Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 24, Issue 2

- Five tips for developing useful literature summary tables for writing review articles

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0157-5319 Ahtisham Younas 1 , 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7839-8130 Parveen Ali 3 , 4

- 1 Memorial University of Newfoundland , St John's , Newfoundland , Canada

- 2 Swat College of Nursing , Pakistan

- 3 School of Nursing and Midwifery , University of Sheffield , Sheffield , South Yorkshire , UK

- 4 Sheffield University Interpersonal Violence Research Group , Sheffield University , Sheffield , UK

- Correspondence to Ahtisham Younas, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St John's, NL A1C 5C4, Canada; ay6133{at}mun.ca

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2021-103417

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

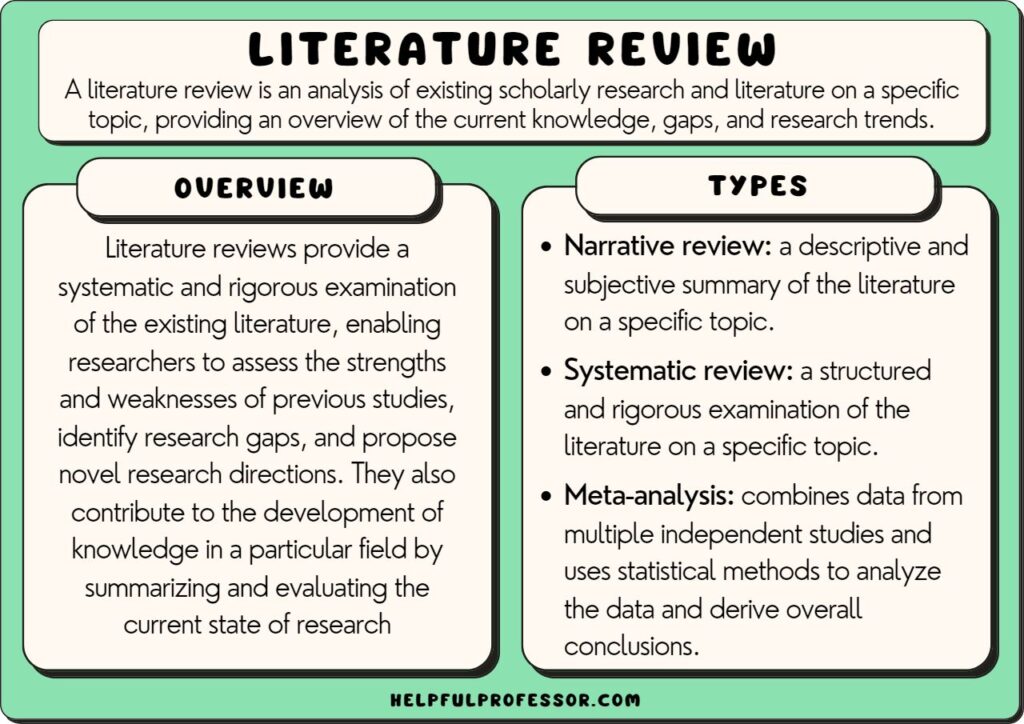

Introduction

Literature reviews offer a critical synthesis of empirical and theoretical literature to assess the strength of evidence, develop guidelines for practice and policymaking, and identify areas for future research. 1 It is often essential and usually the first task in any research endeavour, particularly in masters or doctoral level education. For effective data extraction and rigorous synthesis in reviews, the use of literature summary tables is of utmost importance. A literature summary table provides a synopsis of an included article. It succinctly presents its purpose, methods, findings and other relevant information pertinent to the review. The aim of developing these literature summary tables is to provide the reader with the information at one glance. Since there are multiple types of reviews (eg, systematic, integrative, scoping, critical and mixed methods) with distinct purposes and techniques, 2 there could be various approaches for developing literature summary tables making it a complex task specialty for the novice researchers or reviewers. Here, we offer five tips for authors of the review articles, relevant to all types of reviews, for creating useful and relevant literature summary tables. We also provide examples from our published reviews to illustrate how useful literature summary tables can be developed and what sort of information should be provided.

Tip 1: provide detailed information about frameworks and methods

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Tabular literature summaries from a scoping review. Source: Rasheed et al . 3

The provision of information about conceptual and theoretical frameworks and methods is useful for several reasons. First, in quantitative (reviews synthesising the results of quantitative studies) and mixed reviews (reviews synthesising the results of both qualitative and quantitative studies to address a mixed review question), it allows the readers to assess the congruence of the core findings and methods with the adapted framework and tested assumptions. In qualitative reviews (reviews synthesising results of qualitative studies), this information is beneficial for readers to recognise the underlying philosophical and paradigmatic stance of the authors of the included articles. For example, imagine the authors of an article, included in a review, used phenomenological inquiry for their research. In that case, the review authors and the readers of the review need to know what kind of (transcendental or hermeneutic) philosophical stance guided the inquiry. Review authors should, therefore, include the philosophical stance in their literature summary for the particular article. Second, information about frameworks and methods enables review authors and readers to judge the quality of the research, which allows for discerning the strengths and limitations of the article. For example, if authors of an included article intended to develop a new scale and test its psychometric properties. To achieve this aim, they used a convenience sample of 150 participants and performed exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on the same sample. Such an approach would indicate a flawed methodology because EFA and CFA should not be conducted on the same sample. The review authors must include this information in their summary table. Omitting this information from a summary could lead to the inclusion of a flawed article in the review, thereby jeopardising the review’s rigour.

Tip 2: include strengths and limitations for each article

Critical appraisal of individual articles included in a review is crucial for increasing the rigour of the review. Despite using various templates for critical appraisal, authors often do not provide detailed information about each reviewed article’s strengths and limitations. Merely noting the quality score based on standardised critical appraisal templates is not adequate because the readers should be able to identify the reasons for assigning a weak or moderate rating. Many recent critical appraisal checklists (eg, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool) discourage review authors from assigning a quality score and recommend noting the main strengths and limitations of included studies. It is also vital that methodological and conceptual limitations and strengths of the articles included in the review are provided because not all review articles include empirical research papers. Rather some review synthesises the theoretical aspects of articles. Providing information about conceptual limitations is also important for readers to judge the quality of foundations of the research. For example, if you included a mixed-methods study in the review, reporting the methodological and conceptual limitations about ‘integration’ is critical for evaluating the study’s strength. Suppose the authors only collected qualitative and quantitative data and did not state the intent and timing of integration. In that case, the strength of the study is weak. Integration only occurred at the levels of data collection. However, integration may not have occurred at the analysis, interpretation and reporting levels.

Tip 3: write conceptual contribution of each reviewed article

While reading and evaluating review papers, we have observed that many review authors only provide core results of the article included in a review and do not explain the conceptual contribution offered by the included article. We refer to conceptual contribution as a description of how the article’s key results contribute towards the development of potential codes, themes or subthemes, or emerging patterns that are reported as the review findings. For example, the authors of a review article noted that one of the research articles included in their review demonstrated the usefulness of case studies and reflective logs as strategies for fostering compassion in nursing students. The conceptual contribution of this research article could be that experiential learning is one way to teach compassion to nursing students, as supported by case studies and reflective logs. This conceptual contribution of the article should be mentioned in the literature summary table. Delineating each reviewed article’s conceptual contribution is particularly beneficial in qualitative reviews, mixed-methods reviews, and critical reviews that often focus on developing models and describing or explaining various phenomena. Figure 2 offers an example of a literature summary table. 4

Tabular literature summaries from a critical review. Source: Younas and Maddigan. 4

Tip 4: compose potential themes from each article during summary writing

While developing literature summary tables, many authors use themes or subthemes reported in the given articles as the key results of their own review. Such an approach prevents the review authors from understanding the article’s conceptual contribution, developing rigorous synthesis and drawing reasonable interpretations of results from an individual article. Ultimately, it affects the generation of novel review findings. For example, one of the articles about women’s healthcare-seeking behaviours in developing countries reported a theme ‘social-cultural determinants of health as precursors of delays’. Instead of using this theme as one of the review findings, the reviewers should read and interpret beyond the given description in an article, compare and contrast themes, findings from one article with findings and themes from another article to find similarities and differences and to understand and explain bigger picture for their readers. Therefore, while developing literature summary tables, think twice before using the predeveloped themes. Including your themes in the summary tables (see figure 1 ) demonstrates to the readers that a robust method of data extraction and synthesis has been followed.

Tip 5: create your personalised template for literature summaries

Often templates are available for data extraction and development of literature summary tables. The available templates may be in the form of a table, chart or a structured framework that extracts some essential information about every article. The commonly used information may include authors, purpose, methods, key results and quality scores. While extracting all relevant information is important, such templates should be tailored to meet the needs of the individuals’ review. For example, for a review about the effectiveness of healthcare interventions, a literature summary table must include information about the intervention, its type, content timing, duration, setting, effectiveness, negative consequences, and receivers and implementers’ experiences of its usage. Similarly, literature summary tables for articles included in a meta-synthesis must include information about the participants’ characteristics, research context and conceptual contribution of each reviewed article so as to help the reader make an informed decision about the usefulness or lack of usefulness of the individual article in the review and the whole review.

In conclusion, narrative or systematic reviews are almost always conducted as a part of any educational project (thesis or dissertation) or academic or clinical research. Literature reviews are the foundation of research on a given topic. Robust and high-quality reviews play an instrumental role in guiding research, practice and policymaking. However, the quality of reviews is also contingent on rigorous data extraction and synthesis, which require developing literature summaries. We have outlined five tips that could enhance the quality of the data extraction and synthesis process by developing useful literature summaries.

- Aromataris E ,

- Rasheed SP ,

Twitter @Ahtisham04, @parveenazamali

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Welcome to the new OASIS website! We have academic skills, library skills, math and statistics support, and writing resources all together in one new home.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Common Assignments: Literature Review Matrix

Literature review matrix.

As you read and evaluate your literature there are several different ways to organize your research. Courtesy of Dr. Gary Burkholder in the School of Psychology, these sample matrices are one option to help organize your articles. These documents allow you to compile details about your sources, such as the foundational theories, methodologies, and conclusions; begin to note similarities among the authors; and retrieve citation information for easy insertion within a document.

You can review the sample matrixes to see a completed form or download the blank matrix for your own use.

- Literature Review Matrix 1 This PDF file provides a sample literature review matrix.

- Literature Review Matrix 2 This PDF file provides a sample literature review matrix.

- Literature Review Matrix Template (Word)

- Literature Review Matrix Template (Excel)

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Commentary Versus Opinion

- Next Page: Professional Development Plans (PDPs)

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 26, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

1. Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

Find academic papers related to your research topic faster. Try Research on Paperpal

3. Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

4. Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

5. Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

6. Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

Strengthen your literature review with factual insights. Try Research on Paperpal for free!

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Write and Cite as you go with Paperpal Research. Start now for free.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

Whether you’re exploring a new research field or finding new angles to develop an existing topic, sifting through hundreds of papers can take more time than you have to spare. But what if you could find science-backed insights with verified citations in seconds? That’s the power of Paperpal’s new Research feature!

How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Paperpal, an AI writing assistant, integrates powerful academic search capabilities within its writing platform. With the Research feature, you get 100% factual insights, with citations backed by 250M+ verified research articles, directly within your writing interface with the option to save relevant references in your Citation Library. By eliminating the need to switch tabs to find answers to all your research questions, Paperpal saves time and helps you stay focused on your writing.

Here’s how to use the Research feature:

- Ask a question: Get started with a new document on paperpal.com. Click on the “Research” feature and type your question in plain English. Paperpal will scour over 250 million research articles, including conference papers and preprints, to provide you with accurate insights and citations.

- Review and Save: Paperpal summarizes the information, while citing sources and listing relevant reads. You can quickly scan the results to identify relevant references and save these directly to your built-in citations library for later access.

- Cite with Confidence: Paperpal makes it easy to incorporate relevant citations and references into your writing, ensuring your arguments are well-supported by credible sources. This translates to a polished, well-researched literature review.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a good literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses. By combining effortless research with an easy citation process, Paperpal Research streamlines the literature review process and empowers you to write faster and with more confidence. Try Paperpal Research now and see for yourself.

Frequently asked questions

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.

The literature review format can vary depending on the specific publication guidelines. However, there are some common elements and structures that are often followed. Here is a general guideline for the format of a literature review: Introduction: Provide an overview of the topic. Define the scope and purpose of the literature review. State the research question or objective. Body: Organize the literature by themes, concepts, or chronology. Critically analyze and evaluate each source. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. Highlight any methodological limitations or biases. Identify patterns, connections, or contradictions in the existing research. Conclusion: Summarize the key points discussed in the literature review. Highlight the research gap. Address the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Highlight the contributions of the review and suggest directions for future research.

Both annotated bibliographies and literature reviews involve the examination of scholarly sources. While annotated bibliographies focus on individual sources with brief annotations, literature reviews provide a more in-depth, integrated, and comprehensive analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. The key differences are as follows:

| Annotated Bibliography | Literature Review | |

| Purpose | List of citations of books, articles, and other sources with a brief description (annotation) of each source. | Comprehensive and critical analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. |

| Focus | Summary and evaluation of each source, including its relevance, methodology, and key findings. | Provides an overview of the current state of knowledge on a particular subject and identifies gaps, trends, and patterns in existing literature. |

| Structure | Each citation is followed by a concise paragraph (annotation) that describes the source’s content, methodology, and its contribution to the topic. | The literature review is organized thematically or chronologically and involves a synthesis of the findings from different sources to build a narrative or argument. |

| Length | Typically 100-200 words | Length of literature review ranges from a few pages to several chapters |

| Independence | Each source is treated separately, with less emphasis on synthesizing the information across sources. | The writer synthesizes information from multiple sources to present a cohesive overview of the topic. |

References

- Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of criminal justice education , 24 (2), 218-234.

- Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Taylor & Francis.

- Cantero, C. (2019). How to write a literature review. San José State University Writing Center .

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- How Long Should a Chapter Be?

- How to Use Paperpal to Generate Emails & Cover Letters?

6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how to avoid it, you may also like, academic integrity vs academic dishonesty: types & examples, dissertation printing and binding | types & comparison , what is a dissertation preface definition and examples , the ai revolution: authors’ role in upholding academic..., the future of academia: how ai tools are..., how to write a research proposal: (with examples..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide).

- Research Guides

- Vanderbilt University Libraries

- Peabody Library

Literature Reviews

Literature review table.

- Steps to Success: The Literature Review Process

- Literature Reviews Webinar Recording

- Writing Like an Academic

- Publishing in Academic Journals

- Managing Citations This link opens in a new window

- Literature Review Table Template Peabody Librarians have created a sample literature review table to use to organize your research. Feel free to download this file and use or adapt as needed.

- << Previous: Literature Reviews Webinar Recording

- Next: Writing Like an Academic >>

- Last Updated: Jul 12, 2024 12:55 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.vanderbilt.edu/peabody/litreviews

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Credit: Getty

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

WENTING ZHAO: Be focused and avoid jargon

Assistant professor of chemical and biomedical engineering, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

When I was a research student, review writing improved my understanding of the history of my field. I also learnt about unmet challenges in the field that triggered ideas.

For example, while writing my first review 1 as a PhD student, I was frustrated by how poorly we understood how cells actively sense, interact with and adapt to nanoparticles used in drug delivery. This experience motivated me to study how the surface properties of nanoparticles can be modified to enhance biological sensing. When I transitioned to my postdoctoral research, this question led me to discover the role of cell-membrane curvature, which led to publications and my current research focus. I wouldn’t have started in this area without writing that review.

Collection: Careers toolkit

A common problem for students writing their first reviews is being overly ambitious. When I wrote mine, I imagined producing a comprehensive summary of every single type of nanomaterial used in biological applications. It ended up becoming a colossal piece of work, with too many papers discussed and without a clear way to categorize them. We published the work in the end, but decided to limit the discussion strictly to nanoparticles for biological sensing, rather than covering how different nanomaterials are used in biology.

My advice to students is to accept that a review is unlike a textbook: it should offer a more focused discussion, and it’s OK to skip some topics so that you do not distract your readers. Students should also consider editorial deadlines, especially for invited reviews: make sure that the review’s scope is not so extensive that it delays the writing.

A good review should also avoid jargon and explain the basic concepts for someone who is new to the field. Although I trained as an engineer, I’m interested in biology, and my research is about developing nanomaterials to manipulate proteins at the cell membrane and how this can affect ageing and cancer. As an ‘outsider’, the reviews that I find most useful for these biological topics are those that speak to me in accessible scientific language.

Bozhi Tian likes to get a variety of perspectives into a review. Credit: Aleksander Prominski

BOZHI TIAN: Have a process and develop your style

Associate professor of chemistry, University of Chicago, Illinois.

In my lab, we start by asking: what is the purpose of this review? My reasons for writing one can include the chance to contribute insights to the scientific community and identify opportunities for my research. I also see review writing as a way to train early-career researchers in soft skills such as project management and leadership. This is especially true for lead authors, because they will learn to work with their co-authors to integrate the various sections into a piece with smooth transitions and no overlaps.

After we have identified the need and purpose of a review article, I will form a team from the researchers in my lab. I try to include students with different areas of expertise, because it is useful to get a variety of perspectives. For example, in the review ‘An atlas of nano-enabled neural interfaces’ 2 , we had authors with backgrounds in biophysics, neuroengineering, neurobiology and materials sciences focusing on different sections of the review.

After this, I will discuss an outline with my team. We go through multiple iterations to make sure that we have scanned the literature sufficiently and do not repeat discussions that have appeared in other reviews. It is also important that the outline is not decided by me alone: students often have fresh ideas that they can bring to the table. Once this is done, we proceed with the writing.

I often remind my students to imagine themselves as ‘artists of science’ and encourage them to develop how they write and present information. Adding more words isn’t always the best way: for example, I enjoy using tables to summarize research progress and suggest future research trajectories. I’ve also considered including short videos in our review papers to highlight key aspects of the work. I think this can increase readership and accessibility because these videos can be easily shared on social-media platforms.

ANKITA ANIRBAN: Timeliness and figures make a huge difference

Editor, Nature Reviews Physics .

One of my roles as a journal editor is to evaluate proposals for reviews. The best proposals are timely and clearly explain why readers should pay attention to the proposed topic.

It is not enough for a review to be a summary of the latest growth in the literature: the most interesting reviews instead provide a discussion about disagreements in the field.

Careers Collection: Publishing

Scientists often centre the story of their primary research papers around their figures — but when it comes to reviews, figures often take a secondary role. In my opinion, review figures are more important than most people think. One of my favourite review-style articles 3 presents a plot bringing together data from multiple research papers (many of which directly contradict each other). This is then used to identify broad trends and suggest underlying mechanisms that could explain all of the different conclusions.

An important role of a review article is to introduce researchers to a field. For this, schematic figures can be useful to illustrate the science being discussed, in much the same way as the first slide of a talk should. That is why, at Nature Reviews, we have in-house illustrators to assist authors. However, simplicity is key, and even without support from professional illustrators, researchers can still make use of many free drawing tools to enhance the value of their review figures.

Yoojin Choi recommends that researchers be open to critiques when writing reviews. Credit: Yoojin Choi

YOOJIN CHOI: Stay updated and be open to suggestions

Research assistant professor, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Daejeon.

I started writing the review ‘Biosynthesis of inorganic nanomaterials using microbial cells and bacteriophages’ 4 as a PhD student in 2018. It took me one year to write the first draft because I was working on the review alongside my PhD research and mostly on my own, with support from my adviser. It took a further year to complete the processes of peer review, revision and publication. During this time, many new papers and even competing reviews were published. To provide the most up-to-date and original review, I had to stay abreast of the literature. In my case, I made use of Google Scholar, which I set to send me daily updates of relevant literature based on key words.

Through my review-writing process, I also learnt to be more open to critiques to enhance the value and increase the readership of my work. Initially, my review was focused only on using microbial cells such as bacteria to produce nanomaterials, which was the subject of my PhD research. Bacteria such as these are known as biofactories: that is, organisms that produce biological material which can be modified to produce useful materials, such as magnetic nanoparticles for drug-delivery purposes.

Synchronized editing: the future of collaborative writing

However, when the first peer-review report came back, all three reviewers suggested expanding the review to cover another type of biofactory: bacteriophages. These are essentially viruses that infect bacteria, and they can also produce nanomaterials.

The feedback eventually led me to include a discussion of the differences between the various biofactories (bacteriophages, bacteria, fungi and microalgae) and their advantages and disadvantages. This turned out to be a great addition because it made the review more comprehensive.

Writing the review also led me to an idea about using nanomaterial-modified microorganisms to produce chemicals, which I’m still researching now.

PAULA MARTIN-GONZALEZ: Make good use of technology

PhD student, University of Cambridge, UK.

Just before the coronavirus lockdown, my PhD adviser and I decided to write a literature review discussing the integration of medical imaging with genomics to improve ovarian cancer management.

As I was researching the review, I noticed a trend in which some papers were consistently being cited by many other papers in the field. It was clear to me that those papers must be important, but as a new member of the field of integrated cancer biology, it was difficult to immediately find and read all of these ‘seminal papers’.

That was when I decided to code a small application to make my literature research more efficient. Using my code, users can enter a query, such as ‘ovarian cancer, computer tomography, radiomics’, and the application searches for all relevant literature archived in databases such as PubMed that feature these key words.

The code then identifies the relevant papers and creates a citation graph of all the references cited in the results of the search. The software highlights papers that have many citation relationships with other papers in the search, and could therefore be called seminal papers.

My code has substantially improved how I organize papers and has informed me of key publications and discoveries in my research field: something that would have taken more time and experience in the field otherwise. After I shared my code on GitHub, I received feedback that it can be daunting for researchers who are not used to coding. Consequently, I am hoping to build a more user-friendly interface in a form of a web page, akin to PubMed or Google Scholar, where users can simply input their queries to generate citation graphs.

Tools and techniques

Most reference managers on the market offer similar capabilities when it comes to providing a Microsoft Word plug-in and producing different citation styles. But depending on your working preferences, some might be more suitable than others.

Reference managers

Attribute | EndNote | Mendeley | Zotero | Paperpile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Cost | A one-time cost of around US$340 but comes with discounts for academics; around $150 for students | Free version available | Free version available | Low and comes with academic discounts |

Level of user support | Extensive user tutorials available; dedicated help desk | Extensive user tutorials available; global network of 5,000 volunteers to advise users | Forum discussions to troubleshoot | Forum discussions to troubleshoot |

Desktop version available for offline use? | Available | Available | Available | Unavailable |

Document storage on cloud | Up to 2 GB (free version) | Up to 2 GB (free version) | Up to 300 MB (free version) | Storage linked to Google Drive |

Compatible with Google Docs? | No | No | Yes | Yes |

Supports collaborative working? | No group working | References can be shared or edited by a maximum of three other users (or more in the paid-for version) | No limit on the number of users | No limit on the number of users |

Here is a comparison of the more popular collaborative writing tools, but there are other options, including Fidus Writer, Manuscript.io, Authorea and Stencila.

Collaborative writing tools

Attribute | Manubot | Overleaf | Google Docs |

|---|---|---|---|

Cost | Free, open source | $15–30 per month, comes with academic discounts | Free, comes with a Google account |

Writing language | Type and write in Markdown* | Type and format in LaTex* | Standard word processor |

Can be used with a mobile device? | No | No | Yes |

References | Bibliographies are built using DOIs, circumventing reference managers | Citation styles can be imported from reference managers | Possible but requires additional referencing tools in a plug-in, such as Paperpile |

*Markdown and LaTex are code-based formatting languages favoured by physicists, mathematicians and computer scientists who code on a regular basis, and less popular in other disciplines such as biology and chemistry.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

How to harness AI’s potential in research — responsibly and ethically

Career Feature 23 AUG 24

Partners in drug discovery: how to collaborate with non-governmental organizations

Time to refocus for South Korean science

Nature Index 21 AUG 24

South Korean science on the global stage

How South Korea can build better gender diversity into research

The citation black market: schemes selling fake references alarm scientists

News 20 AUG 24

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer at the Dyson School of Design Engineering

About the role: Do you want to change the world for the better, and do you believe this can be done through research and education? If so, grab you...

South Kensington, London (Greater) (GB)

Imperial College London (ICL)

Faculty Positions in Westlake University

Founded in 2018, Westlake University is a new type of non-profit research-oriented university in Hangzhou, China, supported by public a...

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Westlake University

Call for Global Talents, Recruitment Information of Nankai University

Nankai University welcomes global outstanding talents to join for common development.

Tianjin, China

Nankai University

Director for Signature Research Programme in Cancer and Stem Cell Biology, DukeNUS Medical School &

The successful candidate will demonstrate their ability of growing, leading and mentoring faculty as well as developing and operationalising strategy.

Singapore (SG)

DukeNUS Medical School

Scientist / Postdoc (m/f/d): Analysis of Microscopic BIOMedical Images (AMBIOM)

A new project area in the institute is the development of artificial intelligence (AI)

Dortmund, Nordrhein-Westfalen (DE)

Leibniz-Institut für Analytische Wissenschaften – ISAS – e.V.

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Reference management. Clean and simple.

What is a literature review? [with examples]

What is a literature review?

The purpose of a literature review, how to write a literature review, the format of a literature review, general formatting rules, the length of a literature review, literature review examples, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, related articles.

A literature review is an assessment of the sources in a chosen topic of research.

In a literature review, you’re expected to report on the existing scholarly conversation, without adding new contributions.

If you are currently writing one, you've come to the right place. In the following paragraphs, we will explain:

- the objective of a literature review

- how to write a literature review

- the basic format of a literature review

Tip: It’s not always mandatory to add a literature review in a paper. Theses and dissertations often include them, whereas research papers may not. Make sure to consult with your instructor for exact requirements.

The four main objectives of a literature review are:

- Studying the references of your research area

- Summarizing the main arguments

- Identifying current gaps, stances, and issues

- Presenting all of the above in a text

Ultimately, the main goal of a literature review is to provide the researcher with sufficient knowledge about the topic in question so that they can eventually make an intervention.

The format of a literature review is fairly standard. It includes an:

- introduction that briefly introduces the main topic

- body that includes the main discussion of the key arguments

- conclusion that highlights the gaps and issues of the literature

➡️ Take a look at our guide on how to write a literature review to learn more about how to structure a literature review.

First of all, a literature review should have its own labeled section. You should indicate clearly in the table of contents where the literature can be found, and you should label this section as “Literature Review.”

➡️ For more information on writing a thesis, visit our guide on how to structure a thesis .

There is no set amount of words for a literature review, so the length depends on the research. If you are working with a large amount of sources, it will be long. If your paper does not depend entirely on references, it will be short.

Take a look at these three theses featuring great literature reviews:

- School-Based Speech-Language Pathologist's Perceptions of Sensory Food Aversions in Children [ PDF , see page 20]

- Who's Writing What We Read: Authorship in Criminological Research [ PDF , see page 4]

- A Phenomenological Study of the Lived Experience of Online Instructors of Theological Reflection at Christian Institutions Accredited by the Association of Theological Schools [ PDF , see page 56]

Literature reviews are most commonly found in theses and dissertations. However, you find them in research papers as well.

There is no set amount of words for a literature review, so the length depends on the research. If you are working with a large amount of sources, then it will be long. If your paper does not depend entirely on references, then it will be short.

No. A literature review should have its own independent section. You should indicate clearly in the table of contents where the literature review can be found, and label this section as “Literature Review.”

The main goal of a literature review is to provide the researcher with sufficient knowledge about the topic in question so that they can eventually make an intervention.

How To Structure Your Literature Review

3 options to help structure your chapter.

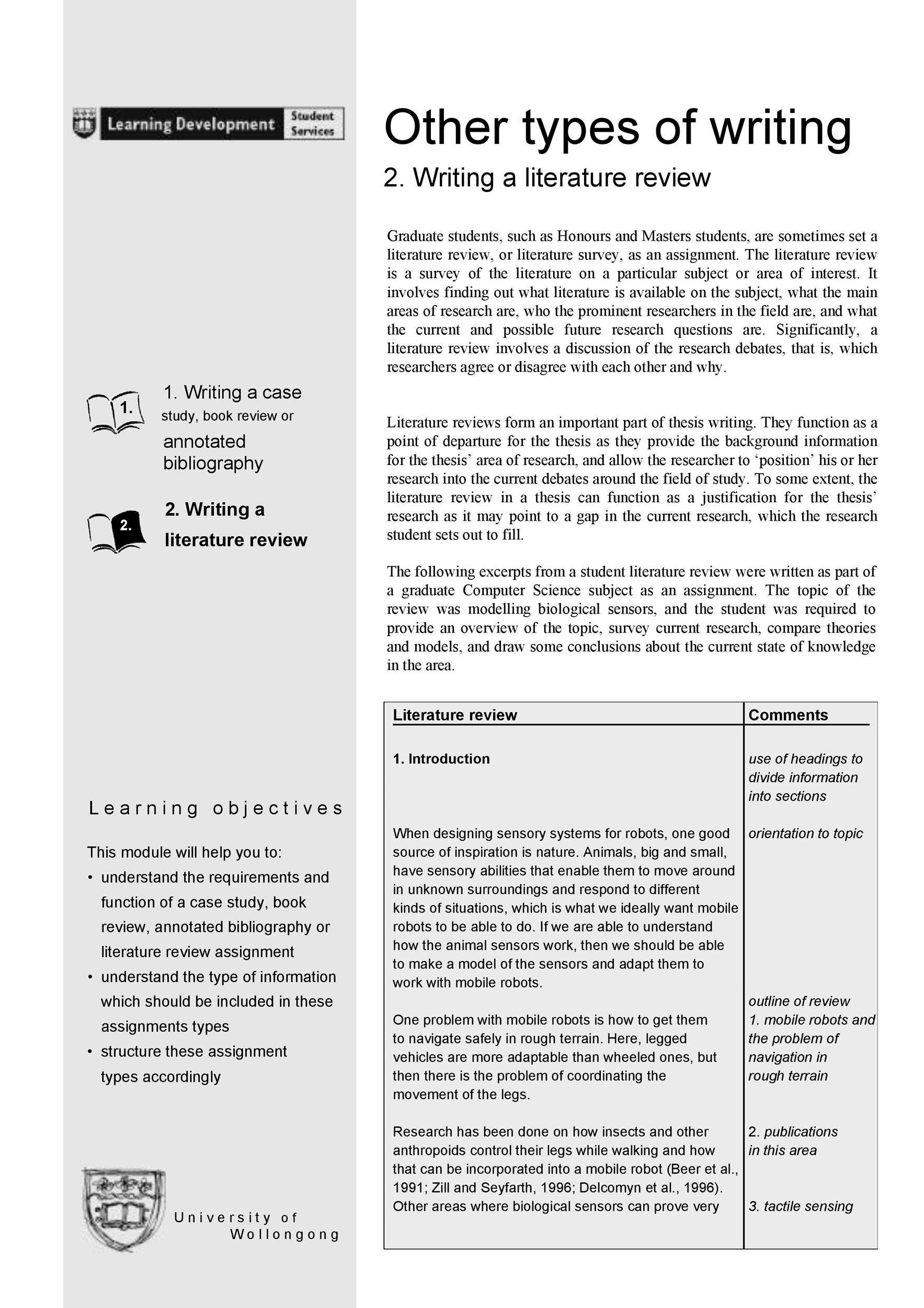

By: Amy Rommelspacher (PhD) | Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | November 2020 (Updated May 2023)

Writing the literature review chapter can seem pretty daunting when you’re piecing together your dissertation or thesis. As we’ve discussed before , a good literature review needs to achieve a few very important objectives – it should:

- Demonstrate your knowledge of the research topic

- Identify the gaps in the literature and show how your research links to these

- Provide the foundation for your conceptual framework (if you have one)

- Inform your own methodology and research design

To achieve this, your literature review needs a well-thought-out structure . Get the structure of your literature review chapter wrong and you’ll struggle to achieve these objectives. Don’t worry though – in this post, we’ll look at how to structure your literature review for maximum impact (and marks!).

But wait – is this the right time?

Deciding on the structure of your literature review should come towards the end of the literature review process – after you have collected and digested the literature, but before you start writing the chapter.

In other words, you need to first develop a rich understanding of the literature before you even attempt to map out a structure. There’s no use trying to develop a structure before you’ve fully wrapped your head around the existing research.

Equally importantly, you need to have a structure in place before you start writing , or your literature review will most likely end up a rambling, disjointed mess.

Importantly, don’t feel that once you’ve defined a structure you can’t iterate on it. It’s perfectly natural to adjust as you engage in the writing process. As we’ve discussed before , writing is a way of developing your thinking, so it’s quite common for your thinking to change – and therefore, for your chapter structure to change – as you write.

Need a helping hand?

Like any other chapter in your thesis or dissertation, your literature review needs to have a clear, logical structure. At a minimum, it should have three essential components – an introduction , a body and a conclusion .

Let’s take a closer look at each of these.

1: The Introduction Section

Just like any good introduction, the introduction section of your literature review should introduce the purpose and layout (organisation) of the chapter. In other words, your introduction needs to give the reader a taste of what’s to come, and how you’re going to lay that out. Essentially, you should provide the reader with a high-level roadmap of your chapter to give them a taste of the journey that lies ahead.

Here’s an example of the layout visualised in a literature review introduction:

Your introduction should also outline your topic (including any tricky terminology or jargon) and provide an explanation of the scope of your literature review – in other words, what you will and won’t be covering (the delimitations ). This helps ringfence your review and achieve a clear focus . The clearer and narrower your focus, the deeper you can dive into the topic (which is typically where the magic lies).

Depending on the nature of your project, you could also present your stance or point of view at this stage. In other words, after grappling with the literature you’ll have an opinion about what the trends and concerns are in the field as well as what’s lacking. The introduction section can then present these ideas so that it is clear to examiners that you’re aware of how your research connects with existing knowledge .

2: The Body Section

The body of your literature review is the centre of your work. This is where you’ll present, analyse, evaluate and synthesise the existing research. In other words, this is where you’re going to earn (or lose) the most marks. Therefore, it’s important to carefully think about how you will organise your discussion to present it in a clear way.

The body of your literature review should do just as the description of this chapter suggests. It should “review” the literature – in other words, identify, analyse, and synthesise it. So, when thinking about structuring your literature review, you need to think about which structural approach will provide the best “review” for your specific type of research and objectives (we’ll get to this shortly).

There are (broadly speaking) three options for organising your literature review.

Option 1: Chronological (according to date)

Organising the literature chronologically is one of the simplest ways to structure your literature review. You start with what was published first and work your way through the literature until you reach the work published most recently. Pretty straightforward.

The benefit of this option is that it makes it easy to discuss the developments and debates in the field as they emerged over time. Organising your literature chronologically also allows you to highlight how specific articles or pieces of work might have changed the course of the field – in other words, which research has had the most impact . Therefore, this approach is very useful when your research is aimed at understanding how the topic has unfolded over time and is often used by scholars in the field of history. That said, this approach can be utilised by anyone that wants to explore change over time .

For example , if a student of politics is investigating how the understanding of democracy has evolved over time, they could use the chronological approach to provide a narrative that demonstrates how this understanding has changed through the ages.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself to help you structure your literature review chronologically.

- What is the earliest literature published relating to this topic?

- How has the field changed over time? Why?

- What are the most recent discoveries/theories?