Assessment and Reporting

Student portfolios, portrait of a graduate, equity & inclusion, family engagement, all resources, recommended resources, discover & engage, blog & podcasts, partner stories, help center, drop-in webinar, navigating change in k-12 school districts: strategies for effective change management.

If you work in education long enough, you will likely hear someone marvel at complexity. It sounds like this, “Yes, we definitely need to rethink our grading practices, but it’s just so complex .” When people say this, they are inferring that change is impossible amidst the many intersecting interests in education today. Transformation is always possible, but it requires a deeper understanding of the research into change management. This blog outlines why change management is important in K–12 education and explores how school districts can leverage change management strategies to support educational transformation.

Why is Change Management Important in K–12 Education?

Without an understanding of change management, well-intentioned initiatives are likely to become another addition to the graveyard of good ideas that died during implementation. When change is not managed well, the initiative is seen as a top-down mandate that stakeholders will appear to comply with on the surface. However, they are often stalling long enough for the next initiative to come along. But, when change is managed effectively, we can embed a process of continuous improvement that will continue long after the initial catalyst is gone.

To understand effective change management, we need to first acknowledge that change is hard, especially in education. Organizational psychologist, Adam Grant, points out in Think Again that we’re biologically programmed to stick to what we know:

“Yet there are also deeper forces behind our resistance to rethinking. Questioning ourselves makes the world more unpredictable. It requires us to admit that the facts may have changed, that what was once right may now be wrong” (pp. 4).

This quote is profound in the context of education as everyone who enters this profession believes they are doing what’s best for kids . To suggest change is to challenge this intention. As well, every member of our community has had their own experiences in school. This makes it hard to move forward according to research-validated evidence.

Building a Vision for Transformation

Though the barriers in K-12 education are intimidating, research into change management teaches us how to create a vision that will move people away from the status quo. One of the most cited researchers in this area is John Kotter. He studied change across many organizations to land at eight critical steps to successful transformation . To create a vision, Kotter describes that a senior leader must first communicate a sense of “urgency for change.”

- What is possible for students, teachers, and society?

- What urgent problems need solving to reach that vision?

- What is the price of inaction?

After communicating a sense of urgency, the next step is to “establish a powerful guiding coalition” that represents a diversity of perspectives. It is this team that creates a compelling “vision for change.” It might be a list of guiding principles, a framework, a model, etc. Whatever format it takes, it must be an intuitive tool to guide implementation.

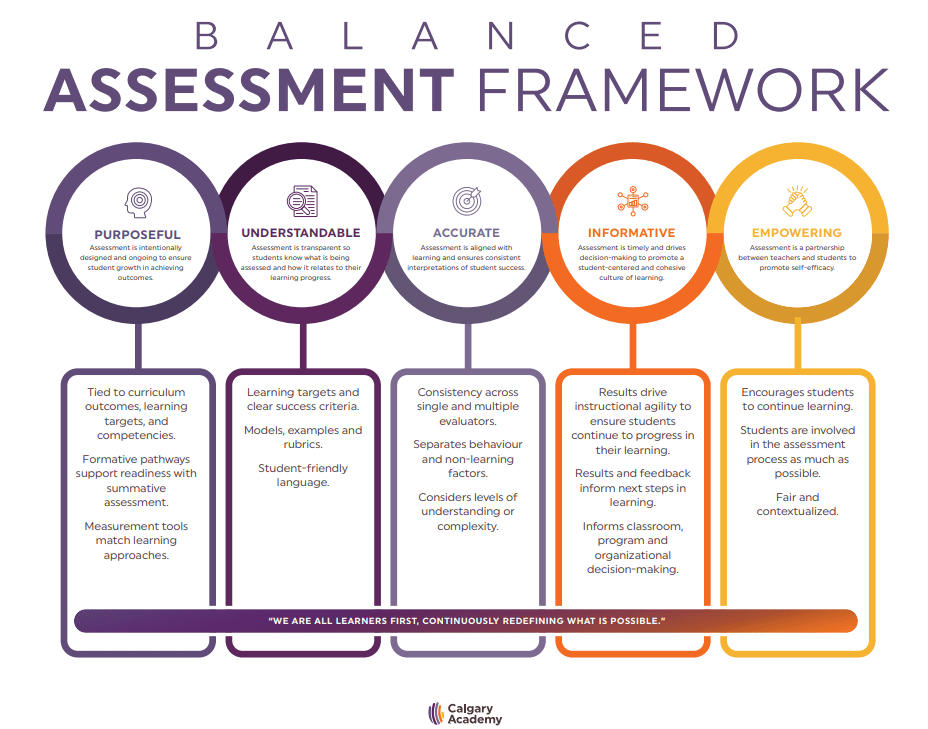

Example of a Change Management Vision

Balanced Assessment Framework ( Calgary Academy )

Leadership in Educational Change

Once the vision is established, leadership becomes critical to implementation. However, the definition of leadership in this context extends far beyond those with supervisory responsibilities. While district leaders maintain a sense of vision and urgency whenever they communicate to stakeholders, it’s a distributed leadership approach that will spread ideas like a virus until a tipping point.

In his research, Kotter refers to this critical stage as “empowering others to act within the vision.” One way to spark distributed leadership is to create action teams of teacher leaders to design the implementation of the vision within their contexts. For instance, a shift towards standards-based grading might engage action teams to determine the reporting standards for a particular subject across their division. Another way to spark informal leadership is to hold space for stories of innovation during PD days and staff meetings.

Engaging Stakeholders in the Change Management Process

Once the vision is established and leadership is distributed, it becomes important to engage key stakeholders. Engagement with families is most successful when it is invitational, rather than explanatory. For instance, rather than only communicating with parents once the change is enacted, engage them before implementation to build capacity and seek feedback. This can be done by inviting them to panels featuring leading experts, surveying them around the elements of the vision, and inviting them to join focus groups for a more in-depth understanding of their perspective. The same goes for students. An important consideration in stakeholder engagement is to also design focus groups that invite and amplify marginalized voices in the community to ensure equity (Safir & Dugan, 2021).

Data-Driven Decision Making

The early stages of implementation will provide the most important information for continued decision-making. When it comes to teachers deciding whether to buy into this new idea, evidence of impact is what will shift their mindset (Guskey, 1986). They need to see that this change will be a better practice for student learning.

Kotter refers to this phase of the implementation journey as “planning for and creating short-term wins.” This win is often planned by the guiding coalition as they engage with all stakeholder groups, including teachers. An example of an early win in a district looking toward grading reform was the removal of four reporting periods in exchange for one linear grading period per year. Many stakeholders felt the chunking of learning into quarters was artificial and made it hard to accurately describe the learning journey from September to June.

Overcoming Resistance to Change

Of course, despite our very best efforts to engage and include all members of the community in change, there will be vocal resistors. How do we get them on board? To return to Adam Grant’s research, “Psychologists have long agreed that the person most likely to change your mind, is you.” This means we can’t enter conversations with resistors trying to change their minds, we can only create the best conditions for them to do so on their own . Grant suggests several strategies to achieve this:

- Find the steelman in their argument. What aspect of their concerns can you validate and agree with?

- Ask questions with genuine curiosity. We want to help them explore the nuances of their own thinking.

- When the opportunity presents itself, offer only one potent point. Research shows that our influence goes down with each subsequent point we include.

Implementing Sustainable Change Initiatives

Research into change management demonstrates it takes 3-5 years for an organization to successfully navigate implementation (Learning Forward, n.d.). Though change can take five years, many organizations reach a tipping point in three years. However, a critical part of the implementation journey at this tipping point is to ensure processes and routines are in place to support sustainability. This marks the difference from an initiative being just another “thing” to it becoming an integral part of a culture. This might look like embedding the change into existing structures, such as using collaborative team meetings in a PLC to embed standards-grading principles, or creating new ones, such as building an accessible digital space to organize rubrics and instructional materials as teachers implement standards-based learning.

Addressing Common Pitfalls

Throughout the change journey, there are many common pitfalls to avoid. First, we often forget that change is more emotional than clinical. Even the most detailed implementation plans and data analysis will fall flat if we forget this truth. A common mantra my colleagues and I use in our work is, “urgency with ideas, patience with people.” While the district leader must communicate passionately about the vision, that passion cannot be misguided toward hasty implementation.

Another common pitfall is to let the loudest resistors stall the change process. In any intervention, we can predict that 5-15% of folks will need a more targeted or personalized approach (Lewis, Sugai & Colvin, 1998). Often, the reason these folks are in a leader’s office loudly protesting is they know they are the outliers. They’re feeling desperate. We can listen to them empathetically, and look for the steelman, but remember there is a quieter 80% who are curious and waiting for the next steps.

Celebrating Success and Continuous Improvement

There is one critical piece of the journey to educational change that is often forgotten – celebration. Assessment expert, author, and consultant Katie White discusses the impact of celebration when she writes, “Everyone needs to feel like they are doing things right—making good decisions and accomplishing goals” (2021). How can we support each teacher to celebrate throughout the change journey? White suggests that celebration is most impactful within the cyclical process of self-assessment. She suggests a three-phase process that teachers can be supported through as well:

- Analysis and reflection

- Goal setting

- Celebrating growth

A critical note here is to ensure that goals are evidence-based in the context of the wider vision. When celebration is personalized and tied to evidence-based goals, it becomes meaningful.

Leading change in a complex system like education is challenging, but it’s not impossible. Think of managing change like driving a car along a country road in the dead of night. Our vision, like headlights, illuminates only the next 100 yards. This allows us to take one step forward and then the vision lights our path for the next one. Eventually, we will have traveled, step-by-step, to our destination.

Adopting a new tech tool in your school or district? Download this infographic on how to get educator buy-in .

Engaging Teachers in Tech: 5 Steps to Garner K-12 Educator Buy-In

- Grant, A. (2021). Think again: The power of knowing what you don’t know . Viking, Penguin Random House; New York, New York.

- Kotter, J. (2012). Leading Change . Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

- Safir S. & Dugan J. (2021). Street data a next-generation model for equity pedagogy and school transformation . SAGE Publications.

- Guskey, T. R. (1986). Staff Development and the Process of Teacher Change. Educational Researcher , 15(5), 5-12.

- Learning Forward. (n.d.). Standards for Professional Learning. Retrieved December 1, 2023, from https://standards.learningforward.org

- Lewis, T., Sugai, G. & Colvin, G. (1998). Reducing Problem Behavior Through a School-Wide System of Effective Behavioral Support: Investigation of a School-Wide Social Skills Training Program and Contextual Interventions. School Psychology Review . 27. 446-459.

- White, K. (2021). Student self-assessment: data notebooks, portfolios, and other tools to advance learning . Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Try these next...

SpacesEDU by myBlueprint is a digital portfolio and proficiency-based assessment platform that allows career and technical education (CTE) students to easily showcase ...

Career and Technical Education (CTE) is an integral part of today’s education system, providing career exploration opportunities and helping prepare students with ...

Career and technical education (CTE) differs from traditional education by emphasizing practical skill development and real-world application.

JavaScript seems to be disabled in your browser. For the best experience on our site, be sure to turn on Javascript in your browser.

Hello! You are viewing this site in English language. Is this correct?

Explore the Levels of Change Management

Empower and Drive Change Management in Higher Education

Timothy Slottow

Updated: April 2, 2024

Published: March 22, 2024

Research consistently supports the need to align leadership approaches with the unique needs of faculty, staff and students to achieve success. But, according to the National Student Clearinghouse , universities and colleges face challenges on a much larger scale.

- Post-secondary enrollment is over a million students below pre-pandemic levels

- The number of students dropping out before completing a degree rose to over 40 million

- Only 3.6 million college and university students graduated last year, a four-year low

Leaders in higher education are now tasked with improving these poor outcomes while undergoing significant changes to keep pace in a transforming landscape—from incorporating remote learning opportunities to integrating new technologies. According to EDUCAUSE , a third of surveyed institutions increased their central IT operating expenditure by over 30% between 2022 and 2023.

In this context, it’s clear that the leaders in higher education need to expand their focus to embrace a systemic change management approach that allows for more.

What it Means to Be an Effective Leader in the Changing Higher Education Landscape

Leaders in higher education are as diverse and multifaceted as the institutions they represent. The context of their work is equally dynamic—institutional leaders navigate a landscape of entrenched traditions, cultural change, and the relentless tide of technological innovation.

Key academic leaders, such as university presidents, provosts, deans and department chairs, are the primary sponsors of change in higher education—not to mention key C-suite stakeholders across finance, human resources, IT and academic departments. These leaders authorize major transformations and also play a major role in helping their institution realize the desired benefits of a digital transformation or policy overhaul.

Specifically, these academic leaders help coordinate the change effort from a high level, engaging constantly with project and people leaders across academic and administrative departments.

It’s crucial to remember that key stakeholders—including students, faculty, administrative staff and well-funded academics—also play an important role during times of change. While these individuals may not be the initiators of change, some are critical influencers during change, and all of them need to adopt the change for it to be successful.

Unfortunately, there are many challenges facing both the primary sponsors and key change agents in academia as these institutions try to keep up with the changing education landscape .

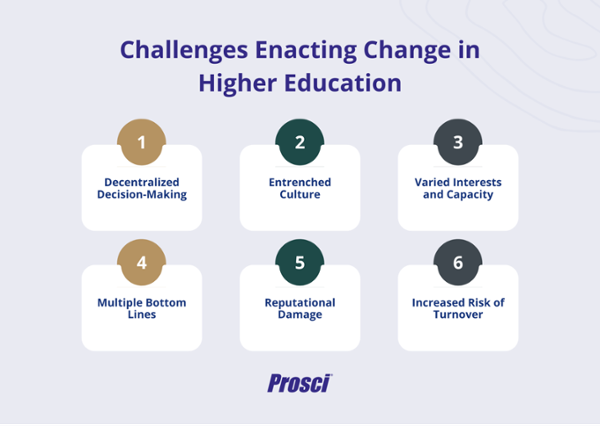

The Challenges of Leading Change in Academia

The unique culture of higher education makes the change process arduous. Unlike organizations in the business world, university and college leaders must contend with a range of unique attributes while trying to implement new policies, initiatives or infrastructure changes.

Those leading or sponsoring change initiatives in higher education often come up against many of the following issues:

Decentralized decision-making – Complex and layered governance can slow decision-making and dilute accountability. Faculty governance means deans and department chairs can have high power and autonomy.

Entrenched culture – Many leading academic institutions have been around for centuries, creating deeply rooted traditions and highly esteemed values. Furthermore, tenured faculty can often be more resistant to change than non-tenured counterparts.

Varied interests and capacity – There can be large disparities between departments regarding priorities, budgets and values. For instance, business, engineering and medical schools often have more financial resources and sway than other schools and institutes.

Multiple bottom lines – Return on Investment (ROI) is defined differently in the higher education context, especially with public funding. These institutions have the typical financial goals of large organizations but also prioritize non-financial outcomes like retention, graduation rates, growth in sponsored research, faculty recruitment/retention, faculty recognition and national rankings. The multiple stakeholders beyond students and faculty vying to influence leadership goals and decision-making can be overwhelming—e.g., alums, donors, city/state lawmakers, federal regulators, federal grant agencies, and accreditors.

Reputational damage – Many universities and colleges prioritize maintaining a strong reputation in academia and the public eye. Key stakeholders may resist significant change if they believe that failure to achieve outcomes will negatively impact that reputation.

Increased risk of losing talent – With higher education’s unique factors of tenured faculty, entrenched culture and extreme decentralization, poorly managed change efforts are more likely to lead to loss of valuable talent in key areas throughout the university.

These issues all contribute to the dismal state of change in higher education, where over 70% of large-scale initiatives fail to achieve desired outcomes. So, how can universities and colleges enact successful change in an environment where governance structures and cultures are so resistant to change?

Empowering Higher Education Leaders to Enact Change

The sheer variation in governance structures, leadership roles, and levels of autonomy interacting in academia precludes using a one-size-fits-all change management approach. It requires a structured, flexible approach to managing the change and a nuanced understanding of the institution's culture, the specific change and those impacted.

With 25 years of applied research in organizational change, Prosci has developed a framework that adapts and scales to the needs of these complex organizations and their leaders. In that time, our team has collected over two decades of longitudinal research on the dynamics of change within large institutions.

Here are three of the biggest findings observed over this time:

1. Active and visible sponsorship is the number one contributor to successful change management

Since 1998, one factor has led the way in Prosci benchmarking reports in terms of the biggest contributor to change management success— primary sponsorship .

These individuals ultimately sign off on investment in change and, while they may not lead the initiative directly, play an indispensable role in determining its outcome through active and visible promotion. Our research shows that primary sponsors who follow the ABCs of sponsorship—active and visible participation, building a coalition of sponsorship, and communicating support—strongly correlate with achieved outcomes.

2. The use of a structured change management approach is the second strongest predictor of successful change

Outside of effective primary sponsorship, there’s no more important contributor to successful organizational change than a structured change management approach.

Researchers, industry experts and consultants have developed methodologies, often based on change theory, that can be flexibly applied across different organizational contexts—even those as complex as higher education. Prominent examples include Kurt Lewin’s change model, Kotter’s 8-Step Change Process, and the Prosci ADKAR® Model.

Prosci research shows that organizations that apply effective change management are seven times more likely to meet or exceed objectives.

3. Middle management is the leading employee cohort in terms of resistance to change

Prosci research consistently points to middle managers as the most resistant to change within the organization. This resistance can culminate in technical system changes, an emotional reaction to a changing power structure, and other technical and human factors. Considering middle managers are the connective tissue between the upper level of a company and its front-line workers, overcoming this resistance is vital.

Over time, we’ve also discovered and tested a range of solutions for overcoming resistance to change within this central tier of the organization.

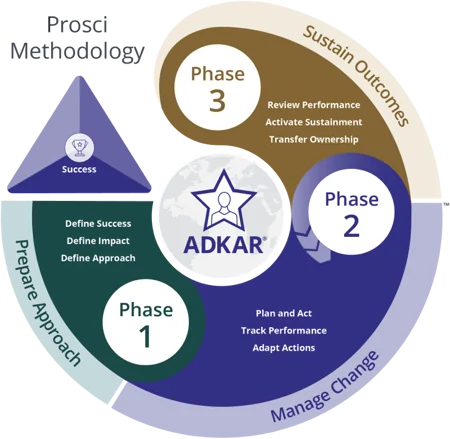

The Prosci Methodology

The Prosci Change Management Methodology stands at the forefront of enabling organizations, including higher education institutions, to navigate the complexities of change with a structured and practical approach. At the core of the Prosci Methodology and models is the understanding that successful change isn’t just about the technical solution being implemented but also about the people involved and being impacted.

Here are the structured, scalable and adaptable approaches Prosci takes to driving organizational change:

PCT Model – The Prosci Project Change Triangle (PCT) Model is a framework that highlights these four critical aspects of successful change efforts:

- Leadership/sponsorship

- Project management

- Change management

- A shared definition of success

This model underscores the importance of a shared definition of success across these areas. In higher education, leaders need to actively sponsor and support change initiatives, aligning them with the institution's strategic goals and managing the people side of change.

ADKAR Model – The Prosci ADKAR Model is a goal-oriented tool that guides individual and organizational change through five key outcomes:

- Awareness of the need for change

- Desire to participate and support the change

- Knowledge of how to change

- Ability to implement required skills and behaviors

- Reinforcement to sustain the change

This model is handy for leaders in higher education, as it helps them understand and address the individual change journey their faculty, staff, students and other stakeholders experience.

Prosci 3-Phase Process – The Prosci 3-Phase Process is a structured yet adaptable framework designed to guide organizations through successful change management. It divides the change process into three key phases:

- Phase 1 – Prepare Approach – This phase involves defining the change strategy, preparing the change management team and developing the sponsorship model.

- Phase 2 – Manage Change – During this phase, the team develops and implements plans for communication, sponsor activities, training, coaching and resistance management.

- Phase 3 – Sustain Outcomes – The final phase focuses on collecting and analyzing feedback, diagnosing gaps, managing resistance, and implementing corrective actions and recognition.

The PCT Model, ADKAR Model, and 3-Phase Process complement each other to create change. It's particularly relevant in higher education, where institutional challenges and governance structures greatly influence the success of change initiatives.

Prosci Drives Change at Leading Institutions

The Prosci Methodology has guided prestigious institutions like Texas A&M and the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) through significant change initiatives, demonstrating the power of adaptive leadership and strategic change management.

Texas A&M University (TAMU)

The Texas A&M University System needed to overhaul its 35-year-old legacy payroll system to a cloud-based version—a process that would impact 200,000 students, faculty and retirees across numerous organizations. In addition to the technical challenges this represented, the project leader faced long review cycles, a lack of alignment on the ideal solution and a decentralized process for determining finances. What appeared to be a technical process was a change that affected every level of the university ecosystem's operations.

The Prosci team stepped in to facilitate this transition, recognizing the need for a leadership approach that was directive, inclusive and repeatable. Using the Prosci 3-Phase Process and ADKAR Model to guide the process, Prosci helped TAMU’s Executive Director of Project Management with the following:

- Identification of the over 10,000 stakeholders most impacted by the project and an assessment of their leadership styles and training needs.

- Proactive management of likely areas of resistance, including repeated communication of upcoming changes and access to technical coaching.

- Strengthening ties between the A&M System sponsors and the Chief HR and Financial Officers from each university and agency through an Executive Advisory Committee (EAC).

- Application of the ADKAR Model to create training curriculum and eLearning modules for full-time employees, HR liaisons and managers.

- Facilitate collaboration between the EAC and key change agents in middle management to develop a communications plan that resonates with all impacted parties.

Read the full case study for a closer look at how TAMU’s $4.5-billion higher education network successfully navigated change in a complex, decentralized environment.

University of California, San Diego (UCSD)

UCSD, a top-15 research university worldwide, needed to change numerous processes and systems to create a more collaborative cross-discipline environment. This plan would impact all aspects of the campus. University leadership knew that a comprehensive change management plan was required to ensure that the tens of thousands affected by the transition would receive support throughout. This required a balance of leadership styles, blending democratic and transformational approaches to engage a diverse academic community.

UC San Diego partnered with Prosci to speed up the transition process and leverage our decades of experience enacting complex change. Working closely with the Staff Education and Development team, Prosci helped drive change in the following ways:

- Preparing UCSD change agents for the necessary large group training sessions through the Prosci Train-the-Trainer Program

- Facilitating award-winning development days that empowered 90% of the 500 attendees with new knowledge and tools

- Building off the success of development days by promoting and regularly hosting change management training and services on campus

- Augmenting change management training with smaller-scale webinars based on pressing issues like resistance to change and sponsor engagement

UCSD's initiative led to a more change-capable organization, where the principles of change management became embedded in the university's culture, paving the way for ongoing and future transformations.

Read the full case study to see how Prosci helped UC San Diego empower key leaders to embed change management materials throughout their campus and foster a pro-change environment.

Training and Supporting Key Change Agents in Higher Education

Prosci empowers leaders in various organizational contexts, including higher education, to drive and manage change effectively . Prosci has been applying research on best practices in change management for over 25 years, and we base our structured methodology and analytic tools on that research.

With decades of experience, Prosci offers comprehensive enterprise training and supportive advisory services tailored to meet the unique challenges and dynamics of leading institutions like Texas A&M and UCSD. These resources are invaluable for institutions seeking to foster transformational leadership and successfully navigate the complexities of change.

To explore how Prosci can assist your institution in harnessing effective leadership for change management, visit the Enterprise Training and Advisory Services pages for more information and guidance.

Tim Slottow is a former C-suite executive with more than three decades of experience sponsoring enterprise-wide changes while driving organizational performance in a variety of industries. The former President of the University of Phoenix, and EVP and CFO for the University of Michigan, Tim has successfully guided teams through disruptive changes, including mergers and acquisitions, organizational restructurings, and cost reduction initiatives. Tim is an Aspen Institute Fellow and frequent lecturer who has served on multiple boards in the higher education, insurance and healthcare sectors.

See all posts from Timothy Slottow

You Might Also Like

Enterprise - 7 MINS

Supporting Project Results With eLearning

5 Tips for Building Organizational Change Management

Subscribe here.

- Blended Learning

- Communications

- Competency-Based Learning

- Crisis Management

- Curriculum Strategy & Adoption

- Decision-Making

- Digital Content

- Innovative Leadership

- Instructional Model Design

- Learning Walks

- New School Design

- Organizational Leadership & Change Management

- Personalized Learning

- Professional Development

- Remote Work

- Return Planning

- School Districts

- Social & Emotional Learning

- Statewide Initiatives & Consortia

- Strategic Planning

- Teacher Retention

- Teams & Culture

- Virtual Learning

By: Nick Esposito on June 25th, 2024

Print/Save as PDF

How to Effectively Manage Large-Scale Change in School Districts

Innovative Leadership | Organizational Leadership & Change Management | District Leadership | Superintendents

Why is change so hard? Navigating change in schools isn't just a leadership challenge—it's a personal journey for every educator and administrator involved. Educators often find themselves adapting to new standards, implementing new initiatives, or integrating innovative tech, which can feel like steering a ship through stormy seas. In this blog, we will dive into some of the reasons why people and organizations are resistant to change and what we can do to effectively manage large-scale change to achieve our goals.

Learning Anxiety Is an Obstacle to Change

W hat is learning anxiety? Diane Coutu defines learning anxiety as coming from a feeling of "being afraid to try something new for fear that it will be too difficult, that we will look stupid in the attempt, or that we will have to part from old habits that have worked for us in the past. Learning something new can cast us as the deviant in the groups we belong to. It can threaten our self-esteem and, in extreme cases, even our identity." As leaders, you may experience anxiety about how to implement change on your campuses - and this feeling is quite normal!

Author Nassim Taleb, an economist and statistician, investigates problems of randomness and uncertainty. His book, Antifragile , reveals how some systems can thrive from shocks, volatility, and uncertainty while others crumble. His arguments help us overcome our learning anxiety and allow us to manage change with confidence by becoming an antifragile organization.

Types of Organizations Facing Change

- In a Fragile Organization , the organization has more to lose than gain. What happens when the wind blows? We are exposed to volatility and we tend to curl up in a ball and ignore the uncertainty.

- In a Robust Organization , the organization plans for as many potential scenarios as possible. What happens when the wind blows? We resist volatility and tend to construct a wall to shield us from the uncertainty of change.

- In an Antifragile Organization , the organization has more to gain than lose and we welcome volatility. What happens when the wind blows? We tend to build a windmill so we are flexible and open to the uncertainty of change, knowing we are capable of managing it.

Becoming an Antifragile District

How can we work to become an antifragile organization that is open to change and can manage it well? How can we implement changes more effectively? We can focus on building antifragile school organizations.There are several key strategies we can implement to build these muscles:

Invest in the Right Things

In your role as leader, be thoughtful in where you invest funds. Consider the Lindy Effect , which states “the longer it’s been around, the longer it will persist” when investing in new technologies, strategies, or initiatives. Or expressed as "things that have stood the 'test of time' are things that you can rely on."

This analysis will improve your ROI and increase your chances of creating buy-in amongst your teams by not always proposing the newest and flashiest options for investment.

- Try This : Reflect on new initiatives by asking, “What opportunities does this new initiative afford us?”

- Note : Not all solutions are right and not all of the right solutions are right for us.

Minimize Downside

In your role as a leader , look for ways to limit the downside as you embark on new initiatives and execute your vision.

- Try This : Leverage our negative knowledge (what doesn’t work) of past initiatives. This preserves space for innovation AND encourages authentic collaboration.

- Note : As you ‘iron out’ potential pitfalls beware of also ironing out potential peaks.

Embrace Randomness

In your role as a leader , intentionally plan for randomness by creating space for collaboration and writing loose and not prescriptive plans.

- Try This : Clearly communicate the initiatives’ fixed and loose guardrails. This ensures that people feel empowered to use the implementation of the initiative to address their personalized needs.

- Note : Like our students, adults each need different supports. Some people will need more guidance while others will benefit from more freedom.

Example: In Personalized Learning implementation we often guide districts through a Capstone / Prototype process in which teachers are able to apply the theory in their own spaces. We bring all of the participants together to showcase their work. This celebrates their effort and infuses a sense of innovation into the organization.

Make Time for Recovery

In your role as a leader , remember that support must come before accountability. As leaders, we must communicate clearly about what success looks like (not the data but the learning).

- Try This : Create space for people to process the realities of implementation.

- Note : Engage all voices!

Create Buy-In

In your role as a leader , develop a vision for what the success of an initiative will look like. This vision should not just include the end of the road, but the road to get there as well

- Try This : Consider the Law of Diffusion of Innovation to identify stakeholders to create meaningful growth. This will create valuable buy-in at the beginning of an initiative (at its most fragile.) Focus on momentum as a success metric.

- Note : Even if people aren’t directly involved in implementation, they should be involved in the communication strategy

By taking the steps above to be a thoughtful leader in implementing change, you will have a better chance of success in achieving your vision for school improvement and transformation. As you build an Antifragile organization, you will see its benefits as you can manage change more effectively, build on success, and create an innovative and engaging learning environment for all students.

- Skip to content

- Skip to search

- Staff portal (Inside the department)

- Student portal

- Key links for students

Other users

- Forgot password

Notifications

{{item.title}}, my essentials, ask for help, contact edconnect, directory a to z, how to guides, leading curriculum k–12, change management research tools.

Lead professional conversations about effective curriculum implementation practices and change management in your school or professional learning network.

Use these research snapshots, text-based protocols, and core thinking routines for leaders to prompt professional conversations. The research snapshots support school leadership teams on their journey through the ‘Phases of Curriculum Implementation ’.

About this resource

Purpose of resource.

This research snapshot is part of the ‘ Leading curriculum Implementation toolkit '. It supports leaders, and aspiring leaders, to explore and reflect on research about effective approaches to curriculum implementation.

Target audience

School leadership teams and aspiring leaders can use this resource to initiate professional dialogue and build collective understanding amongst colleagues.

When and how to use

School leadership teams and aspiring leaders might use the research snapshot to:

- reflect on their own practice to prepare for new curriculum implementation

- mentor new and aspiring leaders through the phases of curriculum implementation

- promote discussion in their leadership team on how best to support or contextualise curriculum reform in their school.

Text-based protocols and core thinking routines can be used alongside the research snapshot to foster discussion and build collective understanding of effective approaches to curriculum implementation.

Research base

The evidence base for this resource is:

- Dao L, (2021) ‘Challenges and enablers encountered by a curriculum leadership team in implementing the national curriculum in one Australian school’, Leading and Managing, 27 (1): 77-98.

Use the pdf link or follow these steps

- Use CESE accessing databases

- Select Informit (How do I log in)

- Insert the article name and search.

- Select the article and download the pdf.

- High Impact Professional Learning (HIPL) .

Email questions, comments, and feedback about this resource to [email protected] using the subject line ‘Leading Curriculum Implementation Research toolkit’.

Alignment to system priorities and/or needs – School Excellence Policy and School Excellence Procedure

Alignment to School Excellence Framework – ‘Instructional leadership’ and ‘High expectations culture’ elements in the Leading domain as well as the ‘Learning and development’ and ‘Collaborative practices and feedback’ elements of the Teaching domain.

Alignment with the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers – 6.2.4 and 6.3.4

Consulted with: Strategic Delivery representatives, Principal School Leadership representatives

Reviewed by: CEYPL Director and CSL Director

Managing curriculum change

Research article – Jones, C and Anderson M (2001) ‘ Managing curriculum change ’. Learning and Skills Development Agency, London, accessed 2 September 2022.

‘Change management involves many factors: quality, resources, staff, students, and funding, to name a few. But above all, it is about processes – how to get to where you want to be.’ (p.9)

This article explores strategies for change management in an international context. The language has been adapted for the New South Wales context.

Research overview

Giving high priority to curriculum change is the first step to creating an environment where effective change can take place.

- Ensure changes to the curriculum are explicit in Strategic Improvement Plans.

- Provide a clear picture of how the change will affect staff, students, and parents.

- Allocate school leaders and teachers responsibility for making change happen.

- Place curriculum change at the top of agendas for meetings.

- Provide adequate resources to make sure that the change happens.

Teaching staff are more likely to accept changes to the curriculum if they are given additional support during implementation phases.

- Divide big changes into manageable steps.

- Develop the coaching skills of middle leaders.

- Demonstrate commitment to change by being visible and available for staff.

As with anything, curriculum change is most effective when it is planned.

- Be realistic about the timescales and resources needed for effective change.

- Look for champions who can motivate others.

- Define what is non-negotiable and what is fixed.

- Include a plan for clear communication.

Effective leadership teams, who lead from the front by setting an example of hard work, flexibility, responsiveness, and commitment have greater success when implementing new curriculum.

- Explain what the change means in positive terms for staff, parents, and students.

- Seek opportunities to talk to staff and community about the change.

Teachers need to develop ownership of the change and the process for curriculum initiatives and quality to be effective.

- Ensure staff understand the ‘why’ for change.

- Give teaching staff an opportunity to share responsibility for shaping curriculum change.

Using the expertise of staff can have positive effects on instigating change and improve staff morale.

- Look for evidence of previous success in curriculum change.

- Build teams that include individuals with recognised expertise.

- Map people skills to specific elements of curriculum change at an early stage of planning.

It is vital that leaders have professional credibility in the eyes of teaching staff.

- Recognise that perceptions influence behaviour.

- Communicate with students about curriculum change and how this will impact them.

Staff need to be kept informed of curriculum change and take part in regular professional development activities. Invest in your teachers.

- Implement action plans.

- Provide staff with appropriate information to keep them fully informed.

- Ensure that staff have the necessary professional development to meet the changing needs of the curriculum.

Professional discussion and reflection prompts

- As a leader, which strategies for managing curriculum change are already in place in your context? Which strategies could be strengthened to effectively implement curriculum change?

- How might you modify your current systems and processes to incorporate new strategies for managing curriculum change in your context?

Challenges and enablers

Research article – Dao L, (2021) ‘Challenges and enablers encountered by a curriculum leadership team in implementing the national curriculum in one Australian school’, Leading and Managing, 27 (1): 77-98.

‘Change is non-linear, complex and multi-dimensional.’ (p 81)

This article explores the change process for implementation of large-scale mandated curriculum change. Internal and external factors can enable, or act as barriers, to successful implementation. Teacher belief, values and motivation also influence effective implementation of educational change. The author uses Sergiovanni’s (1995) change process model to explore the complexity and interaction of different factors when seeking to effectively implement change.

Sergiovanni suggests change is dependent on four interacting ‘units of change’:

- political system.

Challenges to effective curriculum implementation are the:

- need to provide practical support for teachers

- time to plan and develop programs, systems and processes

- availability of appropriate syllabus-aligned resources

- access to professional learning aligned to new syllabuses

- willingness and opportunities to collaborate with colleagues

- effective management of workload issues when implementing multiple syllabuses.

Enablers for effective curriculum implementation include:

- collaboration when planning for implementation

- additional release time to support implementation planning

- resources to support implementation, such as digital curriculum, work samples

- formal and informal (professional dialogue and reading) professional learning both in school and through networks

- As a leader, reflect on the four ‘units of change’. How might they interact to influence implementation of educational change in your context?

- What enablers can you identify in your context?

- What challenges could impact effective implementation of change in your context?

- As a leader, what resources do you have available to overcome these challenges and enable effective curriculum implementation?

- Teaching and learning

Business Unit:

- Curriculum and Reform

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

5 Critical Steps in the Change Management Process

- 19 Mar 2020

Businesses must constantly evolve and adapt to meet a variety of challenges—from changes in technology, to the rise of new competitors, to a shift in laws, regulations, or underlying economic trends. Failure to do so could lead to stagnation or, worse, failure.

Approximately 50 percent of all organizational change initiatives are unsuccessful, highlighting why knowing how to plan for, coordinate, and carry out change is a valuable skill for managers and business leaders alike.

Have you been tasked with managing a significant change initiative for your organization? Would you like to demonstrate that you’re capable of spearheading such an initiative the next time one arises? Here’s an overview of what change management is, the key steps in the process, and actions you can take to develop your managerial skills and become more effective in your role.

Access your free e-book today.

What is Change Management?

Organizational change refers broadly to the actions a business takes to change or adjust a significant component of its organization. This may include company culture, internal processes, underlying technology or infrastructure, corporate hierarchy, or another critical aspect.

Organizational change can be either adaptive or transformational:

- Adaptive changes are small, gradual, iterative changes that an organization undertakes to evolve its products, processes, workflows, and strategies over time. Hiring a new team member to address increased demand or implementing a new work-from-home policy to attract more qualified job applicants are both examples of adaptive changes.

- Transformational changes are larger in scale and scope and often signify a dramatic and, occasionally sudden, departure from the status quo. Launching a new product or business division, or deciding to expand internationally, are examples of transformational change.

Change management is the process of guiding organizational change to fruition, from the earliest stages of conception and preparation, through implementation and, finally, to resolution.

As a leader, it’s essential to understand the change management process to ensure your entire organization can navigate transitions smoothly. Doing so can determine the potential impact of any organizational changes and prepare your teams accordingly. When your team is prepared, you can ensure everyone is on the same page, create a safe environment, and engage the entire team toward a common goal.

Change processes have a set of starting conditions (point A) and a functional endpoint (point B). The process in between is dynamic and unfolds in stages. Here’s a summary of the key steps in the change management process.

Check out our video on the change management process below, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more explainer content!

5 Steps in the Change Management Process

1. prepare the organization for change.

For an organization to successfully pursue and implement change, it must be prepared both logistically and culturally. Before delving into logistics, cultural preparation must first take place to achieve the best business outcome.

In the preparation phase, the manager is focused on helping employees recognize and understand the need for change. They raise awareness of the various challenges or problems facing the organization that are acting as forces of change and generating dissatisfaction with the status quo. Gaining this initial buy-in from employees who will help implement the change can remove friction and resistance later on.

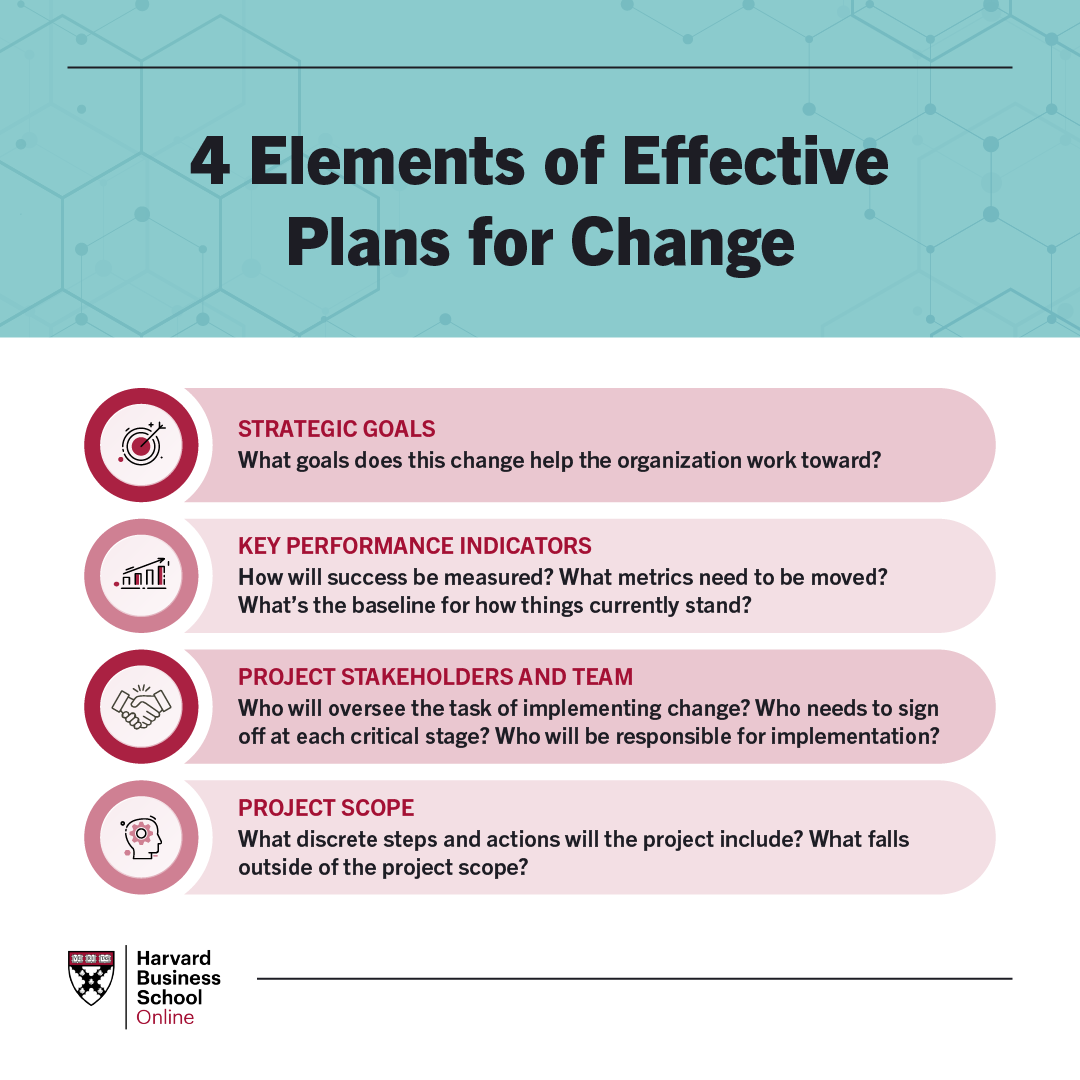

2. Craft a Vision and Plan for Change

Once the organization is ready to embrace change, managers must develop a thorough, realistic, and strategic plan for bringing it about.

The plan should detail:

- Strategic goals: What goals does this change help the organization work toward?

- Key performance indicators: How will success be measured? What metrics need to be moved? What’s the baseline for how things currently stand?

- Project stakeholders and team: Who will oversee the task of implementing change? Who needs to sign off at each critical stage? Who will be responsible for implementation?

- Project scope: What discrete steps and actions will the project include? What falls outside of the project scope?

While it’s important to have a structured approach, the plan should also account for any unknowns or roadblocks that could arise during the implementation process and would require agility and flexibility to overcome.

3. Implement the Changes

After the plan has been created, all that remains is to follow the steps outlined within it to implement the required change. Whether that involves changes to the company’s structure, strategy, systems, processes, employee behaviors, or other aspects will depend on the specifics of the initiative.

During the implementation process, change managers must be focused on empowering their employees to take the necessary steps to achieve the goals of the initiative and celebrate any short-term wins. They should also do their best to anticipate roadblocks and prevent, remove, or mitigate them once identified. Repeated communication of the organization’s vision is critical throughout the implementation process to remind team members why change is being pursued.

4. Embed Changes Within Company Culture and Practices

Once the change initiative has been completed, change managers must prevent a reversion to the prior state or status quo. This is particularly important for organizational change related to business processes such as workflows, culture, and strategy formulation. Without an adequate plan, employees may backslide into the “old way” of doing things, particularly during the transitory period.

By embedding changes within the company’s culture and practices, it becomes more difficult for backsliding to occur. New organizational structures, controls, and reward systems should all be considered as tools to help change stick.

5. Review Progress and Analyze Results

Just because a change initiative is complete doesn’t mean it was successful. Conducting analysis and review, or a “project post mortem,” can help business leaders understand whether a change initiative was a success, failure, or mixed result. It can also offer valuable insights and lessons that can be leveraged in future change efforts.

Ask yourself questions like: Were project goals met? If yes, can this success be replicated elsewhere? If not, what went wrong?

The Key to Successful Change for Managers

While no two change initiatives are the same, they typically follow a similar process. To effectively manage change, managers and business leaders must thoroughly understand the steps involved.

Some other tips for managing organizational change include asking yourself questions like:

- Do you understand the forces making change necessary? Without this understanding, it can be difficult to effectively address the underlying causes that have necessitated change, hampering your ability to succeed.

- Do you have a plan? Without a detailed plan and defined strategy, it can be difficult to usher a change initiative through to completion.

- How will you communicate? Successful change management requires effective communication with both your team members and key stakeholders. Designing a communication strategy that acknowledges this reality is critical.

- Have you identified potential roadblocks? While it’s impossible to predict everything that might potentially go wrong with a project, taking the time to anticipate potential barriers and devise mitigation strategies before you get started is generally a good idea.

How to Lead Change Management Successfully

If you’ve been asked to lead a change initiative within your organization, or you’d like to position yourself to oversee such projects in the future, it’s critical to begin laying the groundwork for success by developing the skills that can equip you to do the job.

Completing an online management course can be an effective way of developing those skills and lead to several other benefits . When evaluating your options for training, seek a program that aligns with your personal and professional goals; for example, one that emphasizes organizational change.

Do you want to become a more effective leader and manager? Explore Leadership Principles , Management Essentials , and Organizational Leadership —three of our online leadership and management courses —to learn how you can take charge of your professional development and accelerate your career. Not sure which course is the right fit? Download our free flowchart .

This post was updated on August 8, 2023. It was originally published on March 19, 2020.

About the Author

| You might be using an unsupported or outdated browser. To get the best possible experience please use the latest version of Chrome, Firefox, Safari, or Microsoft Edge to view this website. |

The Four Principles Of Change Management

Updated: Aug 7, 2022, 10:18pm

No company or organization can operate the same way forever. Whether you’re a rapidly growing startup with agility baked into your DNA or a decades-old corporation responding to market shifts, you need to adjust to progress and improve. How well you can do that depends on how your organization approaches the process of change management.

Featured Partners

From $8 monthly per user

Zoom, LinkedIn, Adobe, Salesforce and more

On monday.com's Website

Yes, for one user and two editors

$9 per user per month

Google Drive, Slack, Tableau, Miro, Zapier and more

On Smartsheet's Website

Yes, for unlimited members

$7 per month

Slack, Microsoft Outlook, HubSpot, Salesforce, Timely, Google Drive and more

On ClickUp's Website

What Is Change Management?

Change management is a structured process for planning and implementing new ways of operating within an organization.

Many academic disciplines have studied and developed theories about the best ways to approach change in an organization. Central to theories across disciplines is the goal of making change happen—i.e., moving an organization forward—with the full support and cooperation of everyone who’s affected by it.

Change management models recognize change can’t happen within one position or department without affecting the entire organization. Theorists developed the models to approach change in ways that acknowledge its effects across an organization, prepare everyone for those effects and get everyone on board for the transition.

Several change management models exist, and your organization can choose which makes the most sense for you. One of the most prominent thought leaders in the field is John Kotter, a professor at Harvard Business School and founder of the management consulting firm Kotter International.

Kotter’s model for change management involves four key principles and eight steps.

4 Principles of Change Management

Kotter’s four change principles include:

- Select few + diverse many

- Have to + want to

- Head + heart

- Management + leadership

Select Few + Diverse Many

Who drives change in your organization? Do decisions and directives tend to come from the same small group of managers or leaders? These are known as the “select few”—and there’s a danger to this approach to change.

Everyone within an organization is affected by change. It’s the “diverse many”—the broader group of people that makes up your company—who have to adjust their processes and activities day to day to accommodate change.

When the directives come from a select few, you skip the step of understanding what everyone else needs to effectively implement change. You also miss out on an opportunity to get them on board, so they’re eager to welcome change when it comes.

Get representatives from across your organization involved at every stage of a change process—from identifying challenges and planning improvements to implementation and reflection.

Have To + Want To

Getting the diverse many involved is your first step to moving change from something they feel they have to do to something they want to do.

A workforce filled with people who feel like they have to implement changes or initiatives is a recipe for complacency. One filled with folks who want to make change is a formula for action.

When the people in your organization are involved in identifying challenges and recommending improvements, they’ll understand the reasoning behind changed processes and new initiatives. They’ll be invested in improvement. They’ll be eager to take the steps needed to implement—and sustain—change that moves your organization forward.

Head + Heart

You must drive decisions and directives for change from both:

- The head: appeals to logic, data and reason

- The heart: appeals to how people feel and what they desire

Putting hard data behind organizational decisions is smart, but implementing change requires more. It also requires employees who are inspired by what the change will mean for their day-to-day work and the organization’s ability to fulfill its mission.

This means digging a little deeper when you communicate change to your employees.

You can’t just share what the change is and how you’ll implement it. You also have to explain the why behind it, the ways it’ll move the needle for the company, your customers or clients, your employees, and the mission they come into work every day to achieve.

Management + Leadership

Navigating change in an organization requires both management and leadership.

That is, you need both the technical skills to manage projects, make a plan and oversee deliverables; and the emotional skills to communicate a vision, inspire action and empathize with concerns.

Any business leader has certainly heard an earful about the differences between managing and leading — but we’re not saying one or the other is better here. To make effective change in an organization, you need the combined strengths of both management and leadership.

Kotter’s 8 Steps to Change Management

Kotter’s eight-step process for leading change within an organization includes:

- Create a sense of urgency. Rather than simply presenting a change that’s going to happen, present an opportunity that helps the team see the need for change and want to make it happen.

- Build a guiding coalition. This group of early adopters from among the diverse many will help communicate needs and initiatives to guide change.

- Form a strategic vision and initiatives. Draw a picture of what life will look like after the change. Help everyone see—and long for—the direction you’re headed, rather than focusing myopically on the steps in front of them right now.

- Enlist volunteers. You’ll need massive buy-in across the organization to effectively implement change. Use your coalition to keep up the momentum on the sense of urgency and continue to communicate the vision.

- Enable action by removing barriers. Learn where employees face challenges to implementing a change because of structural issues like silos, poor communication or inefficient processes, and break them down to facilitate progress.

- Generate short-term wins. Keep up the momentum and motivation by recognizing early successes on the path to change. Continue to recognize and celebrate small wins to keep everyone energized and aware of your progress.

- Sustain acceleration. Lean into change harder after the first few small wins. Use those successes as a springboard to move forward further and faster.

- Institute change. Celebrate the results of successful change. How do changed processes or initiatives contribute to the organization’s overall success? How do they continue to help employees contribute to the mission they care about?

Bottom Line

Creating change within the organization can make people balk, but ensuring that all parties understand why a change is necessary, how it benefits them and the organization as a whole and allowing them to give input on how to implement said changes leads teams to feel invested in the process.

Building a clear vision and celebrating the small wins along the way will make sure that no one is left wondering what’s happening, and encourage them to take the next step forward. Before long you’ll be achieving your goals as a team—use that as an opportunity to get feedback on the process overall so that the next time flows even more smoothly.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are good change management skills.

To effectively drive and lead change in an organization, you need a combination of leadership, management and strategic strengths. You should be strong in both communication and listening, as well as strategic thinking and analysis.

What is change management risk?

Change management risk refers to factors that could derail an initiative or make it fail to achieve its purpose. Part of change management is identifying these risks and creating a plan to mitigate them.

Why is change management difficult?

Implementing change in an organization is hard because of inertia. The easiest way to operate seems to be the way we’ve always operated. Effectively implementing change means stopping and redirecting that force across dozens, hundreds or thousands of employees.

Is a change management strategy necessary to implement?

To achieve the best success with a planned change, it’s best to have a change management plan in place beforehand. It allows the operation’s leaders to create and work with change within the parameters of certain guidelines, concepts, approaches and language.

Is risk management part of change management?

Yes. Creating a plan for change in an organization involves a risk assessment to determine what effects the change will have, as well as the level of risk regarding whether you’ll face resistance to change.

- Best Project Management Software

- Best Construction Project Management Software

- Best Project Portfolio Management Software

- Best Gantt Chart Software

- Best Task Management Software

- Best Free Project Management Software

- Best Enterprise Project Management Software

- Best Kanban Software

- Best Scrum Software

- Asana Review

- Trello Review

- monday.com Review

- Smartsheet Review

- Wrike Review

- Todoist Review

- Basecamp Review

- Confluence Review

- Airtable Review

- ClickUp Review

- Monday vs. Asana

- Clickup vs. Asana

- Asana vs. Trello

- Asana vs. Jira

- Trello vs. Jira

- Monday vs. Trello

- Clickup vs. Trello

- Asana vs. Wrike

- What Is Project Management

- Project Management Methodologies

- 10 Essential Project Management Skills

- SMART Goals: Ultimate Guide

- What is a Gantt Chart?

- What is a Kanban Board?

- What is a RACI Chart?

- What is Gap Analysis?

- Work Breakdown Structure Guide

- Agile vs. Waterfall Methodology

- What is a Stakeholder Analysis

- What Is An OKR?

Best West Virginia Registered Agent Services Of 2024

Best Vermont Registered Agent Services Of 2024

Best Rhode Island Registered Agent Services Of 2024

Best Wisconsin Registered Agent Services Of 2024

Best South Dakota Registered Agent Services Of 2024

B2B Marketing In 2024: The Ultimate Guide

Dana Miranda is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance® who's been writing about money management and small business operations for more than a decade. She writes the newsletter Healthy Rich about how capitalism impacts the ways we think, teach and talk about money. She's the author of YOU DON'T NEED A BUDGET (Little, Brown Spark, 2024).

Cassie is a deputy editor collaborating with teams around the world while living in the beautiful hills of Kentucky. Focusing on bringing growth to small businesses, she is passionate about economic development and has held positions on the boards of directors of two non-profit organizations seeking to revitalize her former railroad town. Prior to joining the team at Forbes Advisor, Cassie was a content operations manager and copywriting manager.

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Belonging

- ACMP Board of Directors

- ACMP & ICF: Change Management & Coaching

- ACMP Press Room

- What is Change Management?

- Join or Renew

- Corporate Member Organizations

- Chapters & Communities

- Volunteer Central

- About the Standard©

- Download Standard & Code of Ethics

- Translations of Standard ©

- Learn About CCMP™

- Apply & Prepare

- Train for CCMP™ (QEPs)

- Renew Your CCMP™

- CCMP Corporate Packages

- ACMP Connect - Learn More

- Business Solutions Center

- Career Center

- Change Hub Practitioner Directory

- Resource Library

- The Way Change Works Podcast

- Member Webinars

- Global Connect 2024

- South Africa Call for Speakers

- Sponsorship Opportunities

| Name: | |

| Category: | |

| Share: | |

| Change Management |

| ) Change Management provides approaches, tools, and techniques that empower an organization to successfully achieve a desired future state. By integrating with other disciplines like strategic planning, project management, organizational development and process improvement, Change Management provides value by enabling people to adopt the change and operate in the future state. The more seamless the transition is for an organizations’ people, the more effectively and efficiently the organization will be in achieving the benefits of the desired future state.

ACMP views Change Management Professionals as an inclusive community of any individuals who: |

Remember Me

6/26/2024 ACMP® Announces Board Members for Fiscal Year 2025

5/29/2024 ACMP News: May 2024

5/25/2024 ACMP Launches New Change Management Training Search Tool

5/2/2024 ACMP News: April 2024

4/12/2024 ACMP’s 2024 Independent Research Award-Winner, Desireé Charnette Deftereos

6/27/2024 MEMBER WEBINAR - Data-driven? Data-informed? Just help me use my data!

7/9/2024 MEMBER WEBINAR - Group Coaching 101

7/25/2024 MEMBER WEBINAR - Organizational Culture and Change: Cultivating a Dynamic Environment

8/6/2024 MEMBER WEBINAR - Managing Change, Managing Meaning: AI, Identity, and a Life Worth Living

8/22/2024 MEMBER WEBINAR - The Faces of Change: Foundations and Strategies

1032 15th Street NW Suite 261 Washington, DC 20005

Join Mailing List Privacy Policy

- What is Change Mgt?

- Board of Directors

- ACMP & ICF

- Corporate Members

- Corporate Membership

- Learn About the CCMP

- CCMP Apply and Prepare

- CCMP Maintenance

- CCMP Certificants

- The Standard

- QEP Program

- QEP Training Calendar

- Change Hub Directory

- Events Calendar

- Online Store

- ACMP Connect

ACMP’s mission is to serve as an independent and trusted source of professional excellence, advocate for the discipline and create a thriving change community .

Updated: 19 March 2024 Contributors: Alexandria Iacoviello, Amanda Downie

Change management (CM) is the method by which an organization communicates and implements change. This includes a structured approach to managing people and processes through organizational change.

A change management process helps ensure that employees are equipped and supported for the entirety of the transition. Several reasons constitute a need for change management. Mergers and acquisitions, leadership adjustments and implementation of new technology are common change management drivers. The organizational development needed to compete with rapid digital transformation across the industry leads companies to implement new products and new processes. However, these innovations often disrupt workflows, presenting a need for effective change management.

Successful transformational change goes beyond a communication plan; it involves implementing change throughout the company culture. A change management strategy can help stakeholders to adopt proposed changes more readily than in situations where such a strategy is not employed. By activating employees as change agents by involving them in the workflow, business milestones can be achieved. Leaders can and should establish the benefits of change through developing a comprehensive change management plan.

Find out how HR leaders are leading the way and applying AI to drive HR and talent transformation.

Register for insights on SAP

Change management should be a thought-out, structured plan that remains adaptable to potential improvements. How change leaders choose to approach organizational change management varies in size, need and potential for employee buy-in.

For example, employees who lack change efforts experience may need a more tailored approach, like receiving guidance from human resources (HR). Employees who experience change on an organizational level may serve as good candidates on the change management team, offering insightful support to leadership and fellow employees.

Successful change management is a cumulative result of all the key stakeholders’ success in understanding the change initiatives. This requires proactively engaging and supporting a positive employee experience —invite employees to give constructive feedback and continuously communicate the business process or scope changes.

Psychologists and change leaders have developed several methods of organizational change management:

Developed by change consultant William Bridges (link resides outside ibm.com), this framework focuses on people’s reactions to change. The adjustment of critical stakeholders to change is often compared to the five stages of grief, but instead, the Bridges’ model is described through three stages:

- Endings: The discontinuation of old processes.

- Neutral zone: The uncertainty and confusion as new roles are being identified.

- New beginnings: The acceptance of new ways.

Owned by a joint venture between Capita and the UK Cabinet Office, Axelos developed the IT Infrastructure Library (ITIL) . The framework uses a detailed guide to manage IT operations and infrastructure. The goal is to drive successful digital transformation through incident-free IT service implementation throughout the change management process.

Over the years, ITIL was improved and expanded upon to enhance the change process. The ITIL framework has four versions, with the latest being ITIL v4. This version prioritizes the implementation of proper DevOps , automation and other essential IT processes. 1 Created to aid in modern-day digital transformation, the Fourth Industrial Revolution prompted ITIL v4.

John Kotter, a Harvard professor, created his process for professionals that are tasked with leading change. 2 He collected the common success factors of numerous change leaders and used them to develop an eight-step process:

- Creating a sense of urgency for change.

- Building a guiding coalition.

- Forming a strategic vision and initiatives.

- Enlisting a volunteer army.

- Enabling action by removing barriers.

- Generating short-term wins.

- Sustaining acceleration.

- Instituting change.

Psychologist Kurt Lewin developed the "unfreeze-change-refreeze" framework during the 1940s. 3 The metaphor implies that the shape of an ice block remains unaltered until it shatters. However, transforming an ice block without breaking it can be done by melting the ice, pouring the water into a new mold and freezing it in the new shape. Lewin drew this comparison for change management strategy, indicating that introducing change in stages can help an organization successfully attain employee buy-in and a smoother change process.

In the late 1970s, McKinsey consultants Thomas J. Peters and Robert H. Waterman wrote a book called In Search of Excellence . 4 In that book, a framework was introduced through its ability to map out interrelated factors that can influence the ability of an organization to change. Around 30 years later, this framework became the McKinsey 7-S Framework. The intersection of the elements within the framework differs depending on the culture or institution. Listed in no hierarchical order, those seven elements are:

- Shared values

The Prosci Methodology, developed by the firm Prosci, is based on various studies that examine how people react to change. The methodology comprises three main components: the Prosci Change Triangle (PCT), the ADKAR model and the Prosci 3-Phase Process.

Sponsorship, project management and change management drive the PCT Model framework. This model puts success at the center of these three elements and is used in the overall Prosci Methodology.

ADKAR Model

The ADKAR model addresses one of the most essential change management pieces: the stakeholders. The framework is an acronym that equips change leaders with the right strategies:

- Awareness of the need for change.

- Desire to participate and support the change.

- Knowledge of how to change.

- Ability to implement desired skills and behaviors.

- Reinforcement to sustain change.

The Prosci 3-Phase Process

A 3-phase process that has a structured but flexible framework. The three phases of the Prosci Methodology are to prepare an approach, manage change and sustain outcomes. 5

Stakeholders can vary depending on the size of the organization and the nature of change. For example, if you are changing a process that directly impacts a product you offer clients, then your clients are essential stakeholders. Whereas if you are changing an internal technology tool, your clients might not be critical stakeholders.

To determine the stakeholders necessary for your change management strategy, define the scope of change first. Next, determine who consistently uses and operates these current processes. Begin by engaging those stakeholders; as you go, it may be determined that there are more key stakeholders to consider. As discussed, it is important to be flexible with adjusting your change management process. Additional stakeholders may need to be included in the change management strategy at different stages.

Common stakeholders in change management are typically executives and leadership, middle managers, front-line employees, developers, project managers, Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) and potentially, clients. To identify the stakeholders involved in change management, consider asking these questions:

- Who leads the business unit undergoing change?

- Who owns the process undergoing change?

- Who are the people sponsoring change?

- Who are the people executing change?

- Who are the people most affected day-to-day by the change?

With the advent of rapid digital transformation and continual innovation, change management is a crucial tool for organizations to succeed. Among the various methodologies of change management are some best practices to consider:

- Clearly define the vision and make goals measurable.

- Ensure employee buy-in is as important as executive sponsorship.

- Be willing to adjust your process, especially if it is not driving the coveted outcomes.

- Engage employees in decision-making when necessary.

- Collaborate with project management on the automation of processes.

- Create your change management plan based on organizational risk tolerance.

Enterprise transformation demands a digital, experience-based approach that inspires continuous organizational change.

Reinvent your HR function with an employee-centric design, innovative technologies and a dynamic operating model.

Reimagine human resources with AI at the core, delivering business value, accelerating the digital agenda, unlocking workforce potential and creating agility.

Learn how to maximize the human-technology partnership to lead in an era of continuous change.