How to Write a Case Study: A Breakdown of Requirements

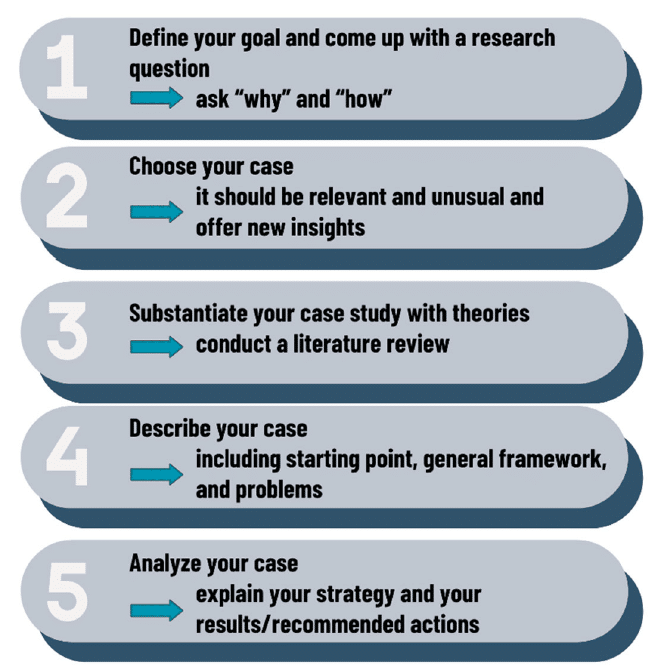

It can take months to develop a case study. First, a topic must be chosen. Then the researcher must state his hypothesis, and make certain it lines up with the chosen topic. Then all the research must be completed. The case study can require both quantitative and qualitative research, as well as interviews with subjects. Once that is all done, it is time to write the case study.

Not all case studies are written the same. Depending on the size and topic of the study, it could be hundreds of pages long. Regardless of the size, the case study should have four main sections. These sections are:

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Presentation of Findings

4. Conclusion

The Introduction

The introduction should set the stage for the case study, and state the thesis for the report. The intro must clearly articulate what the study's intention is, as well as how you plan on explaining and answering the thesis.

Again, remember that a case study is not a formal scientific research report that will only be read by scientists. The case study must be able to be read and understood by the layperson, and should read almost as a story, with a clear narrative.

As the reader reads the introduction, they should fully understand what the study is about, and why it is important. They should have a strong foundation for the background they will learn about in the next section.

The introduction should not be long. You must be able to introduce your topic in one or two paragraphs. Ideally, the introduction is one paragraph of about 3-5 sentences.

The Background

The background should detail what information brought the researcher to pose his hypothesis. It should clearly explain the subject or subjects, as well as their background information. And lastly, the background must give the reader a full understanding of the issue at hand, and what process will be taken with the study. Photos and videos are always helpful when applicable.

When writing the background, the researcher must explain the research methods used, and why. The type of research used will be dependent on the type of case study. The reader should have a clear idea why a particular type of research is good for the field and type of case study.

For example, a case study that is trying to determine what causes PTSD in veterans will heavily use interviews as a research method. Directly interviewing subjects garners invaluable research for the researcher. If possible, reference studies that prove this.

Again, as with the introduction, you do not want to write an extremely long background. It is important you provide the right amount of information, as you do not want to bore your readers with too much information, and you don't want them under-informed.

How much background information should a case study provide? What would happen if the case study had too much background info?

What would happen if the case study had too little background info?

The Presentation of Findings

While a case study might use scientific facts and information, a case study should not read as a scientific research journal or report. It should be easy to read and understand, and should follow the narrative determined in the first step.

The presentation of findings should clearly explain how the topic was researched, and summarize what the results are. Data should be summarized as simply as possible so that it is understandable by people without a scientific background. The researcher should describe what was learned from the interviews, and how the results answered the questions asked in the introduction.

When writing up the report, it is important to set the scene. The writer must clearly lay out all relevant facts and detail the most important points. While this section may be lengthy, you do not want to overwhelm the reader with too much information.

The Conclusion

The final section of the study is the conclusion. The purpose of the study isn't necessarily to solve the problem, only to offer possible solutions. The final summary should be an end to the story.

Remember, the case study is about asking and answering questions. The conclusion should answer the question posed by the researcher, but also leave the reader with questions of his own. The researcher wants the reader to think about the questions posed in the study, and be free to come to their own conclusions as well.

When reading the conclusion, the reader should be able to have the following takeaways:

Was there a solution provided? If so, why was it chosen?

Was the solution supported with solid evidence?

Did the personal experiences and interviews support the solution?

The conclusion should also make any recommendations that are necessary. What needs to be done, and you exactly should do it? In the case of the vets with PTSD, once a cause is determined, who is responsible for making sure the needs of the veterans are met?

English Writing Standards For Case Studies

When writing the case study, it is important to follow standard academic and scientific rules when it comes to spelling and grammar.

Spelling and Grammar

It should go without saying that a thorough spell check should be done. Remember, many case studies will require words or terms that are not in standard online dictionaries, so it is imperative the correct spelling is used. If possible, the first draft of the case study should be reviewed and edited by someone other than yourself.

Case studies are normally written in the past tense, as the report is detailing an event or topic that has since passed. The report should be written using a very logical and clear tone. All case studies are scientific in nature and should be written as such.

The First Draft

You do not sit down and write the case study in one day. It is a long and detailed process, and it must be done carefully and with precision. When you sit down to first start writing, you will want to write in plain English, and detail the what, when and how.

When writing the first draft, note any relevant assumptions. Don't immediately jump to any conclusions; just take notes of any initial thoughts. You are not looking for solutions yet. In the first draft use direct quotes when needed, and be sure to identify and qualify all information used.

If there are any issues you do not understand, the first draft is where it should be identified. Make a note so you return to review later. Using a spreadsheet program like Excel or Google Sheets is very valuable during this stage of the writing process, and can help keep you and your information and data organized.

The Second Draft

To prepare the second draft, you will want to assemble everything you have written thus far. You want to reduce the amount of writing so that the writing is tightly written and cogent. Remember, you want your case study to be interesting to read.

When possible, you should consider adding images, tables, maps, or diagrams to the text to make it more interesting for the reader. If you use any of these, make sure you have permission to use them. You cannot take an image from the Internet and use it without permission.

Once you have completed the second draft, you are not finished! It is imperative you have someone review your work. This could be a coworker, friend, or trusted colleague. You want someone who will give you an honest review of your work, and is willing to give you feedback, whether positive or negative.

Remember, you cannot proofread enough! You do not want to risk all of your hard work and research, and end up with a final case study that has spelling or grammatical errors. One typo could greatly hurt your project and damage your reputation in your field.

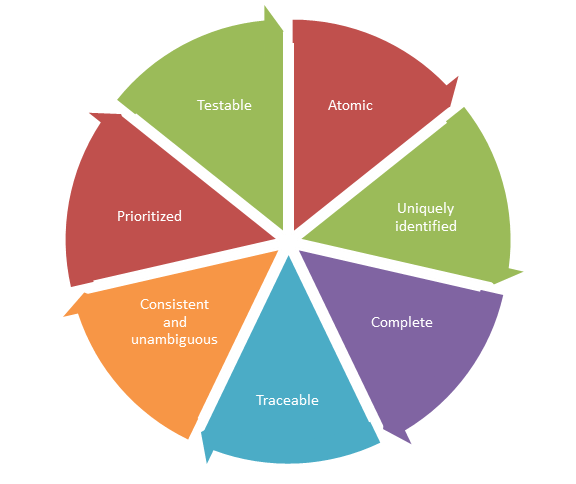

All case studies should follow LIT – Logical – Inclusive – Thorough.

The case study obviously must be logical. There can be no guessing or estimating. This means that the report must state what was observed, but cannot include any opinion or assumptions that might come from such an observation.

For example, if a veteran subject arrives at an interview holding an empty liquor bottle and is slurring his words, that observation must be made. However, the researcher cannot make the inference that the subject was intoxicated. The report can only include the facts.

With the Genie case, researchers witnessed Genie hitting herself and practicing self-harm. It could be assumed that she did this when she was angry. However, this wasn't always the case. She would also hit herself when she was afraid, bored or apprehensive. It is essential that researchers not guess or infer.

In order for a report to be inclusive, it must contain ALL data and findings. The researcher cannot pick and choose which data or findings to use in the report.

Using the example above, if a veteran subject arrives for an interview holding an empty liquor bottle and is slurring his words; any and all additional information that can be garnered should be recorded. For instance, what the subject was wearing, what was his demeanor, was he able to speak and communicate, etc.

When observing a man who might be drunk, it can be easy to make assumptions. However, the researcher cannot allow personal biases or beliefs to sway the findings. Any and all relevant facts must be included, regardless of size or perceived importance. Remember, small details might not seem relevant at the time of the interview. But once it is time to catalog the findings, small details might become important.

The last tip is to be thorough. It is important to delve into every observation. The researcher shouldn't just write down what they see and move on. It is essential to detail as much as possible.

For example, when interviewing veteran subjects, there interview responses are not the only information that should be garnered from the interview. The interviewer should use all senses when detailing their subject.

How does the subject appear? Is he clean? How is he dressed?

How does his voice sound? Is he speaking clearly and making cohesive thoughts? Does his voice sound raspy? Does he speak with a whisper, or does he speak too loudly?

Does the subject smell? Is he wearing cologne, or can you smell that he hasn't bathed or washed his clothes? What do his clothes look like? Is he well dressed, or does he wear casual clothes?

What is the background of the subject? What are his current living arrangements? Does he have supportive family and friends? Is he a loner who doesn't have a solid support system? Is the subject working? If so, is he happy with the job? If he is not employed, why is that? What makes the subject unemployable?

Case Studies in Marketing

We have already determined that case studies are very valuable in the business world. This is particularly true in the marketing field, which includes advertising and public relations. While case studies are almost all the same, marketing case studies are usually more dependent on interviews and observations.

Well-Known Marketing Case Studies

DeBeers is a diamond company headquartered in Luxembourg, and based in South Africa. It is well known for its logo, "A diamond is forever", which has been voted the best advertising slogan of the 20 th century.

Many studies have been done about DeBeers, but none are as well known as their marketing case study, and how they positioned themselves to be the most successful and well-known diamond company in the world.

DeBeers developed the idea for a diamond engagement ring. They also invented the "eternity band", which is a ring that has diamonds going all around it, signifying that long is forever.

They also invented the three-stone ring, signifying the past, present and future. De Beers was the first company to attribute their products, diamonds to the idea of love and romance. They originated the idea that an engagement ring should cost two-months salary.

The two-month salary standard is particularly unique, in that it is totally subjective. A ring should mean the same whether the man makes $25,000 a year or $250,000. And yet, the standard sticks due to DeBeers incredible marketing skills.

The De Beers case study is one of the most famous studies when it comes to both advertising and marketing, and is used worldwide as the ultimate example of a successful ongoing marketing campaign.

Planning the Market Research

The most important parts of the marketing case study are:

1. The case study's questions

2. The study's propositions

3. How information and data will be analyzed

4. The logic behind what is being proposed

5. How the findings will be interpreted

The study's questions should be either "how" or "why" questions, and their definitions are the researchers first job. These questions will help determine the study's goals.

Not every case study has a proposition. If you are doing an exploratory study, you will not have propositions. Instead, you will have a stated purpose, which will determine whether your study is successful, or not.

How the information will be analyzed will depend on what the topic is. This would vary depending on whether it was a person, group, or organization. Event and place studies are done differently.

When setting up your research, you will want to follow case study protocol. The protocol should have the following sections:

1. An overview of the case study, including the objectives, topic and issues.

2. Procedures for gathering information and conducting interviews.

3. Questions that will be asked during interviews and data collection.

4. A guide for the final case study report.

When deciding upon which research methods to use, these are the most important:

1. Documents and archival records

2 . Interviews

3. Direct observations (and indirect when possible)

4. Indirect observations, or observations of subjects

5. Physical artifacts and tools

Documents could include almost anything, including letters, memos, newspaper articles, Internet articles, other case studies, or any other document germane to the study.

Developing the Case Study

Developing a marketing case study follows the same steps and procedures as most case studies. It begins with asking a question, "what is missing?"

1. What is the background of the case study? Who requested the study to be done and why? What industry is the study in, and where will the study take place? What marketing needs are you trying to address?

2. What is the problem that needs a solution? What is the situation, and what are the risks? What are you trying to prove?

3. What questions are required to analyze the problem? What questions might the reader of the study have?

4. What tools are required to analyze the problem? Is data analysis necessary? Can the study use just interviews and observations, or will it require additional information?

5. What is your current knowledge about the problem or situation? How much background information do you need to procure? How will you obtain this background info?

6. What other information do you need to know to successfully complete the study?

7. How do you plan to present the report? Will it be a simple written report, or will you add PowerPoint presentations or images or videos? When is the report due? Are you giving yourself enough time to complete the project?

Formulating the Marketing Case Study

1. What is the marketing problem? Most case studies begin with a problem that management or the marketing department is facing. You must fully understand the problem and what caused it. That is when you can start searching for a solution.

However, marketing case studies can be difficult to research. You must turn a marketing problem into a research problem. For example, if the problem is that sales are not growing, you must translate that to a research problem.

What could potential research problems be?

Research problems could be poor performance or poor expectations. You want a research problem because then you can find an answer. Management problems focus on actions, such as whether to advertise more, or change advertising strategies. Research problems focus on finding out how to solve the management problem.

Method of Inquiry

As with the research for most case studies, the scientific method is standard. It allows you to use existing knowledge as a starting point. The scientific method has the following steps:

1. Ask a question – formulate a problem

2. Do background research

3. Formulate a problem

4. Develop/construct a hypothesis

5. Make predictions based on the hypothesis

6. Do experiments to test the hypothesis

7 . Conduct the test/experiment

8 . Analyze and communicate the results

The above terminology is very similar to the research process. The main difference is that the scientific method is objective and the research process is subjective. Quantitative research is based on impartial analysis, and qualitative research is based on personal judgment.

Research Method

After selecting the method of inquiry, it is time to decide on a research method. There are two main research methodologies, experimental research and non-experimental research.

Experimental research allows you to control the variables and to manipulate any of the variables that influence the study.

Non-experimental research allows you to observe, but not intervene. You just observe and then report your findings.

Research Design

The design is the plan for how you will conduct the study, and how you will collect the data. The design is the scientific method you will use to obtain the information you are seeking.

Data Collection

There are many different ways to collect data, with the two most important being interviews and observation.

Interviews are when you ask people questions and get a response. These interviews can be done face-to-face, by telephone, the mail, email, or even the Internet. This category of research techniques is survey research. Interviews can be done in both experimental and non-experimental research.

Observation is watching a person or company's behavior. For example, by observing a persons buying behavior, you could predict how that person will make purchases in the future.

When using interviews or observation, it is required that you record your results. How you record the data will depend on which method you use. As with all case studies, using a research notebook is key, and will be the heart of the study.

Sample Design

When developing your case study, you won't usually examine an entire population; those are done by larger research projects. Your study will use a sample, which is a small representation of the population. When designing your sample, be prepared to answer the following questions:

1. From which type of population should the sample be chosen?

2. What is the process for the selection of the sample?

3. What will be the size of the sample?

There are two ways to select a sample from the general population; probability and non-probability sampling. Probability sampling uses random sampling of everyone in the population. Non-probability sampling uses the judgment of the researcher.

The last step of designing your sample is to determine the sample size. This can depend on cost and accuracy. Larger samples are better and more accurate, but they can also be costly.

Analysis of the Data

In order to use the data, it first must be analyzed. How you analyze the data should be decided upon as early in the process as possible, and will vary depending on the type of info you are collecting, and the form of measurement being used. As stated repeatedly, make sure you keep track of everything in the research notebook.

The Marketing Case Study Report

The final stage of the process is the marketing case study. The final study will include all of the information, as well as detail the process. It will also describe the results, conclusions, and any recommendations. It must have all the information needed so that the reader can understand the case study.

As with all case studies, it must be easy to read. You don't want to use info that is too technical; otherwise you could potentially overwhelm your reader. So make sure it is written in plain English, with scientific and technical terms kept to a minimum.

Using Your Case Study

Once you have your finished case study, you have many opportunities to get that case study in front of potential customers. Here is a list of the ways you can use your case study to help your company's marketing efforts.

1. Have a page on your website that is dedicated to case studies. The page should have a catchy name and list all of the company's case studies, beginning with the most recent. Next to each case study list its goals and results.

2. Put the case study on your home page. This will put your study front and center, and will be immediately visible when customers visit your web page. Make sure the link isn't hidden in an area rarely visited by guests. You can highlight the case study for a few weeks or months, or until you feel your study has received enough looks.

3. Write a blog post about your case study. Obviously you must have a blog for this to be successful. This is a great way to give your case study exposure, and it allows you to write the post directly addressing your audience's needs.

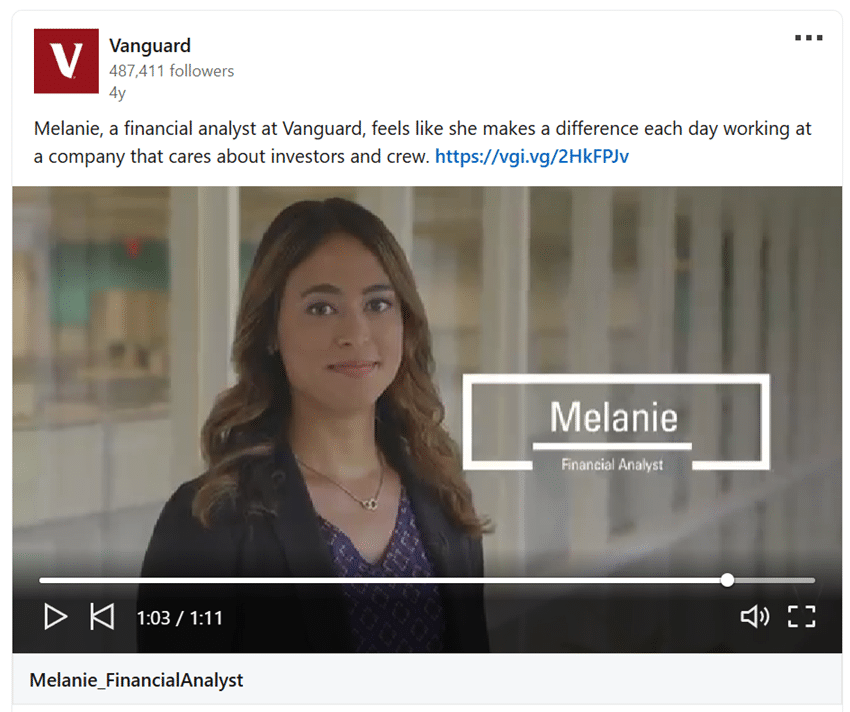

4 . Make a video from your case study. Videos are more popular than ever, and turning a lengthy case study into a brief video is a great way to get your case study in front of people who might not normally read a case study.

5. Use your case study on a landing page. You can pull quotes from the case study and use those on product pages. Again, this format works best when you use market segmentation.

6. Post about your case studies on social media. You can share links on Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn. Write a little interesting tidbit, enough to capture your client's interest, and then place the link.

7 . Use your case study in your email marketing. This is most effective if your email list is segmented, and you can direct your case study to those most likely to be receptive to it.

8. Use your case studies in your newsletters. This can be especially effective if you use segmentation with your newsletters, so you can gear the case study to those most likely to read and value it.

- Course Catalog

- Group Discounts

- Gift Certificates

- For Libraries

- CEU Verification

- Medical Terminology

- Accounting Course

- Writing Basics

- QuickBooks Training

- Proofreading Class

- Sensitivity Training

- Excel Certificate

- Teach Online

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

- All Categories

- Marketing Analytics Software

What Is a Case Study? How to Write, Examples, and Template

In this post

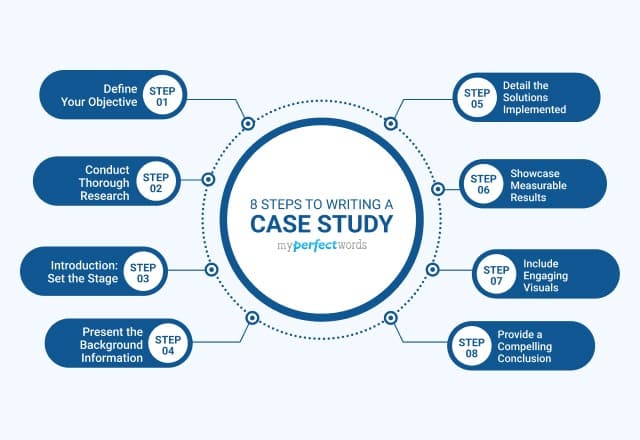

How to write a case study

Case study template, case study examples, types of case studies, what are the benefits of case studies , what are the limitations of case studies , case study vs. testimonial.

In today's marketplace, conveying your product's value through a compelling narrative is crucial to genuinely connecting with your customers.

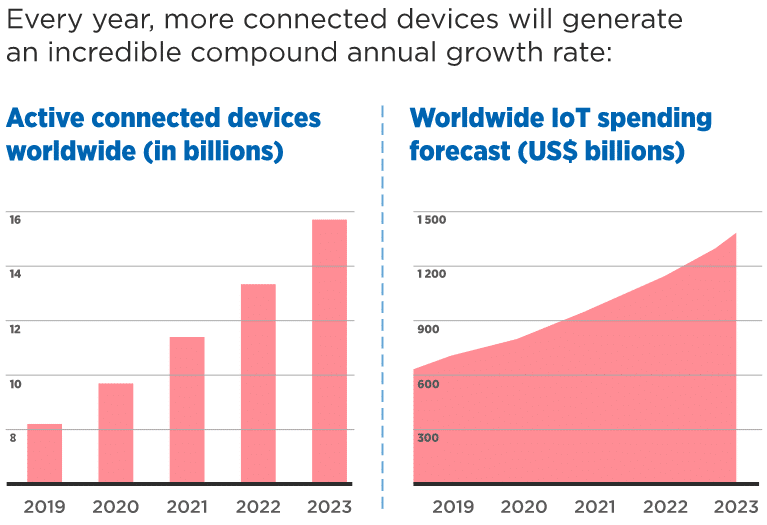

Your business can use marketing analytics tools to understand what customers want to know about your product. Once you have this information, the next step is to showcase your product and its benefits to your target audience. This strategy involves a mix of data, analysis, and storytelling. Combining these elements allows you to create a narrative that engages your audience. So, how can you do this effectively?

What is a case study?

A case study is a powerful tool for showcasing a business's success in helping clients achieve their goals. It's a form of storytelling that details real-world scenarios where a business implemented its solutions to deliver positive results for a client.

In this article, we explore the concept of a case study , including its writing process, benefits, various types, challenges, and more.

Understanding how to write a case study is an invaluable skill. You'll need to embrace decision-making – from deciding which customers to feature to designing the best format to make them as engaging as possible. This can feel overwhelming in a hurry, so let's break it down.

Step 1: Reach out to the target persona

If you've been in business for a while, you have no shortage of happy customers. But w ith limited time and resources, you can't choose everyone. So, take some time beforehand to flesh out your target buyer personas.

Once you know precisely who you're targeting, go through your stable of happy customers to find a buyer representative of the audience you're trying to reach. The closer their problems, goals, and industries align, the more your case study will resonate.

What if you have more than one buyer persona? No problem. This is a common situation for companies because buyers comprise an entire committee. You might be marketing to procurement experts, executives, engineers, etc. Try to develop a case study tailored to each key persona. This might be a long-term goal, and that's fine. The better you can personalize the experience for each stakeholder, the easier it is to keep their attention.

Here are a few considerations to think about before research:

- Products/services of yours the customer uses (and how familiar they are with them)

- The customer's brand recognition in the industry

- Whether the results they've achieved are specific and remarkable

- Whether they've switched from a competitor's product/service

- How closely aligned they are with your target audience

These items are just a jumping-off point as you develop your criteria. Once you have a list, run each customer through it to determine your top targets. Approach the ones on the top (your "dream" case study subjects) and work your way down as needed.

Who to interview

You should consider interviewing top-level managers or executives because those are high-profile positions. But consider how close they are to your product and its results.

Focusing on an office manager or engineer who uses your product daily would be better. Look for someone with a courtside view of the effects.

The ways to request customer participation in case studies can vary, but certain principles can improve your chances:

- Make it easy for customers to work with you, respecting their valuable time. Be well-prepared and minimize their involvement.

- Emphasize how customers will benefit through increased publicity, revenue opportunities, or recognition for their success.

- Acknowledge their contributions and showcase their achievements.

- Standardizing the request process with a script incorporating these principles can help your team consistently secure case study approvals and track performance.

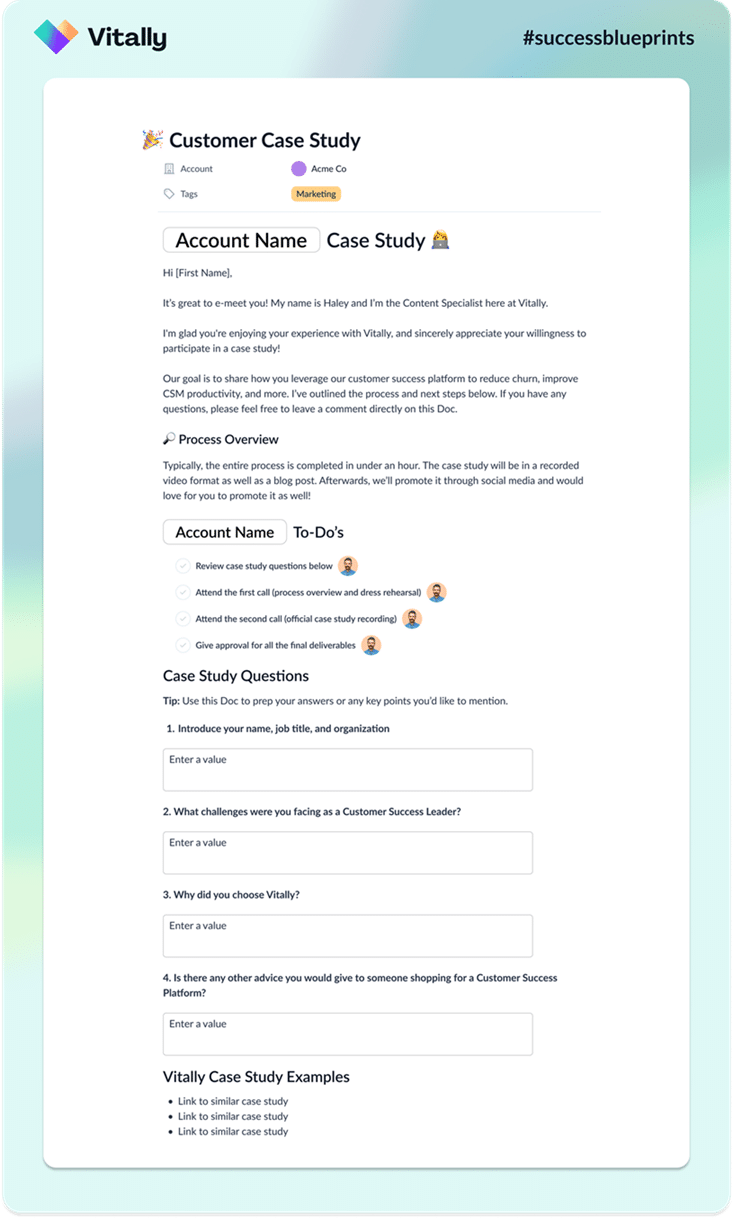

Step 2: Prepare for the interview

Case study interviews are like school exams. The more prepared you are for them, the better they turn out. Preparing thoroughly also shows participants that you value their time. You don't waste precious minutes rehashing things you should have already known. You focus on getting the information you need as efficiently as possible.

You can conduct your case study interview in multiple formats, from exchanging emails to in-person interviews. This isn't a trivial decision. As you'll see in the chart below, each format has its unique advantages and disadvantages.

| Seeing each other's facial expressions puts everyone at ease and encourages case study participants to open up. It's a good format if you're simultaneously conferencing with several people from the customer's team. | Always be on guard for connection issues; not every customer knows the technology. Audio quality will probably be less good than on the phone. When multiple people are talking, pieces of conversation can be lost. | |

| It is a more personal than email because you can hear someone's tone. You can encourage them to continue if they get really excited about certain answers. Convenient and immediate. Dial a number and start interviewing without ever leaving the office. | It isn't as personal as a video chat or an in-person interview because you can't see the customer's face, and nonverbal cues might be missed. Don't get direct quotes like you would with email responses. The only way to preserve the interview is to remember to have it recorded. | |

| The most personal interview style. It feels like an informal conversation, making it easier to tell stories and switch seamlessly between topics. Humanizes the customer's experience and allows you to put a face to the incredible results. | Puts a lot of pressure on customers who are shy or introverted – especially if they're being recorded. Requires the most commitment for the participant – travel, dressing up, dealing with audiovisual equipment, etc. | |

| Gives customers the most flexibility with respect to scheduling. They can answer a few questions, see to their obligations, and return to them at their convenience. No coordination of schedules is needed. Each party can fulfill their obligations whenever they're able to. | There is less opportunity for customers to go “off script” and tell compelling anecdotes that your questions might have overlooked. Some of the study participant's personalities might be lost in their typed responses. It's harder to sense their enthusiasm or frustration. |

You'll also have to consider who will ask and answer the questions during your case study interview. It's wise to consider this while considering the case study format. The number of participants factors into which format will work best. Pulling off an in-person interview becomes much harder if you're trying to juggle four or five people's busy schedules. Try a video conference instead.

Before interviewing your case study participant, it is crucial to identify the specific questions that need to be asked. It's essential to thoroughly evaluate your collaboration with the client and understand how your product's contributions impact the company.

Remember that structuring your case study is akin to crafting a compelling narrative. To achieve this, follow a structured approach:

- Beginning of your story. Delve into the customer's challenge that ultimately led them to do business with you. What were their problems like? What drove them to make a decision finally? Why did they choose you?

- The middle of the case study. Your audience also wants to know about the experience of working with you. Your customer has taken action to address their problems. What happened once you got on board?

- An ending that makes you the hero. Describe the specific results your company produced for the customer. How has the customer's business (and life) changed once they implemented your solution?

Sample questions for the case study interview

If you're preparing for a case study interview, here are some sample case study research questions to help you get started:

- What challenges led you to seek a solution?

- When did you realize the need for immediate action? Was there a tipping point?

- How did you decide on the criteria for choosing a B2B solution, and who was involved?

- What set our product or service apart from others you considered?

- How was your experience working with us post-purchase?

- Were there any pleasant surprises or exceeded expectations during our collaboration?

- How smoothly did your team integrate our solution into their workflows?

- How long before you started seeing positive results?

- How have you benefited from our products or services?

- How do you measure the value our product or service provides?

Step 3: Conduct the interview

Preparing for case study interviews can be different from everyday conversations. Here are some tips to keep in mind:

- Create a comfortable atmosphere. Before diving into the discussion, talk about their business and personal interests. Ensure everyone is at ease, and address any questions or concerns.

- Prioritize key questions. Lead with your most crucial questions to respect your customer's time. Interview lengths can vary, so starting with the essentials ensures you get the vital information.

- Be flexible. Case study interviews don't have to be rigid. If your interviewee goes "off script," embrace it. Their spontaneous responses often provide valuable insights.

- Record the interview. If not conducted via email, ask for permission to record the interview. This lets you focus on the conversation and capture valuable quotes without distractions.

Step 4: Figure out who will create the case study

When creating written case studies for your business, deciding who should handle the writing depends on cost, perspective, and revisions.

Outsourcing might be pricier, but it ensures a professionally crafted outcome. On the other hand, in-house writing has its considerations, including understanding your customers and products.

Technical expertise and equipment are needed for video case studies, which often leads companies to consider outsourcing due to production and editing costs.

Tip: When outsourcing work, it's essential to clearly understand pricing details to avoid surprises and unexpected charges during payment.

Step 5: Utilize storytelling

Understanding and applying storytelling elements can make your case studies unforgettable, offering a competitive edge.

Source: The Framework Bank

Every great study follows a narrative arc (also called a "story arc"). This arc represents how a character faces challenges, struggles against raising stakes, and encounters a formidable obstacle before the tension resolves.

In a case study narrative, consider:

- Exposition. Provide background information about the company, revealing their "old life" before becoming your customer.

- Inciting incident. Highlight the problem that drove the customer to seek a solution, creating a sense of urgency.

- Obstacles (rising action). Describe the customer's journey in researching and evaluating solutions, building tension as they explore options.

- Midpoint. Explain what made the business choose your product or service and what set you apart.

- Climax. Showcase the success achieved with your product.

- Denouement. Describe the customer's transformed business and end with a call-to-action for the reader to take the next step.

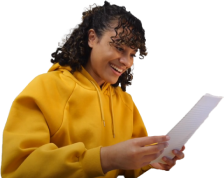

Step 6: Design the case study

The adage "Don't judge a book by its cover" is familiar, but people tend to do just that quite often!

A poor layout can deter readers even if you have an outstanding case study. To create an engaging case study, follow these steps:

- Craft a compelling title. Just like you wouldn't read a newspaper article without an eye-catching headline, the same goes for case studies. Start with a title that grabs attention.

- Organize your content. Break down your content into different sections, such as challenges, results, etc. Each section can also include subsections. This case study approach divides the content into manageable portions, preventing readers from feeling overwhelmed by lengthy blocks of text.

- Conciseness is key. Keep your case study as concise as possible. The most compelling case studies are precisely long enough to introduce the customer's challenge, experience with your solution, and outstanding results. Prioritize clarity and omit any sections that may detract from the main storyline.

- Utilize visual elements. To break up text and maintain reader interest, incorporate visual elements like callout boxes, bulleted lists, and sidebars.

- Include charts and images. Summarize results and simplify complex topics by including pictures and charts. Visual aids enhance the overall appeal of your case study.

- Embrace white space. Avoid overwhelming walls of text to prevent reader fatigue. Opt for plenty of white space, use shorter paragraphs, and employ subsections to ensure easy readability and navigation.

- Enhance video case studies. In video case studies, elements like music, fonts, and color grading are pivotal in setting the right tone. Choose music that complements your message and use it strategically throughout your story. Carefully select fonts to convey the desired style, and consider how lighting and color grading can influence the mood. These elements collectively help create the desired tone for your video case study.

Step 7: Edits and revisions

Once you've finished the interview and created your case study, the hardest part is over. Now's the time for editing and revision. This might feel frustrating for impatient B2B marketers, but it can turn good stories into great ones.

Ideally, you'll want to submit your case study through two different rounds of editing and revisions:

- Internal review. Seek feedback from various team members to ensure your case study is captivating and error-free. Gather perspectives from marketing, sales, and those in close contact with customers for well-rounded insights. Use patterns from this feedback to guide revisions and apply lessons to future case studies.

- Customer feedback. Share the case study with customers to make them feel valued and ensure accuracy. Let them review quotes and data points, as they are the "heroes" of the story, and their logos will be prominently featured. This step maintains positive customer relationships.

Case study mistakes to avoid

- Ensure easy access to case studies on your website.

- Spotlight the customer, not just your business.

- Tailor each case study to a specific audience.

- Avoid excessive industry jargon in your content.

Step 8: Publishing

Take a moment to proofread your case study one more time carefully. Even if you're reasonably confident you've caught all the errors, it's always a good idea to check. Your case study will be a valuable marketing tool for years, so it's worth the investment to ensure it's flawless. Once done, your case study is all set to go!

Consider sharing a copy of the completed case study with your customer as a thoughtful gesture. They'll likely appreciate it; some may want to keep it for their records. After all, your case study wouldn't have been possible without their help, and they deserve to see the final product.

Where you publish your case study depends on its role in your overall marketing strategy. If you want to reach as many people as possible with your case study, consider publishing it on your website and social media platforms.

Tip: Some companies prefer to keep their case studies exclusive, making them available only to those who request them. This approach is often taken to control access to valuable information and to engage more deeply with potential customers who express specific interests. It can create a sense of exclusivity and encourage interested parties to engage directly with the company.

Step 9: Case study distribution

When sharing individual case studies, concentrate on reaching the audience with the most influence on purchasing decisions

Here are some common distribution channels to consider:

- Sales teams. Share case studies to enhance customer interactions, retention , and upselling among your sales and customer success teams. Keep them updated on new studies and offer easily accessible formats like PDFs or landing page links.

- Company website. Feature case studies on your website to establish authority and provide valuable information to potential buyers. Organize them by categories such as location, size, industry, challenges, and products or services used for effective presentation.

- Events. Use live events like conferences and webinars to distribute printed case study copies, showcase video case studies at trade show booths, and conclude webinars with links to your case study library. This creative approach blends personal interactions with compelling content.

- Industry journalists. Engage relevant industry journalists to gain media coverage by identifying suitable publications and journalists covering related topics. Building relationships is vital, and platforms like HARO (Help A Reporter Out) can facilitate connections, especially if your competitors have received coverage before.

Want to learn more about Marketing Analytics Software? Explore Marketing Analytics products.

It can seem daunting to transform the information you've gathered into a cohesive narrative. We’ve created a versatile case study template that can serve as a solid starting point for your case study.

With this template, your business can explore any solutions offered to satisfied customers, covering their background, the factors that led them to choose your services, and their outcomes.

The template boasts a straightforward design, featuring distinct sections that guide you in effectively narrating your and your customer's story. However, remember that limitless ways to showcase your business's accomplishments exist.

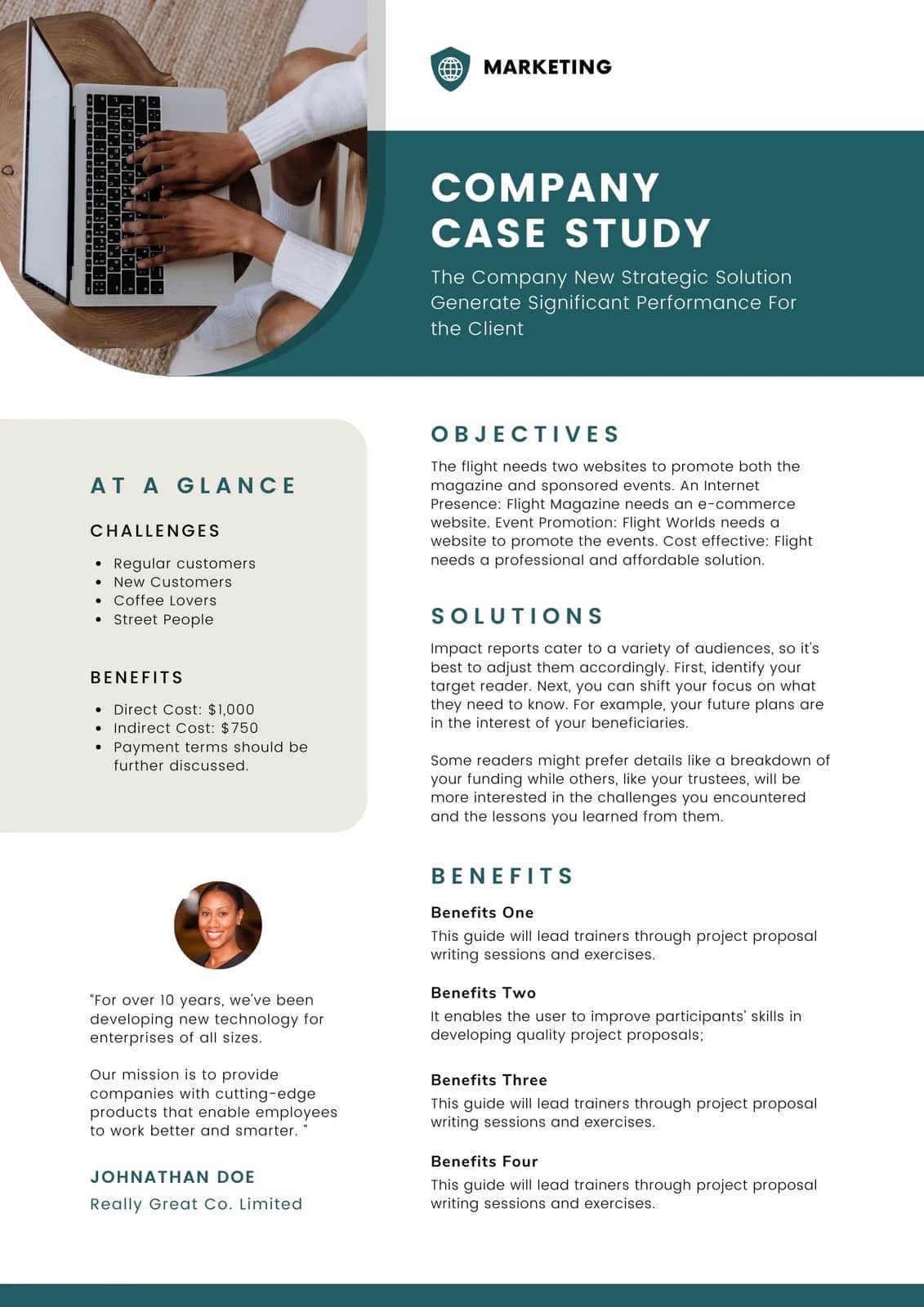

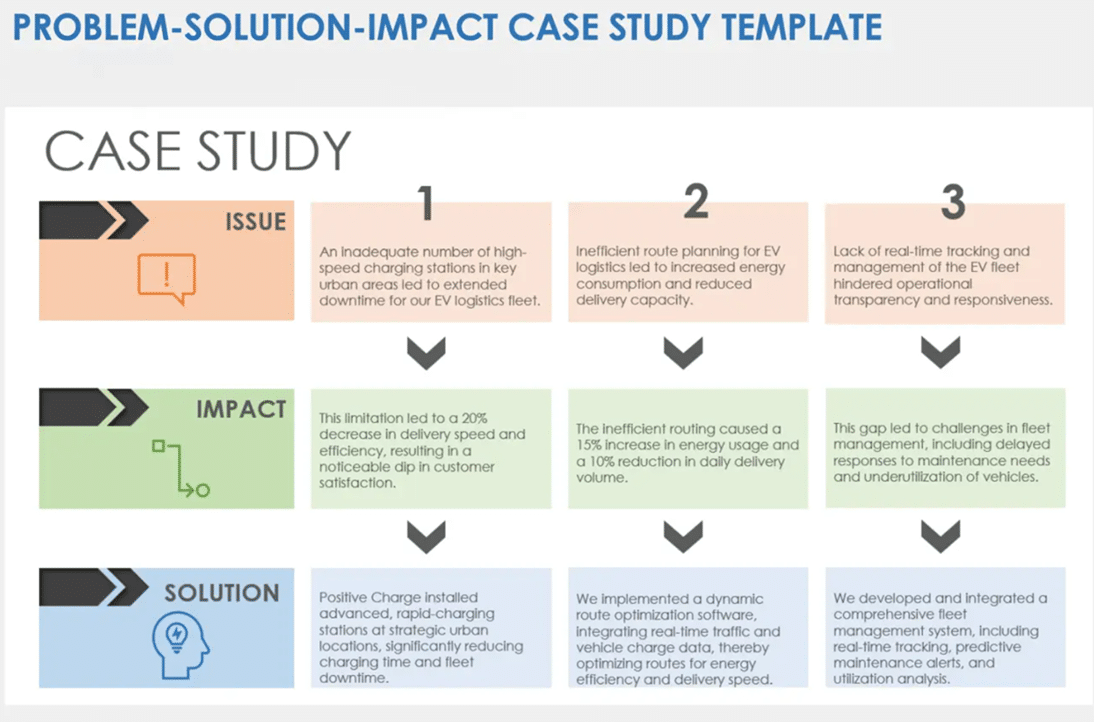

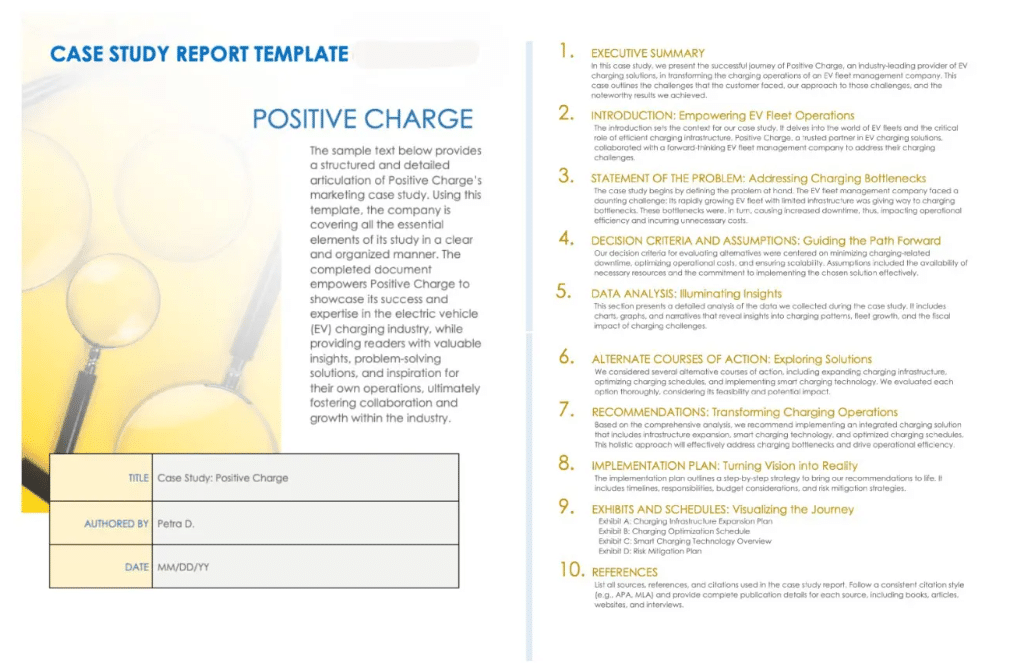

To assist you in this process, here's a breakdown of the recommended sections to include in a case study:

- Title. Keep it concise. Create a brief yet engaging project title summarizing your work with your subject. Consider your title like a newspaper headline; do it well, and readers will want to learn more.

- Subtitle . Use this section to elaborate on the achievement briefly. Make it creative and catchy to engage your audience.

- Executive summary. Use this as an overview of the story, followed by 2-3 bullet points highlighting key success metrics.

- Challenges and objectives. This section describes the customer's challenges before adopting your product or service, along with the goals or objectives they sought to achieve.

- How product/service helped. A paragraph explaining how your product or service addressed their problem.

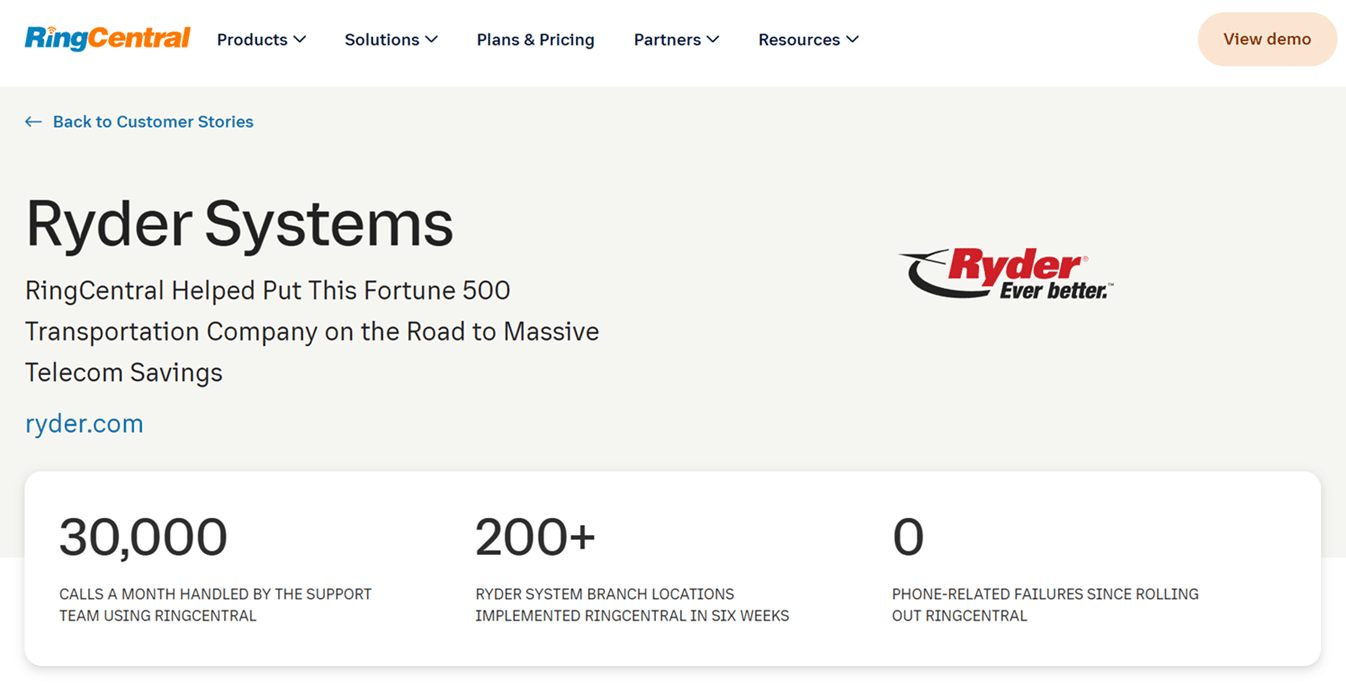

- Testimonials. Incorporate short quotes or statements from the individuals involved in the case study, sharing their perspectives and experiences.

- Supporting visuals. Include one or two impactful visuals, such as graphs, infographics, or highlighted metrics, that reinforce the narrative.

- Call to action (CTA). If you do your job well, your audience will read (or watch) your case studies from beginning to end. They are interested in everything you've said. Now, what's the next step they should take to continue their relationship with you? Give people a simple action they can complete.

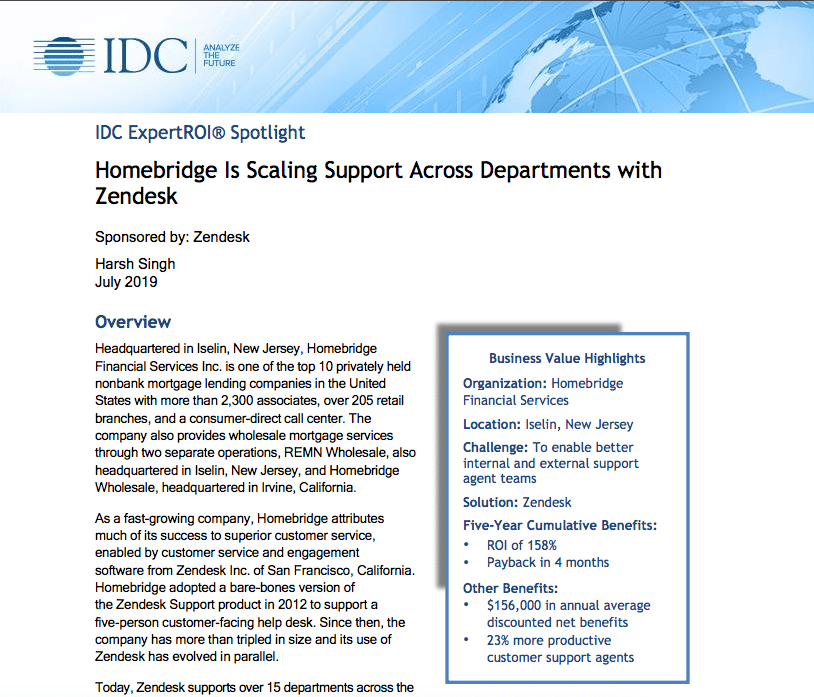

Case studies are proven marketing strategies in a wide variety of B2B industries. Here are just a few examples of a case study:

- Amazon Web Services, Inc. provides companies with cloud computing platforms and APIs on a metered, pay-as-you-go basis. This case study example illustrates the benefits Thomson Reuters experienced using AWS.

- LinkedIn Marketing Solutions combines captivating visuals with measurable results in the case study created for BlackRock. This case study illustrates how LinkedIn has contributed to the growth of BlackRock's brand awareness over the years.

- Salesforce , a sales and marketing automation SaaS solutions provider, seamlessly integrates written and visual elements to convey its success stories with Pepe Jeans. This case study effectively demonstrates how Pepe Jeans is captivating online shoppers with immersive and context-driven e-commerce experiences through Salesforce.

- HubSpot offers a combination of sales and marketing tools. Their case study demonstrates the effectiveness of its all-in-one solutions. These typically focus on a particular client's journey and how HubSpot helped them achieve significant results.

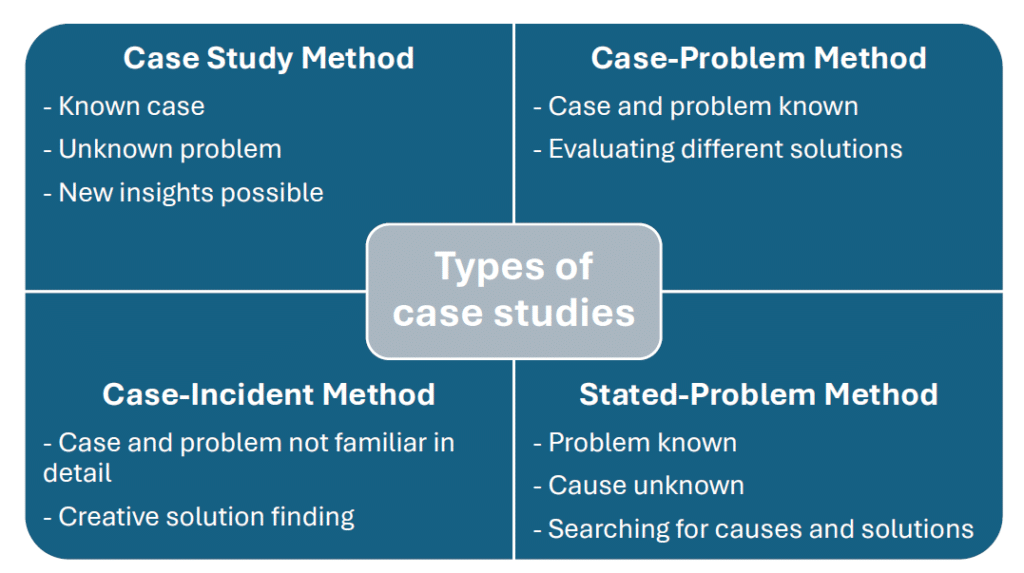

There are two different types of case studies that businesses might utilize:

Written case studies

Written case studies offer readers a clear visual representation of data, which helps them quickly identify and focus on the information that matters most.

Printed versions of case studies find their place at events like trade shows, where they serve as valuable sales collateral to engage prospective clients. Even in the digital age, many businesses provide case studies in PDF format or as web-based landing pages, improving accessibility for their audience.

Note: Landing pages , in particular, offer the flexibility to incorporate rich multimedia content, including images, charts, and videos. This flexibility in design makes landing pages an attractive choice for presenting detailed content to the audience.

Written case study advantages

Here are several significant advantages to leveraging case studies for your company:

- Hyperlink accessibility. Whether in PDF or landing page format, written case studies allow for embedded hyperlinks, offering prospects easy access to additional information and contact forms.

- Flexible engagement. Unlike video case studies, which may demand in-person arrangements, written case studies can be conducted via phone or video streaming, reducing customer commitment and simplifying scheduling.

- Efficient scanning . Well-structured written case studies with a scannable format cater to time-strapped professionals. Charts and callout boxes with key statistics enhance the ease of information retrieval.

- Printable for offline use. Written case studies can be effortlessly printed and distributed at trade shows, sales meetings, and live events. This tangible format accommodates those who prefer physical materials and provides versatility in outreach, unlike video content, which is less portable.

Written case study disadvantages

Here are some drawbacks associated with the use of case studies:

- Reduced emotional impact. Written content lacks the emotional punch of live video testimonials, which engage more senses and emotions, making a stronger connection.

- Consider time investment. Creating a compelling case study involves editing, proofreading, and design collaboration, with multiple revisions commonly required before publication.

- Challenges in maintaining attention. Attention spans are short in today's ad-saturated world. Using graphics, infographics, and videos more often is more powerful to incite the right emotions in customers.

Video case studies

Video case studies are the latest marketing trend. Unlike in the past, when video production was costly, today's tools make it more accessible for users to create and edit their videos. However, specific technical requirements still apply.

Like written case studies, video case studies delve into a specific customer's challenges and how your business provides solutions. Yet, the video offers a more profound connection by showcasing the person who faced and conquered the problem.

Video case studies can boost brand exposure when shared on platforms like YouTube. For example, Slack's engaging case study video with Sandwich Video illustrates how Slack transformed its workflow and adds humor, which can be challenging in written case studies focused on factual evidence.

Source : YouTube

This video case study has garnered nearly a million views on YouTube.

Video case study advantages

Here are some of the top advantages of video case studies. While video testimonials take more time, the payoff can be worth it.

- Humanization and authenticity. Video case studies connect viewers with real people, adding authenticity and fostering a stronger emotional connection.

- Engaging multiple senses. They engage both auditory and visual senses, enhancing credibility and emotional impact. Charts, statistics, and images can also be incorporated.

- Broad distribution. Videos can be shared on websites, YouTube, social media, and more, reaching diverse audiences and boosting engagement, especially on social platforms.

Video case study disadvantages

Before fully committing to video testimonials, consider the following:

- Technical expertise and equipment. Video production requires technical know-how and equipment, which can be costly. Skilled video editing is essential to maintain a professional image. While technology advances, producing amateurish videos may harm your brand's perception.

- Viewer convenience. Some prospects prefer written formats due to faster reading and ease of navigation. Video typically requires sound, which can be inconvenient for viewers in specific settings. Many people may not have headphones readily available to watch your content.

- Demand on case study participants. On-camera interviews can be time-consuming and location-dependent, making scheduling challenging for case study participants. Additionally, being on screen for a global audience may create insecurities and performance pressure.

- Comfort on camera. Not everyone feels at ease on camera. Nervousness or a different on-screen persona can impact the effectiveness of the testimonial, and discovering this late in the process can be problematic.

Written or video case studies: Which is right for you?

Now that you know the pros and cons of each, how do you choose which is right for you?

One of the most significant factors in doing video case studies can be the technical expertise and equipment required for a high level of production quality. Whether you have the budget to do this in-house or hire a production company can be one of the major deciding factors.

Still, written or video doesn't have to be an either-or decision. Some B2B companies are using both formats. They can complement each other nicely, minimizing the downsides mentioned above and reaching your potential customers where they prefer.

Let's say you're selling IT network security. What you offer is invaluable but complicated. You could create a short (three- or four-minute) video case study to get attention and touch on the significant benefits of your services. This whets the viewer's appetite for more information, which they could find in a written case study that supplements the video.

Should you decide to test the water in video case studies, test their effectiveness among your target audience. See how well they work for your company and sales team. And, just like a written case study, you can always find ways to improve your process as you continue exploring video case studies.

Case studies offer several distinctive advantages, making them an ideal tool for businesses to market their products to customers. However, their benefits extend beyond these qualities.

Here's an overview of all the advantages of case studies:

Valuable sales support

Case studies serve as a valuable resource for your sales endeavors. Buyers frequently require additional information before finalizing a purchase decision. These studies provide concrete evidence of your product or service's effectiveness, assisting your sales representatives in closing deals more efficiently, especially with customers with lingering uncertainties.

Validating your value

Case studies serve as evidence of your product or service's worth or value proposition , playing a role in building trust with potential customers. By showcasing successful partnerships, you make it easier for prospects to place trust in your offerings. This effect is particularly notable when the featured customer holds a reputable status.

Unique and engaging content

By working closely with your customer success teams, you can uncover various customer stories that resonate with different prospects. Case studies allow marketers to shape product features and benefits into compelling narratives.

Each case study's distinctiveness, mirroring the uniqueness of every customer's journey, makes them a valuable source of relatable and engaging content. Storytelling possesses the unique ability to connect with audiences on an emotional level, a dimension that statistics alone often cannot achieve.

Spotlighting valuable customers

Case studies provide a valuable platform for showcasing your esteemed customers. Featuring them in these studies offers a chance to give them visibility and express your gratitude for the partnership, which can enhance customer loyalty . Depending on the company you are writing about, it can also demonstrate the caliber of your business.

Now is the time to get SaaS-y news and entertainment with our 5-minute newsletter, G2 Tea , featuring inspiring leaders, hot takes, and bold predictions. Subscribe below!

It's important to consider limitations when designing and interpreting the results of case studies. Here's an overview of the limitations of case studies:

Challenges in replication

Case studies often focus on specific individuals, organizations, or situations, making generalizing their findings to broader populations or contexts challenging.

Time-intensive process

Case studies require a significant time investment. The extensive data collection process and the need for comprehensive analysis can be demanding, especially for researchers who are new to this method.

Potential for errors

Case studies can be influenced by memory and judgment, potentially leading to inaccuracies. Depending on human memory to reconstruct a case's history may result in variations and potential inconsistencies in how individuals recall past events. Additionally, bias may emerge, as individuals tend to prioritize what they consider most significant, which could limit their consideration of alternative perspectives.

Challenges in verification

Confirming results through additional research can present difficulties. This complexity arises from the need for detailed and extensive data in the initial creation of a case study. Consequently, this process requires significant effort and a substantial amount of time.

While looking at case studies, you may have noticed a quote. This type of quote is considered a testimonial, a key element of case studies.

If a customer's quote proves that your brand does what it says it will or performs as expected, you may wonder: 'Aren't customer testimonials and case studies the same thing?' Not exactly.

Testimonials are brief endorsements designed to establish trust on a broad scale. In contrast, case studies are detailed narratives that offer a comprehensive understanding of how a product or service addresses a specific problem, targeting a more focused audience.

Crafting case studies requires more resources and a structured approach than testimonials. Your selection between the two depends on your marketing objectives and the complexity of your product or service.

Case in point!

Case studies are among a company's most effective tools. You're well on your way to mastering them.

Today's buyers are tackling much of the case study research methodology independently. Many are understandably skeptical before making a buying decision. By connecting them with multiple case studies, you can prove you've gotten the results you say you can. There's hardly a better way to boost your credibility and persuade them to consider your solution.

Case study formats and distribution methods might change as technology evolves. However, the fundamentals that make them effective—knowing how to choose subjects, conduct interviews, and structure everything to get attention—will serve you for as long as you're in business.

We covered a ton of concepts and resources, so go ahead and bookmark this page. You can refer to it whenever you have questions or need a refresher.

Dive into market research to uncover customer preferences and spending habits.

Kristen McCabe

Kristen’s is a former senior content marketing specialist at G2. Her global marketing experience extends from Australia to Chicago, with expertise in B2B and B2C industries. Specializing in content, conversions, and events, Kristen spends her time outside of work time acting, learning nature photography, and joining in the #instadog fun with her Pug/Jack Russell, Bella. (she/her/hers)

Explore More G2 Articles

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved August 30, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

How to Write a Case Study: A Step-by-Step Guide (+ Examples)

by Todd Brehe

on Jan 3, 2024

If you want to learn how to write a case study that engages prospective clients, demonstrates that you can solve real business problems, and showcases the results you deliver, this guide will help.

We’ll give you a proven template to follow, show you how to conduct an engaging interview, and give you several examples and tips for best practices.

Let’s start with the basics.

What is a Case Study?

A business case study is simply a story about how you successfully delivered a solution to your client.

Case studies start with background information about the customer, describe problems they were facing, present the solutions you developed, and explain how those solutions positively impacted the customer’s business.

Do Marketing Case Studies Really Work?

Absolutely. A well-written case study puts prospective clients into the shoes of your paying clients, encouraging them to engage with you. Plus, they:

- Get shared “behind the lines” with decision makers you may not know;

- Leverage the power of “social proof” to encourage a prospective client to take a chance with your company;

- Build trust and foster likeability;

- Lessen the perceived risk of doing business with you and offer proof that your business can deliver results;

- Help prospects become aware of unrecognized problems;

- Show prospects experiencing similar problems that possible solutions are available (and you can provide said solutions);

- Make it easier for your target audience to find you when using Google and other search engines.

Case studies serve your clients too. For example, they can generate positive publicity and highlight the accomplishments of line staff to the management team. Your company might even throw in a new product/service discount, or a gift as an added bonus.

But don’t just take my word for it. Let’s look at a few statistics and success stories:

5 Winning Case Study Examples to Model

Before we get into the nuts and bolts of how to write a case study, let’s go over a few examples of what an excellent one looks like.

The five case studies listed below are well-written, well-designed, and incorporate a time-tested structure.

1. Lane Terralever and Pinnacle at Promontory

This case study example from Lane Terralever incorporates images to support the content and effectively uses subheadings to make the piece scannable.

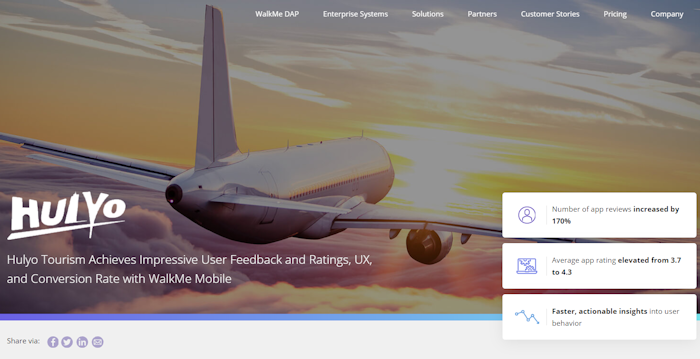

2. WalkMe Mobile and Hulyo

This case study from WalkMe Mobile leads with an engaging headline and the three most important results the client was able to generate.

In the first paragraph, the writer expands the list of accomplishments encouraging readers to learn more.

3. CurationSuite Listening Engine

This is an example of a well-designed printable case study . The client, specific problem, and solution are called out in the left column and summarized succinctly.

4. Brain Traffic and ASAE

This long format case study (6 pages) from Brain Traffic summarizes the challenges, solutions, and results prominently in the left column. It uses testimonials and headshots of the case study participants very effectively.

5. Adobe and Home Depot

This case study from Adobe and Home Depot is a great example of combining video, attention-getting graphics, and long form writing. It also uses testimonials and headshots well.

Now that we’ve gone over the basics and showed a few great case study examples you can use as inspiration, let’s roll up our sleeves and get to work.

A Case Study Structure That Pros Use

Let’s break down the structure of a compelling case study:

Choose Your Case Study Format

In this guide, we focus on written case studies. They’re affordable to create, and they have a proven track record. However, written case studies are just one of four case study formats to consider:

- Infographic

If you have the resources, video (like the Adobe and Home Depot example above) and podcast case studies can be very compelling. Hearing a client discuss in his or her own words how your company helped is an effective content marketing strategy

Infographic case studies are usually one-page images that summarize the challenge, proposed solution, and results. They tend to work well on social media.

Follow a Tried-and-True Case Study Template

The success story structure we’re using incorporates a “narrative” or “story arc” designed to suck readers in and captivate their interest.

Note: I recommend creating a blog post or landing page on your website that includes the text from your case study, along with a downloadable PDF. Doing so helps people find your content when they perform Google and other web searches.

There are a few simple SEO strategies that you can apply to your blog post that will optimize your chances of being found. I’ll include those tips below.

Craft a Compelling Headline

The headline should capture your audience’s attention quickly. Include the most important result you achieved, the client’s name, and your company’s name. Create several examples, mull them over a bit, then pick the best one. And, yes, this means writing the headline is done at the very end.

SEO Tip: Let’s say your firm provided “video editing services” and you want to target this primary keyword. Include it, your company name, and your client’s name in the case study title.

Write the Executive Summary

This is a mini-narrative using an abbreviated version of the Challenge + Solution + Results model (3-4 short paragraphs). Write this after you complete the case study.

SEO Tip: Include your primary keyword in the first paragraph of the Executive Summary.

Provide the Client’s Background

Introduce your client to the reader and create context for the story.

List the Customer’s Challenges and Problems

Vividly describe the situation and problems the customer was dealing with, before working with you.

SEO Tip: To rank on page one of Google for our target keyword, review the questions listed in the “People also ask” section at the top of Google’s search results. If you can include some of these questions and their answers into your case study, do so. Just make sure they fit with the flow of your narrative.

Detail Your Solutions

Explain the product or service your company provided, and spell out how it alleviated the client’s problems. Recap how the solution was delivered and implemented. Describe any training needed and the customer’s work effort.

Show Your Results

Detail what you accomplished for the customer and the impact your product/service made. Objective, measurable results that resonate with your target audience are best.

List Future Plans

Share how your client might work with your company in the future.

Give a Call-to-Action

Clearly detail what you want the reader to do at the end of your case study.

Talk About You

Include a “press release-like” description of your client’s organization, with a link to their website. For your printable document, add an “About” section with your contact information.

And that’s it. That’s the basic structure of any good case study.

Now, let’s go over how to get the information you’ll use in your case study.

How to Conduct an Engaging Case Study Interview

One of the best parts of creating a case study is talking with your client about the experience. This is a fun and productive way to learn what your company did well, and what it can improve on, directly from your customer’s perspective.

Here are some suggestions for conducting great case study interviews:

When Choosing a Case Study Subject, Pick a Raving Fan

Your sales and marketing team should know which clients are vocal advocates willing to talk about their experiences. Your customer service and technical support teams should be able to contribute suggestions.

Clients who are experts with your product/service make solid case study candidates. If you sponsor an online community, look for product champions who post consistently and help others.

When selecting a candidate, think about customer stories that would appeal to your target audience. For example, let’s say your sales team is consistently bumping into prospects who are excited about your solution, but are slow to pull the trigger and do business with you.

In this instance, finding a client who felt the same way, but overcame their reluctance and contracted with you anyway, would be a compelling story to capture and share.

Prepping for the Interview

If you’ve ever seen an Oprah interview, you’ve seen a master who can get almost anyone to open up and talk. Part of the reason is that she and her team are disciplined about planning.

Before conducting a case study interview, talk to your own team about the following:

- What’s unique about the client (location, size, industry, etc.) that will resonate with our prospects?

- Why did the customer select us?

- How did we help the client?

- What’s unique about this customer’s experience?

- What problems did we solve?

- Were any measurable, objective results generated?

- What do we want readers to do after reading this case study analysis?

Pro Tip: Tee up your client. Send them the questions in advance.

Providing questions to clients before the interview helps them prepare, gather input from other colleagues if needed, and feel more comfortable because they know what to expect.

In a moment, I’ll give you an exhaustive list of interview questions. But don’t send them all. Instead, pare the list down to one or two questions in each section and personalize them for your customer.

Nailing the Client Interview

Decide how you’ll conduct the interview. Will you call the client, use Skype or Facetime, or meet in person? Whatever mode you choose, plan the process in advance.

Make sure you record the conversation. It’s tough to lead an interview, listen to your contact’s responses, keep the conversation flowing, write notes, and capture all that the person is saying.

A recording will make it easier to write the client’s story later. It’s also useful for other departments in your company (management, sales, development, etc.) to hear real customer feedback.

Use open-ended questions that spur your contact to talk and share. Here are some real-life examples:

Introduction

- Recap the purpose of the call. Confirm how much time your contact has to talk (30-45 minutes is preferable).

- Confirm the company’s location, number of employees, years in business, industry, etc.

- What’s the contact’s background, title, time with the company, primary responsibilities, and so on?

Initial Challenges

- Describe the situation at your company before engaging with us?

- What were the initial problems you wanted to solve?

- What was the impact of those problems?

- When did you realize you had to take some action?

- What solutions did you try?

- What solutions did you implement?

- What process did you go through to make a purchase?

- How did the implementation go?

- How would you describe the work effort required of your team?

- If training was involved, how did that go?

Results, Improvements, Progress

- When did you start seeing improvements?

- What were the most valuable results?

- What did your team like best about working with us?

- Would you recommend our solution/company? Why?

Future Plans

- How do you see our companies working together in the future?

Honest Feedback

- Our company is very focused on continual improvement. What could we have done differently to make this an even better experience?

- What would you like us to add or change in our product/service?

During the interview, use your contact’s responses to guide the conversation.

Once the interview is complete, it’s time to write your case study.

How to Write a Case Study… Effortlessly

Case study writing is not nearly as difficult as many people make it out to be. And you don’t have to be Stephen King to do professional work. Here are a few tips:

- Use the case study structure that we outlined earlier, but write these sections first: company background, challenges, solutions, and results.

- Write the headline, executive summary, future plans, and call-to-action (CTA) last.

- In each section, include as much content from your interview as you can. Don’t worry about editing at this point

- Tell the story by discussing their trials and tribulations.

- Stay focused on the client and the results they achieved.

- Make their organization and employees shine.

- When including information about your company, frame your efforts in a supporting role.

Also, make sure to do the following:

Add Testimonials, Quotes, and Visuals

The more you can use your contact’s words to describe the engagement, the better. Weave direct quotes throughout your narrative.

Strive to be conversational when you’re writing case studies, as if you’re talking to a peer.

Include images in your case study that visually represent the content and break up the text. Photos of the company, your contact, and other employees are ideal.

If you need to incorporate stock photos, here are three resources:

- Deposit p hotos

And if you need more, check out Smart Blogger’s excellent resource: 17 Sites with High-Quality, Royalty-Free Stock Photos .

Proofread and Tighten Your Writing

Make sure there are no grammar, spelling, or punctuation errors. If you need help, consider using a grammar checker tool like Grammarly .

My high school English teacher’s mantra was “tighten your writing.” She taught that impactful writing is concise and free of weak, unnecessary words . This takes effort and discipline, but will make your writing stronger.

Also, keep in mind that we live in an attention-diverted society. Before your audience will dive in and read each paragraph, they’ll first scan your work. Use subheadings to summarize information, convey meaning quickly, and pull the reader in.

Be Sure to Use Best Practices