Doing a Meta-Analysis: A Practical, Step-by-Step Guide

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

What is a Meta-Analysis?

Meta-analysis is a statistical procedure used to combine and synthesize findings from multiple independent studies to estimate the average effect size for a particular research question.

Meta-analysis goes beyond traditional narrative reviews by using statistical methods to integrate the results of several studies, leading to a more objective appraisal of the evidence.

This method addresses limitations like small sample sizes in individual studies, providing a more precise estimate of a treatment effect or relationship strength.

Meta-analyses are particularly valuable when individual study results are inconclusive or contradictory, as seen in the example of vitamin D supplementation and the prevention of fractures.

For instance, a meta-analysis published in JAMA in 2017 by Zhao et al. examined 81 randomized controlled trials involving 53,537 participants.

The results of this meta-analysis suggested that vitamin D supplementation was not associated with a lower risk of fractures among community-dwelling adults. This finding contradicted some earlier beliefs and individual study results that had suggested a protective effect.

What’s the difference between a meta-analysis, systematic review, and literature review?

Literature reviews can be conducted without defined procedures for gathering information. Systematic reviews use strict protocols to minimize bias when gathering and evaluating studies, making them more transparent and reproducible.

While a systematic review thoroughly maps out a field of research, it cannot provide unbiased information on the magnitude of an effect. Meta-analysis statistically combines effect sizes of similar studies, going a step further than a systematic review by weighting each study by its precision.

What is Effect Size?

Statistical significance is a poor metric in meta-analysis because it only indicates whether an effect is likely to have occurred by chance. It does not provide information about the magnitude or practical importance of the effect.

While a statistically significant result may indicate an effect different from zero, this effect might be too small to hold practical value. Effect size, on the other hand, offers a standardized measure of the magnitude of the effect, allowing for a more meaningful interpretation of the findings

Meta-analysis goes beyond simply synthesizing effect sizes; it uses these statistics to provide a weighted average effect size from studies addressing similar research questions. The larger the effect size the stronger the relationship between two variables.

If effect sizes are consistent, the analysis demonstrates that the findings are robust across the included studies. When there is variation in effect sizes, researchers should focus on understanding the reasons for this dispersion rather than just reporting a summary effect.

Meta-regression is one method for exploring this variation by examining the relationship between effect sizes and study characteristics.

T here are three primary families of effect sizes used in most meta-analyses:

- Mean difference effect sizes : Used to show the magnitude of the difference between means of groups or conditions, commonly used when comparing a treatment and control group.

- Correlation effect sizes : Represent the degree of association between two continuous measures, indicating the strength and direction of their relationship.

- Odds ratio effect sizes : Used with binary outcomes to compare the odds of an event occurring between two groups, like whether a patient recovers from an illness or not.

The most appropriate effect size family is determined by the nature of the research question and dependent variable. All common effect sizes are able to be transformed from one version to another.

Real-Life Example

Brewin, C. R., Andrews, B., & Valentine, J. D. (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 68 (5), 748.

This meta-analysis of 77 articles examined risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in trauma-exposed adults, with sample sizes ranging from 1,149 to over 11,000. Several factors consistently predicted PTSD with small effect sizes (r = 0.10 to 0.19), including female gender, lower education, lower intelligence, previous trauma, childhood adversity, and psychiatric history. Factors occurring during or after trauma showed somewhat stronger effects (r = 0.23 to 0.40), including trauma severity, lack of social support, and additional life stress. Most risk factors did not predict PTSD uniformly across populations and study types, with only psychiatric history, childhood abuse, and family psychiatric history showing homogeneous effects. Notable differences emerged between military and civilian samples, and methodological factors influenced some risk factor effects. The authors concluded that identifying a universal set of pretrauma predictors is premature and called for more research to understand how vulnerability to PTSD varies across populations and contexts.

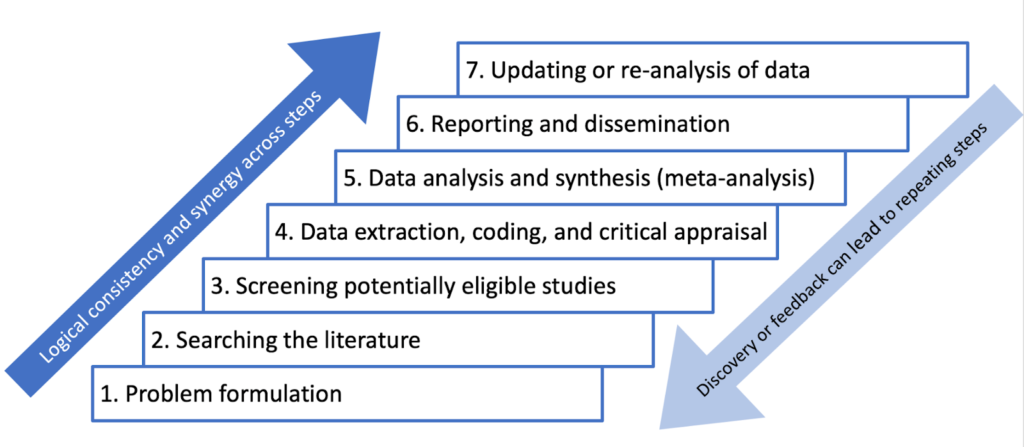

How to Conduct a Meta-Analysis

Researchers should develop a comprehensive research protocol that outlines the objectives and hypotheses of their meta-analysis.

This document should provide specific details about every stage of the research process, including the methodology for identifying, selecting, and analyzing relevant studies.

For example, the protocol should specify search strategies for relevant studies, including whether the search will encompass unpublished works.

The protocol should be created before beginning the research process to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

Research Protocol

- To estimate the overall effect of growth mindset interventions on the academic achievement of students in primary and secondary school.

- To investigate if the effect of growth mindset interventions on academic achievement differs for students of different ages (e.g., elementary school students vs. high school students).

- To examine if the duration of the growth mindset intervention impacts its effectiveness.

- Growth mindset interventions will have a small, but statistically significant, positive effect on student academic achievement.

- Growth mindset interventions will be more effective for younger students than for older students.

- Longer growth mindset interventions will be more effective than shorter interventions.

Eligibility Criteria

- Published studies in English-language journals.

- Studies must include a quantitative measure of academic achievement (e.g., GPA, course grades, exam scores, or standardized test scores).

- Studies must involve a growth mindset intervention as the primary focus (including control vs treatment group comparison).

- Studies that combine growth mindset training with other interventions (e.g., study skills training, other types of psychological interventions) should be excluded.

Search Strategy

The researchers will search the following databases:

Keywords Combined with Boolean Operators:

- (“growth mindset” OR “implicit theories of intelligence” OR “mindset theory”) AND (“intervention” OR “training” OR “program”) ” OR “educational outcomes”) * OR “pupil ” OR “learner*”)**

Additional Search Strategies:

- Citation Chaining: Examining the reference lists of included studies can uncover additional relevant articles.

- Contacting Experts: Reaching out to researchers in the field of growth mindset can reveal unpublished studies or ongoing research.

Coding of Studies

The researchers will code each study for the following information:

- Sample size

- Age of participants

- Duration of intervention

- Type of academic outcome measured

- Study design (e.g., randomized controlled trial, quasi-experiment)

Statistical Analysis

- The researchers will calculate an effect size (e.g., standardized mean difference) for each study.

- The researchers will use a random-effects model to account for variation in effect sizes across studies.

- The researchers will use meta-regression to test the hypotheses about moderators of the effect of growth mindset interventions.

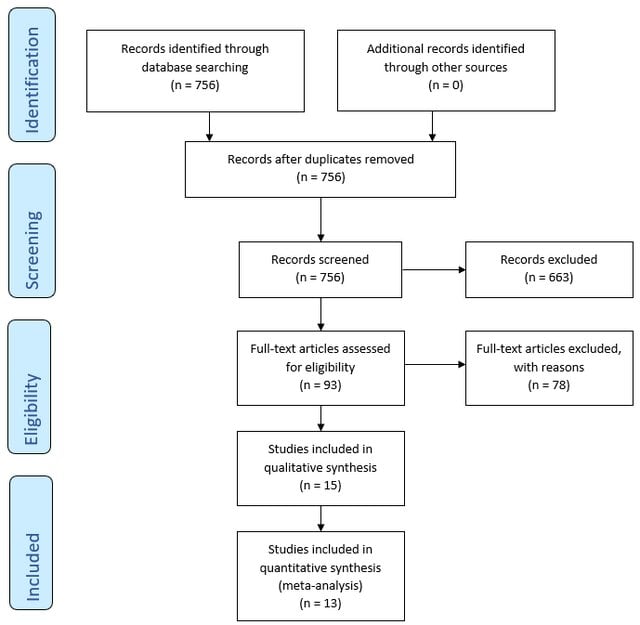

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) is a reporting guideline designed to improve the transparency and completeness of systematic review reporting.

PRISMA was created to tackle the issue of inadequate reporting often found in systematic reviews

- Checklist : PRISMA features a 27-item checklist covering all aspects of a meta-analysis, from the rationale and objectives to the synthesis of findings and discussion of limitations. Each checklist item is accompanied by detailed reporting recommendations in an Explanation and Elaboration document .

- Flow Diagram : PRISMA also includes a flow diagram to visually represent the study selection process, offering a clear, standardized way to illustrate how researchers arrived at the final set of included studies

Step 1: Defining a Research Question

A well-defined research question is a fundamental starting point for any research synthesis. The research question should guide decisions about which studies to include in the meta-analysis, and which statistical model is most appropriate.

For example:

- How do dysfunctional attitudes and negative automatic thinking directly and indirectly impact depression?

- Do growth mindset interventions generally improve students’ academic achievement?

- What is the association between child-parent attachment and prosociality in children?

- What is the relation of various risk factors to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)?

Step 2: Search Strategy

Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. PRISMA 2020 Checklist

A search strategy is a comprehensive and reproducible plan for identifying all relevant research studies that address a specific research question.

This systematic approach to searching helps minimize bias.

It’s important to be transparent about the search strategy and document all decisions for auditability. The goal is to identify all potentially relevant studies for consideration.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) provide appropriate guidance for reporting quantitative literature searches.

Information Sources

The primary goal is to find all published and unpublished studies that meet the predefined criteria of the research question. This includes considering various sources beyond typical databases

Information sources for a meta-analysis can include a wide range of resources like scholarly databases, unpublished literature, conference papers, books, and even expert consultations.

Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. PRISMA 2020 Checklist

An exhaustive, systematic search strategy is developed with the assistance of an expert librarian.

- Databases: Searches should include seven key databases: CINAHL, Medline, APA PsycArticles, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, APA PsycInfo, SocINDEX with Full Text, and Web of Science: Core Collections.

- Grey Literature : In addition to databases, forensic or ‘expansive’ searches can be conducted. This includes: grey literature database searches (e.g. OpenGrey , WorldCat , Ethos ), conference proceedings, unpublished reports, theses , clinical trial databases , searches by names of authors of relevant publications. Independent research bodies may also be good sources of material, e.g. Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations , Joseph Rowntree Foundation , Carers UK .

- Citation Searching : Reference lists often lead to highly cited and influential papers in the field, providing valuable context and background information for the review.

- Contacting Experts: Reaching out to researchers or experts in the field can provide access to unpublished data or ongoing research not yet publicly available.

It is important to note that this may not be an exhaustive list of all potential databases.

Search String Construction

It is recommended to consult topic experts on the review team and advisory board in order to create as complete a list of search terms as possible for each concept.

To retrieve the most relevant results, a search string is used. This string is made up of:

- Keywords: Search terms should be relevant to the research questions, key variables, participants, and research design. Searches should include indexed terms, titles, and abstracts. Additionally, each database has specific indexed terms, so a targeted search strategy must be created for each database.

- Synonyms: These are words or phrases with similar meanings to the keywords, as authors may use different terms to describe the same concepts. Including synonyms helps cover variations in terminology and increases the chances of finding all relevant studies. For example, a drug intervention may be referred to by its generic name or by one of its several proprietary names.

- Truncation symbols : These broaden the search by capturing variations of a keyword. They function by locating every word that begins with a specific root. For example, if a user was researching interventions for smoking, they might use a truncation symbol to search for “smok*” to retrieve records with the words “smoke,” “smoker,” “smoking,” or “smokes.” This can save time and effort by eliminating the need to input every variation of a word into a database.

- Boolean operators: The use of Boolean operators (AND/OR/NEAR/NOT) helps to combine these terms effectively, ensuring that the search strategy is both sensitive and specific. For instance, using “AND” narrows the search to include only results containing both terms, while “OR” expands it to include results containing either term.

When conducting these searches, it is important to combine browsing of texts (publications) with periods of more focused systematic searching. This iterative process allows the search to evolve as the review progresses.

It is important to note that this information may not be entirely comprehensive and up-to-date.

Studies were identified by searching PubMed, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Library. We conducted searches for studies published between the first available year and April 1, 2009, using the search term mindfulness combined with the terms meditation, program, therapy, or intervention and anxi , depress , mood, or stress. Additionally, an extensive manual review was conducted of reference lists of relevant studies and review articles extracted from the database searches. Articles determined to be related to the topic of mindfulness were selected for further examination.

Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review. PRISMA 2020 Checklist

Before beginning the literature search, researchers should establish clear eligibility criteria for study inclusion

To maintain transparency and minimize bias, eligibility criteria for study inclusion should be established a priori. Ideally, researchers should aim to include only high-quality randomized controlled trials that adhere to the intention-to-treat principle.

The selection of studies should not be arbitrary, and the rationale behind inclusion and exclusion criteria should be clearly articulated in the research protocol.

When specifying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, consider the following aspects:

- Intervention Characteristics: Researchers might decide that, in order to be included in the review, an intervention must have specific characteristics. They might require the intervention to last for a certain length of time, or they might determine that only interventions with a specific theoretical basis are appropriate for their review.

- Population Characteristics: A meta-analysis might focus on the effects of an intervention for a specific population. For instance, researchers might choose to focus on studies that included only nurses or physicians.

- Outcome Measures: Researchers might choose to include only studies that used outcome measures that met a specific standard.

- Age of Participants: If a meta-analysis is examining the effects of a treatment or intervention for children, the authors of the review will likely choose to exclude any studies that did not include children in the target age range.

- Diagnostic Status of Participants: Researchers conducting a meta-analysis of treatments for anxiety will likely exclude any studies where the participants were not diagnosed with an anxiety disorder.

- Study Design: Researchers might determine that only studies that used a particular research design, such as a randomized controlled trial, will be included in the review.

- Control Group: In a meta-analysis of an intervention, researchers might choose to include only studies that included certain types of control groups, such as a waiting list control or another type of intervention.

- Publication status : Decide whether only published studies will be included or if unpublished works, such as dissertations or conference proceedings, will also be considered.

Studies were selected if (a) they included a mindfulness-based intervention, (b) they included a clinical sample (i.e., participants had a diagnosable psychological or physical/medical disorder), (c) they included adult samples (18 – 65 years of age), (d) the mindfulness program was not coupled with treatment using acceptance and commitment therapy or dialectical behavior therapy, (e) they included a measure of anxiety and/or mood symptoms at both pre and postintervention, and (f) they provided sufficient data to perform effect size analyses (i.e., means and standard deviations, t or F values, change scores, frequencies, or probability levels). Studies were excluded if the sample overlapped either partially or completely with the sample of another study meeting inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis. In these cases, we selected for inclusion the study with the larger sample size or more complete data for measures of anxiety and depression symptoms. For studies that provided insufficient data but were otherwise appropriate for the analyses, authors were contacted for supplementary data.

Iterative Process

The iterative nature of developing a search strategy stems from the need to refine and adapt the search process based on the information encountered at each stage.

A single attempt rarely yields the perfect final strategy. Instead, it is an evolving process involving a series of test searches, analysis of results, and discussions among the review team.

Here’s how the iterative process unfolds:

- Initial Strategy Formulation: Based on the research question, the team develops a preliminary search strategy, including identifying relevant keywords, synonyms, databases, and search limits.

- Test Searches and Refinement: The initial search strategy is then tested on chosen databases. The results are reviewed for relevance, and the search strategy is refined accordingly. This might involve adding or modifying keywords, adjusting Boolean operators, or reconsidering the databases used.

- Discussions and Iteration: The search results and proposed refinements are discussed within the review team. The team collaboratively decides on the best modifications to improve the search’s comprehensiveness and relevance.

- Repeating the Cycle: This cycle of test searches, analysis, discussions, and refinements is repeated until the team is satisfied with the strategy’s ability to capture all relevant studies while minimizing irrelevant results.

By constantly refining the search strategy based on the results and feedback, researchers can be more confident that they have identified all relevant studies.

This iterative process ensures that the applied search strategy is sensitive enough to capture all relevant studies while maintaining a manageable scope.

Throughout this process, meticulous documentation of the search strategy, including any modifications, is crucial for transparency and future replication of the meta-analysis.

Step 3: Search the Literature

Conduct a systematic search of the literature using clearly defined search terms and databases.

Applying the search strategy involves entering the constructed search strings into the respective databases’ search interfaces. These search strings, crafted using Boolean operators, truncation symbols, wildcards, and database-specific syntax, aim to retrieve all potentially relevant studies addressing the research question.

The researcher, during this stage, interacts with the database’s features to refine the search and manage the retrieved results.

This might involve employing search filters provided by the database to focus on specific study designs, publication types, or other relevant parameters.

Applying the search strategy is not merely a mechanical process of inputting terms; it demands a thorough understanding of database functionalities and a discerning eye to adjust the search based on the nature of retrieved results.

Step 4: Screening & Selecting Research Articles

Once the literature search is complete, the next step is to screen and select the studies that will be included in the meta-analysis.

This involves carefully reviewing each study to determine its relevance to the research question and its methodological quality.

The goal is to identify studies that are both relevant to the research question and of sufficient quality to contribute to a meaningful synthesis.

Studies meeting the eligibility criteria are usually saved into electronic databases, such as Endnote or Mendeley , and include title, authors, date and publication journal along with an abstract (if available).

Selection Process

Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. PRISMA 2020 Checklist

The selection process in a meta-analysis involves multiple reviewers to ensure rigor and reliability.

Two reviewers should independently screen titles and abstracts, removing duplicates and irrelevant studies based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Initial screening of titles and abstracts: After applying a strategy to search the literature,, the next step involves screening the titles and abstracts of the identified articles against the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. During this initial screening, reviewers aim to identify potentially relevant studies while excluding those clearly outside the scope of the review. It is crucial to prioritize over-inclusion at this stage, meaning that reviewers should err on the side of keeping studies even if there is uncertainty about their relevance. This cautious approach helps minimize the risk of inadvertently excluding potentially valuable studies.

- Retrieving and assessing full texts: For studies which a definitive decision cannot be made based on the title and abstract alone, reviewers need to obtain the full text of the articles for a comprehensive assessment against the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. This stage involves meticulously reviewing the full text of each potentially relevant study to determine its eligibility definitively.

- Resolution of Disagreements : In cases of disagreement between reviewers regarding a study’s eligibility, a predefined strategy involving consensus-building discussions or arbitration by a third reviewer should be in place to reach a final decision. This collaborative approach ensures a fair and impartial selection process, further strengthening the review’s reliability.

PRISMA Flowchart

The PRISMA flowchart is a visual representation of the study selection process within a systematic review.

The flowchart illustrates the step-by-step process of screening, filtering, and selecting studies based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The flowchart visually depicts the following stages:

- Identification: The initial number of titles and abstracts identified through database searches.

- Screening: The screening process, based on titles and abstracts.

- Eligibility: Full-text copies of the remaining records are retrieved and assessed for eligibility.

- Inclusion: Applying the predefined inclusion criteria resulted in the inclusion of publications that met all the criteria for the review.

- Exclusion: The flowchart details the reasons for excluding the remaining records.

This systematic and transparent approach, as visualized in the PRISMA flowchart, ensures a robust and unbiased selection process, enhancing the reliability of the systematic review’s findings.

The flowchart serves as a visual record of the decisions made during the study selection process, allowing readers to assess the rigor and comprehensiveness of the review.

- How to fill a PRISMA flow diagram

Step 5: Evaluating the Quality of Studies

Data collection process.

Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. PRISMA 2020 Checklist

Data extraction focuses on information relevant to the research question, such as risk or recovery factors related to a particular phenomenon.

Extract data relevant to the research question, such as effect sizes, sample sizes, means, standard deviations, and other statistical measures.

It can be useful to focus on the authors’ interpretations of findings rather than individual participant quotes, as the latter lacks the full context of the original data.

The coding of studies in a meta-analysis involves carefully and systematically extracting data from each included study in a standardized and reliable manner. This step is essential for ensuring the accuracy and validity of the meta-analysis’s findings.

This information is then used to calculate effect sizes, examine potential moderators, and draw overall conclusions.

Coding procedures typically involve creating a standardized record form or coding protocol. This form guides the extraction of data from each study in a consistent and organized manner. Two independent observers can help to ensure accuracy and minimize errors during data extraction.

Beyond basic information like authors and publication year, code crucial study characteristics relevant to the research question.

For example, if the meta-analysis focuses on the effects of a specific therapy, relevant characteristics to code might include:

- Study characteristics : Publicatrion year, authors, country of origin, publication status ( Published : Peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters Unpublished : Government reports, websites, theses/dissertations, conference presentations, unpublished manuscripts).

- Intervention : Type (e.g., CBT), duration of treatment, frequency (e.g., weekly sessions), delivery method (e.g., individual, group, online), intention-to-treat analysis (Yes/No)

- Outcome measures : Primary vs. secondary outcomes, time points of measurement (e.g., post-treatment, follow-up).

- Moderators : Participant characteristics that might moderate the effect size. (e.g., age, gender, diagnosis, socioeconomic status, education level, comorbidities).

- Study design : Design (RCT quasi-experiment, etc.), blinding, control group used (e.g., waitlist control, treatment as usual), study setting (clinical, community, online/remote, inpatient vs. outpatient), pre-registration (yes/no), allocation method (simple randomization, block randomization, etc.).

- Sample : Recruitment method (snowball, random, etc.), sample size (total and groups), sample location (treatment & control group), attrition rate, overlap with sample(s) from another study?

- Adherence to reporting guidelines : e.g., CONSORT, STROBE, PRISMA

- Funding source : Government, industry, non-profit, etc.

- Effect Size : Comprehensive meta-analysis program is used to compute d and/or r. Include up to 3 digits after the decimal point for effect size information and internal consistency information. Also record the page number and table number from which the information is coded. This information helps when checking reliability and accuracy to ensure we are coding from the same information.

Before applying the coding protocol to all studies, it’s crucial to pilot test it on a small subset of studies. This helps identify any ambiguities, inconsistencies, or areas for improvement in the coding protocol before full-scale coding begins.

It’s common to encounter missing data in primary research articles. Develop a clear strategy for handling missing data, which might involve contacting study authors, using imputation methods, or performing sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of missing data on the overall results.

Quality Appraisal Tools

Researchers use standardized tools to assess the quality and risk of bias in the quantitative studies included in the meta-analysis. Some commonly used tools include:

- Recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration for assessing randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

- Evaluates potential biases in selection, performance, detection, attrition, and reporting.

- Used for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies, including case-control and cohort studies.

- Evaluates selection, comparability, and outcome assessment.

- Assesses risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions.

- Evaluates confounding, selection bias, classification of interventions, deviations from intended interventions, missing data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of reported results.

- Specifically designed for diagnostic accuracy studies.

- Assesses risk of bias and applicability concerns in patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing.

By using these tools, researchers can ensure that the studies included in their meta-analysis are of high methodological quality and contribute reliable quantitative data to the overall analysis.

Step 6: Choice of Effect Size

The choice of effect size metric is typically determined by the research question and the nature of the dependent variable.

- Odds Ratio (OR) : For instance, if researchers are working in medical and health sciences where binary outcomes are common (e.g., yes/no, failed/success), effect sizes like relative risk and odds ratio are often used.

- Mean Difference : Studies focusing on experimental or between-group comparisons often employ mean differences. The raw mean difference, or unstandardized mean difference, is suitable when the scale of measurement is inherently meaningful and comparable across studies.

- Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) : If studies use different scales or measures, the standardized mean difference (e.g., Cohen’s d) is more appropriate. When analyzing observational studies, the correlation coefficient is commonly chosen as the effect size.

- Pearson correlation coefficient (r) : A statistical measure frequently employed in meta-analysis to examine the strength of the relationship between two continuous variables.

Conversion of efect sizes to a common measure

May be necessary to convert reported findings to the chosen primary effect size. The goal is to harmonize different effect size measures to a common metric for meaningful comparison and analysis.

This conversion allows researchers to include studies that report findings using various effect size metrics. For instance, r can be approximately converted to d, and vice versa, using specific equations. Similarly, r can be derived from an odds ratio using another formula.

Many equations relevant to converting effect sizes can be found in Rosenthal (1991).

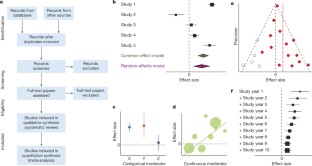

Step 7: Assessing Heterogeneity

Heterogeneity refers to the variation in effect sizes across studies after accounting for within-study sampling errors.

Heterogeneity refers to how much the results (effect sizes) vary between different studies, where no variation would mean all studies showed the same improvement (no heterogeneity), while greater variation indicates more heterogeneity.

Assessing heterogeneity matters because it helps us understand if the study intervention works consistently across different contexts and guides how we combine and interpret the results of multiple studies.

While little heterogeneity allows us to be more confident in our overall conclusion, significant heterogeneity necessitates further investigation into its underlying causes.

How to assess heterogeneity

- Homogeneity Test : Meta-analyses typically include a homogeneity test to determine if the effect sizes are estimating the same population parameter. The test statistic, denoted as Q, is a weighted sum of squares that follows a chi-square distribution. A significant Q statistic suggests that the effect sizes are heterogeneous.

- I2 Statistic : The I2 statistic is a relative measure of heterogeneity that represents the ratio of between-study variance (τ2) to the total variance (between-study variance plus within-study variance). Higher I2 values indicate greater heterogeneity.

- Prediction Interval : Examining the width of a prediction interval can provide insights into the degree of heterogeneity. A wide prediction interval suggests substantial heterogeneity in the population effect size.

Step 8: Choosing the Meta-Analytic Model

Meta-analysts address heterogeneity by choosing between fixed-effects and random-effects analytical models.

Use a random-effects model if heterogeneity is high. Use a fixed-effect model if heterogeneity is low, or if all studies are functionally identical and you are not seeking to generalize to a range of scenarios.

Although a statistical test for homogeneity can help assess the variability in effect sizes across studies, it shouldn’t dictate the choice between fixed and random effects models.

The decision of which model to use is ultimately a conceptual one, driven by the researcher’s understanding of the research field and the goals of the meta-analysis.

If the number of studies is limited, a fixed-effects analysis is more appropriate, while more studies are required for a stable estimate of the between-study variance in a random-effects model.

It is important to note that using a random-effects model is generally a more conservative approach.

Fixed-effects models

- Assumes all studies are measuring the exact same thing

- Gives much more weight to larger studies

- Use when studies are very similar

Fixed-effects models assume that there is one true effect size underlying all studies. The goal is to estimate this common effect size with the greatest precision, which is achieved by minimizing the within-study (sampling).

Consequently, studies are weighted by the inverse of their variance.

This means that larger studies, which generally have smaller variances, are assigned greater weight in the analysis because they provide more precise estimates of the common effect size

- Simplicity: The fixed-effect model is straightforward to implement and interpret, making it computationally simpler.

- Precision: When the assumption of a common effect size is met, fixed-effect models provide more precise estimates with narrower confidence intervals compared to random-effects models.

- Suitable for Conditional Inferences: Fixed-effect models are appropriate when the goal is to make inferences specifically about the studies included in the meta-analysis, without generalizing to a broader population.

- Restrictive Assumptions: The fixed-effect model assumes all studies estimate the same population parameter, which is often unrealistic, particularly with studies drawn from diverse methodologies or populations.

- Limited Generalizability: Findings from fixed-effect models are conditional on the included studies, limiting their generalizability to other contexts or populations.

- Sensitivity to Heterogeneity: Fixed-effect models are sensitive to the presence of heterogeneity among studies, and may produce misleading results if substantial heterogeneity exists.

Random-effects models

- Assumes studies might be measuring slightly different things

- Gives more balanced weight to both large and small studies

- Use when studies might vary in methods or populations

Random-effects models assume that the true effect size can vary across studies. The goal here is to estimate the mean of these varying effect sizes, considering both within-study variance and between-study variance (heterogeneity).

This approach acknowledges that each study might estimate a slightly different effect size due to factors beyond sampling error, such as variations in study populations, interventions, or designs.

This balanced weighting prevents large studies from disproportionately influencing the overall effect size estimate, leading to a more representative average effect size that reflects the distribution of effects across a range of studies.

- Realistic Assumptions: Random-effects models acknowledge the presence of between-study variability by assuming true effects are randomly distributed, making it more suitable for real-world research scenarios.

- Generalizability: Random-effects models allow for broader inferences to be made about a population of studies, enhancing the generalizability of findings.

- Accommodation of Heterogeneity: Random-effects models explicitly model heterogeneity, providing a more accurate representation of the overall effect when studies have varying effect sizes.

- Complexity: Random-effects models are computationally more complex, requiring the estimation of additional parameters, such as between-study variance.

- Reduced Precision: Confidence intervals tend to be wider compared to fixed-effect models, particularly when between-study heterogeneity is substantial.

- Requirement for Sufficient Studies: Accurate estimation of between-study variance necessitates a sufficient number of studies, making random-effects models less reliable with smaller meta-analyses.

Step 9: Perform the Meta-Analysis

This step involves statistically combining effect sizes from chosen studies. Meta-analysis uses the weighted mean of effect sizes, typically giving larger weights to more precise studies (often those with larger sample sizes).

The main function of meta-analysis is to estimate effects in a population by combining the effect sizes from multiple articles.

It uses a weighted mean of the effect sizes, typically giving larger weights to more precise studies, often those with larger sample sizes.

This weighting scheme makes statistical sense because an effect size with good sampling accuracy (i.e., likely to be an accurate reflection of reality) is weighted highly.

On the other hand, effect sizes from studies with lower sampling accuracy are given less weight in the calculations.

the process:

- Calculate weights for each study

- Multiply each study’s effect by its weight

- Add up all these weighted effects

- Divide by the sum of all weights

Estimating effect size using fixed effects

The fixed-effects model in meta-analysis operates under the assumption that all included studies are estimating the same true effect size.

This model focuses solely on within-study variance when determining the weight of each study.

The weight is calculated as the inverse of the within-study variance, which typically results in larger studies receiving substantially more weight in the analysis.

This approach is based on the idea that larger studies provide more precise estimates of the true effect.

The weighted mean effect size (M) is calculated by summing the products of each study’s effect size (ESi) and its corresponding weight (wi) and dividing that sum by the total sum of the weights:

1. Calculate weights (wi) for each study:

The weight is often the inverse of the variance of the effect size. This means studies with larger sample sizes and less variability will have greater weight, as they provide more precise estimates of the effect size

This weighting scheme reflects the assumption in a fixed-effect model that all studies are estimating the same true effect size, and any observed differences in effect sizes are solely due to sampling error. Therefore, studies with less sampling error (i.e., smaller variances) are considered more reliable and are given more weight in the analysis.

Here’s the formula for calculating the weight in a fixed-effect meta-analysis:

Wi = 1 / VYi 1

- Wi represents the weight assigned to study i.

- VYi is the within-study variance for study i.

Practical steps:

- The weight for each study is calculated as: Weight = 1 / (within-study variance)

- For example: Let’s say a study reports a within-study variance of 0.04. The weight for this study would be: 1 / 0.04 = 25

- Calculate the weight for every study included in your meta-analysis using this method.

- These weights will be used in subsequent calculations, such as computing the weighted mean effect size.

- Note : In a fixed-effects model, we do not calculate or use τ² (tau squared), which represents between-study variance. This is only used in random-effects models.

2. Multiply each study’s effect by its weight:

After calculating the weight for each study, multiply the effect size by its corresponding weight. This step is crucial because it ensures that studies with more precise effect size estimates contribute proportionally more to the overall weighted mean effect size

- For each study, multiply its effect size by the weight we just calculated.

3. Add up all these weighted effects:

Sum up all the products from step 2.

4. Divide by the sum of all weights:

- Add up all the weights we calculated in step 1.

- Divide the sum from step 3 by this total weight.

Implications of the fixed-effects model

- Larger studies (with smaller within-study variance) receive substantially more weight.

- This model assumes that differences between study results are due only to sampling error.

- It’s most appropriate when studies are very similar in methods and sample characteristics.

Estimating effect size using random effects

Random effects meta-analysis is slightly more complicated because multiple sources of differences potentially affecting effect sizes must be accounted for.

The main difference in the random effects model is the inclusion of τ² (tau squared) in the weight calculation. This accounts for between-study heterogeneity, recognizing that studies might be measuring slightly different effects.

This process results in an overall effect size that takes into account both within-study and between-study variability, making it more appropriate when studies differ in methods or populations.

The model estimates the variance of the true effect sizes (τ²). This requires a reasonable number of studies, so random effects estimation might not be feasible with very few studies.

Estimation is typically done using statistical software, with restricted maximum likelihood (REML) being a common method.

1. Calculate weights for each study:

In a random-effects meta-analysis, the weight assigned to each study (W*i) is calculated as the inverse of that study’s variance, similar to a fixed-effect model. However, the variance in a random-effects model considers both the within-study variance (VYi) and the between-studies variance (T^2).

The inclusion of T^2 in the denominator of the weight formula reflects the random-effects model’s assumption that the true effect size can vary across studies.

This means that in addition to sampling error, there is another source of variability that needs to be accounted for when weighting the studies. The between-studies variance, T^2, represents this additional source of variability.

Here’s the formula for calculating the weight in a random-effects meta-analysis:

W*i = 1 / (VYi + T^2)

- W*i represents the weight assigned to study i.

- T^2 is the estimated between-studies variance.

First, we need to calculate something called τ² (tau squared). This represents the between-study variance.

The estimation of T^2 can be done using different methods, one common approach being the method of moments (DerSimonian and Laird method).

The formula for T^2 using the method of moments is: T^2 = (Q – df) / C

- Q is the homogeneity statistic.

- df is the degrees of freedom (number of studies -1).

- C is a constant calculated based on the study weights

- The weight for each study is then calculated as: Weight = 1 / (within-study variance + τ²). This is different from the fixed effects model because we’re adding τ² to account for between-study variability.

Add up all the weights we calculated in step 1. Divide the sum from step 3 by this total weight

Implications of the random-effects model

- Weights are more balanced between large and small studies compared to the fixed-effects model.

- It’s most appropriate when studies vary in methods, sample characteristics, or other factors that might influence the true effect size.

- The random-effects model typically produces wider confidence intervals, reflecting the additional uncertainty from between-study variability.

- Results are more generalizable to a broader population of studies beyond those included in the meta-analysis.

- This model is often more realistic for social and behavioral sciences, where true effects may vary across different contexts or populations.

Step 10: Sensitivity Analysis

Assess the robustness of your findings by repeating the analysis using different statistical methods, models (fixed-effects and random-effects), or inclusion criteria. This helps determine how sensitive your results are to the choices made during the process.

Sensitivity analysis strengthens a meta-analysis by revealing how robust the findings are to the various decisions and assumptions made during the process. It helps to determine if the conclusions drawn from the meta-analysis hold up when different methods, criteria, or data subsets are used.

This is especially important since opinions may differ on the best approach to conducting a meta-analysis, making the exploration of these variations crucial.

Here are some key ways sensitivity analysis contributes to a more robust meta-analysis:

- Assessing Impact of Different Statistical Methods : A sensitivity analysis can involve calculating the overall effect using different statistical methods, such as fixed and random effects models. This comparison helps determine if the chosen statistical model significantly influences the overall results. For instance, in the meta-analysis of β-blockers after myocardial infarction, both fixed and random effects models yielded almost identical overall estimates. This suggests that the meta-analysis findings are resilient to the statistical method employed.

- Evaluating the Influence of Trial Quality and Size : By analyzing the data with and without trials of questionable quality or varying sizes, researchers can assess the impact of these factors on the overall findings.

- Examining the Effect of Trials Stopped Early : Including trials that were stopped early due to interim analysis results can introduce bias. Sensitivity analysis helps determine if the inclusion or exclusion of such trials noticeably changes the overall effect. In the example of the β-blocker meta-analysis, excluding trials stopped early had a negligible impact on the overall estimate.

- Addressing Publication Bias : It’s essential to assess and account for publication bias, which occurs when studies with statistically significant results are more likely to be published than those with null or nonsignificant findings. This can be accomplished by employing techniques like funnel plots, statistical tests (e.g., Begg and Mazumdar’s rank correlation test, Egger’s test), and sensitivity analyses.

By systematically varying different aspects of the meta-analysis, researchers can assess the robustness of their findings and address potential concerns about the validity of their conclusions.

This process ensures a more reliable and trustworthy synthesis of the research evidence.

Common Mistakes

When conducting a meta-analysis, several common pitfalls can arise, potentially undermining the validity and reliability of the findings. Sources caution against these mistakes and offer guidance on conducting methodologically sound meta-analyses.

- Insufficient Number of Studies: If there are too few primary studies available, a meta-analysis might not be appropriate. While a meta-analysis can technically be conducted with only two studies, the research community might not view findings based on a limited number of studies as reliable evidence. A small number of studies could suggest that the research field is not mature enough for meaningful synthesis.

- Inappropriate Combination of Studies : Meta-analyses should not simply combine studies indiscriminately. Avoid the “apples and oranges” problem, where studies with different research objectives, designs, measures, or samples are inappropriately combined. Such practices can obscure important differences between studies and lead to misleading conclusions.

- Misinterpreting Heterogeneity : One common mistake is using the Q statistic or p-value from a test of heterogeneity as the sole indicator of heterogeneity. While these statistics can signal heterogeneity, they do not quantify the extent of variation in effect sizes.

- Over-Reliance on Published Studies : This dependence on published literature introduces the risk of publication bias, where studies with statistically significant or favorable results are more likely to be published. Failure to acknowledge and address publication bias can lead to overestimating the true effect size.

- Neglecting Study Quality : Including studies with poor methodological quality can bias the results of a meta-analysis leading to unreliable and inaccurate effect size estimates. The decision of which studies to include should be based on predefined eligibility criteria to ensure the quality and relevance of the synthesis.

- Fixation on Statistical Significance : Placing excessive emphasis on the statistical significance of an overall effect while neglecting its practical significance is a critical mistake in meta-analysis, as is the case in primary studies. Considers both statistical and clinical or substantive significance.

- Misinterpreting Significance Testing in Subgroup Analyses : When comparing effect sizes across subgroups, merely observing that an effect is statistically significant in one subgroup but not another is insufficient. Conduct formal tests of statistical significance for the difference in effects between subgroups or to calculate the difference in effects with confidence intervals.

- Ignoring Dependence : Neglecting dependence among effect sizes, particularly when multiple effect sizes are extracted from the same study, is a mistake. This oversight can inflate Type I error rates and lead to inaccurate estimations of average effect sizes and standard errors.

- Inadequate Reporting : Failing to transparently and comprehensively report the meta-analysis process is a crucial mistake. A meta-analysis should include a detailed written protocol outlining the research question, search strategy, inclusion criteria, and analytical methods.

Reading List

- Bar-Haim, Y., Lamy, D., Pergamin, L., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2007). Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study . Psychological bulletin , 133 (1), 1.

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2021). Introduction to meta-analysis . John Wiley & Sons.

- Crits-Christoph, P. (1992). A Meta-analysis . American Journal of Psychiatry , 149 , 151-158.

- Duval, S. J., & Tweedie, R. L. (2000). A nonparametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 95 (449), 89–98.

- Egger, M., Davey Smith, G., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test . BMJ, 315 (7109), 629–634.

- Egger, M., Smith, G. D., & Phillips, A. N. (1997). Meta-analysis: principles and procedures . Bmj , 315 (7121), 1533-1537.

- Field, A. P., & Gillett, R. (2010). How to do a meta‐analysis . British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology , 63 (3), 665-694.

- Hedges, L. V., & Pigott, T. D. (2004). The power of statistical tests for moderators in meta-analysis . Psychological methods , 9 (4), 426.

- Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (2014). Statistical methods for meta-analysis . Academic press.

- Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review . Journal of consulting and clinical psychology , 78 (2), 169.

- Littell, J. H., Corcoran, J., & Pillai, V. (2008). Systematic reviews and meta-analysis . Oxford University Press.

- Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? . Psychological bulletin , 131 (6), 803.

- Macnamara, B. N., & Burgoyne, A. P. (2022). Do growth mindset interventions impact students’ academic achievement? A systematic review and meta-analysis with recommendations for best practices. Psychological Bulletin .

- Polanin, J. R., & Pigott, T. D. (2015). The use of meta‐analytic statistical significance testing . Research Synthesis Methods , 6 (1), 63-73.

- Rodgers, M. A., & Pustejovsky, J. E. (2021). Evaluating meta-analytic methods to detect selective reporting in the presence of dependent effect sizes . Psychological methods , 26 (2), 141.

- Rosenthal, R. (1991). Meta-analysis: a review. Psychosomatic medicine , 53 (3), 247-271.

- Tipton, E., Pustejovsky, J. E., & Ahmadi, H. (2019). A history of meta‐regression: Technical, conceptual, and practical developments between 1974 and 2018 . Research synthesis methods , 10 (2), 161-179.

- Zhao, J. G., Zeng, X. T., Wang, J., & Liu, L. (2017). Association between calcium or vitamin D supplementation and fracture incidence in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama , 318 (24), 2466-2482.

- How it works

"Christmas Offer"

Terms & conditions.

As the Christmas season is upon us, we find ourselves reflecting on the past year and those who we have helped to shape their future. It’s been quite a year for us all! The end of the year brings no greater joy than the opportunity to express to you Christmas greetings and good wishes.

At this special time of year, Research Prospect brings joyful discount of 10% on all its services. May your Christmas and New Year be filled with joy.

We are looking back with appreciation for your loyalty and looking forward to moving into the New Year together.

"Claim this offer"

In unfamiliar and hard times, we have stuck by you. This Christmas, Research Prospect brings you all the joy with exciting discount of 10% on all its services.

Offer valid till 5-1-2024

We love being your partner in success. We know you have been working hard lately, take a break this holiday season to spend time with your loved ones while we make sure you succeed in your academics

Discount code: RP0996Y

Meta-Analysis – Definition, Purpose And How To Conduct It

Published by Owen Ingram at April 26th, 2023 , Revised On September 23, 2024

The number of studies being published in biomedical and clinical literature is increasing day by day. The massive abundance of research studies in these areas makes it rather difficult to synthesise all data and accumulate knowledge from various studies. All of this delays certain clinical decisions and conclusions to be made.

To determine the validity of a hypothesis , it is necessary to look into multiple studies rather than just one. For this purpose, systematic reviews or narrative reviews have been used to synthesise data from multiple studies, which often leads to an objective approach as different people can have different opinions. Meta-analysis, on the other hand, provides an objective and quantitative approach to combining evidence from various studies.

What Is Meta-Analysis?

The meaning of meta-analysis is a statistical method of combining results from numerous studies on a certain research question. The term was first used in 1976 and can be used to determine if the effect reported in the literature is real or not.

To conduct a quality meta-analysis, you need to identify an area in which the effect of treatment is uncertain. It is also recommended that you collect as many studies similar to the effect as possible so that you can compare them and get a better picture of it. This assists the researcher in understanding how big or small the effect is, and how different the results are from other studies.

Purpose Of Meta-Analysis In Research

The purpose of meta-analysis is more than just combining results from studies to give a statistical assessment. It also helps to point out:

- Any potential reasons for variations and differences in results, also known as heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Some popular reasons for this might be differences in sample size, or differences in analysis methods in research.

- The real estimate of the effect size that is reported in literature than any individual study. Combining multiple studies reduces research bias and the chances of random errors.

Meta-Analysis In Applied And Basic Research

Basic research involves seeking knowledge and gathering data on any subject, whereas applied research is more experimental and uses methods to solve real-life problems. Meta-analyses are used in both types of research that is applied and basic research.

- Pharmaceutical companies use meta-analyses to gain approval for new drugs, such as antibiotics for bacterial infections. Even regulatory authorities use this research method to gain approval for different processes. Hence, meta-analysis is used in medicine, crime, education and psychology for applied research.

- In terms of basic research, it is used in various fields such as sociology, finance, economics, marketing and social psychology. An example of meta-analysis in basic research is studying the effect of caffeine on cognitive performance.

Strengths and Limitations Of Meta-Analysis

There are many key benefits of meta-analysis in research studies, as it is a powerful tool. Here are some strengths of it:

- A meta-analysis takes place after a systematic review, which means the end product will be reliable and accurate.

- It has great statistical power, as it combines multiple studies rather than one individual study, which might suffer from a lack of sufficient data.

- This analysis can confirm existing research or refute it. Either way, it gives a confirmatory data analysis.

- It is regarded highly in the scientific community, as it provides an objective and solid analysis of evidence.

Challenges Associated With Meta-Analysis

Meta-analysis also has certain challenges that result in limitations while carrying out this statistical quantitative approach. Some challenges faced by meta-analyses are:

- It is not always possible to predict the outcome of a large-scale study. This is because meta-analysis mostly rely on small-scale studies which do not represent the broad population.

- A decent meta-analysis can not make up for flawed or bad research designs. Thus, it can not control the potential for bias to arise in studies. Therefore, it is urged to only include research with sound methodologies known as “best evidence synthesis”.

Hire an Expert Writer

Orders completed by our expert writers are

- Formally drafted in an academic style

- Free Amendments and 100% Plagiarism Free – or your money back!

- 100% Confidential and Timely Delivery!

- Free anti-plagiarism report

- Appreciated by thousands of clients. Check client reviews

How To Conduct A Meta-Analysis

Before conducting a meta-analysis and defining the research scope, it is necessary to evaluate the number of publications that have grown over the years. It can be quite hard to scan and skim through a large number of studies and literature reviews, which is why it is necessary to define the research question with care, including only relevant aspects. Here are steps on how to perform a meta-analysis:

- Formulate a research question that showcases the effects or interventions to be studied. This is mostly a binary question, such as “Does drug X improve outcome Y” in clinical studies.

- Conduct a systematic review that analyses and synthesises all data related to the one research question.

- Gather all data such as sample sizes and research methods used to indicate data variability. All decide which dependent variables are allowed.

- The selection of criteria is also a crucial step as it is necessary to understand whether published or unpublished studies are to be included or not. Based on the research question, it is important to choose studies that are quality-based and relevant.

- Choosing the right meta-analytic methods and meta-analysis software to be used in meta-analysis is another significant step. Some methods used are traditional univariate meta-analysis, meta-regression and meta-analytic structural equation modelling methods.

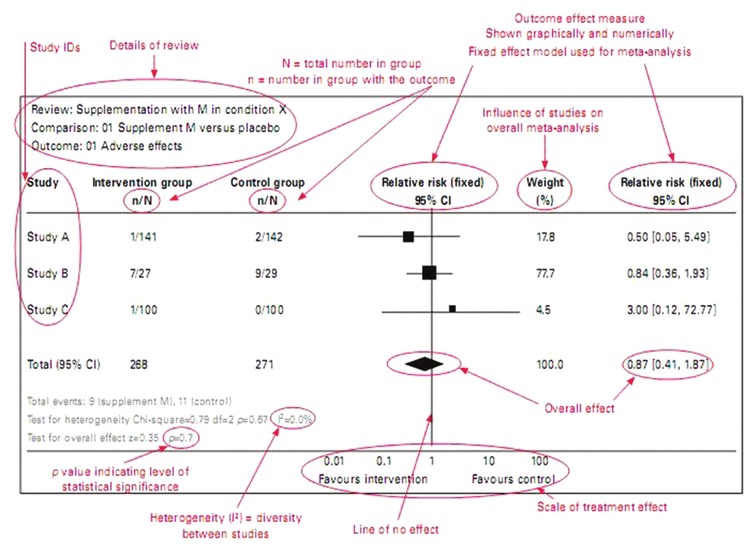

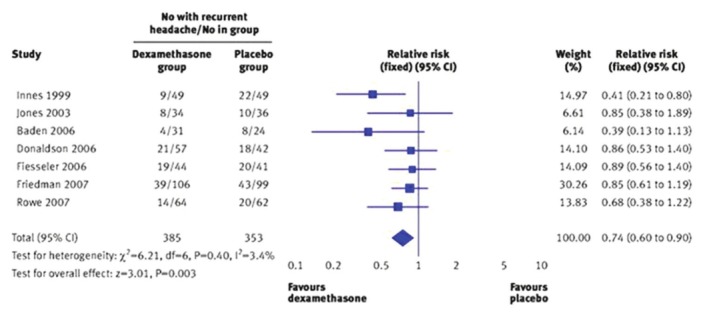

- While evaluating the data, it is necessary to use a meta-analysis forest plot, which is the graphical representation of the results of a meta-analysis studies. Its visual representation helps understand the heterogeneity among studies and helps compare the overall effect sizes of an intervention.

- The final step of literature meta-analysis is to report the results. They should be comprehensive and precise for the reader’s understanding.

Meta-Analysis Vs Systematic Review

A systematic review is a comprehensive analysis of existing research, whereas a meta-analysis is a statistical analysis or combination of results from two separate studies. Here’s how the two differ from each other:

Frequently Asked Questions

Where does meta-analysis fit in the research process.

It plays a key role in planning new studies and identifying answers to research questions. It is also widely sought for publications. Lastly, it is also used for grant applications that are used to justify the need for a new study.

Which fields use meta-analysis?

Common fields where meta-analyses are used are medicine, psychology, sociology, education, and health. It may also be used in finance, marketing and economics.

Is meta-analysis qualitative or quantitative?

Meta-analysis is a quantitative method that uses statistical methods to synthesise and collect data from various studies to estimate the size of the effect of a particular intervention or treatment.

You May Also Like

Quantitative research is associated with measurable numerical data. Qualitative research is where a researcher collects evidence to seek answers to a question.

In correlational research, a researcher measures the relationship between two or more variables or sets of scores without having control over the variables.

A case study is a detailed analysis of a situation concerning organizations, industries, and markets. The case study generally aims at identifying the weak areas.

As Featured On

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

Splash Sol LLC

- How It Works

Meta-analysis

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

Meta-analysis is an objective examination of published data from many studies of the same research topic identified through a literature search. Through the use of rigorous statistical methods, it can reveal patterns hidden in individual studies and can yield conclusions that have a high degree of reliability. It is a method of analysis that is especially useful for gaining an understanding of complex phenomena when independent studies have produced conflicting findings.

Meta-analysis provides much of the underpinning for evidence-based medicine. It is particularly helpful in identifying risk factors for a disorder, diagnostic criteria, and the effects of treatments on specific populations of people, as well as quantifying the size of the effects. Meta-analysis is well-suited to understanding the complexities of human behavior.

- How Does It Differ From Other Studies?

- When Is It Used?

- What Are Some Important Things Revealed by Meta-analysis?

There are well-established scientific criteria for selecting studies for meta-analysis. Usually, meta-analysis is conducted on the gold standard of scientific research—randomized, controlled, double-blind trials. In addition, published guidelines not only describe standards for the inclusion of studies to be analyzed but also rank the quality of different types of studies. For example, cohort studies are likely to provide more reliable information than case reports.

Through statistical methods applied to the original data collected in the included studies, meta-analysis can account for and overcome many differences in the way the studies were conducted, such as the populations studied, how interventions were administered, and what outcomes were assessed and how. Meta-analyses, and the questions they are attempting to answer, are typically specified and registered with a scientific organization, and, with the protocols and methods openly described and reviewed independently by outside investigators, the research process is highly transparent.

Meta-analysis is often used to validate observed phenomena, determine the conditions under which effects occur, and get enough clarity in clinical decision-making to indicate a course of therapeutic action when individual studies have produced disparate findings. In reviewing the aggregate results of well-controlled studies meeting criteria for inclusion, meta-analysis can also reveal which research questions, test conditions, and research methods yield the most reliable results, not only providing findings of immediate clinical utility but furthering science.

The technique can be used to answer social and behavioral questions large and small. For example, to clarify whether or not having more options makes it harder for people to settle on any one item, a meta-analysis of over 53 conflicting studies on the phenomenon was conducted. The meta-analysis revealed that choice overload exists—but only under certain conditions. You will have difficulty selecting a TV show to watch from the massive array of possibilities, for example, if the shows differ from each other in multiple ways or if you don’t have any strong preferences when you finally get to sit down in front of the TV.

A meta-analysis conducted in 2000, for example, answered the question of whether physically attractive people have “better” personalities . Among other traits, they prove to be more extroverted and have more social skills than others. Another meta-analysis, in 2014, showed strong ties between physical attractiveness as rated by others and having good mental and physical health. The effects on such personality factors as extraversion are too small to reliably show up in individual studies but real enough to be detected in the aggregate number of study participants. Together, the studies validate hypotheses put forth by evolutionary psychologists that physical attractiveness is important in mate selection because it is a reliable cue of health and, likely, fertility.

The stress generation hypothesis views the symptoms of psychopathology as a unique source of stress that may contribute to the development and maintenance of disordered states.

Mistakenly categorizing one type of thing as another can lead to erroneous—and sometimes paranormal—beliefs.

How many common teaching techniques have actually been tested? Of those that have been tested, what were the results? The answers may surprise you. They surprised this educator!

The replication crisis, publication bias, and careerism undermine scientific rigor and ethical responsibility in counseling to provide effective and safe care for clients.

The human brain has two halves. A new study highlights when differences between them start.

When considered across a lifetime, no within-person association exists between religiosity and psychological well-being.

What are the prevalence rates of psychosis for displaced refugees?

A recent review provides compelling evidence that arts engagement significantly reduces cognitive decline and enhances the quality of life among healthy older adults.

Personal Perspective: Mental healthcare AI is evolving beyond administrative roles. By automating routine tasks, therapists can spend sessions focusing on human interactions.

Investing in building a positive classroom climate holds benefits for students and teachers alike.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

A Guide to Conducting a Meta-Analysis

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, National University of Singapore, Block AS4, Level 2, 9 Arts Link, Singapore, 117570, Singapore. [email protected].

- 2 Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, National University of Singapore, Block AS4, Level 2, 9 Arts Link, Singapore, 117570, Singapore.

- PMID: 27209412

- DOI: 10.1007/s11065-016-9319-z

Meta-analysis is widely accepted as the preferred method to synthesize research findings in various disciplines. This paper provides an introduction to when and how to conduct a meta-analysis. Several practical questions, such as advantages of meta-analysis over conventional narrative review and the number of studies required for a meta-analysis, are addressed. Common meta-analytic models are then introduced. An artificial dataset is used to illustrate how a meta-analysis is conducted in several software packages. The paper concludes with some common pitfalls of meta-analysis and their solutions. The primary goal of this paper is to provide a summary background to readers who would like to conduct their first meta-analytic study.

Keywords: Literature review; Meta-analysis; Moderator analysis; Systematic review.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Data Interpretation, Statistical

- Meta-Analysis as Topic*

- Publication Bias

- Review Literature as Topic

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Practical Guide to Meta-analysis

- 1 Stanford-Surgery Policy Improvement, Research and Education (S-SPIRE) Center, Palo Alto, California

- 2 Department of Biostatistics, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill

- 3 Department of Surgery, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

- Editorial Maximizing the Impact of Surgical Health Services Research Amir A. Ghaferi, MD, MS; Adil H. Haider, MD, MPH; Melina R. Kibbe, MD JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Qualitative Analysis Margaret L. Schwarze, MD, MPP; Amy H. Kaji, MD, PhD; Amir A. Ghaferi, MD, MS JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Mixed Methods Lesly A. Dossett, MD, MPH; Amy H. Kaji, MD, PhD; Justin B. Dimick, MD, MPH JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Cost-effectiveness Analysis Benjamin S. Brooke, MD, PhD; Amy H. Kaji, MD, PhD; Kamal M. F. Itani, MD JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Comparative Effectiveness Research Using Observational Data Ryan P. Merkow, MD, MS; Todd A. Schwartz, DrPH; Avery B. Nathens, MD, MPH, PhD JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Health Policy Evaluation Using Observational Data John W. Scott, MD, MPH; Todd A. Schwartz, DrPH; Justin B. Dimick, MD, MPH JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Survey Research Karen Brasel, MD, MPH; Adil Haider, MD, MPH; Jason Haukoos, MD, MSc JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Assessment of Patient-Reported Outcomes Giana H. Davidson, MD, MPH; Jason S. Haukoos, MD, MSc; Liane S. Feldman, MD JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Implementation Science Heather B. Neuman, MD, MS; Amy H. Kaji, MD, PhD; Elliott R. Haut, MD, PhD JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Decision Analysis Dorry L. Segev, MD, PhD; Jason S. Haukoos, MD, MSc; Timothy M. Pawlik, MD, MPH, PhD JAMA Surgery

Meta-analysis is a systematic approach of synthesizing, combining, and analyzing data from multiple studies (randomized clinical trials 1 or observational studies 2 ) into a single effect estimate to answer a research question. Meta-analysis is especially useful if there is debate around the research question in the literature published to date or the individual published studies are underpowered. Vital to a high-quality meta-analysis is a comprehensive literature search, prespecified hypothesis and aims, reporting of study quality, consideration of heterogeneity and examination of bias. In the hierarchy of evidence, meta-analysis appears above observational studies and randomized clinical trials because it rigorously collates evidence across a larger body of literature; however, meta-analysis is largely dependent on the quality of the primary data.

- Editorial Maximizing the Impact of Surgical Health Services Research JAMA Surgery

Read More About

Arya S , Schwartz TA , Ghaferi AA. Practical Guide to Meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(5):430–431. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2019.4523

Manage citations:

© 2024

Surgery in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Digital Health

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology