holistic growth and activities beyond academics. It’s crucial to reassess homework policies to support well-rounded development.

5. Challenges for Students with Learning Disabilities

Homework, a standard educational tool, poses unique challenges for students with learning disabilities, often leading to a frustrating and disheartening experience. These challenges go beyond the typical struggles faced by most students and can significantly impede their educational progress and emotional well-being.

Child psychologist Kenneth Barish’s insights in Psychology Today shed light on the complex relationship between homework and students with learning disabilities:

- Homework as a Painful Endeavor: For students with learning disabilities, completing homework can be likened to “running with a sprained ankle.” It’s a task that, while doable, is fraught with difficulty and discomfort.

- Misconceptions about Laziness: Often, children who struggle with homework are perceived as lazy. However, Barish emphasizes that these students are more likely to be frustrated, discouraged, or anxious rather than unmotivated.

- Limited Improvement in School Performance: The battles over homework rarely translate into significant improvement in school for these children, challenging the conventional notion of homework as universally beneficial.

These points highlight the need for a tailored approach to homework for students with learning disabilities. It’s crucial to recognize that the traditional homework model may not be the most effective or appropriate method for facilitating their learning. Instead, alternative strategies that accommodate their unique needs and learning styles should be considered.

In conclusion, the conventional homework paradigm needs reevaluation, particularly concerning students with learning disabilities. By understanding and addressing their unique challenges, educators can create a more inclusive and supportive educational environment. This approach not only aids in their academic growth but also nurtures their confidence and overall development, ensuring that they receive an equitable and empathetic educational experience.

6. Critique of Underlying Assumptions about Learning

The longstanding belief in the educational sphere that more homework automatically translates to more learning is increasingly being challenged. Critics argue that this assumption is not only flawed but also unsupported by solid evidence, questioning the efficacy of homework as an effective learning tool.

Alfie Kohn , a prominent critic of homework, aptly compares students to vending machines in this context, suggesting that the expectation of inserting an assignment and automatically getting out of learning is misguided. Kohn goes further, labeling homework as the “greatest single extinguisher of children’s curiosity.” This critique highlights a fundamental issue: the potential of homework to stifle the natural inquisitiveness and love for learning in children.

The lack of concrete evidence supporting the effectiveness of homework is evident in various studies:

- Marginal Effectiveness of Homework: A study involving 28,051 high school seniors found that the effectiveness of homework was marginal, and in some cases, it was counterproductive, leading to more academic problems than solutions.

- No Correlation with Academic Achievement: Research in “ National Differences, Global Similarities ” showed no correlation between homework and academic achievement in elementary students, and any positive correlation in middle or high school diminished with increasing homework loads.

- Increased Academic Pressure: The Teachers College Record published findings that homework adds to academic pressure and societal stress, exacerbating performance gaps between students from different socioeconomic backgrounds.

These findings bring to light several critical points:

- Quality Over Quantity: According to a recent article in Monitor on Psychology , experts concur that the quality of homework assignments, along with the quality of instruction, student motivation, and inherent ability, is more crucial for academic success than the quantity of homework.

- Counterproductive Nature of Excessive Homework: Excessive homework can lead to more academic challenges, particularly for students already facing pressures from other aspects of their lives.

- Societal Stress and Performance Gaps: Homework can intensify societal stress and widen the academic performance divide.

The emerging consensus from these studies suggests that the traditional approach to homework needs rethinking. Rather than focusing on the quantity of assignments, educators should consider the quality and relevance of homework, ensuring it truly contributes to learning and development. This reassessment is crucial for fostering an educational environment that nurtures curiosity and a love for learning, rather than extinguishing it.

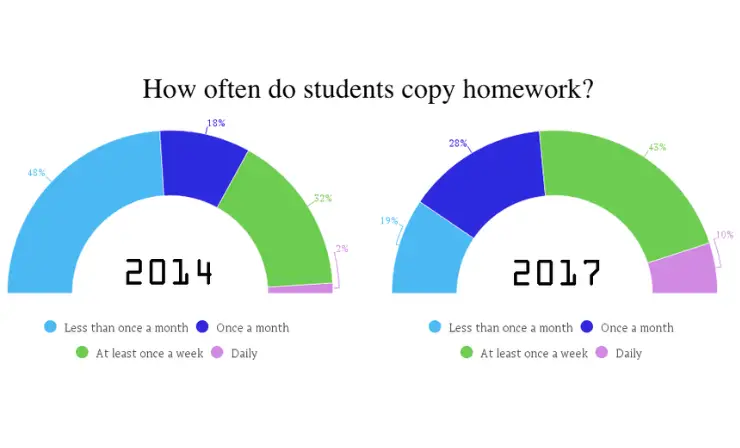

7. Issues with Homework Enforcement, Reliability, and Temptation to Cheat

In the academic realm, the enforcement of homework is a subject of ongoing debate, primarily due to its implications on student integrity and the true value of assignments. The challenges associated with homework enforcement often lead to unintended yet significant issues, such as cheating, copying, and a general undermining of educational values.

Key points highlighting enforcement challenges:

- Difficulty in Enforcing Completion: Ensuring that students complete their homework can be a complex task, and not completing homework does not always correlate with poor grades.

- Reliability of Homework Practice: The reliability of homework as a practice tool is undermined when students, either out of desperation or lack of understanding, choose shortcuts over genuine learning. This approach can lead to the opposite of the intended effect, especially when assignments are not well-aligned with the students’ learning levels or interests.

- Temptation to Cheat: The issue of cheating is particularly troubling. According to a report by The Chronicle of Higher Education , under the pressure of at-home assignments, many students turn to copying others’ work, plagiarizing, or using creative technological “hacks.” This tendency not only questions the integrity of the learning process but also reflects the extreme stress that homework can induce.

- Parental Involvement in Completion: As noted in The American Journal of Family Therapy , this raises concerns about the authenticity of the work submitted. When parents complete assignments for their children, it not only deprives the students of the opportunity to learn but also distorts the purpose of homework as a learning aid.

In conclusion, the challenges of homework enforcement present a complex problem that requires careful consideration. The focus should shift towards creating meaningful, manageable, and quality-driven assignments that encourage genuine learning and integrity, rather than overwhelming students and prompting counterproductive behaviors.

Addressing Opposing Views on Homework Practices

While opinions on homework policies are diverse, understanding different viewpoints is crucial. In the following sections, we will examine common arguments supporting homework assignments, along with counterarguments that offer alternative perspectives on this educational practice.

1. Improvement of Academic Performance

Homework is commonly perceived as a means to enhance academic performance, with the belief that it directly contributes to better grades and test scores. This view posits that through homework, students reinforce what they learn in class, leading to improved understanding and retention, which ultimately translates into higher academic achievement.

However, the question of why students should not have homework becomes pertinent when considering the complex relationship between homework and academic performance. Studies have indicated that excessive homework doesn’t necessarily equate to higher grades or test scores. Instead, too much homework can backfire, leading to stress and fatigue that adversely affect a student’s performance. Reuters highlights an intriguing correlation suggesting that physical activity may be more conducive to academic success than additional homework, underscoring the importance of a holistic approach to education that prioritizes both physical and mental well-being for enhanced academic outcomes.

2. Reinforcement of Learning

Homework is traditionally viewed as a tool to reinforce classroom learning, enabling students to practice and retain material. However, research suggests its effectiveness is ambiguous. In instances where homework is well-aligned with students’ abilities and classroom teachings, it can indeed be beneficial. Particularly for younger students , excessive homework can cause burnout and a loss of interest in learning, counteracting its intended purpose.

Furthermore, when homework surpasses a student’s capability, it may induce frustration and confusion rather than aid in learning. This challenges the notion that more homework invariably leads to better understanding and retention of educational content.

3. Development of Time Management Skills

Homework is often considered a crucial tool in helping students develop important life skills such as time management and organization. The idea is that by regularly completing assignments, students learn to allocate their time efficiently and organize their tasks effectively, skills that are invaluable in both academic and personal life.

However, the impact of homework on developing these skills is not always positive. For younger students, especially, an overwhelming amount of homework can be more of a hindrance than a help. Instead of fostering time management and organizational skills, an excessive workload often leads to stress and anxiety . These negative effects can impede the learning process and make it difficult for students to manage their time and tasks effectively, contradicting the original purpose of homework.

4. Preparation for Future Academic Challenges

Homework is often touted as a preparatory tool for future academic challenges that students will encounter in higher education and their professional lives. The argument is that by tackling homework, students build a foundation of knowledge and skills necessary for success in more advanced studies and in the workforce, fostering a sense of readiness and confidence.

Contrarily, an excessive homework load, especially from a young age, can have the opposite effect . It can instill a negative attitude towards education, dampening students’ enthusiasm and willingness to embrace future academic challenges. Overburdening students with homework risks disengagement and loss of interest, thereby defeating the purpose of preparing them for future challenges. Striking a balance in the amount and complexity of homework is crucial to maintaining student engagement and fostering a positive attitude towards ongoing learning.

5. Parental Involvement in Education

Homework often acts as a vital link connecting parents to their child’s educational journey, offering insights into the school’s curriculum and their child’s learning process. This involvement is key in fostering a supportive home environment and encouraging a collaborative relationship between parents and the school. When parents understand and engage with what their children are learning, it can significantly enhance the educational experience for the child.

However, the line between involvement and over-involvement is thin. When parents excessively intervene by completing their child’s homework, it can have adverse effects . Such actions not only diminish the educational value of homework but also rob children of the opportunity to develop problem-solving skills and independence. This over-involvement, coupled with disparities in parental ability to assist due to variations in time, knowledge, or resources, may lead to unequal educational outcomes, underlining the importance of a balanced approach to parental participation in homework.

Exploring Alternatives to Homework and Finding a Middle Ground

In the ongoing debate about the role of homework in education, it’s essential to consider viable alternatives and strategies to minimize its burden. While completely eliminating homework may not be feasible for all educators, there are several effective methods to reduce its impact and offer more engaging, student-friendly approaches to learning.

Alternatives to Traditional Homework

- Project-Based Learning: This method focuses on hands-on, long-term projects where students explore real-world problems. It encourages creativity, critical thinking, and collaborative skills, offering a more engaging and practical learning experience than traditional homework. For creative ideas on school projects, especially related to the solar system, be sure to explore our dedicated article on solar system projects .

- Flipped Classrooms: Here, students are introduced to new content through videos or reading materials at home and then use class time for interactive activities. This approach allows for more personalized and active learning during school hours.

- Reading for Pleasure: Encouraging students to read books of their choice can foster a love for reading and improve literacy skills without the pressure of traditional homework assignments. This approach is exemplified by Marion County, Florida , where public schools implemented a no-homework policy for elementary students. Instead, they are encouraged to read nightly for 20 minutes . Superintendent Heidi Maier’s decision was influenced by research showing that while homework offers minimal benefit to young students, regular reading significantly boosts their learning. For book recommendations tailored to middle school students, take a look at our specially curated article .

Ideas for Minimizing Homework

- Limiting Homework Quantity: Adhering to guidelines like the “ 10-minute rule ” (10 minutes of homework per grade level per night) can help ensure that homework does not become overwhelming.

- Quality Over Quantity: Focus on assigning meaningful homework that is directly relevant to what is being taught in class, ensuring it adds value to students’ learning.

- Homework Menus: Offering students a choice of assignments can cater to diverse learning styles and interests, making homework more engaging and personalized.

- Integrating Technology: Utilizing educational apps and online platforms can make homework more interactive and enjoyable, while also providing immediate feedback to students. To gain deeper insights into the role of technology in learning environments, explore our articles discussing the benefits of incorporating technology in classrooms and a comprehensive list of educational VR apps . These resources will provide you with valuable information on how technology can enhance the educational experience.

For teachers who are not ready to fully eliminate homework, these strategies offer a compromise, ensuring that homework supports rather than hinders student learning. By focusing on quality, relevance, and student engagement, educators can transform homework from a chore into a meaningful component of education that genuinely contributes to students’ academic growth and personal development. In this way, we can move towards a more balanced and student-centric approach to learning, both in and out of the classroom.

Useful Resources

- Is homework a good idea or not? by BBC

- The Great Homework Debate: What’s Getting Lost in the Hype

- Alternative Homework Ideas

The evidence and arguments presented in the discussion of why students should not have homework call for a significant shift in homework practices. It’s time for educators and policymakers to rethink and reformulate homework strategies, focusing on enhancing the quality, relevance, and balance of assignments. By doing so, we can create a more equitable, effective, and student-friendly educational environment that fosters learning, well-being, and holistic development.

- “Here’s what an education expert says about that viral ‘no-homework’ policy”, Insider

- “John Hattie on BBC Radio 4: Homework in primary school has an effect of zero”, Visible Learning

- HowtoLearn.com

- “Time Spent On Homework Statistics [Fresh Research]”, Gitnux

- “Stress in America”, American Psychological Association (APA)

- “Homework hurts high-achieving students, study says”, The Washington Post

- “National Sleep Foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations: final report”, National Library of Medicine

- “A multi-method exploratory study of stress, coping, and substance use among high school youth in private schools”, Frontiers

- “The Digital Revolution is Leaving Poorer Kids Behind”, Statista

- “The digital divide has left millions of school kids behind”, CNET

- “The Digital Divide: What It Is, and What’s Being Done to Close It”, Investopedia

- “COVID-19 exposed the digital divide. Here’s how we can close it”, World Economic Forum

- “PBS NewsHour: Biggest Predictor of College Success is Family Income”, America’s Promise Alliance

- “Homework and Family Stress: With Consideration of Parents’ Self Confidence, Educational Level, and Cultural Background”, Taylor & Francis Online

- “What Do You Mean My Kid Doesn’t Have Homework?”, EducationWeek

- “Excerpt From The Case Against Homework”, Penguin Random House Canada

- “How much homework is too much?”, neaToday

- “The Nation’s Report Card: A First Look: 2013 Mathematics and Reading”, National Center for Education Statistics

- “Battles Over Homework: Advice For Parents”, Psychology Today

- “How Homework Is Destroying Teens’ Health”, The Lion’s Roar

- “ Breaking the Homework Habit”, Education World

- “Testing a model of school learning: Direct and indirect effects on academic achievement”, ScienceDirect

- “National Differences, Global Similarities: World Culture and the Future of Schooling”, Stanford University Press

- “When school goes home: Some problems in the organization of homework”, APA PsycNet

- “Is homework a necessary evil?”, APA PsycNet

- “Epidemic of copying homework catalyzed by technology”, Redwood Bark

- “High-Tech Cheating Abounds, and Professors Bear Some Blame”, The Chronicle of Higher Education

- “Homework and Family Stress: With Consideration of Parents’ Self Confidence, Educational Level, and Cultural Background”, ResearchGate

- “Kids who get moving may also get better grades”, Reuters

- “Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement? A Synthesis of Research, 1987–2003”, SageJournals

- “Is it time to get rid of homework?”, USAToday

- “Stanford research shows pitfalls of homework”, Stanford

- “Florida school district bans homework, replaces it with daily reading”, USAToday

- “Encouraging Students to Read: Tips for High School Teachers”, wgu.edu

- Recent Posts

Simona Johnes is the visionary being the creation of our project. Johnes spent much of her career in the classroom working with students. And, after many years in the classroom, Johnes became a principal.

- Overview of 22 Low-Code Agencies for MVP, Web, or Mobile App Development - October 23, 2024

- Tips to Inspire Your Young Child to Pursue a Career in Nursing - July 24, 2024

- How Parents Can Advocate for Their Children’s Journey into Forensic Nursing - July 24, 2024

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Intelligence

How much does education really boost intelligence, a new analysis estimates the potential gain in iq points..

Posted June 25, 2018 | Reviewed by Devon Frye

- Why Education Is Important

- Take our ADHD Test

- Find a Child Therapist

The scientific case that an increase in education grows students’ cognitive abilities is not a new one . But figuring out exactly how much an additional stretch of schooling earns someone in terms of intelligence is a complicated challenge. One plausible reason more educated people tend to be more intelligent, after all, is that smarter youths are more likely to stay in school. Anyone who wants to ascertain whether an extra year of education has real cognitive benefits has to devise ways to account for that.

A new meta-analysis blends the results of 28 studies that all took measures to mitigate this problem. Based on data from more than 600,000 participants, all told, psychologists Stuart Ritchie and Elliot Tucker-Drob have arrived at a rough estimate of how much an added year of education lifted participants’ IQ scores, on average: between 1 and 5 points.

Understanding that result, however, requires some context. “This is a very sophisticated statistical analysis,” says psychologist Richard Haier , professor emeritus at the University of California, Irvine. “And yet there’s no doubt in my mind there will be a lot of misunderstanding about it.”

First, the estimates of IQ improvement depend on the type of study. In their analysis—the first to quantitatively distill the data on this question—Ritchie, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Edinburgh, and Tucker-Drob, an associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin, examined three types of study designs, producing different estimates for each one. They included studies in which:

- Cognitive tests were taken before participants differed in their degree of education (e.g., before some dropped out of high school) and again afterward, sometimes decades later.

- A policy change, such as an increase in the mandatory education level, resulted in some students staying in school for longer.

- Students who made an age cutoff to begin schooling were compared with students who had not.

“They all used a cognitive test of some kind,” Ritchie says—measuring vocabulary, memory , verbal and nonverbal reasoning, or other abilities—and the results in each category were aggregated. (The studies focused only on education after age 6.) The three study types respectively yielded estimated IQ increases of approximately one point, two points, and five points per additional year of schooling.

The results are “not really controversial within the field,” says Haier, who is editor of the journal Intelligence . (Ritchie and Tucker-Drob also serve on its editorial board). “It really just documents something that has kind of been suspected for years.”

It’s not clear yet exactly how education might increase IQ scores, or whether effects of schooling build up with each passing year. (So don’t assume that earning a four-year degree is going to pump up your IQ score by 20 points.) Further, IQ and general intelligence are not the same thing, as Haier points out; one is an imperfect proxy for the other. “IQ points are useful metrics,” he says, “but they’re not really a measure of intelligence directly.” Any effects of education on IQ may be related to improvements in particular skills, as opposed to a broader elevation of general cognitive ability.

There is also the open question of how much a gain of one or a few IQ points—modest, given that an average IQ score is 100—matters for real-world outcomes.

“If you or I got knocked on the head and lost two IQ points, it wouldn't make a huge difference,” Ritchie says. But previous studies show a relationship between IQ and measures such as job efficiency and performance, he notes. While more research would be required to find out whether the sort of IQ gains suggested by the latest report lead to improvements on such outcomes, Ritchie says, it’s possible that “if everyone was two IQ points higher, you’d have just a little bit higher efficiency, fewer accidents.” On a societal scale, “that could end up saving quite a lot of money.”

Another potential takeaway, as psychologist (and PT blogger) Jonathan Wai has articulated , is that if a whole year’s worth of studying raises IQ by just a couple of points, shorter-term cognitive training programs—the effectiveness of which has been disputed —are unlikely to have much practical impact.

The new report does reaffirm the conclusion of psychologists that intelligence—despite being heavily influenced by genetics —is subject to change. The public may not yet be on the same page, according to Ritchie, despite previous research reviews in tune with his paper. “I think the idea that IQ is completely set in stone is still hanging around,” he says. “I think, in this case, we have some of the strongest evidence that it’s not.”

LinkedIn Image Credit: Gorodenkoff/Shutterstock

Ritchie, S. J., & Tucker-Drob, E. M. (2018). How Much Does Education Improve Intelligence? A Meta-Analysis. Psychological Science, 095679761877425. doi:10.1177/0956797618774253

Matt Huston is a Commissioning Editor at Aeon Media. He is a former Senior Editor at Psychology Today .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- svg]:fill-accent-900 [&>svg]:stroke-accent-900">

Kids are onto something: Homework might actually be bad

By Stan Horaczek

Posted on Sep 23, 2021 8:00 AM EDT

When you’re a kid, your stance on homework is generally pretty simple: It’s the worst. When it comes to educators, parents, and school administrators, however, the topic gets a lot more complicated.

Collective educational enthusiasm toward homework has ebbed and flowed throughout the 20th century in the US. School districts began abolishing homework in the ‘30s and ‘40s, only for it to come roaring back as the space race kicked off in the late ‘50s and drove a desire for sharper math and science skills. It fell out of fashion again during the Vietnam War era before it came back strong in the ‘80s .

As the country mostly transitions back to full-time, in-person schooling, the available research on homework and its efficacy is still messy at best.

How much homework are kids doing?

There’s a fundamental issue at the very start of this discussion: we’re not entirely sure how much homework kids are actually doing. A 2019 Pew survey found that teens were spending considerably more time doing schoolwork at home than they had in the past—an hour a day, on average, compared to 44 minutes a decade ago and just 30 in the mid-1990s.

But other data disagrees , instead suggesting that homework expansion primarily affects children in lower grades. But it’s worth noting that such arguments typically refer to data from more than a decade ago.

How much homework are kids supposed to be doing?

Many schools subscribe to a “rule of thumb” that suggests students should get 10 minutes of homework for each grade level. So, first graders should get just 10 minutes of work to do at home while high schoolers should be cracking the books for up to two hours each night.

This once served as the official guidance for educators from the National Education Association, as well as the National PTA. It also serves as the official homework policy for many school districts, even though the NEA’s outline of the policy now leads to an error page . The National PTA also now relies on a less-specific resolution on homework which encourages districts and educators to focus on “quality over quantity.”

The PTA’s resolution effectively sums up the current dominant perspective on homework. “The National PTA and its constituent associations advocate that teachers, schools, and districts follow evidence-based guidelines regarding the use of homework assignments and its impact on children’s lives and family interactions.”