History Cooperative

Hindu Mythology: The Legends, Culture, Deities, and Heroes

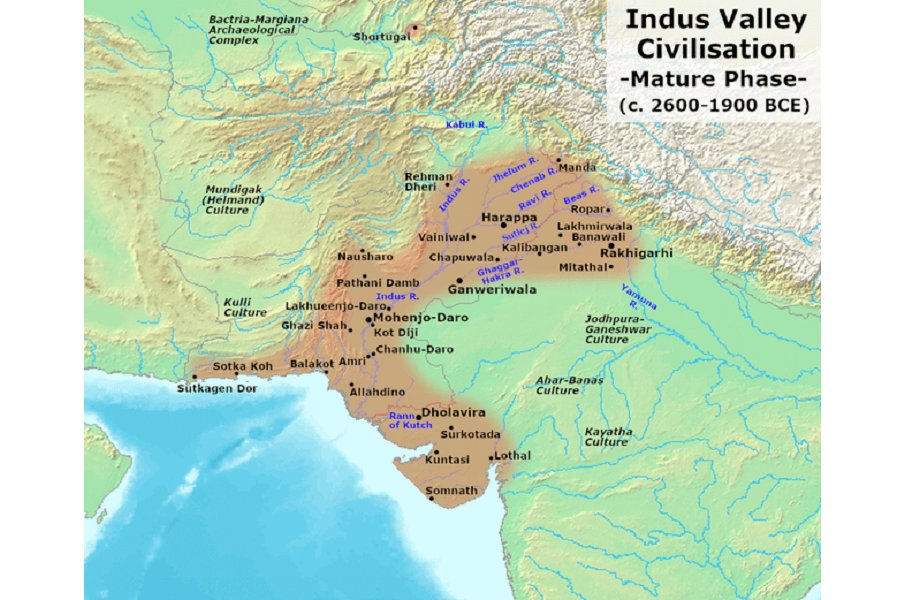

Hindu mythology, alternatively called Indian mythology, involves the all-encompassing lore behind the world’s third-largest religion. As a contender for being the oldest religion in the world, Hinduism had a significant impact on some of Earth’s earliest cultures. For example, Hinduism acted as the socio-theological backbone for the Indus Valley civilization for centuries. While the religion’s influences can be seen in things such as the (controversial) caste system, Hinduism further acted to unite ancient India.

Table of Contents

What is Hindu Mythology?

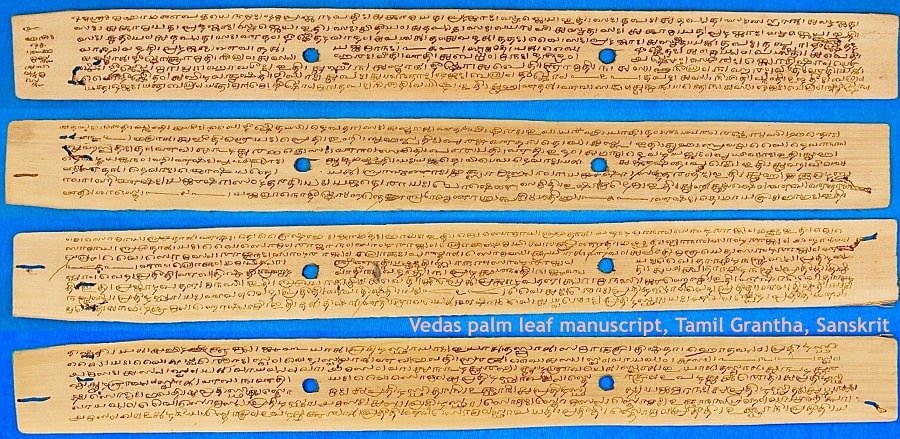

Hindu mythology is a collection of myths and legends that belong to the Hindu faith. Its iconic (and ancient) religious texts are the Vedas, the oldest Sanskrit literature in history. Altogether, Hindu mythology dates back to the 2nd millennium BCE and is believed to have originated around the Indus River.

What is the Basic Hindu Mythology?

The bare-bone basic beliefs of Hinduism include samsara (cycle of life and reincarnation) and karma (cause and effect). Hindus also believe that all living things have a soul – called an “atman” – that is part of a supreme spirit. Therefore, there are animistic principles that are found within Hinduism. The basics of Hindu mythology can be found in the four Vedas: the Rigveda, the Yajurveda, the Samaveda, and the Atharvaveda.

What is Hindu Mythology Called?

Practitioners of Hinduism have taken to calling the religion Sanātana Dharma, which denotes the religion’s primary principles and eternal truths. However, Hinduism has four major denominations: Shaivism, Shaktism, Smartism, and Vaishnavism. There are other, lesser-known sects within Hinduism as well, with their own interpretations of the mythology. On another hand, Hindu mythology has also been used interchangeably with Indian mythology.

Scholars believe that the religion originated in the Indus Valley civilization and its many cultures. The rock shelters of Bhimbetka offer insight into some of the region’s earliest societies, along with their cultural traditions and – perhaps – the threads of Hindu mythology.

READ MORE: Ancient Civilizations Timeline: The Complete List from Aboriginals to Incans

What is the Hindu Creation Myth?

In Hinduism, creation is credited to Lord Brahma . From himself, the universe came to be. He also created the dichotomy of good and evil, as well as the other devas, demons, and earthly creatures. In short, Brahma is the origin of all things.

In the Hindu creation myth, Brahma emerges from a golden egg. The existence of a gilded, cosmic egg is a motif prevalent in other world mythologies. The Brahmanda Purana goes into great detail to describe the cosmic egg and Brahma’s role in creation, along with his creation of mankind. You see, the creation of man came about when Brahma had kids with the goddess Saraswati, the Hindu goddess of knowledge.

Their (very human) son, Manu, would go on to marry the first human woman, Shatarupa, or Ananti, depending on the source. Translations get hazy, and Manu’s wife may or may not have been his sister, born at the same time as he was from Brahma alone. Together, they are the ancestors of all of humanity.

Why are There 14 Worlds in Hindu Mythology?

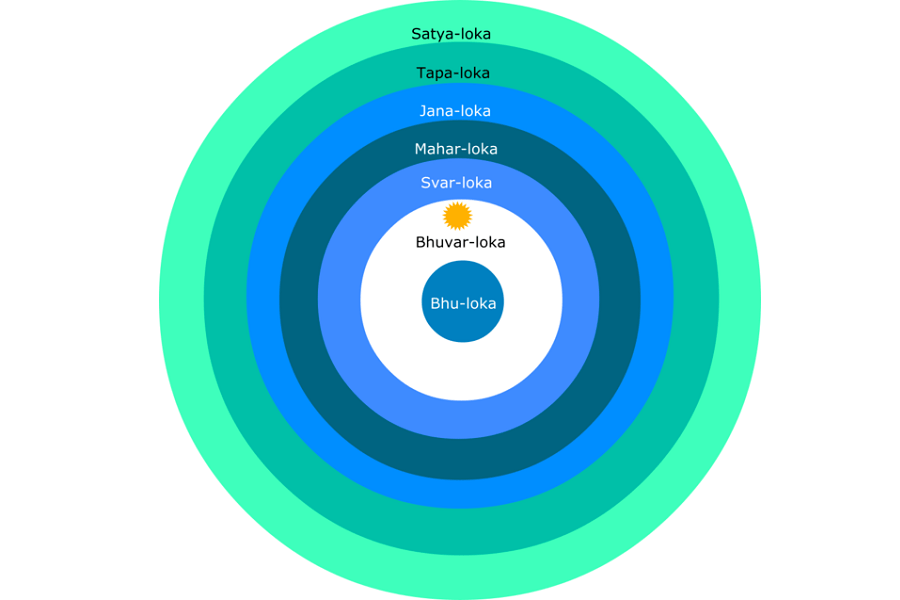

The 14 worlds in Hindu mythology represent varying levels of philosophical spiritual awareness, being more symbolic than anything. At least, that is the popular theory amongst theologists. The 14 realms could, honestly, just be the way the universe is divvied up per the way Hinduism developed.

In Hindu cosmology, there are 14 different worlds, or planes (lokas), which are discussed in the Atharvaveda . They are divided evenly, giving us seven upper worlds – known as the Vyahrtis – and the seven lower worlds, the Patalas. The lokas end up meeting in the middle, thus creating the earthly domain of Bhur-Loka. Major deities, such as Lord Vishnu and Lord Shiva, have their own lokas that they lord over.

The Hindu Pantheon: Meet the Devas

Called devas, Hindu gods and goddesses are some of the oldest and most impressive divinities. Many gods have several aspects, avatars, or incarnations. These manifest in various myths and legends. Each major god has unmistakably iconography, to boot.

Hinduism and Hindu mythology are based on exuberant polytheism. There are countless devas and devis (goddesses), all of whom can influence the natural world. The Hindu pantheon is thought to be home to anywhere from 33 to 330 million gods and goddesses. It all comes down to religious texts and the different sects of Hinduism.

The most noteworthy deities include:

- The Dashavatara – the 10 Incarnations of Vishnu

- The Mahavidya – the 10 forms of Mahadevi

- The Navadurga – the 9 forms of Durga

*Shakti is the name of a goddess and the dynamic energies that flow throughout the universe at large; “shakti” may also refer to power and/or force, though it is primarily used to define cosmic energy

The Trayastrinshata of the Rigveda

The Trayastrinshata is a collection of 33 Hindu deities that are referred to within the Rigveda and other prominent Hindu literature. However, they are not always 33 in number, and exactly who is a member of the Trayastrinshata changes between sources. The general consensus is that the Trayastrinshata are the children of Aditi, goddess of the cosmos, and the legendary sage Kashyapa, although this lineage does vary. In Buddhism , the Trayastrinshata are known as the Trayastrimsa.

The Adityas

The Adityas are twelve gods accounted for in the Brahmanas and the Rigveda . The deities are a portion of the offspring born between the goddess Aditi and the Vedic sage Kashyapa. They uphold moral righteousness and are, more or less, perfect beings. Each member of the Adityas is meant to represent the months as they are depicted in a solar year.

- Vishnu

There are eleven Rudras, all of whom are a form of the Vedic deity, Rudra. How the Rudras came to depend on the source, with some – such as the Matsya Purana – citing their parents as the cow goddess Surabhi and Brahma. Other contenders for parents of the Rudras include the combination of Kashyapa and Surabhi, or the god of death alone, Yama. As the Hindu religion developed, Rudra became synonymous with the god Shiva.

The later Vishnu Purana describes how Shiva split into eleven separate selves while in the form of Ardhanarishvara. Thus, he created the Rudras. His other half (literally and metaphorically), Parvati, did the same and created the eleven wives of the Rudras, called the Rudranis.

The Vasus are eight attendants of the gods Indra and Vishnu. They embody fire, light , and heat. Rather than children of Kashyapa and Aditi, they have also been considered to be offspring of Manu or Yama and a minor goddess named Vasu.

The Ashvins

The Ashvins fulfill the divine twin facet of Hindu mythology. They are described as guardians and protectors, who swoop in on their chariots to save mortals from dire situations. Their parents are oftentimes said to be the sun god Surya and his consort, Saranyu. Unlike other members of the Trayastrinshata, the Ashvins are not known to have personal names.

The Trimurti and the Tridevi

Within Hindu mythology, the Trimurti and Tridevi are prominent deities. Also known as the Hindu trinity, the Trimurti is the divine triad of Brahma (Creation), Vishnu (Preservation), and Shiva (Destruction). Their wives and shakti are the Tridevi. The Tridevi are considered to be the feminine aspects of the masculine Trimurti.

The Matrikas

The Matrikas are seven Hindu mother goddesses. When depicted with an eighth member, they are known as the Ashtamatrikas. Potentially archaic interpretations of the danger that could beset children before adulthood, the Matrikas became associated with fertility, childbirth, and disease. Most notably, the Matrikas evolved to be the guardians of young children and infants.

The Navagraha

The Navagraha are nine celestial deities that represent nine heavenly bodies: the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. The Navagraha also includes the two lunar nodes. In the Hindu Middle Ages, there were only seven identified heavenly bodies and, therefore, only seven deities to represent them. Each deity was associated with a weekday.

The Marutagana

The Marutagana were twenty to sixty storm deities. They are considered to be a part of Indra’s entourage, coming down from the north in a cacophony. Some scholars conclude that the Marutagana in the presence of Indra is the Hindu equivalent of a northern European Wild Hunt.

Who is the Indian God of Creation?

The Hindu god of creation is Brahma. As the creator of the universe itself, Brahma is a mighty god that is disconnected from popular Hindu myths. He does not toil over mortal affairs and exists more of an abstract belief than a deity.

It is thought that the lack of worship of Brahma is explained in a myth where Shiva, his brother and the “destroyer” god mutilates and curses him for developing an obsession with the first woman, Shatarupa. Otherwise, it is said that Brahma’s role ended when the world was created, and he went into an unofficial retirement – if that’s a thing gods could do. Hence, Vishnu and Shiva are still venerated because their roles are still being fulfilled.

Who is the Oldest God in Hinduism?

Brahma is the oldest god in Hinduism since he is the creator of the universe and the progenitor of all living things. Because of this, Brahma has been referred to as “grandfather” in some sects of the religion. Considering his seniority over other deities, it may be shocking to discover that the creator of all things isn’t heavily worshiped in modern Hinduism. The god of destruction, Shiva, is far more popular – especially within Hindu Shaivism traditions.

Brahma is associated with the ancient Vedic god of creation, Prajapati. As a Vedic creator deity, Prajapati could pre-date India’s Vedic Period (1500-1100 BCE) with origins in the Indus Valley civilization.

Why Do Hindu Gods Have So Many Arms?

Hindu gods have so many arms because, in short, more arms equals more power. The phenomenon of deities being presented with four arms in Hindu iconography actually has a name, chaturbhuja . Vishnu is most commonly depicted with the chaturbhuja , which is also an epithet of his, to show his supreme power over the universe.

It is safe to say that although the arms aren’t necessarily flexing, having more than two arms is undoubtedly a flex. A flex of power, that is.

Where Do Hindu Gods Live?

The Hindu gods live in Svarga, alternatively known as Svargaloka (Svarga Loka). It is one of seven higher planes (called lokas in Hinduism) in the religion’s cosmography. Svarga is described as the home of the devas, ruled over by the god Indra from its capital, Amaravati. As a realm of light and splendor, Svarga is a point of contention in the eternal conflict between the devas and the asuras.

Most deities of Hindu mythology reside within the plane of Svargaloka. Despite this, other prominent gods – namely members of the Trimurti – lord over their own respective realms. The god of death , Yama, likewise resides in and rules over his own separate plane, Naraka.

Ancient Vedic Religious Traditions and Hindu Beliefs

The Vedic religion of eld is thought to be the predecessor of present-day Hinduism. Though they have their key differences, the skeleton of Vedic practices still appears within Hindu mythology. In the Vedic religion, key gods included Indra, Agni, Soma, and Rudra, all of which appear in Hinduism. Vedic traditions also include the concept of a permanent afterlife, which challenges Hinduism’s belief in reincarnation.

Generally, it is thought that the Indian subcontinent transitioned from Vedic practices to Hinduism sometime in the sixth century BCE. This would be during the Late Vedic Period. Simultaneously, philosophical traditions began to lean into Hindu concepts, and the Vedic gods merged with newer, more unified Hindu divinities.

Sects and Cults

Today, there are four major sects of Hinduism: Shaivism, Shaktism, Vaishnavism, and Smartism. Although it is easy to assume these sects were founded during the modern period, all four have ancient roots. Each believes in a supreme being, though who that being is changes between sects; in Smartism, who the higher power is varies between practitioners.

Indian folk cults are just as archaic and hold dominant traditions in certain regions of the Indian subcontinent. While veneration of all the gods was standard, their worship included Yakshas and Nagas. In some states, tutelary deities took precedence over other gods. Sacred groves became abundant and nature spirits became focal points of veneration.

Traditional Sacrifices

Sacrifices have a unique place in Hinduism, with myths in the Mahabharata and other Vedic texts addressing the religious practice. Animal sacrifices ( bali ) are amongst the most frequent sacrifices in Hinduism, as they date back to Vedic practices recorded in the Yajurveda . There are records of a horse sacrifice, called Ashvamedha , in the “ Ashvamedhika Parva” of the Mahabharata to establish a sovereign’s rule. Other animal sacrifices of cattle, oxen, goats, and deer are performed during ceremonies and festivals.

Many Hindus today are vegetarian, and bali is only performed by certain sects in some regions of India. This emerges from several later religious developments. The most influential is the 11th century CE Bhagavata Purana , wherein the god Krishna advises man to not perform animal sacrifices in the current age (Kali Yuga). Furthermore, the level of violence in bali caused the practice to become unfavorable in later periods when nonviolence became a cardinal virtue.

There is no real evidence of purushamedha , or human sacrifices, ever being performed in Hindu mythology. There’s a chance that Vedic religion called for it, but there has been no substantial evidence suggesting this. Scholars are sorely lacking both archaeological and literary evidence regarding the prevalence of purushamedha in Hinduism. The degrees of general blood sacrifices varied largely between the Vedic and Tantric Periods of India’s history.

Other sacrifices include food offerings and libations, which are given during rituals, festivals, and daily worship. The size and contents of the sacrifices offered may vary, with many facets of a sacrifice depending on the deity they are meant for.

Festivals and Holidays

Many present-day Hindu festivals have ancient roots. Indeed, today’s festivals and holidays rely on the myths and legends of ancient Hindu mythology. From veneration of the gods to celebrating historical folklore, the festivals of Hinduism are as culturally rich as they are mythologically significant.

- Chhath Puja

- Ganesh Chaturthi

- Ghadimai Festival

- Guru Purnima

- Krishna Janmashtami

- Maha Shivaratri

- Rama Navami

- Vasant Panchami

Legendary Heroes of Hindu Mythology

Indian mythological characters are amongst the most daring legendary heroes. Featured primarily in epic mythology and literature, the all-star heroes of Hinduism often display superhuman characteristics. To be fair, several Hindu heroes are incarnations of the gods. So, being super natural isn’t all that far-fetched.

A majority of Hindu heroes and heroines are found in the two great epics , the Mahabharata and the Ramayana . The Bhagavata Purana is additionally counted as one of India’s great epics. Besides being explored in the longest epic poem ever written, the stories of Hindu mythology’s legendary heroes are gripping, daring, and filled with inexplicable wonder.

- Dronacharya

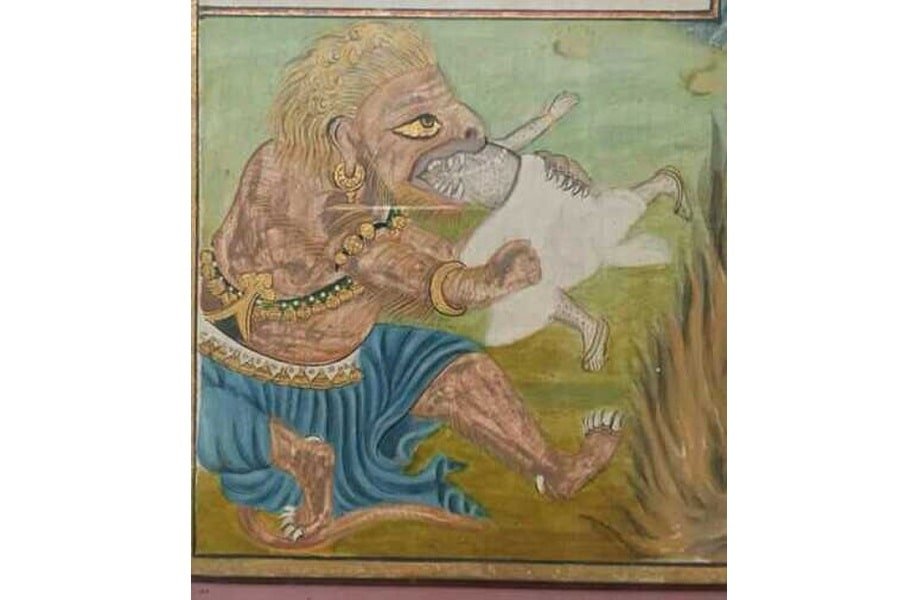

Mythological Creatures in Hindu Myths and Legends

The mythological creatures of Hindu mythology range from everything between legendary creatures, namely vahanas , to entire species of beings. Where sacred stories discuss the presence of nature spirits and malicious demons, there are also tales of sea monsters and dragons. Within Hindu mythos, mythical creatures acted as tools for the gods.

While some entities actively aided and abetted the deities’ miraculous feats, others, like the Asura, hindered them. In all, mythological creatures provided a means to an end while furthering the belief in the existence of good and evil forces in the world.

- The Daityas

- Airavata, the white elephant of Indra

- The Yakshas

- Garuda

Dragons in Indian Mythology

In Hindu mythology, the most famous dragon is the Asura Vritra. A being of drought that hoards water instead of wealth, Vritra was created as an opponent to Indra. While other dragons are not directly named, the role of Vritra and the serpentine Nagas suggests the unique associations early Hindus had between dragons, serpents, and water.

READ MORE: Who Invented Water? History of the Water Molecule

Hindu Mythology’s Many Monsters

Where there are gods, there are bound to be monsters. The monsters of Hindu mythology represent another, darker part of the religion’s beliefs surrounding dharma. That, where there was morality and righteousness, there was immorality and spiritual corruption. Hindu monsters do not challenge the gods as much as they challenge mankind.

*A famous rakshasa is the demon king Ravana, featured in the Ramayana epic; the demon king Ravana is a quintessential Hindu villain, acting on impulse while displaying perpetual ignorance through his actions

Mythical Items found in Hindu Mythology

The mythical items of Hinduism have a range. There’s an elixir of immortality sitting right next to…a celestial missile? Three celestial missiles?! Anyways, which items played an important role in the legends of Hinduism depended on their proximity to the gods.

Items were both personal artifacts and gifts, bequeathed to those deemed worthy. Alternatively, some of the most well-known items in Hindu mythology were legendary plants. These plants could do anything from producing powerful poisons to granting any wish. Although all of the above are considered to have mythical origins, it is thought that some fantastical foliage could be found in nature.

- Kalpavriksha

- Narayanastra

- Pashupatastra

Hindu Mythology in Literary Works

The most famous literary works that are attributed to Hindu mythology are the four Vedas , which are amongst the religion’s most known texts. There are also the Puranas , with major Puranic texts including Shiva Purana and Padma Purana . Additionally, the two great Hindu epics are the Ramayana and the Mahabharata . Overall, some of the most significant literary works that pertain to Hindu mythology are ancient texts that date to the Vedic Period.

Literature is the backbone of most world belief systems. The most popular religions in the world (i.e. Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, etc.) still refer to ancient texts. Moreover, religious doctrines are fantastic sources for locating earlier myths that are otherwise lesser known.

- The Bhagavad Gita

- The Upanishads

- Sangam (Tamil) Literature

Which God is Important to the Hindu Epics?

Vishnu is the most important god in the Hindu epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana . He is the “preserver” god of the Trimurti and therefore acts as a divine judge to quell disagreements. In either epic, the god Vishnu’s avatars are central characters.

Within the Ramayana , the seventh incarnation of Vishnu, Lord Rama, acts as the epic’s protagonist. He is the ideal man and a glorious king, on a journey to save his wife, Sita, from the morally corrupt Ravana. Otherwise, his eighth incarnation, Lord Krishna, acts as a divine advisor to the character Arjuna throughout the legendary Kurukshetra War of the Bhagavad Gita in the Mahabharata . Both incarnations are major deities in their own right, especially in Vaishnavism.

Famous Artwork that Captures Hindu Mythology

Artwork depicting Hindu mythology is found most commonly in temples and architecture. There are votive lingas , auspicious imagery, and niches that show the gods in their many forms or achieving their most courageous feats. Art was created with a conscious effort to capture the gods at their greatest, thereby honoring them further.

The most compelling aspect of Hindu artwork is the presence of mudras . Mudras are found in Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain art. As a type of iconography, mudras are symbolic gestures or poses. They are prevalent in some forms of yoga, traditional folk dance, and religious rituals.

Hindu Mythology in Film and Television

In India, Bollywood is the major film industry, and Bollywood films have an unmistakable charm. Bollywood has done the most justice for Hindu mythology through film and television. Films that delve into Hindu legends, from the Ramayana to the tale of Ashwatthama include:

- Arjun: The Warrior Prince

- Sita Swayamvar

How to Cite this Article

There are three different ways you can cite this article.

1. To cite this article in an academic-style article or paper , use:

<a href=" https://historycooperative.org/hindu-mythology/ ">Hindu Mythology: The Legends, Culture, Deities, and Heroes</a>

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Ultimate Guide to Hindu Mythology

Deities of the Hindu pantheon throughout the millennia

Hinduism is a major world religion, with one of the longest-surviving pantheons in history. Within its rich mythology, elephant-headed gods clash with powerful demons and titans, preserver gods send out their avatars to restore the righteous order of the universe, and powerful sages challenge the gods themselves.

Popular Resources

Pardon Our Interruption

As you were browsing something about your browser made us think you were a bot. There are a few reasons this might happen:

- You've disabled JavaScript in your web browser.

- You're a power user moving through this website with super-human speed.

- You've disabled cookies in your web browser.

- A third-party browser plugin, such as Ghostery or NoScript, is preventing JavaScript from running. Additional information is available in this support article .

To regain access, please make sure that cookies and JavaScript are enabled before reloading the page.

Mythologist | Author | Speaker | Illustrator

First published August 18, 2005

Indian Mythology: Tales, Symbols and Rituals from the Heart of the Subcontinent

An exploration of 99 classic myths of India from an entirely non-Western paradigm that provides a fresh understanding of the Hindu spiritual landscape. Compares and contrasts Indian mythology with the stories of the Bible, ancient Egypt, Greece, Scandinavia, and Mesopotamia. Looks at the evolution of Indian narratives and their interpretations over the millennia. Demonstrates how the mythology, rituals, and art of ancient India are still vibrant today and inform the contemporary generation. From the blood-letting Kali to the mysterious Ganesha, the Hindu spiritual landscape is populated by characters that find no parallel in the Western spiritual world.

Indian Mythology explores the rich tapestry of these characters within 99 classic myths, showing that the mythological world of India can be best understood when we move away from a Western, monotheistic mindset and into the polytheistic world of Hindu traditions. Featuring 48 artistic renderings of important mythological figures from across India, the author unlocks the mysteries of the narratives, rituals, and artwork of ancient India to reveal the tension between world-affirming and world-rejecting ideas, between conformism and contradiction, between Shiva and Vishnu, Krishna and Rama, Gauri and Kali. This groundbreaking book opens the door to the unknown and exotic, providing a glimpse into the rich mythic tradition that has empowered millions of human beings for centuries.

Recent Books

Yog purankatha – marathi translation of yoga mythology.

Yoga Mythology – Marathi Translation…

ABC of Hinduism for Kids

With its simple writing style and fun, colourful illustrations, ABC of Hinduism for Kids is the perfect introduction to a Hindu way of life for your little ones…

Sati Savitri

You have heard tales of patriarchy. This book tells you the other tales―the ones they don’t tell you…

Garud Puran (Hindi translation of ‘Garuda Purana’)

Garud Puran – Hindi Translation…

Why the love story of Radha and Krishna has been told in Hinduism for centuries

Professor of Religion and Asian Studies, Elizabethtown College

Disclosure statement

Jeffery D. Long does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

Although it originated as a Christian holiday in honor of St. Valentine , Valentine’s Day has become a global celebration of romantic love, observed by people of many religions and of no religion.

Other religions have long had their own myths centered on love. I have observed, in my work as a scholar of Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism , that in Hindu traditions, there are many stories of divine couples: deities who embody the ideal of love, and whose stories often contain lessons for the rest of us. One couple that has especially captured the imagination of Hindu devotees for centuries is Radha and Krishna.

Who is Krishna?

The story of Radha and Krishna is first found in the Bhagavata Purana, a text dated by scholars as somewhere between the fifth and 10th centuries. Their story is further elaborated in the Sanskrit devotional poem “ Gitagovinda ,” authored by Jayadeva, who lived in the 12th century in Eastern India.

Krishna, a highly popular and beloved Hindu deity, is regarded, depending on which textual tradition you read, either as an avatar or incarnation of the deity Vishnu, or as the Supreme Being himself. In Hindu belief, Vishnu preserves the order of the cosmos , often through taking on an earthly form to right some wrong and to set the world back on the correct course when chaos threatens to overwhelm it.

The life story of Krishna is an exciting one, full of adventure as well as tragedy. When Krishna is born, his evil uncle, a king named Kamsa, orders all of the male children of the kingdom who are born on that night killed, not unlike King Herod in the New Testament . This was due to a prophecy that one of those children would put an end to his reign. Krishna’s parents, however, are warned of this impending calamity, and the baby is spirited away to safety.

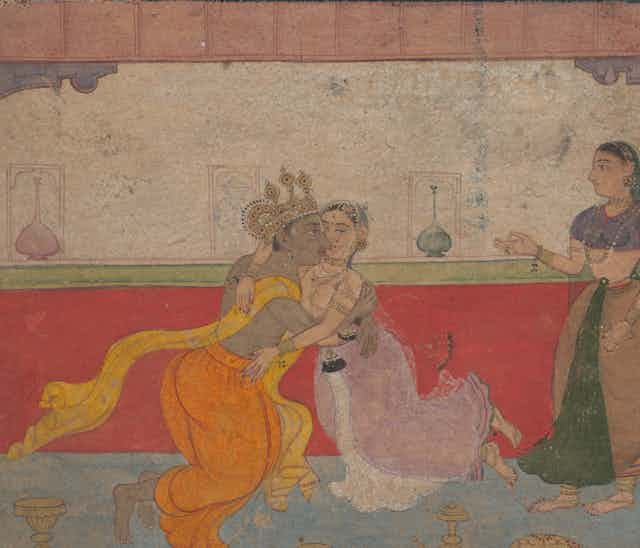

Krishna, therefore, who is born to royalty, has a humble upbringing, growing up amid the cowherds and cowherdesses, or gopis, of the bucolic region of Vrindavan. Stories of Krishna’s teenage years, in particular, are greatly beloved by his devotees. This was a relatively carefree time in Krishna’s life, when he engaged in all kinds of playful mischief with the gopis, and wandered the forests of Vrindavan playing his flute. All of the gopis fell in love with Krishna, and he with them, but the one with whom he fell in love the most deeply was named Radha.

The story of the love of Radha and Krishna is overshadowed by an air of tragedy. The two cannot be together, as Radha is already married and Krishna has a great destiny ahead of him. When the time comes, Krishna must leave Vrindavan and overthrow his wicked uncle, and also play a key role in the fight between two groups of warring brothers, the Pandavas and the Kauravas.

Divine love

This tragic story is dear to devotees not only because of the very real human feelings it evokes, but also because of its deep theological significance in the Vaishnava tradition – the Hindu tradition in which this story features most prominently.

To some, the love between Radha and Krishna might appear to be adulterous or scandalous, given that she is married. The focus of the tradition, though, is not so much on this scandal, but on the deep, spontaneous, genuine love that it illustrates. Radha’s love for Krishna is so strong that it is willing to fly in the face of social conventions. She is willing to risk the disapproval of her community for this love. And according to Vaishnava theology, this is how individuals’ love for God should be. True love for God – called bhakti, or devotion – should be characterized by wild abandon. It should be spontaneous and free.

In Vaishnava theology, the gopis represent the many jivas, or souls, that dwell in the universe, while Krishna is Ishvara, the Lord, the Supreme Being. A very popular and beautiful artistic depiction of the relationship between Krishna and the gopis is called the “Ras Lila.” It depicts the gopis dancing in a circle. Each of them has Krishna for a partner. He has used his divine power to multiply himself so he can dance with each gopi individually.

When Krishna finally has to leave Vrindavan, the pain of separation Radha feels is almost unbearable. When she asks Krishna why she has to feel such pain, he tells her that she must learn to see him in all beings, for he dwells in the hearts of all. The individual soul’s sense of separation from God is similarly painful, and is believed to be a particularly powerful manifestation of bhakti. But that separation can be overcome by seeing God in all beings and in one another.

As Krishna also says in the Bhagavad Gita , “I am never lost to one who sees all beings in me and who sees me in all beings, nor is that person ever lost to me.”

The story of Radha and Krishna can therefore be enjoyed on Valentine’s Day on two levels: as a sad and poignant tale of a past youthful love, remembered fondly but left behind by the call of adulthood, but also as an invitation to be open to love in all its forms.

- Bhagavad Gita

- Valentine's day

- Religion and society

Lecturer in Indigenous Health (Identified)

Social Media Producer

Lecturer in Physiotherapy

PhD Scholarship

Senior Lecturer, HRM or People Analytics

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

Conclusions: Texts, Performances, and Hindu Mythological Culture

- Published: May 2015

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter summarizes the findings of the book and arrives at larger theoretical conclusions regarding the dialogical cultural “work” of Hindu mythological culture, over the past three thousand years, in binding storyworlds to the real world. Special consideration is paid to the dynamic relationship between written literary texts and oral performances involved in the formation of the Hindu mythological tradition. The rest of the chapter then places these ideas themselves in dialogue with those of a modern Marathi kīrtan performer, Vaman Kolhatkar, regarding the power of Vedic mantras and the mediating role of purāṇic mythology in “translating” this sacred knowledge into the everyday cultural sphere of his contemporary kīrtan audiences.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 5 |

| November 2022 | 1 |

| March 2023 | 2 |

| April 2023 | 1 |

| December 2023 | 1 |

| February 2024 | 1 |

| April 2024 | 5 |

| June 2024 | 2 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Hinduism and hindu art.

Krishna Killing the Horse Demon Keshi

Standing Four-Armed Vishnu

Linga with Face of Shiva (Ekamukhalinga)

Standing Parvati

Shiva as Lord of Dance (Nataraja)

Standing Ganesha

Standing Female Deity, probably Durga

Ardhanarishvara (Composite of Shiva and Parvati)

Vaikuntha Vishnu

Krishna on Garuda

Durga as Slayer of the Buffalo Demon Mahishasura

Seated Ganesha

Kneeling Female Figure

Hanuman Conversing

The Goddess Durga Slaying the Demon Buffalo Mahisha

Loving Couple (Mithuna)

Karaikkal Ammaiyar, Shaiva Saint

Vidya Dehejia Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University

February 2007

According to the Hindu view, there are four goals of life on earth, and each human being should aspire to all four. Everyone should aim for dharma , or righteous living; artha , or wealth acquired through the pursuit of a profession; kama , or human and sexual love; and, finally, moksha , or spiritual salvation.

This holistic view is reflected as well as in the artistic production of India. Although a Hindu temple is dedicated to the glory of a deity and is aimed at helping the devotee toward moksha , its walls might justifiably contain sculptures that reflect the other three goals of life. It is in such a context that we may best understand the many sensuous and apparently secular themes that decorate the walls of Indian temples.

Hinduism is a religion that had no single founder, no single spokesman, no single prophet. Its origins are mixed and complex. One strand can be traced back to the sacred Sanskrit literature of the Aryans, the Vedas, which consist of hymns in praise of deities who were often personifications of the natural elements. Another strand drew on the beliefs prevalent among groups of indigenous peoples, especially the faith in the power of the mother goddess and in the efficacy of fertility symbols. Hinduism, in the form comparable to its present-day expression, emerged at about the start of the Christian era, with an emphasis on the supremacy of the god Vishnu, the god Shiva, and the goddess Shakti (literally, “Power”).

The pluralism evident in Hinduism, as well as its acceptance of the existence of several deities, is often puzzling to non-Hindus. Hindus suggest that one may view the Infinite as a diamond of innumerable facets. One or another facet—be it Rama, Krishna, or Ganesha—may beckon an individual believer with irresistible magnetism. By acknowledging the power of an individual facet and worshipping it, the believer does not thereby deny the existence of many aspects of the Infinite and of varied paths toward the ultimate goal.

Deities are frequently portrayed with multiple arms, especially when they are engaged in combative acts of cosmic consequence that involve destroying powerful forces of evil. The multiplicity of arms emphasizes the immense power of the deity and his or her ability to perform several feats at the same time. The Indian artist found this a simple and an effective means of expressing the omnipresence and omnipotence of a deity. Demons are frequently portrayed with multiple heads to indicate their superhuman power. The occasional depiction of a deity with more than one head is generally motivated by the desire to portray varying aspects of the character of that deity. Thus, when the god Shiva is portrayed with a triple head, the central face indicates his essential character and the flanking faces depict his fierce and blissful aspects.

The Hindu Temple Architecture and sculpture are inextricably linked in India . Thus, if one speaks of Indian architecture without taking note of the lavish sculptured decoration with which monuments are covered, a partial and distorted picture is presented. In the Hindu temple , large niches in the three exterior walls of the sanctum house sculpted images that portray various aspects of the deity enshrined within. The sanctum image expresses the essence of the deity. For instance, the niches of a temple dedicated to a Vishnu may portray his incarnations; those of a temple to Shiva , his various combative feats; and those of a temple to the Great Goddess, her battles with various demons. Regional variations exist, too; in the eastern state of Odisha, for example, the niches of a temple to Shiva customarily contain images of his family—his consort, Parvati, and their sons, Ganesha, the god of overcoming obstacles, and warlike Skanda.

The exterior of the halls and porch are also covered with figural sculpture. A series of niches highlight events from the mythology of the enshrined deity, and frequently a place is set aside for a variety of other gods. In addition, temple walls feature repeated banks of scroll-like foliage, images of women, and loving couples known as mithunas . Signifying growth, abundance, and prosperity, they were considered auspicious motifs.

Dehejia, Vidya. “Hinduism and Hindu Art.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/hind/hd_hind.htm (February 2007)

Further Reading

Dehejia, Vidya. Indian Art . London: Phaidon, 1997.

Eck, Diana L. Darsan: Seeing the Divine Image in India. 2d ed . Chamberburg, Pa.: Anima Books, 1985.

Michell, George. The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to Its Meaning and Forms. Reprint . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

Mitter, Partha. Indian Art . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Additional Essays by Vidya Dehejia

- Dehejia, Vidya. “ Buddhism and Buddhist Art .” (February 2007)

- Dehejia, Vidya. “ Recognizing the Gods .” (February 2007)

- Dehejia, Vidya. “ South Asian Art and Culture .” (February 2007)

Related Essays

- Nepalese Painting

- Nepalese Sculpture

- Recognizing the Gods

- South Asian Art and Culture

- The Art of the Mughals before 1600

- Buddhism and Buddhist Art

- Early Modernists and Indian Traditions

- Europe and the Age of Exploration

- Jain Sculpture

- Kings of Brightness in Japanese Esoteric Buddhist Art

- Life of Jesus of Nazareth

- Modern Art in India

- The Mon-Dvaravati Tradition of Early North-Central Thailand

- Musical Instruments of the Indian Subcontinent

- Poetic Allusions in the Rajput and Pahari Painting of India

- Postmodernism: Recent Developments in Art in India

- Pre-Angkor Traditions: The Mekong Delta and Peninsular Thailand

- The Rise of Modernity in South Asia

- The Year One

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of South Asia

- Central and North Asia, 500–1000 A.D.

- Himalayan Region, 1400–1600 A.D.

- South Asia, 1400–1600 A.D.

- South Asia, 1–500 A.D.

- South Asia: North, 1000–1400 A.D.

- South Asia: North, 500–1000 A.D.

- South Asia: South, 1000–1400 A.D.

- South Asia: South, 500–1000 A.D.

- Southeast Asia, 1000–1400 A.D.

- Southeast Asia, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Southeast Asia, 500–1000 A.D.

- 10th Century A.D.

- 11th Century A.D.

- 12th Century A.D.

- 13th Century A.D.

- 14th Century A.D.

- 15th Century A.D.

- 16th Century A.D.

- 17th Century A.D.

- 18th Century A.D.

- 19th Century A.D.

- 1st Century A.D.

- 20th Century A.D.

- 21st Century A.D.

- 2nd Century A.D.

- 3rd Century A.D.

- 4th Century A.D.

- 5th Century A.D.

- 6th Century A.D.

- 7th Century A.D.

- 8th Century A.D.

- 9th Century A.D.

- Architecture

- Central and North Asia

- Christianity

- Deity / Religious Figure

- Floral Motif

- Gilt Copper

- Literature / Poetry

- Plant Motif

- Relief Sculpture

- Religious Art

- Sculpture in the Round

- Southeast Asia

- Uttar Pradesh

Online Features

- The Artist Project: “Izhar Patkin on Shiva as Lord of Dance “

- The Artist Project: “Nalini Malani on Hanuman Bearing the Mountaintop with Medicinal Herbs “

- Connections: “Hands” by Alice Schwarz

- Connections: “Relics” by John Guy

- Connections: “The Embrace” by Jennifer Meagher

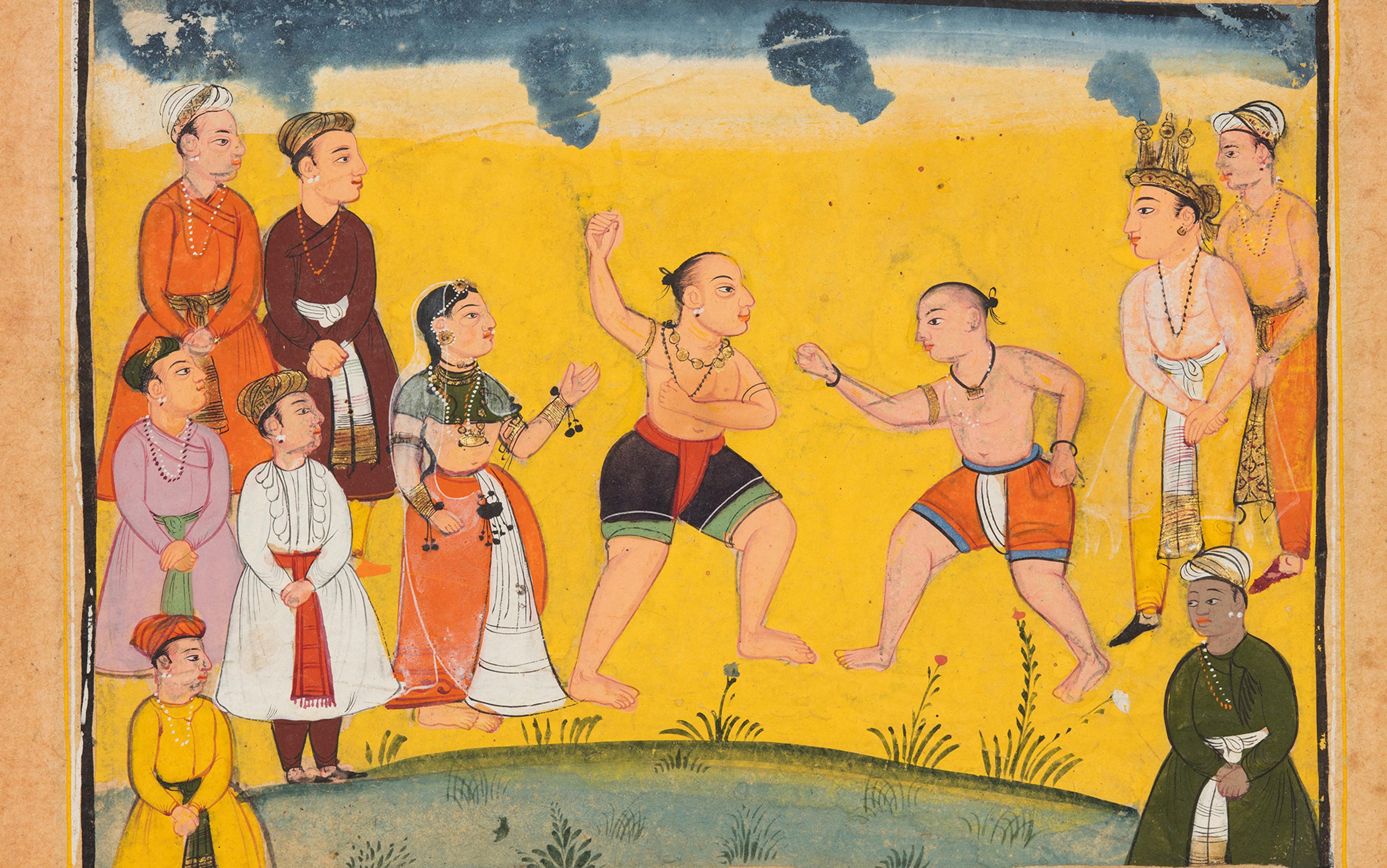

Bhima fighting with Jayadratha in a page from the Mahabharata ( c 1615), Popular Mughal School, probably done at Bikaner, India. Photo by Getty

The living Mahabharata

Immorality, sexism, politics, war: the polychromatic indian epic pulses with relevance to the present day.

by Audrey Truschke + BIO

The Mahabharata is a tale for our times. The plot of the ancient Indian epic centres around corrupt politics, ill-behaved men and warfare. In this dark tale, things get worse and worse, until an era of unprecedented depravity, the Kali Yuga, dawns. According to the Mahabharata , we’re still living in the horrific Kali era, which will unleash new horrors on us until the world ends.

The Mahabharata was first written down in Sanskrit, ancient India’s premier literary language, and ascribed to a poet named Vyasa about 2,000 years ago, give or take a few hundred years. The epic sought to catalogue and thereby criticise a new type of vicious politics enabled by the transition from a clan-based to a state-based society in northern India.

The work concerns two sets of cousins – the Pandavas and the Kauravas – who each claim the throne of Hastinapura as their own. In the first third of the epic, the splintered family dynasty tries to resolve their succession conflict in various ways, including gambling, trickery, murder and negotiation. But they fail. So, war breaks out, and the middle part of the Mahabharata tells of a near-total world conflict in which all the rules of battle are broken as each new atrocity exceeds the last. Among a battlefield of corpses, the Pandavas are the last ones left standing. In the final third of the epic, the Pandavas rule in a post-apocalyptic world until, years later, they too die.

From the moment that the Mahabharata was first written two millennia ago, people began to rework the epic to add new ideas that spoke to new circumstances. No two manuscripts are identical (there are thousands of handwritten Sanskrit copies), and the tale was recited as much or more often than it was read. Some of the most beloved parts of the Mahabharata today – such as that the elephant-headed Hindu god Ganesha wrote the epic with his broken tusk as he heard Vyasa’s narration – were added centuries after the story was first compiled.

The Mahabharata is long. It is roughly seven times the length of the Iliad and Odyssey combined, and 15 times the length of the Christian Bible. The plot covers multiple generations, and the text sometimes follows side stories for the length of a modern novel. But for all its narrative breadth and manifold asides, the Mahabharata can be accurately characterised as a set of narratives about vice.

Inequality and human suffering are facts of life in the Mahabharata . The work offers valuable perspectives and vantage points for reflecting on how various injustices play out in today’s world too.

T he Mahabharata claims to show dharma or righteous conduct – a guiding ideal of human life in Hindu thought – within the morass of the characters’ immoral behaviours. But the line between virtue and vice, dharma and adharma , is often muddled. The bad guys sometimes act more ethically than the good guys, who are themselves deeply flawed. In the epic’s polychromatic morality, the constraints of society and politics shackle all.

Bhishma, a common ancestor and grandfather-like figure to both sets of cousins, is a quintessential Mahabharata figure. Loyal to his family to a fault, he takes a vow of celibacy so that his father can marry a younger woman who wanted her children to inherit the throne. Bhishma’s motivation, namely love of his father, was good, but the result of denying himself children was to divert the line of succession to his younger brothers and, ultimately, their warring children. Appropriately, Bhishma’s name, adopted when he took his vow of celibacy, means ‘the terrible’ (before the vow, he was known as Devavrata, ‘devoted to the gods’). Bhishma remains devoted to his family even when they support the Kauravas, the bad guys, in the great war.

Sometimes even the gods act objectionably in the Mahabharata . Krishna, an incarnation of the Hindu god Vishnu, endorses dishonesty on more than one occasion. Even when Krishna advocates what the epic dubs dharma, the results can be hard to stomach. For example, when Arjuna, the third Pandava brother and their best warrior, hesitates to fight against his family and kill so many people, Krishna gives an eloquent speech that convinces him to plunge into battle.

Krishna’s discourse to Arjuna, known as the Bhagavadgita (‘Song of the Lord’), or Gita for short, is often read as a standalone work today, and revered by many across the world for its insights on morality and even nonviolence. In the 20th century, Mahatma Gandhi understood the Gita to support nonviolent resistance to colonial oppression. In the Mahabharata ’s plot, however, the Bhagavadgita rationalises mass slaughter.

What is the point of ruling when you got there only through deceit, sin and death?

‘Mahabharata’ translates as ‘great story of the Bharatas’, the Bharatas being the family lineage at the centre of the tale. However, in many modern Indian settings, ‘Mahabharata’ means a great battle. War is the narrative crux of the epic. The war that settles the succession dispute between the Pandavas and the Kauravas draws much of the world into its destructive whirlwind. Along with peoples from across the Indian subcontinent, Greeks, Persians and the Chinese also send troops to stand and fall in battle.

The Pandavas win, but at a magnificent cost of human life. The epic compels readers to imagine that human cost by describing the battle in excruciating, bloody detail over tens of thousands of verses. The Pandavas kill multiple members of their own family along the way, including elders who ought to be revered. Their victory is further soured by a night raid in which, on the last night of the war, the few remaining Kauravas creep into the slumbering Pandava camp and kill nearly everyone, including all the victors’ sons.

After the slaughter, when blood has soaked the earth and most of the characters lie dead, Yudhishthira, the eldest of the five Pandavas, decides that he no longer wants the throne of Hastinapura. What is the point of ruling when you got there only through deceit, sin and death? Yudhishthira says:

आत्मानमात्मना हत्वा किं धर्मफलमाप्नुमः धिगस्तु क्षात्रमाचारं धिगस्तु बलमौरसम् धिगस्त्वमर्षं येनेमामापदं गमिता वयम्

Since we slaughtered our own, what good can possibly come from ruling? Damn the ways of kings! Damn might makes right! Damn the turmoil that brought us to this disaster!

Yudhishthira’s fellow victors ultimately convince him to fulfil the duty to rule, regardless of his personal inclination to retire to the forest. In an attempt to address his numerous sharp objections, Bhishma – who lies dying on a bed of arrows – gives a prolix discourse on dharma in various circumstances, including in disasters. Still, for some readers, lingering doubt cannot but remain that Yudhishthira might be right to want to shun a bitter political victory.

The Mahabharata follows Yudhishthira’s reign for some years. It concludes with the demise of the five Pandava brothers and their wife Draupadi. In an unsettling twist, the six wind up visiting hell for a bit, en route to heaven. This detour calls the very core of dharma, righteousness, into question , again reminding us that the Mahabharata is an epic ordered by undercutting its own professed ethics.

In its philosophy and ethics, the Mahabharata proffers riches to its readers, in particular about the nature of human suffering as an ever-present challenge to any moral order. But how does the work measure up as literature? The work is considered to be kavya (poetry). In classical Sanskrit literary theory, each kavya ought to centre around a rasa , an aesthetic emotion, such as erotic love ( shringara ) or heroism ( vira ). But what aesthetic emotion might a tale of politics and pain, such as the Mahabharata , spark in readers?

Confounded by this question, one premodern Indian thinker suggested adding a ninth rasa to the line-up that might suit the Mahabharata : shanta , quiescence or turning away from the world. The idea is that, after perusing the vicious politics and violence endemic to the human condition as depicted in the Mahabharata , people would be disenchanted with earthly things and so renounce the world in favour of more spiritual pursuits, as Yudhishthira wished to.

T he Mahabharata condemns many of the appalling things it depicts, but one area where its response is more tepid concerns the treatment meted out to women. The story of Draupadi, the leading Pandava heroine, is the most well-known. Before the great war, her husband Yudhishthira gambles her away in a dice game, and Draupadi’s new owners, the Kauravas, strip and publicly assault her at their court. The Mahabharata condemns this event, but Draupadi’s notorious sharp tongue also undercuts the empathy many might have had for her.

After she is won at dice, Draupadi argues with her captors. First, she speaks up privately, from her quarters of the palace. Then, after being dragged into the Kauravas’ public audience hall, traditionally a male space, she advocates openly about how the situation is ‘a savage injustice’ ( adharmam ugraṃ ) that implicates all the elders present. Her self-assertion in a hall of men works. She convinces Dhritarashtra, the Kaurava king, to release her and eventually the rest of her family. But in a world favouring demure women, Draupadi’s willingness to speak about her suffering means that she has always carried a reputation as a shrew and a troublemaker.

Draupadi entered the Pandava family when Arjuna won her in a self-choice ceremony. In such ceremonies, the name notwithstanding, the woman is given as the prize to the victor of a contest. However, Draupadi ends up with five husbands, when Arjuna’s mother tells him – without looking over her shoulder to see that she is speaking about a female trophy rather than an inanimate one – to split his prize with his brothers. To make her words true, all five Pandavas marry Draupadi.

Nobody ever says that a bride should be like Draupadi, unless the goal is to curse the newlywed

Nobody ever asks Draupadi if she wanted polyandry, and the question has rarely interested readers. However, the Mahabharata offers further justifications for this unusual arrangement that blame Draupadi. For instance, in a prior life, Draupadi had asked for a husband with five qualities; unable to find a man who had all of them, Shiva gave her five husbands. She should not have asked for so much.