Select a year to see courses

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

- OC Test Preparation

- Selective School Test Preparation

- Maths Acceleration

- English Advanced

- Maths Standard

- Maths Advanced

- Maths Extension 1

- English Standard

- Maths Extension 2

Get HSC exam ready in just a week

- UCAT Exam Preparation

Select a year to see available courses

- English Units 1/2

- Maths Methods Units 1/2

- Biology Units 1/2

- Chemistry Units 1/2

- Physics Units 1/2

- English Units 3/4

- Maths Methods Units 3/4

- Biology Unit 3/4

- Chemistry Unit 3/4

- Physics Unit 3/4

- UCAT Preparation Course

- Matrix Learning Methods

- Matrix Term Courses

- Matrix Holiday Courses

- Matrix+ Online Courses

- Campus overview

- Castle Hill

- Strathfield

- Sydney City

- Year 3 NAPLAN Guide

- OC Test Guide

- Selective Schools Guide

- NSW Primary School Rankings

- NSW High School Rankings

- NSW High Schools Guide

- ATAR & Scaling Guide

- HSC Study Planning Kit

- Student Success Secrets

- Reading List

- Year 6 English

- Year 7 & 8 English

- Year 9 English

- Year 10 English

- Year 11 English Standard

- Year 11 English Advanced

- Year 12 English Standard

Year 12 English Advanced

- HSC English Skills

- How To Write An Essay

- How to Analyse Poetry

- English Techniques Toolkit

- Year 7 Maths

- Year 8 Maths

- Year 9 Maths

- Year 10 Maths

- Year 11 Maths Advanced

- Year 11 Maths Extension 1

- Year 12 Maths Standard 2

- Year 12 Maths Advanced

- Year 12 Maths Extension 1

- Year 12 Maths Extension 2

Science guides to help you get ahead

- Year 11 Biology

- Year 11 Chemistry

- Year 11 Physics

- Year 12 Biology

- Year 12 Chemistry

- Year 12 Physics

- Physics Practical Skills

- Periodic Table

- VIC School Rankings

- VCE English Study Guide

- Set Location

Welcome to Matrix Education

To ensure we are showing you the most relevant content, please select your location below.

How To Write A Band 6 Module C Discursive Essay (New Syllabus)

The discursive essay is a new component of Module C: The Craft of Writing. In this article, we explain what a discursive essay is and give you a step-by-step process for writing one.

Guide Chapters

- How to write a Band 6 Discursive

- Exemplar discursive and reflection

- Exemplar Band 6 Discursive Essay

- Top 6 Student Struggles

Get free study tips and resources delivered to your inbox.

Join 75,893 students who already have a head start.

" * " indicates required fields

You might also like

- Part 2: How To Analyse ‘Othello’ For The Year 11 Modules | Year 11 English

- Reflecting on the 2016 HSC Year

- Literary Techniques: Repetition

- How To Write A Comparative Essay On Mrs Dalloway And The Hours | Free Exemplar Essay

- Tips for Collaborative Study Before the HSC

Related courses

Vce english units 3 & 4.

Do you know what a discursive essay is? Do you know what makes it different from a persuasive essay? What does “discursive” even mean? If these questions have ever crossed, you’re not alone. But don’t worry! In this post, we’ll explain what a discursive essay is and how to write one worthy of a Band 6.

In this article, we discuss:

What’s a discursive essay.

- Why write Discursive essays?

- What’s different about writing discursive essays?

- How to plan a discursive essay

- How to write a discursive essay, step-by-step

Download your free discursive essay cheatsheet!

Write the perfect discursive response with flair

Done! Your download has been emailed.

Please allow a few minutes for it to land in your inbox.

We take your privacy seriously. T&Cs and Privacy Policy .

A discursive essay is a type of writing that explores multiple perspectives on a topic.

NESA defines discursive texts as:

Texts whose primary focus is to explore an idea or variety of topics. These texts involve the discussion of an idea(s) or opinion(s) without the direct intention of persuading the reader, listener or viewer to adopt any single point of view. Discursive texts can be humorous or serious in tone and can have a formal or informal register.

NESA adds that discursive essays can also include the following features:

- Explores an issue or an idea and may suggest a position or point of view

- Approaches a topic from different angles and explores themes and issues in a style that balances personal observations with different perspectives

- Uses personal anecdotes and may have a conversational tone

- Primarily uses first person although third person can also be used

- Uses figurative language or may be more factual

- Draws upon real-life experiences and/or draws from wide reading

- Uses engaging imagery and language features

- Begins with an event, an anecdote or a relevant quote that is then used to explore an idea

- Resolution may be reflective or open-ended

When you write discursive essays, you will need to discuss ideas in this way.

But, don’t worry—it’s a lot more fun than it sounds. Let’s see why.

Why do I need to learn how to write “discursive essays”?

The 2019 HSC English Syllabus made significant changes to Module C.

Instead of just analysing texts, the new Module C: The Craft of Writing focuses on improving your writing skills.

To do this, the Module requires you to write in a variety of different modes:

- Imaginative : Imaginative writing is creative writing. For example, a short story or creative reimagining.

- Persuasive : Persuasive writing persuades somebody of an idea or position. Most of the essays you produce for high school are persuasive essays.

- Informative : Informative writing tries to inform people of facts and data. This may mean a report, but it could also include types of writing such as popular science or travel writing.

- Discursive : Discursive writing explores an idea from several perspectives. It can be humorous or serious in tone.

NESA aims to make you a more confident and competent communicator, broadening your writing skills so they’re practical even beyond high school and the HSC.

What’s different about writing a discursive essay?

There are stylistic and structural differences between a discursive and a persuasive essay.

Most essays that you write in high school ask you to take a position on something and argue for it. Essentially, you’re being asked to persuade a reader of something; a theme, idea, or an idea’s connection to context.

In contrast, discursive essays don’t require you to take a particular position on something.

When you write a discursive essay, you can explore your topic from a few different perspectives. This gives you the opportunity to highlight the pros and cons, and see what others might think about the topic.

Discursive essays are also less rigid and formal than the standard persuasive essay you’re asked to write in other Modules. In a discursive essay, you can develop your own voice and style.

The following table shows the differences in forms:

Struggling with writing a discursive essay?

Learn how to research, structure, and write a discursive essay with expert step-by-step guidance and feedback!

Start HSC English confidently

Expert teachers, detailed feedback, one-to-one help! Learn from home with Matrix+ Online English courses.

So, does my opinion count?

When you’re writing an essay, your opinion always counts. Whether you’re writing a detailed persuasive essay for Module B or a discursive piece for a Module C assessment, your ideas and opinions are crucial.

The difference is how you present them. When you write a persuasive essay, there is the assumption that it is your voice and your opinion. So, teachers often say not to use personal pronouns because adding a stronger element of your personal voice will make your writing seem too subjective and, therefore, not as persuasive.

Personal pronouns in persuasive essays are also often seen as being tautological (saying something twice, which some see as a stylistic fault).

In contrast, in a discursive essay, you can take a more personal approach. For example, including personal anecdotes and your own strong voice can help add depth and insight to the perspectives you discuss.

What style should I take in a discursive essay?

Discursive essays are stylistically flexible compared to persuasive essays. They can be serious or they can be humorous.

They’re not a new style of writing – discursive essays were a very common form of writing during the Renaissance and Early Modern Period.

Mary Wollstonecraft, Charles Lamb, Elizabeth Barret Browning, Samuel Johnson, GK Chesterton, and Michel de Montaigne were all famous essayists in their time who wrote discursive texts as well as persuasive ones.

Over time, the discursive essay became less common than the persuasive essay. In our context, discursive writing is becoming more common again. Contemporary writers such as Zadie Smith, Helen Garner, John D’Agata, and Ta-Nesi Coates all have discursive essays among their work.

You’ll find examples of discursive writing in publications like:

- The Atlantic

- The New Yorker

- The Economist

- The Guardian

- Time Magazine

- Mother Jones

Do I need to analyse evidence in a discursive essay?

You’ll need to provide evidence in your discursive essays, but not in the same sense as your persuasive writing.

The idea is to explore ideas or a variety of topics and to do this, you’ll have to present some evidence. But this won’t necessarily include literary analysis (although it might if you so choose).

You’re not writing T.E.E.L or P.E.E.L paragraphs or listing techniques and effects (not that you should ever simply list techniques and effects!).

Instead, you’ll be writing about ideas and maybe supporting these with quotations from other people, or anecdotes and reflections from your personal experience.

What structure should a discursive essay have?

In persuasive essays, you’ll use strict essay structures depending on whether you’re discussing one or more texts and the Module you’re studying. Your paragraphs should be consistent in length and have explicit signposting, such as topic sentences and linking sentences.

Discursive essays don’t have the same rigid structure or approach to signposting.

In a discursive essay, you may not be discussing texts, but rather ideas or things – for instance, an advertisement, political system, or a type of sneaker. This means that some paragraphs will need to be longer than others, depending on the idea you’re discussing.

In addition, because a discursive essay will want you to discuss things from an objective point of view, but also include your anecdotal experiences, you may find that your anecdotes are shorter than your discussion of ideas.

While you will need to introduce your ideas in the introduction and at the start of each paragraph, you won’t need to have formal thesis statements and topic sentences. After all, you’re trying to be more conversational and less formal.

How do I plan and write a discursive essay?

Like any essay, you can follow a process to produce high-quality essays and make your life easier.

Let’s take a look at the steps Matrix students use.

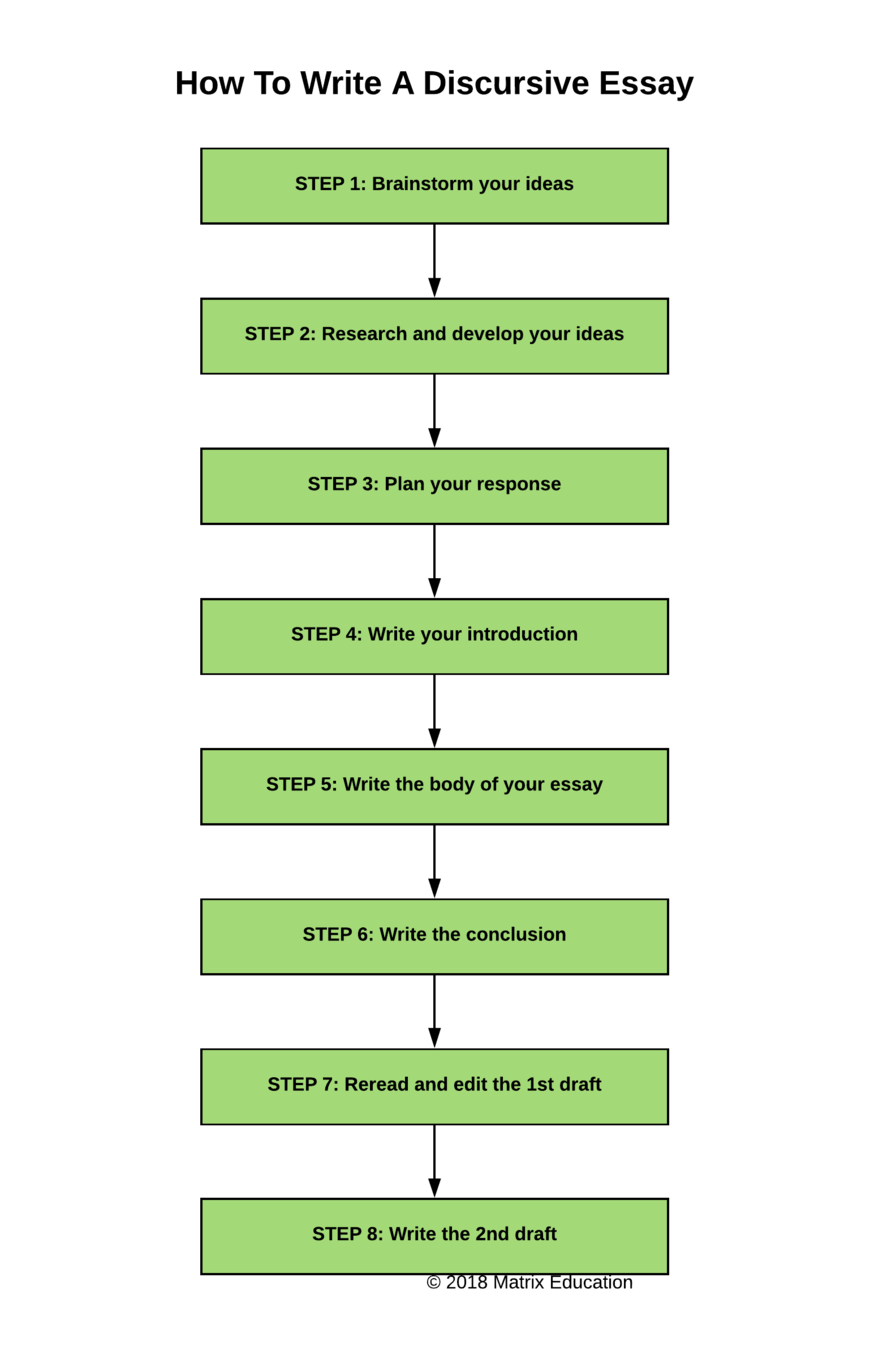

Writing a discursive essay, step-by-step

Now we’ll explore in-depth how to write a discursive essay. This process has the following steps:

- Brainstorm your ideas

- Research and develop your ideas

- Plan your response

- Begin writing your introduction

- Write the body of your discussion

- Finish by writing a conclusion

- Reread and proofread your first draft

- Write a second draft based on your notes and edits

- Third draft and submit

When you write a persuasive essay, you are given a specific question. With a discursive essay, you may not have a question at all. Instead, your discursive tasks might come in different forms:

- A question : You are given a question and asked to answer it by discussing a topic or a variety of topics.

- A topic : You are given a topic to explore.

- A stimulus : You are given either a statement or image and must use that as the basis for your writing.

Because of the nature of discursive essays, you won’t be analysing and unpacking a question like you would for a persuasive essay. Instead, you’ll need to research and explore different ideas or subjects.

As with any essay, you must take the time to research and plan your work first. This is especially true if you are writing on a topic for the first time.

Step 1: Brainstorm your ideas

Before you start anything, you need to consider what you know about the topic.

Your first step is to create a mind map that lists what you know about the topic. Mind maps should list the aspects of the topic that you think are worth exploring.

Step 2: Research and develop your ideas

Now that you’ve brainstormed ideas, it’s time to develop your ideas through research.

Fortunately, you have the power of the internet at your fingers. With your mind map as a guide, start researching the topics you’ve listed.

YouTube is a good place to start looking for basic information about subjects.

Make sure you try to use reputable sites. For example, a personal blog is not going to have the same level of trustworthiness as major news or academic websites.

Start by looking at the broad topic you find interesting, and then pick two or three aspects to consider in detail.

Don’t let your research get too out of hand. Keep your focus narrow enough to manage the word count (1000-1200 words), but wide enough to explore different viewpoints.

Some dos and don’ts:

- Do – Follow the ideas that interest you

- Don’t – Research too many different ideas

- Do – Research different perspectives on your topic

- Don’t – Settle for just one source

- Do – Make note of useful sources, examples, and quotations for your response

- Don’t – Skip out on doing research

Once you’ve researched your topic, you’re ready to start planning your essay.

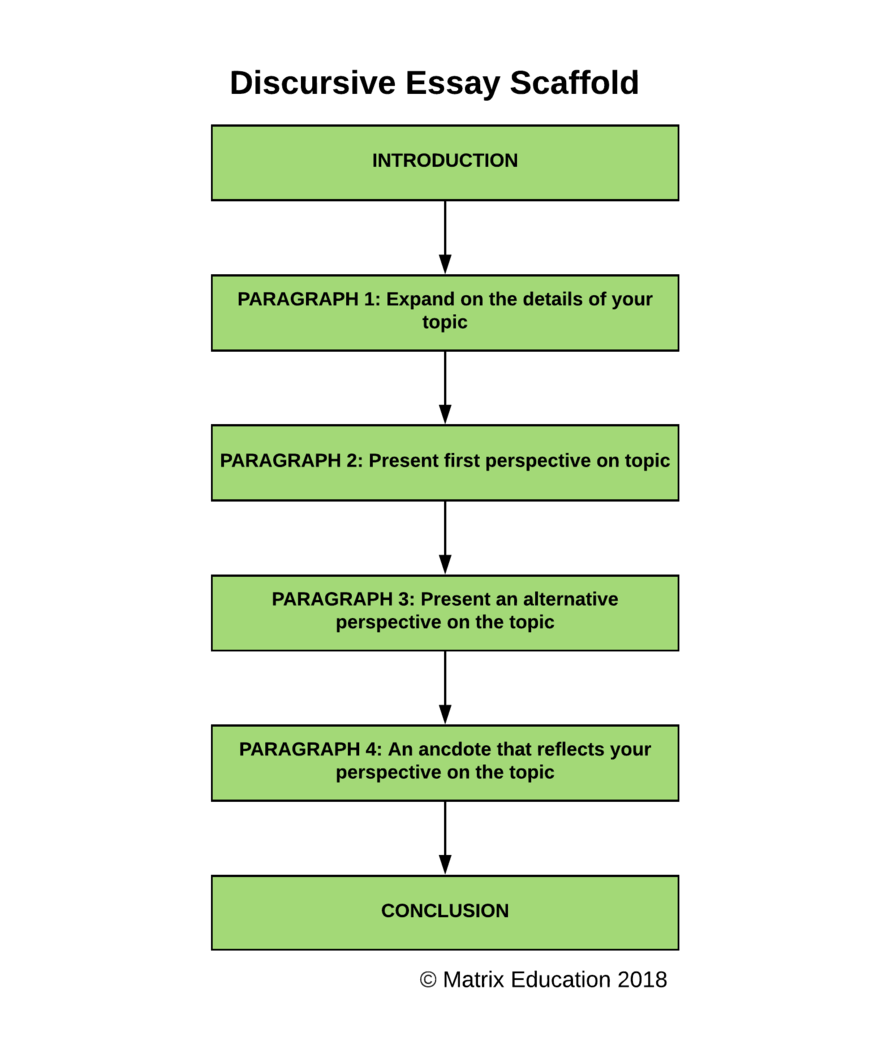

Step 3: Plan your response

Even though a discursive essay lacks the formality of a persuasive response, you still need a logical structure.

This means you’ll need:

- An introduction that orients your reader

- A body with several paragraphs that explore your topic

- A conclusion that summarises your discussion

Planning is important because it will help you structure your introduction and develop your ideas. Your introduction should briefly introduce the topic and why you’re going to talk about it.

When you plan, note down your ideas and think about how to best present them so the reader can easily follow. This means planning what you will discuss in each paragraph and what bits of evidence are going to best assist this.

Here’s a possible 4-part structure for the body of your essay :

- Introduce the topic or subject, expanding on your introduction

- Present one perspective on the issue

- Explore a different perspective

- Include a personal anecdote about the topic

Remember, this scaffold isn’t rigid. You could quite easily switch around where you put your anecdote. Or, rather than exploring different perspectives in different paragraphs, you may want to contrast these views in the same paragraph. In a discursive essay, you have flexibility.

Now you’ve planned everything, you’re set to start writing.

Don’t feel ready to write yet? Do you need to see an exemplary discursive essay to see what you should be doing?

Read a sample response, here .

Step 4: Write your introduction

The introduction of a discursive responsive is different to other essays in that you don’t have a formal thesis statement and thematic framework.

Instead, you can ask questions to introduce the topic or use an anecdote to frame the topic. You also don’t need to lay out a roadmap of how your essay will unfold, so you can spend time explaining your interest in the topic .

Some effective ways to start discursive essays are:

- Ask a question – Questions force your audiences to consider what they know about a subject.

- Use an anecdote – Personal experience can create reliability with the reader because they can see how another human engages with an idea.

- An example – Examples allow readers to develop a clear understanding of what the subject is and how they feel about it.

The length of your introduction can vary. As you’re not trying to explain the structure of your argument, you can focus on introducing the topic in the manner you find most engaging.

Step 5: Write the body of your discussion

This is where your planning comes in handy. When you’re writing the body of your discursive response, you want to think about the order of information your reader needs to make sense of your discussion. So, use your planning notes to structure your body paragraphs.

While you don’t need a topic sentence per se , you need to get to the subject of the paragraph within the first couple of sentences. You can vary the length of your paragraphs to suit the amount of material you want to discuss.

Some useful rules for writing your paragraphs:

- Use clear and direct language – avoid the passive form

- Employ a conversational and accessible tone

- Use language suited to an educated audience

- Vary your sentence length

- Support your points with examples and quotations about your topic

- Employ rhetorical techniques and literary devices to convey your ideas ( check out our Essential Guide to English Techniques if you need inspiration )

- Use anecdotes to connect with your audience

- Include pop culture and intertextual references that will help your reader follow your ideas

- “You” to refer to the reader or people in general

- “I” to introduce your perspectives and experiences

- When finishing one paragraph and moving to another, orient the reader. For example, “While that one perspective, that’s not the only perspective.”

Step 6: Write a conclusion

Your conclusion should summarise and tie things together.

You don’t need to follow the rigid formula of :

- Restate thesis

- Reiterate themes

- Make a statement about your experience of studying the Module

Instead, you need to tie together the various perspectives that you’ve looked at in your essay.

Remember, the point of a discursive essay is to explore a subject from different perspectives (and not persuade a single perspective).

Because of this, you want to take your reader back through the different perspectives you’ve encountered. Perhaps you might present the perspective on a matter you hold – for example, “Yes, I do prefer dark chocolate to white chocolate, but that doesn’t mean that white chocolate is not without its uses, benefits, or zealots.”

Once you’ve finished your conclusion…

Congratulations!

You’ve finished your first draft. Now you’re ready to proofread and edit it to produce a second draft.

Step 7: Reread and edit your first draft

Once you’ve completed your first draft, put it aside for a couple of hours or a day before you reread and edit it. This way, you can look at it with “fresh eyes”, allowing you to be a bit more objective when proofing your first draft.

Ideally, you want to print out your first draft, so you can annotate it as you go. But that is not always convenient and it’s certainly not environmentally friendly. Using track changes on a Word, Pages, or Google Doc will also work.

No matter your method, you’ll want to keep track of your changes and, perhaps, demonstrate to your teachers that you’ve employed an editing process.

To proofread and edit your response:

- Reread the essay.

- Underline any sentences that don’t make sense.

- Circle any pieces of grammar that are incorrect.

- Check for proper comma and apostrophe usage.

- Think about the order of the information you’ve presented. Ask yourself, “Does this make sense? Is this logical?” Don’t be afraid to make dramatic changes and consider rearranging the paragraphs or ideas in your response.

- Consider whether you find your essay convincing. Ask yourself, “Do I present ideas in a manner that shows my expertise and insight?”

- Think about how you could improve your writing by including a figurative device or rhetorical technique.

- Make notes about what you think is effective in your writing.

- Make notes about what you think could be more effective or insightful about your response.

Be objective about your writing.

Often, it’s hard to separate ourselves and our feelings from the things that we produce.

This can make it difficult to give an honest judgement of what works and what doesn’t. Do your best to be as objective and critical about your work as you can.

Once you’ve finished proofing and editing your work you’re ready to use these notes and edits to write your second draft.

Step 8: Write a second draft based on your notes and edits

You should write a second draft from the beginning rather than editing an existing document.

Rewriting sounds like a lot of work, doesn’t it? But it’ll be worth it.

Rewriting drafts from scratch will always improve the quality of the writing. Because you’re not simply working with sentences already on a page but, rather, rewriting them, you will be more inclined to change them and make them better.

What do I mean?

Do you ever look at a sentence in a Word document that you’re editing and say to yourself, “I know I should change that sentence, but I really like it so I’m going to make it work?”

A lot of people do, but it’s a bad habit to get into.

Rewriting your second draft from a blank page will make you less inclined to hang onto sentences that may seem nice to you, but aren’t great at conveying your ideas. In addition, rewriting your essay will make it easier to include new rhetorical devices and literary techniques, rearrange things, and make large structural changes.

Don’t hesitate to use the drafting process as a way to experiment with your writing and make it better.

Step 9: Third draft and submission

What do I do once I’ve got a second draft of my discursive essay?

If you must, you can submit your second draft. Ideally, though, you should try and get a second opinion.

How should you do this?

Maybe you can run it by a friend or family member. Matrix students get feedback from their teachers and workshop tutors to help them develop their drafts. If you approach your schoolteacher politely, they might give you some feedback if the task allows for it.

The drafting process doesn’t have to finish with the 3rd or, even, the fourth draft. You should keep refining your work to make sure it is as good as it can possibly be. Band 6 results don’t just miraculously appear, they are developed over time.

Once you have a draft you’re happy with, you’re to SUBMIT!

Want to improve your HSC English skills further?

From the comfort of your own home, access our expert-led video lessons, detailed Theory Books, and countless practice questions to help you succeed in your HSC. Enrol today!

Written by Matrix English Team

© Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Year 12 English Advanced tutoring at Matrix will help you gain strong reading and writing skills for the HSC.

Learning methods available

Year 12 English tutoring at Matrix will help your child improve their reading and writing skills.

Related articles

Megan’s High School Hacks: How I Bought Back Time With Extracurriculars And Hobbies

In this article, Matrix Scholarship holder and North Sydney Girls High School Student, Megan, shares how she bought back time with extracurriculars and hobbies. Read on to see how the challenge of doing more leads to more time for you.

Year 9 & 10 (Stage 5) Recommended Reading List

Recommended reading for students in Year 9 & 10 to improve their English skills.

Shahrin’s Hacks: Achieving A 93/100 For HSC English Advanced

In this post, Shahrin shares her secrets for nailing English Advanced for the HSC.

How to Write an HSC English Discursive Writing Piece

Expert reviewed • 22 November 2024 • 15 minute read

Understanding the Discursive Format

A discursive writing piece is a type of text that explores various sides of an argument or issue without the direct intention of persuading the reader to adopt a single point of view. The goal is to present a well-rounded discussion of the topic from multiple perspectives, allowing the reader to consider the complexities of the issue. This often involves presenting arguments both for and against a particular issue (whether explicitly or implicitly) giving the reader a comprehensive understanding of the subject.

Discursive texts are not restricted to an overly formal treatment of perspectives! — discursive texts can be humorous or serious in tone, and can have a formal or informal register. This flexibility allows writers to approach their topics in engaging and creative ways while still maintaining a focus on exploring a balanced view of the chosen subject matter.

Moreover, discursive writing can be hybridized with imaginative writing techniques (Check out this article ) to enhance the discussion of a topic from multiple angles. By incorporating imaginative elements, the discursive text can be made more engaging and thought-provoking.

How to Write a Discursive Text

The exam will give you a stimulus in some form from which you should base your piece on; From the provided quote, statement, extract or image, there are often many different central ideas you can extract to form the basis of your discursive piece. Start by finding a central idea and then consider the different perspectives you could represent in an engaging way.

If you ever find yourself stuck for ideas, keep trying to explore what the stimulus itself represents or could allude to, and keep branching out ideas from this.

The Structure of a Discursive Piece

- The opening should capture the attention of the reader while introducing the central issue either explicitly or implicitly.

- The body paragraphs should explore the topic in detail through exploring both sides or perspectives of the issue/topic.

- The conclusion should encapsulate the issue and perspectives without giving a judgement on either perspective (Remember, the point of a discursive is not to persuade, but to objectively explore multiple perspectives!), the conclusion should be both reflective and thought-provoking.

NOTE: Always remember to title the text you have created!

How to Structure the Body Paragraphs

The discursive piece does not have to be overly formal in structure, this allows leeway in the potential structure of your piece. A common way of structuring the essay is to have two body paragraphs for each perspective of an issue with one proposing the arguments for a case and one explaining the counter arguments, sequentially.

- Introduction : Present the topic and acknowledge the existence of different perspectives without personal judgement.

- Body 1 & 2 : Present arguments in favour of one perspective and then acknowledge counter-arguments.

- Body 3 & 4 : Present arguments in favour of the other perspective and then acknowledge counter-arguments.

- Conclusion : Summarise and reflect on the main arguments, bring up any thought-provoking realisations.

NOTE: Examples are below!

Practice Question 1

Try to write an opening to your own discursive-imaginative text for any subject matter of your choosing. A Band 6 sample opening is shown for reference.

I stand here, amidst the cosmic expanse of this checkered-board; a humble ebony piece, bound to the whims of my king. My brothers and sisters, who are forced to fall and rise, accept the peculiarities of our social environment…as if they were - natural. Why must this be the norm? Locked in a cosmic battle; sometimes victorious; other times - not. How might I transcend the shackles of imprisonment and ascend to the freedoms of reality?

This sample opening immediately captures the readers attention through imaginative techniques, a setting and some notion of characters are established, the use of the ellipsis (…) represents a hesitance revealing the character’s disdain for the philosophy subscribed to by the other characters (Metaphorically chess pieces). This opening reveals somewhat implicitly the fundamental issue of the struggle between freedom and captivity through a dichotomy of opposing philosophies.

This is a highly imaginative interpretation of discursive writing; Conveying the central issue to be explored through establishing metaphorical characters is a valid way of tackling a discursive piece. From this opening, the motif of a chessboard can be used throughout the text to argue both for the perspective of blindly being content in captivity and the perspective of seeking freedom by all means necessary.

The above example is a perfect example of the strengths of combining imaginative techniques with the discursive format, it is simply a way to enhance the presentation of ideas within the discursive framework.

Of course, discursive pieces can still be written without extensive imaginative elements, but points for and against particular perspectives should not become boring or monotonous — try to incorporate creative techniques when possible; metaphors can easily be employed to strengthen points.

More Examples

Discursive-imaginative ‘Writer’s Dilemma’

This example includes good personal voice while incorporating imaginative techniques to support arguments and engage the reader, the author has taken the liberty of introducing the arguments sequentially maintaining a logical flow between the arguments.

Topic Starters

Evaluating and improving your discursive piece.

It is best not to memorise a discursive piece word for word to take into the exam. Due to the possible stimulus being entirely different every year, rather than creating something beforehand and adapting it during the exam (Markers can tell!), it is better to create a new piece that plays with the ideas presented in the stimulus.

Don’t worry! By practicing writing, this becomes easier over time. Make sure to refer to HSC past papers to get an idea of what types of stimulus could potentially be asked of you. Don’t be afraid to try out various writing styles and techniques, experiment with humour, satire, or unconventional structures to make your piece more engaging.

Evaluation Checklist

- Balanced Perspectives : Assess whether you have presented each argument as equally viable, ensure that your arguments are not biased. Your piece should demonstrate the complexity of the issue you are exploring.

- Evidence and Examples : Assess the strength and relevance of the evidence and examples you have used, evidence can simply be an exploration of why the argument is valid in certain cases, this can be supported through figurative techniques such as metaphors.

- Relevance to the Stimulus : Ensure that your piece directly addresses some of the ideas presented in the stimulus, the wording of the stimulus will instantly tell you whether the ideas are up for interpretation or if there is a stricter topic the paper wants you to write about.

- Personal Voice : Try to maintain a strong personal voice throughout the piece, techniques, if used correctly, will strengthen the plausibility of your arguments and your conveying of the issue.

How to Write an HSC English Creative Writing Piece

How to Write an HSC English Persuasive Writing Piece

Return to Module 3: Module C: The Craft of Writing

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Have no idea what a discursive writing piece is or how to write one for Module C? Let us walk you through how to write one for HSC English!📝

The HSC Paper 2 Module C question can require you to write a discursive response and a reflection statement. In this post, we share Year 12 student Carmen Zhou's exemplary discursive essay and reflection so that you can see what you need to produce to attain a Band 6 result.

Writing a discursive essay, step-by-step. Now we’ll explore in-depth how to write a discursive essay. This process has the following steps: Brainstorm your ideas; Research and develop your ideas; Plan your response; Begin writing your introduction; Write the body of your discussion; Finish by writing a conclusion; Reread and proofread your ...

In this video, we introduce you to discursive writing by defining it and contextualising it in Module C. Watch more of our video lessons at http://www.getato...

For HSC English Module C: The Craft of Writing, Jonny outlines some key tips to help you adapt your discursive piece into an imaginative piece, and how to change the language and tone between...

Write from multiple perspectives and create a balanced HSC English discursive writing piece with our expert guidance. Learn how to introduce your topic engagingly, and present the issue.