6.1 Overview of Non-Experimental Research

Learning objectives.

- Define non-experimental research, distinguish it clearly from experimental research, and give several examples.

- Explain when a researcher might choose to conduct non-experimental research as opposed to experimental research.

What Is Non-Experimental Research?

Non-experimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable. Rather than manipulating an independent variable, researchers conducting non-experimental research simply measure variables as they naturally occur (in the lab or real world).

Most researchers in psychology consider the distinction between experimental and non-experimental research to be an extremely important one. This is because although experimental research can provide strong evidence that changes in an independent variable cause differences in a dependent variable, non-experimental research generally cannot. As we will see, however, this inability to make causal conclusions does not mean that non-experimental research is less important than experimental research.

When to Use Non-Experimental Research

As we saw in the last chapter , experimental research is appropriate when the researcher has a specific research question or hypothesis about a causal relationship between two variables—and it is possible, feasible, and ethical to manipulate the independent variable. It stands to reason, therefore, that non-experimental research is appropriate—even necessary—when these conditions are not met. There are many times in which non-experimental research is preferred, including when:

- the research question or hypothesis relates to a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables (e.g., How accurate are people’s first impressions?).

- the research question pertains to a non-causal statistical relationship between variables (e.g., is there a correlation between verbal intelligence and mathematical intelligence?).

- the research question is about a causal relationship, but the independent variable cannot be manipulated or participants cannot be randomly assigned to conditions or orders of conditions for practical or ethical reasons (e.g., does damage to a person’s hippocampus impair the formation of long-term memory traces?).

- the research question is broad and exploratory, or is about what it is like to have a particular experience (e.g., what is it like to be a working mother diagnosed with depression?).

Again, the choice between the experimental and non-experimental approaches is generally dictated by the nature of the research question. Recall the three goals of science are to describe, to predict, and to explain. If the goal is to explain and the research question pertains to causal relationships, then the experimental approach is typically preferred. If the goal is to describe or to predict, a non-experimental approach will suffice. But the two approaches can also be used to address the same research question in complementary ways. For example, Similarly, after his original study, Milgram conducted experiments to explore the factors that affect obedience. He manipulated several independent variables, such as the distance between the experimenter and the participant, the participant and the confederate, and the location of the study (Milgram, 1974) [1] .

Types of Non-Experimental Research

Non-experimental research falls into three broad categories: cross-sectional research, correlational research, and observational research.

First, cross-sectional research involves comparing two or more pre-existing groups of people. What makes this approach non-experimental is that there is no manipulation of an independent variable and no random assignment of participants to groups. Imagine, for example, that a researcher administers the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale to 50 American college students and 50 Japanese college students. Although this “feels” like a between-subjects experiment, it is a cross-sectional study because the researcher did not manipulate the students’ nationalities. As another example, if we wanted to compare the memory test performance of a group of cannabis users with a group of non-users, this would be considered a cross-sectional study because for ethical and practical reasons we would not be able to randomly assign participants to the cannabis user and non-user groups. Rather we would need to compare these pre-existing groups which could introduce a selection bias (the groups may differ in other ways that affect their responses on the dependent variable). For instance, cannabis users are more likely to use more alcohol and other drugs and these differences may account for differences in the dependent variable across groups, rather than cannabis use per se.

Cross-sectional designs are commonly used by developmental psychologists who study aging and by researchers interested in sex differences. Using this design, developmental psychologists compare groups of people of different ages (e.g., young adults spanning from 18-25 years of age versus older adults spanning 60-75 years of age) on various dependent variables (e.g., memory, depression, life satisfaction). Of course, the primary limitation of using this design to study the effects of aging is that differences between the groups other than age may account for differences in the dependent variable. For instance, differences between the groups may reflect the generation that people come from (a cohort effect) rather than a direct effect of age. For this reason, longitudinal studies in which one group of people is followed as they age offer a superior means of studying the effects of aging. Once again, cross-sectional designs are also commonly used to study sex differences. Since researchers cannot practically or ethically manipulate the sex of their participants they must rely on cross-sectional designs to compare groups of men and women on different outcomes (e.g., verbal ability, substance use, depression). Using these designs researchers have discovered that men are more likely than women to suffer from substance abuse problems while women are more likely than men to suffer from depression. But, using this design it is unclear what is causing these differences. So, using this design it is unclear whether these differences are due to environmental factors like socialization or biological factors like hormones?

When researchers use a participant characteristic to create groups (nationality, cannabis use, age, sex), the independent variable is usually referred to as an experimenter-selected independent variable (as opposed to the experimenter-manipulated independent variables used in experimental research). Figure 6.1 shows data from a hypothetical study on the relationship between whether people make a daily list of things to do (a “to-do list”) and stress. Notice that it is unclear whether this is an experiment or a cross-sectional study because it is unclear whether the independent variable was manipulated by the researcher or simply selected by the researcher. If the researcher randomly assigned some participants to make daily to-do lists and others not to, then the independent variable was experimenter-manipulated and it is a true experiment. If the researcher simply asked participants whether they made daily to-do lists or not, then the independent variable it is experimenter-selected and the study is cross-sectional. The distinction is important because if the study was an experiment, then it could be concluded that making the daily to-do lists reduced participants’ stress. But if it was a cross-sectional study, it could only be concluded that these variables are statistically related. Perhaps being stressed has a negative effect on people’s ability to plan ahead. Or perhaps people who are more conscientious are more likely to make to-do lists and less likely to be stressed. The crucial point is that what defines a study as experimental or cross-sectional l is not the variables being studied, nor whether the variables are quantitative or categorical, nor the type of graph or statistics used to analyze the data. It is how the study is conducted.

Figure 6.1 Results of a Hypothetical Study on Whether People Who Make Daily To-Do Lists Experience Less Stress Than People Who Do Not Make Such Lists

Second, the most common type of non-experimental research conducted in Psychology is correlational research. Correlational research is considered non-experimental because it focuses on the statistical relationship between two variables but does not include the manipulation of an independent variable. More specifically, in correlational research , the researcher measures two continuous variables with little or no attempt to control extraneous variables and then assesses the relationship between them. As an example, a researcher interested in the relationship between self-esteem and school achievement could collect data on students’ self-esteem and their GPAs to see if the two variables are statistically related. Correlational research is very similar to cross-sectional research, and sometimes these terms are used interchangeably. The distinction that will be made in this book is that, rather than comparing two or more pre-existing groups of people as is done with cross-sectional research, correlational research involves correlating two continuous variables (groups are not formed and compared).

Third, observational research is non-experimental because it focuses on making observations of behavior in a natural or laboratory setting without manipulating anything. Milgram’s original obedience study was non-experimental in this way. He was primarily interested in the extent to which participants obeyed the researcher when he told them to shock the confederate and he observed all participants performing the same task under the same conditions. The study by Loftus and Pickrell described at the beginning of this chapter is also a good example of observational research. The variable was whether participants “remembered” having experienced mildly traumatic childhood events (e.g., getting lost in a shopping mall) that they had not actually experienced but that the researchers asked them about repeatedly. In this particular study, nearly a third of the participants “remembered” at least one event. (As with Milgram’s original study, this study inspired several later experiments on the factors that affect false memories.

The types of research we have discussed so far are all quantitative, referring to the fact that the data consist of numbers that are analyzed using statistical techniques. But as you will learn in this chapter, many observational research studies are more qualitative in nature. In qualitative research , the data are usually nonnumerical and therefore cannot be analyzed using statistical techniques. Rosenhan’s observational study of the experience of people in a psychiatric ward was primarily qualitative. The data were the notes taken by the “pseudopatients”—the people pretending to have heard voices—along with their hospital records. Rosenhan’s analysis consists mainly of a written description of the experiences of the pseudopatients, supported by several concrete examples. To illustrate the hospital staff’s tendency to “depersonalize” their patients, he noted, “Upon being admitted, I and other pseudopatients took the initial physical examinations in a semi-public room, where staff members went about their own business as if we were not there” (Rosenhan, 1973, p. 256) [2] . Qualitative data has a separate set of analysis tools depending on the research question. For example, thematic analysis would focus on themes that emerge in the data or conversation analysis would focus on the way the words were said in an interview or focus group.

Internal Validity Revisited

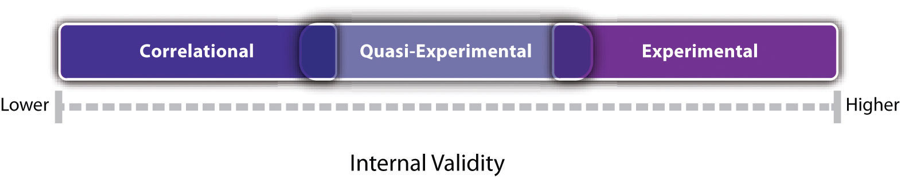

Recall that internal validity is the extent to which the design of a study supports the conclusion that changes in the independent variable caused any observed differences in the dependent variable. Figure 6.2 shows how experimental, quasi-experimental, and non-experimental (correlational) research vary in terms of internal validity. Experimental research tends to be highest in internal validity because the use of manipulation (of the independent variable) and control (of extraneous variables) help to rule out alternative explanations for the observed relationships. If the average score on the dependent variable in an experiment differs across conditions, it is quite likely that the independent variable is responsible for that difference. Non-experimental (correlational) research is lowest in internal validity because these designs fail to use manipulation or control. Quasi-experimental research (which will be described in more detail in a subsequent chapter) is in the middle because it contains some, but not all, of the features of a true experiment. For instance, it may fail to use random assignment to assign participants to groups or fail to use counterbalancing to control for potential order effects. Imagine, for example, that a researcher finds two similar schools, starts an anti-bullying program in one, and then finds fewer bullying incidents in that “treatment school” than in the “control school.” While a comparison is being made with a control condition, the lack of random assignment of children to schools could still mean that students in the treatment school differed from students in the control school in some other way that could explain the difference in bullying (e.g., there may be a selection effect).

Figure 6.2 Internal Validity of Correlation, Quasi-Experimental, and Experimental Studies. Experiments are generally high in internal validity, quasi-experiments lower, and correlation studies lower still.

Notice also in Figure 6.2 that there is some overlap in the internal validity of experiments, quasi-experiments, and correlational studies. For example, a poorly designed experiment that includes many confounding variables can be lower in internal validity than a well-designed quasi-experiment with no obvious confounding variables. Internal validity is also only one of several validities that one might consider, as noted in Chapter 5.

Key Takeaways

- Non-experimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable.

- There are two broad types of non-experimental research. Correlational research that focuses on statistical relationships between variables that are measured but not manipulated, and observational research in which participants are observed and their behavior is recorded without the researcher interfering or manipulating any variables.

- In general, experimental research is high in internal validity, correlational research is low in internal validity, and quasi-experimental research is in between.

- A researcher conducts detailed interviews with unmarried teenage fathers to learn about how they feel and what they think about their role as fathers and summarizes their feelings in a written narrative.

- A researcher measures the impulsivity of a large sample of drivers and looks at the statistical relationship between this variable and the number of traffic tickets the drivers have received.

- A researcher randomly assigns patients with low back pain either to a treatment involving hypnosis or to a treatment involving exercise. She then measures their level of low back pain after 3 months.

- A college instructor gives weekly quizzes to students in one section of his course but no weekly quizzes to students in another section to see whether this has an effect on their test performance.

- Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view . New York, NY: Harper & Row. ↵

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179 , 250–258. ↵

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

- Experimental Vs Non-Experimental Research: 15 Key Differences

There is a general misconception around research that once the research is non-experimental, then it is non-scientific, making it more important to understand what experimental and experimental research entails. Experimental research is the most common type of research, which a lot of people refer to as scientific research.

Non experimental research, on the other hand, is easily used to classify research that is not experimental. It clearly differs from experimental research, and as such has different use cases.

In this article, we will be explaining these differences in detail so as to ensure proper identification during the research process.

What is Experimental Research?

Experimental research is the type of research that uses a scientific approach towards manipulating one or more control variables of the research subject(s) and measuring the effect of this manipulation on the subject. It is known for the fact that it allows the manipulation of control variables.

This research method is widely used in various physical and social science fields, even though it may be quite difficult to execute. Within the information field, they are much more common in information systems research than in library and information management research.

Experimental research is usually undertaken when the goal of the research is to trace cause-and-effect relationships between defined variables. However, the type of experimental research chosen has a significant influence on the results of the experiment.

Therefore bringing us to the different types of experimental research. There are 3 main types of experimental research, namely; pre-experimental, quasi-experimental, and true experimental research.

Pre-experimental Research

Pre-experimental research is the simplest form of research, and is carried out by observing a group or groups of dependent variables after the treatment of an independent variable which is presumed to cause change on the group(s). It is further divided into three types.

- One-shot case study research

- One-group pretest-posttest research

- Static-group comparison

Quasi-experimental Research

The Quasi type of experimental research is similar to true experimental research, but uses carefully selected rather than randomized subjects. The following are examples of quasi-experimental research:

- Time series

- No equivalent control group design

- Counterbalanced design.

True Experimental Research

True experimental research is the most accurate type, and may simply be called experimental research. It manipulates a control group towards a group of randomly selected subjects and records the effect of this manipulation.

True experimental research can be further classified into the following groups:

- The posttest-only control group

- The pretest-posttest control group

- Solomon four-group

Pros of True Experimental Research

- Researchers can have control over variables.

- It can be combined with other research methods.

- The research process is usually well structured.

- It provides specific conclusions.

- The results of experimental research can be easily duplicated.

Cons of True Experimental Research

- It is highly prone to human error.

- Exerting control over extraneous variables may lead to the personal bias of the researcher.

- It is time-consuming.

- It is expensive.

- Manipulating control variables may have ethical implications.

- It produces artificial results.

What is Non-Experimental Research?

Non-experimental research is the type of research that does not involve the manipulation of control or independent variable. In non-experimental research, researchers measure variables as they naturally occur without any further manipulation.

This type of research is used when the researcher has no specific research question about a causal relationship between 2 different variables, and manipulation of the independent variable is impossible. They are also used when:

- subjects cannot be randomly assigned to conditions.

- the research subject is about a causal relationship but the independent variable cannot be manipulated.

- the research is broad and exploratory

- the research pertains to a non-causal relationship between variables.

- limited information can be accessed about the research subject.

There are 3 main types of non-experimental research , namely; cross-sectional research, correlation research, and observational research.

Cross-sectional Research

Cross-sectional research involves the comparison of two or more pre-existing groups of people under the same criteria. This approach is classified as non-experimental because the groups are not randomly selected and the independent variable is not manipulated.

For example, an academic institution may want to reward its first-class students with a scholarship for their academic excellence. Therefore, each faculty places students in the eligible and ineligible group according to their class of degree.

In this case, the student’s class of degree cannot be manipulated to qualify him or her for a scholarship because it is an unethical thing to do. Therefore, the placement is cross-sectional.

Correlational Research

Correlational type of research compares the statistical relationship between two variables .Correlational research is classified as non-experimental because it does not manipulate the independent variables.

For example, a researcher may wish to investigate the relationship between the class of family students come from and their grades in school. A questionnaire may be given to students to know the average income of their family, then compare it with CGPAs.

The researcher will discover whether these two factors are positively correlated, negatively corrected, or have zero correlation at the end of the research.

Observational Research

Observational research focuses on observing the behavior of a research subject in a natural or laboratory setting. It is classified as non-experimental because it does not involve the manipulation of independent variables.

A good example of observational research is an investigation of the crowd effect or psychology in a particular group of people. Imagine a situation where there are 2 ATMs at a place, and only one of the ATMs is filled with a queue, while the other is abandoned.

The crowd effect infers that the majority of newcomers will also abandon the other ATM.

You will notice that each of these non-experimental research is descriptive in nature. It then suffices to say that descriptive research is an example of non-experimental research.

Pros of Observational Research

- The research process is very close to a real-life situation.

- It does not allow for the manipulation of variables due to ethical reasons.

- Human characteristics are not subject to experimental manipulation.

Cons of Observational Research

- The groups may be dissimilar and nonhomogeneous because they are not randomly selected, affecting the authenticity and generalizability of the study results.

- The results obtained cannot be absolutely clear and error-free.

What Are The Differences Between Experimental and Non-Experimental Research?

- Definitions

Experimental research is the type of research that uses a scientific approach towards manipulating one or more control variables and measuring their defect on the dependent variables, while non-experimental research is the type of research that does not involve the manipulation of control variables.

The main distinction in these 2 types of research is their attitude towards the manipulation of control variables. Experimental allows for the manipulation of control variables while non-experimental research doesn’t.

Examples of experimental research are laboratory experiments that involve mixing different chemical elements together to see the effect of one element on the other while non-experimental research examples are investigations into the characteristics of different chemical elements.

Consider a researcher carrying out a laboratory test to determine the effect of adding Nitrogen gas to Hydrogen gas. It may be discovered that using the Haber process, one can create Nitrogen gas.

Non-experimental research may further be carried out on Ammonia, to determine its characteristics, behaviour, and nature.

There are 3 types of experimental research, namely; experimental research, quasi-experimental research, and true experimental research. Although also 3 in number, non-experimental research can be classified into cross-sectional research, correlational research, and observational research.

The different types of experimental research are further divided into different parts, while non-experimental research types are not further divided. Clearly, these divisions are not the same in experimental and non-experimental research.

- Characteristics

Experimental research is usually quantitative, controlled, and multivariable. Non-experimental research can be both quantitative and qualitative , has an uncontrolled variable, and also a cross-sectional research problem.

The characteristics of experimental research are the direct opposite of that of non-experimental research. The most distinct characteristic element is the ability to control or manipulate independent variables in experimental research and not in non-experimental research.

In experimental research, a level of control is usually exerted on extraneous variables, therefore tampering with the natural research setting. Experimental research settings are usually more natural with no tampering with the extraneous variables.

- Data Collection/Tools

The data used during experimental research is collected through observational study, simulations, and surveys while non-experimental data is collected through observations, surveys, and case studies. The main distinction between these data collection tools is case studies and simulations.

Even at that, similar tools are used differently. For example, an observational study may be used during a laboratory experiment that tests how the effect of a control variable manifests over a period of time in experimental research.

However, when used in non-experimental research, data is collected based on the researcher’s discretion and not through a clear scientific reaction. In this case, we see a difference in the level of objectivity.

The goal of experimental research is to measure the causes and effects of variables present in research, while non-experimental research provides very little to no information about causal agents.

Experimental research answers the question of why something is happening. This is quite different in non-experimental research, as they are more descriptive in nature with the end goal being to describe what .

Experimental research is mostly used to make scientific innovations and find major solutions to problems while non-experimental research is used to define subject characteristics, measure data trends, compare situations and validate existing conditions.

For example, if experimental research results in an innovative discovery or solution, non-experimental research will be conducted to validate this discovery. This research is done for a period of time in order to properly study the subject of research.

Experimental research process is usually well structured and as such produces results with very little to no errors, while non-experimental research helps to create real-life related experiments. There are a lot more advantages of experimental and non-experimental research , with the absence of each of these advantages in the other leaving it at a disadvantage.

For example, the lack of a random selection process in non-experimental research leads to the inability to arrive at a generalizable result. Similarly, the ability to manipulate control variables in experimental research may lead to the personal bias of the researcher.

- Disadvantage

Experimental research is highly prone to human error while the major disadvantage of non-experimental research is that the results obtained cannot be absolutely clear and error-free. In the long run, the error obtained due to human error may affect the results of the experimental research.

Some other disadvantages of experimental research include the following; extraneous variables cannot always be controlled, human responses can be difficult to measure, and participants may also cause bias.

In experimental research, researchers can control and manipulate control variables, while in non-experimental research, researchers cannot manipulate these variables. This cannot be done due to ethical reasons.

For example, when promoting employees due to how well they did in their annual performance review, it will be unethical to manipulate the results of the performance review (independent variable). That way, we can get impartial results of those who deserve a promotion and those who don’t.

Experimental researchers may also decide to eliminate extraneous variables so as to have enough control over the research process. Once again, this is something that cannot be done in non-experimental research because it relates more to real-life situations.

Experimental research is carried out in an unnatural setting because most of the factors that influence the setting are controlled while the non-experimental research setting remains natural and uncontrolled. One of the things usually tampered with during research is extraneous variables.

In a bid to get a perfect and well-structured research process and results, researchers sometimes eliminate extraneous variables. Although sometimes seen as insignificant, the elimination of these variables may affect the research results.

Consider the optimization problem whose aim is to minimize the cost of production of a car, with the constraints being the number of workers and the number of hours they spend working per day.

In this problem, extraneous variables like machine failure rates or accidents are eliminated. In the long run, these things may occur and may invalidate the result.

- Cause-Effect Relationship

The relationship between cause and effect is established in experimental research while it cannot be established in non-experimental research. Rather than establish a cause-effect relationship, non-experimental research focuses on providing descriptive results.

Although it acknowledges the causal variable and its effect on the dependent variables, it does not measure how or the extent to which these dependent variables change. It, however, observes these changes, compares the changes in 2 variables, and describes them.

Experimental research does not compare variables while non-experimental research does. It compares 2 variables and describes the relationship between them.

The relationship between these variables can be positively correlated, negatively correlated or not correlated at all. For example, consider a case whereby the subject of research is a drum, and the control or independent variable is the drumstick.

Experimental research will measure the effect of hitting the drumstick on the drum, where the result of this research will be sound. That is, when you hit a drumstick on a drum, it makes a sound.

Non-experimental research, on the other hand, will investigate the correlation between how hard the drum is hit and the loudness of the sound that comes out. That is, if the sound will be higher with a harder bang, lower with a harder bang, or will remain the same no matter how hard we hit the drum.

- Quantitativeness

Experimental research is a quantitative research method while non-experimental research can be both quantitative and qualitative depending on the time and the situation where it is been used. An example of a non-experimental quantitative research method is correlational research .

Researchers use it to correlate two or more variables using mathematical analysis methods. The original patterns, relationships, and trends between variables are observed, then the impact of one of these variables on the other is recorded along with how it changes the relationship between the two variables.

Observational research is an example of non-experimental research, which is classified as a qualitative research method.

- Cross-section

Experimental research is usually single-sectional while non-experimental research is cross-sectional. That is, when evaluating the research subjects in experimental research, each group is evaluated as an entity.

For example, let us consider a medical research process investigating the prevalence of breast cancer in a certain community. In this community, we will find people of different ages, ethnicities, and social backgrounds.

If a significant amount of women from a particular age are found to be more prone to have the disease, the researcher can conduct further studies to understand the reason behind it. A further study into this will be experimental and the subject won’t be a cross-sectional group.

A lot of researchers consider the distinction between experimental and non-experimental research to be an extremely important one. This is partly due to the fact that experimental research can accommodate the manipulation of independent variables, which is something non-experimental research can not.

Therefore, as a researcher who is interested in using any one of experimental and non-experimental research, it is important to understand the distinction between these two. This helps in deciding which method is better for carrying out particular research.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- examples of experimental research

- non experimental research

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

Experimental Research Designs: Types, Examples & Methods

Ultimate guide to experimental research. It’s definition, types, characteristics, uses, examples and methodolgy

Simpson’s Paradox & How to Avoid it in Experimental Research

In this article, we are going to look at Simpson’s Paradox from its historical point and later, we’ll consider its effect in...

Response vs Explanatory Variables: Definition & Examples

In this article, we’ll be comparing the two types of variables, what they both mean and see some of their real-life applications in research

What is Experimenter Bias? Definition, Types & Mitigation

In this article, we will look into the concept of experimental bias and how it can be identified in your research

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

Evidence Based Practice: Study Designs & Evidence Levels

- Databases to Search

- EBP Resources

- Study Designs & Evidence Levels

- How Do I...

Introduction

This section reviews some research definitions and provides commonly used evidence tables.

Levels of Evidence Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence Based Practice

Dang, D., & Dearholt, S. (2017). Johns Hopkins nursing evidence-based practice: model and guidelines. 3rd ed. Indianapolis, IN: Sigma Theta Tau International. www.hopkinsmedicine.org/evidence-based-practice/ijhn_2017_ebp.html

Identifying the Study Design

The type of study can generally be figured out by looking at three issues:

Q1. What was the aim of the study?

- To simply describe a population (PO questions) = descriptive

- To quantify the relationship between factors (PICO questions) = analytic.

Q2. If analytic, was the intervention randomly allocated?

- Yes? = RCT

- No? = Observational study

For an observational study, the main type will then depend on the timing of the measurement of outcome, so our third question is:

Q3. When were the outcomes determined?

- Some time after the exposure or intervention? = Cohort study ('prospective study')

- At the same time as the exposure or intervention? = Cross sectional study or survey

- Before the exposure was determined? = Case-control study ('retrospective study' based on recall of the exposure)

Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM)

Definitions of Study Types

Case report / Case series: A report on a series of patients with an outcome of interest. No control group is involved.

Case control study: A study which involves identifying patients who have the outcome of interest (cases) and patients without the same outcome (controls), and looking back to see if they had the exposure of interest.

Cohort study: Involves identification of two groups (cohorts) of patients, one which received the exposure of interest, and one which did not, and following these cohorts forward for the outcome of interest.

Randomized controlled clinical trial: Participants are randomly allocated into an experimental group or a control group and followed over time for the variables/outcomes of interest.

Systematic review: A summary of the medical literature that uses explicit methods to perform a comprehensive literature search and critical appraisal of individual studies and that uses appropriate statistical techniques to combine these valid studies.

Meta-analysis: A systematic review that uses quantitative methods to synthesize and summarize the results.

Meta-synthesis: A systematic approach to the analysis of data across qualitative studies. -- EJ Erwin, MJ Brotherson, JA Summers. Understanding Qualitative Meta-synthesis. Issues and Opportunities in Early Childhood Intervention Research, 33(3) 186-200 .

Cross sectional study: The observation of a defined population at a single point in time or time interval. Exposure and outcome are determined simultaneously.

Prospective, blind comparison to a gold standard: Studies that show the efficacy of a diagnostic test are also called prospective, blind comparison to a gold standard study. This is a controlled trial that looks at patients with varying degrees of an illness and administers both diagnostic tests — the test under investigation and the “gold standard” test — to all of the patients in the study group. The sensitivity and specificity of the new test are compared to that of the gold standard to determine potential usefulness.

Qualitative research: answers a wide variety of questions related to human responses to actual or potential health problems.The purpose of qualitative research is to describe, explore and explain the health-related phenomena being studied.

Retrospective cohort: follows the same direction of inquiry as a cohort study. Subjects begin with the presence or absence of an exposure or risk factor and are followed until the outcome of interest is observed. However, this study design uses information that has been collected in the past and kept in files or databases. Patients are identified for exposure or non-exposures and the data is followed forward to an effect or outcome of interest.

(Adapted from CEBM's Glossary and Duke Libraries' Intro to Evidence-Based Practice )

American Association of Critical Care Nursing-- Levels of Evidence

Level A Meta-analysis of multiple controlled studies or meta-synthesis of qualitative studies with results that consistently support a specific action, intervention or treatment

Level B Well designed controlled studies, both randomized and nonrandomized, with results that consistently support a specific action, intervention, or treatment

Level C Qualitative studies, descriptive or correlational studies, integrative reviews, systematic reviews, or randomized controlled trials with inconsistent results

Level D Peer-reviewed professional organizational standards, with clinical studies to support recommendations

Level E Theory-based evidence from expert opinion or multiple case reports

Level M Manufacturers’ recommendations only

Armola RR, Bourgault AM, Halm MA, Board RM, Bucher L, Harrington L, Heafey CA, Lee R, Shellner PK, Medina J. (2009) AACN levels of evidence: what's new ? J.Crit Care Nurse. Aug;29(4):70-3.

Flow Chart of Study Designs

Figure: Flow chart of different types of studies (Q1, 2, and 3 refer to the three questions below in "Identifying the Study Design" box.) Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM)

What is a "Confidence Interval (CI)"?

A confidence interval (CI) can be used to show within which interval the population's mean score will probably fall. Most researchers use a CI of 95%. By using a CI of 95%, researchers accept there is a 5% chance they have made the wrong decision in treatment. Therefore, if 0 falls within the agreed CI, it can be concluded that there is no significant difference between the two treatments. When 0 lies outside the CI, researchers will conclude that there is a statistically significant difference.

Halfens, R. G., & Meijers, J. M. (2013). Back to basics: an introduction to statistics. Journal Of Wound Care , 22 (5), 248-251.

What is a "p-value?"

Categorical (nominal) tests This category of tests can be used when the dependent, or outcome, variable is categorical (nominal), such as the difference between two wound treatments and the healing of the wound (healed versus nonhealed). One of the most used tests in this category is the chisquared test (χ2). The chisquared statistic is calculated by comparing the differences between the observed and the expected frequencies. The expected frequencies are the frequencies that would be found if there was no relationship between the two variables.

Based on the calculated χ2 statistic, a probability (p value) is given, which indicates the probability that the two means are not different from each other. Researchers are often satisfied if the probability is 5% or less, which means that the researchers would conclude that for p < 0.05, there is a significant difference. A p value ≥ 0.05 suggests that there is no significant difference between the means.

Halfens, R. G., & Meijers, J. M. (2013). Back to basics: an introduction to statistics. Journal Of Wound Care, 22(5), 248-251.

- << Previous: EBP Resources

- Next: How Do I... >>

- Last Updated: Oct 22, 2024 3:00 PM

- URL: https://mcw.libguides.com/evidencebasedpractice

MCW Libraries 8701 Watertown Plank Road Milwaukee, WI 53226 (414) 955-8302

Contact Us Locations & Hours Send Us Your Comments

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

22 Experimental vs. Non-Experimental Research

The next step a researcher must take is to decide which type of approach they will use to collect the data. As you will learn in your research methods course there are many different approaches to research that can be divided in many different ways. One of the most fundamental distinctions is between experimental and non-experimental research.

Experimental Research

Researchers who want to test hypotheses about causal relationships between variables (i.e., their goal is to explain) need to use an experimental method. This is because the experimental method is the only method that allows us to determine causal relationships. Using the experimental approach, researchers first manipulate one or more variables while attempting to control extraneous variables, and then they measure how the manipulated variables affect participants’ responses.

The terms independent variable and dependent variable are used in the context of experimental research. The independent variable is the variable the experimenter manipulates (it is the presumed cause) and the dependent variable is the variable the experimenter measures (it is the presumed effect).

Extraneous variables are any variable other than the dependent variable. Confounds are a specific type of extraneous variable that systematically varies along with the variables under investigation and therefore provides an alternative explanation for the results. When researchers design an experiment, they need to ensure that they control for confounds; they need to ensure that extraneous variables don’t become confounding variables because in order to make a causal conclusion they need to make sure alternative explanations for the results have been ruled out.

As an example, if we manipulate the lighting in the room and examine the effects of that manipulation on workers’ productivity, then the lighting conditions (bright lights vs. dim lights) would be considered the independent variable and the workers’ productivity would be considered the dependent variable. If the bright lights are noisy then that noise would be a confound since the noise would be present whenever the lights are bright and the noise would be absent when the lights are dim. If noise is varying systematically with light, then we wouldn’t know if a difference in worker productivity across the two lighting conditions is due to noise or light. So, confounds are bad, they disrupt our ability to make causal conclusions about the nature of the relationship between variables. However, if there is noise in the room both when the lights are on and when the lights are off then noise is merely an extraneous variable (it is a variable other than the independent or dependent variable) and we don’t worry much about extraneous variables. This is because unless a variable varies systematically with the manipulated independent variable it cannot be a competing explanation for the results.

Non-Experimental Research

Researchers who are simply interested in describing characteristics of phenomena, describing relationships between variables, and using those relationships to make predictions can use non-experimental research. Using the non-experimental approach, the researcher simply measures variables as they naturally occur, but they do not manipulate them. For instance, if I just measured the number of traffic fatalities in America last year that involved the use of a cell phone but I did not actually manipulate cell phone use then this would be categorized as non-experimental research. Alternatively, if I stood at a busy intersection and recorded drivers’ genders and whether or not they were using a cell phone when they passed through the intersection to see whether men or women are more likely to use a cell phone when driving, then this would be non-experimental research. It is important to point out that non-experimental does not mean non-scientific. Non-experimental research is scientific in nature. It can be used to fulfill two of the three goals of science (to describe and to predict). However, unlike with experimental research, we cannot make causal conclusions using this method; we cannot say that one variable causes another variable using this method.

Laboratory vs. Field Research

The next major distinction between research methods is between laboratory and field studies. A laboratory study is a study that is conducted in the laboratory environment. In contrast, a field study is a study that is conducted in the real-world, in a natural environment.

Laboratory experiments typically have high internal validity. Internal validity refers to the degree to which we can confidently infer a causal relationship between variables. When we conduct an experimental study in a laboratory environment, we have very high internal validity because we manipulate one variable while controlling all other outside extraneous variables. When we manipulate an independent variable and observe an effect on a dependent variable and we control for everything else so that the only difference between our experimental groups or conditions is the one manipulated variable then we can be quite confident that it is the independent variable that is causing the change in the dependent variable. In contrast, because field studies are conducted in the real-world, the experimenter typically has less control over the environment and potential extraneous variables, and this decreases internal validity, making it less appropriate to arrive at causal conclusions.

But there is typically a trade-off between internal and external validity. External validity simply refers to the degree to which we can generalize the findings to other circumstances or settings, like the real-world environment. When internal validity is high, external validity tends to be low; and when internal validity is low, external validity tends to be high. So, laboratory studies are typically low in external validity, while field studies are typically high in external validity. Since field studies are conducted in the real-world environment it is far more appropriate to generalize the findings to that real-world environment than when the research is conducted in the more artificial sterile laboratory.

Finally, there are field studies which are non-experimental in nature because nothing is manipulated. But there are also field experiments where an independent variable is manipulated in a natural setting and extraneous variables are controlled. Depending on their overall quality and the level of control of extraneous variables, such field experiments can have high external and high internal validity.

Critical Thinking Copyright © by Dinesh Ramoo, Thompson Rivers University Open Press is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 7: Nonexperimental Research

Overview of Nonexperimental Research

Learning Objectives

- Define nonexperimental research, distinguish it clearly from experimental research, and give several examples.

- Explain when a researcher might choose to conduct nonexperimental research as opposed to experimental research.

What Is Nonexperimental Research?

Nonexperimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable, random assignment of participants to conditions or orders of conditions, or both.

In a sense, it is unfair to define this large and diverse set of approaches collectively by what they are not . But doing so reflects the fact that most researchers in psychology consider the distinction between experimental and nonexperimental research to be an extremely important one. This distinction is because although experimental research can provide strong evidence that changes in an independent variable cause differences in a dependent variable, nonexperimental research generally cannot. As we will see, however, this inability does not mean that nonexperimental research is less important than experimental research or inferior to it in any general sense.

When to Use Nonexperimental Research

As we saw in Chapter 6 , experimental research is appropriate when the researcher has a specific research question or hypothesis about a causal relationship between two variables—and it is possible, feasible, and ethical to manipulate the independent variable and randomly assign participants to conditions or to orders of conditions. It stands to reason, therefore, that nonexperimental research is appropriate—even necessary—when these conditions are not met. There are many ways in which preferring nonexperimental research can be the case.

- The research question or hypothesis can be about a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables (e.g., How accurate are people’s first impressions?).

- The research question can be about a noncausal statistical relationship between variables (e.g., Is there a correlation between verbal intelligence and mathematical intelligence?).

- The research question can be about a causal relationship, but the independent variable cannot be manipulated or participants cannot be randomly assigned to conditions or orders of conditions (e.g., Does damage to a person’s hippocampus impair the formation of long-term memory traces?).

- The research question can be broad and exploratory, or it can be about what it is like to have a particular experience (e.g., What is it like to be a working mother diagnosed with depression?).

Again, the choice between the experimental and nonexperimental approaches is generally dictated by the nature of the research question. If it is about a causal relationship and involves an independent variable that can be manipulated, the experimental approach is typically preferred. Otherwise, the nonexperimental approach is preferred. But the two approaches can also be used to address the same research question in complementary ways. For example, nonexperimental studies establishing that there is a relationship between watching violent television and aggressive behaviour have been complemented by experimental studies confirming that the relationship is a causal one (Bushman & Huesmann, 2001) [1] . Similarly, after his original study, Milgram conducted experiments to explore the factors that affect obedience. He manipulated several independent variables, such as the distance between the experimenter and the participant, the participant and the confederate, and the location of the study (Milgram, 1974) [2] .

Types of Nonexperimental Research

Nonexperimental research falls into three broad categories: single-variable research, correlational and quasi-experimental research, and qualitative research. First, research can be nonexperimental because it focuses on a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables. Although there is no widely shared term for this kind of research, we will call it single-variable research . Milgram’s original obedience study was nonexperimental in this way. He was primarily interested in one variable—the extent to which participants obeyed the researcher when he told them to shock the confederate—and he observed all participants performing the same task under the same conditions. The study by Loftus and Pickrell described at the beginning of this chapter is also a good example of single-variable research. The variable was whether participants “remembered” having experienced mildly traumatic childhood events (e.g., getting lost in a shopping mall) that they had not actually experienced but that the research asked them about repeatedly. In this particular study, nearly a third of the participants “remembered” at least one event. (As with Milgram’s original study, this study inspired several later experiments on the factors that affect false memories.)

As these examples make clear, single-variable research can answer interesting and important questions. What it cannot do, however, is answer questions about statistical relationships between variables. This detail is a point that beginning researchers sometimes miss. Imagine, for example, a group of research methods students interested in the relationship between children’s being the victim of bullying and the children’s self-esteem. The first thing that is likely to occur to these researchers is to obtain a sample of middle-school students who have been bullied and then to measure their self-esteem. But this design would be a single-variable study with self-esteem as the only variable. Although it would tell the researchers something about the self-esteem of children who have been bullied, it would not tell them what they really want to know, which is how the self-esteem of children who have been bullied compares with the self-esteem of children who have not. Is it lower? Is it the same? Could it even be higher? To answer this question, their sample would also have to include middle-school students who have not been bullied thereby introducing another variable.

Research can also be nonexperimental because it focuses on a statistical relationship between two variables but does not include the manipulation of an independent variable, random assignment of participants to conditions or orders of conditions, or both. This kind of research takes two basic forms: correlational research and quasi-experimental research. In correlational research , the researcher measures the two variables of interest with little or no attempt to control extraneous variables and then assesses the relationship between them. A research methods student who finds out whether each of several middle-school students has been bullied and then measures each student’s self-esteem is conducting correlational research. In quasi-experimental research , the researcher manipulates an independent variable but does not randomly assign participants to conditions or orders of conditions. For example, a researcher might start an antibullying program (a kind of treatment) at one school and compare the incidence of bullying at that school with the incidence at a similar school that has no antibullying program.

The final way in which research can be nonexperimental is that it can be qualitative. The types of research we have discussed so far are all quantitative, referring to the fact that the data consist of numbers that are analyzed using statistical techniques. In qualitative research , the data are usually nonnumerical and therefore cannot be analyzed using statistical techniques. Rosenhan’s study of the experience of people in a psychiatric ward was primarily qualitative. The data were the notes taken by the “pseudopatients”—the people pretending to have heard voices—along with their hospital records. Rosenhan’s analysis consists mainly of a written description of the experiences of the pseudopatients, supported by several concrete examples. To illustrate the hospital staff’s tendency to “depersonalize” their patients, he noted, “Upon being admitted, I and other pseudopatients took the initial physical examinations in a semipublic room, where staff members went about their own business as if we were not there” (Rosenhan, 1973, p. 256). [3] Qualitative data has a separate set of analysis tools depending on the research question. For example, thematic analysis would focus on themes that emerge in the data or conversation analysis would focus on the way the words were said in an interview or focus group.

Internal Validity Revisited

Recall that internal validity is the extent to which the design of a study supports the conclusion that changes in the independent variable caused any observed differences in the dependent variable. Figure 7.1 shows how experimental, quasi-experimental, and correlational research vary in terms of internal validity. Experimental research tends to be highest because it addresses the directionality and third-variable problems through manipulation and the control of extraneous variables through random assignment. If the average score on the dependent variable in an experiment differs across conditions, it is quite likely that the independent variable is responsible for that difference. Correlational research is lowest because it fails to address either problem. If the average score on the dependent variable differs across levels of the independent variable, it could be that the independent variable is responsible, but there are other interpretations. In some situations, the direction of causality could be reversed. In others, there could be a third variable that is causing differences in both the independent and dependent variables. Quasi-experimental research is in the middle because the manipulation of the independent variable addresses some problems, but the lack of random assignment and experimental control fails to address others. Imagine, for example, that a researcher finds two similar schools, starts an antibullying program in one, and then finds fewer bullying incidents in that “treatment school” than in the “control school.” There is no directionality problem because clearly the number of bullying incidents did not determine which school got the program. However, the lack of random assignment of children to schools could still mean that students in the treatment school differed from students in the control school in some other way that could explain the difference in bullying.

Notice also in Figure 7.1 that there is some overlap in the internal validity of experiments, quasi-experiments, and correlational studies. For example, a poorly designed experiment that includes many confounding variables can be lower in internal validity than a well designed quasi-experiment with no obvious confounding variables. Internal validity is also only one of several validities that one might consider, as noted in Chapter 5.

Key Takeaways

- Nonexperimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable, control of extraneous variables through random assignment, or both.

- There are three broad types of nonexperimental research. Single-variable research focuses on a single variable rather than a relationship between variables. Correlational and quasi-experimental research focus on a statistical relationship but lack manipulation or random assignment. Qualitative research focuses on broader research questions, typically involves collecting large amounts of data from a small number of participants, and analyses the data nonstatistically.

- In general, experimental research is high in internal validity, correlational research is low in internal validity, and quasi-experimental research is in between.

Discussion: For each of the following studies, decide which type of research design it is and explain why.

- A researcher conducts detailed interviews with unmarried teenage fathers to learn about how they feel and what they think about their role as fathers and summarizes their feelings in a written narrative.

- A researcher measures the impulsivity of a large sample of drivers and looks at the statistical relationship between this variable and the number of traffic tickets the drivers have received.

- A researcher randomly assigns patients with low back pain either to a treatment involving hypnosis or to a treatment involving exercise. She then measures their level of low back pain after 3 months.

- A college instructor gives weekly quizzes to students in one section of his course but no weekly quizzes to students in another section to see whether this has an effect on their test performance.

- Bushman, B. J., & Huesmann, L. R. (2001). Effects of televised violence on aggression. In D. Singer & J. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of children and the media (pp. 223–254). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ↵

- Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view . New York, NY: Harper & Row. ↵

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179 , 250–258. ↵

Research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable, random assignment of participants to conditions or orders of conditions, or both.

Research that focuses on a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables.

The researcher measures the two variables of interest with little or no attempt to control extraneous variables and then assesses the relationship between them.

The researcher manipulates an independent variable but does not randomly assign participants to conditions or orders of conditions.

Research Methods in Psychology - 2nd Canadian Edition Copyright © 2015 by Paul C. Price, Rajiv Jhangiani, & I-Chant A. Chiang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Non-Experimental Research

28 Overview of Non-Experimental Research

Learning objectives.

- Define non-experimental research, distinguish it clearly from experimental research, and give several examples.

- Explain when a researcher might choose to conduct non-experimental research as opposed to experimental research.

What Is Non-Experimental Research?

Non-experimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable. Rather than manipulating an independent variable, researchers conducting non-experimental research simply measure variables as they naturally occur (in the lab or real world).

Most researchers in psychology consider the distinction between experimental and non-experimental research to be an extremely important one. This is because although experimental research can provide strong evidence that changes in an independent variable cause differences in a dependent variable, non-experimental research generally cannot. As we will see, however, this inability to make causal conclusions does not mean that non-experimental research is less important than experimental research. It is simply used in cases where experimental research is not able to be carried out.

When to Use Non-Experimental Research

As we saw in the last chapter , experimental research is appropriate when the researcher has a specific research question or hypothesis about a causal relationship between two variables—and it is possible, feasible, and ethical to manipulate the independent variable. It stands to reason, therefore, that non-experimental research is appropriate—even necessary—when these conditions are not met. There are many times in which non-experimental research is preferred, including when:

- the research question or hypothesis relates to a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables (e.g., how accurate are people’s first impressions?).

- the research question pertains to a non-causal statistical relationship between variables (e.g., is there a correlation between verbal intelligence and mathematical intelligence?).

- the research question is about a causal relationship, but the independent variable cannot be manipulated or participants cannot be randomly assigned to conditions or orders of conditions for practical or ethical reasons (e.g., does damage to a person’s hippocampus impair the formation of long-term memory traces?).

- the research question is broad and exploratory, or is about what it is like to have a particular experience (e.g., what is it like to be a working mother diagnosed with depression?).

Again, the choice between the experimental and non-experimental approaches is generally dictated by the nature of the research question. Recall the three goals of science are to describe, to predict, and to explain. If the goal is to explain and the research question pertains to causal relationships, then the experimental approach is typically preferred. If the goal is to describe or to predict, a non-experimental approach is appropriate. But the two approaches can also be used to address the same research question in complementary ways. For example, in Milgram’s original (non-experimental) obedience study, he was primarily interested in one variable—the extent to which participants obeyed the researcher when he told them to shock the confederate—and he observed all participants performing the same task under the same conditions. However, Milgram subsequently conducted experiments to explore the factors that affect obedience. He manipulated several independent variables, such as the distance between the experimenter and the participant, the participant and the confederate, and the location of the study (Milgram, 1974) [1] .

Types of Non-Experimental Research

Non-experimental research falls into two broad categories: correlational research and observational research.

The most common type of non-experimental research conducted in psychology is correlational research. Correlational research is considered non-experimental because it focuses on the statistical relationship between two variables but does not include the manipulation of an independent variable. More specifically, in correlational research , the researcher measures two variables with little or no attempt to control extraneous variables and then assesses the relationship between them. As an example, a researcher interested in the relationship between self-esteem and school achievement could collect data on students’ self-esteem and their GPAs to see if the two variables are statistically related.

Observational research is non-experimental because it focuses on making observations of behavior in a natural or laboratory setting without manipulating anything. Milgram’s original obedience study was non-experimental in this way. He was primarily interested in the extent to which participants obeyed the researcher when he told them to shock the confederate and he observed all participants performing the same task under the same conditions. The study by Loftus and Pickrell described at the beginning of this chapter is also a good example of observational research. The variable was whether participants “remembered” having experienced mildly traumatic childhood events (e.g., getting lost in a shopping mall) that they had not actually experienced but that the researchers asked them about repeatedly. In this particular study, nearly a third of the participants “remembered” at least one event. (As with Milgram’s original study, this study inspired several later experiments on the factors that affect false memories).

Cross-Sectional, Longitudinal, and Cross-Sequential Studies

When psychologists wish to study change over time (for example, when developmental psychologists wish to study aging) they usually take one of three non-experimental approaches: cross-sectional, longitudinal, or cross-sequential. Cross-sectional studies involve comparing two or more pre-existing groups of people (e.g., children at different stages of development). What makes this approach non-experimental is that there is no manipulation of an independent variable and no random assignment of participants to groups. Using this design, developmental psychologists compare groups of people of different ages (e.g., young adults spanning from 18-25 years of age versus older adults spanning 60-75 years of age) on various dependent variables (e.g., memory, depression, life satisfaction). Of course, the primary limitation of using this design to study the effects of aging is that differences between the groups other than age may account for differences in the dependent variable. For instance, differences between the groups may reflect the generation that people come from (a cohort effect ) rather than a direct effect of age. For this reason, longitudinal studies , in which one group of people is followed over time as they age, offer a superior means of studying the effects of aging. However, longitudinal studies are by definition more time consuming and so require a much greater investment on the part of the researcher and the participants. A third approach, known as cross-sequential studies , combines elements of both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Rather than measuring differences between people in different age groups or following the same people over a long period of time, researchers adopting this approach choose a smaller period of time during which they follow people in different age groups. For example, they might measure changes over a ten year period among participants who at the start of the study fall into the following age groups: 20 years old, 30 years old, 40 years old, 50 years old, and 60 years old. This design is advantageous because the researcher reaps the immediate benefits of being able to compare the age groups after the first assessment. Further, by following the different age groups over time they can subsequently determine whether the original differences they found across the age groups are due to true age effects or cohort effects.

The types of research we have discussed so far are all quantitative, referring to the fact that the data consist of numbers that are analyzed using statistical techniques. But as you will learn in this chapter, many observational research studies are more qualitative in nature. In qualitative research , the data are usually nonnumerical and therefore cannot be analyzed using statistical techniques. Rosenhan’s observational study of the experience of people in psychiatric wards was primarily qualitative. The data were the notes taken by the “pseudopatients”—the people pretending to have heard voices—along with their hospital records. Rosenhan’s analysis consists mainly of a written description of the experiences of the pseudopatients, supported by several concrete examples. To illustrate the hospital staff’s tendency to “depersonalize” their patients, he noted, “Upon being admitted, I and other pseudopatients took the initial physical examinations in a semi-public room, where staff members went about their own business as if we were not there” (Rosenhan, 1973, p. 256) [2] . Qualitative data has a separate set of analysis tools depending on the research question. For example, thematic analysis would focus on themes that emerge in the data or conversation analysis would focus on the way the words were said in an interview or focus group.

Internal Validity Revisited

Recall that internal validity is the extent to which the design of a study supports the conclusion that changes in the independent variable caused any observed differences in the dependent variable. Figure 6.1 shows how experimental, quasi-experimental, and non-experimental (correlational) research vary in terms of internal validity. Experimental research tends to be highest in internal validity because the use of manipulation (of the independent variable) and control (of extraneous variables) help to rule out alternative explanations for the observed relationships. If the average score on the dependent variable in an experiment differs across conditions, it is quite likely that the independent variable is responsible for that difference. Non-experimental (correlational) research is lowest in internal validity because these designs fail to use manipulation or control. Quasi-experimental research (which will be described in more detail in a subsequent chapter) falls in the middle because it contains some, but not all, of the features of a true experiment. For instance, it may fail to use random assignment to assign participants to groups or fail to use counterbalancing to control for potential order effects. Imagine, for example, that a researcher finds two similar schools, starts an anti-bullying program in one, and then finds fewer bullying incidents in that “treatment school” than in the “control school.” While a comparison is being made with a control condition, the inability to randomly assign children to schools could still mean that students in the treatment school differed from students in the control school in some other way that could explain the difference in bullying (e.g., there may be a selection effect).

Notice also in Figure 6.1 that there is some overlap in the internal validity of experiments, quasi-experiments, and correlational (non-experimental) studies. For example, a poorly designed experiment that includes many confounding variables can be lower in internal validity than a well-designed quasi-experiment with no obvious confounding variables. Internal validity is also only one of several validities that one might consider, as noted in Chapter 5.

- Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view . New York, NY: Harper & Row. ↵

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179 , 250–258. ↵

A research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable.

Research that is non-experimental because it focuses on the statistical relationship between two variables but does not include the manipulation of an independent variable.

Research that is non-experimental because it focuses on recording systemic observations of behavior in a natural or laboratory setting without manipulating anything.

Studies that involve comparing two or more pre-existing groups of people (e.g., children at different stages of development).

Differences between the groups may reflect the generation that people come from rather than a direct effect of age.

Studies in which one group of people are followed over time as they age.

Studies in which researchers follow people in different age groups in a smaller period of time.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2019 by Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler, & Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Understand the difference between experimental and non-experimental research designs and read open-access examples. ... What is case study methodology? It is unique given one characteristic: case studies draw from more than one data source. In this post find definitions and a collection of multidisciplinary examples.

Non-experimental research is a broad term that covers "any study in which the researcher doesn't have quite as much control as they do in an experiment". ... case studies can complement the more statistically-oriented approaches that you see in experimental and quasi-experimental designs. We won't talk much about case studies in these ...

Third, observational research is non-experimental because it focuses on making observations of behavior in a natural or laboratory setting without manipulating anything. Milgram's original obedience study was non-experimental in this way. He was primarily interested in the extent to which participants obeyed the researcher when he told them to shock the confederate and he observed all ...

There is a general misconception around research that once the research is non-experimental, then it is non-scientific, making it more important to understand what experimental and experimental research entails. ... The main distinction between these data collection tools is case studies and simulations. Even at that, similar tools are used ...

Non-experimental study Systematic review of a combination of RCTs, quasi-experimental and non-experimental studies, or non-experimental studies only, with or without meta-analysis ... Case control study: A study which involves identifying patients who have the outcome of interest (cases) and patients without the same outcome (controls), ...