Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 08 September 2024

Longitudinal analysis of teacher self-efficacy evolution during a STEAM professional development program: a qualitative case study

- Haozhe Jiang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7870-0993 1 ,

- Ritesh Chugh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0061-7206 2 ,

- Xuesong Zhai ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4179-7859 1 , 3 nAff7 ,

- Ke Wang 4 &

- Xiaoqin Wang 5 , 6

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 1162 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Despite the widespread advocacy for the integration of arts and humanities (A&H) into science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education on an international scale, teachers face numerous obstacles in practically integrating A&H into STEM teaching (IAT). To tackle the challenges, a comprehensive five-stage framework for teacher professional development programs focussed on IAT has been developed. Through the use of a qualitative case study approach, this study outlines the shifts in a participant teacher’s self-efficacy following their exposure to each stage of the framework. The data obtained from interviews and reflective analyses were analyzed using a seven-stage inductive method. The findings have substantiated the significant impact of a teacher professional development program based on the framework on teacher self-efficacy, evident in both individual performance and student outcomes observed over eighteen months. The evolution of teacher self-efficacy in IAT should be regarded as an open and multi-level system, characterized by interactions with teacher knowledge, skills and other entrenched beliefs. Building on our research findings, an enhanced model of teacher professional learning is proposed. The revised model illustrates that professional learning for STEAM teachers should be conceived as a continuous and sustainable process, characterized by the dynamic interaction among teaching performance, teacher knowledge, and teacher beliefs. The updated model further confirms the inseparable link between teacher learning and student learning within STEAM education. This study contributes to the existing body of literature on teacher self-efficacy, teacher professional learning models and the design of IAT teacher professional development programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Primary and secondary school teachers’ perceptions of their social science training needs

Investigating how subject teachers transition to integrated STEM education: A hybrid qualitative study on primary and middle school teachers

The mediating role of teaching enthusiasm in the relationship between mindfulness, growth mindset, and psychological well-being of Chinese EFL teachers

Introduction.

In the past decade, there has been a surge in the advancement and widespread adoption of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) education on a global scale (Jiang et al. 2021 ; Jiang et al. 2022 ; Jiang et al. 2023 ; Jiang et al. 2024a , b ; Zhan et al. 2023 ; Zhan and Niu 2023 ; Zhong et al. 2022 ; Zhong et al. 2024 ). Concurrently, there has been a growing chorus of advocates urging the integration of Arts and Humanities (A&H) into STEM education (e.g., Alkhabra et al. 2023 ; Land 2020 ; Park and Cho 2022 ; Uştu et al. 2021 ; Vaziri and Bradburn 2021 ). STEM education is frequently characterized by its emphasis on logic and analysis; however, it may be perceived as deficient in emotional and intuitive elements (Ozkan and Umdu Topsakal 2021 ). Through the integration of Arts and Humanities (A&H), the resulting STEAM approach has the potential to become more holistic, incorporating both rationality and emotional intelligence (Ozkan and Umdu Topsakal 2021 ). Many studies have confirmed that A&H can help students increase interest and develop their understanding of the contents in STEM fields, and thus, A&H can attract potential underrepresented STEM learners such as female students and minorities (Land 2020 ; Park and Cho 2022 ; Perignat and Katz-Buonincontro 2019 ). Despite the increasing interest in STEAM, the approaches to integrating A&H, which represent fundamentally different disciplines, into STEM are theoretically and practically ambiguous (Jacques et al. 2020 ; Uştu et al. 2021 ). Moreover, studies have indicated that the implementation of STEAM poses significant challenges, with STEM educators encountering difficulties in integrating A&H into their teaching practices (e.g., Boice et al. 2021 ; Duong et al. 2024 ; Herro et al. 2019 ; Jacques et al. 2020 ; Park and Cho 2022 ; Perignat and Katz-Buonincontro 2019 ). Hence, there is a pressing need to provide STEAM teachers with effective professional training.

Motivated by this gap, this study proposes a novel five-stage framework tailored for teacher professional development programs specifically designed to facilitate the integration of A&H into STEM teaching (IAT). Following the establishment of this framework, a series of teacher professional development programs were implemented. To explain the framework, a qualitative case study is employed, focusing on examining a specific teacher professional development program’s impact on a pre-service teacher’s self-efficacy. The case narratives, with a particular focus on the pre-service teacher’s changes in teacher self-efficacy, are organized chronologically, delineating stages before and after each stage of the teacher professional development program. More specifically, meaningful vignettes of the pre-service teacher’s learning and teaching experiences during the teacher professional development program are offered to help understand the five-stage framework. This study contributes to understanding teacher self-efficacy, teacher professional learning model and the design of IAT teacher professional development programs.

Theoretical background

The conceptualization of steam education.

STEM education can be interpreted through various lenses (e.g., Jiang et al. 2021 ; English 2016 ). As Li et al. (2020) claimed, on the one hand, STEM education can be defined as individual STEM disciplinary-based education (i.e., science education, technology education, engineering education and mathematics education). On the other hand, STEM education can also be defined as interdisciplinary or cross-disciplinary education where individual STEM disciplines are integrated (Jiang et al. 2021 ; English 2016 ). In this study, we view it as individual disciplinary-based education separately in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (English 2016 ).

STEAM education emerged as a new pedagogy during the Americans for the Arts-National Policy Roundtable discussion in 2007 (Perignat and Katz-Buonincontro 2019 ). This pedagogy was born out of the necessity to enhance students’ engagement, foster creativity, stimulate innovation, improve problem-solving abilities, and cultivate employability skills such as teamwork, communication and adaptability (Perignat and Katz-Buonincontro 2019 ). In particular, within the framework of STEAM education, the ‘A’ should be viewed as a broad concept that represents arts and humanities (A&H) (Herro and Quigley 2016 ; de la Garza 2021 , Park and Cho 2022 ). This conceptualization emphasizes the need to include humanities subjects alongside arts (Herro and Quigley 2016 ; de la Garza 2021 ; Park and Cho 2022 ). Sanz-Camarero et al. ( 2023 ) listed some important fields of A&H, including physical arts, fine arts, manual arts, sociology, politics, philosophy, history, psychology and so on.

In general, STEM education does not necessarily entail the inclusion of all STEM disciplines collectively (Ozkan and Umdu Topsakal 2021 ), and this principle also applies to STEAM education (Gates 2017 ; Perignat and Katz-Buonincontro 2019 ; Quigley et al. 2017 ; Smith and Paré 2016 ). As an illustration, Smith and Paré ( 2016 ) described a STEAM activity in which pottery (representing A&H) and mathematics were integrated, while other STEAM elements such as science, technology and engineering were not included. In our study, STEAM education is conceptualized as an interdisciplinary approach that involves the integration of one or more components of A&H into one or more STEM school subjects within educational activities (Ozkan and Umdu Topsakal 2021 ; Vaziri and Bradburn 2021 ). Notably, interdisciplinary collaboration entails integrating one or more elements from arts and humanities (A&H) with one or more STEM school subjects, cohesively united by a shared theme while maintaining their distinct identities (Perignat and Katz-Buonincontro 2019 ).

In our teacher professional development programs, we help mathematics, technology, and science pre-service teachers integrate one component of A&H into their disciplinary-based teaching practices. For instance, we help mathematics teachers integrate history (a component of A&H) into mathematics teaching. In other words, in our study, integrating A&H into STEM teaching (IAT) can be defined as integrating one component of A&H into the teaching of one of the STEM school subjects. The components of A&H and the STEM school subject are brought together under a common theme, but each of them remains discrete. Engineering is not taught as an individual subject in the K-12 curriculum in mainland China. Therefore, A&H is not integrated into engineering teaching in our teacher professional development programs.

Self-efficacy and teacher self-efficacy

Self-efficacy was initially introduced by Bandura ( 1977 ) as a key concept within his social cognitive theory. Bandura ( 1997 ) defined self-efficacy as “people’s beliefs about their capabilities to produce designated levels of performance that exercise influence over events that affect their lives” (p. 71). Based on Bandura’s ( 1977 ) theory, Tschannen-Moran et al. ( 1998 ) defined the concept of teacher self-efficacy Footnote 1 as “a teacher’s belief in her or his ability to organize and execute the courses of action required to successfully accomplish a specific teaching task in a particular context” (p. 233). Blonder et al. ( 2014 ) pointed out that this definition implicitly included teachers’ judgment of their ability to bring about desired outcomes in terms of students’ engagement and learning. Moreover, OECD ( 2018 ) defined teacher self-efficacy as “the beliefs that teachers have of their ability to enact certain teaching behavior that influences students’ educational outcomes, such as achievement, interest, and motivation” (p. 51). This definition explicitly included two dimensions: teachers’ judgment of the ability related to their teaching performance (i.e., enacting certain teaching behavior) and their influence on student outcomes.

It is argued that teacher self-efficacy should not be regarded as a general or overarching construct (Zee et al. 2017 ; Zee and Koomen 2016 ). Particularly, in the performance-driven context of China, teachers always connect their beliefs in their professional capabilities with the educational outcomes of their students (Liu et al. 2018 ). Therefore, we operationally conceptualize teacher self-efficacy as having two dimensions: self-efficacy in individual performance and student outcomes (see Table 1 ).

Most importantly, given its consistent association with actual teaching performance and student outcomes (Bray-Clark and Bates 2003 ; Kelley et al. 2020 ), teacher self-efficacy is widely regarded as a pivotal indicator of teacher success (Kelley et al. 2020 ). Moreover, the enhancement of teaching self-efficacy reflects the effectiveness of teacher professional development programs (Bray-Clark and Bates 2003 ; Kelley et al. 2020 ; Wong et al. 2022 ; Zhou et al. 2023 ). For instance, Zhou et al. ( 2023 ) claimed that in STEM teacher education, effective teacher professional development programs should bolster teachers’ self-efficacy “in teaching the content in the STEM discipline” (p. 2).

It has been documented that teachers frequently experience diminished confidence and comfort when teaching subject areas beyond their expertise (Kelley et al. 2020 ; Stohlmann et al. 2012 ). This diminished confidence extends to their self-efficacy in implementing interdisciplinary teaching approaches, such as integrated STEM teaching and IAT (Kelley et al. 2020 ). For instance, Geng et al. ( 2019 ) found that STEM teachers in Hong Kong exhibited low levels of self-efficacy, with only 5.53% of teachers rating their overall self-efficacy in implementing STEM education as higher than a score of 4 out of 5. Additionally, Hunter-Doniger and Sydow ( 2016 ) found that teachers may experience apprehension and lack confidence when incorporating A&H elements into the classroom context, particularly within the framework of IAT. Considering the critical importance of teacher self-efficacy in STEM and STEAM education (Kelley et al. 2020 ; Zakariya, 2020 ; Zhou et al. 2023 ), it is necessary to explore effective measures, frameworks and teacher professional development programs to help teachers improve their self-efficacy regarding interdisciplinary teaching (e.g., IAT).

Teacher professional learning models

The relationship between teachers’ professional learning and students’ outcomes (such as achievements, skills and attitudes) has been a subject of extensive discussion and research for many years (Clarke and Hollingsworth 2002 ). For instance, Clarke and Hollingsworth ( 2002 ) proposed and validated the Interconnected Model of Professional Growth, which illustrates that teacher professional development is influenced by the interaction among four interconnected domains: the personal domain (teacher knowledge, beliefs and attitudes), the domain of practice (professional experimentation), the domain of consequence (salient outcomes), and the external domain (sources of information, stimulus or support). Sancar et al. ( 2021 ) emphasized that teachers’ professional learning or development never occurs independently. In practice, this process is inherently intertwined with many variables, including student outcomes, in various ways (Sancar et al. 2021 ). However, many current teacher professional development programs exclude real in-class teaching and fail to establish a comprehensive link between teachers’ professional learning and student outcomes (Cai et al. 2020 ; Sancar et al. 2021 ). Sancar et al. ( 2021 ) claimed that exploring the complex relationships between teachers’ professional learning and student outcomes should be grounded in monitoring and evaluating real in-class teaching, rather than relying on teachers’ self-assessment. It is essential to understand these relationships from a holistic perspective within the context of real classroom teaching (Sancar et al. 2021 ). However, as Sancar et al. ( 2021 ) pointed out, such efforts in teacher education are often considered inadequate. Furthermore, in the field of STEAM education, such efforts are further exacerbated.

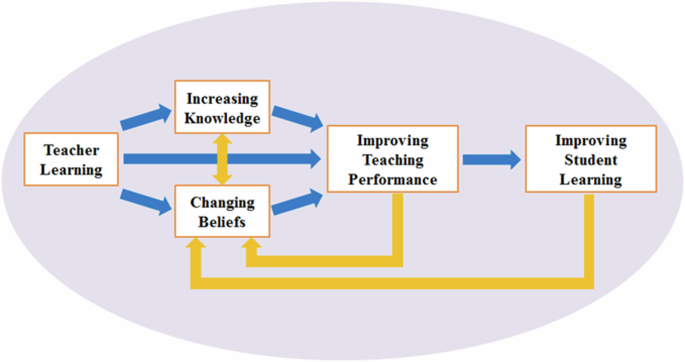

Cai et al. ( 2020 ) proposed a teacher professional learning model where student outcomes are emphasized. This model was developed based on Cai ( 2017 ), Philipp ( 2007 ) and Thompson ( 1992 ). It has also been used and justified in a series of teacher professional development programs (e.g., Calabrese et al. 2024 ; Hwang et al. 2024 ; Marco and Palatnik 2024 ; Örnek and Soylu 2021 ). The model posits that teachers typically increase their knowledge and modify their beliefs through professional teacher learning, subsequently improving their classroom instruction, enhancing teaching performance, and ultimately fostering improved student learning outcomes (Cai et al. 2020 ). Notably, this model can be updated in several aspects. Firstly, prior studies have exhibited the interplay between teacher knowledge and beliefs (e.g., Basckin et al. 2021 ; Taimalu and Luik 2019 ). This indicates that the increase in teacher knowledge and the change in teacher belief may not be parallel. The two processes can be intertwined. Secondly, the Interconnected Model of Professional Growth highlights that the personal domain and the domain of practice are interconnected (Clarke and Hollingsworth 2002 ). Liu et al. ( 2022 ) also confirmed that improvements in classroom instruction may, in turn, influence teacher beliefs. This necessitates a reconsideration of the relationships between classroom instruction, teacher knowledge and teacher beliefs in Cai et al.’s ( 2020 ) model. Thirdly, the Interconnected Model of Professional Growth also exhibits the connections between the domain of consequence and the personal domain (Clarke and Hollingsworth 2002 ). Hence, the improvement of learning outcomes may signify the end of teacher learning. For instance, students’ learning feedback may be a vital source of teacher self-efficacy (Bandura 1977 ). Therefore, the improvement of student outcomes may, in turn, affect teacher beliefs. The aforementioned arguments highlight the need for an updated model that integrates Cai et al.’s ( 2020 ) teacher professional learning model with Clarke and Hollingsworth’s ( 2002 ) Interconnected Model of Professional Growth. This integration may provide a holistic view of the teacher’s professional learning process, especially within the complex contexts of STEAM teacher education.

The framework for teacher professional development programs of integrating arts and humanities into STEM teaching

In this section, we present a framework for IAT teacher professional development programs, aiming to address the practical challenges associated with STEAM teaching implementation. Our framework incorporates the five features of effective teacher professional development programs outlined by Archibald et al. ( 2011 ), Cai et al. ( 2020 ), Darling-Hammond et al. ( 2017 ), Desimone and Garet ( 2015 ) and Roth et al. ( 2017 ). These features include: (a) alignment with shared goals (e.g., school, district, and national policies and practice), (b) emphasis on core content and modeling of teaching strategies for the content, (c) collaboration among teachers within a community, (d) adequate opportunities for active learning of new teaching strategies, and (e) embedded follow-up and continuous feedback. It is worth noting that two concepts, namely community of practice and lesson study, have been incorporated into our framework. Below, we delineate how these features are reflected in our framework.

(a) The Chinese government has issued a series of policies to facilitate STEAM education in K-12 schools (Jiang et al. 2021 ; Li and Chiang 2019 ; Lyu et al. 2024 ; Ro et al. 2022 ). The new curriculum standards released in 2022 mandate that all K-12 teachers implement interdisciplinary teaching, including STEAM education. Our framework for teacher professional development programs, which aims to help teachers integrate A&H into STEM teaching, closely aligns with these national policies and practices supporting STEAM education in K-12 schools.

(b) The core content of the framework is IAT. Specifically, as A&H is a broad concept, we divide it into several subcomponents, such as history, culture, and visual and performing arts (e.g., drama). We are implementing a series of teacher professional development programs to help mathematics, technology and science pre-service teachers integrate these subcomponents of A&H into their teaching Footnote 2 . Notably, pre-service teachers often lack teaching experience, making it challenging to master and implement new teaching strategies. Therefore, our framework provides five step-by-step stages designed to help them effectively model the teaching strategies of IAT.

(c) Our framework advocates for collaboration among teachers within a community of practice. Specifically, a community of practice is “a group of people who share an interest in a domain of human endeavor and engage in a process of collective learning that creates bonds between them” (Wenger et al. 2002 , p. 1). A teacher community of practice can be considered a group of teachers “sharing and critically observing their practices in growth-promoting ways” (Näykki et al. 2021 , p. 497). Long et al. ( 2021 ) claimed that in a teacher community of practice, members collaboratively share their teaching experiences and work together to address teaching problems. Our community of practice includes three types of members. (1) Mentors: These are professors and experts with rich experience in helping pre-service teachers practice IAT. (2) Pre-service teachers: Few have teaching experience before the teacher professional development programs. (3) In-service teachers: All in-service teachers are senior teachers with rich teaching experience. All the members work closely together to share and improve their IAT practice. Moreover, our community includes not only mentors and in-service teachers but also pre-service teachers. We encourage pre-service teachers to collaborate with experienced in-service teachers in various ways, such as developing IAT lesson plans, writing IAT case reports and so on. In-service teachers can provide cognitive and emotional support and share their practical knowledge and experience, which may significantly benefit the professional growth of pre-service teachers (Alwafi et al. 2020 ).

(d) Our framework offers pre-service teachers various opportunities to engage in lesson study, allowing them to actively design and implement IAT lessons. Based on the key points of effective lesson study outlined by Akiba et al. ( 2019 ), Ding et al. ( 2024 ), and Takahashi and McDougal ( 2016 ), our lesson study incorporates the following seven features. (1) Study of IAT materials: Pre-service teachers are required to study relevant IAT materials under the guidance of mentors. (2) Collaboration on lesson proposals: Pre-service teachers should collaborate with in-service teachers to develop comprehensive lesson proposals. (3) Observation and data collection: During the lesson, pre-service teachers are required to carefully observe and collect data on student learning and development. (4) Reflection and analysis: Pre-service teachers use the collected data to reflect on the lesson and their teaching effects. (5) Lesson revision and reteaching: If needed, pre-service teachers revise and reteach the lesson based on their reflections and data analysis. (6) Mentor and experienced in-service teacher involvement: Mentors and experienced in-service teachers, as knowledgeable others, are involved throughout the lesson study process. (7) Collaboration on reporting: Pre-service teachers collaborate with in-service teachers to draft reports and disseminate the results of the lesson study. Specifically, recognizing that pre-service teachers often lack teaching experience, we do not require them to complete all the steps of lesson study independently at once. Instead, we guide them through the lesson study process in a step-by-step manner, allowing them to gradually build their IAT skills and confidence. For instance, in Stage 1, pre-service teachers primarily focus on studying IAT materials. In Stage 2, they develop lesson proposals, observe and collect data, and draft reports. However, the implementation of IAT lessons is carried out by in-service teachers. This approach prevents pre-service teachers from experiencing failures due to their lack of teaching experience. In Stage 3, pre-service teachers implement, revise, and reteach IAT lessons, experiencing the lesson study process within a simulated environment. In Stage 4, pre-service teachers engage in lesson study in an actual classroom environment. However, their focus is limited to one micro-course during each lesson study session. It is not until the fifth stage that they experience a complete lesson study in an actual classroom environment.

(e) Our teacher professional development programs incorporate assessments specifically designed to evaluate pre-service teachers’ IAT practices. We use formative assessments to measure their understanding and application of IAT strategies. Pre-service teachers receive ongoing and timely feedback from peers, mentors, in-service teachers, and students, which helps them continuously refine their IAT practices throughout the program. Recognizing that pre-service teachers often have limited contact with real students and may not fully understand students’ learning needs, processes and outcomes, our framework requires them to actively collect and analyze student feedback. By doing so, they can make informed improvements to their instructional practice based on student feedback.

After undergoing three rounds of theoretical and practical testing and revision over the past five years, we have successfully finalized the optimization of the framework design (Zhou 2021 ). Throughout each cycle, we collected feedback from both participants and researchers on at least three occasions. Subsequently, we analyzed this feedback and iteratively refined the framework. For example, we enlisted the participation of in-service teachers to enhance the implementation of STEAM teaching, extended practice time through micro-teaching sessions, and introduced a stage of micro-course development within the framework to provide more opportunities for pre-service teachers to engage with real teaching situations. In this process, we continuously improved the coherence between each stage of the framework, ensuring that they mutually complement one another. The five-stage framework is described as follows.

Stage 1 Literature study

Pre-service teachers are provided with a series of reading materials from A&H. On a weekly basis, two pre-service teachers are assigned to present their readings and reflections to the entire group, followed by critical discussions thereafter. Mentors and all pre-service teachers discuss and explore strategies for translating the original A&H materials into viable instructional resources suitable for classroom use. Subsequently, pre-service teachers select topics of personal interest for further study under mentor guidance.

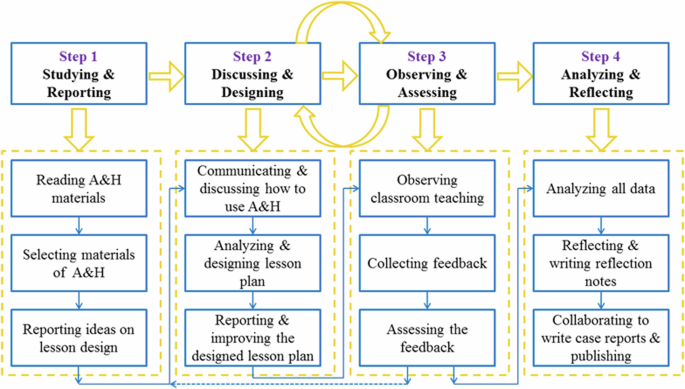

Stage 2 Case learning

Given that pre-service teachers have no teaching experience, collaborative efforts between in-service teachers and pre-service teachers are undertaken to design IAT lesson plans. Subsequently, the in-service teachers implement these plans. Throughout this process, pre-service teachers are afforded opportunities to engage in lesson plan implementation. Figure 1 illustrates the role of pre-service teachers in case learning. In the first step, pre-service teachers read about materials related to A&H, select suitable materials, and report their ideas on IAT lesson design to mentors, in-service teachers, and fellow pre-service teachers.

Note: A&H refers to arts and humanities.

In the second step, they liaise with the in-service teachers responsible for implementing the lesson plan, discussing the integration of A&H into teaching practices. Pre-service teachers then analyze student learning objectives aligned with curriculum standards, collaboratively designing the IAT lesson plan with in-service teachers. Subsequently, pre-service teachers present lesson plans for feedback from mentors and other in-service teachers.

In the third step, pre-service teachers observe the lesson plan’s implementation, gathering and analyzing feedback from students and in-service teachers using an inductive approach (Merriam 1998 ). Feedback includes opinions on the roles and values of A&H, perceptions of the teaching effect, and recommendations for lesson plan implementation and modification. The second and third steps may iterate multiple times to refine the IAT lesson plan. In the fourth step, pre-service teachers consolidate all data, including various versions of teaching instructions, classroom videos, feedback, and discussion notes, composing reflection notes. Finally, pre-service teachers collaborate with in-service teachers to compile the IAT case report and submit it for publication.

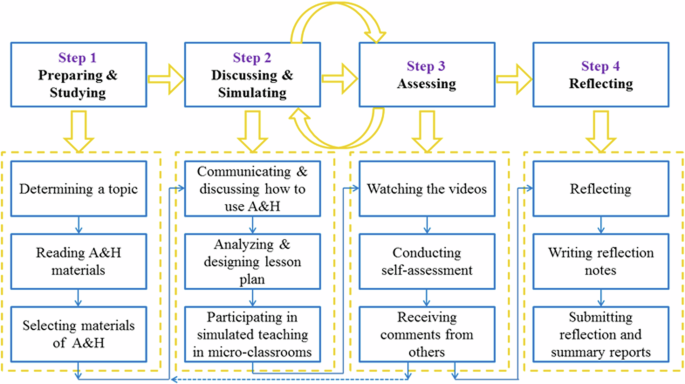

Stage 3 Micro-teaching

Figure 2 illustrates the role of pre-service teachers in micro-teaching. Before entering the micro-classrooms Footnote 3 , all the discussions and communications occur within the pre-service teacher group, excluding mentors and in-service teachers. After designing the IAT lesson plan, pre-service teachers take turns implementing 40-min lesson plans in a simulated micro-classroom setting. Within this simulated environment, one pre-service teacher acts as the teacher, while others, including mentors, in-service teachers, and other fellow pre-service teachers, assume the role of students Footnote 4 . Following the simulated teaching, the implementer reviews the video of their session and self-assesses their performance. Subsequently, the implementer receives feedback from other pre-service teachers, mentors, and in-service teachers. Based on this feedback, the implementer revisits steps 2 and 3, revising the lesson plan and conducting the simulated teaching again. This iterative process typically repeats at least three times until the mentors, in-service teachers, and other pre-service teachers are satisfied with the implementation of the revised lesson plan. Finally, pre-service teachers complete reflection notes and submit a summary of their reflections on the micro-teaching experience. Each pre-service teacher is required to choose at least three topics and undergo at least nine simulated teaching sessions.

Stage 4 Micro-course development

While pre-service teachers may not have the opportunity to execute the whole lesson plans in real classrooms, they can design and create five-minute micro-courses Footnote 5 before class, subsequently presenting these videos to actual students. The process of developing micro-courses closely mirrors that of developing IAT cases in the case learning stage (see Fig. 1 ). However, in Step 3, pre-service teachers assume dual roles, not only as observers of IAT lesson implementation but also as implementers of a five-minute IAT micro-course.

Stage 5 Classroom teaching

Pre-service teachers undertake the implementation of IAT lesson plans independently, a process resembling micro-teaching (see Fig. 2 ). However, pre-service teachers engage with real school students in partner schools Footnote 6 instead of simulated classrooms. Furthermore, they collect feedback not only from the mentors, in-service teachers, and fellow pre-service teachers but also from real students.

To provide our readers with a better understanding of the framework, we provide meaningful vignettes of a pre-service teacher’s learning and teaching experiences in one of the teacher professional development programs based on the framework. In addition, we choose teacher self-efficacy as an indicator to assess the framework’s effectiveness, detailing the pre-service teacher’s changes in teacher self-efficacy.

Research design

Research method.

Teacher self-efficacy can be measured both quantitatively and qualitatively (Bandura 1986 , 1997 ; Lee and Bobko 1994 ; Soprano and Yang 2013 ; Unfried et al. 2022 ). However, researchers and theorists in the area of teacher self-efficacy have called for more qualitative and longitudinal studies (Klassen et al. 2011 ). As some critiques stated, most studies were based on correlational and cross-sectional data obtained from self-report surveys, and qualitative studies of teacher efficacy were overwhelmingly neglected (Henson 2002 ; Klassen et al. 2011 ; Tschannen-Moran et al. 1998 ; Xenofontos and Andrews 2020 ). There is an urgent need for more longitudinal studies to shed light on the development of teacher efficacy (Klassen et al. 2011 ; Xenofontos and Andrews 2020 ).

This study utilized a longitudinal qualitative case study methodology to delve deeply into the context (Jiang et al. 2021 ; Corden and Millar 2007 ; Dicks et al. 2023 ; Henderson et al. 2012 ; Matusovich et al. 2010 ; Shirani and Henwood 2011 ), presenting details grounded in real-life situations and analyzing the inner relationships rather than generalize findings about the change of a large group of pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy.

Participant

This study forms a component of a broader multi-case research initiative examining teachers’ professional learning in the STEAM teacher professional development programs in China (Jiang et al. 2021 ; Wang et al. 2018 ; Wang et al. 2024 ). Within this context, one participant, Shuitao (pseudonym), is selected and reported in this current study. Shuitao was a first-year graduate student at a first-tier Normal university in Shanghai, China. Normal universities specialize in teacher education. Her graduate major was mathematics curriculum and instruction. Teaching practice courses are offered to students in this major exclusively during their third year of study. The selection of Shuitao was driven by three primary factors. Firstly, Shuitao attended the entire teacher professional development program and actively engaged in nearly all associated activities. Table 2 illustrates the timeline of the five stages in which Shuitao was involved. Secondly, her undergraduate major was applied mathematics, which was not related to mathematics teaching Footnote 7 . She possessed no prior teaching experience and had not undergone any systematic study of IAT before her involvement in the teacher professional development program. Thirdly, her other master’s courses during her first two years of study focused on mathematics education theory and did not include IAT Footnote 8 . Additionally, she scarcely participated in any other teaching practice outside of the teacher professional development program. As a pre-service teacher, Shuitao harbored a keen interest in IAT. Furthermore, she discovered that she possessed fewer teaching skills compared to her peers who had majored in education during their undergraduate studies. Hence, she had a strong desire to enhance her teaching skills. Consequently, Shuitao decided to participate in our teacher professional development program.

Shuitao was grouped with three other first-year graduate students during the teacher professional development program. She actively collaborated with them at every stage of the program. For instance, they advised each other on their IAT lesson designs, observed each other’s IAT practice and offered constructive suggestions for improvement.

Research question

Shuitao was a mathematics pre-service teacher who participated in one of our teacher professional development programs, focusing on integrating history into mathematics teaching (IHT) Footnote 9 . Notably, this teacher professional development program was designed based on our five-stage framework for teacher professional development programs of IAT. To examine the impact of this teacher professional development program on Shuitao’s self-efficacy related to IHT, this case study addresses the following research question:

What changes in Shuitao’s self-efficacy in individual performance regarding integrating history into mathematics teaching (SE-IHT-IP) may occur through participation in the teacher professional development program?

What changes in Shuitao’s self-efficacy in student outcomes regarding integrating history into mathematics teaching (SE-IHT-SO) may occur through participation in the teacher professional development program?

Data collection and analysis

Before Shuitao joined the teacher professional development program, a one-hour preliminary interview was conducted to guide her in self-narrating her psychological and cognitive state of IHT.

During the teacher professional development program, follow-up unstructured interviews were conducted once a month with Shuitao. All discussions in the development of IHT cases were recorded, Shuitao’s teaching and micro-teaching were videotaped, and the reflection notes, journals, and summary reports written by Shuitao were collected.

After completing the teacher professional development program, Shuitao participated in a semi-structured three-hour interview. The objectives of this interview were twofold: to reassess her self-efficacy and to explore the relationship between her self-efficacy changes and each stage of the teacher professional development program.

Interview data, discussions, reflection notes, journals, summary reports and videos, and analysis records were archived and transcribed before, during, and after the teacher professional development program.

In this study, we primarily utilized data from seven interviews: one conducted before the teacher professional development program, five conducted after each stage of the program, and one conducted upon completion of the program. Additionally, we reviewed Shuitao’s five reflective notes, which were written after each stage, as well as her final summary report that encompassed the entire teacher professional development program.

Merriam’s ( 1998 ) approach to coding data and inductive approach to retrieving possible concepts and themes were employed using a seven-stage method. Considering theoretical underpinnings in qualitative research is common when interpreting data (Strauss and Corbin 1990 ). First, a list based on our conceptual framework of teacher self-efficacy (see Table 1 ) was developed. The list included two codes (i.e., SE-IHT-IP and SE-IHT-SO). Second, all data were sorted chronologically, read and reread to be better understood. Third, texts were coded into multi-colored highlighting and comment balloons. Fourth, the data for groups of meanings, themes, and behaviors were examined. How these groups were connected within the conceptual framework of teacher self-efficacy was confirmed. Fifth, after comparing, confirming, and modifying, the selective codes were extracted and mapped onto the two categories according to the conceptual framework of teacher self-efficacy. Accordingly, changes in SE-IHT-IP and SE-IHT-SO at the five stages of the teacher professional development program were identified, respectively, and then the preliminary findings came (Strauss and Corbin 1990 ). In reality, in Shuitao’s narratives, SE-IHT-IP and SE-IHT-SO were frequently intertwined. Through our coding process, we differentiated between SE-IHT-IP and SE-IHT-SO, enabling us to obtain a more distinct understanding of how these two aspects of teacher self-efficacy evolved over time. This helped us address the two research questions effectively.

Reliability and validity

Two researchers independently analyzed the data to establish inter-rater reliability. The inter-rater reliability was established as kappa = 0.959. Stake ( 1995 ) suggested that the most critical assertions in a study require the greatest effort toward confirmation. In this study, three methods served this purpose and helped ensure the validity of the findings. The first way to substantiate the statement about the changes in self-efficacy was by revisiting each transcript to confirm whether the participant explicitly acknowledged the changes (Yin 2003 ). Such a check was repeated in the analysis of this study. The second way to confirm patterns in the data was by examining whether Shuitao’s statements were replicated in separate interviews (Morris and Usher 2011 ). The third approach involved presenting the preliminary conclusions to Shuitao and affording her the opportunity to provide feedback on the data and conclusions. This step aimed to ascertain whether we accurately grasped the true intentions of her statements and whether our subjective interpretations inadvertently influenced our analysis of her statements. Additionally, data from diverse sources underwent analysis by at least two researchers, with all researchers reaching consensus on each finding.

As each stage of our teacher professional development programs spanned a minimum of three months, numerous documented statements regarding the enhancement of Shuitao’s self-efficacy regarding IHT were recorded. Notably, what we present here offers only a concise overview of findings derived from our qualitative analysis. The changes in Shuitao’s SE-IHT-IP and SE-IHT-SO are organized chronologically, delineating the period before and during the teacher professional development program.

Before the teacher professional development program: “I have no confidence in IHT”

Before the teacher professional development program, Shuitao frequently expressed her lack of confidence in IHT. On the one hand, Shuitao expressed considerable apprehension about her individual performance in IHT. “How can I design and implement IHT lesson plans? I do not know anything [about it]…” With a sense of doubt, confusion and anxiety, Shuitao voiced her lack of confidence in her ability to design and implement an IHT case that would meet the requirements of the curriculum standards. Regarding the reasons for her lack of confidence, Shuitao attributed it to her insufficient theoretical knowledge and practical experience in IHT:

I do not know the basic approaches to IHT that I could follow… it is very difficult for me to find suitable historical materials… I am very confused about how to organize [historical] materials logically around the teaching goals and contents… [Furthermore,] I am [a] novice, [and] I have no IHT experience.

On the other hand, Shuitao articulated very low confidence in the efficacy of her IHT on student outcomes:

I think my IHT will have a limited impact on student outcomes… I do not know any specific effects [of history] other than making students interested in mathematics… In fact, I always think it is difficult for [my] students to understand the history… If students cannot understand [the history], will they feel bored?

This statement suggests that Shuitao did not fully grasp the significance of IHT. In fact, she knew little about the educational significance of history for students, and she harbored no belief that her IHT approach could positively impact students. In sum, her SE-IHT-SO was very low.

After stage 1: “I can do well in the first step of IHT”

After Stage 1, Shuitao indicated a slight improvement in her confidence in IHT. She attributed this improvement to her acquisition of theoretical knowledge in IHT, the approaches for selecting history-related materials, and an understanding of the educational value of history.

One of Shuitao’s primary concerns about implementing IHT before the teacher professional development program was the challenge of sourcing suitable history-related materials. However, after Stage 1, Shuitao explicitly affirmed her capability in this aspect. She shared her experience of organizing history-related materials related to logarithms as an example.

Recognizing the significance of suitable history-related materials in effective IHT implementation, Shuitao acknowledged that conducting literature studies significantly contributed to enhancing her confidence in undertaking this initial step. Furthermore, she expressed increased confidence in designing IHT lesson plans by utilizing history-related materials aligned with teaching objectives derived from the curriculum standards. In other words, her SE-IHT-IP was enhanced. She said:

After experiencing multiple discussions, I gradually know more about what kinds of materials are essential and should be emphasized, what kinds of materials should be adapted, and what kinds of materials should be omitted in the classroom instructions… I have a little confidence to implement IHT that could meet the requirements [of the curriculum standards] since now I can complete the critical first step [of IHT] well…

However, despite the improvement in her confidence in IHT following Stage 1, Shuitao also expressed some concerns. She articulated uncertainty regarding her performance in the subsequent stages of the teacher professional development program. Consequently, her confidence in IHT experienced only a modest increase.

After stage 2: “I participate in the development of IHT cases, and my confidence is increased a little bit more”

Following Stage 2, Shuitao reported further increased confidence in IHT. She attributed this growth to two main factors. Firstly, she successfully developed several instructional designs for IHT through collaboration with in-service teachers. These collaborative experiences enabled her to gain a deeper understanding of IHT approaches and enhance her pedagogical content knowledge in this area, consequently bolstering her confidence in her ability to perform effectively. Secondly, Shuitao observed the tangible impact of IHT cases on students in real classroom settings, which reinforced her belief in the efficacy of IHT. These experiences instilled in her a greater sense of confidence in her capacity to positively influence her students through her implementation of IHT. Shuitao remarked that she gradually understood how to integrate suitable history-related materials into her instructional designs (e.g., employ a genetic approach Footnote 10 ), considering it as the second important step of IHT. She shared her experience of developing IHT instructional design on the concept of logarithms. After creating several iterations of IHT instructional designs, Shuitao emphasized that her confidence in SE-IHT-IP has strengthened. She expressed belief in her ability to apply these approaches to IHT, as well as the pedagogical content knowledge of IHT, acquired through practical experience, in her future teaching endeavors. The following is an excerpt from the interview:

I learned some effective knowledge, skills, techniques and approaches [to IHT]… By employing these approaches, I thought I could [and] I had the confidence to integrate the history into instructional designs very well… For instance, [inspired] by the genetic approach, we designed a series of questions and tasks based on the history of logarithms. The introduction of the new concept of logarithms became very natural, and it perfectly met the requirements of our curriculum standards, [which] asked students to understand the necessity of learning the concept of logarithms…

Shuitao actively observed the classroom teaching conducted by her cooperating in-service teacher. She helped her cooperating in-service teacher in collecting and analyzing students’ feedback. Subsequently, discussions ensued on how to improve the instructional designs based on this feedback. The refined IHT instructional designs were subsequently re-implemented by the in-service teacher. After three rounds of developing IHT cases, Shuitao became increasingly convinced of the significance and efficacy of integrating history into teaching practices, as evidenced by the following excerpt:

The impacts of IHT on students are visible… For instance, more than 93% of the students mentioned in the open-ended questionnaires that they became more interested in mathematics because of the [historical] story of Napier… For another example, according to the results of our surveys, more than 75% of the students stated that they knew log a ( M + N ) = log a M × log a N was wrong because of history… I have a little bit more confidence in the effects of my IHT on students.

This excerpt highlights that Shuitao’s SE-IHT-SO was enhanced. She attributed this enhancement to her realization of the compelling nature of history and her belief in her ability to effectively leverage its power to positively influence her students’ cognitive and emotional development. This also underscores the importance of reinforcing pre-service teachers’ awareness of the significance of history. Nonetheless, Shuiato elucidated that she still retained concerns regarding the effectiveness of her IHT implementation. Her following statement shed light on why her self-efficacy only experienced a marginal increase in this stage:

Knowing how to do it successfully and doing it successfully in practice are two totally different things… I can develop IHT instructional designs well, but I have no idea whether I can implement them well and whether I can introduce the history professionally in practice… My cooperation in-service teacher has a long history of teaching mathematics and gains rich experience in educational practices… If I cannot acquire some required teaching skills and capabilities, I still cannot influence my students powerfully.

After stage 3: “Practice makes perfect, and my SE-IHT-IP is steadily enhanced after a hit”

After successfully developing IHT instructional designs, the next critical step was the implementation of these designs. Drawing from her observations of her cooperating in-service teachers’ IHT implementations and discussions with other pre-service teachers, Shuitao developed her own IHT lesson plans. In Stage 3, she conducted simulated teaching sessions and evaluated her teaching performance ten times Footnote 11 . Shuitao claimed that her SE-IHT-IP steadily improved over the course of these sessions. According to Shuitao, two main processes in Stage 3 facilitated this steady enhancement of SE-IHT-IP.

On the one hand, through the repeated implementation of simulated teaching sessions, Shuitao’s teaching proficiency and fluency markedly improved. Shuitao first described the importance of teaching proficiency and fluency:

Since the detailed history is not included in our curriculum standards and textbooks, if I use my historical materials in class, I have to teach more contents than traditional teachers. Therefore, I have to teach proficiently so that teaching pace becomes a little faster than usual… I have to teach fluently so as to use each minute efficiently in my class. Otherwise, I cannot complete the teaching tasks required [by curriculum standards].

As Shuitao said, at the beginning of Stage 3, her self-efficacy even decreased because she lacked teaching proficiency and fluency and was unable to complete the required teaching tasks:

In the first few times of simulated teaching, I always needed to think for a second about what I should say next when I finish one sentence. I also felt very nervous when I stood in the front of the classrooms. This made my narration of the historical story between Briggs and Napier not fluent at all. I paused many times to look for some hints on my notes… All these made me unable to complete the required teaching tasks… My [teaching] confidence took a hit.

Shuitao quoted the proverb, “practice makes perfect”, and she emphasized that it was repeated practice that improved her teaching proficiency and fluency:

I thought I had no other choice but to practice IHT repeatedly… [At the end of Stage 3,] I could naturally remember most words that I should say when teaching the topics that I selected… My teaching proficiency and fluency was improved through my repeated review of my instructional designs and implementation of IHT in the micro-classrooms… With the improvement [of my teaching proficiency and fluency], I could complete the teaching tasks, and my confidence was increased as well.

In addition, Shuitao also mentioned that through this kind of self-exploration in simulated teaching practice, her teaching skills and capabilities (e.g., blackboard writing, abilities of language organization abilities, etc.) improved. This process was of great help to her enhancement of SE-IHT-IP.

On the other hand, Shuitao’s simulated teaching underwent assessment by herself, with mentors, in-service teachers and fellow pre-service teachers. This comprehensive evaluation process played a pivotal role in enhancing her individual performance and self-efficacy. Reflecting on this aspect, Shuitao articulated the following sentiments in one of her reflection reports:

By watching the videos, conducting self-assessment, and collecting feedback from others, I can understand what I should improve or emphasize in my teaching. [Then,] I think my IHT can better meet the requirements [of curriculum standards]… I think my teaching performance is getting better and better.

After stage 4: “My micro-courses influenced students positively, and my SE-IHT-SO is steadily enhanced”

In Stage 4, Shuitao commenced by creating 5-min micro-course videos. Subsequently, she played these videos in her cooperating in-service teachers’ authentic classroom settings and collected student feedback. This micro-course was played at the end of her cooperating in-service teachers’ lesson Footnote 12 . Shuitao wrote in her reflections that this micro-course of logarithms helped students better understand the nature of mathematics:

According to the results of our surveys, many students stated that they knew the development and evolution of the concept of logarithms is a long process and many mathematicians from different countries have contributed to the development of the concept of logarithms… This indicated that my micro-course helped students better understand the nature of mathematics… My micro-course about the history informed students that mathematics is an evolving and human subject and helped them understand the dynamic development of the [mathematics] concept…

Meanwhile, Shuitao’s micro-course positively influenced some students’ beliefs towards mathematics. As evident from the quote below, integrating historical context into mathematics teaching transformed students’ perception of the subject, boosting Shuitao’s confidence too.

Some students’ responses were very exciting… [O]ne [typical] response stated, he always regarded mathematics as abstract, boring, and dreadful subject; but after seeing the photos of mathematicians and great men and learning the development of the concept of logarithms through the micro-course, he found mathematics could be interesting. He wanted to learn more the interesting history… Students’ such changes made me confident.

Furthermore, during post-class interviews, several students expressed their recognition of the significance of the logarithms concept to Shuitao, attributing this realization to the insights provided by prominent figures in the micro-courses. They also conveyed their intention to exert greater effort in mastering the subject matter. This feedback made Shuitao believe that her IHT had the potential to positively influence students’ attitudes towards learning mathematics.

In summary, Stage 4 marked Shuitao’s first opportunity to directly impact students through her IHT in authentic classroom settings. Despite implementing only brief 5-min micro-courses integrating history during each session, the effectiveness of her short IHT implementation was validated by student feedback. Shuitao unequivocally expressed that students actively engaged with her micro-courses and that these sessions positively influenced them, including attitudes and motivation toward mathematics learning, understanding of mathematics concepts, and beliefs regarding mathematics. These collective factors contributed to a steady enhancement of her confidence in SE-IHT-SO.

After stage 5: “My overall self-efficacy is greatly enhanced”

Following Stage 5, Shuitao reported a significant increase in her overall confidence in IHT, attributing it to gaining mastery through successful implementations of IHT in real classroom settings. On the one hand, Shuitao successfully designed and executed her IHT lesson plans, consistently achieving the teaching objectives mandated by curriculum standards. This significantly enhanced her SE-IHT-IP. On the other hand, as Shuitao’s IHT implementation directly influenced her students, her confidence in SE-IHT-SO experienced considerable improvement.

According to Bandura ( 1997 ), mastery experience is the most powerful source of self-efficacy. Shuitao’s statements confirmed this. As she claimed, her enhanced SE-IHT-IP in Stage 5 mainly came from the experience of successful implementations of IHT in real classrooms:

[Before the teacher professional development program,] I had no idea about implementing IHT… Now, I successfully implemented IHT in senior high school [classrooms] many times… I can complete the teaching tasks and even better completed the teaching objectives required [by the curriculum standards]… The successful experience greatly enhances my confidence to perform well in my future implementation of IHT… Yeah, I think the successful teaching practice experience is the strongest booster of my confidence.

At the end of stage 5, Shuitao’s mentors and in-service teachers gave her a high evaluation. For instance, after Shuitao’s IHT implementation of the concept of logarithms, all mentors and in-service teachers consistently provided feedback that her IHT teaching illustrated the necessity of learning the concept of logarithms and met the requirements of the curriculum standards very well. This kind of verbal persuasion (Bandura 1997 ) enhanced her SE-IHT-IP.

Similarly, Shuitao’s successful experience of influencing students positively through IHT, as one kind of mastery experience, powerfully enhanced her SE-IHT-SO. She described her changes in SE-IHT-SO as follows:

I could not imagine my IHT could be so influential [before]… But now, my IHT implementation directly influenced students in so many aspects… When I witnessed students’ real changes in various cognitive and affective aspects, my confidence was greatly improved.

Shuitao described the influence of her IHT implementation of the concept of logarithms on her students. The depiction is grounded in the outcomes of surveys conducted by Shuitao following her implementation. Shuitao asserted that these results filled her with excitement and confidence regarding her future implementation of IHT.

In summary, following Stage 5 of the teacher professional development program, Shuitao experienced a notable enhancement in her overall self-efficacy, primarily attributed to her successful practical experience in authentic classroom settings during this stage.

A primary objective of our teacher professional development programs is to equip pre-service teachers with the skills and confidence needed to effectively implement IAT. Our findings show that one teacher professional development program, significantly augmented a participant’s TSE-IHT across two dimensions: individual performance and student outcomes. Considering the pressing need to provide STEAM teachers with effective professional training (e.g., Boice et al. 2021 ; Duong et al. 2024 ; Herro et al. 2019 ; Jacques et al. 2020 ; Park and Cho 2022 ; Perignat and Katz-Buonincontro 2019 ), the proposed five-stage framework holds significant promise in both theoretical and practical realms. Furthermore, this study offers a viable solution to address the prevalent issue of low levels of teacher self-efficacy in interdisciplinary teaching, including IAT, which is critical in STEAM education (Zhou et al. 2023 ). This study holds the potential to make unique contributions to the existing body of literature on teacher self-efficacy, teacher professional learning models and the design of teacher professional development programs of IAT.

Firstly, this study enhances our understanding of the development of teacher self-efficacy. Our findings further confirm the complexity of the development of teacher self-efficacy. On the one hand, the observed enhancement of the participant’s teacher self-efficacy did not occur swiftly but unfolded gradually through a protracted, incremental process. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the participant’s self-efficacy exhibited fluctuations, underscoring that the augmentation of teacher self-efficacy is neither straightforward nor linear. On the other hand, the study elucidated that the augmentation of teacher self-efficacy constitutes an intricate, multi-level system that interacts with teacher knowledge, skills, and other beliefs. This finding resonates with prior research on teacher self-efficacy (Morris et al. 2017 ; Xenofontos and Andrews 2020 ). For example, our study revealed that Shuitao’s enhancement of SE-IHT-SO may always be interwoven with her continuous comprehension of the significance of the A&H in classroom settings. Similarly, the participant progressively acknowledged the educational value of A&H in classroom contexts in tandem with the stepwise enhancement of SE-IHT-SO. Factors such as the participant’s pedagogical content knowledge of IHT, instructional design, and teaching skills were also identified as pivotal components of SE-IHT-IP. This finding corroborates Morris and Usher ( 2011 ) assertion that sustained improvements in self-efficacy stem from developing teachers’ skills and knowledge. With the bolstering of SE-IHT-IP, the participant’s related teaching skills and content knowledge also exhibited improvement.

Methodologically, many researchers advocate for qualitative investigations into self-efficacy (e.g., Philippou and Pantziara 2015; Klassen et al. 2011 ; Wyatt 2015 ; Xenofontos and Andrews 2020 ). While acknowledging limitations in sample scope and the generalizability of the findings, this study offers a longitudinal perspective on the stage-by-stage development of teacher self-efficacy and its interactions with different factors (i.e., teacher knowledge, skills, and beliefs), often ignored by quantitative studies. Considering that studies of self-efficacy have been predominantly quantitative, typically drawing on survey techniques and pre-determined scales (Xenofontos and Andrews, 2020 ; Zhou et al. 2023 ), this study highlights the need for greater attention to qualitative studies so that more cultural, situational and contextual factors in the development of self-efficacy can be captured.

Our study provides valuable practical implications for enhancing pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy. We conceptualize teacher self-efficacy in two primary dimensions: individual performance and student outcomes. On the one hand, pre-service teachers can enhance their teaching qualities, boosting their self-efficacy in individual performance. The adage “practice makes perfect” underscores the necessity of ample teaching practice opportunities for pre-service teachers who lack prior teaching experience. Engaging in consistent and reflective practice helps them develop confidence in their teaching qualities. On the other hand, pre-service teachers should focus on positive feedback from their students, reinforcing their self-efficacy in individual performance. Positive student feedback serves as an affirmation of their teaching effectiveness and encourages continuous improvement. Furthermore, our findings highlight the significance of mentors’ and peers’ positive feedback as critical sources of teacher self-efficacy. Mentors and peers play a pivotal role in the professional growth of pre-service teachers by actively encouraging them and recognizing their teaching achievements. Constructive feedback from experienced mentors and supportive peers fosters a collaborative learning environment and bolsters the self-confidence of pre-service teachers. Additionally, our research indicates that pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy may fluctuate. Therefore, mentors should be prepared to help pre-service teachers manage teaching challenges and setbacks, and alleviate any teaching-related anxiety. Mentors can help pre-service teachers build resilience and maintain a positive outlook on their teaching journey through emotional support and guidance. Moreover, a strong correlation exists between teacher self-efficacy and teacher knowledge and skills. Enhancing pre-service teachers’ knowledge base and instructional skills is crucial for bolstering their overall self-efficacy.

Secondly, this study also responds to the appeal to understand teachers’ professional learning from a holistic perspective and interrelate teachers’ professional learning process with student outcome variables (Sancar et al. 2021 ), and thus contributes to the understanding of the complexity of STEAM teachers’ professional learning. On the one hand, we have confirmed Cai et al.’s ( 2020 ) teacher professional learning model in a new context, namely STEAM teacher education. Throughout the teacher professional development program, the pre-service teacher, Shuitao, demonstrated an augmentation in her knowledge, encompassing both content knowledge and pedagogical understanding concerning IHT. Moreover, her beliefs regarding IHT transformed as a result of her engagement in teacher learning across the five stages. This facilitated her in executing effective IHT teaching and improving her students’ outcomes. On the other hand, notably, in our studies (including this current study and some follow-up studies), student feedback is a pivotal tool to assist teachers in discerning the impact they are effectuating. This enables pre-service teachers to grasp the actual efficacy of their teaching efforts and subsequently contributes significantly to the augmentation of their self-efficacy. Such steps have seldom been conducted in prior studies (e.g., Cai et al. 2020 ), where student outcomes are often perceived solely as the results of teachers’ instruction rather than sources informing teacher beliefs. Additionally, this study has validated both the interaction between teaching performance and teacher beliefs and between teacher knowledge and teacher beliefs. These aspects were overlooked in Cai et al.’s ( 2020 ) model. More importantly, while Clarke and Hollingsworth’s ( 2002 ) Interconnected Model of Professional Growth illustrates the connections between the domain of consequence and the personal domain, as well as between the personal domain and the domain of practice, it does not adequately clarify the complex relationships among the factors within the personal domain (e.g., the interaction between teacher knowledge and teacher beliefs). Therefore, our study also supplements Clarke and Hollingsworth’s ( 2002 ) model by addressing these intricacies. Based on our findings, an updated model of teacher professional learning has been proposed, as shown in Fig. 3 . This expanded model indicates that teacher learning should be an ongoing and sustainable process, with the enhancement of student learning not marking the conclusion of teacher learning, but rather serving as the catalyst for a new phase of learning. In this sense, we advocate for further research to investigate the tangible impacts of teacher professional development programs on students and how those impacts stimulate subsequent cycles of teacher learning.

Note: Paths in blue were proposed by Cai et al. ( 2020 ), and paths in yellow are proposed and verified in this study.

Thirdly, in light of the updated model of teacher professional learning (see Fig. 3 ), this study provides insights into the design of teacher professional development programs of IAT. According to Huang et al. ( 2022 ), to date, very few studies have set goals to “develop a comprehensive understanding of effective designs” for STEM (or STEAM) teacher professional development programs (p. 15). To fill this gap, this study proposes a novel and effective five-stage framework for teacher professional development programs of IAT. This framework provides a possible and feasible solution to the challenges of STEAM teacher professional development programs’ design and planning, and teachers’ IAT practice (Boice et al. 2021 ; Herro et al. 2019 ; Jacques et al. 2020 ; Park and Cho 2022 ; Perignat and Katz-Buonincontro 2019 ).

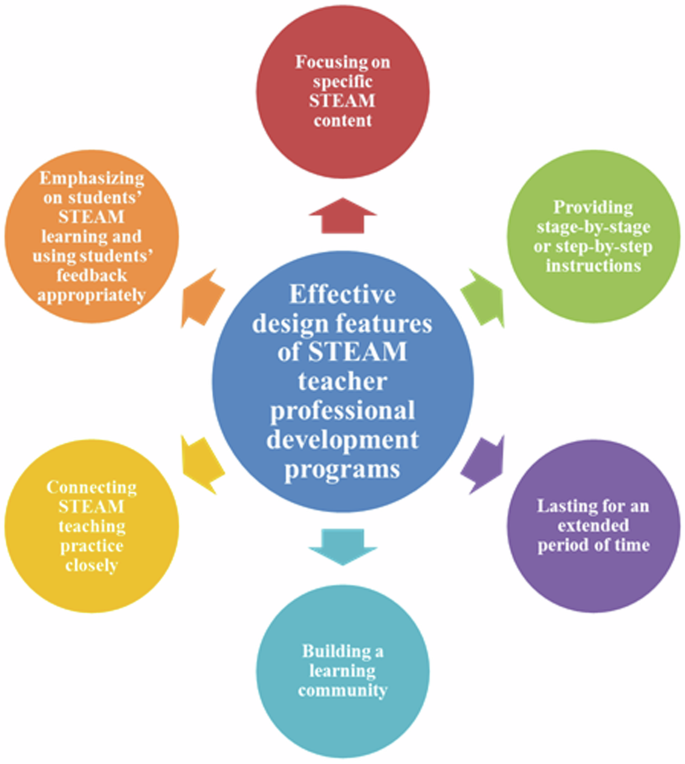

Specifically, our five-stage framework incorporates at least six important features. Firstly, teacher professional development programs should focus on specific STEAM content. Given the expansive nature of STEAM, teacher professional development programs cannot feasibly encompass all facets of its contents. Consistent with recommendations by Cai et al. ( 2020 ), Desimone et al. ( 2002 ) and Garet et al. ( 2001 ), an effective teacher professional development program should prioritize content focus. Our five-stage framework is centered on IAT. Throughout an 18-month duration, each pre-service teacher is limited to selecting one subcomponent of A&H, such as history, for integration into their subject teaching (i.e., mathematics teaching, technology teaching or science teaching) within one teacher professional development program. Secondly, in response to the appeals that teacher professional development programs should shift from emphasizing teaching and instruction to emphasizing student learning (Cai et al. 2020 ; Calabrese et al. 2024 ; Hwang et al. 2024 ; Marco and Palatnik 2024 ; Örnek and Soylu 2021 ), our framework requires pre-service teachers to pay close attention to the effects of IAT on student learning outcomes, and use students’ feedback as the basis of improving their instruction. Thirdly, prior studies found that teacher education with a preference for theory led to pre-service teachers’ dissatisfaction with the quality of teacher professional development program and hindered the development of pre-service teachers’ teaching skills and teaching beliefs, which also widened the gap between theory and practice (Hennissen et al. 2017 ; Ord and Nuttall 2016 ). In this regard, our five-stage framework connects theory and teaching practice closely. In particular, pre-service teachers can experience the values of IAT not only through theoretical learning but also through diverse teaching practices. Fourthly, we build a teacher community of practice tailored for pre-service teachers. Additionally, we aim to encourage greater participation of in-service teachers in such teacher professional development programs designed for pre-service educators in STEAM teacher education. By engaging in such programs, in-service teachers can offer valuable teaching opportunities for pre-service educators and contribute their insights and experiences from teaching practice. Importantly, pre-service teachers stand to gain from the in-service teachers’ familiarity with textbooks, subject matter expertise, and better understanding of student dynamics. Fifthly, our five-stage framework lasts for an extended period, spanning 18 months. This duration ensures that pre-service teachers engage in a sustained and comprehensive learning journey. Lastly, our framework facilitates a practical understanding of “integration” by offering detailed, sequential instructions for blending two disciplines in teaching. For example, our teacher professional development programs prioritize systematic learning of pedagogical theories and simulated teaching experiences before pre-service teachers embark on real STEAM teaching endeavors. This approach is designed to mitigate the risk of unsuccessful experiences during initial teaching efforts, thereby safeguarding pre-service teachers’ teacher self-efficacy. Considering the complexity of “integration” in interdisciplinary teaching practices, including IAT (Han et al. 2022 ; Ryu et al. 2019 ), we believe detailed stage-by-stage and step-by-step instructions are crucial components of relevant pre-service teacher professional development programs. Notably, this aspect, emphasizing structural instructional guidance, has not been explicitly addressed in prior research (e.g., Cai et al. 2020 ). Figure 4 illustrates the six important features outlined in this study, encompassing both established elements and the novel addition proposed herein, describing an effective teacher professional development program.

Note: STEAM refers to science, technology, engineering, arts and humanities, and mathematics.

The successful implementation of this framework is also related to the Chinese teacher education system and cultural background. For instance, the Chinese government has promoted many university-school collaboration initiatives, encouraging in-service teachers to provide guidance and practical opportunities for pre-service teachers (Lu et al. 2019 ). Influenced by Confucian values emphasizing altruism, many experienced in-service teachers in China are eager to assist pre-service teachers, helping them better realize their teaching career aspirations. It is reported that experienced in-service teachers in China show significantly higher motivation than their international peers when mentoring pre-service teachers (Lu et al. 2019 ). Therefore, for the successful implementation of this framework in other countries, it is crucial for universities to forge close collaborative relationships with K-12 schools and actively involve K-12 teachers in pre-service teacher education.

Notably, approximately 5% of our participants dropped out midway as they found that the IAT practice was too challenging or felt overwhelmed by the number of required tasks in the program. Consequently, we are exploring options to potentially simplify this framework in future iterations.

Without minimizing the limitations of this study, it is important to recognize that a qualitative longitudinal case study can be a useful means of shedding light on the development of a pre-service STEAM teacher’s self-efficacy. However, this methodology did not allow for a pre-post or a quasi-experimental design, and the effectiveness of our five-stage framework could not be confirmed quantitatively. In the future, conducting more experimental or design-based studies could further validate the effectiveness of our framework and broaden our findings. Furthermore, future studies should incorporate triangulation methods and utilize multiple data sources to enhance the reliability and validity of the findings. Meanwhile, owing to space limitations, we could only report the changes in Shuitao’s SE-IHT-IP and SE-IHT-SO here, and we could not describe the teacher self-efficacy of other participants regarding IAT. While nearly all of the pre-service teachers experienced an improvement in their teacher self-efficacy concerning IAT upon participating in our teacher professional development programs, the processes of their change were not entirely uniform. We will need to report the specific findings of these variations in the future. Further studies are also needed to explore the factors contributing to these variations. Moreover, following this study, we are implementing more teacher professional development programs of IAT. Future studies can explore the impact of this framework on additional aspects of pre-service STEAM teachers’ professional development. This will help gain a more comprehensive understanding of its effectiveness and potential areas for further improvement. Additionally, our five-stage framework was initially developed and implemented within the Chinese teacher education system. Future research should investigate how this framework can be adapted in other educational systems and cultural contexts.

The impetus behind this study stems from the burgeoning discourse advocating for the integration of A&H disciplines into STEM education on a global scale (e.g., Land 2020 ; Park and Cho 2022 ; Uştu et al. 2021 ; Vaziri and Bradburn 2021 ). Concurrently, there exists a pervasive concern regarding the challenges teachers face in implementing STEAM approaches, particularly in the context of IAT practices (e.g., Boice et al. 2021 ; Herro et al. 2019 ; Jacques et al. 2020 ; Park and Cho 2022 ; Perignat and Katz-Buonincontro 2019 ). To tackle this challenge, we first proposed a five-stage framework designed for teacher professional development programs of IAT. Then, utilizing this innovative framework, we implemented a series of teacher professional development programs. Drawing from the recommendations of Bray-Clark and Bates ( 2003 ), Kelley et al. ( 2020 ) and Zhou et al. ( 2023 ), we have selected teacher self-efficacy as a key metric to examine the effectiveness of the five-stage framework. Through a qualitative longitudinal case study, we scrutinized the influence of a specific teacher professional development program on the self-efficacy of a single pre-service teacher over an 18-month period. Our findings revealed a notable enhancement in teacher self-efficacy across both individual performance and student outcomes. The observed enhancement of the participant’s teacher self-efficacy did not occur swiftly but unfolded gradually through a prolonged, incremental process. Building on our findings, an updated model of teacher learning has been proposed. The updated model illustrates that teacher learning should be viewed as a continuous and sustainable process, wherein teaching performance, teacher beliefs, and teacher knowledge dynamically interact with one another. The updated model also confirms that teacher learning is inherently intertwined with student learning in STEAM education. Furthermore, this study also summarizes effective design features of STEAM teacher professional development programs.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are not publicly available due to general data protection regulations, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

In their review article, Morris et al. ( 2017 ) equated “teaching self-efficacy” and “teacher self-efficacy” as synonymous concepts. This perspective is also adopted in this study.

An effective teacher professional development program should have specific, focused, and clear content instead of broad and scattered ones. Therefore, each pre-service teacher can only choose to integrate one subcomponent of A&H into their teaching in one teacher professional development program. For instance, Shuitao, a mathematics pre-service teacher, participated in one teacher professional development program focused on integrating history into mathematics teaching. However, she did not explore the integration of other subcomponents of A&H into her teaching during her graduate studies.

In the micro-classrooms, multi-angle, and multi-point high-definition video recorders are set up to record the teaching process.

In micro-teaching, mentors, in-service teachers, and other fellow pre-service teachers take on the roles of students.

In China, teachers can video record one section of a lesson and play them in formal classes. This is a practice known as a micro-course. For instance, in one teacher professional development program of integrating history into mathematics teaching, micro-courses encompass various mathematics concepts, methods, ideas, history-related material and related topics. Typically, teachers use these micro-courses to broaden students’ views, foster inquiry-based learning, and cultivate critical thinking skills. Such initiatives play an important role in improving teaching quality.

Many university-school collaboration initiatives in China focus on pre-service teachers’ practicum experiences (Lu et al. 2019 ). Our teacher professional development program is also supported by many K-12 schools in Shanghai. Personal information in videos is strictly protected.