The Geography of Transport Systems

The spatial organization of transportation and mobility

5.5 – Air Transport

Authors: dr. john bowen and dr. jean-paul rodrigue.

Air transportation is the mobility of passengers and freight by any conveyance that can sustain controlled flight.

CHAPTER CONTENTS

1. The Rise of Air Transportation

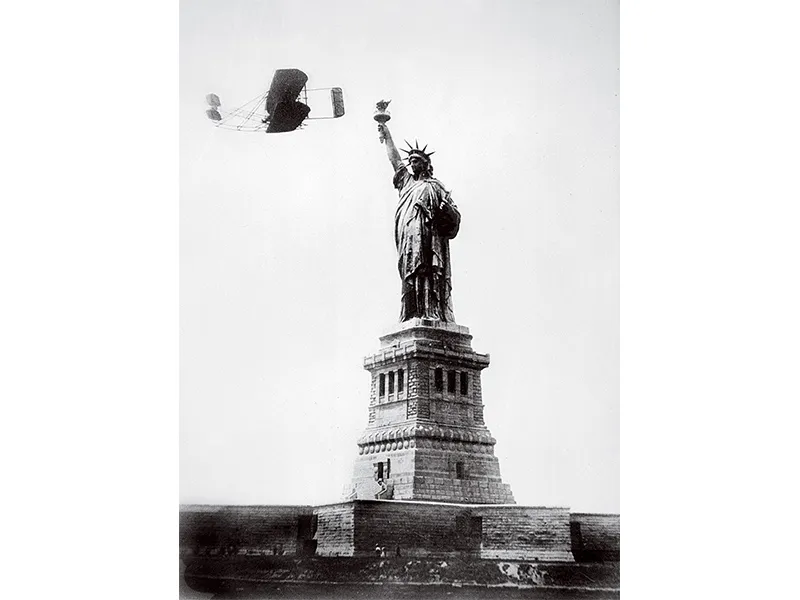

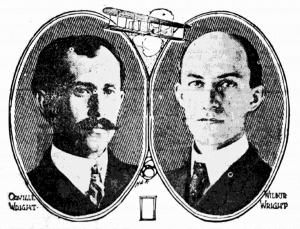

Air transportation was slow to take off after the Wright Brothers breakthrough at Kitty Hawk in 1903. More than a decade passed before the first faltering efforts to launch scheduled passenger services. On January 1, 1914, the world’s inaugural scheduled flight with a paying passenger hopped across the bay separating Tampa and St. Petersburg, Florida.

In its earliest years, the airline industry had a symbiotic relationship with military aviation. World War I, which began just months after that first flight from Tampa, provided a powerful spur to the development of commercial aviation as air power began to be used strategically, and better aircraft were quickly introduced. The war left a legacy of thousands of unemployed pilots and surplus aircraft, along with an appreciation for the future significance of aviation.

After the war, civilian airliners improved rapidly. The non-stop crossing of the North Atlantic in 1927 was a key event as the range and navigational capabilities of the emerging air transport system were tested. For instance, the 8-12 passenger Dutch-built Fokker Trimotor, the most popular airliner in the early interwar years, had a top speed of 170 kilometers per hour and a range of 1,100 kilometers, which is less than the distance between Amsterdam and Rome. By the eve of World War II, airlines worldwide were adopting the USA-built Douglas DC-3 with a capacity of 28 passengers, a speed of 310 kilometers per hour, and a range of more than 2,400 kilometers nonstop, able to fly across the US with just three stops. The DC-3 made its maiden commercial flight in 1936 between New York and Chicago, a vital business route highlighting the commercial significance of fast-changing technology.

Governments supported the emergence of the airline industry through ownership or subsidies. In Europe, governments established new passenger airlines, while on the other side of the Atlantic, the American government heavily subsidized airmail . Airmail was one of the earliest commercially relevant applications of air transportation because it helped accelerate monetary transactions and tie together far-flung enterprises, facilitating the emergence of continental and intercontinental enterprises. US airmail subsidies also fostered the emergence of the first major US passenger airlines.

By the eve of World War II, air travel was quite literally taking off. In the US, for instance, the number of passengers grew fivefold from 462,000 to 1,900,000 between 1934 and 1939. Still, aviation remained far beyond the means of most travelers, especially for long-haul routes. For instance, in 1936, Pan American World Airways launched services across the Pacific with a roundtrip fare of $1,438 (about $26,900 in 2020 dollars) between San Francisco and Manila. As in this example, many of the long-haul air services were to colonies and dependencies. Only the elite or government officials could afford such early intercontinental routes .

Yet war again catalyzed the growth of air transportation since airpower became an ever more crucial element of military operations. New airports, vast numbers of trained pilots, great strides in jet aviation, and other aviation-related innovations, including radar, were among the legacies of World War II. Boosted by such developments and the broader economic boom that followed the war, air transportation finally became the dominant mode of long-haul passenger travel in developed countries. By the 1950s, air travel had become more widely advertised, and standardized fare structures were emerging. In 1956, more people traveled on intercity routes by air than by Pullman car (sleeper) and coach class trains combined in the US. For the first time in 1958, airlines carried more passengers than ocean liners across the Atlantic.

The speed advantage for aviation grew with the advent of jet travel in the mid-1950s. In October 1958, the Boeing 707 took its maiden commercial flight with a Pan American World Airways route linking New York and Paris, with a refueling stop in Gander, Newfoundland. The B707 was not the first jetliner, but it was the first successful one. The B707 and other early jets, including the Douglas DC-8, doubled the speed of air transportation and radically increased airline productivity, enabling fares to fall . Just a few years after the B707’s debut, airlines had extended jet service to most major world markets. The technical benefits of jet planes, such as better ranges, changed the structure of air networks as airlines bypassed airports that conventionally had acted as gateways because of refueling stops. This was the case for Gander in Canada and Recife in Brazil for transatlantic flights.

Jet transportation facilitated the extension of the linkages between people and places . For example, through the mid-1950s, all major league baseball teams in the US were located in the Manufacturing Belt, situated no more than an overnight rail journey apart from one another to permit closely packed schedules. The speed and ultimately lower cost of air transportation freed teams to move to the untapped markets of the Sunbelt. By the mid-1960s, half a dozen teams were strung out across the South and West, complementing and competing against those that remained in the Frostbelt.

In the years since the beginning of the Jet Age, commercial aircraft have advanced markedly in capacity and range. Just 12 years after the debut of the 134-seat (in a typical two-class configuration) B707, the 366-seat (in a typical three-class configuration) B747 made its maiden flight. The economies of scale fostered by the 747 and other wide-body jets helped to push real airfares downward , thereby democratizing aviation beyond the so-called “Jet Set”. Like the B707, the B747 premiered on a transatlantic route from New York City. However, the B747, particularly the longer-range B747-400 version introduced in the late 1980s, has been nicknamed the “Pacific Airliner” because of its singular significance in drawing Asia closer to the rest of the world and because Asia-Pacific airlines have been major B747 customers .

By the 2010s, the majority of the B747s were being retired and replaced by longer-range and more fuel-efficient twin-engine aircraft such as the B777, the A330, the B787, and the A350. On transpacific routes, the 787, for instance, has a fuel economy of about 39 passenger-kilometers per liter of jet fuel versus about 23 passenger-kilometers per liter for the Boeing 747-400ER. The triumph of widebody twinjets is most evident in the transatlantic and transpacific markets, including the introduction of the A380 in 2007 to develop a niche of a high-capacity aircraft servicing long hauls between major airports.

Air transportation is now overwhelmingly dominant in transcontinental and intercontinental travel and has become more competitive for shorter trips in many regional markets. Low-cost carriers (LCCs) have been instrumental in extending aviation’s reach to short-haul markets. The pioneering LCC, Southwest Airlines, sought to make flying cheaper than driving on the first markets it served in the early 1970s: the Texas “Golden Triangle” linking Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio. Since then, LCCs have proliferated across developed markets and, more recently, in emerging markets. In developing countries, the ascent of LCCs has been partly fueled by the poor quality of land transportation, making air travel an attractive option for national inter-city routes.

Interestingly, since their introduction in the late 1950s, commercial jets have not improved much in terms of speed apart from a small fleet of supersonic but commercially unsuccessful Concorde jets (which flew on a handful of transatlantic routes between 1976 and 2003). Since the end of Concorde services, the fastest airliners in regular use have had cruising speeds about as fast as the B707s of the early 1960s. However, introducing long-haul aircraft has produced new rounds of time-space convergence. For instance, in 2018, twenty US cities had nonstop services to at least one destination in Asia, up from 13 US cities in 1998. Boston had nonstop links to Tokyo, Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong in 2018, whereas two decades earlier, all those markets would have required a time-consuming connection at a larger hub. Meanwhile, there have been repeated attempts to launch new supersonic airliners. In 2021, United Airlines placed orders for 15 aircraft from Boom Supersonic. The new jets, each seating 65 to 80 passengers and cruising at Mach 1.7, will begin flying in 2029 if all goes according to plan.

Perhaps the most significant improvement in aviation is the reduced risks of accidents . If civil aviation had had the same accident rate per million departures as in the early 1960s, there would have been the equivalent of about three fatal accidents somewhere in the world per day in 2018. Instead, there were nine fatal accidents worldwide for the whole year .

The world’s busiest air routes are mainly short-range sections between cities less than 1,000 km apart, with many of these city pairs found in emerging markets. More generally, short-haul flights predominate despite the expansion of long-haul flights and the increased globalization of the economy. Importantly for the world as a whole, about 59% of airline seats were on domestic flights in 2018, and for larger countries, the share was even higher, such as 88% in China.

Air transportation’s share of world trade in goods is less than 1% measured by weight but more than 35% by value . Typically, air transportation is most important for time-sensitive, valuable, or perishable freight carried over long distances. Air cargo has been central in “just-in-time” production and distribution strategies with low inventory levels, such as for Apple iPhones. Air cargo is also vital in emergencies when the fast delivery of supplies prevails over cost issues. In the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, air cargo carriers were crucial in rushing ventilators and other equipment worldwide. Later in the pandemic, the same carriers helped speed the distribution of vaccines and supported the increasing demand for goods due to online purchases.

2. Civil Aviation and Activity Spaces

Air transportation has transformed society at scales ranging from the local to the global. Aviation has made economic and social activities in many parts of the world faster, more interconnected, varied, and more affluent . Still, those gains have come with externalities such as congestion and environmental challenges.

a. The acceleration of the material world

As the fastest mode, air transportation has been associated with the speeding up of daily life . This effect is most apparent in the astonishing delivery times for goods ordered online from sites such as Amazon.com. In 2019, Amazon offered two-day deliveries to all of the United States for millions of goods and next-day delivery for a narrower range of goods. The speed of the company’s deliveries depended largely on the multiplicity of distribution centers Amazon operated across the country, positioning many goods close to consumers. Still, air cargo has also been vital in rushing goods from global suppliers to distribution centers and consumers. In 2016, Amazon began flying leased aircraft as Amazon Air in the United States, with nationwide flights. The surge in e-commerce during the pandemic propelled the expansion of Amazon Air to a fleet size of 96 aircraft by 2022, a small number of which now operate on routes within Europe.

Passengers move at faster speeds as well. The supersonic Concorde once advertised its service with the slogan “Arrive before you leave”, highlighting the fact that for westbound flights such as London – New York, the local time on arrival (in New York) would be earlier than at departure (in London). As noted above, the Concorde was grounded in 2003. Still, the multiplication of nonstop services means that even at conventional jet speeds (which are about 80 percent the speed of sound), the world is smaller for passengers; the number of unique city pairs served by commercial airlines grew to 22,000 in 2019, about twice the number of twenty years earlier.

The speed of human transportation has changed how people interact in ways that are both positive and negative. For instance, until the advent of low-cost air transportation, the principal means of traveling between Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi was a 33- to 36-hour rail journey on the Reunification Express or a similarly tedious bus journey. Now, for those who can afford to fly (low-cost carriers have broadened that population), the cities are just 2 hours apart. The route has become among the most densely trafficked in the world, with 60 flights per day each way in 2018. The result has been an improvement in the lives of traders, bureaucrats, students, tourists, and others traveling between Vietnam’s two largest cities, and the same has occurred in countless other city pairs.

On the other hand, the acceleration of passenger flows around the world has also sped up the diffusion of infectious diseases . In late 2002, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), for instance, began spreading slowly within southern China. Still, within days of reaching Hong Kong in February 2003, the disease was transmitted to Canada, Vietnam, the United States, and the Philippines. Direct nonstop services were an important factor behind a diffusion pattern that may, at first glance, appear random. Ultimately, cases were reported in more than two dozen countries over a matter of weeks, with airports becoming the key frontiers in trying to limit the spread of SARS. Before aviation became widespread, the sheer size of the world afforded a degree of protection from the development of pandemics. But the world is, at least measured in terms of time, much smaller than in the past.

That lesson was repeated on a much larger scale during the COVID-19 pandemic . In early 2020, the coronavirus epidemic first forced the shutdown of large segments of the Chinese air transport system, including international air services to Chinese cities. As the disease spread, travel bans cascaded across the planet, precipitating the worst crisis in the history of the airline industry . In the United States, passengers cleared at Transportation Security Administration (TSA) checkpoints reached a nadir of 87,500 on April 13, 2020 , just 4 percent of the level on the same date a year earlier. By June 2021, with vaccination increasingly widespread in the United States, the number of passengers processed daily by the TSA reached 70% of pre-pandemic levels, with domestic flights the main driver. By June 2022, this traffic level was at 95%, with the demand considered to have recovered to pre-pandemic levels after a two-year hiatus. Still, international travel lagged mainly due to entry restrictions involving vaccine certificates, testing before arrival, and quarantine requirements. By mid-2022, these restrictions were eased for major destinations in North America and Europe, allowing for the resumption of segments of long-distance international air travel.

b. An interconnected world

At any moment in 2018, an estimated 1.4 million people were airborne on commercial airline flights worldwide. Most were on short-haul flights linking nearby cities within the same country, as evidenced by the most densely trafficked sector, the 454-kilometer hop from Seoul to the resort island of Jeju, off South Korea’s southern coast. At the regional scale, frequent flights have amplified the political and economic integration of regions such as the European Union (EU) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). In Europe, the phrase “easyJet Generation” refers to young people who have grown up in a region where cheap aviation and porous borders have permitted unprecedented mobility.

At the global scale, increasingly long-haul nonstop services (up to 18 hours in duration ) are both a response and a driver for globalization . Most of the nodes for such flights are world cities , the command-and-control centers of the global economy rank among the best-connected cities in the global airline networks. Yet the links between globalization and the airline industry extend far beyond the main hubs. Manufacturers, especially those producing high-value electronics, rely heavily on air transport to tie together spatially disaggregated operations. For example, by 2019, Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan Province in China and the largest production base for Apple iPhones, was linked by numerous freighter aircraft flights daily to global markets, including a nonstop 747-freighter flight by Cargolux to Luxembourg.

In addition to the trade networks established by multinational corporations, there are also extensive social networks created by migrants involving recurring air travel. For instance, in 1998, Ethiopian Airlines launched services to Washington, DC, the carrier’s first destination in the United States and not coincidentally home to the largest community of Ethiopians outside Africa. The flow of people between Ethiopia and Washington, DC, is one strand in the larger tapestry of global connections expedited by air transportation.

c. A kaleidoscope of experience

Cheap air transport has enlarged the geographic scope of everyday life and, in so doing, has enriched the lives of many with unprecedented variety. Take first the diversity of goods. By one common measure, the United States imported more than four times the variety of goods in 2018 as in 1972. Much of the increase was attributable to the sharp reduction in transportation costs through containerized maritime shipping, but lower-cost air cargo has also played a role. Many perishables, for instance, such as Valentine’s Day roses bound from Kenya to Europe or Colombia to the United States and fresh tuna shipped from around the world to the fish markets in Japan, move exclusively by air. These markets largely did not exist a few decades ago.

Efficient and affordable air cargo has contributed to changes in diet by making available products in seasons during which they would not be available, to changes in retailing, and correspondingly to changes in manufacturing. Examples abound, such as fresh produce grown in the southern hemisphere available in the northern hemisphere during winter (a phenomenon sometimes referred to as permanent global summertime ), at least for affluent consumers.

Likewise, air transport has catalyzed the emergence of an ever-greater variety of tourist destinations . The markets with the fastest growth rely overwhelmingly on arrivals by air from major source tourist markets such as the United States, Europe, and China. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly curtailed air tourism, particularly at the international level, but by 2022, activities were returning to normalcy, and pent-up demand accelerated the recovery of air tourism.

d. The ascent of affluence

Air traffic is correlated with per capita income, but the relationship is interdependent. More affluent populations can more easily afford what is usually the most expensive mode, but aviation has also been catalytic to economic growth.

In 2019, airlines flew approximately 4.5 billion passengers. The total volume of air passengers equaled nearly 60 percent of the global population. Of course, a much smaller share are actually air travelers, as individuals who use air transportation usually do so several times per year. Therefore, the propensity to fly is highly uneven, as observed in the passenger and freight markets. Flights originating in North America and Europe accounted for 47 percent of airline seat capacity in 2018. However, that share has been declining with faster growth in other regions of the world. For instance, flights from China accounted for 14 percent of seat capacity in 2018, up from 3 percent in 1998.

Both passenger and cargo traffic have grown rapidly as higher incomes translate into higher values for time and a stronger preference for what is the fastest mode. In fact, air passenger and air cargo traffic have outpaced the growth of the broader global economy .

At the same time, lower transportation costs, in terms of time and money, have encouraged faster income growth. The economic impact of air transportation is most strongly pronounced near air hubs, but the catalytic effect of air accessibility extends across the economy. Whole sectors are strongly dependent on aviation. Logistics, advanced business services such as consulting and advertising, and tourism are among the industries for which air accessibility is vital. It is no coincidence, for instance, that all six major Disney theme parks are located near one of the world’s busiest airports. In 2017, passenger volumes at Orlando International Airport were more than 500 times larger than they had been the year before Disneyworld opened (1971), and what was once a medium-sized Florida city had nonstop links to cities across the United States and Canada, Latin America, Europe, and the Middle East. Disney’s other parks include Disneyland near Los Angeles International Airport, Disneyland Paris near Paris-Charles de Gaulle, Tokyo Disneyland near Tokyo-Haneda, Hong Kong Disneyland, which shares Lantau island with the most expensive airport in history , and Shanghai Disney Resort located just a few kilometers south of the city’s main airport.

e. The high costs of aviation

Yet, the huge increase in traffic in Orlando and the more modest increase globally have not been cost-free. In particular, aviation externalities have risen with traffic volumes. The air transport sector accounts for about 3.5 percent of anthropogenic climate change, but its share is expected to climb towards the mid-century. Aviation is heavily dependent on fossil fuels and is likely to remain so after other modes have transitioned to more environmentally friendly fuel sources. Some airlines have experimented with biofuels, but their impact remains marginal so far. Between 2011 and 2019, about 175,000 flights were partly powered by biofuels, but in 2019, more than 100,000 flights per day were powered solely by conventional fuels. A landmark was reached in 2021 when a test flight between Chicago and Washington, DC, ran exclusively on biofuels. In 2023, this was the case for the first transatlantic flight.

Battery-electric aircraft are another avenue to ease the sector’s global climate change impacts. Air taxis using this technology are expected to launch as soon as 2024, but the aircraft being developed are small in their capacity (about five passengers) and range (about 250 kilometers). Airships , which might be suitable for freight transportation in remote areas, still comprise another area of innovation.

Aviation also has significant impacts at the local level, including emissions of nitrogen oxides and particulate matter. As with greenhouse gasses, however, growth in emissions (at least when measured per passenger-kilometer) has been stemmed by rapid advances in aviation technology, especially improvements in engine efficiency. The average fuel burn per passenger-kilometer by air transportation fell by 45 percent between 1968 and 2014, and the introduction of a new generation of jet engines portends further gains.

The most apparent externality at the local scale is aircraft noise , and technology has brought impressive gains. For instance, engine manufacturer Pratt & Whitney claims up to a 75 percent reduction in the noise footprint (i.e. the area near a runway affected by high noise levels) for its newest large jet engine compared to similar-sized jets operated with an earlier generation of engines. Still, the huge increase in traffic volumes (at least before the COVID-19 pandemic) partly offsets this and other technical improvements in aviation.

3. The Geography of Airline Networks

Theoretically, air transport enjoys greater freedom of route choice than most other modes. Airline routes span oceans, the highest mountain chains, the most forbidding deserts, and other physical barriers to surface transport. Yet, while it is true that the mode is less restricted than land transport to specific rights of way, it is nevertheless more constrained than might be supposed.

a. Structuring factors

Weather events such as snowstorms and thunderstorms can temporarily create disruptions that cascade through hub-and-spoke networks . Volcanic eruptions may also impede air travel by releasing ash into the atmosphere, which can damage and even shut down turbofan engines. Fear of such calamities forced the closing down of the airspace in much of Europe as well as the North Atlantic for nearly a week following an April 2010 volcanic eruption in Iceland. Meanwhile, on a more regular basis, aircraft seek to exploit (or avoid) upper atmospheric winds, particularly the jet stream , to enhance speed and reduce fuel consumption.

Yet the limitations that structure air transportation are mainly human creations , especially internationally. The Chicago Convention of 1944 established the basic geopolitical guidelines of international air operations, which became known as the freedoms of the air . First (right to overfly) and second (right for a technical stop), freedom rights are almost automatically exchanged among countries. The United States, which emerged from World War II with by far the strongest airline industry in the world, had wanted third and fourth freedom rights (the right to drop off passengers and cargo and the right to pick up passengers and cargo, respectively, in another country) to be freely exchanged as well. Instead, these and other rights have been the subject of hundreds of carefully negotiated bilateral air services agreements (ASAs). In an ASA, each side can specify which airlines can serve which cities with what size equipment and at what frequencies. ASAs often include provisions regulating fares and revenue sharing among the airlines serving a particular international route.

Other constraints on the geography of air services stem from safety and national security concerns . To limit opportunities for midair collisions, air traffic is channeled along specific corridors so that only a relatively small portion of the sky is in use. Jet Route 80, for example, links Coaldale, Nevada, and Bellaire, Ohio, and accommodates many transcontinental city pairs as well as some shorter haul sectors such as Indianapolis-Denver. Meanwhile, airlines within China face widespread capacity constraints because the People’s Liberation Army controls four-fifths of the country’s airspace and prioritizes military flights over passenger use.

Strategic and political factors also influence route choice over larger scales. The Cold War imposed numerous airspace constraints, preventing the use of polar air routes . The opening of the Siberian airspace to Western airlines in the 1990s permitted more direct routes between cities like London and Tokyo or New York and Hong Kong. However, in 2022, the Russian invasion of Ukraine resulted in the closing of the Russian airspace for most Western airlines, forcing international flights to detour along North America/Asia and Europe/Asia routes. For instance, Lufthansa’s flight between Frankfurt and Beijing detoured to the south of Russia (through Romania, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia), adding hundreds of kilometers and more than an hour of flying time. In turn, Russian airlines were excluded from the airspace of most Western countries. Meanwhile, there has been some progress towards opening up airspace elsewhere in the world. In 2020, some Arab governments opened their airspace to Israeli airlines as part of a broader peace initiative.

b. Liberalization of air travel

These instances of government intervention in airline networks run contrary to the broader trajectory of airline industry liberalization (a term that refers to deregulation and privatization). Since the 1970s, dozens of airlines around the world have been at least partially privatized, meaning that they are now owned by private investors instead of governments. Many airline markets have been deregulated, meaning there are fewer regulations on fares, routes, and other aspects of operations.

In the United States, the Air Deregulation Act of 1978 opened the industry to competition. The results were significant. Once hallowed names, like TWA, Pan Am, and Braniff, sank into bankruptcy, and many new players emerged . Most lasted only briefly, but some have had a more profound, enduring effect on the industry and air transportation. For instance, Southwest Airlines could only serve intra-Texas markets until deregulation freed the low-cost carrier to spread nationwide and beyond.

In Europe, deregulation advanced in a series of stages, culminating in 1997 with the opening of the European market to all European carriers. For instance, the Irish LCC Ryanair operates dozens of bases outside Ireland, its headquarters country, and most of its routes never touch Ireland.

Liberalization has also spread to emerging markets, with a transformative effect in places as different as Indonesia, India, and Brazil. In all these markets, state-owned flag carriers have lost market share to nimbler, privately owned airlines, often including LCCs. The enormous Chinese market has also been partially deregulated, and its leading airlines, while predominantly state-owned, have varying degrees of private ownership.

Meanwhile, in international markets, an important trend in the past few decades has been the proliferation of Open Skies agreements . These agreements remove most restrictions on the number of carriers and routes they may fly between signatory countries. By 2021, the United States alone had Open Skies agreements with more than 128 countries. Perhaps the most important Open Skies agreement links the European Union and the United States. Signed in 2007, the agreement permits any European carrier to fly to any city in the United States and vice versa. It makes it easier for investors from one side of the Atlantic to invest in airlines on the other side and facilitates collaboration among carriers integrated into airline alliances.

Liberalization has fueled the growth of aviation and made the world’s airline networks far more dynamic. Airlines have greater freedom to fly where and when they see commercial potential. For instance, under regulation by the US Civil Aeronautics Board, United Airlines was allowed to add only one city to its network between 1961 and 1978. By contrast, between 1978 and 2018, the airline’s network grew from 93 cities (almost all in the US) to 342 cities worldwide.

Liberalization has not been a one-way street, however. There have been numerous instances of governments reasserting their power in the industry, and the COVID-19 pandemic was an event likely to incite further interventions.

c. Aircraft technology and airline networks

In time, air transportation networks evolved to become increasingly complex, a trend that goes on par with the improvements in the technical capabilities of aircraft, as well as their specialization to service-specific markets. Three major categories of passenger jet planes may be recognized, each servicing a specific air transport market :

- Regional market (Short range/haul aircraft) . This market usually involves short flights lasting anywhere between 30 minutes and 2 hours, which means that they can fly between 6 and 10 legs a day. Embraer’s older ERJs and new E-Jets are examples of planes with relatively small capacities (fewer than 150 passengers) that travel short distances. Regional jets (RJs) like these serve smaller markets and feed hub airports on routes such as Appleton, Wisconsin, to Chicago or Maputo, Mozambique, to Johannesburg. RJs also provide high-frequency point-to-point services between large city pairs.

- Regional and international markets (Medium range/haul aircraft) . This market involves flights between 1 and 4 hours in duration, but longer flights of 5 to 6 hours are also possible, which means 2 to 5 legs per day. The Airbus A320 and Boeing B737 are very flexible aircraft that can be efficiently deployed on short hops but also on transcontinental routes. From New York, all of North America can be serviced by the latest versions of the A320 and B737. This range can also be applied to the European continent, South America, East Asia, and Africa for corresponding market areas. These narrow-body jets are the workhorses of LCCs, including Southwest Airlines, the largest 737 operator.

- International and intercontinental markets (Long-range/haul aircraft) . This market involves flights of 7 or more hours, with 12 hours considered ultra-long-range, which means two legs or fewer per day. The North Atlantic is considered in the lower range of this category since the US East Coast and Western Europe can be connected in 6 to 8 hours. This implies a full rotation of 2 legs per day, with European-bound flights leaving the US East Coast during the night, arriving in Europe in the morning, and heading back in the afternoon to arrive on the East Coast in the evening. There is a variety of aircraft combining high payloads and long-distance ranges. Early variants, such as the B707, have evolved into planes offering high capacity, such as the B747 series, which have evolved into extra long-range abilities. Today, the emphasis in this category is on twin-engine wide-body aircraft with high fuel efficiency and range. As of 2022, the longest-range aircraft were the Boeing B787 series (14,800 km range) and the Airbus A350 series (15,600 km range for the normal version, 18,000 kilometers for the ultra-long-range version). Aircraft such as these can link almost any pair of large cities worldwide if there is enough traffic to make the service profitable.

Across all these categories, a notable trend has been ever-longer ranges. One noticeable effect of improved aircraft technology is the bypassing effect, particularly over long hauls with the possibility of direct connections without intermediary stops . The first 737s in the 1960s had a range of just over 3,000 kilometers. Some of the most recent versions can fly more than 7,000 kilometers nonstop. Longer-range aircraft of all sizes facilitate the fragmentation of intercontinental and transcontinental markets and point-to-point services that depend less on hubs. For instance, in 2019, Norwegian Airlines operated a 737 on a 5,300-kilometer route between Hamilton, Ontario, and Dublin, Ireland. Otherwise, this city pair would have required a transfer to a hub such as Toronto.

d. Differences by traffic type and seasonality

An important aspect of airline networks is the emergence of separate air cargo services operating on separate networks. Most air cargo is carried in the bellyhold of passenger airplanes and provides supplementary income for airline companies. However, passenger aircraft are operated on routes that make sense for passengers but may not attract much cargo or may not operate at times that make sense for cargo shippers. In response to these factors, a growing number of freighter aircraft operations have spread across the world, using airplanes that carry cargo on the main decks and in their bellyholds and operate routes attuned to the needs of shippers. More than half of all air cargo is carried in freighters, including many operated by combination carriers (e.g., Qatar Airways) that carry passengers and cargo and operate mixed fleets of passenger and freighter aircraft.

More specifically, the air freight market is serviced by five types of operations:

- Passenger airlines (e.g., United Airlines) offer the freight capacity in the bellyhold of their all-passenger aircraft fleet. For these operators, freight services are rather secondary and represent a source of additional income, such as carrying mail . It remains an important market as about 50% of all the air cargo is carried in the bellyhold of regular passenger aircraft. However, low-cost airlines usually do not offer air cargo services since their priority is a fast rotation of their planes and servicing lower-cost airports that do not generate cargo volumes.

- Combination airlines (e.g., Korean Air) have fleets with freighters and passenger aircraft able to carry freight in their bellyhold. Most of the freighter operations involve long-haul services.

- Dedicated cargo operators (e.g., Cargolux) maintain a fleet of cargo-only aircraft and offer regularly scheduled services between the airports they service. They also offer charter operations to cater to specific needs.

- Air freight integrators (e.g., FedEx Express) operate air and ground freight services, providing nearly seamless (at least from the customer’s perspective) door-to-door deliveries.

- Specialized operators (e.g., Volga-Dnepr Airlines) fulfill niche services that cater to specific cargo requirements (e.g., heavy loads) that do not fit the capabilities of standard cargo aircraft.

Generally, the most important air cargo hubs, such as Memphis and Hong Kong, are also the hubs of key carriers. One important exception is Anchorage International Airport. Because freighters have shorter ranges than passenger aircraft and because freight is less sensitive to intermediate refueling stops than passengers, many freighters on transpacific routes refuel in Alaska to maximize their payload and clear US customs.

It is not uncommon for older aircraft, particularly wide-body aircraft, to be converted for cargo operations when they complete their commercial life on the passenger market. For instance, in mid-2022, the fleet of Amazon Air comprised converted Boeing 767 and Boeing 737 freighters. Former passenger jets like these have lower acquisition costs, a vast pool of experienced pilots, and the ready availability of parts for maintenance. On the other hand, new-build jets, such as the popular Boeing 777 freighter used by FedEx on many intercontinental routes, have greater reliability, fuel efficiency, and range.

A final feature of airline networks is their seasonality . Air cargo flows tend to peak near the Christmas season. However, some specific products (e.g., Valentine’s Day flowers in February or the shipment of thousands of tons of Beaujolais Nouveau wine from France to Asia each November) have different temporal patterns. For passenger air transport, July and August are the most traveled months overall, corresponding to the peak tourist season in Europe and North America. Elsewhere in the world, other seasonal patterns may be more important. For instance, in China, the busiest air travel days of the year tend to be close to the Spring Festival (or Lunar New Year) in January or February. The Muslim hajj generates millions of trips to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, over a five-day period each year, with the vast majority of pilgrims flying into either King Abdulaziz International Airport in Jeddah or Prince Mohammed bin Abdulaziz International Airport in Medina.

4. Airlines, Hubs, and Alliances

There are several thousand airlines in the world, most of them very small. Only about 1,400 are members of the International Air Transport Association (IATA), and even among IATA members, a relative handful of airlines account for most of the traffic. In 2018, the top 25 airlines accounted for just over 50 percent of available seat-kilometers (ASKs), a measure of capacity.

Most airlines have strongly centralized networks, and the hubs of the largest airlines are among the busiest airports in the world. Hub-and-spoke systems rely on the usage of an intermediate airport hub. They can either connect a domestic (or regional) air system if the market is large enough (e.g. United States, China, European Union) or international systems through longitudinal (e.g. Reykjavik) or latitudinal (Panama City) or both longitudinal and latitudinal (Dubai) intermediacy. An important aspect of an intermediate hub concerns maintaining schedule integrity. Airports that are prone to delays due to congestion are not effective hubs.

The traffic feed through hubs like Dubai enables the hubbing carrier (Emirates in this instance) to offer higher frequency service with larger aircraft at higher load factors , lowering the per passenger-kilometer cost. Traffic feed further permits a carrier to add services to more thinly traveled markets (e.g., in 2019, Emirates extended new nonstop services between Dubai and Porto, Portugal’s second-largest city).

Beginning in the 1970s, deregulation freed airlines to expand, consolidate, and reconfigure their hub-and-spoke systems to optimize their performance. Computer reservation systems and frequent flyer programs amplified the hubbing advantages of large carriers. These systems and programs leveraged the economies of scale provided by large hub-and-spoke carriers to draw still more traffic onto their networks.

The ability of airlines to spread their networks internationally has been limited both by the persistence of regulations and by the preferences that travelers have for their home country airlines. Carriers have overcome these limitations, at least partially, through the formation of alliances . Alliances are voluntary agreements that enhance the competitive positions of the partners. Members benefit from greater scale economies, lowering transaction costs, and sharing risks while remaining commercially independent. Today, the largest alliance is the Star Alliance, which was launched in 1997 by Air Canada, Lufthansa, SAS, Thai Airways International, and United Airlines. By 2022, 21 others had joined those five carriers, and the alliance’s combined network reached 193 countries with a combined fleet of more than 5,000 aircraft. The two other major alliances are SkyTeam (18 airlines led by Delta and Air France) and Oneworld (15 airlines led by British Airways and American Airlines).

Most large airlines belong to an alliance, a testament to the significant advantages of membership:

- Codesharing . Members of an alliance can sell seats on one another’s flights so that, from the passenger’s perspective, a single airline appears to offer a seamless service even though multiple members’ flights might be involved in getting from A to B. Codesharing effectively enlarges an airline’s network and increases the chance of capturing customers.

- Optimization of connections . Alliance members coordinate schedules at key hubs (e.g., Frankfurt for the Star Alliance) to facilitate connections from one member’s network to another. Adjacent gates in shared terminals accelerate connections. For example, all the Star Alliance airlines serving Beijing are co-located in Beijing Capital International Airport’s Terminal 3.

- Geographical specialization . An airline in an alliance can tap global markets while specializing in its home market. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, Star Alliance member Air Canada served only seven hubs in East and Southeast Asia. Still, via its alliance partners, it gained access to dozens of other cities in the region. In turn, Asian members of the Star Alliance, such as Singapore Airlines (SIA), accessed Air Canada’s vast network in its home country.

- Joint marketing . Alliance members reciprocate in frequent flyer programs and other marketing efforts. Travelers can earn and redeem miles across the members of an alliance.

The leading airlines in the alliances are full-service network carriers (FSNCs), also known as legacy airlines. FSNC refers to the fact that these airlines offer a wide array of services (especially for passengers in first or business class), and their key selling point is the reach of their networks (networks that have been stretched by the alliances). The phrase “legacy carrier” highlights the deep roots of these airlines, some of which, like KLM, Qantas, and Delta, rank among the oldest continuously operating carriers in the world.

Yet by the late 1990s, FSNCs as a group were losing the market share to LCCs. In 1998, there were approximately 60 budget airlines globally, and almost all of them were located in the US, Canada, and Western Europe. Together, they accounted for about 7 percent of all departure seat capacity per week worldwide. By 2018, there were approximately 140 LCCs; more than half were based in emerging markets, and accounting for about 31 percent of all seat capacity. Interestingly, budget airlines are most significant in middle-income emerging markets. In 2018, the countries where LCCs accounted for the largest share of capacity included Slovakia, Malaysia, Romania, India, and Mexico. In these countries (and their neighbors), the population that can afford air travel is growing, and competition from ground transport modes and from full-service network carriers (e.g., Air India) is weak. Conversely, budget carriers are weakest or altogether absent from poorer, authoritarian states with heavily protected state-owned flag carriers (e.g., Uzbekistan).

LCCs are distinguished by several common features :

- Fleet simplicity . Legacy carriers operate diverse fleets because they serve a diversity of routes, from long-hauls to feeders. LCCs emphasize short-haul routes. The minimal number of aircraft types (Southwest and Ryanair only fly B737s, though several different models) lowers operating costs.

- High seating density . Budget airlines pack more seats in a typically all-economy class configuration. For instance, the budget airline EasyJet fits 180 seats in its Airbus A320 aircraft versus 144 seats on the same plane used on intra-European routes for British Airways.

- Fast turnaround times . LCCs operate their networks in ways that keep their aircraft in the air, earning money for a higher number of hours. Minimal inflight service, for instance, reduces the time needed to clean and cater flights.

- Rapid growth . This is not just a product of the LCCs’ success but an element of it. Fast growth enables the LCCs to continue adding aircraft and staff at a steady pace, which keeps the average fleet age and average years of employee service low, both of which help keep operations costs low.

- Emphasis on secondary airports . Secondary airports, such as Houston-Hobby instead of George Bush Houston Intercontinental or Charleroi instead of Brussels National, typically have lower landing and parking fees for airlines as well as a more entrepreneurial approach to recruiting new airline services. However, LCCs have also directly challenged established carriers in major airports.

- Reduced importance of hubs . Most LCCs do have hubs, but for some carriers, hubs are substantially less important than they are for legacy carriers. Southwest Airlines, for instance, distributes air traffic more evenly among the top “focus cities” in its network than is true of any traditional hub-and-spoke airline. Whereas nearly half of all seat capacity on Delta Air Lines is on flights leaving just five hub cities, to reach the same share of capacity on Southwest Airlines requires combining eleven focus cities. Spreading traffic reduces vulnerability to congestion and frees aircraft to keep moving rather than waiting for arriving traffic at a hub.

- Aggressive digitalization . Internet booking has partially neutralized the one-time advantage that legacy carriers enjoyed through their proprietary computer reservation systems. LCCs have been industry leaders in using automated kiosks and smartphones to accelerate the check-in process. Digitalization has also facilitated segmented services and monetized once-included amenities such as seat selection, priority boarding, meals, and luggage allowance.

- Avoidance of global alliances . LCCs have stayed out of the big alliances discussed above because they come with obligations that can increase a member’s costs.

These and other advantages explain the gap between fares offered by LCCs and full-service network carriers. In advanced markets, decades of competition between these two types of airlines have whittled away the differences. In 2016, US network carriers had costs per available seat-mile about 40 percent higher than American LCCs. In developing countries, conversely, the budget airline phenomenon is newer, and the gap between LCCs and legacy carriers is generally wider. For instance, Singapore Airlines had unit costs twice as high as Malaysia-based LCC AirAsia in 2016. Still, the world’s largest airlines are almost all network carriers. Southwest Airlines, the pioneer LCC, is the only LCC to rank among the world’s 20 largest airlines .

LCCs are important in broadening the air transportation market beyond the relatively small affluent population in countries such as India and Brazil. Budget airlines’ slogans frequently highlight this democratizing effect, as in AirAsia’s motto “Now everyone can fly”, Wizz Air’s (Hungary) “Now we can all fly”, and Jambojet’s (Kenya) “Now you can fly”. These are exaggerations, but there is little doubt that LCCs have expanded the affordability of air travel.

Meanwhile, in advanced markets, the notion of a low-cost carrier is losing some of its meaning as budget airlines and full-service network carriers converge in some of their business practices and cost structures. The degree to which FSNCs have emulated low-cost carriers is a testament to the latter’s success, as is the fact that in numerous markets, the largest airline is now a budget carrier.

5. The Future of Flight

The COVID-19 pandemic has been the most severe crisis in civil aviation since World War II. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) has estimated worldwide airline industry losses at $84 billion for 2020. By April 2020, air traffic in most markets plummeted by more than 90% versus the same time in the previous year. By mid-2022, however, traffic levels were back to near pre-pandemic levels in North America and Western Europe. In fact, traffic recovered faster than expected in these markets, causing significant schedule problems. Airlines had sharply downsized their fleets and staff levels early in the pandemic, leaving them ill-prepared for the resumption of high traffic levels in 2022.

Longer-term challenges may emerge from the pandemic. The shift towards forms of teleworking, tele-education, and teleconferences may engender enduring changes in business travel behavior . Leisure travel behavior may also change. For instance, in 2021, tourists preferred shorter, domestic, or regional nonstop flights due to the increased exposure that comes with long-distance travel via hubs, including the burden of regulations, testing, and quarantine procedures associated with international travel. However, such preferences were less noticeable as testing and quarantine procedures were removed for most international travel in 2022.

The pandemic may also accelerate the shift away from full-service airlines toward LCCs. A large number of network carriers’ A380s and B747s parked in desert “boneyards” will never again carry passengers. For instance, Air France retired its A380 fleet in 2022. Between 2020 and 2022, the COVID-19 crisis shifted the balance of the industry toward cargo. Freight rates jumped during the pandemic, and cargo’s share of industry revenue soared from 12 percent in 2019 to 26 percent in 2020. Some airlines even converted a part of their passenger planes into cargo planes to take advantage of historically high freight rates that resulted.

Beyond the COVID-19 crisis, numerous clouds are on the horizon for civil aviation. First, the airline industry must be financially strong enough to continue to afford new generations of aircraft upon which further gains in efficiency and improved environmental performance depend. The development costs of new jetliners, even after adjusting for inflation, are unprecedented, partly because the latest generation of aircraft incorporates so many complex interfacing systems. The financial health of the industry’s largest airlines is particularly important because great carriers have previously provided the launch orders for new airliners. Pan Am, for instance, launched the B707 and B747; United launched the B767 and B777; Air France and Lufthansa provided the launch orders for most of Airbus’ early airliners; and Asian carriers such as Singapore Airlines and All Nippon Airways have been significant launch customers since 2000. By contrast, the LCCs’ focus on a handful of smaller, relatively short-haul aircraft limits their capacity to serve as catalysts for technological breakthroughs in aviation.

Still, both Boeing and Airbus promise that their newest jetliners will offer unparalleled fuel efficiency . That is important because a second fundamental threat to the future of the airline industry is the price and availability of fuel. In 2018, fuel accounted for about 24 percent of the operating costs of airlines globally. As noted above, aviation is less amenable to substituting conventional fossil fuels than ground transport modes, though numerous innovations show promise. The spike in fuel prices after the Russian invasion of Ukraine added impetus to decarbonizing the air transport sector.

A third threat is terrorism and security . The rise of the airline industry was partly facilitated by the steady advance in the safety and predictability of air travel from the early 20th century “Flying Coffins”. Terrorism directed against civil aviation threatens the confidence of ordinary travelers, and added security constraints sap some of the speed advantages of aviation. The September 11 attacks caused a two-year dip in traffic levels. The 2001 attacks were the most significant to affect the airline industry in the United States. Still, before and after those attacks, civil aviation was a frequent target of terrorist attacks in the Middle East, Europe, and other parts of the world.

With the growth of air traffic, airports were facing capacity pressures and congestion before the COVID-19 pandemic, which in some cases, resulted in changes in the scheduling of flights . In the United States, a flight that arrives more than 15 minutes past its scheduled time is considered late. Airlines are posting longer flight times to maintain the appearance of schedule integrity. For instance, a flight from New York to Los Angeles scheduled to take 5 hours in the 1960s is now scheduled to take more than 6 hours. A 45 minutes flight from New York to Washington saw its scheduled duration extended to one hour and 15 minutes.

Before the pandemic, emerging economies such as India, Indonesia, and Brazil saw a surge in air travel demand, both for domestic and international markets, a trend that strained their air transport systems. An essential means of dealing with this challenge has been the modernization of air traffic control systems , some of which remain highly fragmented. For instance, using satellite-based navigation, air travel can be improved with better flight paths and more direct descents. The outcomes include shorter flight times, improved safety, and lower fuel consumption and environmental emissions. Such innovations are likely to be very important again as traffic levels recover.

Environmental concerns are perhaps the darkest cloud on the horizon for civil aviation. Aviation has accounted for a growing share of environmental externalities , and strategies to curtail emissions and noise could mean higher aviation taxes, higher airfares, and restrictions on aircraft operations (e.g., nighttime curfews). Those most alarmed by aviation’s environmental impacts will likely resist the return to pre-pandemic practices, and governments may have the leverage to do so. The severe financial distress of the airline industry sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic has drawn governments back into the industry. In 2020, airlines received hundreds of billions of dollars in state aid, often with strings attached, giving governments new leverage over carriers. For instance, the French government has pressured Air France to become “greener”, including reducing competition with rail on short-haul sectors, as part of its bailout of the airline.

Ultimately, the speed with which air links have been reopened even during the pandemic speaks to the degree to which “aeromobility” is intertwined into the fabric of everyday life across much of the world. The COVID-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine war, and responses to longer-term concerns about air transportation’s role in climate change will change the trajectory and geography of aviation. Perhaps these crises will hasten the introduction of new, more environmentally friendly technologies such as electric aircraft. However, traffic volumes will almost certainly regain and surpass the heights attained before the pandemic. Air transportation will remain a vital force shaping the contours and tempo of society at scales ranging from the local to the global.

Related Topics

- 6.5 – Airport Terminals

- B.6 – Mega Airport Projects

- 5.1 – Transportation Modes: An Overview

- B.7 – International Tourism and Transport

- B.19 – Transportation and Pandemics

Bibliography

- Adey, P., L. Budd, and P. Hubbard (2007) “Flying Lessons: Exploring the Social and Cultural Geographies of Global Air Travel”, Progress in Human Geography, Vol. 31, No. 6, pp. 773-791.

- Agusdinata, B. and W. de Klein (2002) “The dynamics of airline alliances”, Journal of Air Transport Management, Vol. 8, pp. 201-211.

- Air Transport Association (2010) The Airline Handbook.

- Air Transport Action Group (2008) The Economic Benefits of Air Transport.

- Allaz, C. (2005) History of Air Cargo and Airmail from the 18th Century, London: Christopher Foyle Publishing.

- Bilstein, R.E. (1983) Flight Patterns: Trends of Aeronautical Development in the United States, 1918-1929. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- Bowen, J. (2010) The Economic Geography of Air Transportation: Space, Time, and the Freedom of the Sky. London: Routledge .

- Bowen, J. (2019) Low-Cost Carriers in Emerging Countries. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Brueckner, K. (2003) “Airline traffic and urban economic development”, Urban Studies, Vol. 40, No. 8, pp. 1455-1469.

- Davies, R.E.G. (1964) A History of the World’s Airlines. London: Oxford University Press.

- Dick, R. and D. Patterson (2003) Aviation Century: The Early Years. Erin, Ontario: Boston Mills Press.

- Fuellhart, K. and K. O’Connor (2019) “A supply-side categorization of airports across global multiple-airport cities and regions”, GeoJournal,Vol. 84, No. 1, pp 15-30.

- Goetz, A.R. and L. Budd (eds) (2014) The Geographies of Air Transport, Transport and Mobility Series, Farnham, Surrey, England: Ashgate.

- Graham B. (1995) Geography and Air Transport, Chichester: Wiley.

- Lin, W. (2020) “Aeromobilities in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic”, Transfers, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 102–110.

- O’Connell, J.F. and G. Williams (2013) Air Transport in the 21st Century: Key Strategic Development, Farnham, Surrey, England: Ashgate.

- Prentice, B. (2016) “The Role of the Airship in the New Low-Carbon Era”, The Shipper Advocate, Fall, pp. 16-19.

- Solberg, C. (1979) Conquest of the Skies: A History of Commercial Aviation in America. Boston: Little, Brown & Company.

- Yergin, D. R.H.K. Vietor and P.C. Evans (2000) Fettered Flight: Globalization and the Airline Industry, Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Energy Research Associates.

Share this:

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

History of Flight: Breakthroughs, Disasters and More

By: Aaron Randle

Updated: February 6, 2024 | Original: July 9, 2021

For thousands of years, humans have dreamed of taking to the skies. The quest has led from kite flying in ancient China to hydrogen-powered hot-air balloons in 18th-century France to contemporary aircraft so sophisticated they can’t be detected by radar or the human eye.

Below is a timeline of humans’ obsession with flight, from da Vinci to drones. Fasten your seatbelt and prepare for liftoff.

1505-06: Da Vinci dreams of flight, publishes his findings

Few figures in history had more detailed ideas, theories and imaginings on aviation as the Italian artist and inventor Leonardo da Vinci . His book Codex on the Flight of Birds contained thousands of notes and hundreds of sketches on the nature of flight and aerodynamic principles that would lay much of the early groundwork for—and greatly influence—the development of aviation and manmade aircraft.

November 21, 1783: First manned hot-air balloon flight

Two months after French brothers Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier engineered a successful test flight with a duck, a sheep and a rooster as passengers, two humans ascended in a Montgolfier-designed balloon over Paris. Powered by a hand-fed fire, the paper-and-silk aircraft rose 500 vertical feet and traveled some 5.5 miles over about half an hour. But in an 18th-century version of the space race, rival balloon engineers Jacques Alexander Charles and Nicholas Louis Robert upped the ante just 10 days later. Their balloon, powered by hydrogen gas, traveled 25 miles and stayed aloft more than two hours.

6 Little‑Known Pioneers of Aviation

From an early glider experimenter to the first man to fly solo around the world, here are six lesser‑known pilots and inventors who made their mark on aviation.

10 Things You May Not Know About the Wright Brothers

Check out 10 things you may not know about the aviation pioneers.

How America’s Aviation Industry Got Its Start Transporting Mail

Before carrying passengers, America’s most iconic airlines hauled the mail. It was one of the riskiest jobs around.

1809-1810: Sir George Cayley introduces aerodynamics

At the dawn of the 19th century, English philosopher George Cayley published “ On Aerial Navigation ,” a radical series of papers credited with introducing the world to the study of aerodynamics. By that time, the man who came to be known as “the father of aviation” had already been the first to identify the four forces of flight (weight, lift, drag, thrust), developed the first concept of a fixed-wing flying machine and designed the first glider reported to have carried a human aloft.

September 24, 1852: Giffard's dirigible proves powered air travel is possible

Half a century before the Wright brothers took to the skies, French engineer Henri Giffard manned the first-ever powered and controllable airborne flight. Giffard, who invented the steam injector, traveled almost 17 miles from Paris to Élancourt in his “Giffard Dirigible,” a 143-foot-long, cigar-shaped airship loosely steered by a three-bladed propeller that was powered by a 250-pound, 3-horsepower engine, itself lit by a 100-pound boiler. The flight proved that a steam-powered airship could be steered and controlled.

1876: The internal combustion engine changes everything

Building on advances by French engineers, German engineer Nikolaus Otto devised a lighter, more efficient, gas-powered combustion engine, providing an alternative to the previously universal steam-powered engine. In addition to revolutionizing automobile travel, the innovation ushered in a new era of longer, more controlled aviation.

December 17, 1903: The Wright brothers become airborne—briefly

Flying from Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright made the first controlled, sustained flight of a heavier-than-air aircraft. Each brother flew their wooden, gasoline-powered propeller biplane, the “Wright Flyer,” twice (four flights total), with the shortest lasting 12 seconds and the longest sustaining flight for about 59 seconds. Considered a historic event today, the feat was largely ignored by newspapers of the time, who believed the flights were too short to be important.

1907: The first helicopter lifts off

French engineer and bicycle maker Paul Cornu became the first man to ride a rotary-wing, vertical-lift aircraft, a precursor to today’s helicopter, when he was lifted about 1.5 meters off the ground for 20 seconds near Lisieux, France. Versions of the helicopter had been toyed with in the past—Italian engineer Enrico Forlanini debuted the first rotorcraft three decades prior in 1877. And it would be improved upon in the future, with American designer Igor Sikorsky introducing a more standardized version in Stratford, Connecticut in 1939. But it was Cornu’s short flight that would land him in the history books as the definitive first.

1911-12: Harriet Quimby achieves two firsts for women pilots

Journalist Harriet Quimby became the first American woman ever awarded a pilot’s license in 1911, after just four months of flight lessons. Capitalizing on her charisma and showmanship (she became as famous for her violet satin flying suit as for her attention to safety checks), Quimby achieved another first the following year when she became the first woman to fly solo across the English channel. The feat was overshadowed, however, by the sinking of the Titanic two days earlier.

October 1911: The aircraft becomes militarized

Italy became the first country to significantly incorporate aircraft into military operations when, during the Turkish-Italian war, it employed both monoplanes and airships for bombing, reconnaissance and transportation. Within a few years, aircraft would play a decisive role in the World War I.

January 1, 1914: First commercial passenger flight

On New Year’s Day, pilot Tony Jannus transported a single passenger, Mayor Abe Pheil of St. Petersburg, Florida across Tampa Bay via his flying airboat, the “St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line.” The 23-mile flight (mostly along the Tampa Bay shore) cost $5.00 and would lay the foundation for the commercial airline industry.

1914-1918: World war accelerates the militarization of aircraft

World War I became the first major conflict to use aircraft on a large-scale, expanding their use in active combat. Nations appointed high-ranking generals to oversee air strategy, and a new breed of war hero emerged: the fighter pilot or “flying ace.”

According to The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Military Aircraft , France was the war’s leading aircraft manufacturer, producing nearly 68,000 planes between 1914 and 1918. Of those, nearly 53,000 were shot down, crashed or damaged.

June 1919: First nonstop transatlantic flight

Flying a modified ‘Vickers Vimy’ bomber from the Great War, British aviators and war veterans John Alcock and Arthur Brown made the first-ever nonstop transatlantic flight. Their perilous 16-hour journey , undertaken eight years before Charles Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic alone, started in St. John's, Newfoundland, where they barely cleared the trees at the end of the runway. After a calamity-filled flight, they crash-landed in a peat bog in County Galway, Ireland; remarkably, neither man was injured.

1921: Bessie Coleman becomes the first Black woman to earn a pilot’s license

The fact that Jim Crow-era U.S. flight schools wouldn’t accept a Black woman didn’t stop Bessie Coleman. Instead, the Texas-born sharecropper’s daughter, one of 13 siblings, learned French so she could apply to the Caudron Brothers’ School of Aviation in Le Crotoy, France. There, in 1921, she became the first African American woman to earn a pilot's license. After performing the first public flight by a Black woman in 1922—including her soon-to-be trademark loop-the-loop and figure-8 aerial maneuvers—she became renowned for her thrilling daredevil air shows and for using her growing fame to encourage Black Americans to pursue flying. Coleman died tragically in 1926, as a passenger in a routine test flight. Thousands reportedly attended her funeral in Chicago.

1927: Lucky Lindy makes first solo transatlantic flight

Nearly a decade after Alcock and Brown made their transatlantic flight together, 25-year-old Charles Lindbergh of Detroit was thrust into worldwide fame when he completed the first solo crossing , just a few days after a pair of celebrated French aviators perished in their own attempt. Flying the “Spirit of St. Louis” aircraft from New York to Paris, “Lucky Lindy” made the first transatlantic voyage between two major hubs—and the longest transatlantic flight by more than 2,000 miles. The feat instantly made Lindbergh one of the great folk heroes of his time, earned him the Medal of Honor and helped usher in a new era of interest in the possibilities of aviation.

1932: Amelia Earhart repeats Lindbergh’s feat

Five years after Lindbergh completed his flight, “Lady Lindy” Amelia Earhart became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean , setting off from Harbour Grace, Newfoundland on May 20, 1932 and landing some 14 hours later in Culmore, Northern Ireland. In her career as an aviator, Earhart would become a worldwide celebrity, setting several women’s speed, domestic distance and transcontinental aviation records. Her most memorable feat, however, would prove to be her last. In 1937, while attempting to circumnavigate the globe, Earhart disappeared over the central Pacific ocean and was never seen or heard from again.

1937: The Hindenburg crashes…along with the ‘Age of Airships’

Between WWI and WWII, aviation pioneers and major aircraft companies like Germany’s Luftshiffbau Zeppelin tried hard to popularize bulbous, lighter-than-air airships—essentially giant flying gas bags—as a mode of commercial transportation. The promise of the steam-powered, hydrogen-filled airships quickly evaporated, however, after the infamous 1937 Hindenburg disaster . That’s when the gas inside the Zeppelin company’s flagship Hindenburg vessel exploded during a landing attempt, killing 35 passengers and crew members and badly burning the majority of the 62 remaining survivors.

October 14, 1947: Chuck Yeager breaks the sound barrier

An ace combat fighter during WWII, Chuck Yeager earned the title “Fastest Man Alive” when he hit 700 m.p.h. while testing the experimental X-1 supersonic rocket jet for the military over the Mojave Desert in 1947. Being the first person to travel faster than the speed of sound has been hailed as one of the most epic feats in the history of aviation—not bad for someone who got sick to his stomach after his first-ever flight.

1949: The world’s first commercial jetliner takes off

Early passenger air travel was noisy, cold, uncomfortable and bumpy, as planes flew at low altitudes that brought them through, not above, the weather. But when the British-manufactured de Havilland Comet took its first flight in 1949—boasting four turbine engines, a pressurized cabin, large windows and a relatively comfortable seating area—it marked a pivotal step in modern commercial air travel. An early, flawed design however, caused the de Havilland to be grounded after a series of mid-flight disasters—but not before giving the world a glimpse of what was possible.

1954-1957: Boeing glamorizes flying

With the debut of the sleek 707 aircraft, touted for its comfort, speed and safety, Seattle-based Boeing ushered in the age of modern American jet travel. Pan American Airways became the first commercial carrier to take delivery of the elongated, swept-wing planes, launching daily flights from New York to Paris. The 707 quickly became a symbol of postwar modernity—a time when air travel would become commonplace, people dressed up to fly and flight attendants reflected the epitome of chic. The plane even inspired Frank Sinatra’s hit song “Come Fly With Me.”

March 27, 1977: Disaster at Tenerife

In the greatest aviation disaster in history, 583 people were killed and dozens more injured when two Boeing 747 jets—Pan Am 1736 and KLM 4805— collided on the Los Rodeos Airport runway in Spain’s Canary Islands. The collision occurred when the KLM jet, trying to navigate a runway shrouded in fog, initiated its takeoff run while the Pan Am jetliner was still on the runway. All aboard the KLM flight and most on the Pan Am flight were killed. Tragically, neither plane was scheduled to fly from that airport on that day, but a small bomb set off at a nearby airport caused them both to be diverted to Los Rodeos.

1978: Flight goes electronic

The U.S. Air Force developed and debuted the first fly-by-wire operating system for its F-16 Fighting Falcon fighter plane. The system, which replaced the aircraft’s manual flight control system with an electronic one, ushered in aviation’s “Information Age,” one in which navigation, communications and hundreds of other operating systems are automated with computers. This advance has led to developments like unmanned aerial vehicles and drones, more nimble missiles and the proliferation of stealth aircraft.

1986: Around the world, without landing

American pilots Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager (no relation to Chuck) completed the first around-the-world flight without refueling or landing . Their “Rutan Model 76 Voyager,” a single-wing, twin-engine craft designed by Rutan’s brother, was built with 17 fuel tanks to accommodate long-distance flight.

HISTORY Vault: 101 Inventions That Changed the World

Take a closer look at the inventions that have transformed our lives far beyond our homes (the steam engine), our planet (the telescope), and our wildest dreams (the Internet).

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

AIR & SPACE MAGAZINE

The airplane changed our idea of the world.

The invention of the airplane shook the globe, and it never looked the same again.

Paul Glenshaw

:focal(696x208:697x209)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1e/f0/1ef02cd2-b4e9-42b0-be77-d73e125ba96a/12h_am2021_nicefrance_si-2001-11633_live.jpg)

The advent of human flight not only boosted our power of movement, but also enhanced our vision: We gained the ability to see the Earth from above. Before the Wrights’ epochal breakthrough, there had been perhaps thousands of human flights, mostly in balloons. But it was the advent of the airplane—a whole new way of seeing and experiencing our planet with speed and control—that led to euphoric reactions across the world. Wilbur and Orville caused the eruption with their first public flights in the summer and early fall of 1908.

In order to appreciate just how big the news was, it’s important to remember the widespread skepticism of the Wrights’ claims to have perfected a fully practical flying machine. They did not hide their machine during its development through 1905, but didn’t exactly invite crowds either. On February 10, 1906, the New York Herald put it bluntly: “The Wrights have flown or they have not flown. They possess a machine or they do not possess one. They are in fact either fliers or liars.”

But when they flew for the public—Wilbur first, on August 8, 1908, in Le Mans, France—the press reports were breathless: “I’ve seen him! I’ve seen them!” a reporter for Le Figaro cried. “There is no doubt! Wilbur and Orville Wright have well and truly flown!” Wilbur’s flights came on the heels of earlier French and American successes by other competitors: Henry Farman winning the Deutsch-Archdeacon prize for a one-kilometer circular flight; Glenn Curtiss winning the Scientific American Cup for a one-kilometer straight-line flight in his June Bug. But Wilbur’s flights in France, and then Orville’s at Fort Myer, Virginia, were longer and in greater control by far than anything that had come before. “WORLD’S AIR SHIP RECORD SMASHED BY ORVILLE WRIGHT AT FT. MYER, VA.,” blared the Washington Times on September 13 after he flew for more than an hour. An eyewitness was quoted as saying, “I would rather be Orville Wright right now than the President of the United States!”

When airplanes first flew, they brought two new astonishing experiences to the human race. One was simply the sight of a fellow human being traveling through the sky at speed and in control. Grand contests were held for the public to witness the miracle. The first such competition in the United States was at Dominguez Field in Los Angeles in January, 1910. “In Trial Flight [Glenn] Curtiss Soars Like Huge Bird. Thousands Cheer as New and Untried Biplane Leaps into the Sky,” announced the Los Angeles Herald . The meet ran for 10 days, and more than 250,000 people attended.

The second novel aspect of airplane flight was what the aviators and their passengers saw from the sky—experiencing our enhanced vision for the first time. Famed reporter Richard Harding Davis best describes the transformation. He went to Aiken, South Carolina to fly with Wright exhibition pilot and instructor Frank Coffyn in 1911. Although he’d covered the Johnstown Flood and the Spanish-American War, he approached Coffyn’s Wright Model B with terror. “I began to hate Coffyn and the Wright brothers,” he wrote. “I began to regret that I had not been brought up a family man so… I could explain that I could not go aloft because I had children to support. I was willing to support any number of children. Anybody’s children.”

But once they were in the air, “a wonderful thing happened,” he wrote. “The polo field and then the high board fence around it, and a tangle of telegraph wires, and the tops of the highest pine trees suddenly sank beneath us.... They fell so swiftly that in a moment the Whisky Road became a yellow ribbon, and the Iselin house and gardens a white ball on a green billiard cloth. We wheeled evenly in a sharp curve, and beyond us for miles saw cotton fields like a great chess board.”

He underwent an epiphany. “I began to understand why young men with apparently everything to make them happy on earth persist in leaving it by means of aeroplanes.... What lures them is the call of a new world waiting to be conquered, the sense of power, of detachment from everything humdrum, or even human, the thrill that makes all the other sensations stale and vapid, the exhilaration that for the moment makes each one of them a king.”