The Tech Edvocate

- Advertisement

- Home Page Five (No Sidebar)

- Home Page Four

- Home Page Three

- Home Page Two

- Icons [No Sidebar]

- Left Sidbear Page

- Lynch Educational Consulting

- My Speaking Page

- Newsletter Sign Up Confirmation

- Newsletter Unsubscription

- Page Example

- Privacy Policy

- Protected Content

- Request a Product Review

- Shortcodes Examples

- Terms and Conditions

- The Edvocate

- The Tech Edvocate Product Guide

- Write For Us

- Dr. Lynch’s Personal Website

- The Edvocate Podcast

- Assistive Technology

- Child Development Tech

- Early Childhood & K-12 EdTech

- EdTech Futures

- EdTech News

- EdTech Policy & Reform

- EdTech Startups & Businesses

- Higher Education EdTech

- Online Learning & eLearning

- Parent & Family Tech

- Personalized Learning

- Product Reviews

- Tech Edvocate Awards

- School Ratings

Keeping Yourself Safe in College: Everything You Need to Know

Myths about online high schools: everything you need to know, reasons you should study geography: everything you need to know, the vtoman jump 1800 portable power station: the best of the best, key roles of a school superintendent: everything you need to know, is earning a degree online worthwhile and beneficial, why learners cheat: everything you need to know, top issues in education: everything you need to know, duties of a school principal: everything you need to know, private vs. public education: everything you need to know, how to write an article review (with sample reviews) .

An article review is a critical evaluation of a scholarly or scientific piece, which aims to summarize its main ideas, assess its contributions, and provide constructive feedback. A well-written review not only benefits the author of the article under scrutiny but also serves as a valuable resource for fellow researchers and scholars. Follow these steps to create an effective and informative article review:

1. Understand the purpose: Before diving into the article, it is important to understand the intent of writing a review. This helps in focusing your thoughts, directing your analysis, and ensuring your review adds value to the academic community.

2. Read the article thoroughly: Carefully read the article multiple times to get a complete understanding of its content, arguments, and conclusions. As you read, take notes on key points, supporting evidence, and any areas that require further exploration or clarification.

3. Summarize the main ideas: In your review’s introduction, briefly outline the primary themes and arguments presented by the author(s). Keep it concise but sufficiently informative so that readers can quickly grasp the essence of the article.

4. Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses: In subsequent paragraphs, assess the strengths and limitations of the article based on factors such as methodology, quality of evidence presented, coherence of arguments, and alignment with existing literature in the field. Be fair and objective while providing your critique.

5. Discuss any implications: Deliberate on how this particular piece contributes to or challenges existing knowledge in its discipline. You may also discuss potential improvements for future research or explore real-world applications stemming from this study.

6. Provide recommendations: Finally, offer suggestions for both the author(s) and readers regarding how they can further build on this work or apply its findings in practice.

7. Proofread and revise: Once your initial draft is complete, go through it carefully for clarity, accuracy, and coherence. Revise as necessary, ensuring your review is both informative and engaging for readers.

Sample Review:

A Critical Review of “The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health”

Introduction:

“The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health” is a timely article which investigates the relationship between social media usage and psychological well-being. The authors present compelling evidence to support their argument that excessive use of social media can result in decreased self-esteem, increased anxiety, and a negative impact on interpersonal relationships.

Strengths and weaknesses:

One of the strengths of this article lies in its well-structured methodology utilizing a variety of sources, including quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews. This approach provides a comprehensive view of the topic, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of the effects of social media on mental health. However, it would have been beneficial if the authors included a larger sample size to increase the reliability of their conclusions. Additionally, exploring how different platforms may influence mental health differently could have added depth to the analysis.

Implications:

The findings in this article contribute significantly to ongoing debates surrounding the psychological implications of social media use. It highlights the potential dangers that excessive engagement with online platforms may pose to one’s mental well-being and encourages further research into interventions that could mitigate these risks. The study also offers an opportunity for educators and policy-makers to take note and develop strategies to foster healthier online behavior.

Recommendations:

Future researchers should consider investigating how specific social media platforms impact mental health outcomes, as this could lead to more targeted interventions. For practitioners, implementing educational programs aimed at promoting healthy online habits may be beneficial in mitigating the potential negative consequences associated with excessive social media use.

Conclusion:

Overall, “The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health” is an important and informative piece that raises awareness about a pressing issue in today’s digital age. Given its minor limitations, it provides valuable

3 Ways to Make a Mini Greenhouse ...

3 ways to teach yourself to play ....

Matthew Lynch

Related articles more from author.

4 Ways to Stretch a Hat

4 Ways to Put Your Hair Up with a Jaw Clip

How to Do Acrylic Nails: 15 Steps

How to Make a Light Bulb

13 Simple Ways to Tell if a Taurus Man Likes You

How to Turn a Log Into a Planter

How to Write an Article Review: Template & Examples

An article review is an academic assignment that invites you to study a piece of academic research closely. Then, you should present its summary and critically evaluate it using the knowledge you’ve gained in class and during your independent study. If you get such a task at college or university, you shouldn’t confuse it with a response paper, which is a distinct assignment with other purposes (we’ll talk about it in detail below).

Our specialists will write a custom essay specially for you!

In this article, prepared by Custom-Writing experts, you’ll find:

- the intricacies of article review writing;

- the difference between an article review and similar assignments;

- a step-by-step algorithm for review composition;

- a couple of samples to guide you throughout the writing process.

So, if you wish to study our article review example and discover helpful writing tips, keep reading.

❓ What Is an Article Review?

- ✍️ Writing Steps

📑 Article Review Format

🔗 references.

An article review is an academic paper that summarizes and critically evaluates the information presented in your selected article.

The first thing you should note when approaching the task of an article review is that not every article is suitable for this assignment. Let’s have a look at the variety of articles to understand what you can choose from.

Popular Vs. Scholarly Articles

In most cases, you’ll be required to review a scholarly, peer-reviewed article – one composed in compliance with rigorous academic standards. Yet, the Web is also full of popular articles that don’t present original scientific value and shouldn’t be selected for a review.

Just in 1 hour! We will write you a plagiarism-free paper in hardly more than 1 hour

Not sure how to distinguish these two types? Here is a comparative table to help you out.

Article Review vs. Response Paper

Now, let’s consider the difference between an article review and a response paper:

- If you’re assigned to critique a scholarly article , you will need to compose an article review .

- If your subject of analysis is a popular article , you can respond to it with a well-crafted response paper .

The reason for such distinctions is the quality and structure of these two article types. Peer-reviewed, scholarly articles have clear-cut quality criteria, allowing you to conduct and present a structured assessment of the assigned material. Popular magazines have loose or non-existent quality criteria and don’t offer an opportunity for structured evaluation. So, they are only fit for a subjective response, in which you can summarize your reactions and emotions related to the reading material.

All in all, you can structure your response assignments as outlined in the tips below.

✍️ How to Write an Article Review: Step by Step

Here is a tried and tested algorithm for article review writing from our experts. We’ll consider only the critical review variety of this academic assignment. So, let’s get down to the stages you need to cover to get a stellar review.

Receive a plagiarism-free paper tailored to your instructions. Cut 15% off your first order!

Read the Article

As with any reviews, reports, and critiques, you must first familiarize yourself with the assigned material. It’s impossible to review something you haven’t read, so set some time for close, careful reading of the article to identify:

- The author’s main points and message.

- The arguments they use to prove their points.

- The methodology they use to approach the subject.

In terms of research type , your article will usually belong to one of three types explained below.

Summarize the Article

Now that you’ve read the text and have a general impression of the content, it’s time to summarize it for your readers. Look into the article’s text closely to determine:

- The thesis statement , or general message of the author.

- Research question, purpose, and context of research.

- Supporting points for the author’s assumptions and claims.

- Major findings and supporting evidence.

As you study the article thoroughly, make notes on the margins or write these elements out on a sheet of paper. You can also apply a different technique: read the text section by section and formulate its gist in one phrase or sentence. Once you’re done, you’ll have a summary skeleton in front of you.

Evaluate the Article

The next step of review is content evaluation. Keep in mind that various research types will require a different set of review questions. Here is a complete list of evaluation points you can include.

Get an originally-written paper according to your instructions!

Write the Text

After completing the critical review stage, it’s time to compose your article review.

The format of this assignment is standard – you will have an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. The introduction should present your article and summarize its content. The body will contain a structured review according to all four dimensions covered in the previous section. The concluding part will typically recap all the main points you’ve identified during your assessment.

It is essential to note that an article review is, first of all, an academic assignment. Therefore, it should follow all rules and conventions of academic composition, such as:

- No contractions . Don’t use short forms, such as “don’t,” “can’t,” “I’ll,” etc. in academic writing. You need to spell out all those words.

- Formal language and style . Avoid conversational phrasing and words that you would naturally use in blog posts or informal communication. For example, don’t use words like “pretty,” “kind of,” and “like.”

- Third-person narrative . Academic reviews should be written from the third-person point of view, avoiding statements like “I think,” “in my opinion,” and so on.

- No conversational forms . You shouldn’t turn to your readers directly in the text by addressing them with the pronoun “you.” It’s vital to keep the narrative neutral and impersonal.

- Proper abbreviation use . Consult the list of correct abbreviations , like “e.g.” or “i.e.,” for use in your academic writing. If you use informal abbreviations like “FYA” or “f.i.,” your professor will reduce the grade.

- Complete sentences . Make sure your sentences contain the subject and the predicate; avoid shortened or sketch-form phrases suitable for a draft only.

- No conjunctions at the beginning of a sentence . Remember the FANBOYS rule – don’t start a sentence with words like “and” or “but.” They often seem the right way to build a coherent narrative, but academic writing rules disfavor such usage.

- No abbreviations or figures at the beginning of a sentence . Never start a sentence with a number — spell it out if you need to use it anyway. Besides, sentences should never begin with abbreviations like “e.g.”

Finally, a vital rule for an article review is properly formatting the citations. We’ll discuss the correct use of citation styles in the following section.

When composing an article review, keep these points in mind:

- Start with a full reference to the reviewed article so the reader can locate it quickly.

- Ensure correct formatting of in-text references.

- Provide a complete list of used external sources on the last page of the review – your bibliographical entries .

You’ll need to understand the rules of your chosen citation style to meet all these requirements. Below, we’ll discuss the two most common referencing styles – APA and MLA.

Article Review in APA

When you need to compose an article review in the APA format , here is the general bibliographical entry format you should use for journal articles on your reference page:

- Author’s last name, First initial. Middle initial. (Year of Publication). Name of the article. Name of the Journal, volume (number), pp. #-#. https://doi.org/xx.xxx/yyyy

Horigian, V. E., Schmidt, R. D., & Feaster, D. J. (2021). Loneliness, mental health, and substance use among US young adults during COVID-19. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 53 (1), pp. 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2020.1836435

Your in-text citations should follow the author-date format like this:

- If you paraphrase the source and mention the author in the text: According to Horigian et al. (2021), young adults experienced increased levels of loneliness, depression, and anxiety during the pandemic.

- If you paraphrase the source and don’t mention the author in the text: Young adults experienced increased levels of loneliness, depression, and anxiety during the pandemic (Horigian et al., 2021).

- If you quote the source: As Horigian et al. (2021) point out, there were “elevated levels of loneliness, depression, anxiety, alcohol use, and drug use among young adults during COVID-19” (p. 6).

Note that your in-text citations should include “et al.,” as in the examples above, if your article has 3 or more authors. If you have one or two authors, your in-text citations would look like this:

- One author: “According to Smith (2020), depression is…” or “Depression is … (Smith, 2020).”

- Two authors: “According to Smith and Brown (2020), anxiety means…” or “Anxiety means (Smith & Brown, 2020).”

Finally, in case you have to review a book or a website article, here are the general formats for citing these source types on your APA reference list.

Article Review in MLA

If your assignment requires MLA-format referencing, here’s the general format you should use for citing journal articles on your Works Cited page:

- Author’s last name, First name. “Title of an Article.” Title of the Journal , vol. #, no. #, year, pp. #-#.

Horigian, Viviana E., et al. “Loneliness, Mental Health, and Substance Use Among US Young Adults During COVID-19.” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs , vol. 53, no. 1, 2021, pp. 1-9.

In-text citations in the MLA format follow the author-page citation format and look like this:

- According to Horigian et al., young adults experienced increased levels of loneliness, depression, and anxiety during the pandemic (6).

- Young adults experienced increased levels of loneliness, depression, and anxiety during the pandemic (Horigian et al. 6).

Like in APA, the abbreviation “et al.” is only needed in MLA if your article has 3 or more authors.

If you need to cite a book or a website page, here are the general MLA formats for these types of sources.

✅ Article Review Template

Here is a handy, universal article review template to help you move on with any review assignment. We’ve tried to make it as generic as possible to guide you in the academic process.

📝 Article Review Examples

The theory is good, but practice is even better. Thus, we’ve created three brief examples to show you how to write an article review. You can study the full-text samples by following the links.

📃 Men, Women, & Money

This article review examines a famous piece, “Men, Women & Money – How the Sexes Differ with Their Finances,” published by Amy Livingston in 2020. The author of this article claims that men generally spend more money than women. She makes this conclusion from a close analysis of gender-specific expenditures across five main categories: food, clothing, cars, entertainment, and general spending patterns. Livingston also looks at men’s approach to saving to argue that counter to the common perception of women’s light-hearted attitude to money, men are those who spend more on average.

📃 When and Why Nationalism Beats Globalism

This is a review of Jonathan Heidt’s 2016 article titled “When and Why Nationalism Beats Globalism,” written as an advocacy of right-wing populism rising in many Western states. The author illustrates the case with the election of Donald Trump as the US President and the rise of right-wing rhetoric in many Western countries. These examples show how nationalist sentiment represents a reaction to global immigration and a failure of globalization.

📃 Sleep Deprivation

This is a review of the American Heart Association’s article titled “The Dangers of Sleep Deprivation.” It discusses how the national organization concerned with the American population’s cardiovascular health links the lack of high-quality sleep to far-reaching health consequences. The organization’s experts reveal how a consistent lack of sleep leads to Alzheimer’s disease development, obesity, type 2 diabetes, etc.

✏️ Article Review FAQ

A high-quality article review should summarize the assigned article’s content and offer data-backed reactions and evaluations of its quality in terms of the article’s purpose, methodology, and data used to argue the main points. It should be detailed, comprehensive, objective, and evidence-based.

The purpose of writing a review is to allow students to reflect on research quality and showcase their critical thinking and evaluation skills. Students should exhibit their mastery of close reading of research publications and their unbiased assessment.

The content of your article review will be the same in any format, with the only difference in the assignment’s formatting before submission. Ensure you have a separate title page made according to APA standards and cite sources using the parenthetical author-date referencing format.

You need to take a closer look at various dimensions of an assigned article to compose a valuable review. Study the author’s object of analysis, the purpose of their research, the chosen method, data, and findings. Evaluate all these dimensions critically to see whether the author has achieved the initial goals. Finally, offer improvement recommendations to add a critique aspect to your paper.

- Scientific Article Review: Duke University

- Book and Article Reviews: William & Mary, Writing Resources Center

- Sample Format for Reviewing a Journal Article: Boonshoft School of Medicine

- Research Paper Review – Structure and Format Guidelines: New Jersey Institute of Technology

- Article Review: University of Waterloo

- Article Review: University of South Australia

- How to Write a Journal Article Review: University of Newcastle Library Guides

- Writing Help: The Article Review: Central Michigan University Libraries

- Write a Critical Review of a Scientific Journal Article: McLaughlin Library

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

Short essays answer a specific question on the subject. They usually are anywhere between 250 words and 750 words long. A paper with less than 250 words isn’t considered a finished text, so it doesn’t fall under the category of a short essay. Essays of such format are required for...

High school and college students often face challenges when crafting a compare-and-contrast essay. A well-written paper of this kind needs to be structured appropriately to earn you good grades. Knowing how to organize your ideas allows you to present your ideas in a coherent and logical manner This article by...

If you’re a student, you’ve heard about a formal essay: a factual, research-based paper written in 3rd person. Most students have to produce dozens of them during their educational career. Writing a formal essay may not be the easiest task. But fear not: our custom-writing team is here to guide...

Narrative essays are unlike anything you wrote throughout your academic career. Instead of writing a formal paper, you need to tell a story. Familiar elements such as evidence and arguments are replaced with exposition and character development. The importance of writing an outline for an essay like this is hard...

A précis is a brief synopsis of a written piece. It is used to summarize and analyze a text’s main points. If you need to write a précis for a research paper or the AP Lang exam, you’ve come to the right place. In this comprehensive guide by Custom-Writing.org, you’ll...

A synthesis essay requires you to work with multiple sources. You combine the information gathered from them to present a well-rounded argument on a topic. Are you looking for the ultimate guide on synthesis essay writing? You’ve come to the right place! In this guide by our custom writing team,...

Do you know how to make your essay stand out? One of the easiest ways is to start your introduction with a catchy hook. A hook is a phrase or a sentence that helps to grab the reader’s attention. After reading this article by Custom-Writing.org, you will be able to...

Critical thinking is the process of evaluating and analyzing information. People who use it in everyday life are open to different opinions. They rely on reason and logic when making conclusions about certain issues. A critical thinking essay shows how your thoughts change as you research your topic. This type...

Process analysis is an explanation of how something works or happens. Want to know more? Read the following article prepared by our custom writing specialists and learn about: process analysis and its typesa process analysis outline tipsfree examples and other tips that might be helpful for your college assignment So,...

A visual analysis essay is an academic paper type that history and art students often deal with. It consists of a detailed description of an image or object. It can also include an interpretation or an argument that is supported by visual evidence. In this article, our custom writing experts...

Want to know how to write a reflection paper for college or school? To do that, you need to connect your personal experiences with theoretical knowledge. Usually, students are asked to reflect on a documentary, a text, or their experience. Sometimes one needs to write a paper about a lesson...

A character analysis is an examination of the personalities and actions of protagonists and antagonists that make up a story. It discusses their role in the story, evaluates their traits, and looks at their conflicts and experiences. You might need to write this assignment in school or college. Like any...

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Critical Reviews

How to Write an Article Review (With Examples)

Last Updated: April 24, 2024 Fact Checked

Preparing to Write Your Review

Writing the article review, sample article reviews, expert q&a.

This article was co-authored by Jake Adams . Jake Adams is an academic tutor and the owner of Simplifi EDU, a Santa Monica, California based online tutoring business offering learning resources and online tutors for academic subjects K-College, SAT & ACT prep, and college admissions applications. With over 14 years of professional tutoring experience, Jake is dedicated to providing his clients the very best online tutoring experience and access to a network of excellent undergraduate and graduate-level tutors from top colleges all over the nation. Jake holds a BS in International Business and Marketing from Pepperdine University. There are 12 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 3,102,196 times.

An article review is both a summary and an evaluation of another writer's article. Teachers often assign article reviews to introduce students to the work of experts in the field. Experts also are often asked to review the work of other professionals. Understanding the main points and arguments of the article is essential for an accurate summation. Logical evaluation of the article's main theme, supporting arguments, and implications for further research is an important element of a review . Here are a few guidelines for writing an article review.

Education specialist Alexander Peterman recommends: "In the case of a review, your objective should be to reflect on the effectiveness of what has already been written, rather than writing to inform your audience about a subject."

Article Review 101

- Read the article very closely, and then take time to reflect on your evaluation. Consider whether the article effectively achieves what it set out to.

- Write out a full article review by completing your intro, summary, evaluation, and conclusion. Don't forget to add a title, too!

- Proofread your review for mistakes (like grammar and usage), while also cutting down on needless information.

- Article reviews present more than just an opinion. You will engage with the text to create a response to the scholarly writer's ideas. You will respond to and use ideas, theories, and research from your studies. Your critique of the article will be based on proof and your own thoughtful reasoning.

- An article review only responds to the author's research. It typically does not provide any new research. However, if you are correcting misleading or otherwise incorrect points, some new data may be presented.

- An article review both summarizes and evaluates the article.

- Summarize the article. Focus on the important points, claims, and information.

- Discuss the positive aspects of the article. Think about what the author does well, good points she makes, and insightful observations.

- Identify contradictions, gaps, and inconsistencies in the text. Determine if there is enough data or research included to support the author's claims. Find any unanswered questions left in the article.

- Make note of words or issues you don't understand and questions you have.

- Look up terms or concepts you are unfamiliar with, so you can fully understand the article. Read about concepts in-depth to make sure you understand their full context.

- Pay careful attention to the meaning of the article. Make sure you fully understand the article. The only way to write a good article review is to understand the article.

- With either method, make an outline of the main points made in the article and the supporting research or arguments. It is strictly a restatement of the main points of the article and does not include your opinions.

- After putting the article in your own words, decide which parts of the article you want to discuss in your review. You can focus on the theoretical approach, the content, the presentation or interpretation of evidence, or the style. You will always discuss the main issues of the article, but you can sometimes also focus on certain aspects. This comes in handy if you want to focus the review towards the content of a course.

- Review the summary outline to eliminate unnecessary items. Erase or cross out the less important arguments or supplemental information. Your revised summary can serve as the basis for the summary you provide at the beginning of your review.

- What does the article set out to do?

- What is the theoretical framework or assumptions?

- Are the central concepts clearly defined?

- How adequate is the evidence?

- How does the article fit into the literature and field?

- Does it advance the knowledge of the subject?

- How clear is the author's writing? Don't: include superficial opinions or your personal reaction. Do: pay attention to your biases, so you can overcome them.

- For example, in MLA , a citation may look like: Duvall, John N. "The (Super)Marketplace of Images: Television as Unmediated Mediation in DeLillo's White Noise ." Arizona Quarterly 50.3 (1994): 127-53. Print. [9] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- For example: The article, "Condom use will increase the spread of AIDS," was written by Anthony Zimmerman, a Catholic priest.

- Your introduction should only be 10-25% of your review.

- End the introduction with your thesis. Your thesis should address the above issues. For example: Although the author has some good points, his article is biased and contains some misinterpretation of data from others’ analysis of the effectiveness of the condom.

- Use direct quotes from the author sparingly.

- Review the summary you have written. Read over your summary many times to ensure that your words are an accurate description of the author's article.

- Support your critique with evidence from the article or other texts.

- The summary portion is very important for your critique. You must make the author's argument clear in the summary section for your evaluation to make sense.

- Remember, this is not where you say if you liked the article or not. You are assessing the significance and relevance of the article.

- Use a topic sentence and supportive arguments for each opinion. For example, you might address a particular strength in the first sentence of the opinion section, followed by several sentences elaborating on the significance of the point.

- This should only be about 10% of your overall essay.

- For example: This critical review has evaluated the article "Condom use will increase the spread of AIDS" by Anthony Zimmerman. The arguments in the article show the presence of bias, prejudice, argumentative writing without supporting details, and misinformation. These points weaken the author’s arguments and reduce his credibility.

- Make sure you have identified and discussed the 3-4 key issues in the article.

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://libguides.cmich.edu/writinghelp/articlereview

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548566/

- ↑ Jake Adams. Academic Tutor & Test Prep Specialist. Expert Interview. 24 July 2020.

- ↑ https://guides.library.queensu.ca/introduction-research/writing/critical

- ↑ https://www.iup.edu/writingcenter/writing-resources/organization-and-structure/creating-an-outline.html

- ↑ https://writing.umn.edu/sws/assets/pdf/quicktips/titles.pdf

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/mla_style/mla_formatting_and_style_guide/mla_works_cited_periodicals.html

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548565/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/593/2014/06/How_to_Summarize_a_Research_Article1.pdf

- ↑ https://www.uis.edu/learning-hub/writing-resources/handouts/learning-hub/how-to-review-a-journal-article

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/editing-and-proofreading/

About This Article

If you have to write an article review, read through the original article closely, taking notes and highlighting important sections as you read. Next, rewrite the article in your own words, either in a long paragraph or as an outline. Open your article review by citing the article, then write an introduction which states the article’s thesis. Next, summarize the article, followed by your opinion about whether the article was clear, thorough, and useful. Finish with a paragraph that summarizes the main points of the article and your opinions. To learn more about what to include in your personal critique of the article, keep reading the article! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Prince Asiedu-Gyan

Apr 22, 2022

Did this article help you?

Sammy James

Sep 12, 2017

Juabin Matey

Aug 30, 2017

Vanita Meghrajani

Jul 21, 2016

Nov 27, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

How to Write an Article Review: Tips and Examples

Did you know that article reviews are not just academic exercises but also a valuable skill in today's information age? In a world inundated with content, being able to dissect and evaluate articles critically can help you separate the wheat from the chaff. Whether you're a student aiming to excel in your coursework or a professional looking to stay well-informed, mastering the art of writing article reviews is an invaluable skill.

Short Description

In this article, our research paper writing service experts will start by unraveling the concept of article reviews and discussing the various types. You'll also gain insights into the art of formatting your review effectively. To ensure you're well-prepared, we'll take you through the pre-writing process, offering tips on setting the stage for your review. But it doesn't stop there. You'll find a practical example of an article review to help you grasp the concepts in action. To complete your journey, we'll guide you through the post-writing process, equipping you with essential proofreading techniques to ensure your work shines with clarity and precision!

What Is an Article Review: Grasping the Concept

A review article is a type of professional paper writing that demands a high level of in-depth analysis and a well-structured presentation of arguments. It is a critical, constructive evaluation of literature in a particular field through summary, classification, analysis, and comparison.

If you write a scientific review, you have to use database searches to portray the research. Your primary goal is to summarize everything and present a clear understanding of the topic you've been working on.

Writing Involves:

- Summarization, classification, analysis, critiques, and comparison.

- The analysis, evaluation, and comparison require the use of theories, ideas, and research relevant to the subject area of the article.

- It is also worth nothing if a review does not introduce new information, but instead presents a response to another writer's work.

- Check out other samples to gain a better understanding of how to review the article.

Types of Review

When it comes to article reviews, there's more than one way to approach the task. Understanding the various types of reviews is like having a versatile toolkit at your disposal. In this section, we'll walk you through the different dimensions of review types, each offering a unique perspective and purpose. Whether you're dissecting a scholarly article, critiquing a piece of literature, or evaluating a product, you'll discover the diverse landscape of article reviews and how to navigate it effectively.

.webp)

Journal Article Review

Just like other types of reviews, a journal article review assesses the merits and shortcomings of a published work. To illustrate, consider a review of an academic paper on climate change, where the writer meticulously analyzes and interprets the article's significance within the context of environmental science.

Research Article Review

Distinguished by its focus on research methodologies, a research article review scrutinizes the techniques used in a study and evaluates them in light of the subsequent analysis and critique. For instance, when reviewing a research article on the effects of a new drug, the reviewer would delve into the methods employed to gather data and assess their reliability.

Science Article Review

In the realm of scientific literature, a science article review encompasses a wide array of subjects. Scientific publications often provide extensive background information, which can be instrumental in conducting a comprehensive analysis. For example, when reviewing an article about the latest breakthroughs in genetics, the reviewer may draw upon the background knowledge provided to facilitate a more in-depth evaluation of the publication.

Need a Hand From Professionals?

Address to Our Writers and Get Assistance in Any Questions!

Formatting an Article Review

The format of the article should always adhere to the citation style required by your professor. If you're not sure, seek clarification on the preferred format and ask him to clarify several other pointers to complete the formatting of an article review adequately.

How Many Publications Should You Review?

- In what format should you cite your articles (MLA, APA, ASA, Chicago, etc.)?

- What length should your review be?

- Should you include a summary, critique, or personal opinion in your assignment?

- Do you need to call attention to a theme or central idea within the articles?

- Does your instructor require background information?

When you know the answers to these questions, you may start writing your assignment. Below are examples of MLA and APA formats, as those are the two most common citation styles.

Using the APA Format

Articles appear most commonly in academic journals, newspapers, and websites. If you write an article review in the APA format, you will need to write bibliographical entries for the sources you use:

- Web : Author [last name], A.A [first and middle initial]. (Year, Month, Date of Publication). Title. Retrieved from {link}

- Journal : Author [last name], A.A [first and middle initial]. (Publication Year). Publication Title. Periodical Title, Volume(Issue), pp.-pp.

- Newspaper : Author [last name], A.A [first and middle initial]. (Year, Month, Date of Publication). Publication Title. Magazine Title, pp. xx-xx.

Using MLA Format

- Web : Last, First Middle Initial. “Publication Title.” Website Title. Website Publisher, Date Month Year Published. Web. Date Month Year Accessed.

- Newspaper : Last, First M. “Publication Title.” Newspaper Title [City] Date, Month, Year Published: Page(s). Print.

- Journal : Last, First M. “Publication Title.” Journal Title Series Volume. Issue (Year Published): Page(s). Database Name. Web. Date Month Year Accessed.

Enhance your writing effortlessly with EssayPro.com , where you can order an article review or any other writing task. Our team of expert writers specializes in various fields, ensuring your work is not just summarized, but deeply analyzed and professionally presented. Ideal for students and professionals alike, EssayPro offers top-notch writing assistance tailored to your needs. Elevate your writing today with our skilled team at your article review writing service !

.jpg)

The Pre-Writing Process

Facing this task for the first time can really get confusing and can leave you unsure of where to begin. To create a top-notch article review, start with a few preparatory steps. Here are the two main stages from our dissertation services to get you started:

Step 1: Define the right organization for your review. Knowing the future setup of your paper will help you define how you should read the article. Here are the steps to follow:

- Summarize the article — seek out the main points, ideas, claims, and general information presented in the article.

- Define the positive points — identify the strong aspects, ideas, and insightful observations the author has made.

- Find the gaps —- determine whether or not the author has any contradictions, gaps, or inconsistencies in the article and evaluate whether or not he or she used a sufficient amount of arguments and information to support his or her ideas.

- Identify unanswered questions — finally, identify if there are any questions left unanswered after reading the piece.

Step 2: Move on and review the article. Here is a small and simple guide to help you do it right:

- Start off by looking at and assessing the title of the piece, its abstract, introductory part, headings and subheadings, opening sentences in its paragraphs, and its conclusion.

- First, read only the beginning and the ending of the piece (introduction and conclusion). These are the parts where authors include all of their key arguments and points. Therefore, if you start with reading these parts, it will give you a good sense of the author's main points.

- Finally, read the article fully.

These three steps make up most of the prewriting process. After you are done with them, you can move on to writing your own review—and we are going to guide you through the writing process as well.

Outline and Template

As you progress with reading your article, organize your thoughts into coherent sections in an outline. As you read, jot down important facts, contributions, or contradictions. Identify the shortcomings and strengths of your publication. Begin to map your outline accordingly.

If your professor does not want a summary section or a personal critique section, then you must alleviate those parts from your writing. Much like other assignments, an article review must contain an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. Thus, you might consider dividing your outline according to these sections as well as subheadings within the body. If you find yourself troubled with the pre-writing and the brainstorming process for this assignment, seek out a sample outline.

Your custom essay must contain these constituent parts:

- Pre-Title Page - Before diving into your review, start with essential details: article type, publication title, and author names with affiliations (position, department, institution, location, and email). Include corresponding author info if needed.

- Running Head - In APA format, use a concise title (under 40 characters) to ensure consistent formatting.

- Summary Page - Optional but useful. Summarize the article in 800 words, covering background, purpose, results, and methodology, avoiding verbatim text or references.

- Title Page - Include the full title, a 250-word abstract, and 4-6 keywords for discoverability.

- Introduction - Set the stage with an engaging overview of the article.

- Body - Organize your analysis with headings and subheadings.

- Works Cited/References - Properly cite all sources used in your review.

- Optional Suggested Reading Page - If permitted, suggest further readings for in-depth exploration.

- Tables and Figure Legends (if instructed by the professor) - Include visuals when requested by your professor for clarity.

Example of an Article Review

You might wonder why we've dedicated a section of this article to discuss an article review sample. Not everyone may realize it, but examining multiple well-constructed examples of review articles is a crucial step in the writing process. In the following section, our essay writing service experts will explain why.

Looking through relevant article review examples can be beneficial for you in the following ways:

- To get you introduced to the key works of experts in your field.

- To help you identify the key people engaged in a particular field of science.

- To help you define what significant discoveries and advances were made in your field.

- To help you unveil the major gaps within the existing knowledge of your field—which contributes to finding fresh solutions.

- To help you find solid references and arguments for your own review.

- To help you generate some ideas about any further field of research.

- To help you gain a better understanding of the area and become an expert in this specific field.

- To get a clear idea of how to write a good review.

View Our Writer’s Sample Before Crafting Your Own!

Why Have There Been No Great Female Artists?

Steps for Writing an Article Review

Here is a guide with critique paper format on how to write a review paper:

.webp)

Step 1: Write the Title

First of all, you need to write a title that reflects the main focus of your work. Respectively, the title can be either interrogative, descriptive, or declarative.

Step 2: Cite the Article

Next, create a proper citation for the reviewed article and input it following the title. At this step, the most important thing to keep in mind is the style of citation specified by your instructor in the requirements for the paper. For example, an article citation in the MLA style should look as follows:

Author's last and first name. "The title of the article." Journal's title and issue(publication date): page(s). Print

Abraham John. "The World of Dreams." Virginia Quarterly 60.2(1991): 125-67. Print.

Step 3: Article Identification

After your citation, you need to include the identification of your reviewed article:

- Title of the article

- Title of the journal

- Year of publication

All of this information should be included in the first paragraph of your paper.

The report "Poverty increases school drop-outs" was written by Brian Faith – a Health officer – in 2000.

Step 4: Introduction

Your organization in an assignment like this is of the utmost importance. Before embarking on your writing process, you should outline your assignment or use an article review template to organize your thoughts coherently.

- If you are wondering how to start an article review, begin with an introduction that mentions the article and your thesis for the review.

- Follow up with a summary of the main points of the article.

- Highlight the positive aspects and facts presented in the publication.

- Critique the publication by identifying gaps, contradictions, disparities in the text, and unanswered questions.

Step 5: Summarize the Article

Make a summary of the article by revisiting what the author has written about. Note any relevant facts and findings from the article. Include the author's conclusions in this section.

Step 6: Critique It

Present the strengths and weaknesses you have found in the publication. Highlight the knowledge that the author has contributed to the field. Also, write about any gaps and/or contradictions you have found in the article. Take a standpoint of either supporting or not supporting the author's assertions, but back up your arguments with facts and relevant theories that are pertinent to that area of knowledge. Rubrics and templates can also be used to evaluate and grade the person who wrote the article.

Step 7: Craft a Conclusion

In this section, revisit the critical points of your piece, your findings in the article, and your critique. Also, write about the accuracy, validity, and relevance of the results of the article review. Present a way forward for future research in the field of study. Before submitting your article, keep these pointers in mind:

- As you read the article, highlight the key points. This will help you pinpoint the article's main argument and the evidence that they used to support that argument.

- While you write your review, use evidence from your sources to make a point. This is best done using direct quotations.

- Select quotes and supporting evidence adequately and use direct quotations sparingly. Take time to analyze the article adequately.

- Every time you reference a publication or use a direct quotation, use a parenthetical citation to avoid accidentally plagiarizing your article.

- Re-read your piece a day after you finish writing it. This will help you to spot grammar mistakes and to notice any flaws in your organization.

- Use a spell-checker and get a second opinion on your paper.

The Post-Writing Process: Proofread Your Work

Finally, when all of the parts of your article review are set and ready, you have one last thing to take care of — proofreading. Although students often neglect this step, proofreading is a vital part of the writing process and will help you polish your paper to ensure that there are no mistakes or inconsistencies.

To proofread your paper properly, start by reading it fully and checking the following points:

- Punctuation

- Other mistakes

Afterward, take a moment to check for any unnecessary information in your paper and, if found, consider removing it to streamline your content. Finally, double-check that you've covered at least 3-4 key points in your discussion.

And remember, if you ever need help with proofreading, rewriting your essay, or even want to buy essay , our friendly team is always here to assist you.

Need an Article REVIEW WRITTEN?

Just send us the requirements to your paper and watch one of our writers crafting an original paper for you.

What Is A Review Article?

How to write an article review, how to write an article review in apa format, related articles.

%20(3).webp)

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- CME Reviews

- Best of 2021 collection

- Abbreviated Breast MRI Virtual Collection

- Contrast-enhanced Mammography Collection

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Accepted Papers Resource Guide

- About Journal of Breast Imaging

- About the Society of Breast Imaging

- Guidelines for Reviewers

- Resources for Reviewers and Authors

- Editorial Board

- Advertising Disclaimer

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Scientific Review Article

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Manisha Bahl, A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Scientific Review Article, Journal of Breast Imaging , Volume 5, Issue 4, July/August 2023, Pages 480–485, https://doi.org/10.1093/jbi/wbad028

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Scientific review articles are comprehensive, focused reviews of the scientific literature written by subject matter experts. The task of writing a scientific review article can seem overwhelming; however, it can be managed by using an organized approach and devoting sufficient time to the process. The process involves selecting a topic about which the authors are knowledgeable and enthusiastic, conducting a literature search and critical analysis of the literature, and writing the article, which is composed of an abstract, introduction, body, and conclusion, with accompanying tables and figures. This article, which focuses on the narrative or traditional literature review, is intended to serve as a guide with practical steps for new writers. Tips for success are also discussed, including selecting a focused topic, maintaining objectivity and balance while writing, avoiding tedious data presentation in a laundry list format, moving from descriptions of the literature to critical analysis, avoiding simplistic conclusions, and budgeting time for the overall process.

- narrative discourse

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Librarian

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2631-6129

- Print ISSN 2631-6110

- Copyright © 2024 Society of Breast Imaging

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

How to Write a Peer Review

When you write a peer review for a manuscript, what should you include in your comments? What should you leave out? And how should the review be formatted?

This guide provides quick tips for writing and organizing your reviewer report.

Review Outline

Use an outline for your reviewer report so it’s easy for the editors and author to follow. This will also help you keep your comments organized.

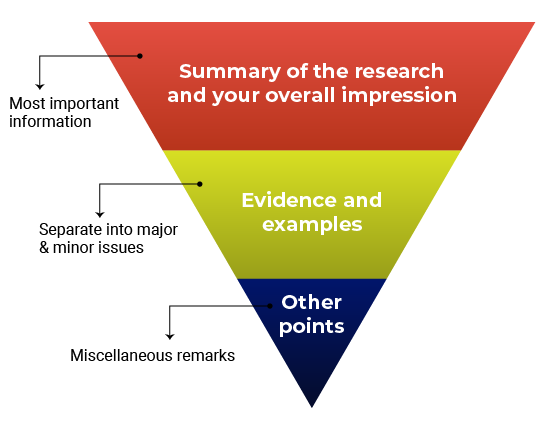

Think about structuring your review like an inverted pyramid. Put the most important information at the top, followed by details and examples in the center, and any additional points at the very bottom.

Here’s how your outline might look:

1. Summary of the research and your overall impression

In your own words, summarize what the manuscript claims to report. This shows the editor how you interpreted the manuscript and will highlight any major differences in perspective between you and the other reviewers. Give an overview of the manuscript’s strengths and weaknesses. Think about this as your “take-home” message for the editors. End this section with your recommended course of action.

2. Discussion of specific areas for improvement

It’s helpful to divide this section into two parts: one for major issues and one for minor issues. Within each section, you can talk about the biggest issues first or go systematically figure-by-figure or claim-by-claim. Number each item so that your points are easy to follow (this will also make it easier for the authors to respond to each point). Refer to specific lines, pages, sections, or figure and table numbers so the authors (and editors) know exactly what you’re talking about.

Major vs. minor issues

What’s the difference between a major and minor issue? Major issues should consist of the essential points the authors need to address before the manuscript can proceed. Make sure you focus on what is fundamental for the current study . In other words, it’s not helpful to recommend additional work that would be considered the “next step” in the study. Minor issues are still important but typically will not affect the overall conclusions of the manuscript. Here are some examples of what would might go in the “minor” category:

- Missing references (but depending on what is missing, this could also be a major issue)

- Technical clarifications (e.g., the authors should clarify how a reagent works)

- Data presentation (e.g., the authors should present p-values differently)

- Typos, spelling, grammar, and phrasing issues

3. Any other points

Confidential comments for the editors.

Some journals have a space for reviewers to enter confidential comments about the manuscript. Use this space to mention concerns about the submission that you’d want the editors to consider before sharing your feedback with the authors, such as concerns about ethical guidelines or language quality. Any serious issues should be raised directly and immediately with the journal as well.

This section is also where you will disclose any potentially competing interests, and mention whether you’re willing to look at a revised version of the manuscript.

Do not use this space to critique the manuscript, since comments entered here will not be passed along to the authors. If you’re not sure what should go in the confidential comments, read the reviewer instructions or check with the journal first before submitting your review. If you are reviewing for a journal that does not offer a space for confidential comments, consider writing to the editorial office directly with your concerns.

Get this outline in a template

Giving Feedback

Giving feedback is hard. Giving effective feedback can be even more challenging. Remember that your ultimate goal is to discuss what the authors would need to do in order to qualify for publication. The point is not to nitpick every piece of the manuscript. Your focus should be on providing constructive and critical feedback that the authors can use to improve their study.

If you’ve ever had your own work reviewed, you already know that it’s not always easy to receive feedback. Follow the golden rule: Write the type of review you’d want to receive if you were the author. Even if you decide not to identify yourself in the review, you should write comments that you would be comfortable signing your name to.

In your comments, use phrases like “ the authors’ discussion of X” instead of “ your discussion of X .” This will depersonalize the feedback and keep the focus on the manuscript instead of the authors.

General guidelines for effective feedback

- Justify your recommendation with concrete evidence and specific examples.

- Be specific so the authors know what they need to do to improve.

- Be thorough. This might be the only time you read the manuscript.

- Be professional and respectful. The authors will be reading these comments too.

- Remember to say what you liked about the manuscript!

Don’t

- Recommend additional experiments or unnecessary elements that are out of scope for the study or for the journal criteria.

- Tell the authors exactly how to revise their manuscript—you don’t need to do their work for them.

- Use the review to promote your own research or hypotheses.

- Focus on typos and grammar. If the manuscript needs significant editing for language and writing quality, just mention this in your comments.

- Submit your review without proofreading it and checking everything one more time.

Before and After: Sample Reviewer Comments

Keeping in mind the guidelines above, how do you put your thoughts into words? Here are some sample “before” and “after” reviewer comments

✗ Before

“The authors appear to have no idea what they are talking about. I don’t think they have read any of the literature on this topic.”

✓ After

“The study fails to address how the findings relate to previous research in this area. The authors should rewrite their Introduction and Discussion to reference the related literature, especially recently published work such as Darwin et al.”

“The writing is so bad, it is practically unreadable. I could barely bring myself to finish it.”

“While the study appears to be sound, the language is unclear, making it difficult to follow. I advise the authors work with a writing coach or copyeditor to improve the flow and readability of the text.”

“It’s obvious that this type of experiment should have been included. I have no idea why the authors didn’t use it. This is a big mistake.”

“The authors are off to a good start, however, this study requires additional experiments, particularly [type of experiment]. Alternatively, the authors should include more information that clarifies and justifies their choice of methods.”

Suggested Language for Tricky Situations

You might find yourself in a situation where you’re not sure how to explain the problem or provide feedback in a constructive and respectful way. Here is some suggested language for common issues you might experience.

What you think : The manuscript is fatally flawed. What you could say: “The study does not appear to be sound” or “the authors have missed something crucial”.

What you think : You don’t completely understand the manuscript. What you could say : “The authors should clarify the following sections to avoid confusion…”

What you think : The technical details don’t make sense. What you could say : “The technical details should be expanded and clarified to ensure that readers understand exactly what the researchers studied.”

What you think: The writing is terrible. What you could say : “The authors should revise the language to improve readability.”

What you think : The authors have over-interpreted the findings. What you could say : “The authors aim to demonstrate [XYZ], however, the data does not fully support this conclusion. Specifically…”

What does a good review look like?

Check out the peer review examples at F1000 Research to see how other reviewers write up their reports and give constructive feedback to authors.

Time to Submit the Review!

Be sure you turn in your report on time. Need an extension? Tell the journal so that they know what to expect. If you need a lot of extra time, the journal might need to contact other reviewers or notify the author about the delay.

Tip: Building a relationship with an editor

You’ll be more likely to be asked to review again if you provide high-quality feedback and if you turn in the review on time. Especially if it’s your first review for a journal, it’s important to show that you are reliable. Prove yourself once and you’ll get asked to review again!

- Getting started as a reviewer

- Responding to an invitation

- Reading a manuscript

- Writing a peer review

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

How to write a journal article review: Create a template

- What's in this Guide

- What is a journal article?

Create a template

- Choose your article to review

- Read your article carefully

- Do the writing

- Remember to edit

- Additional resources

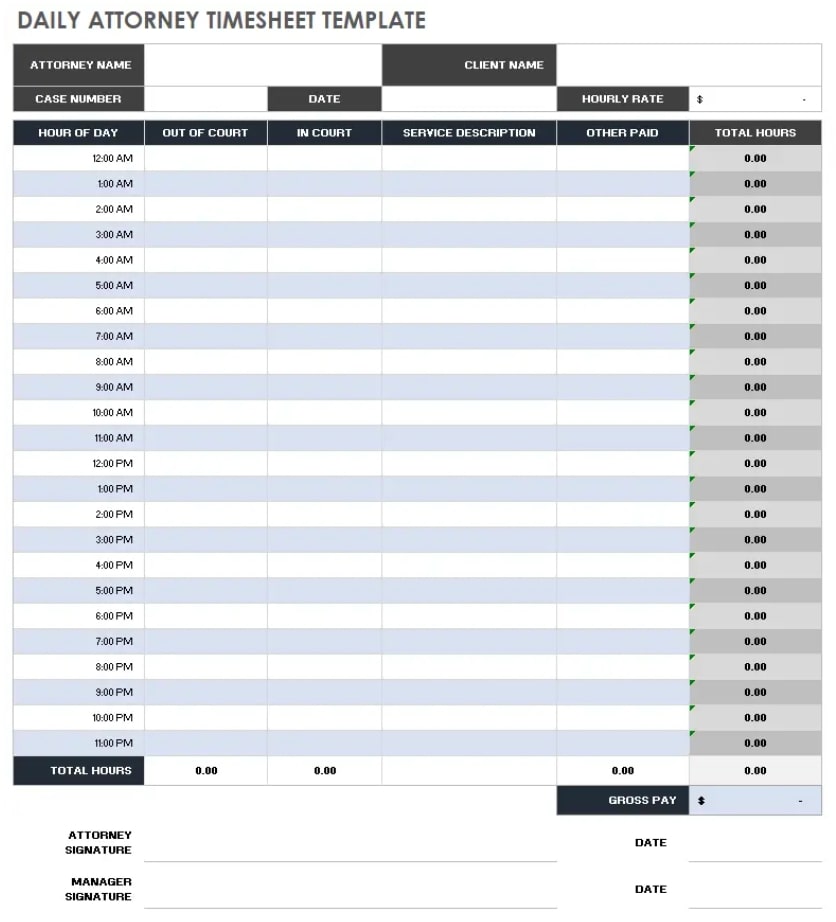

It might be helpful to create a template for your assessment.

A template will help you to keep you focussed on the requirements of your task.

Here, you will allocate a percentage of your word count per section, to keep your arguments on point and in accordance with your task’s instructions.

For example, if you are asked to write a journal article review of 800 words, you could break it down like this:

Pathways and Academic Learning Support

- << Previous: What is a journal article?

- Next: Choose your article to review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 27, 2023 4:28 PM

- URL: https://libguides.newcastle.edu.au/how-to-write-a-journal-article-review

Peer review templates, expert examples and free training courses

Joanna Wilkinson

Learning how to write a constructive peer review is an essential step in helping to safeguard the quality and integrity of published literature. Read on for resources that will get you on the right track, including peer review templates, example reports and the Web of Science™ Academy: our free, online course that teaches you the core competencies of peer review through practical experience ( try it today ).

How to write a peer review

Understanding the principles, forms and functions of peer review will enable you to write solid, actionable review reports. It will form the basis for a comprehensive and well-structured review, and help you comment on the quality, rigor and significance of the research paper. It will also help you identify potential breaches of normal ethical practice.

This may sound daunting but it doesn’t need to be. There are plenty of peer review templates, resources and experts out there to help you, including:

Peer review training courses and in-person workshops

- Peer review templates ( found in our Web of Science Academy )

- Expert examples of peer review reports

- Co-reviewing (sharing the task of peer reviewing with a senior researcher)

Other peer review resources, blogs, and guidelines

We’ll go through each one of these in turn below, but first: a quick word on why learning peer review is so important.

Why learn to peer review?

Peer reviewers and editors are gatekeepers of the research literature used to document and communicate human discovery. Reviewers, therefore, need a sound understanding of their role and obligations to ensure the integrity of this process. This also helps them maintain quality research, and to help protect the public from flawed and misleading research findings.

Learning to peer review is also an important step in improving your own professional development.

You’ll become a better writer and a more successful published author in learning to review. It gives you a critical vantage point and you’ll begin to understand what editors are looking for. It will also help you keep abreast of new research and best-practice methods in your field.

We strongly encourage you to learn the core concepts of peer review by joining a course or workshop. You can attend in-person workshops to learn from and network with experienced reviewers and editors. As an example, Sense about Science offers peer review workshops every year. To learn more about what might be in store at one of these, researcher Laura Chatland shares her experience at one of the workshops in London.

There are also plenty of free, online courses available, including courses in the Web of Science Academy such as ‘Reviewing in the Sciences’, ‘Reviewing in the Humanities’ and ‘An introduction to peer review’

The Web of Science Academy also supports co-reviewing with a mentor to teach peer review through practical experience. You learn by writing reviews of preprints, published papers, or even ‘real’ unpublished manuscripts with guidance from your mentor. You can work with one of our community mentors or your own PhD supervisor or postdoc advisor, or even a senior colleague in your department.

Go to the Web of Science Academy

Peer review templates

Peer review templates are helpful to use as you work your way through a manuscript. As part of our free Web of Science Academy courses, you’ll gain exclusive access to comprehensive guidelines and a peer review report. It offers points to consider for all aspects of the manuscript, including the abstract, methods and results sections. It also teaches you how to structure your review and will get you thinking about the overall strengths and impact of the paper at hand.

- Web of Science Academy template (requires joining one of the free courses)

- PLoS’s review template

- Wiley’s peer review guide (not a template as such, but a thorough guide with questions to consider in the first and second reading of the manuscript)

Beyond following a template, it’s worth asking your editor or checking the journal’s peer review management system. That way, you’ll learn whether you need to follow a formal or specific peer review structure for that particular journal. If no such formal approach exists, try asking the editor for examples of other reviews performed for the journal. This will give you a solid understanding of what they expect from you.

Peer review examples

Understand what a constructive peer review looks like by learning from the experts.

Here’s a sample of pre and post-publication peer reviews displayed on Web of Science publication records to help guide you through your first few reviews. Some of these are transparent peer reviews , which means the entire process is open and visible — from initial review and response through to revision and final publication decision. You may wish to scroll to the bottom of these pages so you can first read the initial reviews, and make your way up the page to read the editor and author’s responses.

- Pre-publication peer review: Patterns and mechanisms in instances of endosymbiont-induced parthenogenesis

- Pre-publication peer review: Can Ciprofloxacin be Used for Precision Treatment of Gonorrhea in Public STD Clinics? Assessment of Ciprofloxacin Susceptibility and an Opportunity for Point-of-Care Testing

- Transparent peer review: Towards a standard model of musical improvisation

- Transparent peer review: Complex mosaic of sexual dichromatism and monochromatism in Pacific robins results from both gains and losses of elaborate coloration

- Post-publication peer review: Brain state monitoring for the future prediction of migraine attacks

- Web of Science Academy peer review: Students’ Perception on Training in Writing Research Article for Publication

F1000 has also put together a nice list of expert reviewer comments pertaining to the various aspects of a review report.

Co-reviewing

Co-reviewing (sharing peer review assignments with senior researchers) is one of the best ways to learn peer review. It gives researchers a hands-on, practical understanding of the process.

In an article in The Scientist , the team at Future of Research argues that co-reviewing can be a valuable learning experience for peer review, as long as it’s done properly and with transparency. The reason there’s a need to call out how co-reviewing works is because it does have its downsides. The practice can leave early-career researchers unaware of the core concepts of peer review. This can make it hard to later join an editor’s reviewer pool if they haven’t received adequate recognition for their share of the review work. (If you are asked to write a peer review on behalf of a senior colleague or researcher, get recognition for your efforts by asking your senior colleague to verify the collaborative co-review on your Web of Science researcher profiles).

The Web of Science Academy course ‘Co-reviewing with a mentor’ is uniquely practical in this sense. You will gain experience in peer review by practicing on real papers and working with a mentor to get feedback on how their peer review can be improved. Students submit their peer review report as their course assignment and after internal evaluation receive a course certificate, an Academy graduate badge on their Web of Science researcher profile and is put in front of top editors in their field through the Reviewer Locator at Clarivate.

Here are some external peer review resources found around the web:

- Peer Review Resources from Sense about Science

- Peer Review: The Nuts and Bolts by Sense about Science

- How to review journal manuscripts by R. M. Rosenfeld for Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery

- Ethical guidelines for peer review from COPE

- An Instructional Guide for Peer Reviewers of Biomedical Manuscripts by Callaham, Schriger & Cooper for Annals of Emergency Medicine (requires Flash or Adobe)

- EQUATOR Network’s reporting guidelines for health researchers

And finally, we’ve written a number of blogs about handy peer review tips. Check out some of our top picks:

- How to Write a Peer Review: 12 things you need to know

- Want To Peer Review? Top 10 Tips To Get Noticed By Editors

- Review a manuscript like a pro: 6 tips from a Web of Science Academy supervisor

- How to write a structured reviewer report: 5 tips from an early-career researcher

Want to learn more? Become a master of peer review and connect with top journal editors. The Web of Science Academy – your free online hub of courses designed by expert reviewers, editors and Nobel Prize winners. Find out more today.

Related posts

Reimagining research impact: introducing web of science research intelligence.

Beyond discovery: AI and the future of the Web of Science

Clarivate welcomes the Barcelona Declaration on Open Research Information

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

I’m worried I’ve been contacted by a predatory publisher — how do I find out?

Career Feature 15 MAY 24

How I fled bombed Aleppo to continue my career in science

Career Feature 08 MAY 24

Illuminating ‘the ugly side of science’: fresh incentives for reporting negative results

Japan can embrace open science — but flexible approaches are key

Correspondence 07 MAY 24

US funders to tighten oversight of controversial ‘gain of function’ research

News 07 MAY 24

France’s research mega-campus faces leadership crisis

News 03 MAY 24

Mount Etna’s spectacular smoke rings and more — April’s best science images